Contents>> Vol. 7, No. 3

Domination, Contestation, and Accommodation: 54 Years of Sabah and Sarawak in Malaysia

Faisal S. Hazis*

*Institute of Malaysian and International Studies, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 43600 Bangi,

Selangor D.E., Malaysia

e-mail: faisalhazis[at]ukm.edu.my

DOI: 10.20495/seas.7.3_341

This article traces the major contestations that have taken place in Sabah and Sarawak throughout the 54 years of their independence. The two major areas of contestation are state power and local resources, pitting federal leaders against Sabah and Sarawak’s elites. These contestations have forced the federal government to accommodate the local elites, thus ensuring the stability of Barisan Nasional (BN) rule in the East Malaysian states. However, Sabah and Sarawak elites are not homogeneous since they have different degrees of power, agendas, and aspirations. These differences have led to open feuds between the elites, resulting in the collapse of political parties and the formation of new political alignments. Over almost four decades, a great majority of the people in Sabah and Sarawak have acceded to BN rule. However, in the last decade there have been pockets of resistance against the authoritarian rule of BN and the local elites. This article argues that without accountability and a system of checks and balances, the demand for more autonomy by the increasingly vocal Sabah and Sarawak elites will benefit only them and not the general public.

Keywords: East Malaysian politics, Sabah and Sarawak, domination, contestation, elites

Introduction

The ruling Barisan Nasional (BN) has dominated Sabah and Sarawak politics for more than four decades. To maintain its political dominance, the party has resorted to a strategy of accommodation and repression (Chin 1996; Crouch 1996; Chin 1997; Loh 1997; Mohammad Agus 2006; Lim 2008; Faisal 2012). However, this strategy is not unique to the East Malaysian states, i.e., Sabah and Sarawak. The ruling party has adopted a similar approach throughout the federation, albeit with little success in states such as Kelantan and recently (since 2008) Penang and Selangor.

Popularly known as BN’s vote bank, Sabah and Sarawak tend to be viewed merely as subjects of the federal government’s domination that lack the power and capacity to challenge and resist. However, in the last few years East Malaysian leaders and some members of the public have been vocal in challenging the federal government. They have been demanding autonomy and state rights (Channel NewsAsia 2015), while a small group of the population is openly calling for secession (Star 2014a). When Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS), supported by the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), wanted to table a private member’s bill to amend the sharia courts (Criminal Jurisdiction) 1965, Sarawak leaders openly objected to the move. This was an unprecedented move of resistance against the federal government (Star 2017).

Over the last decade, the East Malaysian states—especially Sarawak—have been openly challenging the federal government due to their elevated importance in national politics and the weakening power of the federal government. Without the parliamentary seats that Sabah and Sarawak BN won in the 2008 and 2013 general elections, the long rule of BN at the federal level would have ended. Thus, the two East Malaysian states have the capacity to be kingmakers and shape the trajectory of Malaysian politics.

Despite the long BN rule in Sabah and Sarawak, the two states have experienced many episodes of contestation that shaped the nature of politics at both the federal and state levels. This paper traces the major contestations that have taken place in the East Malaysian states throughout the 54 years of their independence. The two major areas of contestation are state power and local resources, pitting federal government leaders against Sabah and Sarawak’s elites. These contestations have forced the federal government to accommodate the local elites, thus ensuring the stability of BN rule in the East Malaysian states. However, Sabah and Sarawak elites are not homogeneous since they have different degrees of power, agendas, and aspirations. These differences have led to open feuds between the elites, resulting in the collapse of political parties and the formation of new political alignments. Over almost four decades, a great majority of the people in Sabah and Sarawak have acceded to BN rule. However, in the last decade there have been pockets of resistance against the authoritarian rule of BN and the local elites. This paper argues that without accountability and a system of checks and balances, the demand for more autonomy by the increasingly vocal Sabah and Sarawak elites would benefit only them and not the general public.

Sabah and Sarawak before Malaysia

The idea to organize Malaya, Singapore, Brunei, North Borneo (known as Sabah after the formation of Malaysia in 1963), and Sarawak into some form of union had been voiced by the British as early as 1887 (Ongkili 1972). The proposal was motivated by the need to protect the future of British interests in the Far East rather than by any aspiration to encourage self-government in the region. The prime minister of Malaya, Tunku Abdul Rahman, again mooted the idea of a merger in May 1961. The response to the Malaysia proposal in North Borneo and Sarawak differed largely along ethno-religious lines (Cobbold Commission 1962). In North Borneo the largest non-Muslim native political party, United National Kadazan Organisation, and the only Muslim party, United Sabah National Organisation (USNO), supported the idea of Malaysia because they felt that it would safeguard the interests of the natives and Muslims against the educationally and economically superior Chinese. The other parties, however, expressed greater reservations regarding the proposal. The National Pasok Momogun Organisation (Pasok Momogun), which comprised mainly non-Muslim Dusun and Murut, opposed the proposal because it viewed it as hasty and preferred a gradual transition from British colonial administration to self-governance for North Borneo. The Democratic Party, the United Party, and the Liberal Party (multiethnic parties but dominated by Chinese) shared similar views with the Pasok Momogun with regard to self-government in North Borneo (Lim 2008).

In Sarawak the main opponents of the Malaysia proposal were the left-wing Sarawak United People’s Party’s (SUPP) and the Communist Clandestine Organisation. The Communists were well aware that Malaysia’s success would present a danger to them (Chin 1996, 80). On the other hand, support for the federation came mostly from the Malay communities, as evident from the endorsement given by the two dominant Malay parties, Parti Negara Sarawak and Barisan Rakyat Jati Sarawak, to the Malaysia proposal. The Iban, on the other hand were too inexperienced in politics to understand the true meaning of a federation and were consequently liable to be manipulated by all sides (ibid., 60).

The biggest and most serious internal challenge to the idea of Malaysia came from the northern part of Sarawak. The Brunei Revolt in 1962 was a failed uprising against the British by A. M. Azahari’s Brunei People’s Party and its military wing, the North Kalimantan National Army (TNKU, Tentera Nasional Kalimantan Utara), who opposed the Malaysian Federation. Instead, they wanted to create a Northern Borneo state comprising Brunei, Sarawak, and North Borneo. The TNKU planned to attack the oil town of Seria—its police stations and government facilities. However, the attack was stopped within just a few hours of its launch (Harry 2015).

