Contents>> Vol. 7, No. 1

Jit Phumisak and His Images in Thai Political Contexts

Piyada Chonlaworn*

*ปิยดา ชลวร, Faculty of International Studies, Tenri University, 1050 Somanouchi, Tenri, Nara 632-8510, Japan

e-mail: 2515226[at]gmail.com

DOI: 10.20495/seas.7.1_103

Jit Phumisak (1930–66) is one of the most well-known figures among Thai leftist scholars and activists in the 1950s. He was born slightly before monarchical absolutism was abolished, and he grew up in an anti-American atmosphere when socialism was booming. Apart from his numerous writings, what makes Jit different from other socialists and Marxists of his time is his legendary life and untimely death. He became a cultural hero and a legendary figure among young activists in the mid-1970s democracy movement. His image, however, was constructed and modified by different actors under different agendas. This paper reviews Jit’s life and work by focusing on the construction of his image by the military regime, Communist organization, scholars, political activists, and local authorities from the 1970s to the present, taking into account the different political situations in Thailand throughout these periods.

Keywords: Jit, Marxism, radical intellectuals, Cold War era, political polarization

Introduction

After Thailand changed from an absolute monarchy to a constitutional monarchy in 1932, the country fell into a vicious cycle of elected civilian governments and coup d’état-led military regimes. The authoritarian military regime after the end of World War II can be divided into three periods: the Phibunsongkram era, 1948–57; the despotic Sarit-Thanom era headed by Sarit and his clique between 1958 and 1973; and the recent royalist military regime that overthrew Thaksin and his sister Yingluck’s governments in 2006 and 2014 respectively.

Each despotic era saw attempts to resist the authoritarian government and calls for social revolution. As Craig Reynolds and Lysa Hong point out, in each period—notably the first two—“the climate for political, economic, social and historical analyses as well as for imaginative literature was shaped by the nature of the regimes in power” (Reynolds and Hong 1983, 78). Roughly three generations of radical movement can be identified. The first generation was mainly Sino-Thai Communists—lookjin according to Kasian Tejapira—who had close ties with Communist Parties in China and Vietnam before and during World War II. Together with participants in the Boworadet rebellion, they were taken in as political prisoners (Kasian 2001, 26–27). Some were journalists and writers who co-founded the Siamese Communist Party in 1930, which was renamed the Communist Party of Thailand (CPT) in 1952. The second generation was Thai and Sino-Thai urban intellectuals who introduced and spread Marxism and socialism throughout Thailand through print media during the Phubun and Sarit eras from the late 1940s to the 1960s. The third generation consisted of university student activists who opposed the military regime of Thanom in 1973 and 1976 and were crushed by police and paramilitary forces in the October 1976 riot; they went into the jungles and carried out an underground movement. It was in the postwar era, during a short civilian government, that Marxism entered the Thai cultural market in the form of considerable numbers of printed commodities (ibid., 59). Apart from numerous books, radical newspapers such as Mahachon and magazines such as Aksornsarn were produced by socialists and Marxists such as Supha Sirimanond, Asanee Pholachan, Thaweep Woradilok, and Seni Saowaphong.

Among leftist intellectuals of the 1950s, one cannot overlook the poet, musician, and intellectual named Jit Phumisak (1930–66). Jit was born slightly before monarchical absolutism was abolished and grew up in an anti-American atmosphere when socialism was booming. He was among many socialist writers of his time who were influenced by socialist predecessors, but what makes him different from other socialists and Marxists is that after his untimely death his works that had been banned were secretly reproduced by young activists (Reynolds 1987). The year 2016 marks 50 years after his death, and it is interesting to see how his image has changed through the times: from a Communist to a revolutionary figure, a scholar, and recently an adviser on lucky numbers. This paper reviews Jit’s life and work by focusing on the construction of his image by different actors—the military regime, the Communist Party of Thailand, scholars, political activists, and local authorities—from the 1970s to the present, taking into account different political situations in Thailand throughout these periods.

Life and Work

Those who have studied Thai political history would know Jit as a Marxist intellectual, while linguistic and literature students would know him as a talented poet representing peasants and the working class. But most of all, he is probably known and remembered by socialists and political activists as a rebellious and progressive thinker who dared to criticize the Thai monarchy and Buddhism.

Jit was born on September 25, 1930 in a typical Thai middle-class family. His father was a civil servant working in a tax office, and his mother was a housewife. He was born in Prachinburi Province, in the east of Thailand. Because of his father’s job he moved from place to place in his childhood, and he moved to Bangkok when he was 16.

Jit showed an interest in writing from the time he was in high school. He wrote many poems, most of which were about love, flirting, and travel. In his childhood he lived in Battambang, which used to be part of Thailand during World War II but is now in the northwestern part of Cambodia. There he gained knowledge about the Khmer language, history, and archeology and was able to read stone scripts, which led to an interest in Thai classical literature. When he was young he wrote, “I have a dream of becoming one of the literature intellectuals, but in the real life I was so poor. . . . I wanted to buy books but had no money” (Wichai 2003, 167). Even though the poems he wrote in this period were about love and flirting, there is one he wrote in 1946 that showed his patriotic feelings when Thailand lost Battambang to the French. In the poem he said that if Thailand became strong and powerful again, all the lost territories would be returned to it (Wichai 2007, 5–6).

