Seeking Haven and Seeking Jobs: Migrant Workers’ Networks in Two Thai Locales

Nobpaon Rabibhadana* and Yoko Hayami**

*ณพอร รพีพัฒน์, Graduate School of Asian and African Area Studies, Kyoto University, 46 Shimoadachi-cho, Yoshida Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606–8501, Japan

**速水洋子, Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University

Corresponding author’s e-mail: yhayami[at]cseas.kyoto-u.ac.jp

DOI: doi.org/10.20495/seas.2.2_243

Thailand has seen a large increase in migrant workers from Myanmar since the 1990s. A constant flow of migrants arrive to seek refuge from dire circumstances in their homeland and/or to seek better work opportunities. They have adapted to changing state policy regarding their migrant status and work permits as well as to more immediate means of control. Previous works on this subject have tended either toward macro-level policy and economics, or more journalistic accounts of individual migrant experiences. Little attention has been paid to differences in the migrant processes and networks formed across the border and within the country.

In this paper two locales, one on the border (Mae Sot) and one in the interior (Samut Songkhram), are compared based on interviews conducted with migrant workers on their mode of arrival, living and working conditions, migrant status and control, and how they form networks and relations within and across the border. By comparing the two locales, rather than emphasize how the state and geopolitical space define mobility we argue that transnational migrant workers formulate and define their space through adaptive networks in articulation with geopolitical factors as well as local socioeconomic and historical-cultural dynamics. The dynamics among macro policies, micro-level agency of migrants, and meso-level networks define each locale.

Keywords: migrant worker, Thailand, Myanmar, family, state policy, social network, state formation

I Introduction

There has been an increase in the number of migrants from Myanmar to Thailand since the late 1980s,1) spurred by Thailand’s rapid economic growth. Interviews conducted in the lowland Karen State, in the township of Pa-an, reveal that in the late 1980s the direction of migration among labor from Myanmar switched from westward toward Yangon to eastward over the mountains into Thailand (Hayami 2011). Each household had at least one member working in Thailand—in construction, fishery, agriculture, or manufacturing, or as domestic help. Migrant labor from Myanmar (as well as Cambodia and Laos) filled jobs that Thai workers considered “dirty, dangerous, and difficult.” The border zone may be regarded as an “economic dam,” where cheap labor keeps flowing in while their way into the interior is blocked. However, migrant workers also make their way into interior prefectures where working conditions as well as social and cultural contexts differ markedly from the border.

In this paper we study migrant laborers in two locales, one on the border (Mae Sot) and one in the interior (Samut Songkhram). By comparing the two locales, rather than unilaterally arguing on the manner in which state and geopolitical space define mobility, we suggest that transnational migrant workers formulate and define their space through adaptive networks in articulation with macro-level policies as well as local socioeconomic and historical-cultural dynamics.

Studies on migration have been carried out in the social sciences for over half a century, either in terms of rural to urban domestic migration, or the migration of Europeans and Asians to North America. The recent increase in migration to destinations formerly deemed “sending” countries has spurred renewed interest in the subject. Various approaches from multiple disciplines, beginning with the economic push and pull theories or dual labor market theory, world systems theory, and historical-structural analyses, have been employed to understand the phenomenon. It has become increasingly clear that a far more integrated perspective, which both incorporates the role of the state and pays attention to human agency, is necessary in order to view the migration systems and networks from a historical, political, and economic perspective, examining both ends of the flow and their linkages.

As a way of understanding migration, Caroline Brettell identified three levels of analysis (Brettell 2003, 2)—the macro, micro, and meso. The macro-level refers to the structural conditions that shape the migration flow and constitutes the political economy of the world market, interstate relationships of the countries involved, income differentials, the laws and practices of citizenship established by the state, larger ideological discourses, the demographic and ecological setting of population growth, availability of resources, and infrastructure. Transnational migration impacts the state policies of citizenship and sovereignty (Castles and Miller [1993] 2009), and states must regulate, control, and decide on how to deal with the influx and how to grant rights to immigrants. It is important to take note of changes in policies and regulations over time that control the entry and exit of migrants, which are affected by Thailand’s increasing demand for cheap labor.

In this regard, a key issue regarding borders and citizenship among migrant workers in Thailand is the registering of illegal migrants with work permits, a system that became institutionalized after 1992 (see next section) and which Pitch Pongsawat (2007) refers to as “border partial citizenship.” The politico-economic order is constituted as an ongoing process between state exercise of power to control the border, exploitative capitalist development, and illegal immigrant workers’ response to the situation, allowing the continued employment of migrant workers with low wages. This system contributes to the maintenance of an exploitative process. While registered worker status ostensibly grants “amnesty” to work in Thailand, workers are subject to search and street-level harassment by the police as well as exploitation by their employers, and their mobility is severely restricted.

In Pitch’s view, if “border” implies the ability of the state to demarcate the boundary, then the Thai state policy to extend the conferral of “amnesty” to provinces away from the border as a flexible way of procuring cheap and exploitable labor could be seen as a way of forming borders beyond the physical border. As the number of provinces where such amnesty was extended increased, the border expanded (ibid., 199). In this sense, the border extends into the lives of migrant workers in the interior parts of the country. Pitch’s poignant critique of state policies evaluates the manner in which macro-level policies affect micro-level responses. Despite his assertion of the “non-physical border” existing in the interior provinces, Pitch discusses only Mae Sot and Mae Sai, two border towns, and does not delve into the system as it operates in spaces other than the immediate physical border. This paper, on the other hand, looks at the practices and processes of migration both on the border and in the interior, to consider in what sense the latter is, or is not, merely an extension of the physical border.

Micro-level analysis looks at the agency, desires, and expectations of individual migrants, and how larger forces shape their decisions and actions. In her work on Filipino migrant workers, Rhacel Salazar Parreñas (2001) points out that the transnational household must be seen as part of a larger extended family across borders. Transnational households are in many cases upheld by values of mutual help and support among extended family and depend on the resilience of such bonds. They also act as conduits of information and social networks and promote the continued flow of workers. This paper studies households as units of analysis, and reveals that these units are in fact part of a network that is dispersed across the border. Coping strategies are formulated within this network by utilizing opportunities in the different localities. Thus, micro-level analysis is inextricable from the meso-level.

According to Brettell, the set of social and symbolic ties and the resources inherent in these relations constitute the meso-level. While individual migrants seek to improve their lives and secure survival and autonomy, the decision to migrate is made in the context of a network of cultural and social ties. The meso-level is the relational dimension manifest in social networks, linking the areas of origin and destination (Massey et al. 1998). The networks provide the social capital and information that enable individual choices and agency within the constraints of macro structures, thus linking the three levels.

Social networks of migrants are contingent and emergent (Menjívar 2000, 36). Yet, migration studies have too often taken for granted “place” as given and static, from and to which people move. This reiterates the state’s perspective, where mobility is the anomaly and staying in one place is the norm. Toshio Iyotani suggests that the perspective might be reversed from understanding mobility between stable places, to understanding space from the point of view of mobility and migration (2007, 4). The focus of attention on network formation at the meso-level will allow us to look at space from a non-state perspective.

In his criticism of how social science theories have been dominated by state-centered frameworks, Willem van Schendel makes a similar point regarding border zones specifically, by focusing on the flow of people, goods, and information. In order to free ourselves of this state-dominated framework, he suggests that we look not only at state-defined maps, but at the cognitive maps of those involved in the borderlands in which “pre-border” and “post-border” maps are juxtaposed with the state-defined map (Van Schendel 2005). The pre-border map constitutes the network of relationships that preexisted and cuts across the state border, recognizing the social and cultural continuities inherent in it. These relationships, in the form of kinship and trade networks along with cultural and religious communities, not only persist despite state borders, but may provide security in the face of the division brought about by state-based maps. These pre-border relationships may enable adaptations to constraints brought by the state-defined borders by the creation of “post-border” maps. One attempt to look closely at these post-border maps is Lee Sang Kook’s study of migrant workers in Mae Sot (2007), which refers to the “border social system,” challenging prevailing notions of the sovereignty and social order of the state. Lee points out how informal institutions that are unique to the border constitute the political/economic space of the border.

The layered maps, from the perspective of the people who live on the border, allow us to look at the border not as a given static place, but as a space defined by an articulation between the state border, migrant processes, and networks and relations across borders, old and new. When viewed from this standpoint, the maps overlap. Rather than take for granted state-defined maps and look merely at the flow between states, we will look at migrant spaces both on the border and in the interior from the point of view of the inhabitants of those spaces as well as those involved in the flow.

In Thailand, studies on migrant labor began with the recognition of the increase in their influx in the early 1990s. The studies can be categorized mainly into three types. The first are studies that look at the changing state policies on immigration and migrant labor in the long term (Kritaya et al. 1997; Phanthip 1997). Kritaya et al. pointed out at an early stage that Thai society did not prevent the assimilation of people from other countries; however, Thais accepted foreigners as one of their own only under certain conditions. Kritaya and Kulapa (2009) also studied the effects of the policy change in 2008 on the hiring process of workers from Cambodia, Myanmar, and Laos.

