Beyond Measuring the Voice of the People: The Evolving Role of Political Polling in Indonesia’s Local Leader Elections

Agus Trihartono*

* Graduate School of International Relations, Ritsumeikan University, 56-1 Toji-in Kitamachi, Kita-ku, Kyoto 603-8577, Japan

e-mail: atrihartono[at]gmail.com

DOI: doi.org/10.20495/seas.3.1_151__8211_

Since 2005, political polling and the application of polls-based candidacy have been enormously influential and, in fact, have become vital for local leader elections (Pilkada), particularly in Indonesia’s districts and municipalities. The Golkar Party’s declaration that it was moving to polls-based candidacy created a domino effect, inducing other major political parties—such as the National Mandate Party (Partai Amanat Nasional, PAN), the Democratic Party (Partai Demokrat, PD), and the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (Partai Demokrasi Indonesia Perjuangan, PDIP)—to follow Golkar’s approach to contesting local constituencies. As polling becomes a new device for reforming the political recruitment process, political polling exercises have also unintendedly transformed into a means for waging a power struggle. Political actors have exploited polling as a tool for gaining a political vehicle, as a map for soliciting bribes, as a map for guiding the mobilization of votes, and as a means for inviting an indirect bandwagon effect. In short, political polling has moved beyond acting as a tracker of voters’ preferences to become a popular political device.

Keywords: political polling, local leader elections, democratization, Indonesia

Introduction

Following the fall of Suharto in 1998, Indonesia embarked on an intensive project of local democratization. Under the banner of applying Law Number 32 of 2004 regarding “Regional Government,” local leaders—such as governors, district leaders (bupati), and mayors—were to be directly elected by the people for the first time in Indonesian political history. In particular, from June 2005 onward, Indonesia began experiencing two enormous waves of direct local leader elections (Pemilu Kepala Daerah, Pemilukada or Pilkada; hereafter Pilkada). The first episode was from mid-2005 to the beginning of 2009, and the second is still ongoing, beginning in late 2009 and extending to the beginning of 2014. From 2005 to 2008, Indonesia held no fewer than 500 Pilkada spanning all regions (Centre for Electoral Reform 2008). According to the Badan Pengawas Pemilu or Bawaslu (Election Monitoring Body), there were also approximately 244 Pilkada during the year 2010 (Indonesia, Badan Pengawas Pemilu [Bawaslu] 2011) and 116 Pilkada in 2011. In addition, from 2005 to 2010 more than 2,200 pairs of candidates ran for gubernatorial, bupati, and mayoral offices; there were also 333 pairs running for such offices in 2011 alone (ibid.). The implementation of Pilkada has resulted in the development of a remarkably vigorous local democracy, as indicated by the massive number of candidates and the frequency of elections. Judging from the large number of elections and candidates involved, Indonesia is unquestionably the country of elections.

One of the most important phenomena marking Pilkada has been the involvement of polling and other pollsters’ activities in these contests. The discussion of electoral politics in Indonesia has suddenly been filled with insider accounts of the results of polling activities,1) as polling has not only become a ubiquitous new fashion in local politics but has also noticeably colored the dynamics of local leader elections. It seems likely that political polling has become an integral part of almost every local leader election in Indonesia.

Previous seminal works addressing the topic of political polling in Indonesia have placed more emphasis on the mushrooming of polling at the national level (Mietzner 2009), the increasing role of pollsters as professionals (Mohammad Qodari 2010) or so-called polls-based political consultants,2) and the growing employment of political marketing that is the result of the presence of pollsters in the political arena (Ufen 2010). Those studies emphasize the impact of the presence of pollsters in the two national elections in 2004 and 2009. Although the involvement of polling and pollsters at the politically vibrant national level is headline-grabbing, previous works neglect the utilization of polling by political parties in attempting to identify electable candidates, as well as the fact that polling is used as a political weapon rather than a barometer of public sentiment.

Admittedly, the utilization and exploitation of polling in political history is not the newest phenomenon. In his classic seminal work more than 50 years ago, Louis Harris (1963), one of the key founders of polling, assertively foresaw that polls were “an important part of the arsenal of weapons used in modern American political campaigns.” R. A. Camp (1996) enthusiastically describes polling as a device that political leaders take advantage of for their own political interest, specifically to indicate successful platforms and increase their ability to defeat their opponents as well as to improve their political image. In a similar vein, Dennis Johnson (2001; 2009) and Christopher Wlezien and Robert Erikson (2003) view polling as being exploited by politicians to enhance their image during the campaign period. In short, it is not uncommon to take advantage of polling in political games.

However, in the context of Indonesia, one of the largest democratic countries in the world, a study discussing the development of public opinion polling and how it has been used (and exploited) seems exceptionally limited. While the importance of political polling in the consolidation of democracy in Indonesia has increased, the country has been neglected in discussions on the development of polling in both developed and developing democracies (Geer 2004; Carballo and Hjelmar 2008; Johnson 2009). Above all, in the context of Indonesia’s local politics, it seems no research so far has focused on issues such as the development, utilization, and exploitation of public opinion polling. Against this background, this study attempts to fill in the gap by demonstrating the extent of utilization and exploitation of polls in Indonesian politics, specifically in the era of Pilkada starting from 2005.

This paper suggests that political polling in local Indonesian politics has moved beyond its long-established use as an instrument to capture the so-called voice of the people. Even though from the beginning the development of polling in Indonesia was designed to consolidate democracy and to promote the previously neglected grassroots voice, this paper provides evidence that there has been an unintended transformation in the way polling is utilized. Local political players have exploited polling as a political instrument in their struggle for power. Polling is the most recent method by which political parties improve their political recruitment process at the local level. Polling also aids in campaign strategy, key decision making, developing winning strategies, and building up campaign communications. This study attempts to show that the use of polling is increasing, and that polling is gradually gaining acceptance as a sophisticated tool to obtain a political vehicle, a bribery map, and a voter mobilization map, and as a means for inviting an indirect bandwagon effect. While providing some cases from Pilkada in districts and municipalities of North Sumatra, East Java, and South Sulawesi in 2009 through 2011 will not permit generalization, this analysis sheds new light on the other side of political polling in the current dynamics of local Indonesian politics.

To explore the aforesaid argument, the paper is divided into three sections. The first briefly discusses local leader elections, political parties, and the significance of political polling in the age of Pilkada. The second section answers the question of why pollsters have participated in the fiesta of Indonesian local leader elections since 2005. The third elaborates on the use of political polling in Pilkada, specifically spotlighting how polling has become both a new candidacy mechanism and a new political weapon. Throughout this study, I attempt to demonstrate that the emerging role of political polling in the dynamics of contemporary Indonesian local politics has gone far beyond merely uncovering people’s preferences.

Pilkada, Political Parties, and Voters

The implementation of Pilkada was promoted as a means of deepening democratization and helping to consolidate democratic practices at the local level. Pilkada has provided local communities with important opportunities, as the emergence of grassroots national leaders has been followed by the appearance of local leaders who possess popular support (Leigh 2005). Furthermore, Pilkada has provided a space for the wider participation of society in the democratic process and a correction to the previous indirect system in that it supplies regional leaders of greater quality and accountability (Djohermansyah Djohan 2004). Finally, Pilkada also offers opportunities for the grassroots to actualize their political rights without worrying that they will be reduced by the interests of political elites.

There are several essential aspects of Pilkada that need to be highlighted. First, although the position of political parties is essential in Pilkada, there is an argument that Pilkada has made political parties weak in some ways (Choi 2009). Political parties are the most prominent and vital institutions in the current practice of local democracy, as their basic role is to recruit and provide cadres to participate in elections and to nominate candidates for administration in a “gate keeping position” (Schiller 2009, 152). In the political recruitment process, political parties make the initial selection of candidates and provide alternatives for voters in elections. Understandably, political parties are vital in the nomination process because candidates can be nominated only by them.

Second, since 2007, democracy at the local level has been revived following a key review by the Constitutional Court (Mahkamah Konstitusi). This review was a legal consequence following the Constitutional Court ruling on July 23, 2007 that non-party candidates would be allowed to run in local elections subsequent to the post-conflict 2006 vote in Aceh Province that permitted local actors to run as independents. According to the review of Law Number 32 Year 2004, July 23, 2007, the court passed a petition regarding the process of non-party side nominations,3) known as the independent pathway (jalur independen). The review opened up the opportunity for candidates to run in elections without political party nomination.4) Considering that new development, therefore, at present Indonesia has two important and legitimate mediums through which political actors run for local elections, namely, the political party and the independent pathway.

