Advance Publication

Accepted: August 16, 2024

Published online: November 10, 2025

Contents>> Vol. 14, No. 3

Women in Thai-Lao Manuscript Culture: Alternative Worship of Text(iles) in Support of Monkhood

Saowakon Sukrak* and Silpsupa Jaengsawang**

*Faculty of Education, Rajabhat Maha Sarakham University, 80 Nakhon Sawan Road, Talat Sub-district, Mueang District, Mahasarakham Province, 44000 Thailand

e-mail: saowakon[at]rmu.ac.th

![]() https://orcid.org/0009-0000-8881-1411

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-8881-1411

**Dipartimento di Studi sull’Asia e sull’Africa Mediterranea, Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia, Campazzo S. Sebastian, 1686, 30123 Venezia VE, Italy

Corresponding author’s e-mail: silpsupa.jaengsawang[at]unive.it

![]() https://orcid.org/0009-0006-3284-3936

https://orcid.org/0009-0006-3284-3936

DOI: 10.20495/seas.25007

Browse “Advance online publication” version

Possessing inferior religious status to males, who could be ordained as monks, females played a comparatively minor role in Theravāda Buddhism. Females were generally allowed to be involved in creating items to be donated to the Sangha, except for writing religious manuscripts, which required literacy in the Dhamma script; that skill lay with monks and novices, since the script was taught at monasteries. To compensate for their inability to obtain monkhood status, women wove textiles for wrapping religious books or donated their hair for binding palm-leaf manuscripts. Cloth-weaving skills compensated for their lack of literacy in the Dhamma script, while the donation of hair compensated for their lack of masculinity or monkhood. Women could also invest in tools, sponsorship, and financial support for commissioning religious manuscripts. Thus, although they were not allowed to be directly involved in the production of religious manuscripts, they were able to engage in ancillary activities.

Keywords: women, Buddhism, manuscript culture, textiles, hair, Thai-Lao

1 Introduction: Women in Theravāda Buddhism1)

The earliest reference to the emergence of human beings and male-female gender in Theravāda Buddhism is found in the Aggaññasutta, a sutta2) in the Dīghanikāya division of the Suttanta Piṭaka3) in the Theravāda Buddhist canon (Tipiṭaka),4) which is characterized as a myth of the universe.5) In the Aggaññasutta, asexual luminous beings descended from the Ābhassarā level6) of the Form-Sphere (Rūpabhava)7) to the human world and ate soil, which they found pleasant tasting. Having consumed the soil, the Ābhassarabrahma beings lost their radiance and were unable to ascend back to their Form-Sphere home. Their asexual bodies physically turned into male and female genders, creating the very first generation of worldly human beings.

The myth of early human generations mentioned in the Aggaññasutta theoretically claims gender indiscrimination in Theravāda Buddhism. According to this, our first ancestors descended from a higher level and were genderless until they consumed the tasty soil; the implication is that sexual intercourse was irrelevant to the origin of human beings, and that no human beings had disadvantageous sexual features that prevented them from attaining enlightenment or nibbāna. During and after the Buddha’s lifetime, as evidenced in canonical as well as non-canonical sources, women played various roles in Buddhism and supported the religion in accordance with their sociocultural status. In early Buddhism, females were not prohibited from being ordained. The first Buddhist nun was Pajāpatī, the aunt of Gotama Buddha, who with the help of Venerable Ānanda successfully requested permission for women to be ordained.8) Below are some examples of female monks mentioned in canonical texts and other religious sources.

After the Buddha’s passing (parinibbāna), there were conflicts between Venerable Kassapa and Buddhist nuns. Venerable Kassapa disagreed with admitting women to the order, and the nuns—due to Venerable Kassapa’s Brahman rather than Buddhist background—doubted his ability to understand the Buddhist Dhamma. Venerable Ānanda asked Venerable Kassapa for forgiveness on the nuns’ behalf (Kabilsingh 1998, 30–31). In Mahāvacchagotasutta (Paribbājakavagga, Majjhimapaṇṇāsaka, Majjhima Nikāya, Suttanta Piṭaka), five hundred female monks attained enlightenment; and in Therīgathā (Khuddaka Nikāya, Suttanta Piṭaka), thirty female monks gained enlightenment (Anālayo 2009, 137). Through his lifetime Gotama Buddha encountered several prominent Buddhist women, and he praised 13 female monks whom he recognized as most outstanding.9) Among these, Kundalakesī Theri10) was praised for her sudden attainment of Arahantship (freedom from obsessions), showing the ability of women to attain enlightenment.

Originating in India, where society—like in other parts of Asia—is predominantly patriarchal, the Buddhist religion is observed and practiced with rules that treat males and females differently. In order to prevent sensual desire among monks and distractions caused by sexual intimacy, monastic prohibitions were instituted by the Buddha to keep monks away from women. At some point, this brought about gender inequality or gender discrimination. In the Theravāda Buddhist canon there are sutta that regard women as a distraction preventing men from attaining nibbāna, as representing danger, and as being unable to occupy certain positions: Cātumasutta (in Bhikkhuvagga, Majjhimapaṇṇāsaka, Majjhima Nikāya, Suttanta Piṭaka) and Bhayasutta (in Bālavagga, Paṭhamapaṇṇāsaka, Tikanipāta, Aṅguttara Nikāya, Suttanta Piṭaka),11) Sappasutta (in Dīghacārikavagga, Pañcamapaññāsaka, Pañcakanipāta, Aṅguttara Nikāya, Suttanta Piṭaka),12) and Bahudhātukasutta (Pāli discourse) (in Anupadavagga, Uparipaṇṇāsaka, Majjhima Nikāya, Suttanta Piṭaka).13)

Hinduism considers menstruation to be a sign of impurity and contamination. With Thailand and Laos having been influenced by Hinduism, many Buddhist or sacred places there are out of bounds for menstruating women; it is believed that this period of impurity can weaken spiritual power. In addition, female visitors in general are not allowed to enter certain spaces, such as stages for preaching monks, even when there are no monks or laymen nearby. The exclusion of women from such spaces is a strategy to shield monks from laywomen; laymen, on the other hand, can freely visit and enter any place. Such regulations lead to gender discrimination and to women being relegated to an inferior social status.

Due to the Buddhahood being limited to males, Bodhisattas in jātaka stories are generally male. In the last ten great births of Gotama Buddha, women are supportive, creatively resourceful, and active heroines in their own right. The few negative portrayals involve minor characters, and they do little to counteract the wealth of positive examples (Appleton and Shaw 2015, 21). A rare case of a female Bodhisatta’s birth in Buddhist texts is found in Padīpadāna Jātaka in the Paññāsa Jātaka, a set of fifty apocryphal jātakas14) attributed to monks from Chiang Mai (Northern Thailand) during 1457–1657 CE. The story is set during the period of Dīpaṅkara Buddha,15) whose sister was a princess. In one of her previous rebirths, she was born as a man and committed Aparāpariyavedanīyakamma (a kind of sin whose effects recur in one’s subsequent lives) with a daughter of his younger sister, causing his new rebirth as a female in the period of Dīpaṅkara Buddha. The princess offered lamp oil to the Buddha—her brother—making a wish to become a future Buddha named Siddhattha, whose Buddhist era is in the present. This jātaka story shows the potential of females to reach nibbāna and eventually become a Buddha with their sufficiently accumulated merit.

Theoretically, in the Theravāda canonical source (Tipiṭaka), women and men emerged from shared celestial ancestors; but in reality females had an inferior social status and played relatively minor roles in religious practices and norms. This gender inequality had an influence on manuscript cultures.16) This paper aims to investigate the roles of women in manuscript cultures in order to answer the questions of how women, in an effort to compensate for their inferiority in religious practices, found ways to participate in the production of religious manuscripts (all—if not most—of whose scribes are male); the meaning of the alternative objects that women donated to monasteries to compensate for their exclusion from monkhood opportunities; to what extent the writing of religious manuscripts and the donation of objects to support religious manuscript production are different; and whether the alternative objects offered by women can replace the writing of religious manuscripts. The paper will discuss general information on women in Thai-Lao Theravāda Buddhist society and in manuscript cultures, followed by the donation of hair, wrapping cloth, and other objects for manuscript production. The paper will end with a comparison between texts and textiles.

2 Women in Thai-Lao Theravāda Buddhist Society: Social and Cultural Context

There are four possible assemblies of Buddhists (buddhaparisā): monks (bhikkhu), Buddhist nuns (bhikkhuṇī), laymen (upāsaka), and laywomen (upāsikā). Except for Buddhist nuns, Thailand and Laos have the three remaining assemblies. Despite the existence of Buddhist nuns in the Buddha’s lifetime, these days there are next to none—probably because there are barely any left to organize ordination ceremonies.17) Buddhist nuns observe a set of 311 precepts known as Gurudhamma, more than the 227 precepts for monks. Women ordained in Thailand and Laos are not Buddhist nuns but female novices (sikkhamānā or sāmaṇerī)18) who observe only six precepts and undergo a probationary course of two years before receiving higher ordination (Payutto 2015, 354). The ordination ceremony for a nun requires at least five nuns (Kabilsingh 1998, 14) to be present in addition to a number of monks. But since there are no longer any legitimately ordained nuns within the Theravāda tradition, the ordination of a nun is simply not possible.

