Contents>> Vol. 9, No. 3

Revisiting Transnational Media Flow in Nusantara: Cross-border Content Broadcasting in Indonesia and Malaysia

Nuurrianti Jalli* and Yearry Panji Setianto**

*Department of Languages, Literature, and Communication Studies, Northern State University, 1200 S Jay St, Aberdeen, South Dakota, 57401, The United States of America

Corresponding author’s e-mail: nuurrianti.jalli[at]gmail.com

**Departemen Ilmu Komunikasi, Universitas Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa, Jl. Raya Jakarta Km 4 Pakupatan Kota Serang Provinsi Banten, Indonesia

DOI: 10.20495/seas.9.3_413

Previous studies on transnational media have emphasized transnational media organizations and tended to ignore the role of cross-border content, especially in a non-Western context. This study aims to fill theoretical gaps within this scholarship by providing an analysis of the Southeast Asian media sphere, focusing on Indonesia and Malaysia in a historical context—transnational media flow before 2010. The two neighboring nations of Indonesia and Malaysia have many things in common, from culture to language and religion. This study not only explores similarities in the reception and appropriation of transnational content in both countries but also investigates why, to some extent, each had a different attitude toward content produced by the other. It also looks at how governments in these two nations control the flow of transnational media content. Focusing on broadcast media, the study finds that cross-border media flow between Indonesia and Malaysia was made possible primarily in two ways: (1) illicit or unintended media exchange, and (2) legal and intended media exchange. Illicit media exchange was enabled through the use of satellite dishes and antennae near state borders, as well as piracy. Legal and intended media exchange was enabled through state collaboration and the purchase of media rights; both governments also utilized several bodies of laws to assist in controlling transnational media content. Based on our analysis, there is a path of transnational media exchange between these two countries. We also found Malaysians to be more accepting of Indonesian content than vice versa.

Keywords: Nusantara, Indonesia, Malaysia, transnational media, cross-border content, broadcast media

Introduction

The effect of globalization on national media systems has encouraged various countries to reconsider the effectiveness of their media policy. While the presence of foreign media content is not new for most nations, the intrusion of material produced by other countries has long been considered a national threat (Crofts Wiley 2004; Cohen 2008). This is more so in states that aim to protect their national identities from the infiltration of foreign cultures, which are viewed as unsuitable for local audiences, via imported media content. Today, with the proliferation of the Internet, Indonesia and Malaysia are expressing concerns over the media flow from foreign countries through global channels such as Netflix, Hulu, Amazon Prime, and Viu, among others. Leaders in Malaysia and Indonesia have raised concerns over the potential impact of loosely regulated media content on local cultural and religious values, especially content related to LGBTQA+, violence, and leftist political ideologies (Anton Hermansyah 2016; Kelion 2016; Katrina 2019).

Notwithstanding the current reality, where global media companies like Netflix have already infiltrated Malaysia and Indonesia through the Internet, this paper aims to provide a historical overview of transnational content in both countries before 2010. Since previous studies on transnational media have emphasized transnational media organizations and tended to ignore the role of cross-border content (Esser and Strömbäck 2012), this paper hopes to fill this theoretical gap by providing data focusing on these two nations. More data on this topic will help to cross-examine the significance of country and regional studies from the perspective of global communication and media studies (Flew and Waisbord 2015). Additionally, this research hopes to assist in providing insights into prognosticating reactions from both governments to trends in global media consumption, based on policies implemented by both countries in the past decade.

The relationship between Indonesia and Malaysia has always been defined based on the idea of serumpun (kinship), the sharing of racial and religious affinity (Islam), linguistic similarity, geographical proximity in the Malay Archipelago (or Nusantara), and a shared history (Khalid and Yacob 2012). Yet the two countries have adopted restrictive media policies toward transnational/foreign media content from each other—along with other countries in the region. Cross-border flow of media content eventually became a political debate in Indonesia and Malaysia (Mohamad Rizal 2010), but what influenced the laws and regulations put in place to deal with this issue remains unanswered. Thus, we argue that comparing the media regulations between Indonesia and Malaysia would further explain what factors determined their decisions in media policy-making processes, especially their critical stance toward Western media content. We also look at the media exchange between Indonesia and Malaysia and investigate the channels of transnational media in these two states in the decades up to 2010. Finally, this study also explores factors influencing the acceptance of cross-border media content in both countries.

For this study we used a historical method, focusing on the comparison of media policies in Indonesia and Malaysia and how these countries developed their strategy on the flow of transnational media content. Among the secondary data we used were past publications, government reports, as well as online databases. This paper aims to answer three research questions: (1) How was the practice of transnational media content flow in Indonesia and Malaysia before 2010? (2) How did the governments of Indonesia and Malaysia control transnational media content? (3) What factors influenced the acceptance of transnational media content in both countries? The discussion is focused on broadcast media before 2010. It is essential to also understand that, despite the objectives, this paper does not aim to measure the acceptance level of media content in Malaysia and Indonesia. We aim to provide insights on matters related to the practice of transnational media flow and government approaches to cross-border content, and to explore potential factors influencing the acceptance of transnational media content in both countries.

Globalization and Transnational Media

With globalization, societies are becoming more transnational. Globalization also creates problems that cannot be handled at the level of nation-states, and this forces governments to think at the supranational level (Kearney 1995). Globalization can be illustrated by the increasing cross-border activities, from interactions among people from different parts of the world through social media platforms to people in different locations enjoying similar content provided by global media-services providers like Netflix. While these transnational phenomena cannot be simplified as logical consequences of the increasing popularity of global media widely accessed by global audiences, it is somewhat difficult to diminish the impact of media on the advancement of globalization. As a result, the transnational flow of media content can also be seen as one of the effects of globalization.

Edward Herman and Robert McChesney (2004) explained that significant changes are taking place within society and in our relationship with media due to the influence of global media. These changes include increasing cross-border flows of media content as well as a growing number of transnational media organizations. However, the authors also warned of the negative consequences of global media, mainly an increase in commercialization and centralized control over media. On the one hand, thanks to the globalization of media, many people in underdeveloped countries can easily watch high-quality programs produced by television stations in developed nations. On the other hand, the infiltration of transnational media content, mostly from Western countries, is seen as a threat to national cultures. Even the dominance of news content from the Western world through global media into Third World countries like Malaysia and Indonesia has often been perceived as an attack on the free flow of information (McBride 1980). Additionally, within the perspective of cultural imperialism, the international flow of communication is seen as favoring industrialized nations and threatening sociocultural values of developing countries (McBride 1980; Kraidy 2002). In some states, foreign television programs have been accused of promoting consumerism (Paek and Pan 2004). Even though policy makers in different countries have varying attitudes toward the presence of global media, governments in many developing nations tend to exhibit hostility toward unwanted transnational media content.

One of the most interesting debates concerning the threat of global media and transnational flows of communication took place during the UNESCO meeting in Kenya in 1973. During the initiation of the New World Information and Communication Order, a debate session hosted at the UNESCO meeting, some countries argued over whether the advancement of transnational media flows would be positive. According to Marwan Kraidy (2002), Western countries, which had more advanced media industries, argued that the free flow of information should be seen as positive, while the other nations did not agree and were afraid that liberalization of the flow of information would benefit only Western countries (McBride 1980). Even today it is argued that there is an imbalance in the transnational flow of information, especially since media content tends to flow from developed nations to developing ones.