Third, direct (local leader) elections have positioned voters as the premier judge in determining leaders. Voters have autonomy in electing a pair of local leaders independently. As we will discuss later, voters can even vote differently from their previous choice of party representatives in national and local legislatures. Consequently, responding to the “autonomy” of voters in electing candidates, the terms “popular,” “acceptable,” and “electable” are part of the vocabulary for candidates who struggle in contemporary local elections.

Finally, local elections are an indispensable arena for political parties to seize power. Following the implementation of decentralization at the local level, the authority given by the central government to local governments in managing financial and political resources has significantly increased. At the same time, lodging control of local government with local elites means the distance between those elites and their constituents has narrowed. Therefore, winning local elections is not understood simply as procuring control of local government but is also the means by which to be directly in touch with the acquisition and maintenance of political constituencies at the grassroots. In this sense, success in local elections is also about the survival and sustainability of political parties at the grassroots.

Accordingly, political parties have a strong rationale for extensive involvement in local elections. First, parties now recognize victory in local elections as an opportunity for their cadres to engage in the political learning process. For more than 32 years during the Suharto era, political parties were marginalized and impotent. According to Akbar Tanjung, a senior politician of the Golkar Party, during the Suharto era parties served as “cheerleaders” and as participants in political displays, as they did not have an arena in which to perform their traditional roles and functions regarding political recruitment and institutionalization.5) Second, political parties now consider success in local elections as an entry point for exercising executive power in each region. This realization is particularly important because executive positions are seen as part of a vital machine for the implementation of policies and political visions, as well as for providing access to financial and political resources. Finally, for young and minor political parties, which still have limited potential cadres to promote in the contestations, local leader elections are an arena for attracting potential and popular candidates from non internal party’s cadres to run under their flag.

In addition, the dynamics of local leader elections require political actors to understand changes in voting behavior. While we cannot generalize that all things are equal in all Pilkada, as in some cases voting behavior has special characteristics—particularly in areas of conflict such as Aceh, Poso, and Papua—significant changes in voting behavior are evident in local leader elections. Departing from a class perspective, some scholars, for instance, started to question the weight of the political sects (politik aliran) approach (Hadiz 2004a; 2004b). Utilizing regression analysis, the works of politik aliran, religious affinity, regions, ethnicity, and social class of voting behavior in the post-Suharto democracy have been also questioned (Saiful Mujani and Liddle 2004; 2009; Saiful Mujani et al. 2012). Furthermore, political behavior is obviously different now compared with the 1950s (Saiful Mujani 2004). Regarding the significant changes, thus, the strategy for facing current Pilkada cannot be based merely on conventional ideas regarding the importance of political sects, political machines, and political patrimonialism.

Contemporary Pilkada are not only important for local people to have the opportunity to directly select their leaders; Pilkada necessitate political adjustments in local actors’ strategies to account for the large shift in local political dynamics. The new political dynamic has also provided an entry point for pollsters and political polling to play a role in an evolving set of political games, as pollsters are seen as one of the most capable actors in detecting and measuring new trends in voting behavior.

Therefore, there is a symbiotic mutualism between local players and pollsters that represents the new dynamics in local leader elections. According to Heri Akhmadi6) and Akhmad Mubarok,7) senior politicians in the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (Partai Demokrasi Indonesia Perjuangan, PDIP) and the Democratic Party (Partai Demokrat, PD), political parties and pollsters are pillars that support each other as couples, striving to fulfill each other’s needs. Moreover, with the new circumstances in local contests, pollsters have been the most reliable means to detect fundamental changes in voting behavior. In short, pollsters fill the hole left by this new reality and play a notably significant role in local contests.

Polling in Local Elections

As previously mentioned, the increased involvement of political polling in local leader elections coincided with the first cycle of Pilkada that began in 2005. Before 2005, there were few pollsters in Indonesia. For instance, in the 1999 general elections there were five pollsters conducting polls at the national level: the Resource Productivity Center; the International Foundation for Election Systems; the Jakarta-based Institute for Social and Economic Research, Education, and Information (Lembaga Penelitian, Pendidikan dan Penerangan Ekonomi dan Sosial, LP3ES); the Kompas newspaper; and the Political Laboratory of the University of Indonesia (Komite Pemberdayaan Politik-Lab Politik UI) (Lembaga Survei Indonesia 2004, 30–31). In addition, before the 2004 general elections there were some pollsters involved in national pre-election polling, such as the Center for Islamic Studies and Society (Pusat Pengkajian Islam dan Masyarakat), the Indonesian Survey Institute (Lembaga Survei Indonesia, LSI), Soegeng Sarjadi Syndicate (SSS), and Danareksa Research Institute. There were also media polls, such as the R&D of Kompas Daily (Litbang Kompas), polls by SMS (short message system) of the SCTV (Surya Citra Televisi), and tele-polling of MARS Indonesia (ibid., 47–54). Although the number of pollsters and their activities were obvious, as Kuskridho Ambardi, executive director of the Jakarta-based LSI, illustrated, polls in this period were not part of widely accepted political, social, and economic discussions as many party men were still unaware and rejected the idea that polls should be included in a shared democratic vocabulary. At the time, political actors and mass media exposed doubts regarding the value and political influence of polls.8)

Following the first wave of local leader elections starting in 2005, the number of pollsters mushroomed, including those participating in Pilkada, such as media pollsters (Republika, Bisnis Indonesia, etc.), political party pollsters (i.e. the PDIP’s Rekode), and national and local pollsters.9) Moreover, media coverage of polling was massive, and the publication of polling results was also intensive, which led to a “survey fever” in Indonesian politics nationally and locally.

The earliest involvement of polling activities in local politics was in the first local leader elections in Kutai Kartanegara, held on June 1, 2005. The duo of Syaukani Hasan Rais and Samsuri Aspar took the assistance of the Jakarta-based Center for Strategic and International Studies.10) Further, the election for the governor of Banten Province in November 2006 marked the beginning of the “war” among national pollsters in Pilkada, as many national pollsters became involved in the contest.11) The vigorous participation of pollsters in Pilkada has come to the fore ever since the Golkar Party officially invited pollsters to become a central instrument in its polls-based candidacy, which began in December 2005, under the banner of the party’s Operational Guidelines (Juklak, Petunjuk Pelaksanaan) Number 2 Year 2005.12) From those moments, polling has been omnipresent in Pilkada.

The application of polling in direct local leader elections has raised the expectation that polling itself strengthens and supports the development of local democracy. In other words, political polling is thought to encourage political actors to hear the previously neglected voices of local communities, and to create visions and frameworks that reflect people’s opinions. The utilization of polling, therefore, has created great optimism that the government and political actors will be encouraged to be more responsive to popular perspectives. In particular, it is thought that polling promotes the emergence of local leaders in closer touch with community preferences.13) Consequently, it is believed that those policies and platforms that are contrary to popular aspirations will be abandoned.

In practice, political parties and candidates utilize polling to improve their adaptation to a new local political environment by engaging in such activities as the following: (1) mapping the most favorable program to attract voters’ support; (2) evaluating the performance of the incumbent; (3) measuring the degree of popularity, acceptability, and electability of both political parties and potential candidates; (4) identifying party identification among voters and swing voters; (5) observing which media are most appropriate for socialization; (6) determining how candidates should socialize with voters; (7) scrutinizing the whom, the where, and the why of potential supporters and rivals; and finally (8) testing the waters and mapping strategies for minimizing possible losses.14) Last but not least, political parties and candidates view polling outcomes as the ultimate factor in deciding whether or not to continue running for election. By doing so, political actors can minimize their losses and failures.

