Contents>> Vol. 8, No. 1

Revitalization of Tradition through Social Media: A Case of the Vegetarian Festival in Phuket, Thailand

Jakraphan Chaopreecha*

* จักรพันธ์ เชาว์ปรีชา, College of Computing, Prince of Songkla University, Phuket Campus, 80 M.1, Vichitsongkram Road, Kathu, Phuket 83120, Thailand

e-mail: cjakraphan[at]gmail.com

DOI: 10.20495/seas.8.1_117

This paper analyzes the influence of social media in the revitalization of tradition. The case studied here is the Vegetarian Festival in Phuket, Thailand. This festival has been promoted as the largest local tourist event since the tourism industry became a dominant business in the 1990s. Through this festival, Chinese people whose ancestors migrated from Fujian have gained an opportunity to strengthen their Chinese identity, which was oppressed in the era of Thai nationalism. However, only some dominant groups have been accepted by the local government as knowledgeable enough to portray the authenticity of the Vegetarian Festival. As a result, a master narrative (Cohen 2001) explaining the history of the festival has been published by the Tourism Authority of Thailand. The narrative gives prominence to dominant shrines in Phuket, where various regulations were created to preserve the original traditions of the festival. Subsequently, younger generations who questioned the authenticity of the practices of the dominant shrines found that the festival had its origins in Taoism. Due to social media, online counterpublics emerged where counter-narratives were circulated among subordinates who were excluded from the public sphere of Phuket’s dominant shrines.

Keywords: social media, revitalization of tradition, counterpublics,Vegetarian Festival

Introduction

This paper explores the influence of social media in creating significant changes in local traditions. Although the Internet is a global phenomenon, it has distinctive effects when applied to a local setting. An analysis of its components, its social structure, and the interaction among participants is vital for understanding its role in effecting changes in the religious practices, cultural traditions, political standing, or social aspects of the society in question. In the case of the Vegetarian Festival, the main factors that drove participants to utilize social media for their negotiations were inequality in authority, variation in knowledge, and unbalanced resource access. Such a process subsequently resulted in the revitalization of tradition.

Revitalization of Tradition and Social Media

A revitalization of tradition tends to occur when the society involved undergoes events such as migration, social disputes, or political conflict. Today Internet technology, widely used since the mid-1990s, affects the way in which people located in different places communicate with one another. The Internet allows information about local culture to be circulated, homogenizing the day-to-day practices of people so that they conform to the modern market, mass consumption, and popular culture. The revitalization of tradition is possibly accelerated through the use of the Internet as well.

Revitalization refers not only to the revival of neglected traditions but also to the creation of a new meaning or function out of established traditions (Wallace 1956, 265; MacClancy and Parkin 1997, 76). Changes in the meaning of a tradition are brought about in two ways: first, when the government utilizes the tradition to impart a national identity to its citizens and the tradition becomes an invented one (Hobsbawm 1983, 4); second, when members of society make use of a new traditional function because antecedent functions are inappropriate to their modern way of life (Kurtz 2012, 228). The former is a top-down process, while the latter is a bottom-up one. This paper focuses mainly on the bottom-up process of revitalizing tradition.

The Phuket Vegetarian Festival is examined as a case in which social media plays an important role in the dynamic process of revitalization. In the top-down revitalization process, a cultural change is effected by the broadcast media, which usually transmits cultural content in a one-way fashion (Osorio 2005, 44). In the bottom-up revitalization process, social media facilitates the circulation of information about traditions among members of society in accordance with Web 2.01) technology, which supports two-way communication.

The main functions of social media—such as sharing news, posting text and photos, tagging friends, sending private messages, and responding with comments and emoticons—potentially transform stories of mundane activities into a social identity (Thurlow and Jaworski 2011, 245; Aguirre and Graham 2015, 4; Nair and Aram 2014, 469). Social identity is a basic framework used to identify characteristics of different online communities whose members aggregate in groups because of common interests, profession, gender, age, class, lifestyle, social role, or occupation (Castells 2010, 7). This online information then becomes a form of social capital that is used by social media users to access the network of a dominant group (Miller et al. 2016, 134).

Use of social media can be seen as an influencing factor on how members of society interact with one another. Sending texts via online channels becomes a “discourse”2) (Dahlberg 2013, 29) when such texts connote hidden and/or unspoken meanings that stimulate interaction among people. Through a common agreement in certain discourses, people gather in a group and then start their communal activities. This process fosters new forms of collectivity, with the result that society is multiplied in accordance with the mode of interaction among members (Postill 2011, 102). These multiple communities are initially established through social media, but afterward their activities continue in offline social settings. As a result, online and offline activities are integrated. A part of the exchange through online communication is religious discourse, a religious practice that is different from standard norms or orthodox doctrine (Mallapragada 2010). Such information can lead members of society to establish their religious communities. This paper aims to understand the process of revitalization as it is influenced by the religious practices of such communities and their communication via social media.

Social Media and Counterpublics

Ideally, the opinions of members of the public are equal in the public sphere and result in a common agreement (Habermas 1992, 12; McCarthy 1996, 67). However, this public sphere can become exclusive if a certain social group has the authority and ability to subjugate others. The former then becomes the dominant public voice, while the latter become subordinates who opt to leave the public sphere and establish their own distinct sphere of communication and interaction, called a counterpublic (Fraser 1996, 123). A counterpublic, therefore, can be referred to as an alternative sphere where subordinate voices can freely express their arguments. In the context of the revitalization of a tradition, the dominant social group strives to preserve the tradition by regulating the practices of all members of society, while the subordinates, who do not agree with such regulations, try to maintain their practices in the counterpublics.

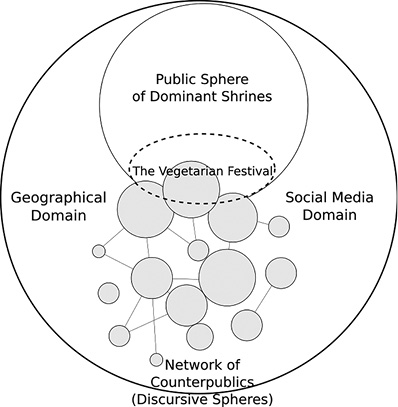

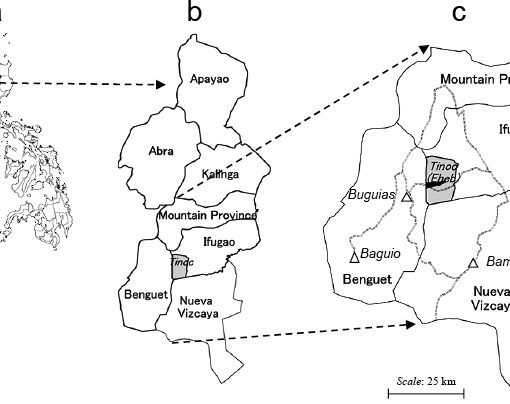

Counterpublics can be established through the use of social media, which supports subordinates who seek to exchange information and create a network among their members (see Fig. 1). Basically, the circulation of texts addressed to subordinates strengthens the process of creating counterpublics (Warner 2014, 90–91). Through the interpretation of texts, societal members who perceive themselves as sharing a collective identity are stimulated to establish counterpublic groups (Brooks 2005, 88–89), such as American black people (Whaley 2010), social movements (Palczewski 2001), feminist movements (Shaw 2012), immigrant workers (Sziarto and Leitner 2010), and indigenous groups (Johnston 2000).

Fig. 1 Theoretical Framework

Counterpublics consist of multiple groups rather than a single one, and these groups are interconnected as a network (Sheller 2004, 50). Through such networks, discourses aimed at discussing particular issues are disseminated, and the counterpublics are transformed into interconnected discursive domains (Asen 2000, 424). Therefore, counterpublics should be regarded as dynamic domains that are created, developed, associated, dissociated, and obliterated over time. By utilizing a network of counterpublics, subordinates are able to exchange resources and increase their power to negotiate with dominants (Andersson and Gun 2016, 42). This paper aims to clarify how the use of social media facilitates the process of revitalization in which there are negotiations between subordinates and dominants.

