Contents>> Vol. 10, No. 1

Care Relations and Custody of Return-Migrant Children in Rural Vietnam: Cases in the Mekong Delta

Iwai Misaki*

*岩井美佐紀, Department of Asian Languages, Kanda University of International Studies, 1-4-1 Wakaba, Mihama-ku, Chiba 261-0016, Japan

e-mail: misakii[at]kanda.kuis.ac.jp

DOI: 10.20495/seas.10.1_33

In the Mekong Delta, Vietnam, there are a number of multiethnic children who are foreign nationals and have lived apart from their mothers for a long time. They were born in East Asian countries such as Taiwan and Korea and raised by their maternal relatives. This paper aims to examine the diverse experiences of return-migrant children and analyze care relations and custody over the children between absent mothers and maternal relatives, by exploring three cases obtained through my fieldwork. Absent mothers are divided into three types according to their marital status: (1) married women, (2) remarried women living in foreign countries, and (3) divorced women living apart from their children in Vietnam. In many cases they are unable to fulfill their duties or make decisions regarding their children’s welfare and interests since they live far away and are not always in touch with the children. Consequently, they are heavily dependent on their relatives. In place of absent mothers, foster parents—mainly grandparents or aunts who live together and take care of the children—try to maintain a legal and educational environment to ensure custody of the children. It is important to understand the difference between physical and legal custody, as well as two types of mothers: practical and biological.

Keywords: transnational marriage/divorce, multiethnic children, return migration, absent mothers, maternal relatives, custody, Mekong Delta

I Introduction

Since the 1990s, when Vietnam entered thời kỳ hội nhập quốc tế (the era of global integration), the Mekong Delta has been a major source of marriage migrants to Taiwan and South Korea (Phan An et al. 2005; Hugo and Nguyen Thi Hong Xoan 2007; Nguyen Xoan and Tran Xuyen 2010; Iwai 2013; Phạm Văn Bích and Iwai 2014a; 2014b). Many Vietnamese-born women have sent their children back to Vietnam after giving birth in these other countries. There are various reasons for this, including divorce (Cửu Long 2016; Le Hien Anh 2016; Văn Vĩnh 2016).

This paper focuses on return-migrant children who were born in foreign countries and sent to their maternal home to be raised. Who raises these children who spend a long time away from their mothers in childhood, and how does the relationship between the children and their new caregivers affect the children’s relationship with their absent mothers? Why do the mothers ask their relatives to raise their children? This study examines the meanings of children’s cross-border migration and the formation of transnational families. By exploring the social roles of maternal relatives, I aim to clarify the various aspects of care relations involved in child-rearing in rural Vietnam.

Several studies have discussed children left behind in their homes due to increasing cross-border labor migration. For example, research has shown that in the Philippines and Indonesia, where women often go abroad to work as domestic workers or caregivers, the children left behind are raised by aunts, grandmothers, or other relatives (Nagasaka 1998; 2009; Parreñas 2001; 2005; Ogaya 2016; Lam and Yeoh 2019). Arlie Hochschild (2000) regarded this phenomenon as the formation of “global chains of care” for child-rearing between two transnational families. However, there are not many prior studies on the return migration of multiethnic children from transnational marriages. In Thailand and Vietnam, where several women marry foreign men and later divorce, the mothers frequently send their children back to their home villages, asking their relatives to raise them (Ishii 2016, 125–127; Le Hien Anh 2016, 183). Only a few studies refer to the everyday lives and experiences of these children and the care arrangements between the mothers and their relatives.

Essentially, children’s relatively flexible mobility is a common feature of family relations in Southeast Asia. For example, if parents die or divorce or migrate for work to big cities, their children typically move between different households and are taken care of by consanguineal kin such as grandparents or aunts in rural areas (Kiso 2012, 473–476; 2019, 371–374; Sato 2012, 345–358).

Gerald Hickey (1964, 110–111) made similar observations about child-rearing in a rural village in the Mekong Delta area of southern Vietnam: (1) many children received much of their caregiving from older siblings or cousins who lived nearby, and (2) children could wander into neighbors’ houses without fear of being punished and were welcomed as if they were family members. According to A. Terry Rambo (2005), these flexible and wider family relations and higher mobility in the Mekong Delta reflect the characteristics of an open peasant community.

As the above-mentioned sources have shown, in Southeast Asia flexible care relations are woven by social networks and multiple ties based on kinship, and this social function may support and promote women’s labor migration both within and across national borders (Hayami 2012, 12–18). Janet Carsten (2000) has highlighted the distinction between social and biological aspects of kinship in bilateral societies such as Malays and suggested that it is helpful to understand “local cultures of relatedness” (Carsten 2000, 25–29). According to Carsten, relatedness is created both by ties of procreation and through everyday practices of feeding and living together in the house (Carsten 2000, 18). In addition, “relatedness” is deeply connected with the ethics of care. Carol Gilligan (2003) suggests that women as practitioners of care always consider who needs help and what relations are most important.

An important point in this study is the absence of the mothers of transnational families. How have children with foreign roots grown up in the absence of their mothers? How are the absent mothers able to fulfill their role as guardians? Here we focus on varied aspects of custody in the context of everyday practice in rural Vietnamese society.

II Methodology and Research Site

This discussion is based on the results of non-consecutive fieldwork conducted in Vi Thang commune in Hau Giang Province, Vietnam, which as of August and December 2017 and February 2019 had the second-highest number in the country of married migrant women from the Mekong Delta. This study is based on data about return-migrant children who were living in the commune as of December 2017. The December 2017 and February 2019 fieldwork collected supplemental information on the children.

Vi Thang is an agricultural commune located 200 km southwest of Ho Chi Minh City and 50 km southwest of Can Tho city center. As of April 2017 the commune had a population of 9,559 people, with 2,351 households residing in seven hamlets. Vi Thang was chosen because Vietnamese newspaper articles reported that elementary schools in the commune had accepted children without birth certificates as part of a humanitarian effort. These children attended classes as “non-members” (học gửi), meaning that they were not included on student lists and did not enjoy the same rights as their classmates (Hoài Thanh 2016; Ngọc Tài 2016; Văn Vĩnh 2016).

