Contents>> Vol. 6, No. 1

Volunteers from the Periphery (Case Studies of Survivors of the Lapindo Mudflow and Stren Kali, Surabaya, Forced Eviction)

Cornelis Lay*

* Department of Politics and Government, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Gadjah Mada University, BA Building Fourth Floor, Room 410, Sosio Yustisia Street, Bulaksumur, Yogyakarta, 55281, Indonesia

e-mail: cornelislay[at]yahoo.com; conny[at]ugm.ac.id

DOI: doi.org/10.20495/seas.6.1_31

This article discusses volunteer movements active during the Indonesian presidential election of 2014, with a focus on volunteers in two troubled regions. The first group of volunteers consists of survivors of the Lapindo mudflow disaster in Sidoarjo, East Java, who are united in Korban Lapindo Menggugat (KLM, Victims of Lapindo Accuse); while the second consists of residents of Stren Kali, Surabaya, who were forcibly evicted and later united through Paguyuban Warga Stren Kali Surabaya (PWSS, Association of Residents of Stren Kali Surabaya). This article attempts to answer two questions: first, how did KLM and PWSS transform themselves into volunteer movements in support of Jokowi? And, second, what actions were taken by KLM and PWSS in support of Jokowi?

The transformation of KLM and PWSS into volunteer movements was intended to resolve issues that the groups had already faced for several years. Their acts were self-serving ones, albeit not based in individual economic interests but rather collective political ones. They were instrumentalist, negotiating an exchange of their support for Jokowi’s assistance in resolving their groups’ issues. Jokowi was supported because he offered a victory through which the groups’ issues could be resolved. Furthermore, these groups’ actions were to meet concrete short-term goals.

Keywords: volunteers, volunteerism in the 2014 Indonesian election, Korban Lapindo Menggugat, Paguyuban Warga Stren Kali Surabaya, rapping, Coins for Change, political contracts

I Introduction

One of the most prominent phenomena during the 2014 Indonesian presidential election was the massive role of volunteers—both individuals and groups—in organizing and consolidating support for the presidential candidate Joko Widodo, better known by the nickname Jokowi. Such volunteerism is not unprecedented in Indonesia.1) The rise of this phenomenon in Indonesia cannot be separated from the Reformasi (Reform) movement of 1998, which opened political space for mass public participation. The explosive growth of public participation in the early phases of Reformasi was followed by a dramatic increase in the number of civil society organizations (CSOs),2) spread of CSO coverage (PLOD 2006),3) and CSO influence and political leverage (Cornelis 2010).

Nevertheless, this phenomenon still raises important questions, particularly considering the following two factors. First, it occurred during a period of increased public dissatisfaction with politics, in which various democratic institutions—particularly political parties and parliament—were perceived as having performed poorly.4) Second, compared to previous volunteer movements in Indonesia, a greater depth and breadth of spectrum was covered by the movements supporting Jokowi. These volunteer movements were spread throughout Indonesia, in both urban and rural areas. They crossed class boundaries as well as religious and political-ideological lines. They knew no age boundaries and included persons of all fields, from cultural critics to farmers. Furthermore, these movements were gender-blind.5)

This article is not intended to discuss all of the phenomena mentioned above. It is, instead, limited to two volunteer movements that emerged in regions facing social turmoil. The first is Korban Lapindo Menggugat (KLM, Victims of Lapindo Accuse), which consists of survivors of the Lapindo mudflow in Sidoarjo, East Java. The second is Paguyuban Warga Stren Kali Surabaya (PWSS, Association of Residents of Stren Kali Surabaya), which consists of survivors of the forced eviction of riverbank settlements in Stren Kali, Surabaya, East Java.

This article stems from research commenced by the writer in November 2014, shortly after the inauguration of the elected president, Jokowi. This research was conducted in two regions in East Java: the area affected by the Sidoarjo mudflow, in Sidoarjo District, East Java; and in Stren Kali, an enclave of Surabaya’s poor residents along the banks of the Jagir River, which has faced forced eviction. Research was conducted over a period of four months, from November 2014 to February 2015; this included four weeks of field research.

The article explores the backgrounds of KLM and PWSS, how they transformed themselves into support movements for Jokowi, and their activities as volunteers for Jokowi. This article is divided into six sections. The first section is introduction. The second section gives a short overview of the concept of volunteer movements at a practical and theoretical level. The third section provides a summary of the history of the Lapindo mudflow disaster and the fourth section discusses the land issues in Stren Kali—the issues behind the formation of KLM and PWSS, respectively. The fifth section discusses the transformation of KLM and PWSS from advocacy movements to pro-Jokowi volunteer movements, as well as their activities in their respective regions. The sixth section is conclusion.

II Volunteer Movements: An Overview

Volunteering is a freely chosen action done to promote the public interest. Motives for volunteering tend to be romantic, idealistic, and altruistic (Mowen and Sujan 2005). The presence of volunteers in politics is related to an abstract idea of volunteerism that Sidney Verba, Kay Schlozman, and Henry Brady (1995) classify as a civic participation model of public involvement. They draw on the classic book by Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America (2000), which connects successful democratic practice with a high level of voluntary participation, defined as “public association in civil life.”

The transformation of volunteerism from a general act to a political one, particularly individual campaigns for public office, is a recent development. Volunteer support for Barack Obama in his campaign for the 2008 presidential election in the United States—which was repeated in the 2012 election and drew more than 2.2 million people (Han and McKinna 2015)—spearheaded the rise of planned, mass-scale volunteerism in politics. Obama’s success transformed the way in which volunteers were viewed: people who had previously been considered burdens came to be viewed as assets. In subsequent years, political volunteerism continued to develop and spread worldwide. In the 2014 South African election, all parties involved volunteers. Volunteers for the Democratic Alliance, for instance, conducted intensive door-to-door campaigns and remained involved during voting (Brand South Africa 2014). During the final weeks of the Canadian federal election in May 2015, 3,500 volunteers from the Liberal Party conducted door-to-door campaigning and reached no fewer than 200,000 potential voters. These were pioneers of a modern campaigning style that combined traditional face-to-face communications with recent data. Volunteers equipped themselves with smartphones or tablets on which they had installed the MiniVAN application, which provided information on potential voters (Bryden 2015). Significant volunteerism was recorded also in the Ukrainian election of 2015, albeit with a different motive: in Odessa, for instance, many volunteers were paid (Holmov 2015).6) Some, however, remained unpaid, including such professionals as lawyers, accountants, and IT experts.

III The Roots of Volunteerism in Sidoarjo: Advocacy for the Mudflow Disaster

On May 29, 2006, hot mud began to spew from the Banjar Panji-1 Well, owned by PT Lapindo Brantas, an oil and gas exploration company formed as a joint venture of PT Energi Mega Persada (50 percent), PT Medco Energi (32 percent), and Santos Australia (18 percent); the Bakrie family7) maintains control over the company (Liauw 2012). Hot mud from the well, which was located in Renokenongo Village, Porong District, Sidoarjo Regency, East Java, soon covered several regions; it continues to flow today. This disaster led to debate over its characteristics. One view was that the mudflow was man-made (Davies 2007).8) Some holders of this perspective argued that it was an industrial disaster (Bosman 2009; 2012; 2013; Bosman and Paring 2010),9) while others described it as an “ecological and social disaster” (Drake 2008; 2012; 2013; 2015).10) Some held that this was a complex issue that required comprehensive and detailed disaster management. Others, however, held that the mudflow was natural (Mazzini et al. 2007),11) and as such understanding and management of the disaster was simpler and resolvable at a technocratic level. As can be expected, it was difficult to find a middle ground between these views, each of which was supported by subjective interests.

The government came up with an ambiguous compromise for policymaking purposes: the disaster was both man-made and natural, having been caused by human actions and natural phenomena. This compromise influenced the ambivalent policies taken by the government several months later. Lapindo Brantas was required to provide compensation to the direct victims of the mudflow, with the government responsible for regions subsequently affected by the disaster. This ambivalence was reflected also in the government institution that was tasked with managing the disaster: the names of the team and agency established indicated that the disaster was natural, but there were also strong indications that Lapindo Brantas was responsible.

The government’s immediate response to the mudflow was to establish a team—the Tim Nasional Penanggulangan Semburan Lumpur di Sidoarjo (National Team for the Management of the Sidoarjo Mudflow)—through Presidential Decree Number 13 of 2006, dated September 8, 2006. This team was given a mandate for six months, which was later extended through Presidential Decree Number 5 of 2007. By the end of 2006 the mudflow was spewing 148,000 cubic meters of mud per day, and due to the continued and spreading impact in the first three months of 2007, the government converted the team’s status into a stronger formal institution, an “agency,” through Presidential Regulation 14 of 2007 regarding the Badan Penanggulangan Lumpur Sidoarjo (BPLS, Sidoarjo Mudflow Management Agency), dated April 8, 2007. This agency was given a broader mandate: it was to, among other things, take steps to coordinate the management of the mud’s eruption and flow, to rescue the area’s residents, to handle societal issues, and to maintain the infrastructure affected by the mudflow, while ensuring that Lapindo Brantas took responsibility for the management of social and community issues in the areas included in the Map of Affected Areas (MAA).

