Contents>> Vol. 4, No. 1

Playing along the Perak River: Readings of an Eighteenth-Century Malay State

Husni Abu Bakar*

* Department of Comparative Literature and Foreign Languages, University of California, Riverside, 900 University Ave. Riverside, CA 92521, U.S.A.

e-mail: ssyed005[at]ucr.edu

DOI: doi.org/10.20495/seas.4.1_157

This essay questions the construction of cartographic, historical, and literary artifacts underlying the cognitive foundations of an eighteenth-century Southeast Asian state on the Malay Peninsula—Perak—by exploring alternative modes of reading. Through a narratological and historiographical exploration of nonconventional textual elements in Misa Melayu—a Malay text that contains accounts of Perak’s statecraft—and several other primary and secondary sources, I seek new, alternative, more playful, and enlightening ways of navigating and thinking about a Malay(sian) geopolitical entity beyond prescribed Cartesian maps and boundaries.

Keywords: Malay, Malaysian, narratology, cartography, hermeneutics, historiography

Perak: An Introduction

Among an old bundle of notes1) compiled by the British officer W. E. Maxwell2) on the royal families of Perak, Barbara Andaya—an Australian historian researching on the eighteenth-century Malay state of Perak—discovered a Malay map dated 1876. She included this map in the introductory pages of her doctoral dissertation, later published as a book titled Perak: The Abode of Grace (1979). If one were to categorize this work, it would not be inaccurate to call it a history of Perak. To be more specific, it is a history of the Malay state of Perak in the eighteenth century. If one were to read about the state at present, it would usually be described in terms of its primary resource—tin, the mineral that mythically gave the state its name (perak in Malay means “silver,” referring to the color of the alluvial tin deposits abundant in the state) and its constantly changing political situation following the victory of the opposition coalition in March 2008 and the subsequent takeover by the ruling government of Malaysia.

A precursor of Andaya’s work in Perak history is R. O. Winstedt and R. J. Wilkinson’s A History of Perak (1974), which includes three articles by Maxwell: two on historical manuscripts and one on “Shamanism in Perak.” Central to both histories—Andaya’s and the Europeans’—is the presence of trade, as events with regard to Perak history are explained in terms of the concentration and movement of capital, complex networks of kinship and power, and multifaceted relations between factions competing for control of Perak’s resources. These factions included the British, the Dutch, the Achinese, the Bugis, the Perak Malays, and the Siamese. The centrality of the presence of trade in histories is indicative of a modern understanding of the English word “history” as being laden with dates, timelines, important agents—usually those in power—and the overarching presence of trade as the main catalyst of events. Something Niall Ferguson systematically points out in The Ascent of Money (2008), that “financial history is the essential back story behind all history,” is iterated by Winstedt and Wilkinson in the introduction of their book: “. . . at the back of all Perak history has been trade” (1974, 1). The sections on Perak in national histories have, unsurprisingly, followed this tradition, and as a result Perak is popularly known in Malaysian history for two events: the signing of the Pangkor Treaty of 1874, which allowed the British to act as royal advisers to the Malay sultans, effectively starting the British Malaya period of Malaysian history; and the murder of J. W. W. Birch, a British resident, by Seputum, a slave of the royal chief Dato Maharajalela.

With the prominence of trade and printed sources in historiography, it is easy to overlook the cognitive, linguistic, and cultural nuances in the paradigm that underlie native historical source materials, such as the 1876 Malay map and Misa Melayu, the eighteenth-century Malay text about the sultanate of Perak in that century. I contend that the historical approach to these source materials must be balanced with complementary and supplementary information, as well as other modes of comprehension gained from alternative readings that illuminate aspects beyond historical considerations.

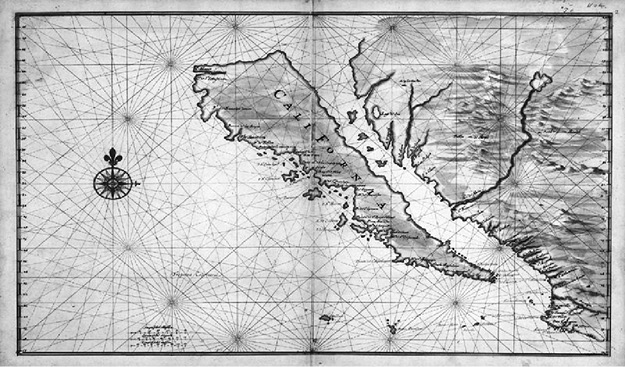

Fig. 1 A 1639 map of California as an island, apparently influenced by a quote from Las sergas de Esplandian (1510) by Garci Rodriguez de Montalvo, in Jacobs (2009)

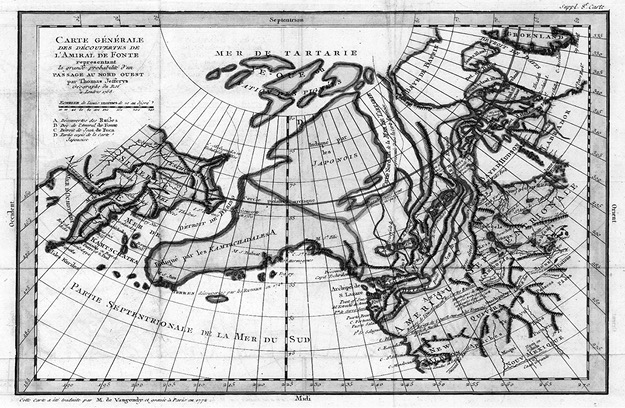

Fig. 2 A 1762 update of an English map by Didier Robert de Vaugondy, cited by Jacobs (2009) as “a prime example of wishful mapping.” Taken from Strange Maps blog: http://bigthink.com/strange-maps (accessed on November 30, 2013)

Unframing Cartographic, Historical, and Literary Myths of/on the Peninsula

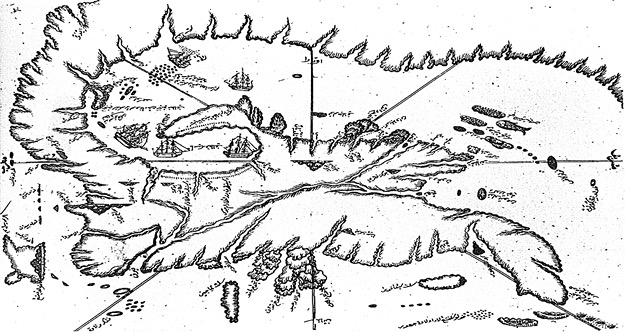

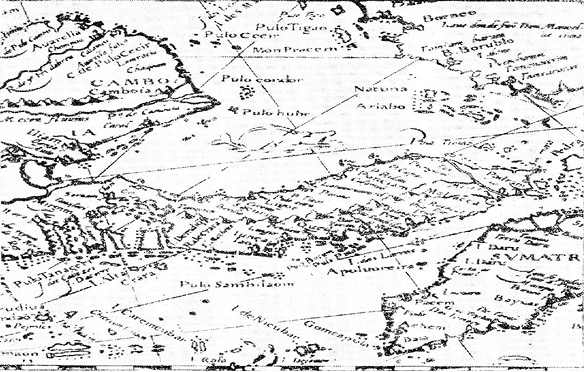

Strange Maps, an anthology of rare maps, compiles and discusses nonconventional cartographic curiosities, including maps with nonexistent waterways or water bodies such as an eighteenth-century map showing the mythical Northwest Passage3)—a fictional aquatic route from the Gulf of California to the St. Lawrence River near Quebec—and a 1639 map depicting California as an island (Jacobs 2009). The map in Fig. 3 shows a similar mixture of fact and myth: both the Perak and Kelantan Rivers (whose estuaries are located in the southwest and northeast of the peninsula respectively) geographically exist as separate rivers instead of the single continuous flow represented as a canal running through the Malay Peninsula. Beyond our appreciation for these aspects of an old cartographic document, there is a story about the production of the map, about the representation of a currently nonexistent waterway, and the most interesting one of how we, as (post)modern map readers should read these imaginative depictions. The transpeninsular channel appears in 46 other European maps predating the one discovered by R. H. Phillimore (1956), and part of it actually represents a penarikan,4) a semi-aquatic route for sea vessels through which ships have to be dragged (Wheatley 1996). The directions of the bowsprits seem to indicate that the ships have just passed through the transpeninsular channel on their way to Pattani, a renowned regional and international trade center in the eighteenth century.

Fig. 3 An early eighteenth-century Malay map of the Malay Peninsula with the mysterious Perak–Kelantan transpeninsular channel. Despite its geographical inaccuracies, the map served its purpose by showing the most convenient trade route for ships going to and from Pattani (Phillimore 1956).