The Case of the Vegetarian Festival in Phuket

In this paper, the ninth-day ceremonies conducted by descendants of Chinese in Phuket—in an event called the Vegetarian Festival—will be discussed as a case of revitalization. The Vegetarian Festival, conducted by Chinese people whose ancestors migrated from Hokkien Province in China, aims to venerate the Nine Emperor Gods (Hokkien: Kiu Hong Tai Te 九皇大帝). The festival is a hectic event comprising four types of ceremonies—the welcome ceremony, cleansing ceremony, chanting ceremony, and sending-off ceremony (Liu 1992, 35)—that are initially conducted at the beginning of the ninth lunar month for nine days.

In these ceremonies, the main participants are the spirit mediums (Thai: mah-songs), ritual specialists (Hokkien: huatkuas), and devotees (see Fig. 2). Huatkuas conduct the ceremonies and invite the Chinese deities to possess the bodies of mah-songs. Mah-songs, while in a trance, speak in tongues in Hokkien-Chinese dialect and join the huatkuas in conducting the ceremonies by reciting prayers and blessing the devotees. A devotee who is faithful to a particular mah-song can choose to become a companion providing financial support and voluntary labor during an important ceremony. Mah-songs also play the main role in the street procession, a well-known component of the Vegetarian Festival (see Fig. 3). In this procession a myriad of mah-songs, companions, and huatkuas walk along the street from a shrine to a coastal area called Sapan-Hin to commemorate the event in which an incense urn, a symbol of the Nine Emperor Gods, was brought from China to Phuket. Along the path of the procession, devotees set up street altars and wait to worship the Chinese deities who have possessed the bodies of mah-songs.

Fig. 2 A Mah-song (in the Red Apron with Long Needles Piercing His Tongue), a Huatkua (Standing behind the Mah-song), and Devotees at the Street Procession of Naka Shrine (October 14, 2015)

Fig. 3 A Companion (Left) Wipes Blood off a Mah-song’s Wound, while Another Companion (Right) Raises a Black Flag (Orleng) to Protect a Mah-song from the Sun (October 4, 2014).

In the 1990s the Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT) promoted the Vegetarian Festival as a tourist event due to the emergence of the tourism industry in Phuket. Promoting the festival via broadcast media and publications was a challenge since TAT officials did not have much information about the festival. Thus, the officials opted to gain information from members of Kathu, a shrine believed to be the oldest in Phuket. Chaiyut Pinpradub, a local scholar from Phuket and one of Kathu Shrine’s committee members, explained:

the practice of the festival was brought from Mainland China by a group of Chinese performers who came to Phuket in 1825. There was an outbreak of epidemic disease around the tin mining area at that time, hence the Chinese performers suggested to conduct the festival in order to cease this predicament. Before the Chinese performers left Phuket, they offered Kathu Shrine the images of three deities—Ti-Hu-Nguan-Soi (钍府元帥), Lee Lochia (李哪吒), and Sam-Hu-Ong-Iah (三府王爺)—which became main deities of the Vegetarian Festival. Several years later, Kathu Shrine’s committee arranged for one person to travel to the shrine in China for the purpose of bringing back with him the incense urn, the symbol of the Nine Emperor Gods. From Mainland China, not only the urn was brought back to Phuket but also a book of prayers, which is considered as the authentic book in which the way of conducting the festival is written. (Tourism Authority of Thailand, Phuket Office 2013)

This narrative became the “master narrative” that strongly influenced the beliefs of the local people and gave Kathu Shrine prominence over other shrines (Cohen 2001). Consequently, mah-songs of the three deities whose names appeared in the master narrative received a high rank in the shrine community and came to play an important role in managing the festival. Some Phuketians even believe that only Kathu Shrine possesses the original book that is used to conduct the authentic festival. Any deviation from the master narrative is considered controversial. One such issue is the existence of female mah-songs: dominant shrine members believe that there were no female deities participating in previous festivals.

Through its promotion by the TAT, the Vegetarian Festival became a popular ceremony. However, due to this popularity, divergent opinions arose among different members of society. Many shrine members argued that certain groups of mah-songs wanted to encourage tourists to commit faith to their Chinese deities and make a donation to a shrine. They claimed that mah-songs changed the traditional festival into a spectacle by wearing colorful attire and showing their supernatural power by penetrating their bodies and faces with objects such as swords, glass, and motorcycle parts. Hence, shrine members, especially from the three main shrines3)—Kathu, Juitui, and Bangniew—embarked on a mission to preserve the conventions of the festival and regulate the practices of mah-songs. Now, mah-songs who want to participate in the festival have to register with a particular shrine and pass an exam conducted in the Hokkien-Chinese language. Elder huatkuas personally interview mah-songs while the latter are in a trance. The mah-songs become certified if they can answer the questions in the Chinese language. At Juitui Shrine, an identification card is given to registered mah-songs. In order to maintain their status as official members, mah-songs have to obey regulations such as dressing in proper attire and using only permitted traditional paraphernalia. Mah-songs who violate the rules can be banished from the shrines and may not be accepted by Phuket shrine communities.

Many mah-songs and huatkuas do not agree with the regulations of the dominant shrines and the master narrative. By being oppressed under the authoritative power of the dominants and being restricted in exercising their practices in the public sphere of dominant shrines, they become subordinates. When the Internet was introduced in Phuket, counter-narratives arguing against the authenticity of dominant shrines were circulated among various subordinates. In 2005 the website phuketvegetarianfestival.com was created, with a Web board serving as a venue for exchanging information about the festival and related Chinese culture. Members of the Web board also posted various counter-narratives such as the real origin of the festival inherited from a Taoist monastery in China, biographies of various Chinese deities whose names were not written in the master narrative, and the use of paraphernalia that did not conform to Phuket shrine regulations. Sometime between 2006 and 2008 Phuketians started to use social media, especially Facebook, which functioned as a platform for friends to communicate without reservations and restrictions. Most communities use Facebook as the main platform to connect with a wider group of people. Based on online observations from 2014 to 2016, there were 91 social media groups where more than 1,000 members circulated information about Chinese shamanic cults4) and the Vegetarian Festival. The practices of shamanic cults also expanded in Phuket, and social media became an important mechanism in the revitalization process.

The Religious Form of the Phuket Vegetarian Festival

In order to analyze the changes in the Vegetarian Festival’s meaning, the amalgamated form of the festival’s religious beliefs should be discussed. The Vegetarian Festival integrates Theravada Buddhism, Brahmanism, and the religious belief of Chinese migrant Taoism. In the practice of Taoism, people venerate the deities of nature and ancestral spirits on various festive occasions (Coughlin 2012, 106). The Chinese ceremonies inherited and conducted by Chinese descendants in Phuket are the following: Chinese New Year and the lantern festival in February, the ceremony of visiting ancestors’ graves in April, the worshipping of the spirits of the dead in July, and the veneration of the deities of the North Stars or the Vegetarian Festival in September. Because of national Thai policies, however, the practices of Taoism have lost their originality since the culture of Chinese descendants has been assimilated into Thai culture.

The political system of Thailand changed when a group of mid-level civilians and military officials seized power from King Rama VII and established the first constitution in 1932 (Charnvit 1974, 26). The concept of “Thainess” was then used to unify various groups of local people to be Thai citizens. Between 1939 and 1940, the office of the prime minister announced a series of 12 cultural mandates called ratthaniyom in line with the promotion of nationalism, which demanded the dissemination of ideas of cultural change through mass media such as radio, dramas, fictional history, and advertising. Under these mandates, Thai citizens were required to speak the Thai language and dress in Thai contemporary costume (ibid., 38). This development caused a drastic change in the way of life for ethnic Chinese inhabitants. Their children were even prevented from studying the Chinese language until they were 14 years old (Landon 1939, 92).