The initial MAA indicated that in 2007 residents of at least 12 villages spread through three districts and covering an area of 640 hectares were affected. In 2011, the MAA was extended with the addition of nine new rukun tetangga (RT)—sub-village governance units. It was again extended in early 2012, with the addition of a further 65 RTs. By 2012, a total of 11,881 families had become victims of the Lapindo mudflow (Kompas 2012a).

Two different schemes were used for compensation. Residents whose land and buildings had been covered by mud and were included on the MAA of March 22, 2007 were the responsibility of Lapindo Brantas, and as such the company was to pay compensation to them. Victims whose land was not included on the MAA of March 22, 2007 but was affected by the mudflow were compensated by the government through the national budget.12) According to Article 15, Paragraphs 1 and 2, of Presidential Regulation 14 of 2007, victims whose land was covered by the first MAA were to be offered an incremental compensation plan upon proof of landownership in the form of a land sale certificate validated by the government. Twenty percent of compensation was to be paid up front, with the remainder to be paid within two years. Victims outside the first MAA, meanwhile, were to be paid in installments over a period of five years.13) By 2014, all victims of the mudflow whose land was not located on the MAA of March 22, 2007 (covering 555 hectares) had received compensation totaling more than Rp.4 trillion (Detik 2014). A very different fate, however, was faced by the victims whose land was included on the map of March 22, 2007, whose compensation was the responsibility of Lapindo Brantas. The company had to pay Rp.3,830,547,222,220 in compensation, divided among 13,100 victims. However, in 2014 there were still 3,100 victims who had yet to receive full compensation, representing a total monetary figure of Rp.786 billion (Diananta 2014).14)

This situation led to the birth of several organizations, supported by local and national CSOs, to fight for victims’ rights.15) One of these was Korban Lapindo Menggugat (KLM), an object of this research, which was established in 2010. During the 2014 presidential election, KLM transformed itself into a volunteer group supporting Jokowi.

III-1 The Dynamics of KLM’s Struggle

Korban Lapindo Menggugat, as a movement, has united victims of the Lapindo mudflow who are demanding compensation for the destruction and damage they faced following a 100-meter dam breach at points 79 and 80, located in Gempolsari Village, on December 23, 2010. Long before KLM, various other groups were established by victims of the mudflow (Paring 2009; Rusdi 2012; Drake 2013; Anis 2014). These included Pagar Rekontrak (Paguyuban Rakyat Renokenongo Menolak Kontrak, Association of Renokenongo Residents Against Rentals),16) Pagar Rekorlap (Paguyuban Warga Renokenongo Korban Lapindo, Association of Renokenongo Lapindo Victims), Lasbon Kapur (Laskar Bonek Korban Lumpur, Bonek Troop of Mud Victims),17) and Gabungan Korban Lumpur Lapindo (GKLL, Lapindo Mudflow Victims Group)—which subsequently split into two groups in response to the compensation scheme18)—Tim 7 Desa Renokenongo (Seven Team of Renokenongo Village) and Forkom Mindi (Forum Komunikasi Mindi, Mindi Communications Forum).19)

The dam breach of December 23, 2010 allowed mud to flow through the dam and toward the village of Glagah Arum. Mud soon spread over 30 hectares of housing and rice fields, ultimately affecting eight villages: Glagah Arum and Plumbon in Porong District; Permisan and Bangunsari in Jabon District; and Kalidawir, Gempolsari, Sentul, and Penatarsewu in Tanggulangin District (Ugo 2011).20) As a result, residents of these villages had to evacuate, and their harvests failed. This led them to conduct demonstrations outside the Sidoarjo Parliament in January 2011 and demand compensation for their destroyed land, homes, rice fields, and fish farms as well as polluted rivers and air. The people of Gempolsari also demanded clean water. Residents of four villages—Sentul, Glagah Arum, Gempolsari, and Penatarsewu—blocked the alternative route between Surabaya and Malang for two days (October 24–25, 2011) to pressure BPLS to quickly pay compensation (Idha Saraswati 2011).

The January 2011 demonstrations were facilitated by a local parliament member from the PDI-P (Partai Demokrat Indonesia–Perjuangan; Democratic Party of Indonesia–Struggle) named Mundir Dwi Ilmiawan. He was a legislative member from the Sidoarjo 2 electoral district, which included several districts affected by the mudflow: Jabon, Krembung, Porong, and Prambon. Ilmiawan then asked Wardah Hafidz renowned CSO activist, to help residents organize their demands. Hafidz was the coordinator of the Urban Poor Consortium (UPC), an organization with extensive experience in defending the interests of Indonesia’s urban poor. After meeting with the UPC, KLM received guidance and organized its demands. It also received strategic training on how to voice its demands, as well as an invitation to join UPLINK (Urban Poor Linkage), a network of urban poor organizations and their supporters.21)

KLM has not limited its demands to compensation. The group has also argued against further drilling at the site. In total, Lapindo Brantas owns 30 wells in Sidoarjo, spread through Porong and Tanggulangin Districts. In Kali Dawir, for instance, it owns two wells; both were drilled before the eruption of the Banjar Panji-1 Well in Renokenongo. Since the disaster, residents have consistently rejected further drilling. On April 22, 2012, approximately 150 residents from five villages—Glagah Arum, Penatarsewu, Kalidawir, Sentul, and Gempolsari—held a vigil against Lapindo Brantas’s gas drilling and called for the company to leave Sidoarjo. KLM has also protested BPLS’s decision to divert mud to the Ketapang River (Melki 2013) owing to the serious pollution and damage to irrigation systems this has caused. To this end, on November 29, 2013 KLM went to the Sidoarjo Parliament to demand that BPLS stop diverting mud to the Ketapang River. Because the northern dams were in increasingly critical condition, KLM also called for BPLS to reinforce existing dams. Both demands were unsuccessful (Abdul 2013); in 2014, mud was still being diverted into the Ketapang River and no reinforcement efforts had been undertaken.22) This failure was related to victims’ refusal to allow BPLS to redirect mud into the Porong River and reinforce the dams until they had received compensation from Lapindo Brantas.

Furthermore, KLM, working with UPC, demanded that persons who applied for birth certificates more than a year after birth being reported be able to do so without going to court or paying any fees.23) After data collection and document verification, it was found that some 400 members of KLM did not have a birth certificate. These certificates were fought for at the Civil Registry, local parliament, State Court, and Regent’s Office beginning in June 2013. KLM even sent birth certificate applicants’ data to the Komisi Perlindungan Anak Indonesia (KPAI, Indonesian Child Protection Commission) in Jakarta to prepare for a case in the Constitutional Court. This struggle was ultimately successful. The Regent and State Court for Sidoarjo promised that 400 birth certificate applications from KLM members would be handled without cost and could be filed collectively. This was an important symbolic victory for the residents, as birth certificates are crucial as basic administrative proof for residents to claim their rights, including compensation.

Every year KLM, in collaboration with UPC, holds a ceremony commemorating the Lapindo mudflow tragedy. This is intended to maintain morale and ensure that the issue remains alive in the public’s memory—not only among affected individuals but also among outsiders, especially policy makers. Nevertheless, these efforts have not completely succeeded. KLM members have been afflicted by a sense of hopelessness, as shown by the group’s declining membership. One member of KLM indicated that most members had become worn out because their demands had had very few results.24) In 2013, field data indicate, there were only 480 active KLM members, from four villages.25) Residents of the other four villages were no longer active in KLM activities.

IV Roots of the Volunteer Movement in Surabaya: Forced Evictions in Stren Kali

IV-1 Land Issues in Stren Kali, Surabaya

The Jagir River is a man-made tributary of the Mas River that was first excavated during the Dutch colonial period. It runs along Jagir Wonokromo Street. During the Dutch colonial period, the clear waters of the Jagir carried the boats of fishmongers and bamboo sellers and served nearby residents’ bathing and washing needs. Before the 1950s, the banks of the Jagir River were uninhabited land filled with weeds. Slowly, however, as the city of Surabaya developed, this empty land became occupied by informal-sector workers such as pedicab drivers, beggars, vagrants, and sex workers. Aside from constructing their own dwellings, the people living in Stren Kali established businesses such as corner stores and repair shops (LKHI 2009).

The banks of the Jagir River became more crowded in 1964, when the Wonokromo Market was expanded and approximately 50 merchants—mostly ironmongers—were relocated. The Surabaya municipal government offered these merchants two alternatives: to be relocated to an empty shop in the market measuring approximately 2.5 × 4 meters, or to be relocated to the Jagir–Wonokromo area along the riverbanks. Most merchants took the second option. In this new area, they built places to live and do business. When the Social Department of Surabaya relocated more residents in 1970, Stren Kali was the location of choice. With funds from the PONSORIA WAWE (a sort of lottery), in 1970 the government built Jagir Avenue. Public transportation such as DAMRI buses and minibuses began to operate in the area. Electricity became available in 1983 (ibid.). The area, though populated by the city’s lower-class residents, thus had ready access to lighting and transportation. Stren Kali became increasingly crowded as Surabaya grew as a trade and service city and as the provincial capital of East Java. This area quickly developed into an enclave for Surabaya’s poor.