This study is based on observations and in-depth interviews with various stakeholders—including some returning migrant mothers, their children, and their relatives (e.g., parents and siblings)—conducted in 16 households. The perspectives of 18 return-migrant children are represented in the discussion.

In terms of methodology, for carrying out fieldwork I identified and obtained access to participants with the assistance of local organizations as well as schools. Prior to field research, I contacted executives of the Vietnamese Women’s Union (VWU) in Hau Giang Province and obtained general information concerning return-migrant children. The VWU provides legal support for international marriage and divorce matters. Full-time social workers belonging to the VWU attended each family interview visit, as they had a good grasp of the individual cases and were in a position to provide advice on legal procedures. All interviews were conducted with their cooperation. In addition, the vice-president of Vi Thuy District (former president of Vi Thang) and the present president of Vi Thang commune, both of whom knew the local situation well, assisted with interviews and family visits.

Because most mothers were absent, I managed to conduct interviews with only three mothers. Many of the mothers had left home for the big city. Consequently, the interviews were conducted mainly with the children’s grandparents or aunts (mothers’ sisters). Therefore, any information about the mothers must be viewed with caution, since it was provided by a variety of people who were likely to have different interests and views about marriage migration and the resulting children.

Return-migrant children in Vi Thang commune who were foreign nationals may be classified as living in three types of household:

Type 1, Two-parent transnational households: The children were born in foreign countries and migrated to Vietnam temporarily while their parents resided abroad and faced economic difficulties.

Type 2, Remarried mother transnational households: The children returned to Vietnam, while their divorced mothers lived in foreign countries and remarried foreign men.

Type 3, Single mother proximate households: The children were born in foreign countries and returned to Vietnam accompanied by their mothers following the latters’ divorce (or separation). The mothers temporarily cared for their children in proximity but eventually remigrated to work in larger cities, such as Ho Chi Minh City.

In each household type, mothers and children do not live in proximity to one another, thus challenging traditional gender notions of the family according to which women are responsible for overall family life (đảm đang), especially childcare and household budgeting (Lê Thị Nhâm Tuyết 1975; Pham Van Bich 1999, 38–39). The mothers support the family via regular remittances, while the children are raised by maternal relatives.

III Background of Return-Migrant Children in Rural Vietnam

III-1 From Foreign Brides to Mothers of Multiethnic Children

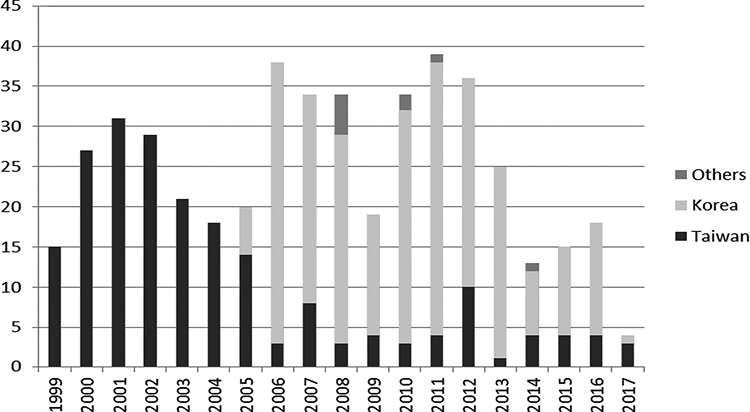

According to the results of the interview survey of Vi Thang commune members, the women who entered into transnational marriages had all arranged to meet foreign men through brokers in Ho Chi Minh City. Fig. 1 shows the number of transnationally married women from the commune. As shown in the figure, there were 470 married migrant women in the commune between 1999 and the end of April 2017. Of them, 255 were married to Koreans, 206 to Taiwanese, 7 to mainland Chinese, and 2 to Americans. The characteristics of marriage migration from the commune to foreign countries are similar to those of Vietnam as a whole. In short, before 2006 Taiwan was the most common destination for marriage migration, and after 2006 Korea became the most common destination, due to changes in Taiwanese immigration policies (Iwai 2013, 143–145). The commune’s government did not know the number of divorced migrant women.

Fig. 1 Women from Vi Thang Commune Married to Foreigners

Source: Created by author based on UBND xã Vị Thắng (2017).

The interviews revealed that three women had returned home during pregnancy and given birth there: one planned to return to Korea after childbirth, and two women who divorced after returning to Vietnam remigrated to Ho Chi Minh City after childbirth.

In what Nicole Constable (2005) calls the gendered geographies of power, poor and low-educated women who cannot achieve social or economic mobility in their own countries marry men from much more wealthy countries in order to fulfill two desires: to provide economic support for families back home and to change their own lives in their host countries (Constable 2005, 5–7; Lu and Yang 2010, 20–21). For example, Phung’s case is typical. Phung was born in 1989 and married a Korean man 16 years older than her through a group match party organized in Ho Chi Minh City in 2001. Phung decided to marry a foreign man because she wanted to help her parents economically, and her parents did not object. Phung’s mother explained, “My daughter told us that she wanted to help her poor parents who were facing difficulties. She intended to work and send remittances.” The image of the bride that came up in the interview with the parents was of a “daughter who has sacrificed for the family.”