The national identity of Thailand is made up of three pillars: nation, religion, and kingship. Although the term “religion” is not defined, it refers to Theravada Buddhism because the Thai monarchy has maintained a relationship with the Buddhist monastery as a defender of religion since the establishment of Rattanakosin, currently known as Bangkok (Ishii 1986, 65). Based on the beliefs of Theravada Buddhism, the King is perceived among Thai citizens as both the devaraja (the King who is god) and dharmaraja (the King who has virtue) (Fong 2009, 688). This Buddhist belief is vital in supporting the authority of the King. Thus, Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat, who was the prime minister of Thailand from 1957 to 1963, promoted Buddhism (Reynolds 1977, 276) and revived Brahman ceremonies as national events (Ishii 1968, 869) where the role of the King was emphasized.

The practices of Thai Buddhist devotees written in the Buddhist treatise Traibhumikatha are based on the system of merit (Thai: bun) and sin (Thai: baab). The accumulation of merit causes a spirit to progressively regenerate on 31 different planes of existence ranging from heaven to hell (Satiankoset 1975). In order to accumulate merit, Thai people generally give alms to monks, meditate, and donate part of their income to temples. However, the activities of making merit are ambiguous since people also commit other acts that have a positive purpose, although such activities are viewed as elements of other religious beliefs. This view has led to an amalgamation of religions in Thai society under the Buddhist merit system.

Thai people explain the existence of various spirits by utilizing the Buddhist Traibhumikatha treatise, although such spirits stem from the beliefs of Taoism, Hinduism, animism, and Islam. Since there are different planes of existence in Traibhumi cosmology, spirits are believed to be reborn in a particular world according to the amount of their merit. Stanley Tambiah conducted research on the belief in the spiritual world of the people in northeast Thailand, which can be used to explain the religious beliefs of Phuket people as well. According to his research, people believe that the spirits of the dead (Thai: winjan) become malevolent spirits (Thai: phii) or guardian spirits (Thai: chao phau) depending on the merit accumulated while they were alive (Tambiah 1970, 263–264). The negative power of the phii is opposite to that of the thewada (godlike spirit), whose power is used to diagnose such malevolent spirits and to assist them in communicating with a mah-song in a shamanic ritual (ibid., 60).

Although Taoist and Buddhist philosophies both accept the existence of spirits and deities, they have some important differences. Thai Buddhists recognize that deities have the power to decide their future, but they still believe in the law of karma, which emphasizes the power of self-determination to make merit (bun). Buddhist philosophy accepts the occurrence of certain circumstances that cannot be anticipated due to outside forces but believes that people, by themselves, can predict the consequence of their action and its merit (Goodman 2002, 369; Gier and Kjellberg 2004, 284; Federman 2010, 13). In other words, people are able to decide their own future by committing good or bad deeds, which eventually produce positive or negative results. In contrast, Taoist philosophy believes that the power of people to decide their future is limited. Jean DeBernardi used the term “moral luck” (Williams 1981) to explain the Taoist belief that good behavior has limits in obtaining good results. Thus, devotees need luck, bestowed by Taoist deities, to have their fate determined in a positive way (DeBernardi 2008, 54). In order to receive luck, Chinese people have to offer money—by burning fake paper money—to Chinese deities. By doing this, they can receive not only luck but also longevity and prosperity in return.

Although the basic concepts of Taoism and Buddhism are different, the Taoist practices of the Vegetarian Festival are amalgamated with Theravada Buddhism. Taoist spiritual concepts such as possession by Chinese deities are explained by the law of karma written in Traibhumi cosmology. Phuket people believe that they will receive bun by abstaining from meat products and participating in the Vegetarian Festival. They wear white garments—white is usually regarded as a color of cleanliness in Brahmanism—rather than black, which represents power in Taoism. The knowledge of the law of karma can be used to explain why Taoist deities have to come to possess the body of mah-songs in the earthly world. As one female spirit medium said:

Chinese deities have to make merit through a human body, so the deities have to possess a human body and support people to overcome a difficulty. Then, the deities can gain enough bun to regenerate in a higher level of heaven. (Interview with Tukta, 65-year-old spirit medium, September 11, 2015)

Through the amalgamation of various religions, the religious form of the Phuket Vegetarian Festival has become blurred between Taoism and Buddhism. Because Phuket people adopt religious activities as customary shrine practices if they bestow merit upon devotees, the meritorious activities of Phuket shrines have become nonreligious activities (Kataoka 2012). Despite this amalgamation, the law of karma is still the prevailing core logic. In everyday life, Phuket people participate in Buddhist ceremonies conducted in Thai temples. They also give alms to Buddhist monks in the morning in order to receive bun. They believe that the worship of deities at Chinese shrines will accelerate the efficacy of bun and that without any amount of bun even Chinese deities cannot bestow positive fortune upon them.

This amalgamated religion influences the practices of various religious groups in Phuket. According to the Phuket shrine community, there are three religious groups: the first is a group of devotees who mainly carry out making-merit activities under Theravada Buddhism and occasionally participate in Taoist ceremonies; the second is a group who mainly worship Taoist deities and participate in Buddhist ceremonies on Buddhist holidays; the last group, smallest and scattered around Phuket, is a group of people who only practice Taoism.

The first group maintain their religious activities in both Thai temples and Chinese shrines. Their home altars are only for private worship of the images of deities and Buddha. The second and third groups are members of Phuket shrines. They are members of shrine committees, mah-songs, or huatkuas who have knowledge about Taoism and Chinese incantation. These groups worship various Chinese deities depending on their personal beliefs and the principal deities of the shrines they belong to. Exchanges among these three groups usually occur in the vicinity of shrines. Huatkuas provide a service to devotees by conducting ceremonies and communicating with Chinese deities who have possessed the bodies of mah-songs. Also, well-known mah-songs and huatkuas can be invited to conduct private Taoist ceremonies at the homes of devotees. Devotees provide financial support to mah-songs and huatkuas. Banknotes placed in sealed envelopes are given to mah-songs and huatkuas at the end of the ceremony. The amount of money is not revealed. Some devotees maintain that renowned mah-songs of Kathu Shrine earn up to 2 million baht per year (Interview with Yai, March 12, 2017).

Devotees have a close relationship with shrines near their homes. They are required to donate to these shrines, which gives them a chance to be chosen as Tao-Kae-Lor-Ju, the only person who can enter the secret area and conduct a service to the highest deities of the festival—or the Nine Emperor Gods—once a year. Phuket people believe they can receive much merit in return for doing such a service.

The authority of members of the second and third groups is not equal among the Phuket shrine community. It depends on two factors: the reputation of the shrine they are members of, and their knowledge of how to communicate with Chinese deities in the Hokkien dialect and the way they conduct the Taoist ceremonies. Members of Phuket shrines worship different deities. Some deities are widely known because their name has been written in the master narrative, and some of them are believed to possess great magical powers. Among the 49 Phuket shrines, there are only 21 at which the Nine Emperor Gods are worshipped and where a secret room for them is constructed. These shrines are registered with the Chinese Shrine Club and therefore receive financial support from the local government. They are advertised in media posts featuring the festival as a tourist event. A large amount of income can be generated for shrines that are able to participate in the Vegetarian Festival. The above-mentioned 21 shrines have become well known among devotees in Phuket. The principal deities5) of these shrines are widely worshipped, while the deities of the other 28 shrines6)—the deities of other families as well as female deities—are seemingly neglected and have become a minority. Mah-songs who are possessed by the deities of the 21 shrines have gained more popularity as well.

The younger generations, who are mostly members of the second and third groups, strive to challenge the authenticity of Phuket’s dominant shrines. Since there was a gap in Thai history when the Chinese language was not widely used, many shrine members cannot read and write Chinese characters fluently. Most Phuket huatkuas and mah-songs can only speak some of the Chinese words used in ceremonies. The younger generations, who have the opportunity to learn Mandarin Chinese in high school and study the Hokkien dialect by themselves, have attained Taoist knowledge from books brought from China, Taiwan, and Malaysia. They claim that their knowledge is more authentic than the master narrative and practices of the oldest shrine, Kathu, because they can read the historical information written in the Chinese language. Initially they tried to disseminate their knowledge in nearby shrines in the hope of being accepted by devotees and thus gaining an important position in the shrine community. However, most Phuket devotees still believe in the master narrative disseminated by the dominant shrines, due to two reasons. First, it is important that the person conducting a service to the Nine Emperor Gods during the festival be chosen by a shrine committee. Thus, the devotees need to maintain a relationship with the shrine committee. Second, the elderly members of Phuket shrines feel that pure Taoism,7) the practice that younger generations are striving to revitalize, involves the use of black magic and can therefore have a negative influence. In contrast, bun is believed to positively influence the destiny of devotees. Since younger generations want to disengage Taoism from Buddhism, they are not accepted by Phuket’s dominant shrines, where the master narrative and shrine regulations are important in preserving the religion.