In ancient maps of the Malay Peninsula, there is no one fixed name for any location; the names change and keep getting revised from one map to another, as do the representations of the Southeast Asian5) landmass as a sub-unit of the larger continent of Asia. Lineages of Portuguese, Greek, Arab, Turkish, and Chinese cartographers who wished to map the world mostly worked on maps that were drawn by sailing explorers, or privateers, who explored uncharted waters and documented them using their own craft. Through comparing, copying, and charting various cartographic representations of the water and land bodies, the mapmakers came up with very diverse ideas on how to represent the world and its constituents. The first person to map a space/place would most commonly be the authoritative voice in deciding how a continent or a sea would look on a map, gaining a certain kind of primacy over the people who came after and subtly subjugating the latter under an old, overarching spell of cartographic canonicity. Such is the effect of Ptolemy on the mapping of the Malay Peninsula, which went through several revisions of cartographic representation—from Aurea Chersonese (the Golden Chersonese), Malacca with its various spellings (Malacha, Malacca, Mallacqua, Malaca), Alta India, Malaya—each of them distinctly different yet indirectly reflecting those that came before. A question that could be asked here is, What made the cartographer decide not to merely reproduce older names and come up with new ones? Why, or how exactly, did Southeast Asia and its contents change on these fifteenth- and sixteenth-century maps? The answer lies partially in the predominant cosmological understanding that the cartographers had, and probably also in the developments that pushed exploration and cartography as ways of documenting parts of nature into a cyclical stage of constant revisions, parallel with the ebbs and flows of linguistic change that inevitably pass with time. More pressing questions about these maps are: What were the bases of the changes in place names? What are the factors that underlie a cartographer’s inclination to rename a place/space and/or represent it in a different way from the way it has been represented before?

The Ptolemaic Southeast Asian mainland is retained as well, though it is dwarfed by the false peninsular subcontinent. Martellus places various Southeast Asian islands known from Marco Polo and other travelers in relation to the bogus peninsula rather than true Ptolemaic Malaya. He also inscribes the new subcontinent with Polian comments about the Malay Peninsula, reinforcing the original error. The Martellus map (or its unknown prototype) thus gave birth to an error that would have a profound impact on the mapping of Southeast Asia, as well as on the mapping of America, for the next half century. (Suarez 1999, 94)

Cartographic errors, at least in the case of the maps mentioned above (if not the entire corpus of pre-modern Southeast Asian maps), can be attributed to their conformity to the three basic attributes of modern geographical and geometrical cartography, “scale, projection and symbolization,” where “each element is a source of distortion” (Monmonier 1996, 5). Mostly the errors are results of the fictive imaginaire of the cartographers transferred onto a form that requires metrical correctness, based on the modern functions of the map—to delineate landscape and land space, for purposes of determining one’s loci in the universe’s infinite topoi. Indeed, reason-based fact-making did not come to the surface in maps including the Malay Peninsula until the late eighteenth century via Dutch and English maps. Against these maps, a map such as the 1489 Martellus map of the “dragon-tail” peninsula, which causes uncertainty regarding the land space it represents—between Latin America and Southeast Asia (which includes the Malay Peninsula)—would seem incongruent. Complications arise in the onomasto-genesis of the place and space names that populate the maps, as well as the directionality of the peninsula, which begs for new and more flexible hermeneutics in cartography.

William Richardson (2003) rejects the popular assumption that the peninsula actually represents Latin America, particularly around Tierra del Fuego and the Strait of Magellan, due to the fallibility of the toponymic claims and coordinate-based feature analysis on the “dragon-tail” peninsula, citing the suggestion as “not substantiated.” Thomas Suarez (1999) likened the peninsula to a phantom, dubbing it “fake” due to its non-corroboration to the Ptolemaic “truthful” map of Southeast Asia. Present standards of cartography would make any serious consideration of the errors on the Martellus map irrelevant and unimportant, as it is not a geometric map. Similar to these is a 1639 map showing California as an island, which apparently internalized a derivational error from an oft-referenced and rarely seen fictional text,6) positing a strait between California and mainland North America. Educated, yet conjectural, error analyses on these maps could be sidestepped by taking into account the meta-fact that the errors are errors only because they do not corroborate the spectral factuality of the geographies of Ptolemy and Mercator. Being temporally flanked by these two main progenitors of classical cartography, Martellus’s map is one of many that are full of false, hyperbolized errors that provide grounds for fascinating origin myths for place names and land shapes in a present-day map.

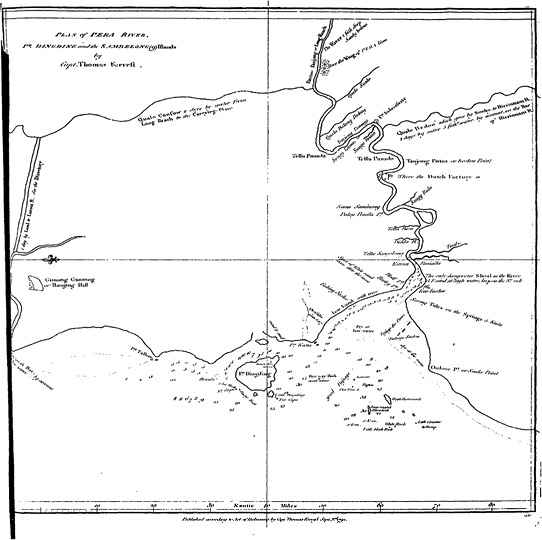

Fig. 4 Forrest’s map of the Perak River in his 1792 travelogue A Voyage from Calcutta to the Mergui Archipelago, Lying on the East Side of the Bay of Bengal; Describing a Chain of Islands, Never before Surveyed, that Form a Strait on that Side of the Bay . . ., pp. 31–32

As map readers living in the twenty-first century, we would find it convenient to dismiss all cartographic errors as just that—mere errors—and relegate the maps that contain them into the realm of obscurity and nonsense. When this happens, the “erroneous” maps are simply appreciated for their visual aesthetics and probably nostalgic value instead of being given the deep, steady attention-filled gaze one would give a modern map.

Considering the nuances that errors bring into the interpretation of maps, the 1792 British map of the same river that predates the Malay map probably makes more cartographical sense to the present-day reader, as it represents the river in a geodesically more accurate manner by replicating its curves and scaling them down to size, with one inch representing 10 nautical miles. The labels—mainly names of places, geographical points on land—share cartographic space with short descriptions of environmental conditions along the river and the coastline near the mouth of the river as well as principal tin mining areas, a Dutch factory, and a ruined Dutch fort. “Where the King of Perak lives,” his huge, magnificent istana, is represented by three little boxes surrounded by dots in the upriver area. The map’s main purpose seems to be navigation and trade. Unlike on the Malay map, the river does not occupy a central position. It does, however, feature a captain, who is also the cartographer (instead of a sultan)—Captain Thomas Forrest, a Renaissance seaman—whose name is written in clear font on the map itself.

Essentially, both the 1876 Malay map and the 1792 European map represent the Malay state of Perak circa late 1700s to late 1800s, with underlying narratives of how the geopolitical entity was conceptualized from two paradigms—a European one that has become so familiar and a Malay one that is still underdescribed. The former, prepared with measurement tools, is a product of print technology, is mainly land-based, and is generally more scientific compared to the latter, which was made through estimation, drawn with pen and ink, and focused on the flowing Perak River and its dendrites. In one of his short stories—On Exactitude in Science, fashioned poignantly as a quote from a seventeenth-century text—Jorge Luis Borges (1999) captures and almost ridicules the Enlightenment-based empiricism that is in constant search of the ultimate be-all-end-all way of representing reality and nature by telling readers the story of a fictional map that is the actual size of the empire itself.7) The map in the story serves as a supposed ideal for cartographers, yet it is impossible to produce, reminding us that there are always shortcomings in a geographical/scientific/cartographic map despite the impression of accuracy it gives. The exertion of divine control and rule over the entirety of its territory by the empire that Borges refers to is summarized in the map. To answer the fundamental questions of Malay statecraft in the eighteenth century—“What is Perak?” and “How is the state produced in print?”—the two maps of Perak offer radically different explanations based on the paradigms governing their constructions.

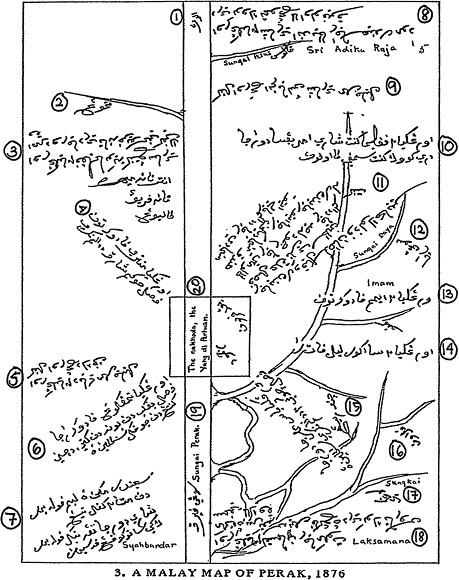

Partial Transliteration and Translation of the 1876 Malay Map

For the most part, the Jawi script toponymic labels and royal names are translated based on definitions given in R. O. Winstedt’s An Unabridged Malay-English Dictionary (1963):

1. Ulunya: upper waters (of a river), up-country, the interior of a country

2. Temong (“Temong”)

3. (Upside down) Orangkaya2 Panglima Bukit Gantang Seri Amar Dewaraja dari tanah Grik sampai ke paya laut.