Being talented in linguistics and a voracious reader, he enrolled in the Faculty of Arts at Chulalongkorn University in 1950. During his college years he adopted Marxist ideology and wrote a number of articles that were published within and outside the university. Two articles that he wrote for Chulalongkorn’s prestigious yearbook, of which he was an editor in 1953, provoked a controversy in the university, resulting in his being thrown from the stage by conservative students. This became known as the yonbok incident. In the yearbook he wrote an article criticizing Buddhist monks for their greedy and materialistic behavior and a poem condemning fun-loving women who got pregnant, saying that they did not deserve to be called mothers.1) These articles did not only cost him a suspension from the university for one and a half years, but raised suspicions among the police that he was a Communist. This was because criticizing Buddhism and women, two core values in Thai society, was regarded as a Communist act at the time (Prachak 2015, 150). However, during and after his suspension Jit continued producing a large number of works criticizing Thai feudalism, imperialism, and monarchy-centered historiography in the form of poems, articles, literature reviews, and translations of socialist novels.

One of his most well-known works, The Real Face of Thai Feudalism Today, made known to non-Thai scholars by the English translation and analysis by Craig Reynolds (1987), explicitly criticizes Thailand’s social structure based on sakdina—or feudal values—that has long persisted in the monarchy and the ruling class and points to the feudal remnants in Thailand in the late 1950s. It was first published in a journal in 1957 and was banned not long after. Amid the anti-Communism policy of pro-American oligarchy, Jit was arrested and imprisoned in 1958, the year Marshall Sarit Thanarat imposed a coup d’état. He was in jail with other political prisoners for six years without trial and was released in 1964 with a verdict of “not guilty.” Then he went into the jungles to join the CPT in the northeast, only to be shot to death by a village headman and paramilitary force in 1966 at the age of 36. Since he was labeled by the authorities as a Communist, his murder was justified—the village headman who shot him was said to have been rewarded by the American authorities with a rifle and a round-trip ticket to Hawaii. After Jit’s death, his body was not properly cremated, and the details about his death are a mystery until today (Reynolds 1987, chapter 1).

As stated above, Jit was not the only leftist writer at the time. From the 1932 revolution until the post-World War II period, there were Sino-Thai Communists and left-wing intellectuals who introduced Marxism to Thai intellectual society through print media such as books, newspapers, and journals. But what made Jit distinct from previous and later generations was probably that, apart from his academic writings being debated among academics, because of his controversial biography he became a cultural hero and a model revolutionary among young generations in the mid-1970s democracy movement (ibid., 14).

During his lifetime Jit produced many genres of work: essays, poems, academic monographs, and songs. His works can be divided into different themes: academic work on Thai and Khmer history, etymology, ethnography, reviews of Thai classical literature and art, translations of Marxist novels, and others such as critiques on women, Buddhism, and his memoir about life in prison. Being influenced by Marxist ideology, almost all of his works had a clear purpose: to criticize the Thai ruling class, call for social change, and serve as a voice for peasants and the working class. Among the 16 songs he composed, “Saengdao haeng sattha” (Starlight of faith) is probably the most well known. He composed this song while in prison to encourage himself and others to overcome trouble and injustice (Wichai 2009, 153–154), and it became a symbolic song among social resistance protesters from the mid-1970s democratic movement to recent years, as will be discussed below.

Socialism and Marxism in Thailand

Even though Phibunsongkram imposed a coup d’état in 1947, ousting the civilian regime led by Pridi Phanomyong, the period between 1945 and 1958 is seen as a golden age of Thai social literature and an important formative period for the postwar Thai left-wing and national liberation movement (Flood 1975, 62). The Thai left-wing movement had started a bit earlier with the founding of the Thai Communist Party during World War II by those who got inspiration from the Chinese Revolution, gaining support from left-wing members in the Free Thai (or Seri Thai) group.2) At least 23 Thai radical publications in the form of newspapers, weeklies, and biweekly and monthly magazines were released during 1946 and 1967, though most of them were short-lived due to Sarit’s suppression after the 1958 coup d’état (Kasian 2001, 150).

Among the radical publications of that time, a monthly journal called Aksornsan was one of the most well known. Founded by the pro-Pridi veteran journalist Supha Sirimanond in 1949, it became a platform for Thai socialist intellectuals to spread their ideas and studies on Marxism through the translation of foreign works. Even though the journal was not all left wing, as half the writers were right-wing intellectuals, the articles written by socialists such as Kulap Saipradit, Asanee Pholchan, and Samak Burawat were influential in spreading Marxist ideas.3) Asanee, using the pen name Intrawuth, wrote a number of articles criticizing the ruling class for legitimizing their power through Buddhism and literature. For example, he criticized a famous classical work written during the Ayutthaya period called Lilit Phra Lor (The narrative poem of Prince Lor), a tragic love story of a handsome prince and two princesses from another country. Intrawuth argued that the novel was nothing more than a shallow and erotic story widely read among the ruling class and that it led people to be submissive to the royalty.4) Other articles by him include an introductory study of Marxism and translated works by the Chinese socialist Lu Xun and Joseph Stalin’s work on historical materialism (Suthachai 2006, 148). It is said that through Aksornsan avant-garde writers such as Asanee played an important role in introducing a new concept of art—art and literature for life. They believed that art and literature should be created to represent peasants and the working class, leading to a revolutionary society (ibid., 164).

Aksornsan was closed down in 1952 by Sarit’s order due to its Communist character. Despite its short life, the journal inspired many young readers who later became serious socialists, including Jit. He got both the methodology of analysis and the content of his works from earlier writers who contributed to Aksornsan.5)

When and how did Jit embrace socialism and Marxism? It can be said that Chulalongkorn University, ironically a right-wing and conservative institution, was the place where he learned about Marxism and embraced its ideas. It was not a coincidence considering the socialism and Marxist study that was getting more attention in the early 1950s by leftist intellectuals of that time. Jit was probably inspired by many articles in Aksornsan and came to know about and admire the Chinese revolutionary Lu Xun through the journal.6)

Jit’s Critique of Sakdina Literature

Even though Jit was well known for his seminal work The Real Face of Thai Feudalism Today, there are other writings that deserve attention. This section will focus on one of his reviews of Thai classical literature.