The second category constitutes studies that look at the conditions and realities of migrant workers. Some of these are statistical (Huguet and Sureeporn 2005; World Vision 2005), whereas others are more qualitative and descriptive of specific populations or issues, such as Chalermsak Ngaemngarm on the illegal Karen population in Mae Sot (1992), Sukhon Khaekprayuun on female workers in Samut Sakhon (2003), and Bussayarat Kaanjondit on unskilled migrant workers in Bangkok (2006). Nwet Kay Khine (2007) as well as Aree Jampaklay and Sirinan Kittisuksathit (2009) study remittance patterns, and Zaw Aung discusses Burmese labor rights protection and movements in Mae Sot (2010).

The third category are studies that analyze the factors that cause migration (Srinakhon 2000; Phassakorn 2004), mostly concentrating on the border situation at Mae Sot. Toshihiro Kudo focuses on Mae Sot, situated on the East-West Economic Corridor, and how industries have opted to stay on the Thai side of the border because of its infrastructure (availability of electricity, and roads that allow materials and products to be transported easily) and cheap labor (Kudo 2007).

In an integrated approach, Supang Chantavanich studies the impact of transnational migration on the border community in Mae Sot, examining the economic, social, cultural, political/legal, and health impacts of the increasing labor migration (Supang 2008). Dennis Arnold also examines the political economy of Mae Sot, with an eye on local and state-level authorities and agencies that operate to maintain the Special Border Economic Zone, the legitimizing of cheap labor and labor conditions, and how workers have coped in the face of this (Arnold and Hewison 2005; Arnold 2007).

The lens through which migrant workers in Thailand have been viewed thus far has been focused either on the border areas or on the perception that migrant workers are one marginalized category vis-à-vis state regulations. In social science discussions since the early years of the twenty-first century, there has been an emphasis on transnational space created by migrant networks (Faist 2000; Brettell 2003; Castles and Miller [1993] 2009). This has not been fully addressed in studies in Thailand, or in mainland Southeast Asia in general.2) In Southeast Asia, transnational networks are created literally across borders. The physical border itself is a political, sociocultural, and historical issue. This paper will reveal that the problems that migrant workers face, and the adaptations they experience, are not necessarily the same on the border as in the interior. It is the dynamics between migrant mobility patterns, their adaptive strategies, and the local historical development of sociocultural, economic, and political factors that shape multilayered space not only across the border but also within the same state-defined space.

