Contents>> Vol. 5, No. 1

Contending Political Networks: A Study of the “Yellow Shirts” and “Red Shirts” in Thailand’s Politics

Naruemon Thabchumpon*

* นฤมล ทับจุมพล, Department of Government, Faculty of Political Science, Chulalongkorn University, 254 Henri Dunant Road, Pratumwan, Bangkok 10330, Thailand

e-mail: naruemon.t[at]chula.ac.th

DOI: doi.org/10.20495/seas.5.1_93

This essay investigates two bitter antagonists in the turbulent politics of contemporary Thailand: the People’s Alliance for Democracy (PAD), with its members labeled the “Yellow Shirts,” and the United Front for Democracy against Dictatorship (UDD), or the “Red Shirts.” Each of the two foes, typically regarded only as a social movement, actually has a vast network connecting supporters from many quarters. The Yellow Shirt network is associated with the monarchy, military, judiciary, and bureaucracy. The Red Shirt network, organizationally manifest in a series of electorally triumphant parties, is linked to exiled ex-Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, his “proxies,” and groups and individuals who opposed the military coup that ousted Thaksin in 2006. The significance of the two antagonistic networks can be gauged from their different influences on democratic processes over several years. Using concepts of political networks to examine the PAD and UDD within the socio-political context in which they arose, the essay focuses on several aspects of the networks: their political conception and perspectives, their organizational structures (for decision making and networking), and the strategies and activities of their members. The essay critically analyzes key and affiliated characters within the PAD and UDD, as well as the functional mechanisms of the networks, in order to evaluate the positions of the two networks in contemporary Thai politics.

Keywords: Thailand, contending networks, People’s Alliance for Democracy (PAD), United Front for Democracy against Dictatorship (UDD), Thaksin Shinawatra

In recent years, the explanation for Thailand’s democratization has been subject to intense debate. The binary opposition between the “urban elites and middle class people,” on the one hand, and the “rural majority” on the other has led the country’s democratic transformation into a situation of what I consider a polarization of two influential networks: the network of anti-Thaksin protests led by the People’s Alliance for Democracy (PAD) in 2006 and 2008, and the network of pro-Thaksin demonstrations led by the United Front for Democracy against Dictatorship (UDD) in 2009 and 2010. The past 10 years is viewed as a time of contentious politics, the politics of contested political networks.

This paper is an attempt to investigate two contesting political networks in Thailand’s politics, namely, the PAD and UDD. Using primary data and interviews with PAD and UDD members in 2009, 2010, and 2014, this paper explores the politics of contestation of the two political networks.1) While the first network is associated with the monarchy, the military, and the bureaucracy, the second network was led by former Prime Minister Thaksin and a series of his sequential political parties2) as well as individuals who disagreed with the 2006 military coup. The significance of these two networks can be seen from their politically influential roles in the Thai democratic process in the last five years.

To understand these two networks, the paper will provide a brief background on Thai politics and its contextual conditions with regard to political networks. Second, it will examine both networks in three categories: political conception and perspectives; organizational structure, which includes key decision makers and networking; strategies and activities of network’s members. Third, the paper will critically analyze specific characteristics of both networks, their key persons and affiliated members, as well as their functional mechanisms. Finally, the paper will offer a political interpretation of both networks with regard to their positioning in Thai politics.

I Thailand’s Politics from a Network Point of View

Following the re-election of then Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra3) in 2005, Thailand has been caught up in a political contestation between two power networks: the PAD and UDD. This section provides a brief background of Thai politics and its contextual conditions with respect to the country’s contemporary politics. It will discuss the dynamism of political and economic governances that have an impact on the politics of networking in Thailand.

The Thai political system operates within the framework of a constitutional monarchy, whereby the prime minister is the head of the government and a hereditary monarch is head of state. The judiciary is independent of the executive and legislative branches. The country has a political history of long periods of authoritarianism alternating with periods of “semi-democratic” government. Since the installation of the first representative government in 1932, the military has interrupted the constitutional order more than 18 times, with Thai citizens witnessing more than 20 changes of government and 18 written constitutions after the abolition of absolute monarchy. In May 2014 there was a coup to remove Yingluck Shinawatra, the first female prime minister and youngest sister of Thaksin Shinawatra, who was ousted in the September 2006 military coup by a group known as the Council of Democratic Reform.4)

After the September 19, 2006 military coup that removed Thaksin from office, the monarchy-centered network played a dominant role until December 2007, when the People Power Party—a successor of the Thai Ruk Thai party, which was dissolved due to a vote-buying scandal—won the first post-coup election. During most of 2008,5) a pro-Thaksin government held office under protracted protests by the PAD. It was judicially ousted in December of that year, when a backroom political deal made Democrat Party leader Abhisit Vejjajiva prime minister without the benefit of an election.6) Thaksin supporters regarded Abhisit’s premiership as illegitimate and repeatedly pressed him to dissolve parliament and call fresh elections.

According to D. McCargo (2006), there are two modes of legitimacy—electoral and technocratic—that any government that wants to survive in Thai politics has to contend with. The former concerns forming the government: political parties, in order to gain the highest number of seats in the election, targeted mainly rural areas, which were notorious for the practice of vote buying. The latter comes from a party’s technocratic expertise in the eyes of the urban middle classes. Both types of legitimacy are closely connected with the project of making the politics of representation work and making the country’s political system more accountable, transparent, and stable.

In the Thai case, however, it can be argued that many political crises have demonstrated the persistent characteristics of Thai politics: a strong military, weak political parties, personalized leadership, a lack of “democratic consciousness” on the part of civil society and the general public, and an important role for rumors and opinions put out by the press. Another unmentionable factor in Thailand’s politics is the political influence of the monarchy, created largely since the 1958 coup (Naruemon 2012, 8).

