Contents>> Vol. 5, No. 3

Political Dynamics of Foreign-Invested Development Projects in Decentralized Indonesia: The Case of Coal Railway Projects in Kalimantan

Morishita Akiko*

* 森下明子, Research Administration Office (KURA), Kyoto University, Research Administration Office Bldg., Yoshida-Honmachi, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto-shi, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan

e-mail: akikomori77[at]gmail.com

DOI: doi.org/10.20495/seas.5.3_413

Resource-rich Indonesia has been promoting massive infrastructure development projects involving billions of dollars in the aftermath of the Seoharto era. One area of intense focus is in Kalimantan which required infrastructure development for extractive industries, particularly coal. Since the early 2000s, the central and local governments as well as foreign companies have been interested in embarking on the first-ever railway construction projects for transportation of coal in Kalimantan. However, the projects have experienced several setbacks including changes to its original plans and delays to approvals. This paper explores the reasons why the local development projects could not progress smoothly from a political viewpoint. It argues that Indonesia’s democratization and decentralization have brought about unremitting struggles over power and resources among local political elites. Sometimes national politicians and even foreign investors are embroiled in the struggles of the local leaders when venturing into such development projects. The coal railway projects in Kalimantan highlight how local government leaders deal with the central government and foreign investors in their attempt to secure their position politically and financially in the venture, which would give them an edge over their rivals. This paper reveals the strategy of local power players who project themselves as defenders of local communities and the environment although a gap exists between their rhetorics and the realities on the ground in Kalimantan.

Keywords: Indonesian local politics, foreign investment for railway construction, coal transportation, Barito region, Kalimantan

I Introduction

Indonesian government leaders, both at the national and local levels, have promoted infrastructure development for extractive industries, particularly coal, at a time when global demand for it is rising. Local politicians in natural resource-rich regions are embarking on development projects at a rapid pace, using their influence as leverage to broker deals with foreign investors. The first-ever railway construction projects for coal transportation has been in the pipeline in Kalimantan since the early 2000s when feasibility studies were undertaken. However, several of the projects have experienced changes and delays. As a result, the construction of the railway tracks has yet to begin as of early 2016 and this paper explores the reasons why the multibillion-dollar development projects could not progress smoothly from a political viewpoint.

During the New Order period (1967–98), Indonesia was highly centralized and local authorities only acted as agents of the central government. Consequently, studies on international business-government relations focused on interactions between foreign firms and the central government (Khong 1980; 1986). In today’s decentralized Indonesia, however, provincial and district governments have extensive regulatory authority over local matters and hold the authorization rights for enterprises in their provinces and districts.1) District governments have the authority to issue a variety of business permits and licenses—such as a mining services business license (izin usaha jasa pertambangan, IUJP), a building permit (izin mendirikan bangunan, IMB), and an environmental permit (izin lingkungan)—within their own districts, while provincial governments have the authority to issue permits and licenses for business operations extending beyond a single district within a province.2)

Given that both the central and local governments participate in the processes of foreign investment projects, investors now “need to play a different game to get access to local resources, which becomes more complicated” (Priyambudi and Erb 2009, 15). Investors have responded to various demands from local governments, ranging from corporate social responsibility programs for local communities to bribery of officials, in order to develop a harmonious relationship with local stakeholders (Indra and Emil 2009). Some foreign companies, especially in the mining sector, also face protests and conflicts with local communities and NGO groups over land and environmental issues (Gedicks 2001; Indra and Emil 2009; JATAM 2010).

In addition to direct demands from and confrontations with local stakeholders, this paper demonstrates why foreign and multinational corporations—not to speak of the central government and Jakarta-based big companies—need to be aware of a different layer of political dynamics, specifically local politics, including intra-provincial power struggles as well as inter-provincial relations when venturing into local development projects.

In Indonesian political studies, many scholars have examined local politics since democratization and decentralization brought about unremitting struggles over power and resources among local political elites (Aspinall and Fealy 2003; Schulte Nordholt and van Klinken 2007; Erb and Priyambudi 2009; Hadiz 2010; Choi 2011). Some have also explored central and local government relations with a focus on the formation of new provinces (Okamoto 2007; Kimura 2012) and the privatization of state-owned enterprises (Wahyu 2005; 2006). The relationships between local governments and global players, however, have not been discussed thoroughly enough despite the fact that direct encounter between them occurs particularly at foreign investment project sites.

Thus, this paper gives a clear picture of the local-global relations in decentralized Indonesia, specifically a tripartite relationship of local governments, foreign companies, and the central government through the case study of coal railway projects in Kalimantan. It shows how local government leaders deal with the central government and foreign investors in their attempt to secure their position and financial assistance in the project venture, which would give them an edge in local power struggles. To put it another way, even a big foreign firm with immense financial clout and support from the central government can face difficulty in securing investment deals if its proposed project potentially undermines the power base of local political leaders.

This paper also illustrates how local power players secure their position in a project venture by manipulating the sentiments of local communities and environmental issues. Since the democratization and decentralization of Indonesia, local power players have more often than not exploited social and cultural issues for political purposes, particularly in direct elections for the positions of local government heads (Erb and Priyambudi 2009; Aspinall 2011). One of the most widely used campaign strategies is to promote the resurgence of customary culture and traditional institutions (Davidson and Henley 2007). Even while in power, as this paper demonstrates, local government leaders project themselves as defenders of local communities and the environment so that they will be able to hold a leading position in their negotiations with foreign and national players. This paper exposes a gap between this “defender of local communities and the environment” rhetoric and the reality on the ground when it comes to whether local power players really care for their region’s people and nature.

In what follows, this paper briefly describes the economic background of the development of railway projects in Kalimantan. It illustrates chronologically various efforts by the central and local governments and foreign companies to construct a railway network, and the arising conflicts of interests among them. In conclusion, the paper sets the direction for future research by providing an insight into the dealings of local leaders in the railway construction projects and the impact of local political conditions on foreign investment projects in Kalimantan.

II Coal behind the Railway Network

Coal has played an important role in Indonesia’s economic development; the country has extensive deposits—possibly sufficient for another 100–150 years to come (Daulay et al. 2007). The production of coal has been increasing steadily, growing from 40.1 million tons in 1995 to 75.6 million tons in 2000 and 152.8 million tons in 2005. In 2010, the total production of coal rose to 275.2 million tons. The increase in coal production is due to rising demand, especially from Asian countries, such as China, Japan, Korea, and India (Indoanalisis 2012).

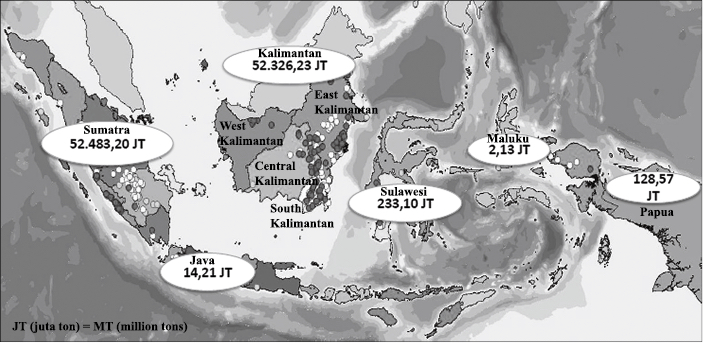

Today Indonesia is the largest coal exporter in the world, followed by Australia (Ewart and Vaughn 2009). Kalimantan has the second-largest coal reserves in the country (see Map 1), after Sumatra. Kalimantan is the biggest coal-producing region, having provided more than 93 percent of the country’s thermal coal production in 2011 (SALVA Report, 2012). Kalimantan’s coal is high-grade, with high calorific value and a low ash and sulfur content, which makes it saleable on the export and domestic markets (Harrington and Trivett 2012). The spread of coal reserves is mainly in East, South, and Central Kalimantan, where 69 mines operated as of 2005; there was only 1 mine in West Kalimantan (Hanan 2006).

Map 1 Coal Reserves in Indonesia (2011)

Source: Based on Kementerian Energi dan Sumber Daya Mineral (2012).

Provincial governments in Kalimantan recognized the necessity of building a railway network for more efficient transportation of coal from interior mining areas to ports of lading. At present, inland coal transportation in Kalimantan is conducted by trucks and barges that convey coal to an offshore loading point or a coal terminal for transshipment. The capacities of the existing road and river transportation networks for coal are quite limited. Yet, not a single rail line was constructed for coal transportation in Kalimantan, due to the high construction cost and weak institutional capacity to construct new railway lines—including the Railway Law (Law No. 13/1992), which only permitted the state-owned railway company PT Kereta Api Indonesia (PT KAI) to construct railroads (Hanan 2006).

