Contents>> Vol. 6, No. 1

Conflict over Landownership in the Postcolonial Era:

The Case of Eigendom Land in Surabaya*

Sukaryanto**

* Part of this paper was originally included in the author’s dissertation, “Konflik Pertanahan di Surabaya: Kasus Tanah Bersurat Hijau 1966–2012” (Land disputes in Surabaya: The case of

Green Certificate land 1966–2012).

** Humanities Program, the Faculty of Cultural Sciences, Gadjah Mada University, Bulaksumur Yogyakarta 55281, Indonesia; History Department of the Faculty of Humanities, Airlangga University, Campus B, Jl. Airlangga No. 4–6 Surabaya, Indonesia

e-mail: skyt_unair[at]yahoo.co.id

DOI: doi.org/10.20495/seas.6.1_63

This article attempts to explore the controversy surrounding eigendom land (land owned under colonial state management rights) in Surabaya and its relations with the enforcement of the Basic Principles of Agrarian Law (BAL), in an effort to realize the ideals of the Republic of Indonesia—justice and prosperity for all people. The enactment of the BAL, which independently regulated land tenure and ownership, was a milestone in the autonomy of postcolonial Indonesia. One of the effects of the law was agrarian reform, which led to most eigendom land becoming tanah negara, or state-controlled land. This eigendom land has been used for public housing, though some consider such usage to deviate from the BAL. In recent years, the issue has led to conflict between settlers of eigendom land and the municipal government of Surabaya. This article concludes that the existence of eigendom land in the postcolonial era is a reality and its impact can be seen in the form of residents being driven to oppose the government. If the law were consistent with the BAL, there would be no land with eigendom status in Indonesia. The best hope for achieving justice and welfare for the people of Indonesia, in accordance with the goals of agrarian reform, is to convert the status of all eigendom land to the types of land rights determined by BAL.

Keywords: eigendom, ownership rights, conflict, Surat Ijo, land rights conversion,

Surabaya

Introduction

Law No. 5 of 1960 Concerning the Basic Principles of Agrarian Law (Undang-Undang No. 5 Tahun 1960 tentang Peraturan Dasar Pokok-pokok Agraria, hereafter BAL) is the basis of land management policy in Indonesia. Since this law was enacted, there has been a reform in the control, ownership, and use of land in Indonesia. This has included the conversion of a colonial model of land rights (land titles) to a national one. Land rights that were in effect during the colonial period, which were based on the Agrarische Wet (Agrarian Law, hereafter AW) of 1870 and the Burgerlijk Wetboek (Civil Code, hereafter BW) of 1847, including eigendom (ownership rights), opstal (rights over buildings erected on land), erfpacht (lease rights), gebruik (use rights), and servituut (servitude rights), have been required to be converted to the types of land rights determined by the BAL, including hak milik (ownership/freehold rights, hereafter HM), hak guna bangunan (building rights, hereafter HGB), hak guna usaha (cultivation rights, hereafter HGU), hak pakai (usage rights, hereafter HP), and hak pengelolaan (management rights, hereafter HPL). The same requirement for conversion has applied to land with attached adat rights such as yasan, gogolan, pekulen, and bengkok (Parlindungan 1990, 1).

The requirement for conversion has had a number of effects, one of them being that foreign nationals who previously held colonial land rights have lost those rights; their land has fallen under the control of the state. The BAL stipulates that citizens of foreign countries are not permitted to have HM rights over land in Indonesia; they may only receive HP rights. The complicated administrative procedures involved in the conversion of colonial rights over land to HP rights has meant that most citizens of foreign countries who held eigendom rights over land decided to leave Indonesia, allowing their lands to fall under the control of the Indonesian state.

The national government has delegated authority to the regional governments to manage state-controlled land as part of the latter’s agrarian reform programs. In Surabaya the majority of state-controlled land (8,275,970.28 m2 [827.6 hectares], representing approximately 55.31 percent of the total state-controlled land in the municipality [14,963,717.29 m2/1,496.372 hectares]) is presently used for residential settlement. This includes land under HPL rights as well as land under eigendom rights. Upon this state-controlled land there are 48,200 residential plots, measuring on average 200 m2 in size. Residents of these plots are legally considered renters, holding Permission to Use Land (Ijin Pemakaian Tanah, hereafter IPT; also known as Surat Ijo [Green Certificate]) certificates for the land they occupy. They have been, to date, unable to convert this land into HM in their names, even though such conversion is allowed by law.

Since 2001, three years after the beginning of the Reformasi period, the issue of agrarian reform has again been an important theme in national discourse. This followed the enactment of the Decree of the People’s Consultative Assembly No. IX/MPR/2001 Concerning Agrarian Reform and the Management of Natural Resources (Ketetapan Majelis Permusyawaratan Rakyat No. IX/MPR/2001 tentang Pembaharuan Agraria dan Pengelolaan Sumber Daya Alam), Article 2 of which stated:

The agrarian reform involves a continuous process in which the control, ownership, and use of agrarian resources is reorganized to better ensure legal protection and certainty, as well as justice and prosperity, for all of the people of Indonesia (Pembaharuan agraria mencakup suatu proses yang berkesinambungan berkenaan dengan penataan kembali penguasaan, pemilikan, penggunaan, dan pemanfaatan sumber daya agraria, dilaksanakan dalam rangka tercapainya kepastian dan perlindungan hukum serta keadilan dan kemakmuran bagi seluruh rakyat Indonesia).

Subsequently, the National Land Bureau (Badan Pertanahan Nasional, BPN) established two formulas for agrarian reform: first, the reorganization of the legal and political land systems, based on the Pancasila, 1945 Constitution, and BAL; and second, the implementation of Land Reform Plus, the reorganization of the people’s land assets and access to economic and political resources that allow them to best use their land (Kementerian Agraria dan Tata Ruang 2014).

The first formula is directed and intended to realign the control and ownership of land in accordance with the Indonesian constitution, particularly Article 33, Subsection 3: “The land, the waters and the natural resources within shall be under the powers of the State and shall be used to the greatest benefit of the people (Bumi, air, dan kekayaan alam yang terkandung di dalamnya dikuasai oleh negara dan dipergunakan sebesar-besarnya untuk kemakmuran rakyat).” The second formula is directed and intended to alleviate poverty by providing land for distribution, as well as access to economic resources to the populace—particularly the landless, homeless, and jobless. Other goals and principles of agrarian reform are reorganizing land control and ownership policies, reducing conflict, ensuring legal certainty, respecting the rule of law, and unifying land laws (ibid.).

Based on this agrarian reform program, the municipal government of Surabaya is in the process of converting state-controlled land, both eigendom and former eigendom land, through Surabaya Municipal Bylaw No. 16 of 2014 Regarding the Release of Land Assets Held by the Municipality of Surabaya (Peraturan Daerah Kota Surabaya No. 16 Tahun 2014 tentang Pelepasan Tanah Aset Pemerintah Kota Surabaya). This municipal bylaw states that state-controlled land that is occupied by civilians can be converted, with HM rights, into their name. However, when it comes to implementation this law has not met expectations. Though it was hoped that the bylaw would ensure justice and prosperity for the settlers of state-controlled land, in accordance with the goals of agrarian reform, this has remained but a pipe dream. As of 2016, not a single settler of eigendom land had filed a request for HM rights over the land he or she presently occupied. Why is this so? This article attempts to, objectively and without promoting any agenda whatsoever, understand and explain the historical context of eigendom land in the post-independence era. Hypothesis: The continued existence of eigendom land in the postcolonial era due to inconsistencies in the implementation of the BAL has impacted social justice and prosperity by giving rise to conflict between residents of eigendom land and the municipal government of Surabaya.

Previous Studies

Civilian settlement of state-controlled land was researched by a team from the School of Land Studies, Yogyakarta. Written by Binsar Simbolon et al., the study titled “Surat Hijau di Kota Surabaya, Provinsi Jawa Timur” (Green Certificates in the municipality of Surabaya, province of East Java) uses two approaches (legal and social) to discuss the issue of Green Certificates. In its legal analysis, the study concludes that the use of the IPT system for state-controlled land settled by civilians is akin to retaining the colonial paradigm of land control and ownership, a paradigm that is not tenable in an independent Indonesia.

The research project’s social analysis concludes that the IPT system has imposed greater financial burdens on settlers, which has in turn become a source of dissatisfaction for and triggered resistance from the settlers. It also concludes that the conflict between Green Certificate-holding settlers and the municipal government of Surabaya has occurred because both sides have different understandings of the Green Certificates. At the end of its report, the research team recommends that in order to achieve better social harmony, a national land policy must be formulated that is truly free of colonial legal products. For this purpose, then, the writers urge that settlers be given HGB rights over the land they have settled, so that HM rights over this land may subsequently be granted.

An interesting finding of this report is, as mentioned above, that conflict over Green Certificate land has emerged because of different perceptions regarding the position of the land. This appears to be an oversimplification of the issue. If, as argued by the research team, the conflict is caused simply by a difference of opinion, it should be simple to resolve, as both sides need only to reach a shared understanding. The reality, however, is that both sides want to control or own the state-controlled land upon which civilians have taken residence. Thus, this conflict is a more substantial one. In this perspective, conflict over Green Certificate land is perceived as a conflict over control of land, with the settlers involved in a struggle of community. This means that the source of the conflict is the land itself and not simply different perceptions. Owing to their interest in the land, both sides develop their own different (and often opposing) perceptions.

This article, thus, attempts to understand one aspect of Green Certificate land, namely eigendom land, land that still maintains its colonial rights and has yet to be converted to rights allowed by the BAL. Eigendom land can be considered “status quo” land, which, we argue, is easier to release to civilian settlers than Green Certificate land under HP and HPL rights. Once this land has been transferred to its settlers, the latter will no longer require legal aid or protection, as noted by Agus Sekarnaji (2005). Furthermore, if the land is used as collateral at a bank, its value will increase and the calculation of its value will be simplified. As noted by Njo Anastasia (2006), if this land is converted then banks will no longer have to separately calculate the value of the land and the buildings upon it.