Unlike the current Sangha rules, before bhikkhuṇī came from India in the third century BCE, male monks were allowed to ordain women (Li 2000, 183, cited in Tomalin 2006, 387). Only three countries were home to bhikkhuṇī—Sri Lanka, India, and Burma—though bhikkhuṇī had disappeared from Theravāda Buddhism by the eleventh century CE. However, the bhikkhuṇī order of the Mahāyāna tradition still exists to this day. An estimated eight hundred Sri Lankan nuns have received bhikkhuṇī ordination, setting an important precedent for nuns in other Theravāda societies (Tomalin 2006, 386; Tsomo 2010, 90, 100). Sri Lankan and Chinese bhikkhuṇī share the same lineage, because a group of bhikkhuṇī from Sri Lanka introduced bhikkhuṇī ordination in China in 433 CE (Kabilsingh 1991, 31; Wijayasundara 2000, 82, cited in Tomalin 2006, 387).

Compared to Lao white-robed laywomen (maekhao), Thai white-robed laywomen (maechi) are better educated and are becoming more numerous, visible, and influential in society. However, white-robed laywomen in Laos seem to be slightly better off. Maekhao have an identification card that establishes them as Buddhist nuns and gives them certain privileges. Maechi, however, are not given such a card, which means they pay full price for things like public transport but, like monks, are not allowed to vote (Seeger 2006, 173; Tsomo 2010, 89, 103).

In Laos, maekhao and monks are interdependent and cooperate in a friendly manner with each other. Monks share extra food and donated commodities with maekhao, who in turn assist monks with goods and services. This is similar to the interactions between monks and Buddhist women in Myanmar. The women cook for monks, and monks express their gratitude to the laity by teaching them, which shows a female presence in temples (Tsomo 2010, 88, 95; Saruya 2022, 11). Lao maekhao believe in accumulating merit by means of serving and assisting monks, through which they expect to reach nibbāna. Despite their shaved heads, they are considered pious women rather than full members of the Sangha order and are relegated to a lower position than monks. In spite of their lack of material goods and shelter, maekhao are quite satisfied with their lot and do not aspire to elevate their status. Not all Theravāda nuns in Laos are willing to formally receive the 311 bhikkhuṇī precepts, especially those over a certain age for whom the additional precepts might pose a hardship (Tsomo 2010, 102). Maekhao live in their comfort zone, and becoming a maekhao is usually not a consequence of a miserable personal life or career failure.

By contrast, maechi in Thailand have made attempts to increase gender equality in the Sangha order. There is no evidence to suggest that there were ever Theravāda nuns in Thai society. The first attempt to establish a bhikkhuṇī order in Thailand was undertaken in 1927 by the former government official and engaged lay-Buddhist Narin Prasit. He had his two daughters ordained as sāmaṇerī, an act that was later criticized heavily by both the government and the clergy. A monk suspected of having ordained the two sisters was asked by his superior to leave the monkhood (Seeger 2006, 159). As a result of this incident, the 1928 Sangha Act prohibited monks from ordaining women as bhikkhuṇī, sāmaṇerī, and sikkhamānā (novice trainees). This regulation, however, contradicts the Thai constitution, which guarantees equality to men and women and the freedom to practice any religion (Seeger 2006, 160; Litalien 2018, 573). Chatsumarn Kabilsingh was ordained as a bhikkhuṇī in Sri Lanka in 2003 and is now known as Dhammananda. Since 2003 a further twenty or so women have been ordained as sāmaṇerī or novices. Kabilsingh’s ordination was supported by Buddhists in Sri Lanka and a global network of supporters of a certain bhikkhuṇī order in Theravāda Buddhism (Tomalin 2006, 392; Litalien 2018, 595). In 2013 the very first full Theravāda bhikkhuṇī ordination in the history of the Kingdom of Thailand occurred in Phayao Province, followed by the second and third in 2014 and 2015 (Litalien 2018, 596). There are communities of Mahāyāna bhikkhuṇī in Thailand, but maechi have a negative reputation—for instance, they are believed to have been unsuccessful in love, homeless, or deprived of alternative opportunities (Seeger 2006, 173). In short, there is still gender inequality in Thailand, which spills over into the Thai Sangha. The latter’s structure resembles that of the state bureaucracy, which is dominated by males. On the other hand, maechi and bhikkhuṇī are able to provide services to the community, as they are regarded as being outside of the Sangha (Litalien 2018, 589).

Southeast Asia is dominated by a patriarchal culture, with men generally leading organizations and societies in a direction that benefits themselves more than women. Even though Buddhist women continue with their devotions and alms-offering to monks, in most Asian Buddhist societies religious and social institutions reflect a tacit assumption of the moral superiority of males, discriminatory or patronizing attitudes, and the exclusion of women (Tsomo 2010, 87–89). Women are barred from access to institutional avenues of social mobility (Seeger 2006, 171). The Thai bhikkhuṇī movement is a local strategy to address and bring attention to gender inequality by religious Buddhist feminists in Thailand. It is the result of attempts to establish social discourses that consider religious and cultural factors in parallel with economic development (Tomalin 2006, 386; Litalien 2018, 578).

In Myanmar, however, in the past Buddhist women were able to gain access to meditation and study, and an increasing number even taught profound Dhamma topics such as Abhidhamma. Laywomen could even participate in padaythabin processions, which were part of the Pongyibyan festival.19) During the colonial period laywomen created a demand for learning Buddhist doctrines, while monks created the supply, resulting in an increased transmission of Buddhist texts. Textual transmission was enhanced by the introduction of new printing technologies in Myanmar in the 1800s. Studies of Myanmar history show that educated nuns during the reign of King Mindong (1853–78) taught the ladies of the court. Some lay girls may have received a basic education in monasteries up to a certain age. During the colonial era, female education in general became more acceptable (Saruya 2022, 1–3).

Women in Thailand and Laos are expected to accept or comply with certain prohibitions and even taboos. Those who fail to follow social norms are cautioned or socially punished. Laywomen are expected to behave a certain way in terms of walking, speaking, prostrating, looking at a monk, etc. They also have to maintain a respectful distance from monks and dress appropriately. Hence, women are limited by rules and norms when interacting with monks and novices; they are subject to gender and even social-hierarchical discrimination. This is the intrinsic inferiority of women reinforced within the structure of everyday public Buddhist practices and customs (Tomalin 2006, 389).

Certain areas or places are reserved for monks and out of bounds for laywomen. In the ordination hall (sim) of monasteries, for instance, there is an elevated stage set against an inner wall to seat chanting monks. Book cabinets, seating cushions, and other ritual utensils are placed there. Laywomen are not allowed to enter the stage even when there are no monks around:

In Theravāda monasteries, nuns, even those who have been ordained for decades, typically sit on a mat on the floor, while monks, even those who have just been ordained, sit on a raised platform above them. The seating arrangement of nuns below or behind the monks is symbolic of the subordinate position nuns hold in the religious hierarchy, a position that has rarely been questioned. (Tsomo 2010, 91)20)

This norm is not intended simply to maintain a distance between monks/novices and laywomen but to discriminate against females. The rule prohibiting females from entering monk’s abodes (kuṭi), however, makes sense and is not surprising—comparable to dormitory regulations in schools and certain mansions—for preventing monks and laywomen from getting close.

Aside from certain areas that females cannot enter under any circumstances, there are some religious places—usually not in Northern Thailand—where laywomen may be permitted depending upon their physical condition. For instance, only menstruating women are prohibited from entering certain areas in Buddha relic pagodas since it is believed that their impurity may contaminate the sacred power of the relics. In Northern Thailand several temples do not allow women at all:

Many temples in Thailand, seen particularly often in the north, do not allow women to circumambulate the stupas. The monks usually explain that the relics of the Buddha are placed in the centre of the stupas at the time they built it. If women are allowed to circumambulate the stupas, they would be walking at the level higher than the relics and hence might desacralize them. (Kabilsingh 1998, 46–47)

Katherine Bowie (2011, cited in Chladek 2017, 130–131) notes that Northern Thai people forbid women from entering areas of temples that hold sacred relics and argues that this practice is uniquely part of northern Buddhism and cultural practice. Kabilsingh (1998) explains that many Hindu practices are accepted under the name of Buddhism. During the Ayutthaya period Buddhist monks and magic masters prohibited women from touching or walking across consecrated items in order to maintain the items’ magical power (women were considered impure because they menstruated).

In addition to the aforementioned prohibitions for women regarding certain areas of a temple, the maintenance of an appropriate distance between monks/novices and women is also a crucial concern in Buddhism. The distance must be such that neither can reach out their arms to the other, let alone touch. Meetings between monks and laywomen must be held within sight of other people. In the case of indoor visits, a monk and a laywoman may not meet each other alone; there must be at least one other male present. Laywomen meeting a monk have to wear outfits that cover their upper bodies and reach at least below their knees. It is believed that such regulations can prevent sexual affairs and thus protect the Sangha community from scandals.

In order to conform with the rules for associating with monks, laywomen in Luang Prabang always wear a sheet of cloth known as pha biang (Lao: ຜ້າບ່ຽງ) diagonally across their chests to keep the collar close to the neck and the upper part of their bodies invisible when prostrating on the ground. The cloth also functions as a small carpet when there is a group of ritual participants. In an ordination ceremony that Silpsupa Jaengsawang joined in 2017 at the monastery of Vat Manorom, female participants placed their pha biang together on the floor of the ordination hall, welcoming senior and newly ordained monks to walk by (see Fig. 1). Outfits with a pha biang are standard dress for laywomen, but no pha biang is required for laymen. This implies that sexual affairs are dependent upon females’ dressing habits—or are even the responsibility of females—rather than the monks’ self-discipline.

Fig. 1 Laywomen’s Pha Biang Placed on the Floor to Welcome Monks at an Ordination Ceremony (photo by Silpsupa Jaengsawang, March 18, 2017)

Similarly, when a female donor offers gifts to a monk, a sheet of cloth is placed between the donor and recipient. The laywoman sets the offerings on the cloth and pulls back her hands; the monk takes the gifts from the cloth and gives his blessings. Thus, offerings are not made hand to hand; monks and laywomen cannot hand things directly to each other, so as to avoid the unintentional touching of hands. Laymen, however, can simply hand objects directly to monks and novices.

