Contents>> Vol. 10, No. 2

From Governing to Selling Tourism: Changing Role of Local Government in the Tourism Development of Bohol, Philippines

Carl Milos R. Bulilan*

*Holy Name University, Tagbilaran City, Bohol, Philippines

e-mail: cmbulilan[at]hnu.edu.ph

DOI: 10.20495/seas.10.2_273

Tourism is a major global industry. Governments in developing countries have developed tourism as a means for economic progress. The role of the government is crucial in making tourism beneficial for local people. The traditional functions of government involve crafting legislation and regulating tourist activities in local destinations. The business and marketing aspects of tourism are often entrusted to the private sector. Today, local governments are directly involved in the tourism business. The traditional functions of governments have expanded into managing and marketing touristic enterprises and forming partnerships with private and government agencies, nongovernmental organizations, and host communities. This study aims to examine how local government units (LGUs) perform both political and entrepreneurial functions in tourism development. In particular, it explores the case of the province of Bohol—a model for tourism development in the Philippines. The Bohol LGU demonstrates how the local government can integrate governance, coordination, and doing business through tourism. This case study attempts to offer useful insights on formulating policies in local tourism development.

Keywords: governance, local tourism, tourism development, tourism business, public-private partnership, policy making, local politics

Introduction

Tourism has become one of the biggest global industries (Hitchcock et al. 1993; McIntosh and Goeldner 1986; United Nations Steering Committee on Tourism for Development 2011; Vanhove 1997; UNWTO 2015). As a top worldwide export category, it has surpassed automotive products and food (UNWTO 2017, 6). Tourism activities affect the economic, social, political, and environmental components of host countries and communities more than traditional industries do (Crick 1989; Eadington and Smith 1992; Long 1992; Murphy 1985). Management plays a crucial role in the way tourism contributes to local economic, social, and environmental sustainability (Edgell et al. 2008; Jamal and Getz 1995). Private businesses carry out the task of managing tourism and controlling the development of destinations. Multinational corporations operate hotels, resorts, tours, and transport services with minimal government intervention.

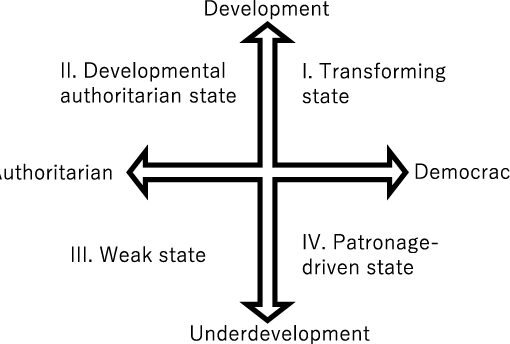

Entrepreneurial local government units (LGUs) have become a trend in the Philippines. Aser Javier (2002) argues that public entrepreneurship among LGUs has become a strategy to decentralize the political process. This new movement is contextualized within the Philippine Local Government Code of 1991, which empowers LGUs to engage actively in corporate activities to increase their local revenue contributions (RA 7160). This new trend raises important questions on the role of the government in tourism development (Philippine Statistics Authority 2017). It raises the question of how LGUs can simultaneously carry out governance and do business. With their political advantage, are LGUs more effective than their private counterparts in managing tourism and delivering its benefits to communities?

Using the case of the tourism industry in Bohol, this study examines how LGUs perform both political and entrepreneurial functions in tourism development. First, this study examines how LGUs exercise their traditional political roles and leadership in developing tourism in the province. Second, it presents the municipality of Danao, Bohol, as a model of how traditional governance and doing business can work together in tourism. This study highlights how partnerships, collaborative actions, and leadership enable the growth of an inclusive tourism development.

This study employs qualitative case study methods. In gathering data, I used in-depth interviews with key informants and focus group discussions. Informants were selected through purposive sampling based on their knowledge of the topic and their authority regarding the issues at hand. Informants included provincial development and provincial tourism office heads, the municipal mayor, municipal development and tourism staff, local people, and tour operators. Gathering of data and fieldwork were conducted within a year. To triangulate data gathered from the interviews, I also used primary and secondary documents and literature. I gathered official documents from the provincial and municipal offices, including statistics, legislative papers, development plans, accounting and financial reports, and local narratives written by local people. Official data from government agencies were also analyzed.

