Contents>> Vol. 5, No. 1

Very Distinguished Alumni: Thai Political Networking

Pasuk Phongpaichit,* Nualnoi Treerat,** and Chris Baker*

*ผาสุก พงษ์ไพจิตร, based in Bangkok, Thailand

Corresponding author (Baker)’s e-mail: chrispasuk[at]gmail.com

**นวลน้อย ตรีรัตน์, Faculty of Economics, Chulalongkorn University, Pathumwan, Bangkok 10330, Thailand

DOI: doi.org/10.20495/seas.5.1_19

The creation of elite networks can be explicit and deliberate, especially as a strategy to sustain an oligarchic political system. In Thailand, because of rapid economic and social change, there are few of the established, seemingly natural frameworks for networking found in more settled societies. Those hopeful of joining the power elite come from widely differing backgrounds. Paths through education are very fragmented. There are no clubs and associations that can serve as meeting places. Alumni associations have been brought into existence as one major way to meet the demand for a framework for power networking. This particular associational form is familiar and comfortable because it draws on aspects of collegiate life that most of the participants have experienced. The military pioneered this strategy in the 1960s. When the military’s power and prestige waned in the 1990s, several other institutions emerged to fill the gap. One of the most successful was the Stock Exchange of Thailand, which created the Capital Market Academy (CMA) in 2006. CMA offers academic courses, but its main purpose is to create an alumni association that serves as a network hub linking the main centers of power—bureaucracy, military, judiciary, big business, politicians, and select civil society. Such networks are critical to the rent-seeking activity that is one feature of oligarchic politics.

Keywords: Thailand, alumni networks, Capital Market Academy, military, oligarchic politics

The class that assembled for the first time in Bangkok in March 2010 was not an average group of freshmen students. To begin with, there was Banharn Silpa-archa, a former prime minister and 40-year veteran of parliamentary politics who, at age 77, was hardly in the usual catchment for education. Beside him on the school benches were five other former ministers, one of whom had also been commander-in-chief of the army; two other generals; two deputy police chiefs; the head and two deputy heads of major government agencies; and a sprinkling of judges and MPs. In a class of fewer than 100 students, this concentration of the powerful could not have occurred by chance. Nor was this an ancient and prestigious seat of learning. The academy had been founded only five years earlier, and the vast majority of Thailand’s population had never heard of it. It was called the Capital Market Academy (CMA), and its stated aim was to educate people, primarily businessmen, about corporate finance and investment.

Of course, the reason why this school’s benches groaned under the weight of so much power had nothing at all to do with the content of the coursework or the value of the certificate received on graduation. Rather, it had everything to do with networking. These powerful people were here because the others were too. The CMA1) is the latest and most spectacularly successful example of an institutional form that has become uniquely important in Thai politics—a quasi-school that exists primarily to form a network among its alumni.

The relatively low level of institutionalization in Thai public life has been noted many times—from the Cornell anthropologists’ notion of “loose structure” in the 1950s through to Danny Unger’s work on limited social capital in the 1990s (Embree 1950; Unger 1998). The monarchy, military, and bureaucracy are the only organizations with both structure and historical depth. Parliament has been constantly disrupted over the years. With just one exception, political parties are ephemeral. Business associations have only recently acquired more weight. The rapid pace of economic and social change in recent decades has also meant that institution building lags behind social realities. In this situation, the business of forming networks linking different, fragmented nodes of power has become of critical importance. The founding of the CMA can be seen as a deliberate attempt to create a network hub with linkages into several of the dispersed centers of power in Thai society.

This paper examines the rise of the CMA as a window into the arcane background of Thailand’s oligarchical politics. The first section of the paper traces the emergence of the political alumni network over past decades. The remaining sections outline the foundation, rapid rise, and immense influence of the CMA.

I The Development of the Political Alumni Network

The original model for the new political alumni networks came from the alumni associations of major universities. Until the 1960s, most recruits into Thailand’s elite, other than its military component, passed through one or other of the country’s first two universities, Chulalongkorn and Thammasat. Social bonds among students were cemented by hazing rituals, sports, and other campus activities. Alumni associations were formed to preserve these bonds into later life. The resulting networks, particularly those focused on certain faculties (e.g., Chulalongkorn’s Faculty of Political Science), were important in the relatively narrow social and political elite of the time, especially in the bureaucracy.