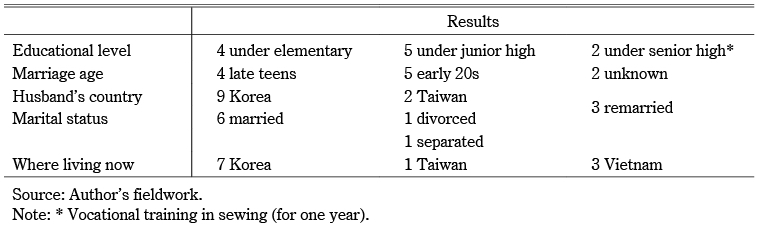

Table 1 presents personal information on the 11 internationally married women who lived away from their children.1)

As shown in Table 1, most of the women had married at a young age, four of them while still teenagers. In general, their educational level was quite low. This image of Vietnamese marriage migrants is consistent with that described by other researchers (Phan An et al. 2005; Hugo and Nguyen Thi Hong Xoan 2007; Nguyen Xoan and Tran Xuyen 2010; Le Hien Anh 2016). As for household types, six of the women continued in a marital relationship (type 1), one woman remarried in a foreign country (type 2), and four women remigrated to big cities (type 3).

Table 1 Characteristics of Absent Mothers Whose Multiethnic Children Returned and Are Living in Vi Thang Commune

The daughters’ motivations were not always in line with their parents’ thoughts. The results of the interviews with married immigrant women revealed their positive emotions, such as longing and hope for the unknown world, as expressed in statements such as the following: “I wanted to change my life,” “I wanted to expand my possibilities,” and “I wanted to get on the plane to go abroad” (Phạm Văn Bích and Iwai 2014a). These individual aspirations were followed by economic reasons, such as helping poor parents in rural Vietnam. Such positive attitudes and efforts on the part of the women have not been sufficiently identified in previous research.

III-2 The Role of Maternal Grandparents in Childbirth Support

The women’s fiduciary relationship with their biological families—which is maintained through remittances to their home countries—and their desire to have children who would give them future stability in their host countries are extremely important motivations for the women’s migration. In most cases, foreign brides obtain a status of residence on their spouse’s visa when they marry Taiwanese or Korean men. Most of them get pregnant and give birth within one year. After the children are born, the mother’s nationality position shifts. In other words, a mother with a biological citizen child is guaranteed legal status in the country. Therefore, the women often apply for naturalization from Vietnamese nationality to Taiwanese or Korean nationality, with the help of their husbands. In East Asian societies, where the birthrate is declining and the population is aging, especially in rural areas, there is strong pressure to give birth to a son. This is the main task of foreign brides, and not only they, but also their parents, are well aware of this.

For example, a pair of grandparents who are currently raising a Korean multiethnic grandson, Huyn, recalled the time before their daughter Phung gave birth to him, which was 10 years after her marriage. Until that pregnancy, her 10 years of infertility had worried her parents. Phung’s father recalled:

I brought some medicine to help my daughter become pregnant. Thanks to the medicine, my daughter was able to get pregnant six months later. We took care of her in Korea so that she could give birth safely. Having a child was important so that my daughter could live there in a stable way.

During Phung’s pregnancy both her parents went to Korea, where her mother stayed for eight months and her father for three. After some time back in Vietnam, the mother returned to Korea and looked after Huyn while Phung started to work. Eleven months later the mother returned to Vietnam with Huyn. Phung’s remittances from Korea helped her parents build a new house. In addition, her mother was able to earn an income by working illegally while staying in Korea.2)

Thus, Phung’s cross-border marriage brought about two turning points for her family of origin. First, producing children for her Korean husband’s family was her most essential role, by which she fulfilled her obligation as a daughter-in-law and established a stable legal position in the family. This was important, as until she gave birth to a child she was not allowed to work and earn money, which would have enabled her to send remittances to her family of origin in Vietnam.

Second, Huyn’s Vietnamese maternal grandparents are fully responsible for broader childcare, including pregnancy, childbirth, and child raising. That was why they provided Phung with fertility medication. In their eyes, it was natural for them to travel to Korea and care for their grandson while both of Huyn’s parents worked full-time, as well as to accept Huyn in their home in Vietnam. Such a situation often occurs when the husband’s parents are old or have passed away. Since Huyn “returned home” with his grandparents to Vietnam, Phung has been sending regular remittances to cover his food and other expenses. Child migration is thus a major factor for both families (the woman’s family of marriage in Korea as well as her family of origin in Vietnam) to acquire mutual assistance in their daily lives.

III-3 Characteristics of Multiethnic Children Who Returned to Vietnam

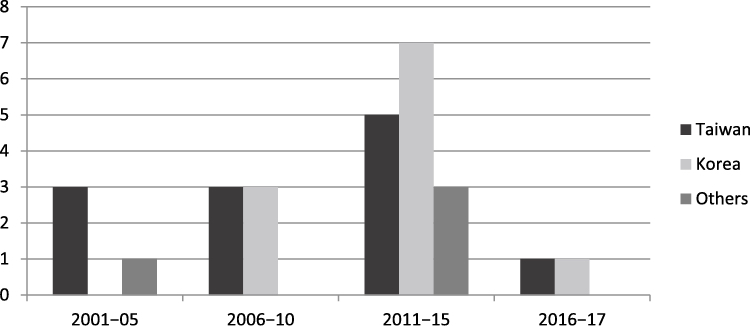

According to Vi Thang commune’s statistics, there were 27 children with foreign nationality in the commune as of April 2017: 11 Koreans, 12 Taiwanese, 1 mainland Chinese, 2 Malaysians, and 1 Vietnamese (Fig. 2). Clearly, there were a large number of children who returned to Vietnam during the period 2011–15.

Fig. 2 Return-Migrant Children with Temporary Resident Registration in Vi Thang Commune

Source: Created by author based on UBND xã Vị Thắng (2017).