In 2000 the Institute of Energy Economics Japan (IEEJ), a Japanese think tank, conducted a preliminary feasibility study on railway coal transportation in Kalimantan, based on its view that newly developed mines would be located farther inland than existing mines and that the use of barges for coal transportation might be unsuitable. Using a linear programming (LP) model, IEEJ determined the coal transportation route that could best maximize earnings of individual mines in Kalimantan as a whole. It estimated the production and transportation costs incurred by new mines, based on survey results of the currently operating mines, and prepared three scenarios for coal transportation routes: the existing truck and barge system, a combination of the existing system plus railway, and a railway network system. By running an LP model, IEEJ simulated the three scenarios and concluded that maximum earnings could be realized by using rail transportation to convey coal from mines rather than using existing road and river networks (IEEJ 2002).

A feasibility study for the provincial government of Central Kalimantan also stated that coal transportation by road was viable only for short distances and that rivers, like the Barito in the eastern part of the province, suffered from seasonal variations that made transportation during the dry season unreliable (Central Kalimantan Provincial Government 2009). Based on the recommendations of the feasibility studies that the railway network was a cost-effective, reliable all-season mode of transportation for coal resources, the central and provincial governments embarked on the Kalimantan railway network venture with foreign multinational companies.

III Development of Railway Projects in Kalimantan

Starting as a Big Regional Dream

The original concept of a vast railway network in Kalimantan began as part of a broader picture of regional economic cooperation and integration when a proposal for a trans-Borneo railway network was discussed at a meeting of the Brunei Darussalam-Indonesia-Malaysia-Philippines East ASEAN Growth Area (BIMP-EAGA) in 1997. Under the BIMP-EAGA railway project, the plan was to build a rail link between Brunei, Sabah, Sarawak, and Kalimantan and to form part of the Pan-EAGA Multi-Capital Transportation Network approved by the subregional grouping in 2000 (Europa Publications 2003, 218). The network would be used mainly for goods trains, with the aim of stimulating regional economic growth. Construction was to have begun in 2001, starting with a rail linking Sabah, Brunei, and Sarawak (Jakarta Post, April 21, 1999).

Historically, since the colonial days in Borneo, there have been railway tracks in Sabah and Brunei, covering only a small part of the northern area but not linked with each other. Roads and rivers have been the main mode of transportation in Kalimantan, Sarawak, Sabah, and Brunei. In Kalimantan, arterial roads connect a provincial capital to most district capitals and small towns within the province. There are also inter-provincial roads. But some stretches of road have been severely damaged and even destroyed, especially on routes used daily by trucks carrying tons of timber, oil palm, coal, and other heavy loads (Tempo Interaktif, August 3, 2012). River transportation is the main mode for people traveling between coastal towns and villages in the upstream interior areas.

At the international level, a cross-border road connects Pontianak, the provincial capital of West Kalimantan, to Kuching, the state capital of Sarawak.3) Yet, there is no road network connecting other provincial capitals in Kalimantan to the state capitals of Sarawak and Sabah or Brunei’s capital, Bandar Seri Begawan. Only small tracks and partly unpaved roads at the border areas are available for local people crossing the international border. Marine and air transportation is also used for cross-border flows of people and goods between Kalimantan and Sarawak, Sabah, and Brunei, but such modes are unsuitable for the daily mass transportation required to stimulate regional economic growth as envisaged by the BIMP-EAGA railway project.

In April 2000 a Sabah-based company, Keretapi Trans-Borneo Berhad (KTB), and the Kuala Lumpur-based Business Focus Sdn Bhd signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) in Kota Kinabalu to construct a 3,640 km trans-Borneo railway. It would link all major towns in Sabah, Sarawak, Brunei, and Kalimantan by the year 2010 (New Straits Times, April 18, 2000). It was supposed to be financed by German investors; and in June 2002 the German consulting firm, Project Development Management South East Asia, announced that it had allocated US$7 million for its feasibility study (Europa Publications 2003, 218). The project proposal was supported by the state government of Sabah, but neither the provincial governments of Kalimantan nor the state government of Sarawak were aware of it.

Despite the BIMP-EAGA’s big vision of regional integration, the proposed Borneo trans-regional railway project was abandoned. The Sabah-based KTB apparently gave up the plan due to lack of funding. The German companies, which were supposed to be the major players, also expressed some uncertainty over investing in such a project. According to Soenarno, then Indonesian minister of settlement and regional infrastructure, investors were concerned about a delay in the return on their investments since they were not sure whether the situation in Indonesia was conducive to investing (Tempo Interaktif, August 26, 2004).4)

Around the time that the BIMP-EAGA proposal was taking shape, Indonesia had also initiated its own plans for the construction of the first-ever railway system in Kalimantan as part of the trans-Borneo railway project. In 2002, at least 10 Indonesian private companies proposed forming a consortium for this mega project. Giving a push for the rapid progress of the railway infrastructure project, Minister of Settlement and Regional Infrastructure Soenarno granted provincial governors in Kalimantan permission to participate in it (Indonesian Ministry of State Owned Enterprises 2002). The four provinces—East, South, Central, and West Kalimantan—individually showed an interest in the railway project and offered to facilitate its preliminary feasibility studies, conducted through cooperation among the relevant agencies of the central government and foreign experts (Wanly 2012).

In August 2004 the Indonesian government decided to look for other investors for railway construction in Kalimantan and began asking the World Bank and Asian Development Bank to borrow capital. After Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono was elected to the presidency in October 2004, the inflow of FDI increased. It grew from US$1.9 billion in 2004 to US$8.3 billion in 2005, reaching US$13.3 billion in 2010 (ASEAN Secretariat 2006, 13; 2012). But for quite some time, the Indonesian government found it difficult to attract new investors for the railway project. A local newspaper in South Kalimantan reported in 2006 that even the provincial head of the Department of Mining and Energy was unable to confirm when construction would begin since it depended on investors. The reporter remarked that the project appeared to be just a dream (Radar Banjarmasin, July 28, 2006).

Local Governments Stay on Track

While the central government made little progress on the railway project, the provincial government of Central Kalimantan worked steadily on its own railway plan. Decentralization enabled local governments to engage in railway construction and operations. Government Regulation (Peraturan Pemerintah) No. 25/2000, linked to the Decentralization Law (Law No. 22/1999), defined the division of authority of the central and local governments such that district and municipal governments were given the authority to plan and construct a railway network in a single district or city while provincial governments were allowed to plan and construct railway networks connecting districts and cities within a single province.5)

A new Railway Law (Law No. 23/2007) also outlined and defined the three permits required for railway infrastructure: a business license (izin usaha), a construction permit, (izin pembangunan), and an operations permit (izin operasi). The central government has the authority to issue business licenses, while provincial governments have the authority to issue construction and operations permits for railway networks connecting districts and cities within a single province with approval from the central government. The district governments can also issue construction and operations permits with the recommendation of the provincial government and approval of the central government.6)

In line with those laws and regulations, Agustin Teras Narang,7) then governor of Central Kalimantan, signed an MoU with the Japanese company Itochu Corporation in 2007.8) The MoU was for a feasibility study for the construction of a 300 km railway running north to south within the Barito region in the eastern part of Central Kalimantan, and the estimated cost of the project was US$1 billion. Hatta Rajasa, then Indonesian coordinating minister for the economy, attended the MoU signing ceremony. Itochu had coal-mining concessions in Central Kalimantan and intended to build the railway in the region (Kompas, April 16, 2007).

Giving a background of the coal railway project in the Barito region, the provincial government stated the following:

Central Kalimantan is a major source of high-grade coal that is in demand nationally and internationally. The provincial government has already issued permits for the extraction of coal in large areas of the Barito River valley and actual extraction is now starting. However, there are significant constraints to the transportation of coal to the seaports on the Kalimantan coast caused by distance, remoteness of the area, and the lack of reliable transportation. Transportation by road is only feasible for comparatively short distances, and the Barito River suffers from seasonal variation, which makes transportation during the dry season unreliable except in the lower reaches of the river. (Central Kalimantan Provincial Government 2009, ii)

Fifteen big companies have conducted coal-mining operations, covering a 527,444 ha concession area in Central Kalimantan. Among them, seven have concessions in the Barito region, including the Itochu subsidiary PT Marunda Graha Mineral; the military-related PT Asmin Koalindo Tuhup; and PT Maruwai Coal, a subsidiary of the Australia-United Kingdom affiliated PT BHP Billiton Indonesia. Another 17 small and medium-sized coal companies also have concessions in the region but were not active as of 2009 (ibid., 9).