The military adopted and modified this model. Classmates at the Chulachomklao Military Academy and the Cadet School were encouraged to form strong lateral ties and to preserve these ties through alumni activities in subsequent years. As a result, by the 1980s the class groups of certain years had become players in the internal politics of the military.2)

Changes in the power structure of the country between the 1960s and the 1980s created a demand to extend this network model to embrace newly emerging nodes of power. The absolute dominance of narrow elites in the civilian and military bureaucracy was diminished as new political forces developed. The bureaucracy itself expanded in size and complexity, particularly with the addition of new technocratic functions. Business groups became richer and more politically established. Provincial centers rose in importance, and their business elites were drawn into national society by improved communications. Parliament and electoral politics emerged as a tentative forum for some of these new forces.

The alumni networks of the old educational institutions gradually became less effective as means to build links among people who mattered. Many of the luminaries of the emerging business world were unable to gain admission to the old universities. Instead, they were trained in new government universities or rising numbers of private universities, with Assumption Business Administration College being especially favored. Often they went overseas, especially to the United States, for the final stages of their education. New provincial leaders often rose through universities in the provinces. Several new alumni networks emerged, particularly focused on Assumption Business Administration College, Ramkhamhaeng Open University, and informal groupings among graduates from favored US locations such as Boston—but overall the trend was toward fragmentation.

Against this background, in 1989 the military made a key innovation: founding a quasi-academic body with a major and perhaps preeminent purpose of building a wider form of the networks associated with alumni.

Earlier, in 1955, the military had founded the National Security Academy (Witthayalai Pongkan Tatcha-anajak, Wo Po Or) to give short-course training to civilians in order to instill in their minds the importance of national security and the role of the military. Students included both military officers and outsiders, mainly civilian bureaucrats. Besides its role as a propaganda vehicle for the military, this institution gradually became important for building informal links out from the military into newly important social groups. In 1989 the military created a new institution to accelerate the development of this networking, the National Security Academy for Government and Private Sector (Po Ro Or). At the time, the military’s role in the polity was coming under increasing attack from business quarters. A burning issue was complaints that the military budget was eating into the regular annual budgets, which should have been used for projects to support industries and other businesses. Po Ro Or primarily recruited students from business and other civil society groups. In 2003, it launched an extra program specifically targeted at politicians.3)

At these National Security Academies, the educational content was less important than the active encouragement of bonding and networking. Much classwork was in groups. Students made many trips and visits, both within Thailand and overseas, which offered long periods for socialization. Contact in the classroom was supplemented on the golf course and in exclusive clubs and karaoke parlors. Bonds formed during the course were sustained by an active round of alumni activities. Most important, these academies actively inculcated the military culture of unconditional commitment to help colleagues in every possible way. Refusing a request from an old classmate would be bad form.

The National Security Academies were initially highly successful. Many of the most prominent businessmen of the era joined the classes. So, too, did many highfliers in the civilian bureaucracy and some select members of the media and civil society. The resulting links were vital in bridging the gaps between military, civilian, business, and professional groups. For two decades, there was scarcely a major figure in Thai public life (outside royalty) that had not attended one of these programs.

After the political crisis of 1991–92,4) however, the prestige of the military was badly damaged and its role in national politics sharply reduced. The attraction of the National Security Academies consequently declined, though not immediately or completely, because their function in network building to some extent existed quite apart from any association with the military. This gradual decline created a demand for further innovation in this area of network formation.

At least three new institutions were launched in the same tradition. Each was ostensibly designed to promote public education. All became important as sites of alumni networking, but one much more spectacularly than the others.

The King Prajadhiphok Institute was founded in the wake of the 1991–92 political crisis with the aim of promoting democracy through research and educational activities among the public at large and among politicians themselves.5) The institute launched short courses, with students including MPs along with officials, businessmen, and members of civil society groups.