The Continued Existence of Eigendom Land

One interesting phenomenon in postcolonial Surabaya, a city in the province of East Java, is the continued existence of eigendom land rights. Even 55 years after the BAL was enacted, some of the land under the control of the municipal government of Surabaya remains under these colonial rights, having not been formally converted to HP or HPL rights. This has created considerable controversy and negative perceptions.

During the colonial period land laws were based on the principle of domeinverklaring, an assumption that land with no proof of ownership was owned by the state. As the ultimate owner of land, the colonial government of the Netherlands East Indies maintained the right to manage land in accordance with its own interests; this included—during the period of Governor-General H. W. Daendels (1808–11), for example—selling land and granting eigendom rights to the purchasers, who were generally capital holders or investors. These investors, the purchasers of land, were known as tuan tanah (landlords).

As holders of eigendom rights, tuan tanah were given the authority to manage their land and all who settled on it. Generally, people who lived on privately owned eigendom land had a variety of obligations, including forced labor (rodi), guarding the area at night (ronda), and crop taxes. These obligations were considered a form of service toward the tuan tanah, who acted in their own self-interest when determining obligations and ensuring that the obligations were met by the residents of the land. This determination of the types and varieties of obligations by tuan tanah is referred to as hak pertuanan (landlord rights).

The types of obligations for people living on one plot of tanah partikelir (privately owned land) differed from those of people living on another one. However, they all had the same ultimate result: difficulty for settlers, which led to a sense of dissatisfaction in society. Dissatisfaction over these injustices, which were faced over an extended period of time, often led to resistance against the tuan tanah. This could be seen in a number of cases from the period of Daendels to the beginning of the twentieth century, including the Ratu Adil, machinist, indigene, and nativist movements (Sartono 1973; 1984). In short, the existence of tanah partikelir during the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth was synonymous with entrenched injustice and served as a strong mobilizer for social resistance; this general fact held true in Surabaya as well (Diesel 1878, 237–238).

At the beginning of the twentieth century, at the dawn of the decentralization era (1903), a number of autonomous regional governments were formed, one of them being the gemeente (municipality) of Surabaya in 1906. As an autonomous regional government, it had to be able to financially support itself, and thus the gemeente promoted efforts to exploit its regional potential. One such effort was the repurchasing of the tanah partikelir within its administrative jurisdiction, such as in Keputran, Ketabang, Kupang, Pakis, and Darmo. These tanah partikelir became eigendom lands in the name of the gemeente of Surabaya (Purnawan 2011). Much of the land was then rented to the general populace, particularly sharecroppers, but some was also allocated for the construction of housing for the municipality’s residents, particularly those of European descent (Colombijn 2010). These efforts increased the income of the gemeente of Surabaya.

After Indonesian sovereignty was recognized by the Dutch in 1949—or, more specifically, after the establishment of the municipal government of Surabaya (Pemerintah Daerah Swatantra Kota Besar Surabaya) in 1950—lands owned under eigendom rights were inherited by the gemeente, which took over their management. The land’s status as eigendom land was maintained, though this is understandable as the newly independent Indonesia did not yet have its own land laws. Part of the eigendom land was settled by residents and used for housing; settlers included fighters from the National Revolution and returning refugees (Dick 2002). In 1960 the BAL was enacted. It included a requirement to convert all land rights so that they would be in accordance with the BAL. However, the reality is that there are still eigendom lands that have yet to be converted.

The BAL of 1960 forms the basis of postcolonial Indonesian land management, and its passage gave Indonesians hope that citizens—especially the homeless, landless, and unemployed—would attain prosperity and justice, for instance through the recognition of individual rights to own land (Article 21 [1]). When the BAL was passed, the AW was repealed. The BAL specifies that the state is not a landowner and thus may not hold land with HM rights. According to Article 2, Paragraph 1, of the BAL, the state is the highest organization in society. As such, it serves only to provide land, grant rights over land, and manage legislation and law relating to land (Article 2, Paragraph 2).

In theory, eigendom rights over land should have already expired and thus are void. All such land rights should have already been converted to rights recognized by the BAL (Decree of the Minister of Agrarian Affairs No. 9 of 1965 Concerning the Conversion of Usage Rights and Management Rights, or Peraturan Menteri Agraria No. 9 Tahun 1965 tentang Konversi Hak Pakai dan Hak Pengelolaan). Eigendom rights over land should have been converted to HPL or HP rights. However, there are still plots of land with eigendom rights, be they in the name of the gemeente or tuan tanah; such land has not yet been registered or its rights converted in accordance with the BAL at the regional office of the BPN (see Tables 3 and 4 in the next section).

This conversion process, if permitted, can be considered to be the nationalization or Indonesianization of land rights. Such a process should be completed entirely, without exception; in other words, all remaining colonial land rights must be converted into Indonesian rights in accordance with the BAL. This position has been taken also by legislation issued after the BAL. For instance, the Decision of the Minister of Agrarian No. 12/KaJ1963 Concerning the Conversion of Land Rights (Keputusan Menteri Agraria No. 12/KaJ1963 tentang Konversi Hak Atas Tanah) mandates that all opstal and erfpacht rights over municipally owned eigendom land must be converted to HGB or HGU rights.

Despite such provisions, the conversion process was neither absolute nor immutable. It could be modified depending on the use of the land. Land with opstal rights for buildings, for instance, could be converted to HGU rights if there was a change in its purposing in accordance with the municipal master plan; such land could then be used for agriculture. Erfpacht rights could be converted to HGB rights if there was a change in purposing, such as for housing. The lenient nature of this conversion also allowed the continued existence of eigendom land rights, the highest land rights possible under the colonial system; these rights appear to have been maintained by the municipal government of Surabaya as the holder of HPL rights over the land.

Subsequently, the Decree of the Minister of Agrarian Affairs No. 9 of 1965 was enacted; it mandated that controlling rights (beheer rechts) over land be converted to HPL rights. Before then, beheer rights had been converted to controlling rights (hak menguasai). Since 1965 regional governments have been managing rights (HPL). The changing terminology was considered more specific and operational. Meanwhile, cities’ erfpacht, opstal, and eigendom rights were to be converted to HGB rights for the buildings situated upon land with HPL rights (Ali 2004).

Eigendom Land under the Control of Surabaya Municipality

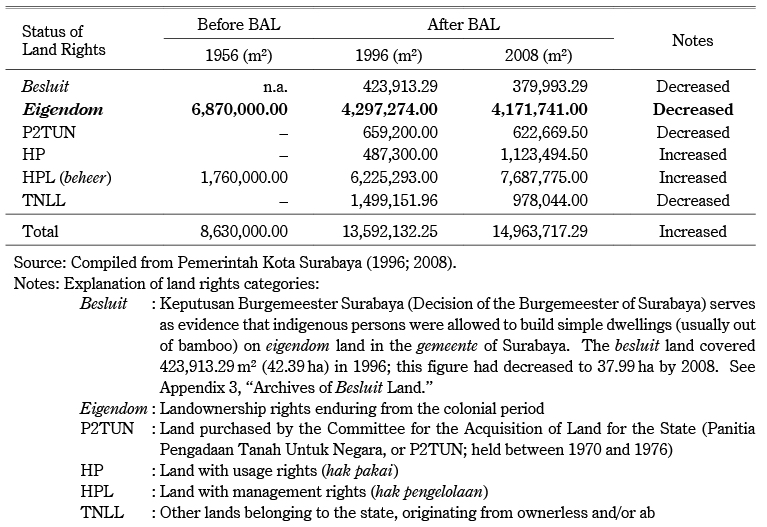

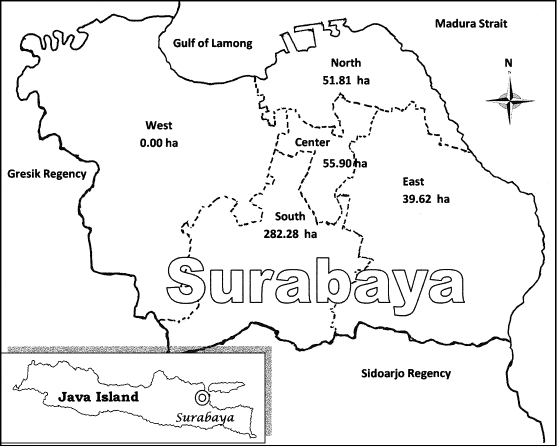

The total area of state-controlled land in the municipality of Surabaya is 14,963,717.29 m2 (1,496.37 ha), approximately 4.58 percent of the city’s total area (326.81 km2/32,681 ha). On top of this state-controlled land lie approximately 48,200 parcels of land occupied by civilians. To date, land with eigendom rights represents the second-most common type of state-controlled land, after land with HPL rights. The division of land by area is as shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Area of State-Controlled Land Based on Category of Land Rights

As time has passed, the amount of eigendom land has decreased as a result of continued land conversion to and registration of rights provided by the BAL. The total amount of eigendom land, which was 6,870,000 m2 (687 ha) in 1956, decreased to 4,297,274 m2 (429.73 ha) by 1996 and 4,171,741 m2 (417.17 ha) by 2008 (Pemerintah Kota Surabaya 1996; 2008). This indicates that the conversion of eigendom land to land under HP and HPL rights has occurred, albeit slowly: in the 12 years between 1996 and 2008, only 125,533 m2, or 12.55 ha, was converted.

Conversely, the total amount of land with HPL rights has increased, from 176 ha of land with beheer rights in 1956 to 768.78 ha of land with HPL rights by 2008 (see Table 1). This indicates that the land conversion and nationalization process continues, though older land rights continue to exist (see Appendix 1). This has led several elements of Surabaya society to question the reason for the delay in the conversion of eigendom land.

