Trade Union Organizing Free from Employers’ Interference: Evidence from Vietnam

Trinh Ly Khanh*

* Trịnh Khánh Ly, Department of Criminology, Criminal Law and Social Law, Ghent University, 4 9000 Gent, Belgium

e-mail: lykhanh.trinh[at]ugent.be

DOI: doi.org/10.20495/seas.3.3_589

In recent years, Vietnamese trade unions have made considerable strides in trade union organizing. However, studies show that workplace trade unions are generally dominated and controlled by employers. Increasing labor unrest, particularly in the private sector, reveals the failure of trade union organizing and operation in Vietnam. This article aims to provide a picture of trade union organizing as conducted by the communist Vietnamese trade union system in the private sector, particularly trade union organizing that is free from employers’ interference. It also examines whether the new legal framework may contribute to this form of trade union organizing in the near future.

Keywords: Party-led trade unions, trade union organizing, employers’ interference, anti-unionism, Vietnam

Introduction

The reforms (doi moi) initiated in 1986 by the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) to transform a centrally planned economy to a socialist market economy has created significant changes in the Vietnamese labor market. Before the innovation most people of working age were employed in state agencies or state-owned enterprises. Today, the majority of the employed population works for the private sector (approximately 41 million persons are employed in local enterprises and approximately 1.6 million persons are employed in foreign-invested enterprises) (Vietnam, General Statistics Office [GSO] 2010). Vietnam still has a socialist political system and trade union policy: the Vietnam General Confederation of Labour (VGCL) is the only trade union. Workplace trade unions (công đoàn cơ sở), immediate upper-level trade unions (công đoàn cấp trên trực tiếp cơ sở), and other trade unions of different levels must follow the Statute of VGCL. Workers from different sectors have the right to voluntarily form, join, or participate in trade unions in accordance with the law. The trade unions are open to Vietnamese salaried workers and self-employed Vietnamese,1) irrespective of their occupation, gender, or religious belief. However, they are only entitled to form, join, or participate in trade unions affiliated with the VGCL2) since independent trade unions operating outside the umbrella of the VGCL are not legally recognized.3) The change in labor structure has led to a shift in the VGCL’s focus regarding union organizing in the private sector, dominated (97 percent) by small and medium enterprises (Tự Cường 2012). In 2003, the VGCL set a target to gain 1 million new trade union members in the period 2003–08 and 1.5 million new trade union members in the period 2008–13. Accordingly, by the end of 2013, workplace trade unions should be established in 70 percent of the eligible enterprises under the provisions of the VGCL Statute, gathering at least 60 percent of the workers (Nguyễn Duy Vũ 2012). By the end of 2011, the number of new trade union members had increased by over 1.3 million. This brought the total number of trade union members in the whole country to over 7.5 million, scattered over 111,319 workplace trade unions, of which the private sector accounts for 74.2 percent (ibid.).

Despite the sharp rise in trade union memberships and trade union organizing, there has been a constant increase in wildcat strikes4) since the enforcement of the first Labour Code of 1994, which came into effect on January 1, 1995.5) According to VGCL’s statistics, in the period 1995–2010, there were 3,402 wildcat strikes (Vietnam, VGCL 2011b, 32). The global economic recession led to thousands of workers losing their jobs in 2011. The number of wildcat strikes that year (978 cases) was double that of 2010, concentrated in foreign-invested enterprises in the key economic provinces and cities in the south (Quang Chính and Việt Lâm 2012). The percentage of wildcat strikes occurring in organized enterprises is high, for example, 70.99 percent in 2010 (ibid., 36). Current practices of trade union organizing is one of the major causes of wildcat strikes. Despite the increase of workplace trade unions over the years, several established workplace trade unions are in fact “yellow unions,” formed and influenced by the management of the enterprises in order to serve the employers’ interests (see the following sections for more details). In the face of increasing wildcat strikes, the VGCL has attempted to conduct trade union organizing free from employers’ interference in the private sector. This effort, which is seen as a pilot initiative, has been carried out in a small number of targeted private-sector enterprises in Hai Phong city, Binh Duong province and Ho Chi Minh City since 2011.6) These are representative localities in terms of a high concentration of private-sector enterprises, a large workforce, and a high percentage of wildcat strikes. The aim of this effort is to establish trade unions with democratic participation of workers, based on a bottom-up principle of organizing and minimal influence of employers in the process.

On the one hand, from a structural perspective, the VGCL faces the challenge of reforming its organizational structure in order to gain greater operating independence and better adapt to the global situation of trade unions and the trade union movement. During the revision process of the Trade Union Law of 1990, initiated since 2009, it was proposed that the Communist Party’s leadership in the trade union movement be removed, as clearly mentioned in draft 10 of the proposal of April 30, 2012. However, Article 1 of the current Trade Union Law of 2012 reaffirms the leadership of the Communist Party over Vietnamese trade unions. On the other hand, Vietnamese trade unions have gained more benefits from the Trade Union Law of 2012, for example: legal protection for trade union officers; intervention of immediate upper-level trade unions in non-unionized enterprises; increase of trade union contributions from employers, etc. (see infra).

This article explores how the VGCL conducts trade union organizing in the contemporary Vietnamese industrial context. It explains how employers are able to influence trade union organizing and operations at the workplace level, and outlines the organizational challenges faced by trade unions in implementing reform. Using the example of a few cases where trade union organizing is free from employers’ interference, the difficulties of operating such trade unions is discussed. The article also reflects the changes and potential impact of the new Labour Code of 2012 and the Trade Union Law of 2012 on trade union organizing.

This article is derived from the personal observations of the author garnered after years of involvement in the operation of the VGCL and its initiatives in independent trade union organizing, as well as participation in different seminars and group discussions among trade unions of different levels and other stakeholders such as the Ministry of Labour, Invalids and Social Affairs (MOLISA), the Vietnam Chamber of Commerce and Industry (VCCI), etc. The article also draws on documentation on relevant policies and legal acts.

Current Trade Union Organizing Practices

Traditional Practices of Trade Union Organizing

It is immediate upper-level trade unions instead of rank-and-file workers that take the initiative in establishing workplace trade unions. According to a survey conducted by the VGCL, more than 99 percent of workplace trade unions are established by upper-level trade unions (Vietnam, VGCL and International Labour Organization [ILO] Industrial Relations Project 2012, 16). This usually takes one to three months (45.5 percent) or three to six months (32.7 percent) (ibid., 13).