In 1997, the judicial establishment launched its own academy with the twin aims of educating judicial personnel about society and educating the public about the working of the judiciary. It also adopted the format of short courses, with a mixture of judicial personnel along with senior officials and others. By 2010, some 627 people had graduated from its courses.

II The Rise of the CMA

The Capital Market Academy (CMA) was founded in 2005 by the board of the Stock Exchange of Thailand (SET). The impetus for this move came from a survey commissioned by SET in 2002 to discover why the exchange, after an initial spurt of growth, had tended to stagnate, attracting little new interest or money from domestic sources. Around that time there were several scandals involving insider trading and stock churning. These scandals affected SET’s reputation and made it difficult for the exchange to win support, either in government circles or among the general public, for any innovation. The survey found that people did not invest in the exchange because they did not understand how it worked, believed it to be complicated and non-transparent, and thought it required insider information for success.6) As a result of the survey, SET launched a slew of activities, including the establishment of a library, regular television programming, publications for students, and regular seminars. It also established CMA with the aim “to create a new frontier in top-executives programs, as its course blends knowledge in the capital market with leadership and ethics. It is aimed at developing top-quality leaders who will play a key role in the Thai capital market.”7) SET believed that a training program that brought together members of the private sector, both inside and outside the capital market, along with figures from government, military, police, judiciary, media, academia, and NGOs, would create a better understanding about the roles of SET: “If these people see the importance of the SET for the Thai economy, then they will try to nurture and protect it. They will also facilitate policy changes.”8)

CMA’s “leadership training program” consists of lectures, seminars, case studies, discussions, and study trips. Participants take 60 hours of coursework, attending classes three times a week over a period of four months. There are also trips, seminars, and other activities. The course is divided under three headings: knowledge about the capital market, 50 percent; corporate governance, 25 percent; and leadership roles and social responsibility, 25 percent. The content is largely technical, and the sessions are led by experts in the field. Participants have to present a final project paper in order to qualify for a certificate of achievement. The course is free, though participants have to pay for meals and the expenses of study tours. CMA offers the course twice a year.

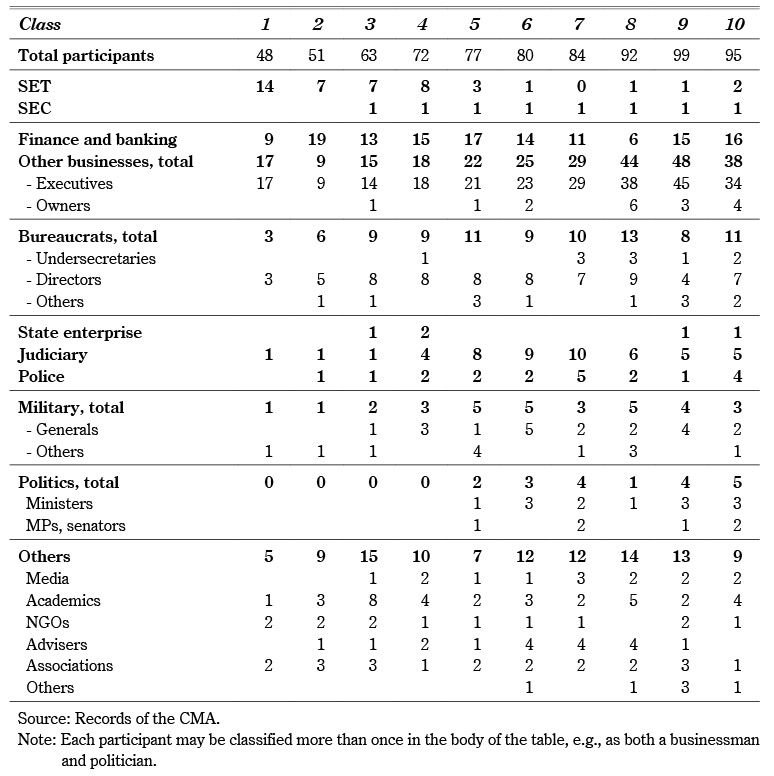

At first CMA targeted the course rather narrowly at mid-career business executives involved in the financial markets and equivalent personnel in government departments dealing with economic and financial policies, plus a few from media and civil society (see Table 1). CMA recruited by sending invitations to relevant companies (financial firms, listed companies, companies with potential to be listed) and government departments, allowing the company or department to choose the participants. CMA also specifically excluded politicians. It was soon realized that this process failed to ensure that participants were the appropriate people involved in policy making. In addition, some politicians lobbied to be invited.