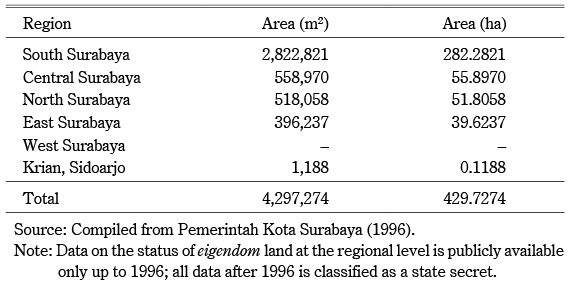

Generally, eigendom land is divided into relatively large plots. Most of the plots are more than 10,000 m2 (1 ha) in area, though some are smaller. There are even plots of former eigendom land covering more than 100 ha. Most of the former eigendom land is located in the center of the municipality of Surabaya, a very densely populated region (the average population density for Surabaya was 10,047 in 1980; 10,126 in 1990; 7,966 in 2000; and 8,463 in 2010). The highest population density, reaching up to 20,000 people/km2, is in the center of the city, such as in the districts of Bubutan, Simokerto, Kenjeran, Tambaksari, and Sawahan. The division of eigendom land can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2 Division of Eigendom Land Based on Region

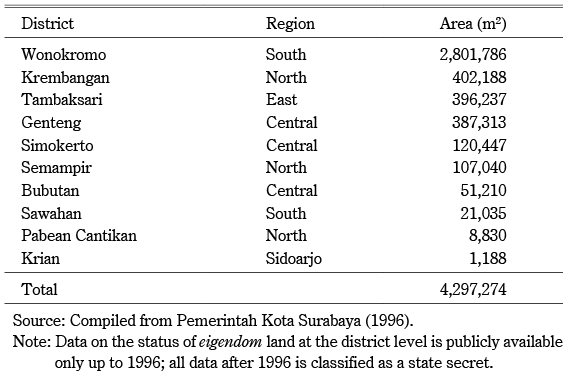

The eigendom land in Surabaya consists of 49 plots, covering an area of 429.73 ha (see Table 2). The greatest amount of former eigendom land, consisting of 280.18 ha or more than 65 percent of the total eigendom land in Surabaya, is located in Wonokromo District. The smallest amount of eigendom land—0.88 ha—is located in Pabean Cantikan District, North Surabaya. The division of former eigendom land by district is presented in Table 3.

Table 3 Division of Eigendom Land by District (Kecamatan)

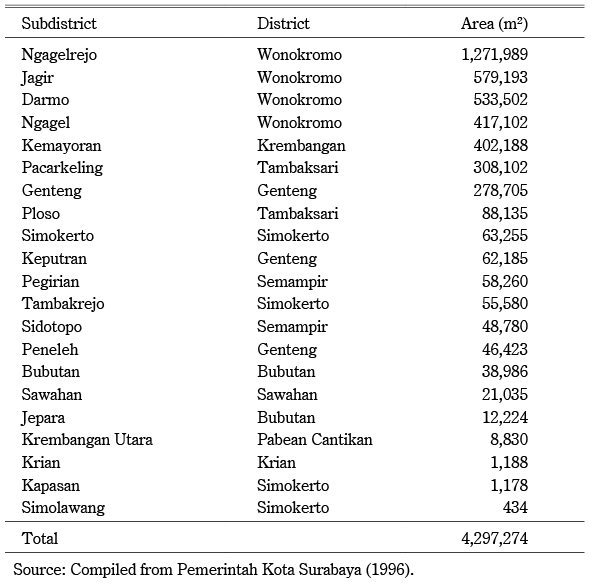

At the subdistrict level, the greatest amount of former eigendom land, consisting of 127.2 ha, or approximately 30 percent of the total eigendom land in Surabaya, is found in Ngagelrejo Subdistrict, Wonokromo District. It is followed by Jagir, Darmo, and Ngagel Subdistricts, all of which are administratively part of Wonokromo District. The smallest amount of eigendom land, 0.04 ha, is found in Simolawang Subdistrict, Simokerta District, North Surabaya. Thus, the greatest amount of eigendom land is located in South Surabaya. The total division of former eigendom land by subdistrict is presented in Table 4.

Table 4 Division of Eigendom Land by Subdistrict (Kelurahan)

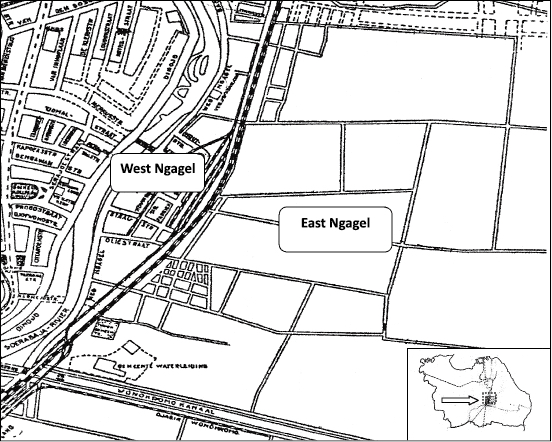

Some of the land that was controlled, owned, or managed in colonial times by the gemeente of Surabaya includes Goebeng (East and West), Ngagel (East and West), Boeboetan, Ketabang (East and West), Darmo III, Boejoekan, Westerbuitenweg, Assemdjadjar, Tembok Doekoeh, Plosogede, Sidotopo, and Darmo II (Fuchter 1941, 218–220).

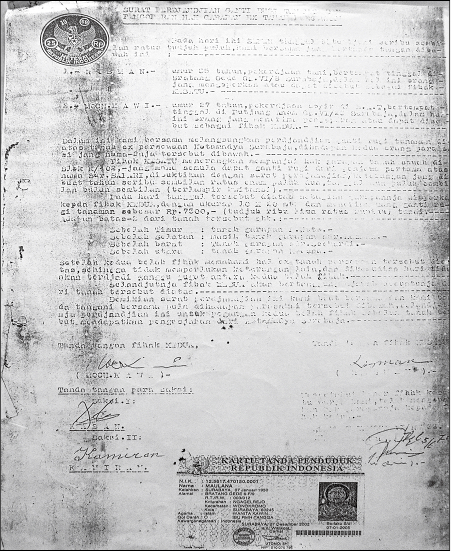

For example, the land in Ngagel East (the portion of Ngagel to the east of the railroad tracks) was rented out (grondhuur) for several purposes, including for indigene agricultural activities (Inhemsche Landbouw), oil drilling (grondboringen) by the BPM (Bataafsche Petroleum Maatschappij, Batavian Petroleum Company), N. V. Melk Centrale, and for use by ethnic Dutch and Chinese entrepreneurs (ibid., see Appendix 2). Ngagel East has become a densely populated residential area, as evidenced by such areas as Ngagelrejo, Bratanggede, Ngagelmulyo, Bratang, Bratang Binangun, Ngagel Jaya, Ngagel Tama, Krukah, Ngagel Dadi, Baratajaya, and Pucangsewu. According to residents of this district, they settled the land after purchasing it from farmers, with a zegel certificate (see Appendix 4) as proof (Interview with Supadi H.S., March 17, 2016, Surabaya).

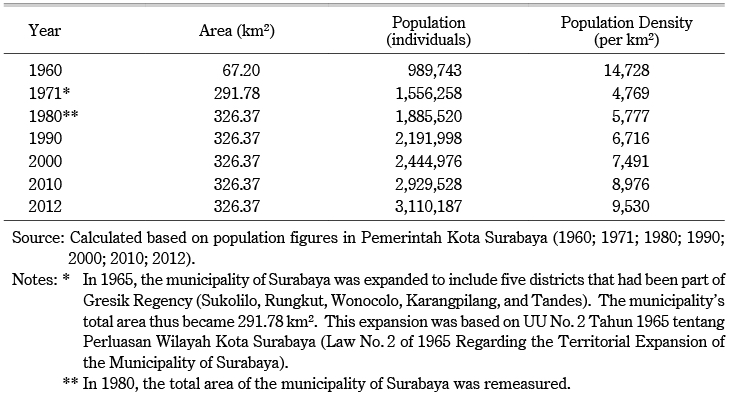

Why did the farmers (as holders of HGU rights, converted from Western rights, in Ngagel East) sell the land they were supposed to cultivate? The master plan of the municipality of Surabaya was intended to develop Surabaya into an “INDAMARDI” (INdustri, perDAgangan, MARitim, dan penDIdikan [Industry, trade, maritime, and education]) municipality (Soekotjo 1968, 4–5), and as a result it prioritized industrial development. This was in accordance with the perceived conditions and potential of the time—namely, the numerous factories and other industries that remained from the colonial period. The development of the industrial sector required much labor, which led to an uncontrolled surge of would-be laborers migrating from rural areas into urban Surabaya. This migration, in turn, led to a sudden increase in the municipality’s population, population density, and housing requirements (see Table 5). Efforts were made to resolve the issue by converting rice fields into residential areas and factories. Importantly, the residential area of Ngagel East is located between the old industrial district of Ngagel West and the new industrial district of Rungkut, one of the largest industrial districts in Surabaya and East Java.

Table 5 Area, Population, and Population Density (per km2) of the Municipality of Surabaya, 1960–2012

Birth of IPT System

The continued existence of eigendom land has led to a number of issues, both manifest and latent. The once-spacious eigendom land, which predominantly originated as tanah partikelir, has since been developed into densely populated residential areas.

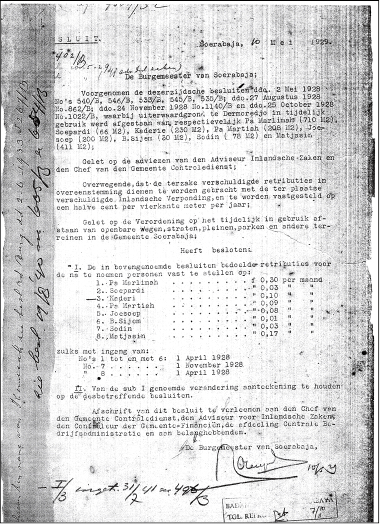

After the 30 September Movement coup (1965), residents living on land under pre-BAL titles received legal recognition as renters of eigendom land. Based on the Decree of the Minister of Agrarian Affairs No. 1 of 1966 Concerning the Registration of Usage Rights and Management Rights, in Surabaya the use of eigendom land has been granted to third parties, particularly those who were previously homeless. Before 1966 these homeless persons tended to unlawfully occupy land, but settlers of eigendom land were given legal recognition as renters by the Decision of the Regional Representatives’ Council for Mutual Assistance of Surabaya No. 03E/DPRD-GR KEP/1971, Dated 6 May 1971, Concerning Land Rental (Keputusan DPRD Gotong Royong Kotamadya Surabaya Nomor 03E/DPRD-GR KEP/1971 tertanggal 6 Mei 1971 tentang Sewa Tanah). It is possible that the municipal government of Surabaya at the time was so preoccupied with the issue of land rental that it neglected to register or convert eigendom land with the Land Bureau. The government may have likewise forgotten that according to the BAL, regional governments were not permitted to own land with eigendom rights and could not continue to rent out land as had been done during the colonial era.