As a keen reader of Thai and Khmer classical literature, Jit reviewed a number of Thai classical literary works written from the Sukhothai to the mid-Bangkok period (thirteenth century to the 1860s). Parallel with The Real Face, his purpose was to criticize a traditional way of poem writing that focused on the monarchy or courtiers rather than the lives of ordinary people, and to call upon readers to pay more attention to the social aspect of these works.

He first reviewed Nirat Nongkhai (Travelogue to Nongkhai), a long travelogue written in 1869 by a low-ranking court official named Tim Sukhayang (official name Luang Phatthanapongphakdi). It was about a military expedition from Bangkok to Nongkhai in the Northeast to suppress rebels in Laos, then Thailand’s vassal state. Tim was in that expedition, too, and he described in his work how hard the journey was and pointed to the wrong decision and lack of strategy of the supreme commander who ordered the expedition, Phraya Borommahasrisuriyawong (Chuang Bunnak), an influential high-ranking courtier in King Chulalongkorn’s reign. Upon finding out that he had been criticized, the commander was very angry and used his influence to pressure King Chulalongkorn to punish Tim. Not long after the travelogue was published, it was banned and burned by a court order and Tim was physically punished and imprisoned. Jit pointed out that Tim had been punished because of his courage in criticizing his commander, if not disobeying him, which was considered unacceptable in Thai society. The uniqueness of this work is that while most nirat or travelogues written in those days are descriptive narrations of the scenery of each place the poet visited and about his subjective feeling of missing home and his loved ones—by and large using erotic expressions—Nirat Nongkhai goes beyond the traditional style by touching upon the political factions in the palace at that time. The author also describes the social and economic lives of the people and places he encountered, which, from Jit’s viewpoint, serves well as a historical source. On the one hand, Jit urged his readers not to read travelogues just for pleasure but to look deeper at their social implications (Jit [Sithi] 1975, 4–13). On the other hand, he used this work to demonstrate a hierarchy and patron-client system in Thai society from the old times to the present (ibid., 89).

Jit also reviewed a classical work titled Lilit Ongkan Chaengnam (Oath of allegiance), one of the oldest works of literature in Thai history, written anonymously in the early Ayutthaya period (mid-fourteenth century). The poem is mainly about the scary curse and calamity if one betrays or becomes disloyal to the King. It was written in parallel with the oath of allegiance ceremony held twice a year by Brahmin monks, when court officials were required to drink “sacred” water as a symbol of allegiance to the King. The ceremony, being influenced by the Angkor kingdom, has a long history dating back to the Sukhothai period and lasted until the 1932 coup d’état (which Jit viewed as a commoners’ revolution) (Jit 1994, 111–112, 116). The literature is considered by Thai conservative scholars as a piece of great writing that helped to unify civil servants from different parts of the kingdom, and the ceremony itself was viewed as protection from all calamities. However, in Jit’s view, it was written with the purpose of elevating the status of Thai Kings as God-Kings, or Devaraja in Hindu ideology, and legitimizing the King’s power by making an oath of allegiance look sacred and thus making people submissive. He argued that this ceremony actually took place in order to threaten the King’s subjects, as those who failed to make their oath to the King would be regarded as rebels and face the death penalty, which in his opinion was irrational and a form of exploitation (ibid., 102–113). In the context of anti-Communism at that time, he compared the act of insurrection in ancient times to his times, when the government viewed Communism as an insurgency (ibid., 103).

In contrast to the court-centered literature discussed above, Jit reviewed a popular novel titled Raden-Landai (The story of Raden and Landai). Written in the early nineteenth century by Phra Mahamontri, a police department commander in the King Rama III reign, whom Jit regard as a sakdina civil servant, Raden-Landai is the story of a beggar of Indian origin named Landai and two women—Kra-ae and Pradae. Kra-ae is Landai’s girlfriend, who sells sweets in a market. Pradae is a beautiful Malay woman from Patani who is taken to Bangkok as a slave and later is sold into marriage to a man named Pradua, a cow breeder who is probably of Indian origin as well. Landai meets Pradae and falls in love with her, leading to their adulterous affair and awkward confrontation with Pradae’s husband. Things get complicated when Kra-ae becomes jealous and involved in the love affair (ibid., 36–73).

Written in a funny and satiric style with some erotic scenes, Raden-Landai seems to have been enjoyed by both courtiers and commoners of the time, as it was later adapted as a play. According to Jit, the distinctive feature of this novel is that it is a story of poor and marginalized people, in contrast to the conventional and narrow-minded mainstream theme of the time, which was usually a love story involving a King or prince. Little is known about the author, but Jit praised him greatly for his “courage to break the conventional style of sakdina literature and his progressiveness a state civil-servant of that time could have” (ibid., 28–29).

Except for Raden-Landai, Jit labeled this literature “sakdina literature” as it was written to serve Thailand’s monarchy. He pointed out how influential and proactive the monarchy was in boosting its legitimacy through literature. His purpose was thus to make readers aware of the influence of the monarchy, not by excluding these literary works but by critically reading them from a new perspective, that is, a socialist viewpoint (ibid., 116).