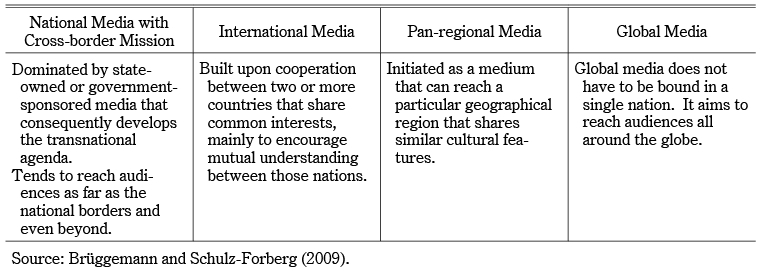

There have been several attempts to define the term “transnational media.” For example, Leo Gher and Kiran Bharthapudi (2004) defined it as “communication, information or entertainment that crosses international borders without the regulatory constraints normally associated with electronic media.” Other scholars have explained the different types of transnational media. Michael Brüggemann and Hagen Schulz-Forberg (2009) categorized it into four types: (1) national media that has a cross-border mission, (2) international media, (3) pan-regional media, and (4) global media as illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1 Types of Transnational Media

Diplomatic Relationship between Indonesia and Malaysia

The diplomatic relationship between Malaysia and Indonesia has existed for several decades, since the time of Malaya’s independence in 1957 (Muhammad 1964; Malaysia, Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2015). However, this relationship has not always been stable and is bittersweet. When Malaysia was formed (through the amalgamation of the Federation of Malaya, Singapore, Sabah, and Sarawak) in 1963, Indonesia, led by President Sukarno, was not happy with the idea. The Indonesian government’s opposition to the formation of Malaysia led to a violent conflict, better known as Konfrontasi, that lasted three years—1963–66. According to James Mackie (1974), this diplomatic dispute was an undeclared war, with most of the action occurring at the border between Indonesia and East Malaysia in Borneo; it included restrained and isolated combats and was most likely driven by Sukarno’s political purposes. However, Konfrontasi ended with Indonesia finally acknowledging the formation of Malaysia.

In more recent times, tensions between these two countries expanded to issues of territorial boundaries, Indonesian illegal immigrants, ill treatment of Indonesian workers in Malaysia, human trafficking, and the infamous annual forest fires in Indonesia that resulted in a terrible haze over Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore for more than a decade from the mid-1990s (Kanapathy 2006; Kompas 2007 in Heryanto 2008; Killias 2010; Elias 2013). There were also several disputes between these countries over ownership of items of cultural heritage, such as the Pendet dance, folk songs like “Rasa Sayang” and “Terang Bulan,” and wayang kulit shadow puppetry (Chong 2012). However, despite the endless conflicts between these two countries, governments on both sides worked hard to arrive at a better understanding and a more stable diplomatic relationship. This could be seen through the efforts by both governments to strengthen bilateral ties. In 2018, during a diplomatic visit to Indonesia by Malaysian Prime Minister Dr. Mahathir Mohamad, he and Indonesian President Joko Widodo pledged to improve the relationship between their countries and focus on resolving outstanding border issues, enhancing protection and welfare for migrant workers, and potentially reviving the old plan of an ASEAN car project (Chan 2018).

Media in Indonesia and Malaysia

As in many Southeast Asian countries, the broadcasting system in Indonesia was introduced during the colonial period. Under Dutch colonial rule, radio was used to relay messages from the Netherlands to the Dutch East Indies as well as provide entertainment for colonial elites (Kitley 2014). When Japan took over, radio became a propaganda tool for the colonizers, with Japanese programs delivered to local audiences. When Indonesia gained its independence in 1945, radio eventually became the primary tool to broadcast nationalistic and revolutionary messages around the country. Once the national radio system became more established, the Indonesian government set up a national television network, Televisi Republik Indonesia (TVRI), in August 1962 through the Decree of the Minister of Information No. 20/1961. The initial reason for this was that Sukarno, the Indonesian president at the time, wanted to deliver the image of Indonesia as a modern country to the whole region (Kitley 2003). As the host of the Asian Games in 1962, Indonesia wanted to broadcast this sporting event to other Asian countries transnationally. However, after the Asian Games TVRI suffered a lack of funding, which resulted in the discontinuation of the network (Kitley 2014). Consequently, TVRI was overwhelmed by American television programs: it was much cheaper to broadcast those than to produce local programs.

Indonesia’s second president, Suharto, who overthrew Sukarno in 1965, enjoyed his control over the country’s broadcasting system. He exercised powerful control over the media in general, mainly through “licensing mechanism, media ownership regulation, paper distribution, media associations, Press Council membership and so on” (Agus Sudibyo and Patria 2013, 258). He prohibited broadcast media from delivering political messages, which in turn encouraged the growing popularity of entertainment content. Music, both local and Western, dominated radio shows at that time. While Suharto still allowed national television to broadcast limited transnational programs, such as American TV shows, he prohibited TVRI from airing advertisements over concerns that television commercials might promote consumerism (Ade Armando 2011). The Indonesian government tended to be permissive with imported programs due to business reasons. However, on some occasions government officials still warned the public not to be influenced by Western cultures that were promoted through foreign television programs.

Indonesia’s first private television network, Rajawali Citra Televisi Indonesia (RCTI), was introduced in the late 1980s. One of the reasons why Suharto permitted a private television network was to distract Indonesian viewers from foreign broadcasting (Ade Armando 2011). It seems that the increasing use of satellite dishes at that time encouraged local audiences to access international broadcasts illegally. Through shared signals from a satellite dish, even people in a small village could watch overseas television programs that were not available on local broadcasting channels. Unable to prohibit the use of satellite dishes, the government issued an “open skies” policy and legalized the use of parabola satellites, but many people still used them to access foreign channels (Sen and Hill 2006). Therefore, rather than further control the use of satellite dishes, which was seen as impractical, the government tried to attract local audiences by introducing private television channels.

The strict Suharto government finally fell after the countrywide Reformasi protest movement in 1998. In the aftermath of Suharto’s defeat there was media liberalization, which allowed the growth of press freedom and creativity (Kakiailatu 2007). Films that were deemed as sensitive or critical of the government were publicly broadcast, and various new creative products could be shared with international audiences. However, some critics argued that although there were improvements in terms of cultural expression, some media content was still heavily censored (Sen and Hill 2006), such as pornography, extreme violence, and content deemed too critical of the Indonesian government or its policies.

In Malaysia, too, the media was tightly controlled by the ruling power. The government or its affiliated companies owned broadcasting stations, especially during the Barisan Nasional (BN) government and its predecessor Parti Perikatan government from the country’s independence in 1957 until 2018. This resulted in minimal media freedom in the country and not much variety in media content available to the public (Kim 2001; McDaniel 2002; Mohd Sani 2004; George 2006; Iga 2012; Willnat et al. 2013). It also led to media monopoly. In addition to free-to-air (public) channels such as RTM1, RTM2 (operated by the Ministry of Communications and Multimedia), TV3, NTV7, 8TV, and TV9 (operated by the government-affiliated Media Prima Berhad), the other media giant in the country was—and is—the sole satellite television service provider, Astro, owned by Astro Malaysia Holdings Berhad. Unlike free-to-air channels, Astro satellite service offers 170 television channels and 20 radio stations that include all free-to-air channels along with international channels such as HBO, Cinemax, and Fox (Astro 2019).

Over the years Astro has received multiple criticisms not only from subscribers but also from local politicians, even though it provides so many interesting channels (Khairil Ashraf 2014).1) Subscribers’ complaints usually concern what they consider unnecessary fees for the average service that Astro provides, with constant disruptions especially during the monsoon season. Other complaints involve excessive advertising—showing Astro’s obvious capitalistic motives rather than a desire to provide excellent service to customers. Despite the negative feedback about Astro since it began broadcasting in 1996, the satellite service provider has never had serious competition in the market. With strong demand for a variety of channels, the people have only one legal option for satellite service—although many, especially in the rural areas, have opted to purchase unregistered illegal satellite dishes. Using such satellite dishes, they can receive multiple channels from outside the country without having to pay monthly fees; plus the content is not filtered by any government body, which allows users to enjoy original uncensored content.