With regard to Pilkada, there are four types of pollsters that have played a role in local contests. The first are national pollsters. Almost all national pollsters are key players in local leader elections. Prominent names, such as the LSI, the Indonesian Survey Circle (Lingkaran Survei Indonesia), Indo-Barometer, Cirrus Surveyor Indonesia, National Survey Institute (Lembaga Survei Nasional), and Indonesian Vote Network (Jaringan Suara Indonesia), have increased the vibrancy of local elections. The second type of pollsters are local pollsters that are part of national organizations. These institutions have an organizational relationship with the “parent” pollsters in their headquarters. Examples are the 34 local partner institutions of the Indonesian Survey Circle, which are also incorporated in the Indonesian Association for Public Opinion Research (Asosiasi Riset Opini Publik Indonesia, AROPI).15) The third type are local pollsters who initially operated as individuals working with national pollsters but later, having gained the skills and knowledge required for public opinion polling and political consultancy, decided to become independent and set up their own local polling organizations. Examples are the Makassar-based Adhyaksa Supporting House and the Makassar-based Celebes Research and Consulting. Adhyaksa Supporting House worked together with the Indonesian Survey Circle to assist the pair consisting of Syahrul Yasin Limpo and Agus Arifin Nu’mang in the 2007 South Sulawesi gubernatorial elections.16) Meanwhile, the head of Celebes Research and Consulting previously worked at the LSI. The last type of pollsters are “independent” local pollsters. These pollsters have from the beginning worked on their own: acquiring the necessary skills, understanding polling methods, and conducting surveys. They have developed and expanded a specific market segment. These pollsters have no relations with pollsters at either the organization or the network level. Examples include the Surabaya-based Research Center for Democracy and Human Rights (Pusat Studi Demokrasi dan Hak Azasi Manusia, Pusdeham); the Makassar-based Insert Institute, Yayasan Masagena, and Script Survey Indonesia; and the Medan-based Inter-Media Study.

Local Leader Elections: Pollsters’ New Realm

In general, pollsters have realized that local leader elections are attractive because they provide opportunities to bet on the new arena of political contests. Because local leader elections are numerous and spread out in various areas, the elections have provided new ground on which pollsters can survive, obtain significant financial benefits, and even attain a sphere of influence.

In comparison, national elections (both general and presidential), though noteworthy, attention-grabbing, and having significant financial impact, attract only the biggest and fittest pollsters. Therefore, there have been only a few outstanding pollsters who have become involved in and taken advantage of these two principal national events. National elections require more than just skills and wills; they require such technical factors as a significant survey network that permeates the country, a high degree of professionalism, and the capacity to cover the high cost of a national survey. These are among the factors behind the low participation rate of pollsters in national contests. In addition, the national election is a ruthless judge of pollsters’ credibility because the results, particularly pre-election polling and quick counts, are directly tested by the public, openly examined by the mass media, and critically discussed in academic circles. Simply put, polling outcomes are scrutinized and compared to the official vote count of the Election Commission (Komisi Pemilihan Umum, KPU). Consequently, the publication of polling results means laying a bet not only on the credibility but also on the sustainability of a pollster’s activity. The ability to accurately predict the outcome of an election is one of the pollster’s pillars of credibility. Although polling is not an instrument for predicting election results, if polling results are significantly different from the actual results of the election it spells disaster for the pollster’s credibility. A pollster named Information Research Institute (Lembaga Riset Informasi, LRI), also known as Johan Polls, was closed down after it failed to predict the outcome of the 2009 presidential election. The LRI released the results of surveys conducted in the 15 most populous provinces, involving 4,000 to 12,000 respondents per province. Based on the polling, LRI confidently predicted that the 2009 presidential election would go to the second round. In fact, in the presidential election held on July 8, 2009 the SBY-Budiono pair had a landslide victory in the first round (60 percent). This failure to predict an accurate result led the owner of the LRI to close the office for good.17) This tale will not soon be forgotten in the Indonesian pollster community’s collective history. Thus, in national elections, it seems that accuracy is the ultimate test that accounts for the rise and fall of pollsters.

Unlike the case of national pollsters, for local pollsters Pilkada represent the future of their existence. Local leader elections seem to provide opportunities for all kinds of pollsters: prominent national pollsters, national pollsters who do not participate in national elections, and even local pollsters with limited capacity all come to enjoy the “feast of local democracy.” In addition, local leader elections absorb many kinds of pollsters who wield, methodologically speaking, good, bad, and ugly techniques. Even the image and credibility of a pollster seems not to be critical in the context of local leader elections. A pollster that does not always succeed in local polling is still able to advertise in the national newspaper claiming to be the most successful pollster in the country, without any significant objection from the public. The public does not easily recall the failures of pollsters in local leader elections because, on average, there is a local leader election every two days.

Second, although polling in local leader elections is not profitable compared to polling in national elections, judging from their enormous number the former appear to provide enough financial resources for pollsters to survive and continue their operations. Not only have pollsters gained significant financial profit, but many rely solely on Pilkada for their wealth and fame. For some pollsters, local elections provide the only opportunity for financial benefit, as they cannot compete in national polling. Most important, the wave of local leader elections is attractive because it is truly a huge market. To make a simple calculation, in the first wave of Pilkada, for instance, in one round of local leader elections for governors, bupati, and mayors, there were approximately 510 elections with more than 1,500 pairs of candidates. Furthermore, the average number of pairs involved in elections has increased in the ongoing second cycle that lasts until 2014. According to Juklak 2/2009, for instance, the Golkar Party requires three surveys for every local election, which means the party conducts at least 1,530 political surveys. Moreover, the PD and the National Mandate Party (Partai Amanat Nasional, PAN) require at least one survey during the nomination process. Meanwhile, the PDIP is beginning to consistently utilize polling for candidates to support the party’s decision to nominate local leader candidates. If we include polling conducted individually by candidates and businessmen, the number is significantly larger. Moreover, the potential market is not exclusively for pre-election polls/surveys but also includes quick surveys, quick counts, quick real counts, exit polls, and political consultation.18) Most important, pollsters’ activities in local leader elections are quite simple and manageable, requiring no large surveyor networks and costs, and fitting within local areas, customs, and cultures. Finally, several cases demonstrate that successful pollsters that predict the winning local candidates gain not just money but also access to power and/or projects in the local area.19)

Another factor influencing pollsters that are intensively involved in local leader elections is that supportive funding from foreign donors has mostly ended. Previously, between the 1990s and 2005, certain pollsters received operational funding from external donors to support their daily activities under the banner of developing democracy in Indonesia; for example, the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) supported the LSI from 2003 to 2005.20) In 2004, almost all institutions, including the National Democratic Institute, International Republican Institute, and LP3ES, saw the end of financial support from foreign donors. This development required pollsters to search for alternative funding to run their programs. The wave of local leader elections since 2005 has provided a significant alternative funding opportunity for pollsters.

To conclude, the huge market, the simplicity of managing local polling, and the end of some foreign donors’ support in 2005, as well as the invitation from political parties to engage in political and strategic adaptation, as we will discuss next, has led national and local pollsters to engage in the dynamics of local leader elections.

Instrument of Local Political Games

This section highlights the importance of the ongoing use of polling with regard to local political games. Polling is increasingly being used by political parties and other local political players in Pilkada. Political parties have started to utilize polling in the process of identifying candidates. However, at the same time, local political players such as candidates and local elites have also started to take advantage of polling as a tool for obtaining a political vehicle, a bribery map, and a voter mobilization map, and as a means for inviting the indirect bandwagon effect.

A Tool of Political Parties: Evolving Polls-based Candidacy

Responding to the change from indirect to direct local leader elections in the Indonesian election system, political parties began to consider adjusting to polls-based candidacy for winning those elections or at least minimizing failure and defeat. Previously, the nomination process for local leader elections was based on both the iron law of oligarchy with regard to local elites and the influence of “money politics.” Under this situation, a candidate was in a better position if he or she was part of the local political elite or possessed capital by which to procure a political party as a kendaraan politik (literally, a “political vehicle”). Accordingly, to obtain a political vehicle, candidates paid party elites for approval, a phenomenon known as political dowry (mahar politik). The latter is an amount of money that stands as a symbol of agreement between the party elite and the candidate so that the party or parties nominate the political actor as the only candidate to run in the election. In some cases, the giving of political dowry also means that candidates pay all the costs of both the election nomination process and the campaign. During this time, “money talks” politics, mixed with the influence of the elites’ and local bosses’ weight and approval, are not only the first element in the nomination process but to some extent are really the only game in town.