Jit in Thai Politics

Jit was born shortly before Thailand changed from an absolute monarchy to a constitutional monarchy. During his lifetime Thailand was under Marshall Phibunsongkram and Sarit’s dictatorship. Within the context of the Cold War, Phibun, who initially lacked a firm grip on his government, strengthened his position by allying with the United States. One of their common agendas was anti-Communism. Sarit, who overthrew Phibun’s regime in 1958, adopted an anti-Communist policy that he used also to crack down on his political rivals. Under the government’s agenda, Communism was regarded as a foreign threat that was anti-Buddhism and anti-monarchy. This discourse easily gave authorities the power to detain suspects without trial. The CPT became an underground organization after briefly enjoying its freedom of expression during the civilian government of Pridi Phanomyong after World War II.

Prior to Sarit’s coup, Jit had written a number of poems and articles criticizing the materialism and imperialism that was sweeping Thai social and political life. Unsurprisingly, this led to the arrest and imprisonment of Jit and other leftist journalists and anti-royalists between 1958 and the 1970s on the charge of being Communists and Communist sympathizers. As Reynolds points out, the Sarit government’s attempt to attribute the ideas and activities of Jit and other leftists to a Communist foreign power was a way of reducing the danger of those ideas and activities and of diverting attention away from any substantial problems at home (Reynolds 1987, 28–29). While in Lard Yao prison, Jit called himself a “political poet” and continued to write over 60 poems and monographs to raise political awareness against dictatorship and the pro-capitalist regime. In prison he got to know many members of the CPT, which was probably the reason he joined the Party in late 1965. His relationship with the CPT was, however, somewhat ambiguous. Reynolds points out that his relations with the Party were not smooth, and that Jit was not a Party member in his lifetime as the CPT conferred membership on him only after his death (ibid., 38). Somsak contradicts these statements arguing that Jit was closely involved with the Party in many ways, such as composing songs for it, and that many Party leaders recognized him (Somsak 1993, 22–36). Some CPT members were close friends of Jit’s family, and that was the reason they obtained Jit’s manuscripts and printed them after his death. Whatever the argument might be, it can be asserted that Jit was labeled a Communist even before he joined the Party and it was actually the anti-Communist regime that pushed him and many others to join the Communist Party.

The Image of Jit in the Mid-1970s

Almost 10 years after Jit’s death, Thailand experienced a popular uprising in October 1973 that overthrew the authoritarian regime of Thanom and Praphat and called for a constitution. This was, for the first time in Thai political history, a victory of the democratic movement led by university students and the royalist masses. After that the country enjoyed a couple of euphoric years of democracy, while the Communist movement was revitalized by the CPT. In the 1970s, leftist publications that had been banned during the oligarchic years were reprinted and republished. Jit’s provocative works such as The Real Face, Collected Poems and Literary Reviews by “Political-Poet,” and Thiphakorn: Artist, Warrior of the People (Collection of Jit’s Essays on Literature) were reprinted, and his hidden monographs were discovered and made public (Somsak 1993, 29; Kengkit 2014, 128).7) The works of Jit and other Marxists became widely read and reinterpreted by young students who found inspiration from them and were ready to take part in politics and demand for democracy.

The attempts by the CPT and new leftists to radicalize young people did not involve only publishing socialist and thought-provoking books, but also the myth-making of revolutionary heroes. Che Guevara is the most explicit example: he was popularized by the Party as an intellectual who joined an armed struggle. But later, the focus seemed to shift from foreign figures to domestic ones, and Jit came to be regarded as the “people’s warrior” and a patriotic figure: a Thai version of Guevara.8) Apart from his biographies, songs and poetry about him were composed by famous artists of the time.

While the CPT was at its peak in spreading propaganda in October 1973 and October 1976, there was at the same time resentment among the urban middle class toward the increasing radicalism of students. This middle class later became a social platform for newly emerged rightists with support from conservative elites, which led to the tragic massacre of university students at Thammasat University on October 6, 1976 (Prachak 2015, 136).

The demonstration originally took place to oppose the return of ex-Prime Minister Thanom to Thailand after his exile, but it ended in the mass killing of over 100 university students by right-wing government and paramilitary forces. More than 3,000 were arrested and 19 were charged and put on trial for “rioting” and threatening the nation, religion, and monarchy (Thongchai 2002, 253–254). As a result, many thousands of students who fled the arrest had no choice but to join the CPT in the jungles.

What is the connection between the CPT and the student movement in the October incident? There was an allegation that the CPT might have manipulated the demonstration in order to end radicalism among urban students and force them to join the armed struggle in the jungles, even though the claim was viewed as lacking substantial basis (ibid., 251–252). The direct result of the massacre was that the CPT was able to recruit many young students and continued publishing underground books about Jit, making him a “revolutionary hero” along with other socialists such as Asanee Pholchan (Thikan 2014, 157). His poems about revolution in the jungle and the marching songs that he composed while in prison were later sung by young people. His most well-known song, “Saengdao haeng sattha” (Starlight of faith), inspired young people who joined the underground movement to fight against the authoritarian regime and boost their sense of socialist patriotism. Students who joined the CPT in the jungles after the October incident already knew about the legendary Jit, so they were eager to learn more about him and his works (Reynolds 1987, 39).

Jit might be regarded as a Communist and revolutionary-cultural hero. But at the same time we should bear in mind, as some studies point out, that his image was heavily created, modified, and reproduced by CPT members and leftist activists in the mid-1970s, largely with the aim of inspiring young people to join the armed struggle under the Party’s leadership, and that the construction of Jit’s image 10 years after his death was focused more on his life and mysterious death than trying to understand or materialize his political ideas. In other words, the CPT seemed to put more effort into creating a hero than into spreading Marxist ideology among young people (Chusak 2014, 46–47; Kengkit 2014, 117–120).

