Contents>> Vol. 6, No. 3

The Extension of State Power and Negotiations of the Villagers in Northeast Thailand*

Ninlawadee Promphakping,** Maniemai Thongyou,*** and Viyouth Chamruspanth†

* This article is part of a Sociology dissertation in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences,

Khon Kaen University, titled “The Construction of Social Space by the Thai Nation Development

Cooperators of the Phutai Ethnic Group.”

** นิลวดี พรหมพกั พงิ , Research Group on Wellbeing and Sustainable Development (WeSD), Faculty

of Humanities and Social Sciences, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen 40002, Thailand

Corresponding author’s e-mail: npromphakping[at]gmail.com

*** มณีมัย ทองอยู่, Center for Research on Plurality in the Mekong Region (CERP), Faculty of

Humanities and Social Sciences, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen 40002, Thailand

† วยิ ทุ ธ์ จำ รัสพนั ธุ์, Department of Public Administration, Faculty of Humanities and Social

Sciences, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen 40002, Thailand

DOI: 10.20495/seas.6.3_405

Keywords: Phutai, nation-state building, ethnic identity, social space, symbolic capital, minority

Introduction

During the history of Thai nation-state building, the central state expanded its power both physically and politically to maintain control and supervision over outlying areas. The extension of power was initially an effort to build unity in order to resist the influence of Western colonialism (Thongchai 1994), which had extended its power into Southeast Asia. Western colonialists annexed parts of land that had previously belonged to Thailand, at that time known as Siam. In response, the Thai state staged a series of reforms that allowed it to maintain its sovereignty over the main part of what is today Thailand1) (Pasuk and Baker 1997; Wyatt 1982) and avoid being formally colonized by Western powers.

The reform, as part of the process of nation building, can be seen as the first modern creation of political space by the state in Thailand, that is, the process of using the power of the state to control outpost areas, which has continued to the present day. Through the reforms, the state introduced a new governing system that allowed the central government in Bangkok to directly control the population. In these reforms a prefecture (monthon มณฑล) replaced the provincial governor system (jao mueang เจ้าเมือง), outpost lands were systematically surveyed and registered, and all Thai citizens were required to record their names on their house registration documents. The prefecture governors were appointed by the central government in Bangkok, a change that reduced the power of the former governors. The result of the reform was that outpost areas, which previously had been relatively independent, were incorporated into and managed by the central government (Suwit 2002), a process that characterizes internal colonization (Hind 1984).

Because of the extension of central state space, the former governors lost power; and consequently, they opposed the government officers who had been sent from the central state. Moreover, the new tax collection system caused hardships and ignited the people’s opposition to the central state. For example, abolishing the opium tax in 1910 led to opposition by concessionaires, Chinese communities went on strike against an increase in the poll tax,2) etc. The addition of new taxes, particularly the poll tax, in which the tribute system (people paying tax to the state “in kind” with materials) was replaced by a cash system, caused great difficulty for the people, most of whom were poor. The expansion of state space thus met with resistance not only from local governors but also from the population living in outpost areas. One important resistance movement by the population to the expansion of the state space was the Holy Men’s Rebellion (Kabot Phibun กบฎผีบุญ) (Ted 2008; Saisakul 2012; Baird 2013). Nevertheless, the Thai state’s modernization, or nation building, was successful; and before World War I all outpost areas were fully and politically integrated.

After World War II the Thai state faced a new threat with the growing influence of Communism. In response to this threat the state extended its space, but this time it did so differently from previous times. The new approach was to focus on using political ideology along with violent suppression of dissidents. Through mass media, such as radio and signboards distributed to villages nationwide, Communism was painted as evil and dangerous. In 1952 the government issued anti-Communist laws that were harshly enforced, particularly during the government of Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat (1959–63) and the Thanom–Prapat regime (1963–73). The expansion of state space, in this case the enforcement of anti-Communist laws, led to conflicts between the state and the people. A great number of people joined the Communist Party of Thailand (CPT), seizing the outpost spaces as their strongholds. Battles between the state and the CPT caused hardships and difficulties for the populace. At the beginning of the 1980s, however, the state adopted a new policy called the “political-led military policy,” which put a halt to violent suppression of dissidents (Lowe 2009; Chao 2010).

This paper explores the expansion of state space into outpost areas and the response of local people to the ending of the conflict between the Thai state and the CPT. Many previous studies have stressed that throughout history the state successfully asserted its control through development projects and so gained supremacy over outpost areas. This paper argues that the expansion of state space does not necessarily mean that the people are entirely submissive to state power. Rather, within the field of forces dominated by the state, people can employ the image painted by the state, such as the image of Communism, to engage and negotiate their relationship. The empirical analysis of this paper is based on phenomenological research on a village that was conceived by the state as a “Communist village.” The state’s creation of space and the people’s negotiations cover the period from the CPT war up to the present.

Theoretical Framework

In sociological circles, there have been explanations from diverse theoretical perspectives on the above-mentioned phenomenon of a state’s expansion of power for local control and management. However, the widely accepted mainstream explanation is the modernization perspective. The modernization process was started during the reign of King Rama V, when outpost areas were gradually incorporated into the central government in Bangkok. According to this explanation, the Thai state employed administrative mechanisms that were modernized to advance Bangkok’s power into areas that previously had been ruled by local governors. Modernization was conceived as reforms implemented during the reign of King Rama V. In addition, modernization that took the form of the expansion of state mechanisms continued after Thailand adopted the National Economic and Social Development Plan, which began in 1960.