The Dhamma script, used for writing manuscripts, was taught only to monks and novices in monasteries; females were implicitly excluded from gaining this knowledge. In order to compensate for this lack, laywomen found ways to participate in the production and donation of religious manuscripts with the expectation of gaining similar merit to those who were literate in the Dhamma script. This matter is discussed further below.

3 Women in Thai-Lao Manuscript Cultures

Like other ways of making merit, copying and donating religious manuscripts were believed to bring great merit to donors and scribes. The writing of manuscripts required a huge effort, since palm leaves—the earliest and most durable form of writing support—needed a great deal of preparation. In addition, inscribing texts in a palm-leaf manuscript took knowledge, time, and energy. Although mulberry paper and industrial paper replaced palm leaves in some areas, the task of writing or copying texts in a manuscript was still a major undertaking. In order to gain merit, which was incalculable yet beneficial to ensure a better rebirth, people were willing to invest their time and energy on this task. Hence, manuscripts mostly contain religious texts because the investment of time, energy, and money is made with the expectation of magnificent merit and a better rebirth. However, as mentioned above, the Dhamma script was the only tool for textual transmission.

Silpsupa made two research trips to Laos, in February–March 2017 and August–September 2022. She visited both Luang Prabang, the ancient capital, and Vientiane, the current capital. In Luang Prabang, since most monasteries are walking distance from—or even adjacent to—one another within the villages, local people are profoundly engaged in Buddhism and participate enthusiastically in annual religious ceremonies as well as regular Holy Days. Women in Luang Prabang are interested in Buddhist studies. Some of them are self-taught in Buddhist knowledge and prayers; they copy religious texts for Buddhist ceremonies—in the Lao rather than Dhamma script—and pray on their own. Silpsupa even interviewed a laywoman who was a ritual expert leading lay participants to pray in Pāli at a Buddhist event (Bunyong; mentioned below). Women’s basic education is provided by the government. Most of the laywomen engaged in Buddhist religious ceremonies are of retirement age. They have enough free time, without the responsibility of taking care of children and grandchildren who are adults or working in different districts. Laywomen have networks that allow them to actively participate and collaborate in Buddhist ceremonies. Silpsupa found a few nuns or maekhao who simply attended religious ceremonies as participants, while laywomen connected with both local laypeople and monks. It seemed that certain laywomen communicated with local laypeople to announce upcoming Buddhist events, gather lay participants, and lead preparations, while monks communicated with other monks and novices to organize the events. In Luang Prabang, leaders who take care of secular practices are women, while those who take care of monastic practices are monks, except for some tasks that traditionally belong to laymen, such as preparation for monkhood ordination.

Unlike Luang Prabang, in Vientiane monasteries are located far from one another. During Silpsupa’s visit to Vientiane, participants in Buddhist ceremonies came from different provinces or communities, and not all of them knew one another. Laywomen did not appear to play an important role in religious events, unlike the case of Luang Prabang. Monks seemed to play a crucial role. For instance, Silpsupa had the opportunity to join a Buddha image consecration ceremony and Mahachat festival in 2017. Monks and novices led different tasks and were followed by laypeople. Laymen and laywomen were general participants, and none of them seemed to be assisting the monks.

To compare the situations in Vientiane and Luang Prabang, it is important to compare their lay and monastic populations. In Luang Prabang, several sons are ordained as monks/novices or work in other districts or even different countries. Unemployed or retirement-aged laywomen are left behind in large numbers. They therefore have more time to spend on Buddhist activities. In contrast, in Vientiane there is a monastic school called Vat Ong Tü with a large number of monks and novices who can help in Buddhist ceremonies; thus, laywomen are not required for ceremonies.

Dhamma is literally defined as the “teachings of the Buddha”; the Dhamma script is thus the script used for the Buddha’s teachings. Buddhist texts were transmitted in the Dhamma script, literacy in which was limited to monks and novices. As Buddhism and religious texts were studied at monasteries by monks, laywomen were not encouraged to participate in the classes so as to avoid any scandals. Women consequently lacked the opportunity to gain Dhamma script literacy and were unable to inscribe manuscripts. Emma Tomalin’s (2006, 389) interviewees in Thailand suggested the creation of a respected and recognized community of female ordinands that could enable the institutionalization of girls’ education in the temples. To gain knowledge of Buddhism or the Dhamma script, women needed to seek opportunities on their own21) or do self-study. For instance, Maekhao Mi, a nun whom Tsomo met in the village of Sebangfai in Laos, was interested in learning languages and even kept palm-leaf manuscripts in her kuṭi for learning the Dhamma script.22)

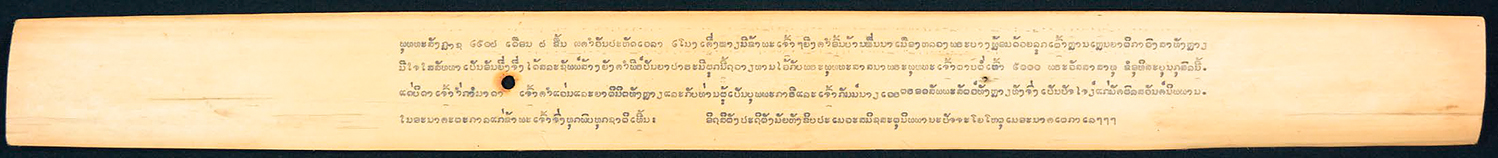

Since manuscripts consist not only of texts but also of objects, in order to compensate for their lack of opportunities and skills women could offer material and/or financial support to sponsor manuscript production. Colophons record a number of women as sponsors of Thai-Lao manuscripts, mentioning their responsibilities for certain objects (see Tipitaka [DTP] 2017, 43; Silpsupa 2022, 222, 300). Fig. 2 shows the colophon of a palm-leaf manuscript from Luang Prabang, written in 1963 CE and mentioning the tasks of a female sponsor. The colophon mentions Ms. Khamin and her family from Mün Na village, who donated this manuscript to a monastery in 1963. Ms. Khamin dedicated the merit to her deceased parents, all beings, those with whom she had been negatively involved in her previous lives, and enlightenment.

Fig. 2 Colophon of a Palm-Leaf Manuscript that Mentions a Female Sponsor. Panya Palami (Rewards Derived from Following The Thirty Perfections)

Besides providing objects, laywomen supported manuscript production in other ways. The two most frequent alternatives were donating hair and wrapping cloth. The first represented or “replaced” monkhood ordination, while the second replaced Dhamma script literacy. In other words, monks wrote texts in manuscripts while women donated textiles for the production of manuscripts.

3.1 Donation of Hair: Compensation for Monkhood Ordination (Masculinity)

In the ashrama23)—the Hindu philosophy of four life stages—the last stage, sannyasa (asceticism), is defined by the renunciation of all forms of material desire and settling into an ascetic life. Sannyasa practitioners (known as sannyasin) shave their heads (mundana) to symbolize their detachment from worldly beauty or physical appearance and spend their time on prayer and meditation. In the Hindu tradition, the hair one is born with is regarded as an undesirable remnant of past lives. In the mundan (Hindu hair-removal ceremony), the child’s head is shaved to signify freedom from the past and a move forward to the future. It is also believed that shaving a child’s head will stimulate the growth of the brain and nerves, while a tuft at the crown of the head will protect one’s memories (Trüeb 2017, 2). Shaving the head is sometimes associated with asceticism and was practiced also by Prince Siddhattha.

In contrast, according to Manusmṛiti (Laws of Manu), the text containing Hindu codes of conduct, uncut hair is considered to render so much prestige that those who snatch and drag someone by the hair are punished by having both their hands cut off (Trüeb 2017, 2). Hair thus signifies one’s social status. As the head sits at the top of one’s body, the head and hair are in some cases regarded as taboo areas that can be touched only with permission. In India hairdressers and clinical trichologists are considered to have a special prerogative (Trüeb 2017, 2). In Thailand and Laos people believe in khwan or spirits that reside in one’s head.24) The house of khwan is characterized by a swirling or whorl-shaped cluster of hair at the top of one’s head. Touching someone’s head with disrespect is regarded as an improper act that can drive the khwan out of that person. Another widespread belief regarding the head is about one’s guardian pagoda, known as Chu That (ชุธาตุ). According to a traditional Northern Thai belief, before a spirit gets a new rebirth it stays in a certain pagoda (Th: chu that ชุธาตุ), led by the animal of the year (Th: tua poeng ตั๋วเปิ้ง). Then it moves to the head of the newborn’s father for seven days, after which it enters the mother’s pregnancy. The 12 animal years are associated with the 12 holy guardian pagodas in the northern and northeastern regions of Thailand as well as some other countries.

