Contents>> Vol. 8, No. 1

Regional Cooperation in Higher Education: Can It Lead ASEAN toward Harmonization?

Jamshed Khalid,* Anees Janee Ali,* Nordiana Mohd Nordin,** and Syed Fiasal Hyder Shah***

* School of Management, Universiti Sains Malaysia, 11800 Gelugor, Penang, Malaysia

Corresponding author (Khalid)’s e-mail: jamshed.jt[at]gmail.com

** Faculty of Information Management, Universiti Teknologi Mara, 40450 Shah Alam, Selangor, Malaysia

*** Faculty of Social Science, University of Sindh, Jamshoro-76080, Sindh, Pakistan

DOI: 10.20495/seas.8.1_81

The internationalization of higher education over the last two decades has transformed the education sector into a globalized, interconnected knowledge-based society. Higher education institutions and national governments have been compelled to pay more attention to academic relations and knowledge exchange opportunities with partners in other countries, particularly in the same region. The current study aims to investigate the role of higher education internationalization in Southeast Asian nations (ASEAN) for the development of a more harmonized region. Previous research has revealed that less developed countries in the ASEAN region are far behind in the race to globalization and transformation of the education industry. Therefore, it is crucial to explore the policies and strategies enacted by the ASEAN administration and determine what it lacks to achieve this goal. An exploratory comparative approach has been used to identify and investigate recent internationalization trends in ASEAN member countries. The internationalization of higher education is a compelling and logical approach to increasing harmonization at the intra-regional and interregional levels.

Keywords: harmonization, higher education institutions, internationalization practices, globalization, ASEAN region

Introduction

Internationalization of higher education is a process that recognizes the significance of global education and the establishment of a knowledge-based society1) in which the activities and practices of higher education, mobility, and collaboration can be easily facilitated and enhanced. It refers to the process of integrating international, intercultural, and global dimensions into the mission, goals, and delivery of higher education (Knight 2004). In the era of internationalization, countries around the globe are engaged in an effort to establish a systematic mechanism to address the issues of higher educational access, equity, participation, and quality (Dreher 2006; Chou and Ravinet 2017). Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) member countries aim to promote academic excellence, accessibility, quality, and international cooperation in higher education to achieve a resilient, dynamic, and sustained ASEAN community. As Vongthep Arthakaivalvatee, deputy secretary-general of the ASEAN Socio-Cultural Community, stated:

As we continue to encourage free movement of goods, services and people in ASEAN, it is imperative to assure that the quality of our higher education is at par with agreed international and regional standards; and that our education systems thrive in a culture of quality and credibility. (ASEAN 2016)

Various studies have focused on the development of harmonization and regionalization in the ASEAN region, although most of them have concentrated on economic integration, trade facilitation and immigration policies, labor standards, and supply chain connectivity (Lloyd 2005; Ayudhaya 2013; Chia 2014; Jinachai and Anantachoti 2014; Menon and Melendez 2017). However, regional integration through the internationalization of higher education is also an important element in achieving regional unification and harmonization (Altbach and Knight 2007; Knight 2012; Khalid 2018). Thus, the current study aims to explore recent trends in the internationalization of ASEAN higher education aimed at harmonization among all member nations. In addition, the study attempts a comparative analysis of the internationalization practices followed by ASEAN nations and suggests practical approaches for globalization to bring about harmony and unity in the region.

ASEAN: An Overview

ASEAN was established on August 8, 1967 by five founding members: Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand. Brunei joined in 1984, Vietnam in 1995, Laos and Myanmar in 1997, and Cambodia in 1999. The region, which has an area of around 4.5 million square kilometers, had a combined population of about 600 million in 2011 (Keling et al. 2011). As of 2017, ASEAN had 638.62 million people (US-ASEAN 2017). ASEAN is a dynamic region with great diversity among member countries in terms of geography, culture, official languages, literacy rates, population density, GDP per capita, level of socioeconomic development, information and communication technology development, education policies, systems, and structures (Moussa and Kanwara 2015).

This diversity has led to a richness of culture and resources. Despite their differences, the ASEAN countries share a common emphasis on the development of higher education for the development of the nation and region and to enter the global knowledge-based economy (Ratanawijitrasin 2015). Both the diversity and similarities impact the development of internationalization within and among higher education institutions (HEIs) in these countries and challenge educators to develop measures and collaborative strategies to assure quality higher education in the region, especially in its focused movement from regionalization toward internationalization (Armstrong and Laksana 2016).

Several research studies recognize the importance of higher education in enhancing regionalization, cultural harmonization, and integration among nations (Neubauer 2012; Knight 2013; Lo and Wang 2014; Shields 2016). Globalization of higher education has the potential to give a boost to institutions that are unable to compete with current challenges, by providing opportunities for research collaboration, attracting talent from other countries, and opening overseas branch campuses. Increasing efforts have been made to build an ASEAN knowledge community by promoting both regionalization and integration among members. The organization aims to promote harmonization among its members with the aim of building a knowledge community supported by a range of supporting organizations, for instance, the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) and the ASEAN University Network (AUN). The plans for an ASEAN Community toward the end of 2015 demanded that institutions of higher learning take action in accomplishing the goals of the ASEAN Socio-Cultural Community (ASCC), embedded in ASEAN Vision 2020, through which awareness, mutual understanding, and respect for the various cultures, languages, and religions could be nurtured. The ASCC also envisions economic integration as an ultimate goal—that is, it aims to create a single market and production base to make ASEAN countries more dynamic and competitive (ADB 2012).