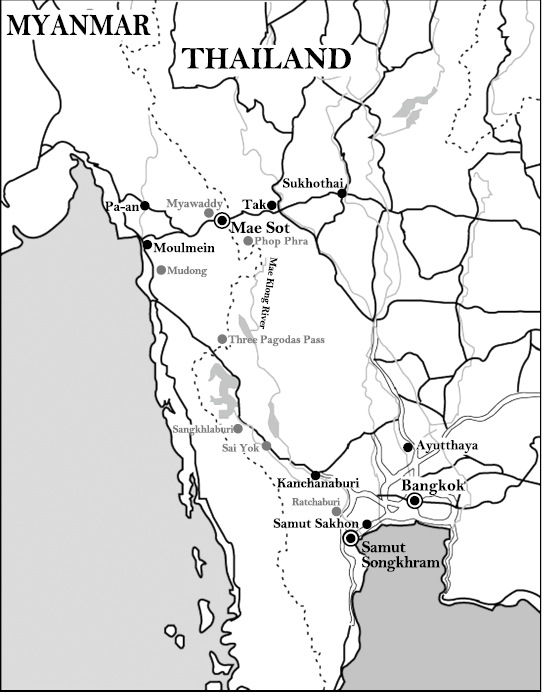

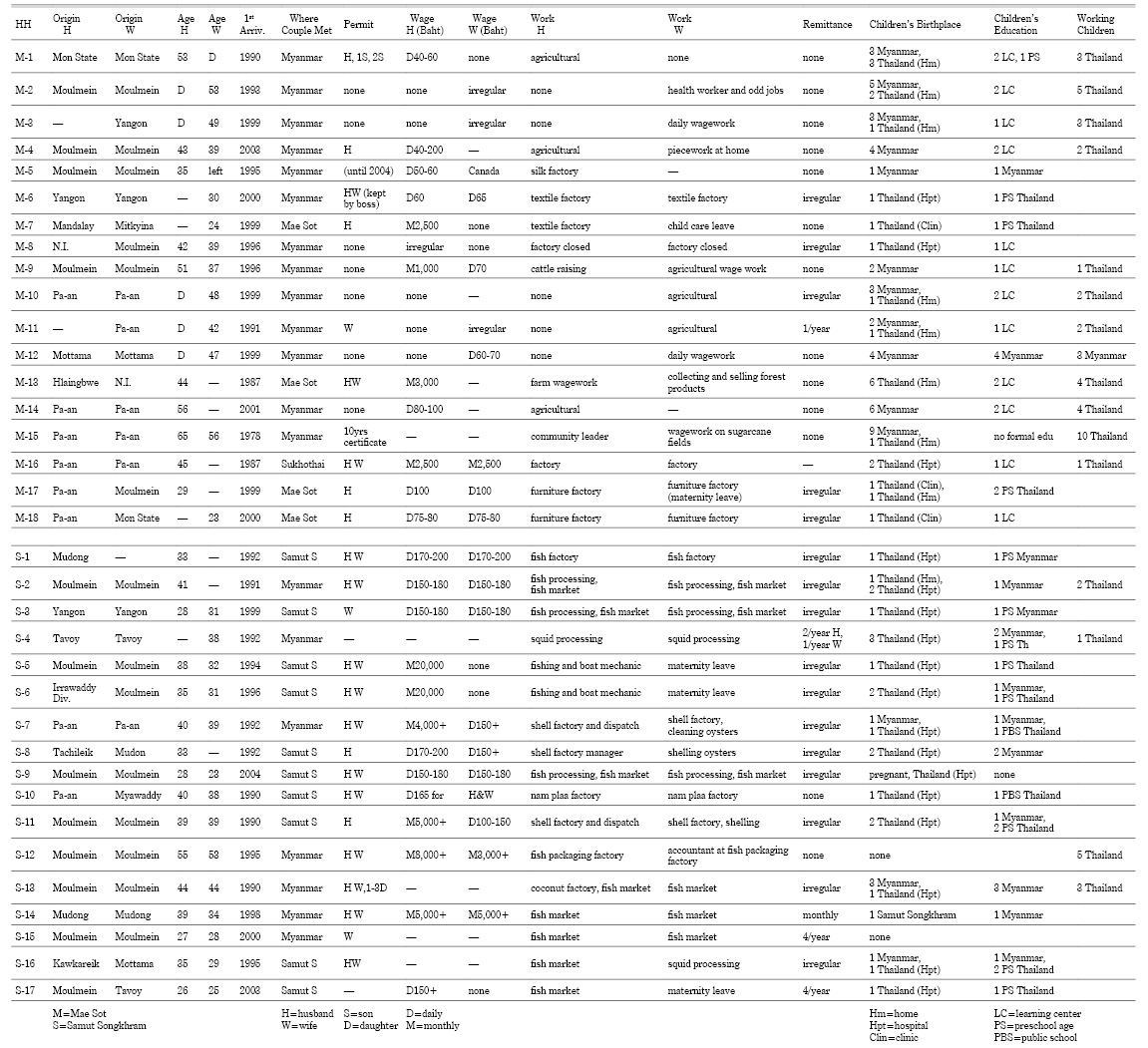

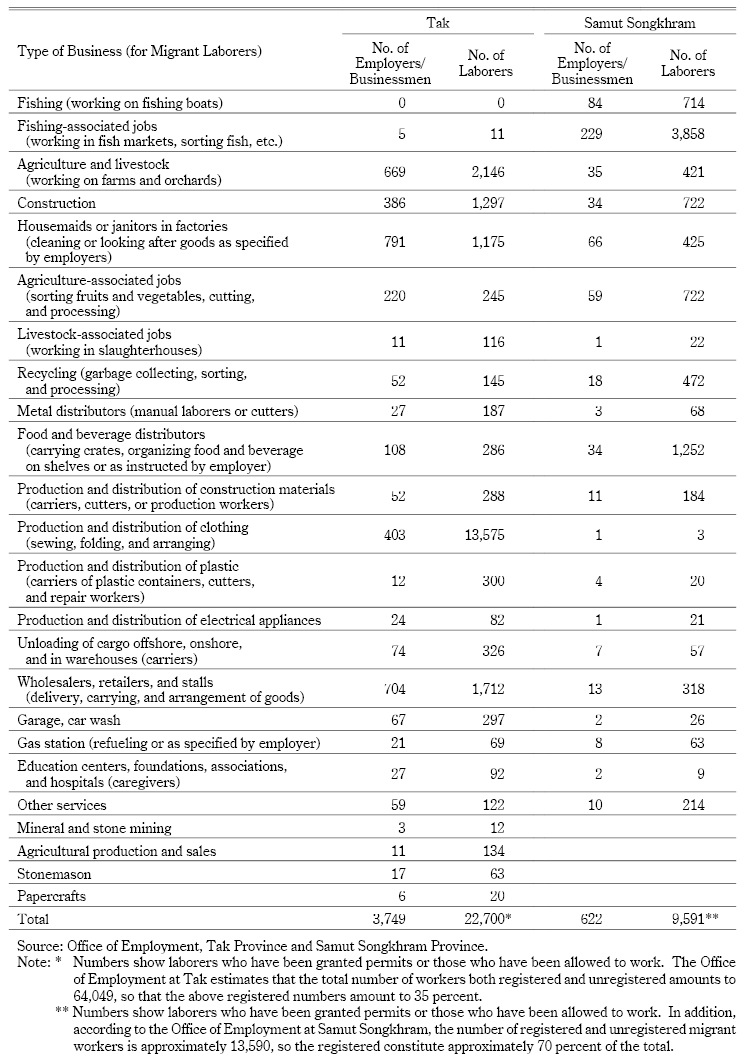

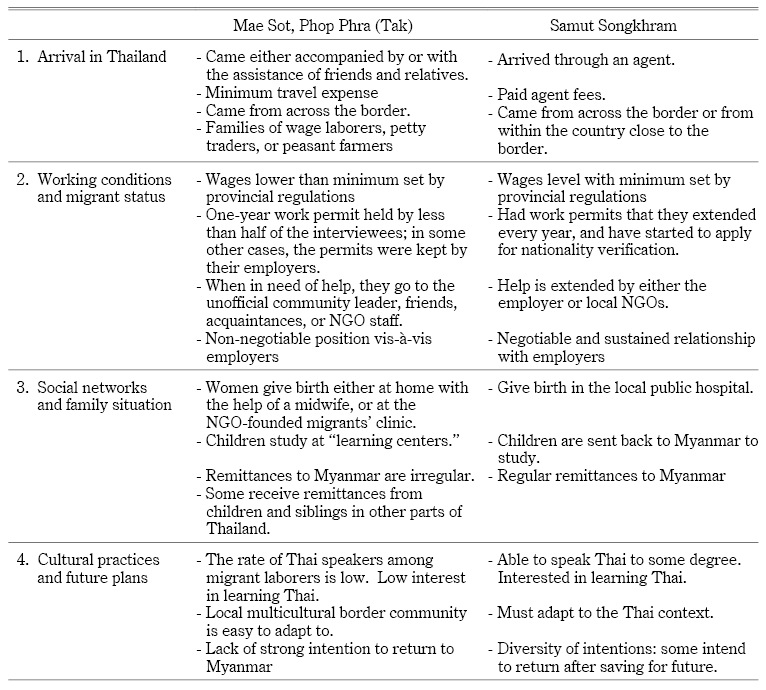

This paper is based primarily on fieldwork conducted in two locations: Mae Sot and Phop Phra in Tak Province, and the provincial headquarters of Samut Songkhram (Fig. 1). A total of 18 interviews were conducted in Tak: four in rural villages on the road between Mae Sot and Phop Phra, and the rest in three different neighborhoods within the town of Mae Sot. In Samut Songkhram, 17 interviews were conducted in several neighborhoods, all in the central district of the provincial capital (Table 1).3)

After a brief overview of state regulations, especially those in Thailand, and an introduction to the two study locales—one on the border and the other in the interior—the main part of this paper will be based on interviews conducted in the two locales regarding the mode of arrival of migrants to Thailand, work conditions, migrant status, social networks and family formation, and cultural adaptation.

II Background in Myanmar and Decision to Migrate to Thailand:Evolving Policies in Thailand

Laws governing the movement of people across borders were instituted in Thailand in 1950. Continuous changes and additions have been made since then with regard to laws and policies that control people’s movements.4) The Immigration Act 1979, amended from 1950, is still primarily in effect (subsequent revisions pertained to details such as the immigration fee). The Alien Occupation Act, which aimed to control alien workers and reserve job opportunities for Thai citizens, was launched during the revolutionary council in 1972.5) In 1973, the law restricted aliens and foreign workers to 39 types of jobs. Up to 1978, the major concern in Thailand was national security and stability.

The Thai government took up a policy of “constructive engagement” with Myanmar that began during General Chatichai Choonhavan’s administration (1988–91). Thai workers who were involved in the industrial and agricultural sectors began shifting to higher-paying work in the city, creating a demand for cheap labor. As the cost of labor increased during Thailand’s boom decade (1986–96), particularly in 1991 and later when real wages grew 8 percent a year, an increasing number of Myanmar workers migrated to Thailand to take up low-wage jobs. Jobs in fishery and seafood processing, plantations and agriculture, domestic work, and factories were often shunned by local Thais, and consequently the Thai economy became increasingly reliant on cheap migrant labor.

In 1992, Thailand took its first steps toward the adoption of an immigration policy for unskilled foreign workers by issuing short-term work permits in nine prefectures bordering Myanmar. Immigration law declared all migrant labor illegal, but workers were given permission to work by registering annually. Many anomalies cropped up as a consequence of this. First, in this system, workers were registered by a single employer and were not permitted to change employers unless they were re-registered by paying another full fee. Second, registration took place only twice a year, which rendered illegal those workers who entered the workforce in the interim period between the two registrations. Third, employers generally paid for the work permits of migrant laborers and deducted the amount from their wages in monthly installments. However, most small businesses and farms could not afford to pay the fees, and thus a large number of workers remained unregistered. Under such circumstances, both employee and employer were potentially vulnerable to harassment and extortion by the authorities. Fourth, those employers who did pay for the permits often held on to the original copy to maintain control of the workers for fear of losing them before the fee was repaid. This meant that workers were often unable to access health care and were subject to deportation because photocopies of documents were not recognized by the authorities. Fifth, not all incoming workers were aware of the registration procedure. Hence, migrant workers were faced with the constant threat of deportation with or without work permits, extortion by police and officials, heavy debts to the agents who negotiated their jobs leading to bonded labor, restriction of freedom of movement, and lack of health care. Their inability to speak Thai as well as their lack of information and awareness of labor and human rights added to their plight.

Subsequently, the laws aimed at controlling alien workers were revised with a gradual emphasis on human rights. This involved the opening up of previously restricted work areas, and the granting of employee rights and options to migrant workers.6) In 1996, the Thai government launched a regulation under the Ministry of Labor and Social Welfare that allowed foreign labor to enter the country legally, and to work under provincial restrictions and requirements. A significant number of migrant workers from Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar were registered with the Department of Employment. They could now work in 39 (later 43) provinces in 7 (later 11) industries. This is what Pitch (2007) refers to as the extension of the border beyond the physical border. In 1998 the Labor Protection Law was enacted, and immigrant workers came under the control of labor welfare and the labor court so they could directly sue on issues related to labor protection.

In 2001 a new labor registration was instituted under Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, when 560,000 laborers were registered in two months. Of this number, 40,000 were in Mae Sot. The annual cost of registration per worker was 4,500 baht, and it conferred on each worker the right to the 30 baht medical system. However, from the perspective of the workers, the economic and social costs of registration surpassed its merits.

In 2003, an MOU was signed to allow workers from Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar to register in Thailand, yet it took a long time to negotiate the details between Myanmar and Thailand. The Myanmar government recognized the importance of foreign exchange remittances. It had implemented overseas employment since 1999, and official employment agencies had sprung up, sending workers to other countries in Southeast Asia as well as to the Middle East. The Myanmar government attempted to control remittance flows by sanctioning remittances through government banks and taking a 10 percent service fee on the transactions. Meanwhile, the black market for international transfers flourished. In 2005, Myanmar also strengthened its efforts to institutionalize migrant workers in other countries (Malaysia, Singapore, the Middle East, Korea, and Japan), and immigration offices were set up at three major points along the Thai-Myanmar border: Myawaddy (opposite Mae Sot), Tachileik (opposite Mae Sai), and Kaukthaung (opposite Ranong). In the same year, the Thai government executed a royal decree7) allowing illegal aliens to work without a restriction on their numbers.

In 2008, the Alien Occupation Act8) was revised to take into consideration and recognize that alien workers were an important factor in the economic progress of Thailand, explicitly stating that alien workers helped to drive the Thai economy. Moreover, the Thai and Myanmar governments agreed to carry out “nationality verification,” a process through which those with verified nationality could receive temporary passports.9)

In 2009, Thailand reported that there were a total of 1.3 million registered workers from Myanmar, Cambodia, and Laos who resided illegally in the country and needed further verification of nationality to become legal migrants by February 2010. Migrant workers who failed to complete the registration process within the specified time period would be deported from the kingdom. However, one month before the deadline, only a small number of migrant workers had completed the identification process. Results from the verification of the nationality of workers from Myanmar as on 13 February 2010 showed a total of 26,902 migrants who went through the process at the three centers: 7,899 in Tachileik, 10,461 in Myawaddy, and 8,542 in Kaukthaung. There was an atmosphere of fear in the migrant community generated by a lack of information and an unclear understanding of the intent of the procedure, compounded by the workers’ inability to pay the agents. Consequently, the ministry extended the time for nationality verification until the end of 2012.10)

Mae Sot

The five districts along the border in Tak Province (Mae Sot, Phop Phra, Tha Song Yang, Mae Ramat, and Umphang) cover about 300 kilometers of border with forested hills and rivers. Historically, the area was a strategic point in the war and trade route from Mon country in Burma to Siam. Tak (Raheng) was the outpost of the Sukhothai principality. Prior to the imposition of the modern border, the area was a vibrant economic frontier since Britain started to explore the wealth of the region, especially the teak forests, as well as trade routes connecting its colonies to larger markets in China. When Thai King Rama III opened commercial dialogue with British Burma and conducted a survey of the area, the governor of Raheng pointed out 11 caravan routes cutting through the hills beside the Moei River and terminating at Moulmein. New forms of communication were implemented or proposed along this route, such as a postal service and a telegraph line.