To determine whether the people of North Borneo and Sarawak supported the Malaysia proposal, a Commission of Enquiry led by Lord Cameron Cobbold was established in 1962. The commission concluded that about one-third of the population in both territories strongly favored the early realization of Malaysia without too much concern about the terms and conditions. Another third, many of them favorable to the Malaysian project, asked with varying degrees of emphasis for conditions and safeguards. The remaining third was divided between those who insisted on independence before Malaysia was considered and those who strongly preferred to see British rule continue for some years to come (Cobbold Commission 1962). There remained a hard core, vocal and politically active, that opposed Malaysia on any terms unless it was preceded by independence and self-government. This hard core might have amounted to nearly 20 percent of the population of Sarawak and somewhat less in North Borneo (Wong 1995). However, Chin Ung-Ho (1996) argues that the commission was hardly impartial as its members were all nominated by the British and Malayan governments, which vehemently supported the formation of Malaysia. Nonetheless, the Cobbold Commission report was an important part of the process by which the agreement to form the Federation of Malaysia was reached. It was generally agreed that the states of Malaya, Singapore, and Borneo would form a federation.

In accordance with the commission’s report, the Inter-Governmental Committee consisting of representatives from the British and Malayan governments, North Borneo, and Sarawak was established. They were tasked with working out the future constitutional arrangements and the necessary safeguards that formed the basis of the Malaysia Agreement signed on July 8, 1963. These safeguards included, inter alia, complete control over the states’ natural resources like land, forests, minerals both onshore and off-shore; local government; immigration; use of the English language in judicial proceedings; state ports; and more sources of revenue being assigned to the Borneo states. The safeguards were later known as Twenty Points for Sabah and Eighteen Points for Sarawak. They were eventually incorporated or embedded in the Federal Constitution and also into crucial legislation such as the Immigration Act 1963 (Chin 1997). However, after independence the safeguards were gradually eroded, prompting a long and continuous struggle to reclaim them (Lim 1997).

The proposal to form Malaysia did not go well with neighboring countries, particularly Indonesia and the Philippines (Milne 1963; Chin 1997). Indonesia under President Suharto saw the formation of the federation as neocolonialism. Sukarno’s principles did not augur well with the creation of the federation and resulted in the Ganyang Malaysia (Crush Malaysia) campaign. This period, which was also known as Konfrontasi (Confrontation), lasted from 1963 to 1966. The Philippines, on the other hand, declared its claim over North Borneo in 1962 under the leadership of President Diosdado Macapagal. To date, this claim has not changed. To avoid any further confrontation, the leaders of Malaya, Indonesia, and the Philippines met in Manila in June 1963. The meeting resulted in the Manila Accord, signed on July 31, 1963, which was followed by the Manila Declaration signed on August 3, 1963 and Joint Statement signed on August 5, 1963. The leaders agreed to submit the Borneo case to the secretary-general of the United Nations (UN) for assessment of public opinion in North Borneo and Sarawak (Milne 1963).

The UN began work in mid-August 1963 to assess the response of the people of North Borneo and Sarawak. This situation delayed the scheduled date of August 31, 1963 to officially declare the Federation of Malaysia. The findings of the UN team coincided with the outcome of the Cobbold Commission whereby the people of both states were supportive of the federation. However, the outcome did not sit well with Indonesia and the Philippines. The confrontation with Indonesia escalated with cross-border military attacks in North Borneo and Sarawak as well as in Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore in 1964. The campaign slowly de-escalated by 1965 and 1966 (ibid.). However, the Philippines has yet to relinquish its claim on Sabah and intermittently uses it to hype national sentiments during election campaigns and rallies. Chin (1996) argues that colonial officials and elected state leaders swayed the UN Commission, thus ignoring the substantial anti-Malaysia forces. Nonetheless, the Federation of Malaysia was formed on September 16, 1963, minus Brunei. The small kingdom decided not to join Malaysia, largely due to disagreements over the federal-state government division of its oil revenue, the Sultan’s status vis-a-vis the peninsular rulers, and the Sultan’s eligibility to be elected as the head of state of the federation (Mohammad Agus 2006).

Establishing the “Rules of the Game”: Post-Independence Politics in Sabah and Sarawak

The early years of Malaysia was a period of considerable political turbulence, as the local elites competed against the federal government and each other to establish the rules of the game. Although there were no written or implicit rules to guide the elites in East Malaysia, the political crisis in post-independence Sabah (known as North Borneo before the formation of Malaysia) and Sarawak indirectly spelled out the federal government’s demands on the elites. These demands were subsequently agreed on as the rules of the game. Among these demands were: (1) to safeguard national interests over state interests, (2) to maintain Malay Muslim political dominance, (3) to ensure BN’s continued dominance in the state and parliamentary elections, (4) to transfer the rights to extract the state’s natural resources to the federal government, and (5) to provide political stability (Faisal 2012, 83). In return for fulfilling these demands, the federal government would give a certain degree of freedom to the local elites to exercise their control over local politics, the state economy, and the populace. But if the local elites failed to adhere to the rules, the federal government would intervene in the affairs of the state, thus restoring the federal government’s control (Chin 2014).

In post-independence Sabah and Sarawak, the local elites strived to safeguard state autonomy, which ran contrary to the rules of the game, i.e., upholding national interests. When such conflicts occurred, the federal government employed different degrees of intervention, depending on the seriousness of the conflict. James Chin (1997) argues that Kuala Lumpur had three distinct types of intervention at its disposal: “mild intervention,” whereby the federal government co-opted local elites; “mid intervention,” where the federal government took a more direct approach in dealing with the issue at hand; and “direct intervention,” where the federal government ruled Sabah and Sarawak directly by declaring a state of emergency.