Motivation for the Study

Notwithstanding the efforts made by the ASEAN leadership to achieve harmonization and regionalization by promoting the internationalization of higher education within the ASEAN community, it is still a challenging and demanding process to gain the cooperation of all members. This situation raises a number of practical questions when dealing with the promotion of internationalization at the regional level. The present study is based on the following research questions:

(1) What are the internationalization policies and plans implemented by ASEAN to bring about harmonization within the region?

(2) What are the recent trends in internationalization, and how can internationalization lead the ASEAN community toward harmonization?

To answer these important questions, the current study critically examines and analyzes a range of key ASEAN internationalization policies, recent developments within varied academic settings, and existing plans and strategies to develop a culture of integration within the ASEAN region. It also seeks to investigate the usefulness of internationalization practices as a means of enhancing harmonization among ASEAN member nations.

For the most part, the study provides an exciting opportunity to advance the understanding of harmonization within ASEAN through mutually beneficial and innovative internationalization practices. The study aims to contribute to the growing area of research on internationalization in higher education by exploring the issues and challenges faced by developing countries to compete in the global education marketplace. Several important streams within the study are identified that could prove helpful for ASEAN leaders and policy makers, as the study emphasizes the shared visions and synergized membership of ASEAN countries with the intention to strengthen the human capital of member countries rather than promoting competition.

In Southeast Asia there has long been a shared aspiration to coordinate and promote higher education within the region. The Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Organization (SEAMEO) was established in 1967 to promote regional cooperation in education, science, and culture. Promoting student, faculty, and staff mobility has also been a key priority. Enhancing student mobility was one of four key areas identified for regional higher education harmonization. However, regional disparities pose significant challenges. These include gaps in national policy and funding support; lack of infrastructure, facilities, and human resources; diversity in HEIs; and varying levels of research competency (Dang 2015; Khalid et al. 2017). Interregional student mobility is central to the post-2015 vision of ASEAN, which centers around creating a “politically cohesive, economically integrated, socially responsible and a true rules-based, people-oriented, people-centered ASEAN” (ASEAN 2015). The potential benefits are significant. As European economies slow down, many ASEAN and other Asian economies are on the rise. Thailand has become a manufacturing hub, and Korean and Japanese companies have been quick to take advantage of trade and investment opportunities within the region.

Mobile students are more likely to become mobile workers, taking advantage of economic opportunities in the region and bringing benefits to their home nations (Gribble and Tran 2016). The heterogeneity of the ASEAN community poses challenges. The member countries range from Singapore, one of the world’s most competitive economies, to Myanmar, where a quarter of the population lives below the poverty line (Yang 2014). Finance is a significant constraint. Language is another key barrier. While a growing number of institutions in the region offer programs for international students in English, the English language proficiency of students in many ASEAN member nations remains low; and boosting language tuition is considered a necessary strategy for encouraging greater mobility. There are major regional disparities, with Singaporeans undertaking most of their education in English and students in other ASEAN countries having limited exposure to English during their schooling (Yue 2013).

Student exchange plays an increasingly important role in the planning of ASEAN higher education. Following the Fourth ASEAN Summit in 1992, the AUN was developed in 1995 in order to “strengthen the existing network of co-operation among leading universities in ASEAN” by “promoting co-operation and solidarity among ASEAN scholars and academicians, developing academic and professional human resource(s), and promoting information dissemination among ASEAN academic community” (NUS 2016). Among its primary activities are student exchanges involving 30 universities in the region (AUN 2018). SEAMEO RIHED (SEAMEO Regional Centre for Higher Education and Development) and the governments of Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand have also expanded another student mobility program named M-I-T, launched in 2009, into the ASEAN International Mobility for Students (AIMS) Programme (SEAMEO RIHED 2018). The Ministry of Education of each country offers financial support to its own students for AIMS (KMUTT 2014).

The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows: The next section discusses the harmonization and internationalization of higher education. After that, a comparison of ASEAN countries on the basis of internationalization practices is presented by dividing the countries into three categories based on their number of HEIs: low, medium, and high. The paper ends with a discussion, recommendations, and suggestions for future studies.

Harmonization through Higher Education

There is no question that the internationalization of higher education has transformed the higher education landscape in the last two decades. The increasingly globalized and interconnected world in which we live has compelled HEIs, educational organizations, and national governments to pay increased attention to academic relations and opportunities with partners in other countries (Knight 2013). Harmonization is interlinked with regionalization. The regionalization of higher education was previously implemented by central governments through national policies. This process started in Sweden in 1977, failed within the decade (Premfors 1984; Clark and Neave 1992), and then was taken up by Spain with the Organic Law on Higher Education of 1983 (Neave 2003). Subsequently, regionalization emerged in Belgium, France, and the United Kingdom. The regionalization process has changed the role of nations beyond their boundaries to develop networks with neighboring countries. The past decade has seen a growing East Asian dimension to internationalization that is visible at the institutional, national, and regional levels. For instance, the number of Vietnamese students going to China and Malaysia to further their studies has been increasing (Welch 2010).