Mae Sot was unclaimed prior to the demarcation of the border. Officers from Siam and Burma sometimes passed by to demand tribute from local Karen. This became the first area where the modern border agreement between British Burma and Siam was established in 1868. What had been forest settlements inhabited by Karen were promoted to a modern administrative town in 1898, bringing a gradual influx of the northern Thai population. Logging and border trade became key activities, and the market, which was frequented by Yunnanese Chinese Haw caravans, used British Indian currency. The city municipality of Mae Sot was founded in 1937. It is because of these historical and ethnic connections that to this day there are formal and informal networks of Karen, especially networks based on religious activities such as through the church or the Buddhist temple, and some based on political factions as well.

The town began to prosper in the 1970s, as it became the center of the black market border trade by the Karen National Union. Until the 1980s, the union controlled all routes and trade connecting Mae Sot to Yangon. On the Thai side, counterinsurgency brought about the development of infrastructure, and the road from Bangkok to Tak was completed in 1970. Whereas economic activities in Mae Sot had previously depended more on the Burmese town of Myawaddy, the political situation in Burma caused the center of urban development to shift to the Thai side.

In 1988, the movement for democracy in Burma sent students to the border. After Thai Prime Minister Chatichai’s declaration of “constructive engagement” the same year, factories began to spring up in Mae Sot and an increasing number of Burmese workers migrated across to take up low-wage jobs. In 1993 three provinces, including Tak, were designated as special investment promotion zones. Factory construction along the border was encouraged, with tax and duty privileges offered.

After the 1995 fall of Manerplaw, the headquarters of the Karen National Union on the Myanmar side, the Thai government enhanced economic activities along the border. The Burmese regime controlled Myawaddy, under the influence of the Democratic Karen Buddhist Army, the Karen faction that was aligned with the regime.11) This was the turning point in Mae Sot’s character and industrialization. In 1995, industrial investors arrived to employ the large pool of illegal migrant workers. The Thai-Myanmar Friendship Bridge was completed in 1997, and Burmese citizens gained the right to cross the bridge to Mae Sot without passports for a one-day stay.12) It was also in the late 1990s that former student activists from Myanmar began to get involved in migrant labor issues. A migrant workers’ rights group called the Yaung Chi Oo Workers Association was formed in 1999.

In the 1990s Mae Sot was included in the Thailand Board of Investment’s zone 3, which includes zones in the peripheries with tax privileges. It is also strategically located on the East-West Economic Corridor of the Greater Mekong Subregion scheme. The export quota system and joint venture investment instituted by the government, and the presence of cheap labor in Mae Sot, lured investors from Hong Kong and Taiwan via the Chinese business networks. In 2002 a cabinet resolution under the Thaksin administration declared Mae Sot a Special Border Economic Zone, encouraging investment, industry, and trade and calling for an expansion of infrastructure, tax and custom privileges, and relaxing of labor restrictions. Together with the border trade and the influx of cheap labor, further investment was lured to the area. However, the resolution did not involve structural change. Then, in 2005, a bill was passed in which Mae Sot was designed to be a combination of industrial estates and governmental agencies, where the private sector was the investor while the government supported the fundamental infrastructure. In 2011 the Thai cabinet approved a budget for hiring a team of expert planners to design the zone, and a government subcommittee focusing on legal preparations finalized a draft royal decree to create a special entity to run the zone. The zone would cover three districts along the border: Mae Sot, the main area for border trade, investment, industry, and tourism; and Phop Phra and Mae Ramat, with their focus on agriculture and agro-industry.

On the outskirts of Phop Phra and Mae Ramat Districts are plantations for export crops. Employers are mostly local, and here the pattern of seasonal plantation discourages the labor registration process. In the border area on the route from Mae Sot to Phop Phra, several migrant communities have been established, the majority being agricultural workers. In larger communities there is a temple with resident monks from Myanmar, a small health center, a small cinema or a common area to watch TV, and a grocery store that keeps regular hours. In Mae Sot, there are also different ethnic groups of workers from Myanmar spread out in communities in different subdistricts. The residential arrangement varies from huts built on rented land to rented rooms.

Samut Songkhram

Riverine cities such as Muang Mae Klong (Samut Songkhram) along the Chao Phraya have constituted important nodes since pre-Ayutthaya kingdoms. A large population, especially Mon, migrated to the area through the Three Pagodas Pass during the war between Ayutthaya and Burma, forming new communities along the river. In the lower Mae Klong, including Samut Songkhram, the communities experienced rapid growth from the reign of Rama I to Rama IV. Fruit orchards were planted, and the Mon population constructed temples as community centers. During the same time, the Chinese population started to converge around the Mae Klong River area. In Samut Songkhram canals were dug to create channels for improved movement of goods and trade, further drawing the Chinese population. In the late nineteenth century the Chinese population began to expand, leading to changes in the socioeconomic conditions of the lower Mae Klong and the development of the industrial and agricultural sectors in the area.

By far the largest population of Myanmar workers in Samut Songkhram is engaged in the fishing industry. In 1947 the Thai government stepped in to develop an operational structure for the fishing industry, introducing several programs to develop the infrastructure so that the industry, which began as family businesses, became more commercialized after the end of World War II and expanded rapidly between 1960 and 1972. Large investments began to pour in. Bigger ships with larger cold storage facilities were employed, enabling travel over longer distances. The industry expanded, and export to neighboring countries soon began. Fish was sold in various forms, which helped the industry grow until 1973, when it began experiencing limitations through trade negotiations with other countries.

In addition to growing adversity from the foreign market, the industry was also facing a labor crunch and therefore needed to introduce workers from the northeast of Thailand. This population soon took control of the profession. In the 1990s, however, Thai laborers from this area began to disappear. There were too many risks to contend with, such as being taken prisoner while fishing in international waters, or storms. This led to the hiring of foreign workers. Initially the fishing business in Samut Songkhram relied on the fish market in the neighboring province (Mahachai, Samut Sakhon), but when this market became overcrowded Samut Songkhram opened its own fish market in 1989. As the market expanded in Samut Songkhram, so did the demand for labor.

In the capital city center of Samut Songkhram, there is a large community of migrant workers behind the fish market. Other communities are spread out in the city and beyond. The workers live mostly in rented row houses, some of which have a common room for recreational activities where workers from the neighborhood can converge. There are shops among the rented rooms that carry products brought from Myanmar. There is a temple called “Wat Mon” by Thais, as well as other Thai temples where workers from Myanmar, especially Mon—who are numerous in the region—attend activities such as religious ceremonies, funerals, or Thai language study.

In both Mae Sot and Samut Songkhram, there is a sense of community for migrant workers that extends beyond the kinship network. These communities are a source of support in times of emergency, and a locus for cultural activities where the workers share their customs. There are usually unofficial community leaders who are recognized by the authorities and are trusted by the residents to protect the communities. These leaders also help organize cultural and recreational activities, which sometimes involve transborder cooperation. Occasionally workers seek help from nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) that pay regular visits to the community and provide various services, such as distributing medication and contraceptives, and disseminating information and knowledge about workers’ rights.

III Arrival in Thailand

Among the migrant workers interviewed in Mae Sot/Phop Phra (Tak), all but one person had come either accompanied by or seeking the assistance of friends and relatives who were already in Thailand. They had either “crossed the river by ferry and walked through the forests” or “crossed the bridge,” some fleeing from dire circumstances. Those who had walked through the forests arrived in rural villages and started agricultural daily wage labor. Migrants started as illegal immigrants and lived with the insecurity of being arrested by the police and being deported. As such, they were prepared to take any job available.

Migrants interviewed in this area were from families of wageworkers, petty traders, or peasant farmers. In two cases, the death of a husband had instigated the migration. In cases where a family moved, it was usually the husband or an older sibling who first entered and then later, once he had settled, called his wife or younger siblings to join him.13)

U (male, 43 years old) was the sixth of seven siblings, whose father died when he was three. Since his childhood he had peddled goods in Moulmein, as had his siblings. He married in Myanmar and had children. At 38, he decided to cross over to Thailand. He came by himself by boat and walked through the forest. Later his wife and children crossed over as well, and they met in the Forty-Second Kilometer Village. His friend lived there, and they decided to join him. However, after two months looking for work in vain, they decided to move to another village near Phop Phra. Now U works as an agricultural worker and lives with his wife and two children, as well as his younger brother and his child, who later followed him. (Case M-4)

E (female, 42), who is from Pa-an, first arrived in 1991. She entered by boat and walked through forests with friends, two men and three other women. In those days, border control was more lax than it is today. They lived in a village near Phop Phra and worked for daily wages in the fields. Her husband-to-be arrived later in Thailand. They had known each other in Myanmar and decided to marry in Thailand. They started a family and had three children in Thailand, but her husband died five years ago from a fever.14) (Case M-11)

By contrast, among the migrants in Samut Songkhram, at least 8 of the 17 interviewees explicitly mentioned that they had arrived with the help of an agent. In cases where the migrant moved directly from the border point to Samut Songkhram or to Bangkok, it was invariably through an agent. The agent’s fee ranged from 2,500 baht for earlier arrivals to 5,000 baht 10 years ago; it has since soared to as high as 15,000 baht. In most cases, including those who used agents, the new arrivals had siblings or close relatives already working in the area. Some had initially worked in other areas closer to the border, such as Kanchanaburi or Rajburi, but eventually found their way to their current location where wages were higher and there were more job opportunities, seeking assistance from a sibling or close friend. In addition, in comparison with the migrants in Mae Sot, most migrants in Samut Songkhram appeared to come from a more secure background as land-owning farmers.

