Visualizing the Evolution of the Sukhothai Buddha

Sawitree Wisetchat*

* สาวิตรี วิเศษชาติ, The Glasgow School of Art: Digital Design Studio, 167 Renfrew St, Glasgow G3 6RQ, UK

e-mail: sawitreedesigns[at]gmail.com

DOI: doi.org/10.20495/seas.2.3_559

As Buddhism spread from India to cover much of Asia, sculptures depicting the Buddha varied regionally, reflecting both the original Indian iconography and local ethnic and cultural influences. This study considers how statues of the Buddha evolved in Thailand, focusing on the Sukhothai period (1238–1438 CE), during which a distinctly Thai style developed; this style is still characteristic of Thailand today. The Sukhothai style primarily reflects features of the Pala, Sri Lankan, Pagan, and Lan Na styles, yet contains new stylistic innovations and a refinement over the four successive schools that were subsequently lost in later Thai Buddhist styles. To analyze this evolution, first a conventional “visual vocabulary” approach is used, wherein 12 styles (precursors, contemporaries, and successors of the Sukhothai style) are described and summarized in a style matrix that highlights commonalities and differences. Then a novel application of digital “blend-shape animation” is adopted to assist in the visualization of differing styles and to better illustrate style evolution. Rather than comparing styles by shifting attention between sample images, the viewer can now appreciate style differences by watching one style metamorphose into another. Common stylistic features remain relatively unchanged and visually ignored, while differing features draw attention. While applied here to the study of Buddhist sculptures, this technique has other potential applications to art history, architecture, and graphic design generally.

Keywords: Southeast Asia, Southeast Asian art, Sukhothai Buddha, sculptural style, visual vocabulary, style analysis, digital animation, blend shapes

Introduction

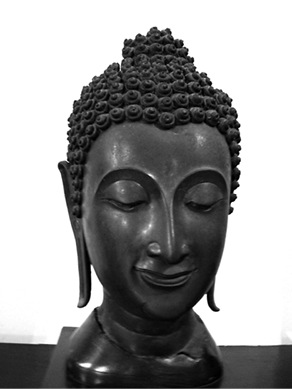

As Buddhism spread outward from India to cover much of Asia, both the teachings of Buddhism and the religious art evolved. The central artistic focus in traditional Buddhist practice is a statue that represents the Buddha, the historical figure of Siddhartha Gautama of the sixth to fifth century BCE. While Buddha sculptures follow common iconographic conventions (Rowland 1963, 12–14), the artistic style varies across regions and cultures, reflecting the local artistic interpretation of this iconography (Leidy 2008). This paper focuses on the evolution of the Buddha statue in the Sukhothai period (1238–1438 CE), during which a distinct style developed; this style is still characteristic of Thailand today (see Fig. 1). This style was not the first, nor the last, distinctly Thai artistic style, but it remains the most important: “A remarkable image, which combines Thai ethnic features with yogic tranquility and inner power . . . in a unified blend of grace and abstraction” (Fisher 1993, 178).

Like organic forms that evolve over time, an artistic style can be viewed as undergoing an evolution from its precursors, with moments of innovation and periods of stability. Unlike living organisms that evolve from a single precursor organism, artistic style often evolves by blending multiple precursor styles. In a sense, the successor style has the opportunity to borrow features or traits selectively from multiple parents, along with incorporating new features.

Conventionally, artistic style is analyzed through a written discourse with reference to illustrations of representative examples (e.g., photographs or drawings of museum artifacts). Differing styles are then compared by a differential analysis. However, an appreciation for these differences requires the reader’s visual imagination, and this is particularly challenging when analyzing style changes over time, wherein the reader must construct, from the chronological sequence of images, a sense for both the style and how it evolved.

In analyzing Buddha statues, it is conventional to start with the Buddhist iconography that is conveyed by, for example, the pose of the hands; the direction of gaze; and traditional elements of the head and face, including the presence of an ushnisha, the design of the finial (e.g., a lotus blossom or flame), the shape of the nose (e.g., a “hooked or hero’s nose”), the hair (“small snail-like coils of hair”), and the shape and expression of the mouth (e.g., “warm and serene”). Such a “visual vocabulary” has been used to broadly distinguish Buddha styles across cultures, such as Subhadradis’s (1991, 19) use of these phrases when comparing the Indian Pala style with the later Sukhothai style, or to make finer distinctions in the development of the Buddha style across periods within a given culture (see Galloway 2006, 198–204 regarding the Burmese).

When comparing two styles, it is common to supplement the written description with images, such as a photograph of a representative example of each style. The reader can then refer to these images, shifting gaze from one to the other to observe the prominent differences between the two. This task is not always easy, as the viewer must attend only to the differences in style and ignore differences in lighting, material composition, physical condition, size, camera perspective, and so forth. It would be preferable if all those irrelevant factors were removed and one could focus only on how the Buddha’s form and style changed. The central objective of this research is to explore a technique that allows one to visualize shape change without such distractions. Rather than static illustrations of reference material, digital animation is used to convey style differences. With this method, a viewer can appreciate style differences between two objects, A and B, not by shifting gaze from A to B but by watching A become B.

As is traditional, this study begins with a written analysis using a conventional visual vocabulary. A determination of the stylistic features that were potentially contributed by each precursor style is assisted by organizing the descriptors in the form of a matrix of features versus styles. In combination with historical sources, some style features associated with the Sukhothai can be traced back to their origins in precursor styles. Other features can be presumed to be inventions of Sukhothai artists. The complex nature of art history, and the patchwork of borrowing versus invention, however, cannot be easily resolved. What becomes important, then, is visualizing the changes, as much of the stylistic difference is better appreciated visually than by words or tabulations.