Stren Kali’s strategic location has been a main consideration with residents in choosing a place to live. Data released by Arkom Indonesia in 2012 indicate that 51.6 percent of Stren Kali residents live less than a kilometer from their place of work, with a further 15 percent living 1–3 kilometers from their place of work. Many residents (42.5 percent) have a monthly income of less than Rp.500,000; 33.1 percent earn between Rp.500,000 and Rp.1,000,000; 10.7 percent earn between Rp.1,000,000 and Rp.1,500,000; and 13.7 percent earn more than Rp.1,500,000. This further indicates that the residents of Stren Kali are predominantly the city’s poor. Many homes are located directly on the banks of the Jagir River. When this researcher went with Gatot, an informant from PWSS, to the local meeting hall one night, he passed a row of narrow “houses” made of sheet metal and measuring only 3 × 3 meters. These were used either as family housing or as a place for sex workers to do business. According to Gatot, after the Doli prostitution district was closed, Stren Kali became the location of choice for former Doli sex workers, who joined the sex workers already living in the area. When this researcher passed the area in daylight, Stren Kali was relatively empty.

Most of Stren Kali’s residents have lived there for 30 years. Said, an informant from the kampung (kampong) of Bratanggede, explained that he was the second generation of his family to live there, his parents having relocated to Stren Kali in 1957.26) Residents of Stren Kali who were not born there often migrated to join family (37.5 percent) or friends (17.1 percent) originally from the area. Covering an area of 6.76 hectares, Stren Kali is the location of 926 buildings (59.3 percent permanent, 30.9 percent semi-permanent, and 9.8 percent non-permanent). These are predominantly (57.8 percent) used for housing, though some (33.6 percent) are used as places of business (ArkomIndonesia 2012). The 926 buildings in Stren Kali are occupied by 817 families, 109 of whom rent their homes. Although most residents own their homes, proof of ownership is non-standard. Some have building construction permits, but most only have permission in the form of a letter from the water company, a business registration, or a statement of land/home ownership based on a receipt. This reflects the various ways in which residents came to occupy their land: through purchase, inheritance, direct settlement, relocation (after eviction), permission from the water company, and rental. As such, each kampung has a different history to its settlement (Totok and Ita 2009).

IV-2 Creation of the Advocacy Group Geser Bukan Gusur (Squeeze Past Not Evict)

Beginning in 2002, the people of Stren Kali began to face threats of eviction, as they were said to cause the pollution and shallowing of the Jagir River. On May 31, 2002, the Surabaya municipal government surprised the residents of Stren Kali with a warrant for demolition. This warrant was issued because the government felt that garbage and waste from the settlements in Stren Kali had led to the Jagir River becoming shallower and polluted (LKHI 2009). In response, residents, many of whom were street vendors, sex workers, and street children, organized themselves by establishing the umbrella group Jerit (Jaringan Rakyat Tertindas, Network of Oppressed Peoples). Three years later, in February 2005, six kampungs that had originally been part of Jerit (Bratang, Jagir, Gunungsari, Jambangan, Kebonsari, and Pagesangan) broke off and established their own group, PWSS (Laurens 2012). As time passed, membership expanded to include 11 kampungs: Bratang, Jagir, Gunungsari 1 and 2 (Gunungsari PKL), Jambangan, Kebonsari, Pagesangan, Semampir, Kampung Baru, Kebraon, and Karangpilang.

After PWSS was established, UPC and a network of academics, architects, sociologists, and legal experts guided residents in formulating an alternative concept to kampung management that integrated residents’ needs with the river’s. This concept, referred to as JOGOKALI, was conveyed through lobbying and dialog to the provincial government of East Java and the Surabaya municipal government as well as the Ministry of Public Works, Housing, and Regional Infrastructure. This led to several agreements being reached, including the formation of a joint team involving the conflicting parties. This team, however, proved incapable of reaching a satisfactory compromise.

The situation worsened in January 2005, when the provincial government sent a warning to residents of Medokan Semampir (part of the Stren Kali settlement) that they would be forcibly evicted so that the river could be broadened. After extensive negotiations, PWSS and the provincial government agreed to establish a joint team to formulate a new policy for Stren Kali. At the same time, PWSS—working with Ecoton, Friends of the Earth Indonesia, and Gadjah Mada University—conducted a study that found 60 percent of the river’s pollution originated from factories; only 15 percent originated from riverbank residents. The results of this study, however, did little to discourage the government’s decision to expand and deepen the river. This would require the demolition of 3,400 homes; residents would be relocated to a subsidized housing complex some 5 kilometers distant. Negotiations continued, and ultimately a compromise was reached. This compromise was given legal basis with Regional Bylaw No. 9 of 2007 regarding the Management of Riparian Zones for the Surabaya River and Wonokromo River, dated October 5, 2007. This bylaw was based on a principle of movement, not eviction, and its Article 13 fixed the width of the riparian zones to 3–5 meters, as proposed by PSWW (Wawan et al. 2009).

On January 30, 2009 the Jagir River overflowed, and as a result the Surabaya municipal government decided to build a new dyke and evict residents. To this end, it prepared 300 subsidized housing units for the residents of Stren Kali (Kompas 2009). On April 28, 2009, residents received written instructions, citing violations of Municipal Bylaw No. 7 of 2002 regarding Building Construction Permits, that they were to demolish their buildings by April 30, 2009. In response, PWSS held demonstrations in front of Parliament and the Municipal Government building (Warta Jatim 2009). This, however, had no influence on the government. On May 4, 2009, 1,900 government security forces—consisting of police, soldiers, and Civil Service Police Unit officers—came to Stren Kali armed with a water cannon, a bulldozer, three backhoes, and trained dogs. They forced the eviction of residents living on the south side of the Jagir River (East Java Province Information Office 2009). Residents unsuccessfully resisted through prayers, blockades, and roadblocks. Some 380 buildings were demolished, and 425 families lost their homes and livelihoods (Detik 2009). Several years later, in May 2012, the provincial government, with the support of the municipal government, planned to evict residents from the river’s northern banks. PWSS, however, refused, referring to Article 13 of Bylaw No. 9 of 2007 (Kompas 2012b).

Recognizing that environmental issues had been behind the government’s actions, between 2002 and 2006 residents of Stren Kali began to reinforce their position by implementing the JOGOKALI principle, in which they worked together to keep the kampung healthy and the river pollution-free while still maintaining social and cultural ties in the kampung. Capital for these efforts came from the selling of paper and plastic waste, both from residents’ own homes and from the river. Residents established systems of household waste management, constructed communal septic tanks, and sorted and managed their own garbage (Yuli 2009). These activities were done jointly, indicating PWSS’s strong internal cohesion.

V From Advocacy to Volunteerism: The Metamorphosis of the KLM and PWSS Movements

The momentum of the 2014 presidential election brought new hope for KLM and PWSS. Together with the Jaringan Rakyat Miskin Kota (JRMK, Network of the Urban Poor), which had joined with UPLINK and Jaringan Rakyat Miskin Indonesia (Jerami, Network of Indonesian Poor),27) KLM and PWSS made a political contract with the Indonesian presidential candidate Jokowi. This political contract was signed by Jokowi during a ceremony marking the eighth year of the Lapindo mudflow, held on May 29, 2014, in Siring, Porong, Sidoarjo. This political contract emphasized Jokowi’s commitment to five basic issues: health care through the Indonesia Sehat (Healthy Indonesia) program,28) education through the Indonesia Pintar (Smart Indonesia) program,29) poverty eradication through resettlement programs based in an approach of “Move Don’t Evict”; the resolution of the Lapindo problem through a bailout scheme for the victims; and a job security program.

This political contract was not the first for these parties. During the 2012 gubernatorial elections in Jakarta, Jokowi had signed a similar contract with JRMK and UPC on September 15, 2012. This contract included Jokowi’s agreement to present a new, pro-poor, concept of Jakarta that was based in service and civil participation and called for, among other things, community participation in zoning planning; budgeting; and the planning, implementation, and supervision of urban development programs. It also promoted the fulfillment and protection of urban residents’ rights through the legalization of illegal kampungs; use of discussion and non-eviction approaches to relocating slums; management of the informal economy to better support street vendors, pedicab drivers, traditional fishermen, housemaids, small merchants, and traditional markets; and transparency and openness in the dissemination of information to urban residents (Anggriawan 2012). When Jokowi was elected, he fulfilled the terms of this contract. The relocation of residents from the banks of the Pluit Reservoir and Muara Baru River to subsidized housing, for instance, was conducted through dialog with local residents and involving JRMK and UPC (Irawaty 2013).