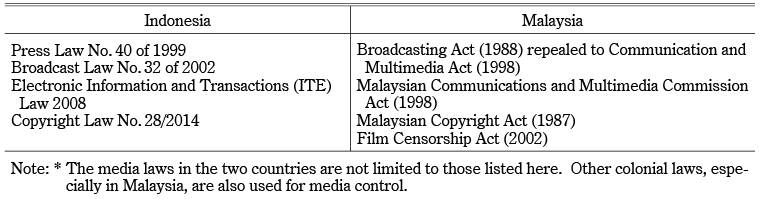

Malaysia has always been strict when it comes to filtering media content from foreign countries, particularly content originating and produced in Western nations. Media content that is seen as inappropriate, especially opposing Eastern and Islamic cultures and values, is banned from public viewing. The Film Censorship Board of Malaysia under the Ministry of Home Affairs plays a vital role in deciding what content can be broadcast in the Malaysian media. Film censorship laws, specifically the Film Censorship Act 2002,2) not only filter and oversee exported content but also oversee the production and showing of local films (Wan Mahmud et al. 2009). According to Wan Amizah Wan Mahmud (2008), the censorship system in Malaysia was not initially created by the Malaysian government per se but was one of the effects of British colonization. The British, according to Paul O’Higgins (1972), introduced such a policy in order to uphold and defend their dignity as masters in the occupied territory—which at the same time instilled the idea of censorship among local leaders as one of the ways to maintain their own status as the highest class in the societal hierarchy. It is believed that the main legacy of the British Empire in the field of media was not the craft of producing films, but the outline of the censorship system (Van der Heide 2002), which can still be seen today. It is also important to note that the Censorship Board reviews not only films but also trailers, newsreels, posters, advertisements, and short comedy films (Wan Mahmud et al. 2009). Hence, in order for local and international producers to have their content nationally broadcast, it is crucial for them to follow the guidelines provided by the Censorship Board.3) If they fail to follow instructions, their content is banned from national broadcasting; and extreme content can also be charged under the Film Censorship Act (2002). Some of the media laws in Indonesia and Malaysia that could be used to oversee transnational media content can be referred to in Table 2 below.

Table 2 Media Laws in Indonesia and Malaysia that Could Be Used to Oversee Transnational Media Content*

Although Indonesia’s censorship laws are not as strict as Malaysia’s, Indonesia also pays careful attention to content that is considered to be against Islamic values. For instance, in 2014 both countries banned the Hollywood film Noah claiming it went against Islamic beliefs (Nathan 2014). With Islam being the official religion in both countries, the Malaysian and Indonesian governments pay extra attention to any content that can affect Islamic values. In 2019 an Indonesian filmmaker, Garin Nugroho, received death threats for his film Memories of My Body, which portrays a male dancer exploring his sexuality and gender identity. In Indonesia there is no specific law to oversee content related to the LGBTQA+ community except in Acheh. However, for the majority Muslim population in Indonesia, such “Western” content is not acceptable (Malay Mail, May 11, 2019).

Transnational Media Flow: Indonesia and Malaysia

Historically, in many countries uncontrolled media flow has been viewed as a threat to national sovereignty and has shaped media policies (Hardt and Negri 2001; Flew 2012). Information flow from developed countries into Third World countries threatens the latter as foreign media content effectively surpasses the jurisdiction and authority of nation-states, eventually challenging the notion of national sovereignty and its effectiveness. Therefore, according to scholars like Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, government and politics “come to be completely integrated into the system of transnational command” (Hardt and Negri 2001, 307). In this section, we highlight some examples of how media content flows between Indonesia and Malaysia, with a specific focus on broadcast materials such as films, TV dramas, radio, and music.

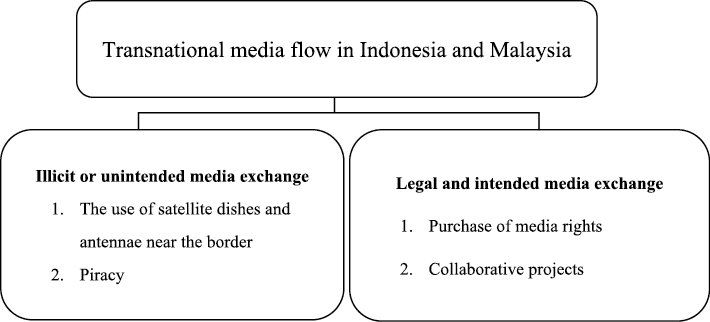

Transnational media content flows between Malaysia and Indonesia mainly through two modes of transmission: (1) illicit or unintended media exchange, including, especially at the national borders, the availability of illegal satellite dishes and DVD dealerships to accommodate local demand for foreign content; and (2) legal and intended media exchange (refer to Fig. 1). The intended media exchange discussed here focuses on content from Malaysia and the island of Java, where the Indonesian capital—Jakarta—is located and extensive use of the official Bahasa Indonesia rather than the Javanese language is recorded (Poedjosoedarmo 2006). Due to the diversity of languages in the Indonesian archipelago (Goebel 2013; 2016), media consumption in the country also varies (Sen and Hill 2006). Most media companies and government agencies are located in Java, but there are some also in Bali and Sumatra (Nugroho et al. 2012).

Fig. 1 Transnational Media Flow in Indonesia and Malaysia

In Indonesia and Malaysia, one of the catalysts facilitating transnational media content was satellite TV. With limited TV channels provided by the state, the use of satellite dishes was deemed necessary to increase options for media content. However, for many Indonesians and Malaysians, especially in the 1990s, satellite dishes were considered a luxury. Nonetheless, transnational satellite TV was a concern for both governments since content from the Western world was deemed a threat to the Asian values upheld by both nations (McDaniel 2002). For example, the introduction of Rupert Murdoch’s Star TV in 1991 was received differently by audiences and governments in Southeast Asian countries such as Indonesia and Malaysia. Many media policies were set up to handle the transnational flow of media content enabled by this new media technology.

The common view of upholding Asian values was not exclusive to Indonesia and Malaysia. In many other Southeast Asian countries with authoritarian regimes, the discourse on media policies was also centralized in censorship.4) Censorship was deemed necessary to prevent unwanted foreign media content. In the late 1990s, using the argument of preserving Asian values, Southeast Asian governments’ efforts to maintain censorship—to protect the public from “unsuitable” materials—faced an unlikely dilemma (McDaniel 2002). In Malaysia, for example, thanks to advanced media technologies—from satellite dishes to videocassettes—people living near the national borders in particular could easily access media content from neighboring countries without having to be concerned with the government’s censorship policy (McDaniel 2002). Why government policies concerning the cross-border flow of media content were ineffective during that time is yet to be fully understood.

Radio and Music

The history of the infiltration of Malaysian media content into Indonesia can be traced back to the increasing popularity of radio broadcasts in both countries in the post-independence period. Due to geographical proximity, broadcast signals from Malaysia are relatively easily received by Indonesian audiences, and vice versa. As a result, it is common for Indonesian listeners to tune into Malaysian radio stations. In West Kalimantan, for example, 18 Malaysian radio channels—including Muzik FM, TraXX FM, Klasik Nasional FM, Hot FM, Hitz FM, ERA (formerly Era FM), and Cats FM—are available for free to Indonesians living near the Malaysian border. To attract Indonesian listeners, Malaysian radio plays Indonesian pop songs.

In comparing the Malaysian music industry to the Indonesian one, it is safe to say that the latter is more advanced and prominent than the former (Heryanto 2008). Indonesian bands such as Peterpan, Sheila on 7, and Cokelat, among others, are well known among Malaysians. And in 2007, instead of choosing a local Malaysian band, Celcom—Malaysia’s largest and oldest telecommunications company—officially appointed Indonesia’s best-known music group, Peterpan, as the company’s new “power icon” as part of its marketing strategy (Heryanto 2008). Malaysia’s warm reception of Indonesian music is not recent: it goes back several decades to the success of artists such as Titiek Puspa, Lilis Suryani, and Vina Panduwinata (Sartono 2007, quoted in Heryanto 2008). In contrast to the success of Indonesian musicians in Malaysia, only a few Malaysian artists—such as Search, Siti Nurhaliza, and Sheila Majid—have managed to penetrate the Indonesian music industry (Tribune News, July 2, 2013).

The Indonesian and Malaysian governments have tried to cooperate in making collaborative broadcasts (McDaniel 1994). In the case of radio, Radio Republik Indonesia (RRI) has long collaborated with Radio Televisyen Malaysia (RTM) in broadcasting programs to reach audiences in both countries. One of the most famous such programs was Titian Muhibah (Bridge of harmony), broadcasting Indonesian and Malaysian songs to listeners in both countries. Similar programs were later introduced on television; TVRI broadcast a program with the same name in the 1990s. The television program was discontinued after Suharto resigned and the bilateral relationship between Indonesia and Malaysia became troublesome. In 2013 RRI made an unsuccessful attempt to work with RTM to produce a similar show, with the primary aim being to reach out to audiences living near the national borders of these neighboring nations, including areas like Pontianak, Sintang, Entikong, and Sarawak (Tribune News, July 2, 2013). Many of the programs co-produced by RRI and RTM were cultural shows, and one of them—Bermukun Borneo—continued until 2019. Intentional or legal transnational flows of media content were considered inconsistent and profoundly influenced by the internal political conditions in each country as well as the bilateral relationship between the two countries.