Table 1 Participants in CMA Classes 1 to 10 (2005–10)

Thus, from the fourth cohort, in late 2006, CMA shifted its targeting upward to senior people thought to be relevant to policy making or opinion formation, and began directly inviting individuals rather than leaving the choice up to a company or government department. Civilian officials had to be of director level or above, except in the case of officials from the Ministry of Finance, where the bar was lowered slightly in view of the ministry’s importance for the financial market. Invitees from business had to be owners or high-level executives. In addition to these two main groups, SET also began to invite key figures from the public sphere, including MPs, senators, ministers, and public figures considered to be important as role models and opinion leaders.9) Initially the upper age limit for participants had been set at 50, but after this change of policy the average age rose to 55. In each course, SET deliberately contrived to have a mix of participants—some politicians, some judiciary, some military, some civilians, some leading business executives or owners, some upcoming stars.

With this shift in recruitment policy, CMA had the potential to become an important new center for networking. The popularity of the course rapidly rose. At first, each class had been limited to 50 participants, but demand was so strong that the limit was gradually expanded to 100. By 2010, CMA had a backlog of more than 700 applicants wanting to attend the course.

Significantly, many attending the course were already experienced at this form of networking. Of the total of 771 attendees up to early 2010, 364 had already attended the National Security Academy.

III From Training School to Networking Center

As with other such courses, the importance of CMA as a locus of network formation was present from the beginning, but it expanded markedly when SET broadened the catchment area beyond the financial industry to a more elite level.

The organization of the courses seems designed to promote CMA’s network function at least as much as its education. The coursework is conducted three times a week in a SET-owned building, conveniently situated next to a prestigious golf course in Bangkok’s inner suburbs. Many participants make a day (and night) of it by playing a round of golf with classmates in the morning, capping that with a sociable lunch, proceeding from class to a group dinner, and continuing for karaoke until late in the night. Each class also has several short trips and at least one (optional) overseas tour of 7 to 10 days (for example, to see the stock exchanges in New York and Tokyo), providing opportunities for extended socialization. These extracurricular activities ensure that participants are able to build strong personal relationships within the four-month period of the course.

As proof of CMA’s rapid emergence as a center of elite networking, an alumni organization was brought into being in 2007 after the completion of only five classes. Members of all five cohorts combined to found the Association of Capital Market Academy Alumni with the stated aim to “create network of relations which will be useful for activities in the name of participants, and as a center to get students together to work for the benefits of the society, and to support economic development and the capital market of the country.”10) Emphasizing the key role of networking, this association adopted as its motto “Synergizing Knowledge, Vision, and Leadership.” The alumni organization was soon involved in an anti-drug campaign, a youth leadership program, a project to combat global warming, environmental activism, charity works, and public seminars—besides a program of social activities and sports events to sustain the bonds created during the four-month course over many years to come.11)

The crest of CMA, proposed by the alumni association, is a unity symbol signifying cooperation, surrounded by a blooming lotus with eight petals, encircled by double rings signifying strength, endurance, knowledge, morality, and ethics (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1Crest and Logo of the Capital Market Academy

CMA made some key innovations in the institutional model borrowed from the military academies. Perhaps the most striking is in the form of address among classmates and alumni. In usual Thai practice, people address one another with pronouns that reflect relative age or seniority. The senior is addressed as phi, or elder brother/sister, and the junior as nong, or younger brother/sister. In CMA, everybody addresses everyone else as phi, even in cases where the difference in age and seniority is obvious and marked. Individuals sometimes use this strategy in situations where they are careful to avoid giving offense. But in this case, the universal practice is clearly part of an attempt to reduce the social distance between participants who come from rather varied backgrounds, and thus to simplify and encourage the building of mutual relationships. One graduate, who had initially found it strange being addressed as phi by a retired general over 20 years his senior, remarked: “This is to show respect, by way of avoiding the actual hierarchy, making everybody horizontal.”