Jit in the Post-Communism Era

After the student uprising/massacre incident in 1976, Thailand’s political ideology was split into the urban-based right wing and the jungle-based left wing led by the CPT. But due to several factors, such as the alliance between the Thai and Chinese governments in the 1980s and the divisions between students and key members in the Party, the CPT began to lose popularity among leftist elites (Thongchai 2002, 259–261). At the same time, there was a decline in Marxist studies and the rise of trends such as nationalism and community studies in Thai academic circles. This change paved the way for another group of intellectuals who never joined the Party and resented Communism. They attempted to replace Jit’s image as a revolutionary with that of a scholar whose academic works shed light on Thai literature, etymology, and history. As a result, there was a changing trend in the publication of his works during this period by some publishers and scholars—from a socialist theme to various other themes under linguistics and history.9) In other words, with the decline of the CPT Jit’s image was “de-radicalized” and de-politicized (Kengkit 2014, 118–126).

Jit’s works have also been analyzed from the approach of gender studies by recent academics. His viewpoint about women can be seen in many of his poems, articles, and translations of foreign novels. In his article “Adit pachuban lae anakhot khong satri Thai” (The past, present, and future of Thai women),10) he used Marxist theory to analyze the social status of Thai women from traditional sakdina to the contemporary period. He pointed out that in Thai feudal society, women were treated only as providing men with sexual pleasure and as servants, and despite the rise of the middle class following the regime change in 1932, the status of Thai women—especially in rural areas—was still undermined by the economic, political, and social monopoly of the ruling class and capitalists. In Jit’s eyes, Thai women had long been exploited and needed to fight for justice (Jit [Somchai] 1979). Although his studies on women under Marxism have their limits and need more explanation with regard to the patrimonial system in Thai society, Jit is regarded as a pioneer in women’s studies who provided a systematic framework for analyzing the social problems of Thai women (Sucheela 1997, 142–143). His work has inspired later generations of scholars to develop more research and theories on women’s studies in Thailand.11)

Jit in Contemporary Thai Politics

Following a coup that overthrew Thaksin Shinawatra in 2006, Thai politics has been trapped in a color-coded polarization between the anti-Thaksin faction, known as the Yellow Shirts, and the pro-Thaksin faction, or the Red Shirts. The Yellow Shirts—consisting mostly of the urban middle class—are led by the People’s Alliance for Democracy (PAD) and the aristocratic Democrat Party and attempt to protect the monarchy and democracy from Thaksin’s family politics and alleged corruption. On the other hand, the Red Shirts—led by the United Front for Democracy against Dictatorship (UDD), Thaksin’s representatives—are formed mostly of low-income grassroots citizens in the northeast region who have been mobilized and view themselves as commoners fighting for democracy and justice against the aristocrats.12) This yellow and red polarization presents not only a political divide but also the division between the urban middle class and the rural grassroots that has long existed in Thai society—as some have pointed out, a “crisis of identity” (Nostitz 2009).

In this scenario, Jit’s image as a warrior who stands beside weak and marginalized people has been utilized again, interestingly by both the Yellow Shirts and the Red Shirts. In the protest against the Thaksin regime in 2005 and 2006, the Yellow Shirts-PAD acted upon their slogan to “fight (the tyranny) for our King” while denying the existing democracy. To reinforce their patriotism, they sang many songs—including Jit’s “Saengdao haeng sattha”—that were once sung by the CPT and leftist students back in the 1970s. Ironically, the PAD compared “the stars” to the King without realizing that the composer of the song was actually anti-monarchy (Prachak 2015, chapter 10)!

Similarly, when the Red Shirts and UDD protested against the military dictatorship and military-backed Abhisit government in 2006–10, causing many casualties, Jit’s song was sung among other revolutionary songs, as a symbol of the “people’s revolution” and “democratic fighters” against dictatorship. The image of Jit was used this time to fit in with the UDD’s political discourse of “commoners (or subjects) against aristocrats,” or commoners overthrowing aristocrats. Pictures, posters, and books of Jit together with those of other legendary socialists such as Nai Phee and Pridi Phanomyong were sold at the protest site, a scenario similar to the October 14 student uprising. As a result, together with speeches by its key members and other methods, the UDD was able to mobilize over 10,000 people each time it held a demonstration. Not only rural commoners but a number of urban middle-class people also joined the protest.

Furthermore, following Prayuth’s military regime, which ousted the Yingluck government in May 2014, a number of anti-coup groups were arrested under different charges including lèse-majesté. Among them, a group called New Democracy recently marched to a police station demanding the release of a woman who was suspected of lèse-majesté and put in jail with other suspects. Her son, who was a police officer, and other supporters lit candles and sang “Saengdao haeng sattha.”13) Under these circumstances, it is notable that regardless of Jit’s true purpose, his song has become a symbol of dissidents fighting for justice against the authorities, and he himself has been made a “free-floating signifier” by different political dissidents (Chusak 2014, 63–64).