According to Ralph Trüeb (2017, 3), offering hair to the gods is a symbolic gesture of surrendering one’s ego and expressing thanks for one’s blessings. A well-known scene from the Buddha’s life story Paṭhamasambodhi (1844–45), in which Gotama Buddha reunites with his family members in Kapila city, represents this idea. Bimbā, the wife of Prince Siddhattha or Gotama Buddha, unties her hair before respectfully cleaning his feet with it. Although Bimbā’s hair is not cut as an offering, the cleaning of Gotama Buddha’s feet in this way illustrates the hair being used as a means to clean. Offering the topmost physical organ of one’s body to the bottom part of someone else’s, or letting one’s highest organ touch someone else’s lowest organ, represents the utmost respect and surrender. At the National Museum in Khon Kaen Province, Thailand, there is a sandstone bas-relief (c. 857–957 CE) portraying this famous scene (see Fig. 3). Following is a description of the scene from Bimbābilāpaparivatta (Bimbā’s sorrow), the 18th episode in Paṭhamasambodhi, describing the sad Bimbā who prostrates herself and lays her head on the Buddha’s feet:

Fig. 3 Sandstone Bas-Relief Showing the Scene of Bimbā Wiping the Buddha’s Feet with Her Hair (photo by Silpsupa Jaengsawang, August 23, 2024)

เมื่อมีพระเสาวนีย์ตรัสปริภาษอัสสุชลธาราดังนี้ ก็ค่อยดำรงพระสติอดกลั้นเสียซึ่งความโศก เสด็จคลานออกมา โดยพลัน จากครรภ์ทวารสถานที่สิริไสยาสน์ พระกรกอดเอาข้อพระบาทซบพระเศียรลงถวายนมัสการ ลงพลางพิลาปกราบทูลสารว่า [. . .] เมื่อพระพิมพาเทวีบรรยายปริเทวนกถา โดยนัยพรรณนาฉะนี้ แล้วก็กลิ้งเกลือกพระอุตตมางคโมลีเหนือหลังพระบาทพระศาสดาโศกาพิลาป

After she (Bimbā) sadly complained to the Buddha with tears, she collected herself, left her sleeping chamber, walked on her knees, held his feet with her hands, laid her head on his feet to pay respects, and said . . . when she expressed her sadness, she rolled her head on his feet. (His Supreme Patriarch Prince Paramanujitjinorot 1970, 275–276).

Beliefs about the head and hair, the highest physical organs, being venerated and properly treated are associated with the Buddhist religion in Northern Thailand and Laos, where women have traditionally had long hair. This influenced the manuscript culture in these areas—for instance, women removing their hair to make book-binding thread for manuscripts.

3.1.1 Use of Women’s Hair in Other Areas: China

Historical evidence from other Buddhist-influenced areas shows laywomen dedicating their hair to pay respects to the religion. In China, for instance, there was a tradition of hair being used for hair embroidery (髪繡 faxiu)—the use of human hair as thread for stitching images on textiles. Hair embroidery was associated with success and prosperity, and during the Ming and Qing periods it was something that pious women did as a Buddhist devotional practice. According to Sun Peilan (1994), hair embroidery started in the Wu area during the Song period. There is a record of a young woman named Zhou Zhenguan from the Song Dynasty pricking her tongue and copying seventy thousand characters of the Lotus Sutra with her blood (Sun 1994, 31; Li 2012, 138). She then removed hairs from her head and used them to stitch every character. She started at the age of 13 and finished after 23 years. After finally completing the piece, she passed away while sitting cross-legged. Through the literature, at the very least one can be assured that the head was regarded as the highest organ, a dome of sacredness and intimacy.

Buddhist embroidery during the Tang (618–907) and Song (960–1276) valued each stitch as a Buddha. Embroidery, a labor-intensive activity, is based on the accumulation of one stitch after another, and it is the accumulated labor that is cherished in the embroidering of Buddhist imagery. Hair offering was thus regarded as a bodily organ being externalized as a gift or spiritual exchange in the name of Buddhism. When hair was used as thread and transformed into images of divine figures, it became a gift or bushi (布施) (Li 2012, 133, 141, 153). From the fifteenth century onward, more and more women combined their skills and talents with resources they found in their bodies. They used their hair as thread to stitch images of Buddhist deities as a way of emulating practices such as writing scriptures in blood. Such physical sacrifice can be compared to the sacrifices of Vairocana Buddha, who used various parts of his body as mediums to convey the Dhamma (he peeled off his skin and used it as paper, broke off his bones and used them as pens, used his blood as ink, etc.). He used parts of his body as substitutes for secular tools, such as a pen, paper, and ink (Li 2012, 142). The Buddhist doctrines of detaching from worldly desires to reach nibbāna, laywomen having long hair, and having pure intention to join in the production of religious manuscripts drew women to eventually find ways to compensate for their inferior status by donating parts of their physical bodies instead.

3.1.2 Use of Hair for Manuscripts

Laywomen’s contributions to manuscripts came in the form of objects such as writing support, writing tools, writing substances, wooden covers, bookbinding thread, and wrapping cloth. Women could make bookbinding thread out of their hair and wrapping cloth with their skill of weaving. With respect to hair donation, long-haired women braided their hair into sai sanòng (สายสนอง), a book-binding thread for palm-leaf manuscripts that runs through the holes of the folios of a fascicle (see Fig. 4 below). There is no reliable documentation regarding the period in which this tradition became widespread. Traditionally, sai sanòng were made of materials such as cotton, silk, and jute. To pay homage to the Buddha’s teachings in religious manuscripts, women could offer their hair by making a wish with every hair they removed, grouping the hair, and braiding it into a thread. By offering the highest and most precious part of their body and their effort of weaving the hair into durable bookbinding thread, the women were able to demonstrate their ardent Buddhist faith. The authors were not able to meet any women who had donated their hair for manuscript production.

Fig. 4 Bookbinding Thread Made of Hair (year unknown) (photo by Porpon Suksai, January 15, 2020)

Petavatthu (Ghost stories), Faculty of Archaeology, Silpakorn University

Donating one’s hair at the altar of religion also represents the renouncement of worldly desires. At his ordination ceremony a monk candidate has his head and eyebrows shaved. In addition to following Gotama Buddha’s cutting of hair to show his renunciation of kingship, hair removal signifies detachment and a reduction of worldly pleasure over physical appearance, which is also defined as defilement (kilesa) that likely distracts monks from self-practice and meditation. This practice would obviously resonate with the community performing ordination rituals in nineteenth-century Myanmar, reminding them that shaving their heads and taking vows was following in the footsteps of the Buddha. The cutting of hair is the most symbolic monastic renunciation of worldly life (Kaloyanides 2023, 240fn121). Buddhist disciples therefore have regularly scheduled Shaving Days four times a month, corresponding with the eve of a Buddhist Holy Day.25) In this sense, hair donation by women for the making of religious manuscripts symbolized a faithful resolution to detach from all kinds of worldly desires and escape the cycle of rebirth (saṃsāra) to attain enlightenment (nibbāna).

In early Buddhist texts, the ways prescribed for women to dedicate their bodies to their faith were probably limited to the natural resources of their bodies—for instance, long hair could be offered in exchange for merit. There is also evidence of the nails of the dead being offered for the production of religious manuscripts, in the form of a knot attached to a bookbinding thread. Although there is hardly any reliable evidence on the gender of nail donors, the donation of nails for use as knots for book-binding thread is another example of organ sacrifice in veneration of the teachings of the Buddha. This organ sacrifice is similar to the self-sacrifice of the Bodhisatta (someone on the path to Buddhahood) for the sake of religion in his several previous births. His sacrifice was part of the Perfection of Generosity (Dānapāramī) and eventually led to his very last birth as Gotama Buddha.

The gift of body or self-sacrifice is the ultimate level of the perfection of generosity in the system of the 30 perfections. It seems that the Buddhavaṃsa is the first text in the Pāli canon in which the 30 perfections are mentioned. (Arthid 2008, 780)

The practices of weaving one’s hair into bookbinding thread and weaving textile into wrapping cloth are similar: strands of hair were braided into bookbinding thread, while strands of fabric (silk, cotton, jute) were woven into wrapping cloth. Textiles compensated for religious texts being conventionally inscribed or “woven” by monks. The donation of wrapping cloth was thus another representation of the Buddhist religious faith.

3.2 Donation of Wrapping Cloth: Compensation for Dhamma Script Literacy (Skills)

In ancient times, although women shared some household tasks with men, such as harvesting, taking care of livestock, product exchange, and trading to earn a living, certain tasks were reserved for women: these included textile weaving and embroidery. Clothes and other household linens—pillows, curtains, bedsheets, etc.—were woven by female members of the family. From older female family members, women learned to make textiles with weaving looms and embellish them with embroidery; weaving and embroidery were thus passed down the generations within households. Knowledge of textile production was wholly “owned” by women, as opposed to knowledge of rice farming, which was shared by men and women. Women became the original givers of domestically produced textiles (Lefferts 2003, 90–91). Weaving was a sign that a young woman was reaching adulthood by gaining the ability to provide for the textile requirements of a household (Lefferts, n.d., 44). Since knowledge of weaving and embroidery was transmitted orally within families, no manuscripts on this have been discovered in the region.

Fig. 5 Decorative Banners at the Mahachat Festival in Luang Prabang, March 17–19, 2017 (photo by Silpsupa Jaengsawang)

In addition to general textile products used in everyday life, those for special occasions, especially religious events, were also the responsibility of females. Women took pride in their individual decorative styles. Certain materials, such as yarn and cotton (Wattana 2012, 49), and colors were related to traditional practices: for instance, white cloth was used for triple-tailed banners at funerals (Surapol 1999, 227–228). Vertical banners made of small pieces of cloth sewn together were hung on the wall of an ordination hall during the Mahachat festival26) (see Fig. 5). In Myanmar women traditionally weave monk robes in a special robe-weaving contest at the Shwedagon Pagoda on the occasion of Kathin.27) Hand towels and handkerchiefs for monks, with or without decorations, are made by women. Tablecloths for monks’ breakfast are another example. Weaving textiles for religious reasons was regarded as a channel for women to participate in meritorious activities. The most pride-filled weaving task is for women to make monk robes for their sons. Although monk robes are available in the market, they are still traditionally given by mothers to their sons (Lefferts, n.d., 45). With a deep-rooted belief in shared merit derived from monkhood ordination, mothers and/or other female family members weave cloth and dye it yellow for monk robes, expecting glorious merit that will lead them to the heavens and eventual nibbāna. The religious belief of depending on the merit derived from the ordination of one’s own sons is reflected also in the well-known Thai phrase “holding the edge of a yellow robe [to reach up to heaven] (เกาะชายผ้าเหลือง kò chai pha lüang).” In Laos young monks explained that they had chosen this path for the sake of their parents, especially their mothers, to whom they could transfer the merit they made (Lefferts, n.d., 44). Thus, although women may not be ordained as monks, they can gain merit through their sons by means of making monk robes for them.