Amid the rise of Communist influence in rural areas, the state created new government agencies, such as the Department of Rural Development and Bureau of Rural Development Acceleration (with significant support from the United States Operations Mission). The National Institute of Development Administration was established in 1966 to promote and support the modernization of state agencies through postgraduate training for development and administration personnel. These state agency modernizations were coupled with “economic modernization,” which initially involved infrastructure building and import substitution development strategies. The modernization of agriculture through the green revolution—involving the introduction of various cash crops (Pasuk and Baker 1997; Maniemai 2014)—which came later, in the mid-twentieth century, was also instrumental in the expansion of the state agency into rural areas. However, it is argued that the later modernization of the Thai state focused on economic modernization, while politics was hardly modernized (Chatthip 2010). Political modernization focused on incorporation into the central state as well as increased state control over the population.

It has also been argued that the modernization theories mentioned above give too much weight to external factors as the primary causes of modernization. This view fails to take into account communities’ history. It does not appreciate agencies outside of the state mechanism, such as dissidents and non-state representatives. Presently, even though the research takes into account the limitations of mainstream concepts, such concepts still influence economic and political development. For example, under the political turmoil that Thailand has been experiencing for almost a decade, efforts have been made to design constitutional law to increase the power of the state bureaucracy. Therefore, these are all “symptoms”—attesting to the influence of mainstream concepts and theories.

This paper sees state power as a “field of forces,” and therefore a theoretical perspective concerned with social space will be adopted to guide the investigation and analysis. According to Pierre Bourdieu (1930–2002), a social space contains numerous subfields, and each subfield consists of networks of people who try to win or own powers to create rules and regulations that will be eventually articulated into positions. Those who hold these positions will individually or collectively find ways to safeguard or improve their positions (Bourdieu and Wacquant 1992). In other words, power is defined by positions contained in the subfield, and the struggle to maintain or improve positions within these subfields structures the control of space (Bourdieu 1989).

The above concepts of space and field of forces inform the analysis of this paper, which first discusses the materials and methods through which empirical data were obtained. This discussion is followed by the presentation of findings and discussions of the incorporation of outposts into the central state, the battle for control of space, the regaining of political space by the state, and the people’s negotiations under state space.

Methodology

The information required to understand the negotiations of villagers is concerned with everyday practice. In order to pursue this aim, the phenomenological research method (Holloway 1997) was adopted and research was conducted in an ethnic minority village, which was given the pseudonym of Ban Phasuk (บ้านผาสุก), literally meaning “the village of happiness.” The researcher spent several weeks building rapport with villagers, and therefore emic views of the villagers could be obtained. In building good relationships, the researcher benefited from having the same ethnicity as the villagers of Ban Phasuk and being a native speaker of the local dialect.

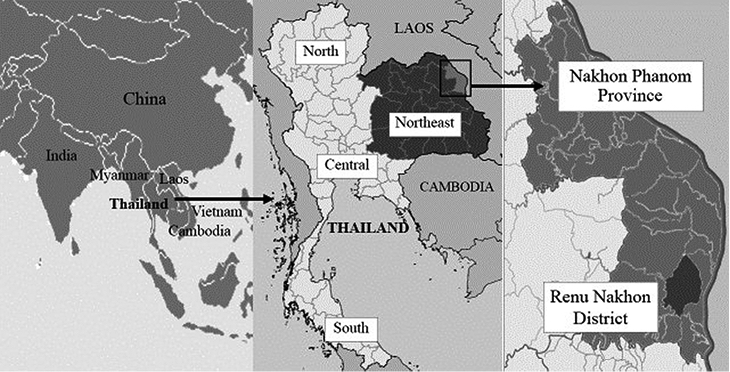

Fig. 1 Map of research site, showing Renu Nakhon District of Nakhon Phanom Province. Ban Phasuk is located in Renu Nakhon District.

Sources: Applied from https://www.google.co.th/search?q=southeast+asia+map; https://th.wikipedia.org/wiki/ภาคอีสาน_(ประเทศไทย) and https://th.wikipedia.org/wiki/อำเภอเรณูนคร, accessed January 12, 2016.

In order to obtain required information, the researcher identified 32 villagers for interviews. The main criterion for selection was that these villagers had the experience of being affiliated with the Communist insurgency and living in the village from 1965 to 1981. In addition, six villagers who joined the Communist movement and later became Thai Nation Development Cooperators were selected for in-depth interviews. The interviews were conducted mainly in Ban Phasuk. Some Thai Nation Development Cooperators were interviewed on Phutai Day (wan phutai วันภูไท), organized by Renu Nakhon District, and on the occasion of remembering the First Gunfire Day (organized on August 7 in Ban Phasuk village). In addition, a focus group discussion was organized consisting of leaders—including the village head—members of the Tambon Administrative Organization, and schoolteachers. The purpose of the discussion was to obtain a picture of state actions at the local level.

Ban Phasuk is a Phutai village in Renu Nakhon District, Nakhon Phanom Province. In terms of socioeconomic conditions, the village is similar to most other rural villages in Northeast Thailand. The people of Ban Phasuk traditionally earned their living from agriculture, but during the past two decades their sources of livelihood have greatly diversified. A significant number of young and working-age people migrate to seek jobs outside and then remit part of their income to support those who remain in the village. The socioeconomic development of Thailand, along with government development programs, has significantly raised the villagers’ standard of living, especially during the past three decades.

