Contents>> Vol. 6, No. 3

Military, Gender, and Trade: The Story of Auntie Duan of the Northern Thai Borderlands

Wen-Chin Chang*

* 張雯勤, Center for Asia-Pacific Area Studies, RCHSS, Academia Sinica, Nankang, Taipei 115, Taiwan

e-mail: wencc[at]gate.sinica.edu.tw

DOI: 10.20495/seas.6.3_423

Keywords: Yunnanese migrants, economic agency, gender asymmetry, military, narrative approach

Individual-Focused Research

After I buried my second husband, I moved from Chiang Khong [Chiang Khong District, Chiang Rai Province] to Ban1) Sanmakawan [Fang District, Chiang Mai Province, Thailand]. I opened a small grocery store in Ban Sanmakawan. Unfortunately, my house was burgled. . . . I also sold homemade alcohol (kaojiu mai 烤酒賣), but I was caught by the Thai authorities and put in jail. I was freed only after payment of bail. I had four children to bring up. A cousin who was an officer of a [Chinese Nationalist (Kuomintang, KMT)] troop stationed in Ban Mae Aw [Muang District, Mae Hongson Province] took pity on me and asked me to come here to make a living. . . . Ban Mae Aw was a border village frequented by mule-driven caravans and accommodating over a hundred mules daily. The caravans from Burma transported jade stones, and those leaving for Burma mainly carried textiles . . . (Auntie Duan, Nov. 12, 2010)

This paper aims to explore Auntie2) Duan’s life story, a story that mirrors remarkable female Yunnanese Chinese3) migrants’ economic agency in the face of numerous vicissitudes caused by both historical and personal tragedies. Auntie Duan was born into a family of the landlord class in Shuangjiang (雙江) County, Yunnan (雲南) Province, southwestern China, in 1938. She and her family (her parents and other siblings) were compelled to flee to Burma in 1950 due to persecution by Chinese Communists. Three years later, the family had to escape again from the Shan State of Burma to northern Thailand with a group of fellow refugees under the escort of a KMT troop (see later sections for the history of KMT troops in Thailand). The quoted narrative above, given at the very beginning of our meeting, epitomizes Auntie Duan’s migratory experiences, constituted of endless hardships, ongoing moving, a series of economic endeavors, and intriguing interactions with a KMT army entrenched along the border of northern Thailand from the 1960s to the 1980s. While most migration studies (be they in journals or books) are group-oriented, this paper takes an individual-based focus, attempting to address the issues of the military, gendered politics, and livelihoods in northern Thai frontiers where the powers of states (Thailand and Burma) and ethnic armed groups were intersecting.

Auntie Duan married at 19 and again at 24, both times to KMT soldiers. Unfortunately, both husbands died young. Being a woman, a refugee, and a widow moving repeatedly among borderlands, Auntie Duan lived a life characterized by a multiplicity of peripheral positionings. In order to survive and raise her children, she participated in many different economic activities, most saliently as a borderland trader, which required courage and organizational skills to engage in mule transportation under unstable circumstances. Her experiences and economic savvy are outstanding, yet not unique among her fellow Yunnanese women migrants who also encountered similar conditions during a chaotic period when most men were away for military duty or long-distance trade.4) In practice, a great majority of Yunnanese women migrants were the actual managers of their households who contributed to the maintenance of everyday life in resettled villages in northern Thailand (Chang 2005).

Why, then, have I chosen Auntie Duan to be the protagonist (instead of any other Yunnanese woman migrant)? What is the value of individual-focused research? To address these questions, I will begin by briefly describing my meeting with Auntie Duan. It was my first field trip to Ban Mae Aw in November 2010.5) Before that I had conducted long-term fieldwork in one particular Yunnanese village—Ban Mai Nongbourg (Chaiprakan District, Chiang Mai Province)—and had regularly visited other Yunnanese villages in Chiang Mai and Chiang Rai Provinces since 1994.6) Ban Mae Aw started to develop tourism in 2004 on account of its former military history that intertwined with illegal cross-border trade, beautiful scenery, and congenial weather.7) Auntie Duan’s youngest son, who had just passed away due to illness two months prior to my visit, was the former village head. The family owned a grocery store, a restaurant, and a guesthouse where my driver brought me to stay. When I heard that Auntie Duan was one of the first civilian arrivals in the village, I requested that she tell me her story and the history of the village. So what began as a mere coincidence resulted in three days of recording many hours of her narration while we both peeled garlic. (We finished peeling half a sack.) Her narratives disclose not only her lived experiences but also a complex and understudied social history of Yunnanese migrants in northern Thai borderlands.

With the support of a KMT troop and her own entrepreneurial disposition, Auntie Duan pioneered the running of one of the first grocery stores in Ban Mae Aw (since 1975). Her business was diverse and closely connected with the secret cross-border trade between Thailand and Burma by mule caravan. Complementing my former studies on male Yunnanese migrants’ mule caravan trade in the region (Chang 2009; 2014a), Auntie Duan’s narration about her economic participation in Ban Mae Aw provides valuable data about women’s supporting roles in this engagement.

By focusing on her life story based on her oral narratives, I attempt to concretely illustrate her steps of economic initiation as she dealt with a range of adversities, and look into embedded meanings in gendered politics among migrant Yunnanese communities. This methodology is in line with that of several scholars. Lila Abu-Lughod states: “By focusing closely on particular individuals and their changing relationships, one could . . . subvert the most problematic connotations of ‘culture’: homogeneity, coherence, and timelessness” (1993, 14). Anna Tsing advocates: “Individuals’ stories are most exciting in cultural analysis to the extent that they open new conversations about agency and difference” (1993, 231). Alessandro Portelli stresses “to explore [the distance and bond between personal experience and history], to search out the memories in the private, enclosed space of houses and kitchens and . . . to connect them with ‘history’ and in turn force history to listen to them” (1997, viii). Accordingly, delving into individual stories helps one gain insight into social history, as the approach illuminates the power of individual agency in relation to cultural formation, their dialectical impact upon each other, and the respective constraints and resilience.

In short, using a personal narrative approach, this paper addresses issues of gender, military, and borderland livelihoods. Before looking into Auntie Duan’s story I will discuss some fundamental ideas in the development of borderland studies, their contributions and insufficiencies to date, and further explicate my application of a personal narrative approach.