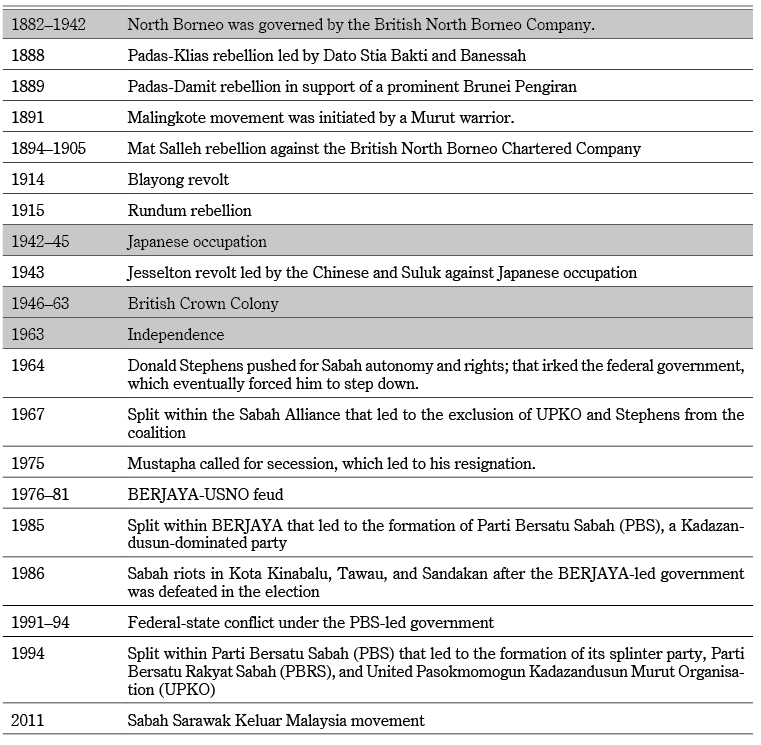

Post-independence Sabah was dominated by two elites, Mustapha Harun representing the Muslims and Donald Stephens (who later became Tun Fuad Stephens) representing the Kadazan-Dusuns (Chin 1997). When the Alliance government was formed in 1963, Mustapha became the governor while Stephens assumed the position of chief minister. The two powerful elites attempted to dominate the state, thus paralyzing the state government. Under the Sabah state constitution the governor had to give his assent to enactments passed by the State Legislative Assembly, but in many cases Mustapha withheld his assent, causing administrative delay (ibid.). The federal government sided with Mustapha, who was seen to be an extension of Malay Muslim political dominance in the state (Loh 1997). Hence, the federal government’s support for Mustapha was crucial for his plan to remove Stephens and become chief minister. At that crucial time Stephens increasingly defended Sabah’s autonomy and rights, thus becoming a source of concern for the federal government (Lim 1997). As the crisis deepened, Stephens was reluctantly asked to relinquish his position to Peter Lo from the Sabah Chinese Association (SCA) and took up a federal cabinet post. In the 1967 elections the Mustapha-led USNO and the SCA managed to capture 19 of the 32 assembly seats, enough to form a government with the exclusion of United Pasokmomogun Kadazandusun Murut Organisation (UPKO), which managed to secure only 12 seats (Loh 1992). After the elections Mustapha became the third chief minister of Sabah, thus cementing Malay Muslim political dominance in the state. Federal-state relations improved during Mustapha’s term as chief minister, but that did not last long. Unintentionally, the federal government had created a very powerful elite that they themselves found difficult to contain. Mustapha exploited his position to amass a tremendous amount of wealth and exercise authoritarian power over the people of Sabah. On top of that, Mustapha angered the federal government by refusing to allow British military exercises in Sabah despite previous agreement by Kuala Lumpur. Another major issue was Mustapha’s continued support for armed rebellion in the Southern Philippines, which could undermine national security (Lim 2008).

In 1975 Mustapha hardened his stance against Kuala Lumpur by circulating a memorandum on April 23 titled “The Future Position of Sabah in Malaysia,” where he argued that Sabah would be better off financially as an independent country. The federal government, however, did not directly force Mustapha to step down despite the chief minister’s bold call for secession (Chin 2014). Instead, it sponsored the formation of a new party, the Sabah People’s United Front (BERJAYA), to challenge Mustapha and USNO. Mustapha’s vice president in USNO, Harris Salleh, turned against him and led the new party. The federal government even encouraged Stephens to resign from his governorship and join Harris to lead BERJAYA (ibid.). As Gordon Means (1991) observes, Prime Minister Abdul Razak did not take a confrontational approach in dealing with the East Malaysian elites. Instead, he used the strategy of accommodation by co-opting other elites to subdue Mustapha.

BERJAYA and USNO were both members of BN at the federal level, but at the state level USNO was determined to challenge BERJAYA by occupying the opposition bench. Whilst solidarity within BN was expected from both parties, there was no way the two could work together easily, as there remained USNO supporters within UMNO and also the coalition more broadly. The BERJAYA-USNO rivalry came to a halt when BERJAYA was decisively defeated in the 1976 elections and Stephens became the new chief minister (Mohammad Agus 2006). Unfortunately, Stephens died a year later in a plane crash and was succeeded by Harris (Chin 2014).

After Mahathir became the prime minister in 1981, he pursued an Islamization drive in order to subdue PAS’s increased influence over the Malays. In line with the federal government’s Islamization drive, the BERJAYA-led government in Sabah also did the same, thus undermining its multiethnic character. This trend irked some non-Malay leaders in BERJAYA who later formed a splinter party, Parti Bersatu Sabah (PBS), led by Pairin Kitingan. In the 1985 elections, PBS won 25 seats while USNO made a strong comeback by winning 16 seats. BERJAYA, on the other hand, managed to retain only six seats and PASOK won one seat (Mohammad Agus 2006). Despite PBS’s victory, BERJAYA was able to pressure the governor to swear in Mustapha as the new chief minister. Mustapha’s rule was short-lived because the federal government soon intervened and publicly declared its support for a PBS-led government (Chin 2014). A day later, Pairin was sworn in.

Under the PBS government federal-state relations remained strained, with PBS more willing than other BN parties to speak out against federal government policies. PBS did not set itself up in direct opposition to the BN coalition in Kuala Lumpur and repeatedly avowed its intention to seek entry to the coalition should it win the election. With only a slim majority in the state assembly and facing legal challenges from Mustapha and Harris and harassment from federal agencies, Pairin decided to call for a snap election in 1986. Pairin won decisively, capturing a majority of the votes and two-thirds of the assembly seats. Faced with such a clear mandate, the federal government admitted PBS to the coalition (Mohammad Agus 2006).

In the 1990 elections Pairin withdrew from BN after the nominations for the election had closed, thus denying BN the chance to field alternative candidates against PBS. PBS retained Sabah, but the federal government came down hard on the PBS-led government. Barely a month after the election, one of Pairin’s top aides, Maximus Ongkili, was briefly detained under the Internal Security Act (ISA) for alleged involvement in a secession plan. In the following days, Pairin himself was charged on a minor count of corruption and a number of other PBS leaders—including Pairin’s deputy chief minister, Yong Teck Lee—were arrested for participating in an illegal demonstration prior to the election. In 1991 Jeffrey Kitingan was detained under the ISA on charges of secessionism. Federal revenue to Sabah was reduced to a minimum, and a ban was imposed on logging exports from the state (Loh 1997).