Subsequently, in 1977 the municipal government of Surabaya enacted the Permission to Use Land system. With this new system, the settlers of eigendom land were given a legal document, the IPT certificate, granting further recognition. However, this system also positioned the settlers as renters of state-controlled lands, requiring all settlers of state-controlled land—including land with eigendom rights—to pay retribution. The legal basis for this system was the Surabaya Municipal Bylaw No. 22 of 1977 Concerning the Use and Retributions for Land Managed by the Municipality of Surabaya (Peraturan Daerah Kotamadya Daerah Tingkat II Surabaya No. 22 Tahun 1977 tentang Pemakaian dan Retribusi Tanah yang Dikelola oleh Pemerintah Kotamadya Daerah Tingkat II Surabaya).

The legal recognition of settlement on eigendom land may be considered part of a 1975 program to clarify the status of municipal land. According to several settlers, all the settlers were initially told to gather their proofs of sale for the land that they occupied, so that the documents could be given to the municipal government of Surabaya. At the time, rumors spread that these proofs of sale would be replaced with HM certificates. Whoever refused to surrender the documents would be branded a former member of the forbidden Communist Party of Indonesia (Partai Komunis Indonesia, PKI), a possibility that terrified residents. As such, not a single resident refused to surrender the proof of purchase for the land that he or she occupied. A few years later, IPT certificates (Green Certificates)—essentially, renters’ certificates—were issued. Effectively, this government program was a means for the municipal government of Surabaya to take control of the eigendom land.

This IPT system has allowed eigendom rights to endure, though administratively such land is listed as land under the management of the state. The IPT system used in Surabaya is not based in the BAL (Surabaya Municipal Bylaw No. 12 of 1994) and can thus be considered not based in law, or even illegal. The creation of such a land system is controversial, as it appears symptomatic of a “State within a State” (Ratna and Indriayati 2011).

Effects of the Continued Existence of Eigendom Land

The continued existence of eigendom land has created several negative effects. First, from a legal perspective, the continued existence of eigendom land deviates from the BAL. The deviancy is exacerbated by the enactment of the IPT system; eigendom rights over such land cannot be converted to HM rights by the land’s settlers. According to the Government Regulation No. 24 of 1997 Concerning Land Registration (Peraturan Pemerintah No. 24 Tahun 1997 tentang Pendaftaran Tanah), eigendom land settled by private citizens can be converted to HM by its settlers. More specifically, eigendom land with an area of no more than 600 m2 that has been continuously settled by the same individual for a minimum of 20 years can be converted to HGB; the settler may then apply for the land to be certified HM.

Most of the settlers of eigendom land who were interviewed for this study expressed their disappointment that when applying for an HM certificate at the BPN they were required to present a letter of recommendation from the municipal government of Surabaya, which has authority over and manages the eigendom land. This requirement is non-negotiable, yet in practice the municipal government of Surabaya has never issued a letter of recommendation; instead, it offers a plethora of reasons for not doing so: for instance, the government may state that as the holder of HPL rights, it must carefully maintain the land and ensure that it is not accused of losing state-controlled land. As a result, the settlers never meet the administrative requirements of the BPN, and thus the bureau never processes their applications. This situation is exacerbated by the fact that some settlers’ groups have received HM rights over their land with a special disposition (explained further below). As a result, the (considerably more numerous) settlers who have been unsuccessful in obtaining an HM certificate feel discriminated against. This, thus, is a form of injustice experienced by settlers, who have begun expressing the belief that the municipal government of Surabaya is deliberately ensuring that eigendom land remains within its control.

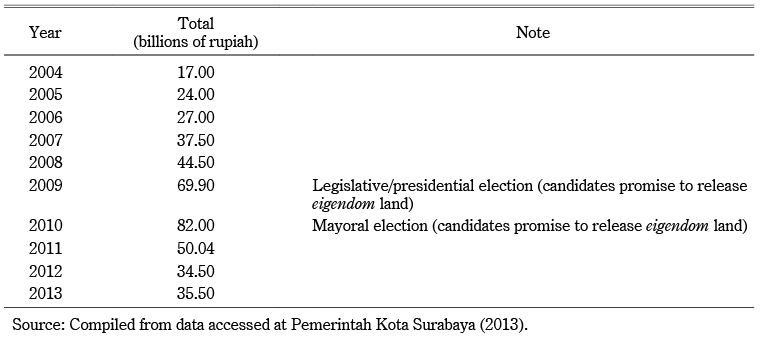

Second, from a political perspective, the settlers of eigendom land become political objects every five years. In the lead-up to the general and mayoral elections in Surabaya, the settlers are consistently targeted by legislative and mayoral candidates. Their campaign promise is the same: the release of eigendom land under HM rights to the settlers. In such situations, the settlers are deceived by the promises and vote for the candidates. However, the election promises are never kept, and the promised land releases have never been carried out. Numerous excuses have been given, such as legislative obstacles, fear of being accused of losing state property, and fear of being accused of corruption. This has occurred regularly on a five-year cycle. In turn, it has led to a decrease in the amount of retributions received by the municipal government of Surabaya, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6 Total Income, Retributions from Land Held under Green Certificates, 2004–13

Third, from an economic perspective, settlements on eigendom land have little value in comparison to land with HM rights. As a consequence, it is difficult to use eigendom land as collateral for capital loans at a bank; only certain banks will accept it, and even then the land is valued only for the buildings on it. Thus, banks value eigendom land at an unfair or substandard level.

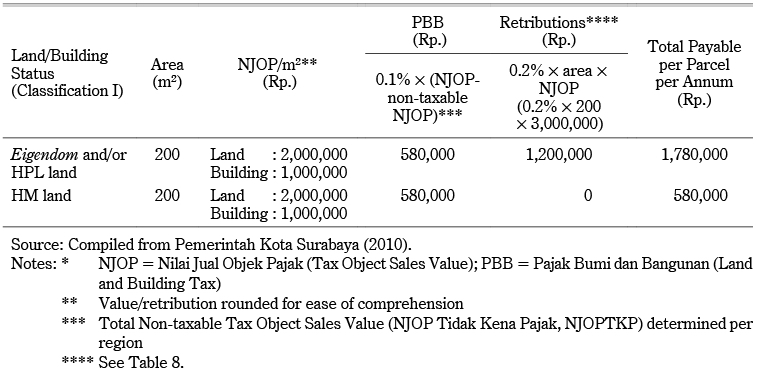

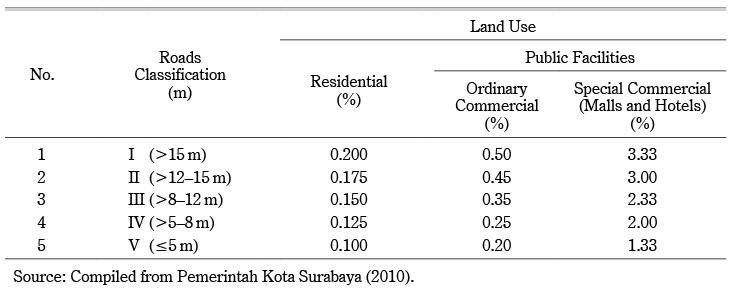

Furthermore, as mentioned above, the continued existence of eigendom land is a financial burden on its settlers, who must pay land and building taxes on top of municipal retributions. The total retribution and land and building taxes owed are based on the area of land held and its location; settlers of parcels located near main roads must pay more than those in the kampung or alleys. The total retribution and land and building taxes owed on parcels located near main roads can reach Rp.1 million to 5 million a year, whereas the retribution and taxes on parcels located in the kampung or alleys average Rp.300,000 to 1 million a year. The total amount of retributions paid to the municipal government of Surabaya varies. It is usually equal to the land and building taxes that are paid to the state, but it may be higher.

Table 7 shows the different financial burdens borne between settlers of eigendom land and residents with HM rights over their land, assuming that both parcels are located along a Class I road that is 15 meters in width and are the site of buildings of equal value. If a settler opens a shop, the total amount of retributions increases because the land is then categorized as commercial. Calculated at 0.5% × 200 m2 × Rp.3,000,000 = Rp.3,000,000 (see Table 8), this means that the total amount of land and building taxes and municipal retributions paid is Rp.3,580,000. This has thus led the people of Surabaya to believe that it is more expensive to live or do business on eigendom land than on land with HM rights. Consequently, the market value of eigendom land is lower than (sometimes half of) land with HM rights, even when the Tax Object Sales Value is the same.

Table 7 NJOP, PBB, and Retributions for Lands with Eigendom and HM Rights*

Table 8 Percentage Used to Calculate Retributions for IPT

As such, residents living alongside Class I roads (width > 15 meters) prefer to open their businesses elsewhere, either renting another location or finding eigendom land located on a Class V road (width ≤ 5 meters), where retribution rates are lower (0.1 percent). The businesses may include small shops, laundry services, motorcycle and tire repair shops, cheap boarding houses, and other businesses that do not require a business permit from the municipal government. Residential districts that have been developed as business districts by their residents have been designated districts for commercial public facilities by the municipal government of Surabaya. Land designated for public facilities is firmly prohibited from being converted to HM status in the name of private citizens, and as such the difficult economic situation has only reinforced the municipal government of Surabaya’s status as the manager of eigendom land. However, it can be stated objectively that the continued existence of eigendom land has quashed the spirit of entrepreneurship among the settlers.