The (Ironically) Changing Image

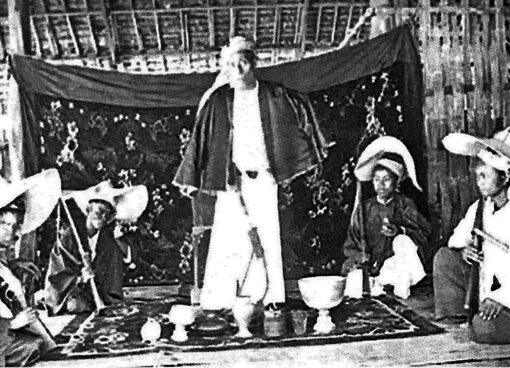

As part of an attempt to construct local identity in many parts of Thailand in recent years, Jit’s image ironically changed from a Communist threat to an important figure in Sakonnakhorn Province, once a stronghold of the CPT. The village where he was killed and his statue there became attractions, drawing not only locals but also tourists who passed by.14) In Nongkung village, where he was killed, a group of activists and academics built a statue commemorating him 47 years after his death. At the same time, a big billboard sign saying “Jit Phumisak Memorial Road” was built at the entrance of the village by the Sakonnakhorn Provincial Administration Organization. Villagers reportedly hold an event to commemorate his death every year on May 5.15) Moreover, more than 30 years after his death Jit was recognized again, this time by the local people—not only as an intellectual, but surprisingly as a “sacred spirit” who gave hints for the underground lottery. Locals respectfully call him “Achan Jit” (Teacher Jit) or “Chaopho Jit,” a term for someone of power and influence, or part of the Mafia. People coming for a lottery hint worship him with cigarettes and a certain brand of beer, which they believe are his favorites.16)

This paper has examined some of Jit’s biographies and the creation of his image by different actors from the 1950s to recent years. All in all, what is Jit’s influence and legacy for the younger generation of Thais? Suffice it to say that he remains a cultural icon for political antagonists, especially in an era of a military regime. Jit might not be regarded as Thailand’s most influential writer compared to the award-winning Kukrit Pramoj, but for a certain group of people—especially those who joined the student uprising in 1973 and those who went into the jungles after October 1976—he remains a legendary figure from an intellectual as well as political stance. It can also be noted that, though not directly, Jit’s life has inspired people to fight for democracy and the rights of free speech, as we can see from the case of an independent and non-profit Web newspaper like Prachathai.17) Similarly, in 2006 Samesky (Fa-deokan) publishing house was founded as an attempt to publish thought-provoking books about politics and history, especially the October 1973 uprising and its repercussions.18) Despite sporadic state censorship and pressure, these alternative media continue to serve as a platform for the anti-authoritarian movement and demands for freedom of the press. Despite its low profile and limited budget, Prachathai has gained a number of readers and supporters during the past 10 years. Jit’s discourse on social justice might often be neglected by the contemporary social resistance movement, as some suggest (Kengkit 2014, 117–137), but as long as political struggle continues in Thailand, Jit and his various images will undoubtedly continue to be remembered and live among anti-government dissidents. That is probably his true legacy.

Accepted: December 11, 2017

References

In English

Flood, Thadeus. 1975. The Thai Left Wing in Historical Context. Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars/Critical Asian Studies 7(2): 55–67.

Kasian Tejapira. 2001. Commodifying Marxism: The Formation of Thai Radical Culture 1927–1958. Kyoto Area Studies on Asia, Vol. 3. Kyoto: Kyoto University Press; Melbourne: Trans Pacific Press.

Nostitz, Nick. 2009. Red vs. Yellow, Vol. 1: Thailand’s Crisis of Identity. Bangkok: White Lotus.

Reynolds, Craig. 1987. Thai Radical Course: The Real Face of Thai Feudalism Today. New York: Southeast Asia Program, Cornell University.

Reynolds, Craig; and Hong, Lysa. 1983. Marxism in Thai Historical Studies. Journal of Asian Studies 43(1): 77–104.

Somsak Jeamteerasakul. 1993. The Communist Movement in Thailand. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Monash University.

Thongchai Winichakul. 2002. Remembering/Silencing the Traumatic Past. In Cultural Crisis and Social Memory: Modernity and Identity in Thailand and Laos, edited by Shigeharu Tanabe and Charles F. Keyes, pp. 243–283. London: RoutledgeCurzon.

In Thai

Chusak Patarakulwanich ชูศักดิ์ ภัทรกุลวณิชย์. 2014. Jit Phumisak nai khwamsongcham khnong krai lae yangrai จิตร ภูมิศักดิ์ ในความทรงจำของใครและอย่างไร [Jit Phumisak in whose memory and how?]. In Jit Phumisak: Kwamsongcham lae khon runmai จิตร ภูมิศักดิ์ ความทรงจำและคนรุ่นใหม่ [Jit Phumisak: Memory and new generation: Collected articles in the seminar “80 years of Jit Phumisak”], edited by Suthachai Yimprasert สุธาชัย ยิ้มประเสริฐ, pp. 34–71. Bangkok: Jit Phumisak Foundation.

Ja New nam rong phleng “Saengdao haeng sattha” chut thien na Kongprappram จ่านิวนำร้องเพลง “แสงดาวแห่งศรัทธา จุดเทียนหน้ากองปราบปราม [Second Lieutenant New, lighting candles, sang with his supporters “Saengdao haeng sattha” in front of Police Department]. 2016. Prachachat Thurakit Newspaper. May 7. http://www.prachachat.net/news_detail.php?newsid=1462627788, accessed August 4, 2016.

Jit Phumisak จิตร ภูมิศักดิ์. 1994. Bot wikro moradok wannakadi Thai บทวิเคราะห์มรดกวรรณคดีไทย [Analytic essays on the heritage of Thai literature]. Bangkok: Sayam (reprinted from the 1980 version).