The interventionist role of the monarchy-centered network in the Thai political process and political institutions, especially in electoral politics, has been apparent from time to time and has been clearly seen in the last 10 years. The King is often seen as an important actor for political change and stability in Thailand’s politics. While McCargo considers the interventionist role of members of the Privy Council as a proxy network of the monarch, A. Bamford and C. Chanyapate (2006) argue that the action or inaction of the palace was largely seen as a political signal from the monarch to politicians. The problematic and contested nature of democracy in Thailand is abundantly illustrated by the military coup d’état of September 19, 2006, a further example that the rules of the Thai political game remain fluid and that elites still see themselves as having the right to override popular participation for their own ends.

In terms of the political context of both networks, the UDD was formed partly in response to the anti-Thaksin movement known as the People’s Alliance for Democracy (PAD). Royalist PAD members, donning their trademark yellow shirts, staged anti-Thaksin demonstrations in the early months of 2006, after which they accepted the 2007 election results and disbanded their network. The PAD renewed its protests in 2008, when the pro-Thaksin government attempted to bring back the prime minister. The 2008 protests involved occupying Government House in August and closing down Bangkok’s airports in late November and early December. The political conflicts and arguments between the PAD and UDD networks may be viewed as a form of tension between elitist and electoral models of democracy as well as representing two power networks: professionals/technocrats and majoritarian networks.

On the one side, for example, the UDD, representing an electoral majoritarian power network, supported liberal reform advocates who considered democracy as a legalistic and formal process of political institutions (such as political parties, elections, and legislative capacity). On the other side, the PAD, representing an elitist model of professionals and a technocratic power network, favored those who argued that elections were meaningless unless people were aware of the real choices and the meaning of those choices, as well as having full information on policies that would affect them. Both networks argued for the principles of democracy, whether it was seen as government by elected representatives acting in the name of the people or government by the people themselves.

The differences between both networks in relation to the interpretation of Thai democratic politics have created a polarization among civil society groups. This is evident in various arguments, political discourses, and clarifications over the meaning of democratic legitimacy. For example, the established middle classes and urban-based civic groups, which are PAD’s supporters, argue that the priority of the country is to repair the damage done by political corruption and money politics. In comparison, networks of UDD supporters feel that their voices were not considered in formulating state policy up until the 2001 election and decentralization scheme. Even if they acknowledged corruption issues surrounding Thaksin’s premiership, the UDD considered Thaksin’s time in office as a unique period during which the Bangkok government was genuinely responsive to rural people’s needs and concerns. The UDD’s preferential treatment can be seen as a political project in the government’s economic plan and fiscal policy of boosting consumption and hence the domestic economy. Due to different interpretations and preferences between the two networks, UDD supporters have been anti-PAD since the 2006 coup, when they accused the PAD of supporting the coup. From then on, clashes between supporters of the two groups have taken place from time to time and there has not yet been a reconciliation.

II Understanding the PAD and Its Political Networks

The PAD is a well-organized network, with its own powerful media arrangement—the Manager-ASTV—emerging in Thai politics. Semi-structured interviews with PAD network members involved in the 2008 six-month protests, including members from the Friends of People Group, Federation of State Enterprise Worker Unions (SEWU), Indebted Farmers Network, Northern Farmer Federation, Thai Patriot Network, Council of People’s Networks in Thailand, Health Professional Network, Business Society for Democracy, Santi-Asoke Group, and Alliance for Democratic Artists and ASTV media team,7) yielded the following findings.

According to interviews (2009), this network uses a vertical and unified organizational style rather than a horizontal style, with a certain degree of autonomy on political activities. Under the discourse of destroying the Thaksin regime and protecting national institutions, the PAD uses provocative strategies with strong elements of ultra-royalist nationalism. The controversial role of the PAD has generated unsettling discussions on urban politics and the negative role of the middle classes in damaging Thai democracy. With the group being an elitist movement that has not benefited from electoral mass politics, its core members conceive and practice extra-parliamentary politics that go beyond interest group politics. The group’s campaigns range from the rehabilitation of indebted farmers to the ousting of the elected prime minister, before going on to the proposal of creating a moral economy with a soft authoritarian style.8)

The PAD is a political network comprising elite-urban civic groups in alliance with the military, bureaucracy, middle-class activists, communitarian NGO workers and small-scale farmers, conservative academics, and business entrepreneurs as well as some members of the royal family. The PAD’s political activities can be categorized as diffuse issue-based politics. In the PAD context,9) resistance takes place within a common framework of action against a common enemy, meaning an anti-Thaksin movement, rather than in accordance with one particular class or geographical identification.

In terms of the collective action of the networks under the PAD, this network redefined and overruled the principles of democracy with its discourse of good governance, anti-corruption, and clean politics to enable the struggles of oppositional groups and street politics to be reframed as a civic activity for direct participation that might take the place of—and be incompatible with—representative democracy.

II-1 Composition and Key Characteristics of the PAD

According to interviews with two PAD members (2009), the PAD consists of a political network with a wide variety of professional organizations (such as teachers, medical doctors, lawyers, and government officers), state enterprise unions, fundamental religious organizations (meaning the Santi-Asoke Buddhism and its Dharma Army group), communitarian NGOs, networks of small-scale farmer organizations, and urban middle-class individuals. Key active members of the PAD are from the Asoke Group, Manager-ASTV Media Group, Northern Farmer Federation, Alliance of Democratic Artists, Council Network of People’s Organization, Young PAD, and Campaign for Popular Democracy. Members of these organizational networks are key players of the PAD. During the demonstrations, for example, Second Lieutenant Samdin Lerbutr, the president of the Santi-Asoke Commune, was in charge of food and security for the PAD; and Yuthayong Limlert-watee, from the Manager-ASTV, was the stage manager of the PAD program. Although the PAD is neither a membership-based organization nor an interest group that is concerned only with the benefit of its members, several network members join the PAD because their organizational interests are affected by government policies. For example, the issue of privatization of state enterprise was the rallying issue for state enterprise unions to support the PAD, while primary school teachers supported it because they were dissatisfied over the downsizing and transferring of power and authority over public schools from the central government to local school sub-districts with limited staff under the Thaksin government in 2005. Key players in the PAD include Major General Chamlong Srimuang from the Asoke group and Sonti Limthongkul from the Manager-ASTV Media. It can be argued that both of them have influenced the PAD’s arguments on nationalism, communitarianism, and clean politics.