Noble Chief of Bukit Gantang from the land of Grik to the sea swamp.

Antara tanah <. . .> tanah Periuk Keling

Between the land of <. . .> the land of Periuk Keling

4. Orangkaya menteri paduka tuan pasal hukum syarak didalam negeri

Noble Minister of His Royal Highness regarding the syariah law in the state

5. Orangkaya2 <. . .> Maharajalela kapal orang d.k.p.t(n?)

Nobleman <. . .> Maharajalela ship people

6. Orangkaya Temenggung paduka raja pasal <. . .> dan bunuh dan <. . .>

Noble <. . .> Admiral of His Royal Highness regarding killings and <. . .>

7. Syahbandar <. . .> lima puluh bahara dan mata2 kapal <. . .> Seri Dewaraja tiga puluh bahara

Harbormaster <. . .> 50 bahara8) and ship spies <. . .> Seri Dewaraja 30 satu kupang pada sebahara

one kupang for each bahara

8. Orangkaya2 Seri Andika Raja Syahbandar Muda dari Kuala Temong ke Ulu Perak. Sungai Alas

Noble Seri Andika Raja Junior Harbormaster from Kuala Temong to Ulu Perak. Alas River

(in Roman alphabets “Sri Adika Raja,” “Sungai Alas,” “5”)

9. Kapal Orang Enam Belas Seri Maharajalela

Ship of the 16 nobles of Seri Maharajalela

10. Orangkaya2 Panglima Kinta Seri Amar Bangsa Dewaraja dari Kuala Kinta sampai keulunya

Noble Chief of Kinta Seri Amar Bangsa Dewaraja from the estuary of Kinta to its source (ulu: upriver)

11. Raja bendahara wakil sultan <. . .> pasal adat negeri sekalian. Kalau mati raja <. . .> raja di dalam hendak menjadikan raja itu raja bendaharalah menjadi raja didalam balai itu. Kinta.

Royal Harbormaster representative of the sultan <. . .> regarding the traditions of the state. If the king dies <. . .> in the process of making that king, the Royal Harbormaster should be the king inside the hall. Kinta.

12. Sungai Raya (“Sungai Raya”)

Raya River

13. Orangkaya2 Imam Paduka Tuan. (“Imam”). Kampar.

Nobleman Imam Paduka Tuan. Kampar.

14. Orangkaya2 <. . .>

15. Orangkaya <. . .> Maharaja Dewaraja pasal cukai2 didalam negeri sekalian. Chenderiang

Nobleman <. . .> Maharaja Dewaraja regarding tax inside the entire state. Chenderiang

16. Palawan (“Palawan”)

17. Sungkai (“Sungkai”)

18. Orangkaya2 Laksamana Raja Mahkota <. . .> seratus bahara <. . .> dari kuala terus sampai ke laut. (“Laksamana”)9)

Noble Admiral Raja Mahkota <. . .> 100 bahara <. . .> from the estuary to the sea.

19. Sungai Perak (“Sungai Perak”)

Perak River

20. Nakhoda; Yang DiPertuan

Captain; His Royal Highness

In Fig. 5 the Perak River is depicted prominently with two arrow-straight lines in its center, flanked on both sides by meandrous tributaries flowing from various points. Accordingly, the Jawi text labels are diverse in their orthographical (or cartographical) alignment—upside down, diagonal, upright—and they are written in such a manner that there is no upright position to read the map. The main river itself is identified with the nakhoda “captain” and Yang diPertuan, “the one who is made Lord” or “His Royal Highness,” as also shown by the Romanized transliteration of the Jawi labels—a title assigned to Sultan Iskandar Dzulkarnain of Perak (r. 1752–65). The sultan is the chief character in Misa Melayu, an eighteenth-century Malay text containing accounts of the Perak royalty and their relations with Dutch Batavia. Similar to the river, the tributaries on the left and right are labeled not only with names of places but titles and names of Perak nobles, with brief descriptions of their legal and administrative roles in the state with regard to taxation, tradition, and criminal law. The top of the river is labeled ulunya, a Malay term that can refer to several things: “the upper waters (of a river)” or “upriver,” “up-country,” or “the interior of a country” and also “the head of.”

Fig. 5 A Malay map of Perak, 1876, from W.E. Maxwell’s notes, MS 46943, Royal Asiatic Society, London, as published in Perak: The Abode of Grace: A Study of an Eighteenth Century Malay State by Barbara Andaya (1979). Some words—names of places and court nobles—on the map have been transliterated by Andaya. Arabic numerals in circles are my annotations used as a guide in the transliteration and translation of the Jawi text to Romanized Malay to English.

It is not surprising that readers will find this map a little strange due to its lack of border lines, legends, metrical scale, and compass—the usual furnishings of a contemporary geographical map. In Misa Melayu, the Malay word peta (map)10) does not occur in its base form but as a passive verb, twice: once to describe the beautiful imagery of one of the nobles (Orangkaya Temenggung) conjured up in one’s thoughts, and the other time to describe the making of a blueprint of a ship. It is evident that the 1876 map was not necessarily a navigational tool among the Malays of Perak in the eighteenth century as much as it was a projection of human imagination, on paper, of the riverine state.

As part of the set of written documents about the history of the statecraft of Perak in the eighteenth century, the 1876 map is an invaluable piece of text. It tells another story of how the state could have been imagined in the past—through the flow of the Perak River and its tributaries combined with the titles of the court royals. Reading this map alongside Misa Melayu, a text that “celebrates not only the present but the tanda (signs) of that present—a new city, a fort, a mosque,”11) one might be reminded of the fact that the map itself could be considered a sign of the present or of modernity, and that it is as obscure as the text. It could be the case that this map, just like Misa Melayu, was produced at the request of a modernized sultan who wanted the state to be represented in a manner understandable to Europeans and other foreign elites or merchants that were dealing with the state government at that time. It would not be difficult to imagine the map being in the possession of the Perak elites, or the sultan specifically as part of his regalia, as suggested by old paintings of European kings and queens (and sometimes estate owners) with a globe or a map in the background. And much like other maps from the 1800s and earlier, the 1876 map would have been a piece of knowledge that was secret, sacred, and available to only a privileged few—the royal elites and British officers.

The word “map” could be a misleading translation or label for the 1876 text, just like the word “epic” is an inadequate translation for the Malay hikayat, a genre label under which Misa Melayu is subsumed. Although the surface forms of these two textual documents show features they share with other maps and epics, the underlying intentions and paradigms behind their production are overshadowed by the connotations of those labels.

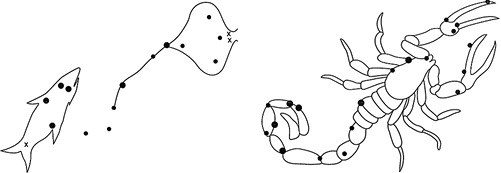

Fig. 6 Different paradigmatic interpretations of the same constellation: Scorpio is seen by Bugis seafarers as a shark and a stingray rather than a scorpion.

On the first few pages of Andaya’s 1979 monograph is a comparison of cartography (also epistemology) in the form of one map of Perak drawn by a European scholar and another by a Malay. The first one is Cartesian: it has boundaries and space contained within them, with various places labeled. On the Malay map there is a river with branches that are labeled with the places the sailing Sultan Iskandar visited, as depicted in the syair part of Misa Melayu. Although Andaya does not discuss much about the syair in her thorough historical narrative, she does call for a reexamination of the emphasis on land that has, for a long time, been the mainstay in Southeast Asian studies. On this precolonial Malay map of the state of Perak, there are accompanying notes that say, “. . . the raja is the captain and that the duties of ministers mirror those of crew members” (Andaya 2006). The river, which is just a rupturing line in the land-based European map of Perak, is the essence of the Malay one. Going by the metaphor presented with the map, the raja as captain and ministers as crew members, it may be inferred that the state of Perak itself, in precolonial Malay epistemology (or at least cartography, which is a misnomer), was imagined with the river as its quintessential core, rather than land space.

Water bodies in Southeast Asia, previously viewed through European lenses as just uninteresting interstices between pieces of land on which property could be built and profit gained, is currently being reexamined as a key aspect of life in Southeast Asia. Water was the conduit through which Muslim merchants’ ships and European galleons came in contact with various areas in Southeast Asia. In the final line of the sixth stanza in the syair in Misa Melayu, it is said that the sultan goes on a journey at sea (the word used here is bermain, which also means “play” and “go places”) in a state of “perfect faith” or sempurna iman, which could very well be an expression based on Muslim travelers who brought with them the word and the notion of iman. Andaya (ibid.) also mentions the arrival of a Dutch “stranger-king” on the shores of Sulawesi, whom local tribes turned to for help with settling disputes. In the seas of Southeast Asia European order did not get established in its full form, although there were attempts that resulted in Bugis seafarers being considered pirates because they did not heed European law (Rubin 1974, 31).12) The most famous Malay character in Europe is Sandokan, the “Tiger of Malaya,” a fictional pirate character created by Emilio Salgari in the novel The Tigers of Mompracem and featuring in cartoons as well as films. There are still communities of seafarers called Orang Laut, or “sea people” (Chou 1994; Ammarell 1999), who are well versed in aquatic navigation and who consider the infinite sea their home.