What is distinctive about Ban Phasuk, when compared to other rural villages, is that its villagers had the experience of joining the CPT in staging an armed fight against the Thai state. One significant event was a gunfight between the villagers and the authorities that broke out on August 7, 1965 and led to the day being declared the First Gunfire Day, symbolizing the armed fight by the CPT to win power. This village’s experience reflects the response of local people to the expansion of state power, details of which will be discussed below.

The Incorporation of Outside Space into the Central State

Like many other states in mainland Southeast Asia, the Thai state, previously known as Siam, had limited control over its outposts, although official historical documents claim sovereignty and control over large areas. Reforms, initially staged under King Rama V, served to annex the outposts, which previously were relatively independent, and make them part of the central Thai state. The incorporation of the outposts, although successfully achieved, caused many hardships for the local people, which gradually fomented resistance.

Renu Nakhon is a district in Nakhon Phanom Province. The provincial capital of Nakhon Phanom is located along the Mekong River, opposite the town of Tha Kaek in Laos PDR. Most of the people in Renu Nakhon District are of Phutai ethnicity. Historically this Phutai group consisted of war captives who were forced to move from Laos to Thailand in the early Ratanakosin period. In the beginning Renu Nakhon leaders made attempts for their district to be recognized by Bangkok as a mueang (city), in order to have their own administrative system. Bangkok finally granted the status of mueang to Renu Nakhon,3) and some important governors are still remembered, including Phra Kaeo Komon (พระแก้วโกมล) and Thao-Sing Kaeomanichai (ท้าวสิงห์ แก้วมณีชัย: 1888–94). It is appropriate to note here that during the early years of Renu Nakhon, the leaders attempted incorporation into Bangkok rather than seeking independence because Bangkok’s protection against Vientiane and other powers was most important to them.

However, the Phutai have also attempted to maintain their ethnic identity. Inhabitants of Renu Nakhon usually refer to the town as Mueang Wey (เมืองเว), the name of the town where they lived before they became war captives. The ethnic identity of the Phutai has been accepted by the state and become a valuable resource for the tourism that has been promoted in the past decades, which will be discussed below.

Ban Phasuk was established around 1891, and its founders and inhabitants are Phutai, the same ethnic group as the people of Renu Nakhon. However, the location of the village is around 12 kilometers from Renu Nakhon district town. Road access 40 years ago, especially during the rainy season, was difficult. The reason for founding the village was to limit cultivated lands near Renu Nakhon district town. With population growth, people extended their cultivated lands farther and farther and finally formed new villages. Although the people of Ban Phasuk and Renu Nakhon District share the same origins, there remain some distinctions. For instance, the Phutai of Renu Nakhon believe in the town shrine spirit called Pu Thala (Grandfather Thala deity ปู่ถลา), the spirit that loves or craves raw buffalo meat. The Phutai of Ban Phasuk, however, feel that such a belief results in the killing of buffalo, which obviously goes against Buddhist teachings. Moreover, in the researcher’s experience, the people of Renu Nakhon and those of Ban Phasuk view each other differently. The former view the latter as Communists, while the latter view the former as jao nai (เจ้านาย), or officials.

During the administrative reform period, under King Rama V, Renu Nakhon like other mueang underwent changes, i.e., the power of the governor system slowly dissolved. Based on the prefecture or modern administrative system, the status of Renu Nakhon town was lowered to a mere subdistrict (but later, in the 1970s, it was raised again to a district). Originally, Ban Phasuk was referred to as a cluster or khum ban (คุ้มบ้าน). Later it became a village, or ban (บ้าน), which is the smallest unit of state administration. Moreover, the title of the village leader was changed from ja ban (จ่าบ้าน) to phuyai ban (village head ผู้ใหญ่บ้าน). In other words, the appointment of a ja ban was originally based on seniority and respectability, but under the modern administrative system the village head was someone who would serve as an intermediary between the village and the central state. The village heads acted as intermediaries bringing policies, announcements, or orders from the center to the villagers for implementation. The head of the village therefore came to be viewed by the villagers of Ban Phasuk as an official. Through these changes, the state incorporated the villagers of Ban Phasuk into the center and expanded and tightened its control over all aspects of their lives. While the expansion of state power benefited the local population in some ways, it also gave rise to a discontent that had the potential to grow and develop into resistance.

With regard to the economic aspect, first, through its promotion of the rice trade the state extended its power. Consequently, the community, which used to have a subsistence economy, became a market-dependent system. To increase the agricultural area in order to grow a greater amount of rice, large areas of forestland were cleared. Moreover, because the villagers had to make payments to the state and because the external market was expanding, they needed more money to buy consumer goods. Rice and forest resources were goods that they could produce or find locally. Production for subsistence was replaced by production for sale. As a result, the rural households’ economic course began to depend on external markets. The state from that time on extended itself into the village and held power over the villagers, who had become producers.

