Two Versions of Buddhist Karen History of the Late British Colonial Period in Burma:

Kayin Chronicle (1929) and Kuyin Great Chronicle (1931)

Kazuto Ikeda*

* 池田一人, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, 3-11-1 Asahi-cho, Fuchu-shi, Tokyo 183-8534, Japan

e-mail: residue[at]nifty.com

DOI: doi.org/10.20495/seas.1.3_431

The majority of the Karen people in Burma are in fact Buddhist, in spite of their widespread image as Christian, pro-British, anti-Burman, and separatist. In the last decade of British rule, two Buddhist interpretations of Karen history—virtually the first ethnic self-assertion by the Buddhist Karens—were published along with the first Christian version. Writing in Burmese for Burmese readers, the authors of these Buddhist versions sought to prove that the Karen were a legitimate people (lumyo) comparable to the Burman and Mon in the Buddhist world, with dynastic lineages of their own kingship (min) reaching back into the remote past, and a group faithful to their religious order (thathana). This linkage of ethnicity=kingship=religion was presented in order to persuade skeptical readers who believed that the Karen, lacking the tradition of Buddhist min, were too primitive to constitute an authentic lumyo of the thathana world. Analysis of these texts will shed light on the social formation of Karen identity among the Buddhists from the 1920s to the 1930s. This will also lead us to consider the historical processes whereby the quasi-ethnic idioms and logic innate to the Burmese-speaking world were transformed in the face of modern and Western notions of race and nation, and consequently the mutation of Burma into an ethnically articulated society.

Keywords: Karen, Burma (Myanmar), chronicle, historiography, ethnicity, kingship, Buddhism

I Introduction

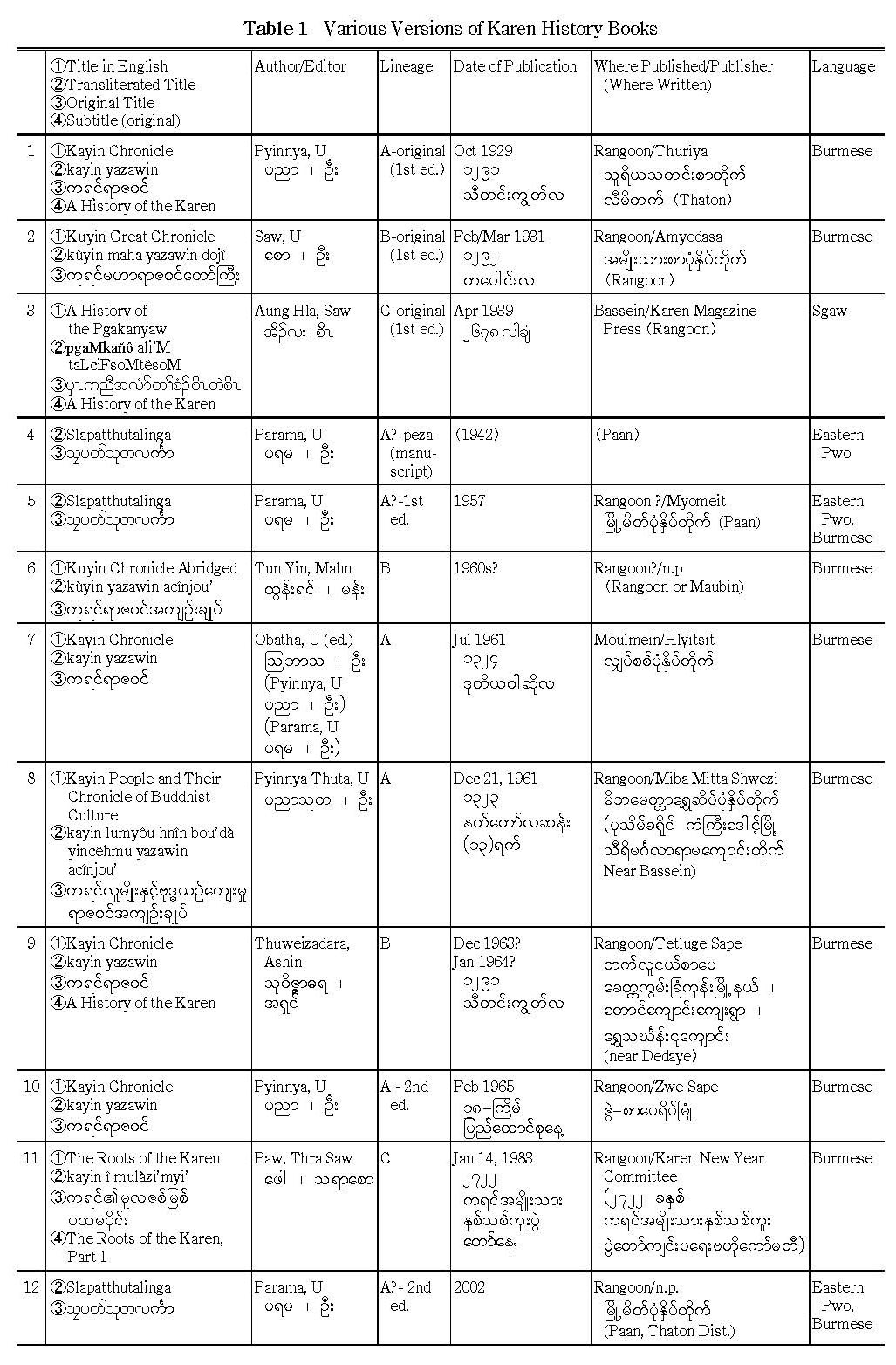

The Karen people in Burma have handed down several versions of their own ethnic history since the beginning of the twentieth century. After Burma became independent, these history books have been reprinted by different publishers, sometimes under false authors, and as abridged versions in small leaflets or mimeographs distributed at Karen New Year festivals and other occasions. They were also photocopied and widely circulated as underground editions both inside and outside Burma among the Karen people.

Attempts to trace these versions to their sources inevitably lead to one of the three following original editions, all of which were published in the last decade of the British colonial period: Kayin Chronicle (kayin yazawin) by U Pyinnya, published in 1929; Kuyin Great Chronicle (kùyin maha yazawin dojî) by U Saw in 1931; and A History of the Pgakanyaw (pgaMkaňô ali’M taLciFsoMtêsoM) by Saw Aung Hla in 1939. “Kayin (kayin)” and “Kuyin (kùyin)” mean Karen in the Burmese language, and “Pgakanyaw (pgaMkaňô)” refers to the Karen in the Sgaw Karen language. The first two works narrate the Buddhist history of the Karen and the third is a Christian version of Karen history.1)

The purpose of this paper is to examine the assertions and logic of the Buddhist versions of Karen history, in comparison with the Christian version, and the motives of these authors in composing the first Karen histories in the Burma of the 1920s.

As an ethnic minority, the Karen constituted the second largest population group after the Burman in the 1931 population census, and the third after the Shan in the 1983 census. The Karen are known for their large-scale conversion to Christianity by American Baptist missionaries in the nineteenth century. Along with the steady increase in the Christianized population and the development of religious networks, the Baptist Karen have also fostered a strong ethnic awareness. They formed the first ethnically oriented organization in Burma in 1881, probably in close association with the British colonial administrators. This organization preceded any of the other ethnic organizations in Burma by at least a quarter-century. Because of their intimate relationships with the Americans and the British, the Karen have been generally represented in Western writings as pro-colonialist during the British regime and anti-Burman after independence in 1948. The Karen National Union (KNU), a Christian-led Karen armed organization on the Burma-Thai border, has been singled out by observers outside Burma as a typical example of ethnic separatism.

Contrary to the widespread image of the Karen as Christian, anti-Burman, and separatist, it has been clear since the 1920s that the majority of the Karen was actually Buddhist. Yet, Buddhist Karen have received scant attention. Kayin Chronicle and Kuyin Great Chronicle are thus significant, as they constitute the first assertions by the Buddhist Karen as a unique ethnic group.

II Buddhism among the Karen

By the eighteenth century, a large part of the people later called Karen had already accepted Buddhism. Buddhism among the Karen came to the notice of the Baptist mission in the nineteenth century and the general impression of the Karen at that time was that they were in many ways already a Christianized people.

The Karen and Christianity

The rapid spread of Christianity among the Karen began with Ko Tha Byu, the first convert baptized in 1828, 15 years after Adoniram Judson arrived in Burma. In the beginning, the American missionaries intended to teach the Karen the Burmese language as a medium of proselytization, but the legend of the “the lost book”2) persuaded Jonathan Wade (1798–1872) to create the Sgaw Karen script in 1832, which was adapted from the Burmese script system. He also invented the Pwo Karen script soon after, though its orthography was delayed till as late as 1852.