How do we reconcile the maritime discoveries above with myopic European histories of Southeast Asia, which for the most part were preoccupied with land and order instead of water and fluidity? How do the nautical relate to the Malay noetic at present and in the past? These questions can be the motivation for Southeast Asianists to contest—but not necessarily do away with—European historicist views to give some “space” (and “time”) to another way of viewing Southeast Asia. After all, it is part land and part water (mostly water), which should hint at the prospect of a harmonious coexistence between Euro-leaning (land-based) approaches and approaches that challenge them (maritime), like the waves lapping the shores of the many beaches in the region, altering the region’s landscape constantly and persistently (Maier 2003).

Perhaps Sandokan, as a fictional character, could lead us to understand the disparity between land and sea, and its implication on the establishment of order during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when British influence was spreading across the archipelagoes of Southeast Asia. As a rebel pirate, he is the nucleus of the main counterforce leading local natives against British colonization in Borneo, under the rule of White Rajah James Brooke. His demeanor is gentle and reserved, reminiscent of a Malay pendekar, warrior-like and fearless.

In Salgari’s novel cycle the spirit of the tiger is immortalized through the epithetic and zoomorphic character of Sandokan, who is dubbed the Tiger of Malay(si)a, fierce and relentless in his stance against the forces of colonization led by James Brooke. In one of the historically detailed film versions, he slays a tiger with a keris in the style of a true pendekar to save his love interest, Marianna, after she falls off her steed. Prior to that, another tiger is killed by a mysterious dark-skinned youth to save the nearby kampong from its terror.

Fig. 7 Langeren’s 1623 world map that shows the transpeninsular channel on the Malay Peninsula. Also shown is the Bornean island of Mompracem, the home of the fictional character Sandokan, Tiger of Malaya (Wheatley 1955).

Mompracem, in the films and novels, could be viewed as a microcosm of the entire colonized Malay world, or as one of the prime examples of how natives were more resistant to the Queen’s army on an island. For Salgari and many of his readers, who were likely mostly Europeans during the time when the novels were first published, Sandokan is possibly the only Malay hero created by a European in fiction, and thus he cannot help but reflect the traditional mold of a romantic hero. The only strange thing about him is that despite being respected and upheld as a leader by the locals, he does not really fit in their community and cannot be categorized as Malay. Yet, through his demeanor he performs as a Malay, in fact a Malay hero, to, for, and against the Europeans, who were probably charmed by the exotic, exoticized stories of traveling authors and their traveling heroes.

The tiger is a recurrent theme throughout Malaysian literature, political history, and pop culture. For instance, on the national emblem there are two Malayan tigers flanking the insignia; the national football team is called Harimau Malaya (harimau: tiger); P. Ramlee, Malaysia’s top silver-screen legend—as well as author, actor, director, scriptwriter—writes in Sitora Harimau Jadian about a horrifying man-tiger terrorizing a kampong. Long before its fame in modern works, the tiger as a metaphorical symbol appeared in Misa Melayu as a fierce, grandiose allusion reserved for the sultan:

Telah turun kenaikan Sultan, Sikap seperti harimau jantan, Terlalu indah rupa perbuatan, Dikarangkan syair ikat-ikatan.

[The sultan descended from his vessel, in a manner similar to a handsome tiger, gallant in form and demeanor, for him this syair is composed.]

Oral-based Malay texts such as hikayats and jatakas have been read, interpreted, and analyzed through examining the plots, characters, and motifs of the tales, along with Hindu epics as well as Persian and Arabic tales. For example, A.L. Becker analyzed Aridharma according to its “frames,” which are defined by “who is saying what to whom, about what, and in what language” (Becker 2000, 140). Through this analysis, a common story is identified between the Javanese tale of Aridharma and other texts such as the Malay Hikayat Syah Mardan (also known as Hikayat Indrajaya), the Thai Lin Ton, the Buddhist Kharaputta-jataka, and the Arabian Nights’ “The Ox, the Ass and the Farmer.” Farish Noor (2006) in his analysis of Hikayat Inderajaya identifies scenes and leitmotifs from the tale as being similar to those in the Burmese-Thai renditions of Vessantara-jataka and Jataka Wetsandon, particularly the exile of the main character into the forest as a form of purgatory in both tales. Aside from that, he relates the existence and interaction of Muslim, Hindu, and Buddhist elements in Hikayat Merong Mahawangsa and Hikayat Inderajaya to the historical context of the coming of Islam as a gradual process, replacing Hinduism and Buddhism as the main religion in the region.

Becker’s notion of “framing a tale” is helpful as an alternative way of analyzing ancient oral-based tales, beyond the language of strata and layers. Rather than being level upon level of influences based on temporal linearity, cycles of framing are posited as structural elements in which these stories are presented, which affect their mediation and perception and therefore also appreciation, or lack thereof, as historical or literary data. The justified emphasis on language allows analysts, like readers of the stories who I imagine to be fortunately unfamiliar with the systematic categorization of religious influences in literary studies, to read tales such as Aridharma as a Javanese story rather than a Hindu one that is glossed and coated with Javanese elements.

Readers (and listeners) of the hikayats with elements from Hindu epics—Hikayat Seri Rama or Hikayat Pendawa Lima or Hikayat Indraputra—must be acquainted with the characters from the Hindu epics and learn the differences and distinctions between them and, for example, the Islamic elements in the stories, before they can categorize them in different boxes. This is very unlikely in pre-modern times, as these boxes were constructed at a later point in history, used and prescribed by proponents of a European-based tradition of religious knowledge governed by Christian soteriology and emphasis on scriptural writing rather than oral-based tradition, and are usually consciously learned.

In the case of Misa Melayu, the boundaries of the text encapsulate a Malay narrative space that is populated by Malay, Tamil, Chinese, and European characters from the state of Perak in the eighteenth century, including the author. Commissioned by Sultan Muzaffar Syah III and begun during his reign, the hikayat frames important court events, palace traditions and customs, trade engagements between Dutch and Perak royals, as well as the establishment of edicts related to trade at the time. A significant part of the text is devoted to the sultan’s voyage along the river.

In the first frame there is the author presenting the genealogy of Perak rulers and their kin, in parables and episodes about traditional ceremonies, elephant hunting and fishing trips, funerals, trade dealings with the Dutch, celebrations, and events leading up to the sultan’s journey to sea. The royal characters speak in a high register of classical court Malay. Physically, the events in this frame take place within the court setting and multiple destinations—mini frames in themselves—across the entire state of Perak.

In the second frame, the author speaks to the reader in a humble narrative, poetic voice, by using the traditional first person pronoun patik reserved for an audience with the sultan, due to the fact that the text was commissioned by Sultan Muzaffar Syah. A lengthy syair charts the sultan’s journey, interspersed with poetic descriptions of royal figures, events, vessels—ships, boats, schooners, prows—that escorted the sultan on his trip. In the third frame, more contemporary voices such as the earliest readers and translators of the hikayat, Richard Winstedt and the publisher of the Pustaka Antara 1962 version, explain the text through summaries—one in English13) and the other in Malay—delineating the information from the text, charting the discursive paths through which the text might be further appreciated by the present-day reader. Arching beyond the other two frames, it is through the discursive, disciplinary frame that the hikayat is ultimately made to be understood as a historico-literary material to a larger public.

All Southeast Asian pre-modern and early modern texts, in whatever form they come in—maps, be they indigenous, political, water-based, or geo-based; and oral-based texts—are readable only with postmodern views that cannot disregard the frames that bring them to the surface, as inherent, albeit recognizable, parts of our reconstruction, reimagining, and fictionalizing of cosmographies of the past. Deliberate, conscious transgressions of these frames prevent oversimplifying, sweeping labels that often taint readers’ views from seeing specificities and diversities of the literary, spiritual elements in the texts, making way for novel narrative hermeneutics in reading a state’s past.

Playing with Strange Texts: Misa Melayu as Literary Artifact

. . . ada yang bermain membaca hikayat Jawa dan syair ikat-ikatan berbagai-bagai ragam bunyinya riuh-rendah siang dan malam.

[. . . there were ones “play-reading” a Javanese hikayat and syair arrangements with various modes of sounds in a hullabaloo, day and night.]

Figs. 8 and 9 A page from the manuscript of Misa Melayu (Maxwell 25, p. 77) showing the syair (left) and the 1876 map. The straight line depicting the river acts as an orthographic divider, similar to the blank space in the center of the manuscript page. On the map, as on the page, the central space is flanked by bits of narrative about Perak royalty and nobles and their activities at locations along the river.

