Mountain People in the Muang: Creation and Governance of a Tai Polity in Northern Laos

Nathan Badenoch* and Tomita Shinsuke**

*Hakubi Center for Advanced Research, Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University

Corresponding author’s e-mail: baideanach[at]gmail.com

DOI: doi.org/10.20495/seas.2.1_29

**富田晋介, Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University

This paper traces the history of Luang Namtha, an intermontane valley basin in northern Laos, based on the narratives of non-Tai ethnic groups that collectively constitute a majority in the region. The narratives demonstrate the possibility of alternative histories of muang polities, which are a core part of our understanding of Tai social and political organization. These narratives describe a central role for mountain people in the muang, including the formation, population, and development of what appears to be a Tai polity. This analysis suggests the need to open up our understanding of “traditional” Tai political spaces to accommodate an expanded historical agency for upland groups conventionally circumscribed within their own upland setting. This paper argues that the first step towards a more nuanced understanding of muang is recognizing them as cosmopolitan areas in which many sources of power, innovation, and transformation intersect.

Keywords: Laos, muang, ethnic minorities, local history, Lanten

I Layers of Locality: Digging for Historical Narratives

The Lanten, Sida, and Bit people living in the foothills surrounding the town of Luang Namtha in northern Laos tell of how the valley was empty when their forefathers migrated to the area at the end of the nineteenth century. Some even assert that they were the ones who established the current valley settlement and have played a central role in its governance. These claims go against our assumptions about the expected historical development of a small urban center in northern Laos. Indeed, as the plane clears the mountains and descends into the valley, one sees a town surrounded by wet rice fields that cover an area of 100 square kilometers and two Buddhist stupas on the hills overlooking the city. The village next to the airport has an old Buddhist temple, and the irrigation system extends across the valley bottom. In town, the people speak Lao and several other related Tai languages. Any student of mainland Southeast Asia would assume that they are entering the world of a typical Tai1) muang—the hierarchically organized but decentralized socio-political structures that are believed to be the backbone of cultural continuity2) running throughout the concept of Laos in history (Stuart-Fox 2002).

Towards “Indigenous Histories” in Northwestern Laos

There is no official written history of Luang Namtha. However, “official narratives” found in statements of local government offices and officers, emphasize the muang characteristics of Luang Namtha. Muang is an ambiguous term referring to the political and social organization of the Tai, but has a wide range of meaning in terms of geographic, social, and political scope (Liew-Herres et al. 2012). The conventional understanding of the history of the Luang Namtha basin encapsulates many of the assumptions that exist regarding the muang—that it was founded in the sixteenth century by a group of Tai-speaking Buddhists who set up a small polity attached to a more powerful Tai muang, supporting themselves economically by wet rice cultivation and providing a socio-political center for other latecomer ethnic groups that live on the fringe of the Tai world. Government offices often reiterate such a view on the regional social history. For example, the Lao National Tourism Authority has the following history of the Namtha valley on its website:3)

In 1890, the Tai-Yuan returned to the Nam Tha Valley under the aegis of Chao Luangsitthisan to re-establish Muang Houa Tha. Vat Luang Korn, one of Luang Namtha’s largest, was constructed shortly thereafter in 1892. However, the newly resettled Muang Houa Tha was to enjoy its independence for only two years. In 1894, following a meeting between the French, British and Siamese colonists, it was agreed that Muang Houa Tha would be administered by the French and the Mekong from the northern reaches of Muang Sing to Chiang Saen would serve as the border between French Indochina and British-ruled Burma. Not long after this divide took place the first group of Tai-Dam arrived from Sip Song Chou Tai in north western Viet Nam and established Tong Jai Village on the east bank of the Nam Tha River. At about the same time the Tai-Dam arrived, migrations of Tai-Neua, Tai-Kao, Akha, Lanten, Yao and Lahu originating in Sipsong Panna, Burma and northwest Viet Nam began to migrate to the area’s fertile valleys and the forested mountains surrounding them.

The arrival of non-Tai people is peripheral to the establishment of the Muang. It is this disconnect between the conventional discourse and the oral traditions of the non-Tai people that suggests the need to unravel the history of the muang and question some of the basic assumptions that underpin it.

Grabowsky’s (2003) articulation of an “indigenous” history of northwestern Laos has helped move us away from the simplicity of dominant historical discourses of nation-state formation. Grabowsky has worked to peel away the Western colonial narrative to free up a different level of historical storytelling. In his analysis of the Chiang Khaeng Chronicle, the local records of a Tai Lue principality on the northern reaches of the Mekong, not far from Luang Namtha, Grabowsky brings the dilemmas and decisions of the Tai Lue rulers of the muang to the forefront, giving agency to the local political players in the theatre of struggle between the French and British in the late nineteenth century. In doing so, he demonstrates that these local figures “were by no means exclusively ignorant victims” of the negotiations dominated by the colonial powers, but rather they “tried hard to manipulate the contradictions between the two main European colonial powers to secure the very survival of that state” (ibid., 62). His exploration of the Tai Lue leaders’ strategies is an attempt to understand what the process of bringing an area under the colonial blanket meant for the life of the local population, giving voice to an important alternative narrative of the colonial experience.

Working with the same Chiang Khaeng Chronicles, Grabowsky and Renoo (2008) uncover a wealth of information about the Tai Lue, their socio-economic situation and their political strategies. There is valuable detail about the relations between the Tai Lue and the other groups living on the outskirts of the muang. The power structure of the Chiang Khaeng polity was determined by symbiotic relations between the politically dominant Tai Lue, who settled in the valley of the Mekong and its tributaries, and the autochthonous hill tribes that provided valuable forest products, precious metals, and agricultural labor. Importantly the Chronicle mentions that the Tai Lue were often a minority in the region they ruled. For example, the composition of the Tai Lue leader Chao Fa Dek Noi’s young followers—five Tai and seven Kha (non-Tai autochthonous people, usually referring to speakers of Mon-Khmer languages)—illustrates demographic balance of the Chiang Khaeng polity (Grabowsky 2003).

The Chiang Khaeng Chronicles are written by the Tai Lue, the local Tai elite of the muang, and Grabowsky correctly recognizes this fact without hesitation. While he undertakes to highlight the impacts of policy on people in the marginal areas of the would-be colony, there is still a large sector of society that remains voiceless. Our knowledge of these other ethnic groups comes primarily though the observations and interpretations of outsiders, Tai and Western, who bring their own frameworks, biases, and objectives to the writing of history. The Tai Lue understandably write history to make it their own, and that places non-Tai peoples in a certain position within the Tai political and social imagination. While this analysis is of high value, it still leaves us wondering what the marginal majority of non-Tai groups in the muang experienced in this process and how they acted on other contemporary social forces.

Further Layers of Autochthonous Historical Narrative

It is well established in the historical records of the Tai Lue and other Tai groups in the area that relations between Luang Prabang, Chiang Mai, Kengtung, and Chiang Hung during the period of the sixteenth–twentieth centuries were dynamic, dramatic, and often tumultuous. Trade routes crisscrossed the area of northern Laos while armies struggled to secure political power over local people. The Namtha river provided access from the Sipsong Panna territories to the Mekong and down to Luang Prabang, but river travel was difficult on account of rapids and seasonal fluctuation in water levels. Another more convenient overland trading route from Chiang Khong to Chiang Hung passed through Muang Luang Phukha, as Luang Namtha was previously known, and Viang Phukha, over the mountains and down to the Mekong. Lue and Shan (Tai) muang established on the northern reaches of the Mekong were key intermediary actors in the local politics and trade between the larger Tai muang of the region. Not far to the north-east of Muang Luang Phukha is a chain of salt fields which provided an important economic commodity traded widely across the region until the 1980s. Discussing these historical dynamics in detail, Walker has made a major contribution by dispelling the myth of isolation in this area of the upper Mekong (1999).

Évrard (2006) has described the historical and social background of northwestern Laos from the perspective of the Khmu. The Khmu of the right bank of the Namtha were integrated into the trade routes that passed through their territory, while the Khmu of the left bank were more isolated from this traffic. The river was also a border among the Khmu, with the right bank Khmu associated with the kingdom of Nan, and the left bank with Luang Prabang. One group of Khmu, known as Khmu Yuan, were concentrated around the muang of Vieng Phukha, and as the ethnonym suggests, have a close historical relationship with the Yuan (Nyuan) (ibid.). This area prospered in the seventeenth century and was an area of Tai political influence, as attested by the Buddhist structures that date from this period. The Khmu-Nyuan relationship in this period may have been of the classic muang model, with the Tai wielding power from the narrow valley area, but incorporating the Khmu in their upland landscapes through ceremonial and economic relationships (Grabowsky 2003). The local Khmu-Nyuan relationship was further reinforced by the Muang Vieng Phukha’s relationship with the principality of Nan, a larger center of Nyuan political power.