PBS responded by reapplying to join BN, but Mahathir was in no mood to accommodate Pairin. At that same time, a spate of defections by PBS leaders began. But the state’s Anti-Hopping Law prevented defections by sitting state assemblymen, which BN challenged in the Supreme Court. PBS passed a second law allowing it to expel state assemblymen on the grounds of “indiscipline, abuse, or betrayal of electorates’ mandate” (Lim 2008). Shortly after that, the Supreme Court ruled that the original law was indeed unconstitutional and thus void. After Pairin dissolved the state assembly in January 1994, the floodgates opened. The first to go was Deputy Chief Minister Yong, followed by another PBS minister. Yong subsequently formed a new party, the Sabah Progressive Party, which was immediately accepted into BN, while another high-ranking PBS politician, Bernard Dompok, formed his own party, the Sabah Democratic Party. At the same time, UMNO announced that it would contest in the elections and that USNO would be dissolved to pave the way for UMNO’s entry into Sabah (Chin 2014). Despite the defections and the grand promises of development by the national BN, PBS retained control of the state by winning 25 of the 45 seats. Less than a month after the election eight PBS assemblymen defected, thus bringing a close to the PBS government. Upon assuming control of the Sabah government BN introduced a policy of rotating the chief minister every two years, thus allowing Yong and Dompok to be appointed. Over the years, UMNO strengthened its dominance over Sabah politics and subsequently dropped the rotation system. The current Sabah chief minister, Musa Aman, is the longest-serving person in that position, having been at the helm for 14 years. With Musa religiously adhering to the rules of the game, his position as the chief minister is secured and federal-state relations remain cordial.

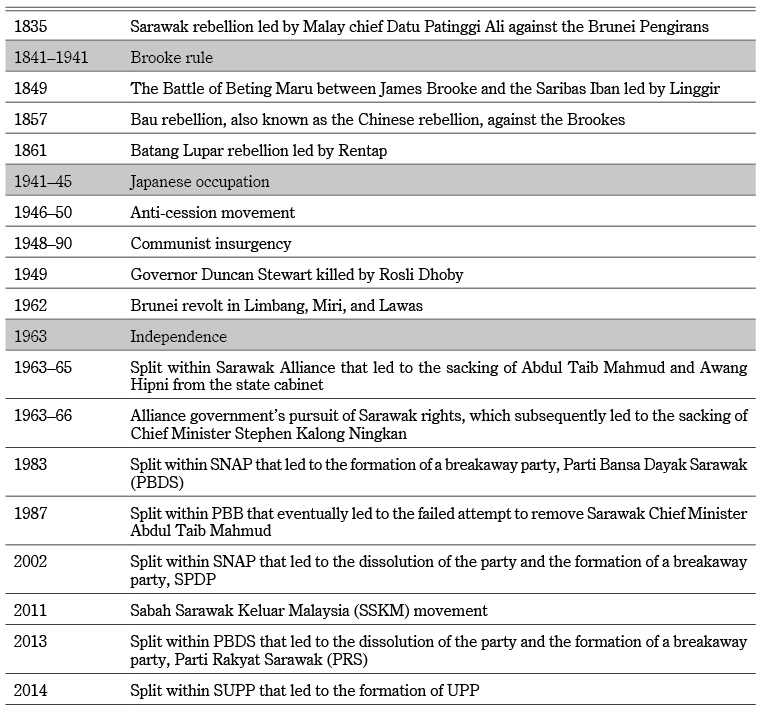

Over in Sarawak, the Iban elites initially dominated the post-independence government but were subsequently replaced by Muslim Bumiputera elites through the federal government’s intervention (ibid.). The main reason for the federal government’s intervention was Chief Minister of Sarawak Stephen Kalong Ningkan’s insistence on championing Sarawak rights and autonomy, thus undermining the rules of the game. Among the issues that upset the federal government were Ningkan’s refusal to implement Malay as the official language, the continued use of English, and the role of expatriate officers in the public service (ibid.). Ningkan’s party, the Sarawak National Party (SNAP), even used the slogan “Sarawak for Sarawakians” in the 1966 elections. In 1966, 21 of the 32 Alliance (ruling coalition) members in the Council Negri (State Legislative Assembly) signed a petition of no confidence in Ningkan as the chief minister. Tunku demanded Ningkan’s resignation, but the latter refused. In response to Ningkan’s snub, Tunku sent the minister of home affairs, the inspector general of police, and the federal attorney general to Kuching to submit a new candidate for the post of chief minister to the governor. Tawi Sli from Parti Pesaka Sarawak (PESAKA) was appointed chief minister on June 17, 1966, but Ningkan challenged the new appointment in court. In September 1966 the court handed down a verdict in Ningkan’s favor, and on September 7 he was reinstated. The federal government swiftly declared a state of emergency on September 15, taking away all Ningkan’s powers. The official reason behind the emergency was the claim that the Communists might take advantage of the situation. After much maneuvering, the Council Negri was convened and a no-confidence motion was passed. Ningkan was dismissed the next day, and Tawi Sli was reinstated (Faisal 2012).

Just like in Sabah, the federal government intervened in Sarawak affairs mainly to safeguard national interests. So when an opportunity came to install a pro-federal government, Tunku acted swiftly. The opportunity came after the 1970 election, when no single party won enough seats to rule Sarawak alone: the pro-federal Bumiputera Party (later known as PBB after its merger with PESAKA) won 12 seats, the opposition SNAP and SUPP had 12 seats each, while PESAKA had eight (Chin 2014). After the 1970 election, Tunku orchestrated the formation of a new Sarawak Alliance led by Rahman Yakub from the Bumiputera Party. With federal government support, Rahman was able to transform himself into a powerful elite who used the chief minister’s office to build a network of patronage and accumulate personal wealth (Faisal 2012). When Rahman administered Sarawak according to the rules of the game, the state went through a period of order and stability. But the stability did not last long, as an internal split within BN Sarawak threatened Rahman’s hold on power. To make things worse for Rahman, the federal government withdrew its support since there was a leadership change at the federal level. Razak accommodated Rahman’s antics, but Hussein Onn—who took over the premiership in 1976—treated the criticism against Rahman quite seriously. There was an attempt by SNAP and SUPP to replace Rahman with SNAP leader Dunstan Endawie, but the plan was halted due to the 1978 election. Feeling insecure, Rahman refused to dissolve the state assembly. This forced Sarawak to have separate parliamentary and state elections (a trend that continues to the present day). Rahman retaliated by allowing the Democratic Action Party to enter Sarawak, thus weakening SUPP. The first Sarawak Muslim Bumiputera chief minister finally stepped down in 1981, citing health reasons (ibid.).