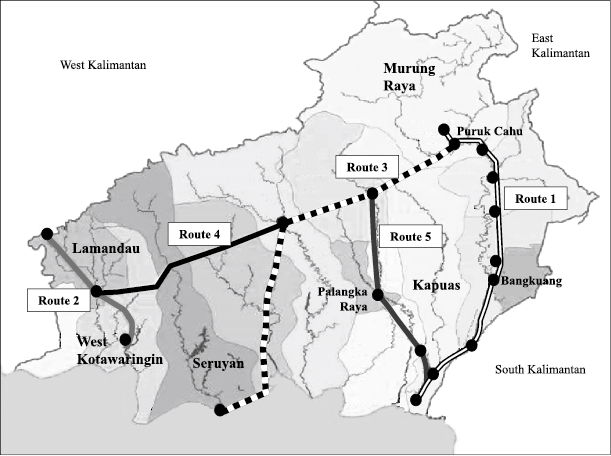

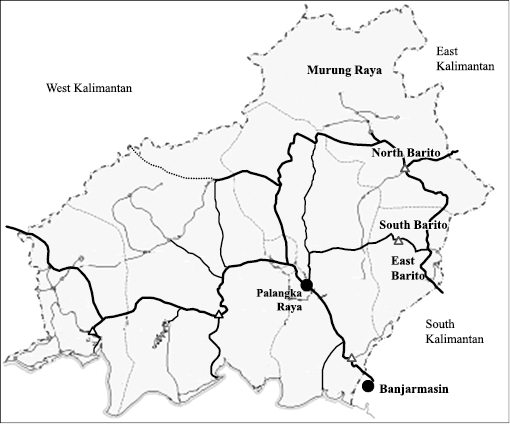

Under the planned Central Kalimantan railway network, the following five routes were chosen:

a. Route 1: 360 km railway running north-south from the interior district of Murung Raya in the upper Barito to a port in the coastal district of Kapuas in the southeastern part of the province (see Route 1 in Map 2);

b. Route 2: 195 km railway running north-south from the interior district of Lamandau to a port in the coastal district of West Kotawaringin in the western part of the province (see Route 2 in Map 2);

c. Route 3: 466 km railway running east-west in the mid-west part of the province, connecting Murung Raya District to a port in the southwestern district of Seruyan (see Route 3 in Map 2);

d. Route 4: 418 km railway running east-west in the western part of the province, connecting Route 2 and Route 3 (see Route 4 in Map 2);

e. Route 5: 390 km railway running north-south, connecting Route 1 and Route 3 via Palangka Raya, the provincial capital (see Route 5 in Map 2) (ibid.).

Map 2 Railway Routes Proposed by the Provincial Government of Central Kalimantan

Source: Based on Central Kalimantan Provincial Government (2009, 2).

In May 2007 Governor Narang also signed an MoU with China Overseas Engineering Group, a subsidiary of the state-owned China Railway Engineering Corp (CREC), on the construction of a 517 km railway connecting Route 1 of the above-mentioned proposal to a port in Seruyan District via Palangka Raya (Kompas, June 8, 2007).

The railway infrastructure is to be developed through a public-private partnership (PPP) scheme, which the central government has promoted to finance infrastructure development projects in the country since the Yudhoyono administration.9) Under the regulations of the PPP scheme, the government has to call for bids on a project and the tender winner is granted business licenses and permits.

In accordance with those regulations, the Central Kalimantan government asked for bids to be submitted for the construction of a 185 km railway between Puruk Cahu and Bangkuang in the Barito region as the first phase for Route 1. The tender winner would be given a permit for constructing the rail line and a concession to operate the railway for 30 years.

By 2008, 16 consortiums of foreign and domestic companies, including Itochu and CREC, had participated in the bid. After the screening at the end of 2011, the four consortiums that passed the tender prequalifications were: Itochu and PT Toll (an Australia-based transport and logistics firm); China Railways Group (a subsidiary of CREC) and two Indonesian companies called PT Mega Guna Ganda Semesta and PT Royal Energi; Dubai’s Drydocks World and PT MAP Resources Indonesia (an Indonesian engineering company); and PT Bakrie (one of Indonesia’s most powerful conglomerates) and Canada’s SNC Lavalin Thyssenkrupp. The four consortiums submitted their project proposals to the provincial government, and in 2014 a tender was eventually awarded to the consortium of China Railways Group and two Indonesian companies (Imam and Ester 2011; Antara News, October 13, 2014).10)

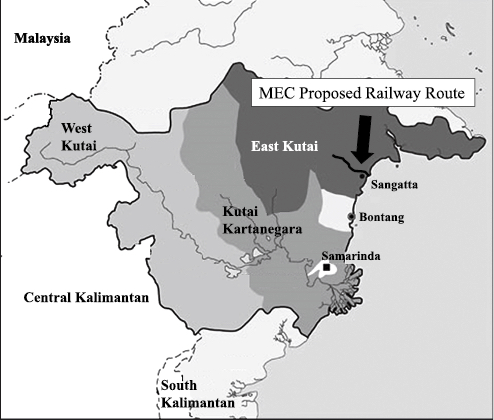

Keeping pace with its neighboring province, East Kalimantan proceeded with its own railway plan in partnership with foreign companies. In March 2009 the district head of East Kutai approved a plan to construct railway infrastructure in the district; the plan was proposed by MEC Holdings, a subsidiary of the Dubai-based Trimex Group. The railway network will be used for coal transportation from MEC’s mining concession area to a port terminal (see Map 3). The plan is part of the company’s US$5 billion investment in East Kalimantan to build industrial facilities, including a power plant, aluminum smelter, and fertilizer plant. The project received the complete support of the central government and the East Kalimantan provincial government (Railway Technology 2010).

Map 3 Location of Proposed MEC Railway Route

Sources: Based on Casson (2006, 67) and BAPPENAS (2013, 41).

Other foreign companies also participated in this mega project as a joint venture with MEC. India-based IL&FS Transportation Networks Limited is providing financing for the railway project as well as other projects planned by MEC. MEC also has partnered with Canada-based CANAC Railway Services for operating and maintaining the railway and port terminal. The feasibility studies for the railway line were conducted by UK-based ARUP and US-based KPMG. The two consulting companies identified the route of the railway line and the entire layout of the transport corridor, including the necessary infrastructure such as roads and bridges, terminal and jetty structure, and cargo-handling facilities for the railway line. They also prepared the possible timeline for the project’s construction and developed a complete financial plan and risk matrix for the railway line (ibid.).

MEC announced in March 2010 that it had completed the acquisition of land for the railway project in East Kutai District. Generally, in Indonesia developers face problems with local villagers when acquiring land for any project. However, an MEC representative said that the company had not experienced any such issues. He said the company’s biggest concern initially was that the villagers would not give up their land, but “the truth is villagers are the easiest people to talk to. If you go to them and tell them that your plan will create jobs, they will give you their land” (Bisara 2010). The company had to also deal with many stakeholders, such as ministries in Jakarta, politicians, local governments, along with villagers. Mahmud Azhar Lubis, the deputy chairman of the Indonesian Investment Coordinating Board (Badan Koordinasi Penanaman Modal), admired how “MEC handled all the complications in the land acquisition delicately, by talking to each member and stakeholder of the local community, without putting any pressure” (Trimex 2010).

Among other possible reasons for the smooth land acquisition were the company’s enormous financial capability for providing substantial financial compensation for the land acquired and paying for other miscellaneous expenses incurred during the process of coordination and negotiation with local stakeholders, and the expectations of villagers for more job opportunities created by the revitalization of the local economy with the construction of the railway infrastructure. Another factor could be the relatively narrow width of land used for building railway tracks compared with commercial logging and oil palm plantations, which need huge areas of land and sometimes encroach into natives’ customary land.11) Other factors could be the lack of information on possible negative effects of railway construction, such as environmental degradation with the opening of larger mines, and the massive influx of immigrant workers from overpopulated Java, who might take most railway-related job opportunities away from locals.

IV Center-Local Conflicts of Interest

The smooth progress of the railway projects at the provincial level encouraged the provincial governments in Kalimantan to gain more support from the central government for their regional development. In May 2010 the four governors of Kalimantan gathered in Jakarta to attend a National Development Planning Meeting (Musrenbang Nasional), and during their stay there, they worked hard to draw support from the central government, especially for the railway infrastructure project (Badan Perencanaan Pembangunan Daerah Provinsi Kalimantan Barat 2010).

Their efforts paid off a year later, in May 2011, when the central government introduced the Master Plan for the Acceleration and Expansion of Indonesia’s Economic Development 2011–2025 (Masterplan Percepatan dan Perluasan Pembangunan Ekonomi Indonesia, MP3EI), with the aim of transforming Indonesia into one of the 10 major economies in the world by 2025. MP3EI identified six economic corridors (Sumatra, Java, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, Bali-Nusa Tenggara, and Papua-Maluku Islands) to boost economic development, and it designated Kalimantan as a “center for production and processing of national mining and energy reserves” (Coordinating Ministry of Economic Affairs 2011a). The trans-Kalimantan railway infrastructure became part of the corridor project under which companies engaged in mining, particularly coal, would share the use of railways and roads constructed through a consortium model of a PPP scheme.