Fourth, from a social perspective, the existence of eigendom land has created new social groups within society, namely, groups or communities of residents of land with Green Certificates. The social position of such groups is lower than that of groups of residents living on land with HM rights. Settlers of eigendom land are considered second-class citizens, residents of the city lacking recognition, or even stepchildren with greater obligations than biological children.

Fifth, from a cultural-psychological perspective, settlers of eigendom land suffer from poor self-esteem as a result of being considered second-class citizens. This is evident when they are faced with city residents who live on land with HM rights, who may be called “true” residents of the city. The settlers feel as though they are sleeping in a rented room or house, one that does not belong to them. At any time they can be evicted by the government in the name of public interest without compensation. As such, we must ask: Can the settlers be considered prosperous? It is important to note that the majority of residents of eigendom land with IPT certificates are elderly, older than 70 years of age, and mostly received low wages while they were working—either equal to or lower than the regional minimum wage (approximately Rp.3.5 million a month). It would thus be beneficial to them if they received a measure of certainty over the remainder of their lives with HM rights over their land, as long as it was realized with a simple procedure, affordable compensation, and effective legal protection.

Based on the above discussion, it can be stated that eigendom land rights, a remnant of the colonial government, have affected all aspects of the lives of certain segments of Surabaya society. In other words, the continued existence of eigendom land is synonymous with the continued existence of social injustice and a lack of prosperity. Preserving eigendom land rights means preserving injustice and tending to the seeds of future land disputes.

It should be noted that the word “injustice” is used here to mean injustice in one’s rights and obligations to the land upon which one lives. As explained above, settlers of eigendom land must pay two forms of taxation for the land (see Table 7). These two financial obligations are considered unjust by the settlers; if they were renters on land with HM rights they would only need to pay their rent, whereas if they were holders of HM rights over land they would only be required to pay the Land and Building Tax. Their current financial situation is exacerbated by their inability to convert the land, and as such they may feel abused.

The concept of prosperity here, meanwhile, is to be understood in the sociocultural context of Java, in which ownership of land and a home is the basis for one’s existence in the community. For Javanese people, someone who does not own any land or a house cannot be considered a true member of the community, or even a person at all. The landless are often ignored by people with HM rights over their land; frequently, they are not invited to neighbors’ celebrations, asked to participate in village discussions, required to participate in gotong royong/mutual aid work, pay neighborhood dues, etc. The landless can be termed, using George Simmel’s categorization, as “the stranger” (Mead 1934) in the community. Thus, in the Javanese sociocultural context, settlers of eigendom land struggle to obtain HM rights over the land they occupy so that they may be recognized and respected by the community. Prosperity, thus, should be understood as a certain satisfaction obtained from fulfilling the community’s demands; owning land with HM rights gives settlers greater respect than occupying land owned by another party.

Furthermore, the people of Java abide by the following motto regarding landownership: “sadumuk bathuk sanyari bumi, tak belani nganti pecahe dhadha lan wutahing ludiro [Though it is but a narrow strip of land, I will defend it until my chest bursts and blood seeps out (i.e., until I die)].” This Javanese cultural norm has, to some extent, influenced the settlers in their struggle to gain HM rights over eigendom land.

The struggle is influenced also by the BAL’s assurance that HM rights are “rights to land which are inherited, the strongest and fullest [rights] that one can hold over land (sebagai hak atas tanah yang turun-temurun, terkuat dan terpenuh yang dapat dipunyai orang atas tanah)” (Article 20). In other words, HM rights are not of limited duration, and land may be freely used or purposed by its owner so long as the usage/purposing does not conflict with the public interest (Boedi 1968).

Based on the above factors and supported by the increasingly open/democratic socio-political situation after the beginning of Reformasi, settlers of eigendom land have begun to fight for the land they occupy. It began with some settlers refusing to pay their IPT retributions. This act of protest was soon followed by other settlers. Despite avoiding their retributions, all settlers of eigendom land continued paying their Land and Building Taxes. This was followed by the establishment of organizations such as GPHSIS (Gerakan Pejuang Hapus Surat Ijo Surabaya, Fighters for the Elimination of Green Certificates in Surabaya Movement), later renamed PMPMHMT (Perhimpunan Masyarakat Peserta Meraih Hak Milik Tanah, Association of People Seeking Ownership Rights over Land), which held several open meetings and shows of force and provocation, including a mass action in front of City Hall demanding the conversion of eigendom land. This organization has been supported by legal thinkers and academics as well as legal practitioners, retired soldiers, retired civil servants, and others with an interest in eigendom land. Among the organizers are retired staff of the municipal government of Surabaya and the East Java branch of the BPN who before retirement worked to maintain the status of eigendom land.

In 2007 groups of settlers of eigendom land in the Jagir, Ngagelrejo, Baratajaya, and Perak Barat Subdistricts filed a legal challenge against the municipal government of Surabaya over the eigendom land at the state court of Surabaya. All of their demands were rejected by the court, including their appeal to the provincial court of East Java. The residents took their legal battle to the Supreme Court of Indonesia in Jakarta, but their demands were again rejected. Notably, the residents of Baratajaya were successful in a Supreme Court claim in 2010, but this victory was short-lived as in 2012 the decision was reversed after the municipal government of Surabaya demanded a reexamination (Peninjauan Kembali, PK).

The settlers’ struggle for rights over eigendom land has impacted the performance of the municipal government of Surabaya, both as a disturbance and as an inspiration. In 2014, the government enacted the Surabaya Municipal Bylaw No. 16 of 2014. This was followed by the Surabaya Mayoral Decree No. 51 of 2015 Regarding the Process for Releasing Land Assets Held by the Municipality of Surabaya (Peraturan Walikota Surabaya No. 51 Tahun 2015 tentang Tata Cara Pelepasan Tanah Aset Pemerintah Kota Surabaya) in 2015. Though these regulations have yet to be implemented, they may be considered a response to settlers’ hopes for eigendom land.

Halfhearted Nationalization of Land Rights

The conversion of Western land rights into rights recognized by the BAL has been a consequence of, or rather a legal obligation established by, the BAL. As explained above, all rights that applied during the colonial period and were based on the AW and BW were required by law to be converted into one of the new nationalized land rights. Land for which these criteria were not met was converted, on September 24, 1980, into state-controlled land.

In such cases the conversion of eigendom land depended on the future use of the land, in accordance with the municipal master plan. Eigendom land belonging to the regional government was likewise registered under the name of a government institution, either national or regional. As explained above, the BAL only provides the government with the authority to decide the use of land and to grant rights over the land.

Where such rights could still be found, the land’s status was simply “maintaining the status quo,” and thus the conversion of rights depended on the purposing of the land: be it for the public interest, the former holder of eigendom rights, or private citizens who had occupied or cultivated it. If land is to be used for the public interest, it must be registered with HPL rights; and the former eigendom rights holder and/or present settlers may not attempt to register for rights over it. If the land is not needed for the public interest, the former holder of eigendom rights over the land may apply to regain rights over it. If the state and former holder of eigendom rights over the land do not require it, the land’s settlers may request HM rights at the municipal/regency BPN office.

Furthermore, eigendom land can be used to increase regional own-source revenue. Since the enactment of the IPT certificates, the highest retributions were received in 2010—Rp.85 billion. Since the majority of settlers began refusing to pay retributions in 2012, the amount received by the municipal government averages Rp.30 billion to 35 billion rupiah annually (see Table 6). However, the continued existence of eigendom rights over land also reflects a concern for possible loss of landownership. After conversion, eigendom land may not be granted HM status in the name of the municipal government of Surabaya; it may only be granted HP and/or HPL status, both of which are lower in degree than HM.

A baffling development is the existence of HM landownership certificates for homes located on eigendom plots of land. This can be found, for instance, in the housing development of Jagir Sidomukti IX (150 homes), and at Ngagel Jaya Tengah (16 homes) and Wonorejo III Streets (1 home) (Observations and direct reports with settlers, April 14, 2015). In the case of Jagir Sidomukti IX, residents of the housing development received their HM certificates following a long and complicated process that lasted from 1987 until 1999. Before jointly filing their request for HM status over the land at the Surabaya branch of the BPN, the residents jointly paid retribution to the original landowner, an Indonesian citizen of Chinese descent. The total amount paid by each family to obtain HM status was only Rp.575,000. Meanwhile, the HM certificates for Ngagel Jaya Tengah and Wonorejo III Streets were obtained owing to the special status of the settlers, who were all former bureaucrats in the municipal government of Surabaya. This phenomenon indicates the existence of exceptions for—or special treatment of—certain parties, resulting in inequality and injustice in the management of eigendom land.

The phenomenon of continued existence of eigendom land can also be understood as an inconsistency in the management of eigendom land within the framework of Indonesia as a sovereign state with its own land law, or as a violation of the most fundamental land law in Indonesia, the BAL. Whether it is accepted or not, profitable or not, all management of eigendom land must be based on the BAL, particularly since the role and position of the government in managing eigendom land, as a form of state-controlled land, is already clearly defined: the government handles the provision of land, grants rights over land, determines the relationship between society and land, and arranges the legal framework for land issues. This is explicitly stated in Article 2, Paragraphs 2–7, of the BAL. Owing to its position, the state—in this case, the central and municipal governments—should serve as a role model for legislative obeisance.