When Abdul Taib Mahmud took over from his uncle Rahman in 1981, he inherited a stable and strong BN. Just like his uncle, Taib religiously adhered to the rules of the game in order to secure the federal government’s support, which was crucial for remaining in power. Apart from that, Taib was able to dominate Sarawak politics because he had massive wealth, was able to keep UMNO out of Sarawak, and was successful in consolidating Muslim Bumiputera support (Chin 2014). Nonetheless, Taib faced a serious challenge to his leadership in the first seven years of his term as chief minister. Surprisingly, the source of contestation came from Rahman. Prior to the feud between Rahman and Taib, the new chief minister had to contain a serious leadership crisis within SNAP due to the retirement of its president, Dunstan Endawie. This paved the way for a battle between two senior party leaders, James Wong and Leo Moggie. Wong subsequently won the presidency, but the defeated Moggie formed a new party, Parti Bansa Dayak Sarawak (PBDS), in 1983. SNAP was a strong party and the biggest threat to Parti Pesaka Bumiputera Bersatu (PBB) prior to its split. But with the split within SNAP, PBB became the largest and most influential party within BN Sarawak. Taib took advantage of the SNAP crisis by co-opting PBDS into Sarawak BN, to the displeasure of SNAP leaders. This move further strengthened Taib’s position.

However, the real test for Taib came when Rahman challenged him through his proxy in PBB and the government. The crisis between Rahman and Taib was due largely to the struggle between two elites who tried to exert their influence and authority over the state. Prior to Taib’s rise to Sarawak’s highest political office, Rahman was the most powerful elite in the state. Through the exploitation of the powerful chief minister’s office and the support of the federal government, Rahman swiftly dominated Sarawak politics, economy, and populace. Since the individual who occupied the powerful chief minister’s office had the greatest amount of power, he or she became the most powerful person in the state. Hence, when Rahman stepped down he actually relinquished his position as the most powerful man without realizing it. Despite losing his power, Rahman was not willing to withdraw from active politics. Taib, on the other hand, refused to let his uncle interfere in the running of the state. This conflict gradually transformed into a major crisis that completely altered the face of Sarawak politics (Faisal 2012).

The uncle-nephew crisis spilled over to PBB, which then became the main battlefield for a proxy war between Rahman’s loyalists and Taib’s supporters. Just like the political crisis in Sabah, the role of the federal government was crucial in determining the victor. In the case of the Rahman-Taib feud, the then Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad sided with Taib, thus giving him the advantage. However, Rahman’s faction continued to attack Taib publicly. In 1985 Rahman wrote a lengthy personal letter to Taib, which was copied to the prime minister. The letter criticized Taib for his “poor political and personal judgement” (Leigh 1974, 183). Rahman ended the letter with the following words:

I venture to suggest that if you find [sic] unable to change from your present thinking and ways of doing things in Sarawak, you had better make an honorable exit. PBB will decide who should be your successor. I don’t intend to fight you. You are too small for me. (Faisal 2012, 129)

However, Taib refused to step down, thus making the uncle-nephew feud a major political crisis in 1987.

On March 9, 1987, four Sarawak ministers and three assistant ministers sent shockwaves throughout the state when they suddenly resigned from the state cabinet. The ministers and deputy ministers were later joined by 20 other state assemblymen who flew to Kuala Lumpur and gathered at the Ming Court Hotel (the crisis was popularly known as the Ming Court Affair), where they announced that they had lost confidence in Taib. The 27 assemblymen were accompanied by Rahman and Moggie, the president of PBDS. The group sent an ultimatum to Taib asking him to resign or face a no-confidence vote. Taib brushed aside their demands and called for a snap election. With the might of the government machinery behind him, Taib managed to win 28 seats, three short of a two-thirds majority, in the Council Negri (Leigh 1974). In consolidating his position, he took both repressive and accommodative measures (Faisal 2012). He terminated the services of local chiefs, disciplined public officials who supported Rahman, revoked timber licenses given to Rahman’s supporters, and advised the federal government to detain several opposition leaders under the ISA. He took the accommodative step of co-opting several opposition assemblymen with the promise of material rewards and political appointments.

Under the Abdullah Badawi leadership, Taib continued to dominate Sarawak politics and maintained cordial federal-state relations. However, after the 1987 crisis he was confronted by a string of leadership crises within the Sarawak BN component parties, starting with SNAP, PBDS, and SUPP. The major reasons behind the internal split within these parties were leadership tussles. Most of them led to the collapse and eventual de-registration of the parties, as in the case of SNAP and PBDS. SUPP managed to survive, but it became a spent force because of the emergence of a rival, the United People’s Party (UPP). The de-registration of SNAP and PBDS paved the way for the emergence of splinter parties, the Sarawak Progressive Democratic Party (SPDP) and Parti Rakyat Sarawak (PRS), which were subsequently admitted to BN. The internal schism continued when SPDP again faced a leadership crisis that led to the formation of another splinter party, the Sarawak People’s Energy Party (TERAS).

Pockets of Resistance: Contesting Strongmen and BN’s Electoral Dominance

For almost six decades, local elites have ruled Sabah and Sarawak with the support of the federal government. Throughout this period, influential leaders have skillfully cajoled the electorate through the use of political patronage and powerful party machinery (Faisal 2015). Despite the elite’s domineering influence, a small group of people resisted the influential leaders, who were deemed increasingly authoritarian, corrupt, arrogant, and out of touch with ordinary people.

In Sabah, Musa’s long rule sparked vocal criticism against his leadership, which was tainted with allegations of corruption and abuse of power. This prompted the opposition to come up with the slogan “Ubah” (Change), which it used nationwide in the 2013 election. Although the opposition in Sabah failed to unseat the incumbent government led by Musa, it was able to win 11 seats—the biggest gain since the era of PBS in the late 1980s and 1990s.

Resentment against arguably the most powerful Sarawak elite, Taib, was reignited in the 2006 and 2011 Sarawak state elections, when the opposition was able to win 9 and 16 seats respectively. Although the ruling BN easily defended its traditional two-thirds majority in the two elections, the significant gain by the opposition dealt a huge blow to Taib. Consequently, the strongman was pressured to step down in 2014. Despite relinquishing his powerful position, Taib did not actually retire from active politics since he immediately assumed the governorship. The ethnic Melanau elite continues to dominate Sarawak politics, albeit in a different capacity. But when another Muslim Bumiputera elite, Adenan Satem, succeeded Taib, the electorate returned to BN’s fold in the 2016 election with the opposition failing to defend the five seats it had won in 2011. As indicated by the 2016 election, the majority of the electorate in Sarawak still supports BN rule. As long as the ruling party remains responsive toward the needs of the populace, it will continue to receive support from the masses. Hence, the issues of corruption, illegal logging, disputes over Native Customary Rights land, inequitable growth, weak institutions, abuse of power, and shrinking democratic space that have plagued Sarawak will not be resolved because the old structure remains intact (see Ngidang 2005; Colchester et al. 2013; SUHAKAM 2013; Straumann 2014).