The immediate upper-level trade union first conducts surveys on the situation of enterprises and workers in the target areas in order to identify enterprises suitable for union organizing. These surveys are conducted in coordination with the relevant authorities: planning and investment departments, labor departments, invalids and social affairs departments, tax departments, management committees of industrial zones, etc. (ibid., 25). As soon as the surveys are completed, the immediate upper-level trade union contacts the employers in writing to propose a meeting. If the enterprises do not respond, the union sends another letter or tries to make direct contact (ibid.). If the union’s proposal is not accepted by the employers, trade union officers cannot access the enterprises and workers cannot leave the production site to meet them (Nguyễn Ngọc Trung 2012). If the enterprises agree with the proposal, an official response is sent and a meeting is arranged at the companies’ premises (ibid., 16).

During the meeting, trade union officers meet the workers and expound the necessity and benefits of joining trade unions. They instruct the workers on how to apply for membership and nominate members of the temporary executive committees of the workplace trade unions after discussion with the enterprise’s directors. Next the enterprise management, together with the upper-level trade union and the temporary executive committee, prepares and organizes a ceremony for member admission and creation of the trade union (ibid., 25–26). The decision on forming a workplace trade union and the nomination of its temporary executive committee, issued by the upper-level trade union, is based on the employer’s recommendation (Nguyễn Văn Bình 2011, 13).

How Employers Interfere in Trade Union Organizing

As analyzed above, upper-level trade unions are too dependent on the goodwill of employers in the organization of workplace trade unions. If employers deny the upper-level trade unions access to their premises to conduct a campaign for their workers, the trade union organizing is considered a failure. Moreover, there has been a misinterpretation for many years now of the VGCL’s procedure concerning the application dossiers for starting workplace trade unions. The VGCL does not require the employers’ signature in the application dossier submitted to the immediate upper-level trade unions. In practice, however, the unions often request the enterprises and workers to provide the employer’s signature in the application letter, which includes the recommended list of the temporary executive committees of the workplace trade unions.7) This signature is taken as proof of the employers’ commitment to create favorable conditions for the operation of trade unions in their enterprises (Nguyễn Văn Bình 2011, 15).

Trade union activity is still heavily influenced by the centrally planned economy period where there was no conflict of interests between the employers and workers in state-owned enterprises. The VGCL does not prohibit the management of a company from joining its trade union or from holding leadership positions in the union, for example, as president or members of the executive committee. The VGCL has taken measures to correct this anomaly. On May 6, 2009, the Presidium of VGCL promulgated Guidance No. 703/HD-TLD, Item 1.2, Chapter I, banning the owner(s), president, and/or deputy president of the governing board; general director and/or deputy general director; directors and/or deputy directors of a private-sector enterprise from joining its trade union. However, this ban does not apply to other persons from the management, notably, heads and/or deputy heads of functional departments and production workshops, etc. Indeed, a survey shows that 60–70 percent of workplace trade union presidents hold managerial positions within the company (ibid.).

Members of the management who became trade union members before the promulgation of Guidance No. 703/HD-TLD automatically lose their trade union membership status, but the VGCL has no regulation preventing them from becoming honorary trade union members and participating in trade union activities.8) Consequently, this allows employers to continue participating in trade union activities and monitoring and influencing its operation. Moreover, employers are statutorily required to make a financial contribution to the trade union on a monthly basis. This requirement was equal to 2 percent of the workers’ salary fund, which is used as the basis for social insurance contribution, and was applied in both state-owned and in private-sector enterprises. In foreign-invested enterprises, this amount was equivalent to 1 percent of the total wage budget.9) Since January 1, 2013 this amount has been amended to 2 percent of the total workers’ salary fund for all organizations and enterprises of both the public and private sector.10) This legal provision formally creates room for the employers to dominate and control workplace trade unions, which is inconsistent with Article 2 of the ILO Convention No. 98, to which Vietnam is not a signatory.

Before the formulation of the Labour Code of 2012 and the Trade Union Law of 2012, the Vietnamese government carried out a study on the compatibility of Vietnamese laws with Convention No. 98 on the Right to Organize and Collective Bargaining of the International Labour Organization. The study showed that parts of Vietnamese laws were incompatible with the Convention, particularly provisions on the independence of trade unions (Vietnam, MOLISA 2012, 48). With the promulgation of the Trade Union Law of 2012, which restricts the independence of trade unions, the possibility of joining Convention No. 98 is vague in the near future.

Another reason the trade union system facilitates employers’ interference in trade union organizing arises from the VGCL’s target of developing trade union membership. There have been numerous cases where the principle of voluntary participation of workers has been ignored during the process of workplace trade union establishment, as acknowledged by VGCL (Vietnam, VGCL 2010, 16). Moreover, due to the shortage of upper-level trade union officers with experience in leading the organizing process in private-sector enterprises, the process does not always match the enterprises’ needs, and the methods and contents of the campaigns do not leave the workers convinced.11)

Trade Union Organizing Free from Employers’ Interference

Since 2011 the VGCL has initiated innovative ways of organizing trade unions in the private sector in the localities mentioned above. What is new is that the trade union organizing is conducted by the immediate upper-level trade unions outside the enterprises’ premises and outside working hours. Officers of immediate upper-level trade unions approach workers of targeted enterprises in order to learn about their working conditions (the total number of workers, wages, issues with management, etc.). The officers try at the same time to select focal workers who can influence the other workers to join the trade unions.12) Leaflets about trade unions and the rights and obligations of trade union members are distributed to the workers. Other services such as legal aid, sports and entertainment activities, etc. are organized to improve the relations between immediate upper-level trade unions and the workers (Vietnam, VGCL and ILO Industrial Relations Project 2012, 8).

Once it receives the application letters of at least five workers, the immediate upper-level trade union issues a decision to admit the workers into the trade union. Members of the temporary executive committee for the new trade union are voted in directly by the trade union members and officers help to organize meetings for members on trade union operation. Only after all this has been put in place are the employers informed (ibid., 9, 10).

Trade Union Responses to Employers’ Interference

Case 1: Company K (Vietnam, VGCL and ILO Industrial Relations Project 2012, 21–22)13)

In 2007, Ms L, a staff of the human resources department was elected as the union president. The management asked her not to approach workers at the workplace; instead, they suggested that the workers go and see her at the human resource department if needed. Ms L did not agree and continued meeting workers at their workplace when necessary. In early 2011, as the trade union was preparing for its congress in the new term, the management opposed Ms L’s occupation of the position of trade union president and prepared a list nominating members of the executive committee—excluding Ms L. She was then forced by the management to put the stamp of the executive committee on this document. When the upper-level union learnt about this case, it issued a decision to cancel the congress and reorganize another one.