Second, the issue of tax collection had a great impact on the villagers of Ban Phasuk. After the administrative reform begun during the reign of King Rama V, the state sent government officers from Bangkok to collect taxes. Prior to this time tax was collected in the form of corvee labor (suai ส่วย) in which all able-bodied men were subject to conscription for public works and wars. However, corvee labor or suai could be paid in the form of valuable goods such as silk, gold, etc. The latter form of tax was most common in the case of outpost cities; most Isan cities were far from Bangkok, and transportation was difficult. After the reform, tax was imposed in the form of money, replacing corvee labor. At first, 3.50 baht per able-bodied man was collected. Later, in 1901, the rate was increased to 4 baht per able-bodied man (Suwit 2006). Furthermore, farmers were required to pay a rice cultivation tax. As a result of these collections, from 1892 to 1927 the state’s income continuously increased.

The collection of tax in the form of money had a great impact on the living conditions of Ban Phasuk villagers. One villager said the following:

. . . At that time, when it was time for the government to enroll labor, district officers would come to meet the village head. The village head knew well which able-bodied men in the village would be able to work as laborers or to carry out “public works.” If someone had 4 baht to pay as capitation, he did not need to be enrolled as labor. However, very few people had the money to pay. At that time, carrying out public works was like being a slave because one had to do whatever the master ordered. Most of the work was labor. The laborers became fatigued and were worried about their families. Particularly if the public works enrollment period coincided with that of rice cultivation, the laborers would be all the more worried about their families because of the shortage of labor. (Interview, May 10, 2013)

From the statement above, it is apparent that at that time Ban Phasuk was hardly integrated into the Thai monetary economy. After the rice cultivation season, many men had to leave their villages to earn money to pay the new tax. Some became cloth traders, some joined cattle trader caravans, and some crossed the Mekong River to find work in the towns of Khammouane (คำม่วน) and Savannakhet (สะหวันนะเขต) in Laos. In those days, citizens had a hard time earning income in the form of money to pay government taxes. Consequently, the people viewed the state in a negative way.

In order to fit within the space of the state, Phutai people needed to be molded into the “Thai” pattern. Minority ethnic groups were generally seen by the state as “the other”—different from Thai. As pointed out by Thongchai Winichakul in “The Others Within: Travel and Ethno-Spatial Differentiation of Siamese Subjects 1885–1910” (2000), ethnographic construction was one of colonization’s plans for defining and controlling “the others.” In order to obtain information, rulers from the central region engaged in journeys, surveys, and ethnographic differentiation. They kept travel records and ethnographic notes in order to classify the rites and beliefs of local people that were strange and different from those of the central state. An ethnic group was conceived as an “other” that was living within the state space. Previously the Thai state referred to people living in outpost areas as chao pa (forest people ชาวป่า). The incorporation of ethnic minorities into central Thailand was done in various ways, with the most important one being through the education system. To a certain extent, however, the sense of otherness of ethnic minorities remains.

As for the villagers, in the beginning, to obtain an education they entered the monkhood. After the state’s extension of education to the provinces, in 1938, Ban Phasuk had its first school. However, because of the state school’s budgetary constraints, villagers used a pavilion in the temple for classes. Most villagers did not continue their studies after completing Primary 4 since the village was far from the secondary school, which was located in the town of Nakhon Phanom. Therefore, male villagers still preferred the traditional method of education, i.e., entering the monkhood for basic education and then crossing the border to Laos (which at one time was part of Siam) to study the Buddhist Dharma as traditionally practiced. However, such knowledge could not be used in the modern Thai bureaucracy—not only because it used the Lao alphabet, but also because it was confined to the principles and teachings of Buddhist ideas of merit and demerit. Consequently, villagers at that time, in the eyes of government officials, were viewed as “others” as the majority had not received education in the government school system. In addition, they had a greater sense of kinship and closeness with people in Laos than with the government officers sent by the central body to administer them.

A Battle for Control of the Space

The incorporation of outposts into the central state and the enforcement of state policies upon local people led to mounting tensions between local people and the authorities. After World War II, a conflict broke out between the Thai state and the CPT in which the state employed its armed forces to suppress the CPT. The violence spread to large parts of the country. The fight between the state and the CPT can be seen as a battle for control of space—not just physical space but also political and social space. Ban Phasuk was involved in this battle, as we will see.

The CPT was formed after World War II, initially by Sino-Thais based in Bangkok. In the beginning, the Party’s underground campaign aimed to win support from workers in Bangkok. Later, in the 1960s, the CPT directed its campaign toward farmers in rural areas of the country. In 1953 the government had issued a law that made the Communist movement illegal; consequently, the CPT became an underground movement. In 1969 the Ministry of Interior declared that large parts of the Northeast, the North, and the South were infiltrated or red areas in which the CPT was active. University students, although an important alliance of CPT, joined only later, in the 1970s, especially after the October 6, 1976 massacre at Thammasat University in Bangkok, when significant numbers fled to join the CPT in the jungle. The change from an urban base to “the countryside surrounding the cities” resulted in the Communist movement creating strongholds in rural areas (Murashima 2012). Around 1959–61, Ban Phasuk was another farming village in which Communist ideology was being spread. A villager described one of the leaders, Mr. Chom Sanmit, as follows:

We also didn’t know who he was. We only knew that he was a Khon Kaen man. He was an intellectual because he had knowledge. He was able to do many things. He could speak many languages—English, Chinese, Russian, and Vietnamese. He was eloquent, he had principles, and he was believable. Moreover, he was a doctor—he injected, acupunctured. He cured many villagers but didn’t take any medical fee. So we thought that he was a good person, in that he had come to help us while we were in difficulties. Later on, the news spread that there was a doctor who healed free of charge. At that time, he fully won the hearts of the villagers. (Interview, May 12, 2013)