The Tai records also note that the majority of the population in the area was Mon-Khmer. People speaking Khmuic and Palaungic languages inhabited the mountainous regions, but they came into increasingly intense contact with Tai cultures as the Tai muang expanded. Linguistic evidence from Khmu suggests that Mon-Khmer groups began borrowing from Tai languages at an early time, a phenomenon that indicates high levels of bilingualism among mountain people (Downer 1989–90) across the mountainous areas. The implications of this cultural contact are evident in the Khmu, Rmeet, Samtao, and Bit languages still spoken in the area, which contain a high level of Tai lexical material. It is difficult to put a date on the start of this interaction, but it is likely that the linguistic contact became significant with the founding of small Tai muang in what are now the northern areas of Laos, Vietnam, and Thailand. A somewhat more recent development is the evolution of tones in Samtao and several varieties of Khmu, which were originally not tonal but developed tones partially as a result of contact with local Tai languages that have tones. This deep cultural influence requires the presence of social networks that were much denser than those implied by simply symbolic roles in ritual or occasional trading relations.

Évrard states that the ritual formalization of the relations between Tai and Mon-Khmer groups determines the “structure interethnique” that provides the basic framework for considering the muang and its relations with the margins (Évrard 2006, 77). Indeed, it is this ceremonial relationship—the precarious balance of appropriation and integration, denial and recognition—that has captured the analytic attention of many scholars of the region. However, Évrard shows in his own study that the micro-dynamics, such as the practical details of livelihoods, soldiering and river trade, of the Tai Lue-Khmu relationship require a rethinking of the assumptions about dependence and dominance that are implied in models based on structure. Furthermore, insights on the cultural processes associated with the appearance of villages that are mixed Tai-Khmu—or even Tai villages that became Khmu call for a finer resolution of analysis. Particularly interesting is his assertion that when looking at this level of interaction, the ethnic group often loses its usefulness as an analytical tool, because here the subgroupings4) within society play a more important part in determining the outcome of power struggles and development dilemmas.

Re-examining the Formation and Transformation of a Muang

Condominas (1990) made the important observation that the structure of the muang has typically been the overwhelming concern for scholars interested in the history of Tai people and their neighbors. Reflecting on his own fieldwork on the interethnic and interclass relationships between the Tai Dam, Laha, and Khang in a muang of northwestern Vietnam, he expresses frustration with the standard approaches.

Though this picture conveys, it seems to us, the structure of a muong [muang] in the modern period, it cannot convey the internal dynamics that move this society. In this region, as elsewhere, ethnographic descriptions give an impression of a static society which, paradoxically, reinforce the same picture given by accounts of conquests that historians provide. The interpretations of these two types of data, although throwing light on each other, allow only a vague suggestion of the internal dynamics of a present-day muong. (ibid., 69)

Okada (2012) has further challenged the scholarship on muang in northern Vietnam, drawing on texts written in Han Nom and old Tai scripts dating from before the colonial period. He uncovers detail about muang in Thai Bac, described as having two centers of power—one Tai Dam (Black Tai) and one Tai Khao (White Tai)—that interacted with each other. The governance of the muang was based on several sources of authority. Rather than a center-periphery model for the muang, he proposes a more dynamic and networked system of relations among many different peoples. Furthermore, the area is high in “cultural hybridity,” given the multiple ethnic groups living in close proximity. He concludes that ecological conditions, influxes of immigrants, and linkages to the regional economy were critical in creating the structures that were subsequently identified by scholars such as Condominas in the colonial and post-colonial periods. In other words, the muang political structure was embedded in the local geography and ecology and situated within a particular historical context, and was not the product of any one ethnic group. Moreover, the “Tai Dam” model was shown to be a mix of Tai Dam and Tai Khao, while the basic decentralized structure contradicts the notion of concentrated power. However, the reliance on written records means that the non-Tai people fade out of sight quickly, and we are left wondering again how relations with and among autochthonous peoples were created and recreated over time, and what their role may have been in matters of the muang.

The heritage of ethnolinguistic diversity characterizing Luang Namtha, in which the Tai speakers have always been a decisive minority, begs the question of how a Tai-style muang was formed amid such situations of extreme diversity. What we know from the Tai and other records suggests that this ethnic complexity was probably the norm in the region. The data presented here illustrate how uplanders created niches within the development and governance of the Luang Namtha muang, shaping the political, economic, and cultural landscapes that overlay the area today. The need for recognition of uplanders’ agency in history has been mentioned with increasing frequency (for example, Journal of Global History 2010), but local narratives demonstrating the historical dynamism of this agency are still critical for unloading the baggage of state-written history. The oral traditions discussed here tie together the founding and expansion of the muang with the recent socio-economic development of Luang Namtha. Remembering themselves as founders of the muang, the non-Tai people see continuity in their political and economic engagement with the local center of governance within a local society that is dominated by Tai narratives.

Luang Namtha Demographics: Dynamic Complexity

Now a growing urban center of some 45,000 people, the expansion of Luang Namtha’s economy is driven by ever increasing levels of trade and investment. The city, which is the provincial capital of Luang Namtha province within the Lao Peoples’ Democratic Republic, lies less than an hour’s drive from the Chinese border, along the national road R3, which was upgraded in 2004 as part of the Asian Development Bank’s Greater Mekong Sub-region Program to increase transport links among the countries in the region. Across the border is Sipsong Panna, China’s rubber production area. Rapid growth in demand for latex in China has drawn Luang Namtha and Lao national agricultural policy solidly into transboundary product chains, transforming the landscapes and livelihood strategies of the local people. Despite the widespread conversion of forest fallow to rubber trees, visitors to Luang Namtha, numbering almost 250,000 in 2009 (Lao PDR, Government of Laos 2009), enjoy trekking in the Nam Ha National Protected Area and visiting villages of the many local ethnic minority groups.

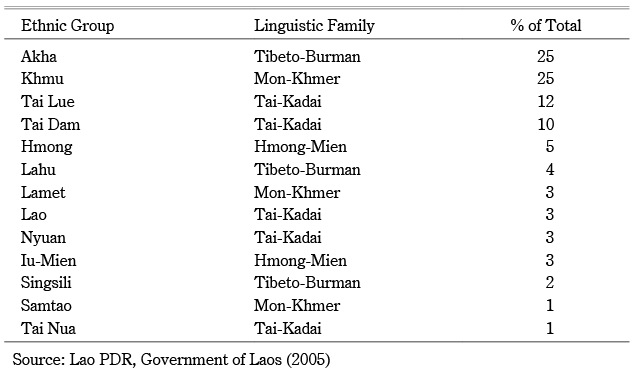

The town of Luang Namtha shows great ethnolinguistic diversity, and the population of the town itself reflects the influx of diverse people since the early 1900s. Of the total provincial population of approximately 145,000 people (2005), nearly 45,000 live in Luang Namtha town. Luang Namtha provincial census data from 2005 is broken down by ethnicity in Table 1.

At the provincial level, the population breaks down into roughly 30 percent each for Tibeto-Burman, Mon-Khmer, and Tai-Kadai. Hmong-Mien and other small groups constitute the last 10 percent, while ethnic Lao account for only 3 percent of the population. These figures roughly reflect the ethnolinguistic situation documented by Izikowitz ([1951] 2001) in the 1930s, and by Halpern in the 1950s (quoted in Pholsena 2010).

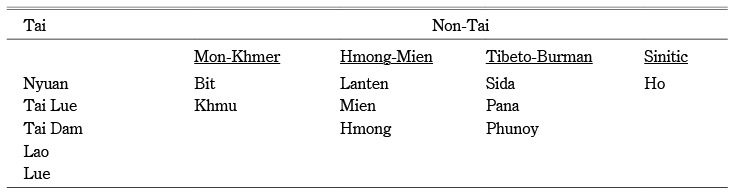

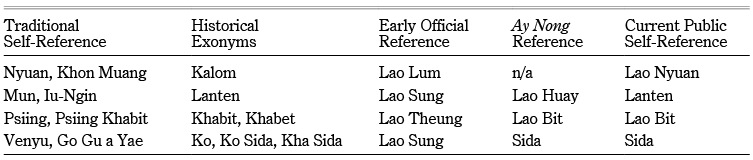

The data and analysis presented here draw on narratives given by non-Tai people around the town of Luang Namtha. The data comes from extended interviews with and narratives given by local people in the Lao, Mun, Sida, Bit, Khmu, Hmong, Pana, and Chinese languages. Table 2 summarizes the main ethnic groups involved in the paper.