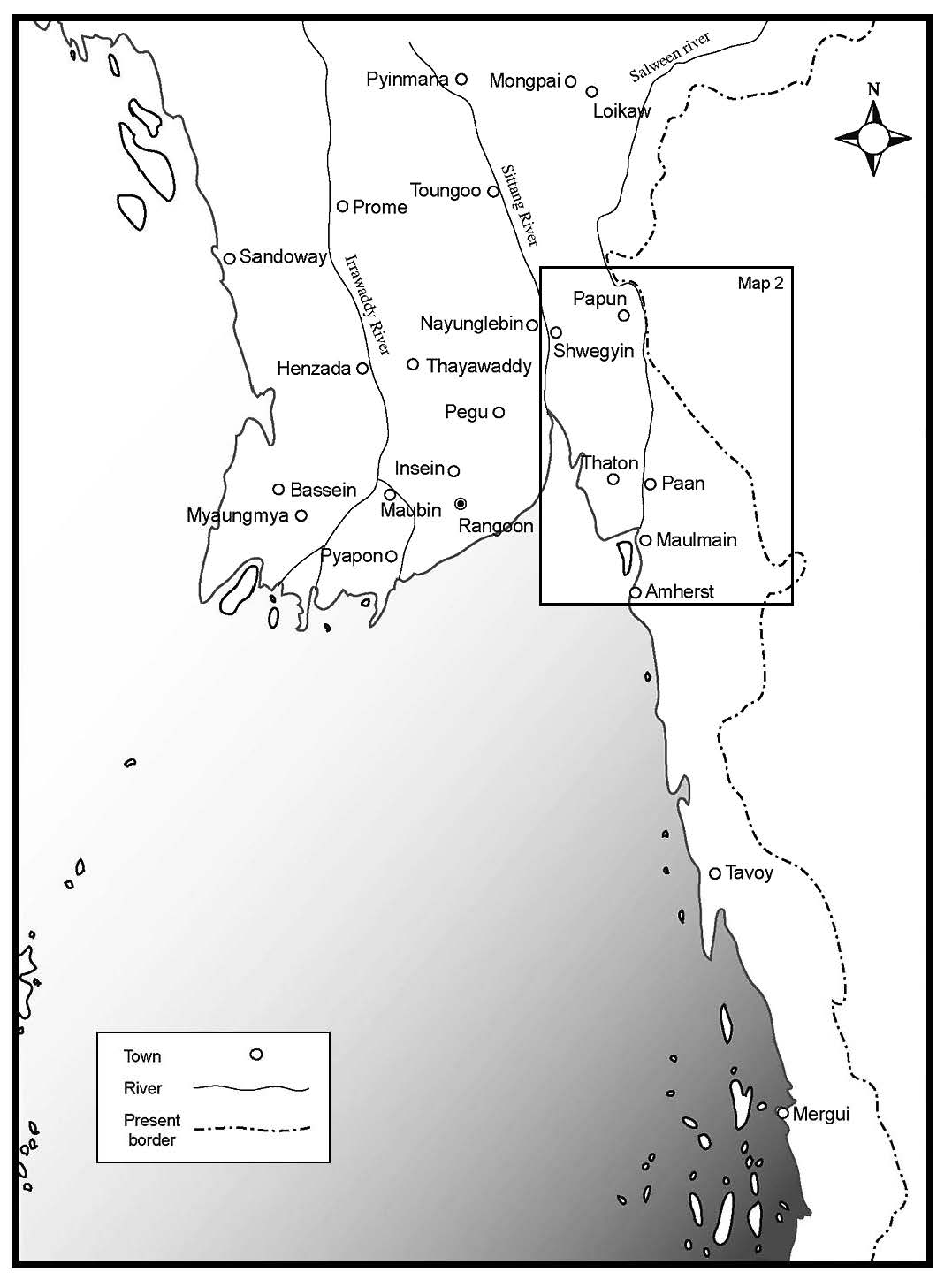

The disputes over whether the Pwo3) language was linguistically related to the Sgaw, and whether these two languages should be categorized as a single language group were not settled until the 1840s (Womack 2005, 116). It was during this Tenasserim period from 1826 to 1852, when the British first colonized Burma, that the language was given its name “Karen” and in principle defined as centered in the vicinity of the Moulmein region and spoken by the people in the range of Lower Burma. The establishment of the two script systems by the missionaries generated the popular conception that Karen was a language or a people comprised of two major subgroups, Sgaw and Pwo.

Francis Mason (1799–1874) played a significant role in the formation of Karen ethnological knowledge. In 1833, only five years after missionary activity began among the Karen, he claimed to have discovered “a fragment of the descendants of the Hebrews” (Mason 1834, 382). In 1860, Mason published the second edition of his work on the natural history of British Burma, with one whole chapter dedicated to the Karen. It was, in fact, the first systematic attempt to describe the Karen as a race or nation, with a distinct language, history, and other elements (Mason 1860, 71–96).

Linguistic and ethnological understanding of the Karen was formed in the first half of the nineteenth century by the Baptists, and this provided a firm foundation upon which various aspects of knowledge and information were added and developed. The British colonialists, for example, came to have contact with the Karen as subjects of their rule only after the annexation of Lower Burma. In the earlier years, colonial officers such as McMahon (1876) and Smeaton (1887) were largely dependent on the knowledge produced by the American missionaries.

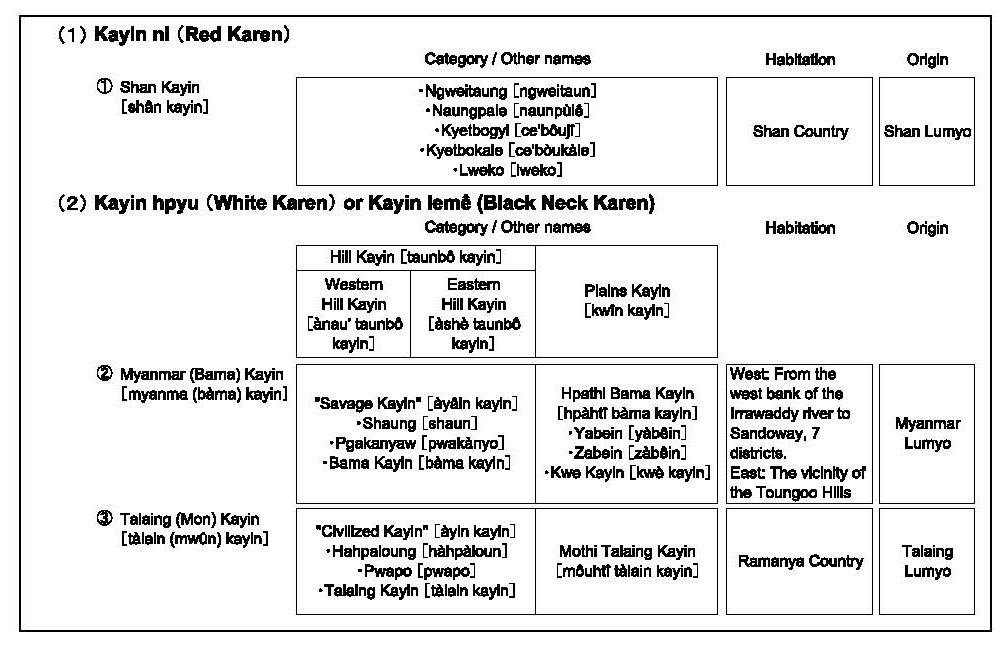

The British officers began to add some new knowledge to that formed by the American Baptists at the turn of the century, notably demographic data and an elaborately classified catalogue of the Karen language subgroups. This was one of the results of British colonization of the whole of Burma in 1886 and persistent attempts at an effective administration—of taxation in particular—over the people who came under their rule. After the linguistic survey of Burma in the 1910s, more “scientifically” categorized subgroups of the Karen, amounting to 16, with Sgaw and Pwo being the largest, appeared in the 1921 and 1931 censuses.

The 1921 census revealed for the first time with statistical precision that the majority (77.3 percent) of the Karen was actually Buddhist. The Buddhist population declined slightly to 76.74 percent in 1931. However, the ethnological details of this religious group have hardly been discussed as compared to the Christian (15.99 percent) and animist (7.23 percent) sections. Official and academic publications of the day, such as social surveys, gazetteers, and ethnographies, focused instead on the animist section of the Karen. This is presumably because the image of the animist Karen was more readily accepted as they were thought to be a more “original” and “purer” part of the tribe, a large portion of whom were mountain dwellers. Christian Karen were already prominent politically and socially in colonial Burma. On the other hand, the Buddhists, the apparent majority in number, remained largely and unnaturally ignored until the end of British rule.

Baptist Karen were one of the first peoples to represent themselves socially as a modern race or nation in colonial Burma. The formation of the Karen National Association (KNA) in 1881 predated the Young Men’s Buddhist Association (YMBA), the first ethnic Burman organization, by a quarter-century. In the early twentieth century, the Karen members of parliament and politicians from the Christian community supported the British rulers, which caused great antagonism among the Burman nationalists. Karen troops in the colonial army were largely composed of Christian soldiers and were often sent to suppress peasant uprisings from the end of the nineteenth century. As Burman newspapers such as Thuriya [The Sun] published articles critical of the Christian Karen in the 1920s and 1930s, the Karen as a whole became perceived and labeled as supporters of British rule and as enjoying preferential treatment under the British administration. This impression was deeply rooted in the minds of the Burman nationalists and common people.