Overview of Cultures and Artistic Influences on the Sukhothai Style

Ancient kingdoms and empires each had a region of influence or power centered in a city (Kulke 1990; Thongchai 1994). The geographical arrangement of these city-states is an important starting point to understanding the Sukhothai Kingdom and the neighbors that influenced it. In addition to political power, there were foreign influences from trade from about the first century CE onward, which brought religions, culture, and artifacts to the indigenous people of the region (Van Beek and Tettoni 1991, 51; Gutman 2002, 38). The trade was either across sea and land from west to east, primarily from India through Burma to Thailand (Gosling 2004, 48), or along the coastlines and up the rivers. Indigenous peoples included the western-central Mon, who spread south down the Malay Peninsula and up the Chao Phraya River valley; the northern Tai, who derived from Chinese migrations from Yunnan Province; and the eastern Khmer (Wyatt 2003). In terms of political and religious influences in the region of Sukhothai prior to the beginning of the kingdom, the first foreign influences were extremely early, such as the influence of the Mahayana culture of the Indian Gupta Empire (320–550 CE) on the Dvaravati (Nandana 1999, 19; Gosling 2004, 68). While Hinduism and Islam largely replaced Buddhism in India, Buddhism spread rapidly outside of India, and Gupta-style Buddha statues with highly abstract and simplified forms were important in conveying the spiritual message (Fisher 1993, 55–56). Theravada Buddhism spread primarily from the north and west, while Mahayana Buddhism and Hinduism spread from the south and east (Van Beek and Tettoni 1991, 51; Nandana 1999, 19–24). Along with the Buddhist religion and iconography, Sanskrit writing was also incorporated in subsequent centuries by the art and religion of the various Dvaravati city-states and Khmer kingdoms (Brown 1996, 37). Buddhism also spread from Sri Lanka from as early as the fourth century CE across Southeast Asia, especially to present-day Burma (Gutman 2002, 36). It is particularly difficult to separate the Sri Lankan contribution, because the monks who spread Theravada Buddhism traveled broadly for centuries and influenced not only the people across much of Thailand (except the far eastern regions that were under the influence of the Khmer and Mahayana Buddhism) but also inhabitants of Burma before the Pagan Empire (1050–1287 CE) (ibid.). Buddhist monks from lower Burma were also in contact with Haripunchai (ibid., 38), a Mon center in present-day Lamphun, Thailand.

The Sukhothai Kingdom was centered in the city of Sukhothai, in north central Thailand. To the northwest was the Lan Na Kingdom (1281–1774), centered initially in Chiang Saen and subsequently in Chiang Mai, a separate city-state established by King Mangrai the Great (1239–1311 CE) with the conquering of the Haripunchai (Lamphun). The Lan Na Kingdom was bordered on the west by the Pagan Kingdom (Burma). South of the Sukhothai Kingdom were the Dvaravati principalities centered in U-Thong, Lopburi, and Nakhon Pathom. The Dvaravati, who were primarily Mon, practiced Theravada Buddhism. Artistically they displayed early Gupta influences (Gosling 2004, 56, 68) and then adopted the Khmer style as they increasingly came under the influence of the Khmer Empire by the tenth century and were finally conquered in the late twelfth century (Van Beek and Tettoni 1991, 64; Woodward 1997, 76). The Khmer style continued to persist in Lopburi and surrounding regions well into the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries as the U-Thong style (Woodward 1997, 124).

The city of Sukhothai was originally under Khmer influence, but it became independent in 1238 to form the Sukhothai Kingdom. When the Sukhothai Kingdom became independent, it was at the boundary between two very distinct cultures, the Khmer to the east and south, and the Dvaravati and Tai to the west and north. The Sukhothai Kingdom became allied with its neighbors to the northwest (particular the Lan Na Kingdom) and fought with its Khmer-influenced neighbors to the southeast (Wyatt 2003; Stratton and Scott 2004, 138–140). It grew into a broad band extending from the far northeast (near Laos) down to the Malay Peninsula. While they fought with the Pagan Empire to the north, the Sukhothai were followers of Theravada Buddhism and were closer culturally to the Pagan Empire than to the Khmer cultures of Hinduism and Mahayana Buddhism.

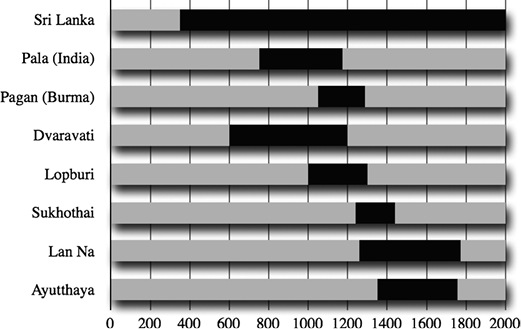

The time line in Fig. 2 shows that, at least chronologically, the potential cultural influences on Sukhothai art include Pala, Sri Lankan, Dvaravati, Lopburi, Pagan, and the neighboring Lan Na. Since the capital of the Sukhothai Kingdom was a city that had a long history of Khmer influence, one might expect Sukhothai art to reflect its Dvaravati or Khmer background. In fact, however, when the kingdom became independent, it shifted away from the Khmer style and adopted cultural influences from Sri Lanka (Woodward 1997, 146–149) as well as the early Lan Na Kingdom (ibid., 207–210) and, indirectly, the Pagan Empire. A later, more direct, Burmese influence has also been traced to fourteenth-century visits by Sukhothai monks (Gutman 2002, 40). The Lan Na influence continued throughout the Sukhothai period: “During the 13th and 14th centuries AD, there occurred significant artistic interaction between Lan Na and Sukhothai, although the exact nature of this interaction has yet to be studied” (Van Beek and Tettoni 1991, 133). The Sukhothai style reached the apex of its glory during the second quarter of the fourteenth century through to the end of the kingdom in 1438, when Sukhothai was incorporated into the kingdom of Ayutthaya (Woodward 1997, 145).

Fig. 2 Culture Time Line

Note: The Sukhothai Kingdom (1238–1438 CE) received Buddhist influences from Sri Lanka, India, Burma, and the contemporary Lan Na Kingdom. The Khmer-dominated Dvaravati cultures were geographically near the Sukhothai but less influential. The Sukhothai influenced the Lan Na and Ayutthaya cultures.