Mr. Phumee, another leader, became an important person because of his proficiency, capability, and assistance to the people during their times of hardship. The number of villagers who became interested and came to listen to his elaboration of Communist ideology kept increasing. A female villager said the following:

The first time I listened to him, I felt very impressed. He said that those who joined the Communist Party would have equality. Those who wanted to study would have a chance to do so. Those who wanted to study to become a doctor would have the opportunity to do so. You could become whatever you wanted. In my mind, I dreamed of studying to become a doctor so that in the future my life could be better and more comfortable. He also said that in the past we were Lao people—the same as people in Laos. We were brothers and sisters. We all ate sticky rice. Therefore, Thai people looked down on us. The government had not cared for or assisted us. Furthermore, it was allied with America. We had to join hands to protect our nation. At that time, after listening to him, we felt motivated—eager to go out to fight for the nation. (Interview, May 10, 2013)

After hearing about Communist ideas, people believed that they had hope for a better life. Consequently, a number of villagers volunteered to join the Party and traveled to Mueang Mahaxay (เมืองมหาชัย), in Laos’s Kammouane Province, to attend political and military training. After listening to Marxist-Leninist ideas, villagers felt that cooperation in fighting would bring victory to the people. Later, Communist ideas spread to other villages. Eventually, many groups of villagers volunteered to travel to Mueang Mahaxay to attend political training. Later, Ban Phasuk’s villagers joined in an alliance with the Communist Party that led to violent events in the village. The first deadly armed battle between villagers and police occurred on August 7, 1965. Based on this incident, the CPT announced its armed fight against the government. This was the background of the First Gunfire Day, Wan Siang Puen Taek (วันเสียงปืนแตก) (Somsak 2009; Suthachai 2010). The fighting was used by the Communist Party as a symbol of armed struggle. The villagers were viewed as enemies of the nation, and from then their lives took a turn for the worse. Government officers violently suppressed them. They were also charged with taking part in Communist acts. Villagers were arrested in an excessively harsh manner. Many villagers who had not been involved were unjustly arrested and physically harmed. A villager who had been part of the events said the following:

The masters, or jao nai [officers], came to our village and accused us of being Communists. They were not interested in listening to us—even a little bit. They caught and took away villagers, both men and women. (Villagers) were slapped, beaten, pounded, and hurt—as if they were not human beings. That was when some villagers did not even know what Communist meant. However, all of them were arrested. At the time, the number of villagers who had been arrested was very high. The prison became overcrowded. Some of the prisoners were chained and tied to poles under the sun and rain. Ants were allowed to bite them. The masters [officials] could do whatever they liked. At that time, the village was filled with fear. Many villagers, after being released and returning home, died due to internal bruises. (Interview, May 12, 2013)

Regaining National Ideology and Political Space

From the early 1980s the influence of Communism declined significantly, and consequently the state resumed control of most of the outpost areas that had been under the control of the Communist insurgencies. The decline of the CPT was not because of violent suppression by the military. Rather, it was a result of the change in the state’s view of Communism, following the policy of the Prime Minister’s Office Order 66/2523. This policy enabled the state to regain political space, gradually leading to an end to the fighting between the CPT and the state. However, the CPT’s decline was due also to the withdrawal of international support to the Communist movement in Thailand. In 1979, conflict between Vietnam and Cambodia affected Communist activities in the Indochina region, including those of the CPT (Tamthai 2003; Thikarn 2010). Vietnam’s invasion of Cambodia intensified the conflict between China and Vietnam. Consequently, Laos stopped allowing the CPT to train in Laos because the Party backed China while Laos sided with Vietnam. Moreover, the CPT itself had faced an internal conflict between its leaders and students. The conflict resulted in some students deciding to leave the Party (Por 1989).

In order to insert state power into the political space, and following the announcement of the “political-led military policy” (Prime Minister’s Office Order 66/2523), the Thai state took a number of measures. First, it agreed that those who had joined the CPT would no longer be prosecuted if they returned and “cooperated” with the state, even though the anti-Communist activities continued. The Thai government assigned the Internal Security Operations Command (ISOC) to take responsibility for the surrender of previous Communist comrades, who were then relabeled as Thai Nation Development Cooperators (Phu Ruam Phattana Chart Thai ผู้ร่วมพัฒนาชาติไทย). The ISOC then established a training center called Karunya Thep (God of Mercy การุณยเทพ) at military camps in Sakon Nakhon and Nakhon Phanom Provinces, for those surrendering to “correct” their political attitude. As a result, most of the dissident Communists returned and reentered the state’s political space.

Second, the Thai government declared August 7, 1979 as Wan Siang Puen Dab (วันเสียงปืนดับ), literally, the Last Gunfire Day. As mentioned earlier, the CPT announced the event of the gunfight between villagers and authorities that occurred in Ban Phasuk on August 7, 1965 as the First Gunfire Day. The official announcement by the CPT was a signpost of political space, set to expedite the movement to win over the space using an armed fight. The declaration of Wan Siang Puen Dab by the state was thus the anti-signpost, denying and removing the influence of the CPT from the political space (Ninlawadee et al. 2014).