Some researchers argue that the trend of regionalization is already visible in the EU, the Caribbean, and ASEAN (Forest 1995). However, others assert that nationalism acts as a counterforce and places boundaries that cannot be crossed through regionalization (De Witt 1995). Years ago Clark Kerr, then president of perhaps the largest regional HEI in the world—the multi-campus University of California—proclaimed that there were two laws of motion active in opposite directions: the internationalization of knowledge and learning, and the nationalization of higher education (Kerr 1990). According to J. N. Hawkins (2012), there are two phases of regionalism in the Asian region, which he terms “old” and “new.” The old phase spanned three decades from 1950 to 1980 and consisted of country groupings of intra-regional interactions, peer economies, security, trade, and education. Since 1980—the new phase—neoliberalism, economic liberalism, and market deregulation have given rise to interregional organizations such as the Asia Cooperation Dialogue, Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, and ASEAN+3. Educational regionalism has been developed through organizations such as SEAMEO, the Association of Southeast Asian Institutions of Higher Learning, and RIHED (Hawkins 2012). These organizations’ core focus is on a diverse set of higher education aspects such as quality assurance, teaching and learning, collaborative research and development, and inbound/outbound student mobility (Shameel 2003; Robertson 2007).

Europe also went through several regionalization phases. In the mid-1980s to 1990s, two plans were adopted that focused on student mobility: the Socrates and Erasmus programs. They engaged not only HEIs but also Europe-wide professional associations and technical colleges, which were considered to be essential in the regionalization process. By 2000 the Comenius and Grundtvig programs had further developed the above two programs. Their focus is on various forms of harmonization such as mobility, faculty, students, policy reforms, and European university systems. In 1998 the Bologna Process began, which magnified the goal of the Magna Charta for the European Higher Education Area. The core focus of the Magna Charta was on mobility, while the Bologna Process aimed at harmonizing other aspects of European higher education.

Harmonization and Internationalization

The increase in internationalization and globalization of higher education, particularly the rapid development of cross-border higher education, has underlined an urgent need to establish robust frameworks for quality assurance and the recognition of qualifications (Altbach and Knight 2007). With the introduction of regionalism, the challenges for HEIs go beyond the concept of globalization (MacLeod 2001). The main concern is how HEIs and the national governments of regional member countries can adjust to cope with regionalized education in a manner that welcomes harmonization. The AEC faces a similar challenge to ASEAN HIEs. The education systems in ASEAN countries are diverse; therefore, students involved in intra-regional mobility face many problems in terms of cultural diversity, language and communication barriers, instructional practices, and curriculum incompatibility (Ramburuth and McCormick 2001).

Methodology

The current study is an exploratory qualitative study with a comparative approach based on an analysis of the published literature, e.g., journal articles as well as organizational and national reports. A comparative approach is especially valuable in academic research as higher education and HEIs worldwide have many common traditions and characteristics (Altbach and Peterson 1999). For a better understanding, researchers have divided the ASEAN nations into three groups based on their degree of demonstrated internationalization practices at the national and institutional levels: low, medium, and high. This division gives a clearer perspective to assist readers’ understanding of current trends influencing the internationalization of higher education in ASEAN member countries.

Findings

High Group

Only Singapore is placed in the high group for the current study. Singapore, being considered an education hub, has developed effective internationalization plans and strategies. The government of Singapore is focused on the nation’s being a global leader in the educational market (Owens and Lane 2014). It is expected that Singapore will actively contribute to the research clusters within ASEAN. Already by 2012, the director of the Science and Technology Postgraduate Education and Research Development Office in Thailand could state, “Singapore is in the premier league, while we (Thailand and Malaysia) are first division. They will have to cooperate with us in the spirit of ASEAN or they will be isolated” (Huang 2007).

Singapore’s government policies have been designed, reviewed, and implemented to promote a range of student attributes as well as values including intercultural engagement and awareness, developing a competitive edge, and creating a sense of global citizenship. All of these are accomplished through an internationally designed curriculum that works to meet the country’s industrial manpower requirements and to develop Singapore as an international education hub (Daquila 2013). Singapore’s universities, particularly the National University of Singapore, have implemented plans and activities to promote internationalization abroad as well as at home.

Medium Group

For countries in the medium group, internationalization discussions and policies are organized more around issues of student and staff mobility. The main rationales linked with internationalization activities for the governments of these countries are political and economic. These countries consider student and staff mobility as a way to further skills learning as well as trade (Lohani 2013).

Malaysia, on its way toward becoming a regional educational hub, has focused on multiple internationalization practices, particularly student mobility/exchange and research collaboration (Tham 2013). Malaysia has branches of eight foreign universities, mainly from the UK and Australia (Sengupta 2015). Similarly, Thailand has drawn noticeable interest from foreign campuses. Stamford University, originally from Singapore and Malaysia, and Webster University from the United States are two prominent international campuses in Thailand. Thailand has integrated higher education internationalization into its development plans since 1990. Internationalization was seen early on as an opportunity in Thailand for economic development; however, during the economic crisis it came to be viewed as an external threat. The government faced the dilemma of balancing these two divergent views and decided to try having it both ways (Lavankura 2013). At the institutional level, both public and private universities are attempting to develop “international teaching programs,” not only to serve the range of students’ demands but also to earn fee income.