Borderland Studies and the Personal Narrative Approach

Borderland studies is a relatively marginal field in academia, and one that did not gain recognition until the 1980s. This belated engagement is essentially attributed to the domination of the socio-political mainstream of governance based on the institute of the state and the ideology of absolute sovereignty (Grundy-Warr 1993; Donnan and Wilson 1994; 1999; Baud and Van Schendel 1997; Johnson and Michaelsen 1997). Even anthropological theories on culture were predicated on the state. Order, social structure, and shared patterns of beliefs were topics that preoccupied research for many decades (Lugo 1997, 49). However, the emergence of a series of movements since the 1960s, such as the civil rights movement, the New Left, and the feminist movements (see McAdam 1982; Tarrow 1998; Freedman 2003), pushed social scientists to pay more attention to social inequalities on the periphery and among the oppressed. The intensifying illegal flows of people and commodities originating from wars or economic pursuits further stimulated scholars to investigate multiple forms of border crossings and to rethink former political discourses focusing solely on state-centeredness. Consequently, new directions of research started to grow in the 1980s. A burgeoning literature relating to marginal people, culture, migration, environment, and underground trade has especially broadened our understanding of borderland dynamism over the last 20 years (e.g., Walker 1999; Jonsson 2005; Sturgeon 2005; Tagliacozzo 2005; Van Schendel 2005; Giersch 2006; Scott 2009; Chou 2010; Ishikawa 2010; Wellens 2010). While dealing with different issues in diverse border areas using a range of approaches, these works offer alternative lenses to counter the hegemony of national sovereignty that rules out notions of flexible or negotiable boundaries. Scholars of this trend come to see the frontiers not as isolated regions but as “interfaces” replete with transitional forces in an ongoing process that sutures different threads of cultural, economic, political, and historical factors. They stress exploring complex realities linking multi-ethnicities, multi-polities, and the continuous tension and creation of diverse ways of life in borderlands underlying characteristics of continuity, fragmentation, similarity, and inconsistency (e.g., Anzaldúa 1987; Grundy-Warr 1993; Rosaldo 1993; Donnan and Wilson 1994; Lugo 1997; Michaelsen and Johnson 1997; Sturgeon 2005).

Despite this inspiring research, the issues relating to gender relations and women’s lives in borderlands have remained understudied. Even James Scott’s much-celebrated work The Art of Not Being Governed (2009) leaps over these essential matters. Where are the women’s voices? What have they been contributing to borderland livelihoods? How do borderland women perceive themselves in terms of gendered politics? Without probing these questions, borderland studies remain incomplete.

Among the meager number of works that touch upon the gender issue in Southeast Asian borderland studies, Anna Tsing’s In the Realm of the Diamond Queen (1993) is a stimulating piece that integrates detailed ethnography and perceptive theoretical analysis. The book examines the marginality of the Meratus Dayak communities of South Kalimantan (Indonesia), a mountain people who practice shifting cultivation and shamanism and who are perceived by the central state as uncivilized and pagan. The book centers on the power relations between state authorities and the Meratus, the Meratus and the Banjar (a neighboring ethnic group), and Meratus men and Meratus women. Each level of interaction and confrontation highlights the Meratus’ adaptive strategies that are tied to their tradition of traveling politics and reinterpretation of conventions. What I would like to particularly point out is Tsing’s feminist critiques on Meratus gendered politics. While the Meratus are situated in a peripheral position vis-à-vis the state authorities or Islamic Banjar, Meratus women are further peripheral in relation to their male counterparts. Drawing on stories of three ordinary women (ibid., chapter 7) and two female shamans (ibid., chapters 8 and 9), Tsing sheds light on their individual agency that strives for personal autonomy and challenges the male authority. In comparison to Meratus men, who are politically active and spatially mobile, Meratus women are assigned to a relatively static “habitus”8) and excluded from knowledge, authority, and regional travel. In the case of the three ordinary women quoted by Tsing, by traveling to unfamiliar places and seeking foreign lovers, they broke through gendered confinement and managed to gain unusual experiences that “opened up a critical space of commentary and [self-conscious cross-cultural reflections]” (ibid., 220). For the two self-proclaimed female shamans, their professional engagement, which entailed frequent traveling and attracting followers and audiences, created oppositional contestation to male dominance of ritual performance and leadership. Underscoring resistance in gender asymmetry in borderlands, these examples illustrate Meratus women’s constraints as well as creativity deriving from their marginality.

Many societies observe similar gender asymmetry; however, the subject of gender and space has been understudied. Few researchers have been keen to look into how gender relations affect women’s and men’s movement and how movement reinforces or transforms the traveler’s gendered ideology.9) While acknowledging Tsing’s acute analysis of Meratus gender relations, I nevertheless question her use of the three women’s love affairs for interpreting female agency against cultural restrictions on women. Although their journeys and romantic experiences did widen their horizons and grant them a comparative perspective to assess alternative lifestyles, their love affairs still subjected them to male dominance, as these women all had to serve and please their foreign partners. In other words, they only moved from one system of gender asymmetry to another. Therefore, we may question the degree of autonomy these women enjoyed while staying with their alien lovers.

In contrast to these Meratus women, Auntie Duan has been a widow since she was 30. At that time her youngest child was only one year old. Looking back on her life experiences, she explicitly commented that women could not count on men. How did she strive against repeated adversities? What was the role of the KMT army in the course of her migration and resettlement? How do we evaluate her economic engagement in relation to migrant Yunnanese borderland livelihoods? And how does Auntie Duan review her own life, especially in terms of gender relations? To address these questions, I see a personal narrative approach as most forceful.

According to Elinor Ochs and Lisa Capps (1996), narrating life experiences relates one’s interaction with the outside world in a sequence that is meaningful, connecting past, present, and imagined worlds. Likewise, Nigel Rapport and Andrew Dawson observe: “Narrative mediates one’s sense of movement through time,” and “through narrative, human beings, individual men and women with agency, tell the world, and tell it anew, continuously reorganizing their ‘habitation in reality’” (1998, 28, 29). Resonating with their statements, Roxana Waterson stresses how “history intersects with personal experience” (2007, 7) and points to the emergence of historical consciousness through storytelling (ibid., 12). Through the narrative genre, a speaker’s temporal consciousness is expressed through a subjective truthfulness in the process of recollection. Factual data about specific events is therein enriched by personal memory nuanced by cultural meaning (Marcus and Fischer 1986, 54, 58; Thompson 1988; Riessman 1993, 1; Waterson 2007, 10–12). In short, narrative is a powerful medium that gives a voice to the marginalized and powerless. The following sections based on Auntie Duan’s narratives elucidate her rich life experiences characterized by persistent travel and commercial shrewdness.

Life before Coming to Ban Mae Aw

Traditionally restricted from the public sphere (buke paotouloumian 不可拋頭露面), Yunnanese women were for the most part relegated to domestic life. While men dominated the economic world of business, some women—especially those of the lower class—supplemented the family income by weaving and making clothes or working on the farm and raising animals (Fei and Chang 1948; Hsu 1967; Johnson 1975; Topley 1975). However, a series of historical contingences beginning in 1949 have largely upset this gendered confinement. The Chinese Communists took over China in 1949 and subsequently initiated a range of political movements from the 1950s through the 1970s. These political events caused massive numbers of Yunnanese to flee their homeland, and an essential portion of them arrived in Burma, a young independent nation that was troubled by continuous conflicts between the central state controlled by the Burman (the ethnic majority) and many ethnic armed groups. Due to their illegal status and geographical proximity, most of the Yunnanese refugees stayed in rural Shan and Kachin States of Burma. The political instability inside the country, however, compelled them to move from place to place. Auntie Duan related that she had been to Tangyan, Mt. Loijei, Pangyan, and several other places in the borderlands of Shan State.