However, this data does not reflect the actual number of multiethnic children living in the commune but indicates the time that return-migrant children were registered as temporary residents of the commune.3) According to the author’s fieldwork, with cooperation from the president of the VWU at the commune level, there were 18 multiethnic children living in the commune as of December 2017. The reason the numbers are different is that when some children left the commune, their maternal relatives did not notify the commune government. Of the 18 multiethnic children, 11 lived apart from their mothers. The other seven lived with their mothers in Vietnam.4)

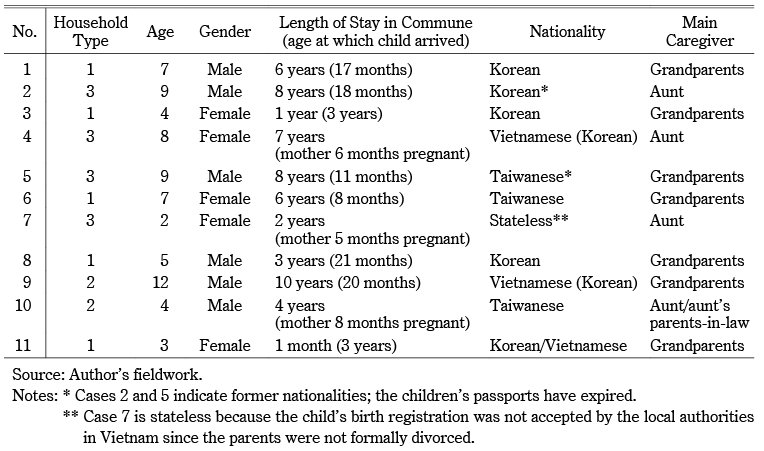

Table 2 presents the situation of the 11 multiethnic children who lived apart from their mothers.

First, by family type, five children lived apart from their two parents in foreign countries (type 1), two children’s mothers had remarried in foreign countries (type 2), and four children lived apart from their divorced/separated mothers after they returned to Vietnam (type 3).

Second, the majority of the children were students of elementary school age or younger. There was little difference in gender among the children: six boys and five girls.

Third, nearly all the children returned to Vietnam during their infancy—some while still lactating. Three of them returned to their mothers’ home before birth, and their mothers left for Korea or Ho Chi Minh City several months after giving birth. Indeed, the mothers discontinued breastfeeding after several months and lived apart from their children. In place of the mothers, the children’s maternal relatives—grandmothers and aunts—discharged the motherly duties.

Fourth, most of the 11 children were born and registered in their father’s country, thereby acquiring citizenship in that nation. Four of the children were Korean and three Taiwanese; among them, two were former Korean or Taiwanese nationals whose passports had expired long ago. Another child had dual nationality (Korean-Vietnamese). Of the two children with Vietnamese nationality, one returned from Korea to Vietnam in utero and was registered after her mother was divorced; the other was adopted by a maternal aunt in Ho Chi Minh City after returning from Korea at the age of 20 months.5) One girl was stateless: she was born in Vietnam, but her birth was not registered with the local authorities because the mother had not yet officially divorced her Korean husband.

Finally, all the children had been raised for many years by their maternal families (seven by grandparents and four by aunts). No children were raised by anybody else. Consequently, most of them attended school while in the care of their grandparents or aunts.

IV Child Raising and Maternal Family Relations in Rural Vietnam

As seen above, return-migrant children are raised by maternal relatives instead of absent mothers who are busy working and cannot afford to take care of their infants. Based on the interviews, the reasons for this situation are as follows:

1)Most of the mothers’ parents-in-law are quite old, so it is difficult for them to care for their grandchildren. Even when the parents-in-law agree to take care of their grandchildren, they require the couple to pay the high cost of childcare, which strains the couple’s family budget.

2)Childcare costs in Vietnam are much cheaper, and thus the financial burden on couples is reduced when maternal relatives care for the children. In southern Vietnamese society, there are many flexible arrangements for the raising of children by maternal relatives. This can be seen in Hickey’s description of the importance of consanguineal and non-kin groups who reside in proximate houses and share everyday practices of mutual aid (Hickey 1964, 93–96).

For these reasons, return-migrant children leave their parents, move across the border, and are raised by maternal relatives living in rural areas of Vietnam.

In the next subsections IV-1–IV-4, the child-rearing patterns around children whose mothers are absent and living separately will be examined in relation to the children’s intimate relationship with their maternal relatives.

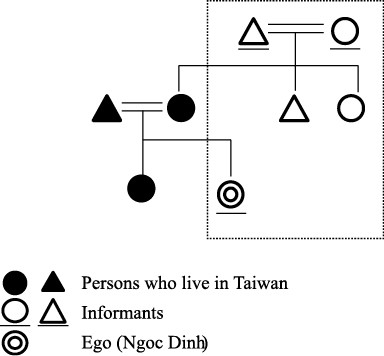

IV-1 The Case of Ngoc Dinh: Type 1

Ngoc Dinh, born in Taiwan in 2010, had been living with her maternal grandparents for six years, ever since she was eight months old. Her parents, who work full-time and live in Taiwan, cannot take care of her, so they have entrusted her maternal grandparents with her upbringing (Fig. 3 ). Ngoc Dinh’s sister had the same experience in that she spent several years in her maternal grandparents’ home before returning to Taiwan for elementary school. According to Ngoc Dinh’s grandmother, her daughter intends to take Ngoc Dinh back to Taiwan after she graduates from elementary school.

Fig. 3 Household Composition of Ngoc Dinh’s Family <Type 1>

Source: Based on author’s interview in 2017.

To the interview question “How are you in touch with your mother?” Ngoc Dinh answered, “I tell my mom what it was like today over the phone every night.” She looks forward to talking to her mother on a free VoIP phone call at 6 p.m. every day. Ngoc Dinh continued, “I don’t talk with my father because he cannot understand Vietnamese. My sister can speak Chinese, but she speaks Vietnamese well.”

Ngoc Dinh has visited Taiwan a couple of times during her six years living in Vietnam, but always with her grandmother. When her grandmother returned to Vietnam, she preferred to go with her rather than remain in Taiwan.

In response to the interview question “What do you want to do in the future?” Ngoc Dinh said, “I want to live in Vietnam forever. I can’t imagine living away from my grandparents. My grandma says that my mouth and nose look exactly like my mom’s.”