The central government also enacted certain necessary laws to facilitate infrastructure projects in Indonesia. In December 2011 the national parliament approved a land-acquisition bill that allowed the government to acquire private land more quickly in order to facilitate the development of new infrastructure projects such as roads, ports, power plants, airports, railways, dams, oil facilities, and other projects catering to the public interest.

During Soeharto’s New Order period, the government confiscated land easily by exercising the coercive power of the military. After 1998, democratization brought a reduction in the military power and a rise in the number of local protests against land acquisitions. This resulted in longer negotiation periods for acquiring land, with many cases taking as long as five years to settle. The new Law on Land Procurement for Development in Public Interest (Law No. 2/2012) and Presidential Decree No. 71/2012, clearly outlined the procedures for land acquisition. The law stipulates that the land acquisition process should be completed in less than 583 days. A landowner will receive cash compensation, alternative land, resettlement, shareholding, or something else agreed upon by the government agency and the landowner. The owner is required to release his or her land after receiving compensation or in accordance with a binding court decision in which the compensation will be deposited with the district court (Hanim and Afriyan 2011).

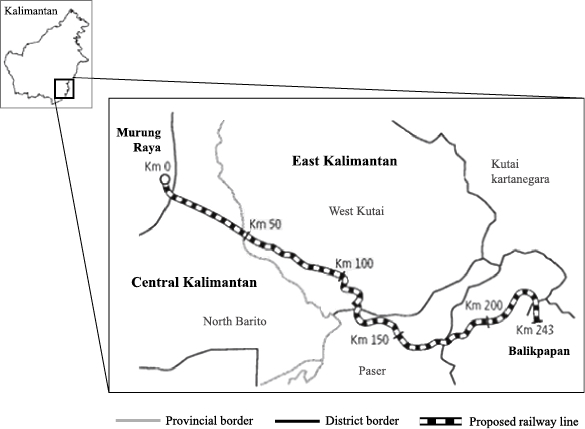

Serious steps were also undertaken by the central government to encourage foreign and domestic joint-venture investments in the trans-Kalimantan railway project. In June 2011 Hatta Rajasa, then Indonesian coordinating minister for the economy, was invited by the Russian government to attend the International Economic Forum. He took the opportunity to attract Russian investments for the food security, energy, trade, and transportation sectors as well as welcoming Russian participation in the trans-Kalimantan railway infrastructure project (Coordinating Ministry of Economic Affairs 2011b). During a Jakarta meeting in early August 2011 between Hatta Rajasa and Alexander Andreyevich Ivanov, the Russian ambassador to Indonesia, Russia confirmed its intention to invest US$2.5 billion for the construction of a 135 km railway link between East Kalimantan and Central Kalimantan to transport coal (Jakarta Post, August 1, 2011) (see Map 4).

Map 4 Central Government’s Proposed Trans-Kalimantan Railway Route

Source: Based on Kompas (February 8, 2012).

However, this Russian bilateral agreement with the central government created a conflict given that the rail line would connect coal mines in Central Kalimantan to a port in East Kalimantan. Soon after the Hatta and Ivanov meeting, Agustin Teras Narang, then governor of Central Kalimantan, expressed his stiff disagreement with the central government and opposed the railway plan linking the two provinces. Narang stated that Central Kalimantan had its own plan to build a railway network in the province. He also argued that the central government’s plan of a railway link could destroy the environment as the tracks passed through areas of protected forest,12) while the provincial plan would not involve forest clearing since the railway would be built alongside roads and rivers. Narang even said that he would resign as governor if the central government persisted with the Russian railway plan (Berita Daerah, October 12, 2009; Jakarta Post, August 4, 2011; Tempo Interaktif, August 8, 2011).

Following the governor’s objection, the provincial branch of the Dayak Customary Council (Dewan Adat Dayak, DAD), an organization of indigenous people in Kalimantan, also voiced its opposition to the central government’s plan. Governor Narang is the president of the National Dayak Customary Council (Majelis Adat Dayak Nasional), DAD’s umbrella organization. Provincial DAD members were concerned that natural resources from Central Kalimantan would be taken to East Kalimantan through the railway and nothing would remain in their own province (Surya 2011).

On the other hand, an environmental NGO called the Indonesian Forum for Environment (Wahana Lingkungan Hidup Indonesia, WALHI) disagreed with the railway plans of both the central government and the provincial government, saying that the project could harm not only the environment but also the safety of people living alongside the Barito and Mahakam Rivers since the railway network would pass through the catchment areas (Jakarta Post, August 7, 2011).

In fact, the provincial government acknowledged the possible environmental impact on the Barito region caused by the railway construction. However, it justified the project from an engineering point of view by saying:

Throughout this part of Central Kalimantan, there are very significant environmental issues connected with coal mining and commercial forestry. Of particular concern is . . . coal roads from the coal mining areas to the Barito River. . . . The road corridors are wide and the construction and operation of these roads have caused: loss of forest cover for long distances, significant dust creation particularly during the construction phase, blocking of local drainage channels and only limited replacement of cross and parallel drainage. Although the rail construction and operation will cause environmental impacts it is likely that these impacts will be less than impacts caused by the continued construction of coal roads. In addition the environmental benefits of rail for the transportation of coal will be greater if the construction of new coal roads is restricted for all new coal mines. Coal roads will still be necessary from the mine to the rail head, but coal roads to the Barito River will not be necessary. (Central Kalimantan Provincial Government 2009, 16)

This statement indicates that the provincial government used different arguments and logic to push through its own railway plan depending on whom it had to persuade. The provincial government actually recognized that the rail construction and operations would cause an impact on the environment. Thus, it used the rhetoric of “a less-damaging way of infrastructure development” to persuade local stakeholders to agree to the provincial railway project while using the rhetoric of “defender of local communities and the environment” to oppose the central government’s plan.

Moreover, some domestic NGOs such as WALHI and the Indonesian Mining Advocacy Network (Jaringan Advokasi Tambang, JATAM) were aware of another possible environmental impact—that the vast railway network would see a rapid increase of coal exploitation in Kalimantan. Based on research by the two NGOs, JATAM reported that coal-mining and transportation operations by some companies had caused dust pollution, displacement of indigenous communities, and disruption and threats to clean water supplies due to river pollution in several mining areas in Kalimantan (JATAM 2010). However, the provincial government turned a blind eye to such possible destructive consequences after the construction of the railway.

From the double-talk and selective criticisms of the provincial government, it is likely that a concern for local communities and the environment is not the real reason for the provincial government to push through its own railway project and oppose a cross-provincial railway network planned by the central government. As demonstrated in the following section, the provincial government had another reason to adhere to its own railway plan.

V Local Struggle over the Barito Region

Governor Narang’s opposition to the central government’s railway plan to link Central and East Kalimantan was not essentially due to his concern for local communities and the environment. Along with a fear that the profits from his province’s natural resources would be intercepted by the neighboring province, there was also a perceived risk that he would lose regional control, economically and politically, in the Barito region.

The main channel of transportation in the Barito region is the Barito River, which flows from the northeastern part of Central Kalimantan to Banjarmasin, the provincial capital of the neighboring province of South Kalimantan. This has made Banjarmasin a key hub for logistics and commerce in the Barito region, although a major portion of the region administratively belongs to Central Kalimantan. Coal and other commercial products such as timber, rubber, and palm oil from the upstream Barito districts are transported via the river to a port of lading in Banjarmasin, and commodities headed to the interior towns also have to go through Banjarmasin (see Map 5).

Even the road network connecting districts in the Barito region to Palangka Raya, the provincial capital of Central Kalimantan, has to pass through Banjarmasin. There is a northern mountainous route connecting the Barito region to Palangka Raya, but it has been badly damaged by heavy trucks rumbling down the road daily. Therefore, people prefer to take a southern route via Banjarmasin to go to the Barito region from Palangka Raya (see Map 6).

Map 6 Road Network in Central Kalimantan

Source: Based on Kementerian Pekerjaan Umum dan Perumahan Rakyat, Republik Indonesia (2012).

Hence, it is likely that Narang viewed the central government and Russia’s railway plan connecting the Barito region to East Kalimantan as taking the Barito region farther away from the control of the Central Kalimantan government (see Map 4). On the other hand, the Central Kalimantan provincial government’s railway network plan would first connect districts in the Barito region and then extend the railway track to a port of lading in Kapuas District, located in the southeastern part of Central Kalimantan (see Map 2).