As is traditional among university alumni, classes also stage the kind of clowning around that breaks down barriers. One graduate recalled:

Mr. . . . [A deputy prime minister, in his 60s] was asked to dress as a woman and dance for everyone to see on the stage. He did it. Once you are in the same class, whatever you are asked to do, you have to do it. It’s like rabop run [the classmate system at a university or military academy].

CMA also fosters practices to increase contact between members of different classes. Each class member is given a running number and is expected to act as a godfather/godmother to the person with the same number in the next class. In addition, alumni of all preceding classes are invited to appear at welcoming ceremonies for each new class and other key events, such as regular dinner talks. Whereas classes from military academies sometimes become competitors in military and national politics, CMA actively encourages vertical links between classes, as well as horizontal ties among each class’s members.

IV The Ties That Bind

Some graduates of CMA genuinely appreciate the opportunity to learn about the operation of the capital market within a short span of time. A few are exceptionally enthusiastic. According to other class members, one MP and former minister “asked so many questions, taking up the time of other people.” But generally speaking, most graduates see the major benefits of attending CMA to be the number, variety, and quality of the links that they are able to establish in such a short span of time. One reported:

As for learning, it may be better to spend time reading for yourself. But from the social perspective, the program is wonderful. It’s good for building connections for information and support. It helps widen the worldview. People do think differently. Many people have conflicting views. But this is a chance to talk and exchange opinions. Many of the class members have achieved something in their fields. When they study together in the same class, the conflict is not sharp. Whatever happens, we are still the same class. People avoid extreme views. There are people who are very Yellow, while others are very Red. But they do not show their true colors. The ties that bind are mutual interests.12)

These links are especially important to business participants, but they are important also to others, including politicians and journalists:

Businesspeople benefit in the long run. Meeting politicians such as ministers gives them connections. When someone from their class is in government, they have connections to some extent, creating opportunities for future deals. Politicians also want to connect to businesses. They were the ones who pushed SET to let them in as participants.

For a columnist who writes regularly for a newspaper, businessmen give him business clues and news. There are so many people from the financial world. One of my younger class attendees is a deputy manager in Krung Thai Bank.

My class elder with the same running number is an ex-minister. He talked to me and helped all the time. I can ring him any time. This is a new connection I got from attending CMA. I was also invited to give some lessons in CMA later, after I graduated. If I had not attended, I would not have had these opportunities.

I need some funds for scholarships for my students. I asked for donations from some of the big business people I met. They were helpful.13)

Within the short span of five years after its foundation, CMA was seen to have an important function within the elites of power and money. A member of the CMA alumni said:

CMA is now a force to be reckoned with. It will effect economic changes in Thailand. It is an economic elite with ties to bureaucracy, and now politicians. It is not an ordinary network.

A CMA instructor summarized:

People want endless connections. CMA has become a place for people of diverse backgrounds to meet and make deals. Undersecretaries and directors from budgetary offices, judiciary, forestry, revenue, excise, members of state enterprise boards—they are all very useful connections.

V Politicians

The founders of CMA were initially reluctant to admit politicians to the courses, choosing instead to limit recruitment to people directly involved in the capital market. However, from early on, some politicians lobbied for CMA to change this policy and admit them. After CMA agreed, Class 5 (the fifth cohort) in late 2007 was the first to admit politicians, including a long-standing Democrat MP and another prominent MP and newspaper columnist.14)