In terms of individual members of the PAD, the key players are those from the royal family and retired or existing military personnel. Members of the royal family or blue blood jet set who support the PAD are grouped under the network called the Truth and Transparency Society (TTS). The TTS’s members include Anong Nilubon, MR Rampi-arpa Kasemsri, Tuangtip Veera-vaitaya, Prapai Prasartthong-osod, Benjawan Krajangnetra, and royal family members of Diskul na Ayuthaya.10) These people did not only join the 183-day PAD demonstrations but also financially supported the PAD campaigns. Although the existing military personnel are difficult to identify, the retired military persons can be seen from members of the U-na-lome Society, whose chairperson is General Pratompong Kaesornsuk. Other key players in the PAD are Seangtham Chunchadatan, a youth leader, and Tul Sithisomwong, a medical doctor at the King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital. Seangtham is a member of Young PAD who helped organize the PAD Demonstration School (Sathid Makawan) during the PAD’s encampment at Makawan Bridge.11) He can be seen as a node of the network in the sense that he created a new network called Young PAD, with a Web site and cyber-technology for the release of information, network communication, and mobilization. Tul Sithisomwong is seen as another node in the Network of Citizen Volunteers Protecting the Land (or the Multicolor Shirt movement) since he has organized and led various activities, including the Facebook Movement and a protest rally against Thaksin’s corruption scandals.

The 2010 Facebook Movement, which started through Internet communications (such as sharing pictures, clips, and other documents through online networks) moved on to organize a counter demonstration against the 2010 UDD protest demanding a dissolving of parliament. In this particular case, Tul Sithisomwong, a medical doctor who joined the PAD demonstration before the 2006 coup, can be seen as another node in the cyber network by posting information, before transforming into the hub of another network by being a leader of the Multicolor Shirt network against the UDD demonstration and dissolution of parliament in 2010. Although most members of the Facebook network are not PAD supporters, they are mobilized by cyber information and communication that encourages them to join the Multicolor Shirt network.

II-2 Political Conception of the PAD

In the case of the PAD, many intellectual advisers of the network were influenced by ultranationalism and conservatism. Resulting from their experience with vertical lines of command, these leaders turned to the idea of aristocratic democracy and vertical lines of networking at the expense of the internal democracy of the network.

Under “discursive struggles,” the PAD’s arguments are divided into three debates: nationalism against neoliberalism, communitarianism against populism, and clean politics against money politics. Moralist political discourses were used as the network’s motto to support its positioning in Thai politics. As there is no equality of power among civil society members under the umbrella of the network, those who have access to power perceive political strategies and politics in a different way from those who do not have bargaining power. For instance, many voluntary civil society groups were subsumed under the PAD category; they included conservative factions, which had royal family members and retired government officers, as well as more progressive factions, such as the Northern Peasants Federation and the Federation of State Enterprise Worker Unions (SEWU). Their overall struggle was conducted by violent and nonviolent resistance groups. Given the unequal power structure in the case of the PAD, some elitist civil society organizations can be accessories of the state and promote a state-led view of civil society as well as promoting conservative institutional networks, such as the monarchy and military. While the “network monarchy” suggested by McCargo (2005) looks at active interventions in the political process by the palace and its proxies, notably former Prime Minister Prem Tinsulanond—who acted on behalf of the palace to restore political equilibrium in Thailand’s power relations with certain elements of liberalism—the PAD and its Yellow Shirt network, in contrast, is seen as a network of middle- to upper-class residents who stand for honest politics with a moralistic political discourse and some elements of patriarchy and nationalism. Members of the PAD network will always uphold the constitutional monarchy and oppose those they view as wanting to change the monarchy’s status.

In terms of the middle class, moreover, it has been argued that most political observers took it for granted since the May 1992 events were viewed as a democratic uprising of the middle classes. Due to the inconsistent role of the middle class in 1976, 1991, and 2006, it can be contended that this class might have played a role in the democratic uprising; but it was not in the forefront when the fighting erupted. Most of those killed and injured during the uprising belonged to the lower classes, and, as Nithi Eawsriwong (2002) comments, the middle class does not necessary believe in either democracy or equality. As K. Hewison (1997, 214) argues, “[T]he inconsistent role of the Thai middle class during 1991 and 1992 should be considered as an unpredictable political factor which was not necessarily animated by liberal democratic values.”

The PAD comprises groups representing different sectors and classes, whose alliance is issue-based. Due to its lack of access to electoral and institutional politics, this group prefers to adopt a group-based or occupation-based model of representation, rather than a geographical model of representative politics and periodic elections. It also uses the politics of direct action without engaging in formal processes and institutional channels for political participation.

Reflecting the power relations among network groupings under the PAD, it can be argued that the strongest voices among organizations claiming to be representative of the network have been those of educated middle-class urban residents and white-collar career workers, whilst the poor have become a minority segment or a prop of the political scenery under the PAD discourse. The combined presence but unequal roles of these different classes and social groups demonstrate the wide range of views that appeared in the active citizen participation in Thai politics.