Among these Yunnanese refugees, there were remnants of the KMT armies who managed to establish guerrilla forces in Shan State in 1950 and received support from the KMT government that had retreated to Taiwan as well as the US government, the leader of the anti-Communist bloc during the Cold War (Chang 2001; 2002). Many male refugees joined the KMT forces as a means to survive and in the hope of fighting their way back to Yunnan. Nevertheless, under pressure from the United Nations, these foreign troops were disbanded first in 1953–54 and then in 1961. Two armies, the Third and Fifth Armies, totaling about 4,700 troops (Union of Burma, Ministry of Information 1953; Zeng 1964; Young 1970; Qin 2009, 276), survived the disbandment; and a large portion of them entered northern Thailand with the tacit permission of the Thai government, which perceived these anti-Communist forces as useful for the prevention of Communist infiltration from Burma. While these forces were entrenched along the northern Thai border, a small portion of their fellow troops stayed on in Shan State to facilitate the underground trafficking between Thailand and Burma. From the mid-1960s through the 1980s, destitute Burma was suffering from a socialist economy and was in need of consumer goods smuggled from its neighboring countries, especially Thailand (Lintner 1988, 23; Mya Than 1996, 3; Chang 2009). The KMT armies and a range of ethnic armed groups in the Thai-Burmese borderlands offered military escorts to businessmen’s caravans and lived on taxes collected from them.10) Some of these armed groups also engaged in trade. While consumer goods were taken into Burma, opium, jade stones, and natural resources were smuggled out of the country. The KMT armies were the most powerful groups involved in this trade from the 1960s to the 1970s, and they were not disbanded until the late 1980s.

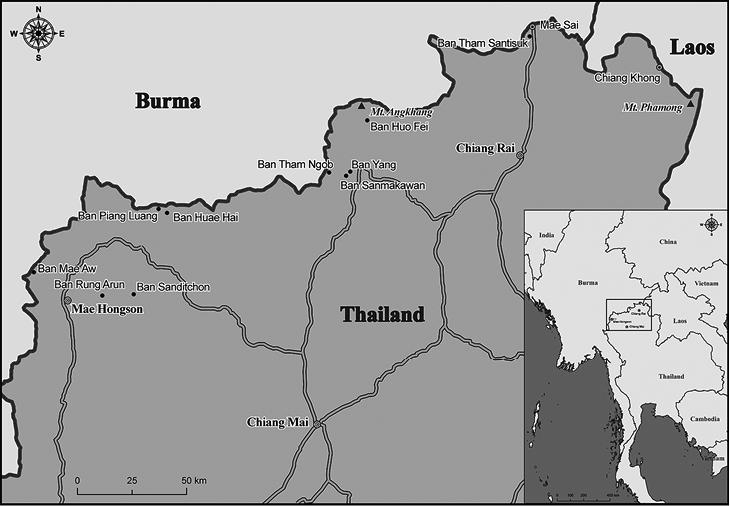

Fig. 1 Map of Thailand

Apart from military and economic undertakings, the KMT armies led a large number of Yunnanese refugees from Burma to Thailand and helped establish many villages for their resettlement in the border areas of Chiang Rai, Chiang Mai, and Mae Hongson Provinces.11) Auntie Duan and her family joined a group of around 1,500 Yunnanese refugees, primarily dependents of KMT guerrillas and traders, to escape to Thailand under the escort of a KMT troop prior to the first evacuation act in 1953. These refugees were among the earliest arrivals in Thailand.12) They first settled in Mt. Angkhang in Chiang Mai Province, and a year later (1954) they were relocated to Ban Yang and Ban Huo Fei (both in Fang District, Chiang Mai Province). Auntie Duan and her family went to Ban Yang. She stayed in the village until she married a KMT soldier through her parents’ arrangement three years later (1957) and moved to Ban Huae Hai (Wiang Haen District, Chiang Province), where she gave birth to her first child, a girl (1958). When the child was younger than two, Auntie Duan’s husband was killed in an accident (1959). Three years later (1962) she married another KMT soldier, again through her parents’ arrangement, and gave birth to three boys, also in Ban Huae Hai. After the last child was born, her husband’s unit was transferred to a post in Mt. Phamong (Chiang Khong District, Chiang Rai Province), bordering Laos, to fight against the Miao Communists at the Thai government’s request. Auntie Duan then moved to Chiang Khong (1973). Unfortunately, her second husband died in battle a year later. The leader of the Third KMT Army, to which her late husband had belonged, helped her relocate to Ban Sanmakawan, a village next to her parents’. She stayed there for one and a half years before making another move to Ban Mae Aw (1975) at her cousin’s invitation.

Like other dependents of the KMT armies whose husbands were away for military duties—escorting caravans to Burma, recruiting soldiers, or engaging in fighting—Auntie Duan was separated from her two successive husbands most of the time. The armies gave only rationed rice to dependents who had to make their own living. Most Yunnanese female refugees conducted petty trade in the marketplace and farmed the land (Chang 2005). Auntie Duan talked about her life during this period:

I have done all kinds of work to make a living except for being a thief (wo sheme duozuo zhiyou zei meizuoguo 我什麼都做只有賊沒做過). . . . After moving to Ban Huae Hai I sold homemade alcohol, rice noodles, and some miscellaneous goods. I also raised pigs, cattle, and chickens. Huae Hai was a small, poor village (hen guabo 很寡薄), so it was difficult to make a good business. I therefore went to Ban Piang Luang [a neighboring village also in Wiang Haeng District] to open a shop . . .

[For two winters] I traded to the minorities, a few Lisu and Lahu villages. They grew poppies along the border. After the poppies were sowed [in the ninth month of the lunar calendar], traders gathered in hill-tribe villages to do business, selling rice, food, and other daily necessities to them on credit. The hill people were busy farming and had no time to cook. . . . One baht of goods was sold for two to three baht. After the opium harvest, the minorities paid back the traders with opium. . . . When it was time to harvest the opium, more traders came to the minority villages and held opium fairs (gan yanhui 趕煙會). Most sellers carried goods on their shoulders for sale. A neighbor and I transported our goods on mules. I led two workers and set off from Ban Huae Hai to Chiang Dao to buy commodities first and then transported them to the opium fairs for sale. My children were with me. I carried one up front and the other on the back. After selling opium, the minorities would buy clothes, rice, and other types of goods for use the whole year. . . . Both growing and trading opium is detrimental to society, but there were no job opportunities. If you didn’t do it, you would starve . . .

After moving to Chiang Khong, I entered Laos every day to purchase cheroots and sweaters made from rabbit hair. I sold the cheroots at home and transported the sweaters to Mae Sai for sale. I also sold fried noodles. I got up very early every morning and led two workers to fry two big pots of rice noodles. I sold the noodles wholesale to a few shops nearby. . . . I also raised ducks, four hundred to five hundred Japanese ducks. This kind of duck had to be stockaded on land and could not touch water. I had two other workers to look after them. However, I didn’t make a profit from raising the ducks because many of them died of disease . . .

After my [second] husband died, the leader of the [KMT] Third Army assigned me a piece of land in Ban Sanmakawan. I built a house there [in 1974] and started a grocery business again. I also sold homemade alcohol, but I was caught by the police and jailed for one night. I had to bail myself out with 1,500 baht. The salary for a worker was only six to seven baht a day at that time. . . . With profits from trade I purchased gold; part of it I hid at home, and the rest I lent to businessmen.13) One morning when I went to the stream to wash clothes, a thief broke into my house. He broke the front door lock and overturned my bed and every chest. I lost more than 30,000 baht in cash and 24 ma (碼) of gold. . . . Four qian (錢) make up one ma, and one qian of gold was worth 600 baht then . . .14)

Auntie Duan’s narratives disclose her unusual resilience in the face of numerous predicaments deriving from both historical events and personal tragedies. These vicissitudes pushed her to travel wide stretches of land and brought her in contact with different people and lifestyles. Consequently, they also exempted her from the conventional restrictions placed on Yunnanese women’s movements. We may thus assert that migration to a certain degree reconfigured the gendered geographies among Yunnanese migrants and resulted in granting women more spatial flexibility for economic participation, although this did not alter the existing gendered structure grounded in the principles of patrilineality and patriarchy (see further discussion later).