Having lived in Vietnam for six years, Ngoc Dinh is completely comfortable with her life there with her grandparents. She feels happy to be like her mother, but she has noticed a certain emotional distance from her father, who cannot communicate in Vietnamese.

With regard to the grandparents’ experience of this situation, the grandmother shared that Ngoc Dinh’s sister had also been entrusted to them from the age of 14 months to six years. In this way, through the experience of raising two granddaughters, the grandparents seemed to once again enjoy “parenting.” The grandmother commented:

My granddaughter likes Taiwan, but just to go sightseeing. When we returned to Vietnam, she didn’t want to stay in Taiwan but returned with us. She is very close to her friends, and nobody knows that she is a multiethnic child, between Vietnam and Taiwan.

Ngoc Dinh attends elementary school informally. Local schools allow children to enroll formally as long as a birth certificate is submitted before graduation. Ngoc Dinh’s grandparents want to get her birth certificate from Taiwan so that she can officially enroll at school, but her mother has not sent it. Ngoc Dinh showed us many award certificates given by the school and remarked that her favorite subject was Vietnamese and that she wanted to become a teacher.

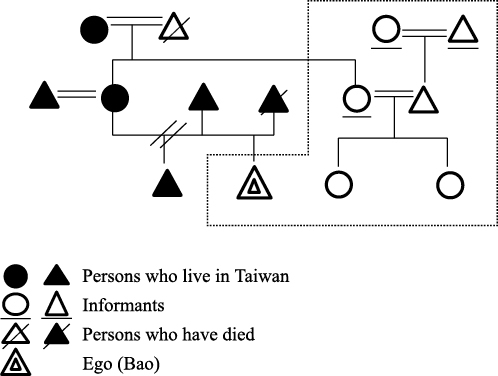

IV-2 The Case of Bao: Type 2

Bao was born in 2013. His mother is Vietnamese and father Taiwanese. His mother returned to Vietnam eight months pregnant and gave birth to Bao there. Several months later his mother, who was already naturalized as a Taiwanese national, returned to Taiwan alone, without Bao.

As shown in Fig. 4 , Bao now lives with his maternal aunt’s family, which includes the aunt, her husband, two daughters, and the aunt’s parents-in-law. Aunt Dam is raising her nephew Bao along with her own two young daughters. According to Dam, her husband loves Bao deeply as his own son, and so do her parents-in-law. Dam’s parents-in-law take the responsibility of dropping and picking up Bao by bike every day from kindergarten. Bao, like his cousins, calls his aunt “mother,” his aunt’s husband “father,” and his aunt’s parents-in-law “grandpa” and “grandma.” Although the grandparents are not blood relatives but affinal kin, they do not distinguish Bao from their granddaughters.

Bao’s mother resides in a small city in Taiwan. She has been married three times, and Bao is from her second husband, who died before she gave birth. She also has a child from her first marriage, and she now lives with that child. After her second husband died, she returned to Vietnam while pregnant and gave birth to Bao. After several months she returned to Taiwan, and Bao was left behind to live in his aunt’s home.

The reason Bao was entrusted to his aunt was that Bao’s maternal grandmother, who was also in Taiwan, was unable to look after him because she was working illegally. A few years ago, Bao’s mother remarried a Taiwanese man and had a child with him. Bao’s grandmother helps to take care of that child in Taiwan. According to Dam, the mother wants to take Bao back to Taiwan in a few years.

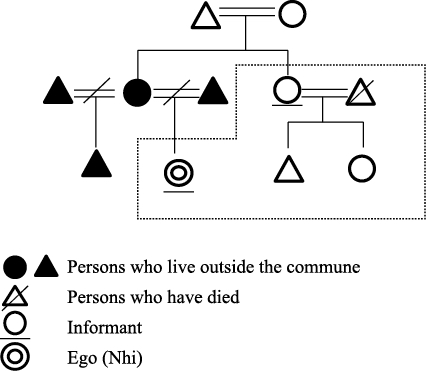

IV-3 The Case of Nhi: Type 3

In this subsection we examine the case of a child in a family with an absent single mother (type 3). Nhi was born in Vietnam in 2009 and was in the third grade at the time of the interview. Nhi has family registration in her maternal grandfather’s hamlet, although she lives in another hamlet with her maternal aunt’s family. Thus, her nationality is Vietnamese.

Nhi’s mother moved from Korea to Vietnam while six months pregnant and gave birth in Vietnam. She decided to separate from her husband because of his repeated domestic violence, his extremely sloppy behavior, and his disapproval of her work. About a year after their separation, she was officially divorced. The Korean father knew of Nhi’s birth and visited her one year later.

Nhi’s mother went to work in Ho Chi Minh City eight months after giving birth, and since then Aunt Muoi has taken care of Nhi on behalf of her mother (Fig. 5). Nhi calls both her aunt and birth mother “mother.” She distinguishes the two mothers as “má mập” (fat mom) (aunt) and “má ốm” (thin mom) (biological mother). Neighbors believe that Nhi is Muoi’s biological daughter, and Muoi has not attempted to clear up this misunderstanding. Her husband also loves Nhi as his own child. Muoi recently started taking Nhi to free Korean language lessons organized every weekend by the Korea Center for United Nations Human Rights Policy (KOCUN).6) However, since it is a one-hour bike ride from the commune to Can Tho city, Nhi stopped going.

A couple of years ago Nhi’s mother remarried a Vietnamese man who worked in the same factory in Ho Chi Minh City, and they had a son. However, they are now divorced and Nhi’s mother is raising the boy on her own. Nhi sometimes visits her mother and younger half-brother in Ho Chi Minh City, but after a few days Muoi calls and urges Nhi to return home. Nhi’s Korean father says that he wants to take her to Korea when she is 18, and until then he wants Muoi to raise her. However, he has never paid any child support. In August 2017 I encountered the father while he was looking to remarry in the hamlet. Later, he stayed at Muoi’s house and ate meals there, but he said that he did not need to pay any money while there.