For ordination and other Buddhist ceremonies, the wrapping cloth for religious manuscripts was made by women. Buddhist teachings were orally transmitted by Gotama Buddha during his lifetime, and over the centuries they were revised (classified and systematized) by successive teachers in order to facilitate memorization (U Ko Lay 1984, 18). The Buddhist canon or Tipiṭaka was divided into three sections, or baskets (piṭaka), during the third revision in 235 BE in India. During the reign of King Vaṭṭhagāmaṇīabhaya of Sri Lanka, around 450 years after Gotama Buddha’s parinibbāna, the Buddhist canon was first put down in writing, in palm-leaf manuscripts. As the Pāli language did not have its own script, transmission was done using local scripts that were aurally similar to Pāli pronunciation: the Dhamma, Lao Buhan, Lik Tai Nüa, Khom, Central Thai, and Tai Dam scripts. These scripts can be traced to South Indian writing systems, which were adapted for writing Pali and vernacular languages in Southeast Asia (CrossAsia, n.d.). Hence, the tradition of donating wrapping cloth for religious manuscripts began long after the Buddha’s lifetime. Manuscripts mentioning the practice of donating wrapping cloth were written a couple of centuries ago: Sòng Pha Phan Nangsü (Rewards derived from the donation of manuscript wrapping cloth) (1850) (Digital Library of Lao Manuscripts, code: 06011406012-16) and Salòng Hò Pha (Rewards derived from the donation of manuscript wrapping cloth) (1967) (Buddhist Archive of Photography, code: BAD-22-1-0934); both are found in Luang Prabang.

Women were responsible for all decisions on the material, weaving styles, sizes, colors, patterns, and decorations of manuscript wrapping cloth. In Northeastern Thailand the cloth was usually a vertical sheet, sometimes drawn or painted with the story of Vessantara Jātaka. The cloth could be decoratively displayed when not in use for wrapping manuscripts (Wattana 2012, 49). Before the development of wall paint, textiles were often used to beautify venues. Colorfully patterned door curtains shielded certain rooms from inquiring glances (Lefferts, n.d., 44).

Wrapping cloths could be offered to a monastery together with a particular manuscript or separately. The names of the weavers were not necessarily written on the cloth unless it was donated separately; otherwise, the names of all commissioning agents were often mentioned in the colophon. Wrapping cloths that were separately donated were collected and kept for future manuscripts that were donated without an accompanying cloth.

Since wrapping cloths were created by hand, they contained clues about the maker’s weaving skills, social status, wealth, and attitude. The better the quality of the threads, the higher was the social status of the weavers, because not everybody could source good-quality materials. Imported materials, in particular, could be accessed mostly by high-ranking people.28) Weaving patterns and embroidery styles displayed the weaver’s skills as well as aesthetic taste. Thus, wrapping cloths were a medium that represented the personal identity, taste, skills, endeavor, social status, and roles of weavers in their cultural contexts (Ciraphòn 2009, 56–57).

Weaving and donating wrapping cloth was regarded as a form of participation in the textual transmission of the Buddha’s teachings—the study of the Dhamma—which lay on the path to enlightenment. Through monkhood, men had the opportunity to gain a Buddhist monastic education so as to eventually reach nibbāna, which was the ultimate goal, as reflected in (Pāli) phrases at the end of colophons. Women, however, were unable to become monks, which was regarded as an essential step for reaching nibbāna. To compensate for this lack of opportunity, women created wrapping cloth—although the tradition of weaving and donating cloth developed originally to protect manuscripts from insects and humidity, to keep them in well-organized bundles, and to venerate the Buddha’s teachings (see Fig. 6).

Fig. 6 Bundle of Palm-Leaf Manuscripts with Wrapping Cloth (photo by Silpsupa Jaengsawang)

Monks and novices studied canonical and other religious texts from palm-leaf manuscripts that were—whether in Pāli or in the vernacular—written entirely in the Dhamma script. Thus, they came to learn the Dhamma script and the Pāli language by reading, writing, memorizing, and transmitting religious texts. For women, on the other hand, the only path to nibbāna appeared to be through participating in the production of religious manuscripts. Accordingly, manuscripts written by males and wrapping cloth made by females represented reciprocal merit-making by Buddhists of both genders with the common goal of sustaining and protecting the teachings of the Buddha. According to the Buddha’s prophecy of the Five Disappearances (Pañca-antaradhāna),29) the teachings of the Buddha will fade out (Pariyatti-antaradhāna) over the course of time until the Buddhist Era’s five-thousandth year, followed by the other four disappearances.30) The collaboration between men and women for transmitting and protecting religious texts was done in an effort to prevent the Buddha’s teachings from dying out.

3.3 Other Alternatives

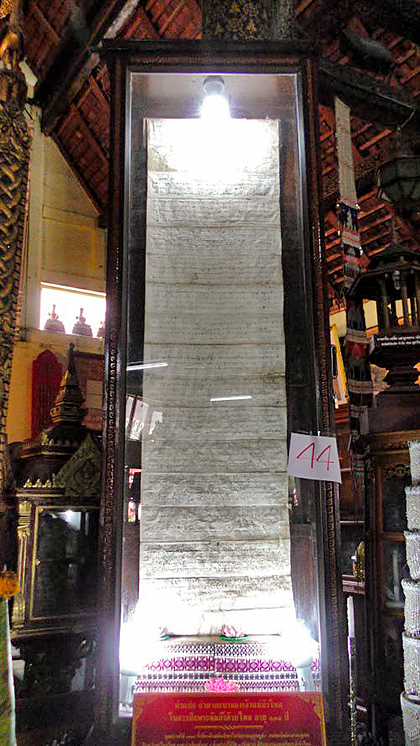

Other choices that women made to gain merit from manuscript production and preservation varied depending on their individual skills and available materials. For instance, there is a cloth manuscript embroidered by Lady Bualai Thepphawong, the wife of the last ruler of Phrae, Lord Phiriya Thepphawong (1836–1912), whose expertise in embroidery was well known. Written in Pāli with the Dhamma script and embroidered with gold-colored thread, the manuscript is titled Kammavācā31) and was displayed in a vertical showcase at the museum of Wat Phra Bat Ming Müang, Phrae Province, Northern Thailand (see Fig. 7). It has since been moved to another building.

Fig. 7 Embroidered Cloth Manuscript by Lady Bualai Thepphawong in the Main Monastic Hall of Wat Phra Bat Ming Müang (photo by Silpsupa Jaengsawang, 2018)

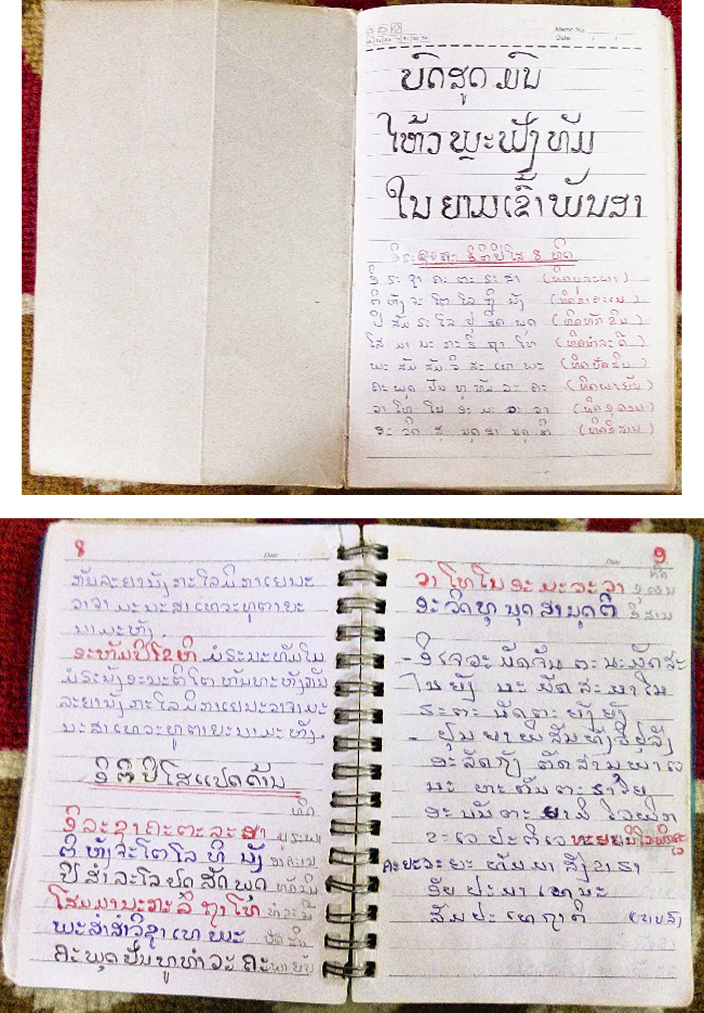

The following paper manuscripts, surveyed by Silpsupa Jaengsawang in August 2022, were written by a senior laywoman named Bunyong, a ritual expert in Ban Saen village in Luang Prabang. With her remarkable ability to memorize Pāli prayers and ritual processes, as in some ethnic groups of Tai Dam where a woman functions as the leader of the su khwan (consolation) ceremony (Tsomo 2010, 90), Bunyong led villagers in reciting Pāli prayers and interacted with monks at religious ceremonies. She made two copies—one for herself and the other for a friend—of a ceremony manual composed of various Pāli prayers derived from printed books and suggestions for acts. The manuscripts were written in blank notebooks in the modern Lao script with ink pen (see Fig. 8).