With the students’ return to the state’s political space, ideological differences between the state and the local population seemed to have been resolved. Ban Phasuk returned to normalcy. Its inhabitants were comfortable entering into the new political space created by the state. Although there was a lack of necessities and state services in the village, residents had more freedom when it came to earning their livelihoods. Many householders decided to move to Bangkok to seek jobs. The ex-CPT members who chose to continue earning a living in the village, however, were faced with a number of problems. A previous comrade recalled the following:

At that time we were always accused of being Communist. People outside did not understand us. They looked at Phasuk villagers as the bad guys. In the past people used to come to the village to exchange food. When incidents occurred, they were afraid to come. (Interview, May 12, 2013)

Although the accusations and discrimination against villagers based on the stigma of Communism faded, those who returned to earn their living in the village were faced with new problems. As in the case of many other villagers, earning a living from agriculture was barely sufficient. A number of people migrated to seek jobs in Bangkok, while some went overseas—to Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Brunei, Taiwan, etc. Faced with these problems under the new political space, the villagers of Ban Phasuk were not passively accepting. Instead, they actively engaged and negotiated their relationships.

Negotiation of Relationships within the State Political Space

As discussed above, the state successfully resumed the political space that had been under the influence of the CPT. Villagers who had fled to the jungle returned to the village. Comrades surrendered to the authorities and adopted the status of Thai Nation Co-developers. In the wider context, the growth of democracy opened a new political space for villagers. After the end of the conflict in the mid-1980s, the state became more open to social activism. NGOs were permitted to operate for rural development, and consequently the activities of NGOs, mostly funded by international donors, were galvanized. A number of urban middle-class social activists, students who had previously joined the CPT, changed their roles to become NGO workers (Bello et al. 1998). NGO work or civil society movements have become a subfield under state political space. Ban Phasuk villagers were able to establish networks with NGOs or social activists, and these networks became supportive of their actions.

In the local context, villagers employed many platforms to negotiate their relationships, including the following.

(1) As mentioned previously, the gunfight between villagers and authorities on August 7, 1965 was celebrated as the First Gunfire Day by the CPT. After the end of the conflict, in 1979 the government announced August 7 to be Ceasefire Day. A decade later, the villagers revived the history of the First Gunfire Day. In its first years (2002–04), the ceremony was not supported by the government because of its concern over the return of Communism or conflict. However, the ceremony was supported by networks of the participants for Thai national development—they used the First Gunfire Day at Ban Phasuk as a symbolic ceremony. To revitalize the ceremony, Ban Phasuk villagers obtained ideas by attending Memorial Day ceremonies organized by comrades of the previous Southern and Southeast Liberation Regions. The ceremony, once established, enhanced the negotiations of the villagers in a number of aspects. First, the ceremony of the First Gunfire Day provided a platform to create networks for the villagers, and these networks became a kind of capital asset (Putnam 1993) for the villagers, underpinning their actions, including negotiations with the state. Second, the ceremony provided a new image for the villagers: from being seen as Communist insurgents, they came to be seen as people who were dedicated to society. Third, the villagers broadcast their history, using the ceremony as an event through mass media, so they were known and supported by the public.

(2) The villagers of Ban Phasuk formed the 7th August Volunteer Club for Development in 2003. The club was designed to be a platform for coordinating activities with the state. One important activity was the state-sponsored village contest project; the club proposed a “Diamond in the Village” project and won the contest. The reward earned by Ban Phasuk qualified it to be a model for village development in promoting local tourism.

In this respect, the 7th August Volunteer Club for Development became a tool that villagers used to connect with state agencies, enabling the village to gain more development funding from the state. For instance, the state chose Ban Phasuk to display its village history in an exhibition. At this event, local products such as silk, foods, and clothing displaying Communist symbols were promoted and offered for sale.

(3) Through negotiation with local authorities, Ban Phasuk was proposed to be a historical village and was eventually accepted as such. Becoming a historical village significantly changed the perception of Ban Phasuk from being a Communist village into one where people dedicated their lives to fighting for society. The history that was encompassed in this project was starkly different from the history composed by the state. While the formal written history text is not yet established, the village itself tells its history. During ceremonies, for instance, people come to attend events and villagers narrate their stories to the audience. The history of the village is a living history; the people who experienced the fight in the jungle are still alive and can tell their stories. Stories that have meaning for the villagers of Ban Phasuk inserted in their narratives will be increasingly documented.

In addition, Ban Phasuk history was incorporated into local school curricula, under the subject of local history. Previously, the history syllabus for local schools was decided by the Ministry of Education, so the content was dominated by the history of the ruling class. During the past two decades, however, the Ministry of Education has allowed and instructed local schools to add local history into their curricula, after the political conflict between the state and CPT ended. In the case of Ban Phasuk, a teacher at a local school along with high school pupils conducted research on the history of the village. The villagers enthusiastically cooperated and supported the project. This project is, in effect, knowledge produced by Ban Phasuk villagers who played their part, and the knowledge is being spread through local education. This knowledge will become an important space underpinning the negotiations of the villagers.