In a conversation, Auntie Duan acknowledged her parents’ influence on her: “I had learned how to make alcohol from my mother and how to trade from my father. After coming to Thailand, my father carried soft drinks and other stuff to a few KMT posts for sale. He also helped transport goods with his mules.” Acquiring skill and knowledge from her parents’ experiences, Auntie Duan further expanded her opportunities by investing in other types of business while living in various locations. She was not afraid of exploring new possibilities, even though they might entail suffering a financial loss. Raising the Japanese ducks was one example. Her experiences demonstrate her extraordinary entrepreneurial spirit in risk-taking. Moreover, her capacity to hire workers and teach them different tasks distinguished her from most Yunnanese women migrants without employees who only participated in petty trade, farm work, sewing clothes, and raising pigs and chickens. The amount of money she lost in the theft attests to her wealth.

Reviewing her life experiences, Auntie Duan was conscious of her strenuous efforts in fighting hardships. In practice, making a living for herself and her children was her fundamental concern. Discussing gendered geographies of power in another paper (Chang 2005), I have pointed out that Yunnanese women migrants in northern Thailand anchored their life experiences at different stages on the organization of jia (家 family): the jia before they got married, the jia after their marriage, the jia during their flights and in resettlement, and the (future) jia for their grown-up children. Being mothers, facing their husbands’ frequent absences, the women became the real pillar of their families, and it was for the children that the pillar stood. Simply put, children were their hope, whose needs impelled them to cope with numerous challenges. The theme of suffering for the family recurred in their narrations, underlining the cultural value of “sacrificial motherhood” that we find also in many other parts of the world (e.g., Keyes 1984; Lessinger 2001; Tam 2006). Accordingly, it is not surprising that Auntie Duan defended her engagement in trading opium for a brief period while joking about not being a thief.15)

Although Auntie Duan’s economic condition was unusual within her group, her case illustrates the extent to which migrant Yunnanese society was flexible in allowing women to engage in economic pursuits during their husbands’ absence. More specifically, apart from small trade, it was possible for women to conduct big business. In terms of methodology, the focus of Auntie Duan’s story is in accord with Tsing’s stance:

The excitement of an individual’s story lies in the story’s ability to expand and unbalance dominant ideas of the contours in which familiar subjects are made . . . Subjects understood as “eccentric” in this sense are those whose agency demonstrates the limits of dominant categories, both challenging and reaffirming their power. This is a useful way to think about subject positions within the zone of exclusion and creativity that I have been calling “marginality.” (1993, 232)

Therefore, the primary value of individual stories lies not in delineating a representational picture of a community (although it may have such a function) but in exploring the limits of a community’s tolerance and its flexibility for change, and also analyzing the frictions arising between the individual and his/her community. While we may assert that the Yunnanese women migrants were able to enjoy a greater degree of freedom in spatial movement than their female predecessors back in Yunnan, they were not given complete autonomy. This is revealed in Auntie’s Duan’s two marriages, which were arranged by her parents. Moreover, the KMT forces played a critical role in determining the migrants’ lives. The latter were dependent upon the armies’ institutional power that assisted in their migration and resettlement. While men were enlisted or taxed by the armies, their dependents in the villages were supervised by self-governing committees that were organized by the armies (Chang 2002).16) In practice, the two KMT armies functioned as two patriarchal entities to the Yunnanese migrant communities in northern Thailand, especially those living in the KMT villages. On the one hand they were protective of their fellow refugees, but on the other hand they also exploited the latter’s labor force as well as their wealth. Auntie Duan’s life experiences after she moved to Ban Mae Aw further reveal this intriguing interrelationship.

Life after Moving to Ban Mae Aw

After the losses from the burglary, Auntie Duan received an invitation from a cousin in Ban Mae Aw to set up a grocery shop there. While in Ban Mae Aw, I also interviewed a former KMT officer, Commander Yang. He told me that Ban Mae Aw was established by the KMT Third Army in April 1975 to facilitate the growing cross-border trade via the area. He himself led 380 soldiers from the headquarters of the KMT Third Army in Ban Tham Ngob (Chaiprakan District, Chiang Mai Province) to Ban Mae Aw via Ban Piang Luang. The troop opened up the frontier, which was mostly covered by forests, and founded the village.17) The number of soldiers increased when the situation demanded, such as when fighting occurred. The highest number of soldiers was around 600. The KMT troop started to cultivate land and grew rice the second year. The army gave each soldier 30 baht for non-staple food and another 30 baht for pocket money. Each soldier only received the pocket money. The money for non-staple food was given to the troop’s leader for the management of his soldiers’ meals. The amount of money was small, and most troop leaders had to participate in cross-border trade to make extra money for their units when conditions allowed.

Initially no dependents came with the troop. Auntie Duan arrived in late 1975, and she said there were only two or three households of dependents the first few years.18) They all had connections with the army’s officers and were invited to run grocery shops in the village, which also served as inns for humans and/or animals, supplying the needs of mule caravans. Auntie Duan discussed her life in Ban Mae Aw:

[After deciding to move to Ban Mae Aw,] I collected the two gold bars that I had lent to businessmen. One gold bar was equivalent to 24 ma. I sold the gold and used the money to open a grocery store in Ban Mae Aw. The shop was built with bamboo and grass. . . . My workers brought three mules from Ban Sanmakawan to Ban Mae Aw via Ban Tham Ngob. I took an airplane from Chiang Mai to Mae Hongson, and then took a pickup truck from Mae Hongson to Ban Mok Champae. Ban Mok Champae was a Shan village, and it was where the road for cars ended. I rested there for a night and rode on horseback for five or six hours the next day before arriving at Ban Mae Aw. I took only my youngest child with me; I left the others with my parents for schooling in Ban Yang.

I’m a woman and had several workers working for me, five or six. A couple of them were muleteers, and the rest helped with cooking, cleaning, and selling things at the shop. I worked with them. You couldn’t be idle and let them work alone. . . . I didn’t need to lock the doors at night. Soldiers were stationed along the border; security was good. My former [second] husband had been an officer in the army. The present officers were his friends. The troop respected us and dared not misbehave . . .

After making some profit, I purchased a herd of cattle and some pigs, which I kept in the backyard. Some time later, I purchased four more mules for transportation. I needed to replenish the commodities in Mae Hongson every 10 days or half a month. I left very early in the morning, around five o’clock. I took two muleteers with me. After arriving in Ban Mok Champae around 11 o’clock, I left the mules and muleteers and took a pickup truck to Mae Hongson, about half an hour. The muleteers fed the mules feed and grass and cooked their own lunch. In Mae Hongson I purchased goods from a few shops. These goods required two or three pickup trucks to get them back to Ban Mok Champae. After finishing buying, I had a late lunch, often just a bowl of rice noodles, and then returned to Ban Mok Champae with the purchased goods. The muleteers and I then loaded part of the goods onto the mules for transport back to Ban Mae Aw. The rest were stored at a villager’s house. When my shop was running out of goods, I would send muleteers to ship them back. . . . From Ban Mok Champae, the muleteers and I would set off by 10 or 11 o’clock at night and arrive in Ban Mae Aw around 4 or 5 o’clock the next morning. The mules could see at night and recognized the route . . .