By the end of British rule in the 1940s, a vast amount of knowledge on the Karen had been gathered, principally by the American missionaries and the British colonialists. The British left Burma in 1948 when it achieved independence, and the Americans in the 1960s when General Ne Win took power. Numerous American and British accounts on the Karen have since attained the status of historical records never to be updated, and have become a precious record of the history of the Karen. They constituted quality and abundant historical sources for the Karen people, and since they were written in English, were also easily accessible for Western scholars and observers. However, these records rarely dealt with the Buddhist section of the Karen, focusing instead on animists, from an ethnological perspective, and on Christians as subjects of administration and enlightenment. The Karen people themselves also lost contact with the outside world for some time, after Burma shut its doors to foreigners following Ne Win’s coup d’état. Political scientists and journalists in the West around this time started to publish theses and articles on nationalism, nation-building, and other popular topics of the time, using the Karen in Burma as examples. The Karen were inevitably represented as a Christian and pro-British element in the history of colonial and independent Burma, and in their taking up of arms for separation from the ruling Burman nation, made for a perfect prototype in these articles about ethno-nationalism and insurgency by the oppressed. These Christian, pro-British, insurgent, and separatist images of Karen remain dominant and need to be reexamined when studying the Buddhist Karen.

How, then, have the Buddhist Karen been referred to and how far can their tradition be traced back in Burmese history?

Karen History in Popular Ethnographies

After independence, many books on Karen Buddhism were published in the Burmese language, centering on the Paan area in southeastern Burma. Mahn Lin Myat Kyaw and Mahn Thin Naung are among the most famous eastern Pwo writers with works such as Records of Kayin Culture (Lin Myat Kyaw 1970), Collections of Kayin Custom and Culture (Lin Myat Kyaw 1980), The Eastern Pwo Kayin (Thin Naung 1978), The Beautiful Kayin State (Thin Naung 1981), and The Paan City (Thin Naung 1984). More recent publications include Saw Aung Chain’s A History of the Kayin Nation and Their State (2003). There is also a group of books on the history of pagodas. The histories of pagodas and monasteries on Zwekapin, the holy mountain of the Karen, are well described in The Pagoda History of Mt. Zwekapin (Loung Khin 1965) and A New History of Zwekapin Pagoda (Zagara 1966). Most of the references on Karen Buddhism were published after the 1960s and it is difficult to find literature from before that time.4)

Rare are the books dating from the early twentieth century that treat the history of the Karen. There are two—three if Christian versions are included—lineages of publication on Karen history (see Table 1). The first originates from U Pyinnya’s Kayin Chronicle published in 1929. The monk U Obatha published another Kayin Chronicle in 1961, claiming it as his own original work.5) In the same year, the monk U Pyinnya Thuta abridged the original Kayin Chronicle, and U Pyinnya’s original edition was reprinted in 1965. The second lineage of Karen history descends from U Saw’s Kuyin Great Chronicle of 1931. Based on this, Ashin Thuweizadara published an extracted version in 1963, and Mahn Tun Yin another in the 1960s. Both these seminal texts are written in Burmese for Burmese readers.6)

The third category of Karen history traces its origins from A History of the Pgakanyaw a Christian version of Karen history written by Saw Aung Hla in 1939. There may have been many editions of this work, including the one by Saw Paw shown in Table 1. Photocopied and typed reproductions of Saw Aung Hla’s work also circulated without legal authorization from the Burmese government both inside and outside Burma, especially in the Burma-Thai border area.

Table 1 Various Versions of Karen History Books

We may summarize that three versions of Karen history have been published in Burma and that all the first editions appeared between 1929 and 1939, virtually the last decade of British rule. Little scholarly reference or analysis has been made of these publications. Koenig merely mentioned the title of U Pyinnya’s work in a footnote (Koenig 1990, 267). Than Tun completely rejected U Saw’s history (Than Tun 2001, 76) and Renard thought little of Saw Aung Hla’s historical account (Renard 1980, 42). These Karen accounts may not be reliable if one seeks a Karen history based on “historical facts.” They are, however, significant because they were the first historical narratives and ethnic self-assertions made by the Karen themselves. Therefore one should question why all the first versions of these three lineages were published within such a short period of time, what historiographies they represented, and what conditions and motives made these publications possible. Before examining U Pyinnya’s and U Saw’s works, we need to look at the general state of affairs of Buddhism among the Karen in colonial times to situate the two books in the Buddhist context.

Two Kinds of Buddhism

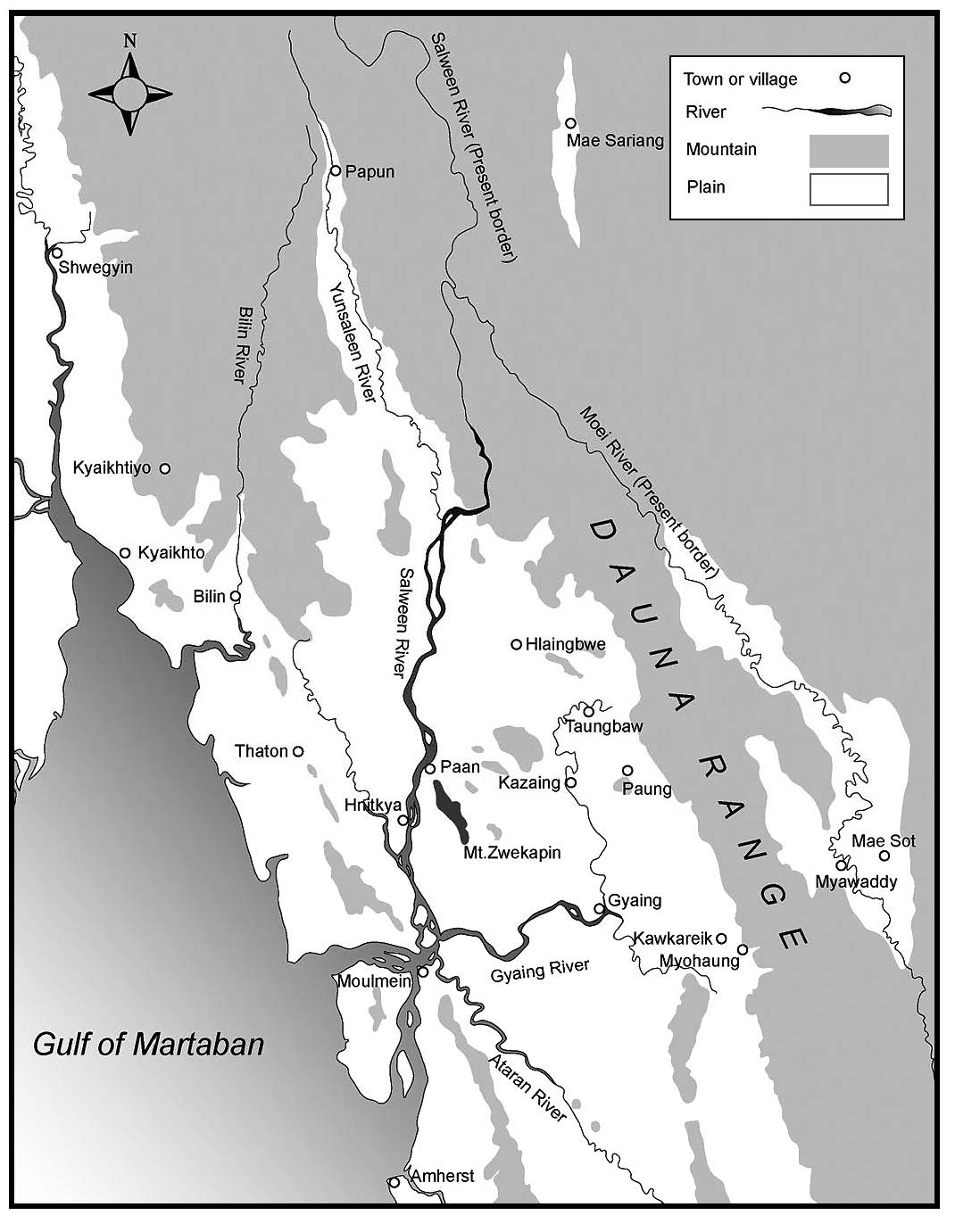

Two theories exist regarding the origins of Buddhism among the Karen. One looks to the Buddhistic elements of the various cult movements that sprang up in the area stretching from the Yunsalin River valley to the Paan plain in southeastern Burma. The other turns to the Karen Buddhism based in the Paan area, which had a close relationship with the Buddhist orthodoxy centered in Ava and Mandalay, the royal capitals of the Burmese- speaking world, and their vicinities.