Legislative obeisance in the management of land is necessary to ensure justice and prosperity for the people of Indonesia. In the management of land, according to the BAL, no parties should be granted special privileges, be they individuals, groups, or institutions. The continued existence of eigendom land has led to a social jealousy of sorts, or even a legal jealousy, among certain groups, particularly among settlers of eigendom land who are unable to convert their land. In accordance with Presidential Decree No. 32 of 1979 Concerning Policy Fundamentals in Granting New Land Rights by Converting Western Rights (Keputusan Presiden No. 32 Tahun 1979 tentang Pokok-pokok Kebijaksanaan dalam Rangka Pemberian Hak Baru atas Tanah Asal Konversi Hak-hak Barat), settlers of former eigendom land may be granted HM rights. There are at least two articles in the decree that could be the basis for such conversion:

In the case of land under Western rights that was converted to state land with HGU status and was appropriate for agriculture or residential purposes, new rights would be given to the occupants of the land (Tanah-tanah Hak Guna Usaha asal konversi hak Barat yang sudah diduduki oleh rakyat dan ditinjau dari sudut tata guna tanah dan keselamatan lingkungan hidup lebih tepat diperuntukkan pemukiman atau kegiatan usaha pertanian, akan diberikan hak baru kepada rakyat yang mendudukinya). (Article 4)

Where residential land is under HGB and HP rights that were converted from Western rights and has since become housing for the general populace, priority will be given to those people who have already occupied it after certain criteria are fulfilled, as related to the interests of the land rights holder (Tanah-tanah perkampungan bekas Hak Guna Bangunan dan Hak Pakai asal konversi hak Barat yang telah menjadi perkampungan atau diduduki rakyat, akan diprioritaskan kepada rakyat yang mendudukinya setelah dipenuhinya persyaratan-persyaratan yang menyangkut kepentingan bekas pemegang hak tanah). (Article 5)

If land formerly under Western rights can be converted into HGU, HGB, and HP rights in the name of the former rights holder, but the land is presently occupied/cultivated by others, according to this presidential decree new rights are to be granted to the land’s settlers and/or cultivators. Former rights holders should be understood as the holders of Western rights over land, be they Indonesian citizens, foreign citizens, legal bodies, or the local government (gemeente).

This decree was followed by the Decree of Minister of Domestic Affairs No. 3 of 1979 Regarding the Stipulations for the Request for and Granting of Land Rights over Land Formerly under Western Land Rights (Peraturan Menteri Dalam Negeri No. 3 Tahun 1979 tentang Ketentuan-Ketentuan Mengenai Permohonan dan Pemberian Hak Atas Tanah Asal Konversi Hak Barat). Article 10, Paragraph 1, states:

Where land formerly under HGU rights is cultivated/occupied by another party, as meant in Law No. 51/Prp/1960, and is, according to technical considerations regarding the utilization of the land and the regional development plan, appropriate for residential or agricultural use, new rights will be given to those who meet the criteria of the applicable agrarian law, so long as the land involved is not needed for projects promoting the public interest (Tanah-tanah bekas Hak Guna Usaha yang digarap/diduduki pihak lain sebagai yang dimaksud dalam Undang-Undang Nomor 51/Prp/1960 dan yang menurut pertimbangan-pertimbangan teknis tata guna tanah serta rencana pembangunan di daerah yang bersangkutan dapat dijadikan tempat permukiman penduduk atau usaha pertanian, akan diberikan dengan sesuatu hak baru kepada mereka yang memenuhi syarat menurut peraturan perundangan agraria yang berlaku, sepanjang tanah yang bersangkutan tidak diperlukan untuk proyek-proyek bagi penyelenggaraan kepentingan umum).

These presidential and ministerial decrees are sufficient legal basis for the conversion of rights over eigendom land in Surabaya, as well as land under other Western rights that is presently settled by civilians.

For social justice and prosperity to be ensured for the people of Indonesia, the conversion and registration of land should be done without differentiating between individuals, groups, and organizations. For this to be achieved, the BAL, as the basis for the management of land in Indonesia, must be upheld entirely, not halfheartedly. The Indonesianization or nationalization of land should be a wholehearted endeavor. If this is not realized, then the agrarian reform will continue as it has before—halfheartedly.

Transfer of Land Rights Holdings

Since the enactment of the BAL, eigendom land in areas such as Jakarta, Bandung, Bogor, Cirebon/Indramayu, Semarang, and Malang has been fully converted. The conversion of eigendom land in the municipality of Malang, for instance, was completed in 2012. A total of 4,230 parcels of land, each measuring approximately 200 m2 in area, were transferred to their settlers and converted to HM rights in their settlers’ names. During the conversion process, settlers were required to pay retribution to the state totaling 10 percent of the value of the land or the Tax Object Sales Value. As such, the land was released through exchange, what may be termed ruislag in the Indonesian legal system. This transfer process was completed in accordance with the Decree of the Minister of Agrarian Affairs/Head of the National Land Bureau No. 9 of 1999 Concerning the Procedure for Granting and Annulling Rights over State-Controlled Land and Managing Rights (Peraturan Menteri Negara Agraria/Kepala BPN No. 9 Tahun 1999 tentang Tatacara Pemberian dan Pembatalan Hak Atas Tanah Negara dan Hak Pengelolaan), Article 9 of which clearly states that it is possible for private citizens to request ownership rights over eigendom land.

The municipality of Malang’s successful experience with the release of eigendom land in its jurisdiction could serve as a model or inspiration for efforts to release eigendom land in Surabaya; in other words, the municipal government of Surabaya could use as examples other municipalities that have previously transferred eigendom land to their residents.

After 15 years (1999–2014) of fighting for the right of settlers of eigendom land in Surabaya to legally own the land upon which they live, there appear to have been results. Presently a municipal bylaw, Surabaya Municipal Bylaw No. 16 of 2014 Regarding the Release of Land Assets Held by the Municipality of Surabaya, is being discussed and drafted. It deals with the issue of the transfer of state-controlled land and has received the approval of the governor of East Java (Tribun News 2015). Some of the provisions for land to be transferred, according to this bylaw, are:

a. The maximum land area is 250 m2

b. The land must have been continuously occupied/settled for more than 20 years

c. The IPT certificate must still be valid, and retributions must be actively paid

d. If two plots of land are held, only one may be converted

e. Only residential land may be converted

f. Citizens are required to pay retribution in the amount of 100 percent of the Tax Object Sales Tax to the Municipal Government of Surabaya.

For settlers of eigendom land, points (a) through (e) are not an issue since most of the plots of land that they inhabit measure approximately 200 m2 in area and have been occupied continuously for at least 20 years. Their problem is with the provision in point (f): all settlers have stated their objection to the amount of restitution they are being required to pay to the state. Observations of the market price of land in Surabaya conducted in 2015 show that land is very expensive, between Rp.3 million and 25 million per square meter, or approximately Rp.600 million to 5 billion for a plot of land measuring 200 m2. Though the Tax Object Sales Value is generally lower than the market price (see Table 7), the majority of settlers feel incapable of paying it in full, even if they are helped by being allowed to, for instance, pay in installments over a given period of time (Interview with Bambang Sudibyo, 2015).

The provision regarding the total amount of retributions to be paid as compensation to the state was decided entirely by the municipal government of Surabaya without any prior discussion with the settlers of the eigendom lands. From a judicial-factual perspective, the municipal government of Surabaya cannot be blamed for this decision, as it is the holder of HPL rights over the eigendom land. However, this provision was not expected by the settlers and, unsurprisingly, has become an obstacle to the transfer of land rights to private citizens. Many of the settlers stated that they would rather buy new land elsewhere, at a cheaper price, than pay such expensive compensation; this opinion was held even by settlers capable of paying the demanded retribution (Interviews with residents of settlements such as Sunari, Soebandi, and Suradi, March 2015). The current deadlock indicates that there is a flaw in the conversion process: namely, a provision considered unacceptable by the general populace. Now the general populace can only hope that the Surabaya Municipal Bylaw No. 16 of 2014, which has already received the approval of the governor of East Java, can be reexamined or revised.

Defect of Municipal Bylaw and Deadlock

The manner through which eigendom rights over land controlled by the state can be transferred is prescribed by Subchapter XII.1 of the Decree of Minister of Domestic Affairs No. 17 of 2007 Regarding the Technical Guidelines for the Management of Regional-Owned Assets (Peraturan Menteri Dalam Negeri No. 17 Tahun 2007 tentang Pedoman Teknis Pengelolaan Barang Milik Daerah). The transfer of rights can take several forms: (i) sale, (ii) exchange, (iii) grant, and (iv) equity capital. Meanwhile, Subchapter XII.3 states that the release of regional governments’ lands and buildings can be done in two manners: through (i) release, involving compensation (purchase); and (ii) exchange. Of these, the Surabaya Municipal Bylaw No. 16 of 2014 prescribes release with compensation, which may also be considered the sale of state assets, as during the transfer process residents are required to pay 100 percent of the Tax Object Sales Value.

The Ministry of Agrarian and Spatial Planning/National Land Bureau (new titles of the Ministry of Agrarian Affairs/National Land Bureau) cannot be ignored or excluded from this release process. Likewise, the Ministry of Domestic Affairs must actively involve itself and is forbidden from not doing so; as such, there must be coordination between the two ministries during the land release process.

According to the Decree of the Minister of Agrarian Affairs/Head of the National Land Bureau No. 9 of 1999 Concerning the Procedure for Granting and Annulling Rights over State-Controlled Land and Managing Rights, the granting and/or annulling of rights over state-controlled lands is the responsibility of the minister (Article 3, Paragraph 1). Meanwhile, Paragraph 2 states, “In granting and/or annulling rights, as in Paragraph (1), the Minister may delegate authority to Regional Office Heads, Land Office Heads, and/or designated Officials.”

It should be recognized that the resolution of disputes involving land with eigendom rights involves, at the minimum, the two above-mentioned ministries. In the transfer of land rights, authority lies with the Ministry of Agrarian and Spatial Planning/National Land Bureau via the local municipal/regency Land Office. However, in cases where eigendom land is controlled by the state through its HPL rights, the authority for management lies with the Ministry of Domestic Affairs via the local municipal/regency government. In the framework of resolving the current disputes involving land with eigendom rights that is in the process of being released or transferred, both ministries must coordinate.