M (female, 39) and her husband, K (40), were from farming households in Pa-an and married before they crossed the border. Using an agent, who charged 2,500 baht per person, they arrived in Bangkok in 1992. M began work as a housemaid, and K worked in construction. They had to live separately. In those days phones were not easily available, and they saw each other on weekends. After two years in Bangkok, M became pregnant. Together, the couple returned to Pa-an, because they were afraid to go to a hospital in Thailand as they did not have any permits. Back in Myanmar, they farmed K’s land. After two years they decided to relocate to Thailand again, leaving the child in M’s mother’s care. This time they entered Thailand through the Three Pagodas Pass to Kanchanaburi, and following the advice and introduction of friends, they arrived at Samut Songkhram. There they found work in marine processing factories. (Case S-7)

S (male, 39) and his wife, Y (34), are from Mudong, near Moulmein. They married in Myanmar and had one daughter there who was staying with Y’s mother, studying in high school. S came first, in 1998, through an agent with 20 others via Sangkhlaburi. In those days there were not many agents, but entering Thailand was easier. After one year, he called Y to join him. Now it is far more difficult to enter, and agents’ fees are expensive. (Case S-14)

There is thus a significant difference in the way that migrants arrive at these two locales. In Mae Sot, they arrive without the assistance of agents. Upon arrival, they have little choice but to seek employment in the border areas where they can get by using Burmese or Karen languages. In Samut Songkhram, migrants are ambitious enough to seek jobs with higher wages, and they have the means and financial resources to use agents. At the very start, therefore, a difference exists between those who have the means and channels to go to the interiors, such as Samut Songkhram, through an agent; and those who seek any improvement to their impoverished condition, arriving through their scant means at the border. In either case, however, they need to conceal themselves as illegal immigrants without work permits. Migrants walk through the forests at great risk with or without agents. Some catch malaria and die on the way, while others are caught and deported unless someone bails them out.

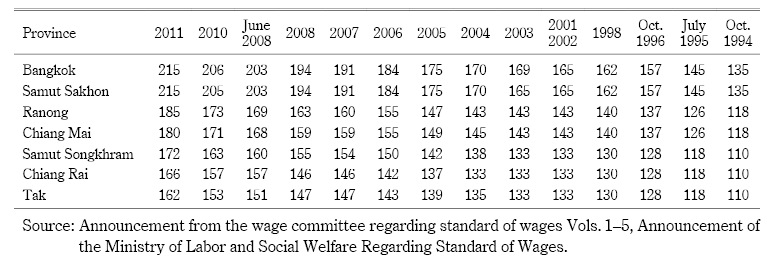

IV Working Conditions and Migrant Status

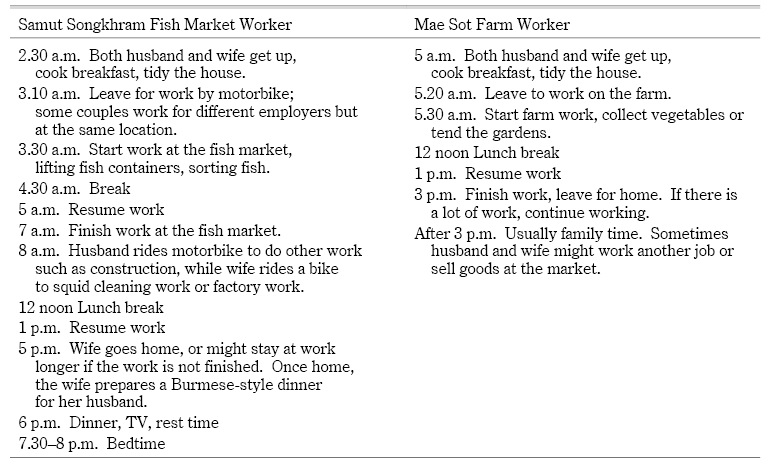

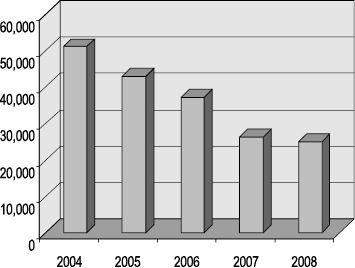

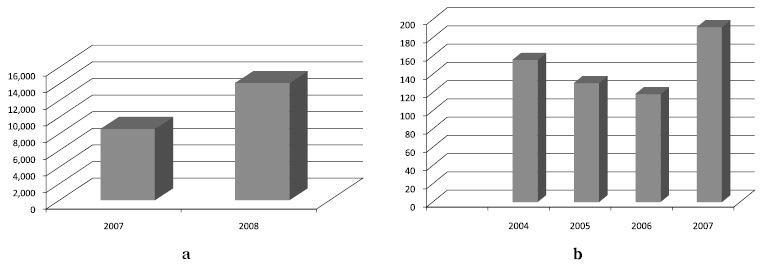

Wages and working conditions vary greatly between regions and tend to be higher in the interior especially around Bangkok (Table 2). However, even though some border locations, such as Ranong, have a higher wage structure than Samut Songkhram, the latter offers workers the opportunity to hold two or more jobs simultaneously, such as marine processing or market aid in the morning and construction work during the day, so the actual wages can be correspondingly much higher (Table 3). In Mae Sot, as explained above, wages paid to migrant workers are kept far beneath the provincial wage level. Among the 18 interviewees in Mae Sot/Phop Phra, 5 had jobs in factories and the others worked on farms or at irregular jobs. The wages started at 40 baht per day, an incredibly low figure.15) The number of workers with one-year work permits was less than half of the total number of interviewees, and even then, in many cases the permits were retained by their employers, adding to their sense of insecurity. This is corroborated by the Tak employment office figures showing that only 35 percent of migrant workers were registered (Fig. 2); in contrast, in Samut Songkhram 70 percent of migrant workers were registered. Interviewed workers in Mae Sot did not describe the relationship with their employers as one they could rely upon but said that, instead, they sought assistance mainly from NGOs operating in the area. As a rule, when they needed assistance they turned to the unofficial community leader, friends, acquaintances, or NGO staff who extended information on workers’ rights and helped them claim these rights from their employers.

Table 3 Comparison of Daily Work Schedule of Samut Songkhram Fish Market Worker and Mae Sot Farm Worker

Fig. 2a Number of Registered Laborers in Five Border Districts (Mae Sot, Phop Phra, Mae Ramat, Tha Songyang, and Um Phang), Tak Province

Source: Office of Employment, Tak Province.

Fig. 2b Number of Registered Laborers in Samut Songkhram Province

Source: Office of Employment, Samut Songkhram Province.

M (female, 24) met her husband in a carpet factory in Mae Sot. She no longer works, since her son is only one year and two months old. She delivered her son in Mae Tao Clinic.16) Her husband is now the sole earner in their family, earning between 2,000 and 2,500 baht per month. Paying the rent and feeding the three of them leaves barely any money for savings. In the past, she and her husband worked in a garment factory in Bangkok for a year. They were arrested by the police, detained for 48 days in Bangkok, and then sent to Tha Sib (a border checkpoint that serves as a detention center for deported workers). They were forced to spend several days at Tha Sib, until finally they found a friend to bail them out. Then they had to save money to repay the friend. The incident shook them up enough to prevent them from ever venturing into another province again. (Case M-7)

In 2000 J (female, 30) accompanied her husband to Mae Sot, where their son was born. She works in a textile factory for 65 baht per day, but her employer has not paid her wages for the past two months. Wage payment is always delayed, so the family cannot meet their basic living needs. J had a permit in the past, but since her current employer has taken it she cannot get it extended. Her husband is in exactly the same situation. He moved from the sewing section of the factory to the factory canteen, so that he could alternate with her in caring for the baby. He earns 60 baht a day. J works from 8 in the morning to 10 in the evening, with two one-hour rests during which she takes over the care of her baby from her husband. Her older sister works in a textile factory in Bangkok, where wages and working conditions are better, but now that J and her husband have the baby they are afraid to move to Bangkok for fear of being detained by the police and deported to Myanmar. (Case M-6)

Migrant workers continue to be vulnerable, for the police have free reign to arrest any worker on the street, lock them up, and wait for the employer to bail them out. As such, it is incumbent on employers to maintain a good relationship with the police. In the border region, complicit agreements between the authorities and businesses keep wages at a low level (Arnold 2007). There is a tacit understanding between the nexus of the chamber of commerce, the labor office, and factory employers—and stories abound of employers who delay or refuse wage payment or take possession of workers’ permits. Under circumstances such as these, it is difficult for a worker to raise their voice against the establishment, as is obvious in the case of M below.