The earliest Baptist missionaries, such as Judson, Boardman, Wade, and Mason, encountered a number of religious movements during the course of their missionary work. Judson reported in his letter to the headquarters in America that the Karen in the Yunsalin valley had begged the missionaries for Christian preaching. They had a leader called “Areemady” with apparently Buddhistic features. In 1856, after the Second Anglo- Burmese War, the colonial army suppressed the “revolt” led by a minlaung, a pretender to the throne. These millenarian Buddhisitic aspects among the Karen were transformed and inherited by cults such as Leke (formed at Hnitkya village in Paan in 1860), Telakon (founded at almost the same time in Gyaing), Phu Paik San (1866), and others.7)

The other stream of Karen Buddhism can be grasped in its relationship with the orthodox Buddhism of the Burmese world. It is a common notion that the heart of Karen Buddhism is situated in the Paan area, and the origin of this ethnically defined Karen Buddhism is often ascribed to Phu Ta Maik, a legendary Pwo Karen monk of the eighteenth century said to have created the Pwo Karen monastic script.8) This script had spread by the second half of the nineteenth century, and the Yetagun monastery, which was established in 1850 on the summit of the Karen holy mountain of Zwekapin, became the center of its propagation. Hpoun Myint studied Pwo Karen parabaiks (folded palm leaf manuscripts) in the late 1960s and collected 75 parabaiks dating from 1851. Of these, 52 are categorized as translations of Buddhist scriptures and commentaries, and 25 as astrology, tales, and history; 36 were translated from the Mon language, 21 from Burmese, and 4 from Pali sources.

Although Phu Ta Maik legends are related in the language of (Pwo) Karen nationalism, actual Buddhist writings in the Pwo script barely convey Karen nationalistic aspirations. This could lead us to suppose that the Pwo Karen script was in fact created to connect Pwo Karen speakers of the day with the more universal sphere of Buddhism, the texts of which were written and expressed in the Burmese language.

U Pyinnya and U Saw’s Karen histories are situated in the context of the second stream of Karen Buddhism mentioned above. This is particularly true for U Pyinnya, who lived in the city of Thaton, one of the entrances to the Paan plain, and who made frequent visits there.

III Authors

The backgrounds of the two Buddhist Karen histories should first be examined. What was the relationship of the authors to Karen Buddhism? What kind of bibliographies and styles did they refer to in writing the history of their people?

U Pyinnya

Little is known about U Pyinnya except that he was a Buddhist, probably born in the 1860s,9) lived in Thaton and that he was relatively famous as a writer when he wrote Kayin Chronicle. He also published Thaton Chronicle Collected and Abridged (1926), based on Mon chronicles, and A History of Shwemawdaw Pagoda, a famous stupa in Thaton.10) U Pyinnya’s real name was U Myat Maung and he called himself Thaton U Myat Maung in a newspaper article (Thaton U Myat Maung 1929). It has always been common practice in Burma for minority people to adopt Burmese names and U Pyinnya seems to have belonged to one of the linguistic subgroups of the Karen—the Pwo, Sgaw, Pao, or others. “Pyinnya” means knowledge in Pali and is also quite a common name for a Buddhist monk. He was not, however, a monk when the book was published. The Pao people have a custom of keeping monkhood names even after they return to secular life. Therefore, U Pyinnya might have been a Pao.

The city of Thaton is located southeast of Yangon and was once a royal capital of the Mon kingdom. It is said that the region was the most prosperous Theravada land until the invasion by King Anawyatha of the Pagan dynasty in 1057. Mon Buddhism also occupies an important place in the history of Burmese Buddhism, one that precedes the Burman influence. Thaton is a city of Pao people, who can be found in the southern Shan States in the north, and in the Thaton area in the south. Most of the population (about 223,000 in the 1931 census) are Buddhist and have close relationships with the Mon, Pwo, and Sgaw Karen of the land. Based on linguistic similarity, the Pao have been grouped with the Sgaw and Pwo in social statistics. In the independence negotiation period, U Hla Pe, a famous Pao politician native to Thaton, was appointed vice-president of the newly born Karen National Union (KNU) in 1947 and he claimed that the Pao are one of the Karen groups.

U Pyinnya’s principal source was a legendary “document of Kayin Yazawin written in the Pao language.”11) In 1908, when U Pyinnya visited a childhood friend of Shan origin, who was then a priest in the village monastery at Myohaung, near Kawkareik, he came across the document in the form of a folded parabaik made of Maingkhaing paper.12) With the help of a Pao layman and others, including a friend who was proficient in Pali, Kayin, Shan, Mon, and Burmese, the document was translated into Burmese in three days. This episode shows that around the Thaton area in those days, the Pao were seen as a people so close to the Kayin that there was nothing strange about Kayin history being written in the Pao language. Other references for U Pyinnya’s book included Burmese written chronicles such as Hmannan Yazawin [Glass Palace Chronicle], Mon chronicles, and other scriptures translated from Mon.

As such, U Pyinnya’s Kayin Chronicle is set mainly in the Paan region. Paan is, in short, where the original “document of Kayin Yazawin in Pao” was discovered, where Phu Ta Maik invented the Pao script, where numerous Pwo Buddhist scriptures were produced, and the home of Karen Buddhism. More importantly, eastern Karen, who surely inspired U Pyinnya’s Karen history, interacted closely with other peoples like the Pao, Mon, Burman, Shan, and others, which provided U Pyinnya with abundant resources in writing his version of Kayin history.

U Saw

Biographical information on U Saw is similarly limited. On the cover of his book, it is stated that he was a Pali translator in the translation section of the Secretariat. However, his name is not in any of the volumes of the Civil List of Burma (Government of Burma 1930, etc.), so he might have been a non-gazetted officer. His dates of birth and death are unknown, but his middle-aged appearance in the photograph on the first page—if taken at the time of publication—gives us a hint that he may have been born between the late 1870s and early 1890s.

U Saw referred to the same major bibliographies as U Pyinnya, that is, the chronicles and pagoda histories in the Burman, Mon, and Shan scripts; scriptures; birth tales of Buddha; proverbs; and folklore. What is unusual is that U Saw also consulted a wide range of other sources such as “ancient manuscripts and scripts in India,” “Greek and Italian classics,”13) and contemporary publications of Indian history by Indian and Western authors. This shows that, as a native officer in the huge government organization of colonial Burma, he was exposed to a variety of data collected and brought to Burma by the British rulers. However, he seems not to have known about U Pyinnya’s publication in October 1929, writing in the preface that, “It is surprising that no [Karen] chronicles have ever been published” (U Saw 1931, 1).

In U Saw’s case, drawing on a multitude of sources for reconstructing Karen history imparted an unfocused and monotonous quality to his writing. This is especially striking when compared to U Pyinnya’s lively, diversified, and elaborate version of Karen history. This difference stems evidently from U Pyinnya’s use of the Pao-written Kayin chronicle. This begs the question why U Saw did not make use of this reference as well. This is because the Karen in the west, where U Saw came from, had fewer written resources containing historical memories than the eastern Karen. Even today, from the center of so-called Karen Buddhism in the Paan region, the western land is viewed as “a frontier where Karen Buddhist culture has rarely flourished” (Interview with Hsayadaw Pt, a Karen monk, in the Paan region in 2003).

If U Saw could not draw upon such unique sources as U Pyinnya, why did he not make use of the abundant materials of the Christian Karen, which were within easy reach of a civil servant like himself? He must have had access to the library of the Secretariat, the Government Book Depot on Judah Ezikiel Street, or the Bernard Free Library, which was reputed to have a Pali collection in its inventory. If he also had a good command of the English language, Lowis’ The Tribes of Burma (1919) and Scott and Hardiman’s Gazetteer of Upper Burma and the Shan States (1900), and piles of other gazetteers should have been accessible. In addition, there was also a large amount of Baptist materials dealing with the Karen. He could have sieved through the Christian touches and added Buddhist flavors to those materials, just as Saw Aung Hla did. Why did he, as well as U Pyinnya, neglect Christian sources and use only Buddhist writings?

Modes of Historiography

There are two major modes of historical narratives in early twentieth-century Burma. One is Thamaing (thàmâin), a type of account of Buddhist history that has actually become a general term meaning history. The other is Yazawin (yazawin), a mode of historical narrative with the king as its sovereign being. Both U Pyinnya and U Saw were familiar with these two types of historical narratives and made use of Buddhist scriptures, their commentaries, and various chronicles in Burmese and Mon. Moreover, the titles of their works contained the term “Yazawin.”