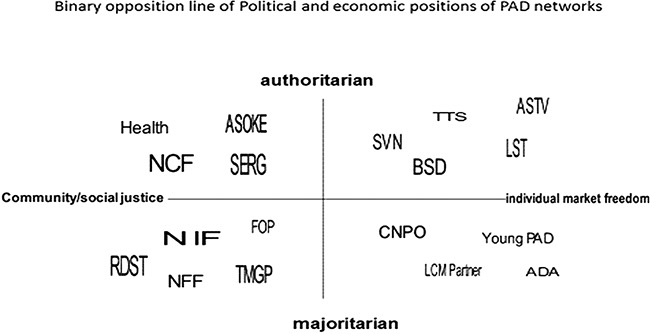

To elaborate on the contested perceptions of various networks under the PAD, a mapping of a wide variety of political and economic positions can be seen through the matrix in Fig. 1. The matrix shows the wide range of political opinions of PAD members, from middle-class activists, professional groups, academic societies, and the media to the community and some sectors of the indebted farmer network. The composition of the PAD network is drawn from different sectors and is cross-class in affiliation and issue-based in orientation rather than being an ideological standpoint or territorial grouping. The common theme that links all members of the PAD is clean politics with a moral order. According to an interview with a PAD member, “Democracy without moral principles cannot fulfill Thailand’s political society, and the monarchy is required for peace, prosperity, and stability of the country.”

Fig. 1 Mapping of the Position of the PAD in Thai Civil Society

Note: ADA: Alliance for Democratic Artists; BSD: Business Society for Democracy; CNPO: Council Network of People Organization; FOP: Friends of People; Health: Health Professional Network; LCM Partner: Local Community’s Member; LST: Law Society of Thailand; NCF: Network of Community’s Farmers; NFF: Northern Farmer Federation; NIF: Indebted Farmers Network (Sometime they call themselves Network of Indebted Farmers); RDST: Rural Development in the Southern Network of Thailand; SERG: State Enterprise Railway Group (a core member of the Federation of State Enterprise Worker Unions); SVN: Social Venture Network; TMGP: Thai Media Group for People; TTS: Truth and Transparency Society.

II-3 Organization and Functional Structure of the PAD

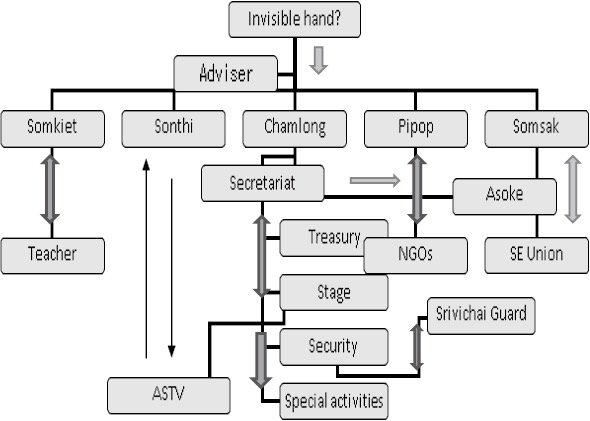

At the organizational level, the PAD is composed of autonomous networks of mostly elite urban, upper middle class, and other professional groups as well as individual members. As shown in Fig. 1, PAD network members share the idea of expanding the existing democratic system to solve the problems of money politics but may have different views on the strategies and activities of each network and their view of political practices. The PAD’s leadership structure consists of five leaders, with another seven as second-in-command who represent the network if the five leaders are arrested. The PAD’s adoption of a vertical organizational structure was intended to increase unity and efficiency, which held the risk of building the concentration of power in the hands of leaders (as happened in the case of the 183-day demonstration). The consequent problem, however, was to achieve a balance between democratic legitimacy and organizational effectiveness. The vertical structure of the PAD has been criticized as being undemocratic, detracting from the internal democracy of the organization. The PAD network’s vertical structure can be seen in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2 Organization Chart of the PAD

Note: The PAD’s organization chart clearly shows it as an organization rather than a network, due to its militia character during the protests. However, each section has its own diagram network similar to the UDD’s, but the central command is still under five leaders who supervise all agendas (personal interview, November 18, 2009).

II-4 Political Strategies and Activities of the PAD

In the case of the PAD’s strategy, its agenda ranges from community work and self-help organizations to the politics of good governance and the building of a moralistic political society. The PAD highlights the notion of transparency and accountability of politicians and the participation of educated and well-informed citizens, in the belief that this will help Thailand survive its political crises. The “good governance” terminology, however, should be seen as a product of the Thai elites’ desire to appear to be conforming to international standards while neglecting the problems of the poor.

At the strategy level, the PAD adopts a dual strategy: confrontation and negotiation in all aspects. This network uses the ideology of nationalism and ultra-royalist sentiment in order to attract more members from among the elites. Its campaign strategy stands on an issue-based platform emphasizing anti-Thaksin anti-money politics in order to get support from the middle class and the media. The PAD argues that its version of democracy is linked with the politics of moral polity and a neo-authoritarian developmental state.12) Members of the PAD were grouped together as jointly fighting for “new politics.” This anti-Thaksin strategy brought together those who were frustrated over existing money politics. Members thus shared the same perspective and were committed to the struggle because of a mutual understanding that derived from their own direct experiences. This sense of solidarity enabled them to continue their struggle in the longer term. According to several interviews with PAD supporters who participated in the 2008 and 2009 demonstrations, perceptions of the power relationship between themselves and other people changed markedly when they became organized. By adopting mass mobilization as its prime source of social sanction, the PAD empowered its members and enabled them to make demands of their local officials, as they had done in the past.

At the level of its activities more generally, according to Uchane Cheangsan (2013, 10–14), the PAD uses the politics of protest and civil disobedience—with its network members advancing their agendas through collective action in order to draw attention to the deficiencies of the state system—to pressure the government and become involved in the public policy process. It engages in provocative activities and disruptive actions to draw the attention of the media and hence return to the negotiating table with increased bargaining power.