Not only economically but also in part socially and politically, the Barito region has been closer to South Kalimantan than Palangka Raya. In the lower Barito region, local residents are mainly Banjarese—Malay descendants of aristocrats and subjects of the Banjar Kingdom (1526–1860) centered in South Kalimantan—while Dayaks live mainly in the middle and upper Barito regions. One of the major Dayak sub-ethnic groups in the region is the Bakumpai, making up 36.4 percent of the 36,2815 total population of four districts (Murung Raya, North Barito, South Barito, and East Barito) in the middle and upper Barito regions (Badan Pusat Statistik 2001, 75). Bakumpai people converted to Islam under the strong influence of the Banjar Kingdom, while many other Dayaks converted to Christianity or continue to practice varieties of animism. Narang is a Christian Dayak Ngaju, a major Dayak sub-ethnic group in the central part of Central Kalimantan that makes up 39.9 percent of the 670,218 total population of three districts in the provincial central part (Kapuas, Gunung Mas, Pulang Pisau) and Palangka Raya (ibid.).

The Bakumpai people also dominate politics in the Barito region. The current district heads of North Barito, South Barito, and East Barito are of Bakumpai descent. Since 1999, Bakumpai politicians have played a leading role in proposing the formation of a new province of Barito Raya, consisting of Murung Raya, North Barito, South Barito, and East Barito in Central Kalimantan and the district of Barito Kuala in South Kalimantan. If the new province is established, profits from the natural resources in the Barito region, including coal, will fly out of the hands of the Central Kalimantan provincial government and land in the hands of Bakumpai politicians.

In order for the formation of Barito Raya to materialize, the Bakumpai politicians also attempted to extend their influence at the provincial level. In the 2010 gubernatorial election, two pairs of candidates for governor and vice governor campaigned for the formation of the new province of Barito Raya. One pair was Achmad Amur, the Pulang Pisau district head, and Baharudin H. Lisa, the South Barito district head; and the other was Achmad Yuliansyah, the North Barito district head, and Didik Salmijardi, the former district head of East Kotawaringin. They had a close contest with the pair of then incumbent governor Narang and vice governor Achmad Diran.

While Achmad Amur is Banjarese, Baharudin H. Lisa and Achmad Yuliansyah are Bakumpai. Achmad Diran and Didik Salmijardi are immigrants of Javanese descent, a category that makes up 18.1 percent of the total population in Central Kalimantan (ibid.). In the gubernatorial election, Narang and Achmad Diran won 42.3 percent of votes, while Achmad Amur and Baharudin H. Lisa gained 37.7 percent and Achmad Yuliansyah and Didik Salmijardi gained 15.7 percent (Noorjani 2010). Narang and Bakumpai politicians are certainly political adversaries, and thus Narang has to defend a provincial railway plan at all costs in order to retain the resource-rich Barito region in his province.

VI Intra- and Inter-provincial Politics over Railway

A Conciliatory Move

In response to Governor Narang’s objection to the interprovincial railway plan, Hatta Rajasa, coordinating minister for the economy, called on Narang to compromise on the provincial railway project. He stated that the railway project proposed by the provincial government had not materialized yet, and that the central government’s plan was more feasible than the provincial one since the latter intended to build a long railway, which would cost too much. Hatta ensured that the central government would review the railway route so that it would not pass through protected forest areas (Tempo Interaktif, August 8, 2011). While facing opposition from Central Kalimantan, the central government continued the discussion with Russia on the trans-Kalimantan railway project, which became one of the agendas for the Russia-Indonesia High Level Meeting on Bilateral Economic Cooperation in Jakarta in October 2011 (Media Indonesia, October 27, 2011).

The central government made a conciliatory move in November 2011 to resolve the deadlock with the provincial government of Central Kalimantan over the railway project. The government-sponsored Indonesian Infrastructure Financial Guarantee Fund (PT Penjaminan Infrastruktur Indonesia, PII), which was launched in May 2010 for the purpose of providing guarantees for infrastructure projects under the public-private partnership scheme, agreed to guarantee a railway project planned by Central Kalimantan. PII would guarantee investors from risks that could arise from licensing delays, land acquisition, and government policy changes (Jakarta Post, December 1, 2011).

East Kalimantan as Willing Ally

In contrast to Central Kalimantan, the provincial government of East Kalimantan welcomed the railway plan proposed by the central government and Russia. The East Kalimantan government dispatched its delegation to Marketing Investment Indonesia in Moscow in September 2011 to undertake a possible business partnership with Russian investors. Awang Faroek Ishak,13) the governor of East Kalimantan, and Andrey Shigaev, director of Kalimantan Rail—a subsidiary of Russian Railways Group, a public-private partnership railway company—signed an MoU in February 2012 on the construction of a 275 km railway and associated infrastructure in Kalimantan.

Russian Railways is the fourth-largest company in Russia by revenue, with over 1195.2 billion rubles (about US$40 billion) in 2010. The project consists of two phases. The first one involves building a railway between coastal Balikpapan and inland district of West Kutai in East Kalimantan, which will connect to the neighboring province of Central Kalimantan in the second phase. The total project investment would be US$2.4 billion. The MoU signing event was attended by the Russian ambassador and representatives of Russian Railways and the Russian state-owned Bank for Development and Foreign Economic Affairs (Vnesheconombank). The Indonesian attendees were the deputy coordinating minister for economic affairs, the director general of the Indonesian Ministry of Transport, the director for Central and Eastern European affairs of the Indonesian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, district heads of East Kalimantan, and other officials (Embassy of the Russian Federation in the Republic of Indonesia 2012).

Russia is so serious about its investment in the trans-Kalimantan railway project that it established the Export Insurance Agency of Russia in November 2011 to facilitate the project. For the Russian government, the railway construction is needed to support the plans of the Enplus Group, a Russia-based diversified mining, metals, and energy group owned by the Russian billionaire Oleg Deripaska, which plans to acquire a coal-mining company in Indonesia (Algooth and Stefanus 2012b).

In order to avoid any conflict with the Central Kalimantan provincial government, the Russian government stated that the Kalimantan railway would pay special attention to avoid all protected forests in the area. It also mentioned that the project would require careful planning and coordination with other existing projects in Central Kalimantan (Embassy of the Russian Federation in the Republic of Indonesia 2012).

However, Narang again voiced his strong opposition to the project on the day of the MoU signing ceremony between East Kalimantan and the Russian investor. He said the Central Kalimantan government would not participate in the Russian-planned railway project. He reiterated the argument that according to the Russian plan, the railway line would be constructed in a protected forest area in the Muller-Schwanner mountain range in Murung Raya District, which serves as a water catchment area (Algooth and Stefanus 2012a).

The Russian investor was forced to shelve part of the project. In March 2012 Shigaev, the director of Kalimantan Rail, said that only after Central Kalimantan finished its own railway project would his company start to build the rail line connecting Central Kalimantan and East Kalimantan. Syahrin Daulay, the head of the Provincial Regional Development Planning Agency (Bappeda) in Central Kalimantan, confirmed in April 2012 that the four governors in Kalimantan had agreed to build a rail network in their own regions first and after that the interconnection among provinces would be constructed (Tempo Interaktif, April 16, 2012).

District Power Play

While Governor Narang opposed the railway link between the two provinces, Achmad Yuliansyah, then district head of North Barito who was one of Narang’s rival candidates in the 2010 gubernatorial election, welcomed the MoU between East Kalimantan and the Russian investor. Without giving any notice to Narang, Yuliansyah signed an MoU with Ismail Thomas, the district head of West Kutai in East Kalimantan, a northeastern neighboring district of Central Kalimantan, on cooperation for interdistrict infrastructure development—including the railway between the two provinces, which the provincial government of Central Kalimantan strongly opposed (Antara News, March 1, 2012).

The MoU obviously outraged Narang. Siun Karoas, then provincial secretary of Central Kalimantan, stated that the provincial government strongly deplored the MoU signed by the district governments of North Barito and West Kutai without any consultation with the provincial government (Agustin Teras Narang Center, March 7, 2012). Narang immediately issued a letter of request to cancel the MoU between the two districts. Achmad Yuliansyah then made a rebuttal statement that it was the provincial government that had long ignored the North Barito district governments’ asking for support for infrastructure development such as a local airport, hospital, bridge, and so forth. He also said that the interdistrict cooperation and coordination for infrastructure development across the provincial border had been discussed since 2004 (Kalteng Pos, March 15, 2012).

South Kalimantan’s Catch-up Attempt

Meanwhile, South Kalimantan has lagged far behind the neighboring provinces of Central and East Kalimantan in the promotion of local infrastructure development under the Kalimantan Corridor of MP3EI, including the railway construction. In April 2012 Gusti Nurpansyah, an executive member of the Banua Care Forum (Forum Peduli Banua, FPB), a social organization aiming at improving social economic conditions in South Kalimantan,14) expressed his hope that South Kalimantan would get actively involved in the implementation of the Kalimantan Corridor, not just stand by and watch. The FPB intended to hold a focus group discussion on the Kalimantan Corridor and to invite national and local NGOs and young leaders to the discussion (Radar Banjarmasin, April 29, 2012).