Conclusion

The Thai state has been continually creating space and inserting its control over the populations within the space created. After the conflict between the state and the CPT ended in the mid-1980s, the space that the state created was concerned mainly with political space, and control over rural populations was exerted through rural development projects. In the case of Ban Phasuk, the villagers resisted and negotiated over a period of time. During the conflict a number of villagers fled to the jungle, escaping the state space to live and work in “liberated space.” After the end of the conflict, they returned to the village and continued their lives within the state political space. However, they did not simply surrender and submit themselves to the state power.

The discussion above shows that in the new context, villagers used their history of being involved with the CPT and the networks they had to negotiate their relationships with the state. The analysis above is consonant with the concept of space proposed by Bourdieu (1989). Under the state of political space, people engage in the field of forces, some created by the villagers. They constantly insert their own agendas and their own interests in these fields, which enables them to act meaningfully.

Accepted: March 30, 2017

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the Research Group on Wellbeing and Sustainable Development, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Khon Kaen University, for its support of this research. The author is grateful also for the valuable comments of both referees.

References

Baird, Ian G. 2013. Millenarian Movements in Southern Laos and Northeastern Siam (Thailand) at the Turn of the Twentieth Century: Reconsidering the Involvement of the Champassak Royal House. South East Asia Research 21(2): 257–279.

Bello, Walden; Cunningham, Shea; and Li Kheng Poh. 1998. A Siamese Tragedy: Development and Disintegration in Modern Thailand. London: Zed Books.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1991. Language and Symbolic Power, edited by John B. Thompson. Translated by Gino Raymond and Matthew Adamson. Cambridge: Polity Press.

―. 1989. Social Space and Symbolic Power. Sociological Theory 7(1): 14–25.

Bourdieu, Pierre; and Wacquant, Loïc. 1992. An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Chao Pongpichit เชาว์ พงษ์พิชิต. 2010. Luk cin rak chart ลูกจีนรักชาติ [Chinese Creoles love the nation]. Bangkok: Matichon.

Chatthip Nartsupa ฉัตรทิพย์ นาถสุภา. 2010. Karn pen samaimai kap neaw khit chumchon การเป็น สมัยใหม่กับแนวคิดชุมชน [Modernity and the theory of the community]. Bangkok: Sangsan.

Harvey, David. 2001. Spaces of Capital: Towards a Critical Geography. New York: Routledge.

Hind, Robert J. 1984. The Internal Colonial Concept. Comparative Studies in Society and History 26(3): 543–568.

Holloway, Immy. 1997. Basic Concepts for Qualitative Research. London: Blackwell Science.

Lowe, Peter. 2009. Contending with Nationalism and Communism: British Policy towards Southeast Asia, 1945–65. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Maniemai Thongyou. 2014. Rubber Cash Crop and Changes in Livelihoods Strategies in a Village in Northeastern Thailand. Asian Social Sciences 10(3): 239–251.

Murashima, Eiji มูราชิมา เออิจิ. 2012. Kamneut Phak Kommunist Sayam กำเนิดพรรคคอมมิวนิสต์สยาม (พ.ศ.2473–2479) [The establishment of the Communist Party of Thailand (1930–36)]. Translated by Kosit Thiptiampong โฆษิต ทิพย์เทียมพงษ์. Bangkok: Matichon.

Ninlawadee Promphakping นิลวดี พรหมพักพิง; Maniemai Thongyou มณีมัย ทองอยู่; and Viyouth Chamruspanth วิยุทธ์ จำรัสพันธุ์. 2014. Karn chuangching phuenthi tang karnmueang rawang rat lae thongthin koranee sueksa muban phu ruam pattana chart Thai การช่วงชิงพื้นที่ทางการเมืองระหว่างรัฐและท้องถิ่นกรณีศึกษาหมู่บ้านผู้ร่วมพัฒนาชาติไทยในภาคอีสาน [The political contestation between the state and the local: A study of a Thai Nation Development Cooperators’ village in Northeast Thailand]. Journal of Mekong Societies 10(2): 131–158.

Pasuk Phongpaichit; and Baker, Chris. 1997. Thailand: Economy and Politics. New York: Oxford University Press.

Por Mueangchompoo พ. เมืองชมพู. 1989. Su samorapum Phuparn สู่สมรภูมิภูพาน [To the battlefield of Phupan]. Bangkok: Matichon.

Putnam, Robert D. 1993. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Saisakul Dechaboot สายสกุล เดชาบุตร. 2012. Kabot Phrai rue Phi Bun: Phrawatsart karn tor shu kong rassadorn kub amnat rat neua paendin Sayam กบฏไพร่ หรือ ผีบุญ: ประวัติศาสตร์การต่อสู้ของราษฎรกับอำนาจรัฐเหนือแผ่นดินสยาม [Holy Men’s Rebellion: History of conflict between people and the state on the land of Siam]. Bangkok: Gypsy Group.

Somsak Jeamteerasakul สมศักดิ์ เจียมธีรสกุล. 2009. “Paet singha song pan ha roi paet” Wan Siang Puen Taek Ton Song “8 สิงหา 2508” (8-8-08) “วันเสียงปืนแตก” (ตอน 2) [“August 8, 1965” (8-8-08), the Gunfire Day (Part 2)]. http://www.prachatai.com/journal/2009/08/25401, accessed August 8, 2012.