Primary Buddhist Sculptural Styles

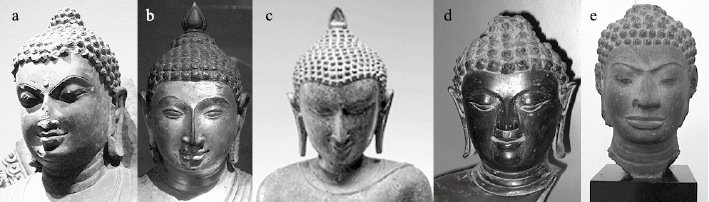

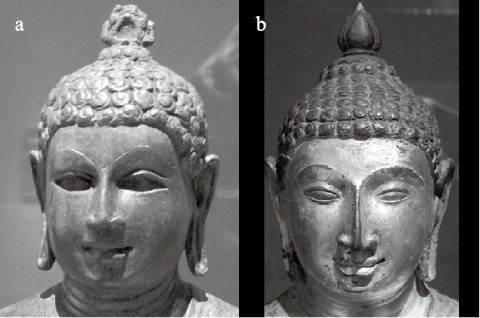

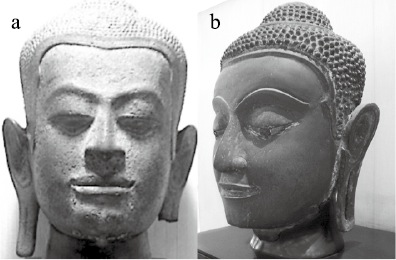

The cultures that predate and were potentially influential on the Sukhothai style were the Indian Pala, Sri Lankan, Burmese Pagan, and Lan Na. Figs. 3a–d show that while they share some common style aspects, their distinctive features may have contributed to the Sukhothai style, while the features presented by the Dvaravati style (Fig. 3e) had less in common with the Sukhothai (Fig. 1). It is important to note, however, that rather than a single school of style, there were four schools (General Group, Wat Trakuan, Kamphaengpet, and the Phra Phutta Chinnarat Group), each with its own distinct characteristics, during the Sukhothai period (Fig. 10). Subsequent to the Sukhothai era, the highly refined Sukhothai style was largely replaced by the U-Thong and Ayutthaya styles, which suggest a return to the Khmer style more than a continuation of the Sukhothai style. Artists who followed any one school of style created variations within it; hence, it is not possible to make absolute distinctions between any two styles. Nonetheless, it will become clear that a systematic visual vocabulary can help distinguish the features that comprise a given style, given a few representative examples of each.

Fig. 3 Examples of Precursor Styles

a: Pala, b: Sri Lankan, c: Pagan, and d: Lan Na. The Dvaravati style in (e), with strong Khmer influences, however, was not incorporated into the Sukhothai style. (a–c) at Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, (d) at Ramkhamhaeng National Museum, and (e) at National Museum, Bangkok.

Description of Buddhist Sculptures

The Buddha is believed to have exhibited the physical characteristics of a great man. A listing of characteristics is described in the ancient writings of the Digha Nikaya, or “Collection of Long Discourses,” part of the Pali Canon or Tipitaka scriptures of Theravada Buddhism (Shaw 2006, 114). The texts were known to Sri Lankan as well as Burmese monks and influenced Buddhist imagery and the early Thai aesthetic, especially the features of the Sukhothai style (Woodward 1997, 24, 25, 148) as early as the fifth century CE (Galloway 2002, 46). Among the many physical characteristics attributed to the Buddha, a few are relevant to the face: curled, untangled hair; a topknot or ushnisha (Krishan 1996, 111), as if crowned with a flower garland; a rounded forehead; large eyebrows arched like a bow; long earlobes; a nose like a parrot’s beak; a chin like a mango stone; and a beautiful smile (Rowland 1963, 12–14; Subhadradis 1991, 19; Van Beek and Tettoni 1991, 26–27; Fisher 1993, 178; Stratton and Scott 2004, 47).

These and other descriptions of ideal form have been influential in Buddhist art since the Gupta period in India, but many variations can be found in specific styles. The iconographic features are present in some, but not all, subsequent Buddhist sculptural styles. For instance, the “nose like a parrot’s beak” applies to the Sukhothai style but not to the U-Thong and Dvaravati styles. With the founding of Sukhothai in the mid-thirteenth century, a style emerges that is uniquely Thai (Stratton and Scott 1981, 67; Van Beek and Tettoni 1991, 7). Arthur Griswold (1953) regards the Sukhothai as “re-shaped in accordance with their recollection of other things,” including the descriptions from the Pali texts. Some sculptures show the eyes as downcast, and in others the eyes are opened and directed forward. The lips might form a smile or just assume a serene expression. Details of how the features were sculpted also vary. In some cases the eyebrows, lips, nose, and other facial features are depicted with natural amounts of curvature and relief, while in other cases the sculpting uses sharp creases and simplified, stylized curves. Many features of the statues in combination create a subtle impression of the gender of the statue. Buddha statues vary in the extent to which they appear masculine. Khmer and Dvaravati styles, for instance, have clearly powerful, masculine features, while the Sukhothai style is androgynous. An androgynous depiction of the Buddha de-emphasizes the male gender of the historic Buddha (Stratton and Scott 2004, 51, 138, 167, 337).

Analysis of Buddha Styles

This section provides an analysis of the Buddha styles considered in this study, using a visual vocabulary derived primarily from classical texts and modern descriptions (Sawitree 2011).

Pala Style

Fig. 4 shows four examples of the Pala style of Mahayana Buddhist statues. The eyebrows are a very important characteristic, with strongly sculpted double contours merged across the bridge of the nose. The crisp lines of the eyebrows are etched into the otherwise flat forehead. The overall facial proportions are broad, with moderately to distinctly masculine square jaws. The nose and chin are generally realistically depicted. A suggestion of a well-fed double chin is provided by lines around the neck. The lips are fleshy and vary from realistic to moderately sculpted, with outlined contours. The hair is depicted in neat rows of moderate to large coils. The hairline shows little evidence of a widow’s peak. The eyes are generally cast downward, not directed forward.

Fig. 4 Pala Style

a–c: from Bodhgaya, India, ninth century, at National Museum, Bangkok. d: from Bihar, India, eleventh century, at Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Sri Lankan Style

Two examples of the Sri Lankan style from the eighth to the tenth centuries are shown in Fig. 5. The Sri Lankan sculptures differ significantly from the Pala style in many respects. The topknot or ushnisha is often less prominent, but elaborate finials of various designs are added. The coils of hair vary from moderate to large, with generally more distinct details. The Sri Lankan statues usually have a rounder face, and a longer and narrower nose with a sharp ridge. Like in the Pala style, the Sri Lankan forehead is narrow to moderately wide with only a suggestion of a widow’s peak. Unlike the prominent double curve of the Pala eyebrow, the Sri Lankan eyebrows vary from only faintly outlined to sharply creased, and rather than terminate at the bridge of the nose, the curves sometimes merge smoothly with, and continue down, the long central ridge of the nose. The gaze of the eyes is frequently directed outward, not downward. The mouths vary from small to broad, with realistically sculpted lips. These Sri Lankan sculptures suggest a stylistic innovation that would appear in the later Sukhothai style, particularly in the contouring of the eyebrows and nose.