Jit Phumisak [Sithi Sisayam] จิตร ภูมิศักดิ์ [สิทธิ ศรีสยาม]. 1975. Nirat Nongkhai: Wannakadi thi thuk sang phao นิราศหนองคาย วรรณคดีที่ถูกสั่งเผา [Nirat Nongkhai: Literature that was ordered to be burned]. 2nd ed. Bangkok: Phinong Saengtham.

Jit Phumisak [Somchai Preechacharoen] จิตร ภูมิศักดิ์ [สมชาย ปรีชาเจริญ]. 1979. Adit patchuban lae anakhot khong satri Thai อดีต ปัจจุบันและอนาคตของสตรีไทย [The past, present, and future of Thai women]. In Prawatsat satri Thai ประวัติศาสตร์สตรีไทย [The history of Thai women], edited by Kulap Saipradit กุหลาบ สายประดิษฐ์ et al., pp. 83–161. Bangkok: Chomrom Nangsu Saengdao.

Ken Sarika เคน สาริกา. 2013. Ban Nong Kung Pho So 2556: Manut song na บ้านหนองกุง พ.ศ 2556: มนุษย์สองหน้า [Ban Nong Kung village in 2013: Two-faced figure]. Komchadluek Newspaper. April 25. http://www.komchadluek.net/news/scoop/156881, accessed August 8, 2016.

Kengkit Kitiriangrap เก่งกิจ กิติเรียงลาภ. 2014. Khwammai lae thana khong Jit Phumisak: Rao cha chotcham khao yangrai ความหมายและฐานะของจิตร ภูมิศักดิ์: เราจะจดจำเขาอย่างไร [The meaning and importance of Jit Phumisak: How should we remember him?]. In Jit Phumisak: Kwamsongcham lae khon runmai จิตร ภูมิศักดิ์ ความทรงจำและคนรุ่นใหม่ [Jit Phumisak: Memory and new generation: Collected articles in the seminar “80 years of Jit Phumisak”], edited by Suthachai Yimprasert สุธาชัย ยิ้มประเสริฐ, pp. 116–139. Bangkok: Jit Phumisak Foundation.

Prachak Kongkirati ประจักษ์ ก้องกีรติ. 2015. Kanmueang wattanatham Thai wa duay khwamsongcham watak ham lae amnat การเมืองวัฒนธรรมไทยว่าด้วยความทรงจำ วาทกรรมและอำนาจ [Thailand political culture: Memory, discourse, and power]. Bangkok: Sameskybooks.

Samanchan Phuthachak สมานฉันท์ พุทธจักร. 2016. Hasip pii kan chakpai khong Jit Phumisak, chak ‘Phii Baihuey’ suu Achan Jit 50 ปีการจากไปของจิตร ภูมิศักดิ์ จาก ‘ผีใบหวย’ ถึง ‘อาจารย์จิตร’ [Fifty years after Jit Phumisak’s death: From Lottery-hinting Ghost to Achan Jit]. Prachathai Online Newspaper. May 4. http://prachathai.com/journal/2016/05/65617, accessed May 5, 2016.

Samosorn Nisit Chulalongkorn Mahawitthayalai สโมสรนิสิตจุฬาลงกรณ์มหาวิทยาลัย. 1953. Nangsu Mahawitthayalai Chabap 23 Tulakhom 2496 หนังสือมหาวิทยาลัย ฉบับ 23 ตุลาคม 2496 [Mahawitthayalai yearbook 23 October 2496]. Bangkok: Chulalongkorn University.

Sucheela Thanchainan สุชีลา ตันชัยนันท์, ed. 2014a. Jit Phumisak lae vivata rueang phet saphawa nai sangkom Thai จิตร ภูมิศักดิ์และวิวาทะเรื่องเพศสภาวะในสังคมไทย [Jit Phumisak and discourse on gender in Thai society]. Bangkok: P Press.

―. 2014b. Phuying nai thasana khong Jit Phumisak ผู้หญิงในทัศนะของจิตร ภูมิศักดิ์ [Women in the eyes of Jit Phumisak]. In Jit Phumisak: Kwamsongcham lae khon runmai จิตร ภูมิศักดิ์ ความทรงจำและคนรุ่นใหม่: รวมบทความในโอกาสสัมมนาในงาน 80 ปีของจิตร ภูมิศักดิ์ [Jit Phumisak: Memory and new generation: Collected articles in the seminar “80 years of Jit Phumisak”], edited by Suthachai Yimprasert สุธาชัย ยิ้มประเสริฐ, pp. 337–363. Bangkok: Jit Phumisak Foundation.

―. 1997. Phuying ni thasana Jit Phumisak lae naewkhit satrii suksa ผู้หญิงในทัศนะของจิตร ภูมิศักดิ์และแนวคิดสตรีศึกษา [Women in the eyes of Jit Phumisak and theory of women’s studies]. Bangkok: Paluk.

Suthachai Yimprasert สุธาชัย ยิ้มประเสริฐ. 2006. Nithayasan Aksornsan kab khabuankan sangkhomniyom Thai (2492–2495) นิตยสารอักษรสาส์นกับขบวนการสังคมนิยมไทย (พ.ศ.๒๔๙๒ -๒๔๙๕) [Aksornsan journal and socialism movement in Thailand 1949–53]. In Chak Aksornsan thueng Sangkhomsat Prarithat จากอักษรสาส์นถึงสังคมศาสตร์ปริทัศน์ [From Aksornsan to Social Science Review], edited by Narong Phetprasert ณรงค์ เพ็ชรประเสริฐ, pp. 115–167. Bangkok: Center of Economics and Political Studies, Chulalongkorn University.