M (male, 35) and his wife came to Mae Sot in 1995. His wife applied for third-country relocation and moved on to Canada in 1999, leaving him alone. He worked in a textile factory from 8 in the morning to 10 in the evening with two one-hour rests, earning a daily wage of 50 to 60 baht. He had one-year work permits until 2004. After that he had problems with his employer, who would not give him a work permit. He could not seek any other work because his employer put his name on a blacklist of troublesome workers. Currently, he assists with work at the migrant workers’ association. When he acquired his work permit several years ago, 400 baht was deducted from his salary to pay for it. Now, ironically, he loses 200 baht per month to the police. During work hours, he says, when there is an official inspection in the factory, those without work permits are instructed to hide in the forest; they are recalled when the inspection is over. Even so, life in Thailand, he stresses, is easier than in Myanmar. Now, without his permit, he also takes on various odd jobs outside the factory. (Case M-5)

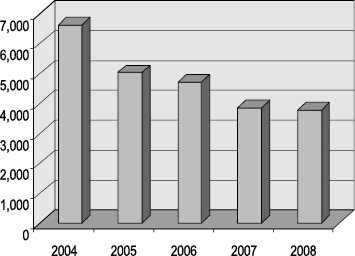

Even under such harsh conditions, many workers interviewed professed that life in Thailand was much better than in Myanmar. The reasons why they did not move on to areas such as Bangkok and farther south, where they knew that wages and conditions were much better, included the following: (1) some of them had no relatives or acquaintances and could not afford to hire agents; (2) they were afraid of being detained and sent back since they would have to bail themselves out, something many could not afford; and (3) their children could receive an education on the border (more on this below). With respect to the second reason, at least four of the interviewees in Mae Sot admitted that they had been detained and taken to Myawaddy and had to be bailed out (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Number of Foreign Laborers (Illegal Migrants Working without Permits) Arrested in Mae Sot District, Tak Province (a), and Muang District, Samut Songkhram Province (b)

Source: (a) Mae Sot District Council, Tak Province; (b) Muang District Council, Samut Songkhram Province.

The prevalent practice among those interviewed in Mae Sot was that the husband would work with a permit, while the wife would stay at home with young school-age children without obtaining a work permit. This was different from the Samut Songkhram cases, where husband and wife worked together, both obtaining permits, and where in many cases young children were sent back to Myanmar for the grandparents to look after. The motivation to earn and save is evident in the case of migrants in Samut Songkhram, whereas in the border a majority of migrants lead a hand-to-mouth existence yet choose to stay because even under such harsh conditions, they believe that life is better there than in Myanmar.

While working conditions in Samut Songkhram are far from easy, wages are comparable with the local standard, and all of the interviewed workers had work permits that they extended every year (Fig. 2). They tended to remain loyal to their jobs, although most workers who were employed in the market did multiple jobs each day. Many couples did a double routine of working in the fish market early in the morning (starting around 3 a.m. and continuing to 7 a.m.) and then doing other jobs (Table 3). Men did construction work, while women took buckets of squid home to process (Table 4). Each person earned around 170 baht per day, which added up to more than 300 baht for a couple. Room rent was between 1,200 and 1,800 baht per month.

Table 4 Business Owners Hiring Foreign Laborers from Laos, Myanmar, and Cambodia in Samut Songkhram and Tak in 2010

J (male, 28) arrived in Samut Songkhram in 2004 and works in the fish market. Initially he earned the average newcomer wage of 80 baht per day, but now he brings home more than 100 baht. After working in the fish market in the morning, he sells fish or does other work the rest of the day. He is learning Thai through an extracurricular course provided at a Thai school. Both husband and wife hold work permits with the assistance of their respective employers in the market. In the beginning, when he did not have a permit, J was caught by the police on numerous occasions because the police recognized newcomers. Each time, he had to pay his way out with 500 or 600 baht. His younger brother was once deported, and it cost 12,000 baht to bail him out. J is now arranging to obtain a passport, which will allow him to stay in Thailand longer and to move freely. His current work permit restricts him to the prefecture he works in, and every visit to Myanmar involves payment for permission to travel, despite which he may find himself in danger of being caught on either leg of the journey. A passport will afford him the liberty to travel home as often as he wishes. His parents have never met his wife, with whom he met and married in Thailand. The couple’s parents had a meeting in Myanmar, but he has not been able to return home so far. (Case S-9)

K (female, 32) met her husband (38) in Samut Songkhram. He has been in Thailand, working on fishing boats, for 10 years. He is the captain of a fishing boat, and he also works as its mechanic. K worked at peeling squid, but now that she has a three-year-old daughter her husband has asked her to stay home and look after the child. He returns home only once every three or four months, and rests for a week. He earns 20,000 baht per month. Both have work permits that they extend every year. Their monthly house rent is 1,400 baht plus gas (around 100 baht). Not only are they better off than most other migrant workers, but their family’s relationship with K’s husband’s employer is exceptionally good. Her husband’s employer drives K and her daughter to visit ports such as Prachuap or Chaam, where her husband’s ship occasionally docks. Her husband could not speak Thai in the beginning, but he now speaks it fluently, which adds to the measure of his employer’s trust. (Case S-5)

K’s husband’s case (S-5) is exceptional as he is the captain and mechanic of a fishing boat, which is considered skilled work. However, even in the case of unskilled workers, employer-employee relationships, as depicted by interviewees in Samut Songkhram, tend to be positive. Many interviewees refer to the assistance they receive from their employers in a variety of situations such as marriage, sending their children to school, recommending hospitals, helping pay hospital fees, and recommending medications. The employers also assist in extending their work permits and sometimes agree to pay the registration fees for them in advance. In some cases where workers get arrested by the police, their employers help in negotiating their release. NGO officers in Samut Songkhram disclosed that they advised migrants mainly on health and hygiene issues, rather than issues of workers’ rights or quarrels with employers.

Cases of deportation are heard of frequently among newcomers without work permits in Samut Songkhram, who are vulnerable to arrest and deportation. However, Samut Songkhram workers are better able to pay the cost of the bailout. For newcomers the first year, more than any other time, is the most difficult. They have no work permits, lack information, and must adjust to the cost of living, since there are many wage deductions by the employer in cases where employees take loans to pay an agent. Once the workers find jobs, however, they begin to learn, from both Thai and Burmese acquaintances, the minutiae of Thai regulations and their rights in Thailand, such as workers’ rights regarding wages and the changing policies regarding migrants.17)

As stated above, migrant workers can now apply for nationality verification toward obtaining temporary passports, which will grant them fully legal status. Workers in Samut Songkhram have started to apply for nationality verification and passports through this system. For workers, the most significant advantage of obtaining a passport is that it will allow them freedom of movement back and forth between Myanmar and Thailand, as well as within Thailand. Without a passport, the risk and expense for each trip is very high, forcing workers to limit visits home to once every few years at most. If they have to travel through another province in order to reach the border, the risk multiplies. Leaving the country is relatively easy, but reentering is very difficult. The border point is increasingly difficult to pass, requiring high sums to be paid to agents. Once workers prove their nationality and hold passports, they can travel freely. In addition, if workers have a passport and work permit, their family members or companions have the right to apply for a visiting visa.

In stark contrast, none of the workers interviewed on the border in Mae Sot/Phop Phra were undergoing the nationality verification process. Interviews in Mae Sot revealed that migrants were not well informed about it. Moreover, there was less need felt for it as those on the border did not need to travel through other provinces to reach their homes in Myanmar. According to information from the Employment Office in Samut Songkhram, as of August 2011 there were a total of 3,613 migrants (37 percent of all registered workers) whose nationality verification had already been processed. In Tak Province there were a total of 3,853 (16 percent of all registered workers: note that the rate of registered workers with permits was much lower in relation to the total number of workers), which reflects the general trend of drastically lower rates of registration.

It is apparent from the interviews that the difference in the condition of workers between the border areas and the inner regions is not only in wages but, more importantly, in migrant status, stability and relationship with employers, access to information, and motivation in the work situation. Working conditions and relationships with employers thus differ markedly between the two locations. In Mae Sot, the structure of relationships among the authorities, businesses, and workers is exploitative. The benefits of registration are low in such a setting.

V Social Networks and Family Matters

Choices regarding family formation, distribution, and mobility are affected by the conditions surrounding the workplace, as well as migrant status, and differ significantly between Mae Sot and the interior. Some of the migrants marry and start their families before migrating to Thailand, in which case the choice is whether and when to bring other family members. For those who marry in Thailand or migrate as couples, the choice is where to have children and where to bring them up. This affects their remittance patterns and their connection with their homeland.

Family Formation, Bringing up Children

Migrant workers began to flood into Samut Songkhram in the 1990s, mostly new arrivals who were young couples or unmarried youth who married and started families after their arrival. Of the 17 couples interviewed, 10 had met and married in Samut Songkhram, while 7 had been married before.18) This being the scenario, most of the couples began to have children after arriving in Samut Songkhram. In Mae Sot, on the other hand, 13 interviewees already had a family before coming to Thailand.