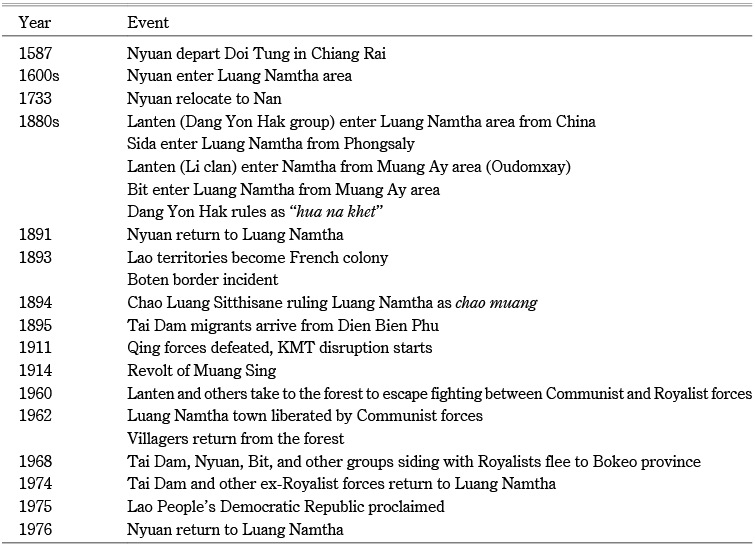

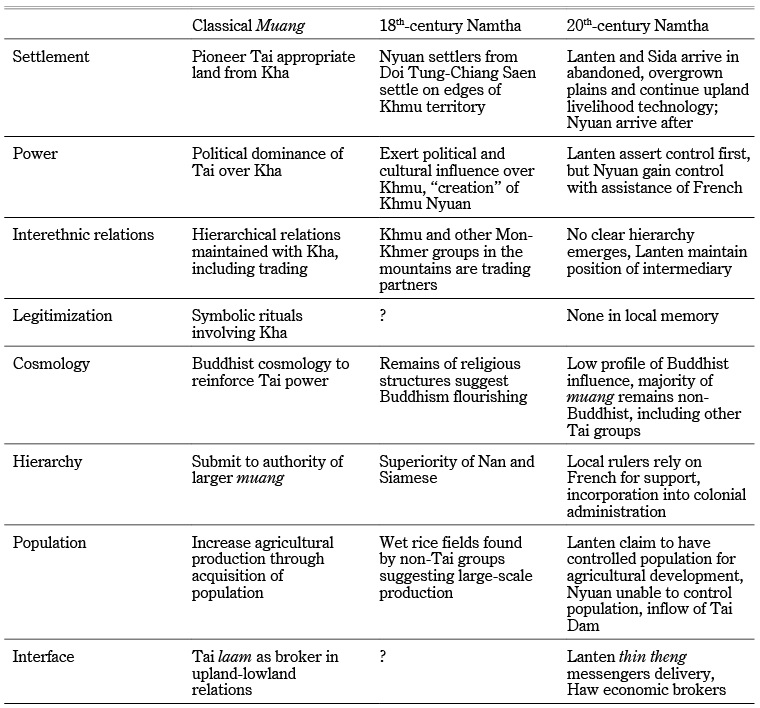

The events discussed in the following section are summarized in Table 3. First, we discuss the settling and opening of the muang, focusing on the role of a local leader of the Lanten ethnic group. Next we explore description of the governance of the muang after its founding, with an eye to uncovering some sense of the economic and political interactions between the muang peoples. This is followed by a look at the role of the muang and its people in the establishment of the current political order, including border demarcation and the Communist revolution. Finally, the analysis is brought into the current socio-economic development context. The presentation of this data is concluded with discussion of how identities are being redefined based on this alternative historical narrative, even as it is colored by the current Lao national political discourse. We make reference to analysis of local written Tai historical texts and other Western documents for the purpose of triangulation and contextualization.

II Settling the Muang: Dang Yon Hak and the Arrival of the Lanten

When our ancestors arrived here, there was no one living in the valley basin.

Common narrative of Lanten, Sida, and Bit elders of Luang Namtha

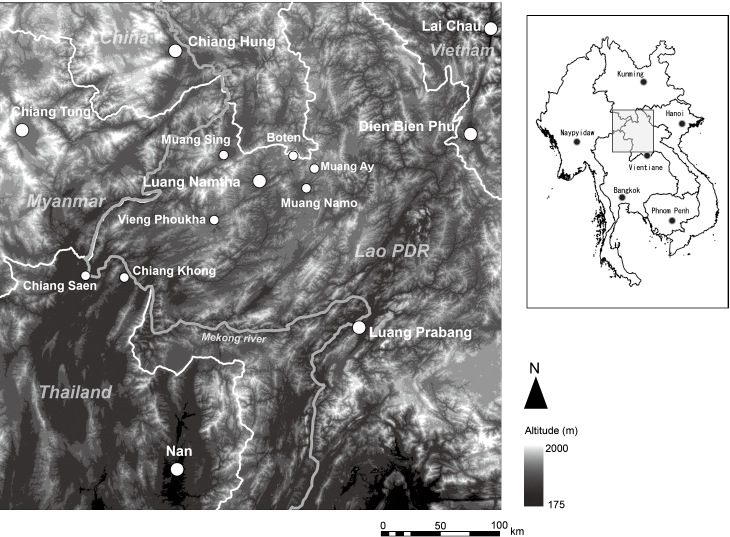

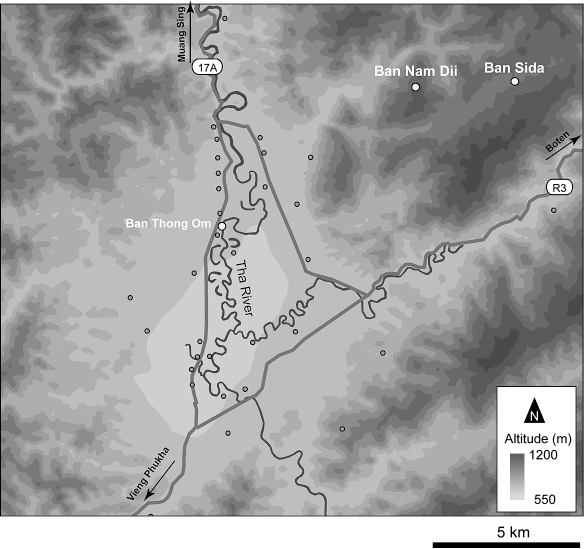

We often conceive of “minority” groups in mainland Southeast Asia as a substratum (autochthonous) or an overlay (late immigrants). The Lanten, Sida, and Bit communities living in Luang Namtha5) claim that they arrived in the area in the late 1800s. There are no specific dates, but genealogies given by village elders confirm this general timeframe. What is clear from all of them is that their ancestors migrated from different directions in search of safe and productive land. Fig. 1 shows key villages in the Namtha valley. Namdii, founded in the 1960s by the Lanten but originally the location of a Bit settlement, is a village in which Lanten and Sida currently live together. This village is where the majority of this paper’s narrators live. Ban Sida has a larger Sida population, and is the last of many moves the Sida have made since arriving in the area in the late 1800s. Elders in this village have provided supplementary information as well. Thong Om is the site of the original Lanten settlement discussed here.

Since at least the early 1800s,6) a group of Lanten7) had been living in the Sipsong Panna area of the Sino-Lao border, farming and hunting. The Lanten currently live in Laos, Vietnam, and China, and speak a Hmong-Mien language called Mun, which is closely related to the better-known Mien (Yao) language. Also, like the Mien, the Lanten have been practicing Daoism since perhaps the eleventh century (Pourret 2002). Their rituals are performed with the assistance of books written in Chinese characters. Chinese literacy remains an important, but increasingly threatened, aspect of Lanten culture, linked not only to rituals but to traditional singing and other forms of cultural knowledge as well. The spoken Mun language has also been heavily influenced by generations of contact with Chinese. Nevertheless, the Lanten are known in contemporary Luang Namtha as one of the most culturally conservative groups, preserving their homespun cotton and indigo-dyed clothing, patrilineal clan-based society, and written language. The exonym “Lanten” comes from the Chinese word for indigo (landian 蓝靛), and this product has been so important to them that it has been suggested that they are called Lanten not only because they wear the indigo-dyed clothes, but also because they had a monopoly on the indigo market long ago in China (Takemura 1981).

One day this group of Lanten followed their game over the mountains into the area between Muang Sing and Muang Luang Phukha. Pleased with the environmental setting and encouraged by the low population density in the region, they moved into the Namtha valley, which they found to be empty. The Lanten took up residence as a large village along the eastern bank of the Namtha river and began to clear the vegetation for swidden farming and livestock. The thick forest was home to many animals and hunting continued to be an important element of their livelihoods. The Lanten leader, Dang Yon Hak 鄧玄斈, oversaw the establishment of several Lanten villages in the lowland area, but the main settlement was at a village called Thong Om, located just south of the present-day airport. At around the same time, a small group of Sida8) people arrived and started a settlement across the river, farming swidden fields and raising livestock. The Sida and the Lanten “built a road between their villages” and traded rice and cloth. It is interesting to note that the motivation for the migration is rather different between the Lanten and Sida. The Lanten insist that they were not persecuted in Chinese lands and were not fleeing from war; rather, they made conscious decisions based on consideration of their economic needs and potential for self-governance in daily matters. The Sida, on the other hand, tell that they were suffering an unbearable tax burden, which they paid in non-timber forest products such as lac, edible insects, and other special herbs and spices.9)

At around the same time, another group of Lanten was leaving the confluence of the Mekong and Khan rivers just outside Luang Prabang. This group also tells a story of entering into Lao territory, in this case from Lai Chau in Vietnam, during one of their hunting trips. Fleeing from turmoil and disease in the Sipsong Chu Tai, they made their way down into the Mekong basin by way of southwestern flowing tributaries. But life near the Lao royal capital was not agreeable, largely because of the shortage of land for swidden cultivation. The group then moved northwards to Muang Ay, in the current-day Namo district of Oudomxay province. The Li clan was the dominant force in this Lanten community and oversaw the establishment of a more permanent settlement in their new home. The Lanten settlement fell within the political influence of a small Tai muang centered around Muang Ay, but which also included a large Khmu population, several villages of Bit and Mien, and a small population of Tibeto-Burman groups. Lanten textile production, important in trade among local groups, had made them an important factor in the local economy.