An increasing internationalization trend can be observed in the Philippines, Indonesia, and Brunei, which are also striving to be more competent within the global education industry. In the Philippines, the need for internationalization plans has been recognized by the Commission on Higher Education to gear up HEIs, including both state and private institutions, to operate at an international level (Cinches et al. 2016). The commission’s mission includes improving institutional quality assurance and requiring HEIs to implement the necessary mechanisms to ensure that graduates are competent within a speedily changing globalized world (Laguador et al. 2014).

Indonesia views the internationalization of higher education as a challenge, and the government emphasizes the need for universities to develop internationalization strategies. Internationalization was included in the National Education Strategic Plan and the Higher Education Long Term Strategic Plan 2003–10. Various other programs were developed, including workshops/seminars on internationalization and avenues for network formation such as the Global Development Learning Network and the Indonesia Higher Education Network (Soejatminah 2009). However, a lack of capability at the institutional level has slowed down the process. Improving the basic factors shaping internationalization, for instance proficiency in English and information and communication technology, may boost the progress of internationalization in Indonesian higher education (Marginson 2010).

Low Group

Internationalization is a hallmark of ASEAN higher education at both the global and regional levels (Mok and Han 2016). For Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Vietnam, internationalization is often perceived as improving the quality of academic staff and research (Council 2013; Mathuros 2013; UNESCO 2014). As trained staff and PhD-holding professors are scarce in these countries, developing international partnerships with overseas universities is a significant way to bring knowledge from the outside to filter in for both staff and professorial ranks. Studies by the Asian Development Bank have touched on the critical issue of brain drain in these countries, where low faculty salaries fail to bring back students who have left to pursue graduate degrees abroad. Vietnam is expecting new international recognition in the global education market as five of its universities are listed in the 2019 QS Asia University Rankings. Vietnam National University, Hanoi takes the lead among the five Vietnamese universities, claiming 139th place, while Vietnam National University, Ho Chi Minh City is in the 142nd position.

In ASEAN-wide meetings, paying lip service to increase the capacity of economically weaker countries is often part of the friendly dialogue; however, there has been little effort on the part of the stronger countries to share power and to form and administer a knowledge society (Feuer and Hornidge 2015). Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Vietnam need more vigilant strategic engagement to play their role in ASEAN regionalization and harmonization.

ASEAN Efforts toward Building an ASEAN Knowledge Economy

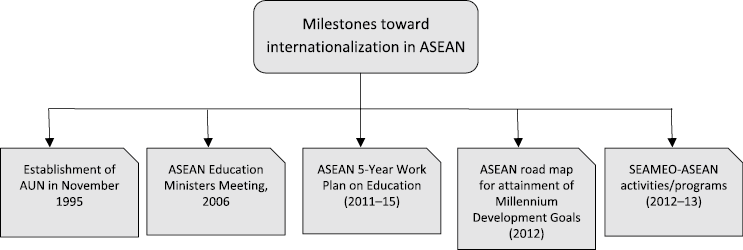

Despite their differences, the ASEAN countries agree that internationalization will allow for the better development of technology and research and enhanced regionalization and harmonization. ASEAN has implemented several plans, as shown in Fig. 1, to achieve the target of building an ASEAN knowledge community.

Internationally collaborative research will allow many countries with an inferior infrastructure to become more capable of innovating for production and growth. ASEAN continuously puts forth efforts toward developing a more harmonious and unified ASEAN knowledge economy. The efforts of the ASEAN administration toward developing higher education in the region are noticeable. However, countries already rich in technology as well as financial resources are receiving the real benefit of such strategies.

Comparison of Higher Education Internationalization in ASEAN Countries

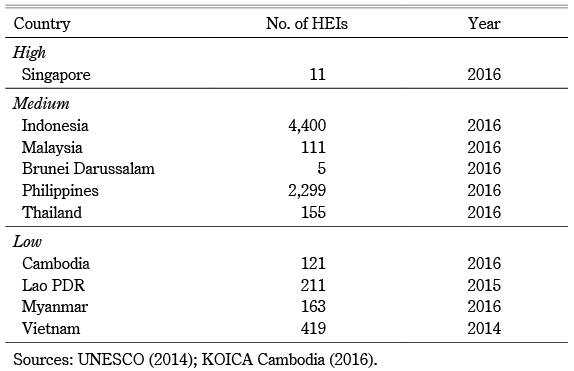

ASEAN member countries in general have high numbers of HEIs. Table 1 provides the number of HEIs in each of them.