In the middle of May 2012, Rudy Ariffin, then governor of South Kalimantan, led delegates from the four provinces in Kalimantan to urge the national parliament to increase subsidized fuel quotas since the allocation for Kalimantan was too small. The central government restricted supplies of subsidized fuel, which costs less than half as much as regular fuel, to try to stop a surge in oil prices hurting its budget deficit. Previously, a petition signed by the four Kalimantan governors was sent to the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources, the Upstream Oil and Gas Regulator and Implementing Agency (Badan Pelaksana Kegiatan Usaha Hulu Minyak dan Gas Bumi, BP Migas), and the national parliament, threatening to terminate coal supplies from Kalimantan if subsidized-fuel allocations were not raised. The governors argued that the supply of fuel to the four Kalimantan provinces had to be raised from 7 percent of the total national allocation to 14 percent due to rapid economic development (Rangga 2012b). Rudy Ariffin became the most active participant, as he was the only governor who attended the meeting with members of the energy commission of the national parliament. The other three governors were represented by their deputies. The meeting ended with no decision (Jakarta Post, May 23, 2012).

At the end of May 2012, with support from Governor Rudy Ariffin, the FPB initiated a protest and launched a blockade against coal barges entering the lower Barito River—in retaliation to the lack of fuel oil supply—and demanded a bigger quota of subsidized fuel for the Kalimantan region. Thousands of local residents took part in the blockade of the coal transportation route using motorboats; they stopped at least 20 barges from sailing through.

The blockade affected the entire Barito region, including major coal mines in the territory of Central Kalimantan. The Indonesian Coal Mining Association (APBI) threatened to stop the supply of coal to Java from Central Kalimantan if the blockade at the Barito persisted. The State Electric Company (Perusahaan Listrik Negara) prepared for the worst scenario if Java failed to receive coal supplies from Kalimantan once its entire coal stockpile was consumed. Aside from halting supply, APBI estimated that coal companies would have to bear substantial losses.

Only a few barges could pass through Barito. They were the barges owned by the Hasnur Group, as the owner was the father of Hasnuryadi Sulaiman, one of the FPB executive members, and by PT Adaro Indonesia, a big coal company that had a close relationship with the Hasnur Group. Their barges passed through the Barito before protesters started a blockade (Rangga and Hans 2012; Radar Banjarmasin, May 17, 2012; Tribun News, May 26, 2012; Jurnal Nasional, May 28, 2012). The two companies were probably told the time schedule of the blockade by the FPB.

A similar blockade was raised at the Mahakam River in East Kalimantan, led by the provincial branch of the Indonesian Youth National Committee (Komisi Nasional Pemuda Indonesia). They were inspired by the Barito’s blockade. However, the blockade in the Mahakam quickly fizzled out as Awang Faroek, the governor of East Kalimantan, disapproved of it and warned the protesters that they were committing a criminal offence (Tempo Interaktif, May 29, 2012).

As an emergency response to the blockade at the Barito River, Jero Wacik, then minister of energy and mineral resources, stated that the central government would increase the quotas for the supply of non-subsidized fuel to Kalimantan. Governor Rudy Ariffin responded by asking the blockade organizers to stand down. The blockade was over within a week (Rangga 2012a; Rangga and Hans 2012). With the success of the blockade, Rudy Ariffin was able to show that South Kalimantan was capable of playing a leading role in the negotiations with the central government for the sake of regional development in Kalimantan, just like the neighboring provinces.

Windfall for Governor Narang

The blockade at the Barito brought a windfall to Governor Narang. It showed the political and business circles in Jakarta that the dependence on river transportation in the Barito region would pose a high risk to coal supply to Java as well as to the coal-mining industry in the middle and upper Barito regions in Central Kalimantan if blockades occurred in the lower Barito in the neighboring province. It also demonstrated not only that the coal railway network in Central Kalimantan was vital to economic strategy but also that there was a need to diversify risk.

In July 2012, a declaration of commitment for the construction of a rail track between Murung Raya and Kapuas in Central Kalimantan was signed by state-owned companies, including PT PLN and PT PII, as well as the areas’ major coal-producing private companies such as PT BHP Billiton Indonesia, PT Asmin Koalindo Tuhup, and PT Indika Indonesia Resources. The signing ceremony was held in front of then Indonesian Vice President Boediono and ministers in Palangka Raya (Kompas, July 12, 2012).

Another railway line in Central Kalimantan also became a real possibility. In August 2012, Governor Narang and PT Kereta Api Indonesia (PT KAI), the state-owned railway company, signed an MoU on the construction of an approximately 200 km railway network running north to south in the mid-west part of the province. It would connect the northern district of Gunung Mas to a port in the southwestern district of Seruyan. PT KAI showed its keen interest by agreeing to conduct a feasibility study on soil conditions right away. This rail line would be used for goods and passenger trains. PT KAI stated that the railway would not only improve the local economy and social welfare but also create job opportunities, since at least 1,000–2,000 railway officers were required to operate a railway system (Tempo Interaktif, August 3, 2012).

Narang expressed his long-standing concern that forests in Central Kalimantan had been cut and lost since the 1970s but the results of local development had never been seen, with the people living in poverty. “Conditions of national roads in the province have been always severely damaged because 8-ton capacity trucks carrying 12 to 20 tons of load rumble down the roads daily,” he said. “I feel even if hundreds of billions are spent on the construction of roads, they will always remain damaged and broken. Given this situation, the solution is to build a railway line in Central Kalimantan” (ibid.).

VII Conclusion

The question to be asked is: How effectively planned is the trans-Kalimantan rail project going to be in the midst of the wheeling and dealing taking place at the district, provincial, central, and global levels?

As the case of East Kalimantan shows, local power holders would welcome a railway plan proposed by foreign investors and the central government if the project fitted in with the economic and political agenda of local government leaders. However, as in the case of Central Kalimantan, the central government and foreign investors could face difficulty in securing investment deals if the proposed plan had the potential to undermine the power base of local power holders. In such cases, as represented by Narang, the governor of Central Kalimantan, local political leaders have tried to hold a leading position by portraying themselves as defenders of local communities and the environment in their negotiations with foreign and national players.

It is, however, clear that the local government’s priority is not the concerns of local communities or the environment in Central Kalimantan. The provincial government actually recognized that the rail construction and operations would cause an impact on the environment. Thus, it used the rhetoric of “a less-damaging way of infrastructure development” to persuade local stakeholders to agree to the provincial railway project while using the rhetoric of “defender of local communities and the environment” to oppose the central government’s plan.

Whatever the case may be, the voices of ordinary local residents in the region where the railway projects would be implemented have not been publicly heard in any significant way. A possible reason could be that it has yet to sink in among residents that a coal railway will be built in their area. They might have been listening to the politicians and businesspeople harping on the positive aspects of a new railway system. They might have heard that the infrastructure development would lead to urbanization, with more jobs and economic opportunities as well as a better life for them. They might be expecting foreign companies to pay a large amount of financial compensation for their land.

The railway construction might also bring about some negative effects for local residents and the environment. There might be an influx of immigrant workers from other provinces, and locals might have to compete with them for railway-related job opportunities, which could eventually lead to ethnic tensions. Unplanned rapid urbanization of Kalimantan might lead to social problems, including poverty. Roads and paths might be opened up illegally from the railway line to interior forest areas, making it easier for illegal logging. More coal-mining companies would enter the region, and they could include some that might not be able to fulfill the technical requirements and financial guarantees related to compulsory reclamation and post-mining rehabilitation. Some companies might operate in a forest beyond their licensing area. These issues could escalate if the central and local government authorities failed to supervise the planning of the rail infrastructure as well as control businesses and mining operations in the region.

Hence, the role of local governments is crucial not only in the negotiation process with the central government and foreign investors but also during the construction and operations of the railway. However, general elections and direct elections for local government heads are held once five years, by which time major realignments can take place in national and local politics. In Central Kalimantan, the last gubernatorial election was held in January 2016. Narang was not able to run for re-election since the law limits the governor to two terms of office, and his favorite candidate was not elected as governor. Therefore, the direction for future research will be to seriously consider the impact of highly possible realignments in local politics on the progress of railway construction, and its effects on local residents and the environment. How rapidly the pace of development and projects move in Kalimantan will very much depend on it.

Accepted: February 10, 2016

References

Books and Articles

Algooth Putranto; and Stefanus A. Setiaji. 2012a. Central Borneo Govt Rejects Trans-Borneo Railways Project. Bisnis Indonesia. February 7.

―. 2012b. Central Kalimantan Opposes Trans-Kalimantan Railway. Bisnis Indonesia. February 7.

ASEAN Secretariat. 2012. Table 25 Foreign Direct Investments Net Inflow Intra- and Extra-ASEAN. ASEAN Secretariat. http://www.asean.org/images/pdf/resources/statistics/table25.pdf, accessed August 18, 2012.

―. 2006. Statistics of Foreign Direct Investment in ASEAN: Eighth Edition, 2006. Jakarta: ASEAN Secretariat.