The leader of the Li clan asserted himself as a figure of power among these upland groups, providing an interface between the non-Tai upland people and the Tai rulers in the muang. With the death of the Li leader, his two sons—Li Yon Siu 李玄照 and Li Yon Sang 李玄璋—traveled to Luang Prabang with an entourage to consult with the Lao king and the French authorities on how to handle the succession of the hua na khet (Lao: subdistrict chief) position. It was decided that Yon Siu, the elder brother, would assume the position of upland leader. In recognition of his local economic and political influence, he received the title of saen luang (Lao: leader of 100,000) and returned to Muang Ay as “the administrator of the mountain people.”10)

The Namo Lanten also built relations with the Bit, who had arrived recently as refugees from the Cheuang Wars of the 1880s.11) The Bit were spinners of high-quality thread from the Lanten cotton but apparently did not grow their own cotton. The Lanten recall how as many as 10 Bit households could be “attached” to a Lanten family, providing dedicated spinning services. Most Bit families had members who spoke Mun (Lanten), and many of the influential Lanten were conversant in Bit. The Luang Namtha Bit also recall their relationship with the Lanten, and confirm the importance of cotton in the exchange between the two groups. They also confirm widespread bilingualism. Bit oral narrative remembers their weak position in relationships with other larger, more powerful groups. For the Mon-Khmer groups of northern Laos, this would usually be assumed to refer to their position of subjugation to the local Tai rulers, but in this case there is some more recent evidence for some form of indentureship with the Lanten. In any case, it seems clear that the Lanten had established a position in the administration of the Ban Ay-Ban Khouang muang and carved out a niche for themselves in the local economy.

When Yon Siu died, the order maintained by the Lanten in the Muang Ay mountains was significantly weakened. By this time, Dang Yon Hak, the Lanten leader in Luang Namtha, had also established relations with the French in Luang Prabang and received the title saen luang. He made frequent trips to pay tribute and collect budgetary resources for administering the Luang Namtha area, passing through Muang Ay. Seeing that the Muang Ay Lanten had fallen into some disarray, he invited the Li clan to lead the Lanten to Luang Namtha and join them in the valley region. With the low population density and lack of manpower, Dang Yon Hak needed the Muang Ay Li clan to help him develop the basin. The prospect of having an influential leader in the form of Dang Yon Hak, in addition to the abundance of land, led the Li clan to accept the invitation and migrate to the Luang Namtha basin. Now there were several Lanten villages along the river, and the cultivation of upland rice, cotton, and other upland crops, along with raising cattle and buffalo, became the mainstay of the basin economy.

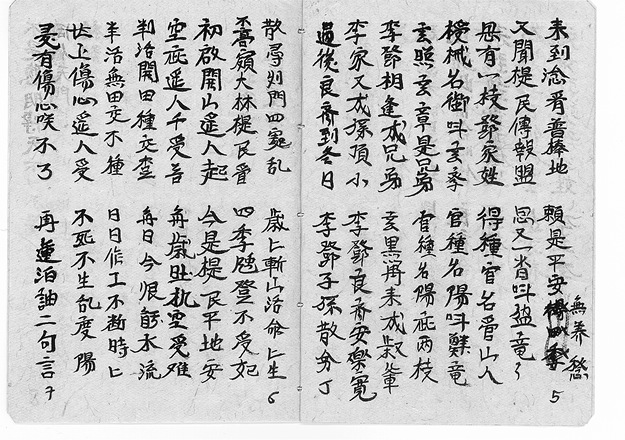

The Lanten oral history discussed here has also been written down in a traditional song format. Fig. 2 is one page from a song composed in 2011 by a Lanten elder, describing the arrival of his people in Luang Namtha. The Mun title of the song is Thek Tjek Iu Mun 泰聀遙人, but the author also gave it a Lao title meaning “Short History of the Lanten in Luang Namtha.” As a member of the Li clan, the writer focuses on the position of Yon Siu and Yon Sang, and the Li clan’s decision to join Yon Hak in Namtha. His emphasis is Yon Hak’s role in bringing the Lanten together to assert themselves in Luang Namtha, an event of importance remembered by elders from both the local Li and Dang clans.

Fig. 2 Excerpt from Short History of the Lanten in Luang Namtha, written in Sino-Mun (泰聀遙人 Thek Tjek Iu Mun)

III Opening the Muang: Return of the Tai Refugees

The most powerful event in the Lanten accounts of their history in Luang Namtha concerns the role of Dang Yon Hak in transforming the Namtha basin from pa to muang. As introduced above, the Namtha basin was covered in dense forest when the Lanten and other groups arrived. Although traces of previous settlement were readily observable, establishing the new settlements required a portfolio of upland livelihood technologies including rice production in swidden fields, diversified cropping of food and fiber crops, hunting and gathering, and large livestock husbandry. Using these time-tested methods, the Lanten and Sida transposed their mountain livelihood systems onto the lowland ecology. Fig. 3 shows the current Luang Namtha basin, showing the location of the main research villages, and the original Lanten settlement of Thong Om.

The uplanders who viewed this valley were long-time shifting cultivators, and describe the Namtha valley in terms that in Tai cultural frameworks signify pa or wild forest areas, as opposed to civilized, muang valley areas. The lowland areas on both sides of the Namtha river were covered in forest. Large trees known in Lao as kok hai (a type of Ficus) were numerous in the landscape, making it an inhospitable setting. The physical labor needed to clear large areas of land was not available, given the size of the migrant groups, and it was widely believed that kok hai are inhabited by wild spirits. The presence of kok hai trees holds special importance for the spiritual aspect of the human-nature relationships that were formed there. In the Sida telling of their arrival, the kok hai plays a central role (Sida elder, male, age 62):

In the times of our ancestors, there was no heaven and no earth. There was one kok hai tree that grew up to the heavens, so high that it blocked out the sun. In the shadow of this tree, crops could not be grown and people could not make their lives. So they tried to cut the tree down. We hired 30 and 300 Akha12) to come chop the tree. We chopped and chopped, but each morning we woke to find the tree had grown back. On the tree was a large vine. We decided to cut the vine. When we had chopped through the vine, the tree fell over, killing the Akha and forming a depression. The two leaders Ca Lo and Ca Sa made the pond into a fishing area, and we had plenty to eat. We stayed at the pond and it became our home.

In this story, there is clearly an intertwining of an older creation myth common across the region, and a more recent founding of the muang. It is interesting that there is no mention of agriculture but rather fishing. The identity of Ca Lo and Ca Sa is not clear. At first, we were told that these brothers were the original Sida descendants from their first ancestor, the mythical mother Go Gue. In subsequent tellings, it became clear that they were probably Tai but are still considered to be the ancestors of the local Sida. Interestingly, the Rmeet, a Mon-Khmer group living further to the south, have a similar but more detailed myth.13) In the Rmeet telling, the falling tree kills the two brothers but lands in Thailand, which explains how the original wealth of the Rmeet was lost to the Thai (Sprenger 2006). The Sida telling is more focused on the first step of transforming the inhospitable Luang Namtha area to a settlement with direct forward links to their current lives. It also indirectly recognizes the same assertion as the Lanten story: that the mountain people were the first people to open the valley.

Faced with the practical obstacles of developing the Namtha valley plain, Dang Yon Hak took advantage of his political connections. Yon Hak paid tribute to both Luang Prabang and Nan, a logical strategy for a leader aspiring to establish his own power locally. The trip to Luang Prabang to pay taxes and collect an administration budget was relatively easy and likely facilitated by the Li clan, who had closer relations and more local experience given their previous residence near the Lao royal capital. Yon Hak also made trips to the principality of Nan, which was under the suzerainty of Bangkok. One year, returning from a large tribute mission to the Siamese king in Bangkok with a sizable administration budget, Yon Hak stopped in Nan.14) Here he encountered a community of Nyuan who claimed to have come from Muang Luang Phukha and were willing to return to the Namtha valley with him. Arriving finally in Namtha with 10 Nyuan households, they were allowed to live near their old wet-rice fields and told to rebuild their paddy fields.