IV-4 Relatedness and Custody of Multiethnic Children Who Live Apart from Their Mothers

We will now consider the relations between multiethnic children with foreign roots and their guardians. In particular, we will examine the guardians’ strong attachment to the children in terms of custody.

In the case of Ngoc Dinh, the grandparents want to support their daughter by providing for their granddaughter what they did not give their own children when they were young and hardworking. They are very proud of their grandchild being awarded certificates at school and seem to be very happy with her growth. In the case of type 1 families, where the parents or remarried mothers regularly send remittances to the grandparents, it is sufficient for grandparents to focus their attention on their grandchildren’s education.

Meanwhile, in the relationship between the aunts and their nephews and nieces, without exception the children call their aunt “mum,” and it is clear that a deeply intimate relationship has been built between them (type 2 and type 3). In the case of Bao, his aunt did not hesitate to take her nephew home and raise him like her daughters. And Dam’s parents-in-law seem to be happy with Bao, probably because Dam and her husband have no son of their own. Nhi’s aunt Muoi loves her so much that sometimes her own children complain, “Mom loves Nhi most.” Muoi feels sorry for Nhi and feels that only she can protect her.

On the whole, the foster parents actively participate in the everyday care and education of their grandchildren, nieces, and nephews. Ngoc Dinh’s grandparents and Nhi’s aunt want to expose the children to greater opportunities and improve their prospects for the future. For example, Muoi took Nhi to KOCUN’s Korean classes every weekend after KOCUN staff visited Nhi, enthusiastically encouraged her to study Korean, and provided financial assistance. In rural situations, which are far removed from the foreign cultures of the parents, it seems that foster parents feel responsible for improving the children’s prospects, including linking them with their foreign roots (e.g., helping Nhi learn Korean). In addition, in place of the absent mothers, they visit the judicial branch of Hau Giang Province once every three or six months to renew the children’s residency status while renewing their visa. The foster parents also have the responsibility of securing the children’s right to reside by submitting “temporary registrations” to the local government.

The children say that they want to continue living with their grandmothers or aunts because they regard their homes as their own. Most of them moved to Vietnam during infancy (sometimes in the mother’s womb) and have grown up in their foster parents’ home. Meanwhile, the circumstances surrounding them have sometimes changed dramatically, such as the remarriage of their mothers who are living separately. Because of these changing circumstances and an uncertain future, the children adopt the important survival strategy of strengthening their relationships with unmarried uncles, aunts, and cousins in their foster families.

Finally, how are the absent mothers involved? Generally, whether living in a foreign country or in a large city, they try to maintain an intimate relationship with their children by talking daily over the Internet. Most of the absent mothers assume that the separation from their children and care by their relatives are temporary and that they will live with their children again once conditions are favorable. Therefore, some mothers think they do not need to send the formal documents necessary for school enrollment, such as birth certificate. In addition, as in the cases of Nhi and Bao, the remarriage of the mothers can complicate the domestic environment and make it difficult to integrate return-migrant children into their new families. Therefore, the long-term stay of the children in rural Vietnam is due largely to the changing circumstances of the absent mothers.

V Conclusion

My investigation shows that Vietnamese families in the Mekong Delta are not rigid structures but flexible circles that openly extend their kin networks across the border. They are willing to be flexible in care relations. Common to the three types of household described above is the prevalence of “relatedness,” in which multiethnic children are growing up through the everyday practice of living with their maternal relatives away from their biological parents.

In this study I have sought to elucidate the life experiences of return-migrant children who live apart from their mothers, and their relationship with their absent mothers and maternal relatives. In particular, I have attempted to highlight the role of maternal relatives (mainly grandparents or aunts) taking the place of absent mothers in providing care to children experiencing cross-household migration.

I have identified the situation of the main members in transnational families as follows:

• Mothers live separately from their children mainly due to economic difficulties. Most of them are factory workers who are busy working all day and do not receive enough social welfare. They send regular remittances to their relatives whom they entrust with childcare.

• Children return to Vietnam when they are quite young, sometimes even while in their mother’s womb. They attend local schools when they reach school age, but the plan is for them to return eventually to their father’s countries.

• The foster parents, who are in their mid-40s to 60s, are more experienced socially and in parenting than the absent mothers. They seem to be trying to create the best conditions for their foster children and to be actively involved in their future education.

In summing up the plural care relations among the children, absent mothers, and maternal relatives, some features can be observed.

First, the relationship between the multiethnic children and their foster parents: The children are raised in a wide and flexible family circle as members of the maternal family. In the southern part of Vietnam, it is common for maternal grandparents to take care of their grandchildren in place of absent mothers, and this custom prevails even in the case of cross-border marriage and divorce. Basically, foster parents are awarded custody guardianship based on two domains: (1) practical domain: living together with the children and providing care and safety, and (2) legal domain: guaranteeing a temporary residence, enrolling the children in local schools, and applying for visa renewal at the Hau Giang Provincial Justice Bureau every three or six months. In these aspects they genuinely care about the well-being of the children and voluntarily contribute toward child custody although they have no legal obligation. Most foster parents have a strong attachment to the children and take responsibility for them so that they continuously guarantee custody.

Second, the relationship between foster parents and absent mothers: Grandparents and aunts stand in as a substitute for the children’s parents in exchange for financial support from the mothers. This exchange is not merely a payment for services but also a form of division of labor among family members (e.g., between parents and daughters or between sisters). In addition, maternal relatives are deeply involved in broader “childcare,” including pregnancy and childbirth, as seen in the case of Huyn’s grandparents. The purpose of the remittances is clearly not to provide mainstay support, but rather to affirm membership in a family circle and its continuity. In other words, the children’s return migration promotes the feeling of mutual aid and cooperation among transnational family members. In addition, there are cases in which the paternal grandparents in foreign countries are too old, are too ill, or live too far away to look after their grandchildren.