Regarding the politics of NGOs associated with the PAD, there has been intense debate about the former’s political role in the democratization process and their democratic values (Callahan 1998, 84–129). Thai NGOs have tried to increase people’s participation in the policy process by linking their advocacy with community groups and people’s organizations. Ironically, the Campaign for Popular Democracy, established by a coalition of NGOs, student activists, academics, and other professional associations during the political crisis of 1991–92, became a core member of the PAD; and its network organizations played a contradictory role against democratic values in many ways.

The PAD’s perceptions of democracy can be identified through its argument on “new politics” that aims at a trade-off between procedural democracy and institutional stability under the limitations of representative politics. The quality of the country’s democracy, moreover, remains dependent upon the government and its professional advisers, and the reform itself is deeply compromised by institutional deficits. Institutional arrangements and representative mechanisms are unable to take hold. Thus, the guaranteeing of popular rights and participation has turned out to be beset by complicated procedures that reduce the democratic space and direct participation by the people.

There is an incompatibility between the way the PAD practices participatory politics and the way the country’s government practices democracy. The perception of the urban middle class toward the problems of the poor is also undemocratic. People from elite groups, such as the media, academic, and urban middle classes, have a relatively powerful position from which they can challenge government policy. The poor, however, do not have the power to bargain with the government. Hence, in order for their voices to be heard, the latter have to cooperate with—and even rely on—the middle classes.

III Understanding the UDD and Its Political Networks

The United Front for Democracy against Dictatorship (UDD), or the Red Shirts, was set up as an anti-PAD organization after the 2006 coup, when it accused the PAD of supporting the coup. In the beginning the UDD was seen as a small-scale organization with strength in only a handful of provinces, without the capacity to initiate any large and sustained demonstrations. The UDD network faced a harsh military crackdown before re-emerging in the wake of a controversial February 2010 court decision confiscating the bulk of Thaksin’s assets.

On the basis of primary data and interviews with UDD members in 2010, this paper views the UDD network as a set of loose and autonomous rural networks of small-scale organizations with a new style of media channel, namely, community radio and satellite/Internet-based television.13) In terms of organizational structure, its horizontal, loosely organized, and provincial autonomous organizational style of networking has generated discussions on the issues of rural politics and the political role of rural and peripheral people’s networks in Thai democracy. To a large extent, the UDD can be seen as a pro-Thaksin movement. Although some segments in the UDD, such as the network of social and radical activists (namely, the Red Siam group), have an opinion different from the pro-Thaksin movement, they are in the minority.

One way to explain the UDD network is to adopt the concept of oppositional consciousness (Mansbridge 2001, 238) to understand how “the network is created, organised and functioned under a diversity of groups and opinions on organisational strategies and modes of action.” Another way is to understand the dynamism of mass politics in the context of Thailand’s democratization process, especially after the 1997 constitution.

On the first account, as J. Mansbridge (ibid., 243) comments, the motivation for collective action by a group requires more than just recognizing injustice, understanding a common interest, or identifying the limitations of the existing system; it also involves a commitment to act in order to defend or help support such ideas. In other words, it implies a move from recognizing the need for collective action to a willingness to undertake such action.

In the case of the UDD, this network redefined the conception of social justice to show how electoral participation was intertwined with political conditions and public policy. It argued that the economic populist scheme provided by politicians benefited the rural poor, especially those belonging to the non-farming sector. In other words, the economic populist platform could be seen as a legitimate way to gain votes through governmental projects using public funds, which is the power of the poor to have a say in public policy decisions. The UDD network was first categorized as a countermovement against the military, the Democrat government, and the PAD. The network has undertaken various forms of resistance. One of its mottos is “anti-aristocrat,” in accordance with media technology and geographic networking.

On the second account, the political constraints in Thailand were due to deficiencies in the country’s democratic institutional mechanisms, due to which poor people were excluded from effective political participation while the central government controlled local resources, ranging from domestic revenue to natural resources, under the discourse of local interest being subordinated to national interest. While the democratic deficit at the national level came mainly from the failure of formal democracy and the closing of space for public participation, the possibility of achieving greater democracy at the local level was limited also because of the inadequate and slow process in transferring decision-making power to the grassroots and the low quality of local democracy. In the case of the UDD, although local democratic institutions cannot function or are unable to exercise democratic power, members of the network at the sub-district level are able to negotiate and gain some benefit for the local community with regard to poverty reduction projects at the local level and natural resource utilization in their area. Throughout the decentralization process in Thailand, there have been more resources available to local governments; but the central government still has the power and authority on issuing political agendas, providing budgets, and allocating personnel. If the local elites want to enrich themselves with these resources from the local governments, they need to have connections with the center.

Under the UDD’s “political educational scheme,” the network was able to expand its support base at the local level. Within one year, from 2008 to 2009, the UDD’s School Project was created and operated at least 400 schools in 35 provinces across the country. The UDD discourse is placed under three campaigns: electoral democratization, local access to economic liberalization, and putting an end to double standards and bringing about social justice. These discourses are used to support the network’s positioning in Thai politics. Members of the UDD network are from a wide variety of groups, both local institutions and individuals. For example, they include local canvassers of politicians, members of Tambon Administrative Organizations,14) leaders of community radio programs, self-employed and semi-skilled workers, subcontracted farmers, and low-ranking security officers. They are able to access policy schemes of the state and have expectations from electoral politics. It can be argued that a key character of the UDD network is social frustration. Its key active members or possible nodes of networking are from emerging economic and social classes, especially self-employed people and those who still have natural resources and are able to access commercial markets.