The period of Pilkada, which started in June 2005, has changed the local political landscape by emphasizing that politics is no longer centered merely on local elites. Instead, local direct elections provide greater room for the will of the people to be the new political epicenter. Unfortunately, most political parties were not ready to adjust to this new environment. Many parties, including major ones such as Golkar, held old views in facing the new situation: they assumed the effective working of the political machine and patrimonialism. Parties in general did not have any idea how to respond to the modern political challenges until they suffered defeats in the early stages of new direct local leader elections. For instance, the champion of the 2004 general elections, the Golkar Party, was beaten in almost 70 percent of local leader elections up until December 2005.21)

Responding to those embarrassing defeats in the early stages of the first cycle of Pilkada, the Golkar Party revised its implementation guidelines (Juklak) for short-listed candidates to take advantage of polling techniques. Golkar declared in December 2005 that it would rely on polling as the primary method for identifying candidates in local leader elections (Juklak 5/2005) and invited pollsters to assist the party in determining and selecting candidates. Golkar determined that it would examine the public acceptability of a candidate through periodic polling because it wanted to nominate the most popular and least disliked candidates. In Golkar’s understanding, the use of polling in the determination of prospective candidates would seem to increase the party’s success rate in local leader elections.

The Golkar way of polls-based candidacy created a domino effect, spurring other political parties to also utilize polling as a new device in reforming the selection process and improving strategies for winning local leader elections. The PAN in 2006 decided, based on the national meeting held that year, to utilize polling as part of its process for identifying candidates. The PD in 2007 also turned to a pollster for help with its candidate identification and nomination processes. Finally, although it had unofficially and partially utilized polling since 2006, the PDIP officially decided in 2010 to take advantage of political polling as part of the party’s decision-making process.22) Among the main reasons why parties utilize polling is the need to modernize the party, minimize money politics in local candidate selection, and reduce potential conflicts among political actors. Another reason is that political parties need to adapt to new situations in order to maintain their relevance in society.

1. Golkar Party

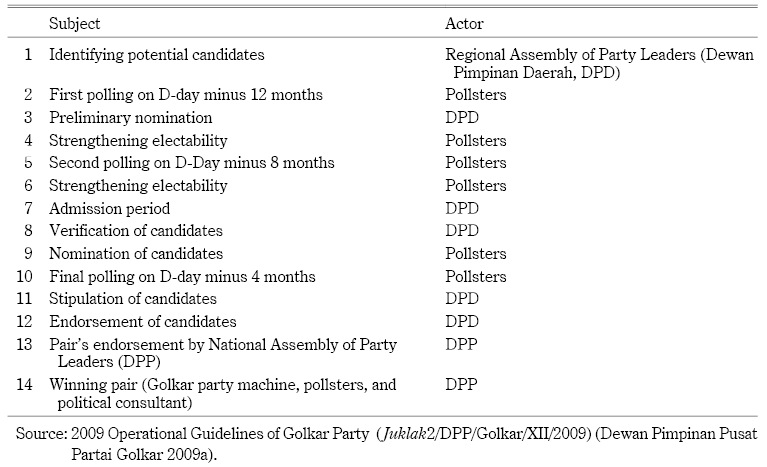

Golkar is one of the parties that have consistently applied polling in the recruitment of prospective regional leaders. The Golkar Party issued its Operational Guidelines Number 5 in 2005 and strengthened those guidelines in the most current version (Juklak Number 2 in 2009) (Dewan Pimpinan Pusat Partai Golkar 2009a). The new guidelines require that the National Assembly of Party Leaders (Dewan Pimpinan Pusat, DPP) select the most electable candidate based on polling outcome. In particular, the new guidelines require polling to be undertaken at least three times during the candidacy process. The guidelines also clearly divide the work between the party and the pollsters. Pollsters have been given a strong and independent role in measuring the popularity, acceptability, and electability of candidates, all important ingredients in the nomination process.

In Table 1, it can be seen that the party incorporates polling throughout the candidate nomination process. Among the 14 steps making up the candidacy process, almost half are handled by professional pollsters.

Since the Golkar Party decided to utilize polling, the party has hired at least three independent pollsters and polls-based political consultants. All polling activities were undertaken by the Indonesian Survey Circle in 2005, the LSI in 2006, and Indo-Barometer in 2008. Political consulting services were provided by the Indonesian Survey Circle and Indo-Barometer. Meanwhile, from the beginning, the LSI consistently worked only on polling.

The new system has, on the one hand, led to a significant degree of displeasure in the Golkar’s local cadres, as it is seen as a re-centralization of the decision making of nominating candidates. Seen in this way, the involvement of pollsters has strengthened the domination of the DPP over the DPD in the candidacy process. The new system indicates a centralization of political recruitment. On the other hand, the new guidelines have had a somewhat significant impact on the party’s success rate in local leader elections. From January 2006, soon after the Golkar guidelines were implemented, until the end of the year Golkar won more than 64 percent of the 75 elections it participated in. After utilizing polling, the party’s achievements in gubernatorial elections were better than they had been in 2005. Golkar won 46.8 percent of elections at all levels of the first wave of Pilkada.23) Up until December 2008 Golkar had won 42.42 percent of all elections held at the district and municipal levels and 25 percent of all elections held at the provincial level. It is also interesting to note that 72 percent of Golkar’s achievements after 2006 were made through coalitions with other parties. This provides evidence that polling led Golkar to improve its winning strategy by increasing cooperation with other parties (coalition) to significantly achieve victory in the first cycle of Pilkada.

2. National Mandate Party

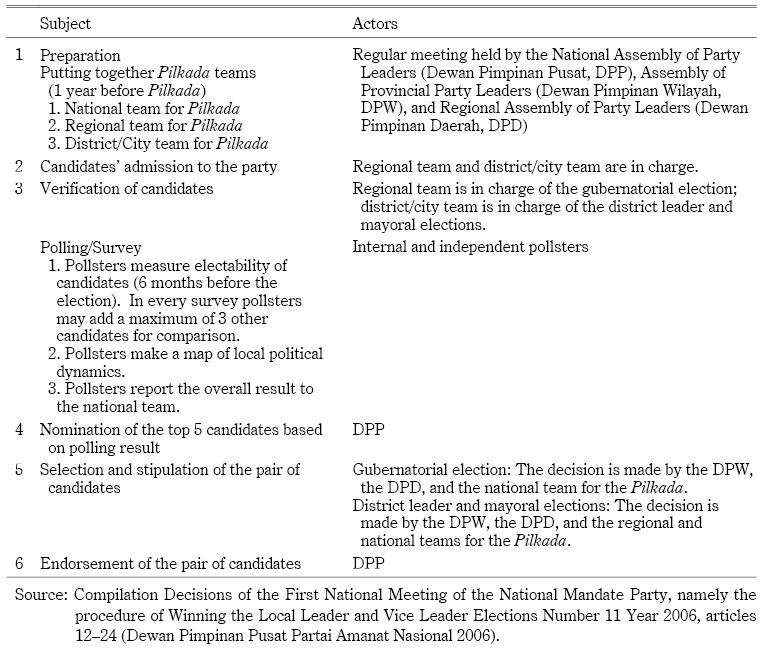

Since 2006, the National Mandate Party (PAN) has applied a new approach to invite prospective candidates. Unlike the previous approach, where the party selected only the internal party’s cadres, following its 2006 national meeting the PAN opened the possibility for outsiders (non-internal party cadres) to apply for nomination in local leader elections under the flag of the party. This decision challenged previous mechanisms, which emphasized that only the original candidates were to be supported by the party, with no room for outsiders. Accordingly, the party incorporated elements of political polling as a key part of the candidacy process. The new approach in the candidacy process is as outlined in Table 2.

Table 2 shows that polling is an essential factor in deciding which candidates the party will support. To gain the optimum outcome, the party also requires two other qualities of its candidates—namely, integrity and capacity—as part of its final decision. Yet, “electability” is most important among the candidacy criteria.24) Regarding this new approach, Viva Yoga Muladi, the former deputy secretary-general of the PAN, highlighted that the new system was designed mainly to foster party modernization and to make the party more rational and inclusive.25) Most important, implementing polls-based candidacy was intended to prevent the political tendency of using the party as merely a “rental” political vehicle in elections. Moreover, the inclusion of polling in the nomination phase has allowed anybody, whether a party’s cadre or an outsider, to gain the support of the party based on his or her potential to win the election.

The role of polling was strengthened after Drajat Wibowo, the academic wing of the party, and Aria Bima Sugiarto, the former executive director of the Jakarta-based pollster Charta-Politica, achieved the top-ranking positions of the DPP in the present era of the Hatta Rajasa administration. These two men are the figures behind the emerging role of polling in the party. To support the thorough modernization of PAN, party elites are in the process of creating internal pollsters as a strategic instrument to be wielded in both local and general elections.

