Merchants of Madness: The Methamphetamine Explosion in the Golden Triangle

Bertil Lintner and Michael Black

Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, 2009, xii+180p.

In recent years, amphetamine type substances (ATS) have become the most widely used illegal narcotic drugs in Mainland Southeast Asia. These substances contain the medicinal alkaloid ephedrine which is amply found in Asiatic species of the Ephedra Family. Ephedra is known in Chinese as ma huang (麻黄), “Yellow Cannabis.” The plants themselves are mostly deciduous shrubs growing in arid areas in the middle and north of China and points westward.

As Bertil Lintner and Michael Black show clearly in Merchants of Madness, production and use of ATS in the region has exploded in recent years, far surpassing the total number of opiate users. Because ATS in this region is essentially a local phenomena with little exported to Europe or North America, much less is known about it outside Southeast Asia.

However, within Thailand and Burma as well as its neighbors, ATS has become a serious problem. As long ago as 1996, UNDCP officials (the United Nations International Drug Control Programme, forerunner of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, UNODC) were becoming aware that ATS production in the region was accelerating even as opium poppy cultivation and use was stagnating if not actually declining. In its 2010 Situation Assessment on Amphetamine-Type Stimulants (UNODC Global SMART Programme 2010), UNODC noted that 50–80 percent of the world’s ATS users are in East and Southeast Asia, that almost 100 million tablets were seized in 2009, and that production is increasing mostly in border areas in North and East Shan State.

As with opium, ephedrine has both positive and negative properties. It stimulates the brain, increases the heart rate, and expands the bronchial tubes. It also increases the metabolism. Ephedrine has long been used in China to treat asthma and other ailments. In the United States ephedrine is the active ingredient in pharmaceutical preparations such as Benzedrine which was an inhalant for the treatment of asthma. However, when it was learned that ephedrine had a euphoric effect, people began removing the paper strip inside the inhaler and swallowed it. “Bennies” grew so popular that Ian Fleming had 007 using them in three of his novels. There are websites that claim that ephedra “is a plant with a PR problem,” has a reputation as a “troublesome” herb, and can contribute to weight loss and other benefits (i.e. http://www.diagnose-me.com/treat/T327930.html).

The Asiatic ephedra plants are not native to the countries of Southeast Asia but to Mongolia and the north of China, where the substance was formerly known as ma huang. In Thailand it was called ya ma. Probably ma originally was derived from the Chinese ma huang but when used in Thai it came to be pronounced with the same tone as ma, meaning horse. As Lintner and Black well explain, this horse medicine became widely known after World War II among long distance truckers as useful for staying awake on long drives with an estimated 300,000 users in Thailand.

As for negative side-effects, Lintner and Black, as well as the Thai Government, UNODC, and other involved agencies point out that the drug can cause aggressive behavior leading to murder, kidnappings, and other violent crime. Unlike opiates which generally sedate the user, ATS can lead to conflicts and much harm to innocent bystanders.

Ya ma remained something of a niche drug for decades until the 1990s when groups in the northeast of Burma, such as the United Wa State Army and other breakaway groups from the Communist Party of Burma, began producing large quantities of ATS.

It was at this time, and through a marketing process not fully understood (but discussed in depth by Chouvy and Meissonnier [2004, 81–103]), ATS use spread rapidly and particularly among school children—mostly boys in their second year of secondary school (grade 8 in the 12 year Thai pre-university educational system). At that time, teachers throughout the country remember seeing pieces of foil from cigarette packs scattered around the more remote areas of secondary school campuses as the sign of a problem they did not understand. The students were “smoking the dragon” with ATS pills, that is grinding the pills up and burning the powder on the foils which they then inhaled.

Subsequent studies revealed that these young students, beginning to grow confident in secondary school and as very young adults associated ya ma with having more fun in group activities. The very name, ya ma (horse medicine) which associated the pills with strength and medicine, made them all the more appealing. By 1996, the number of users had increased to over one million (Chayan 1996, 102) and had become the most abused substance in the country.