Aspinall, Edward. 2011. Democratization and Ethnic Politics in Indonesia: Nine Theses. Journal of East Asian Studies 11: 289–319.

Aspinall, Edward; and Fealy, Greg, eds. 2003. Local Power and Politics in Indonesia: Decentralisation & Democratisation. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Badan Perencanaan Pembangunan Daerah Provinsi Kalimantan Barat [Regional Development Planning Agency of West Kalimantan Province]. 2010. Meningkatkan koordinasi dan sinergisitas bagi revitalisasi dan percepatan pembangunan wilayah Kalimantan [Intensification of coordination and synergy for revitalization and acceleration of regional development of Kalimantan]. Media Perencanaan [Media Planning] June: 10–14.

Badan Perencanaan Pembangunan Nasional (BAPPENAS) [National Development Planning Agency]. 2013. Peran perkeretaapian: Dalam pembangunan ekonomi berkelanjutan [Role of railways: In sustainable economic development]. Jakarta: BAPPENAS. http://www.slideshare.net/IndonesiaInfrastructure/peran-perkeretaapian-dalam-pembangunan-ekonomi-berkelanjutan, accessed February 15, 2016.

Badan Pusat Statistik. 2001. Penduduk Indonesia: Hasil sensus penduduk tahun 2000 [Population of Indonesia: Results of the 2000 census]. Jakarta: Badan Pusat Statistik.

Bisara, Dion. 2010. Dubai Group Ready to Start $1B Rail Project in Indonesia. Jakarta Globe. March 25.

Casson, Anne. 2006. Decentralisation, Forests and Estate Crops in Kutai Barat District, East Kalimantan. In State, Communities and Forests in Contemporary Borneo, edited by Fadzilah Majid Cooke, pp. 65–86. Canberra: ANU E Press. http://press.anu.edu.au/apem/borneo/html/ch04s02.html, accessed February 15, 2016.

Central Kalimantan Provincial Government. 2009. Information Memorandum: Proposed Central Kalimantan Coal Railway from Puruk Cahu to Bangkuang (Draft). Palangka Raya: Central Kalimantan Provincial Government.

Choi, Nankyung. 2011. Local Politics in Indonesia: Pathway to Power. London and New York: Routledge.

Coordinating Ministry of Economic Affairs. 2011a. Masterplan: Acceleration and Expansion of Indonesia Economic Development 2011–2025. Jakarta: Coordinating Ministry of Economic Affairs. http://www.depkeu.go.id/ind/others/bakohumas/bakohumaskemenko/PDFCompleteToPrint(24Mei).pdf, accessed December 14, 2012.

―. 2011b. Kunjungan kerja Menko Perekonomian M. Hatta Rajasa ke Rusia [Work visit of Coordinating Minister for the Economy M. Hatta Rajasa to Russia]. Berita Ekonomi. June 22. http://ekon.gridol.net/1044/berita-ekonomi/kerjasama-luar-negri/kunjungan-kerja-menko-perekonomian-m-hatta-rajasa-ke-rusia/, accessed December 16, 2012.

Daulay, Bukin; Suganal, Chem E.; and Soelistijo, Ukar W. 2007. Coal Gasification in Indonesia. Jakarta: Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources of Indonesia.

Davidson, Jamie S.; and Henley, David, eds. 2007. The Revival of Tradition in Indonesian Politics: The Deployment of Adat from Colonialism to Indigenism. London: Routledge.

Embassy of the Russian Federation in the Republic of Indonesia. 2012. On the Signing of the Memorandum of Understanding on the Railway Construction in the East Kalimantan Province (Indonesia). Press release, Embassy of the Russian Federation in the Republic of Indonesia. http://www.indonesia.mid.ru/press/337_e.html, accessed November 8, 2012.

Erb, Maribeth; and Priyambudi Sulistiyanto, eds. 2009. Deepening Democracy in Indonesia? Direct Elections for Local Leaders (Pilkada). Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Europa Publications, ed. 2003. The Far East and Australasia 2003. London: Routledge.

Ewart, Donald L.; and Vaughn, Robert. 2009. Indonesian Coal. World Coal Asia Special (May).

Gedicks, Al. 2001. Resource Rebels: Native Challenges to Mining and Oil Corporations. Boston: South End Press.

Hadiz, Vedi R. 2010. Localising Power in Post-Authoritarian Indonesia: A Southeast Asia Perspective. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Hanan Nugroho. 2006. Momentum for Improving Coal Transportation Infrastructure. Petrominer 6: 15–17.

Hanim Hamzah; and Afriyan Rachmad. 2011. New Land Acquisition Bill. ZICO Law. http://www.zicolaw.com/new-land-acquisition-bill-3/, accessed December 14, 2012.

Harrington, Andrew; and Trivett, Matthew. 2012. Indonesian Coal Review: The Short Term Option. Perth: Patersons Securities.

Imam Mudzakir; and Ester Nuky. 2011. Bakrie and China Pass Rp21 Trillion-Worth Railway Tender Pre-qualification. Investor Daily. December 1.

Indoanalisis. 2012. Buku data: Kinerja industri Indonesia 2012 [Data book: Indonesian industry performance]. Jakarta: Indoanalisis.

Indonesian Ministry of State Owned Enterprises. 2002. PT KAI akan tangani perawatan trans Borneo [PT KAI will sign to care trans Borneo]. Berita. July 1. http://www.bumn.go.id/22673/publikasi/berita/pt-kai-akan-tangani-perawatan-trans-borneo/, accessed December 22, 2012.

Indra Pradana Singawinata; and Emil Dardak. 2009. Decentralization and Local Development in Indonesia: A Case Study of Mining Transnational Corporation. Köln: LAP Lambert Academic Publishing.

Institute of Energy Economics Japan (IEEJ). 2002. Preliminary Feasibility Study on Railway Coal Transportation in Kalimantan, Indonesia. Tokyo: IEEJ.

Jaringan Advokasi Tambang (JATAM). 2010. Deadly Coal: Coal Extraction & Borneo Dark Generation. Jakarta: JATAM.

Kementerian Energi dan Sumber Daya Mineral [Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources of Indonesia]. 2012. Statistik batubara 2012 [Statistics of coal 2012]. Jakarta: Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources.

Kementerian Pekerjaan Umum dan Perumahan Rakyat, Republik Indonesia [Ministry of Public Works and Public Housing, Republic of Indonesia]. 2012. Peta jaringan jalan nasional provinsi Kalimantan Tengah [National road network in the province of Central Kalimantan]. http://www.pu.go.id/uploads/services/service20120427175211.pdf, accessed February 16, 2016.

Khong, Cho O. 1986. The Politics of Oil in Indonesia: Foreign Company-Host Government Relations. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

―. 1980. Foreign Company-Host Government Relations: A Study of the Indonesian Petroleum Industry. Development Policy Review A13(2): 49–75.

Kimura, Ehito. 2012. Political Change and Territoriality in Indonesia: Provincial Proliferation. London and New York: Routledge.

Mietzner, Marcus. 2010. Indonesia’s Direct Elections: Empowering the Electorate or Entrenching the New Order Oligarchy? In Soeharto’s New Order and Its Legacy: Essays in Honour of Harold Crouch, edited by Edward Aspinall and Greg Fealy, pp. 173–190. Canberra. ANU E Press.

Morishita, Akiko. 2008. Contesting Power in Indonesia’s Resource-Rich Regions in the Era of Decentralization: New Strategy for Central Control over the Regions. Indonesia 86: 81–107.

Noorjani. 2010. Teras-Diran masih unggul di pilkada Kalteng [Teras-Diran still ahead in the regional head election of Central Kalimantan]. Banjarmasin Post. June 12.

NordNordWest/Wikipedia. 2011. Location map of Kalimantan, Indonesia, 5 January. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Indonesia_Kalimantan_location_map.svg, accessed February 16, 2016.

OECD. 2012. OECD Reviews of Regulatory Reform: Indonesia 2012: Strengthening Co-ordination and Connecting Markets. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Okamoto, Masaaki 岡本正明. 2007. Jichitai sinsetsu undo to seinen no poriteikusu: Gorontaro shinshu setsuritsu undo (1998 nen–2000 nen) ni shoten o atete 自治体新設運動と青年のポリティクス――ゴロンタロ新州設立運動(1998年~2000年)に焦点を当てて [The politics of youth and autonomy: The case of Gorontalo Province (1998–2000)]. Tonan Ajia Kenkyu 東南アジア研究 [Southeast Asian Studies] 45(1): 137–158.

Priyambudi Sulistiyanto; and Erb, Maribeth. 2009. Indonesia and the Quest for Democracy. In Deepening Democracy in Indonesia? Direct Elections for Local Leaders (Pilkada), edited by Maribeth Erb and Priyambudi Sulistiyanto, pp. 1–37. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Rangga D. Fadillah. 2012a. Kalimantan Leaders to End Coal Blockade. Jakarta Post. May 31.