Table 1 Number of HEIs in ASEAN Member Countries

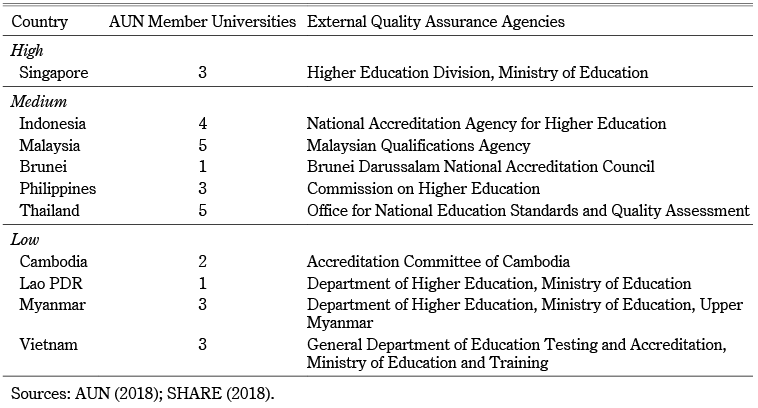

Regionalization or harmonization through mobility and collaboration of learning processes in higher education is not an end in itself. It is important that the awareness of a shared higher education area, and the linked benefits for individual universities, be communicated at all levels of the higher education system. Quality assurance is the process of promoting cooperation among HEIs and assisting with educational harmonization at the national and international levels. AUN is a platform involved in several AUN-QA programs through which joint initiatives with other organizations can be established. AUN-QA offers an assessment of universities and their educational offerings, and shares best practices relating to quality assurance. Table 2 shows the number of AUN member universities and identifies the corresponding external quality assurance agencies operating in these countries.

Table 2 Internationalization of Higher Education: A Comparative View of ASEAN Nations

Higher Education Internationalization Trends in ASEAN

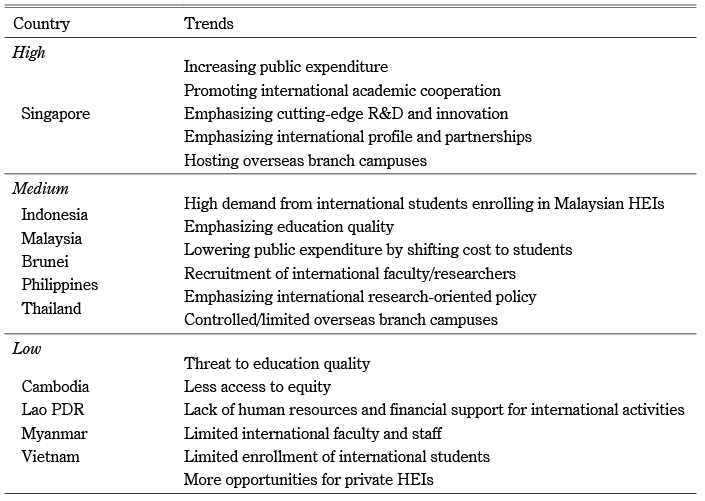

ASEAN, being a diverse region, has numerous strengths and weaknesses that vary from country to country. Based on the findings of this study, an increasing interdependence can be seen among ASEAN countries, particularly on policy collaboration and economic integration. Regionalization might be considered as an intentional process that reveals a desire to move toward a more planned rather than ad hoc form of association. Regionalization and harmonization among nations can be enhanced by encouraging internationalization of activities at the intra-regional and interregional levels. Individual ASEAN governments have increased public investment in the higher education industry to support the overall structure of ASEAN higher education and the region’s growing knowledge economy. Internationalization is viewed as a substantial stimulus to strengthen the performance of ASEAN universities across a wide range of indicators, such as exchange of students/staff, research integration and collaboration, development of branch campuses, and internationalized curricula. These measures also pave the way for enhancing integration between universities in the region, improving the overall status of Asian universities.

The findings of the present study are summarized in Table 3, which presents higher education internationalization trends in ASEAN countries.

Table 3 Higher Education Internationalization Trends in ASEAN

Discussion

ASEAN: Successes and Failures

The drive toward ASEAN harmonization seems to be on track. ASEAN member countries are motivated to move forward, and actions have been taken to support the integration of higher education. The ASEAN community acknowledges the need to create a common but not standardized or identical ASEAN Higher Education Area that can facilitate the mobility of students and faculty and comparability of degrees within Asia. However, there are political and sociocultural differences that result in variations in curricula, programs, instruction, and degrees. These can be managed in ways that allow for the creation of communal ASEAN quality control structures, degree structures, and credit transfer systems.

ASEAN’s achievements are greater in the security and political areas than in education. With increased confidence and dissipating mutual suspicion among members through cooperative activities and frequent meetings, ASEAN has enriched Southeast Asia with impressive economic growth. In order to create further harmonization through higher education, enhanced connections among ASEAN universities—via improved research and collaboration opportunities, and inbound/outbound mobility flows supported by increased prosperity—will assist in developing a mutual awareness and greater sense of regional harmony.

Undeniably, the regionalization programs and strategies implemented by ASEAN have the potential to generate considerable benefits such as knowledge sharing, intensification of cross-cultural understanding, and regional unification and peace. However, when looking at the situation as a whole, the data reveal a fragmented landscape of mutually exclusive and overlapping intraregional and cross-regional political and economic interdependencies. These uncoordinated dynamics may cause geopolitical tension, as regional networks are characterized by political maneuvering and other posturing behaviors. Thus, the execution of harmonization plans is not without its challenges. Importantly, steps are needed to increase student readiness. Language and communication barriers must be conquered. Adjustment problems occur with student mobility, particularly with respect to curriculum differences, differences in instructional practices, cultural diversity, and differences in language, the last of which in and of itself is a great barrier to cross-cultural learning. An ASEAN-wide integrated quality assurance mechanism is required; thus, the ASEAN Qualification Agency (AQA) needs to build links between the various national quality assurance systems. Confidence and mutual trust should be developed between the different systems.