Based on the bylaw’s contents and lack of favor for the general populace, it is likely that the drafting of the Surabaya Municipal Bylaw No. 16 of 2014 was conducted unilaterally by the Government/Regional Peoples’ Representatives Council of Surabaya, serving as a state institution under the Ministry of Domestic Affairs, without any coordination or consultation with related parties such as the Surabaya Municipal Land Office or the National Land Bureau’s Regional Office for East Java. The latter are institutions under the Ministry of Agrarian and Spatial Planning/National Land Bureau that are competent in land issues. The drafting likewise has not involved social figures in Surabaya competent in the issue of eigendom land, such as former fighters from the National Revolution, veterans, retired soldiers, and retired civil servants. Such a drafting process means that the municipal bylaw cannot be considered to be in accordance with legal requirements, and thus it is nothing but a proposal for land transfer. It is important to remember that legislation can become legislation only if it meets several conditions, including being drafted in the legislature, being able to be implemented, and being able to be supervised by all involved parties. The Surabaya Municipal Bylaw No. 16 of 2014 does not appear to meet these conditions, and it is thus not implementable. As explained above, none of the settlers on eigendom land are willing to implement this bylaw because they are incapable of paying the above-mentioned compensation.

Conclusion

The continued existence of eigendom land in Surabaya has created serious and wide-reaching issues in the form of conflict between settlers and the municipal government of Surabaya. The continued existence of eigendom land stems from the incomplete conversion of land rights, which can be attributed to a lack of consistency in the implementation of the BAL. Behind this inconsistency there is a hidden meaning: The municipal government of Surabaya does not want to lose its eigendom land.

Besides that, this phenomenon, which appears to be a “reemergence” of the domeinverklaring principle (especially when combined with the rental of this land), is an indicator that the unification of land law under the BAL has yet to be fully completed. It also means that delays in agrarian reform have already led to problems in various aspects of social life, including law, economics, politics, and culture.

Though still problematic, the conflict over eigendom land in Surabaya and the commitment to convert such land can be understood as a form of social change and a sign that the agrarian reform process is again being implemented in Indonesia.

The implementation of laws to achieve social justice and welfare, such as in land reform, must be done in accordance with existing legal mechanisms. Furthermore, all parties (especially the municipal government of Surabaya, the Ministry of Domestic Affairs, and the Ministry of Agrarian and Spatial Planning/National Land Bureau) should share a single understanding of the points of the law, allowing them to minimize the emergence of new issues in society.

Accepted: December 20, 2016

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my thanks to two anonymous referees for their comments, suggestions, and criticisms and the meticulous editing by Sunandini Lal who helped make this article fit to publish. I am also grateful to Prof. Dr. Djoko Suryo (promoter) and Nur Aini Setiawati, Ph.D. (co-promoter) at the Postgraduate Program of Humanities Sciences, Faculty of Cultural Sciences, University of Gadjah Mada. Also, thanks to Prof. Dr. Bambang Purwanto, Dr. Agus Suwignyo, and Dr. Farabi Fakih who had been helping to train how to write for an international journal. Also, thanks to all the settlers of the eigendom land, especially Bambang Sudibyo and Supadi H.S. who has provided a detailed description of the data and documents of eigendom land in Surabaya. Lastly, funds from the Ministry of Research and Technology of the Republic of Indonesia through the Doctoral Dissertation Research Program have helped the process of research and the writing of this article.

References

Agus Sekarnaji. 2005. Perlindungan hukum bagi pemegang Surat Hijau di kota Surabaya [Legal protection for holders of Green Certificates in the municipality of Surabaya]. Surabaya: Research report, Institute for Legal Protection, Airlangga University.

Ali Achmad Chomsah. 2004. Hukum agraria (pertanahan) Indonesia [Agrarian (land) law of Indonesia]. Vol. 1. Jakarta: Prestasi Pustaka.

Binsar Simbolon et al. 2008. Surat Hijau di kota Surabaya, provinsi Jawa Timur [Green Certificates in the municipality of Surabaya, province of East Java]. Research report, National Land Bureau of Indonesia and the School of Land Studies, Yogyakarta.

Boedi Harsono. 1982. Hukum agraria Indonesia: Himpunan peraturan-peraturan hukum tanah [Indonesian land laws: A collection of land legislation]. Jakarta: Djambatan.

―. 1968. Undang-undang pokok agraria: Sedjarah penjusunan, isi, dan pelaksanaannja [Basic agrarian law: A history of its drafting and implementation]. Djakarta: Djambatan.

Collins, Randall. 1974. Conflict Sociology. New York: Academic Press.

Colombijn, Freek. 2011. Public Housing in Post-colonial Indonesia: The Revolution of Rising Expectations. Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde [Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia] 167(4): 437–458.

―. 2010. Under Construction: The Politics of Urban Space and Housing during the Decolonization of Indonesia, 1930–1960. Leiden: KITLV Press.

Dick, Howard. 2002. Surabaya, City of Work: A Socioeconomic History 1900–2000. Athens: Ohio University Press.

Diesel, H. van. 1878. Rapport omtrent de particuliere landerijen beoosten de rivier Tjimanuk [Report on the private estates east of the Tjimanuk river]. Tijdschrift voor de Nederlands-Indie Maatschappij van Nijverheid en Landbauw [Magazine of the Dutch East Indies Industry and Agriculture Company] 22: 237–238.

Fuchter, W. A. H. 1941. Verslag van den toestand der stadsgemeente Soerabaja over 1940 Deel 1 [Report on the status of the municipality of Surabaya, 1940, Part 1]. Report issued by the Mayor of Surabaya W. A. H. Fuchter, 1 June.

Gonggrijp, G. 1928. Schets eener economische gescheidenis van Nederlands-India [A sketch of the economic history of the Netherlands-Indies]. Haarleem: De Erven F. Bohn.

Gunawan Wiradi. 2009. Seluk beluk masalah agraria, reforma agraria dan penelitian agraria [The ins and outs of land issues, agrarian reform, and agrarian research]. Yogyakarta: STPN Press.

―. 2000. Reforma agraria: Perjalanan yang belum berakhir [Agrarian reform: A yet-unfinished journey]. Jakarta: INSIST Pres, KPA, and Pustaka Pelajar.

Heemstra, J. 1940. Particuliere landerijen in en om Soerabaja [Particular land in and of Surabaya]. Koloniaal Tijdschrift, 29E Jaargang: 48–62.

Johny A. Khusyairi; and La Ode Rabani, eds. 2011. Kampung perkotaan Indonesia: Kajian historis antropologis atas kesenjangan sosial dan ruang kota [The city villages of Indonesia: Anthropological and historical studies of social disparity and city space]. Yogyakarta: ANRC, Department of History, Airlangga University, and New Elmatera.

Kal, H. Th. 1906. Medeelingen over de hoofdplaats Soerabaja [Communications of the capital Surabaya]. In Tijdschrift voor het Binnenlandsch Bestuur. Batavia: Een-en-dertigste Deel.

Kementerian Agraria dan Tata Ruang [Ministry of Agrarian and Zoning Affairs]. 2014. Sekilas reforma agraria [The glance of agrarian reform]. http://www.bpn.go.id/Program/Reforma-Agraria, accessed November 11, 2014.

Mahkamah Agung Republik Indonesia [Supreme Court of the Republic of Indonesia]. 2011. Putusan kasasi Mahkamah Agung Republik Indonesia No. 471K/Pdt/2011 tanggal 8 September 2011. Dalam perkara antara pemegang Surat Ijo kelurahan Jagir dan Ngagelrejo melawan pemerintah kota/DPRD dan Kantor Pertanahan Kota Surabaya [Decision of the Supreme Court of Indonesia No. 471K/Pdt/2011 dated 8 September 2011, regarding the case of the Green Certificate holders of Jagir dan Ngagelrejo Subdistricts vs. the Municipal Government, Regional Representatives Council, and Land Bureau of the Municipality of Surabaya]. www.mahkamahagung.go.id, accessed May 18, 2015.

Maria S. W. Sumardjono. 2002. Kebijakan pertanahan antara regulasi dan implementasi [Land policy: Between regulation and implementation]. Rev. ed. Jakarta: Kompas.

Mead, George Herbert. 1934. Mind, Self, and Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mochamad Tauchid. 2009. Masalah agraria, sebagai masalah penghidupan dan kemakmuran rakyat Indonesia [Agrarian issues as issues in the life and prosperity of the people of Indonesia]. Yogyakarta: School of Land Studies and Pewarta.

Njo Anastasia. 2006. Penilaian atas agunan kredit berstatus Surat Hijau [Valuing collateral with a Green Certificate status]. Journal of Management and Entrepreneurship 8(2): 116–122. Surabaya: Faculty of Economics Department of Management, Petra Christian University.

Nur Aini Setiawati. 2011. Dari tanah sultan menuju tanah rakyat: Pola pemilikan, penguasaan, dan sengketa tanah di kota Yogyakarta setelah reorganisasi 1917 [From sultan’s land to people’s land: Land ownership, control, and disputes in Yogyakarta after the reorganization of 1917]. Yogyakarta: STPN Press.

Panitya Buku Kenang-kenangan Kota Besar Surabaja [Committee for the Book Commemorating the City of Surabaja]. 1956. Kenang-kenangan 5 Tahun Kota Besar Surabaja 1950–1956 [Memories of five years of the large city of Surabaya]. Surabaya: Committee for the Book Commemorating the City of Surabaya.

Parlindungan, A. P. 1990. Konversi hak-hak atas tanah [Conversion of land rights]. Bandung: Mandar Maju.

Peacock, James L. 1968. Rites of Modernization: Symbolic and Social Aspects of Indonesian Proletarian Drama. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

―. 1967. Comedy and Centralization in Java: The Ludruk Plays. Journal of American Folklore 80(318) (October–December): 345–356.

Pemerintah Kotamadya Surabaya [Municipal Government of Surabaya]. 1968. Gapura, Madjalah Bulanan Gema Kehidupan Kota [Gapura, the monthly magazine of city life]. No. 8 (December).

Pemerintah Kota Surabaya [Municipal Government of Surabaya]. 2013. Transparansi pengelolaan anggaran [Transparency in budget management]. http://www.surabaya.go.id/berita/7963-transparansi-pengelolaan-anggaran, accessed November 30, 2013

―. 2010. Peraturan daerah kota Surabaya No. 13 Tahun 2010 tentang retribusi pemakaian kekayaan daerah [Surabaya Municipal Bylaw No. 13 of 2010 regarding Retribution for the use of regional-owned assets]. Surabaya: Municipality of Surabaya.