The signing of their political contract with Jokowi on May 29, 2014 marked the beginning of KLM and PWSS’s formal support for Jokowi’s candidacy (see Fig. 1). It was the beginning of the groups’ metamorphosis from advocacy organizations to volunteer organizations. Their reason for providing this support can be derived from the writer’s interview with Warsito, a member of PWSS30) who related this support to the groups’ hopes that their long struggles could finally bear fruit. The use of a political contract to achieve political goals was not new in Indonesia.31) PWSS had twice previously made political contracts with candidates, during Surabaya’s mayoral elections in 2010 and the East Java gubernatorial elections in 2013. However, the results of these contracts had been disappointing, as the PWSS-backed candidates were not elected.32) For PWSS, the political contract was understood as a concrete manifestation of its political participation, as stated by Gatot:33)

Fig. 1 Jokowi at Lapindo, Sidoarjo

Source: http://us.images.detik.com/content/2014/05/29/157/jkw01.jpg, accessed November 29, 2014

This political contract is a pillar of sorts, regarding how to participate in politics. Participating in politics means that we need to be involved in political issues. We are not just a source of votes. If we are just a source of votes, yeah, then we’re only a target of money politics. Because we’re involved, then automatically we need to put something forth to the candidate: a contract.34)

The joint decision of KLM, PWSS, and the other movements in UPLINK to support Jokowi was reached long after he was formally proposed as a presidential candidate35) and after a lengthy process in which the group considered possible benefits and costs, as well as the ideal criteria for their candidate.36) Before the year-end meeting in Jakarta, UPLINK and UPC met in Stren Kali exclusively to discuss the political contract; this meeting was predominantly to consolidate the steps they would take, as they had already made numerous efforts to gain political support from various parts of society. In the context of Sidoarjo and Surabaya, the decision had particular weight as PDI-P had a strong voter base in Surabaya and the two parties that promoted Jokowi’s candidacy—PDI-P and the Partai Kebangkitan Bangsa (PKB, National Awakening Party)—had an absolute majority.37)

Following the year-end meeting, UPC worked to arrange a meeting with Jokowi so that it could convey the aspirations of Indonesia’s urban poor. On April 30, 2014, some 50 UPLINK activists came to Jokowi’s official home (where he lived while serving as governor of Jakarta) at 7 Taman Suropati Street, Menteng, Central Jakarta. In this meeting, PWSS (represented by Said and Warsito) and KLM (represented by Manarif) negotiated a plan, which was then conveyed by Said.38) This audience resulted in Jokowi promising that he would initiate economic equalization programs, particularly for the poor. Although no concrete details or activities regarding such measures were discussed, the meeting was sufficient for UPLINK and UPC to agree to support Jokowi. Members would go door-to-door to collect coins and voice support in seven cities (Lampung, Bratasena, Jakarta, Surabaya, Porong, Makassar, and Kendari) and thus help ensure Jokowi’s victory. It was during this meeting that UPLINK and UPC invited Jokowi to attend the ceremony commemorating the Lapindo mudflow’s eighth anniversary. On May 29, 2014, Jokowi attended the ceremony and signed the political contract (UPLINK and UPC 2014).

KLM’s political support was granted to the running mates of Jokowi and Jusuf Kalla (JK) for a simple but clear reason: Jokowi’s faction had no political elite, nor did it have any political forces connected to the Lapindo disaster. Conversely, Jokowi’s opponent Prabowo was supported by many people and groups with ties to the Lapindo disaster, including Golkar—a key figure of which was Aburizal Bakrie,39) the majority shareholder of Lapindo Brantas. Jokowi was thus believed to be capable of resolving the situation because he had no conflict of interest.40) Following through on the agreement reached during the audience with Jokowi, KLM and PWSS began to take action as volunteers for Jokowi–JK. The groups used three types of activities to gather support and votes for Jokowi: Coins for Change, painting the roofs of their homes with Jokowi’s name, and rapping. UPC served as the initiator and driving force behind these campaigns and also provided logistical support such as shirts, flyers, stickers, and tabloids.

Volunteer Method 1: Coins for Change

Koin Perubahan (Coins for Change) was held in every city in the UPLINK network to promote a Jokowi victory. Coins for Change was a symbolic act against money politics. Gatot stated:

Coins for Change was an effort to deflect rumors or charges that the poor could have their votes bought. Through these Coins for Change, we attempted to deflect such political games. What people needed was for their aspirations to be heard by their representatives. What the poor people wanted was change.41)

The total amount of funds collected was limited. The entire national UPLINK network was capable of collecting coins only to the value of Rp.27 million; on its own, KLM collected Rp.1.5 million. The entire sum was donated to the Jokowi campaign via funds transfer. PWSS initially planned on collecting funds by panhandling at traffic lights, in the markets, and in the kampung outside of Stren Kali. However, owing to the limited time available volunteers focused exclusively on traffic intersections.42) While collecting coins, they also distributed stickers and flyers regarding the political contract with Jokowi.

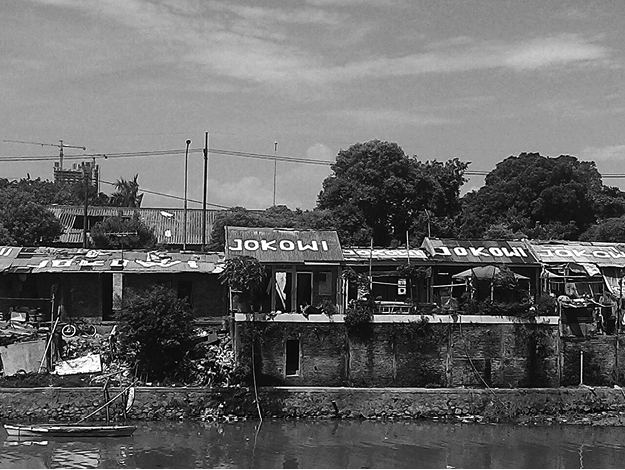

Volunteer Method 2: Painting Jokowi’s Name on Roofs

Painting the roof of each resident’s home with Jokowi’s name in capital letters was—according to Gatot—Wardah Hafidz’s idea (see Fig. 2). He was inspired to do so by his experiences in numerous villages, where each government office had the letters PKK (short for Pembinaan Kesejahteraan Keluarga, Guidance for Family Prosperity) painted on its roof. At first it was agreed that roof painting would be done in every part of the UPC network, with the intent to set a record that would be recognized by the Museum for Indonesian and World Records. However, only PWSS successfully realized this goal. Painting was carried out simultaneously in 11 kampungs, from Kebraon to Semampir. Residents used chalk paint mixed with glue in the hope that the paint would not easily run. Said termed this an “air campaign,” as persons photographing the kampung from the sky would clearly see the word “Jokowi.”43)

Fig. 2 Jokowi’s Name Painted at Kampung Baru, Stren Kali (November 26, 2014)

The movement’s success depended on several factors, including a leader figure capable of mobilizing residents,44) a high degree of participation from residents—as evidenced by their willingness to pay for their own materials—the relatively solid organizational structure of PWSS, and residents’ views regarding their actions. For PWSS, this painting was important, particularly as proof of its dedication. Warsito explained,

This painting was proof that the people of Stren Kali weren’t fooling around. Whatever happened, even if our opponents badgered us, our choice was Jokowi. Yeah, Jokowi. Imagine what would have happened if Jokowi lost. What would happen to us? Surely Prabowo’s volunteers would have attacked us. This was dangerous. Praise God, we won.45)

The courage to openly state political affiliations represented the widespread transformation in Indonesian democracy since 1998, which supported increased openness. Such a hypothesis must, however, be tested through further research.

Members of KLM also intended to paint the roofs of their homes with Jokowi’s name, as done by the volunteers in Stren Kali, but this did not happen because KLM had insufficient funds.46) A significant contribution to this failure to mobilize members was the fact that KLM required funds for emergencies. However, this was only a partial cause. Another was that the environment in which KLM was active tended to be very permissive of money politics. According to information collected from a variety of sources, after elections (be they legislative or executive), an incredible amount of money circulated among residents. This was unlike the environment in which PWSS worked, where residents were mobilized in part as symbolic resistance to money politics. Another contributing factor was that, as the organization had only gained exposure with the entry of UPC, KLM lacked the internal cohesion of PWSS.

Volunteer Method 3: Rapping

Rapping is a voter organization method involving door-to-door campaigning. It was introduced to Indonesia through the Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now, which taught the method to UPC and UPLINK in 2007. The name “rap” was inspired by the musical genre, which involves quick and repetitive lyrics. This method of campaigning is likewise done quickly, generally consisting of five steps taking approximately 20 minutes (unlike conventional campaign models, which require a longer period of time). Rapping as an organizational model involves an organizer (the “rapper”) approaching individuals to convince them to vote and become involved in resolving problems by making demands of or negotiating with persons capable of making or changing policies on a social issue (Ari 2012). This method was widely used to collect votes for Barack Obama during his presidential campaign in the United States.

The informant Gatot Subroto described the operational methods in the 2014 presidential election:

The rapping method, basically, it’s like singing rap. People throw questions at each other, come up with arguments, like they are marketing something. What they’re going to say, they’ve already got their points made. Their goals are to convince potential voters to help support our candidate. We did this over and over, so that people would join us. It was like cause and effect. Like, A: Why are you voting for Jokowi? B: Because I don’t like Prabowo. A: Why don’t you like Prabowo? So, when it got to be like that, of course we’d give them the materials, the political contract. If we didn’t have any materials, we couldn’t possibly sell it. We always brought along our political contract as a negotiating tool. If we’d achieved our targets, we’d say “Sorry, we’ll come again tomorrow.” Then we’d schedule a large meeting. We’d call people together. At the time, we did it as we broke the fast together.47)

KLM went door-to-door to visit residents and ask them to support Jokowi, to understand the issues that they were facing, and to become involved in the political contract with Jokowi so that the issues could be resolved once his campaign was successful. Rapping was done over a period of one month and involved approximately 60 rappers, members of both KLM and the UPLINK network. Rapping was done in kampungs that had been affected by the Lapindo mudflow. While rapping, KLM volunteers also distributed flyers that included the political contract that Jokowi had signed with the Lapindo victims. They also placed posters and banners in several strategic points around the dams.