Phuket shrine members want to preserve this form of amalgamated religion as their tradition. Chaiyut, a 70-year-old committee member of Kathu Shrine who wrote the master narrative, stated that a standard set of practices should be created for the Vegetarian Festival in order to show the homogeneity and identity of Phuket culture. For this reason, the difference between Taoism and Buddhism should be put aside (Interview with Chaiyut, October 28, 2015).

Thus, the younger generations have to leave the public sphere of Phuket shrines and establish counterpublics at their home altars. They conduct various Taoist ceremonies to worship deities whose names are not included in the master narrative. Hence, in the privacy of their homes they practice pure Taoism. However, interaction among devotees, huatkuas, and mah-songs is still needed.

The Emergence of Counterpublics in Social Media

Disputes among groups participating in the Vegetarian Festival have emerged since the festival was transformed. In some areas of Thailand, preserving the original Chinese practices has been a challenge. The Chinese tradition may have lost its authenticity in Krabi, where Chinese descendants are in a minority and ceremonies are conducted by a Thai spirit medium instead (Cohen 2008). In Hat Yai upholding the Chinese tradition has been difficult due to efforts to preserve the Thai national identity (Cohen 2012), since members of Chinese shrines have to conduct Taoist ceremonies in order to celebrate King Rama IX.

In contrast, Phuket is the first province where the identity of Chinese descendants has been emphasized. The Vegetarian Festival is one of the first local traditions to be promoted via broadcast media in order to exhibit its cultural value to tourists. However, the identity of Phuketians has been built under the guidance of supposedly knowledgeable members of Phuket’s three main shrines—Kathu, Juitui, and Bangniew. Consequently, the master narrative of Kathu Shrine plays an important role in asserting the originality of the festival. This supports the belief that the Phuket Vegetarian Festival is more authentic than the Vegetarian Festivals in other provinces, and thus it creates a tension between dominant shrine members and their subordinates. The subordinates utilize social media to communicate with people who question the originality of Phuket shrines’ practices. They are able to attract other members even though they are restricted from proselytizing in public, particularly in the shrines.

Thanks to social media, subordinates have the opportunity to declare pure Taoism through the dissemination of counter-narratives such as information on the real origin of the festival as a Taoist ceremony, the release of biographies of Taoist deities whose names are not mentioned in the master narrative, and the use of paraphernalia that does not conform to dominant shrines’ regulations. From 2014 to 2017, 25 social media sites disseminated information that influenced the practices of the Vegetarian Festival. A handful of social media administrators have the proficiency to write counter-narratives, while other groups of administrators have the role of redistributing them. One example of a prominent group among the subordinates is the Young Huatkua Club. Noppol, a leader of this club, wrote on his Facebook page that Taiwanese practices were more authentic than practices in Phuket (Noppol, Facebook, January 14, 2013). Noppol shared information on those practices with his group. For example, he posted a message questioning the authenticity in the way of conducting the Chia-Hoi ceremony, which aims at inviting the sacred fire of the Nine Emperor Gods (Hiao-Hoi) to the shrine. Phuket shrine officials normally conduct this ceremony in the coastal area of Sapan Hin, in order to commemorate the place where the Kathu Shrine member who voluntarily traveled to Fujian later returned to Phuket with the sacred fire. Noppol posted the following on the Facebook wall of the Young Huatkua Club as his argument:

In Taiwan, the Chia-Hoi ceremony is not conducted at the seashore. Rather, it is a ceremony in which members of a new shrine have the opportunity to visit members of old shrines and bring back the sacred fire from the old shrines. Members of the new shrine light their oil-wick lanterns at the old shrines. (Young Huatkua Club page, Facebook, April 17, 2013, translated from Thai)

This post initiated further discussion through personal messages and public posts, with Noppol receiving many messages asking about the details and origins of this ceremony. He posted an additional explanation on his Facebook page one year later in which he wrote, “I translated the information about Chai-Hoi from resources written in the Chinese language, and a story narrated by my Taiwanese friends. Please give me a comment if you have any opinion.” One reply to this post was “My ancestors were from Hokkien,” implying that Phuket people were not descendants of Taiwanese. Noppol then answered, “Taiwanese people have followed the practices of Hokkien tradition, and you cannot see the old traditions of Hokkien people in China today because of the Cultural Revolution” (Noppol, Facebook, February 6, 2014).

On some occasions, the Young Huatkua Club was criticized by people who believed in the traditional practices of Phuket’s dominant shrines. Mah-songs of Bangniew Shrine did not agree with the practices of the Young Huatkua Club and made various negative comments such as the following:

“Don’t ruin our tradition which has been inherited from our ancestors. You don’t have an authentic knowledge. Who is your teacher?”

“What was happening with Young Huatkua Club? I don’t understand.”

“They conducted the ceremony in a wrong way.”

(Young Huatkua Club page, Facebook, May 25, 2014)

The Young Huatkua Club did not delete these negative comments and continued to share information about its practices, such as the proper way to arrange the altar and use festival paraphernalia. This online group became a venue where members could ask questions, post photos of Chinese deities, ask about the deities’ biographies, and discuss how to properly venerate the deities.

The traditional way to identify deities is for elder huatkuas to interview mah-songs. However, many mah-songs choose to learn about the biographies of their deities from social media rather than ask the huatkuas of the dominant shrines. This is probably because there have been instances when huatkuas interviewed the mah-songs and judged these mah-songs as fake. Thus, these mah-songs prefer asking questions about their practices in their social media group, where they receive support from other mah-songs who are facing the same difficulty. An example of this is the case of a transgender mah-song who initiated a discussion about her possession:

Q: “I am a woman. Can I be possessed by Agong [grandfather] who has three eyes [the spirit of the male deity Iao Jian (Hokkien: 杨戬)]? He chooses me to be his mah-song.”

A: “It is impossible. The spirit of the warrior never chooses to possess a body of a female mah-song because women have a menstruation period. This spirit may be a female minion of Iao Jian who is pretending to be the deity.”

However, some mah-songs came forward to support her:

A: “Both male and female can be a mah-song of a male deity. The decision is not dependent on us, but on the deity. The deity will not come to possess the body of a mah-song if he thinks such a body is polluted by menstruation.”

A: “It is possible to be a mah-song of Iao Jian. I am also a mah-song of the male deity Lo-Chia [she wants to show that female mah-songs can be possessed by a male deity].”

(Mah-songs of Krabi, Facebook, January 17, 2016)

The authenticity of the dominant shrines has also been challenged on social media. Members of the Young Huatkua Club once conducted a meeting on the theme “What is the origin of the Phuket Vegetarian Festival?” They invited anyone interested in the topic to participate in the meeting and to register via Facebook. The meeting was conducted on August 23, 2014, and photos were posted on the Young Huatkua Club’s Facebook page. One photo showed Kathu Shrine along with information on how it was not the oldest shrine but was actually constructed in 1904 at Rommanee Street with the aim of worshipping or venerating the mother of the Big Dipper constellation or Dou-Mu-Yuan-Jun. This veneration is part of a shamanic cult inherited among the members of a secret society and was not only brought to Phuket by Chinese opera performers in 1825 as mentioned in the master narrative. This information is not only disseminated by the Young Huatkua Club but is also widely communicated among social media users.