The Malay word bermain is used multiple times in Misa Melayu14) to signify “playing” and “traveling” or “sailing.”15) In the quote above it is combined with the word membaca, which means “to read, or rather to read out loud,” as that would be the mode in which a hikayat such as Misa Melayu was experienced in the eighteenth-century Malay world. The written hikayat is sometimes compared (or contrasted) with Islamic texts because of its being written in Jawi, a written form of Malay that is “chirographically controlled” (Sweeney 1987, 54) and therefore has the same values as the scriptural medium of Islam—Arabic—and the orthographical medium of many Sufi tales—Farsi. Jawi stands taller than the unwritten, yet spoken, Malay, and its Islamic prestige is upheld as a “language of the book.” The word “Jawi,” from Persian Djawij, signifies “something that is placed,” “a placed language,” and also the adjectival form of “Jawa” used by Arabs for Java and Sumatra (ibid., 56). Moreover, in the kromo (royal) register of Javanese, “Jawi” shares the referent “Javanese,” conjuring up the lofty and esteemed prestige of the script as well as the high status of the court as the Javanese literary center, far from the realm of the wandering fakir or dagang “traveling mendicant” who exchanges stories in the oral/aural realm. In a letter to a Dutch officer, Raja Ali Haji, a Bugis poet,16) gestured to a semantic component of the syair that could only be accentuated by its orality. From a splendidly musical, rhythmic existence on the oral-aural domain, its richly textured and varied rhyme patterns (Teeuw 1966, 431–432)17) are relegated to being mere letters on a page, forcing the reader to comprehend it in its silence.

Syahdan jika sahabat hendak bermain-main satu waktu, coba panggil seorang orang Melayu yang pandai bersyair, suruh baca dengan lagunya yaitu seperti nyanyi, maka lebih terang lagi maknanya. (Putten and Al-Azhar 2007)

[Hence, if you want to have fun sometime, try to summon a Malay person who knows how to (recite a) syair, tell him to recite it melodically, like singing, so that the meaning becomes clearer.]

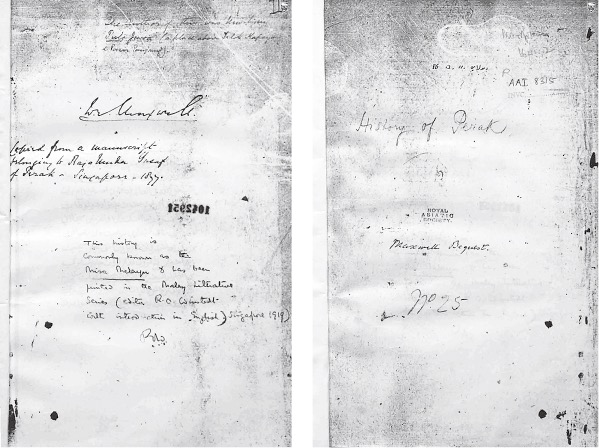

Figs. 10 and 11 The first two pages of the Maxwell 25 version of Misa Melayu, which display what could be identified as Maxwell’s signature and some remarks as recorded in Ricklefs and Voorhoeve’s Catalogue of Indonesian Manuscripts in Great Britain, display some telltale signs of the surfacing of the episteme “Misa Melayu. A history of Perak down to c. A.D. 1770, containing particulars on relations between Perak and Batavia, etc. Inside the cover a note by W. E. Maxwell: ‘copied from a manuscript belonging to Raja Muda Yusuf of Perak-Singapore_1877’. 121pp. Italian paper: Benedetto Gentili Vittorio’, 31.5×21.5 cm. 25 lines. Maxwell bequest, 1898.”

On the front page of the manuscript, in large cursive writing, is written “History of Perak.” There is a smaller stamp saying “Royal Asiatic Society,” under which is written “Maxwell Bequest.” On the same page as the colophon there is a note, possibly written by Winstedt: “This history is commonly known as Misa Melayu & has been printed in the Malay Literature Series (editor R. O. Winstedt—with introduction in English) Singapore 1919.”

Underneath this colophon is what seems to be Winstedt’s signature (R.O.W.?). Misa Melayu, as shown in the notes above, is framed as a “history of Perak,” a sultanate on the Malay Peninsula, and has been printed as in a piece of literature edited by Winstedt, evoking a “historical epic” mode of reading, legitimizing its use by historians to formulate a narrative based on “factual” information from the text and attributing it to Perak and its semantic extent, including the present-day space of the state, its people, and especially the Perak Sultanate. The episteme of history is what is evoked in the action of labeling the text as such, an action that, to a certain extent, influences subsequent readings and analyses of the text, which has now been homogenized and standardized—Maxwell 25 is the standard version transliterated into Roman alphabets. It was initially authoritatively described as a literary and historical text. Surely this is not a problem if there is a level field of comparison between Misa Melayu and the historical and literary works that scholars such as Winstedt and Maxwell upheld in their minds, works that became a yardstick against which Misa Melayu was measured. And naturally, works that correspond the closest to European ideals in history and literature, which are usually Homeric and come from the Greek and Latin conventions (as the word “epic” without fail suggests), are held in the highest regard.

The epistemes operating in this instance, which could be characterized as the “literary” and the “historical,”18) have far-reaching consequences in Malay historiography and the readings of Malay histories. For example, Andaya’s (1979) thorough narrative on the history of eighteenth-century Perak as a Malay state comparatively and meticulously analyzes Misa Melayu with Malay and Dutch historical sources.

The historian’s intellectual journey, starting with the text, then going out into the realm of context, asking circumstantial questions and finally coming back to the text to address any issues during the time the text was produced, is not too different from a literary theorist’s/narratologist’s. Of importance here are questions that deal with the second stage in the analytical reading above, concerning the paradigm of knowledge the text was produced in and how it compares to other contemporaneous sources, in other words, the occurrence of writing itself and how the structure of a narrative influences what kind of information is included and what kind is excluded in a text. A map, in this particular sense, is no different from a narrative because of the limitations imposed by the “need for selection”:

The need for selection means that every story contains, and is surrounded by, blank spaces, some more significant than others. When we create a fictional world, our decisions include geography, or setting, but also where and when a narrative begins and ends, who it involves and who it doesn’t, which actions and conversations are worthy of inclusion and which aren’t. (Turchi 2004, 42)

However, it is important to note here that a heightened awareness of “silences” in a text (especially one written in a language that is either temporally or spatially foreign) and a narratological mode of reading do not promise, in my view, a superior or a better reading. Rather, it is about exploring uncharted territories of over- and under-interpretations of that text based on epistemes that are related to it. After all, both the narratological and strictly historical modes of reading are inevitably problematic ways of reading old texts because they are strategic, teleological steps taken as a pathway to a goal and developed in the twentieth century.

O. W. Wolters (1999) practices a different type of textual analysis that does not require going out of the text, as most of the texts he discusses are authorless:

. . . the literatures of earlier Southeast Asia are a promising field for experimentation. Most literary materials are anonymous, so that one does not need to be distracted by questions about a writer’s situation or personal intentions. One does not immediately have to look outside the texts to account for what is inside. Instead, one has to learn to read groups of texts in the same culture and genre to discern the presence of a local social collectivity which is expressing itself through language usage. Textual studies can also highlight something which tends to be given short shrift in accounts of earlier Southeast Asia: elements of “strangeness” in the various cultures when compared with each other and with cultures in other parts of the world. Literary texts are bound to be “strange” because they depend on figurative language. Various forms of literary strangeness are part of the “ranges of experience” which need to be opened up to allow satisfactory general accounts of earlier Southeast Asia to be written. (ibid., 72)

Note both the generic, deductive framework used by Wolters and the “strangeness” with which he regards literary texts from another culture. It would be redundant to echo criticisms and shortcomings of Wolters’s research in terms of specificity and scope of the terms “culture,” “literature,” and “language usage.” Instead, I would like to point out the way in which he decentralizes authorial intention and deliberately brings attention to the strangeness of earlier Southeast Asian texts, which would include hikayats. I read this “strangeness,” which has not been given much emphasis before, as also being the “silences” that have not been much explored by modern historical readings of the hikayats, such as the readings of Misa Melayu by contemporary scholars such as Andaya (1979) and Arba’iyah Mohd Noor (2006). It could also be mentioned here that this “strangeness” can be posited not only due to the literariness of the texts but due to a perpetuation of standards of normalcy based on the established notions of “literature” and “figurative language.” Regarding this weak relation between strangeness and figurative language posited, this question comes to mind: What if in a particular language (culture language), say eighteenth-century Malay, what is now perceived as figurative language is the normative way of expressing oneself, something that is strange only through the constricted lens of present English literary standards?

Wolters’s focus on the literary aspects of old texts—although he still evaluates “literariness” from a Western standpoint—is crucial in providing a balance to the constant subjection of these texts to historicism, which sheds light only on certain parts of the texts (the “factual”) and relegates other parts to the realm of historical nonsense. Wolters ignores the episteme of the historical to focus on the literary. Wolters’s reading of Misa Melayu, much like Andaya’s, Winstedt’s, and mine, consists of “response statements” that are products of institutional academic training, conditioned by disciplinary traditions such as history and literature, that train the reader to look for, pay more attention to, and write more about certain parts or tropes in a text. A reader’s response usually contains a specific kind of information (that answers questions about a text asked in a particular discipline) without acknowledging its theoretical-methodological background, which is often taken for granted and to be less important than the information itself. Modern histories and scholarly narratives about Perak, as response statements to literary artifacts, inevitably contain information about the scholarly approaches of readers, which is unfortunately not given as much lip service as data concerning the geography and economy of the state.