The KLM rappers faced numerous challenges in the field. The goal of each rapper reaching 60 people every day went unrealized. In the face of the community’s increasingly transactional attitude, rappers were capable of reaching only their family and close friends. Every time they met with someone to campaign for Jokowi, they were asked for money (Aspinall and Mada 2014). Money politics was thus the greatest enemy of these volunteer activists. Furthermore, this was the first time that most KLM members had rapped, and as a result implementation was difficult. This was exacerbated by rappers’ limited operational budget. To relieve the financial burden and fund rapping, UPC helped residents establish a cooperative business and trained them in, for example, preparing food to be sold. Unfortunately, with KLM this did not go according to plan. However, with PWSS the fund-raising programs went relatively smoothly, particularly those involving the management and sale of compost and household waste.

Volunteers were faced with the dilemma of supporting themselves and their families while still fulfilling their political duties as volunteers. Because volunteers originated from the lower class, they had difficulty balancing these two issues, and the most logical choice for them was to focus on the former. Their volunteer activities were secondary to their need to financially support themselves and their families. For them, mobilizing financial resources was not a central issue. This case indicates that lower-class volunteers had greater difficulty collecting financial support.

Aside from going door-to-door, volunteers from KLM were also active in supporting Jokowi at the polling stations. They served as witnesses and members of the Kelompok Penyelenggaraan Pemungutan Suara (KPPS, Committee for Election Operations). Witnesses from KLM were not from political parties, but rather present at the polling stations to see and record votes for Jokowi. Members of KLM who were also members of village-level election committees supervised the counting and escorting of votes at the village level. In Kalidawir Village, this was handled by Manarif, who served as a member of the KPPS. All of Manarif’s campaigning was done outside of the village, as legally he was required to act neutrally.48)

In Stren Kali, meanwhile, rapping was not a new experience. In 2009, UPC had taught PWSS how Obama’s volunteers had used this method to campaign for their candidate. Gatot, together with other representatives of his movement, went to Jakarta for training. PWSS first used this method during the 2010 mayoral elections in Surabaya as part of its campaign for the independent running mates Fitradjaja Purnama and Naen Soeyono. In this election, five pairs of candidates ran, with Tri Rismahani and Bambang DH of PDI-P winning with 358,187 (38.53 percent) votes. Fitradjaja came last, with only 53,110 votes (5.71 percent) (Elin 2010). Although Fitradjaja won in Stren Kali, a subsequent evaluation by UPC found that he had benefited from a strong “follow the leader” system that had led Stren Kali residents to vote for him. Rapping, thus, had been unable to develop residents’ political awareness (UPC 2010). During the presidential election, PWSS asked for the General Elections Committee’s registered voters list to determine appropriate targets. Each person rapped to 50 potential voters, and each RT had its own coordinator. The number of rappers assigned to an RT depended on its population and total area; some RTs had three or four rappers.

From the results of the presidential election, it is difficult to determine whether PWSS and KLM’s involvement played a role in Jokowi’s victory. Of the 31 districts in Surabaya, only 1 was won by Prabowo–Hatta, where the pair received 36,829 votes to Jokowi–JK’s 35,563. Jokowi–JK won all 30 other districts. The 11 kampungs joined in PWSS were won by Jokowi. Monitoring efforts by the Kawal Pemilu Web site confirm this Jokowi victory. In Jagir, Prabowo–Hatta received 4,352 votes (43.31 percent), whereas Jokowi–JK received 5,697 (56.69 percent) (Agita 2014; Kawal Pemilu 2014b).

A different pattern was found in Sidoarjo. In this regency, Jokowi–JK received 550,729 votes (54.22 percent), slightly above the national average of 53.15 percent, while Prabowo–Hatta received 464,990 votes (45.78 percent). In Tanggulangin District, Jokowi–JK were victorious with 23,698 votes (50.71 percent), below the national average; Prabowo–Hatta received 23,031 votes (49.29 percent). In Porong District, Jokowi–JK were victorious with 21,316 votes (57.53 percent), whereas Prabowo–Hatta received 15,734 votes (42.47 percent). The data indicate, however, that Jokowi–JK were not victorious in all areas united by KLM. In Kalidawir, for instance, where three of the informants lived, Jokowi–JK suffered a rather significant loss: they received 919 votes (42.76 percent), while Prabowo–Hatta claimed victory with 1,230 votes (57.24 percent) (Kawal Pemilu 2014a).

VI Conclusion

This article has discussed volunteer movements in the 2014 Indonesian presidential election as practiced by communities facing concrete problems requiring concrete solutions. Several points from the above discussion should be emphasized. First, the transformation of KLM and PWSS into volunteer movements in support of Jokowi was intended to resolve issues that the groups had already faced for several years. Belying the general view of volunteers as actors without personal considerations or hope for remunerations, but rather romantic, idealistic, and altruistic intentions, both cases show the opposite to be true: volunteer actions here were considered and self-serving. Unlike in Ukraine, where individual-based financial considerations were the motor that mobilized volunteers, KLM and PWSS used collective-based political considerations as their mobilizing motor. Likewise, belying the general view of volunteerism as promoting an abstract goal with personal satisfaction as the central explanatory factor, both cases show that volunteer movements can be formed to realize concrete, short-term goals.

Second, both cases indicate the instrumental nature of volunteer movements. These movements were used as tools to realize groups’ subjective interests, namely, compensation and not being evicted. They were negotiation tools offered in exchange for Jokowi’s willingness to resolve the issues the groups faced. This indicates a further, self-centered, dimension of the volunteer movements. Contrary to the argument promoted by Marcus Mietzner (2015) that Jokowi’s magnetism and leadership style—described as “technocratic populism”—was sufficient to explain the extraordinary number of volunteers backing him in the 2014 presidential election, these two cases indicate that movements were more self-centered—focused on groups’ own self-interests. Though not explicitly stated during research, it is apparent that these volunteer movements emerged from a rational calculation by KLM and PWSS regarding the potential of a Jokowi victory. In short, Jokowi was supported because he promised victory, and through his election these groups’ own issues could be addressed.

Third, KLM and PWSS had some similar characteristics: both were movements of marginalized groups specifically targeted at resolving the issues they faced. Both used similar approaches and received support from the same national networks of CSOs. In terms of achievement, however, they differed significantly: PWSS was much more successful than KLM. This can be attributed to PWSS’s higher level of internal cohesion as well as its greater capacity. In both cohesion and capacity, PWSS greatly outpaced KLM in its mobilization.

Finally, both cases showed that a lack of finances, spare time, and civic skills—all important elements of volunteering—was a serious problem for volunteer groups of marginalized peoples. The idea that spare time was (hypothetically) available to lower-class volunteers was shown to be incorrect; spare time remained a rare commodity. Volunteers had to use their time for one of two non-overlapping activities: activities that satisfied their own individual, corporeal hunger, or activities of a political nature that could help them realize their collective goals.

Accepted: December 9, 2016

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my gratitude to Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Gadjah Mada University and to Power Welfare Democracy Project, Department of Politics and Government, Gadjah Mada University in providing financial support for field research. I would like to thank my colleagues Dr. Amalinda Savirani and Dr. Haryanto for their valuable comments, and Iqbal Basyari and Umi Lestari for their assistance during field research.

Bibliography

Abdul Rouf. 2013. Kondisi tanggul lumpur Lapindo kritis [Condition of dams at Lapindo mudflow critical]. Okezone News. April 28. http://news.okezone.com/read/2013/04/28/521/798918/kondisi-tanggul-lumpur-lapindo-kritis, accessed December 8, 2014.

Abidin Kusno. 2007. Penjaga memori: Gardu di perkotaan Jawa [Guardian of memories: Gardu in urban Java]. Yogyakarta: Ombak.

Adam, M.; and Yulika, N. C. 2013. Kemendagri: Ormas yang tercatat di kementerian ada 139 ribu [Minister of Internal Affairs: CSOs recorded at the ministry 139 thousand]. Viva. co.id. July 24. http://www.viva.co.id/ramadan2016/read/431521-kemendagri-ormas-yang-tercatat-di-kementerian-capai-139-ribu, accessed November 12, 2014.

Agita Sukma Listyanti. 2014. Hari ini KPU Surabaya tetapkan rekap hasil pilpres [Today the Elections Committee of Surabaya will determine election results]. Tempo. July 17. https://m.tempo.co/read/news/2014/07/17/269593657/hari-ini-kpu-surabaya-tetapkan-rekap-pilpres, accessed May 6, 2016.

Akuntono, I. 2014. Disindir SBY soal lumpur Lapindo: Ini komentar Bakrie [Mocked by SBY on the Lapindo mudflow: This is Bakrie’s comment]. Kompas. April 8. http://nasional.kompas.com/read/2014/04/08/1816067/Disindir.SBY.soal.Lumpur.Lapindo.Ini.Komentar.Aburizal.Bakrie, accessed May 3, 2016.