The Facebook page เทพเจ้าจีน (Chinese deities), which has 4,282 members, also posted an argument regarding the authenticity of the practices of the dominant shrines:

If shrine officials invite the Nine Emperor Gods to the festival, they have to invite the three deities of the stars (Leng-Guan, Lam-Tao, and Pak-Tao) who have a relationship with the Nine Emperor Gods [the nine gods are also the deities of the stars]. However, the most important deities participating in the festival are not the Nine Emperor Gods. The main deity should be Dou-Mu-Yuan-Jun, who is believed to be the owner of the shrines at which the Vegetarian Festival is conducted. Thus, the practices of many shrines that invite only the Nine Emperor Gods are wrong. (Chinese Deities, Facebook, October 6, 2017)

This post questions the authenticity of the dominant shrines’ practices since these shrines’ officials never mention the name of Goddess Dou-Mu, who is considered to be the principal deity of the festival. Through discussions on social media, many people realized that the counter-narratives tended to be more authentic than the master narrative of Kathu Shrine. Many online groups then started to disseminate the origins of the festival. The narrative of Dou-Mu-Yuan-Jun was shared on many Facebook groups, such as the groups of ศาลเจ้ากวนอิมตะกั่วป่า (Kuan-Yin-Takuapa Shrine) on August 27, 2016; เจี๊ยะฉ่าย (食菜) ภูเก็ต (Eating vegetarian foods, Phuket) on August 27, 2016; ชมรมศรัทธาเทพเจ้าจีน นครศรีธรรมราช (Club of devotees who give faith to Chinese deities, Nakhonsithammarat) on March 8, 2015; and ชมรมม้าทรงศาลเจ้าส่ามฮ๋องฮู้ (Mah-songs of Sam-Hong-Hu Shrine Club) on September 29, 2016. The narrative of secret societies was also shared on many groups: สมาคมต่อต้านสิ่งงมงาย (Resistance of idolatry club) on October 16, 2015; ประวัติศาสตร์จีน (中國歷史) (Chinese history) on May 4, 2017; and กิมฮาตั๋ว (Kim-Ha altar) on October 12, 2016.

Another point of contention is the authenticity of the book that is used to conduct the Vegetarian Festival, which Kathu Shrine members declare has been kept only at Kathu Shrine. Kathu Shrine members also argue that other shrines’ officials just duplicate their practices. However, the authentic book is widely disseminated and sold today via social media. Online shops such as ร้านศิวกร 西瓦功金身 (Siwakorn shop), ชมรมมนต์จีน (Chinese-magical-prayer club), and หนังสือ ตำรา ศาลเจ้าจีน (Books, textbooks, and Chinese shrines) sell the authentic book at around THB250–750 (around USD7.70–23.10). Some huatkuas and mah-songs even share information from the authentic book for free. Magical prayers inviting Kuan-Yin and Lo-Chia to possess the body of a mah-song are also shared, in ซื้อขายพระ เทพเจ้าจีน (Images of Chinese deities trade). Members of Kathu Shrine still believe that prayers should be handed down in the traditional way, but other people have different opinions. One of them said:

It is such a pity that there is no one who can openly teach the Chinese magical prayers to younger generations who are interested in such prayers. Everyone says that the prayers should be inherited from elder huatkuas. But I argue that the practices inherited from them are still wrong because they want to keep it a secret, and they don’t want to teach all the knowledge to the younger generations. Elder huatkuas do not concentrate on teaching their students; they always think about how to profit from providing services to others. Even young huatkuas of Kathu Shrine commit wrong practices. Today, people have lost their faith in the practices of this oldest shrine because of this reason. (Phuketvegetarian.com/board/data/1076-1.html, October 25, 2012)

Based on the above discussion, it is safe to say that social media has become an open forum for posting arguments. Central to the idea of social networking is that the information is addressed to certain persons whose beliefs conform to the writer’s opinion. People can choose to either leave or join any Facebook group created by shrine members, huatkuas, mah-songs, or even merchants who just want to sell their paraphernalia online. Each group has its normative framework, mostly constructed by the narrative and practices of the dominant shrines owing to their long history, and is certified by government organizations. Participants who have practices that differ from those of the dominant shrines also have the opportunity to construct their own group and freely circulate counter-narratives like the story of the mother of the Big Dipper constellation, the origin of the festival as a practice of a secret society, and the authentic book of Chinese prayers.

When members post pictures of mah-songs and huatkuas conducting ceremonies in private places, especially at home altars, they temporarily convert the places into public spaces, and the use of various attires and paraphernalia that are not acceptable to the three main shrines can be seen in many groups. The norms that are used to justify whether those practices are right or wrong are actually dependent on the common belief of the members of the groups. In many cases, the activities of the mah-songs in the pictures are condemned as inappropriate when the pictures are posted in a group with members whose customs are mismatched. In this regard, conflicts can occur on social media within the group, which can result in the disintegration of the group and members being let go. However, an online group is easy to create through the use of social media apps such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. New pages and groups are created monthly, although sometimes their activities cease when the number of members stops growing.

Social Media and the Revitalization of the Vegetarian Festival

In the revitalization of the Phuket Vegetarian Festival, the use of social media becomes a mechanism enabling participants to meet one another not only online but also offline, in venues such as home altars and minor shrines. Through integration between these two social settings—online and offline—subordinates are able to strategize to expand their social network. The expansion increases their chances of disseminating pure Taoism, properly exchanging resources, and demonstrating their ability to conduct Chinese ceremonies. The subordinates also earn a good reputation in the counterpublic spheres when they perform their roles as huatkuas, mah-songs, or even mere companions.

This section reveals information about prominent groups of subordinates who use social media to signify their roles among the counterpublics. Two groups have been selected as representative cases based on their way of using social media. First, the Young Huatkua Club is a counter-narrative creator. Members of this group have knowledge of the Chinese language, Taoist incantation, and the history of the Chinese shamanic cult. They have initiated a circulation of counter-narratives against the narrative of the dominant shrines. Second, the group of female mah-songs acts as an intermediary or agent that distributes the counter-narratives written by groups of content creators such as the Young Huatkua Club. This group of female mah-songs potentially influences the practices of other mah-songs by reproducing such narratives in social media. Through this cycle of production and reproduction, counter-narratives become significant and eventually influence the process of revitalization.

The ethnographic data for this study was gathered through participant observations and interviews conducted periodically from 2014 to 2017.

Young Huatkua Club: The Social Network of Ritual Specialists

The Young Huatkua Club is a group of people in their 20s to 30s residing in Phuket who learned Mandarin Chinese in high school and then used the language to further study the Hokkien dialect. Knowledge, and more importantly ability, in using the Hokkien Chinese dialect is necessary in order to recite magical prayers and communicate with Chinese deities. In 2008 a group of young huatkuas was established mainly by the students of Phuket Wittayalai School. The active members of the group are Noppol, Yai, Dang, and one student from a vocational school, Eak. Noppol, the oldest in the group, was born in Phuket in 1990 and was raised by parents who are familiar with the Chinese shamanic culture and have close ties with mah-songs of various shrines. This led to Noppol’s interest in being a huatkua, a person who is esteemed as a knowledgeable person in shrine society. Noppol went to Phuket Wittayalai School in 2007 in order to study the Chinese language, and in 2010 he continued his higher education at a university in Chiang Rai, the northernmost province of Thailand. Despite the remarkable distance between Phuket and Chiang Rai, Noppol was able to continue with the activities of the Young Huatkua Club via social media.

Dang and Eak, both born in 1995, became members of Bangniew Shrine because they reside within its vicinity. They have attended the Vegetarian Festival and practice the knowledge of huatkua, which they learned from the elderly huatkua of Bangniew Shrine. While they usually support the activities of the shrine, they also regularly attend as huatkuas for the Young Huatkua Club every time a private ceremony for members is held.

Yai, the youngest member, was born in 1997 and became a student of Kathu Shrine’s huatkua, Laozi-Larn, because his parents believed in the Chinese deities. Several years later, Laozi-Larn passed away before Yai was able to sufficiently gain the knowledge required to be an official huatkua. Despite this, Yai continually read up on Chinese shamanic culture from books brought from Taiwan and Penang. Since he was not under the protection of any elderly huatkua, this led to a conflict between Yai and members of Kathu Shrine. Thus, he preferred to teach himself and then later claimed himself as a huatkua when he was 13 years old. It was much later, at the age of 17, that Yai met other young huatkuas in Phuket Wittayalai School and they established their group.