―. 2008. Rekapitulasi tanah aset pemerintah kota Surabaya yang dikelola oleh Badan Pengelolaan Tanah dan Bangunan [Recapitulation of Surabaya government’s land assets that managed by the Office for Land and Building Management]. Surabaya: Office for Land and Building Management.

―. 1996. Daftar inventarisasi tanah yang dikelola oleh Dinas Pengelolaan Tanah Daerah Kotamadya Daerah Tingkat II Surabaya [Inventory list of land administered by the Office for Regional Land Management]. Surabaya: Office for Land and Building Management.

―. 1969. Buku himpunan peraturan-peraturan daerah kotamadya Surabaya [Collection of municipal bylaws of the municipality of Surabaya]. Surabaya: Municipal Government of Surabaya.

―. 1960, 1971, 1980, 1990, 2000, 2010, 2012. Surabaya dalam angka [Surabaya in figures]. Surabaya: Surabaya Municipality Statistical Office.

Peters, Robbie. 2013. Surabaya 1945–2010: Neighbourhood State and Economy in Indonesia’s City of Struggle. ASAA Southeast Asia Publication Series. Singapore: NUS Press.

Purnawan Basundoro. 2011. Rakyat miskin dan perebutan ruang kota di Surabaya 1900–1960-an [The poor populace and the struggle for city space in Surabaya 1900–1960s]. Doctoral dissertation, Humanities Program, Faculty of Cultural Sciences, Gadjah Mada University, Yogyakarta.

Ratna Djuita; and Indriayati. 2011. Eksistensi dan konflik penguasaan tanah masyarakat hukum adat [Existence and conflict over land control among adat law communities]. Jurnal Pertanahan, Menggagas RUU Pertanahan [Journal of Land: Discussions of the Planned Land Law] 1 (1 November): 32–68. Center for Research and Development, National Land Bureau of the Republic of Indonesia.

Ricklefs, M. C. 2001. A History of Modern Indonesia since c.1200. 3rd ed. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Sartono Kartodirdjo. 1984. Ratu adil [The just king]. Jakarta: Sinar Harapan.

―. 1973. Protest Movement in Rural Java: A Study of Agrarian Unrest in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries. Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, Jakarta, London, New York, and Melbourne: Oxford University Press/Indira.

Sediono M. P. Tjondronegoro. 1999. Sosiologi agrarian: Kumpulan tulisan terpilih [Sociology of agraria: A collection of selected writings]. Bandung: Laboratory of Sociology, Anthropology, and Population Studies, Faculty of Agriculture, Bogor Agricultural Institute, and Akatiga Foundation.

Soekotjo, R. 1968. Master plan, Suatu kelengkapan jang mutlak bagi tiap-tiap kota [Master plan, a must for every city]. 1968. Gapura, Madjalah Bulanan Gema Kehidupan Kota [Gapura, the Monthly Magazine of City Life] No. 8 (December): 4–5.

Soetojo, M. 1961. Undang-undang pokok agraria dan pelaksanaan landreform [Basic agrarian law and the implementation of land reform]. Jakarta: Staff of the Highest War Commander.

Sudargo Gautama. 1990. Tafsiran undang undang pokok agraria [An interpretation of the basic agrarian law]. Bandung: Citra Aditya Bakti.

Tribun News. 2015. Gubernur setujui perda pelepasan tanah Surat Ijo: Berlakunya tunggu perwali [Governor approves planned law for the release of Green Certificate land: Implementation awaits mayoral decree]. January 6. http://surabaya.tribunnews.com/2015/01/06/gubernur-setujui-perda-pelepasan-tanah-surat-ijo-berlakunya-tunggu-perwali, accessed March 22, 2015.

Urip Santoso. 2012. Hukum agraria, Kajian komprehensif [Agrarian law: A comprehensive study]. Jakarta: Kencana Prenada Media Group.

Winahyu Erwiningsih. 2009. Hak menguasai negara atas tanah [State rights to control over land]. Yogyakarta: Faculty of Law, Islamic University of Indonesia, and Total Media.

Related Registrations

Keputusan DPRD Gotong Royong Kotamadya Surabaya Nomor 03E/DPRD-GR KEP/1971 tertanggal 6 Mei 1971 tentang Sewa Tanah [Decision of the Regional Representatives’ Council for Mutual Assistance of Surabaya No. 03E/DPRD-GR KEP/1971, Dated 6 May 1971, Concerning Land Rental].

Keputusan Presiden No. 34 Tahun 2003 tentang Pelimpahan Kewenangan Pemerintah Pusat ke Pemerintah Daerah (Kabupaten/Kota) tentang Pertanahan [Presidential Decree No. 34 of 2003 Concerning the Delegation of Central Government Authority to Regional (Regency/City) Governments on Land Issues].

Ketetapan Majelis Permusyawaratan Rakyat No. IX/MPR/2001 tentang Pembaharuan Agraria dan Pengelolaan Sumber Daya Alam [Decree of the People’s Consultative Assembly No. IX/MPR/2001 Concerning Agrarian Reform and the Management of Natural Resources].

Keputusan Menteri Agraria No. 12/KaJ1963 tentang Konversi Hak Atas Tanah [Decision of the Minister of Agrarian No. 12/KaJ1963 Concerning the Conversion of Land Rights].

Keputusan Presiden No. 32 Tahun 1979 tentang Pokok-pokok Kebijaksanaan dalam Rangka Pemberian Hak Baru atas Tanah Asal Konversi Hak-hak Barat [Presidential Decree No. 32 of 1979 Concerning Policy Fundamentals in Granting New Land Rights by Converting Western Rights].

Keputusan Walikota Kotamadya Daerah Tingkat II Surabaya No. 1 Tahun 1998 tentang Tatacara Penyelesaian IPT [Decree of the Mayor of the City of Surabaya No. 1 of 1998 Concerning the Procedure for Resolving Permission to Use Land].

Peraturan Daerah Kota Besar Surabaja No. 53 Tahun 1955 tentang Pemberian Hak Erfpacht Kota Besar Surabaya [Surabaya Municipal Bylaw No. 53 of 1955 Concerning the Granting of Erfpacht Rights in the Municipality of Surabaya].

Peraturan Daerah Kotamadya Daerah Tingkat II Surabaya No. 1 Tahun 1997 tentang Ijin Pemakaian Tanah [Surabaya Municipal Bylaw No. 1 of 1997 Concerning Permission to Use Land].

Peraturan Daerah Kotamadya Daerah Tingkat II Surabaya No. 22 Tahun 1977 tentang Pemakaian dan Retribusi Tanah yang Dikelola oleh Pemerintah Kotamadya Daerah Tingkat II Surabaya [Surabaya Municipal Bylaw No. 22 of 1977 Concerning the Use and Retributions for Land Managed by the Municipality of Surabaya].

Peraturan Daerah Kotamadya Daerah Tingkat II Surabaya No. 3 Tahun 1987 tentang Ijin Pemakaian Tanah [Surabaya Municipal Bylaw No. 3 of 1987 Concerning Permission to Use Land].

Peraturan Daerah Kota Surabaya No. 16 Tahun 2014 tentang Pelepasan Tanah Aset Pemerintah Kota Surabaya [Surabaya Municipal Bylaw No. 16 of 2014 Regarding the Release of Land Assets Held by the Municipality of Surabaya].

Peraturan Daerah Kota Surabaya No. 14 Tahun 2012 tentang Pengelolaan Barang Milik Daerah [Surabaya Municipal Bylaw No. 14 of 2012 Regarding the Management of Regional-Owned Assets].

Peraturan Daerah Kota Surabaya No. 2 Tahun 2013 tentang Retribusi Pemakaian Kekayaan Daerah [Surabaya Municipal Bylaw No. 2 of 2013 Regarding Retribution for the Use of Regional Assets].

Peraturan Daerah No. 12 Tahun 1994 tentang Ijin Pemakaian Tanah yang Dikuasai oleh Pemerintah Kotamadya Daerah Tingkat II Surabaya [Surabaya Municipal Bylaw No. 12 of 1994 Concerning Permission to Use Land Controlled by the Municipal Government of Surabaya].

Peraturan Menteri Agraria No. 1 Tahun 1966 tentang Pendaftaran Hak Pakai dan Hak Pengelolaan [Decree of the Minister of Agrarian Affairs No. 1 of 1965 Concerning the Registration of Usage Rights and Management Rights].

Peraturan Menteri Agraria No. 9 Tahun 1965 tentang Konversi Hak Pakai dan Hak Pengelolaan [Decree of the Minister of Agrarian Affairs No. 9 of 1965 Concerning the Conversion of Usage Rights and Management Rights].

Peraturan Menteri Dalam Negeri No. 17 Tahun 2007 tentang Pedoman Teknis Pengelolaan Barang Milik Daerah [Decree of Minister of Domestic Affairs No. 17 of 2007 Regarding the Technical Guidelines for the Management of Regional-Owned Assets].

Peraturan Menteri Dalam Negeri No. 3 Tahun 1979 tentang Ketentuan-Ketentuan Mengenai Permohonan dan Pemberian Hak Atas Tanah Asal Konversi Hak Barat [Decree of Minister of Domestic Affairs No. 3 of 1979 Regarding the Stipulations for the Request for and Granting of Land Rights over Land Formerly under Western Land Rights].

Peraturan Menteri Dalam Negeri No. 2 Tahun 1970 tentang Penyelesaian Konversi Hak-Hak Barat menjadi Hak Guna Bangunan dan Hak Guna Usaha [Decree of Minister of Domestic Affairs No. 2 of 1970 Regarding the Conclusion of Western Land Rights into Building Rights and Cultivation Rights].

Peraturan Menteri Negara Agraria/Kepala BPN No. 9 Tahun 1999 tentang Tatacara Pemberian dan Pembatalan Hak Atas Tanah Negara dan Hak Pengelolaan [Decree of the Minister of Agriculture/Head of the National Land Bureau No. 9 of 1999 Concerning the Procedure for Granting and Annulling Rights over State-Controlled land and Managing Rights].