Fig. 5 Sri Lankan Style

a: late Anuradhapura period, 750–850 CE. b: Buddha offering protection, Sri Lanka, central plateau, late Anuradhapura-Polonnaruva period, tenth century. Both at Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Pagan Style

While Pala, India, is regarded as the “principal stylistic source” for the Pagan style of Buddha statues (Stadtner 1999, 54), by the eleventh century the Pagan Kingdom had developed its own distinct style; and by the end of the thirteenth century the Indian influence was “all but lost” (ibid., 58), with heads becoming more massive and disappearing into the torso. The depiction of the hair, in terms of the coils and the relative absence of a widow’s peak, remained similar to the Pala style. However, the deeply etched double contour of the eyebrows was gradually lost and the shape of the face changed from “sub-rectangular” to more triangular (Blurton 2002, 56), with a less masculine jaw line, a softer chin, and a diminished mouth, all realistically sculpted rather than sharply stylized (Bautze-Picron 2006, 37–39). More generally, the earlier Mahayana influence was largely ignored; the art evolved from Theravada iconography (Stadtner 1999, 58; Galloway 2006, 1–3, 198–200). Compared to the Sri Lankan faces, while both are rounded overall, the foreheads of the Pagan statues are broader and more prominent due to the reduced mouth and chin. The eyes of Pagan-style sculptures have a more obviously downward gaze (Galloway 2006, 200); and with small, pursed lips and an overall modest demeanor, the Pagan style evolved toward a warm and serene smiling face.

Fig. 6 Pagan Style

a: twelfth century, from New World Encyclopedia (2011). b: twelfth–thirteenth century, from Metropolitan Museum of Art (2011).

Dvaravati Style

Fig. 7 shows four examples of the distinctive Dvaravati style, which, of all Thai sculptures, most directly exhibits the early Indian influence (Gosling 2004, 66). While it displays some commonality with the Pala, it is regarded as deriving from the earlier fifth-century Gupta style. The faces of the Dvaravati images are less stylized, gentler, more approachable, and realistic (ibid., 68). A finial, if present, is small and cap-like, and the coils of hair are prominent and large. The Dvaravati Buddha’s face is overall broad, rather than elongated, with a masculine square jaw (more similar to Pala than Sri Lankan and Pagan), and more muscular than plump. The forehead is short (measured from eyebrows to hairline) and wide (measured from left to right), and dominated by perhaps the most distinctive feature of the Dvaravati style: strongly sculpted and delineated eyebrows that meet at the bridge of the nose and often define a continuous curve across the forehead. The ears have very heavy earlobes. The upper eyelids are heavy and blend smoothly and realistically into the eyebrows without a sculpted crease. The eyes are usually downcast. The nose is generally broad with a straight profile. In some statues the sharp ridge of the nose and broad continuous eyebrows form a “T” shape. The lips are large and full, and the mouth is expressive and sometimes gently smiling, all consistent with the Khmer cultural influence in this region. The chin is featureless, without the suggestion of a double chin.

Fig. 7 Dvaravati Style

a–c: Nakhon Pathom, Thailand, seventh–ninth century, at National Museum, Bangkok. d: eighth century, at Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Lopburi Style

The Khmer-influenced Lopburi style, also from current-day Thailand, shares some features of the Dvaravati style. While the overall facial proportions are somewhat more elongated, the depiction represents a similarly trim Buddha. It also shares the broad, full lips of the Dvaravati style, including the use of an inscribed outline for emphasis, but overall it has the more naturalistic and softly rounded sculpting of the Pagan style. The eyebrows, nose, eyes, and chin are generally very realistically depicted with only slight sculptural details. The Lopburi faces often show individual and expressive character (Woodward 1997, 114–115).

Significantly, the eyebrows have low arches and do not create a strong sculpted contour above the eyes. The eyebrows do not cross the bridge of the nose (as in some Pala and Dvaravati artifacts, Figs. 4 and 7), nor do they follow down the ridge of the nose (as in some Sri Lankan examples, Fig. 5). Instead, they are quite natural and not stylized. The eye shapes resemble some Sri Lankan examples. Except for the simplification of the eyelids and the double contour that outlines the lips, the proportions and curves of the Lopburi style are realistic. The depiction of the hair is also quite different, with a cap often replacing the coils of hair (ibid., 86).

Fig. 8 Lopburi Style

a–c: Lopburi, Thailand, thirteenth century. d: Khmer art, twelfth century. All at National Museum, Bangkok.