I had two or three muleteers working for me. Sometimes I let out my mules to caravan traders engaged in long-distance trade back and forth between Thailand and Burma. It took about five to seven days from Ban Mae Aw to Taunggyi (in Burma). The rent for one mule on a trip to Burma was 2,500 kyat. At that time, Burmese kyat had good value: one kyat could be exchanged for two Thai baht. But I had to provide food for my muleteers who took care of the mules on the journey, and of course also feed for the mules. On the way back, the muleteers looked for other traders who needed mules to go to Thailand . . .

The village was animated with mule caravans coming and going every day. Most of the time there were over a hundred mules; at the very least there were 70 to 80. . . . When the caravans arrived in the village, they needed accommodation. I built a long house next to my shop that could accommodate 20 people.19) Accommodation was free; I earned money from the feed sold for the animals. A barrel of feed for which I paid 50 baht was sold for 100 baht. I also sold vegetables, meat, pickles, tofu, and so on to the muleteers. They cooked for themselves. . . . Every muleteer had a piece of tarpaulin and two woolen blankets with him. He put a piece of tarpaulin on the floor and a blanket upon the tarpaulin to make a bed and covered himself with the other blanket. I also provided extra blankets. Muleteers traveled from place to place and were used to a simple lifestyle. As for the mules, they were kept outside the long house . . .

Gradually, more dependents moved to the village. But fighting among the KMT troop, the other ethnic rebels, and the Burmese army erupted from time to time. . . . A year after I had moved to Ban Mae Aw, the year of the dragon [in 1976], our troop fought the Burmese army along the border. The battle flared up suddenly. I was alone with a few female workers at home. I had just replenished my shop and had had my muleteers transport goods by mule to Burma. I had to run immediately and had no time to take anything from the shop or even lock the doors. It was raining; I didn’t even have a piece of tarpaulin with me. My workers ran toward a nearby Miao village. A neighbor and I ran in another direction. She had a carbine with her. Burmese airplanes were flying above us. The noise of shooting and bombing was terrifying—pin-bong-pin-bong. We ran in the rain until we reached Ban Mok Champae. About 20 days later, when the situation had calmed down, I returned to Ban Mae Aw, but alas, my shop had been ransacked. Nothing was left. Who had robbed my shop? It was our own soldiers. They had to eat and took everything. I couldn’t ask for a penny back. After this event, I had to start my business all over again. I sold homemade tofu, pickled vegetables, meat, and rice noodles. I replenished my shop on credit, and returned the debt bit by bit. . . . I’ve tried all kinds of work in my life.

Auntie Duan’s narratives vividly delineate the texture and nuance of borderland lives, especially how people moved around and made a living tied to the intriguing geopolitics of the past. Specifically, her narratives provide significant data about the inn business in connection with the long-distance mule caravan trade between the northern Thai border and Shan State of Burma from the 1960s to the 1980s. The latter was an exclusively male undertaking dominated by Yunnanese migrants. Its organization was characterized by leadership and hierarchy and required strict observance of discipline, division of labor, and compliance with taboos (Chang 2009; 2013; 2014a). Complementing this masculine, peripatetic activity, Auntie Duan’s story reveals a relevant engagement, foregrounding women’s participation in the inn business that catered to mule convoys, both humans and animals. Although the business was not run solely by women, women played a leading role as most men were away. Auntie Duan’s economic skills include her efficiency in shop management, organizational skill in replenishing stocks, and knowledge of trading routes. Considering the low visibility of women’s lives in this frontier area, the concrete details of the narratives make up an important part of social history, enhancing our understanding of a particular livelihood. In effect, we may say, Auntie Duan’s narrative composes an alternative history featuring women’s everyday practices that interplayed with Yunnanese cultural norms as well as complex geopolitics. It is in contrast to a state-centered historiography that underlines states’ policies, political achievements, foreign relations, and warfare.

With regard to the intriguing political contexts, Commander Yang confirmed to me that apart from the KMT unit, there were several other ethnic armed groups that were encamped around the area, including Pa-Os (Taungthu), Shans, and Karens. The KMT Third Army collaborated with the Pa-O and Shan groups but sometimes fought against them to protect its trading routes. Traders passing through territory controlled by the armed groups had to pay taxes to them. Every entity thus tried to defend and even expand its sphere of power. In addition to these ethnic forces, the Burmese army patrolled the frontiers and attacked the ethnic rebels from time to time. The warring situation did not stabilize until the late 1980s (Lintner 1994).

While the KMT armies were protective of their fellow refugees, they were also exploitative. Within the two remnant armies, the power hierarchy was grounded on patriarchal ethics and the symbiosis of a patron-client relationship. The two army leaders were the supreme patriarchs who enjoyed the strongest power, but they also bore the highest responsibility to oversee the well-being of their communities (Chang 2002). The rest of their cadres possessed power and obligations relative to their ranks. The request for any special rights was predicated on one’s affiliation with the armies. Auntie Duan’s arrival in Ban Mae Aw and the opening of her shop were due to her connections with the KMT. Her late second husband had been a staff officer (canmou 參謀) and had sacrificed his life during the war. Moreover, her father had established trading connections with KMT troops in several posts, and one of her cousins was a chief of the unit stationed in Ban Mae Aw.

Centered on patriarchal relations, Auntie Duan’s social networks evolved through her father, husbands, and male kith and kin rather than her own initiative. She had inherited the social capital from these male family members and relatives for migration, resettlement, and economic endeavors. Despite her entrepreneurship and risk-taking nature, her social capital was limited to her connections with the KMT. In contrast, the social world of Yunnanese male traders was constituted of multiple sources ranging from different ethnic armed groups to Burmese and Thai local authorities and high-ranking officers of both nations (Chang 2004; 2009; 2014a). This diverse association was a sine qua non that facilitated their peripatetic engagements in a conflictual region. In comparison, there was a sharp difference between Yunnanese men’s and women’s social capital rooted in an asymmetric gendered structure. This phenomenon reminds us to reflect on the Meratus women’s love affairs referenced in Tsing’s ethnography. The pursuit of an alternative lifestyle through love affairs with foreign men still subjects these women to male dominance and does not alter the existing gendered structure.

The grocery business in the villages in which mule caravans congregated was a kind of monopoly.20) It earned good profits. Informants in other KMT villages also reported that in the past, without support from the armies, it was difficult for ordinary civilians to run a business. The owners were either KMT troop leaders or civilian traders connected to important KMT officers. The actual operators of the shops were those officers’ or traders’ wives, as the men were mostly away for military duty or long-distance trade. In effect, these women’s economic undertaking was complementary to the men’s. Auntie Duan’s narrative concretely describes the services her shop provided to the mule convoys. Though her economic engagement did not require as much long-distance travel as that of the men’s cross-border trade between Thailand and Burma, it demanded organizational skills and courage in risk-taking, as her story illustrates. Moreover, her previous migration experiences inside Burma and from Burma to Thailand enhanced her geographical knowledge, benefiting her business of leasing mules to caravan traders.