TV Dramas and Films

Unlike scholarly articles on the development of Indonesian cinema, little has been written about the history of Malaysian cinema (White 1996). Scholars have suggested that Indonesian media content has long been accepted by the Malaysian public (Van der Heide 2002; Heryanto 2008). This can be traced all the way back to the 1930s through the overwhelming popularity of media content such as the film Terang Boelan (Bright moon) in Malaya and Singapore. The success of Terang Boelan inspired the production of Malay films. This could be seen through the establishment of an Indonesian film house in Singapore in 1938 to cater to local demand for Malay media content (Norman Yusoff 2019). The popularity of Terang Boelan also inspired Shaw Brothers in Singapore to set up Malay Film Productions, which became one of the successful film companies in the region.

According to William van der Heide (2002), the popularity of the Malayan movie actor P. Ramlee in the 1950s beyond the Peninsula was regarded as having the potential to boost the export of Malayan movies to Indonesia. But Indonesia reacted negatively by imposing a strict protectionist policy—demanding that three Indonesian films be screened in the Peninsula for every Malayan movie exported to Indonesia—which resulted in a limited number of Malayan films being circulated in Indonesia (Latif 1989). Despite little success, some strategies, such as inviting Indonesian directors and actors to produce Malayan movies, were used to ensure the smooth distribution of Malayan films in Indonesia (Alauddin 1992).

The introduction of television in the early 1960s also contributed to the declining popularity of Malaysian movies among local audiences. Meanwhile, due to the technical superiority of Indonesian films, Malaysian viewers became more interested in their neighboring country’s films. Providing Malaysian audiences with Malay-language content, Indonesian movies of various genres—from action to dangdut musicals—became more popular in the 1970s (Sirat 1992). Even Perfima—the film company set up by P. Ramlee and a few others—initially imported popular Indonesian films before it produced local content (Van der Heide 2002).

In the 1980s Indonesian films could be accessed via state-owned channels operated by RTM, through programs such as Tayangan Gambar Indonesia (Indonesian film show) on TV1. At the same time, locally produced media content was shown on programs such as Tayangan Gambar Melayu (Malay film show). Due to the lack of local media products, RTM had to purchase rights to Indonesian films for RM3,000–5,000 from local distributors. The cost to purchase Indonesian content was considered reasonable to fill in the vacant slots on RTM TV channels. The same approach was taken by TV3, a private TV channel that was established in 1983 (Abdul Wahab et al. 2013). TV3 at that time, aware of the trend, also featured Indonesian films alternately with Malay films through its program Malindo Theater (Norman Yusoff 2019).

In the early 2000s, some of the Indonesian films popular in Malaysia were Ada Apa Dengan Cinta (What’s up with love, 2002), Eiffel I’m in Love (2003), Heart (2006), and Ayat-Ayat Cinta (Verses of love, 2008). Ada Apa Dengan Cinta, which was released in Malaysia in 2003, received positive feedback, especially from young adults. Observers of the local art scene posited that the film contributed to the emergence of a subculture centralized in Indonesian poetry in Malaysia. In 2016 a prequel of the movie, Ada Apa Dengan Cinta 2, was released in the Malaysian market, 13 years after the release of its predecessor. Recorded as the highest-grossing Indonesian movie in Malaysia, Ada Apa Dengan Cinta 2 reaped more than RM2.5 million in box office takings within a week and surpassed RM4 million revenue after its 12th day of screening (Chua 2016a; 2016b).

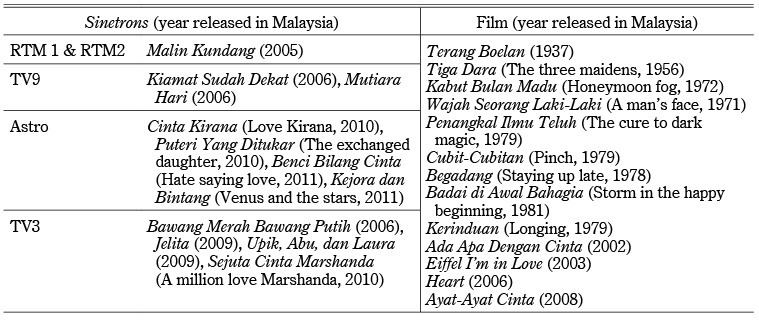

Indonesian TV dramas, better known as sinetrons, also became popular in Malaysia. According to Josscy Aartsen (2011), the popularity of Indonesian media content as an official import to Malaysia was initially due to cheaper copyrights compared to Western media content, especially during the financial crisis in the 1990s. The overwhelming acceptance of Indonesian sinetrons led to the establishment of exclusive slots on Malaysian TV networks. For example, in 2006 TV9—a channel under Media Prima, one of the largest media agencies in Malaysia—dedicated a daily slot to broadcast Indonesian TV dramas (Abdul Wahab et al. 2013). This was seen as an effort to compete with other TV stations that were also actively broadcasting Indonesian sinetrons. Some Indonesian dramas were hugely popular among Malaysian viewers: for example, Kiamat Sudah Dekat (The end is near, 2003) had a viewership of over 1 million. And Mutiara Hari (Pearl of the day), which was initially released on SCTV in Indonesia in 2005, had a viewership of 1.6 million on TV9 (Abdul Wahab et al. 2013). Tabulated in Table 3 above are some of the Indonesian sinetrons and films broadcasted in Malaysia over the years.

Table 3 Some Indonesian Sinetrons and Films in Malaysia

Unlike the penetration of Indonesian films into Malaysian media, Malaysian media content was not well received in Indonesia (Van der Heide 2002). This could have been due to a few factors, such as the plethora of choices within Indonesia and slower development of the entertainment industry in Malaysia. According to Khairi Ahmad (1988, 9), at least in the 1980s, Indonesian audiences found that Malaysian films were not as attractive as local content or other foreign films. Some Malaysian films that succeeded in breaking into the Indonesian market were those by P. Ramlee, such as Seniman Bujang Lapok (The three bachelor artists), Nujum Pak Belalang (Pak Belalang the necromancer), Bakti (Services), among others (Khairi Ahmad 1988). Bakti, which was released in 1950, received a particularly overwhelming response from the Indonesian public due to the widespread publicity provided by newspapers in Singapore such as Utusan Melayu, Utusan Zaman, and Mastika (Sahidan Jaafar 2019; Abdullah Hussain 2003):

The Oranje Theater was a first-class stage that usually showed only big movies from the West. At the time the film Bakti was aired on the Oranje Medan Medan stage in the 1950s, some of the main streets around the theater were jammed with vehicles and humans. (Abdullah Hussain 2003, 17)

Other than films by P. Ramlee, in the 1990s other films also managed to break into the Indonesian market. One was Fenomena (Phenomenon). The success of this film was catalyzed by the popularity of the lead actor, Amy Search, who was also a member of the popular Malaysian rock band Search. In 1989, a year before the film was released in the Indonesian market, the rock band released its album Fenomena, which received overwhelming support from Indonesian audiences—over 2 million copies were sold (Raja 2017).

Various efforts to co-produce movies between the two countries were initiated after the formation of ASEAN in 1967, but they materialized only in the late 1980s. Eventually several films were produced, including the popular Irisan-Irisan Hati (Shreds of the heart) (Lim 1989). There were also successful attempts by filmmakers to incorporate celebrities from Indonesia and Malaysia in their films. For instance, Isabella (1990) was directed by the Indonesian director Marwan Alkatiri and featured the Malaysian actor Amy Search and Indonesian actor Nia Zulkarnain. Other collaborative films included Gadis Hitam Putih (The black and white woman, 1986), directed by Wahyu Sihombing, and Gelora Cinta (The surge of love, 1992) by Aziz Sattar (Norman Yusoff 2019). While such collaboration was applauded by the Malaysian film industry, it gained little interest from its Indonesian counterpart (Said 1991).