The Mun phrase used for this event bu mun in dou dai taai an wa gjang, “we Lanten brought the Tai here and put them in the village” is centered around the idea of inserting outsiders into the muang. This is reminiscent of the well-known Tai phrase referring to the practice of moving people to strengthen a polity—kep phak sai sa, kep kha sai muang, “collect vegetables and put them in the basket, collect Kha and put them in the muang”15)—but with a complete reversal of roles. Moreover, the Lanten elders often use the Lao phrase phattana baan muang (“develop the polity”), a live expression in the socio-political discourse of the modern Lao state, to describe Yon Hak’s intent to use the Nyuan to open the valley up to more intensive cultivation. This is in contrast with the Lanten description of their own role, saang baan saang muang (Lao: build-village-build-muang, “establish the polity”).

The resettlement of the Nyuan was followed in 1895 by a wave of Tai Dam refugees fleeing social upheaval in Dien Bien Phu. With the valley plain gradually returning to agriculture, the abundance of land and other resources made the Namtha basin attractive to these new arrivals. Soon the Lanten found themselves competing for resources with the Tai. In particular, Lanten livestock and Tai wet rice cultivation proved to be a difficult mix, with cattle damaging crops and expanding fields encroaching on forests where cattle were grazed. Furthermore, Lanten dry agriculture was carried out in areas that were most easily returned to wet rice cultivation, and they made way for the Tai so that the valley could be developed. No doubt other social and political pressures figured into their decision as well.

IV Governing the Muang: Cultural Resources and Economic Interdependence

Scholarly concern with the governance of Tai muang, particularly with regards to the relationships between Tai and non-Tai peoples, tends to focus on structures involved in defining the hierarchy of unbalanced power relations. Insights into the modalities of interaction are harder to come by, but illustrate a multitude of relationships.

Literacy, Bilingualism, and the Creation of a Political Niche

Li Lao Da’s song stresses the fraternal relations established between the two Lanten clans. Without the joining of the Dang and Li groups, it would have been impossible to assert any sort of authority in the Namtha area. But Dang Yon Hak continued to play the role of founder, tax collector, and payer of tribute. The Lanten use a number of different terms to describe the position of Yon Hak, focusing on the broad geographic scope of his authority and his high position within the political hierarchy. The two commonly used Lao terms emphasize that he was a regional leader, ostensibly exerting some kind of authority over a large and diverse number of people:

• hua na khet (Lao), “subdistrict chief”

• chao khwaeng (Lao), “provincial governor”

Not surprisingly, both Lao terms have direct semantic links to the modern Lao administrative system. The hua na khet position was also part of the French administrative structure, although it is used more informally in local oral histories. It should be noted that these Lao terms are frequently used even when the narrative is in Mun.

There is another set of Sino-Mun terms that related to Chinese administrative concepts:

• gwen tjou 県主 (Mun), “chief of district”

• ai tjou ai gwan 做主做官 (Mun), “to be lord, to be the administrator”

• ai lu ai gwan 做大做官 (Mun), “to be boss, to be the administrator”

These terms highlight the Chinese influence on Lanten ideas of authority and administration, most directly from their own experience as a peripheral group to the areas of Han power. The spiritual world of Daoist deities is a highly structured, complex system of hierarchical political relations. In their rituals, the Lanten are continuously dealing with the bureaucracy and power politics of the other world.

Another common phrase incorporates Tai and Chinese terminology into a Mun construction:

• ai taao ai tjou (Mun), “to be the tao,16) to be the master/owner”

These demonstrate the Lanten capacity to integrate different conceptions of power into their own discourse of political organization. The use of Lao terms shows the Lanten effort to describe their participation in a Tai administrative context. Thus Lanten oral history describes the rare situation of a non-Tai ruler, himself a migrant from the mountains, manipulating his political allegiances to increase his own local power by moving people into his muang. With a hostile natural environment, shaky demographics, and the wrong agricultural technology, Yon Hak had no other choice but to control his land by controlling the movement of people.

But Yon Hak was not in control of the stronger demographic force, the migration of the Tai Dam. The large Lanten villages had to move to the foothills on the fringe of the plains. After Yon Hak’s death, it is said that his son Dang Wan Nyan took over the position of leadership, but this was not passed on to the next generation. The Dang clan’s hold on local matters started to waver, as traditional Chinese education weakened and the Li clan began to assert itself. From this point the Lanten describe themselves as assuming a second layer of administration within a political structure headed by a Tai leader. Despite the loss of executive authority, the Lanten retained administrative power within the local governance system.

Governing the muang required communication with a diverse local population, the vast majority of which was illiterate. The orders and notifications of the chao muang could easily be written down by the Lanten in Chinese and carried to upland villages, where they could be read directly in Chinese to the Tibeto-Burman and other Hmong-Mien groups (all of whom used Chinese as a common language), or translated on the spot into Lue or Khmu for the Mon-Khmer speakers. In Namtha, the Lanten leaders had a cohort of assistants, comprised of thin theng 先生 and thung thou nyan 送書人. The former would write out messages, the latter would deliver, read, or translate the messages. Details of these individuals survive in the collective memory and household records; we were told of Li Kyam Nyui, one of Yon Hak’s well-known thin theng, separated by five generations and recorded in the family genealogy book of the Li clan elder who composed the song presented above.

Having maintained close relations with the Nyuan, however, the Li clan descendants continued to play the role of public relations officer for the Nyuan chao muang, providing an interface between the ruler and the ruled. In a typical muang situation, a lowland broker (Lao: laam) would have provided the economic and administrative (tax collecting) linkage between the uplands and lowlands (Walker 1999). The laam role was usually played by a Lao, often an individual of economic and political power, and oriented towards to transactions with Khmu communities (Yokoyama 2010). Other uplanders, such as Hmong, were oriented to trading with the Haw caravans, and were thus often outside of the laam system (Halpern 1964). The Lanten do not use the word laam to describe their role in the muang; they focus on their role in facilitating communication and representing the chao muang though literacy. Lanten control of written communications indicates that they occupied a position of some power in the local political structure; their position was founded on a combination of their own linguistic and administrative skills, and their ability to maintain relations in both the upland and the lowland worlds.

But in daily life, relationships in the uplands largely depended upon oral communication. Contemporary narratives give some sense of the patterns of multilingualism that may have existed at around the turn of the nineteenth century. The Lanten, Sida, and Bit all give prominence to proficiency in many languages as a characteristic of a successful and influential leader. They themselves have typically been multilingual communities through past generations. Generally speaking, Haw (Yunnanese Chinese) and Lue were the lingua franca. Uplanders tended to use Haw with each other, while they would use Lue with lowlanders. The cultural and linguistic influence of Haw on both Hmong-Mien and Tibeto-Burman languages is evident in the current lexicons and ritual practices of those groups. But multilingualism among upland groups was also common.17)

For example, the Lanten have typically been proficient in Mien, and the Lamet and Bit have spoken Khmu. As mentioned above, relations between the Lanten and Bit were conducted not only in Lue, which would be the standard lingua franca, but in their own languages as well. Artifacts of these patterns are still visible in Namtha today, although the patterns are undergoing change.

The telling of the Dang and Li clans establishing power over the newly settled areas in northern Laos harkens back to the ancient days of their relations with the Chinese emperor in the thirteenth century. The Lanten were provided with documents by the emperor giving them permission to migrate through the mountains as they pleased, conducting their upland agriculture. The mythic origins of this special privilege originate with the Lanten descent from Pang Hu 盤古, the first ancestor, a dog, who asked them to establish and maintain stability in the mountain areas.18) During those times, the Chinese emperor was eager to settle farmers in the mountains to quell the social unrest and banditry that was prevalent, and provided official documentation authorizing the Iu-Ngin (referring to the historical ancestors of the Mien, Lanten, and other related groups) to carry on their economic activities.

The documents that were held by the Iu-Ngin were called Shan Guan Bo 山關薄 and authorized them to conduct shifting cultivation.19) These papers also freed them from tax and corvee requirements. These documents are known to exist among the Mien, and one copy of the Lu Cheng Tu Shan Guan Zhuan 路程圖山關伝 (A Record of Mountain Passes on the Route Map) was recently found at the house of a Lanten ritual performer in neighboring Namo district (Tomita and Badenoch 2011). Pourret (2002) describes how the Iu-Ngin’s relationship with the emperor condemned them to a life of mobility, but at the same time recognizes the utility of the documents in helping the Iu-Ngin retain their freedom and preserve their identity. Importantly, since these were official documents issued by the Chinese court, other administrations were likely to recognize their authority. Lemoine (1982, 12) has stated that by maintaining this mythic history, “the Yao [Mien] (and related groups) gave themselves, as it were, a bargaining counter in negotiations with the Chinese Empire.” In fact, Lemoine suggests that the “history” that is written down in these documents may be the result of a negotiated solution to a spate of Iu-Ngin rebellions.