In that year, the Thai Government decided to change the name from ya ma to ya ba, i.e. crazy or madness medicine in order to reduce the allure of the name to would-be users. From then on the Thai Government would carry out a heightened campaign against the production, trafficking, and use of ATS that peaked in Prime Minister Thaksin’s War on Drugs in 2003. Although that lapsed and he is no longer in power, the country has continued efforts to reduce the use of the drug that is now by far the most widely used narcotic substance in the country.

Lintner and Black focus attention on the merchants who sell the drug, especially at the beginning of the marketing chain. Their study starts with the 1989 mutiny by which three groups in northeastern Shan State, broke with the Communist Party of Burma to take control of their respective regions. The first is Kokang, whose rulers are descended from refugees loyal to the Ming Dynasty in China in the 1600s. Besides Kokangese, there are also Palaung and other groups. Second are the Wa, actually, a diverse group of peoples speaking sometimes mutually unintelligible dialects. They were united politically during the CPB era during which time the area under Wa authority expanded southwards from Pang Kham1) to Mong Pawk, Hotao, and Mong Phen where the people are mostly Lahu and Akha. The third group is based in Mong La and comprises three main groups, Tai Lu (often locally called Shan), Akha, and Tai Loi, a Mon-Khmer speaking group also known as Bulang. Following the collapse of the CPB, these three areas were given autonomy (in the case of the Wa, considerable) over their areas, known to the government as Kokang Special Region 1, Wa Special Region 2, and Special Region 4 (based in Mong La).

On page 66, there are photos of 16 individuals identified as the main “players.” Almost all of them are connected with the Wa Region either as leaders, such as Bao Youxiang, or as financiers, such as Wei Xuegang. The remainder are Chinese or Shan associated with Shan rebel groups, such as Yawt Serk.

Lintner and Black devote most of the book to the background of these individuals and their organizations who they indicate are those most responsible for the recent spread of ATS. They explain how ATS production came to be prominent and how use spread to Thailand. They do not discuss the merchants on the Thai side except for a few who were arrested. They add that the Thai police know who they are but are constrained from taking action due to corruption and protection afforded the big bosses. They paint a picture of organized crime, human rights abuse, smuggling, and money laundering.

They describe the financial empires created by the ATS merchants such as in a massive casino complex being built at the Boten border crossing between Luang Namtha in Laos and Mong La across the border in Yunnan. They detail how the Hong Pang Company, a conglomerate involved in gems and jewelry, construction, and agriculture grew. The authors contend that these and other concerns have grown immensely wealthy from ATS production and sales that they are growing indiscriminately in wealth and influence.

The authors blame the confused politics and ethnic conflicts in Burma for the explosion of ATS production. They chide “global hypocrisy” by which the “West likes to posture itself as a champion in the ‘war on drugs’” but in fact is implicated for having pushed opium into China and elsewhere in the nineteenth century. There are “no angels or devils in the Golden Triangle; they are often one and the same” (pp. 143–144).

However, demonizing the Wa they say is counterproductive because it will not lead to any solution of the amphetamine trade (p. 144). “Engaging them may be the only way forward.” They lament that “the world insisted on working only through the UN and ‘recognized governments’” (p. 144) rather than taking the opportunity of acting on a proposal by a Wa leader named Saw Lu. He had written an open letter entitled “The Bondage of Opium: The Agony of the Wa People, a Proposal and a Plea” stating that the Wa wanted to end opium poppy cultivation in exchange for certain political concessions including a “separate state for the Was within a federal union” (p. 108). However, no action was taken according to the authors because “The DEA and the UN’s various agencies said they were not able to provide any direct assistance to the Was” and that aid would have to go through “the Burmese government” (p. 110).