A response statement aims to record the perception of a reading experience and its natural, spontaneous consequences, among which are feelings, or affects, and peremptory memories and thoughts, or free associations. While other forms of mentation may be considered “natural and spontaneous,” they would not be so in this context. Recording a response requires the relaxation of cultivated analytical habits, especially the habit of automatic objectification of the work of literature. . . . Normally, the act of objectification inhibits awareness of response. (Bleich 1975)

With this in mind, I analyze fragments from past readings and readers of Misa Melayu—Andaya, Wilkinson, Winstedt, and Maxwell—without unnecessarily historicizing every part of Misa Melayu, by switching back and forth between the two epistemes the “historical” and the “literary” to discover how the text became the subject of epistemological labeling and categorization.

I choose to read Misa Melayu as a discursive microcosm in which some Malay notions can be examined in their contextual uses so as to inform us more about the connections between those notions and the world in the spatial and temporal context in which Misa Melayu was written. This approach is similar to Michelle Rosaldo’s (1980) research on Ilongot notions of self and social life, in which she consciously veered away from treating language as merely “an ordinary vehicle of reference, logic and cognition” and instead examined the occurrences of “knowledge” and “passion” linguistically by navigating through nuances and metaphorical meanings beyond the simple gloss of a word. By doing this, I hope to get away from rigid analyses based on abstract concepts that are assumed to be universal (such as “border” and “trade”) and step closer to the “rough grounds” of the circumstances back then, specifically Malay language use in the eighteenth century. Basically, instead of scanning the text for information or certain facts that would supposedly tell us about the historical past like an ethnographer or a historian, I read the text as a reader who tries to be sensitive to “what language tends to pass over in silence.”

Unfortunately, this approach is still unpopular in mainstream scholarship on Southeast Asia, specifically Malay studies. Most popular histories of Southeast Asia cite trade and commerce as being major factors in the changes that occurred in the region, without explaining what the circumstances on the ground were, especially on the production, consumption, and circulation of texts (including maps) and how they traveled through time and space to become influential in present cognitive conceptions of Perak in the past.

These are all features that are not graspable if the complexities of the notion of “reading”19) are not examined in the oral/aural literary community. In Misa Melayu, for example, the syair (Malay poetic form), which is presented together with the prose part of the text, has been largely ignored by scholars—namely Winstedt and Andaya—who both consider the text to be a “history of Perak” as scribbled by Maxwell, the British scholar who initially obtained and owned the Jawi manuscript that was transliterated and printed in codex form.

Misa Melayu and the Quandary of Translation

The exact meaning of the first word in the text’s title Misa Melayu remains unknown to this day, and it is only appropriate that we begin any discussion of this text with an uncertainty that matches this lexical enigma. Maxwell, a British scholar of the Malay language who was probably stumped by this unfamiliar word, first speculated that it was a corrupted form of the Arabic loanword missal, which means “example.” For some time this became the meaning of the word for scholars of the Malay language. However, Maxwell later realized that his guess was wrong when he saw a Javanese text with the same word in the title,20) thus ruling out the possibility of its being misspelled. He then thought that the word was used in the title because of the text’s similarity in content to the Javanese text. His colleague Winstedt, bewildered by the guess, later pointed out that the word meant “water buffalo” in Javanese and was sometimes used as a nickname for a person. Winstedt expressed his doubts about this claim due to the fact that animal-based nicknames were not common among Malays. As ludicrous as they seem, these two guesses are all the present-day reader has if she or he is interested in figuring out the absolute meaning of the first half of the text’s title.

Melayu, translated into English as “Malay,” is a term that has been subject to increasing attention, contest, and deliberation by scholars—from historians to sociologists—in debates concerning a unifying ethos of groups of people spread throughout maritime and mainland Southeast Asia, mainly on the island of Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula (Matheson 1979). A vague ethnie construed based on language, culinary practices, way of life, and other artifacts of tradition, it is established on prescribed principles founded during colonial times and still relevant, especially politically, in Malaysia today—bahasa (language), raja (king), and agama (religion) (Shamsul A.B. 2004). For linguists, it is a category referring to a spectrum of Austronesian languages that are not always mutually intelligible, spoken in present-day Indonesia, Malaysia, southern Philippines, southern Burma, southern Thailand, Singapore, Brunei, Timor Leste, Sri Lanka, Easter Islands, and Madagascar. As a language, it has official status in Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, and Brunei, although it is important to note that different variants are spoken in different regions.21) For sociologists, anthropologists, and historians, Malay identity might be considered a social system of ethics and beliefs, documented in printed literature and practiced in everyday life by agents/subjects through spoken languages, mannerisms, customs, traditions, and rituals. Its origin remains buried and elusive, and as a categorical definition for an infinitely diverse group of people, it offers no scholarly escape from critically thinking about the diversity that exists within the group.

The academic field most concerned with terms such as “Malay” and more recently “Malayness” is Malay studies, in which classical Malay texts, mostly from the sixteenth up to the nineteenth century, have been the main foci as “native” sources. What I find most challenging is providing a balanced analysis of the geopolitical entity that transcends the formation of the nation-state of Malaysia, as Perak existed in texts and in Malay literature, before Malaysia was even formed by the union of the former British colonies on the Malay Peninsula and Northern Borneo (Sabah and Sarawak). Understandings of Melayu, Malay, and Malayness as identity and language have infinite variants based on whose definition it is: a Perak Malay might have a different understanding of Malay(ness) from a Kedah Malay or a Bugis or Mandailing, yet in many scholarly works there is the tendency to collapse it into one racial, linguistic, and cultural identity, ignoring the diversity within the category. To include every definition since the inception of the word/concept would be an insurmountable task, and what is provided in this essay is but a tiny piece of a giant puzzle, or perhaps a giant cultural chess game.

From a cornucopia of texts varying in content and form, those known as hikayats22)—Misa Melayu can be considered one—have been studied as important historical source materials because many of them contain genealogical and “panegyrical” stories of the origins of Malay sultanates (Braginsky 1993, 58). The hikayats are considered to contain valuable information on Malay history, and the contents of these stories are classified as “mythical,” “historical,” or otherwise,23) evaluated and scrutinized for “facts” that corroborate information from other sources—the bulk of Malay and European (mainly British and Dutch) writings about the region. It is a network of complex processes, involving many translations and cross-referencing, centered around the “historical method” as its guiding principle.

The popular Hikayat Hang Tuah, for example, has been branded a “historico-heroic epic”; it discusses the Melaka and Johor Sultanates and their relations with Jambi in Sumatra in the context of historical events, such as the Johor-Jambi war in 1666 (Braginsky 2004). Stemming from philology, such literary treatments of hikayats are often based on European genres such as the epic, and elements such as the hero and the interaction between the epic and history. A similar approach is used in Andaya’s (1979) thorough narrative on the history of eighteenth-century Perak as a Malay state, in which Misa Melayu is comparatively analyzed with Malay and Dutch sources. Although “the temptation to force the material into tidy patterns has been resisted,” the hikayat is considered by the historian as “a product of Malay historical method.” There are two key issues here: first, the “Malay historical method” is subject to our understanding of the phrase, inevitably affected by all the connotations and footnotes that come with the English word “historical” such as dates, timelines, important agents—usually those in power—and the overarching presence of trade as the main catalyst of events; and second, the assumption that the text was produced with history in the mind of the author. In this essay, I wish to sidestep European-based historical and literary values that have been tagged on the hikayat and offer the perspective of simply a reader of the story who turns a critical eye on the problems of translation—of words and notions—in its analysis.

To read Misa Melayu is to imagine royal court life in eighteenth-century Perak, a Malay state often dubbed the successor of the traditions of the Malaccan24) and Johor Sultanates. The “talented”25) author Raja Chulan,26) who was an aristocrat, wrote himself into the text. This gives an insider’s perspective on the lives of the Perak elite (orang besar27)): their feuds, marriages, and dealings with the Dutch (Holanda) involving tin and rial Holanda, or Dutch banknotes. A significant portion of the text is a poetic tribute to the sultan’s voyage down the Perak River, while the other parts are intimate and elaborate accounts of festivities and processions. In Winstedt’s words:

Recording the names of contemporary Perak chiefs, and incidents in the relations of Perak with the Dutch and with Selangor and Kedah, and throwing unconsciously a deal of light on the life of a Malay State in the XVIIIth century, the Misa Melayu is one of the more valuable of Malay historical works; and it is surprising that it has not been printed before. The shaer or long poetical recital of Marhum Kahar’s trip down the Perak river and round the coast to Matang has literary as well as historical value. The prose portion of the book, though not equal in style to that Malay masterpiece the Sejarah Melayu, is not lacking in merit. (Raja Chulan 1919)

Other than Misa Melayu, there are several titles associated with the text, such as Hikayat/Ikatan Raja ka-Laut (The Story of the King Going to the Sea), Sultan Iskandar Bermain-main ka-Laut (Sultan Iskandar Journeys to the Sea), Hikayat Misa Melayu (The Story of Misa Melayu), and Hikayat Salasilah Negeri Perak (The Descent/Genealogy of the Perak State). The first two refer to the exquisite syair,28) a Malay poetic arrangement that intertwines meaning and form in ways that make them almost impossible to be incorporated into history.