When a migrant is pregnant, especially in the case of young first-time mothers, she might choose to return home to seek the guidance and help of her mother and relatives. However, such a decision is fraught with uncertainty and fear regarding communication with Thai police and officials on the return journey. Some migrants give birth in Thailand. In the case of migrants without work permits in Mae Sot and Phop Phra, women give birth either at home with the help of a midwife from their community, or at the NGO-founded migrants’ clinic. In Samut Songkhram, where most women and men have work permits, the choice is always to give birth in the local public hospital, where a birth certificate can be obtained. This means that the child can later apply for Thai citizenship.19)

In Mae Sot and Phop Phra, even in cases where the young mother returns home to Myanmar to give birth, in most cases she returns with her children rather than leave them in Myanmar with their grandparents. In the 18 interviews at Mae Sot and Phop Phra, there were only three cases where children were left in Myanmar for their education. Migrants at the border, who lead a hand-to-mouth existence, cannot afford to send regular remittances to their parents to look after their children.

In four districts adjacent to the border in Tak, there are about 11,000 Burmese children annually enrolled in the 134 schools under the Thai educational system (from kindergarten to 12th grade). However, education for children of migrant illegal workers is available on the border in the form of “learning centers” (LCs). These are private schools for migrant children outside the Thai educational system. They provide education for migrants’ children close to their own community (Premjai 2011). Classes are taught in Burmese, Karen, or other ethnic languages. There are also Thai teachers who help students learn the Thai language. In 1999, 60 LCs formed an organization called the Burmese Migrant Workers Education Committee. These schools differ in size and in the age of students, but they all have 80 to 150 students, from kindergarten to fifth grade. Since these are unofficial teaching centers, they operate like NGOs and are funded and supported by international organizations. Tuition is free, and technical work support is also provided. Children who go to LCs rarely have the opportunity to go on to higher education, since LCs function outside the formal curriculum. A small number of higher education institutions, usually funded by NGOs, offer further education; all of them are in Mae Sot, including in the refugee camps.

M (female, 48) came to Mae Sot in 1999 with her husband and children. A year ago her husband passed away with to a fever. Her children go to an LC where teachers from Myanmar teach 50 migrant children. Her three older children were born in Myanmar before they moved to Mae Sot, and the youngest was born in Mae Sot. At the time of the youngest child’s delivery, M and her husband called a midwife to their home because they were afraid to go to the hospital. The eldest daughter (23) now works for a daily wage on a farm. Of the three sons, the eldest works in construction, has already married, and lives in Mae Sot. The two younger sons are still at school (LC), and M hopes that they will complete school even though they will not receive any diplomas. She sends remittances occasionally to her mother, who lives with her younger sister, her only sibling. The two older children contribute their wages to the household budget. M has no relatives in other provinces and has never thought of relocating. (Case M-10)

N (female, 39) had her first child after coming to Thailand. Her daughter has joined a school near the community. N says that she cannot afford to send her daughter to study in Myanmar. She can rarely send remittances to her mother back home as she has barely enough to make a living for herself. She visits home once a year with her daughter. She and her husband (42) have never been to another province; they confine themselves to their area and do not plan to look for work anywhere else because they have their daughter to look after. (Case M-8)

A marked contrast can be found in the manner in which migrants in Samut Songkhram educate their children. Most children are sent back to Myanmar, which is costly in terms of remittance. A few send them to the local Thai public school, seeking admission with the help of their employers.20) In 10 cases of those who gave birth to children in Samut Songkhram, the choice was to give birth in Thailand and then, when the child was around five years old, send the child back to Myanmar to study. In one case, the woman returned to Myanmar to have the baby, left the child in her mother’s care, and returned to work in Thailand. In cases where the child remains in Myanmar, it is usually the grandparents who look after the child with the help of other relatives nearby. Remittances are sent for the child’s school fees as well as living expenses. In one case, a child who had finished schooling in Myanmar joined her parents in Thailand. Her birth certificate from Thailand enabled her to obtain a Thai identification card.

T (male, 33) has two children (ages 9 and 5) who stay with his wife’s mother in Mudon (Myanmar). They were both born in Samut Songkhram and have birth certificates. When the older child was six, their mother took both of them home. The older child goes to school, and the younger is preparing for admission into school. The couple prefer to have their children educated in Myanmar, because this allows them to concentrate on their work in Thailand without the attendant distractions of child rearing. They talk to their children on the phone once or twice a month. (Case S-8)

V (male, 41) and his wife, M, have three daughters, aged 17, 15, and 8. All three were born in Thailand. The oldest was born at home when they worked in Tsai Yok (on the border), and the other two were born in the hospital. M returned to Myanmar after the birth of her first baby, for in the absence of telephones in those days it was hard for her to get advice on child rearing from her mother in Myanmar. When the child was 14 months old, mother and child returned to Thailand. The two older daughters attended school in Tsai Yok, the older one up to third grade, after which she was sent back to Myanmar. She was five years old when she began school and remained there until she was eight. The youngest child is currently attending school in Moulmein. She was sent to Myanmar when she turned five, with M’s sister who was visiting. V wanted to bring her back to Thailand, but M’s sister insisted on the child staying with her in Moulmein. V says he will bring her to Thailand once she is a little older. The family has since moved to Samut Songkhram, and the two older daughters work processing squid. (Case S-2)

M (female, 39) and K (male, 40) had their first baby in Pa-an after a stint in Bangkok (Case S-7, see arrival section), and they stayed on in Myanmar for two years working in the fields. They then decided to relocate to Thailand, so they left the baby with M’s mother and sister. They work in Samut Songkhram, and it was here that they had their second child. This time, since they had a work permit, they opted for delivery in Mae Klong Hospital. The child is now eight years old and goes to a local Thai public school. M wanted him to go to Myanmar to study, but the son did not want to go. K’s employer assisted them in placing him in the local public school. The school fees are approximately 100 baht per month, and textbooks cost several hundred baht per term. The couple hope that he will finish high school. Their daughter is now in seventh grade in Myanmar. She has never been to Thailand, and she currently lives with her aunt (M’s sister) and works in the fields. M and K send remittances regularly and call home every month. M hopes that their daughter will eventually join them and work in Thailand. M took her son to Myanmar for three months when he was nine months old, when her mother was seriously ill. The boy has not been to Myanmar since. (Case S-7)

Families make decisions as they gain knowledge and experience in ways of coping, and as their children grow up. Among the interviewees in Samut Songkhram, in only three cases had the children studied in a Thai public primary school. Gaining admission in Thai schools has thus far not been a common choice, for several reasons. First, it has not been easy for migrants to enter a Thai school. Strong support from an employer has made it possible for some. The documentation work has, however, become much easier, and more parents may make this choice in the future.21) Second, it is easier for parents to work from before dawn to late in the evening if they do not have young children living with them. Third, many parents confess that they prefer for their children to study in Burmese schools and receive an education in Myanmar. Once they finish school, in most cases children join their parents in Thailand.

Remittances and Ties across the Border

Due to the dire economic situation of most workers in Mae Sot and Phop Phra, sending remittances regularly to Myanmar is difficult or impossible. Of the 18 interviewees, 5 explicitly said that they had no money to send back (2 of them said they sent remittances until they had their own children). Only two replied that they sent remittances every year. In both cases, some of the children are grown and now working.

N (female, 39) came to Mae Sot in 1996 with her husband. They have a 10-year-old daughter who was born in Mae Sot and now goes to a nearby LC. Eight years ago, the textile factory in which K and her husband worked closed down. Since then, the husband has sought daily jobs. They have not considered moving elsewhere where the wages are better, because they want their daughter to receive an education in the current setting. K says that they do not have the money to send her to school in Myanmar. K sends remittances to her mother whenever she can, which is not often. She goes home to Myanmar once a year with her child. Crossing the bridge by car and traveling to Moulmein takes one day and costs 20,000 kyat. She has 10 older sisters and one older brother. One sister remains in Moulmein with her mother, working in the fields. Three are in Bangkok, and the rest are in Mae Sot. K lives with her husband and his mother, who helps to take care of the child. (Case M-8)

Remittances from Samut Songkhram are more regular and systematized, as workers in Samut Songkhram are financially better off. Samut Songkhram parents with children in Myanmar send remittances to cover the expenses of their upkeep. In 8 of the 17 families surveyed, the children stayed in Myanmar and remittances were sent mainly to cover their expenses. Remittances were sent for other purposes as well. In two cases, the couples were building their own house with their remittance. In four cases, the couples were young and without children, or they had children in Thailand but sent remittances to their parents.