Regarding the employment of polling in the party’s candidacy process, one of the main rationales was that until December 2005 the party was a notable loser in elections. The party failed to succeed, or to be part of the winning coalition, in 86 percent of elections up to 2005. After the implementation of the new procedure of Winning the Local Leader and Vice Leader Elections, PAN started to employ polling to help its candidacy. As a result, the party experienced a dramatic improvement in performance: it won individually, or as part of the winning coalition, in 32 percent of elections in 2006, 22 percent in 2007, and 23 percent in 2008.26) The contribution of the new procedure has been that polling outcomes, for instance, have guided the party to take the principal position in 64 winning coalitions in 273 elections from 2006 to 2008. In other words, the surveys have assisted the party in seeking opportunities and developing coalitions with other parties that carry electable candidates.

3. Democratic Party

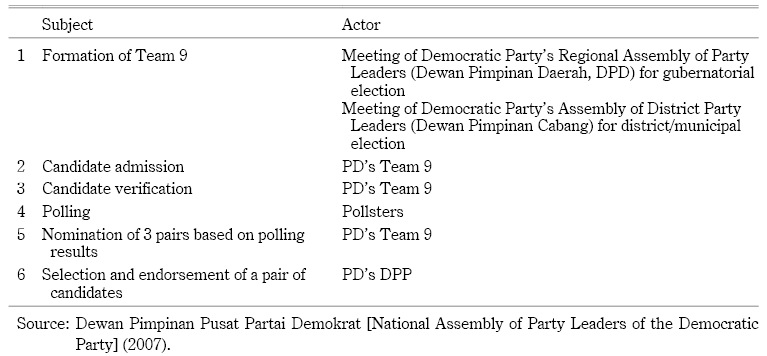

Two years after the wave of local leader elections, the Democratic Party (Partai Demokrat, PD) issued an organization rule (Peraturan Organisasi) on February 9, 2007, that specifically regulated the implementation of the mechanism for choosing candidates for local leader elections. Under the new rule, the party decided to follow the path of polls-based candidacy prior to elections. Incorporating polling in a party’s decision-making process is seen as a realistic policy for the PD. As a relative newcomer compared to other major political parties, the PD has only a few grassroots support groups and does not possess many reliable and capable original cadres to boost its performance. Therefore, polling has become not only a device to ensure that the party supports the candidate with the greatest chance of winning, but also an instrument to seek potential political actors to be included in the party as part of local and national party development. Polling results are also designed to help the party make political alliances and coalitions at the local level with the most appropriate party, even with a party that it generally opposes.27) All these measures ensure that the party plays a part in running the local government.28)

The PD decided to adopt the new mechanism of polling under the rationale of improving political performance.29) The old system of selecting candidates for local leader elections was allegedly vulnerable to the abusive politics of “buying a boat” (literally membeli perahu, or “buying a political vehicle”); many such cases were internally detected.30) Therefore, under the new regulation number 02/2007, the function of Team 9 (three people from the DPP, three from the DPD, and three from the DPC to verify which candidates will run for elections) has been improved by incorporating polling in the process. As seen in Table 3, independent polling has assisted Team 9 in identifying potential candidates. The results are submitted to the DPP to be examined and approved.

Until December 2005 the PD had won only one election—in Toraja District, South Sulawesi—and shared in 8.2 percent of all coalitions of ruling parties in 2005. However, after the party implemented the polling mechanism in March 2007, its share increased to 13.64 percent of the winning coalition in 2007 and 16.23 percent in 2008. The winning rate after the introduction of polling was almost double (15.6 percent) compared to the rate in the first year of Pilkada in 2005 (8.02 percent). Considering that the PD is a novice in local political games, this achievement cannot be overlooked. Moreover, the party has been the backbone of two governors in politically strategic areas, namely, East Java and the capital, Jakarta.31) In short, the achievement suggests that polling is an effective compass for a party facing new dynamics in local elections.

4. Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle

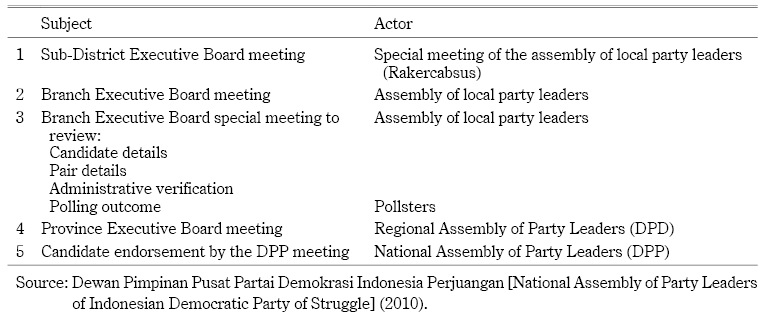

In May 2010 the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDIP) officially decided to include polling outcomes in the mechanism it used to select candidates, a decision that has provided new opportunities for electable candidates to gain approval whether or not they are proposed from the bottom. The PDIP is beginning to include the public’s voice in its centralized decision-making process,32) especially in nominations for local leader elections. Currently, the decision-making process of the PDIP for determining candidates to contest elections is centralized in the DPP. Although proposals of candidates could always come from below, from the Regional Assembly of Party Leaders (DPD), the final decision in determining candidates is taken at a meeting of the DPP. The DPP might accept the DPD’s proposal based on the decision taken at the special meeting of the assembly of local party leaders (Rapat Kerja Cabang Khusus, Rakercabsus). However, in practice, the DPP can decide to choose candidates different from those recommended by the Rakercabsus meeting. The DPP has the prerogative to make final decisions.

Regarding the use of polling, it should be noted that determining candidacy through polling mechanisms improves the system in that it reduces the contraction of the party due to losses in elections. Moreover, polling has brought a novel atmosphere into the party’s decision-making process because it has, to some extent, balanced the prerogative powers of the general chairperson, Megawati Sukarnoputri.33)

The party’s candidacy process is shown in Table 4.

For the PDIP, polling is as an essential factor in determining candidacy. Although the party’s final decisions on candidacy have relied totally on the prerogative of the DPP so far, polling has enabled the PDIP to have more choices in making rational and objective decisions. Polling is now inevitably utilized in the current political ambience, and the PDIP has taken this as a party adjustment to handle direct elections. Accordingly, Ganjar Pranowo, a senior PDIP politician, highlights the necessity of the party to consider polling: “The PDIP cannot ignore polling as it is inevitable in the current political dynamics. In particular, if the party is not ready to face the new realities and does not make adequate improvements and adjustments in political recruitment, polling firms can help it not only to be superior in political recruitment but also to pose a significant threat to its political rivals.”34)

The aforementioned suggests that the electoral system directly affects how political parties have begun to change the political epicenter from the elites to the public. The institutionalization of political polling seems to have improved the processes within parties, as the polling outcomes serve to guide the party’s decisions. However, the evidence also shows that the weight of public preference measured by polling is still used for the sake of winning elections, especially in the selection of prospective candidates and the creation of a winning strategy.

In a similar vein, the following discussion would seem to indicate how political actors also make use of polling in pragmatic ways. They are more interested in exploiting the polls as a political weapon for the sake of political victory rather than hearing the public’s sentiments.

Device for Obtaining a Political Vehicle

In the party-candidate relationship in Pilkada, it is clear that getting funds is a primary purpose behind the party’s choice of candidate (Buehler and Tan 2007, 41–69). Specifically, mahar politik works as the first element in the nomination process. However, direct elections have raised the hope that through Pilkada the conservative nomination process will fade away to some extent. As major parties began applying polling as part of their political recruitment process, the desire to push the candidate closer to public preferences was obvious. The closer the candidate was to the public’s approval, the greater the opportunity to be the winner—this is the new idiom in Indonesian local direct elections.

Polling results have become one of the candidate’s important instruments in dealing with political parties.35) Parties are more welcoming of candidates who are likely to win, and they are willing to offer them a political vehicle. This was illustrated in the 2010 mayoral election of Sibolga city, North Sumatra, where one of the candidates used polling results to solicit the support of political parties and was able to obtain a political vehicle; he received the majority support of 18 political parties without having to spend a significant sum of money.36) Sarfi Hutauruk was formerly a Golkar Party cadre and was involved in the party’s nomination process, a prerequisite for being a Golkar candidate for the mayoral election of Sibolga city. However, in the selection process Hutauruk was not nominated as a Golkar candidate as the party’s polling results indicated that his electability was lagging behind that of his rival, Afifi Lubis. Consequently, the party nominated Afifi Lubis as its candidate in the mayoral election.