“Yazawin” is a term originating from the Pali words “raja” (rāja, king) and “vamsa”(Vaṃsa, history), and is usually translated as “chronicle.” Among the chronicles written in Burmese, the oldest is Yazawin Gyaw, which appeared in 1502. Since then, more than 20 versions, including Toungoo Yazawin (sixteenth century), Maha Yazawin (1724), Maha Yazawin thi’ (1798), Hmannan Yazawin (1832), and Konbaung Set Maha Yazawin-doji (1905) have been compiled. Those chronicles are characterized by Buddhist ideas of time, space, and cosmology; frequent reference to commentaries of scriptures; and above all, descriptions of royal achievements of mins (mîn), or kings of the dynasty. The mins’ ancestors are always the Shakya tribe of Buddha and Maha Thamada, the first worldly king of human beings. “The kings were the only subject dealt with in the Yazawin and others simply play supporting roles” (Ohno 1987, 19–20). Mins are definitely the sovereign being in the authorized version of Yazawin Yazawin were therefore historical accounts recognizing the achievements of kings and dynasties and legitimizing their rules.

Both U Pyinnya and U Saw adopted the Yazawin style for their historical narratives of the Karen people. This leads us to question the meaning of history writing. When they published the two Karen Yazawin, kingship had already been extinguished with the conquest of the Kongbaung Dynasty by the British. Why did U Pyinnya and U Saw embrace the style of the royal narrative after the extinction of the dynasties? What did they intend to convey in composing a dynastical history of the Karen, who have ordinarily been considered a people without such a dynastic past? Moreover, why did they employ the Burmese language, not Karen, for their own history?

IV Histories

The texts by U Pyinnya and U Saw, as well as Saw Aung Hla, are full of stories never told to readers outside Burma; scholars have therefore not taken them seriously (for instance, Than Tun 2001, 76). It is generally considered that the history of the Karen people before the nineteenth century is fragmented because they lacked written sources of their own and the Burmese-speaking dynasty in upper Burma did not make much mention of the Karen. The “Kayin yazawin document in the Pao language” that forms the basis of U Pyinnya’s vivid and detailed text has never been found by local researchers, and events in Pgakanyaw dynasties were thought to have concerned the other ethnic peoples. It is therefore very easy to dismiss these texts as spurious.

However, U Pyinnya said he spent more than 20 years on his work and Saw Aung Hla at least 7 years. If you ask any old Karen informant about the history of his people, you will surely be offered one of these three texts. These Karen history books contain some sort of ethnic aspiration shared by the people who claim to be Karen, which the authors channeled in their books. Expressed, for example, is the ideal and idealized image of the Karen’s relationships with other peoples in the Burma region. Such images can be interpreted as the desires of the authors generated from negotiations in the society in which they lived. What is more, the authors were motivated enough to publicize their desires, and the first editions of the three books were all published between 1929 and 1939, which is, in a sense, a very short period of time. What were the social conditions that enabled and encouraged the authors to venture into the demanding labors of publication?

Let us begin with the authors’ desires, which are expressed in images of the Karen. I will attempt to outline the contents of the two Buddhist versions of Karen history, which were hitherto unknown to the world outside Burma. The authors’ desires are to be found in the details of their histories, which were described in close connection with Burman dynastic history. They are embarrassingly detailed, subtle, and almost meaningless to outsiders, but readers should by the end be able to discern the indispensable elements of ethnicity, religion, and kingship lying behind these versions of Karen history.

Kayin Chronicle (1929)

U Pyinnya’s Kayin Chronicle is composed of 3 parts and 77 sections.14) The first part deals with the creation of the world, the 101 lumyos (lumyôu) or people who lived there, an outline of Shan Kayin history, and the first royal lineage of the Mon Kayin (Zweya dynasty). The second part focuses on the second lineage of the Mon Kayin (Pa’awana dynasty), and the last part the history of Myanmar Kayin. U Pyinnya states that the Kayin people are divided into three subgroups, each prefixed with the name of other major peoples of Burma—the Shan, Mon, and Burman—and even claims that each Kayin originated from the people in question, and that in the beginning all the people of Burma had a single ancestry called the Byama (Brahman) lumyo 15)

Dovetailing with this explanation is U Pyinnya’s interesting etymology of the Kayin. He begins with the word “Kayin,” which is supposed to be a Burmese word indicating Karen, not with Pgakanyaw in Sgaw or Phlong in Pwo, and outlines three theories regarding its etymology. The most elaborate one is that it derived from Karannaka, an old name for Thuwannabumi, the ancient capital of the legendary Mon kingdom. Those who lived in the plain of Karannaka became Mon, and those who dwelt in the forest became Kayin.16)

Two lineages of the Mon Kayin dynasties, whose homeland is in the ancient Mon kingdom called Ramanya, are at the heart of U Pyinnya’s history. Thaton has existed since the beginning of the world and was called Karannaka until 50 years before the birth of Buddha. The Zweya dynasty has its origin in the guardian town established by Teithatheika, king of the Mon after he drove out the rival state of Yodaya17) in the east. A seven-month-long banquet was held at the military base set at the entrance of the only pass between the Mon kingdom and Yodaya. At the end of this feast, the king appointed a Kayin as general of the guard. This Kayin, named Einda, was well-known among the Lawa, Loe, Mon, and Kayin of the land, and was given five kinds of regalia, 100,000 soldiers, power of taxation, the fiefdom of Zweya Myo, and the title of Saw Banya Einda Thena Yaza. Zweya Myo became independent together with six of the subordinated myos,18) Myawaddy, Mekalaung, Kyaik, Taungbaw, Paung, and Doungmwe, after the death of King Teithatheika. Subsequently each of the six myos also obtained independence. Mekalaung and Doungmwe, the most easterly located, were later annexed by Yodaya. The author gives detailed descriptions of the origin and the rulers (myosa) of the other four myos and Zweya, including 2 rulers in Myawaddy, 9 in Paung, 11 in Kyaik and 28 in Zweya. At the end of Part I, there is a section titled “Lesson,” which briefly explains that the Zweya dynasty subsequently endured as part of the Myanmar dynasty and was incorporated into the British Empire through the 1825, 1852, and 1885 wars.

The history of the Pa’awana dynasty of the Mon Kayin is told in Part II. Pa’awana is the name of a forest at the foot of Zwekapin, which has existed for a long time, predating even Buddha’s birth. In this forest there lived a hunter called Laswe, who presented game from the woods to the Mon king Teithatheika when he successfully defended the kingdom from the invasion of Yodaya. The king was so pleased that he offered the same rewards to Laswe as he did to Einda, and permitted him to clear the Pa’awana forest and found a myo, or capital city. U Pyinnya insists that the history of the Pa’awana Myo began 14 years prior to Buddha’s enlightenment and lasted until the reign of King Manuhari in the twelfth century. What is outstanding in the history of Pa’awana is the existence of Zwekapin, the Kayin holy mountain, and that the historical account of the pagoda on the top of Zwekapin includes Buddha’s visit during the reign of Laswe.

The Pa’wana Myo was also independent with five surrounding myos after the same Mon king passed away, and soon these myos—Kyaing, Takyaing, Hlaingbwe, Kazaing, and Takwebo—also gained independence. Lists of the rulers of each myo are attached. There were 13 in Takyaing, 13 in Kyaing, and 7 in Kazaing, but that of Hlaingbwe is missing because of “damage to the pages in the original Kayin Chronicles in the Pao language.”

Apart from these two lineages of the Mon Kayin, U Pyinnya also relates the history of the Shan Kayin and Myanmar Kayin based on the Hmannan Yazawin and other Burmese and Mon chronicles. Events related in the Myanmar Kayin section evidently correspond with Hanthawaddy history, including the famous story of Kwe Kayin, which U Pyinnya claims to have been Myanmar Kayin. When the Guardian General of the Hanthawaddy was assassinated, there emerged a minlaung among the Kwe Kayin. He was accepted by the people and succeeded the throne. He was called Hsinkyashin, or “Possessor of Tiger and Elephant.” The description of the Shan and Myanmar Kayin and that of the Mon Kayin occur at different times. Whereas the former two Kayin histories are as recent as the eighteenth to nineteenth centuries, the latter begins with the time of Buddha’s birth and its heyday is illustrated up to the fall of the Mon kingdom in the eleventh or twelfth century. This information is apparently drawn from the references U Pyinnya made use of.

Kuyin Great Chronicle (1931)

U Saw’s book contains 16 chapters with a short introduction and conclusion. The author presents his vision of history from the creation of the world, the rise and fall of the people in India, which is the homeland of all lumyos in Burma, to migration to Burmese soil. In contrast to U Pyinnya, U Saw’s historical construction does not follow a time line and is sometimes confusing. Moreover, he does not focus solely on Kuyin history but tends to dwell on pre-history before the migration to Burma.

Chapter 1 is entitled “On the foundation of the countries outside the Zabudeik Island (zanbudei’ cwûn)” and elaborates on the origin of the world and the beginning of the worldly nations, concentrating on Myanmar and Mon countries. Among these stories of the time before the departure to Burma (Saw 1931, Chapter 4-A), that of King Inkura is important. Inkura hailed from a kingdom on the Ganges River and is considered the ancestor of the Kuyin people. He arrived at the central plain of Myanmar and sailed down the Irrawaddy River to Dagon (dàgoun), where he established a myo called Athitinzana (àthìtinzànà). This myo later developed into the capital of the Ramanya country. This is usually considered to be an ancient name for the Mon kingdom, but U Saw insists that it was in fact a Kuyin name (ibid., 38–39).