Case 2: Dong A Vina Company (Đức Minh 2012)14)

Dong A Vina is a 100 percent foreign-invested company in Binh Duong industrial zone, Di An, Binh Duong province, employing 530 workers. Mr Tran Van Sy, head of the production section, was elected as a member of the company trade union’s executive committee at the trade union congress.

After his election, Mr Sy went on leave. When he came back to work, the human resource department launched a procedure to dismiss him on the grounds that he had returned to work a few days late without a valid reason. To protest against this unjust decision, 512 workers of the company went on strike on July 12, 2012, demanding that Mr Sy be reinstated and that the officers of the human resource department responsible for this decision be dismissed instead.

Representatives of the trade union of Binh Duong industrial zones and the management board of Binh Duong industrial zone (the local authority) came to the company to try to resolve the dispute. On July 23–24, 2012, approximately 30 representatives of the workers, including the executive committees of the workplace trade unions and heads of the production groups and production lines, were invited to attend a conciliation meeting with the company management. The company agreed to pay Mr Sy benefits if his dismissal was found to be illegal. The workers’ demands that the staff of the human resources department involved be dismissed and that the strikers be paid 70 percent of their wages for the days they did not work were denied by the company.

At the end of the meeting, the representative of the workplace trade union promised to encourage the workers to come back to work on July 25, 2012. However, the workers refused and stuck by their earlier demands. The company then dismissed all 512 workers on the grounds that they had been absent from work for over five days without valid reasons.

The above examples show a commitment from certain immediate upper-level trade unions to prevent employers’ interference in the organizing of non-“yellow” trade unions in the workplace. It demonstrates that not all workplace trade unions in the private sector are “yellow unions” and that not all upper-level trade unions ignore the problems faced by workplace trade unions. It also shows that effective linkage and communication between the upper-level and workplace trade unions can be effective in limiting employers’ interference.

At the central level, in order to counter anti-unionism by employers, the VGCL has implemented some measures, including the establishment of a fund to support workplace trade union delegates (presidents, deputy presidents, executive committee members) who are victims of anti-union actions by their employers. This applies to delegates who have been illegally dismissed or transferred to a position that does not meet their skill level or one that pays 30 percent less than their current salary. Concretely, this support entails the following:15)

• Financial support, equal to the minimum wage, for two months immediately after the termination of the labor contract.

• Monthly support, equivalent to the minimum wage, for 1.5 months during the period of unemployment, not exceeding 6 months.

• When a labor dispute between a trade union delegate and the enterprise’s management is brought to court, the fund will cover 50–100 percent of the delegate’s court fees, to be determined on a case-by-case basis.

Key Challenges for Trade Union Organizing Free from Employers’ Interference

Challenges within the Trade Union System

The traditional method of union organizing, whereby workplace trade unions are dependent on employers, has been carried out for years. This has become ingrained in upper-level union officers and is hard to change (Vietnam, VGCL and ILO Industrial Relations Project 2012, 33).

In addition, trade union organizing free from employers’ interference requires considerable effort in terms of policy commitment, time, human resources, and finance. The first challenge for upper-level trade unions is the imbalance in staff and workload. As communist trade unions, the VGCL and its affiliated trade unions are tasked with many jobs that are not directly related to the function of trade unions, as compared with conventional trade unions in other countries. These include involvement in politics and the organization of socio-cultural, humanitarian, sports, and recreational activities. Yet they face a shortage of officers, particularly qualified officers, because they do not have a free hand in deciding the number of trade union officers (see infra) .

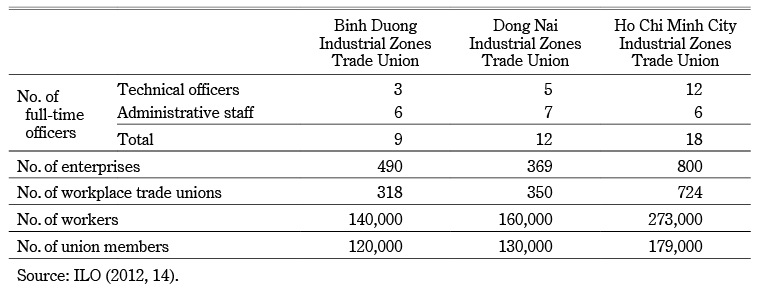

On average, immediate upper-level trade unions comprise two or three full-time trade union officers. Trade unions in industrial zones generally comprise four full-time trade union officers (ibid., 1, 3). The number may increase for some trade unions in the industrial zones of key economic localities. Table 1 shows the number of trade union officers in three economic hubs in South Vietnam: Binh Duong, Dong Nai, and Ho Chi Minh City (ILO 2012, 14).

Table 1 reveals the disproportionate division of work between the technical officers, who are directly responsible for trade union organizing, and the administrative officers. For example, there are 3 technical officers versus 6 administrative staff in the trade union of the industrial zones of Binh Duong; 12 technical officers versus 6 administrative staff for Ho Chi Minh City; and 5 technical officers versus 7 administrative staff for Dong Nai province.

Table 1 also shows the huge workload shouldered by the technical officers, given the big number of enterprises, workplace trade unions, and trade union members under their charge. Furthermore, it also shows up the imbalance in workload among the technical officers of the three localities. In Binh Duong, there are only three officers for 490 enterprises, 318 workplace trade unions, and 120,000 trade union members (this equates to one officer taking charge of 163 enterprises, 106 workplace trade unions, and 40,000 trade union members). Meanwhile, in Ho Chi Minh City, 12 officers are responsible for 800 enterprises, 724 workplace trade unions, and 179,000 trade union members (or one officer for 66 enterprises, 60 workplace trade unions, and 14,916 trade union members). In Dong Nai province, five officers are allocated for 369 enterprises, 350 workplace trade unions, and 130,000 trade union members (that is, one officer for 74 enterprises, 70 workplace trade unions, and 26,000 trade union members).