Unlike successful Indonesian sinetrons in Malaysia, only a small number of Malaysian TV shows managed to penetrate the Indonesian market. In the late 1980s there were only two notable Malaysian television shows popular in Indonesia: the soap opera Primadona (Primadonna, 1989) and the variety show Titian Muhibah (1990). One of the best contemporary examples of Malaysian media content popular in Indonesia is the animation series Upin & Ipin, by Les’ Copaque Production. The children’s show has been broadcast on the Indonesian TV channel MNCTV since 2007.

Media Piracy in Indonesia and Malaysia

Audiences in both countries also enjoyed relatively easy access to transnational media content through pirated media. In Indonesia, for example, the government found it difficult to eliminate media piracy. The development of videocassettes in the 1980s is viewed as having kickstarted media piracy in Indonesia (Rosihan Anwar 1988). Locals made copies of videocassettes in order to meet the demand for a variety of films without having to spend much money going to the cinema. The booming piracy business led to a decline in the production of Indonesian movies in the early 1980s (Rosihan Anwar 1988). New films were recorded as soon as they were available in theatres, and videocassettes of the films were promptly distributed by video rental shops. Many of the recordings were made illegally and disseminated without obtaining video rights from the producers. Efforts were made by the Indonesian government to eliminate piracy and exert more control, but no significant success was achieved (Khairi Ahmad 1988).

In the 1990s, pirated media content in most Southeast Asian countries was distributed via counterfeit VCDs or DVDs due to the lack of access to online media. Even though pirated media is illegal in Indonesia, 90 percent of the VCDs distributed in the market were pirated copies (Van Heeren 2012). Most pirated media offers relatively cheap access to transnational content. Hollywood box office movies were “often for sale on the streets before they even premiere in local theaters” (Baumgärtel 2007, 53). Pirated VCDs and DVDs also offered pornographic materials, Western music albums, and computer software and games. The only regulation that could be used to eradicate the practice of media piracy was Copyright Law No. 28/2014. However, the issue was more law enforcement than regulation.

Following the increasing penetration of the Internet in Indonesia, this newest medium has provided an alternative way for Indonesians to access transnational content. While it is true that a variety of media content from many countries is now easily available to Internet users in Indonesia, there is also a tendency to utilize this relatively cheap medium to access and distribute pirated media content. Even though the government tried to minimize online piracy through the implementation of Information and Electronic Transaction Law No. 11/2008, the government’s efforts to prevent the distribution of online pirated content seemed to focus mainly on blocking pornographic websites.

Even though censorship has been in place in Malaysia since the country’s independence in 1957, citizens can bypass bans through illegal Internet downloads. Banned media content can also be purchased from pirated VCD/DVD dealers (Yow 2015). Thus, it is not surprising that even though the Malaysian Censorship Board banned 50 Shades of Grey in 2015, people in the country are able to get their hands on an illegal copy of the movie through the ever-free Internet and illegal VCD/DVD dealers. The introduction of Malaysian Copyright Act 1987 proved that the government took piracy seriously and eventually hoped to put an end to it. Unfortunately, although illegal VCD/DVD dealers have been subjected to numerous raids by the authorities, their numbers are unlikely to decrease as the demand for illegal content is very high among Malaysians. For those who have slow Internet speed, it is more practical to buy illegal copies of VCDs or DVDs from unlawful dealers at prices starting from RM10 each, with discounts available for bulk purchases. The existence of illegal VCD and DVD dealerships not only raises questions about the relevance of stringent censorship but also explains one of the ways in which transnational content can be exchanged between countries.

Satellite Dishes and Antennae to Access TV Shows and Films

As in the case of radio, which was discussed in the previous section, Indonesian television owners in Northern Sumatra and West Kalimantan were able to access Malaysian television programs due to leaks of the broadcasting signal. In the late 1980s, television programs from the Malaysian channel TV3 were so popular in Sumatra that most Indonesian audiences were not aware they were enjoying programs from another country (Sen and Hill 2006). Other than TV3, two other mainstream Malaysian TV channels were also available for free beyond the Malaysian border in West Kalimantan—RTM1 and RTM2. Malaysians living near the border also have access to a few Indonesian television channels. In Johor, for example, residents can easily watch the three oldest Indonesian channels for free without having to subscribe to any cable or satellite service. Johor is located near Singapore and Indonesia. Hence, Singaporean and Indonesian channels are easily transmitted beyond the Malaysia-Indonesia and Malaysia-Singapore borders. By purchasing a standard outdoor antenna, viewers can enjoy TPI, RCTI, and SCTV from Indonesia as well as television channels from Singapore (Mohammad Faiq 2007). This can be considered as an unintended or unintentional transnational flow of media content, since the content comes via either illegal or unofficial transmission.

Likewise, the use of parabolic antennas in rural areas is seen as an essential unofficial medium for audiences in Indonesia to obtain transnational programs, including television programs from Malaysia, and vice versa. Compared to before the early 1990s, these days the numbers of satellite dishes in the country has decreased remarkably. In 1991, to control information flows from outside the country through alternative means such as privately owned satellite dishes, the Malaysian government announced a ban on all privately owned satellite dishes. The ban was described as highly necessary and a matter of highest national unity and security and also one of the ways to preserve Malaysian morals and values (Davidson 1998). With the ban in place, the Malaysian government aimed to control the massive flow of foreign media content into the country, worrying that without censorship, “dangerous” media content could easily influence Malaysians and not only jeopardize Malaysian culture but also threaten national harmony. However, as previously discussed, by the mid-1990s Astro Holdings was given the exclusive rights to provide satellite broadcasting services in the country. Ownership of satellite receivers other than Astro’s is considered illegal without a license—and owners of such receivers without the proper documentation and permits face confiscation of equipment as well as a hefty fine if discovered.

Private enterprises attempted to further encourage cross-border content broadcasting between Indonesia and Malaysia. One of the most prominent examples was the establishment of Astro Nusantara in 2006. As Malaysia’s sole satellite television service, this company signed an agreement with a local Indonesian company to establish its business in the Indonesian media market. Unfortunately, due to a stock dispute between the two majority shareholders, Astro Malaysia and Lippo Group, Astro Nusantara was dissolved in October 2008 (Malaysia Today, May 1, 2012). There was another reason why the Indonesian government supported the disbanding of Astro Nusantara. Indonesian Member of Parliament Dedy Malik argued that the Malaysian broadcasting company violated the broadcasting rules set by Indonesia’s Ministry of Communication and Information, especially the reciprocity clause (Tempo, March 3, 2006). Astro Malaysia was given a license to broadcast Malaysian content to Indonesian audiences, but this Malaysian satellite service did not transmit Indonesian content to Malaysian viewers.

Better Acceptance of Indonesian Content

We found that there were several reasons for the better acceptance of Indonesian media content in Malaysia than vice versa. Audiences in Malaysia found that Indonesian radio and television programs shared similar cultural values as their own; thus, it was easy for them to accept Indonesian content. Researchers such as Latifah Pawanteh et al. (2009) observed that at least for Malaysian media audiences, Asian media content such as Indonesia’s had relatable storylines and was relevant to their daily lives. The use of relatively identical language in the two countries in addition to Muslim-friendly content facilitated better acceptance of Indonesian content in Malaysia (Khairi Ahmad 1988). Moreover, since the majority of the population in both countries is Muslim, that further facilitates the flow of media between the two countries, mainly from Indonesia to Malaysia. Our analysis of media laws in both countries found that their regulations outlawed content that was deemed to be against Islamic values, such as explicit sexual content and gambling. In the case of Indonesian audiences, local media content is more popular than Malaysian content since Indonesia has a more advanced media industry and there are diverse options to choose from. Local media content is more popular among Indonesians also as it reflects Indonesian values. Some of the local media content is even produced in indigenous languages such as Javanese and Sundanese (Goebel, 2013), which makes it more appealing to local audiences (Sen and Hill 2006).

The entertainment industry in Indonesia is seen to be a step ahead of Malaysia’s. In 2017 Indonesia was the world’s 16th-biggest film market and the largest in Southeast Asian (Jakarta Post, December 14, 2018). Unlike Malaysian media products, Indonesian content is not only widely accepted by a global audience, but much of its profit is derived from the local market. With a population of 241 million in 2018 (Freedom House 2019), Indonesia undeniably has a larger talent pool than Malaysia. Due to Indonesia’s large population, its media market has greater potential for distributing local products. Its large population also makes Indonesia one of the most promising markets for the entertainment business in Asia (Jakarta Post, December 14, 2018; Chan 2019).