Class 6 in early 2008 admitted several ministers and ex-ministers along with political advisers, leading businessmen, and five army generals.15) The political atmosphere at the time was rather tense. In late 2006, the army had overthrown the government of Thaksin Shinawatra in a coup. In December 2007, parliamentary rule was restored through a general election. Prior to this election, the army invested large sums of public money to prevent the return of a government loyal to Thaksin. As part of this effort, the coup generals had established new political parties and lured former pro-Thaksin MPs to join them. The most important of these parties was Phuea Phaendin. At the December 2007 polls, however, these parties performed poorly, and the pro-Thaksin People Power Party (PPP) ended up heading a new government. The Phuea Phaendin Party became a minority partner in the coalition (Pasuk and Baker 2010). Maneuvers to influence the loyalty of individual politicians continued. One member of CMA Class 6 was an MP of the pro-Thaksin PPP. He persuaded two other members of the class to publicly join the PPP. One of these was a Phuea Phaendin MP and deputy minister of finance. The other was a general who had been deputy army chief and head of the Third Army during the coup.16)

The incident was widely reported and attracted a lot of comment. It cemented the reputation of CMA as a key center for networking. While the majority of participants in CMA were still drawn from finance-related businesses, later classes included more people from various centers of power. In Class 7, for the first time the participants included bureaucrats of undersecretary level, and in total nine attended over the next four classes. From Class 5 onward, each cohort averaged five generals, seven people from the judiciary, three from the police, and three from politics. Although the numbers from politics were relatively few, the stature of those few lent CMA a certain luster. Class 10 included former Prime Minister Banharn Silpa-archa along with a former acting prime minister, a former deputy prime minister, three other former ministers (one also a former army chief), and a veteran Democrat MP.17) They shared the class benches with two deputy police chiefs, two more generals, a deputy attorney general, the secretary-general of the Board of Investment, and a deputy director of the Revenue Department.

VI Influence in Financial Policy

In late 2007, one member of CMA Class 5 wrote a research report titled “Development of the Thai Capital Market: Importance and Approach.” The report discussed the problem of the Thai capital market at the time, particularly after the central bank had imposed a controversial reserve requirement to discourage short-term capital inflow. Minister of Finance Surapong Suebwonglee18) was invited to attend a discussion on the report, during which a suggestion was put forward to set up a committee on the development of the capital market. The minister agreed and promptly got Cabinet approval. In March 2008, the committee was constituted with 23 members from government departments and the private sector. Five of the members were CMA alumni, proposed by CMA.19)

Although there had been much comment on the need to develop the Thai capital market in recent years, nothing concrete had resulted. However, this new committee was able to gain cooperation from many government agencies and come up with unusually wide-ranging proposals in a very short time. The Board of Investment agreed to adjust promotional policies to favor listed companies. The Ministry of Commerce agreed to amend regulations that obstructed listing. The Revenue Department agreed to discuss tax breaks for listed companies. The office overseeing state enterprises was open to proposals for facilitating the listing of more state-linked enterprises. Officers of the stock exchange were very pleased by this result and attributed it in large part to the network links of CMA alumni. Many involved in the process were CMA alumni. Others hoped to attend CMA in the future. A SET official commented, “For small things, now there is no need for calling a meeting. We can ring one another to explain the issues.”20)

One result of this process was the four-year Plan for Development of the Thai Capital Market (2010–13), submitted to the Ministry of Finance.21) The plan proposed tax reforms to promote share dealing, the development of more financial products to stimulate investment by the public, the development of bond and derivatives markets, and the promotion of long-term savings. The centerpiece of the plan was a proposal to privatize the Stock Exchange of Thailand.

SET is effectively a state agency, governed by an act of parliament, founded with capital from a state finance company. The plan argued that SET was a monopoly, with all the attendant inefficiency, and that privatization was a key strategy for making the capital market more efficient. Not everybody in the financial industry concurred with this view. Some saw the privatization move as an outrageous example of insider trading. One financial executive commented, “Now SET wants to privatize. There is a need to prepare those involved for this change. The people who will be responsible for this privatization are now all involved with SET, either as personnel or as alumni. As all the people who are involved in the process are now in the CMA, so they are all in accord.”