The version of Misa Melayu used as the primary text for this research is the 1968 reprint of a 1962 edition based on Winstedt’s transliteration of the Jawi text from three manuscripts,29) of which the main one used is dated 1836. It includes Winstedt’s introduction and outline of the content in English from the first edition, as well as their Malay translations and some commentaries by Pustaka Antara, a publishing house in Kuala Lumpur. In all of the auxiliary materials accompanying the text, the historical value of the text is highlighted. Perhaps, ironically, that was the reason why the text had not been given much attention, as it was compared to Sejarah Melayu, a much-quoted seventeenth-century Malay text originally titled Sulalat as-Salatin (The Descent of Rulers) and considered to be, as the translated title The Malay Annals suggests, a canonical source on the history of the Malays. This comparison makes it unsurprising that Winstedt finds it necessary to point out the “merit” of Misa Melayu, as it is being measured against a text that has been elevated to a position of authority over other “historical” classical Malay texts. And from his evaluation of the former, we can see that he still favors Sejarah Melayu by calling it a “Malay masterpiece.” On this matter, the questions I ask are similar to the ones Jacques Derrida (1992) asks about Franz Kafka’s Before the Law: What decides that Misa Melayu belongs to what we think we can understand in the name of “literature” and “history?” And who decides? Who judges?

On one level at least, apparently one answer to the questions above is Winstedt, as his “writings more than anybody else’s set the standard in Malayistics from 1915 onwards” (Maier 1988, 30) and, based on the same criteria that constitute British historical sources, imply that every hikayat deemed historical should be “read against the background of the Sejarah Melayu, and ever since the primacy of the Malay Annals has never been subverted.” Scholarship in Malay studies, until today, continues to accept and to be (mis)guided by such a unilateral imposition of British empiricism on indigenous Malay texts. In this framework, Misa Melayu would undoubtedly be seen as a lesser historical text, just as Perak is generally considered an offshoot state of the Malacca Sultanate rather than having a unique history of its own.

Winstedt’s 11-page English outline—of over 200 pages of poetry and prose, in classical Malay—informs us about which kinds of information were important for him (Raja Chulan 1919). And it is not too difficult to imagine that Raja Chulan could not possibly have had Winstedt’s standards of a “Malay historical text” in mind when he was writing Misa Melayu. I am curious as to what lies beyond Winstedt’s (and many historians’) chronological and linear notion of history in the text and how to get to it in a methodologically sound manner. One way is by reading what has been de-emphasized by historically inclined scholars, or thrown in the background, as is the case for the parts of Misa Melayu that did not make it into Winstedt’s outline. Another way is by simply asking, What would be the intended purpose of Misa Melayu? Perhaps it was to be read by (or to) Sultan Mudzafar Shah, who commissioned Raja Chulan to write it, and maybe some members of the royal family? What would be the reading context of Misa Melayu, and is there an opportunity to peer out of this context, through the text? It is, again, a problem in translation that shrouds this text, as every reading of Misa Melayu would be influenced by our language of history. To overcome the perilous compulsion of a historical reading, a question that I use as a directive would be what is unsaid when Misa Melayu is translated into, or related to, historical discourse:

The stupendous reality that is language cannot be understood unless we begin by observing that speech consists above all in silences. A being who could not renounce saying many things would be incapable of speaking. And each language represents a different equation between manifestations and silences. Each people leaves some things unsaid in order to be able to say others. Because everything would be unsayable. Hence, the immense difficulty of translation: translation is a matter of saying in a language precisely what that language tends to pass over in silence. (Ortega y Gasset 1963, 246)

The quote above might well be a parable of the colonial encounter in the Malay world, where multiple attempts at translation occur after instances of language contact. On the pages of the 1968 Misa Melayu, this contact is exemplified by Winstedt’s supplementary text side by side with Raja Chulan’s narrative, one discourse saying what is silent in the other and vice versa. Underlying this discrepancy is a difference in language and, more important, discursive methods by which concepts such as history, literature, and law are constructed and reinforced. Obviously, these are colossal notions that could be considered systems or frameworks of knowledge, each containing their own interconnecting vast networks of ideas.

This phenomenon would explain the language (and the existence) of treaties, such as the 1874 Pangkor Treaty, a colonial document signed between British administrators and Perak royals—one of many that initiated the British advisorial system in Malaya—that was an exclusive agreement between the two parties, in complete disregard of the consequences of the onset of British imperialism in Malaya. Treaties like these are mainly framed in legalese decided by the British, transferred through the process of translation into Malay, and demand agreement from the Malay royals, rather than vice versa. In a language firmly rooted in the conventions of European nation-states, the Malay voice would be incongruent, saying the unsayable in that language. Although the sovereignty of Malay polities is asserted in some hikayats, including Sulalat as-Salatin and Misa Melayu, it lies buried in the silence of the treaty, undermined by a voice more authoritative, if only for the reason that it decides so itself.

In Misa Melayu, as well as many other hikayats that have been labeled as state histories, negeri is the most ubiquitous self-referential word representing a polity. Parts of it correspond to the European “state,” such as the existence of taxation laws and state revenue. However, its geography consists of humans—rulers and subjects (the latter mostly silent and kept out of the texts)—who were constantly traveling. In a sense, negeri was not bound exclusively to one area of land; instead, it was a mobile political unit comprising the palatial institution and its subjects. This performative aspect of negeri was obscured in the 1874 treaty by oversimplification and ignoring any signs of the existence of a complex and abstract political system that was as elusive as the nation or state. Instead of imposing land-borders marking a geopolitical region, within the literary space of the syair, the sultan is said to be “making a state” on the islands in the Perak River:

| The epoch of Sultan Raja Iskandar | |

| Making a state on Chempaka Island; | |

| Eloknya pekan dengan Bandar, | A fine town with a city center, |

| Tempat dagang datang berniaga | Where the merchants come to trade |

| Membuat negeri di-Pulau Chempaka, | Making a state on Chempaka Island, |

| Di-gelar Pulau Indera Sakti; | Named Indera Sakti Island; |

| Dagang senteri datang berniaga, | [Where] Wandering merchants come to trade, |

| Ka-bawah duli berbuat bakti. | Devoted under the protection of the royal highness. |

| Tuanku Raja Sultan Iskandar, | Tuanku Raja Sultan Iskandar, |

| Takhta di-Pulau Indera Sakti; | Bethroned on Pulau Indera Sakti; |

| Indahnya lagi jangan di-sedar, | Its beauty not to be compared, |

| Kota pun sudah bagai di-hati. | Its fort immortalized in the heart. |

| Takhta di-Pulau Indera Sakti, | Bethroned on Indera Sakti island, |

| Di-sembah tentera sa-isi negeri, | To whom the entire state’s army gives obeisance, |

| Kota pun sudah bagai di-hati, | Its fort immortalized in the heart, |

| Bertambah kebesaran sa-hari-hari. |

Notions of negeri the way it is presently understood would be incongruent with the way the word is used in the syair: the latter presents negeri as a pleasurable, progressive act rather than something that is constative, or already built. Such is the problematic of translating the past into present terms; the mismatch in semantic relations offers us no way of remembering the reality of the state’s past other than looking through the narrow constrictive lens of the present, which does not allow us to escape into the realm of the state’s glorious narrative past, beyond the grids of archetypal symbols—flags, political institutions, geometric maps—that we are more used to in the present. It is anachronistic and misleading, therefore, to understand the word and the concept negeri through present-day sense.

One of the reasons to dive into the margins of a canonized discursive space of Malaysian and/or Perak (a Malay state in the eighteenth century) history and historiography is to take a possible look at the other “data” consigned to the margins by the upholding of linearity, and linearization in the histories of nation-states in Southeast Asia (Yong Mun Cheong 2003, 95). Southeast Asian history can be problematized further by the application of novel literary theories that give rise to a whole new set of questions. For example, in attempts to translate Hikayat Hang Tuah from Malay to English, what tense should be used (Errington 1975)? Seemingly simplistic, this question hinges on the deeper issue of the spectral hegemony of linear time deployed by the episteme “history” in the study of old Malay texts. Much like space, time is assumed to exist in any consciousness as unidirectional and linear by many historians via timeline-based narratives of the past regardless of the absence of any symptomatic signs of its consideration as such. Malay does not have any tense, and specificity in time is often marked by lexical temporal markers; thus, a translation of a Malay text into English automatically imposes the tense system of the latter onto the former, overshadowing any concept of time (or the absence thereof) in the former.

In a similar way that it cultivates inquiry of the upheld notions of historical, literary, social, cognitive, and physical space, Southeast Asian studies’ disciplinary plasticity allows the incursion of a healthy form of skepticism, stemming from literary theory, of the way time was considered in old Malay texts. Narratology, the study of narratives and its structural makeup—essentially a form of close reading—can be an instrument to challenge the assumptions of the “historical” and also therefore the labeling of a text as historical (instead of literary, religious, or otherwise). This form of textual analysis is used by Anthony Milner (2002) in studying the “silences” in the Malay nationalist Ibrahim Yaacob’s record of his speeches, Surveying the Homeland (1941), delving into what he did not say as well as what he did.