If there is some foundation in the assertion that written language was one of the mechanisms of control used by lowland polities on upland people (Scott 2009), the Iu-Ngin are seen to have appropriated this technology of control in order to legitimize their residence in mountain areas, their shifting cultivation-based livelihoods, and their migrations. Furthermore, the possession of written language helped them to assert political power over other upland groups and make alliances with literate lowland groups. While the historical veracity of these stories is debatable, the salient point here is that the Lanten see themselves as playing a historical role mandated by the highest imperial authority. In case of Luang Namtha, there is no suggestion that Dang Yon Hak was ruling on behalf of a Chinese political force. However, the concept of ruling the mountains is clearly extended from the old mythical texts into the present, and they are very clear about the literacy.

The Lanten speak of very close relations with the Mien and Haw in this period, and Chinese literacy was a special aspect of this relationship. While many upland groups had people who could speak Chinese, proficiency in the written language was limited mostly to the Mien and Lanten. Economically, the Mien are reported to be the richest, as they were large producers of opium. Mien leaders have also been known to assert control over a wide area composed of many ethnic groups (Kandre 1967). The Haw controlled the trade networks, securing access to markets and important goods. Having established themselves as pioneers in the region, the Lanten maintained their position as a bridge into the muang administration, positioning themselves between the Tai, Kha, and Chinese worlds. Thus the commercial and cultural bonds between the Lanten, Mien, and Haw could have been a powerful force challenging the authority of the Nyuan.

Livelihoods, the Regional Economy, and Power Relations

The Nyuan quickly found themselves to be just one of three Tai groups vying for power in Luang Namtha. As late as 1936, Izikowitz ([1951] 2001) describes Luang Namtha as consisting of three villages, one each of Nyuan, Tai Dam, and Tai Lue. The Sida tell of the Nyuan migrants’ struggle to assert themselves. The narrator, a 62-year-old Sida elder from Ban Namdii, uses the pejorative ethnonym “Kalom” to refer to the Nyuan, and the term “Venyu,” which is how the Sida refer to themselves in their own language.

After we built the road to the Lanten, we met the Kalom [Nyuan]. The Kalom had just arrived in Luang Namtha and they had no food. When we saw the Kalom, they said “You, Venyu [Sida]! Do you have any rice?” We responded, “Yes, we have rice, we have more rice than we can eat.” And the Venyu said to the Kalom, “Do you have any cloth?” The Kalom responded, “We have plenty of cloth, we have more cloth than we can use for our clothes.” We said, “In that case, bring cloth and we will trade with you for our rice.” After that, we built a road between the Venyu and the Kalom. After that, a Kalom couple brought a bolt of cloth to the Venyu village and they traded for our rice. They tried to carry the rice back, but they got so much that they couldn’t carry it all. And we got the cloth we needed. The couple went back and told the Kalom villagers about it, and after that the Kalom population began to expand.

This narrative stresses the poverty, vulnerability, and lack of good judgement the Sida saw in the Nyuan. The Nyuan shortage of rice is not surprising, given the description of the overgrown valley that they found when they arrived. The Sida and Lanten were skilled swidden farmers and had no problems with food security. To this day, the Sida are known for their high rice yields. In the Sida telling of this exchange, the Nyuan population was dependent on the Sida to meet their food needs, at least in the early period after their arrival. The exchange of rice and cloth creates a mutually beneficial relationship, even as the Sida story asserts some sort of authority through their superior survival skills. But his story continues in a different direction.

Then one day, a Venyu man was boiling maize to make feed for his pigs. A Kalom man came to the village to trade and saw the maize being boiled for pig feed. The Kalom man, he grabbed the maize and started eating it. “Don’t eat that stuff, it will make you sick!” the Venyu man said. “Son, I will cook some proper food with rice for you,” he said. The Kalom man responded, “Never mind, I’m happy to eat this maize, it won’t kill me!” And he kept eating. But the Venyu man boiled rice anyway and made the Kalom man eat this good food. After finishing, the Kalom man returned to his village, but got sick and died. After that, the Kalom did not trust us Venyu anymore. They will not let us sleep in their houses any more.

Despite the Sidas’ assistance with surplus rice, the Nyuan still lacked rice and came to the Sida for help. But the Nyuan would not listen to the Sida, and a tragedy opens a rift between the two. The story is again told in the terms of economic well-being, but the fate of the maize-eating Nyuan man hints at the larger difficulties the Nyuan were facing, with the Sida being blamed for the Nyuan’s mistake.

The Muang in Local Geopolitics

These oral histories clash sharply with the Nyuans’ own representation of their return to Luang Namtha in the late eighteenth century.20) According to records written in the tham script kept at Nyuan temples, the Nyuan had fled Doi Tung in the current Thai province of Chiang Rai in 1587 to escape pressure from the Burmese. At the time, the Burmese king placed onerous tax and corvee requirements on the Lanna muang (Sarassawadee 2005). The Nyuan probably reached the Namtha valley in the early 1600s, and set up a modest muang under the direction of Panya Luang Kaansulin. The Nyuan would have established close relations with the local Khmu population who were the main demographic force in the region.

However, in 1733 they fled to the principality of Nan, caught again in the geopolitical turmoil of the region. After an absence of 158 years, they claim to have returned to Namtha in 1891, a group of 500 led by Chao Luang Kommachang Sitthisane. In their party were also two samanen, Chua Channha and Chua Nanta. They repaired the that overlooking the valley, which had been originally completed in 1628, and the wat at Ban Khone. In 1893 Laos was formally incorporated into French Indochina. The Franco-British project to maintain a buffer zone in the unpopulated areas of Muang Luang had failed (Grabowsky 2003). The Nyuan claim that they took over the rulership of Luang Namtha, which they kept only until 1918, at which time a Lao administrator was dispatched from Luang Prabang to rule on behalf of the French. When Lefèvre-Pontalis traveled through the region in 1894, the town of Muang Luang Phukha was reportedly under the control of Chao Sitthisane. He describes how Chao Sitthisane had established good relations with the Tai Lue of Muang Sing, in order to strengthen his position against the Lue of Sipsong Panna, who had tried to gain territory by moving the border marker southwards in 1893.

Reading other accounts of the region at this time, it seems that Sitthisane had difficulty with the mountain people to the north and south. The Khmu leaders in Vieng Phukha, to the south of Muang Luang Phukha, had taken advantage of the long absence of Tai rulers to strengthen their position, and resisted yielding control of land to the Nyuan (Lefèvre-Pontalis [1902] 2000). In the foothills north of Muang Luang Phukha, the Lanten and Mien were also successful in remaining outside of the direct control of the Nyuan. Lefèvre-Pontalis mentions meeting with three of their leaders, welcoming them and other migrants from their group to settle in the area, but requiring that they submit to French rule. Chao Sitthisane had complained that the Mien and Lanten maintained relations with the Tai Lue of Sipsong Panna, which made them suspicious, especially given the Tai Lue border marker power play in 1893.

The French were at this time in search of a local elite, a critical layer of local society that had to be won over in order to establish legitimacy for the colonial project. In particular, there was a perceived need to unify the diverse people of the muang. Lefèvre-Pontalis was sympathetic to Chao Sitthisane’s desire to request the ruler of Nan to release more Nyuan refugees and allow them to come to Muang Luang Phukha. But this did not come to pass, even as Tai Dam continued to arrive from the Lao-Vietnam border area. Although there were several candidates for a local leader they could support, the French were faced with the reality that there was no solid political structure that could be easily appropriated (Walker 2008). One such candidate for a local elite ally mentioned in an 1898 Report on Vieng Phukha (referenced in Walker 2008) was an “intelligent and active chief” who had been appointed by the Siamese some time before the treaty of 1893. Based on the documentation, one would assume that this refers to Sitthisane. As presented above, the Lanten narrative raises the possibility that this chief was Dang Yon Hak.

These interweaving, yet contradictory, narratives pose interesting questions. What sort of muang was evolving in the early twentieth century and who were the main individuals driving it? Lanten and Sida claim to have been the first settlers, catalyzing the resettlement of Nyuan. Perhaps, embracing dreams of restoring the glory of a past muang, the Nyuan struggled to assert themselves. In the meantime, they were displaced demographically by Tai Dam refugees, and their hopes of building a power base were eclipsed by the political reality of becoming a French colony.

V Protecting the Muang: Border Demarcation and Securing the Salt

The Lanten direct political influence declined with the death of Dang Yon Hak, although they adjusted and kept a role in the governance of the muang. However protecting Namtha from the Chinese is an important theme in the Lanten telling of their role in the muang. The most enthusiastically told story of Lanten efforts to secure Lao territory from the designs of the Chinese concerns a border demarcation. From the colonial historical record, we know that in 1893 the Tai Lue of Sipsong Panna moved a border marker into the territory of Muang Luang Phukha in order to gain control of the salt fields at Boten (Walker 2008). The Chinese were generally believed to be behind this bold move on the part of the Lue, but in the Lanten telling, it was the Chinese (Qing dynasty officials) who were directly responsible for the affront on Lao (French colonial) territory (Lanten elder, male, age 58, Ban Namdii).