While we can be sure that Saw Lu told this to one of the authors (p. 171), this was not the end of the story to UN providing development assistance to the Wa. Two years earlier, UNDCP Executive Director, Giorgio Giacomelli had finalized a drug control MOU between the six Mekong countries. By late-1992, all six, including Myanmar, had signed an action plan that included law enforcement, demand reduction, and alternative development projects. This plan was based both the region’s needs as well as the funding realities of UNDCP which require it to depend on contributions for many activities from countries such as in Europe, Scandinavia, Australasia, and North America. Since none were willing to fund law enforcement work in Myanmar (although some regional projects were supported in which Myanmar participated), work in Myanmar was in alternative development and drug treatment. When Giacomelli went to Myanmar in May 1993, he visited Lashio, Kengtung, and Tachilek in Shan State where he discussed the small development projects that were soon started in Hopong, a government-controlled area with many Wa, Nam Tit which was in the Wa Region, and Silu District of Special Region 4.

It is likely that the government of Myanmar had already decided on this course of action prior to Saw Lu’s discussion with one of the authors. How much the Wa were involved is unclear but they were in agreement with the basic idea of the UNDCP project early on. In 2006, while managing the UNODC Wa Project, I was told by a former UNDCP representative to Myanmar, that Wa leaders in about 1993 had asked UNDCP staff in Silu for help with their plan to stop growing poppy which they had included in their first five-year development plan in 1990. They (who were in agreement with Saw Lu on the advisability of banning opium) told UNDCP that their effort to eliminate opium comprised three five-year development plans, culminating in a ban in 2005.

UNDCP referred the matter in 1993 to the government which initially objected to the idea. But after negotiations, Hotao was decided on by all as the best site because of its proximity to Silu and also Mong Yang which was under government control and it had road access both to Kengtung and an all-weather road to the China border seven miles to the east.

This led to the formulation of the UNDCP/UNODC Wa Project, that ran from 1998 to 2008 and was designed to provide assistance, through community development, agricultural extension, and drug treatment, to poppy farmers so as to ease their transition to new livelihoods following the opium ban in 2005. The Wa, who had not fully been involved in the formulation process, however, were expecting grants of funds by which they could develop the region, beginning with infrastructure, in its own way. After several years of negotiations, some run-ins, and trials and errors on all sides, a methodology acceptable to the Wa, the Government, and UNODC was reached.

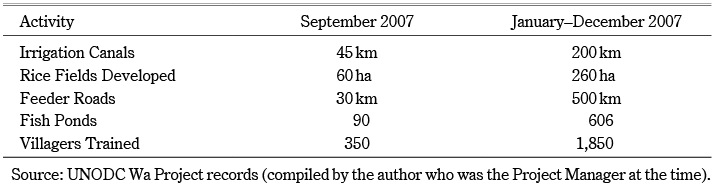

This entailed providing high yield open pollinated rice to poppy growers, small-scale irrigation projects to provide water for newly-developed or expanded paddy fields, drug treatment, vocational training (i.e. carpentry, tailoring, livestock raising), and small infrastructure development such as for feeder roads. The aim was to enable the farmers to grow more (if not always enough) rice on lowland fields which (in the absence of secure land title deeds) was the most certain way the farmers could hold their land and protect it from sometimes avaricious Wa officials who otherwise would appropriate the land to grow rubber or tea. By the end of 2007, the project had grown quite effective in providing this assistance, as shown in Table 1.

By this time the approach the project had taken had encouraged many other organizations to participate, all with the approval of the Wa Authority (and the Government). These included UN agencies such as the World Food Programme, FAO, UNDP, UNICEF, and UNFPA, as well as international NGOs including Malteser International, Aid Médicale Internationale, CARE, and German Agro-Action. They followed the approach pioneered by UNODC as well as helping to control malaria, address the small but growing incidence of HIV in the Wa towns, and providing support to the educational system (with Chinese and Myanmar curricula).