His failure to garner the Golkar Party nomination led Hutauruk to consider the support of other parties. Before applying for other parties’ nominations, he hired a Medan-based local pollster for the purpose of testing the waters and measuring his electability. He found that in four months, based on two polls, his electability rate increased and approached Afifi Lubis’s. In the last poll, three months before the KPU registration deadline, the results showed that Hutauruk’s electability was higher than Afifi Lubis’s: 43 percent versus 41 percent. Armed with this electability rate, Hutauruk applied to several political parties in Sibolga to get a political vehicle; he did not apply to the Golkar Party, which was being used by Afifi Lubis. Utilizing the polling “card,” he convinced political party leaders to back him in his run for mayor. He not only got the support of 18 political parties but won the Pilkada held on May 12, 2010, in one round. Hutauruk gained 45 percent of the votes; Afifi Lubis won 40 percent.

Another substantial change following the implementation of polling has been the minimization of party pressure on candidates. It has traditionally been common for political parties to view candidates who are seeking a political vehicle as an ATM.37) However, when polls show that a certain candidate is a likely winner, that reduces the tendency of political parties to charge the candidate large sums of money—or to treat the candidate as an ATM—to get a political vehicle and political support. The cost becomes negotiable and flexible, depending on the candidate’s electability. Although the so-called mahar politik is not completely absent, as it still functions as a lubricant in the nomination process, the change is in the amount and the time frame. Thus, for candidates who have an excellent chance of winning as indicated by polling results, money is still a concern but is not first on the agenda.38) The amount of pressure political parties place on candidates decreases in line with the candidates’ possibility of winning. The local branch leader of a leading political party in a district of South Sulawesi Province noted that for the “convincing candidate,” the amount of mahar was no more than roughly the amount needed for campaign logistics.39) On the other hand, in the case of the PD, for example, more than 75 percent of the money paid by the approved candidate was returned to be used for campaign logistics.40) Furthermore, a candidate who is the most likely to win actually has better bargaining power in terms of choosing a political vehicle. Such a candidate has the opportunity to obtain the approval of a party without spending too much “lubricant.”41) A successful local leader in Sulawesi, for instance, suggested that the position of a prospective candidate was robust in dealing with local political parties.42) A prospective leader does not only avoid being exploited as an ATM; to some extent, he or she may have the opportunity to select a party or parties as a political vehicle, not vice versa.

Nonetheless, as factors such as popularity, acceptability, and electability become vital in the nomination process, many candidates conduct their own polls and some manipulate the results. Since polling outcomes can help boost the relationship between candidates and political parties, some candidates request polling merely to gain a political vehicle. A fraction of candidates hire a credible pollster to truly test the waters. Other candidates, to obtain the leading percentage of polling results, commission pre-nomination “tricky polls” to place themselves in an advantageous position.43) In this sense, these candidates do not overtly manipulate the results of the polling but they do set its parameters to, for example, limit the number of candidates and select the names included in the list so as not to endanger themselves in the final results.44) Simply put, to obtain an advantage from polling results, certain candidates pay unreliable pollsters, reduce the number of candidates tested, and exclude potential rivals from the polls.45) Through various means, candidates create polls to suit their purposes and use the results of such polls as a valuable bargaining tool to obtain a political vehicle in local leader elections.

Bribery Map

Local leader elections are sometimes marked by bribes to influence voters or community leaders to give support to and vote for certain candidates. Such bribery, commonly known as serangan fajar (literary “sunshine attack”), refers to money or goods that are usually distributed among voters early in the morning of the day of local leader elections.

One surprising use of polling is to create a map to plan for a sunshine attack. Political polling is normally considered to be an instrument for calculating a candidate’s level of support and for gauging a community’s desires. Nevertheless, with a simple one-step modification, polling can provide information to a candidate regarding the potential for vote buying and the particular areas in which such expenditures are necessary or useful.46) In special circumstances, polling identifies the area to target and the amount of money needed, as well as the way in which best to distribute the money.47) This method also identifies other factors that could sway votes and determines whether money affects voters’ choices. Simply put, the survey creates a map that describes areas that can be “bought” and areas that should be “neglected.”48)

Some candidates have become aware of the ability of polling to provide information useful for creating a bribery map. Although not all pollsters, particularly not academic and idealistic pollsters, agree to conduct surveys that include questions to identify a sunshine attack area, there are other pollsters that, without a doubt, offer to supply candidates with information relevant to such money politics.49) With a bribery map, candidates are able to identify how they can win the election not by gaining an absolute majority but by obtaining a mere simple majority. The map makes preparing a sunshine attack more efficient, because the amount that needs to be paid can be accurately calculated and its disbursement can be well organized, so that candidates can then “buy” only areas that are required to be bought.

According to a successful local leader candidate in East Java, a well-known pollster in the region has helped candidates understand in which area a sum of money should be distributed, how much on average, and by which means.50) A bupati (district leader) in South Sulawesi was tremendously impressed with the capacity of polling to generate recommendations for the effective use and efficient distribution of capital, thereby allowing money to be spent on the correct targets. The bupati even stated that polling had guided the delivery of bribes to precise targets. Assisted by polling results, a vice bupati was surprised to find that in his district there were certain areas where only the “Sarung and Mukena” (praying outfit), not money, was an effective buy-off for a sunshine attack.51) In addition, a party leader in East Java noted that polling provided a comprehensive map for both a “sunshine attack and an anti-sunshine attack.” The polling indicated which areas were controlled by a candidate or party and were their occupied “territory.” Using information provided by the map, political parties could decide which areas needed to be “guarded” and which needed to be “attacked.” Accordingly, the candidates’ success team deployed militant followers to keep their “territory” safe from the possibility of a sunshine attack by other candidates.52) In short, the creation of a polls-based bribery map can help a candidate to implement “modern” vote buying.

Voter Mobilization Map

Since the implementation of direct elections, there have been high expectations that voters with complete “autonomy” would determine the candidate most worthy of election. In fact, the current system of direct election still leaves room for the application of voter mobilization in some other ways. Voter mobilization is usually conducted by political actors utilizing parties’ militant followers, mass organizations, and even preman (thugs) to ensure that voters come to the polling station to vote. Voter mobilization is done directly and indirectly. Direct voter mobilization is when voters are visited and persuaded to take part in a ballot for preferred candidates. Indirect voter mobilization is when attempts are made to influence voters’ point of view with information so that their political decisions are in line with the interests of the political party concerned.

Until the end of 2005, elites’ guidance for voter mobilization came mostly from local networks, political party assessment, elites’ intuition, and information from the grassroots.53) However, along with the presence of polling in the Pilkada, political actors saw the opportunity to exploit polling to gain data for making an accurate map to guide voter mobilization. Some local politicians named this a “mobilization map.” Besides figuring out the possibility and the factors for swinging votes in a community, an overall map shows the areas that have been occupied, areas that are dominated by opponents, and areas that are still contested, as well as (most important) the extent of possible voter participation.54) This polls-based voter mobilization map is used as a guide for carrying out mobilization. It helps the candidate in protecting occupied areas and penetrating opponents’ areas. In the area that the preferred candidate has an advantage according to the map, voters are encouraged to come to polling stations and vote for the candidate. However, in areas controlled by opponents, the success team hires sukarelawan (volunteers)—and sometimes even utilizes local preman—to discourage and even intimidate voters from going to the polling stations. Discouragement is accomplished by de-legitimatizing the opponent with various political issues linked to a negative campaign.55) Thus, the indicator of success in discouragement is that the fewer the voters who come to the polling stations, the more successful the voter mobilization.56)

Besides the aforementioned ways of voter mobilization, information is spread in a tactic known as serangan udara (air attack) through local mass media, banners, and pamphlets. Candidates use the map for “push polling” in areas controlled by their opponents. Push polling represents an underhanded attempt to use the credibility of polling to spread rumors repeatedly via SMS (short message service) blasts, telephone calls, and door-to-door fake interviews.57) Compared to the period before polling came to the fore, this map does help political actors to identify the local political structure and voter dynamics. In short, polling results have provided political actors with valuable advice and information for mapping voter mobilization in local contests.