Third, the relationship between the children and their absent mothers: As shown through concrete cases, mothers who live apart from their children find it extremely difficult to take care of their children and educate them. However, they miss sharing directly in their children’s school experiences. They see their children only when they return to their home of origin, perhaps once a year. Otherwise, based on the mothers’ schedules, they set up a chat time with their children, such as “every day, 30 minutes after dinner,” via VoIP phone calls.

As de jure guardians, the biological parents or divorced mothers are obliged to advocate for the best interests of their children. Responsibility for legal proceedings rests with the mothers. However, the mothers are de facto not able to fulfill their duties and make all decisions regarding their child’s welfare and interests since they live far away and are not always in touch with the children. Consequently, they are heavily dependent on their relatives back home. Without a flexible family relationship that transnationally supports mutual aid, global care relations cannot be established. In other words, it is important to understand the difference between physical and legal custody, as well as the two types of mothers: practical and biological.

Accepted: June 4, 2020

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by Institute of Developing Economies IDE-JETRO under Grant # FY2016/2018 Research Topic C-06: Dynamics and Transformation of the Vietnamese Family in the Doi Moi Era.

References

Carsten, Janet. 2000. Introduction: Cultures of Relatedness. In Culture of Relatedness: New Approaches to the Study of Kinship, edited by Janet Carsten, pp. 1–36. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Constable, Nicole, ed. 2005. Cross-border Marriages: Gender and Mobility in Transnational Asia. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Cửu Long. 2016. Nhiều cô dâu miền tây tháo chạy khỏi chồng ngoại [Many brides of Mekong delta origin run away from foreign husbands]. VN Express. October 4. https://vnexpress.net/nhieu-co-dau-mien-tay-thao-chay-khoi-chong-ngoai-3413294.html, accessed November 15, 2017.

Gilligan, Carol. 2003. In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Hayami Yoko 速水洋子. 2019. Tonan Ajia ni okeru kea no senzairyoku: Sei no tsunagari no jissen 東南アジアにおけるケアの潜在力―生のつながりの実践 [Potentialities of care in Southeast Asia: Practice of life’s connectivities]. Kyoto: Kyoto University Press.

―. 2012. Introduction: The Family in Flux in Southeast Asia. In The Family in Flux in Southeast Asia: Institution, Ideology, Practice, edited by Hayami Yoko, Koizumi Junko, Chalidaporn Songsamphan, and Ratana Tosakul, pp. 1–26. Kyoto: Kyoto University Press; Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books.

Hickey, Gerald C. 1964. Village in Vietnam. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Hoài Thanh. 2016. Chuyện ‘học gửi’ của những đứa con lai [Stories about “audit study” of some mixed-race children]. Vietnamnet. October 7. http://vietnamnet.vn/vn/giao-duc/goc-phu-huynh/chuyen-hoc-gui-cua-nhung-dua-con-lai-o-truong-lang-332614.html, accessed October 20, 2017.

Hochschild, Arlie Russell. 2000. Global Care Chains and Emotional Surplus Value. In On the Edge: Living with Global Capitalism, edited by Will Hutton and Anthony Giddens, pp. 130–146. London: Vintage.

Hugo, Graeme; and Nguyen Thi Hong Xoan. 2007. Marriage Migration between Vietnam and Taiwan: A View from Vietnam. In Watering the Neighbour’s Garden: The Growing Demographic Female Deficit in Asia, edited by Isabelle Attané and Christophe Z. Guilmoto, pp. 365–391. Paris: Committee for International Cooperation in National Research in Demography.

Ishii Sari K. 2016. Child Return Migration from Japan to Thailand. In Marriage Migration in Asia: Emerging Minorities at the Frontiers of Nation-States, edited by Ishii Sari K., pp. 118–134. Singapore: NUS Press in association with Kyoto University Press.

Iwai Misaki. 2013. Global Householding between Rural Vietnam and Taiwan. In Dynamics of Marriage Migration in Asia, edited by Ishii Kayoko, pp. 139–162. Tokyo: Research Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies.

Kiso Keiko 木曽恵子. 2019. Kea no ninaite no fukusuusei to sumatofon ni yoru oyakokankei no hokan: Syoushika jidai no Tohoku Tai nouson ni okeru kosodate ケアの担い手の複数性とスマートフォンによる親子関係の補完―少子化時代の東北タイ農村における子育て [Multiple caregivers and complementing parent-child relationship with smartphones: Child-rearing in northeastern rural Thailand in the era of declining birthrate]. In Tonan Ajia ni okeru kea no senzairyoku: Sei no tsunagari no jissen 東南アジアにおけるケアの潜在力―生のつながりの実践 [Potentialities of care in Southeast Asia: Practice of life’s connectivities], edited by Hayami Yoko 速水洋子, pp. 353–377. Kyoto: Kyoto University Press.

―. 2012. Women’s Labor Migration and “Multiple Mothering” in Northeast Thailand. In The Family in Flux in Southeast Asia: Institution, Ideology, Practice, edited by Hayami Yoko, Koizumi Junko, Chalidaporn Songsamphan, and Ratana Tosakul, pp. 463–482. Kyoto: Kyoto University Press; Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books.

Lam, Theodora; and Yeoh, Brenda S. A. 2019. Parental Migration and Disruptions in Everyday Life: Reactions of Left-Behind Children in Southeast Asia. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45(16): 3085–3104.

Le Hien Anh. 2016. Lives of Mixed Vietnamese-Korean Children in Vietnam. In Marriage Migration in Asia: Emerging Minorities at the Frontiers of Nation-States, edited by Ishii Sari K., pp. 175–186. Singapore: NUS Press in association with Kyoto University Press.

Lê Thị Nhâm Tuyết. 1975. Phụ Nữ Việt Nam qua các thời đại [Vietnamese women through the ages]. Hà Nội: Nhà xuất bản khoa học xã hội.