Low English proficiency among Indonesians is also deemed to be one of the factors contributing to the flourishing media industry in Indonesia. According to Itje Chodidjah, (2007) the dispersed geography of the Indonesian archipelago made it difficult to spread an English education. Low English proficiency led Indonesian audiences to prefer local rather than foreign content. Although Indonesia has diverse ethnicities and different languages, Bahasa Indonesia is the state’s officially mandated lingua franca (Rahmi 2015). Malay was used as an official language of Indonesia in 1918 (Moeliono 1993), primarily because colonial officials were concerned that if Dutch was extensively used, Indonesians would have easy access to political ideologies from abroad (Alisjahbana 1957; Lamb and Coleman 2008). In the 1920s, during the nationalist uprising in Indonesia, the nationalist movement declared Bahasa Indonesia as the language of solidarity for all Indonesians (Lamb and Coleman 2008). All these factors led to better acceptance of local media products than foreign materials and eventually contributed to the ever growing local media industry. Also, among the working class in Indonesia, local content was viewed as more relatable as it was imbued with familiar daily Indonesian values; this further contributed to the thriving entertainment industry in the state. Since the Indonesian entertainment industry was deemed good enough for Indonesians, foreign content—including that of Malaysian origin—was deemed inferior. The flourishing media industry in Indonesia provided better opportunities for the production of diverse media content than Malaysia. This was especially true after the fall of the Suharto regime in 1998, ending stringent control over media in Indonesia. The liberalization of the press in Indonesia resulted in the production of colorful media content that is still well received by international audiences, including Malaysians.

Conclusion

Our findings revealed that the Indonesian and Malaysian governments paid more attention to the flow of Western media content than to content from neighboring countries that shared the same religion and cultural values. As illustrated previously, hostility toward Western content could be seen through a more stringent body of laws in both countries prohibiting—often through censorship—materials that went against local norms (Wan Mahmud et al. 2009). At the same time, there is no record of an aggressive approach having been taken by either government when dealing with the illegal transmission of media content between these two countries, particularly near the border. Other than concerns over different religious and cultural values, governments were also concerned about the introduction of a consumer culture and liberal political ideologies from the West. Therefore, Western media content was more closely monitored and controlled through stringent media laws and policies (Ade Armando 2011). Such media content was viewed not only as an economic threat but also as a potential threat to national security.

As for the transnational flow of content between Indonesia and Malaysia, minimal documentation has been found to indicate that there were extensive official media exchanges between these two countries. In fact, scholars such as Van der Heide (2002) posited that scholarly discussion on the film industry in Asia often overlooked the Malaysian context. Based on our exploratory analysis, there was a lot of Indonesian entertainment content in Malaysia but minimal Malaysian content in the Indonesian media space. This was due to factors such as a better-developed entertainment industry in Indonesia, and a freer media environment in Indonesia, particularly after the fall of Suharto. Indonesians were found to prefer local rather than Malaysian content due to factors such as language and the sense of familiarity with Indonesian values depicted by locally produced broadcast media.

Also, minimal records have been found to indicate that either country paid close attention to media flows, especially the illicit transnational media flows in border areas. Not much action was taken to control the cross-border flow of content. It can be assumed that content from both countries was considered “safe” due to the countries’ common shared cultural and religious values; also, illegal content could flow transnationally only near the national border areas, and no significant amount of exchange was reported. Illicit cross-border broadcasts and content are believed to spread not much farther than the border areas of Malaysia and Indonesia.

Since the relationship between Indonesia and Malaysia has been somewhat unstable for several decades, media exchange may be seen as one way to rekindle the relationship. It is surprising that although several efforts have been made to improve the relationship, especially through strategic agreements, minimal efforts have focused on extensive media exchange. In the 1990s the two countries tried to work together on programs like Titian Muhibah, but since then no similar efforts have been made. Increased media exchange between Indonesia and Malaysia can serve the diplomatic purpose of improving the bittersweet bilateral relationship between these Nusantara countries.

Since this study was conducted through historical research, it is exploratory in nature. Minimal resources were found about official media exchanges between Indonesia and Malaysia. The issue can be further explored through interviewing media providers from both countries to see whether there are any bilateral agreements on broadcast media content. Research can also focus on interviewing diplomats from both countries to better understand the bilateral relationship between Indonesia and Malaysia. Through these interviews, researchers will be able to gain updated information on Indonesia’s and Malaysia’s media exchange initiatives and better understand how media exchange can serve as a diplomatic approach. Since there is also minimal proper documentation on unintended transnational media flows near the national borders, it would be best to explore this topic by interviewing and requesting official documentation from the relevant authorities in both countries.

Accepted: March 2, 2020

References

Articles and Books

Aartsen, Josscy Vallazza. 2011. Film World Indonesia: The Rise after the Fall. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Utrecht University.

Abdullah Hussain. 2003. Liku-Liku hidup P. Ramlee. Simposium seniman agung P. Ramlee [The life of P. Ramlee: P. Ramlee. Great artist symposium]. Kuala Lumpur: Penerbit Universiti Malaya.

Abdul Wahab, Juliana; Kim Wang Lay; and Syed Baharuddin, Sharifah Shahnaz. 2013. Asian Dramas and Popular Trends in Malaysian Television Industry. Jurnal Komunikasi: Malaysian Journal of Communication 29(2): 159–174.

Ade Armando. 2011. Televisi Jakarta di atas Indonesia: Kisah kegagalan sistem televisi berjaringan di Indonesia [Jakarta Television above Indonesia: A Story of the failure of the networked television system in Indonesia]. Yogyakarta: Bentang Pustaka.

Agus Sudibyo; and Patria, Nezar. 2013. The Television Industry in Post-authoritarian Indonesia. Journal of Contemporary Asia 43(2): 257–275.

Alauddin, Raja Ahmad. 1992. A Brief History of the Development of Indonesian Films in Malaysia. In Indonesian Film Panorama, edited by Salim Said and Jason Edison Siahaan, pp. 83–87. Jakarta: Permanent Committee of the National Indonesia Film Festival.

Alisjahbana, S. Takdir. 1957. Dari perdjuangan dan pertumbuhan bahasa Indonesia [From the struggle and the growth of the Indonesian language]. Jakarta: Pustaka Rakjat.

Baumgärtel, Tilman. 2007. The Social Significance and Consequences of Digital Piracy in Southeast Asia: The Case of Independent Filmmakers. Philippine Sociological Review 55(January): 50–63.

Brüggemann, Michael; and Schulz-Forberg, Hagen. 2009. Becoming Pan-European? Transnational Media and European Public Sphere. International Communication Gazette 71(8): 693–712.

Chodidjah, Itje. 2007. Teacher Training for Low Proficiency Level Primary English Language Teachers: How It Is Working in Indonesia. In Primary Innovations: A Collection of Papers, edited by Laura Grassik, pp. 87–94. Hanoi: British Council.

Chong Jinn Winn. 2012. “Mine, Yours or Ours?”: The Indonesia-Malaysia Disputes over Shared Cultural Heritage. SOJOURN: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 27(1): 1–53.

Cohen, Jonathan. 2008. What I Watch and Who I Am: National Pride and the Viewing of Local and Foreign Television in Israel. Journal of Communication 58(1): 149–167.

Crofts Wiley, Stephen B. 2004. Rethinking Nationality in the Context of Globalization. Communication Theory 14(1): 78–96.

Davidson, Aaron. 1998. I Want My Censored MTV: Malaysia’s Censorship Regime Collides with the Economic Realities of the Twenty-First Century. Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law 31: 97–112.

Elias, Juanita. 2013. Foreign Policy and the Domestic Worker: The Malaysia–Indonesia Domestic Worker Dispute. International Feminist Journal of Politics 15(3): 391–410.

Esser, Frank; and Strömbäck, Jesper. 2012. Comparing News on National Elections. In The Handbook of Comparative Communication Research, edited by Frank Esser, Jesper Strömbäck, and Thomas Hanitzsch, pp. 289–326. New York: Routledge.