As mentioned above, the tasks of these trade union officers include many non-traditional activities. This work accounts for 14.18 percent of their workload (Vietnam, VGCL and ILO Industrial Relations Project 2012, 14). This is in addition to participation in political affairs not directly related to trade union activities, for example, with the Party, state authorities (People’s Councils and People’s Committees), Women’s Union, Veterans’ Union, the Ho Chi Minh Communist Youth Union, which account for 14.74 percent of their workload, according to a survey conducted by the VGCL (ibid., 10, 14).

As shown in the case studies above, there is evidence of anti-unionism committed by employers against workplace trade union delegates. However, a survey by the VGCL (ibid., 13) shows that this is not taken into serious consideration by upper-level trade union officers. This exposes the weakness of the trade union system in protecting their union officers. In the case of the Dong A Vina Company above, no systematic measures were put in place by the trade union of Binh Duong industrial zones to protect the workplace trade union officer. The company very clearly interfered in the operations of the trade union by victimizing the trade union officer. Yet his dismissal was not handled any differently than an ordinary case of dismissal and no special measure was taken to counter these acts of discrimination. Moreover, all the workers who went on strike to show their support for Mr Sy and their dissatisfaction with the company were “persuaded” by the company to sign an agreement terminating their contracts. This constituted a major anti-union act targeting the trade union members, yet the trade union of Binh Duong industrial zones did not put up any opposition.

Challenges from the Workers’ Side

Reports show that young workers account for the majority of the private-sector workforce. Most of them are unskilled workers, with unskilled workers who have not received any vocational training accounting for 83.54 percent (Ban Mai 2013). A large number are also migrant workers who work for enterprises in industrial zones and processing zones, for example, 30 percent of the workforce in Ho Chi Minh City, one of the biggest industrial hubs in Vietnam with approximately eight million inhabitants, is made up of migrants from other provinces and cities (Vietnam, Centre for Industrial Relations Development [CIRD] 2012, 3).

A survey by the Binh Duong trade union of 38 enterprises in industrial zones shows that workers’ wages are often too low: 76.8 percent has a monthly income of VND 2,000,000–3,000,000 (equivalent to EUR 66–100 or USD 94–142), which is insufficient for a living; and 76.6 percent of workers has no savings at all (91.7 percent of them cannot afford a house and must rent an apartment). A large number of workers must work overtime16)—up to 50 hours/month (66 percent) or 50–100 hours (31 percent) (Lê Nho Lượng 2011).17)

The situation is similar in Hanoi city. Most workers in the Hanoi industrial zones have to work overtime because of low wages (Phong Cầm 2011). As such, they do not have much time for trade union organizing. Some are also reluctant to join for fear of being discriminated against by their employers. Yet others do not join because they constantly change work in search of higher salaries and better working conditions (ibid., 18).

Challenges from the Employers’ Side

Case 1: Yoneda Vietnam Company (Phong Cầm 2011, 3–6)18)

Yoneda Vietnam is a Japanese company producing stationery products in Hai Phong city. It employs 225 workers. In 2007 an unlawful trade union was formed by the employer in the name of the workers and “trade union dues” were deducted from the workers’ wages. This came to an end in November 2010, after intervention by the trade union of Hai Phong Economic Zones.

The trade union of Hai Phong Economic Zones approached the workers outside the company’s premises, and four core workers’ groups based on common interests were formed: sports, home fellows, age, and living quarters. Trade union activities were gradually introduced to the meetings of these groups.

Currently, some 243–277 workers have applied to join the trade union and 5 workers have been selected for the temporary executive committee. To prepare for the establishment of the grassroots trade union, the trade union of Hai Phong Economic Zones attempted to approach the company director but was turned down. The company director tried instead to divide the workers, instigating them not to join the trade union and putting pressure on influential workers. The contracts of a few of the workers who are members of the core workers’ groups have not been renewed upon expiry.

Case 2: Sonics Company (ibid., 9–10)19)

Sonics International Limited Liability is a Taiwanese company producing bicycle parts in Binh Duong province. It employs 120 workers.

After the launch of a new initiative on trade union organizing, the trade union of Binh Duong industrial zones approached workers outside the company’s premises to obtain more information on the company’s situation. A core workers’ group was then formed, which included three influential workers from the company selected by the trade union. The workers’ group is headed by an officer of the trade union. Members received training on trade union organization, labor law, trade union law, occupational safety, health, etc. This group is responsible for encouraging other workers in the company to join the trade union.

In March 2011, a trade union recruitment ceremony was conducted and 70 workers were recruited. The company director has, however, repeatedly opposed the formation of the trade union. A few months later, in July, the trade union of Binh Duong industrial zones issued a decision declaring the establishment of the trade union of Sonics International Limited Liability. Four members of the formal trade union executive committee were also elected.

The company trade union has been hampered in its operations by the uncooperativeness of the company director, despite numerous meetings arranged by the trade union of Binh Duong industrial zones. On September 15, 2011, the trade union of Binh Duong industrial zones wrote to the management board regarding 11 cases of labor law violations committed by the company and requested an inspection of the company. On October 13 an inspection team led by the management board of the industrial zones made its way to the company. The trade union of Binh Duong industrial zones nominated its officer to join the inspection team. Via this inspection, the trade union of Binh Duong industrial zones formally notified the company of the establishment of the enterprise trade union and asked for its cooperation.

However, until now no effort has been made by the company to comply with labor law. No improvement has been made with regards to the trade union activities. The trade union is facing even greater difficulties in running its activities. Trade union meetings have been forbidden within the company’s premises, including meetings outside working hours. The number of members has been reduced by 42 because some workers have left the company, while others have withdrawn their membership because of the pressure exerted by the company. The executive committee of the trade union has been similarly affected—three members have left, including one who resigned due to the opposition by the company. The executive committee has managed to keep up with its regular meetings; however, other activities, such as recruitment of new members, have been neglected.

Case 3: S. C. Johnson & Son Company (ibid., 7–8)20)

A producer of cosmetics, shower gels, etc., S. C. Johnson & Son Company operates in Song Than I industrial zone, Binh Duong province and currently employs 300 workers. Johnson Mutual Benefit Association (JMBA) was formed by the company to promote the welfare of the workers as well as strengthen industrial relations in the company, in keeping with regulations of S. C. Johnson & Son Corporation. The company has therefore rejected the formation of a company trade union. It has even issued a rule that JMBA will provide monthly financial support for each worker—on the condition that he/she does not join the trade union. Those who wish to join the trade union will lose access to different benefits by the company. As a result, workers in the company do not want to join the trade union. Another obstacle is that the workers are members of other labor-leasing companies. Meanwhile, many of the workers in the company are office workers who live in Ho Chi Minh City and travel to work by company transport. This has made it impossible for the trade union of Binh Duong industrial zones to approach the workers in S. C. Johnson & Son Company.