Members of the Young Huatkua Club are excluded from the dominant shrines since they do not believe in the master narrative and the practices of the dominant shrines. Because they can read the Chinese language, they find that the practices and beliefs of Phuket’s dominant shrines do not conform with those of Taiwan, where Hokkien Chinese people also migrated and imparted their traditions of shamanic practices. Yai explained the purpose of establishing the Young Huatkua Club as follows:

Our members are from various shrines, but no one is from Kathu [Shrine]. We have a common agreement to worship the Chinese deities, but not in the way of Phuket shrines because Phuket traditions have been mingled with different beliefs. We first studied the traditions of Taiwan, since the Taiwanese have a strong faith in their deities and seem to openly share their knowledge. We do not even study the practices of Penang, because their traditions are not pure either. Many of our practices are opposed to those of Phuketians; for example, I normally wear black attire8) during the song-keng [prayer recitation]. (Interview with Yai, September 21, 2015)

The network of the Young Huatkua Club’s members has expanded through the use of social media. The relationships among members was the starting point for creating online communities where their personal interests, abilities, and roles in conducting Chinese rituals could be revealed. Such abilities became the symbolic capital for members of the Young Huatkua Club in starting relationships with mah-songs or devotees who wanted to conduct Chinese rituals, as disclosed by Noppol in the following statement:

When I created the Facebook page, many people I never knew started to follow me. For example, Eak and Dang [two important members of the Young Huatkua Club] were members of Te-Kong-Tong at Bangniew, but they came to help me conduct ceremonies since we knew each other via Facebook. They finally became official members of Huat-Sue-Tong [the alias for Noppol’s house, which he wants to convert into his private shrine] when our relationship strengthened. We always exchange voluntary labor between my group and their group, Te-Kong-Tong. However, the creation of a relationship between groups like these may cause conflict if the original group is afraid of losing its members. When I went to attend ceremonies in other places, some people may have worried that I would copy their knowledge and their way of conducting ceremonies. (Interview with Noppol, February 23, 2016)

The use of social media has created an interconnection between online and offline settings. Members of the Young Huatkua Club usually support mah-songs who want to worship their deities on an important day by conducting Taoist annual celebrations of Chinese deities called Sae-Yid (生日)9) in the home altar (see Fig. 4). In order to manage the complicated activities during ceremonies, members of the Young Huatkua Club are assigned into three groups: huatkuas, musicians, and general members who take care of voluntary jobs such as folding golden papers, decorating spaces and altars, preparing food offerings, and so on. Through social media members of the Young Huatkua Club are able to reveal their roles in conducting ceremonies as well as their identities. One such instance was the annual ceremony of the deities Pun Tao Kong (土地公) and Pun Tao Ma (土地婆) in which Noppol was invited by female mah-songs of Pun Tao Ma, members of Tarue Shrine who were friends of Noppol’s parents, to conduct a three-day ceremony in a private home. Noppol set the main altar at the house entrance, where the images of the six highest deities—symbolizing the six directions of the universe according to Taoist beliefs—were located; these deities are not usually worshipped by Phuket shrine members. In the living room the altar of Pun Tao Gong, Pun Tao Ma, and other deities was prepared as the focal point of the ceremony (see Fig. 4). The house was decorated with vividly colored bouquets, poems written on paper lotuses hanging from the ceiling, and Chinese wooden lanterns. The active members of the Young Huatkua Club—Noppol, Yai, Eak, and Dang—played crucial roles in conducting the ceremonies following the Taoist ritual structure, which included a welcome ceremony, a chanting ceremony, a bridge-walking ceremony (see Fig. 5), and a sending-off ceremony (Participant observation, September 28, 2015).

Fig. 4 Noppol (Center, in the White Shirt with Writing on the Back) and Yai (in the Striped Blue Shirt) Recite Prayers at the Home Altar of Ketsinee, whose Mother is the Mah-song of Pun Tao Ma (September 28, 2015).

Fig. 5 Bridge-Crossing Ceremony Conducted by Members of the Young Huatkua Club at the Home Altar of Ketsinee. Dang (Left, Wearing a Watch) Waits for the Ceremony to Begin (September 28, 2015).

Most huatkuas of the three main shrines consider it unacceptable to conduct these ceremonies in a private home since they believe a small home cannot contain the power of high-ranking deities. However, members of the Young Huatkua Club argue that those high-ranking deities can be invited if huatkuas have sufficient knowledge and do not show disrespect to the deities.

Noppol does not follow the traditional Phuketian way of conducting ceremonies. He deliberately adds more artistically decorated altars, a food offering, and a highly complicated liturgy. After the ceremonies, many photos are usually disseminated on social media. Pictures of this three-day ceremony were later posted on the page of the Young Huatkua Club, which spread widely among various shrine members and made Noppol famous in the online world.

The connection between the online world and the ceremony conducted in the home altar is a crucial factor in supporting the exchange of necessary resources, namely, knowledge, voluntary labor, and financial support. Through the circulation of pictures of the ceremony on social media, Noppol gained the opportunity to expand his network among shrine members based on his abilities, which are necessary for conducting ceremonies. It is customary for Facebook followers to observe movements in the online world of the administrator of a page they are following, and usually add them as Facebook friends as well. Consequently, based on these social media users’ distinct practices and interests, a network that can extend beyond the online world is built among them. In the case of the Young Huatkua Club, since Noppol handled his activities both offline and online, his and his friends’ names have become well known among members of small shrines. Despite his difficulty in being accepted by the three main shrines, Noppol was able to continue his practices in a private setting.

The online and offline activities of the Young Huatkua Club have had the following sequential effects on the Phuket shrine community: (1) the Young Huatkua Club’s members provide crucial arguments and practices that question the authenticity of Phuket’s traditions; (2) through the use of social media, they open up areas for discussion among members of the shrine community; the counter-narratives become discourses that resist traditional practices supported by members of the three main shrines—Kathu, Juithui, and Bangniew; (3) the private spheres of home altars are turned into discursive spheres wherein counter-narratives are circulated. Such discursive spheres become interconnected when their members communicate with one another through online channels, visit the home altar of friends, and construct new relationships offline.

However, the activities of the Young Huatkua Club alone are not able to influence the entire process of the festival’s revitalization, which results particularly from the interaction between the private and public spheres. The roles of young huatkuas in the public sphere of the Vegetarian Festival are limited. Thus, the process of change in the festival should be mutually driven by actors who can oscillate between the private and public spheres. In the next sub-section, a group of mah-songs who utilize the counter-narratives in such fashion will be analyzed.

Information about Taoist ceremonies influences the practices of Phuket mah-songs. The counter-narratives, especially biographies of neglected deities, also assert the authenticity of mah-songs who are possessed by deities not accepted by the dominant shrines. These mah-songs then reproduce the counter-narratives through their social media in order to demonstrate the existence of their deities. Since most mah-songs are not proficient in reading Chinese characters, the counter-narratives translated by the young huatkuas are important sources of basic information.

Jiachai (食菜) Facebook Group: The Social Media of Female Mah-songs

The case in this sub-section is a group of female mah-songs who reproduced the counter- narratives and started constructing their community in their home altars. They used social media to strengthen their ties, expand their network, and earn a reputation both offline and online, which eventually increased their chances of meeting new devotees who could support them in the Vegetarian Festival street procession.

Young Huatkua Club members constantly provide information on the date of the Sae-Yid ceremony and biographies of minor deities such as Kiu-Tian-Hian-Liu (九天玄女) (Interview with Yai, March 13, 2014), Kim Hua Niew Niew (金花娘娘) (Interview with Noppol, May 23, 2016), and Tai Seng Pud Jor (大聖佛祖) (Interview with Noppol, June 9, 2017). Because of this, they are able to develop an online as well as offline relationship with mah-songs who are possessed by such deities. This research aims to understand the network of the three main actors—huatkuas, mah-songs, and devotees—unified by their use of social media. This researcher had the opportunity to interview a group of mah-songs, Jiachai, whose leader had a relationship with Yai, a core member of the Young Huatkua Club.