Internationalization Matters: Making It Work

The internationalization of higher education has the potential to contribute to the development of a harmonized ASEAN region. The Bologna Process is a good example of this strategic mission; focusing on modernization of the international relationships of partner countries’ universities, it enhances academic mobility and correspondingly increases the attractiveness of higher education systems in European countries. In the context of ASEAN, consistency is required in internationalization and regional development policies, based on the principles of equity and enhanced academic mobility among member countries. A comprehensive international approach at the institutional, national, and multi-regional levels can boost harmonization among nations with diverse cultures, norms, and languages. Through extensive networking, partnerships, and digital transformation of HEIs (Khalid et al. 2018), ASEAN nations can come together to one higher education forum, which may lead toward unification and harmonization. Universities in ASEAN must recognize and acknowledge that “academic Institutions are always been [sic] part of the international knowledge system” (Altbach and Umakoshi 2004) and in the transformation and digitalization age they are more interconnected to global trends.

Conclusion

The current study explores contemporary trends, challenges, and opportunities in the ASEAN region toward developing a culture of harmonization among all nations and determining how the internationalization of higher education can assist in this process. The researchers found that internationalization practices—student/staff mobility, exchange programs, research collaboration, and regional scholarships—could lead to a more harmonized ASEAN community. The more developed countries—Singapore, Malaysia, Brunei, Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines—are actively developing their education systems to compete in the global knowledge society. In contrast, lesser developed countries—Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Vietnam—are not competitive globally at this point due to a lack of sufficient resources for internationalization practices, language barriers, low funding and limited regional scholarships, and ineffective national and institutional policies to implement internationalization. Therefore, these countries need to increase their collaboration and research activities within the region and mobilize the inbound/outbound flow of students by providing financial assistance. It is necessary for ASEAN leadership to engage all nations equally to build a harmonious and unified ASEAN community.

Accepted: August 16, 2018

References

Altbach, P. G. 2004. The Past and Future of Asian Universities. In Asian Universities: Historical Perspectives and Contemporary Challenges, edited by P. G. Altbach and T. Umakoshi, pp. 13–32. Baltimore and London: JHU Press.

Altbach, P. G.; and Knight, J. 2007. The Internationalization of Higher Education: Motivations and Realities. Journal of Studies in International Education 11(3–4): 290–305.

Altbach, P. G.; and Peterson, P. M. 1999. Higher Education in the 21st Century: Global Challenge and National Response. Annapolis Junction: IIE Books.

Altbach, P. G.; and Umakoshi, T. 2004. Asian Universities: Historical Perspectives and Contemporary Challengers. Baltimore and London: JHU Press.

Armstrong, N.; and Laksana, S. 2016. Internationalization of Higher Education: Case Studies of Thailand and Malaysia. Scholar 8(1): 102–116.

ASEAN. 2016. ASEAN to Boost Quality of Higher Education in the Region. ASEAN Secretariat News. https://asean.org/asean-to-boost-quality-of-higher-education-in-the-region/, accessed February 12, 2018.

―. 2015. ASEAN 2025: Forging ahead Together. ASEAN Secretariat News. https://asean.org/asean-community-vision-2025-2/, accessed January 26, 2018.

ASEAN Secretariat. 2013. ASEAN State of Education Report. Jakarta: ASEAN Secretariat. http://www.asean.org/storage/images/resources/2014/Oct/ASEAN%20State%20of%20Education%20Report%202013.pdf,

accessed January 26, 2018.

ASEAN University Network (AUN). 2018. ASEAN University Network Member Universities.

http://www.aunsec.org/aunmemberuniversities.php, accessed February 8, 2018.

Asian Development Bank (ADB). 2012. Administration and Governance of Higher Education in Asia: Patterns and Implications. Manila: Asian Development Bank.

Ayudhaya, P. D. N. 2013. ASEAN Harmonization of International Competition Law: What Is the Most Efficient Option? International Journal of Business, Economics and Law 2(3): 1–5.

Chia, S. Y. 2014. The ASEAN Economic Community: Progress, Challenges, and Prospects. In A World Trade Organization for the 21st Century: The Asian Perspective, edited by Richard Baldwin, Masahiro Kawai, and Ganeshan Wignaraja, pp. 269–315. Cheltenham and Northampton: Edward Elgar.

Chou, M. H.; and Ravinet, P. 2017. Higher Education Regionalism in Europe and Southeast Asia: Comparing Policy Ideas. Policy and Society 36(1): 143–159.

Cinches, M. F. C.; Russell, R. L. V.; Borbon, M. L. F. C.; and Chavez, J. C. 2016. Internationalization of Higher Education Institutions: The Case of Four HEIs in the Philippines. Liceo Journal of Higher Education Research 12(1): 17–36.

Clark, B. R.; and Neave, G. R., eds. 1992. The Encyclopedia of Higher Education, Vol. 2. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Council, B. 2013. Empowering Higher Education: A Vision for Myanmar’s Universities. http://www.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/report_empowering_higher_education_dialogue.pdf,

accessed January 26, 2018.

Dang, Q. A. 2015. The Bologna Process Goes East? From “Third Countries” to Prioritizing Inter-regional Cooperation between the ASEAN and EU. In The European Higher Education Area, edited by Adrian Curaj, Liviu Matei, Remus Pricopie, Jamil Salmi, and Peter Scott, pp. 763–783. Cham: Springer.