I Overview of Tourism in Bohol

The province of Bohol lies in the Visayan archipelago in the Philippines. It is the 10th-largest island in the country, with a land area of 4,821 square kilometers. By January 2018, it had a population of 1,255,128 people scattered among its 47 municipalities and the city of Tagbilaran (Philippine Statistics Authority 2018). From being one of the poorest provinces, Bohol has become a first-class province (income class) and one of the most dynamic in the country. From being a hotbed of political insurgency, it has become a leading tourist destination. Tourism has become one of the socioeconomic drivers in the province, with growing tourist arrivals and tourism-related businesses.

Bohol is one of the top tourist destinations in the Philippines. With the economic benefits that accompany the arrival of visitors, tourism has become one of the biggest industries in the province. It is considered a means for alleviating poverty, generating employment, and developing social infrastructures.

The province’s tourist resources are based on its natural features, cultural practices, and heritage structures. Its natural features include white beaches, marine life, forests, animals, waterfalls and rivers, hills and mountains, caves, and “adventure parks.” Musical performances and native dances, religious and historical festivals, and local handicrafts comprise its cultural attractions. Closely connected with Boholano culture and history are the province’s heritage structures.

This section provides a general background of Bohol tourism. First, it presents a statistical overview of the touristic movement. Second, it examines both nature- and culture-based tourist resources in the province. Finally, it surveys Bohol’s public and private facilities that make travel convenient and safe. This overview demonstrates how the local habitat, history, heritage, and hospitality have become the main resources for tourism and how government support facilitates the growth of the industry.

I-1 Tourist Arrivals

The number of tourists continues to grow in Bohol. According to a report shared by the Bohol Tourism Office (BTO) from the Department of Tourism Region VII (2016), in November 2016 there were 820,640 tourist arrivals in the province. This number was 36.26 percent higher than the year before, with an average annual growth of 28.5 percent over the past three years. After the great Bohol earthquake in 2013, tourists continued to visit despite fears of another earthquake and the damage to infrastructure and tourism facilities.

Tourists in Bohol are both local and foreign. In 2016 the BTO identified 585,316 (71.32 percent of the total number of tourists that year) as local tourists, 233,736 (28.48 percent) as foreign nationals, and 1,588 (0.19 percent) as overseas Filipinos. Among the foreign tourists, the largest number came from China (59,289), followed by Korea (39,229), the United States (20,317), and France (11,690). A significant number of tourists came also from Japan, Germany, and Taiwan. The BTO and the Department of Tourism (DOT) projected 1,226,574 tourists in the province in 2012 and the operation of the new airport in Panglao Island by 2018. Airlines began operating at the airport in 2019, with flights being limited to domestic destinations for the moment. Tagbilaran Airport was closed when Bohol-Panglao International Airport began to operate.

Among the tourist destinations in Bohol, Panglao Island had the largest number of visitors. From January to November 2016, a total of 366,174 tourists visited the island municipality. The provincial capital, Tagbilaran City, had 105,885 visitors, followed by Dauis, which had 25,914. Since most of the tourist facilities (such as the airport and pier) and tourist accommodations (such as hotels and resorts) are in these areas, it is not surprising that the largest numbers of tourists are found in these municipalities. Tourists visit destinations in other municipalities for sightseeing and other activities, without staying there overnight.

I-2 Touristic Products and Activities

Nature-Based Tourism

The natural environment is one of the main features of the tourism industry (Fennell 2008; Holden 2008; Hunter and Green 1995; Krippendorf 1982). It is “crucial to the attractiveness of almost all travel destinations and recreation areas . . . provide an important ‘backdrop’ to commercial service areas and recreation sites, or at least contribute to all tourist locations” (Farrell and Runyan 1991, 26). “Nature-based tourism” refers to

tourism in natural settings (e.g., adventure tourism), tourism that focuses on specific elements of the natural environment (e.g., safari and wildlife tourism, nature tourism, marine tourism), and tourism that is developed in order to conserve or protect natural areas (e.g., ecotourism, national parks). (Hall and Boyd 2005, 3)