Flew, Terry. 2012. Globalisation, Media Policy, and Regulatory Design: Rethinking the Australian Media Classification Scheme. Australian Journal of Communication 39(2): 1–17.

Flew, Terry; and Waisbord, Silvio. 2015. The Ongoing Significance of National Media Systems in the Context of Media Globalization. Media, Culture & Society 37(4): 620–636.

George, Cherian. 2006. Contentious Journalism: Towards Democratic Discourse in Malaysia and Singapore. Singapore: Singapore University Press in association with University of Washington Press.

Goebel, Zane. 2016. Superdiversity from Within: The Case of Ethnicity in Indonesia. In Engaging Superdiversity: Recombining Spaces, Times and Language Practices, edited by Karel Arnaut, Martha Sif Karrebæk, Massimiliano Spotti, and Jan Blommaert, pp. 251–276. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

―. 2013. The Idea of Ethnicity in Indonesia. Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies: Paper 71(1): 1–30.

Hardt, Michael; and Negri, Antonio. 2001. Empire. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Herman, Edward; and McChesney, Robert. 2004. The Global Media: The New Missionaries of Corporate Capitalism. London: Cassell.

Heryanto, Ariel. 2008. Pop Culture and Competing Identities in Popular Culture in Indonesia: Fluid Identities in Post-authoritarian Politics. New York: Routledge.

Iga Tsukasa. 2012. A Review of Internet Politics in Malaysia. Asian Politics and Policy 4(1): 137–140.

Kakiailatu, Toeti. 2007. Media in Indonesia: Forum for Political Change and Critical Assessment. Asia Pacific Viewpoint 48(1): 60–71.

Kearney, Michael. 1995. The Local and the Global: The Anthropology of Globalization and Transnationalism. Annual Review of Anthropology 24: 547–565.

Khairi Ahmad. 1988. Perkembangan filem Malaysia di negara sekitar [The development of Malaysian films in neighboring countries]. Kuala Lumpur: Penerbitan Empayar.

Khalid, Khadijah Md.; and Yacob, Shakila. 2012. Managing Malaysia–Indonesia Relations in the Context of Democratization: The Emergence of Non-state Actors. International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 12(3): 355–387.

Killias, Olivia. 2010. “Illegal” Migration as Resistance: Legality, Morality and Coercion in Indonesian Domestic Worker Migration to Malaysia. Asian Journal of Social Science 38(6): 897–914.

Kim Wang Lay. 2001. Media and Democracy in Malaysia. Journal of the European Institute for Communication and Culture 8(2): 67–88.

Kitley, Philip. 2014. Television, Nation, and Culture in Indonesia. Athens: Ohio University Press.

―. 2003. Closing the Creativity Gap – Renting Intellectual Capital in the Name of Local Content: Indonesia in the Global Television Format Business. In Television across Asia, edited by Michael Keane and Albert Moran, pp. 150–168. New York: Routledge.

Kraidy, Marwan M. 2002. Globalization of Culture through the Media. In Encyclopedia of Communication and Information, edited by Jorge Reina Schement, pp. 359–363. New York: Macmillan Reference USA.

Lamb, Martin; and Coleman, Hywel. 2008. Literacy in English and the Transformation of Self and Society in Post-Soeharto Indonesia. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 11(2): 189–205.

Latif, Baharuddin. 1989. Hubungan Indonesia/Malaysia di dalam pameran filem [Indonesia/Malaysia relations in film exhibition]. In Cintai filem Malaysia [Love Malaysian films], edited by Baharuddin Latif, pp. 245–247. Hulu Kelang: Perbadanan Kemajuan Filem Nasional Malaysia [National Film Development Corporation Malaysia].

Lee Sangoak. 2007. A Longitudinal Analysis of Foreign Program Imports on South Korean Television, 1978–2002: A Case of Rising Indigenous Capacity in Program Supply. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 51(1): 172–187.

Lim, Rebecca. 1989. Penerbitan bersama Malaysia-Indonesia [Malaysian-Indonesian coproductions]. In Cintai filem Malaysia [Love Malaysian films], edited by Baharuddin Latif, pp. 211–214. Hulu Kelang: Perbadanan Kemajuan Filem Nasional Malaysia [National Film Development Corporation Malaysia].

Mackie, James Austin Copland. 1974. Konfrontasi: The Indonesia-Malaysia Dispute, 1963–1966. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press.

McBride, Sean. 1980. Many Voices, One World. Report by the International Commission for the Study of Communication Problems. New York: UNESCO.

McDaniel, Drew. 2002. Electronic Tigers of Southeast Asia: The Politics of Media, Technology and National Development. Ames: Iowa State University Press.

―. 1994. Broadcasting in the Malay World: Radio, Television, and Video in Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore. Norwood: Greenwood Publishing Group.

Moeliono, Anton M. 1993. The First Efforts to Promote and Develop Indonesian. In The Earliest Stage of Language Planning: The “First Congress” Phenomenon, edited by Joshua A. Fishman, pp. 129–141. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Mohd Sani, Mohd Azizuddin. 2004. Media Freedom in Malaysia. Journal of Contemporary Asia 35(3): 341–367.

Muhammad Ghazali bin Shafie. 1964. Confrontation: A Manifestation of the Indonesian Problem: Speech by Dato Mohd Ghazali bin Shafie, Permanent Secretary for External Affairs, Malaysia, at the Conference of the Junior Chamber International in Penang on 1st May, 1964. Federal Department of Information Malaysia. Kuala Lumpur: Lai Than Fong Press.

Norman Yusoff. 2019. Budaya filem Indonesia di Malaysia [Indonesian film culture in Malaysia]. Utusan Malaysia. June 16, p. 13.

Nugroho, Yanuar; Putri, Dinita Andriani; and Laksmi, Shita. 2012. Mapping the Landscape of the Media Industry in Contemporary Indonesia. Manchester: Centre for Innovation Policy & Governance.

O’Higgins, Paul. 1972. Censorship in Britain. Nashville: Thomas Nelson.

Paek Hye-Jin; and Pan Zhongdang. 2004. Spreading Global Consumerism: Effects of Mass Media and Advertising on Consumerist Values in China. Mass Communication & Society 7(4): 491–515.

Pawanteh, Latifah; Rahim, Samsudin A.; and Ahmad, Fauziah. 2009. Media Consumption among Young Adults: A Look at Labels and Norms in Everyday Life. Jurnal Komunikasi: Malaysian Journal of Communication 25: 21–31.

Poedjosoedarmo, Gloria. 2006. The Effect of Bahasa Indonesia as a Lingua Franca on the Javanese System of Speech Levels and Their Functions. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 2006(177): 111–121.

Rahmi. 2015. The Development of Language Policy in Indonesia. Englisia: Journal of Language, Education, and Humanities 3(1): 9–22.

Rosihan Anwar. 1988. The Indonesian Film Industry. Media Asia 15(3): 134–137.

Sahidan Jaafar. 2019. P. Ramlee cetus fenomena di Nusantara [P. Ramlee causes a phenomenon in Nusantara]. Utusan Malaysia. February 7, p. 23.

Said, Salim. 1991. Shadows on the Silver Screen: A Social History of Indonesian Film. Jakarta: Lontar Foundation.

Sen, Krishna; and Hill, David T. 2006. Media, Culture and Politics in Indonesia. Jakarta: Equinox.

Sen, Krishna; and Lee, Terence, eds. 2008. Political Regimes and the Media in Asia, Vol. 8. Abingdon: Routledge.

Sirat, Mohd. Kamsah. 1992. Indonesian Films in Singapore. In Indonesian Film Panorama, edited by Salim Said and Jason Edison Siahaan, pp. 88–91. Jakarta: Permanent Committee of the National Indonesia Film Festival.

Slater, Dan. 2010. Ordering Power: Contentious Politics and Authoritarian Leviathans in Southeast Asia. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Van der Heide, William. 2002. Malaysian Cinema, Asian Film: Border Crossings and National Cultures. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Van Heeren, Katinka. 2012. Contemporary Indonesian Film: Spirits of Reform and Ghosts from the Past. Brill: KITLV Press.