N (female, 38) came to Thailand 20 years ago, and after a few years working elsewhere she came to Samut Songkhram, where she met her husband (40). They returned to Myanmar for their wedding. Their son attends a local Thai public school. When their parents are sick they go back to Myanmar, and when there are religious ceremonies and various other events they remit additional money besides their regular remittances twice a year. (Case S-10)

J (male, 28) and S (female, 23) are newly married. They both send remittances to their respective parents. They pay, on average, around 50 to 60 baht per 3,300 baht to remit money to Myanmar through an agent. (Case S-9)

S (male, 39) and his wife, Y (34), married in Myanmar and migrated to Thailand. Their daughter was born in Samut Songkhram and then sent back to Myanmar with Y’s mother, to whom the couple sends 3,300 baht per month out of their total average monthly salary of 10,000 baht. They want their daughter to visit Thailand from time to time, but primarily to study until university level in Myanmar. Their daughter is already in her second year of high school. S and Y came to Thailand initially by following the trail of S’s older brother. The brother has now returned to Myanmar and has built a house with his savings. S, too, is hoping to save enough to build a house and purchase some fields, and to live with his family back in Myanmar. He intends to stay in Thailand until he has saved enough to secure his future. His house is already under construction, and Y’s mother oversees it. (Case S-14)

The differences in remittance patterns between the border area and the interior are corroborated by Nwet Kay Khine, who compared the remittance practices and the support system between Bangkok fishery workers on the one hand and Mae Sot factory workers on the other (2007). Among Bangkok workers, the average wage was 191 to 195 baht per day, and they sent home monthly remittances ranging between 100,000 and 200,000 kyat. These were sent by way of what the author refers to as the “hundi” system. Remittances cover debts incurred back in Myanmar, or are sent to workers’ families who are in many cases taking care of their children. The remittance system, which has been in operation since the late 1990s, works in such a way that workers choose the agents with the best rates, and the agents rent their mobile phones to the workers so that they can inform the recipients in Myanmar that the money has been remitted.22)

It is more difficult for factory or farm workers in Mae Sot and Phop Phra to send remittances regularly; and when they do, it is through less systematized channels, such as asking a village acquaintance to carry the money home, or waiting for a family member to come and collect it. When a co-villager is requested to carry money home, a fee of 200 kyat per 10,000 kyat is paid. Others claim that they carry some money home every few years. In some cases, those in Mae Sot are at the receiving end of remittances sent from Bangkok. In one case, a couple in Mae Sot/Phop Phra received monthly remittances of around 1,200 to 3,000 baht from their daughters in Bangkok. They themselves sent remittances home to Myanmar irregularly.

Networks of Family Relations Extending on Both Sides of the Border

It has been demonstrated that from the outset, the choice between moving from their homeland in Myanmar to the Mae Sot/Phop Phra border region on the one hand, and moving directly to the interior on the other, involves a different set of preparations and mediations, and results in vastly disparate work conditions as well as choices for the family. The kind of adaptation required in each locale differs. However, the border can become a stepping stone in the march to the interior—if not taken by the original migrant, then by the next generation or other relatives.

Workers in Mae Sot/Phop Phra recognize that wages are higher in the interior. However, their physical mobility depends greatly on the condition of the family. Older parents may have children who work in the interior and may receive remittances, while they stay on the border, continuing daily wage labor, often without work permits. Their children become their new resource by moving to Bangkok. In two cases that we encountered, children sent remittances to parents on the border.

W (male, 44) got married in his early 20s when he returned from working in Lampang. He met his wife when he first came to Mae Sot. They have six children between the ages of 7 and 20; one died in childhood. All of his children were born in Thailand, delivered by a Karen midwife in their community. His son works in Mae Sot, and his daughters work in Bangkok as housemaids. They talk on the phone almost every day, and the daughters send remittances to their parents whenever possible. His two youngest children attend an LC. (Case M-13)

E (female, 42) came to the border area in 1991. She married in Thailand and has three children. Her husband passed away from a fever five years ago. The two older sons are working in Bangkok, receiving computer training as they work. She talks to them every Sunday on the phone. The youngest goes to an LC in Mae Sot. At the time of the birth of her first two sons, she returned to Pa-an in Myanmar so that her mother and siblings in Pa-an could help her cope with the birth and early childcare. One month after giving birth she returned to Thailand, leaving her older son in Pa-an until he came to Mae Sot at the age of eight. The second son studied up to second grade in Myanmar and then moved to a Thai temple for education. The youngest has never been to Myanmar and now studies in third grade at an LC. E also looks after her nephew (the son of her sister who works in Bangkok). E has seven siblings: three sisters are in Thailand, and the rest are in Pa-an tending to the fields. E sends annual remittances to her mother of around 50,000 to 60,000 kyat. She returns to visit her mother once every year or two, without passing the border checkpoint. (Case M-11)

We also encountered cases where migrants on the border looked after the children of siblings who worked farther in the interior, and who sent back remittances to the border for the upkeep of their children.

In Mae Sot, workers are not dependent on their parents or their family in Myanmar for raising their children, and they are not able to send remittances very often. Conversely, in Samut Songkhram, migrant workers draw upon the help of their relatives in Myanmar for support in bringing up their children. Remittances are sent regularly, and cultural and social ties are maintained. In a sense, for those in Samut Songkhram, ties with the homeland are based on mutual dependence of child care and remittance, whereas for migrants in Mae Sot they are based on sociocultural proximity and physical contiguity. In either case, networks of family relationships are formed on both sides of the border. For the former set of migrants, networks and ties of mutual dependence extend widely between various parts of Thailand and especially the homeland, and are actively maintained. For the latter on the border, mobile offspring or siblings may move to the interior and send remittances back to the border, while ties with the homeland tend to become secondary in spite of their physical proximity to it.

VI Cultural Practices and Future Plans

Even as workers maintain ties with their homeland and seek refuge in a community in which they can continue cultural and religious practices in their own style, it is crucial for them to acquire the ability to communicate and adapt to Thai culture and society to a certain extent in order to be able to negotiate with employers, police, or administrators and to improve their own conditions overall. Linguistic ability is one clear measure of the readiness to adapt, but not to assimilate, to the Thai context.

In Samut Songkhram, the workers interviewed were making the effort to learn Thai. First-generation migrants who have been in the country for more than five years, both male and female, are able to speak Thai to some degree. Here, life would be difficult without adapting to the Thai context, because the migrants are enveloped in a Thai world. Within their community they maintain their customs and language, but they adapt to the Thai setting outside the community, where they refrain from chewing betel or wearing their Burmese sarongs. There is also a school for children to learn Thai that is run by NGOs, as well as one for adults at the education center where lessons are given twice a week for 400 baht a month.

Workers in Samut Songkhram are eager to improve their skills at work, as well as their linguistic skills and relationship with their employers, because it means gaining their trust and obtaining better wages and improved work conditions. Employers and employees enjoy the benefits of mutually stable relationships. Yet, despite these relationships and efforts to adapt, 6 of the 17 respondents in Samut Songkhram clearly said that they wanted to return to Myanmar once they had saved enough money. The rest were ambiguous in this regard, especially those few who had children studying in Thai schools.

L (male, 39) makes approximately 5,000 baht a month working at a seafood factory. He also helps with the accounts and in dispatching products. He finished high school in Myanmar and initially worked in Mae Sot selling textiles in the market. He paid an agent and relocated to Samut Songkhram. His wife works in the same factory shucking oysters at 8 baht per kilo. Their rent is paid by their employer. L speaks Thai fluently, and he can also read and write. When he first came to Thailand he could not speak the language, but when he was caught by the police and detained for a few months, he studied it. He now has a work permit. His wife still does not have a permit, which means that she cannot move around Thailand freely—but if she gets in trouble, his employer will help. L is currently in the process of obtaining nationality verification. With this under his belt, he can travel freely to and from Myanmar, and he can bring his daughters back for holidays in Thailand. His daughters are currently staying with his parents and attending school in Moulmein. (Case S-11)

P (male, 40) and his wife have many siblings living together in the same row house. Their son and their nieces and nephews already have either Thai identification cards or birth certificates. Five of P’s siblings and three of his wife’s siblings are in the same province. Everyone speaks Thai. His son, however, speaks Thai better than any other language. They had a local Thai helper look after him when he was young, and this person persuaded the parents to send him to a local Thai school. (Case S-10)

In Samut Songkhram, the outlook toward the future is split, and the decision seems to depend mostly on the choice of the children. In the case of S-10 above, for example, the family will stay on with the children’s generation who are fully adapted to Thailand, whereas in other cases (such as S-14) remittances to Myanmar are made to ensure a better future back home, and the children are educated in Myanmar for their future in the homeland.

In Mae Sot, the number of Thai speakers among migrant workers is low, especially among women. In 12 of the 18 cases, the respondent said that she/he could not speak Thai. The need to speak the language and to better adapt to the social and cultural context of Thailand seems to be much weaker on the border, which is characterized by a multiethnic and multilingual population. Where the context itself is one of a multicultural frontier, it is easy to get by with Burmese or Karen anywhere in the town, and many of the workers live in communities of migrants.

Curiously, however, physical proximity to the homeland does not seem to be a measure of the strength of migrants’ ties to it. It may seem rather contradictory that many of those on the border who are uninterested in learning Thai also state that they will never go back to their homeland again. Fifteen of the 18 respondents said that they would probably never go back to live in Myanmar. The nuance, in most cases, is less a matter of hope and choice than destiny—they have no place to go back to. One respondent explicitly declared that she would not go back to Myanmar because all of their children had now come to Thailand, even though their status was illegal, and there were no close family members left in their home country. This may be due to the refuge situation as well as sociocultural constitution of the border region itself. It is indeed a frontier for those coming from Myanmar, many under dire circumstances. There is less a sense of crossing the border for better wages and a better future, and more a sense of coming to the frontier in a continuous sociocultural space, where life is far more tolerable than the social, economic, and political conditions at home.

VII Conclusion