Lu, Melody Chia-Wen; and Yang Wen-Shan. 2010. Introduction. In Asian Cross-border Marriage Migration: Demographic Patterns and Social Issues, edited by Yang Wen-Shan and Melody Chia-Wen Lu, pp. 15–29. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Nagasaka Itaru 長坂格. 2009. Kokkyo o koeru Fuiripin murabito no minzokushi: Toransunashonarizumu no jinruigaku 国境を越えるフィリピン村人の民族誌―トランスナショナリズムの人類学 [Ethnography of Filipino villagers crossing the borders: The anthropology of transnationalism]. Tokyo: Akashi Shoten.

―. 1998. Kinship Networks and Child Fostering in Labor Migration from Ilocos, Philippines to Italy. Asian and Pacific Migration Journal 7(1): 67–92.

Ngô Thị Vân Phượng. 2018. Giới thiệu tình hình tư vấn và các trường hợp cụ thể tại KOCUN Cần Thơ [Introduction in consulting situation and particular cases in KOCUN, Can Tho city]. Paper presented at the conference “Hội thảo thực trạng và giải pháp hỗ trợ phụ nữ hồi hương và trẻ em Việt-Hàn cư trú tại Việt Nam” [Conference on the situation and solutions to support returning women and Vietnamese-Korean children who are living in Vietnam], January 25, Can Tho city, pp. 110–124. Cần Thơ: KOCUN.

Ngọc Tài. 2016. Chuyện học ‘gửi’ ở làng ngoại kiều [Stories of “audit learning” related to cross-border marriages in some villages]. Tuổi Trẻ. December 1. https://tuoitre.vn/chuyen-hoc-gui-o-lang-ngoai-kieu-1228285.htm, accessed October 10, 2017.

Nguyen Xoan; and Tran Xuyen. 2010. Vietnamese-Taiwanese Marriages. In Asian Cross-border Marriage Migration: Demographic Patterns and Social Issues, edited by Yang Wen-Shan and Melody Chia-Wen Lu, pp. 157–178. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Ogaya Chiho 小ヶ谷千穂. 2016. Ido o ikiru: Fuiripin ijyu jyosei to fukusu no mobiritei 移動を生きる―フィリピン移住女性と複数のモビリティ [Living in motion: Filipino migrant women and their multiple mobilities]. Tokyo: Yushindo.

Parreñas, Rhacel Salazar. 2005. Children of Global Migration: Transnational Families and Gendered Woes. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

―. 2001. Servants of Globalization: Women, Migration and Domestic Work. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Pham Van Bich. 1999. The Vietnamese Family in Change: The Case of the Red River Delta. Surrey: Curzon.

Phạm Văn Bích; and Iwai Misaki. 2014a. Cô dâu Việt Nam thành công ở Đài Loan: Hai nghiên cứu trường hợp [Successful Vietnamese brides in Taiwan: Two case studies]. Nghiên cứu gia đình và giới [Journal of family and gender studies] 24(1): 43–53.

―. 2014b. Cô dâu Việt Nam thành công ở Đài Loan: Hai nghiên cứu trường hợp [Successful Vietnamese brides in Taiwan: Two case studies]. Nghiên cứu gia đình và giới [Journal of family and gender studies] 24(2): 28–43.

Phan An; Phan Quang Thịnh; and Nguyễn Quới. 2005. Hiện tượng phụ nữ Việt Nam lấy chồng Đài Loan [Phenomenon of Vietnamese women married to Taiwanese husbands]. Thành Phố Hồ Chí Minh: Nhà xuất bản trẻ.

Rambo, A. Terry. 2005. Searching for Vietnam: Selected Writings on Vietnamese Culture and Society. Kyoto: Kyoto University Press; Melbourne: Trans Pacific Press.

Sato Nao. 2012. Mutual Assistance through Children’s Interhousehold Mobility in Rural Cambodia. In The Family in Flux in Southeast Asia: Institution, Ideology, Practice, edited by Hayami Yoko, Koizumi Junko, Chalidaporn Songsamphan, and Ratana Tosakul, pp. 339–364. Kyoto: Kyoto University Press; Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books.

UBND xã Vị Thắng [People’s Committee of Vi Thang Commune]. 2017. Báo cáo tình hình thực hiện công tác bình đẳng giới và hôn nhân gia đình trên địa bàn xã Vị Thắng [Vi Thang commune people’s report on the implementation of gender equality and marital and family issues at Vi Thang commune]. Unpublished annual report.

Văn Vĩnh. 2016. Hỗ trợ cô dâu Việt và con lai hồi hương [Supporting Vietnamese brides and their mixed-race children who returned home]. Công An Việt Nam. October 28. http://cand.com.vn/doi-song/Ho-tro-co-dau-Viet-va-con-lai-hoi-huong-414358/, accessed October 10, 2017.

1) There were 16 internationally married women whose children returned to Vietnam. Of the 16 mothers, five lived with their children in a home commune, two were divorced or separated, and three women continued in a marital relationship but stayed in Vietnam (two of them stayed temporarily to give birth and returned to Korea with their children by December 2017).

2) The grandmother worked for a few months at an automobile factory, but she was caught by the police and deported. As her penalty, she would not be allowed into Korea again for five years.

3) The commune government totaled the number of children whose relatives applied for the children’s temporary resident registration status in accordance with the security rules.

4) Of the seven children who lived with their mothers, four cases involved two sisters married to Taiwanese and Korean men.

5) The survey revealed that the data collected by the commune government did not include one of the two Vietnamese-Korean children with Vietnamese nationality.

6) KOCUN is a South Korean NGO responsible for supporting divorced or separated women and their children. In Can Tho city, Korean and Vietnamese full-time staff advise divorced and separated women and provide support for their vocational training as well as their multiethnic children’s legal issues (Ngô Thị Vân Phượng 2018, 110–113).