In Chapter 5, U Saw argues that the Kuyin (![]() ) name originated from King Inkura (

) name originated from King Inkura (![]() ) , the first syllable (

) , the first syllable (![]() ) having been omitted. Thus it should be spelt as Kuyin with a tachaungngin (

) having been omitted. Thus it should be spelt as Kuyin with a tachaungngin (![]() ) “u” sound, and not the usual Kayin (

) “u” sound, and not the usual Kayin (![]() )f .19) Despite their noble origins, the Kuyin gradually came to be seen as a savage and uncivilized lumyo as they declined contact with peoples of bad habits and retired to the mountains (ibid., 46).

)f .19) Despite their noble origins, the Kuyin gradually came to be seen as a savage and uncivilized lumyo as they declined contact with peoples of bad habits and retired to the mountains (ibid., 46).

From Chapters 6–10, despite several references in the titles of some chapters, U Saw barely touches upon the Kuyin themselves, but provides ancient historical accounts of Shakya tribes and others.

In Chapter 11, U Saw turns his attention somewhat to the Kuyin. According to an explanation in a Mon chronicle, Mon living in the myos called the people living in the forests and mountains kari, which later transformed into Kuyin lumyo (ibid., 99). Later in the same chapter, U Saw locates the remote ancestor of Kuyin in the Shakya lineage, which in time developed into the three states of Dewadaha, Koliya, and Kapila. After the fall of these states, the people migrated to Burma and were divided into three peoples known as Pyu, Kan’yan, and Thet. And it is from the Kan’yan that the Kuyin descends. However, U Saw does not give a consistent explanation of how Kolia and Kan’yan relate to Inkura.

Again, from Chapters 12–15, in spite of mentioning the Kuyin in some of the titles, U Saw gives no further accounts but simply repeats similar descriptions. When the author finally reaches the history of the Kuyin in the last chapter, entitled “To show how Kuyin lumyos spread throughout the Myanmar country based on other prominent Hsayadaw’s opinions,” he reiterates the process of migration and promises to deliver the details in a second volume of the chronicle (ibid., 183), but this did not materialize. Listing the dynasties and kingdoms that flourished in Burmese history, U Saw emphasizes that “there is no denying that within any of these big countries, any of the states under the umbrella of the kings, any myos, any ywas [villages], Kuyin lumyos can be found as offspring of the Koliya king’s lineage. As Koliya-Shakya descendants, they have lived in the whole country, including islands, kain land [sandbank of rivers], and valleys” (ibid , 184). He concludes his book by claiming that the Kuyin is a lumyo faithful to Buddha’s teachings, and though they have been seen as a savage lumyo because they avoided contact with other lumyos, they are no less excellent Buddhists than others.

Focuses

U Pyinnya and U Saw, in a sense, carved out what the Karen should be, rather than what they were, particularly in terms of their relationships with other Buddhist lumyos and their dynastic pasts.

The Kayin people in U Pyinnya’s Kayin Chronicle share the same ancestry as the Mon, Burman, and Shan, maintaining a firm belief in Buddhism and their own kingships since the very beginning. The three major subgroups of Karen—the Mon Kayin, Myanmar Kayin, and Shan Kayin—have their immediate origins in the people with whom their names have been associated, but the Mon are the most intimate with the Kayin as the word Kayin is etymologically ascribed to a Mon term, and historically they have close relations. Accounts of the Mon Kayin lineage are, consequently, the main concern of U Pyinnya.

U Saw’s Kuyin are, on the other hand, not necessarily familiar with the Mon, but do share a single origin with other peoples in Burma. The Koliya people of ancient India were their lineal ancestors, going back to the Shakya tribe of Buddha. Upon reaching Burmese soil, the Koliya split into the three legendary peoples of Phyu, Kan’yan, and Thet. The Kan’yan were Kuyin and their name was inherited from Inkura, an ancient Indian king. Most of the elements in U Saw’s Kuyin history derive from authoritative representations of India, the land of Buddha, and his version present the peoples in Burma as being ruled by faithful kings.

The Kayin and Kuyin as described by these two Buddhist authors are more distinctively characterized as compared to that of A History of the Pgakanyaw by Saw Aung Hla. This Christian author’s focus is the narration of the Pgakanyaw’s struggle against persistent Buddhist integration. He describes the Pgakanyaw as a lost tribe of Israelites and one of the earliest settlers of the uninhabited ancient Burma after having endured a long journey away from their biblical home. They possessed a unique language, script, culture, and kingship, and managed for many centuries to hold on to a monotheistic faith, which was to be later fulfilled as Christianity. They ran their own kingdoms, warded off severe oppression by the Mon and Burman, endured continuous pressures of forced conversion to Buddhism, and finally restored the glory of their people during the British colonial period.

These three Karen histories are similar in that they narrate the story of an ethnic and sovereign people called Kayin, Kuyin, or Pgakanyaw, maintaining unique kingships based on a religion that embodies the principles of their respective worlds. In short, they have the indispensable elements of people or ethnicity, kingship, and religion. Naturally, people, or lumyo, are central to their narration because these are texts on the history of the Karen people. But the term “Karen people” is relatively new in the historiography of Burma, so careful consideration is required in this regard.

Having laid out the motivations and assertions of the authors, the logical structure with which they attempted to persuade readers is to be examined next. In order to present a convincing case that the Kayin/Kuyin are a legitimate lumyo in Burma, the authors had to employ a reason and logic acceptable to Burmese-speaking Buddhist readers. Therefore we should turn our attention to how the Kayin/Kuyin are embedded in this world accorded to the understandings regarding people (lumyo), kingship, and religion.

V Logic

What we are interested in here is not the structure or appearance of the worlds in which the Kayin and Kuyin were situated, but the existing concepts of people (or ethnicity), kingship, and religion that sustained the Kayin or Kuyin within these worlds.

In U Pyinnya and U Saw’s histories, people (ethnicity) appeared as lumyo (lumyôu), meaning “human kind/seed,” king as min (mîn), and royal lineage as minzet (mînze’), minnwe (mînnwe), and nan-yo (nân yô). It is, however, very difficult to find words referring to religion or Buddhism in their books. This is clearly different from Saw Aung Hla’s Christian version of Karen history. Christianity is his preoccupation and is constantly evoked as kharit ata bhutabhaa (khari’L ataLbhuFtaLbhaa), whereas Buddhism is termed so kotama bhuda ata bhutabhaa (sô kôtama’Mbhu’Mda’M ataLbhuFtaLbhaa) or simply bhuda ata bhaa (taLbhuFtaLbhaa). Buddhism is described as a totally foreign religion to the Pgakanyaw people, forced on them by the Burman and the Mon. It is therefore elaborately and repeatedly examined and placed in the same category of tabhutabhaa (religion) as his own Christianity.

Thus far I have called somewhat carelessly U Pyinnya and U Saw’s representation of religion “Buddhism,” but in fact the word scarcely appears in either of the texts. Practically the only time the word appears is when the authors refer to Christianity. Not coincidentally these passages also contain the authors’ assertion of the Kayin/Kuyin as an indispensable lumyo with a past history of kingship. We could infer that it is this “otherness” of Christianity that brings out, by contrast, the norms and worldviews of the Kayin/Kuyin.

U Pyinnya’s Kayin

As shown above, the Kayin in U Pyinnya’s history are a lumyo that share a single ancestor with the Mon, Burman, and Shan, and who have been devoted believers of Buddha’s lessons since the beginning. U Pyinnya highlights in particular their relation with the Mon lumyo. Each lumyo has virtuous kings (min). U Pyinnya sought to prove that the Kayin were an authentic lumyo with a dynastic lineage of their own min, and faithful to their religious order. We need to take a closer look at this lumyo =min= religion scheme, examining in particular the paragraphs from section 72 at the end of Part II, entitled “Special Note,” which summarizes U Pyinnya’s ideas about the two lineages of Mon Kayin histories. Interestingly it is almost the only part that mentions Christianity.20)

He expounds his version of the history of lumyo. At the beginning, every lumyo had its own virtuous rulers and were self-governing, but influential lumyo with able rulers like the Burman gradually became dominant over other lumyo such as the Mon and Kayin. In the end, however, all these lumyos in Burma were conquered by “diligent, wise” and “greedy” Europeans. U Pyinnya continues:

Not a long time ago, there appeared “a Kayin script” invented by wise Christian (khari’yan badha) missionaries (thathana pyù dò). In this way, our unique literature and original knowledge were long lost, our learning tradition (athin acâ) also disappeared . . . so scriptures (sape pariya’), as well as old records such as chronicles (mînze’ yazawin), tales (pounpyin), Buddha’s birth stories (niba’), poems (gabya) and verses (linga) were gone. This has made people think that the Kayin people did not actually have their own scripts. Not knowing old books, knowledge, or chronicles . . . people have come to say that the Kayin didn’t have their own kings in the past. Although it was said that the Scriptures were lost together with the preaching of Buddha (thahtana-do), precious words of the scriptures . . . were written on golden leaves and kept in the hands of Alawaka.21) Similarly, inscriptions, old records, or other books of chronicles and biography regarding Kayin kings must have been kept somewhere. As a matter of fact, this Kayin Chronicle you are now reading was restored from an old document written in the Pao-Taungthu language . . . .