Anggriawan, F. 2012. Jokowi minta warga pilih nomor 3 [Jokowi asked resident to choose number 3]. Okezone News. September 5. http://news.okezone.com/read/2012/09/15/505/690365/jokowi-minta-warga-pilih-nomor-3, accessed June 5, 2016.

Anis Farida. 2014. Reconstructing Social Identity for Sustainable Future of Lumpur Lapindo Victims. Procedia – Environmental Sciences 20: 468–476. DOI: 10.1016/j.proenv.2014.03.059.

Ari Ujianto. 2012. Power from Below: Gerakan Perempuan Miskin Kota di Makassar [Power from below: The Movement of Urban Poor Women in Makassar]. Srinthil. October 29. http://srinthil.org/233/power-from-below-gerakan-perempuan-miskin-kota-di-makassar/.

ArkomIndonesia. 2012. Penataan kampung terpadu bersama komunitas: Pembelajaran dari Surabaya [Exemplary village management with the community: Lessons from Surabaya]. http://www.slideshare.net/arkomindonesia/tata-kampung-surabaya, accessed November 30, 2014.

Aspinall, Edward; and Mada Sukmajati, eds. 2014. Politik uang di Indonesia: Patronase dan klientelisme pada pemilu legislatif 2014 [Money politics in Indonesia: Patronage and clientelism in the legislative election of 2014]. Yogyakarta: Polgov.

Bosman Batubara. 2013. Perdebatan tentang penyebab lumpur Lapindo [Debate on the cause of the lapindo mudflow]. In Membingkai Lapindo: Pendekatan konstruksi sosial atas kasus Lapindo (sebuah bunga rampai) [Wrapping up Lapindo: A social construction approach to the Lapindo case (a summary)], edited by Novenanto, pp. 1–16. Yogyakarta: MediaLink and Kanisius.

―. 2012. Kronik lumpur Lapindo: Skandal bencana industri pengeboran migas di Sidoarjo [The Lapindo mudflow chronicles: The scandal of an oil and gas drilling company in Sidoarjo]. Yogyakarta: Insisit Press.

―. 2009. Perdebatan tentang penyebab Lumpur Sidoarjo [Debate on the cause of the Sidoarjo mudflow]. Jurnal Disastrum 1(1): 13–26.

Bosman Batubara; and Paring Waluyo Utomo. 2010. Bencana industri: Relasi negara, perusahaan dan masyarakat sipil [Industrial disaster: State relations, companies, and civil society]. Jakarta: Desantara.

Brand South Africa. 2014. Election Volunteers: The Beating Heart of Democracy. May 6.

https://www.brandsouthafrica.com/governance/developmentnews/election-volunteers-the-beating-heart-of-democracy, accessed November 23, 2015.

Bryden, Joan. 2015. Federal Election 2015: Volunteer Armies Use New Technology to Focus Campaign Efforts. The Huffington Post. May 31. http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2015/05/31/how-old-fashioned-volunte_n_7479648.html, accessed November 25, 2015.

Cornelis Lay. 2010. Broken Linkages: A Preliminary Study on Parliament–CSO Linkages in Indonesia. Paper presented before the Panel on Indonesian Democracy in Comparative Perspectives at Euroseas Conference, Guttenberg, August.

CSIS Survey. 2012. Rakyat Makin Anti dengan Partai [More antisentiment for political parties]. BeritaSatu. February 13. http://www.beritasatu.com/politik/31287-survei-csis-rakyat-makin-anti-dengan-partai.html, accessed November 12, 2014.

Davies, Richard J. 2007. Birth of a Mud Volcano: East Java, 29 May 2006. Journal of Geological Society of America 17(2) (February): 4–9.

Detik. 2014. Total ganti rugi lahan lumpur Lapindo capai Rp 7,8 triliun [Total provision of land affected by Lapindo mudflow reaches Rp.7.8 trillion]. September 29. http://finance.detik.com/berita-ekonomi-bisnis/d-2703729/total-ganti-rugi-lahan-lumpur-lapindo-capai-rp-78-triliun, accessed June 2, 2016.

―. 2009. Petugas eksekusi ratusan rumah semi permanen [Officials take hundreds of semi-permanent homes]. May 4. http://news.detik.com/berita/1125626/ribuan-petugas-eksekusi-ratusan-rumah-semi-permanen, accessed November 30, 2014.

Diananta P. Sumedi. 2014. Harus bayar warga: Lapindo pelajari putusan MK [Required to pay residents: Lapindo examines Constitutional Court decision]. Tempo. March 27. https://m.tempo.co/read/news/2014/03/27/092565923/harus-bayar-warga-lapindo-pelajari-putusan-mk, accessed May 6, 2016.

Drake, Philip. 2015. Stuck in the Mud in the Shadow of Bakrie. New Mandala. June 30. http://www.newmandala.org/stuck-in-the-mud-in-the-shadow-of-bakrie/, accessed May 18, 2016.

―. 2013. Under the Mud Volcano. Indonesia and the Malay World 41(121): 299–321.

DOI: 10.1080/13639811.2013.780346.

―. 2012. The Goat That Couldn’t Stop the Mud Volcano: Sacrifice, Subjectivity, and Indonesia’s “Lapindo Mudflow.” Humanimalia 4(1): 83–110.

―. 2008. Reassembling Ecological Power: Nature, Capital, Empire in Moreau, Neuromancer, and Mars. http://libweb.hawaii.edu/libdept/pacific/drake.pdf, accessed May 18, 2016.

East Java Province Information Office. 2009. Penggusuran Stren Kali Jagir: Polda dan TNI siagakan 1.900 [Facing the eviction of Stren Kali Jagir: District police and army prepare 1,900 personnel]. May 4. http://m.kominfo.jatimprov.go.id/watch/16885, accessed November 30, 2014.

Eldridge, Philip J. 1989. NGOs in Indonesia: Popular Movement or Arm of Government? Working Paper 55, Centre of Southeast Asian Studies, Monash University.

―. 1988. Non-Governmental Organizations and the Role of the State in Indonesia. Paper presented at the Conference on the State and Civil Society in Contemporary Indonesia, Centre of Southeast Asian Studies, Department of Indonesian and Chinese Studies, Monash University. November 25–27.

Elin Yunita Kristanti. 2010. Risma–Bambang pemenang pilkada Surabaya [Risma–Bambang winners in Surabaya election]. Viva. co. id. June 8. http://nasional.news.viva.co.id/news/read/156229-risma-bambang-pemenang-pilkada-surabaya, accessed May 12, 2016.

Han, Hahrie; and McKinna, Elizabeth. 2015. Groundbreakers: How Obama’s 2.2 Million Volunteers Transformed Campaigning in America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Holmov, Nikolai. 2015. “Political Voluntarism”—Odessa. OddessaTalk. October 23. http://www.odessatalk.com/2015/10/political-voluntarism-odessa/, accessed on November 23, 2015.

Idha Saraswati. 2011. Anggota Korban Lapindo Menggugat ditangkap polisi [Members of Lapindo Accuse arrested by police]. Kompas. October 26.

http://nasional.kompas.com/read/2011/10/26/20111499/Anggota.Korban.Lapindo.Menggugat.Ditangkap.Polisi, accessed June 2, 2016.

Irawaty, D. T. 2013. Penataan Waduk Pluit [Structuring Pluit reservoir]. http://rujak.org/2013/03/partisipasi-warga-dari-pojok-utara-hingga-ujung-selatan-jakarta/, accessed June 5, 2016.

Kawal Pemilu. 2014a. http://www.kawalpemilu.org/#0.42385.46306.46405, accessed June 16, 2016.

―. 2014b. http://www.kawalpemilu.org/#0.42385.51358.51377, accessed June 16, 2016.

Kompas. 2012a. Dampak lumpur meluas [Effects of mud spread]. May 30. http://nasional.kompas.com/read/2012/05/30/03095137/Dampak.Lumpur.Meluas, accessed November 29, 2014.

―. 2012b. Isu penggusuran: Warga Stren Kali Jagir resah [Rumors of eviction: Residents of Stren Kali Jagir uneasy]. May 12. http://regional.kompas.com/read/2012/05/12/11273510/Isu.Penggusuran.Warga.Stren.Kali.Jagir.Resah, accessed November 30, 2014.

―. 2009. Warga Stren Kali: Pengusuran bukan solusi [Residents of Stren Kali: Eviction is not a solution]. April 2. http://regional.kompas.com/read/2009/04/01/20212074/Warga.Stren Kali.Penggusuran.Bukan.Solusi, accessed November 29, 2014.

Laurens, Marcella Joyce. 2012. Changing Behavior and Environment in a Community-Based Program of the Riverside Community. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 36: 372–382. DOI: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.03.041.

Liauw, Hindra. 2012. Lapindo masih jadi sandungan Ical menuju RI I [Lapindo still a stumbling block for Ical’s bid for RI 1]. Kompas. July 8.

http://nasional.kompas.com/read/2012/07/08/1621377/Lapindo.Masih.Bakal.Jadi.Sandungan.Ical.Menuju.RI.1, accessed May 3, 2016.

LKHI. 2009. Sejarah pemukiman dan kronologi penggusuran kawasan Jagir Surabaya [History of residencies and chronology of Jagir area, Surabaya]. May 20. http://lhkisby.blogspot.co.id/2009/05/sejarah-pemukiman-dan-kronologi.html, accessed November 5, 2014.