With large numbers of caravans moving through the village, Auntie Duan should have been able to make a lot of money. However, fighting interrupted village life from time to time. Under special circumstances, the stationed KMT troop could even become the predator, as Auntie Duan’s story shows. In other KMT villages, I also heard informants complaining that the armies often demanded that traders who owned mules and cars help with transportation and contribute money or food, especially rice. Although Auntie Duan did not refer to this in her story, it is quite possible that she also had to pay such “obligations.”

Conclusion: Gendered Politics and Borderland History

Auntie Duan was aware of the toils she had gone through, which she viewed as originating from both her sex and her fate. Although her condition was seemingly beyond her control, it did not entail mere passivity. In contrast, Auntie Duan’s capacity to act in spite of persistent vicissitudes demonstrates her unrelenting efforts to make life better for herself and her children. The following narrative reflects her thoughts in this regard:

In all those places I have stayed, not one of them was stable. Life has never been stable for me. I’ve stayed for a few years in each place and have become aged with continuous moving. . . . Being a woman you have to get married and have children in order to run your own life. If you don’t get married and stay with your brothers and in-laws, you may find yourself trapped in a quarrelsome life, as everyone has his or her temperament. . . . In my generation, parents arranged daughters’ marriages. We were young and didn’t know anything. . . . After my first husband passed away, my parents urged me to marry again. They said that a young widow could easily attract jealousy and rumors from other people and that I needed a man to take care of me, a man to be my foundation (genji 根基). Moreover, the child with my first husband is a girl. They worried that I would be alone when I became old. . . . Being a soldier’s wife, you were alone most of the time. This happened to other [Yunnanese] women, not just me. Soldiers had their duties. A trip to Burma lasted at least a few months, sometimes over a year. I was used to my [two successive] husbands’ absence. . . . A man didn’t have to shoulder family responsibilities; he was in the army or away for trade. But being a woman and a mother, you had to bring up your children. I have been a widow since I was 30. Women cannot really count on men. This is my fate. I wish not to be a woman or a mother in my next life.

Auntie Duan’s narration illustrates her consciousness of gender asymmetry among Yunnanese migrants in Thailand. While the women were able to conduct trade and travel, these changes did not really challenge men’s authority. Women were still perceived as subordinate to men, who were the center of social life. According to Yunnanese social conventions, women needed men to be their foundation, although this was nominal as the men were away most of the time. Auntie Duan was aware that while marriage gave a woman her social status and living space at home, it also came with heavy responsibilities, especially those of motherhood. She had to run the household and support her children, regardless of whether her husband brought enough money home. During that uncertain period, while men were expected to venture far away, they were in fact spared from a household’s daily responsibilities. For Yunnanese women migrants, economic engagement was not for the pursuit of individual autonomy per se (although it may have entailed such a result) but to fulfill the responsibilities of motherhood, as analyzed earlier. In her narration, Auntie Duan forcefully said her primary consideration was to avoid starvation. Intriguingly, this asymmetric gender relation constrained women’s lives on the one hand, but urged them to be creative on the other. This paradoxical condition conforms to Tsing’s statement “marginality is a source of both constraint and creativity” (1993, 18).

Auntie Duan’s bravery and devotion to her family illustrate her dynamism as well as frustration and pain in the ongoing process of shaping and reshaping gendered roles. Not being able to change what cannot be changed, she attributed her hard life to another factor—fate, a life attitude that commonly exists among first-generation Yunnanese refugees. Although Auntie Duan gave birth to three sons, two of them have migrated to Taiwan and the other one just passed away. Auntie Duan went to Taiwan and lived with her second son from 1992 to 2006. While there, she took care of her two grandchildren and also helped her son to open a Yunnanese restaurant. But in the end, she decided to return to northern Thailand to grow old. She said the winter in Taiwan was too cold for her and she wanted to be buried with her second husband someday. I am not sure whether she considered a dead wife still needing the company of her dead husband to be her foundation. But her wish to not be born as a woman in her next life mirrors her strong will to be lifted from the restraint of gender asymmetry. This projection with reference to her former and current lived experiences affirms Ochs and Capps’ argument (1996) mentioned at the beginning of the paper that a narrative approach helps draw out insights into a narrator’s interaction with the outside world in a meaningful sequence that connects the past, present, and imagined worlds. However fanciful, Auntie Duan’s craving for an imagined existence underscores her poignant awareness and dissatisfaction with her reality as it links to cultural frictions and socio-political injustice.

Located in Thai borderlands and confronting repeated military actions, Yunnanese migrants were primarily dependent on the KMT armies for their security and well-being. These migrants and the KMT troops were placed in an ambivalent position, lacking legal status and public recognition. Notwithstanding this, their resettlement configured a significant role in the borderland history during the Cold War—forming a buffer zone stemming Communist advancement from Burma and Laos, and enabling a wide range of underground circulations between Thailand and Burma (including people, goods, capital, and intelligence) (Lintner 1994; Chang 2014b). In contrast to the dominance of a Thai historiography centering on the nation’s sovereign power, self-claimed territorial integrity, and imagined cultural coherence, concern for the heterogeneous lives of borderland dwellers, their fluidity, and shifting political allegiances and boundaries have often been suppressed or distorted. Women’s existence has been further marginalized. Prior to 1990, only sporadic media and academic attention touched on the KMT, other ethnic armed groups, and drug trafficking, and the lives of Yunnanese women migrants were completely overlooked. Their contribution to the sustenance of everyday life in border villages and support of the illicit flows was obliterated.

Using Auntie Duan’s life story, I have attempted to shed light on a formerly invisible world dialectically shaped by individual agency and external sociocultural and political forces. Because of a series of historical contingencies, between the 1950s and 1980s most Yunnanese male migrants either participated in the underground trade back and forth between Thailand and Burma or joined the KMT forces. Their absence from home contributed to Yunnanese women migrants’ economic engagements in the frontiers of Thailand and Burma. In comparison, Yunnanese women migrants in Burma enjoyed a greater degree of spatial mobility than did their fellow Yunnanese migrant women in Thailand. As explored elsewhere (Chang 2013; 2014b), many of the former group engaged in long-distance smuggling by car and going to jade or ruby mines for a range of economic possibilities, such as buying gemstones, selling goods, and lending money. However, these women’s travels were motivated not by encouragement from the Yunnanese community but rather by a dire politico-economy in Burma during the socialist regime. The nation was relying on the black market economy, driving its people to risk their lives for any means of survival. In practice, Yunnanese women migrants in Burma were allocated to a similar asymmetric gendered structure as that of Yunnanese women migrants in Thailand. In other words, spatial mobility and economic opportunities do not necessarily guarantee women an equal position to men. Nevertheless, the efforts of first-generation women migrants have to a certain degree relaxed the formerly strict divide between the public and domestic spheres.

Many Yunnanese migrants in northern Thailand obtained legal status after the 1980s, which ensured their freedom of movement. Consequently, many of the younger generation, both men and women, have left their villages for Thai cities, especially Bangkok, Chiang Mai, and Phuket, for work. Since Yunnanese women migrants fled Yunnan, their lives have evolved through time and place. The changes they have made might not have been envisioned by their predecessors. This paper, by drawing on the case study of Auntie Duan, has focused only on the time period prior to 1990. Further discussion on the issue of gender relations among the younger generation and women’s economic roles would be beneficial and should be considered.