If there had been no “old documents of the Kayin chronicles” and no Kayin kings, it would be tantamount to saying that the people of Buddha (payâ lumyôu) are not Buddhist, that people of arhan (yàhanda lumyôu) are not arhan, or even that any people (lumyôu) are not human (lu). If one is trained enough to attain paramita to be a man of Buddha, or a man of arhan, then he is a man of Buddha or arhan. How on earth has the Kayin lumyo been able to survive without their own kings (mîn)? (Pyinnya 1929, 140–143)

In this way, in summing up the most important part of the Mon Kayin chronicles, U Pyinnya argues for the lost Kayin literature and claims the unquestionable existence of Kayin kings in the past. Most interestingly, it can be inferred that U Pyinnya intentionally avoided writing about Christianity. On the contrary, he calls his own religion thathana and never uses the word bouda batha(Buddhism).22) Secondly, the fundamental human unit in his world is the lumyo. It has, or should have, its own lineage of kingship as well as a unique written scripture (batha sa), literature (sape), and tradition of scholarship (athin aca). It is the lumyo, and not the min, that is the subject of his text.

These observations provoke further questions, which are similar to those raised by U Saw’s text. Let us then first proceed to examine U Saw’s history.

U Saw’s Kuyin

U Saw’s only reference to Christianity appears in Chapter 11: “To cite and show the assertion made by Hsayadaws of Mon Yazawin.” This is located after the “Note (hma’hce’)” section and is entitled “Special Note (ahtû hma’yan).” There are numbered “Notes (hma’hce’ or hma’yan)” in U Saw’s work making up for the shortage of descriptions or summarizing each section, but this is the only place where a “Special Note” appears, demonstrating U Saw’s emphasis.

Prior to this “Special Note” section, U Saw summarizes again that the Koliya lumyo of India split into three ancient lumyos after arriving in Burma. He then suddenly touches upon religion (badha) among the Kuyin:

Special Note: In Myanmar country, there are many Kuyin lumyos and two religious Kuyins— Buddhist Kuyin (bou’dà badha kùyin) and Christian Kuyin (khari’yan kùyin)—can be found among them. Now, let us put aside the Christian Kuyin for the time being23) and think about the past, present, and future of the Buddhist Kuyin, and we will see the truth as found in the saying “the flow of a river may become choked with sand, but the flow of a people (lumyôu luyôu) can never be dammed.” The Kuyin lumyos originate in the Shakya tribe of Buddha (thàcathakìya), and hold a legitimate lineage to the Koliya kingship. They are Buddhist people (bou’dà badha lumyôu) and the lineage of Buddhist kings (bou’dà badha mîn nwe) and now attain the name of Kan’yan. However, the blood of Shakya never extinguishes, but is inherited from generation to generation and the genealogy of our people (amyôu anwe) will never cease. (Saw 1931, 106)

U Saw next examines the mingando, an article (or a part of a ceremony) used in a ritual conducted for the deceased member of a royal family, which is quite identical with that “presently [at the time of U Saw’s publication]” used by Kuyin lumyo in ayoutkaubwe 24) a traditional ceremony in one of their festivals. He concludes this “Special Note” section by remarking that the Kuyin are surely from the legitimate “Koliya lineage (koliyà nân yô)” (ibid.).

Three aspects of the above-mentioned section should be pointed out. Firstly, while U Pyinnya describes his religion as thathana or taya and Christianity as badha, U Saw calls both his own religion and Christianity badha. However, it should be pointed out that the usage of bouda badha is found only in this citation, and could have been employed for the purpose of comparison with other religions. U Saw is, in general, as vague as U Pyinnya when referring to religion. Both writers knew the usage of badha as religion, but U Pyinnya is more cautious and never applies the word badha to his own religion. Secondly, the saying “the flow of a river may become choked with sand, but the flow of a people (lumyôu luyôu) can never be dammed” is also cited on the first page (ibid , i) and in the second paragraph to last in the final chapter (ibid., 184). It is a leitmotif of his Kuyin history, articulating his assertion that the Kuyin are an ancient people that have survived. In this respect, in a similar way to U Pyinnya’s writing, the subject of every sentence is the lumyo. Lastly, as the Kuyin are of the Shakya lineage, they are Buddhist people (bou’dà badha lumyôu) and of the Buddhist kings’ lineage (bou’dà badha mîn nwe). Symbolically, in this expression, people (lumyôu) and kingship (mîn nwe) are connected only through the concept of Buddhism (bou’dà badha).

Religion, Kingship, and Ethnicity

For both U Pyinnya and U Saw, the Kayin/Kuyin are the lumyo (ethnicity) that have a history of kingship (minzet) faithful to the Buddhist order (thathana). They therefore share a similar logic in the conceptual relationship between religion, kingship, and ethnicity in order for their assertion to be persuasive to Burmese readers.

Firstly, with regards to the relation between religion and ethnicity, U Pyinnya and U Saw basically ignore Christianity, but are at the same time hardly conscious of their own religion, which is discernable through such terms as thathana and taya appearing sporadically in the texts. Saw Aung Hla, on the other hand, has a totally different attitude towards his own religion and the enemy’s. What he fears most is the loss of Pgakanyaw as a nation. Without putting up a fight, the Pgakanyaw might have been deprived of their unique language, script, culture, and religion by Burman and Mon Buddhists. Thus Saw Aung Hla is keenly aware of the religious factor. In other words, U Pyinnya and U Saw’s Kayin/Kuyin live in a world that is absolutely and harmoniously ruled by a single prevailing principle called thathana, or Buddhism. The fundamental human unit in this world is lumyo, but this lumyo has a religious limit. Even though outsiders may consider the Christian Karen as Kayin lumyo, for these two authors the heathen Kayin are not counted in the world of thathana as a member lumyo.

A question should arise if we pay attention to this self-other relationship defined by ethnicity and religion. During the 1920s–30s in Burma, when their works were published, it was already well known, in the countryside as well as in the city, that there were many Christian believers among the Karen. Why, then, did the authors of Buddhist Karen histories intentionally disregard the Christian Karen and try to contain their ethnic world within Buddhism? Put it another way, why did the religious fellowship with the Burman and Mon have priority over ethnic brotherhood with the Christian Karen?

The second point concerns the relationship between kingship and ethnicity. U Pyinnya’s work is full of descriptions regarding the four royal lineages of the Kayin and their branches. Yet the heroes are not individual kings but the Kayin lumyo itself. U Pyinnya confidently proclaims, “How on earth has the Kayin lumyo been able to survive without its own kings?” and U Saw persistently repeats, “the flow of a river may become choked with sand, but the flow of a people (lumyôu luyôu) can never be dammed.” These are ethnic historical accounts in which the ethnic people themselves are the protagonists. The concept of kingship functions only to sustain the Kayin/Kuyin as a legitimate lumyo, which therefore guarantees them a place as a sovereign being in their worlds.

If this is so, further questions are raised with regard to their styles of narrative. Saw Aung Hla calls his book simply “a history book (li tacisoteso)” while U Pyinnya and U Saw added “chronicle” (yazawin) to their titles. As we have seen above, yazawin is a style of historical account that commemorates the achievements of kings in order to legitimize their rules. How, then, should we understand the gap between the declared yazawin style and the actual lumyo-centered contents? After the British colonization and complete destruction of the Burmese dynasty, why did the authors still choose to employ the yazawin style? And why did they write their Karen histories in Burmese?

The last point concerns the relation between kingship and religion. This is the linkage that both authors appear to be least concerned about. U Pyinnya argues the seven ranks of the kings, with Sekkya min, who embodies the rule of Dhamma (truth or law of the universe), as the supreme rank (Section 58). This is only mentioned, however, because he believes that the founders of both the Pa’awana and Zweya dynasties do not fit any of these seven categories, but should be categorized as shin-bayin, a higher type of king than any of those seven. Although U Saw writes about “boudha badha minnwe (the Buddhist kings’ lineage),” this expression makes sense only when the Kuyin are made the subject of the sentences. In the end, neither book talks much about the kingship-religion linkage.

So how is it possible for a yazawin history not to touch upon the connection between min and thathana? Ideally the min was supposed to be the guardian of the Sangha, in which thathana was the principal order of the world. In turn the Sangha granted the title of dhamma raja, King of the Dhamma, to the ruler. This is a well-known relationship in Theravada societies (Ishii 2003a [1975]; Okudaira 1994, 97), but U Pyinnya and U Saw’s books appear not to be concerned with this.