By this time, though, the war on drugs had caught up with the Wa and the UNODC Wa Project. In January 2005, a Federal Court in New York handed down indictments on eight Wa leaders for trading heroin and methamphetamines. As Lintner and Black note (p. 91), this led to the temporary removal of the staff (actually only the international staff) from the Wa Region. But what they do not mention is that the U.S. Embassy in Rangoon concluded that death threats had been made against the three DEA agents in the country. This led directly to the United States cancelling its funding of the Wa Project (approximately three-quarters of the total at that time).2) Although funding from Australia was received to extend the life of the project for another year (until 2007), the project was obliged to cease operations before all the people who could benefit from UNODC inputs could be reached. Nonetheless, many other agencies had their own funding and alternative development went on although drug treatment was reduced.

None of this later information is in Merchants of Madness. Lintner and Black disparage UN leaders as misinformed (pp. 101–102), make a very brief reference to the UN as envisioning the problem as “agricultural” (p. 111), and refer to the “December 2005 Myanmar Country Profile.” However, there are no references in the “Notes on Sources” to any interviews of any UN official (UNODC or otherwise) or to any UNDCP or UNODC project reports or documents and nothing on UNODC after 2005.

This is significant because the activities carried out in the Wa Region provide an alternative approach to dealing with Myanmar than what Lintner and Black propose. They suggest that, quoting an address by Aung San Suu Kyi in 1989, a “lasting solution to the problems of the ethnic minorities [including drug production] . . . [is] to secure the highest degree of autonomy [for those minorities] ”(p. 146).

While one cannot dispute this, it is also indisputable that minority groups have faced serious problems since the 1960s. Many international agencies, including INGOs, believe that no action can be taken for the overall good before any resolution to the problems are forthcoming. But if they were asked, the Wa villagers who are growing more rice, have water supplies in the village, and who have stopped using opium would agree that the interventions were useful regardless of continued ATS production.

Though not mentioned by the authors UNODC’s work in the Wa Region achieved the following results: 1) Preventing a humanitarian crisis after the ban; 2) Providing support for the peace process; and 3) Setting an example for working in other ceasefire areas. This has been the longest and biggest such internationally-supported project in Myanmar since independence in 1948. No other such project has involved so many partners and so many beneficiaries. Nor has there ever been any project of this scale and scope in a ceasefire area. The approach pioneered here can be productively utilized in other such areas in Myanmar. Technically the book is sound in terms of formatting and proofreading except for the index which has some errors. Despite their misunderstanding of UNODC’s work in the Wa Region, the authors make a useful contribution by describing the seriousness of the ATS problem in Thailand and in neighboring areas.

Ronald D. Renard

Chiang Mai University

References

Chayan Vaddhanaputi. 1996. Thailand Country Analysis. Report in the final report of the consultancy to develop a subregional project improving institutional capacity for drug demand reduction among high risk groups, submitted to UNDCP, Bangkok.

Chouvy, Pierre-Arnaud; and Meissonnier, Joël. 2004. Yaa Baa: Production, Traffic and Consumption of Methamphetamine in Mainland Southeast Asia. Singapore: National University of Singapore.

Diagnose.me.com. Ephedra (Ma Huang). http://www.diagnose-me.com/treat/T327930.html Accessed February 3, 2013.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) Global SMART Programme. 2010. Myanmar Situation Assessment on Amphetamine-Type Stimulants. UNODC Global SMART Programme.

United States Department of State Bureau for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs. Memorandum of Justification for Presidential Determination on Major Drug Transit or Illicit Drug Producing Countries for FY 2008. International Narcotics Control Strategy Report, Vol. 1, pp. 278–285. Excerpted and posted at http://www.docstoc.com/docs/80441611/UnitedStatesDepartmentofStateBureauforInternational. Accessed February 3, 2013.

1) Lintner and Black refer to this city as Panghsang, but the Wa no longer use this term which they claim is inauspicious.

2) See “Memorandum of Justification for Presidential Determination on Major Drug Transit or Illicit Drug Producing Countries for FY 2008,” affirming this action (which was not communicated to UNODC in Myanmar) at the time

(http://www.docstoc.com/docs/80441611/UnitedStatesDepartment

ofStateBureauforInternational).

DOI: doi.org/10.20495/seas.2.1_Body1