Fig. 8 Two Paper Manuscripts Made from Blank Notebooks by Ms. Bunyong from Luang Prabang (photo by Silpsupa Jaengsawang)

Another female scribe was Mae Thao (grandmother) Saengcòi, who wrote texts in the Lik script. She learned the script from her family and copied several mulberry paper manuscripts in the Thai Nüa manuscript culture, located in northwestern Laos, southwestern China (Yunnan), and northern and eastern Myanmar (Kachin State and Shan State, bordering northwestern Laos). She died in 1998 at the age of 81 (Wharton 2017, 43) and seems to have been among the last female scribes from the region.

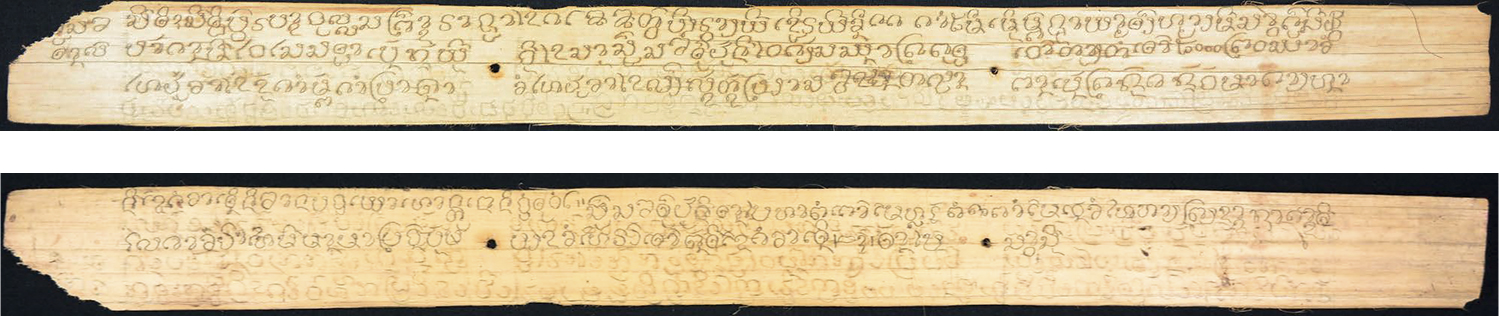

In addition to providing materials and tools for manuscript production, females are recorded in some manuscript colophons as offering financial support and facilities. Some females were even engaged in commissioning manuscripts. In the case of anisong manuscripts,32) for instance, there are similar numbers of lay sponsors and Sangha sponsors mentioned. Most of the lay sponsors were female. Harald Hundius (1990) calls the sponsors initial, or leading, lay monastic supporters of manuscript production. A large number of laypersons certainly sponsored manuscripts kept in Vat Si Bun Hüang, Luang Prabang. Khamvone Boulyaphonh and Volker Grabowsky (2017, 32) explain that in the catalogue of manuscripts discovered at the temple, laypeople formed the large majority of manuscript sponsors and donors: four-fifths were laypersons and only one-fifth members of the Sangha. Fig. 9 shows an excerpt from a palm-leaf manuscript from Luang Prabang written in 1926. The colophon mentions that the manuscript was donated in 1926 CE by Ms. Kòngsi from Kang village for a merit dedication to Ms. Sin.

Fig. 9 Colophon of a Palm-Leaf Manuscript Mentioning a Female Sponsor

Sòng Sapphathung (Rewards Derived from the Donation of All Kinds of Religious Banners)

Today, with people becoming increasingly interested in the preservation of local heritage, senior laywomen spend their free time volunteering and assisting in monastic libraries where ancient manuscripts are maintained and exhibited. As their library responsibilities are unrelated to discursive tasks, most of the volunteers are not able to read the manuscripts. They take care of them as cultural heritage objects and to prevent them from being stolen and damaged. Occasionally, they clean and rewrap manuscripts, rearrange manuscripts on a shelf, repair the wrapping cloth, or even make new wrapping cloth and donate it to the library.

4 Texts and Textiles in Compensation

As mentioned earlier, the production of religious manuscripts required monkhood status and Dhamma script literacy. To compensate for their lack of both these opportunities, women donated their hair and wove textiles to bind and wrap religious manuscripts. Donated hair compensated for the women’s lack of masculinity and thus monkhood, while textile-weaving skills compensated for their lack of literacy in the Dhamma script. Thus, although women were excluded from the creation of manuscript texts, they compensated by donating textile products and other objects.

Why did women choose to make up for their physical disadvantage by donating hair? It could be because heads were revered as the place where holy spirits resided. Cleaning someone’s feet with one’s hair thus symbolized the greatest respect, and donating one’s hair for making bookbinding thread implied a deep religious faith. In a sense, women’s long hair could be viewed as compensating for monks’ shaved heads. Hence, hair donation could represent both great respect for Buddhism and a solution to the female physical condition.

Why did women weave textiles to compensate for their lack of Dhamma script literacy? This can be regarded as a cultural phenomenon. The writing of manuscripts and weaving of textiles share a common feature: proficiency in a skill. Men had the opportunity to learn the Dhamma script, while women had the opportunity to learn textile weaving. The transmission of such forms of knowledge was specifically tied to gender: the Dhamma script was taught to monks in order to sustain and propagate the Buddha’s teachings, while textile weaving was taught to women so they could contribute to the household economy. While men used their Dhamma script literacy to produce religious manuscripts, women used their textile weaving ability to participate in the production of these manuscripts. Although men could only write the manuscripts while women could only participate in their production, both derived shared merit from the commissioning of a manuscript.

Manuscript writing and textile weaving had another feature in common: the creation of a new composition using diverse elements. When writing a manuscript, scribes or copyists inscribed alphabets (consonants, vowels, numerals, symbols, etc.) with writing tools and writing substances. The letters were interwoven to compose a certain text. When weaving textiles, weavers or craftsmen connected strands of thread (cotton, silk,33) jute, etc.) to create a new sheet of cloth. According to Ñāṇodaya, “every single letter of the Buddha’s teaching has the same value as a single Buddha image” (Seeger 2006, 157). In this sense, combining alphabets into text and combining strands of thread into a sheet of cloth can both be described as a weaving craft that requires special skills, and one alphabet can have the same value as one strand of thread. Manuscripts woven with alphabets and wrapping cloths woven with strands of thread are both the result of special abilities that are used to demonstrate a faith in Buddhism. Texts and textiles thus share the common character of being compositions of interwoven elements. Hence, writing and textile weaving are both activities that combine elements according to certain guidelines into a structured outcome:

Literary works must be composed somehow. It is part of their nature to be woven, constructed, fabricated, collected together out of disparate elements. Most of these meanings are implied by the Latin textere, from which the English word “text” is derived. (Griffiths 1999, 22)

5 Conclusion

The donations of hair and manuscript wrapping cloth were a result of laywomen’s struggles to partake in merit derived from producing and dedicating religious manuscripts. They did not believe that this merit should be limited to males, and they finally found ways to participate in gaining something that they considered precious. Their long hair being braided into bookbinding thread and their expertise in weaving and embroidering wrapping cloth were acknowledged as valuable in replacing monkhood status and Dhamma script literacy. Hair donation was a physical sacrifice to compensate for the lack of monkhood status, and the donation of wrapping cloth was an object sacrifice to compensate for the lack of ordination opportunities that led to Dhamma script literacy.

The eventual manuscript thus benefited from collaboration between both genders: men wrote texts for manuscript production, while women wove textiles for manuscript protection. The phenomenon reflects the gaining of shared merit by people of both genders in Thai-Lao Theravāda Buddhist society, where women are socially inferior. The collaborative merit-making implies that gender discrimination was not too strong: it was acceptable for women to participate in meritorious practices. Their hair was acceptable, and their textile weaving ability was also appreciated and included in the process of manuscript donation and thus merit making.

Acknowledgments

Research for this article was funded by the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy–EXC 2176 “Understanding Written Artefacts: Material, Interaction and Transmission in Manuscript Cultures,” project no. 390893796. Research was conducted within the scope of the Centre for the Study of Manuscript Cultures at Universität Hamburg. We owe the greatest debt of gratitude to the two anonymous reviewers who spent their precious time on reading and providing critical comments on our paper. We learned a lot from their contributions and their recommendations on other books and articles. This paper is greatly improved thanks to their support.

Notes

1) Notes on Romanization of Thai and Lao

The Romanization in this paper follows the regional pronunciation of the Thai and Lao languages by means of the Romanization system devised for conveying Thai syllables at the Asia-Africa Institute of Universität Hamburg. This system largely follows the system of Romanization stipulated by the Royal Thai Academy (Royal Institute 1941), with slight modifications. For example, there are two additional symbols (ü, ò) (for representing อือ and ออ). This simplified Romanization of Thai (and Lao) terms does not indicate vowel lengths or tones. With respect to the names of specific temples in Laos, the consonant /ວ/ is usually transcribed as “v” by scholars of Lao studies; thus, the term “temple-monastery” in proper names is spelled as “vat” in Lao instead of “wat.” Yet, when referring to a Thai temple-monastery in general, “wat” is used.

2) Sutta or Suttanta Piṭaka is a compilation of the word of the Buddha in discourses—i.e., his sermons, lectures, and explanations of Dhamma that were delivered to suit particular individuals and occasions—along with compositions, narratives, and stories that originated in early Buddhism (Payutto 2002, 36).

3) There are five divisions in Suttanta Piṭaka: Dīgha Nikāya, Majjhima Nikāya, Saṁyutta Nikāya, Aṅguttara Nikāya, and Khuddaka Nikāya.