Rewriting the Rules of the Game: Sabah and Sarawak Politics after the 2008 Political Tsunami

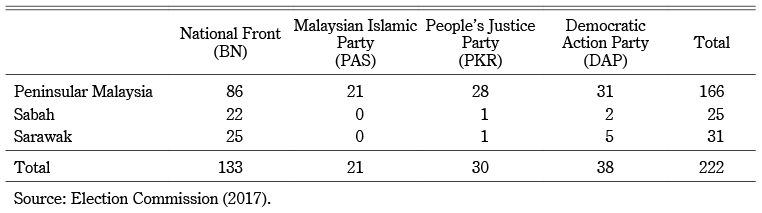

When the rules of the game were being written during the post-independence period, the position of the federal government was strong; this enabled it to dictate the actions of local elites. Hence, when local elites failed to fulfill the federal government’s demands, the government used repressive or authoritarian measures to gain control of the East Malaysian states. However, the 2008 political tsunami had elevated the importance of Sabah and Sarawak in the interplay of national politics. In the past, the federal government could dismiss the voices of East Malaysian elites because it had control over most of the states in the country. However, the 2008 tsunami weakened the federal government because its electoral dominance in the peninsula had been severely challenged. The ruling BN managed to win only 86 seats, 26 short of a simple majority. Hence, without the 47 seats that Sabah and Sarawak BN won in the 2013 elections, the ruling coalition would have lost federal power (see Table 1).

Table 1 Seats Won by Political Parties in the 13th Malaysian General Election

With the new political configuration, the East Malaysian elites are taking advantage of the federal government’s weakened position by pushing to rewrite the rules of the game. The foremost rule that Sabah and Sarawak elites intend to review is the suppression of state rights and autonomy in order to uphold national interests. The majority of people in Sabah and Sarawak believe that the safeguards and special rights that were accorded to them as agreed upon in the Malaysia Agreement 1963 have been taken away by the federal government. As noted earlier, Sabah and Sarawak elites tried to defend state rights during the post-independence period but were thwarted by a strong federal government. However, when the federal government became weak after the 2008 election, the East Malaysian elites revived the struggle to reclaim state rights. Since 2008, Sabah Chief Minister Musa has been calling for greater autonomy and state rights (New Sabah Times 2016). The Sabah chief minister cannot, however, exercise his power as freely as the Sarawak chief minister because the former is still an UMNO member who has to answer to the UMNO president, who is also the prime minister and his political master. Some quarters in Sabah have criticized Musa for not being vocal enough in pushing for Sabah’s autonomy and rights as compared to the Sarawak chief minister (Borneo Post 2016a). The Sarawak chief minister, on the other hand, has been able to push the boundaries in terms of reclaiming state power because he is the president of PBB, the second largest party in Malaysia after UMNO. The late Chief Minister Adenan publicly said that Sarawak was demanding full autonomy where federal powers would be limited only to defense, internal security, and foreign affairs (Free Malaysia Today 2015b). In fact, the Sarawak BN promised to regain full autonomy as one of the points in its election manifesto in 2016, an unprecedented move by East Malaysian leaders (Malaymailonline 2016). It is expected that newly appointed Sarawak Chief Minister Abang Johari Tun Openg will continue Adenan’s policies, including his call for autonomy and more state rights. In appeasing the East Malaysian elites, federal government leaders have expressed their commitment to devolve power to Sabah and Sarawak in a gradual manner (Channel NewsAsia 2015). At the moment both parties are in the process of negotiation, but there is growing frustration on the part of Sabah and Sarawak leaders over the slow pace of negotiation. Critics argue that Kuala Lumpur is engaging in delaying tactics since the federal government is perceived to be not keen on pushing for devolution of power. With the centralized federal administration system, the federal government will find it difficult to surrender its power to the state government in East Malaysia.

The strong demand for state rights in East Malaysia took an extreme slant when some people in both states openly called for secession. One of the most popular and vocal groups is Sabah Sarawak Keluar Malaysia (SSKM), led by the London-based Sabahan lawyer Doris Chan (Free Malaysia Today 2015a). Established in 2011, the group is calling for Sabah and Sarawak to cede from Malaysia and become independent states known as the Republic of North Borneo and Republic of Sarawak. In pushing for its agenda, the SSKM aims to collect 300,000 signatures, especially from Sabahans, since the group is focusing its campaign in the state. As of February 20, 2017, the group had collected 86,566 signatures. Another secessionist group that has emerged from the rising state nationalism among the people of Sabah and Sarawak is the Sarawak Sovereignty Movement (SSM) led by Morshidi Abdul Rahman. The Sarawak-based group was established just before the 2013 general election. It aimed to collect 300,000 signatures, which the group claimed to have achieved in 2016. SSM’s campaign is concentrated largely in the state of Sarawak. Najib denounced the secessionists’ demand as “stupid talk” (Star 2015b). The federal government took a heavy-handed approach against the secessionists by arresting several SSKM leaders and de-registering an NGO, Sarawak Association for People’s Aspiration, which was affiliated with the secessionist group. Subsequently, four men were charged with sedition, while the federal government issued an arrest warrant for Chan (Star 2015a). Sabah and Sarawak elites denounced the call for secession. Abang Johari vowed that Sarawak would not support secession and he would be committed to preserving the federation (Star 2018), while Musa labeled the secessionists irresponsible and rejected their demand to secede from Malaysia (Star 2014b).

Apart from challenging the supremacy of national interests over state rights, the East Malaysian elites want to change another aspect of the rules of the game: federal government control over oil and gas in the two states. When Malaysia was formed, Sabah and Sarawak had control over oil found within their territories, including offshore. But those rights were taken away when the federal government decided to take national control over the oil and gas industry by enacting the Petroleum Development Act (PDA) 1974. Under the PDA, Petroliam Nasional Bhd (Petronas) was formed. The national oil company is vested with the entire ownership of—as well as rights, privileges, and benefits in relation to exploring and producing—oil and gas, offshore and onshore, in Malaysia. With the enactment of PDA 1974, Sabah and Sarawak had to sign an agreement granting Petronas the right to extract and earn revenue from petroleum found in the two states in exchange for 5 percent of annual revenue as royalty.