Accepted: May 30, 2017

Acknowledgment

I would like to thank Noboru Ishikawa for organizing the workshop “Radically Envisioning a Different Southeast Asia: From a Non-State Perspective” in Kyoto, January 18–19, 2011, where I presented an earlier version of this paper. The workshop is part of the JSPS Asian Core Program from April 2009 to March 2014. I am also indebted to Caroline Hau, Masao Imamura and the two anonymous reviewers for their careful reading of different versions of this paper and providing valuable comments. The Center for Geographic Information Science, RCHSS, Academia Sinica, helped produce the map.

References

Abu-Lughod, Lila. 1993. Writing Women’s Worlds: Bedouin Stories. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Anzaldúa, Gloria. 1987. Borderlands La Frontera: The New Mestiza. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books.

Baud, Michiel; and Van Schendel, William. 1997. Toward a Comparative History of Borderlands. Journal of World History 8(2): 211–242.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1977. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Translated by Richard Nice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chang, Wen-Chin. 2014a. By Sea and by Land: Stories of Two Chinese Traders. In Burmese Lives: Ordinary Life Stories under the Burmese Regime, edited by Wen-Chin Chang and Eric Tagliacozzo, pp. 174–199. New York: Oxford University Press.

―. 2014b. Beyond Borders: Stories of Yunnanese Migrants of Burma. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

―. 2013. The Everyday Politics of the Underground Trade by the Migrant Yunnanese Chinese in Burma since the Socialist Era. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 44(2): 292–314.

―. 2009. Venturing into ‘Barbarous’ Regions: Trans-border Trade among Migrant Yunnanese between Thailand and Burma, 1960–1980s. Journal of Asian Studies 68(2): 543–572.

―. 2005. Invisible Warriors: The Migrant Yunnanese Women in Northern Thailand. Kolor: Journal on Moving Communities 5(2): 49–70.

―. 2004. Guanxi and Regulation in Network: The Yunnanese Jade Trade between Burma and Thailand, 1962–88. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 35(3): 479–501.

―. 2002. Identification of Leadership among the KMT Yunnanese Chinese in Northern Thailand. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 33(1): 123–146.

―. 2001. From War Refugees to Immigrants: The Case of the KMT Yunnanese Chinese in Northern Thailand. International Migration Review 35(4): 1086–1105.

Chou, Cynthia. 2010. The Orang Suku Laut of Riau, Indonesia: The Inalienable Gift of Territory. London: Routledge.

Donnan, Hastings; and Wilson, Thomas M. 1999. Borders: Frontiers of Identity, Nation and State. Oxford: Berg.

―. 1994. An Anthropology of Frontiers. In Border Approaches: Anthropological Perspectives on Frontiers, edited by Hastings Donnan and Thomas M. Wilson, pp. 1–14. Lanham: University Press of America.

Fei Hsiao-Tung (Fei Xiaotong); and Chang Chih-I. 1948. Earthbound China: A Study of Rural Economy in Yunnan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Freedman, Estelle B. 2003. The History of Feminism and the Future of Women. London: Ballantine Books.

Giersch, C. Patterson. 2006. Asian Borderlands: The Transformation of Qing China’s Yunnan Frontier. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Grundy-Warr, Carl. 1993. Coexistent Borderlands and Intra-state Conflicts in Mainland Southeast Asia. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 14(1): 42–57.

Hayami, Yoko. 2007. Traversing Invisible Borders: Narratives of Women between Hills and the City. In Southeast Asian Lives: Personal Narratives and Historical Experience, edited by Roxana Waterson, pp. 253–277. Singapore: NUS Press.

Hill, Ann Maxwell. 1998. Merchants and Migrants: Ethnicity and Trade among Yunnanese Chinese in Southeast Asia. New Haven: Yale Southeast Asia Studies.

Hondagneu-Sotelo, Pierrette. 1994. Gendered Transitions: Mexican Experiences of Immigration. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hsu, Francis L. K. 1967 [1948]. Under the Ancestors’ Shadow. Garden City: Anchor Books.

Ishikawa, Noboru. 2010. Between Frontiers: Nation and Identity in a Southeast Asian Borderland. Singapore: NUS Press.

Johnson, David E.; and Michaelsen, Scott. 1997. Border Secrets: An Introduction. In Border Theory: The Limits of Cultural Politics, edited by Scott Michaelsen and David E. Johnson, pp. 1–39. London and Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Johnson, Elizabeth. 1975. Women and Childbearing in Kwan Mun Hau Village: A Study of Social Change. In Women in Chinese Society, edited by Margery Wolf and Roxane Witke, pp. 215–241. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Jonsson, Hjorleidur. 2005. Mien Relations: Mountain People and State Control in Thailand. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Kaplan, Caren. 1996. Questions of Travel: Postmodern Discourses of Displacement. Durham: Duke University Press.

Keyes, Charles F. 1984. Mother or Mistress but Never a Monk: Buddhist Notions of Female Gender in Rural Thailand. American Ethnologist 11(2): 223–241.

Kron, Stefanie. 2011. The Border as Method: Towards an Analysis of Political Subjectivities in Transmigrant Spaces. In The Ashgate Research Companion to Border Studies, edited by Doris Wastl-Walter, pp. 103–120. Farnham and Burlington: Ashgate.

Lessinger, Johanna. 2001. Inside, Outside, and Selling on the Road: Women’s Market Trading in South India. In Women Traders in Cross-Cultural Perspective: Mediating Identities, Marketing Wares, edited by Linda J. Seligmann, pp. 73–100. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Lintner, Bertil. 1994. Burma in Revolt: Opium and Insurgency since 1948. Bangkok: White Lotus.

―. 1988. All the Wrong Moves: Only the Black Economy Is Keeping Burma Afloat. Far Eastern Economic Review, October 27.

Lugo, Alejandro. 1997. Reflections on Border Theory, Culture and the Nation. In Border Theory: The Limits of Cultural Politics, edited by Scott Michaelsen and David E. Johnson, pp. 43–67. London and Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Mahler, Sarah J.; and Pessar, Patricia R. 2001. Gendered Geographies of Power: Analyzing Gender across Transnational Spaces. Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power 7(4): 441–459.

Marcus, George E.; and Fischer, Michael M. J. 1986. Anthropology as Cultural Critique: An Experimental Moment in the Human Sciences. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Massey, Doreen. 1994. Space, Place, and Gender. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

McAdam, Doug. 1982. Political Process and the Development of Black Insurgency 1930–1970. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Michaelsen, Scott; and Johnson, David E., eds. 1997. Border Theory: The Limits of Cultural Politics. London and Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Mya Than. 1996 [1992]. Myanmar’s External Trade: An Overview in the Southeast Asian Context. Singapore: ASEAN Economic Research Unit, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Ochs, Elinor; and Capps, Lisa. 1996. Narrating the Self. Annual Review of Anthropology 25: 19–43.

Portelli, Alessandro. 1997. The Battle of Valle Giulia: Oral History and the Art of Dialogue. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Qin Yihui 覃怡輝. 2009. Jinsanjiao guojun xieleishi 金三角國軍血淚史 [The tragic history of the KMT troops in the Golden Triangle, 1950–1981]. Taipei: Zhongyang Yanjiuyuan and Lianjing Chubanshe.