4) Tipiṭaka literally means “three baskets,” representing the three collections of the Buddhist canon: Vinaya Piṭaka (Collection of rules for monks and nuns), Suttanta Piṭaka (Collection of sermons, histories, stories, and accounts), and Abhidhamma Piṭaka (Collection of teachings and explanations in purely academic terms).

5) Myths are a form of folktales. According to Stith Thompson (1977), there are 11 categories of folktales: fairy tales, novellas, hero tales, sagas, explanatory tales, myths, animal tales, jests, formula tales, religious tales, and ghost tales.

6) The Ābhassarā realm is the realm of Brahmas with radiant lustre. Gunapala Piyasena Malalasekera (2009, 512) gives details on the Ābhassarā realm in terms of realm beings being reborn on Earth: “The idea of a return to an original purity could be found in relation to the development of deeper states of concentration. According to Buddhist cosmology, when the world-system goes through a period of contraction beings are reborn in the Ābhassarā realm (D. I, 17; D. III, 84), from which they eventually depart to be reborn on earth once the world-system has re-expanded. The Ābhassarā realm is the cosmological counterpart to the attainment of the second jhāna. Hence one who in the human realm succeeds in attaining this level of concentration could indeed be reckoned to be returning to an original purity of the mind, a degree of purity experienced a long time ago when living in the Ābhassarā realm during a time when this world-system had contracted.”

7) There are 16 Form-Spheres (Rūpabhava, Fine-Material Sphere): Brahmapārisajjā (Realm of great Brahmas’ attendants), Brahmapurohitā (Realm of great Brahmas’ ministers), Mahābrahmā (Realm of great Brahma), Parittābhā (Realm of Brahmas with limited luster), Appamāṇābhā (Realm of Brahmas with infinite luster), Ābhassarā (Realm of Brahmas with radiant luster), Parittasubhā (Realm of Brahmas with limited aura), Appamāṇasubhā (Realm of Brahmas with infinite aura), Subhakiṇhā (Realm of Brahmas with steady aura), Vehapphalā (Realm of Brahmas with abundant rewards), Asaññīsattā (Realm of non-percipient beings), Avihā (Realm of Brahmas who do not fall from prosperity), Atappā (Realm of Brahmas who are serene), Sudassā (Realm of Brahmas who are beautiful), Sudassī (Realm of Brahmas who are clear-sighted), Akaniṭṭhā (Realm of the highest or supreme Brahmas). There are four Formless Spheres (Arūpabhava, immaterial states): Ākāsānañcāyatana (Sphere of infinity of space), Viññāṇañcāyatana (Sphere of infinity of consciousness), Ākiñcaññāyatana (Sphere of nothingness), and Nevasaññānāsaññāyatana (Sphere of neither perception nor non-perception) (Payutto 2015, 271–272).

8) “Motivated by the wish to live a celibate life dedicated to progress to awakening, the Buddha’s fostermother Mahāprajāpatī Gautamī/Mahāpajāpatī Gotamī requests permission for women to go forth. The Buddha refuses. Mahāprajāpatī Gautamī and her followers nevertheless shave off their hair, put on robes, and follow the Buddha on his travels. The Buddha’s attendant Ānanda intervenes on their behalf, raising the argument that women are in principle able to reach awakening. The Buddha gives permission for women to join the order” (Anālayo 2019, 40).

9) These 13 are Pajāpatī (praised for her long standing as the first nun), Khemā (praised for her great intellect), Upalavaṇṇā (praised for her divine miracles), Paṭācārā (praised for her good memory of the Vinaya), Dhammadinnā (praised for her homiletic expertise), Nandā (praised for her meditation), Soṇā (praised for her endeavor), Sakulā (praised for her divine sights), Bhaddā-Kuṇḍalakesī (praised for her sudden enlightenment), Bhaddāpilānī (praised for her ability to remember past lives), Bhaddākaccānā (praised for her success in attaining great apiññā), Kīsāgotamī (praised for her habit of wearing coarse robes), and Sigālamātā (praised for her renunciation of defilements with her faith) (Samer 1981, 37–38).

10) Her name was Bhaddā, but she was known as Kuṇḍalakesā for her curly hair (Bhaddā-Kuṇḍalakesā). She became an ascetic after being almost killed by her husband in a trick. She lost a debate to Venerable Sariputta and became a Buddhist nun. Her brilliant attainment of Arahantship was praised as being the fastest among all the nuns: “Just as the wanderer Bahiya was foremost amongst monks who attained arahantship faster than anyone else, she was foremost amongst nuns with the same quality” (Hecker 1994, 25).

11) The texts define the menace of lust caused by seeing women wearing their clothes improperly or carelessly, unintentionally letting parts of their bodies show. Regardless of women’s intention of physical—or even sexual—exposure, the sight of private parts of female bodies is considered a menace.

12) Women are metaphorically compared to the five kinds of danger of a cobra: anger, revenge, venom (lust), forked tongue (instigation), and ingratitude (unfaithfulness).

13) Five statuses are never attainable for females: a Buddha, a wheel-turning king (cakkavatti), a heavenly king (God Sakka), Lord Māra, and a being in the Form-Sphere (rūpabhava) and Formless Sphere (arūpabhava). Although one can achieve the five statuses by accumulating merit no matter what one’s gender, in the end one will be reborn in the five statuses only as a male. Gender does not matter in the process of accumulating merit to gain status, but actually being in the status is another matter. This gender discrimination can be found also in the case of the Tusitā heaven, which is inhabited only by male beings. Women who have accumulated sufficient merit and can eventually attain rebirth in the Tusitā level are born male in order to reside there.

14) In general there are two types of jātaka: canonical jātaka and non-canonical jātaka. Canonical jātaka (547 stories) are found in the Buddhist Pāli canon (Tipiṭaka). The well-known set of non-canonical jātaka in Thailand is Paññāsa Jātaka or Bāhira Jātaka. The term defines jātaka that are absent in the canonical 547 jātaka in Khuddaka Nikāya, the Buddhist canon, as bāhira (Pāli) means “external,” “foreign,” “outside” (U Ko Lay 1984). The Northern Thai Piṭakamālā calls the Paññāsa Jātaka “the fifty births outside the saṅgāyanā” (Skilling 2006, 130). It has been found in Siam, Laos, Cambodia, Lan Na, and Myanmar. For the Pali National Library collection, Prince Damrong proposed the date 1457–1657 CE. The Paññāsa Jātaka of the Lan Na collection is supposed to have been composed by monks from Chiang Mai. Invented or apocryphal Paññāsa Jātaka stories are derived from Pāli/Sanskrit Buddhist texts, local folktales, India, and Paññāsa Jātaka themselves and have been transmitted in different languages and scripts, from local Pāli to nissaya. Individual stories included in Paññāsa Jātaka, not the set as a whole, had an enormous influence on Siamese literature. Classical Siamese literature does not treat the stories as extracts from the set of fifty; each story exists in its own right (Lamun 1995, 79; Skilling 2006, 134, 146, 148). In Thailand manuscripts were compiled by different persons and monasteries: King Anantawòrarit who had ten manuscript bundles copied in 1861/62 and 1863/64; a complete manuscript version (1834–36) kept at Wat Sung Men, Phrae Province; and other vernacular collections including that of Verenable Thip Chutithammo, the abbot of Wat Min, Chiang Tung (Skilling 2006, 148–149, 151).

15) Dīpaṅkara Buddha was the fourth Buddha and is mentioned in several jātaka. He prophesied that Sumedhatāpasa (later Prince Siddhattha), who devoted his body to be a bridge for Dīpaṅkara Buddha to walk on, would become a Buddha. Dīpaṅkara Buddha was from Amaravati city and the son of King Sudeva and Queen Sumedhā. There were three more Buddhas who lived in the same kappa (eon; world-eon; world-age) as Dīpaṅkara Buddha: Taṇhaṅkara Buddha, Medhaṅkara Buddha, and Saraṇaṅkara Buddha (Chollada 2013, 83).

16) The Dhamma script cultural domain includes Shan areas in Myanmar, southwestern China (Sipsòng Panna), Northern Thailand, Northeastern Thailand, Laos, and northern Vietnam.

17) Samer Boonma (1981, 41–50) gives five reasons for the decrease in the number of Buddhist nuns: (1) complicated ordination procedures, (2) disciplinary strictness, (3) female physical condition, (4) decline of Buddhism, and (5) lack of support.

18) Sikkhamānā or sāmaṇerī have to observe six precepts for two years and have to be re-ordained if a precept is broken (Samer 1981, 41–42).

19) Ralph Isaacs (2009, 121) clearly describes the Pongyibyan festival in Myanmar and mentions the roles of laywomen: generous donors earned more merit by contributing gifts for surviving monks of the monastery. The gifts were carried in a procession of padaythabin, tree-like stands of bamboo, each mounted on a bamboo platform and carried by two or four men or women.

20) During a research trip to Luang Prabang 2022, Silpsupa visited a monastery. She entered the elevated stage, set against a wall of the main monastic hall, and started looking at the books and other items there. A local layman entered the hall and spotted the author on the stage. He warned her to climb down and never go up there again. As the author was not local, the man let her off with a warning.

21) “Maekhaos (nuns) learn Buddhism informally from individual monks and by attending periodic meditation courses. Several nuns told us that they eavesdropped when a monk explained Buddhism to lay people; some stayed in the background and memorized every word the monk said. Occasionally, a nun will cross into neighbouring Thailand and enroll at a Buddhist institute there in order to learn more” (Tsomo 2010, 87).