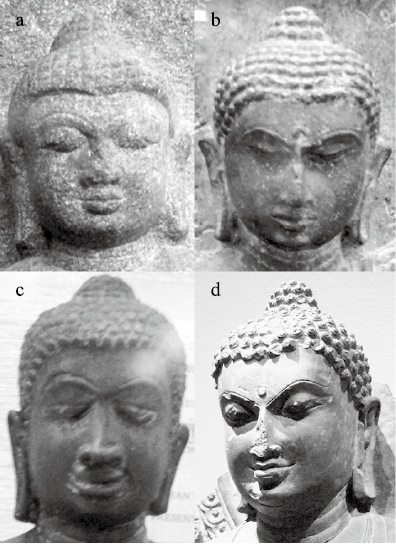

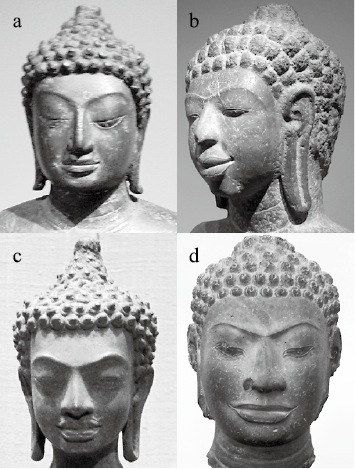

Lan Na Style

The Mon Hariphunchai (Lamphun), conquered by the Lan Na Kingdom in 1282, was the primary source for the earliest Lan Na sculpture, embodying a mix of Pala, Pagan, Mon, and even Khmer influences (Stratton and Scott 2004, 134). During the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries, the Lan Na style developed in close association with the Sukhothai, and both styles evolved away from the Mon aesthetic (Van Beek and Tettoni 1991, 133; Stratton and Scott 2004, 138). In the Lan Na style, a variety of finial shapes are added on top of a prominent ushnisha. The hair coils vary in size, and some hairlines in fifteenth-century statues suggest a widow’s peak (Listopad 1999, 57). The fourteenth- to fifteenth-century examples (see Fig. 9) are generally rounder and depict a heavier Buddha, with a creased and dimpled double chin (like a “mango stone”), and not the trim, strongly masculine square jaw of many Pala and Lopburi sculptures. While some features are quite variable, such as the depiction of the hair and nose, other features such as the eyebrows and eyelids are more consistent and exhibit the Sri Lankan style of sharply contoured eyebrows, eyebrows that merge with the bridge of the nose, and creases between the eyelid and eyebrow that follow the arch of the eyebrow (see especially Fig. 9b). The eyes are usually downcast. Curiously, the ears are often pointed, perhaps an influence from Laos (Stratton and Scott 2004, 51). The most distinctive aspects of the Lan Na style, including the highly arched eyebrows, eyelids with arched creases, and sharp, narrow noses, resemble some Sri Lankan examples and are also found in the Sukhothai style, which is elaborated upon next.

Fig. 9 Lan Na Style

a: fourteenth–fifteenth century, at Wat Chedi Chet Thaeo, Sukhothai, Thailand. b: fifteenth century, at Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. c–d: fifteenth century, at Wat Chet Yod, Chiang Mai, Thailand.

Sukhothai Style

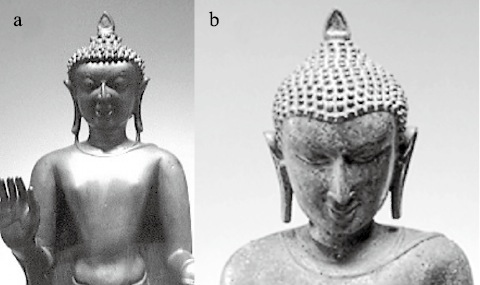

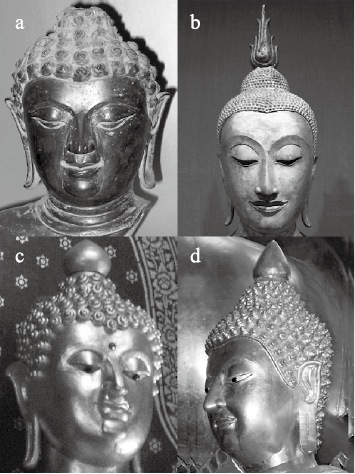

Four styles or schools are associated with the Sukhothai. These are the General Group, the Wat Trakuan, the Kamphaengpet, and the Phra Phutta Chinnarat (see Fig. 10). As a whole, the four schools share many common style features.

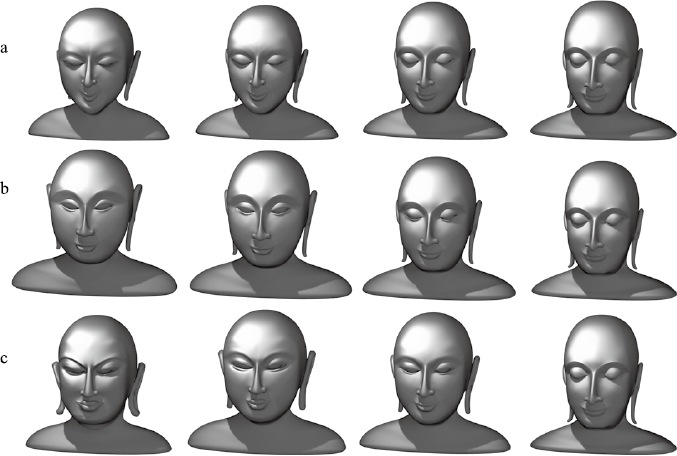

Fig. 10 Sukhothai Style

a: General Group, late thirteenth–fourteenth century, at Ramkhamhaeng National Museum, Sukhothai. b: Wat Trakuan, late thirteenth century, at Ramkhamhaeng National Museum, Sukhothai. c: Kamphaengpet, fourteenth–fifteenth century, at National Museum, Bangkok. d: Phra Phutta Chinnarat, fourteenth–fifteenth century, at Wat Phra Si Ratana Mahathat.

The General Group can be used as the basis for comparison with the other schools. The statues in the General Group and Kamphaengpet schools share the softly rounded, elongated faces of some examples from Sri Lanka, but many are more slender and graceful. There is variability in details such as the type of the finial, if present, but otherwise they share an immediately recognizable style. The Wat Trakuan Group shows variability within the group, while the subsequent Phra Phutta Chinnarat school is again quite consistent internally. The eyebrows in all four schools are highly arched with a sharply creased, sculpted curve that continues down the ridge of the nose (much as in the Sri Lankan examples in Fig. 5). The nose is generally hooked, or a “hero’s” nose, which is particularly parrot-like in some cases where the ridge is very sharp and narrow. The eyes are delicately curved and stylized, with re-curved upper eyelids and a sharp crease between the eyelid and the eyebrow. The eyes are downcast and slightly open. The lips, cheeks, and chin are generally lean and slender. Some Wat Trakuan school statues are less slender and have finial, hair coil, and hairline details in common with the earlier Pala and Dvaravati styles. This school shows some variability in the size of the hair coils, the type of finial, and the sharpness of the nose ridge; and while some statues are slender, others have a double chin, chubby cheeks, and a less elongated face overall.

The Sukhothai style is perhaps most distinctive in those examples where the face is lean and elongated and suggests effeminate form due to the delicate and graceful curves (Van Beek and Tettoni 1991, 114). These features are present in most statues of the General Group, and perhaps the style is most refined in the Kamphaengpet school, with detailed hair coils and finials. In contrast, statues from the last Sukhothai school, the Phra Phutta Chinnarat school, appear plump and well fed and more masculine. The facial proportions are less elongated, and the cheeks and chin are fleshier, with a rounded double chin, a cleft chin, and folds on the neck. The hairline is often lower and has a more prominent widow’s peak. Despite these differences, the Phra Phutta Chinnarat school shows the distinctive Sukhothai style of elaborate finials, sharply creased contours in the eyes and eyelids, and the way the eyebrows continue down the ridge of the nose.