Case 4: F.C. Company (ibid., 20–21)

Ms TT. Ch. was elected in October 2008 as president of the workplace union in F.C. Company (a foreign-invested company). The company director threatened that she would not receive her monthly responsibility allowance as a production group leader, amounting to VND 150,000 (equivalent to around EUR 5.8/USD 7), unless she resigned from her position as president of the trade union. According to the director, Ms TT. Ch. could not fulfil her production group leader duties if she were to undertake the trade union activities; therefore she was not entitled to her allowance.

Ms Ch. was forced to comply and held her union position from October 2008 to the end of April 2009. During this period, the company management kept an eye on her and threatened her with disciplinary action should she be found lacking in her duties.

In May 2009, Ms Ch. resigned from her union position. Only then was she able to recover her responsibility allowance and only then did the monitoring and threats of sanctioning end.

Case 5: Company F (ibid., 24)

Mr NN. H, who worked as a warehouse assistant, was elected as the president of his company union in March 2007. Mr H organized trade union activities well, winning members’ trust. However, due to active trade union activities, he was discriminated against by the management. In 2009, he lost his position as warehouse assistant and was transferred to a rank-and-file worker position.

The above examples illustrate the general behavior of employers towards independent trade unions. These employers attempt to control the trade unions through ploys such as promising workplace trade union officers financial benefits and promotions; exerting pressure on part-time trade union officers in their normal work; transferring these officers to lower-grade and/or lower-pay positions; excluding trade union members from certain benefits enjoyed by non-unionized workers in the company, etc.

Enactment of the New Legal Framework: Light at the End of the Tunnel?

The fact that no labor case related to the right to organize, join, and participate in trade union activities has ever been settled by the competent courts (Vietnam, VGCL 2011b, 8), speaks volumes of the authorities’ failure to deal with anti-unionism. Moreover, workplace trade unions established and operating outside companies’ premises are not regulated by the Trade Union Statute or any other relevant regulation,21) leading to the denial of their legal status by relevant stakeholders, including the authorities. This issue remains unresolved by the new Trade Union Law of 2012 or the Labour Code of 2012.

As for staffing, there has been no change between the old Trade Union Law and the Trade Union Law of 2012. Full-time trade union officers who work at upper-level trade unions are still public cadres and civil servants.22) The VGCL does not have full autonomy in deciding the number and positions of trade union officers. While it may develop the organizational structure of the trade union and positions within, this is still submitted to the competent authority,23) which has the ultimate say on the positions and workload of full-time trade union officers.24) As a result, the disproportionate distribution of workload among full-time trade union officers in upper-level trade unions remains unresolved.

Nonetheless, there are some positive changes in the new legal framework concerning trade union organizing. In order to prevent anti-union practices among employers, the Trade Union Law of 2012 prohibits the use of economic measures and other methods to interfere in the establishment and operation of trade unions. The Trade Union Law of 2012 also reaffirms the former Trade Union Law of 1990 in prohibiting acts that prevent or cause difficulties to the establishment and operation of trade unions, and which discriminate against or disadvantage workers in the establishing or joining of trade unions or the undertaking of trade union activities.25) The new Decree No. 95/2013/ND-CP imposes stricter sanctions against anti-unionism acts. The fine for employers who prevent or hamper employees from forming or joining trade unions, or carrying out trade union activities, has been increased from VND 10,000,000 to 15,000,000 (EUR 350–524 or USD 473–710).26) A fine of VND 5,000,000–10,000,000 (around EUR 175–349 or USD 237–473) is also imposed on other types of discriminatory acts in the form of working hours, wages, etc.27)

The new legal framework reaffirms the role of immediate upper-level trade unions in trade union organizing,28) but acknowledges for the first time their rights and responsibilities to approach workers in enterprises.29) This legal acknowledgment was necessitated by cases in the past years of employers preventing upper-level trade unions officers from accessing their premises, as we have seen above. Henceforth the act of preventing trade union officers from entering company premises is liable to a fine ranging from VND 5,000,000–10,000,000 (around EUR 175–349 or USD 237–473).30)

There is another encouraging change in the VGCL’s policy, reflecting signs of decentralization in union organizing. In addition to the role of the immediate upper-level trade unions as mentioned above, the amended VGCL Statute also recognizes the role of rank-and-file workers in trade union organizing. Accordingly, workers may establish an organizing committee at the workplace, responsible for conducting campaigns, receiving workers’ application letters to join the trade union, and preparing for the congress for the establishment of the trade union when a sufficient number of members, as prescribed by the VGCL’s Statute, has been reached. Nonetheless, the establishment and operation of the workplace trade union still requires the acknowledgment of the immediate upper-level trade union in order to be considered lawful.31)

The new law also entitles immediate upper-level trade unions to represent and protect the legitimate rights and interests of workers in non-unionized enterprises at the workers’ request.32) The Vietnamese government has promulgated a new decree in this regard. Accordingly, the role of immediate upper-level trade unions in representing and protecting the rights and interests of workers in non-unionized enterprises includes: consulting workers on employment contracts; representing the workers’ collective to implement collective bargaining and monitoring the implementation of concluded collective bargaining agreements; partnering enterprises to develop and monitor the implementation of wage scales, wage tables, labor norms, wage payment regulations, bonus payment regulations, and work regulations; conducting dialogues with enterprises to settle issues concerning the lawful rights and interests of the workers; working with relevant organizations to guarantee labor dispute settlements in accordance with law; requesting settlement by the competent authority when the lawful rights and interests of the workers/workers’ collective are violated; representing the workers/workers’ collective to request for a settlement in court when these rights and interests are violated; representing the workers’ collective in legal proceedings in labor, administrative and/or bankruptcy cases; and organizing and leading strikes.33) Part-time trade union officers are granted minimum working hours for performing trade union activities. Presidents and/or vice-presidents of workplace unions are entitled to at least 24 working hours per month; part-time trade union representatives who are members of workplace unions’ executive committees, heads, and deputy heads of trade union groups in charge of trade union activities are entitled to at least 12 working hours/month.34)