The UDD has a horizontal structure comprising networks of various forms of organizations and individual members. The network comprises various sub-networks, such as People’s Television Network members, provincial leaders/organizers, and members of opposition parties. Some 1970s activists have also grouped together and work with the UDD as advisers.15)

According to an interview with a UDD member, the organizational structure can be seen as a loose network of local sub-networks that consider themselves as the Red Shirts. Its task is to set up working political educational projects based on provincial networks. The provincial networks may control various local networks in order to represent the UDD’s network at the national level and make tactical decisions, including holding demonstrations or rallies to pursue the network’s campaign. There are varying numbers of group networks at the provincial level: for example, Ubon Ratchathani has 8 local networks of Red Shirts while Chiang Mai has 24. Each local network has its own community radio channel, from 1000 to 3000 MW, to propagate its own music, local folklore, and political issues of the Red Shirts locally and nationally.16)

In practice, however, there are debates within the UDD about the dominant role of national leaders, especially those from the People’s Television Network team and ex-activists, in crafting the organization’s political identity and political strategy as well as its agenda through their involvement with the political school project. For example, according to an interview with a UDD member from Chiang Mai, central leaders decided to continue protracted protests in downtown Bangkok while local sub-networks wanted to call off the demonstrations after the violence in April 2010. The creation of an identity of the UDD’s struggle as a struggle of “peasants vs. aristocrats” also came from intellectuals at the center (see Fig. 3 representing the organizational structure).

Fig. 3 Organizational Structure of UDD Network

Notes: 1) Although the three leaders of the UDD are Vira, Natthawut, and Jatuporn, Thaksin and his close network are seen as playing an advisory role in terms of decision making for rallies and networking. The financial role is seen to be played by Thaksin and his close ally (personal interview, April 10, 2010).

2) CPT: Communist Party of Thailand; PTV: People Television Network.

Most networks are not membership-based organizations and depend upon outside contributors (especially local politicians and political canvassers) for organizing and financing the network. The UDD’s campaign strategies and activities are also seen as political rallies by political society rather than self-governing civil actions by civil society. In the case of the UDD network’s organizations, their agendas range from the nonpolitical and nonideological to the idea of political justice in the belief that this would help bring back democracy and possibly former Prime Minister Thaksin.

In the Thai case, the politics of the UDD consists of a loose network of a wide variety of organizations that are not membership-based or made up of interest groups that are concerned only with the benefit of their members. The composition, however, is such that it contains groups representing different sectors and classes, whose alliance is issue-based under the motto of “anti-aristocrat, anti-double standards, and bring back Thaksin though our ballot box.” The UDD prefers to adopt a group-based representation as well as geographical model of representative politics and periodic elections. It also uses the politics of direct action without engaging in formal processes and institutional channels for political participation.

Under Thaksin, the Thai Rak Thai (TRT) used a participatory platform to formulate the marketing of its election campaign in 2001, which has continued to function as a hub of the network for coordination and as a focal point of the UDD. At the time, the TRT organized workshops with farmers’ leaders in every region to focus on rural problems and solutions as a starting platform before asking its academic staff and technocrats to analyze the situation and put forward concrete proposals that would appeal to voters. The UDD did the same thing with different audiences before pushing its campaign using these forums as a channel for its provincial publicity and political marketing campaign.

On the issue of widespread and broad-based participation, key UDD players disagreed with the communitarian philosophy that “the people know best.” They argued for the practicability and effectiveness of the state system that needed to be taken into consideration, and that public participation was only one among several methods of strategic formulation. In this regard, people needed to understand the concept of social obligations as well as social justice and use institutional channels to present their disagreements through voting in the general election. Thaksin himself did not believe that agricultural production was the way out of poverty, and he sought to eradicate poverty by encouraging farmers to become entrepreneurs by getting loans from the government to open small businesses or selling local products with support from the state.

The UDD still considers local interests to be subordinate to the national interest in the cause of infrastructure development and economic recovery, especially when the rhetoric of sovereignty is invoked. As the agenda of the rural-popular group may be different from that of incumbent politicians, these disagreements create further tensions and conflicts among network members. In the end, local networks of the rural and urban poor may fight against their leaders on several issues that affect their livelihoods, since their definition of social justice goes beyond personal politics to issues of redistribution of land, income, and progressive taxation.

On May 22, 2014, Thailand experienced another military coup. Since then, a military junta, going by the name of the National Council for Peace and Order, has governed the country. An oppressive post-coup political milieu has been one of the most influential factors in limiting the political role of the UDD and even fragmenting its network. The overall political situation from 2014 to 2015 reflected the weakening of Thai democracy and the political networks once active in the process of democratization. The UDD network, in particular, has been placed under considerable threat from the junta, which has used coercive means to deter or prohibit political gatherings of the UDD. For example, the military and the police regularly use Article 44 of the 2014 Interim Constitution to justify investigations, detentions, or any other curbs on the rights of anyone suspected of participating in activities deemed to threaten the security of the nation. Such repressive actions by the state’s uniformed forces have created a climate of fear that has forced UDD members to lie low, suspend their political activities, or go underground. The junta’s aggressive enforcement of lèse-majesté laws has also caused widespread anxiety and stifled the freedom of expression online, in print, via the broadcast media, and at public events. After the 2014 coup, new lèse-majesté cases have been brought before military courts that deny an accused person the right to formal appeal. Owing to the secrecy surrounding most lèse-majesté cases, it is unclear how many cases actually went to trial in 2014–15. Those cases, however, are believed to number in the hundreds. Already many people, UDD network members among them, have left Thailand to avoid being tried on charges of lèse-majesté. In short, the UDD has been seriously weakened. It is presently unable to revive its former concerns, let alone challenge the junta openly. Unless new, free, and fair elections take place, UDD members and their supporters are unlikely to be able to regroup and reconstitute their once substantial and influential networks. As long as the junta maintains its repression and threats, the future of the UDD network is rather bleak.