U-Thong Style

Two successor styles, U-Thong and early Ayutthaya, are examined to see the influence that the Sukhothai style might have had on them. The U-Thong statues in Fig. 11 are distinctly different from the Sukhothai style in many ways. While there is considerable variation within the style, a few features are consistently different. The finial varies from an elaborate flame to being apparently absent altogether. The hair coils are much smaller than most of the Sukhothai examples (similar to the Kamphaengpet, but sometimes even finer). There is also a band that follows the hairline, which is a new addition. The robust facial proportions, broad full lips and jaws, and general feeling of masculinity and strength are similar to the Khmer-influenced Dvaravati and Lopburi styles. Within the style, there is variability in the sculpting of the eyebrows, from being defined by curved lines to appearing to have realistic thickness and shape. The eyebrows vary from a high arch to nearly straight; they do not continue in a sculpted manner down the sides of the nose. Similarly, the eyelids vary from having a crease to smoothly blending up to the eyebrows. The nose is generally realistic and not sculpted with exaggerated contours.

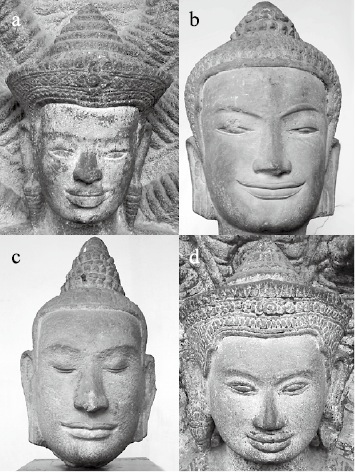

Ayutthaya Style

The Ayutthaya style (Fig. 12) is also more variable than the Sukhothai style. Nonetheless, it was clearly influenced by the Sukhothai sculptures. While the traditional finial above a topknot of hair resembles the Sukhothai style, sometimes it is replaced with an elaborate headdress or crown also seen in some earlier Mahayana-style Buddhas from Pala, Pagan, Hariphunchai, and Lan Na (Stratton and Scott 2004, 57). Likewise, the sculpting of the eyes, eyebrows, nose, and mouth often shows a Sukhothai influence. However, Pagan and Khmer influences are also clearly present. The Ayutthaya sculptures do not represent a single clear school. Instead, they show contributions from many cultures beyond that of the Sukhothai and, like the U-Thong style, might appear to step back to earlier traditional style features while simultaneously introducing new ones.

Fig. 12 Ayutthaya Style

a: thirteenth–fourteenth century, b: sixteenth–eighteenth century, both at National Museum, Bangkok. c–d: fifteenth–eighteenth century, both at Ramkhamhaeng National Museum, Sukhothai.

Style Summary

The Pala, Sri Lankan, Pagan, and Lan Na styles of Buddha sculptures were important precursors to the Sukhothai style. In contrast, the Khmer-influenced Dvaravati and Lopburi styles show little in common with the various schools of the Sukhothai. Upon closer inspection, some contributions of the precursor styles seem apparent. For example, the Sri Lankan style likely contributed largely to the eyes, eyebrows, and nose. Perhaps the Pagan influence contributed to the facial proportions, which were more elongated and slender than the Sri Lankan, Pala, or most of the Lan Na. It would be difficult to specify the origins of any single feature of the Sukhothai style with any degree of certainty, for not only were there centuries of trade and amalgamation of cultures prior to the formation of the Sukhothai Kingdom, but each neighboring culture was also assimilating the cultures of its neighbors. The practice of creating a sharp contour to the lips and eyelids shows up in several precursor styles, for instance. The origin of the Sukhothai style is certainly complex, and it will likely never be fully understood because of the lack of written records made at the time. Nonetheless, it is possible to compile a new picture of the manner in which some of the visual vocabulary of precursor styles may have added to what became the Sukhothai.

Most specialists concentrate on a particular style, such as Lan Na, or describe the various styles in shallower terms, across many centuries, cultures, and regions. It is beyond the scope of this work to address multiple styles in depth as well as breadth. The use of a style matrix, however, illustrates how an exhaustive study could proceed and the results be compiled.