Daquila, T. C. 2013. Internationalizing Higher Education in Singapore: Government Policies and the NUS Experience. Journal of Studies in International Education 17(5): 629–647.

De Witt, H. 1995. Education and Globalization in Europe: An Overview of Its Development. Paper presented at CIES Conference, Boston, March 29–April 2, 1995.

Dreher, A. 2006. Does Globalization Affect Growth? Evidence from a New Index of Globalization. Applied Economics 38(10): 1091–1110.

European Union Support to Higher Education in the Asean Region (SHARE). 2018. ASEAN Quality Assurance Network (AQAN). https://www.share-asean.eu/sites/default/files/AQAF.pdf, accessed February 14, 2018.

Feuer, H. N.; and Hornidge, A. K. 2015. Higher Education Cooperation in ASEAN: Building towards Integration or Manufacturing Consent? Comparative Education 51(3): 327–352.

Forest, J. F. 1995. Regionalism in Higher Education: An International Look at National and Institutional Interdependence. Boston College Center for International Education. Boston: BCIHE. http://www.higher-ed.org/resources/JF/regionalism.pdf, accessed January 18, 2018.

Gribble, C.; and Tran, L. 2016. International Trends in Learning Abroad: Information and Promotions Campaign for Student Mobility. Melbourne: International Education Association of Australia. Australian Government Department of Education and Training (May).

Hawkins, J. N. 2012. Regionalization and Harmonization of Higher Education in Asia: Easier Said than Done. Asian Education and Development Studies 1(1): 96–108.

Huang, F. 2007. Internationalization of Higher Education in the Developing and Emerging Countries: A Focus on Transnational Higher Education in Asia. Journal of Studies in International Education 11(3–4): 421–432.

Jinachai, N.; and Anantachoti, P. 2014. ASEAN Harmonization: Compliance of Cosmetics Regulatory Scheme in Thailand within 5 Years. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science 19(3): 46–54.

Keling, M. F.; Som, H. M.; Saludin, M. N.; Shuib, M. S.; and Ajis, M. N. E. 2011. The Development of ASEAN from Historical Approach. Asian Social Science 7(7): 169–189.

Kerr, C. 1990. The Internationalization of Learning and the Nationalization of the Purposes of Higher Education: Two Laws of Motion in Conflict. European Journal of Education 25(1): 5–22.

Khalid, J. 2018. Diversity’s Promise for Higher Education: Making It Work. Asian Education and Development Studies 7(1): 118–120.

Khalid, J.; Ali, A. J.; Khaleel, M.; and Islam, M. S. 2017. Towards Global Knowledge Society: A SWOT Analysis of Higher Education of Pakistan in Context of Internationalization. Journal of Business 2(2): 8–15.

Khalid, J.; Ram, B. R.; Soliman, M.; Ali, A. J.; Khaleel, M.; and Islam, M. S. 2018. Promising Digital University: A Pivotal Need for Higher Education Transformation. International Journal of Management in Education 12(3): 264–275.

King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi (KMUTT). 2014. The ASEAN International Mobility for Students Programme. King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi. http://global.kmutt.ac.th/the-asean-international-mobility-for-students-programme, accessed January 22, 2018.

Knight, J. 2013. Towards African Higher Education Regionalization and Harmonization: Functional, Organizational and Political Approaches. International Perspectives on Education and Society 21: 347–373.

―. 2012. A Conceptual Framework for the Regionalization of Higher Education: Application to Asia. In Higher Education Regionalization in Asia Pacific, edited by John N. Hawkins, Ka Ho Mok, and Deane E. Neubauer, pp. 17–35. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

―. 2004. Internationalization Remodeled: Definition, Approaches, and Rationales. Journal of Studies in International Education 8(1): 5–31.

Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA) Cambodia. 2016. Overview of Education in Cambodia: Education System and Challenges. http://www.koicacambodia.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/2-Overview-of-Education-in-Cambodia.pdf, accessed January 28, 2018.

Laguador, J. M.; Villas, C. D.; and Delgado, R. M. 2014. The Journey of Lyceum of the Philippines University-Batangas towards Quality Assurance and Internationalization of Education. Asian Journal of Educational Research 2(2): 45–49.

Lavankura, P. 2013. Internationalizing Higher Education in Thailand: Government and University Responses. Journal of Studies in International Education 17(5): 663–676.

Lloyd, P. J. 2005. What Is a Single Market? An Application to the Case of ASEAN. ASEAN Economic Bulletin 22(3): 251–265.

Lo, W. Y. W.; and Wang, L. 2014. Globalization and Regionalization of Higher Education in Three Chinese Societies: Competition and Collaboration: Guest Editors’ Introduction. Chinese Education & Society 47(1): 3–6.

Lohani, B. N. 2013. Building Knowledge Economies in Asean Requires Education, Innovation. Asian Development Bank. http://www.adb.org/news/op-ed/building-knowledge-economies-aseanrequires-education-innovation-bindu-n-lohani, accessed February 2, 2018.

MacLeod, G. 2001. New Regionalism Reconsidered: Globalization and the Remaking of Political Economic Space. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 25(4): 804–829.

Marginson, S. 2010. Higher Education in the Global Knowledge Economy. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 2(5): 6962–6980.