Inviting Indirect Bandwagon Effect

One impact of the dissemination of political polling outcomes is the so-called bandwagon effect. In academic discussions there are two types of bandwagon effect: direct and indirect. The former is a situation in which the polling outcome positively influences voters’ tendencies to support the candidate who, according to the polling, has the greatest chance of winning. The indirect bandwagon effect is when a candidate who has an excellent chance of winning gains even greater support from third parties, usually such elites as members of the mass media and businessmen. Both effects increase the advantage of the apparent future winner of the election (Young 1992, 20–21). Simply put, the first effect is support from voters in the form of electing the candidate in polling stations; the second effect is support from the elites that comes in the form of mass media coverage, financial support, and political collaboration.

Because the publication of polling results in local leader elections is usually limited and exclusively for candidates and inner circles, the indirect bandwagon effect is more likely to occur than the direct. For the former, the most likely subjects of bandwagoning are businessmen and members of the local mass media. Businessmen tend to get close to power to maintain their business opportunities and to sustain their business careers in a particular area. Accordingly, businessmen usually endeavor to support candidates in elections. The mass media, on the other hand, give more attention and coverage to possible winning candidates than to possible losers.

At least until the end of 2005, local elites, mass media, and businessmen provided support to a candidate after the candidate convincingly proved backup from mass organizations (Organisasi Massa, Ormas), had guarantees from the military, and had the backing of a reliable political party machine.58) At the time, businessmen and the mass media had difficulty knowing where support could be focused on. Prior to polling, businessmen, media, and local elites had no clear picture of which potential candidate would succeed. Therefore, taking sides with a particular candidate posed a dilemma. To cover all bases, businessmen, for instance, usually provided the same level of financial support to all candidates. The reasoning was that whoever won, they would be friendly with the businessmen.59) However, this traditional tactic was expensive. Businessmen who employed this method were also alleged to be playing “a set of cards” that was unsafe as it was associated with pragmatism and a lack of loyalty. However, supporting only one candidate carried a tremendous risk.

Polling in Pilkada has opened up new opportunities and has become a point of reference in garnering elites’ support. Polling outcome is evolving as an effective medium to guide the elites in providing support to certain candidates. There are at least two ways in which political actors use polling to solicit the indirect bandwagon effect in Pilkada. The first is that after the pre-election polling results are published, candidates or the success team actively deliver all beneficial information to businessmen and the mass media by elaborating on the polling outcome and explaining the best-case scenario regarding the potential winner. By doing so, the candidates and their team invite the so-called indirect bandwagon effect through which the candidates gain support and sponsorship from businessmen, news coverage from the mass media, and political endorsement from political parties’ elites.

This method is actually in line with current trends, where businessmen are no longer convinced simply by candidates’ old ways of showing support from mass organizations and political party machine networks.60) Mass organizations and party networks are less relevant in Pilkada, which rely mostly on individual voters. The connection with mass organizations is delicate, as such organizations cannot self-mobilize—they need a “locomotive” to work. They are also expensive, as the “fuel” of mobilization depends primarily on the power of money.61) Therefore, polling outcome is evolving into a new card for candidates to obtain backing, and it has been exploited to invite an indirect bandwagon effect. Although polling is not the only way to obtain support, the influence of polls’ outcome is inevitable and has always been part of the political persuasion. In other words, to obtain support from businessmen and mass media, candidates use their probability of winning the election, as shown by the polling outcome, to attract the indirect bandwagon effect.62) Thus, polling has changed the method by which businessmen take decisions on supporting political candidates.

The second way in which political actors use polling to attract the indirect bandwagon effect is that support (services and even financial) can come also from pollsters. Although this is not general pollster behavior, some pollsters have enthusiastically gone on to become political advisers after their surveys correctly indicated a potential winner. In polling players’ vocabulary, providing backup to the candidate most likely to win is known as bermain di atas gelombang (surfing on the wave). Some pollsters are even keen to help fund a candidate who has the potential to win an election.63) This is about more than fame; pollsters are more interested in the winning candidates’ investment in post-election projects. This trend has become a sort of business approach adopted by several pollsters in local and general elections. This is the other side of the workings of the indirect bandwagon effect in local leader elections.

Conclusion

Democratization at the local level has enabled political parties to use polling as a new instrument in local leader elections. Although the importance of polling in the dynamics of local politics, particularly in Pilkada, is quite new, polling has challenged the traditional approach toward party candidacy by pushing political parties to be more open to selecting popular and electable candidates.

A number of findings provide evidence of an unintended transformation in that polling has been used beyond capturing the voice of the people. Although tracking the people’s voice is generally a part of all polling activities, it seems that many political actors do not make maximum use of the polls to gauge the pulse of the public. Instead, political actors in local elections have been more interested in the short-term exploitation of polling solely to win elections.

Not surprisingly, current politics at the local level appears to be more complex in its internal configuration than is usually depicted. It appears that we need to provide more space for the discussion of polling in Indonesia’s local politics. There is also room for further discussion on the use of political polling in other developing democracies.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my academic supervisors, Professor Jun Honna and Professor Kenki Adachi; Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Jember University and the Directorate General of Higher Education of the Republic of Indonesia for my doctoral scholarship; and the Ritsumeikan University Office of Graduate Studies for a grant that enabled me to do fieldworks. I have greatly benefited from Dr. Marcus Mietzner’s insightful suggestions during a conversation in Freiburg, as well as comments and questions from the audience at the parallel session on “Elections” at the international conference on “Decentralization and Democratization in Southeast Asia: With a Special Section on 10 Years of Decentralization in Indonesia,” June, 15–17 2011, in Freiburg, where I delivered a previous version of this paper: “A Two-Edged Sword: The Emerging Role of Public Opinion Polling in the Local Politics of Post Suharto Indonesia.” I also thank my two anonymous reviewers. I am solely responsible for the contents of the paper.

Accepted: March 8, 2013

References

Buehler, M.; and Tan, P. 2007. Party-Candidate Relationships in Indonesian Local Politics: A Case Study of the 2005 Regional Election in Gowa, South Sulawesi Province. Indonesia 84: 41–69.

Camp, R. A., ed. 1996. Polling for Democracy: Public Opinion and Political Liberalization in Mexico. Wilmington: Scholarly Resources.

Carballo, Marita; and Hjelmar, Ulf, eds. 2008. Public Opinion Polling in a Globalized World. Berlin: Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

Centre for Electoral Reform (Anonymous). 2008. Jadwal Pelaksanaan Pemilihan Kepala Daerah [The local head election schedule]. Jakarta: CETRO.

http://www.cetro.or.id/newweb/index.php?pilih=com_detail&cetro_id=content-138, accessed August 18, 2008.

Choi, Nankyung. 2009. Batam’s 2006 Mayor Election: Weakened Political Parties and Intensified Power Struggle in Local Indonesia. In Deepening Democracy in Indonesia? Direct Elections for Local Leaders (Pilkada), edited by Maribeth Erb and Priyambudi Sulistiyanto, pp. 74–100. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Dewan Pimpinan Pusat Partai Amanat Nasional [National Assembly of Party Leaders of the National Mandate Party]. 2006. Ketetapan Rapat Kerja Nasional I Partai Amanat Nasional Nomor 11 Tahun 2006 [Decision No. 11 of the first national meeting of the National Mandate Party in 2006]. Jakarta: DPP Partai Amanat Nasional.

Dewan Pimpinan Pusat Partai Demokrasi Indonesia Perjuangan [National Assembly of Party Leaders of Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle]. 2010. Rapat DPP PDIP tentang Mekanisme Penjaringan dan Penyaringan Calon Kepala Daerah [Meeting of national party leaders Assembly of Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle regarding screening and recruitment of local leader candidates]. Jakarta. May 27.

Dewan Pimpinan Pusat Partai Demokrat [National Assembly of Party Leaders of the Democratic Party]. 2007. Peraturan Organisasi: Nomor 10/PO-02/DPP/PD/II/2007 Tentang Pemilihan Kepala Daerah dan Wakil Kepala Daerah [Organization Rule Number 10/PO-02/DPP/PD/II/2007 regarding political recruitment mechanism for local leader candidates]. Jakarta. February 9.