To a certain extent, the many analyses and interpretations of the state, as presented by histories written by authors who have read Misa Melayu, have tried to compose a finite picture of Perak. The focal point of this essay, instead of doing the same thing that historians have done, is to critically analyze the features of the historical discourse that forms the narrative. In other words, what is presented in the essay is the information in the outskirts or in and around the edges of history and literature of a Malay state.

Regarding the question of ideology, Misa Melayu predates any institutionally prescribed political understanding as it is understood now, and this is the very reason why I choose to dive into the discursive margins of the text. It is true that the writing of the text has been commissioned by the sultan to the author Raja Chulan, a member of the royal family himself. Thus, the fact that the hikayat was written as an internal response to an authoritative voice cannot be ignored, yet beyond politics the text offers an avenue to understand Malay literary aesthetics, something that is subtle and vague and cannot be totally captured by a historical eye that constantly searches for data, which I find more important to focus on. Another important point to be mentioned here is that Misa Melayu is a combination of many texts and within it many stories, rather than one, and this factors into the reception of Misa Melayu as a historical source, as is the case with the other textual artifacts presented in the essay. All of them are influenced in their production and reception by underlying epistemes, be it “history” and/or “literature” for the texts, or “cartography” and “geography” for the maps. For this reason they should be appreciated critically and not taken at face value.

Misa Melayu may be read as a key text in understanding textualized oral narratives—hikayat and syair—beyond the constraints of the time and space of its contents. To do the text justice is to read it in multiple modes, venturing around it, unlocking doors and opening windows of matrices in/of Perak’s past, present, and future, leading us to understand in an interdisciplinary, performative way how the state was constructed by the powers that be, by way of textual and cartographic maps. By bringing texts, events, and characters around the “cartographic,” “historical,” and/or “literary” text that has been overshadowed by constative reading practices, seemingly set in stone for centuries, we can only gain more by unraveling new paths that map networks of meaning that were previously untrodden. Parallel to serious, excavative, archeological means of reading, we might find other ways of deciphering bits and pieces of sacred knowledge buried in the soothing orality of its language—now silenced by textual modes of knowledge production—by playfully wandering in and around the text, harvesting from our consciousness jigsaw pieces of reimaginings of senses from which a geo-, hydro-, cosmo-cognitive space has been understood, construed, and cyclically produced and revised. Ultimately, of course, in reading the hikayat, the choice lies in the reader’s hands, whether to be bound by the narrow confines of normalized, academicized reading methods or to play freely, sensibly with game pieces from within or without the text, creating novel and deeper comprehensions from the uncharted territories of the reading imagination.

Accepted: September 9, 2014

References

Ammarell, Gene. 1999. Bugis Navigation. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Andaya, Barbara Watson. 2006. Oceans Unbounded: Transversing Asia across “Area Studies.” The Journal of Asian Studies 65: 669–690.

―. 1997. Historicising “Modernity” in Southeast Asia. Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 40(4): 391–409.

―. 1979. Perak: The Abode of Grace: A Study of an Eighteenth Century Malay State. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press.

―. 1975. Perak: The Abode of Grace: A Study of an Eighteenth Century Malay State. PhD dissertation, Cornell University.

Arba’iyah Mohd Noor. 2006. Approaches and Sources in Sejarah Melayu and Misa Melayu. In History, Source dan Approach, edited by Danny Wong Tze-Ken. Kuala Lumpur: Penerbit Universiti Malaya.

Bagrow, Leo. 1985. History of Cartography, translated by D. L. Paisey. 2nd ed. Chicago: Precedent Publishing.

Becker, A. L. 2000. Beyond Translation: Essays toward a Modern Philology. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Bleich, David. 1975. Readings and Feelings: An Introduction to Subjective Criticism. Urbana: National Council of Teachers of English.

Borges, Jorge Luis. 1999. Collected Fictions, translated by Andrew Hurley. New York: Penguin.

Braginsky, V. I. 2007. . . . And Sails the Boat Downstream: Malay Sufi Poems of the Boat. Leiden: Department of Languages and Cultures of Southeast Asia and Oceania, University of Leiden.

―. 1993. The System of Classical Malay Literature. Leiden: KITLV Press.

Braginsky, Vladimir. 2004. The Heritage of Traditional Malay Literature: A Historical Survey of Genres, Writings and Literary Views. Singapore: ISEAS.

Casey, Edward S. 1998. The Fate of Place: A Philosophical History. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Chakrabarty, Dipesh. 2000. Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Chou, Cynthia. 1994. Money, Magic and Fear: Identity and Exchange amongst the Orang Suku Laut (Sea Nomads) and Other Groups of Riau and Batam, Indonesia. PhD dissertation, University of Cambridge.

Cronon, William. 1992. A Place for Stories: Nature, History, and Narrative. The Journal of American History 78(4): 1347–1376.

Culler, Jonathan. 2003. On Deconstruction: Theory and Criticism after Structuralism. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Cycle of the Pirates of Malaysia (Sandokan-Cycle), accessed March 2, 2014, http://www.mompracem.de/?q=en/node/18. 181–220.

Derrida, Jacques. 1992. Acts of Literature, edited by Derek Attridge. New York: Routledge.

Errington, Shelly. 1975. A Study of Genre: Meaning and Form in the Malay Hikayat Hang Tuah. PhD dissertation, Cornell University.

Farish Noor. 2006. A Muslim-Hindu Buddy Story: Raja Shah Mardan and Berahman in the Hikayat Indera Jaya, accessed March 30, 2014, http://www.othermalaysia.org/2006/10/12/012-a-muslim-hindu-buddy-story/.

Ferguson, Niall. 2008. The Ascent of Money: A Financial History of the World. New York: Penguin.

Foucault, Michel. 1972. The Archaeology of Knowledge and the Discourse on Language, translated by A. M. Sheridan Smith. New York: Pantheon Books.

Gullick, J. M. 1989. Malay Society in the Late Nineteenth Century: The Beginnings of Change. Singapore: Oxford University Press.

―. 1988. Indigenous Political Systems of West Malaya. London: The Athlone Press.

Halim, N. A. 1981. Tempat-tempat Bersejarah Perak [Historical sites of Perak]. Kuala Lumpur: Jabatan Muzium.

Harley, J. B.; and Woodward, David. 1994. The History of Cartography: Cartography in the Traditional East and Southeast Asian Societies Vol. 2.2. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Henley, David. 2004. Conflict, Justice and the Stranger-King: Indigenous Roots of Colonial Rule in Indonesia and Elsewhere. Modern Asian Studies 38(1): 85–144.

Hooker, Virginia Matheson. 2003. A Short History of Malaysia: Linking East and West. New South Wales: Allen & Unwin.

Jacobs, Frank. 2009. Strange Maps: An Atlas of Cartographic Curiosities. New York: Penguin.

Koster, Gijsbert Louis. 1993. Roaming through Seductive Gardens: Reading in Malay Narrative. Manuscript, Leiden.

Maier, Hendrik M. J. 2004. We Are Playing Relatives: A Survey of Malay Writing. Leiden: KITLV Press.

―. 2003. Complit and Southeast Asia. In Southeast Asian Studies: Pacific Perspectives, edited by Anthony Reid, pp. 233–253. Tempe: Arizona State University Press.

―. 1988. In the Center of Authority: The Malay Hikayat Merong Mahawangsa. Ithaca: Southeast Asia Program, Cornell University.

Malay Concordance Project, accessed October 21, 2013, http://mcp.anu.edu.au/N/Misa_bib.html.

Matheson, Virginia. 1979. Concepts of Malay Ethos in Indigenous Malay Writings. JSEAS 10(2): 351–371.

Maxwell, W. E. 1974a. Notes on Two Perak Manuscripts. In A History of Perak by R. O. Winstedt and R. J. Wilkinson, pp. 181–191. Kuala Lumpur: MBRAS.

―. 1974b. Shamanism in Perak. In A History of Perak by R. O. Winstedt and R. J. Wilkinson, pp. 216–226. Kuala Lumpur: MBRAS.

―. 1974c. The History of Perak from Native Sources. In A History of Perak by R. O. Winstedt and R. J. Wilkinson, pp. 192–215. Kuala Lumpur: MBRAS.

McNair, Fred. 1878. Perak and the Malays. London: Tinsley Brothers.

Milner, Anthony. 2002. The Invention of Politics in Colonial Malaya. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Monmonier, Mark. 1996. How to Lie with Maps. 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mulyadi, S. W. R. 1983. Hikayat Indraputra: A Malay Romance. Dordrecht: Foris.

Ortega y Gasset, Jose. 1963. Man and People, translated by Willard R. Trask. New York: W.W. Norton.

Phillimore, R. H. 1956. An Early Map of the Malay Peninsula. Imago Mundi 13: 175–179.