Mathuros, F. 2013. Myanmar to Focus on Education and Skills Training for Its Young Workforce. World Economic Forum. http://www.weforum.org/news/myanmar-focus-education-and-skills-trainingits-young-workforce, accessed January 20, 2018.

Menon, J.; and Melendez, A. C. 2017. Realizing an Asean Economic Community: Progress and Remaining Challenge. Singapore Economic Review 62(3): 681–702.

Mok, K. H.; and Han, X. 2016. The Rise of Transnational Higher Education and Changing Educational Governance in China. International Journal of Comparative Education and Development 18(1): 19–39.

Moussa, M.; and Kanwara, S. 2015. Trends in International Education in a Higher Education Institution in Northern Thailand: A Descriptive Case Study. ASEAN Journal of Management & Innovation 2(1): 41–59.

National University of Singapore (NUS). 2016. International Programmes at the National University of Singapore. International Relations Office, NUS. http://www.nus.edu.sg/iro/doc/prog/sep/sep_step_in.pdf, accessed January 18, 2018.

Neave, G. 2003. The Bologna Declaration: Some of the Historic Dilemmas Posed by the Reconstruction of the Community in Europe’s Systems of Higher Education. Educational Policy 17(1): 141–164.

Neubauer, D. E. 2012. Introduction: Some Dynamics of Regionalization in Asia-Pacific Higher Education. In Higher Education Regionalization in Asia Pacific, edited by John N. Hawkins, Ka Ho Mok, and Deane E. Neubauer, pp. 3–16. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Nguyen, T. T.; Nguyen, T. A.; and Giang, H. T. 2014. Trade Facilitation in ASEAN Members: A Focus on Logistics Policies toward ASEAN Economic Community. Working paper 2014 (01), SECO/WTI Academic Cooperation Project.

Owens, T. L.; and Lane, J. E. 2014. Cross-Border Higher Education: Global and Local Tensions within Competition and Economic Development. New Directions for Higher Education 2014(168): 69–82.

Premfors, R. 1984. Analysis in Politics: The Regionalization of Swedish Higher Education. Comparative Education Review 28(1): 85–104.

Ramburuth, P.; and McCormick, J. 2001. Learning Diversity in Higher Education: A Comparative Study of Asian International and Australian Students. Higher Education 42(3): 333–350.

Ratanawijitrasin, S. 2015. The Evolving Landscape of South-East Asian Higher Education and the Challenges of Governance. In The European Higher Education Area, edited by Adrian Curaj, Liviu Matei, Remus Pricopie, Jamil Salmi, and Peter Scott, pp. 221–238. Cham: Springer.

Robertson, S. L. 2007. Regionalism, “Europe/Asia” and Higher Education. Centre for Globalisation, Education and Societies, University of Bristol. https://susanleerobertson.com/publications/, accessed February 2, 2018.

Sengupta, E. 2015. Malaysian Higher Education. In Democratizing Higher Education: International Comparative Perspectives, edited by Patrick Blessinger and John P. Anchan, pp. 184–198. New York: Taylor & Francis.

Shameel, A. 2003. The New Asian Realism: Economics and Politics of the Asia Cooperation Dialogue. Institute of Strategic Studies, Islamabad. http://www.eldis.org/document/A17305, accessed January 18, 2018.

Shields, R. 2016. Reconsidering Regionalisation in Global Higher Education: Student Mobility Spaces of the European Higher Education Area. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 46(1): 5–23.

Soejatminah, S. 2009. Internationalisation of Indonesian Higher Education: A Study from the Periphery. Asian Social Science 5(9): 70–78.

Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Organization, Regional Centre for Higher Education and Development (SEAMEO RIHED). 2018. SEAMEO Regional Centre for Higher Education and Development. Student Mobility (AIMS). https://rihed.seameo.org/programmes/aims/, accessed February 14, 2018.

Tham, S. Y. 2013. Internationalizing Higher Education in Malaysia: Government Policies and University’s Response. Journal of Studies in International Education 17(5): 648–662.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). 2014. Transferable Skills in Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET): Policy Implications. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization and UNESCO Bangkok. http://www.unescobkk.org/fileadmin/user_upload/epr/TVET/AP8_Transferable_Skills_22_Aug.pdf, accessed January 28, 2018.

US-ASEAN. 2017. What Is ASEAN. US-ASEAN Business Council. https://www.usasean.org/why-asean/what-is-asean, accessed October 12, 2018.

Welch, A. R. 2010. Internationalisation of Vietnamese Higher Education: Retrospect and Prospect. In Reforming Higher Education in Vietnam, edited by Grant Harman, Martin Hayden, and Thanh Nghi Pham, pp. 197–213. Dordrecht: Springer.

Yang, H. 2014. The Achievability of an “ASEAN Community” through Regional Integration—In Comparison with the European Union. Hong Kong Baptist University Library.

https://library.hkbu.edu.hk/award/images/2014_Awardhonourable_YangHanmo.pdf, accessed February 22, 2018.

Yue, C. S. 2013. Free Flow of Skilled Labour in ASEAN. In ASEAN Economic Community Scorecard: Performance and Perception, edited by Sanchita Basu Das, pp. 107–135. Singapore: ISEAS Publishing.

1) “Knowledge-based society” refers to a society that is well educated and therefore relies on the knowledge of its citizens to drive innovation, entrepreneurship, and dynamism.