Mazzini et al. 2007. Triggering and Dynamic Evolution of the LUSI Mud Volcano in Indonesia. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 261(3–4): 375–388. DOI: 10.1016/j.epsl.2007.07.001.

Melki Pangaribuan. 2013. BPLS buang lumpur ke sawah: Warga emosi di DPRD Sidoarjo [BPLS dumps mud in rice fields: Residents emotional at Sidoarjo Parliament]. Satu Harapan. November 30. http://www.satuharapan.com/read-detail/read/bpls-buang-lumpur-ke-sawah-warga-emosi-di-dprd-sidoarjo, accessed December 8, 2014.

Mietzner, Marcus. 2015. Reinventing Asia Populism: Jokowi’s Rise, Democracy, and Political Contestation in Indonesia. Honolulu: East-West Center.

Mowen, John C.; and Sujan, Harish. 2005. Volunteer Behavior: A Hierarchical Model Approach for Investigating Its Traits and Functional Motive Antecedents. Journal of Consumer Psychology 15(2): 170–182.

Mutjaba Hamdi; Wardah Hafidz; and Gabriela Sauter. 2009. Uplink Porong: Supporting Community-Driven Responses to the Mud of Volcano Disaster in Sidoarjo, Indonesia. Gatekeeper Series 137j. http://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/14581IIED.pdf, accessed June 5, 2016.

Paring Waluyo Utomo. 2009. Menggapai mimpi yang terus tertunda: Menelusuri proses ‘ganti rugi’ terhadap korban lumpur Lapindo [Reaching for an ever-delayed dream: Exploring the “compensation” process for the victims of the Lapindo mudflow]. Jurnal Disastrum 1(1): 27–46.

Program S2 Politik Lokal dan Otonomi Daerah [Post Graduate Program of Local Politics and Regional Autonomy, PLOD]. 2006. Keterlibatan publik dalam desentralisasi tata pemerintahan: Studi tentang problema, dinamika, dan prospek civil society organization di Indonesia [Public involvement in the decentralization of governance: A study of the problems, dynamics, and prospects of civil society organizations in Indonesia] (unpublished report). Masters Program in Local Politics and Regional Autonomy in collaboration with BRIDGE, BAPPENAS.

Robinson, Daniel. 2000. Participation and Politics. Paper presented before the Workshop on Voluntary Action, Social Capital, and Interest Mediation: Forging the Link, Copenhagen, April 14–19.

Rusdi. 2012. Konflik sosial dalam proses ganti rugi lahan dan bangunan korban Lumpur Lapindo [Social conflict in the process of provision of land and building compensation process for victims of the Lapindo mud disaster]. Yogyakarta: STPN Press.

Tika Primandari. 2013. Elektabilitas ARB tersandera kasus Lapindo [Electability of ARB limited by Lapindo case]. Tempo. November 18. http://m.tempo.co/read/news/2013/11/18/078530356/Elektabilias-ARB-Tersandera-Kasus-Lapindo, accessed May 4, 2016.

Tocqueville, Alexis de. 2000. Democracy in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Totok Wahyu Abadi; and Ita Kusuma Mahendrawati. 2009. Penertiban versus penggusuran: Strategi komunikasi dan partisipasi pembangunan (studi kasus di Stren Kali Jagir Wonokromo, Surabaya) [Management versus eviction: Strategies of communication and development participation (a case study in Stren Jagir Wonokromo, Surabaya)]. Jurnal Scriptura 3(2) (July): 112–128.

Transparency Indonesia. 2013. Corruption Perception Index. December 3. http://www.ti.or.id/index.php/publication/2013/12/03/corruption-perception-index-2013, accessed November 12, 2014.

Ugo. 2011. Korban lumpur Lapindo blokir jalur alternatif Porong [Lapindo mudflow victims blockade alternative road in Porong]. Okezone News. October 24. http://news.okezone.com/read/2011/10/24/337/519772/korban-lumpur-blokir-jalur-alternatif-porong, accessed June 2, 2016.

Urban Poor Consortium (UPC). 2010. Catatan pertemuan pertengahan tahun UPC [Mid-year meeting notes of the UPC]. June 5–7.

Urban Poor Linkage (UPLINK); and Urban Poor Consortium (UPC). 2014. Jokowi janjikan pemerataan ekonomi [Jokowi promises economic equality]. http://jkw4ind.com/uplink-dan-upc-mendukung-jokowi-presiden/, accessed November 12, 2014.

Velix Wanggai. 2015. Menghapus keraguan warga korban lumpur Sidoarjo: 3 menteri kabinet Kerja kunjungi Sidoarjo [Erasing the doubts of the victims of the Sidoarjo mudflow: Three working cabinet ministers visit Sidoarjo]. Pu Net. July 14. http://pu.go.id/berita/10366/Menghapus-Keraguan-Warga-Korban-Lumpur-Sidoarjo,-3-Menteri-Kabinet-Kerja-Kunjungi-Sidoarjo, accessed May 6, 2016.

Ventura Elisawati, ed. 2010. Setahun Koin Keadilan: Sebuah kenangan dan penghargaan untuk orang-orang yang berkehendak baik [A year of Coins for Justice: A memoir and appreciation for people with good intentions]. Jakarta: Rumah Langsat.

Verba, Sidney; Schlozman, Kay Lehman; and Brady, Henry E. 1995. Voice and Equality: Civic Voluntarism in American Politics. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Warta Jatim. 2009. Warga Stren Kali Surabaya tolak penggusuran [Residents of Stren Kali, Surabaya, refuse eviction]. April 2. http://wartajatim.blogspot.co.id/2009/04/warga-stren-kali-surabaya-tolak.html, accessed December 5, 2016.

Wawan Some; Wardah Hafidz; and Gabriela Sauter. 2009. Renovation Not Relocation: The Work of Pagutuban Warga Stren Kali (PWS) in Indonesia. Environment and Urbanization 21(2): 463–475. DOI: 10.1177/0956247809343766.

Wayan Agus Purnomo. 2013. Mengapa Aburizal Bakrie tetap ngotot maju sebagai capres? [Why does Aburizal Bakrie still force his way forward as presidential candidate?]. Tempo. August 7. https://m.tempo.co/read/news/2013/08/07/078502891/mengapa-aburizal-bakrie-tetap-ngotot-maju-capres, accessed May 4, 2016.

Yuli Kusworo. 2009. Stren Kali, Surabaya, contoh untuk Jakarta [Stren Kali, Surabaya, an example for Jakarta]. July 9. http://rujak.org/2009/07/%E2%80%98sunan%E2%80%99-jogokali-gotong-royong-hijaukan-kampung/, accessed January 10 2015.

1) Volunteer movements are not a new phenomenon in Indonesia. In the lead-up to the 1999 general election, supporters of the PDI-P collaborated to erect gardu (meeting places) and communications posts for the PDI-P alongside strategic roads throughout Indonesia, from the cities to the villages (Abidin 2007, 16).

Volunteerism has emerged also in movements against the weakening of the Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi (KPK, Commission for the Eradication of Corruption). These include the Cicak Lawan Buaya (Geckos against Crocodiles) support movement for Bibit Samat Riyanto and Chandra Hamzah (two KPK leaders who were detained by the police in 2009) and Save KPK in 2012. In 2009, Koin Keadilan untuk Prita (Coins of Justice for Prita), which provided support to Prita Mulyasari in her court case against Omni International Hospital, was established. This movement, an initiative of the Langsat Network, mobilized volunteers from a variety of backgrounds and parts of Indonesia to establish communications posts and collect coins (Ventura 2010).

In a local electoral context, volunteer movements—particularly those supporting Jokowi and Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (Ahok)—were prominent during Jakarta’s 2012 gubernatorial elections. The work of these volunteers was not limited to campaigning for Jokowi–Ahok; it also included funding the campaign through the sale of plaid shirts and souvenirs, such as Jokowi–Ahok key chains.

2) Since Reformasi, an increasing number of CSOs have emerged in Indonesia. Data from the Institute for Applied Economic and Social Research and Education (LP3ES) indicate that in 2001 there were only 426 CSOs. Six years later that number had increased to 2,646, according to data from the SMERU Research Institute. In July 2013, the Ministry of Domestic Affairs recorded 139,957 CSOs in Indonesia; these were under the purview of the Ministry of Domestic Affairs (65,577), Ministry of Social Affairs (25,406), Ministry of Law and Human Rights (48,866), and Ministry of Foreign Affairs (108). This number does not, however, include the numerous local-level CSOs (Adam and Yulika 2013).

3) During the New Order, CSOs were concentrated in Jakarta and other major cities (Eldridge 1988; 1989). Since 2001, they have become more widespread. A number can be found in border regions such as Papua and Aceh, as well as East and West Nusa Tenggara. Data from SMERU indicate that these four regions were home to 130, 223, 124, and 136 CSOs respectively in the first six years of Reformasi, compared to the 292, 224, and 209 for Jakarta, West Java, and East Java. This indicates that CSOs have become national in scope, rather than limited to Java.