Thikan Srinara ธิกานต์ ศรีนารา. 2014. Kankitkan khwam pen Communist ook jak Jit Phumisak lang Phokhotor การกีดกันความเป็นคอมมิวนิสต์ออกจากจิตร ภูมิศักดิ์หลังพคท [Deconstruction of the Communist image of Jit Phumisak after the CPT]. In Jit Phumisak: Kwamsongcham lae khon runmai จิตร ภูมิศักดิ์ ความทรงจำและคนรุ่นใหม่: รวมบทความในโอกาสสัมมนาในงาน 80 ปีของจิตร ภูมิศักดิ์ [Jit Phumisak: Memory and new generation: Collected articles in the seminar “80 years of Jit Phumisak”], edited by Suthachai Yimprasert สุธาชัย ยิ้มประเสริฐ, pp. 140–176. Bangkok: Jit Phumisak Foundation.

Villa Vilaithong. วิลลา วิลัยทอง. 2013. “Thanthakarn” khong Jit Phumisak lae phutongkhang thang kanmueang “ทัณฑะกาล” ของจิตร ภูมิศักดิ์และผู้ต้องขังการเมือง [Years in prison of Jit Phumisak and political prisoners]. Bangkok: Matichon.

Wichai Wipharasami วิชัย นภารัศมี, ed. 2009. Khon yang khong yinden doi thathai: Chak Mahawitthayalai Latyao thueng wara sutthai khong chiwit คนยังคงยืนเด่นโดยท้าทาย จากมหาวิทยาลัยลาดยาวถึงวาระสุดท้ายแห่งชีวิต [Collected poems and articles of Jit Phumisak from prison years to the last period in his life]. Bangkok: Sameskybooks.

―, ed. 2007. Dondan dumdiao khondiaodae: Khrongkan sanniphon Jit Phumisak ด้นดั้นดุ่มเดี่ยวคนเดียวแด. โครงการสรรนิพนธ์ จิตร ภูมิศักดิ์ [Collected poems by Jit Phumisak]. Bangkok: Sameskybooks.

―, ed. 2003. Lai chiwit Jit Phumisak หลายชีวิต จิตร ภูมิศักดิ์ [Many lives, Jit Phumisak]. Bangkok: Sameskybooks.

1) Samosorn (1953); Prachak (2015, 150–158).

2) The Party evolved from the Communist Party of Siam, the earliest form of a Communist Party in Thailand. It was established in 1930 by Chinese migrants in Thailand but was dissolved in 1936. For further information, see Somsak (1993) and Kasian (2001).

3) The journal was later criticized by the Right as being too radical and by the Left for being insufficiently militant. Most writers—both right wing and left wing—deserted the journal.

4) Aksornsan 2(1) (2493) (1950). The title on the front page reads “Does Lilit Phralor Lead People Astray?” (Suthachai 2006, 157).

5) For example, Asanee Pholchan, or Nai Phi. Jit’s argument on the function of art that should reflect lives of the working class in Art for Life, Art for the People, the only book published when he was alive, was influenced by earlier writers in the magazine.

6) Aksornsan 4(1) (2495) (1953). The title on the front page reads “The Real Story of Ah Q by Lu Xun.”

7) “The Real Face of Thai Feudalism Today” was first published in the journal Nitisat in 1957 and then banned, and was reprinted several times—in 1974, 1977, and 1979. Thiphakorn was also first published in 1957 and reprinted in 1974 and 1978. Collected Poems and Literary Reviews by “Political-Poet” was first printed in Prachatipatai newspaper in 1964 and reprinted in 1974 by Naew Ruam Naksuksa Chiangmai (Chiang Mai). For further information, see Reynolds (1987, 177) and Somsak (1993, 26).

8) The key figure who spread Jit’s image as a revolutionary was one of the CPT’s members, Manot Meethangkool, or Uncle Prayote, who had a personal relationship with Jit’s family. For further information, see Somsak (1993, 28), Chusak (2014), and Thikan (2014).

9) For example, Phasa lae nirukkatisat (Linguistics and etymology) (Bangkok: Duang Kamol) was published in 1979 by the editors of the Lok nangsu Journal; Ongkan Chaengnam lae khokhitmai nai prawattisat Thai lumnam Chaophraya (The oath of allegiance and new thoughts on Thai history in the Chaophraya Basin) (Duang Kamol) was published in 1981 by Suchat Sawatsi; and Sangkhom Thai lum Maenam Chaophraya kon samai Si-Autthaya (Thai society in the Chaophraya river basin before the Ayutthaya period) (Bangkok: Mai-ngam) was published in 1983 by Wichai Napharasami (Thikan 2014, 160–161).

10) Jit [Somchai] (1979).

11) For example, Sucheela Tanchainan’s studies examine Jit’s works and his discourse on the role of women and how they inspire the present status of gender studies in Thailand. See Sucheela (2014a; 2014b).

12) UDD leaders used this discourse as a slogan to mobilize their supporters, but their discourse remains ambiguous as to who belongs to the aristocratic class and who belongs among the commoners.

13) Ja New nam rong phleng “Saengdao haeng sattha” chut thien na Kongprappram (2016).

14) Special report, Samanchan (2016).

15) Ken (2013).

16) Special report, Samanchan (2016).

17) Founded in 2004, Prachathai does not only provide news and information to the Thai public under strict state censorship, it is also a platform for alternative political and cultural ideas not welcomed by the mainstream media.

18) The publisher plays a leading role in collecting and reprinting Jit’s old monographs and discovering new ones. Six volumes have been published since 2004 under the project titled “Krongkan Sanpaniphon Jit Phumisak” (Collection of Jit Phumisak monographs), edited by Wichai Wipharasamee.