In addition, the act of preventing part-time trade union officers from using their working hours to undertake trade union activities; not paying them for the time they spend on trade union activities; and excluding full-time trade union officers from benefits enjoyed by other workers, is now liable to a fine ranging from VND 5,000,000–10,000,000 (around EUR 175–349 or USD 237–473).35) The new law also provides a better protection mechanism for workers who are working as part-time workplace trade union officers. In the event that a part-time trade union officer’s employment contract expires while he/she is still serving the trade union term, the officer is entitled to prolong his/her contract until the end of the trade union term.36) And for the first time, employers will be fined VND 10,000,000–15,000,000 (around EUR 350–524 or USD 473–710) for not extending the expired employment contracts in such an event.37) Finally, if part-time trade union officers are illegally dismissed, trade unions can request for intervention by competent authorities, taking the case to court if necessary. In the meantime, the unlawfully dismissed officers will be supported by the trade unions in their search for new jobs and will be provided with allowances.38)

Concluding Remarks

Despite high trade union density in Vietnam, the formalistic operations of workplace trade unions are one of the main causes of increased labor unrest in recent years. Trade union organizing free from employers’ interference is the decisive factor in enabling workplace trade unions to function effectively. Recently, the VGCL implemented initiatives in this direction, which served as input for revising the Trade Union Law of 2012 and the Labour Code of 2012. The new legal framework will create more opportunities for immediate upper-level trade unions in dealing with enterprises.

However, there are challenges ahead, one of which is the heavy workload of full-time trade union officers. Not only are they burdened by tasks irrelevant to trade union operations, as a consequence of the VGCL being an affiliated organization to the CPV, there is also a severe imbalance in the number of full-time trade union officers compared with the number of enterprises, workplace trade unions, and trade union members.

The new legal framework imposes stricter sanctions against anti-unionism acts committed by the employers and regulates the protection of part-time trade union officers at the workplace. However, whether the new legal provisions will be strictly enforced in practice very much depends on the commitment of relevant authorities—the VGCL and its immediate upper-level trade unions—in identifying anti-unionism acts committed by the employers.

Another challenge lies within the VGCL itself. A synchronous understanding and coherent interpretation of the VGCL’s policies among the upper-level trade unions is necessary if the involvement of employers in the establishment of the workplace trade unions is to be avoided. Officers of the VGCL and its trade unions also need to be more open and ready to apply different, innovative ways of trade union organizing.

Accepted: May 27, 2013

Acknowledgments

The author would like to express her gratitude to the autonomous referees for their valuable comments in the previous draft of the article. My thanks also go to Ms Narumi Shitara for her effective facilitation and instruction, and to Ms Wee Wong for her editorial assistance. I wish too to thank my colleagues Thu Huong and Van Binh at the Industrial Relations Project, ILO office in Hanoi for their support in documentation and material-gathering. Any errors contained herein are mine.

References

Amended Statute of the Vietnam General Confederation of Labour (VGCL), approved by the National Trade Union Congress, July 30, 2013.

Circular No. 76/1999/TTLT/BTC-TLDLDVN, June 16, 1999, on the contribution of trade union dues; and Circular No. 17/2009/TT-BTC, Section 3a, January 22, 2009, on the contribution and use of trade union dues in foreign-invested enterprises and units.

Constitution of Vietnam, April 15, 1992.

Decision No. 525/QĐ-TLĐ, April 25, 2011, on temporary regulation of wages and allowances of trade union delegates.

Decision No. 953/QD, July 20, 2010 of the Presidium of VGCL, on the establishment of pilot working groups for innovating trade union organizing and establishing trade unions, and improving the linkage between upper-level trade unions, workplace trade unions, and workers.

Decree No. 95/2013/ND-CP, August 22, 2013 of the government, on administrative sanctions concerning labor, social insurance, and the sending of Vietnamese workers abroad to work under contract.

Decree No. 43/2013/ND-CP, May 10, 2013 of the government, detailing Article 10 of the Trade Union Law on the rights and responsibilities of trade unions in representing and protecting the lawful and legitimate rights and interests of workers.

Decree No. 44/2013/ND-CP, May 10, 2013 of the government, detailing the implementation of a number of Articles of the Labour Code on employment contracts dated February 5, 2013.

Decree No. 133/HĐBT, April 20, 1991 of the Council of Ministers, guiding the implementation of the law on trade unions.

International Labour Organization (ILO). Convention No. 98 on the right to organize and collective bargaining, 1949.

Labour Code, June 18, 2012.

Law on organization of the People’s Court, April 2, 2002.

Law on public cadres and civil servants, November 13, 2008, approved by the National Assembly.

Law on trade unions, June 20, 2012.

Plan No. 13/KH-TLD, June 22, 2012 of the Vietnam General Confederation of Labour (VGCL) on continuously implementing pilot activities of the VGCL in the transitional period to December 31, 2012.

Plan No. 2202/KH-TLD, December 27, 2010 of the Vietnam General Confederation of Labour (VGCL), on implementation of the pilot program to innovate trade union organizing and improve the linkage between upper-level trade unions and workplace trade unions.

Resolution No. 07/NQ-TLD, July 18, 2008, on developing and strengthening the capacity of trade unions in small and medium enterprises.

Ban Mai. 2013. Lưc lượng lao động vẫn “thừa lượng, thiếu chất” [The labor force is abundant in quantity but short in quality]. The Saigon Times, April 25, 2013, accessed September 8, 2014, http://www.thesaigontimes.vn/Home/xahoi/doisong/95327/Luc-luong-lao-dong-van-%22thua-luong-thieu-chat%22.html.

Đức Minh. 2012. Cơ chế bảo vệ cán bộ hữu hiệu [Effective protection mechanism for trade union officers]. Lao Dong Newspaper, August 1, 2012, accessed March 20, 2013, http://laodong.com.vn/Tranh-chap-lao-dong/Co-che-bao-ve-can-bo-huu-hieu/76428.bld.

―. 2009. Sẽ có cán bộ công đoàn chuyên trách [There will be full-time trade union officers]. Tien Phong Newspaper, October 19, 2012, accessed March 10, 2013, http://www.tienphong.vn/Thoi-Su/Tin-Tuc/174974/Se-co-can-bo-cong-doan-chuyen-trach.html.

International Labour Organization (ILO). 2012. Context Analysis Needs Assessment and Recommendations for Phase 2 of Apheda Project. Hanoi.

Lê Nho Lượng. 2011. Minutes of Tripartite Conference on Industrial Relations in Binh Duong Industrial Zones. Tripartite conference on industrial relations in Binh Duong industrial zones, Binh Duong province, July 22.