―. 2012b. Govt Warns Renegade Governors. Jakarta Post. May 10.

Rangga D. Fadillah; and Hans David Tampubolon. 2012. Govt Caves In to Coal Blackmail. Jakarta Post. May 29.

SALVA Report. 2012. Indonesia: Coal, Power, Infrastructure. Brisbane: SALVA Report.

Schulte Nordholt, Henk; and van Klinken, Gerry, eds. 2007. Renegotiating Boundaries: Local Politics in Post-Soeharto Indonesia. Leiden: KITLV Press.

Strategic Asia. 2012. PPP (Public Private Partnerships) in Indonesia: Opportunities from the Economic Master Plan, Prepared by Strategic Asia for the UK Foreign Commonwealth Office. http://www.strategic-asia.com/pdf/PPP%20(Public-Private%20Partnerships)%20in%20Indonesia%20Paper.pdf, accessed July 4, 2015.

Surya Sriyanti. 2011. Masyarakat adat Dayak tolak pembangunan rel KA di Kalimantan [Dayak indigenous peoples reject railway construction in Kalimantan]. Media Indonesia. August 4.

Thee, Kian W. 2006. Policies for Private Sector Development in Indonesia. Asian Development Bank Discussion Paper No. 46. March. http://www.adbi.org/files/2006.03.d46.private.sector.dev.ind.pdf, accessed December 22, 2012.

Trimex. 2010. Transportation Minister Numberi Visits MEC Development in East Kalimantan. August 30. http://www.trimexgroup.com/p_201008_transportation.asp, accessed September 4, 2012.

Wahyu Prasetyawan. 2006. The Unfinished Privatization of Semen Padang: The Structure of the Political Economy in Post-Suharto Indonesia. Indonesia 81: 51–70.

―. 2005. Government and Multinationals: Conflict over Economic Resources in East Kalimantan, 1998–2003. Southeast Asian Studies 43(2): 161–190.

Wanly, Thomas. 2012. Kerusakan lingkungan akibat pertambangan dan perkebunan di Kalteng [Environmental damage resulting from mining and plantation in Central Kalimantan]. Sidak Post. September 22.

World Bank. 2008. Spending for Development: Making the Most of Indonesia’s New Opportunities. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Newspapers

China Railway Group Wins Tender to Build Railway in Central Kalimantan. Antara News. October 13, 2014.

Bupati Barut-Kubar tanda tangani Mou infrastruktur [District heads of North Barito and West Kutai sign MoU on infrastructure]. Antara News. March 1, 2012.

Presiden bahas pembangunan rel kereta di Kalteng [President discusses railway construction in Central Kalimantan]. Antara News. December 16, 2011.

Kalteng ingin wujudkan jalur rel kereta api [Central Kalimantan wishes to realize railway line]. Berita Daerah. October 12, 2009.

S. Kalimantan Governor Calls Quota Unfair. Jakarta Post. May 23, 2012.

PII to Guarantee $2.3B Railway Project in C. Kalimantan. Jakarta Post. December 1, 2011.

Issue: Green Activists Reject Kalimantan Railway. Jakarta Post. August 7, 2011.

C. Kalimantan Governor Rejects Russian Railway Plan. Jakarta Post. August 4, 2011.

Russia to Invest $2.5B for Railway Construction in Kalimantan. Jakarta Post. August 1, 2011.

Kalimantan to Have Railway by 2005. Jakarta Post. April 21, 1999.

Pengiriman batubara lintas Barito terhenti [Coal shipment across Barito stopped]. Jurnal Nasional. May 28, 2012.

Pemprov selalu berprasangka negatif [Provincial government always has negative bias]. Kalteng Pos. March 15, 2012.

Ditandatangani, deklarasi komitmen KA batu bara [Signed declaration of commitment to coal train]. Kompas. July 12, 2012.

Rel KA dibangun di Kalimantan [Railway construction in Kalimantan]. Kompas. February 8, 2012.

Kunjungan ke China: Jusuf Kalla disambut upacara kenegaraan [Visit to China: Jusuf Kalla welcomed at state ceremony]. Kompas. June 8, 2007.

Itochu bangun jalur KA di Kalteng [Itochu constructs railway in Central Kalimantan]. Kompas. April 16, 2007.

Rusia bangun rel kereta api di Kalimantan [Russia constructs railway in Kalimantan]. Media Indonesia. October 27, 2011.

Kalsel menggugat royalti [South Kalimantan claims royalties]. Media Kalimantan. February 16, 2012.

Work on Trans-Borneo Rail Line Begins in November. New Straits Times. April 18, 2000.

Tokoh blokir sungai berdatangan [Figure of river blockade coming]. Radar Banjarmasin. May 17, 2012.

Jangan jadi penonton [Don’t become a spectator]. Radar Banjarmasin. April 29, 2012.

Rel batubara masih mimpi! [Coal railway still a dream!]. Radar Banjarmasin. July 28, 2006.

Sebentar lagi, Kalimantan bakal punya kereta api [Soon Kalimantan will have train]. Tempo Interaktif. August 3, 2012.

Gubernur Awang tolak aksi blokade jalur batu bara [Governor Awang rejects coal lane blockades]. Tempo Interaktif. May 29, 2012.

Interconnecting Train Project in Kalimantan Approved. Tempo Interaktif. April 16, 2012.

Menteri Hatta minta kompromi soal rel kereta batubara [Minister Hatta asks for compromise on issue of coal railway]. Tempo Interaktif. August 8, 2011.

Pemerintah cari investor untuk trans Borneo [Government seeks investor for trans-Borneo]. Tempo Interaktif. August 26, 2004.

Gubernur Kalsel ikut blokit tongkang batubara [Governor of South Kalimantan joins coal barge blockade]. Tribun News. May 26, 2012.

Others

Agustin Teras Narang Center. 2012. MoU Barut dan Kubar melanggar etika pemerintahan [MoU by North Barito and West Kutai violates ethics of government]. March 7. http://www.atn-center.org/read.asp?id_news=2084&menu=Berita, accessed November 14, 2012.

Railway Technology. 2010. Indonesia Private Railway Freight Corridor, Indonesia. http://www.railway-technology.com/projects/indonesiaprivaterail/, accessed September 4, 2012.

1) According to Decentralization Law No. 22/1999, obligatory sectors for the local government include health, education, public works, environment, communication, transport, agriculture, industry and trade, capital investment, land, cooperatives, manpower, and infrastructure services. Provincial governments are required to coordinate local governments and perform functions that affect more than one local government (World Bank 2008, 113).

2) IUJP, IMB, and environmental permits are under the purview of Regulation of the Minister of Energy and Mineral Resources No. 28/2009; Government Regulation No. 32/2010; and Government Regulation No. 27/2012 respectively.

3) It usually takes about 8 to 10 hours to drive from Pontianak to Kuching.

4) Indonesia’s investment climate deteriorated after the Asian financial crisis of 1997–98. In 1997 the inflow of foreign direct investment (FDI) was US$4.7 billion, but the following year Indonesia experienced a greater outflow than inflow, posting a negative of US$356 million. The country kept registering a negative inflow of FDI from 1998 to 2001 and in 2003 (ASEAN Secretariat 2006, 13). Frequent labor disputes and rapid wage increases also caused the relocation of foreign firms to other Southeast Asian countries such as Vietnam (Thee 2006).

5) The Government Regulation also defined the authority of provincial governments in 20 sectors, including agriculture, marine, mining and energy, forestry and plantation, and transportation.

6) See Chapter 5 of Law No. 23/2007.

7) Agustin Teras Narang was born to a local Dayak family in 1955. Dayak is a loose generic term for the indigenous communities of Kalimantan. The Narang family is one of the influential families among local Dayaks, especially in the central part of Central Kalimantan. Narang’s grandfather was a traditional customary leader and also a Christian church leader in the Kapuas region (interview with a local Dayak historian, April 2005). His father was a local businessman, and his elder brother is a local politician who is now the provincial chairman of the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P). Agustin Teras Narang himself was a lawyer and served as a parliament member of PDI-P before being elected as governor. He won the elections for governor of Central Kalimantan in 2005 and in 2010.

8) A Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) is generally a statement of intent and does not imply any legally binding obligation or official agreement.

9) Soon after Yudhoyono took over as president in 2004, the central government began to streamline regulatory laws and the system for PPP schemes for infrastructure projects. PPP schemes were implemented since the 1980s but only for specific sectors, such as electricity and toll roads. Following the Asian economic crisis in 1997, the central government embarked on the implementation of a legal and institutional framework that could serve as a basis for a greater degree of private participation in the form of PPPs and as part of the reform process for revitalizing the Indonesian economy. However, it made little progress until Yudhoyono took the presidency (OECD 2012, 184).