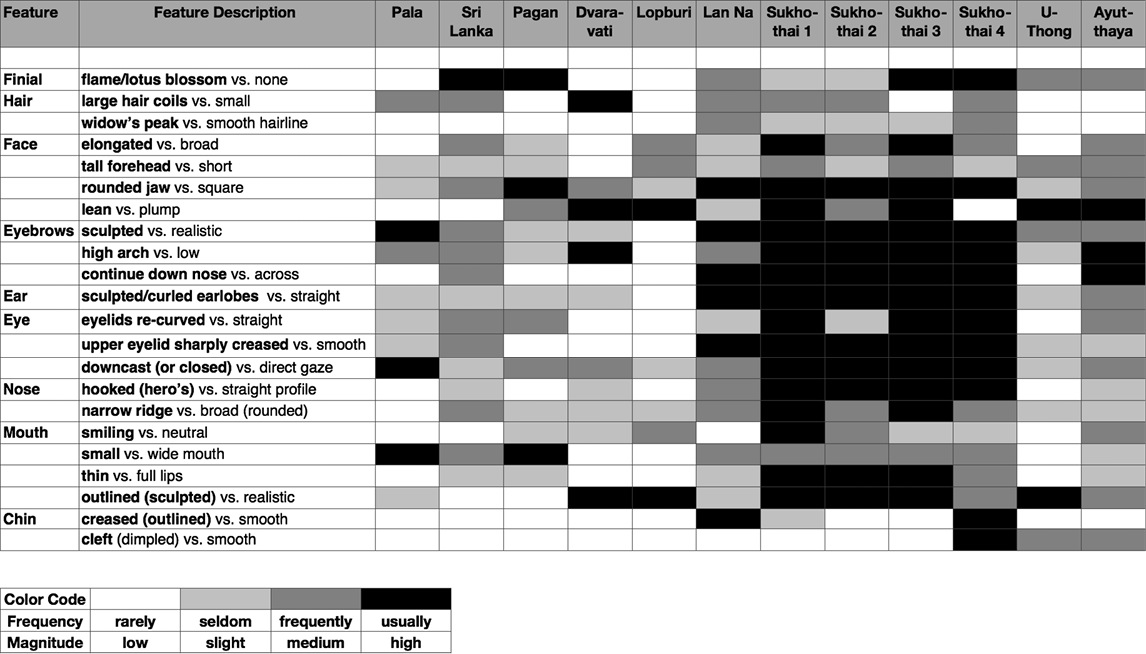

Table 1 shows this compilation as a matrix, with four levels associated with a given cell based on samples of the different Buddha styles. According to the color code (see the key in Table 1), the darker the cell, the more important the feature to a given style. For this study only four distinctions are made, either “rarely, seldom, frequently, and usually” for a feature that is present or absent in a given statue, or “low, slight, medium, and high” for a property that varies more continuously, such as lip fullness, or a square versus rounded jaw. For features such as the arch to the eyebrows, the cell color signifies the feature’s prominence or magnitude (from slight to high) over four steps. The features are in rows, and the styles across columns. The pattern values for different styles then show up as an arrangement of white, light gray, dark gray, and black cells in a column. With few exceptions, each Buddha style or school has so much variability within it (such as in Fig. 5 for the Sri Lankan style) that statistical methods would likely not be applicable, even if an exhaustive collection of sample statues were compiled from all available resources internationally, and a more quantitative scale created for each feature. The purpose of the matrix is not to measure differences across styles, but to help draw attention to where the differences lie. In Table 1, the eye is drawn to the large cluster of features that are held in common across the Sukhothai styles and shared, interestingly, with the Lan Na style but not with the earlier Khmer-influenced styles.

A table shows variations in features across styles in a way that is more illuminating and compact than reading a set of separate conventional written descriptions of each style, which typically rely on illustrations of examples. By visualizing a cluster of features that are present in one style and either shared with another or not, a tabulation is likely more efficient than a discourse.

While a matrix is a compact means to compare styles, it is not an effective means for visualizing the evolution of a style, nor is the conventional approach of describing change by textual descriptions. It is usually the responsibility of the reader to then consult images representative of the different styles and to visualize their differences by comparison. With a pair of images, one for each of two styles, this comparison requires detecting what is different and ignoring what is the same across the two examples. This study explores a far more effective means for directing visual attention to what is different between styles, and away from what the styles have in common.

The Sukhothai style is refined and elegant in ways that are not easily captured by written descriptions. Table 1 shows which features are predominantly found in the Sukhothai style and less so in the other styles, but does not hint at why the Sukhothai style is so striking. That is best shown, rather than described, and the method introduced in this study allows the qualities of the Sukhothai style to emerge by watching the other styles blend into the Sukhothai style.

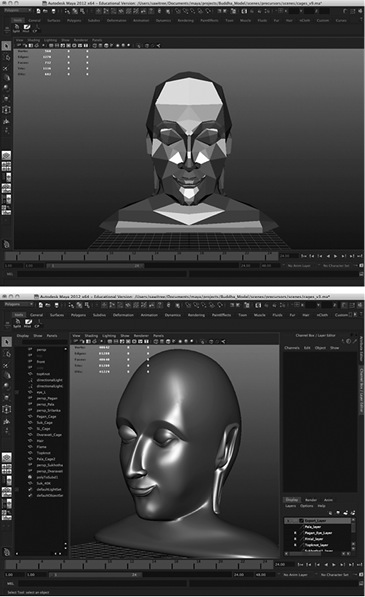

Modeling and Visualization

This study presents a technique for visualizing a sculptural style, and changes in that style, by having a model “morph” or blend between two or more such styles. This method illustrates style through animation. It uses the human ability to notice visible change in order to draw attention to where two styles differ, and away from where they are similar. The viewer observes one model that blends continuously from one style to another, while the material, lighting, viewpoint, and other factors that do not relate to style are kept constant. In this way, many of the irrelevant differences between two separate artifacts do not distract from attending to their differences in style.

The digital technique of “blend animation” has been widely adopted for use in character animation (Deng and Noh 2008). The method produces a smooth surface from a relatively simple “cage” of vertices. An initial or “base” cage is constructed that will be used as the basis for variations on that shape (see Fig. 13). Multiple copies of that base cage are constructed that will be made to resemble the other shapes. Each variation becomes a “target,” i.e., another shape that the base shape can be deformed into without adding or removing detail, but just moving and reshaping the details that are originally present in the base shape. The target shapes can be made to appear different from the base shape only by having their vertices shifted or displaced in 3D space relative to counterparts in the original base shape. With a base shape and target shape, a “blend shape” can then interpolate between the two shapes to form a continuous and smooth transition from the base to the target (see Fig. 14).

Fig. 14 Examples of Sequences of Animation

a: from Pagan to Sukhothai. b: from Sri Lankan to Sukhothai. c: from Pala to Sri Lankan to Pagan to Sukhothai.

The modeling of a given target shape is based on reference material. This reference can be photographs of museum artifacts that are placed in the 3D scene as “image planes.” The 3D model is then sculpted to resemble the reference object from that photographed viewpoint. The use of image planes is only approximate, however, and many photographs would be needed to ensure that the object has been modeled well from all viewpoints.

The result is best thought of as a three-dimensional illustration and not a precise replica of any specific artifact, with care taken to not exaggerate the style nor omit essential features. By working from digital models that can morph or blend between styles, we avoid the irrelevant issues in viewing actual artifacts either directly or in photographs, as mentioned earlier.

During the shape blends, the differences between the two styles draw one’s attention. For instance, if the nose changes from realistically rounded to highly sculpted and contoured, that instantly reveals an aspect in which the two styles differ significantly. Equally important, shared aspects of the two styles remain essentially unchanged and unnoticed. Blend animation reveals differences by change, and similarity by constancy. An effort is made to keep the essential proportions of the different sculptures similar, to minimize distraction by changes in overall size and shape, so that while the blending animation proceeds the viewer may focus on the style differences. The animations are encoded as movies and sampled as still frames. This study demonstrates that blend shapes can indeed effectively demonstrate style differences and evolution, but the modeling process is open-ended. It is impractical to create too close a replica, and like technical illustration in 2D, there is an art to efficiently conveying the essence. Unlike 2D illustration, however, this technique adds not only a third dimension (depth) but also a fourth (time) to show differences and evolution of style.

Conclusion

The Sukhothai style of Buddha sculptures may be regarded as a refinement and idealization of Buddhist form that emphasizes graceful contours and a face that is androgynous and abstract, with highly sculpted features and an expression of peace and serenity.