Lê Trường Sơn. 2010. Cán bộ công đoàn như lính cứu hộ [Trade union officers are like firefighters]. Lao Dong Newspaper, August 5, 2010, accessed March 27, 2013, http://laodong.com.vn/cong-doan/can-bo-cong-doan-nhu-linh-cuu-ho-7034.bld.

Nguyễn Duy Vũ. 2012. Công tác phát triển đoàn viên, thành lập CĐCS sau hơn nửa nhiệm kỳ thực hiện Nghị quyết Đại hội X Công đoàn Việt Nam [Trade union membership development and workplace trade unions establishment after more than halfway through the process of implementing the Resolution of Vietnamese Trade Union Congress, meeting session X]. Vietnam General Confederation of Labour (VGCL), January 16, 2012.

Nguyễn Ngọc Trung. 2012. Vai trò của công đoàn cấp trên trực tiếp cơ sở tại các doanh nghiệp chưa có tổ chức công đoàn [The role of immediate upper-level trade unions in non-unionized enterprises]. Vietnam General Confederation of Labour (VGCL), January 13, 2012.

Nguyễn Văn Bình. 2011. Tăng cường và bảo đảm tính độc lập, đại diện của công đoàn để tham gia một cách thực chất, hiệu quả vào các quá trình của quan hệ lao động [Strengthening and guaranteeing the independence and representativeness of trade unions in order to participate truly and effectively in industrial relations processes]. Hanoi: International Labour Organization (ILO).

Phong Cầm. 2011. Đình công nhiều vì lương tối thiểu quá bèo [Too many strikes due to overly low minimum wage]. Tien Phong Online, July 7, 2011, accessed March 27, 2013, http://m.tienphong.vn/thoi-su/544219/Dinh-cong-nhieu-vi-luong-toi-thieu-qua-beo.html.

Quang Chính; and Việt Lâm. 2012. Cần phấn đấu giảm 50% số vụ đình công [It is important to strive to reduce strikes by 50%]. Lao Dong Newspaper, February 22, 2012, accessed March 15, 2013, http://laodong.com.vn/Cong-doan/Nam-2012-can-phan-dau-giam-50-so-vu-dinh-cong/626.bld.

Thu Trà. 2012. Hạn chế thao túng hoạt động công đoàn của người sử dụng lao động [Minimizing employers’ influence on trade union activities]. Lao Dong Newspaper, March 24, 2012, accessed March 27, 2013, http://laodong.com.vn/cong-doan/han-che-thao-tung-hoat-dong-cd-cua-nguoi-su-dung-ld-56999.bld.

―. 2008. Tập trung vào vấn đề bảo vệ người lao động [Focusing on the protection of workers]. Lao Dong Newspaper, November 5, 2008.

Tự Cường. 2012. Doanh nghiệp vừa và nhỏ vẫn khó tiếp cận vốn [Small and medium enterprises face difficulties in accessing capital]. Daibieunhandan, October 5, 2012, accessed March 15, 2013, http://daibieunhandan.vn/default.aspx?tabid=75&NewsId=259982.

Vietnam, Centre for Industrial Relations Development (CIRD). 2012. Kế hoạch phát triển quan hệ lao động tại thành phố Hồ Chí Minh trong giai đoạn 2013–2020 [Master plan for industrial relations development in Ho Chi Minh City in the period 2013–2020]. Hanoi.

Vietnam, General Statistics Office of Vietnam (GSO). 2010. Population and Employment, accessed May 19, 2012, http://www.gso.gov.vn/default_en.aspx?tabid=467&idmid=3&ItemID=9875.

Vietnam, Ministry of Labour, Invalids and Social Affairs (MOLISA). 2012. Báo cáo nghiên cứu về Công ước số 98 của Tổ chức lao động quốc tế [Research report on Convention No. 98 of the International Labour Organization]. Hanoi.

Vietnam, Trade Union of Binh Duong Industrial Zones. 2010. Báo cáo khảo sát về hoạt động của công đoàn cơ sở và mối quan hệ với công đoàn cấp trên cơ sở [Report on the survey of operations of local-level trade unions and relationships with upper-level trade unions]. Binh Duong province.

Vietnam, Vietnam General Confederation of Labour (VGCL). 2011a. Báo cáo đánh giá hoạt động thí điểm đổi mới cách thức tổ chức đoàn viên, thành lập tổ chức công đoàn và tăng cường mối liên kết giữa công đoàn cấp trên với công đoàn cơ sở và người lao động từ tháng 11/2010 đến tháng 12/2011 [Evaluation report on the pilot program: Strengthening representational capacity of the trade union through innovative ways in union organizing, establishing workers’ representative organizations and improving the linkage between upper-level trade unions and grassroots unions and workers from November 2010–December 2011]. Hanoi.

―. 2011b. Báo cáo về ngừng việc tập thể và đình công từ năm 2006 đến tháng 4 năm 2011 [Report on collective work stoppage and strike from 2006–April 2011]. Hanoi.

―. 2010. Báo cáo khảo sát về phát triển đoàn viên và thành lập công đoàn cơ sở [Report of survey and research on organizing and recruiting members at enterprise level]. Hanoi.

Vietnam, Vietnam General Confederation of Labour (VGCL) and International Labour Organization (ILO) Industrial Relations Project. 2012. VGCL Initiatives. Hanoi.

―. 2011. Research Report on Membership Development, Workplace Union Organizing and Collective Bargaining. Hanoi.

1) During the revision process of the Trade Union Law of 1990, a proposal was submitted to enable foreign workers working in Vietnam to join trade unions affiliated to the VGCL, as mentioned in Article 5 of the latest draft 10 of the Trade Union Law proposal of April 30, 2012. However, this proposal was not accepted and the Trade Union Law of 2012 still excludes the right to trade unions of foreign workers in Vietnam.

2) Article 5 of the Trade Union Law of 2012 and Article 1 of the VGCL Statute amended in 2013.

3) Article 4, Section 1, Section 2; and Article 7 of the Trade Union Law of 2012, approved by the National Assembly on June 20, 2012 and effective from January 1, 2013, replacing the Trade Union Law of 1990.

4) This refers to strikes that are not organized and led by workplace trade unions and which are carried out without respecting legal procedures.

5) The Labour Code of 1994 has been replaced by the Labour Code of 2012, which was approved by the National Assembly on June 18, 2012 and took effect from May 1, 2013.