All the concepts and ideas examined so far have their basis in the actual history of the Burmese-speaking world. For example, thathana and badha indicate religion; min, minzet minnwe, and nan’yo indicate kingship; pon pyinnya, parami, and tanbara indicate virtues of kings; and lumyo is the unit of man, along with Kayin, Myanmar, Mon, Shan, and others.

VI Conclusion

We have examined the backgrounds of two Buddhist authors of Karen history books, their assertions, and their logic. What they tried to convey through their publications was that the Kayin/Kuyin were a fully qualified and legitimate lumyo in the Burmese Buddhist world. This was justified by their claim that the Kayin/Kuyin had devoted Buddhist kings from the outset, as did other lumyo such as the Burman and Mon. Burmese readers of Kayin/Kuyin history would be persuaded by this reasoning as it is structured using lumyo-min-thathana elements. This in turn raised other questions regarding the authors’ neglect of the Christian Karen, the gap between their style and content, and their indifference to the traditional relationship between kingship and religion.

The next task then is to place these two texts in the historical context of the Burmese-speaking world, particularly from the Kongbaung to the early colonial period (from the middle of the eighteenth century to the early twentieth century), and study how the fundamental concepts of lumyo, min, and thathana were nourished in the actual historical development. Then the microscopic social context, where the historical context and the texts meet, should be closely examined. It is in this context that the authors were actually motivated to write and publish their texts. This will provide us with a vivid and concrete picture of how the Buddhist Karen-speaking population felt that they were in fact Karen.

At the turn of twentieth century, a major change took place in the Burmese-speaking world, what can be described as an “ethnocization” of Burmese society, due largely to the extinction of Burmese (or Burman) kingship and a crisis of thathana. This transformation is observable in the alteration of idiom employed in the multiple waves of peasant uprisings from the end of the nineteenth century to the third decade of the twentieth century (Ito 1994; 2003; Ino 1998). At first, the peasant uprisings were aimed at the restoration of the rule of the min and its strong ties with thathana, but in the 1930s these uprisings transformed into movements for Burman lumyo by Burman lumyo with obvious “Myanmar” representations. As a result of this process, at the beginning of the twentieth century, lumyo became the basic unit of social composition and political organization, a fundamental measurement of thought and historical understanding, and an element deemed sovereign and indispensable in Burma. The age-old concepts of min and thathana saw their functions change when lumyo became more central and important to the people. Therefore, it was crucial for both U Pyinnya and U Saw to define the Kayin/Kuyin within the structure of this lumyo=thathana=min scheme. The next question is why they needed to emphasize Kayin/Kuyin sentiments at this particular point of time.

This was due to the social context of colonial Burma in the 1920s. In his final chapter, U Pyinnya brings up an incident involving a controversial movie and an angry exchange of letters in the Burmese newspaper of the day. A reader of the newspaper had written in to complain about a recent movie that treated the Kayin as a savage lumyo. This dispute lasted for half a year with 35 or so letters by Karen and Burman readers being published. Analysis of the letters shows us how the Karen were perceived as a lumyo in Burma at that time and how the Buddhist Karen, as a lumyo, began to react against Burman criticism.

A study of the contexts in which the Buddhist versions of Karen history were written allows us to grasp the earliest stage of Karen identity formation among the Buddhist section of the people. This will inevitably urge us to modify the widespread image of the Karen in general, direct our attention towards the historiographical background behind the focus on Christian Karen, and in long run, lead us to consider the process of ethnocization of Burmese society. Changes in the concepts of lumyo thathana, and min of the Burmese-speaking world cannot, of course, be observed through the Baptist missionary reports and the British administrative documents. Not only Karen, but also the earlier stage of Burman nationalism, should be reexamined in this light.

1) Burmese terms are transliterated according to the system in The Burma Research Group (The Burma Research Group 1987, 18) for the first appearance of each term, but will be mentioned in simplified form in italics without tonal symbols thereafter. For Sgaw Karen, the transliteration system by Yabu (Yabu 2011b, 526–531) will be used.

2) There are several versions of this legend, but its basic outline is as follows: When Ywa, the legendary god of the Karen, left them, he gave them a golden book, but it was lost. It is said that a “white brother” will come back with this book. In the early missionary work, missionaries were regarded as the “white brother” and the Bible or prayer books as “the lost book.”

3) Pwo has eastern and western dialects. The differences between these dialects are so great that speakers from different groups are unable to communicate with each other when they first meet.

4) Burmese- and Karen-language publications on the Karen, including Buddhism, are well represented in diploma theses such as Nilar Tin (1991) and Aung Thein (1999).

5) U Obatha acknowledges U Pyinnya as co-writer and his book has a totally different concluding remark, which corresponds exactly to two pages of U Pyinnya’s original work. Apparently, the original text U Obatha based his work on lacked the final sheet containing the last two pages and he therefore invented a different ending.

6) Slapatthutalinga by U Parama (1942) was the only peza (palm leaf manuscript) categorized in the history section by Hpone Myint (Hpone Myint 1975). It was published as a printed book in 1957 and reprinted in 2003, but it seems not to contain any historical accounts of the Karen.

7) Leke and Telakon have been active in the same region of activity as “Karen Buddhism.” The complexity of religious affairs in the Paan plain since the nineteenth century requires further study.

8) From a linguistic point of view, the Pwo Karen monastic script is strongly influenced by the Mon script, and is thought “to have been invented by the Mon monk who used to preach to eastern Pwo speakers, or by the eastern Pwo monk who studied the Mon language” (Yabu 2001a, 253). The Karen have other major scripts such as the Sgaw Karen mission script by J. Wade, the Pwo Karen mission script also by J. Wade, and the Sgaw Karen monastic script.

9) U Pyinnya states that in 1908 he went to Myohaung to visit a residing monk of Shan ethnicity, who was his childhood friend.

10) Bibliographical details are not known.

11) No bibliographical information is available as this document is thought to have been “lost” since U Pyinnya’s time.

12) The Maingkhaing brand of paper of the Shan State seems to have already been established by the 1920s. Paper was preferred to palm leaves in the Shan States in the nineteenth century (Iijima 2004, 119–120; 2007, 96).

13) References to these “Greek and Italian classics” cannot, however, be found in U Saw’s text.

14) There is some confusion in the numbering of the chapters and sections. U Pyinnya’s book has in fact 70 sections.

15) Though it has gone out of fashion, the Sgaw are still sometimes called Myanmar (Bama) Kayin, and the Pwo, Mon (Talaing) Kayin in colloquial Burmese. However, the Karenni or Kayah, who have intimate historical relations with the Shans, are never referred to as Shan Kayin.

16) Karan and Kayin: the “r” and “y” sounds are interchangeable in Burmese.

17) Yodaya means Thailand or the Thai people in modern Burmese. Yodaya is not considered to be ancient, as described here, in the general understanding of Thai history.

18) A myo was originally a fortified town or city, or simply a city or a town.

19) However, Kuyin (![]() ) is thought to have been pronounced Kayin (

) is thought to have been pronounced Kayin (![]() ). It would remind any Burmese speaker of the word “kùla” (

). It would remind any Burmese speaker of the word “kùla” (![]() ), meaning Indian or foreigner. It is also pronounced kala despite its spelling with a “u” sound. This hints at why U Saw persisted in this spelling: he put much emphasis on representations of India, being the cradle of Buddhism and all the lumyos of Myanmar. This therefore serves as a device to link the Karen with an authoritative representation of India.

), meaning Indian or foreigner. It is also pronounced kala despite its spelling with a “u” sound. This hints at why U Saw persisted in this spelling: he put much emphasis on representations of India, being the cradle of Buddhism and all the lumyos of Myanmar. This therefore serves as a device to link the Karen with an authoritative representation of India.

20) The other reference to Christianity occurs when U Pyinnya explains ywun, the olden name of the Thai people who lived in the eastern region of the Mon Kayin area, previously called gyun. He uses the English word “JESUS CHRIST” as an example: “It is transliterated as ye su’-khari’ in Burmese”; The “y” sound in ye su’ is interchangeable with the “j” (gy) sound in JESUS (Pyinnya 1929, 30).

21) Alawaka is rāksasa or a devil conquered by Buddha.

22) It is likely that before the eighteenth century, the term batha in Burmese did not carry the meaning of “religion.” Batha derives from the Pali word bhāsā, which means “speech, language” (Childers 1909, 83). All other words derived from this Pali word such as phaasăa in Thai, bahasa in Malay, and basha in Nepali are not associated with “religion.” Also, when appearing in chronicles, scriptures, royal orders, and announcements of an official character, the term usually does not signify Buddhism. When Buddhism is referred to from an internal perspective, the term used is always thathana, not batha. The association of “religion” with the term batha seems to have materialized at the end of eighteenth century or at the beginning of the nineteenth century.

23) U Saw never comes back to Christianity after putting it aside “for the time being.”

24) U Pyinnya also mentions this in his book (Pyinnya 1929, 92).