Since 2014 the BN elites in Sabah and Sarawak have been pushing for a higher royalty of 20 percent. Prime Minister Najib Razak, however, made it clear just a few days before the 2016 Sarawak state election that the federal government would not review the oil and gas royalty (Daily Express 2016). This announcement irked Sarawak leaders, who later issued a moratorium on new work permits involving Petronas personnel hiring non-Sarawakians to work in the state (Borneo Post 2016b). To resolve the issue, Najib had to intervene. After several series of negotiations, the moratorium was lifted and Sarawak was given a seat on the Petronas board so as to secure the state’s interests in future decision making.

Compared to Sabah, Sarawak is in a better position to play the role of kingmaker in Malaysian politics and rewrite the rules of the game that govern federal-state relations because all BN component parties in Sarawak are based locally. The leading party within Sarawak BN is PBB, which became the second largest party within the national BN after the 2013 election. Sabah BN, on the other hand, is led by an UMNO leader who is still accountable to his political masters in Kuala Lumpur. The federal government has no other option but to accommodate the demands of the East Malaysian elites, especially from Sarawak, since they have to rely on these influential figures to remain in power. However, the federal government is in no rush to rewrite the rules of the game if the local elites do not apply some sort of pressure on them. In this respect, the elites play an important role in pushing for a review of the rules of the game in the East Malaysian states. A vocal and desperate Adenan (he publicly said that he was on borrowed time due to his health; New Straits Times 2017) was a confrontational and uncompromising leader, the kind of elite who could persuade the federal government to renegotiate the rules. The responsiveness of federal government leaders to Adenan’s demands showed how serious the government was in dealing with the local elites. But the sudden death of the popular chief minister posed questions over Sarawak elites’ capability to deal with the federal government. The new chief minister, Abang Johari, is known to be soft-spoken, accommodative, and nonconfrontational. These are not ideal traits in a leader who is expected to deal with the weakened but still undefeated federal government.

Conclusion

The federal government has dominated Sabah and Sarawak politics for more than five decades. However, throughout this period the local elites of Sabah and Sarawak have tried to resist the federal government’s intervention, thus forcing the government to accommodate them. In some cases, the federal government resorted to repressive measures in subduing local elites who were deemed to be out of control and too powerful. The co-opted elites, however, are expected to honor the rules of the game that govern federal-state relations and also the way they should run their states. Those who fail to do so will be forced to step down and eventually replaced.

The political tsunami of 2008 weakened the federal government and made it dependent on Sabah and Sarawak. The changing political landscape presented Sabah and Sarawak elites with the opportunity to rewrite the rules of the game and reclaim their autonomy. To do this, Sabah and Sarawak need vocal, bold, and uncompromising leaders to negotiate new rules that would benefit them. Sarawak had such a leader in the form of Adenan, but his sudden departure poses questions over the state’s ability to play the kingmaker role.

Regardless of whether Sabah and Sarawak can rewrite the rules of the game, political elites will continue to dominate politics in the two East Malaysian states. Consequently, the rule of the elites has undermined institutions and the rule of law in Sabah and Sarawak, leading to problems such as corruption, abuse of power, inequitable growth, land grabbing, and shrinking democratic space. To resolve these problems, the powers of the elites need to be restrained by strengthening democratic institutions and the rule of law.

Accepted: June 29, 2018

References

Black, Ian. 1985. A Gambling Style of Government: The Establishment of Chartered Company Rule in Sabah, 1878–1915. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press.

Borneo Post. 2016a. Not Quite Right to Say Sabah Is Not Doing Anything. July 27. http://www.theborneopost.com/2016/07/27/not-quite-right-to-say-sabah-doing-nothing-pbs/, accessed May 2, 2017.

―. 2016b. State Government Issues Moratorium on Work Permit of Petronas Personnel Intending to Work in Sarawak. August 7. http://www.theborneopost.com/2016/08/07/, accessed July 12, 2017.

Channel NewsAsia. 2015. More Autonomy on the Cards for Malaysian States of Sabah and Sarawak. August 11. http://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/asiapacific/more-autonomy-on-the-cards-for-malaysian-states-of-sabah-and-sar-8237948, accessed July 17, 2017.

Chin, James. 2014. Exporting the BN/UMNO Model: Politics in Sabah and Sarawak. In Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Malaysia, edited by Meredith Weiss, pp. 83–92. Hoboken: Taylor & Francis.

―. 1997. Politics of Federal Intervention in Malaysia with Reference to Sarawak, Sabah and Kelantan. Journal of Commonwealth and Comparative Politics 35(2): 96–120.

Chin Ung-Ho. 1996. Chinese Politics in Sarawak: A Study of the Sarawak United People’s Party. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press.

Cobbold Commission. 1962. Report of the Commission of Enquiry, North Borneo and Sarawak. Kuala Lumpur: Jabatan Chetak Kerajaan.

Colchester, Marcus; Jalong, Thomas; and Alaza, Leonard. 2013. Sabah: Genting Plantations and the Sungai and Dusun Peoples. In Conflict or Consent? The Oil Palm Sector at a Crossroads, edited by Marcus Colchester and Sophie Chao, pp. 269–281. Jakarta: FPP, Sawit Watch, and TUK Indonesia.

Crouch, Harold. 1996. Government and Society in Malaysia. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Daily Express. 2016. Time Not Right for Oil Royalty Talks, Says Najib. May 5. http://www.dailyexpress.com.my/109426/, accessed July 18, 2017.

Election Commission. 2017. Keputusan PRU13. Suruhanjaya Pilihan Raya Malaysia. http://resultpru13.spr.gov.my, accessed July 12, 2017.

Faisal S. Hazis. 2015. Patronage, Power and Prowess: Barisan Nasional’s Equilibrium Dominance in East Malaysia. Kajian Malaysia 33(2): 152–227.

―. 2012. Domination and Contestation: Muslim Bumiputera Politics in Sarawak. Singapore: ISEAS Press.

Fernandez, Callistus. 2001. The Legend by Sue Harris: A Critique of the Rundum Rebellion and a Counter Argument on the Rebellion. Kajian Malaysia 19(2): 61–78.

Free Malaysia Today. 2015a. Doris Jones Vows to Free Sabah and Sarawak. March 9.

http://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/nation/2015/03/09/doris-jones-vows-to-free-sabah-sarawak/, accessed March 9, 2017.