6) This initiative was regulated by Decision No. 953/QD, dated July 20, 2010 of the Presidium of VGCL on the creation of pilot working groups to innovate trade union organizing and the establishment of trade unions, and to improve the linkage between upper-level trade unions and workplace trade unions and workers; comprehensive Plan No. 2202/KH-TLD, dated December 27, 2010 of the Vietnam General Confederation of Labour on the implementation of the pilot program to innovate trade union organizing and improve the linkage between upper-level trade unions and workplace trade unions. This initiative was implemented in Binh Duong province on December 31, 2012, as mentioned in Plan No. 13/KH-TLD, June 22, 2012 of the Vietnam General Confederation of Labour.

7) See the instructions (in Vietnamese) of immediate upper-level trade unions, e.g., Federation of Labour of District 1, Ho Chi Minh City: http://www.ldldq1hcm.gov.vn/thutucthanhlapcongdoan.aspx (accessed October 3, 2013); Federation of Labour of Binh Tan District, Ho Chi Minh City: http://ldldbinhtanhcm.gov.vn/vn/default.aspx?cat_id=806 (accessed October 3, 2013); Trade Union of the Industrial Zones of Ha Nam province: http://hanam.gov.vn/vi-vn/bqlckcn/Pages/Article.aspx? ChannelId=39&articleID=60 (accessed October 3, 2013), etc. for more details of the procedures for establishing workplace trade unions.

8) Items 1.3 and 1.4 of Guidance No. 703/HD-TLD prohibit honorary trade union members from voting in meetings and congresses or from holding leadership positions at any level.

9) Article 2b of Circular No. 76/1999/TTLT/BTC-TLDLDVN and Section 3a of Circular No. 17/2009/TT-BTC.

10) Article 26, Section 2 of the Trade Union Law of 2012.

11) Section 1, Resolution No. 07/NQ-TLD, dated July 18, 2008 on development and strengthening the capacity of trade unions in small and medium enterprises.

12) This is a summary of the innovative organizing approach implemented by trade unions in the economic zones of Hai Phong city; the industrial zones and processing zones of Binh Duong province, and the Federation of Labour of District 12, Ho Chi Minh City in 2011. The author has participated in these activities alongside the trade unions.

13) Summarized by the author.

14) Summarized by the author.

15) Article 7, Article 8, and Article 19 of Decision No. 1521/QD-TLD, dated September 29, 2006 of the VGCL Presidium, regulating the establishment, organization, and operation management of the workplace trade union delegate support fund.

16) Article 106, Section 2b of the Labour Code of 2012 provides that supplementary working hours of the workers shall not exceed 50 percent of the normal working hours in a day. Regulation for weekly work provides that the sum of normal working hours and overtime working hours shall not exceed 12 hours per day, and the sum of overtime working hours shall not exceed 30 hours per month and 200 hours per year. In special cases, this can be extended to but not exceed 300 hours per year.

17) Workers may enter into employment contracts with multiple employers as prescribed in Article 30, Section 3 of the Labour Code of 1994 amended and supplemented. However, this issue was regulated in neither the Labour Code of 1994 amended and supplemented nor in Decree No. 44/2003/ND-CP, dated May 9, 2003, detailing and guiding the implementation of a number of articles of the Labour Code on employment contracts. Things have changed with the promulgation of the Labour Code of 2012. The Vietnamese government has promulgated Decree No. 44/2013/ND-CP of the Government dated May 10, 2013, which has taken effect since July 1, 2013. This decree specifies the employees’ participation in social insurance and health insurance, and occupational health and safety issues when entering into employment contracts with multiple employers as prescribed in Article 4 and Article 5. It is hoped that the new legal framework will create more opportunities for workers to work at different jobs at the same time in order to improve their income situation.

18) Summarized by the author.

19) Summarized by the author.

20) Summarized by the author.

21) This is the case of a workplace trade union with 27 members drawn from different small enterprises in Tan Thoi Nhat ward, formed by the Federation of Labour of district 12, Ho Chi Minh City in 2011. It operates under the direct management of the Federation of Labour of district 12, Ho Chi Minh City.

22) Article 4, Section 1, Section 2; and Article 70, Section 2 Law on public cadres and civil servants.

23) The competent authority here refers to the CPV as mentioned in Article 66, Section 6 of the Law on public cadres and civil servants approved by the National Assembly, dated November 13, 2008 and taking effect from January 1, 2010.

24) Article 23, Section 2 and 3 of the Trade Union Law of 2012.

25) Article 9, Section 1, 2 and 3 of the Trade Union Law of 2012.

26) Article 24, Section 3 of Decree No. 95/2013/ND-CP of the government, dated August 22, 2013, on administrative sanctioning in the field of labor, social insurance, and sending Vietnamese workers abroad to perform work under the contracts. This has been in effect since October 10, 2013 and replaced Decree No. 47/2010/ND-CP dated May 6, 2010, Decree No. 86/2010/ND-CP dated August 13, 2010 and Decree No. 144/2007/ND-CP dated September 10, 2007.

27) Article 24, Section 2c of Decree No. 95/2013/ND-CP.

28) Article 16, Section 1 of the Trade Union Law of 2012, and Article 189, Section 2 of the Labour Code of 2012.

29) Article 16, Section 2 of the Trade Union Law of 2012.

30) Article 24, Section 2dd of Decree No. 95/2013/ND-CP.

31) Article 2, Section 1b and Article 17, Section 1a, b, and dd of the amended VGCL’s Statute of 2013; and Article 5, Section 2 of the Trade Union Law of 2012.

32) Article 17 of the Trade Union Law of 2012.

33) Article 13, Section 1 of Decree No. 43/2013/ND-CP dated May 10, 2013, in effect since July 1, 2013, spelling out Article 10 of the Trade Union Law on rights and responsibilities of trade unions in representing and protecting the lawful and legitimate rights and interests of workers.

34) Article 24, Section 2 of the Trade Union Law of 2012.

35) Article 24, Section 2a, 2b and 2d of Decree No. 95/2013/ND-CP.

36) Article 25, Section 1 of the Trade Union Law of 2012.

37) Article 24, Section 3d of Decree No. 95/2013/ND-CP.

38) Article 25, Section 3 of the Trade Union Law of 2012. This regulation refers to Decision No. 1521/QD-TLD dated September 29, 2006 of the VGCL Presidium, mentioned above, which provides a regulation on the establishment, organization, and operation of the fund for workplace trade union delegate support.