4) A survey conducted by the Lembaga Survey Indonesia (LSI, Indonesian Survey Institute) between September 9 and 15, 2009 indicated that public trust in political parties had reached a low of 36.3 percent, compared to trust in the bureaucracy (40.3 percent), parliament (45 percent), and mass media (55.5 percent). Three years later, the level of public trust in political parties had yet to increase. LSI’s 2012 survey indicated that political parties were considered the most likely to commit corruption, as compared to institutions such as parliament, the state attorney’s office, the police, the president, the KPK, and the Badan Pemeriksa Keuangan (BPK, Audit Board of the Republic of Indonesia). The 2013 Global Corruption Barometer for Indonesia found parliament and political parties to be perceived by the general populace as corrupt institutions. Parliament was considered the second-most corrupt, whereas political parties were ranked fourth (Transparency Indonesia, December 3, 2013). A survey conducted by the Centre for Strategic and International Studies in February 2012 indicated that societal support for political parties had decreased because voters were disappointed by parties’ performance. Informants considered the parties to be tools used by the political elites to attain power and control over available resources (CSIS Survey 2012).

The lack of trust in governmental institutions was clearly recorded also in social media. One common joke went that a bus carrying all of Indonesia’s members of parliament fell off a cliff. When the police came, all of the passengers had already been buried. When local residents explained what had happened, the police asked “Are you sure that they were all dead? To the point you buried them?” The residents immediately replied, “Well, some screamed that they were still alive. But as you know, we can’t trust anything they say.”

5) Gultom, the coordinating secretary of the Tim Koordinasi Relawan Nasional Jokowi–JK (National Volunteer Coordination Team for Jokowi–JK), claimed that there were approximately 1,289 volunteer groups throughout Indonesia, consisting of an estimated 1–1.5 million people. This figure is based on the declarations of volunteer status released by the team’s office. Many, however, did not register, and thus this is estimated to be only a third of all of the volunteers.

Among the organizations established to support Jokowi were the Seknas Jokowi (National Secretariat for Jokowi), found in 30 provinces and including in its network subgroups such as Seknas Perempuan (National Secretariat for Women) covering women volunteers, Seknas Muda (National Secretariat for Youths) covering youth and student volunteers, Seknas Tani (National Secretariat for Farmers), and Serikat Petani Indonesia (Indonesian Farmers Alliance). Other volunteer groups included the Barisan Relawan Jokowi Presiden (Volunteer Brigade for President Jokowi), Aliansi Masyarakat Adat Nusantara (Alliance of Archipelagic Adat Societies), KSP Prodjo (Prodjo Savings and Loan), Rumah Koalisi Indonesia Hebat (Coalition Home for a Great Indonesia), Kawan Jokowi (Friends of Jokowi), Koalisi Anak Muda dan Relawan Jokowi (Coalition of Youths and Jokowi Volunteers, including such groups of volunteers as HAMI [Indonesian Association of Young Lawyers], JASMEV [Jokowi Advance Social Media Voluntary], JKW4P [Jokowi 4 Pembangunan, Jokowi for Development], Jokowi Centre Indonesia, Jokowi4ME, REMAJA [Relawan Masyarakat Jakarta, Jakartan Social Volunteers]), and GEN A), ALMISBAT (Aliansi Masyarakat Sipil untuk Indonesia Hebat, Alliance of Civil Society for a Great Indonesia), Aliansi Rakyat Merdeka (Alliance of Independent Society), Relawan Buruh Sahabat Jokowi (Labor Volunteers Friends of Jokowi), Laskar Rakyat Jokowi (People’s Troops for Jokowi), Komunitas Sahabat Jokowi (Friends of Jokowi Community), Gema Jokowi (Societal Aspirations Movement for Jokowi), POSPERA (Posko Perjuangan Rakyat, Communications Posts for the People’s Struggle), BRPJ4P (Barisan Rakyat Pendukung Jokowi For President, Brigade of Supporters for Jokowi for President), Jaringan Masyarakat Urban (JAMU, Network of Urban Society), Ayo Majukan Indonesia (Let’s Develop Indonesia), Forum Rakyat Nasional (National People’s Forum), Barisan Jokowi untuk RI (Jokowi for Indonesia Brigade), GEMA JKW4P-7 (Gema Masyarakat Jokowi For President Ke-7, People’s Movement for Jokowi as the 7th President), Komunitas Kasih Matraman Raya (Caring Community of Matraman Raya), Eksponen 96–98 Pro Mega Perjuangan (Exponents 96–98 for Pro Mega Struggles), Alumni ITB Pendukung Jokowi (Alumni of the Bandung Institute of Technology for Jokowi), Alumni Trisakti Pendukung Jokowi (Alumni of Trisakti University for Jokowi), Blusukan Jokowi (Meeting the Grassroots with Jokowi), Komunitas Artis Sinetron Laga (Community of Soap Opera Performers), Pondok Jokowi Presidenku (Lodge for Jokowi, My President), Gerakan Masyarakat Bangkep (Bangkep Social Movement), Keroncong JK4P (Keroncong for Jokowi, for President), FORPERTA, Barisan Relawan Nasional, Gerakan Relawan Jokowi Cimanggin 14 (GRJWC14, Cimanggin 14 Volunteer Movement for Jokowi), and Barisan Pendukung Jokowi (Brigade of Jokowi Supporters). Interview with Gultom, August 14, 2014.

6) Volunteers who distributed flyers were given UAH150 ($6.04 per day), the lowest rate available. Those propagandizing in the streets also received little remuneration, UAH200–250 ($8.06–$10.07) per month. Door-knocker volunteers received UAH3,500–4,000 a month ($140.99–$161.13 per day). They were employed during certain periods of time and were maintained despite being very aggressive in completing their tasks. The gangs managed a small number of door knockers and were paid UAH5,500–7,000 per month ($221.55–$281.97 per day). Above them were the people tasked with supervising and auditing the effectiveness of the work structure below them; they received UAH6,000–8,000 per month ($241.69–$322.26 per day).

7) Aburizal Bakrie served as the chairman of Golkar from October 9, 2009 to December 31, 2015. When the Lapindo mudflow began, he was serving as the coordinating minister for social prosperity (December 7, 2005 to October 21, 2009).

The Banjar Panji-1 Well is a gas exploration well owned by Lapindo Brantas. The owner of this company is the Bakrie Group, a conglomerate established by Achmad Bakrie in 1942. Aburizal Bakrie, the son of Achmad Bakrie, led the Bakrie Group from 1992 to 2004.

8) This view holds that the Lapindo mudflow is man-made and was created by the activities of Lapindo Brantas, which had conducted drilling in Renokenongo Village, Sidoarjo. Owing to a technical error during drilling—a casing was used that was too short for the drill—materials from within the earth began to spew to the surface. The technical term, which has since become popular, is “underground blowout.” Davies, for instance, concludes that the hot mud began spewing to the surface as a result of the drilling activities at Banjar Panji-1 Well.

9) Bosman (2013) views the Sidoarjo mudflow as an industrial disaster and argues that it cannot be categorized as a natural disaster. This disaster, he argues, occurred because Lapindo decided to deliberately not follow industry security procedures. He considers the issue to involve collusion, conflict of interest, and politicization, particularly given Aburizal Bakrie’s ministerial position.

10) Philip Drake understands the Sidoarjo mudflow from a socio-ecological perspective. The mudflow’s handling indicates human failure in the management of ecological needs and in mitigating social and environmental losses. It also positions humans as being the ones to bear risks. He argues that there is an urgent need to develop a new conceptual understanding, which he terms “ecological criticism.” This perspective, he says, is necessary for the interrogation of power (capital structures, capitalist ideology, and relations between humans and nature) as well as the construction of complex and intricate networks through ecological interactions.

11) This group holds that the earthquake that struck the city of Yogyakarta, in central Java, on May 27, 2006 (two days before the Lapindo mudflow first erupted) either led to the creation of a new fracture or reactivated an old fracture, thus allowing the hot mud to flow to the surface.

12) Presidential Regulation 14 of 2007 limits Lapindo’s liability to the area recorded by the MAA of March 22, 2007. The remainder is the responsibility of the government (Article 15, Paragraph 5). As the mudflow has spread, the government has revised this decree to expand its area of responsibility. These revisions have been done through Presidential Regulations 48 of 2008, 40 of 2009, 68 of 2011, 37 of 2012, and 33 of 2013.

13) Payment was divided as follows: 20 percent in the 2008 fiscal year, 30 percent in the 2009 fiscal year, 20 percent in the 2010 fiscal year, 20 percent in the 2011 fiscal year, and 10 percent in the 2012 fiscal year.

14) On April 30, 2015, a few months after being inaugurated, Jokowi passed Presidential Decree 11 of 2015 regarding the Establishment of the Team for the Speedy Resolution of Land and Building Sales for the Victims of the Sidoarjo Mudflow in the Area Recorded in the MAA of March 22, 2007. This was followed on June 26, 2015 by Presidential Regulation 76 of 2015 regarding the Giving of Anticipatory Funds for the Sale of Land and Buildings owned by the Victims of the Sidoarjo Mudflow in the Area Recorded in the MAA of March 22, 2007. Mechanics for the payment of Lapindo’s obligations were set through the publication of the Project Content Form for the 999.99 Budget of the BPLS Work Unit on June 26, 2015 (Velix 2015).