IV Conclusion: Network and Social Changes

To understand the networks of the PAD and UDD, we need to look at the structural design of Thailand’s democracy. While some elitists argue that the architecture of Thai political reform needs to address three main structural problems—corruption, inefficiency, and lack of political leadership—others argue for the realization that electoral politics alone cannot defuse conflicts over natural resources, which set the state against the people.

In the case of these two networks, the study demonstrates that both the PAD and the UDD are effectively challenging mainstream conceptions of Thai democracy in a number of ways. At the conceptual level, both networks have contested mainstream views on the link between democracy and participation, thus ensuring that direct participation of the people has been seen as both political and democratic. Their struggles show that democracy is most certainly not about election results alone. It is also about debate and dialogue on public policy decisions, especially when these decisions are related to people’s livelihood. The concerns of both networks are related to notions of democracy, the contested meaning of participation and empowerment—especially of people normally excluded from politics—and calls for economic equality and social justice.

Such political conceptions of democracy have been criticized as organizationally ineffective and threatening to institutional democracy and state power. In the case of the UDD, participatory democracy revealed its tendency toward the local rather than the national. The conception of a political imaginary arises from the macro level to micro-processes of participation and anti-institutional practices. These face stiff competition from alternative articulations of power, such as deal making with ruling politicians. The UDD perception of democracy is thus most profoundly tested when its resultant practices seek compatibility with mainstream political institutions.

Both the PAD and the UDD can be seen as cross-class networks that have adopted a dual strategy: engaging in the issue-based politics of being for or against a particular person or subject matter, and at the same time comprising a social grouping for the betterment of the people. Both networks use the politics of networking in associating those affected by particular political projects or state policies in order to mobilize different networks’ members into a common identity. Members of the network share the same perspective and are committed to being more engaged in political struggles because of reciprocal perceptions deriving from direct experiences. According to interviews with individual members who participated in the struggles, perceptions of the power relationship between themselves and the authorities changed markedly.

However, the success of such a strategy turns on the responses by the state. Political conflicts were often regarded as part of the problem of Thailand’s dysfunctional power structure, and the ideas of participatory democracy had little force when confronted by trends of authoritarian practice. The role of institutional democracy within existing political institutions thus became the decisive factor in the network’s success or failure.

The diversity of networks’ membership and the quality of their organizational character suggest that both the PAD and the UDD constitute oppositional politics hinging on particular topics or charismatic leaders rather than particular classes or political identities. In terms of political strategy in dealing with elected politicians, a number of the network members form alliances with political officeholders in order to achieve their demands. This disparity of commitment created conflicts among movements’ networks and involved key players at all levels. Using extra-parliamentary politics against mainstream electoral institutions also reflects a negative perception of the established middle classes toward the emerging middle classes. For example, many PAD members believed that the UDD’s protesters were being manipulated by Thaksin and his followers, based on political interests.

Since the 2014 military coup, however, Thailand’s political networks have entered a critical period of examination. In contrast to other recent military coups, the coup of 2014 saw a particularly strong reassertion toward the creation of a neo-authoritarian state. The military government is represented by nationalist leaders who have tried to establish a new political legitimacy built upon their control over their bureaucratic subordinates and the mechanisms of state. The government does not only have an authoritarian culture of authority, but it also gains support from non-elected mechanisms, including the bureaucracy, military, and royal elites (Pye 1985, 321–325). It may be argued that this situation is intended to transform Thai politics from a hybrid regime or electoral authoritarianism to a full authoritarian regime. In this context, an organized political network has been set up by the state to protect the conservative wing. In other words, the government and its allies may move from yellow to blue and/or dark green networks.

In the end, critics of both networks would argue that they are essentially interest groups, invoking constructs such as moral politics, new politics, and the serf versus the aristocrat to legitimate their interests. By using the argument that political democracy would help promote socioeconomic equality, both networks were able to unite and turn their members into a political force, since the meaning of democracy becomes related to the issue of access to power by ordinary citizens.

In Thailand’s complex and rapidly changing market-oriented society, many social groups have higher expectations of a democratic system. For them, democracy is an electoral method of political competition. They, therefore, conduct themselves as political consumers who can choose between political products or policies offered by competing parties and politicians (Schumpeter 1954, 269-283). In other words, the two contesting networks effectively offered different proposals that actually came from their respective elites. Throughout the study, institutional assumptions of liberal representative democracy are challenged along three dimensions: as contesting perspectives of democracy, as an example of dynamism arriving from initiatives and practices of the networks, and as a case of practical struggle demanding for more participation in mainstream Thai politics. Through the study of the PAD and UDD, this paper provides a deeper understanding of the dynamism and contentious politics of these two political networks and their impacts on Thailand’s democratic polity.

Accepted: January 21, 2016

References

Announcement of the Election Commission. 2011. Re: Results of Election of the House of Representatives dated 12 July, 2011. Government Gazette 128, Part 58A.

Bamford, A.; and Chanyapate, C. 2006. The Monarchy and Political Crisis in Thailand during Thaksin’s Period. March 6. Unpublished document.

Callahan, William A. 1998. Imagining Democracy: Reading “The Events of May” in Thailand. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Hewison, Kevin. 2000. Resisting Globalization: A Study of Localism in Thailand. Pacific Review 13(2): 279–296.

―, ed. 1997. Political Change in Thailand: Democracy and Participation. London: Routledge.

Mansbridge, Jane. 2001. Complicating Oppositional Consciousness. In Oppositional Consciousness: The Subjective Roots of Social Protest, edited by Jane Mansbridge and Aldon Morris, pp. 238–264. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

McCargo, Duncan. 2006. Balancing the Checks: Thailand’s Paralyzed Politics Post-1997. Journal of East Asian Studies 3(1): 129–152.