Wan Mahmud, Wan Amizah. 2008. Perkembangan dan pembangunan sistem dan dasar penapisan: Apakah itu cetak rompak Internet [Development of censorship system and policies: What is Internet piracy]. PhD dissertation, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia.

Wan Mahmud, Wan Amizah; Kee Chang Peng; and Aziz, Jamaluddin. 2009. Film Censorship in Malaysia: Sanctions of Religious, Cultural and Moral Values. Jurnal Komunikasi: Malaysian Journal of Communication 25: 42–49.

White, Timothy. 1996. Historical Poetics, Malaysian Cinema, and the Japanese Occupation. Kinema: A Journal for Film and Audiovisual Media 8(1): 1–12.

Willnat, Lars; Wong, W. Joan; Tamam, Ezhar; and Aw, Annette. 2013. Online Media and Political Participation: The Case of Malaysia. Mass Communication and Society 16(4): 557–585.

Online Sources

Anton Hermansyah. 2016. Netflix Confuses Indonesian Censorship Agency. Jakarta Post. May 11. https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2016/05/11/netflix-confuses-indonesian-censorship-agency.html, accessed July 17, 2016.

Astro. 2019. About Astro Malaysia Holdings Bhd. https://corporate.astro.com.my/our-company/about-us, accessed May 13, 2019.

Chan, Francis. 2018. Malaysia and Indonesia Pledge to Build on Strong Bilateral Ties. Straits Times. June 30. https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/malaysia-and-indonesia-pledge-to-build-on-strong-bilateral-ties, accessed December 17, 2018.

Chan, Ronald W. 2019. Investors Should Buy a Ticket to Indonesia: A Burgeoning Middle Class, and Investment and Expertise from Overseas, Are Reviving the Country’s Once-Thriving Film Sector. Bloomberg. April 6. https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2019-04-06/indonesia-s-movie-industry-should-attract-investors, accessed November 1, 2019.

Chua, Dennis. 2016a. AADC2, the Highest Grossing Indo Movie in Malaysia. New Straits Times. May 5. https://www.nst.com.my/news/2016/05/143734/aadc2-highest-grossing-indo-movie-malaysia-video, accessed October 23, 2017.

―. 2016b. “Ada Apa Dengan Cinta 2” Surpasses RM4m Box Office Mark. New Straits Times. May 10. https://www.nst.com.my/news/2016/05/144834/ada-apa-dengan-cinta-2-surpasses-rm4m-box-office-mark, accessed October 23, 2017.

Freedom House. 2019. Indonesia Country Report. https://freedomhouse.org/country/indonesia, accessed November 3, 2019.

Gher, Leo; and Bharthapudi, Kiran. 2004. The Impact of Globalization and Transnational Media in Eastern Europe at the End of the 20th Century: An Attitudinal Study of Five Newly Independent States. Global Media Journal 3(4). http://lass.purduecal.edu/cca/gmj/sp04/gmj-sp04-gher-bharthapudi.htm, accessed July 17, 2016.

Jakarta Post. 2018. Indonesia among Film Markets with Most Potential in Asia-Pacific: Producer. December 14. https://www.thejakartapost.com/life/2018/12/14/indonesia-among-film-markets-with-most-potential-in-asia-pacific-producer.html, accessed February 2, 2019.

Kanapathy, Vijayakumari. 2006. Migrant Workers in Malaysia: An Overview. In Country Paper Prepared for Workshop on East Asian Cooperation Framework for Migrant Labour. Kuala Lumpur: Institute of Strategic and International Studies. December. http://www.isis.org.my/files/pubs/papers/VK_MIGRATION-NEAT_6Dec06.pdf, accessed January 13, 2007.

Katrina Khairul Azman. 2019. BN MP: LGBT and Sex Scenes on Netflix Should Be Censored for Malaysia. Says. March 28. https://says.com/my/news/bn-mp-netflix-should-censor-lgbt-and-sex-scenes-in-malaysia, accessed March 31, 2019.

Kelion, Leo. 2016. Netflix Blocked by Indonesia in Censorship Row. BBC. January 28. https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-35429036, accessed May 15, 2017.

Khairil Ashraf. 2014. Bung: Astro Menipu Rakyat dan Kerajaan [Bung: Astro is deceiving the people and the government]. Free Malaysia Today. November 11. http://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/bahasa/2014/11/19/bung-astro-menipu-kerajaan-dan-rakyat/, accessed March 13, 2016.

Malay Mail. 2019. Indonesian Director Calls for LGBT+ Debate after Film Ban. May 11. https://www.malaymail.com/news/showbiz/2019/05/11/indonesian-director-calls-for-lgbt-debate-after-film-ban/1751846, accessed December 2, 2019.

Malaysia, Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 2015. Malaysia Indonesia Bilateral Relations. Embassy of Malaysia, Jakarta. http://www.kln.gov.my/web/idn_jakarta/history, accessed June 16, 2016.

Malaysia, Ministry of Home Affairs. 2012. Corporate Information: Lembaga Penapis Filem Malaysia [Film Censorship Board of Malaysia]. Ministry of Home Affairs. http://www.moha.gov.my/index.php/en/maklumat-korporat/maklumat-bahagian/lembaga-penapis-filem, accessed October 19, 2017.

Malaysia Today. 2012. Ananda Krishnan’s No. 2 Wanted in Indonesia to Face Fraud Charges. May 1. http://www.malaysia-today.net/2012/05/01/ananda-krishnans-no-2-wanted-in-indonesia-to-face-fraud-charges/, accessed July 6, 2017.

Mohamad Rizal Maslan. 2010. Menkominfo harus waspadai siaran asing di perbatasan [Menkominfo must be aware of foreign broadcasts at the border]. Detik. February 19. http://news.detik.com/read/2010/02/19/175158/1303129/10/menkominfo-harus-waspadai-siaran-asing-di-perbatasan?nd992203605, accessed April 14, 2017.

Mohammad Faiq. 2007. Menikmati acara TV di Malaysia [Enjoying TV shows in Malaysia]. GRIYA MAYA FAIQ. February 2. https://f4iqun.wordpress.com/2007/04/02/menikmati-acara-tv-di-malaysia/, accessed July 10, 2015.

Nathan, Fred. 2014. Malaysia and Indonesia Ban Noah Film: Film Censoring Bodies in Both Countries Said that the Portrayal of the Prophet by Russell Crowe Was against Islamic Laws. Telegraph. April 7. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/film/10751254/Malaysia-and-Indonesia-ban-Noah-film.html, accessed June 16, 2016.

Raja Nurfatimah Mawar Mohamed. 2017. Album Fenomena Search diabadikan dalam piring hitam [Search’s Fenomena album is immortalized in vinyl records]. Berita Harian. April 22. https://www.bharian.com.my/node/274722, accessed March 20, 2018.

Tempo. 2006. Pemerintah diminta hentikan stasiun Astro [Government orders Astro broadcasting station to shut down]. March 3. https://bisnis.tempo.co/read/74763/pemerintah-diminta-hentikan-stasiun-astro, accessed October 13, 2015.

Tribune News. 2013. RRI pererat hubungan dua negara [RRI strengthens two-state relations]. July 2. http://pontianak.tribunnews.com/2013/07/02/rri-pererat-hubungan-dua-negara, accessed June 15, 2017.

Yow Chung Lee. 2015. Is the Film Censorship Board Relevant? Malaysian Insider. July 18. http://www.themalaysianinsider.com/sideviews/article/is-the-film-censorship-board-relevant-yow-chong-lee, accessed October 18, 2017.

1) Khairil Ashraf (2014) mentions Bung Mokhtar, a local politician from Sabah.

2) The first Act to be adopted was the Cinematograph Films Act 1952 (Amendment 1966), followed by the Film Censorship Act 2002 (Act 620), which is still in force today (Malaysia, Ministry of Home Affairs 2012).

3) Decisions are made based on rules and criteria stipulated in three basic documents: the Film Censorship Act, Censorship Guidelines, and Specific Guidelines Censorship (Malaysia, Ministry of Home Affairs 2012).

4) Vietnam, Singapore, Laos, Myanmar, Brunei, and the Philippines also have media policies focused on censorship, due to their respective authoritarian governments (see Sen and Lee 2008; Slater 2010).