―. 2015b. Adenan Working on Ten Full Autonomy Areas. August 18. http://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/nation/2015/08/18/adenan-working-on-ten-full-autonomy-areas/, accessed July 26, 2017.

Hara, Fujio. 2002. The 1943 Kinabalu Uprising in Sabah. In Southeast Asian Minorities in the Wartime Japanese Empire, edited by Paul H. Kratoska, pp. 111–132. London: RoutledgeCurzon.

Harry, Kathleen. 2015. The Brunei Rebellion of 1962. PhD dissertation, Charles Darwin University.

Leigh, Michael. 1974. The Rising Moon: Political Change in Sarawak. Sydney: Sydney University Press.

Lim Hong Hai. 1997. Sabah and Sarawak in Malaysia: The Real Bargain or What Have They Got Themselves Into? Kajian Malaysia 15(1/2): 15–56.

Lim, Regina. 2008. Federal-State Relations in Sabah, Malaysia: The BERJAYA Administration, 1976–85. Singapore: ISEAS Press.

Loh Kok Wah, Francis. 1997. Sabah Baru and the Spell of Development Resolving Federal-State Relations in Malaysia. Kajian Malaysia 15(1/2): 63–84.

―. 1992. Modernisation, Cultural Revival and Counter-hegemony: The Kadazans of Sabah in the 1980s. In Fragmented Vision: Culture and Politics in Contemporary Malaysia, edited by Joel S. Kahn and Francis Loh Kok Wah, pp. 225–253. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Luping, Herman J. 1994. Sabah’s Dilemma: The Political History of Sabah, 1960–1994. Kuala Lumpur: Magnus Books.

Malaymailonline. 2016. Sarawak Rights Headline Team Adenan’s Polls Manifesto. April 26.

https://sg.news.yahoo.com/sarawak-rights-headline-team-adenan-polls-manifesto-033200649.html,

accessed January 3, 2017.

Means, Gordon. 1991. Malaysian Politics: The Second Generation. Singapore: Oxford University Press.

Migdal, Joel, ed. 1988. Strong Societies and Weak States. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Milne, R. S. 1963. Malaysia, Confrontation and MAPHILINDO. Parliamentary Affairs 16(4): 404–410.

Milne, R. S.; and Ratnam, K. J. 1974. Malaysia—New States in a New Nation: Political Development of Sarawak and Sabah in Malaysia. London: Frank Cass.

Mohammad Agus Yusoff. 2006. Malaysian Federalism: Conflict or Consensus. Bangi: UKM Press.

Naimah S. Talib. 1999. Administrators and Their Service: The Sarawak Administrative Service under the Brooke Rajah and British Colonial Rule. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press.

New Sabah Times. 2016. Chief Minister Says Sabah Will Adopt a Gentle Approach. August 10.

http://www.newsabahtimes.com.my/nstweb/fullstory/8559, accessed February 4, 2017.

New Straits Times. 2017. Adenan Satem, a Politician with an Incisive Intellect. January 12. https://www.nst.com.my/news/2017/01/203699/adenan-satem-politician-incisive-intellect, accessed September 9, 2017.

―. 2015. Adenan: Sarawak Government Will Not Entertain Call for Secession. July 22. https://www.nst.com.my/news/2015/09/adenan-sarawak-govt-will-not-entertain-call-secession, accessed September 8, 2017.

Ngidang, Dimbab. 2005. Deconstruction and Reconstruction of Native Customary Land Tenure in Sarawak. Southeast Asian Studies 43(1): 47–75.

Ongkili, James P. 1972. Modernization in East Malaysia, 1960–1970. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press.

Raffaele, Paul. 1986. Harris Salleh of Sabah. Hong Kong: Condor Publishing.

Reece, Bob. 1993. The Name of Brooke: The End of White Rajah Rule in Sarawak. Kuching: Sarawak Literary Society.

Ross-Larson, Bruce. 1976. The Politics of Federalism: Syed Kechik in East Malaysia. Singapore: Bruce Ross-Larson.

Sabihah Osman. 1990. The Malay-Muslim Response to Cession of Sarawak to the British Crown 1946–51. Jebat 18: 148.

―. 1983. Malay-Muslim Political Participation in Sarawak and Sabah, 1841–1951. PhD dissertation, University of Hull.

Sanib Said. 2010. Malay Politics in Sarawak 1946–1966: The Search for Unity and Political Ascendancy. Kota Samarahan: UNIMAS Press.

Singh, Ranjit. 2015. The Formation of Malaysia: Advancing the Theses of Decolonization and Competing Expansionist Nationalisms. Journal of Management Research 7(2): 209–217.

―. 2000. The Making of Sabah, 1865–1941. Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Press.

Star. 2018. Najib: Government Fully Committed to Uphold Sarawak Rights. February 10. http://m.thestar.com.my/story.aspx?hl=Najib-Govt-fully-committed-to-uphold-Sarawak-rights&sec=news&id=%7BBD55D75E-1A85-46CF-A3C4-1EFCAD6352F9%7D, accessed February 19, 2018.

―. 2017. Sabah and Sarawak Leaders: Reject Hadi’s Bill. May 8. http://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2017/05/08/sabah-and-sarawak-leaders-reject-hadis-bill/, accessed July 23, 2017.

―. 2015a. Arrest Warrant Issued for SSKM’s Doris Jones. February 10. http://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2015/02/10/sabah-doris-jones/, accessed January 8, 2017.

―. 2015b. PM Pledges to Up Funding and Cautions against Secession. August 11. http://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2015/08/11/more-power-to-sabah-and-sarawak-pm-pledges-to-up-funding-and-cautions-against-secession/#pd7MX0iKTA7tFfFI.99, accessed June 23, 2017.

―. 2014a. Unknown Sabahan Probed for Secession Call. September 4. http://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2014/09/04/doris-jones-sabah-secession-activist-under-probe/, accessed July 24, 2017.

―. 2014b. Musa Aman: Call for Sabah Secession Is Irresponsible. September 16. http://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2014/09/16/musa-sabah-secession-calls-irresponsible/, accessed July 4, 2017.

Straumann, Lukas. 2014. Money Logging: On the Trail of the Asian Timber Mafia. Basel: Bruno Manser Fund.

SUHAKAM. 2013. Report of the National Inquiry into the Land Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Kuala Lumpur: National Human Rights Commission of Malaysia.

Walker, J. H. 2002. Power and Prowess: The Origins of Brooke Kingship in Sarawak. New South Wales: Allen & Unwin; Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Wong Kim Min, James. 1995. The Birth of Malaysia. Kuching: James Wong Kim Min.