In those days, the Chinese moved the border down, just above the old Sida village. The people were not happy with this. So the Chinese came to negotiate again, and there was a large feast. But the French and Chinese could not agree on the border. The Chinese would not move the border back. The salt fields of Boten were on the Chinese side of the border. So Dang Yon Hak negotiated and agreed with the Chinese like this. The Chinese would return to their territory, and the next day both sides would send a delegation. Each would lead a pig and wherever the two delegations met, that would be the site of the border. The pigs would be prepared, and it would be decided. The next morning, the Lao side woke up late and were worried that they would arrive late and the Chinese would get control of the salt. So the Lao side carried their pig on their backs, and ran up the hill. Once they passed the Boten salt fields, they sat down and waited for the Chinese to arrive. That is how we kept the border on the other side of the salt.

This story relates how the Lanten outsmarted Chinese officials, but touches on the amusing possibility that the Lao side almost missed the opportunity to secure their salt because of a late start. The story also tells of the importance of the Boten salt fields for the Lao. We first heard this story from the Sida, who claimed that they were the ones who carried the pig up the hill. The Lanten storytellers assert that they were the ones in the lead, because Dang Yon Hak was the figure of authority and the Sida were a small group without any influential leaders in the muang.

In a later episode, the Lanten save Lao territory from the Chinese yet again. After the defeat of the Qing forces by the Republicans in 1911, defeated Qing soldiers flooded into Lao territory and the security situation deteriorated quickly. There was much theft of food and livestock, as the French had withdrawn to Namo district in Oudomxay province, leaving a political vacuum. Again, in the 1940s, the Lanten helped repel marauding Guomintang soldiers, as described by a Lanten ex-soldier (male, 66 years old):

The Haw of Chiang Kai-shek’s army were numerous. The people were suffering but there was nothing to be done. Finally we decided to go get help from the French garrison in Namo district. Three hundred French soldiers came back with us, but when they got to Dong Ving, the French did not see any Chinese soldiers and got very upset with us. They said that if they didn’t see the Chinese soldiers the next day, they would eat Lanten liver for dinner. They continued down into the Namtha valley and arrived at Ban Pasak on the Namtha river. The Chinese soldiers were camped on the other side of the river. The French crossed the river and chased the Chinese back to Muang Sing and over the border back into China. Because of this, the French stayed in Namtha, and there were no more security problems.

These episodes portray a central role for the Lanten in key defenses of Lao territory. In the first story, the Lanten were able to renegotiate another chance for a beneficial outcome to the border demarcation with Chinese officials because of their intimate knowledge of Chinese culture and skills in the Chinese language. In the second story, because of their previous position within the French administration, the Lanten were able to convince the French to return to Namtha and restore stability to the region. These stories also highlight some ambiguity in the Lanten relationship with the Chinese. They are proud of their association with the Chinese culture of literacy, but at the same time they make reference to an ever-present threat not only to their own existence, but also to the well-being of their area of residence. It is worth noting that in both, the Chinese are made out to be the enemy, when in fact both the Tai Lue and Chinese contributed to the social disturbances. This is likely a manifestation of the present national discourse of borders and nations working retrospectively on the historical memory of the Lanten. Repelling a Chinese enemy allows them to retain the protection of Lao territory as the theme, while at the same time increasing the import of the actual defense by enlarging the size of the enemy.

VI Liberating the Muang: Minorities and the Communist Victory

“Together with the Khmu, the Lanten brought the revolution to Luang Namtha.”

Lanten ex-soldier describing the mountain peoples’ contribution to the Liberation effort.

The town of Luang Namtha was “liberated” in 1962, an important victory in the Communist struggle against the Royalists. Fighting over the rural and mountainous areas continued until 1986.

Lanten elders tell of their satisfaction when the French returned after World War II, as the familiar regime reestablished stability to their lives. However, they were well aware that the French had returned on different terms. The Lanten were sympathetic to the pro-independence Lao Issara message that the French would not be able to maintain their presence for much longer, and that it was better in the long run for the Lanten to participate in the establishment of a new Lao regime. A sizable number of Lanten joined the Communist Ay Nong21) forces. Many of the Lanten soldiers were young men who just had a sense that something was changing and felt that they should be a part of it. In 1964, a Lanten unit was set up in Namtha, composed of approximately 80 people, but was broken up and integrated into other units in 1968. For those who remained in the village, it was a period of hardship, as described by a Lanten ex-soldier (male, age 61, Ban Namdii).

In 1960, the Lanten of the Namdii area fled to the forest because the fighting was getting bad. Villages and rice barns were burnt, mostly by Yao [Mien] soldiers who fought for the French. We dug tubers in the forest to eat. Their leaders were Chao La and Chao Mai, and they were very strong. The Yao were stronger than the Lanten because their leaders had good relations with the KMT [Kuomintang]. They collected opium from all households and then made big sales to the KMT. We Lanten only produced opium for our own use, and we never knew how to sell it. Before, we traded our cloth for Yao paper. My father, Tan Lao San, went over to Namo to get weapons to fight the Yao. In 1962, we came out of the forest because Namtha was liberated. But there were still attacks by Yao who hadn’t fled. The Yao burned our houses. My grandfather’s official regalia were all burned. The shoes were beautiful and shiny, but they were burned. After two or three big battles, the Vietnamese soldiers finally swept out the remaining Yao.

The Lanten relationship with the Mien was for most intents and purposes destroyed by the war period. However, when the Lanten ex-soldiers speak of their time in the war, they frequently mention their close relationship with the Khmu. The main Ay Nong base in Namtha was in Vieng Phukha district, an area to the south of Luang Namtha town that is mainly Khmu. Li Lao Da recalled how Lanten soldiers, many of whom had grown up near Khmu villages and understood basic Khmu, quickly becoming proficient in the language. They tell of long periods of time in which they were alone with the Khmu, receiving little support and having very little contact with Lao soldiers.

The last of the Lanten thin theng were important in the new regime’s post-liberation political work of establishing control over the rural areas. Three of these individuals traveled around the northern part of the Namtha valley conducting public relations for the Ay Nong. The immediate objective of these efforts was to “raise awareness,” and their tasks consisted of taking messages from the Ay Nong, written in Chinese, and reading them in mountain villages, in the same manner as they had done previously for the Nyuan chao muang. In the village, the thin theng would assess who could speak and read Lao well enough to understand the message and establish a point of contact for on-going propaganda activities. The Lanten seem to have been particularly well equipped for this role, again because of their fluency and literacy in Chinese. Moreover, each spoke Lue and could read basic Lao. All could communicate in Mien and Khmu, as well. But the Lanten did not have a monopoly on the mountain propaganda work. One man of Sida-Pana parentage was another active propagandist, speaking Haw, Sida, Pana, Lue, and Khmu. Without these multilingual message-bearers, the Ay Nong were limited in their access to mountain communities. Such a combination of linguistic capacity and ethnic minority identity seem to have been key factors in convincing upland people to support the Ay Nong forces.

The role of ethnic minorities in the Communist struggle has been debated. There is some sentiment that the minority groups were crucial to the liberation of the country at the local levels (Pholsena 2006). In this interpretation, the Lao avoided much of the actual fighting and took orders from an elite that was either Vietnamese or heavily influenced by the Vietnamese. Evans (2003) has argued that the role of the minorities has been overestimated, and that the Lao were much more engaged on the ground than is commonly believed. It is interesting that the Lanten account of the liberation of Luang Namtha places the Lanten in close quarters with the Khmu, who formed the vast majority of field revolutionaries. The Lanten are proud of their role in the liberation of Namtha, and by stressing their close collaboration with the Khmu revolutionaries, are able to distance themselves from those who did not side with the Ay Nong, particularly the Mien.

VII Developing the Muang: Rice, Rubber, and the Road to China

After the Tai Dam villages that had sided with the Satu (“enemy,” Royalist forces) fled to Bokeo in 1968, a number of Lanten and Sida farmers moved into the plains to cultivate wet rice in the abandoned fields. The new government was keen to increase rice production as quickly as possible, and they encouraged the Lanten and Sida. Technical assistance was provided by the few remaining Tai Dam households. Over the next five years, more farmers from the hill villages joined. In this way, the Lanten took up the task of feeding the newly liberated muang, producing irrigated rice and participating in caravans to deliver food and supplies to the soldiers still fighting to the south of Namtha until the Tai Dam began to return in 1974. Despite their revolutionary contributions, the Lanten had no choice but to retreat to the foothills again, where they applied the newly learned technology to open paddy fields along the streams running through the village.