―. 2005. Network Monarchy and Legitimacy Crises in Thailand. Pacific Review 18(4): 499–519.

McCargo, Duncan; and Naruemon Thabchumpon. 2014. Wreck/Conciliation? The Politics of Truth Commissions in Thailand. Journal of East Asian Studies 14(3): 377–404.

―. 2011. Urbanized Villagers in the 2010 Thai Redshirt Protests: Not Just Poor Farmers? Asian Survey 51(6): 993–1018.

Mydans, Seth. 2008. Power of the People Fights Democracy in Thai Protests. New York Times. September 12.

Naruemon Thabchumpon. 2012. Thailand: Contested Politics and Democracy. http://www.peacebuilding.no/Regions/Asia/Publications/Thailand-contested-politics-and-democracy, accessed October 22, 2015.

Nithi Eawsriwong. 2002. Ten Years of May 1992 and the Memory, a keynote speech to commemorate 10 years of the May 1992 events. In Memory of the May 1992 and the Future of People’s Politics, edited by Boonthan Tansuthepveravong pp. 5–15. Bangkok: Plan Printing.

Pye, Lucian W. 1985. Asian Power and Politics: The Cultural Dimensions of Authority. Cambridge, Mass., and London: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Schumpeter, Joseph A. 1954. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, 4th edition. London: Allen & Unwin.

Seangtham Chunchadatan. 2010. Street Politics of Ordinary People: Different Perspectives of Multi-Color Glasses, accessed October 22, 2015, http://www.prachatai.com/journal/2010/09/30968.

The Times. 2009. Thailand’s Yellow Shirt Leader Sondhi Limthongkul Survives Assassination Attempt. April 17.

Thitinan Pongsudhirak. 2014. Learning from a Long History of Coups. Bangkok Post, June 6. http://m.bangkokpost.com/opinion/413829, accessed August 11, 2014.

Uchane Cheangsan. 2013. Techniques and Movement’s Strategies of the People’s Alliances for Democracy. https://www.academia.edu/1115777/%E0%B8%A2%E0%B8%B8%E0%B8%97%E0%B8%98%E0%B8%A7%E0%B8%B4%E0%B8%98%E0%B8%B5%E0%B8%81%E0%B8%B2%E0%B8%A3%E0%B9%80%E0%B8%84%E0%B8%A5%E0%B8%B7_%E0%B8%AD%E0%B8%99%E0%B9%84%E0%B8%AB%E0%B8%A7%E0%B8%82%E0%B8%AD%E0%B8%87%E0%B8%9E%E0%B8%B1%E0%B8%99%E0%B8%98%E0%B8%A1%E0%B8%B4%E0%B8%95%E0%B8%A3, accessed October 22, 2015.

1) Interviews with PAD members were conducted twice: in early 2009, after PAD members seized Bangkok airports; and in 2014, at the PAD stage in front of Government House during the People’s Democratic Reform Committee’s Bangkok Shutdown campaign. UDD members were interviewed in March and April 2010, during the big rally against the Abhisit government. Due to the political situation in Thailand, the interviewees shall remain anonymous.

2) These political parties were Thai Rak Thai (1998–2007), the People Power Party (2007–08), and Phue Thai (2008–present).

3) Thaksin Shinawatra is an ex-police officer and telecommunications tycoon. He was ousted from power in the September 19, 2006 military coup d’état. While Thaksin has been in self-imposed exile, he remains a hugely influential figure on the Thai political scene.

4) In the beginning, the CDR was self-proclaimed as the Council of Democratic Reform for Constitutional Monarchy. Later, the words “for constitutional monarchy” were removed to avoid international criticism.

5) After returning to Thailand in February 2008, Thaksin went into self-imposed exile that August, to avoid serving an anticipated jail term for corruption-related offenses.

6) Many scholars have argued that the judicial decision was made under pressure from the PAD’s political protest, especially with the seizure of Suvarnabhumi Airport.

7) Interviews with members of these networks were first conducted between August and October 2009, one year after the PAD seized Bangkok airports. Some groups were then revisited during the People’s Democratic Reform Committee’s Bangkok Shutdown campaign in early 2014 in order to see the similarities and differences between the networks. The total numbers of expert interviews from the PAD at the time were 30 people from 13 groups under this network.

8) Interviews with PAD network members, August 10, 15, and 25, 2009.

9) Interview with PAD leader, October 10, 2009. It was approximately one year after the PAD’s street blockades and occupation of Government House in 2008.

10) Personal interview with two members of the TTS, a network of the royal jet set that supports the PAD, June 8, 2010.

11) Seangtham’s political role could be seen also during the People’s Democratic Reform Committee (PDRC)’s Bangkok Shutdown campaign in 2014. For more details, see http://www.komchadluek.net/detail/20131228/175730.html, accessed October 22, 2015.

12) Under these circumstances, the state is not just playing the role of a normal developmental state that allocates national resources on selected issues, but it can be considered as a developmental authoritarian state as it puts electoral democracy aside while those in power taking the lead in developing the country’s economy are from its trusted networks, while civil society plays a role as a civic state from the patriotic point of view.

13) Personal interviews with UDD members were conducted between March and April 2010, before the government cracked down in May 2010.

14) A Tambon Administrative Organization is the smallest unit of local government in rural areas, while urban areas have municipalities. TAO leaders are elected every four years.

15) Some 1970s student activists who work with the Thai Rak Thai party, mostly from the North, can be considered as network members of the UDD. Other activists from Bangkok, such as the Dome Ruam Jai group (Thammasat alumni student activists), consider themselves as sympathizers of the UDD.

16) Personal interview, March 18, 2010. For more details, see McCargo and Naruemon (2011).