The leader of this group is Fon, a 36-year-old housewife with two children. Born in Pangnga, the province next to Phuket where the Vegetarian Festival culture is also practiced, she moved to Phuket in order to enroll in a tourism program at a vocational school and began working in the tourism industry after graduating in 1998. While in vocational school, she was asked by a lecturer to volunteer in Juitui Shrine, working in the kitchen and preparing the ingredients for vegetarian foods.

Since 2010 Fon has been a mah-song of Kiu-Tian-Hian-Liu (九天玄女), the female Taoist deity believed to have created mankind at the very beginning of history. However, it was observed that there were three spirits that were able to come and possess her body: (1) the elderly Kiu-Tian, who is modest and humble and has the highest rank among these spirits; (2) the young Kiu-Tian, who has a bold and strong character; and (3) the spirit of a monkey, without a specific name and the lowest ranked among the three, which often came to Fon’s body during the ceremony and played freely with devotees and their companions.

Notably, many members of the three main shrines have argued that it is impossible for mah-songs to be possessed by Kiu-Tian-Hian-Liu, whose divine power is too high to be contained by a human body. For this reason, Fon has been excluded from the dominant shrines. She has opted to communicate with some female mah-songs who believe in her practices and is careful not to start a relationship with people who seem to condemn her shamanic activities.

Fon uses Facebook as the main forum for expressing her feelings and sharing her day-to-day activities. She frequently posts selfies as well as images of her children and friends, and occasionally she posts photos of her home altar and herself as a mah-song. Fon always tags her location as “Mother’s house,” which implies the altar of Kiu-Tian (九天). Photos tagged with that location are automatically sorted by Facebook as public photos, which can be accessed by anyone. In this way, Fon has effectively changed her private home into an online public sphere. Fon also created a Facebook group named “Eating Vegetarian Foods, Phuket” or “Jiachai, Phuket” in 2012, with the initial intention of communicating with her friends in Bangkok and Phuket, and her sister in Norway. However, the group became popular—it recently had 4,511 members—which gave Fon the opportunity to circulate texts and photos to a vast audience.

Normally, dominant shrine members believe that conducting shamanic ceremonies in a private home is harmful to the homeowner if huatkuas or mah-songs do not know the right way to control supernatural powers by using Hokkien Chinese mantras. A sin of a devotee or a divine power may be left in the home’s vicinity. Fon, who does not have such knowledge, personally believes that her deity is benevolent and has only a positive influence; thus, she has decided that conducting ceremonies in her private home during special occasions, such as paying homage to her deity, is acceptable.

Every year Fon hosts friends who come to participate in the Vegetarian Festival, and so she has become the leader of her group—composed of four female mah-songs, one male mah-song, and one companion. They use social media to maintain their relationship, although they meet face to face every year. Mali, Fon’s older sister who is a mah-song of Kuan Yin and lives in Norway, comes to Phuket every year for this special occasion. During her time in Norway Mali constantly posts images of deities—especially Kuan Yin, who is her master—and the history of the Vegetarian Festival on the Jiachai Facebook group. Karn and Amonrat, who are mah-songs of Lo Chia and Yok Lue Niang Niang respectively, frequently post photos of their practice as mah-songs on Facebook despite the distance between Phuket and their residence in Bangkok (see Fig. 6). Totsawat, a male mah-song of Ang Hai Yee (红孩儿), and Pang, a friend of Fon who was the only companion supporting everyone during the street procession, have lived in Phuket. They constantly use social media to communicate with members of the group. Fon often comments on photos posted by members. Facebook Messenger or Line is used to exchange detailed information when agreements or opinions are needed.

Fig. 6 Karn Used This Photo of Himself (Right) and Amonrat (Left) when in a Trance as His Facebook Cover Photo (Facebook, October 7, 2016).

One week before the festival, Jiachai members gather at Fon’s house in order to prepare their paraphernalia, magical prints, and attire, which are used mainly during the street procession. In September 2015, in order to facilitate day-to-day communication during the festival, a Line group was created and shared among members. Worshippers who were not permanent members and only came to worship the deities of this group were also added. Since everyone had their personal activities during the day, members had to read Line-disseminated information to know the meeting place in the vicinity of the shrine. After the ceremonies each day, members shared photos via Line. The mah-songs—Fon, Mali, Karn, and Amonrat—were able to select suitable photos and post them on their Facebook group and personal walls. In this way, their social identities as spiritual mediums were publicly revealed and opened to comments.

The social identity of mah-songs is based on the characteristics of their deities. Although there are very few mah-songs of Kiu-Tian-Hian-Liu (九天玄女), the high-ranking goddess who possesses Fon, the deity is well known among devotees because of her distinctive characteristics. The mah-songs are usually dressed in yellow, which is the color of the Chinese emperor. Kiu-Tian is believed to be the female warrior deity who taught military strategy to the Yellow Emperor named Huang Di (黃帝), who is regarded as the founder of Chinese civilization. Mah-songs of Kiu-Tian may hold a sacred sword and stab themselves with needles during the street procession (see Fig. 7). The mah-songs, in a trance, torture themselves by slashing their backs or cutting their tongues with a sword. This practice is unique to mah-songs of Kiu-Tian and is not performed by female mah-songs who are possessed by other female deities. Fon posted a photo showing her in a trance, with needles penetrating her cheek while she was holding a magical sword. She captioned the photo as follows: “Mah-songs, in trance, torture themselves as a way of salvation. The mah-songs have to sacrifice their body. It is not easy to be mah-songs. Their life is always at risk.”

Fig. 7 Fon Posted This Photo of Herself in a Trance on Her Facebook Wall (Facebook, January 23, 2018).

Other social media users who understood the biography of Kiu-Tian wrote comments such as the following:

“This is a real miracle.”

“May I share this photo.”

“I have faith in this deity.”

(Facebook, Kiu-Tian-Hian-Lue, July 2, 2017)

Fon also disseminated videos and photos of the Vegetarian Festival when she was not in a trance. In an interview with Fon and Totsawat, Fon described the feedback she received from Facebook users:

Fon: “If I use Facebook Live or post videos, Taiwanese worshippers will come to see my video. For example, my recent video was shared 14 times. Taiwanese and Malaysian people love to see our ceremonies. It is a way to disseminate our culture as well.”

Researcher: “Do you have friends whom you met in your Facebook group?”

Fon: “Most of my friends in the shrine are from my group. Sometimes I cannot remember them, but they introduce themselves. Then we become friends. Those members often add the administrator of a Facebook group as a Facebook friend when they join the group.”

(Interview with Fon and Totsawat, September 26, 2016)

From this conversation, it is clear that Fon’s and her friends’ posting of pictures on their Facebook pages became their way of creating an identity in shrine society and their means of gaining popularity or earning a reputation (see Fig. 8). Fon is a mah-song of a female warrior deity, while Totsawat is a mah-song of Ang-Hai-Yee, the young deity who is widely known through the Ming novels10)) named Journey to the West. Devotees who are familiar with the biographies of deities from novels and movies can recognize the identity of mah-songs and may choose to be their companions.

Fig. 8 Fon (Left), Totsawat (Middle), and Amonrat Share Photos of Themselves when in a Trance in Order to Celebrate the Approach of the Vegetarian Festival (Facebook, October 13, 2016).

Information in social media is further channeled across the countries from Thailand to Taiwan, and a relationship is created between Fon and worshippers from various places. For example, one worshipper from Singapore, Lim Thiamsoon, asked Fon whether he could accompany her in the 2017 Vegetarian Festival (Facebook wall of Fon, October 13, 2017). Moreover, friends whom Fon met via social media have become members of the group. In 2016, Fon said:

This year we have Srida as a new member. I met her on Facebook, and she talked with me through Facebook Messenger saying that she had ong [Thai: a concealed spirit of a deity] but was not a mah-song. She wants to join the street procession and follow us in the parade. I don’t know if she can walk along with us because of her age. (Interview with Fon, September 26, 2016)

Srida, a 45-year-old female shopkeeper who was born in Pangha and moved to Phuket around 10 years ago, described her experience with Fon:

I have followed Fon’s group for a long time and saw her photos of her possession, which got me interested. Later, I found that Fon was born in Pangha as well. I then made a decision to communicate with her through Facebook Messenger. At that time Fon had already started to run her shop at Walking Street, so I went to see her there and we became acquainted. (Interview with Srida, October 3, 2016)

Srida also explained why she was interested in Fon’s deity:

I have an altar in my house, and the images of Kiu-Tian, Pud Jor, and others whose names I don’t know. My mother brought them from China, five images in total. I shared the pictures on the Jiachai group [Facebook group established by Fon]. You can see them. So I had faith in Kiu-Tian already, before I met Fon on Facebook. (Interview with Srida, October 7, 2016)

On October 7, 2016 Srida participated in the street procession as one of Fon’s companions. While Fon was in a trance, Srida had to remain nearby and follow Fon for more than four hours during a round trip from the shrine to Sapan Hin. Hence, Srida was able to communicate with other friends who came to support Fon in the ceremony, which effectively included Srida in the public sphere of the shrine community (see Fig. 9).