Luang Namtha now leads northern Laos in rubber planting (Lao PDR, Government of Laos 2011). A rubber boom has swept much of the country, and rubber is now a national economic development priority for the government. A Hmong village on the edge of Namtha town has established itself as a leader in rubber planting (Chantavong et al. 2009). The Lanten, Bit, and many Sida have also decided to make the shift to rubber production as their main livelihood activity. Namdii village was the first to make the investment among the Lanten. Their first requests for assistance from the local government were denied, but they soon established a relationship with Lanten in China and gained access to the information, technology, and planting materials they needed. What is interesting about the start-up of the Lanten rubber operations is that it was catalyzed by the participation of several village leaders in a joint Mien-Lanten cultural festival in China, not influence for their Hmong neighbors. The Namdii elders traveled to China to take part in a traditional singing event and became acquainted with Lanten of the same clan. The Chinese Lanten were workers on rubber estates and were invited by the Namdii village headman to travel to Laos to help them start planting. Not only did the Lanten obtain critical information and technology from China, but their kin in Yunnan came to invest in their operations as well.

The Bit have also begun planting rubber in their fallow fields along the road to the Chinese border. The roadside areas were first planted by provincial officials who had their own contacts with buyers in China, but the Bit were able to make contacts with Chinese technicians who were stationed next to their village during the building of a rubber processing factory. Four individuals from the Bit village were trained at the factory, and one enterprising man struck up a friendship with a Chinese foreman who had a range of small business operations in Luang Namtha. After doing small jobs for the Chinese man, he formed his own informal contracting operation and began to supply technical support to rubber planting operations in Muang Sing. From there he expanded to providing technical support to the establishment of other cash crops such as bananas and sugar cane, both of which are extremely popular in the northern areas of Luang Namtha province. All of these activities are geared towards the Chinese market, and he even takes his crews to do jobs in China.

These are just two cases of local development initiatives by upland people who live on the edge of Namtha town. Although the scale of their operations is small, they are shouldering much of the risk of investing in the cross-border market linkages that drive the Namtha economic boom, dealing with an uncertain market, difficult price negotiations, and unfamiliar techniques. It is still too early to say what the outcomes will be, but first indications are that rubber is generating income for local people, thus contributing to the most important development objective of the country. There are no statistics summarizing rubber by ethnicity, but our surveys along the main transport artery R3 show that rubber has become the dominant element of livelihoods in many ethnic minority villages. Cross-border economic activity at this small scale has been a major factor in the local economies of northern Laos, and is often driven by ethnicity, clan, and other kin relations.

VIII Redefining Muang Identities: Ethnonyms, Solidarity, and Social Hierarchies

All ethnic groups are officially placed on an equal footing in the 1991 Constitution that defines Laos as a multi-ethnic nation. In this scheme, the Lao themselves are included as an ethnic group, and reference to the ethnic diversity of the country is made through the term bandaa phao (all ethnic groups). The central ideology of this thinking is solidarity among all groups, and there is no concept of “minority” or “indigenous” groups in the country. A three-way system of ethnic classification—Lao Lum (lowland Lao), Lao Theung (hill Lao), and Lao Sung (highland Lao)—which had existed since French colonial times was abandoned and replaced with a more nuanced classification based on ethnolinguistic characteristics in 1985. Lao Sung and Lao Theung are now considered to be politically inappropriate, with the official policy being to call ethnic groups by specific names, prefixed with the term phao. This is, however, not an easy solution because groups are known by many different names. It is interesting to note that in everyday conversation in Luang Namtha, Lao Sung has come to mean Hmong, while Lao Theung refers to Khmu. One can consider this as coming full circle to something resembling the old, now unacceptable terms Kha (Khmu) and Meo (Hmong), only with less social stigma attached. In Luang Namtha, the revision of ethnonyms has been an interesting undertaking reflecting the positions of different groups in the historical social landscape.

The Lanten, previously Lao Sung, are now known by the names Lanten and Lao Huay. The former is from a Chinese word meaning “indigo,” a reference to their traditional dyeing. In everyday conversation, Lao Huay is commonly heard. This name was given to the Lanten after the Communist victory in Luang Namtha, as recognition of their preference for living along the streams at the edge of the town. When using their own language, the Lanten call themselves Mun (person) in the spoken language, or Iu-Ngin in the literary language. All of these names are heard in the village, but the use of Lanten at the 2012 Lunar New Year’s celebration, an official event at which provincial officials were present, suggests a preference for this name when dealing with others.

The Bit were originally known in Laos as Khabit or Khabet, which contains the unacceptable Kha element. After the liberation of Luang Namtha, the Bit were also given a new name, Lao Bit, which tried to bring them more comfortably into the Lao polity. Currently, Lao Bit is the common official self-reference, although Khabet is heard regularly in the village. In their own language, the Bit call themselves Psiing, Psiing Bit, or even Psiing Khabet. Psiing means “person” in the Bit language. In interactions with other ethnic groups, the Bit prefer to be known as Lao Bit, as it emphasizes their identity as separate from Khmu. This is because the Bit were officially grouped with the Khmu as Lao Theung until 1985.

But the most interesting ethnonym dynamics in Namtha are demonstrated by the Nyuan. Despite being a Tai-speaking group that “should” be at the top of the muang social hierarchy, they are in the process of asserting a new name for themselves. The Nyuan have typically referred to themselves as Nyuan, Tai Nyuan, or Khon Muang (people of the muang). In official policy, they have always been known as Nyuan or Yuan (Lao PDR, Institute of Ethnicity and Religion 2009). In their own historical documents one finds Yuan, and this is also the name used by Europeans visiting the region at the turn of the nineteenth century. However, the Nyuan are known as Kalom among the non-Tai groups, as well as among the Tai Lue, Tai Dam, and Tai Daeng. To the Nyuan this name is disparaging, although the etymology of the word is not clear, and they now prefer Lao Nyuan. The addition of “Lao” in front of a local ethnonym legitimizes a specific ethnic identity within the larger social landscape of the Lao nation. It is somewhat remarkable that the Tai group that is supposed to have founded the settlement would need to make a specific assertion of their Lao-ness, much in the same way that non-Tai groups have done in recent years.

The renaming project is part of a larger effort of the Nyuan aimed at overcoming the stigma of having sided with the Royalists during the struggle years. In 1968, after the final “sweeping” of resistance forces from the Namtha area, there were only five Nyuan households remaining. The rest had fled to the Thai border at Bokeo. In 1976, a proportion of the Nyuan were sent back to Namtha town, returning as part of the defeated enemy. While the official policy was to reintegrate them back into local society, the post-liberation years were filled with a significant amount of distrust for all of those who had escaped to Bokeo. In 2007, the Nyuan submitted a codification of their social institutions to the province for approval. The document is called “Establishment of the Traditions of the Lao Nyuan.” In the Lao title, the ethnonym is phao Lao Nyuan. It includes the word phao, which is used before ethnonyms in official references. The document spells out Nyuan practices on marriage and management of other social relations in the community including specifications on sanctions for individuals who do not conform. These traditional aspects of Nyuan culture are, of course, written to be in line with Lao law, demonstrating the legitimacy of their traditions and their contribution to the cultural fabric of the nation state. There is a 10-person Committee for the Management and Promotion of Lao Nyuan Culture, responsible for implementing the document in the Nyuan community. Thus the Nyuan have re-named themselves, placing themselves within the official system and distancing themselves from an old exonym associated with unacceptable local history.22)

The statements of ethnic and political affiliation seen in the shifting landscape of ethnonyms highlights the complexity of intergroup relations in Luang Namtha. Table 4 summarizes the contestation of ethnonyms in Luang Namtha.

Pholsena has argued against the “the apparent immutability of these two oppositional figures, the Majority and the ethnic minorities” (Pholsena 2006, 219). The four groups discussed in this paper employ differing identification strategies. The Nyuan and the Bit have taken up the “Lao” identifier to emphasize their commitment to being good Lao citizens, perhaps in an effort to discard the political baggage of having been on the wrong side of the revolutionary struggle. The Sida and the Lanten, both of whom remember themselves as founders of Luang Namtha, have not taken a Lao prefix before their ethnonym. Although the contestation of ethnonyms is clearly done in the immediate context of post-1975 nationalism, the longer history of interethnic relations in the early days of the muang have clear bearing on the directions of these efforts of expression.

IX Discussion: Re-exploring the Wide World beyond Structure

These local narratives leave us with questions about how to interpret the Lanten assertion of power and its place within the historical development of the muang of Luang Namtha. Did Dang Yon Hak’s efforts to assert Lanten authority result in a muang that was fundamentally different from others? It is the modern-day muang and its link to the muang of the past that concerns us here. Stuart-Fox (2002, 11) has stated: “the discontinuity of central political structures was overcome by the continuity of political culture based firmly at the village level, anchored in the socio-religious Lao worldview.” He goes on to remind us that the major polity building (and rebuilding) efforts of the Lao kings was to align the muang with the Lao mandala. Our look at the formation and transformation of Luang Namtha highlights some difficulties in generalizing a muang model, both in terms of the centrality of the Lao cultural element and the continuity that is needed to support it. Table 5 below considers some of the differences between the “classic” muang, the early (first) muang, and the later (second) muang. This summary table shows that there are significant differences between the first and second muang.