Rapport, Nigel; and Dawson, Andrew. 1998. Opening a Debate. In Migrants of Identity: Perceptions of Home in a World of Movement, edited by Nigel Rapport and Andrew Dawson, pp. 3–38. Oxford: Berg.

Riessman, Catherine Kohler. 1993. Narrative Analysis. Newbury Park: Sage.

Rosaldo, Renato. 1993 [1989]. Culture & Truth: The Remaking of Social Analysis. Boston: Beacon Press.

Scott, James C. 2009. The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Sturgeon, Janet C. 2005. Border Landscapes: The Politics of Akha Land Use in China and Thailand. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Tagliacozzo, Eric. 2005. Secret Trades, Porous Borders: Smuggling and States along a Southeast Asian Frontier, 1865–1915. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Tam, Siumi Maria. 2006. Engendering Minnan Mobility: Women Sojourners in a Patriarchal World. In Southern Fujian: Reproduction of Traditions in Post-Mao China, edited by Tan Chee-Beng, pp. 145–162. Hong Kong: Chinese University Press.

Tarrow, Sidney G. 1998. Power in Movement: Social Movements and Contentious Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Thompson, Paul. 1988. The Voice of the Past: Oral History. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Topley, Marjorie. 1975. Marriage Resistance in Rural Kwangtung. In Women in Chinese Society, edited by Margery Wolf and Roxane Witke, pp. 67–88. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. 1993. In the Realm of the Diamond Queen: Marginality in an Out-of-the-Way Place. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Union of Burma, Ministry of Information. 1953. The Kuomintang Aggression against Burma. Rangoon: Ministry of Information.

Van Schendel, Willem. 2005. The Bengal Borderland: Beyond State and Nation in South Asia. London: Anthem Press.

Walker, Andrew. 1999. The Legend of the Golden Boat: Regulation, Trade and Traders in the Borderlands of Laos, Thailand, China and Burma. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Waterson, Roxana. 2007. Introduction: Analyzing Personal Narratives. In Southeast Asian Lives: Personal Narratives and Historical Experience, edited by Roxana Waterson, pp. 1–37. Singapore: NUS Press.

Wellens, Koen. 2010. Religious Revival in the Tibetan Borderlands: The Premi of Southwest China. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Young, Kenneth Ray. 1970. Nationalist Chinese Troops in Burma: Obstacle in Burma’s Foreign Relations, 1949–1961. PhD dissertation, New York University.

Zeng Yi 曾藝 (Republic of China, Ministry of Defense 國防部史正編譯局). 1964. Dianmian bianqu youji zhanshi 滇緬邊區游擊戰史 [History of guerrilla wars in the Sino-Burmese border areas]. 2 vols. Taipei: Guofangbu Shizheng Bianyinju.

1) Ban means “village” in Thai.

2) Yunnanese Chinese in Burma and Thailand address each other with affiliated terms based on the kinship principle. Auntie Duan (duan dama 段大媽) was how I addressed her. I am greatly indebted to her for sharing her life story with me during my stay.

3) Yunnanese Chinese are composed of Yunnanese Han and Yunnanese Muslims (Hill 1998). Auntie Duan belongs to the Han group. To avoid repetition, I use “Yunnanese” instead of “Yunnanese Chinese” hereafter.

4) The income from long-distance trade was very uncertain due to the risks involved during the journey. A round trip often required half a year. Traders could be robbed or deterred from returning home because of regional conflicts (see Chang 2009).

5) I also went to two other Yunnanese villages in Mae Hongson Province during that trip—Ban Sanditchon (Pai District) and Ban Rung Arun (formerly known as Ban Mae Soya, Muang District).

6) In total, I have been to 28 Yunnanese villages in northern Thailand. In addition, I have conducted research on Yunnanese migrants in Burma since 2000.

7) Ban Mae Aw, 45 kilometers from Mae Hongson, was considered by the Thai authorities to be a village dependent on the drug trade. Some villagers had been involved in smuggling amphetamines from Burma since the 1990s. In February 2003 Thai Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra announced an anti-drug campaign. For about a year, Ban Mae Aw was frequently checked and searched by the Thai army. After that, the local authorities encouraged development of ethnic tourism.

8) I am using Pierre Bourdieu’s word here. “Habitus” may refer to a system of dispositions in relation to one’s perception and practice; see Bourdieu (1977).

9) Apart from Tsing, other authors who have elaborated on this subject include Doreen Massey (1994), Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo (1994), Caren Kaplan (1996), Sarah Mahler and Patricia Pessar (2001), Yoko Hayami (2007), and Stefanie Kron (2011).

10) Yunnanese male migrants’ engagement in the underground transborder trade between Thailand and Burma was also partly attributed to their lack of legal status in Thailand, which constrained their free movement inside Thailand.

11) According to ex-officers of the KMT armies, during the 1960s and 1970s the troops escorted an estimated 10,000 refugees from Burma to northern Thailand. In the early 1970s there were more than 40 Yunnanese refugee villages in the border areas. Among them, 29 could be classified as KMT villages, which were founded and supervised by the KMT armies. The number of villages continued to increase following repeated inflows of Yunnanese refugees from Burma. According to the Free China Relief Association (FCRA), a semi-official organization in Taiwan that provided aid programs for Yunnanese refugee villages in northern Thailand from 1982 to 2004, there were 77 Yunnanese villages in 1994. According to local estimates, the population of Yunnanese migrants in Thailand today ranges between 100,000 and 150,000, and that of Yunnanese migrants in Burma between half a million and one million.

12) Another group, consisting of 580 people, arrived in Thailand via Mae Sai (a border town in Chiang Rai Province) and was resettled in Ban Tham Santisuk (or Ban Tham, Mae Sai District, 12 kilometers from Mae Sai).

13) Merchants used gold bars to purchase opium in Burma at that time.

14) In the narration that I quoted at the beginning of the paper, Auntie Duan said that a thief burgled her house before she was arrested by the police for selling homemade alcohol.

15) Although both practices may be considered immoral acts, the former engagement was generally accepted among fellow refugees in the face of difficult living conditions, while the latter was condemned.

16) Generally speaking, the KMT Third Army supervised villages in Chiang Mai and Mae Hongson Provinces, and the Fifth Army supervised those in Chiang Rai Province.

17) According to a village report written in 1994, Ban Mae Aw occupied an area of 3,100 rai, consisting of 2,100 rai of the plain and 1,000 rai of hill land. One rai is equivalent to about 0.4 acres or 1,600 square meters.

18) According to FCRA data, Ban Mae Aw had 95 civilian households prior to the Third Army’s disbandment in 1989. After the disbandment, only 108 soldiers stayed; many of them married local Shan or hill-tribe women. In 1994 there were 110 households, consisting of 71 households of Yunnanese Chinese and 39 of hill tribes. There were 172 households when I visited the village in 2010.

19) A muleteer usually drove two or three mules on a long-distance trip.

20) Apart from Ban Mae Aw, other KMT villages at which long-distance mule caravans stopped included Ban Tham Santisuk (Mae Sai District, Chiang Rai Province), Ban Mae Salong (Mae Fa Luang District, Chiang Rai Province), Ban Mai Nongbour (Chaiprakan District, Chiang Mai Province), Ban Arunotai (Chiang Dao District, Chiang Mai Province), and Ban Piang Luang. The operation of mule caravans persisted into the 1980s and was gradually replaced by car transportation in the mid-1980s.