When a visual vocabulary is used to compile descriptions of the various aspects of the Sukhothai style, in comparison to its precursor and successor styles, a matrix such as Table 1 reveals a pattern that is nearly unique to the Sukhothai and similar to only some Lan Na and Sri Lankan examples. It is possible to go beyond using words and tables, to actually see the Sukhothai style as it differs from these other styles. Conventionally, photographs or diagrams are presented to illustrate different styles, where the viewer attempts to abstract away the essence of the style by comparing alternatives. That is a difficult task, especially when the statues differ in composition and condition, the photographs show them from different viewpoints and lighting conditions, and so forth. It is important to remember that much is lost when viewing a simplified model compared to the original, but something new and valuable is also gained when that model can transform dynamically from one style into another. Without the distractions that come with viewing real artifacts, the abstract model captures the essence of the style itself. Changes in the model, as it blends, capture differences in styles. One can then return to observe the original artifacts with new appreciation.

Having one style blend into another also allows the viewer to appreciate subtle overall differences, such as the feeling that is evoked by a style. For instance, by blending from a very masculine and physically powerful face of the Pala style to the Sukhothai style, the Buddha is seen to transform into a delicate and more abstract form that has lost some of its individuality to be replaced with calm serenity and ideal form. The visual and emotional impact of the change is more apparent, it seems, when this comparison is watched as a blend animation than when it simply is presented with adjacent examples of the two. Thus, blend animation between styles can be used not only to compare style features, but also to feel the emotional impact as the sculpture changes its character in front of your eyes. This might in turn provide insights into the ideals and motivations of the artists and their cultures.

Accepted: August 20, 2012

References

Autodesk. 2011. Maya-3D Animation, Visual Effects & Compositing Software. Accessed September 4, 2011, http://usa.autodesk.com/maya/.

Bautze-Picron, Claudine. 2006. New Documents of Burmese Sculpture: Unpublished “Andagū” Images. Indo-Asiatische Zeitschrift 10: 32–47.

Blurton, T. Richard. 2002. Burmese Bronze Sculpture in the British Museum. In Burma: Art and Archaeology, edited by Alexandra Green and T. Richard Blurton, pp. 55–65. London: British Museum Press.

Brown, Robert L. 1996. The Dvāravatī Wheels of Law and the Indianization of South East Asia. Leiden: E. J. Brill.

Deng, Zhigang; and Noh, Junyong. 2008. Computer Facial Animation: A Survey. In Data-Driven 3D Facial Animation, edited by Zhigang Deng and Ulrich Neumann, pp. 1–28. London: Springer-Verlag.

Fisher, Robert E. 1993. Buddhist Art and Architecture. London: Thames and Hudson.

Galloway, Charlotte. 2006. Burmese Buddhist Imagery of the Early Pagan Period (1044–1113). PhD dissertation, Australian National University. Accessed August 5, 2012, https://digitalcollections.anu.edu.au/handle/1885/47078.

―. 2002. Relationships between Buddhist Texts and Images of the Enlightenment during the Early Pagan Period. In Burma: Art and Archaeology, edited by Alexandra Green and T. Richard Blurton, pp. 45–53. London: British Museum Press.

Gosling, Betty. 2004. Origins of Thai Art. Trumbull, CT: Weatherhill.

Griswold, Arthur B. 1953. The Buddhas of Sukhodaya. Archives of the Chinese Art Society of America 7: 5–41.

Gutman, Pamela. 2002. A Burma Origin for the Sukhothai Walking Buddha. In Burma: Art and Archaeology, edited by Alexandra Green and T. Richard Blurton, pp. 35–43. London: British Museum Press.

Krishan, Yuvraj. 1996. The Buddha Image: Its Origins and Development. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers.

Kulke, Hermann. 1990. The Early and the Imperial Kingdom in Southeast Asian History. In Southeast Asia in the 9th to 14th Centuries, edited by David G. Marr and Anthony C. Milner, pp. 1–92. Singapore: Chong Moh Offset Printing.

Leidy, Denise Patry. 2008. The Art of Buddhism: An Introduction to Its History and Meaning. Boston: Shambhala Publications.

Listopad, John. 1999. Early Thai Sculpture Reappraised: Thirteenth–Sixteenth Century. In Art from Thailand, edited by Robert L. Brown, pp. 49–64. Mumbai: J. J. Bhabha.

Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2011. Standing Buddha [Burma]. Accessed September 4, 2011, http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/1993.235.1.

Nandana, Chutiwongs. 1999. Early Buddhist Sculpture of Thailand: Circa Sixth–Thirteenth Century. In Art from Thailand, edited by Robert L. Brown, pp. 19–33. Mumbai: J. J. Bhabha.

New World Encyclopedia. 2011. Image: PaganBuddha3. Accessed September 4, 2011, http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Image:PaganBuddha3.JPG.

Rowland, Benjamin Jr. 1963. The Evolution of the Buddha Image. New York: Asia House Gallery/Harry N. Abrams.

Sakchai Saisingha. 2004. Sukhothai Art: A View from Archaeological, Art and Epigraphic Evidence. Bangkok: Silpakorn University Printing.

Sawitree Wisetchat. 2011. Sukhothai: The Evolution of a Distinctly Thai Sculptural Style. MPhil thesis, University of Glasgow, The Glasgow School of Art.

Shaw, Sarah. 2006. Buddhist Meditation: An Anthology of Texts from the Pali Canon. London and New York: Routledge.

Stadtner, Donald M. 1999. Pagan Bronzes: Fresh Observations. In The Art of Burma: New Studies, edited by Donald M. Stadtner, pp. 53–64. Mumbai: Marg Publications.

Stratton, Carol; and Scott, Miriam M. 2004. Buddhist Sculpture of Northern Thailand. Chicago: Serindia Publications.

―. 1981. The Art of Sukhothai: Thailand’s Golden Age from the Mid-Thirteenth to the Mid-Fifteenth Centuries; A Cooperative Study. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Subhadradis Diskul. 1991. Art in Thailand: A Brief History. Bangkok: Amarin Printing Group.

Thongchai Winichakul. 1994. Siam Mapped: A History of the Geo-Body of a Nation. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Van Beek, Steve; and Tettoni, Luca I. 1991. The Arts of Thailand. Singapore: Ibis Books.

Von Schroeder, Ulrich. 1992. The Golden Age of Sculpture in Sri Lanka. Paris: Association Française d’Action Artistique.

Woodward, Hiram W. Jr. 1997. The Sacred Sculpture of Thailand. Bangkok: River Books.

Wyatt, David K. 2003. Thailand: A Short History. New Haven: Yale University Press.