Fig. 9 Fon Posted Photos of Herself Participating in the Street Procession. The Last Picture (Lower Right) Shows Srida as a Companion (Facebook, October 13, 2016).

Fon created another Facebook account, which essentially became an avenue for discourse when arguments were exchanged regarding the origin and beliefs of the Vegetarian Festival. Since 2014 she has operated a Facebook account named องค์บารมี กิ่วเทียน เฮียนลื่อ (九天玄女) [Kiu-Tian-Hian-Lue], which has 1,839 friends and 345 followers. This account is used mainly to display photos, videos, and text related to her practice as a mah-song. The banner of this account is a picture of Fon in a trance, wearing yellow attire, holding a long metal sword, and standing in front of four devotees kneeling with their palms together as if in prayer to pay respects to the deity. The picture depicts the power of a female deity over humans. Fon uses this Facebook account to start relationships among female mah-songs who have a common identity based on their beliefs and practices.

It is possible for one deity to possess more than one mah-song simultaneously. On May 9, 2017 two mah-songs who were both possessed by Kiu-Tian-Hian-Lue took notice of Fon’s page, since it carried the name of their deity, and started a conversation on Fon’s Facebook wall. They exchanged their personal contact details with each other and were able to communicate with Fon via Facebook Messenger. They also exchanged information about their practices, such as the period of abstention from meat products, the color of their attire, and the posture of their deity. Mah-songs have a deity playing the role of an intermediary among them, and hence the relationship can be built upon their interactions.

Mah-songs influence the process of revitalization by entering the public sphere of the Vegetarian Festival. They can choose to either register in particular shrines or discreetly enter the area of the ceremony without permission. Fon and her friends have been able to participate in the street procession every year since 2010. She believes that her deities have the obligation to bless devotees in order to increase their charisma in return. Thus, she needs to support her deities despite her position in the shrine being lower than those of the male deities and the high cost of the necessary paraphernalia.

The street procession has become a main ritual event of the festival in which symbolic capital is exchanged and cultural practices are transformed. The process is as follows. First, the shrine needs to increase the number of devotees who commit to a donation. The street procession can build faith among devotees if the mah-songs exhibit spiritual charisma (meeting of Juitui mah-songs, September 29, 2016). Second, mah-songs become significant intermediaries between shrines and devotees due to the above reason. Phuket shrines always request mah-songs to participate in the street procession even though many of them constantly violate the shrines’ regulations. The shrines then strictly control the practices of the mah-songs and prevent some of them from engaging in the rituals. Third, through the support of a devotee, mah-songs have the opportunity to introduce various cultural customs: Taoist deities, paraphernalia, and practices that have never before appeared in the festival. Since mah-songs do not need the support of a shrine committee, they choose instead to communicate with their friends via social media. A set of symbols—names of deities, photos of paraphernalia and attire, magical prints, a list of Chinese mantras—is used in the process of communication. In the street procession, the identity of subgroups is therefore exhibited rather than a collective identity of the Phuket shrine.

From this case, it is clear that social media plays a vital role in sustaining relationships among members of the Jiachai Facebook group. Mah-songs actually need financial support from devotees and companions in order to prepare the paraphernalia and attire to be used in the street procession of the Vegetarian Festival. Compared to male mah-songs, female mah-songs are relatively unknown as important members in the ceremonies since they are prohibited from accessing the main areas where Vegetarian Festival ceremonies are conducted. In addition, they are not allowed to stand beside the palanquin or vehicle of the Nine Emperor Gods while this is brought out in the street procession by male shrine members along with male mah-songs. Thus, female mah-songs choose to use social media to emphasize and showcase their roles by sharing their photos during trance and by disseminating the biography of their deities to devotees.

Worshipping a particular deity becomes part of the identity of devotees due to their belief that “their” deity has more divine power than the others. In the case of Srida, she follows her mother in worshipping Kiu-Tian and feels that this deity has helped her family overcome many difficulties from the time she was young. Among mah-songs possessed by Kiu-Tian, the use of social media gave Fon the chance to meet Srida, who later became her supporter. There is a process of interaction in the private and public spheres by members of the group. Female mah-songs have been showcasing their activities in the private sphere of their home altars via social media for over a year, thus expanding their network, and they perform in the public sphere of the Vegetarian Festival, where they receive support from the companions whom they have met while expanding their network.

Conclusion

In the case of counterpublics, subordinates excluded from the dominant shrines are able to strengthen their ties, maintain their activities, increase their status and prestige, and secure support and resources through the use of social media. However, what is the influential role of social media in the revitalization of tradition? In order to answer this question, the revitalization of the Phuket Vegetarian Festival has been examined.

The belief in shamanic practices flourished from the 1990s, when the tourism industry was introduced in Phuket. The Vegetarian Festival has been changed by the advent of the modern economy, which has reduced the role of religious institutions. However, religious beliefs combined with economic activities have become a form of popular religion, widely practiced as a way of receiving prosperity (Pattana 2012, 31).

The emergence of a capitalist monetary system transformed the process of exchange between devotees and Phuket shrines. The TAT’s promotion of the Vegetarian Festival raised the profile of particular shrines in the public sphere, which led to donations from devotees that were used to maintain the shrines’ religious activities and renovate their buildings. The number of shrines in Phuket increased from 13 in the 1990s to 49 in 2017. Of these, 21 opted to participate in the tourist-industry-led Vegetarian Festival and consequently necessitated a greater number of mah-songs since mah-songs are intermediaries between the Chinese deities and devotees. Devotees normally make a donation to a shrine if they have the opportunity to communicate with the deities they believe in. Thus, the growth of the Vegetarian Festival as a tourist event and the increasing numbers of shrines and mah-songs reinforce each other as social trends.

The Vegetarian Festival is practiced nationwide because it is believed to be a way to make Buddhist merit (bun). In other words, Theravada Buddhism is important in supporting the festival as a part of popular religion. Thai people who practice the national religion, or Theravada Buddhism, tend to participate in the festival. Moreover, as long as the shrines accept the religious system of Buddhist merit making, the dominant shrines in Phuket gain the privilege of being central to the festival. This has created a dispute between dominant shrine members and subordinates who prefer pure Taoism.

Social media plays the important role of circulating the practices of subordinate voices. The practices of huatkuas and mah-songs have gradually changed since 2005, when the website phuketvegetarianfestival.com was established. Initially the Internet and subsequently social media became avenues for people to exchange their knowledge about shamanic cults. Forty-year-old Wichai, who established thevegetarianfestival.com, found that it became a place for exchanging counter-narratives and closed the Web board 10 years after it was set up (Interview with Wichai, August 25, 2015). After that, people started using social media apps such as Facebook, Line, and Instagram instead.

Through the use of social media, new meanings and understandings of the Vegetarian Festival were created. First, the younger generations strived to separate pure Taoism from Buddhism by promoting Taoist doctrine via social media, showing that the practices of pure Taoism disregarded the bun system of Theravada Buddhism. Second, through the dissemination of discourses about pure Taoism, the practice of the Vegetarian Festival was perceived as a way to bestow prosperity, luck, and longevity in line with Taoism rather than to accumulate merit (bun) in accordance with the doctrine of Theravada Buddhism. Lastly, the established religious practices performed during the Vegetarian Festival in Phuket were increasingly perceived by a growing minority of Thais as unorthodox.