Dewan Pimpinan Pusat Partai Golkar [National Assembly of Party Leaders of the Golkar Party]. 2009a. Petunjuk Pelaksanaan Dewan Pimpinan Pusat Partai Golkar Nomor: Juklak-2/DPP/Golkar/XII/2009 [Operational guidelines of the National Assembly of Party Leaders of Golkar Party Number 2/DPP/Golkar/XII/2009]. Jakarta: DPP Partai Golkar.

―. 2009b. Rekapitulasi Pilkada Akhir Masa [Local leader election recapitulation in the end period]. Jakarta: DPP Partai Golkar.

―. 2005. Petunjuk Pelaksanaan Dewan Pimpinan Pusat Partai Golkar Nomor: Juklak-5/DPP/Golkar/XII/2005 [Operational guidelines of the National Assembly of Party Leaders of Golkar Party Number 5/DPP/Golkar/XII/2005]. Jakarta: DPP Partai Golkar.

Djohermansyah Djohan. 2004. Pilkada Langsung Perkuat Demokrasi di Daerah [Direct elections strengthen local democracy]. Kompas, December 17, 2004, p. 4.

Estok, Melissa; Nevitte, Neil; and Cowan, Glenn. 2002. The Quick Count and Election Observation: An NDI Handbook for Civic Organizations and Political Parties. Washington, DC: National Democratic Institute for International Affairs.

Geer, John G., ed. 2004. Public Opinion and Polling around the World: A Historical Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO.

Hadiz, Vedi R. 2004a. Decentralization and Democracy in Indonesia: A Critique of Neo-Institutionalist Perspectives. Development and Change 35(4): 697–718.

―. 2004b. Indonesian Local Party Politics: A Site of Resistance to Neoliberal Reform. Critical Asian Studies 36(4): 615–636.

Harris, Louis. 1963. Polls and Politics in the United States. Public Opinion Quarterly 27(1): 3–8.

Indonesia, Badan Pengawas Pemilu (Bawaslu) [Election Monitoring Body]. 2011. Press Release: Divisi Pengawasan Bawaslu pada Pelaksanaan Pengawasan Pemilu Kada Tahun 2011 [Press Release: Supervision Division on the Implementation of Local Leader Election Monitoring in 2011]. Jakarta. December 20.

Irman Yasin Limpo. 2010. Don’t Look Back! Makassar: Adhyaksa Publisher.

Johnson, Dennis W., ed. 2009. Routledge Handbook of Political Management. New York: Routledge.

―. 2001. No Place for Amateurs: How Political Consultants Are Reshaping American Democracy. New York: Routledge.

Leigh, Michael. 2005. Polls, Parties and Process: The Theater that Shapes the Outcome of 2004 Elections. In The Year of Voting Frequently: Politics and Artists in Indonesia’s 2004 Election, edited by Margaret Kartomi, pp. 19–34. Annual Indonesia Lecture Series 27. Clayton: Monash Asia Institute.

Lembaga Survei Indonesia [Indonesia Survey Institute]. 2004. Jajak Pendapat dan Pemilu di Indonesia pada 2004 [Survey of public opinion and the 2004 election in Indonesia]. Jakarta: LSI.

Manado Pos. 2010. Linneke-Jimmy, Koalisi [Linneke-Jimmy, Coalition]. May 27, 2010.

Mata Najwa. 2010. Episode: Solek Politik [The primping politics]. Metro TV, June 9, 2010.

http://www.metrotvnews.com/index.php/metromain/newsprograms/2010/06/09/5859/Solek-Politik, accessed July 6, 2010.

Mietzner, Marcus. 2009. Political Opinion Polling in Post-Authoritarian Indonesia: Catalyst or Obstacle to Democratic Consolidation? Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde (BKI) [Journal of the humanities and social sciences of Southeast Asia] 165(1): 95–126.

Mohammad Qodari. 2010. The Professionalization of Politics: The Growing Role of Polling Organisations and Political Consultants. In Problems of Democratisation in Indonesia: Elections, Institutions and Society, edited by E. Aspinall and M. Mietzner, pp. 122–140. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Norrander, Barbara; and Wilcox, Clyde, eds. 1997. Understanding Public Opinion. Washington, DC: Congressional Quarterly.

Saiful Mujani. 2004. Arah Baru Perilaku Pemilih [New direction of voting behavior]. Tempo, September 20, 2004. http://majalah.tempointeraktif.com/id/arsip/2004/09/20/KL/mbm.20040920.KL86885.id.html, accessed August 15, 2010.

Saiful Mujani; and Liddle, R. William. 2009. Muslim Indonesia’s Secular Democracy. Asian Survey 49(4): 575–590.

―. 2004. Politics, Islam, and Public Opinion. Journal of Democracy 15(1): 109–123.

Saiful Mujani; Liddle, R. William; and Kuskridho Ambardi. 2012. Kuasa Rakyat: Analisis Tentang Perilaku Memilih dalam Pemilihan Legislatif dan Presiden Indonesia Pasca Orde Baru [People power: Analysis of voting behavior in legislative and presidential elections in post-New Order Indonesia]. Jakarta: Mizan.

Schiller, Jim. 2009. Electing District Heads in Indonesia: Democratic Deepening or Elite Entrenchment? In Deepening Democracy in Indonesia? Direct Elections for Local Leaders (Pilkada), edited by Maribeth Erb and Priyambudi Sulistiyanto, pp. 147–173. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Ufen, Andreas. 2010. Electoral Campaigning in Indonesia: The Professionalization and Commercialization after 1998. Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs 29(4): 11–37.

Wlezien, Christopher; and Erikson, Robert, S. 2003. The Horse Race: What Polls Reveal as the Election Unfolds. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 19(1): 74–88.

Young, Michael L. 1992. Dictionary of Polling. New York, Westport, and London: Greenwood Press.

1) In academic discussions, the terms “polling” (polls) and “survey” are interchangeable and similar. The distinction between polls and surveys is not about the methodology, but merely the number of issues in the excavation process of public opinion. Polling usually deals with a single issue, while surveys deal with multiple issues (Norrander and Wilcox 1997).

2) In Indonesia, pollsters and polls-based political consultants are two similar entities with different duties. Most polls-based political consultants are polling agencies or pollsters. Yet not all pollsters are polls-based political consultants. Polling is the primary tool used by both pollsters and polls-based political consultants in their work. However, pollsters only conduct and publish the results of polls or surveys. Political consultants go farther by utilizing the results of polls or surveys to help their clients in the election. Obvious examples of pollsters are the polling agency Indonesian Survey Institute (Lembaga Survei Indonesia, LSI) and the Jakarta-based Institute for Social and Economic Research, Education, and Information (Lembaga Penelitian, Pendidikan dan Penerangan Ekonomi dan Sosial, LP3ES), which only carry out polls or surveys. In contrast, political consultants mainly, but not exclusively, carry out three major tasks: (1) vote mapping through conducting polls and surveys, focus group discussions, interviews with elites, and content analyses of local media; (2) vote influencing through ad design and production, campaign attribute design and production, and voter mobilization (door-to-door campaigns) as well as push polling; (3) vote maintenance through campaigner training, election witness training, and doing quick counts. Besides national political consultants, according to Irman Yasin Limpo (2010, 22–24), there are also many local political consultants.

3) Simply put, because of that review, the candidacy process can also be carried out individually. More specifically, the changes in Law Number 32 Year 2004, namely, Law Number 12 Year 2008, article 2, state that prospective local candidates can also be nominated by individuals with support from a set number of people. Independent candidates can run for election if a pair has support from 3 percent to 6.5 percent of the population in the region, depending on its size. That support, verified by copies of the supporters’ identity cards (Kartu Tanda Penduduk, KTP), must come from more than half of the sub-units of the particular region.

4) In practice, even though nominating through independent pathways is open and available for candidates, it cannot be said that independent pathways are easier than going through political parties because the process of collecting so many citizen ID cards (Kartu Tanda Penduduk, KTP) is not only intricate but also expensive. Interview with Yos Rizal Anwar, former bupati candidate of Lima Puluh Kota District, Jakarta, June 7, 2009.

5) Interview with Akbar Tanjung, chairman of the Trustees Board of the Golkar Party, Jakarta, June 15, 2010.

6) Interview with Heri Akhmadi, senior politician of the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle, Jakarta, May 31, 2010.

7) Interview with Akhmad Mubarok, chairman of the National Assembly of Party Leaders of the Democratic Party, Jakarta, June 14, 2010.

8) Interview with Kuskridho Ambardi, Jakarta, June 11, 2010.