Suthachai Yimprasert สุธาชัย ยิ้มประเสริฐ. 2010. “Phaen ching chart Thai” wa duey rat lae karn tor tan rat samai chompol Por Pibun Songkram ‘แผนชิงชาติไทย’ ว่าด้วยรัฐ และการต่อต้านรัฐสมัยจอมพล ป. พิบูลสงคราม [“The contest of Thai nation,” the state and resistance of the General Piboonsongkram government]. 3rd ed. Bangkok: P. Press.

Suwit Theerasasawat สุวิทย์ ธีรศาศวัต. 2006. Pravatsart Isan song sam song song thueng song si paet paet ประวัติศาสตร์อีสาน 2322–2488 [Isan history year 2322–2488]. Research report, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Khon Kaen University.

―. 2002. Settakit chumchon mu ban Isan: Prawatsart settakit Isan lang songkhram lok khrang thi song thueng pacchuban เศรษฐกิจชุมชนหมู่บ้านอีสาน: ประวัติศาสตร์เศรษฐกิจอีสานหลังสงครามโลกครั้งที่สองถึงปัจจุบัน (2488–2544) [A report on the economy of Isan community: The history of the Isan economy from World War II to the present (2488–2544)]. Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Khon Kaen University.

Tamthai Dilogratana ตามไท ดิลกวิทยรัตน์. 2003. Phaplak khong kommunist nai karn mueang Thai ภาพลักษณ์ของคอมมิวนิสต์ในการเมืองไทย [Image of Communism in Thai politics]. Rattasartsarn รัฐศาสตร์สาร [Journal of political science] 2(24): 148–205.

Ted Bunnag เตช บุนนาค. 2008. Kabot ro so nueng song nueng ขบถ ร.ศ.121 [Rebels in Bangkok era 121]. 4th ed. Bangkok: Foundation for the Promotion of Social Sciences and Humanities Textbooks.

Thawin Thongsawangrat ถวิล ทองสว่างรัตน์. 1897. Prawatsart Phuthai lae chao Phuthai mueang Renu Nakhon ประวัติศาสตร์ผู้ไทและชาวผู้ไทเมืองเรณูนคร [Phutai history and Phutai Renu Nakhon District]. Bangkok: Sri Anan.

Thikarn Srinara ธิกานต์ ศรีนารา. 2010. Lang hok tula wah duay khwam khatyaeng thang khwam khit rawang khabuankarn naksueksa kap Phak kommunist Haeng Prathet Thai หลัง 6 ตุลา:ว่าด้วยความขัดแย้งทางความคิดระหว่างขบวนการนักศึกษากับพรรคคอมมิวนิสต์แห่งประเทศไทย [After October 6, ideological conflict between students and the Communist Party of Thailand]. 2nd ed. Bangkok: P. Press.

Thongchai Winichakul. 2000. The Others Within: Travel and Ethno-Spatial Differentiation of Siamese Subjects 1885–1910. In Civility and Savagery: Social Identity in Tai States, edited by Andrew Turton, pp. 28–62. London: Curzon Press.

―. 1994. Siam Mapped: A History of the Geo-body of a Nation. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Wanchai Tantiwittayapitak วันชัย ตันติวิทยาพิทักษ์; and Thanapon Iewsakul ธนาพล อิ๋วสกุล. 2004. Thong Jaemsri: Lekathikarn Phak Kommunist Haeng phrathet Thai ธง แจ่มศรี: เลขาธิการพรรคคอมมิวนิสต์แห่งประเทศไทย [Thong Jeamsri: Secretary of Communist Party of Thailand]. Sarakadee สารคดี 20(232): 70–88.

Wyatt, David K. 1982. Thailand: A Short History. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Yod Santasombat ยศ สันตสมบัติ. 2008. Amnart phuenthi lae attalak thang charttiphan: Karn mueang wattanatam khong ratchat nai sangkhom Thai อำนาจ พื้นที่ และอัตลักษณ์ทาง ชาติพันธุ์: การเมืองวัฒนธรรมของรัฐชาติในสังคมไทย [Power space and ethnic identity: Cultural politics of nation-state in Thai society]. Bangkok: Center of Sirindhorn Anthropology.

1) As for Siam itself, it had to give up land on the right bank of the Mekong River, on the opposite side of Luang Prabang and Champasak in Laos, as well as the Khmer provinces of Siem Reap, Sisophon, and Battambang to France. It also had to transfer its right to govern the Malay provinces of Saiburi, Kelantan, Terengganu, and Perlis as well as land in Burma, i.e., Mergui, Tavoy, and Shan State, to Britain.

2) Capitation was a tax that was collected from citizens who resided on the land at the rate of 4 baht per person. In the past, these citizens were called phrai (subjects ไพร่). They were able-bodied men or persons of working age, i.e., 20–50 years old. Those who could not pay the tax had to engage in labor for the Public Works Ministry, which was responsible for the kingdom’s infrastructure development such as road construction and canals as well as the State Post and Telegraph and the State Railway.

3) Renu Nakhon was established in 1841, during the reign of King Rama III (1824–51). The governor form of administration was used. The positions consisted of vice-governor (upahat อุปฮาต), dynasty (ratchawong ราชวงศ์), and royal prince (ratchabut ราชบุตร). The governor system ended in 1903, at the time of King Rama V and Phra Kaeo Komon (พระแก้วโกมล) (Men Kophonrat เหม็น โกพลรัตน์), who was the fifth and last governor of Renu Nakhon (see details in Thawin Thongsawangrat ถวิล ทองสว่างรัตน์ [1897]).