Following on from the four-year plan, legislation for demutualization of the stock market was drafted under the Democrat Party-led government (2009–11) and sent for scrutiny by the Council of State. After the Democrat Party was defeated at elections in 2011, the bill was withdrawn. Disagreement over the legislation focused especially on the fate of the 15-billion baht fund for the development of the capital market, part of which was raised as a levy on the fee income of the member companies in the exchange. Under the reform legislation, the fund would be separated from the exchange and constituted as a non-profit juristic person. The member companies, and the government installed in 2011, feared that the fund would be misused. The finance minister also feared that the reforms would transform the stock exchange from a non-profit organization into a business that would fall under the control of a small group of investors, resulting not in greater efficiency but in more conflict of interest. In other words, in the view of opponents, the stock market reform plan that emerged from CMA was an ambitious attempt to alter the distribution of interests and benefits from the stock market.

Conclusion

Thailand’s Capital Market Academy is a new institution. The qualifications that it bestows on its students are of minimal value. Yet the academy has a star-studded student body and a waiting list as long as its total enrollment over its five years of existence. People now have to politick and pull strings to gain admission.

The fact that the CMA alumni network has been created out of nowhere is a function of demand—and of a special kind of demand that exists in the oligarchic style of politics found in Thailand and many similar countries. The military, parliament, various segments of business, and various sections of the bureaucracy have their own internal power networks. However, in the increasingly complex political society that has developed in recent decades, a network of links across a variety of key institutions is a prerequisite of power. Because of rapid economic and social change, there are few of the established, seemingly natural frameworks for networking found in more settled societies (alumni associations of select schools and universities, elite social and sports clubs, interlocking directorships, etc.). Those hopeful of joining the power elite come from widely differing backgrounds. Paths through education are very fragmented. There are almost no clubs and associations that can serve as meeting places.

Alumni associations have been brought into existence to serve as hubs in networks that span across the power centers of society. The particular associational form of an alumni network is familiar and comfortable because it draws on aspects of collegiate life that most of the participants have experienced. The military must be credited with elaborating this form into something more useful for political networking. From the 1960s to the 1990s, anybody who wanted to be somebody attended a course at the National Security Academy.

Two key features of the National Security Academy courses were tailored to the needs of network formation in an oligarchic polity. First, the recruits were drawn from a range of power centers—military, police, business, bureaucracy, banking, judiciary, and politics. Second, admission was exclusive; students were handpicked.

The political crisis of 1991–92 damaged the prestige of the military, yet its academy continued to attract the would-be powerful. More important, the political sphere became much more complex with the growing wealth of business, increased importance of parliament, and new significance of the judiciary. The fact that CMA so quickly became the framework for a new business-political alumni network indicates a demand for something similar to the National Security Academy yet not so closely associated with the military.

The fact that this new network was connected to the stock exchange and the capital market is clearly significant. Similar academies founded by the judiciary and the political establishment (through the King Prajadhiphok Institute) have been much less successful than CMA. This seems to indicate the primary role of business in the Thai oligarchy of power.

Lastly, such networks are critical to the rent-seeking activity that is one feature of oligarchic politics. The proposed privatization of the stock exchange, planned by CMA alumni, is probably yet another scheme to convert public assets into private capital.

Accepted: January 21, 2016

References

Embree, John F. 1950. Thailand: A Loosely Structured Social System. American Anthropologist 52(2): 181–193.

Nualnoi Treerat; and Phakphum Wanitchaka. 2010. A Mapping of Macro Power Structure: A Case Study of High-Level Training Short Courses. Second progress report for the research project on “Towards a Fairer Thai Society” under the Distinguished Professor Project, funded by the Thailand Research Fund, Chulalongkorn University, and the Office of Higher Education, presented at the workshop on March 16, 2010, Faculty of Economics, Chulalongkorn University.

Pasuk Phongpaichit; and Baker, Chris. 2010. The Mask-Play Election: Generals, Politicians, and Voters at Thailand’s 2007 Poll. ARI working papers series No. 144, http://www.ari.nus.edu.sg/publication_details.asp?pubtypeid=WP&pubid=1667, accessed March 1, 2011.

Stock Exchange of Thailand. 2010. List of Students for the Capital Market Academy Class 10. March–July.

―. 2009. Handbook for the Capital Market Academy, Class 9, September–December.