22) “Her little kuti showed evidence of her studies, with an array of beginning English books as well as palm leaf Buddhist manuscripts. Maekhao My was teaching herself both English and Lao Tham, an ancient sacred script” (Tsomo 2010, 99).

23) The four ashramas are Brahmacharya (bachelor student), Grihastha (householder), Vanaprastha (forest dweller, retired), and Sannyasa (ascetic).

24) The term khwan is a word of pre-Buddhist Tai origin that was used in Tai, Indian (Assam), and Burmese (Shan State) regions before the Buddhist religion was propagated. In the Three Seals Law (กฎหมายตราสามดวง) the term khwan in spelled ขวั

25) There are four Buddhist Holy days per month: the eighth waxing-moon day of the lunar month, the 15th waxing-moon day of the lunar month, the eighth waning-moon day of the lunar month, and the 15th (or 14th) waning-moon day of the lunar month.

26) The Mahachat, or Bun Phawet, or Tang Tham Luang festival is held for three days during February to March in Laos and Northeastern Thailand and in October to November in Central and Northern Thailand. In the festival all 13 episodes of Vessantara Jātaka are rhythmically recited by monks. According to the story of Venerable Malaya, those who listen to all 13 episodes within one day will be reborn in the period of Metteyya Buddha, the next forthcoming Buddha.

27) “These kathina robes are distributed to monks who have observed the Lenten retreat. At the Shwedagon a special robe-weaving contest is held at this time; looms are set up to weave fresh sets of robes called matho thingan (Myanmar) for the four central Buddha images housed in the pagodas’s main sanctuaries. Teams of women representing various lay associations work the looms in shifts, cheered on by spectators, to complete the robes on time with the winning teams receiving a prize” (Pranke 2015, 31).

28) “Additionally, we know that foreign cloth was a significant factor used by élite groups to adorn and set themselves apart from the other members of the local populations. Sumptuary rules were never simply a matter of better dress; foreign cloth denotes power, prestige and access to non-native resources, and other-worldly attainment that ordinary folk could not command and that reinforced the rights and privileges of élites” (Lefferts 2003, 91).

29) The Five Disappearances (Pañca-antaradhāna) of the Buddhist order are the Buddha’s teachings (Pariyatti-antaradhāna); Buddhist practices (Paṭipati-antaradhāna); enlightenment (Paṭivedha-antaradhāna); disciplined monks (Liṅga-antaradhāna); and relics, pagodas, and temples (Dhātu-antaradhāna).

30) “In the commentary on the Aṅguttara Nikāya, it states that Buddhism will decline over time; therefore, the knowledge of the scriptures will eventually disappear. The first text to disappear would be the Paṭṭhāna, the last volume in the Abhidhamma, a text considered the most difficult to understand” (Saruya 2022, 3).

31) The formal words of an act. The text is used in ordination ceremonies.

32) Liturgical manuscripts that contain sermonic texts and explain meritorious rewards gained from several kinds of merit-making activities.

33) Donating wrapping cloth made of silk was also regarded as a form of compensation for the killing of thousands of silkworms. The sinful deed of killing was thus believed—or expected—to be forgiven, and the killed silkworms could also gain merit (Ubon Ratchathani University 2019).

References

Manuscripts

Buddhist Archive of Photography (BAP). BAD-13-1-0760. ປັນຍາບາຮະມີ. Palm-leaf manuscript; languages: Lao and Pāli; scripts: Lao Dhamma and Lao; 6 folios; CS 1325 (1963 CE). back1

Buddhist Archive of Photography (BAP). BAD-11-1-0060. ສອງສັພພະທຸງ. Palm-leaf manuscript; languages: Lao and Pāli; scripts: Lao Dhamma and Lao; 9 folios; CS 1288 (1926 CE). back1

Buddhist Archive of Photography (BAP). BAD-22-1-0934. ສະຫຼອງຫໍ່ຜ້າ. Palm-leaf manuscript; languages: Lao and Pāli; scripts: Lao Dhamma and Lao; 11 folios; CS 1329 (1967 CE). back1

Digital Library of Lao Manuscripts. 06011406012-16. ສອງຜ້າພັນໜັງສື. Palm-leaf manuscript; languages: Lao and Pāli; scripts: Lao Dhamma and Lao; 7 folios; CS 1212 (1850 CE). back1

Publications

English

Anālayo. 2019. Women in Early Buddhism. Journal of Buddhist Studies 16: 31–76. back1

Anālayo. 2009. The Bahudhātuka-sutta and Its Parallels on Women’s Inabilities. Journal of Buddhist Ethics 16: 135–190. back1

Appleton, Naomi and Shaw, Sarah, trans. 2015. The Ten Great Birth Stories of the Buddha: The Mahānipāta of the Jātakatthavaṇṇanā. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books. back1

Arthid Sheravanichkul. 2008. Self-Sacrifice of the Bodhisatta in the Paññāsa Jātaka. Religion Compass 2(5): 769–787. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8171.2008.00095.x. back1

Chladek, Michael Ross. 2017. Making Monks, Making Men: The Role of Buddhist Monasticism in Shaping Northern Thai Identities. PhD dissertation, University of Chicago. back1

CrossAsia. n.d. Language & Scripts. CrossAsia Digital Collections. https://digital.crossasia.org/digital-library-of-lao-manuscripts-resources-script/?lang=en, accessed February 13, 2025. back1

Griffiths, Paul J. 1999. Religious Reading: The Place of Reading in the Practice of Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. back1

Hecker, Hellmuth. 1994. Buddhist Women at the Time of the Buddha, translated by Sister Khemā. Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society. back1

Hundius, Harald. 1990. The Colophons of Thirty Pali Manuscripts from Northern Thailand. Journal of the Pali Text Society 14: 1–174. back1

Isaacs, Ralph. 2009. Rockets and Ashes: Pongyibyan as Depicted in Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century European Sources. Journal of Burma Studies 13: 107–136. https://doi.org/10.1353/jbs.2009.0003. back1

Kabilsingh, Chatsumarn. 1998. Women in Buddhism (Questions and Answers). Bangkok: Dhamma Education Association. back1 back2 back3 back4

Kabilsingh, Chatsumarn. 1991. Thai Women in Buddhism. Berkeley: Parallex Press. back1

Kaloyanides, Alexandra. 2023. Baptizing Burma: Religious Change in the Last Buddhist Kingdom. New York: Columbia University Press. back1

Khamvone Boulyaphonh and Grabowsky, Volker. 2017. A Catalogue of Lao Manuscripts Kept in the Abbot’s Abode (Kuti) of Vat Si Bun Hüang: Luang Prabang. Hamburg: Hamburger Südostasienstudien. back1

Lefferts, Leedom. 2003. Textiles for the Preservation of the Lao Intangible Cultural Heritage. In Laos and Ethnic Minority Cultures: Promoting Heritage, edited by Yves Goudineau, pp. 89–110. Paris: UNESCO Publishing. back1 back2

Lefferts, Leedom. n.d. Women’s Textiles & Men’s Crafts in Thai Culture. Smithsonian Institution, pp. 43–46. https://folklife-media.si.edu/docs/festival/program-book-articles/FESTBK1994_24.pdf, accessed June 6, 2024. back1 back2 back3 back4

Li Yuhang. 2012. Embroidering Guanyin: Constructions of the Divine through Hair. East Asian Science, Technology, and Medicine 36(1): 131–166. back1 back2 back3

Litalien, Manuel. 2018. Social Inequalities and the Promotion of Women in Buddhism in Thailand. Journal of Buddhist Ethics 25: 569–606. back1 back2 back3 back4 back5

Malalasekera, Gunapala Piyasena, ed. 2009. Encyclopaedia of Buddhism. Colombo: Government of Ceylon. back1

Pranke, Patrick. 2015. Buddhism and Its Practice in Myanmar. In Buddhist Art of Myanmar, edited by Sylvia Fraser-Lu and Donald M. Stadtner, pp. 27–34. New York: Asia Society. back1

Royal Institute. 1941. Notification of the Royal Institute Concerning the Transcription of Thai Characters into Roman. Journal of the Siam Society 33(1): 49–65. back1

Saruya, Rachelle. 2022. Creating Demand and Creating Knowledge Communities: Myanmar/Burmese Buddhist Women, Monk Teachers, and the Shaping of Transitional Teachings. Religions 13: 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13020098. back1 back2 back3

Seeger, Martin. 2006. The Bhikkhunī-Ordination Controversy in Thailand. Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies (JIABS) 29(1): 155–183. https://journals.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/index.php/jiabs/article/view/8976, accessed January 18, 2024. back1 back2 back3 back4 back5 back6

Silpsupa Jaengsawang. 2022. Relationship between Anisong Manuscripts and Rituals: A Comparative Study of the Lan Na and Lao Traditions. Segnitz: Zenos-Verlag. back1

Skilling, Peter. 2006. Jātaka and Paññāsa-jātaka in Southeast Asia. Journal of the Pali Text Society 28: 113–174. back1 back2 back3

Thompson, Stith. (1946) 1977. The Folktale. (New York: Dryden Press) London: University of California Press. back1

Tomalin, Emma. 2006. The Thai Bhikkhuni Movement and Women’s Empowerment. Gender & Development 14: 385–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552070600980492. back1 back2 back3 back4 back5 back6 back7

Trüeb, Ralph M. 2017. From Hair in India to Hair India. International Journal of Trichology 9(1): 1–6. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijt.ijt_10_17. back1 back2 back3 back4

Tsomo, Karma Lekshe. 2010. Lao Buddhist Women: Quietly Negotiating Religious Authority. Theology and Religious Studies: Faculty Scholarship 27(1): 85–106. https://digital.sandiego.edu/thrs-faculty/14, accessed June 3, 2024. back1 back2 back3 back4 back5 back6 back7 back8 back9