Unger, Danny. 1998. Building Social Capital in Thailand: Fibers, Finance and Infrastructure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Interviews

Participant S, March 1, 2010.

Participant K, March 7, 2010.

Vice Chairperson V. SET, March 10, 2010.

1) In Thai, Sathaban Withayakan Talat Thun. CMA’s Web site is www.cma.in.th, accessed January 19, 2016.

2) Most famously, Class 5 of the Military Academy was responsible for the coup of 1988.

3) This program was closed in 2007 in response to criticism that it unduly enhanced military interference in politics.

4) The army took power in a coup but was later forced from power by street demonstrations and was greatly reviled for the killing of many demonstrators.

5) The idea of forming such an institute was mooted in 1993 and brought to fruition in 1998. On the structure and aims of KPI, see www.kpi.ac.th, accessed January 19, 2016.

6) Vichet Tantiwanit, deputy chairman of CMA, interview, March 10, 2010.

7) SET President Kittirat Na Ranong, speaking at the inauguration of CMA’s first leadership program on September 3, 2005 (http://www.newswit.com/enews/2005-09-051527-thailand-capital-market-academy-debut-its-leadership-program, accessed June 4, 2012).

8) SET executive, interview, March 10, 2010.

9) In 2007 the head of the Stock Exchange Commission (SEC), the body regulating SET, attended the course, and thereafter a senior figure from SEC was regularly invited.

10) (Stock Exchange of Thailand 2009, 51)

11) Activities included the following: support for the “business for society” program of the Population and Community Association (Mechai Viravaidya); Special Olympics (sports for special persons); anti-drug campaigns in the three southern provinces; a youth leadership project in a village in Amphoe Nang Rong, Buriram; an energy-saving project via a green school room at Yupparat College, Chiang Mai; a global warming reduction project with the Electricity Generating Authority in Chiang Mai; supporting sports equipment for youngsters in Nakhon Ratchasima; supporting a wastewater treatment plant and biogas pit at a school in Chiang Rai; warm blanket projects for 11 remote schools in Chiang Rai; seminars for public knowledge.

12) Interview with an academic member of CMA Class 6. As noted by this observer, such elite networking has existed in parallel with, but separate from, the color-coded street politics of recent years.

13) Interview with a member of CMA Class 8.

14) Suphatra Masdit and Nitiphum Nawarat.

15) These included Chawarat Chanveerakul, head of a major construction firm and later deputy prime minister; Suwit Khunkitti, former minister; Panpree Phahitthanukon, nephew of former Prime Minister Chatichai Chunhavan and adviser to the deputy prime minister in 2008; and Phichai Naripthaphan, deputy minister of finance in 2008. Several army generals were invited, namely, General Somjet Bunthanom, chairman of the advisory group of the Ministry of Defense; General Theerawat Buyapradap, deputy army chief; General Jiradet Kotcharat, deputy army chief; and General Chainarong Nunphakdi, chairman of the executive board, Nawanakorn company.

16) Panpree Mahitthanukon, an adviser to the prime minister, persuaded Phichai Naripthaphan, deputy minister of finance under the Phuea Phandin Party, and General Jiradet Khotcharat, deputy army chief and head of the Third Army during the coup government in 2006–07, to move to the PPP.

17) Police General Chidchai Wannasathit, acting prime minister, April–May 2006; Surapong Suebwonglee, deputy prime minister and minister of finance, 2008; Somsak Prisanananthakul, minister of agriculture and agricultural cooperatives, 2008; Worathep Rattanakorn, minister of finance in the Thaksin government; General Chettha Thanajaro, minister of science, later of defense, 2003–04; Ong-at Klampaiboon, Democrat MP.

18) His wife, Pranee, attended the next CMA class (7).

19) The committee included directors of the Commerce and Business Promotion and Revenue Departments, the governor of the Bank of Thailand, the secretary-general of the National Economic and Social Development Board (NESDB), the chairperson of the Thai Banking Association, the secretary-general of the civil service pension funds, the secretary-general of SET, etc.

20) Vichet Tantiwanit, interview, March 10, 2010.

21) These proposals were still on the table in 2015, awaiting government approval and legislation.