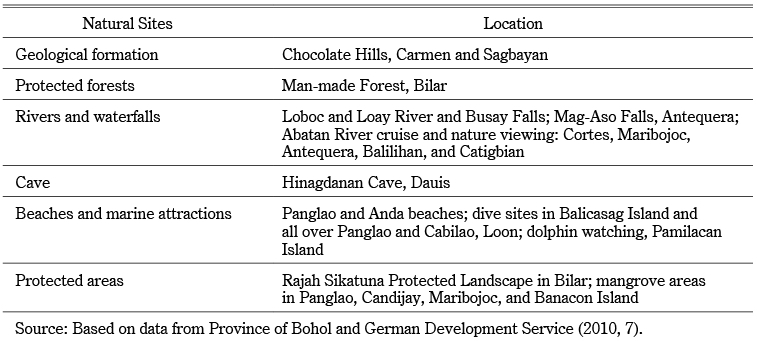

The Bohol provincial government has enumerated the natural assets that have been developed as tourist attractions (see Table 1).

Table 1 Nature-Based Tourism Resources in Bohol

Source: Based on data from Province of Bohol and German Development Service (2010, 7).

One advantage of traveling around Bohol is the close proximity of tourist sites. For example, in one day tourists can visit the Chocolate Hills, Man-made Forest, Loboc River, Panglao beaches, Hinagdanan Cave, and Rajah Sikatuna Protected Landscape (as a side trip). These spots are accessible through a well-cemented/asphalt 120-kilometer national highway. Located in the mid-southwestern part of the province, the Tarsier Sanctuary and Mag-Aso Falls in the towns of Corella and Antequera can be covered in a single trip. The Abatan River and mangrove plantations in the towns of Cortes and Maribojoc are two neighboring areas.

White beaches in the town of Anda and the mangrove plantation in the town of Candijay lie in the eastern part of Bohol. The islands of Pamilacan and Balicasag are located 15 kilometers from each other on the Bohol Sea and are accessible by boat from Panglao and Baclayon ports. However, lying in the Cebu Strait, north of Bohol, Banacon Island’s mangrove forest is a little farther from the rest of Bohol’s tourist attractions.

Culture-Based Tourism

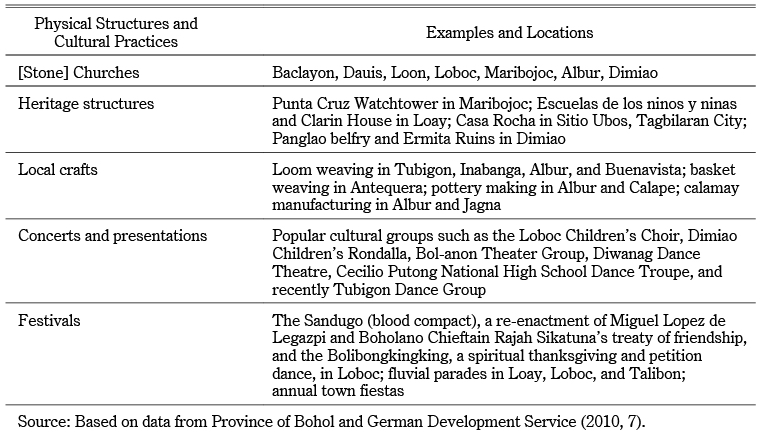

Culture is “a deeply embedded aspect of tourism” (George et al. 2009, 5). Traditional practices and customs of host communities have become tourist attractions. In Bohol, cultural traditions are evident in their physical and intangible forms. Physical and artistic expressions include old religious buildings, Spanish structures, ancestral houses, music, traditional dances, religious and historical festivals, handicrafts, and delicacies. Aside from these manifestations, Boholanos are known for their tradition of hospitality and friendliness toward visitors. The provincial government of Bohol enumerates specific cultural and historical assets that are of touristic value (see Table 2).

Table 2 Culture-Based Tourism Resources in Bohol

Source: Based on data from Province of Bohol and German Development Service (2010, 7).

Old Spanish-period structures are included in tourist routes. These include stone churches dating back to the early Spanish colonization of Bohol. Almost each of the province’s 47 municipalities has its own old church strategically built within the town center plaza, where the municipal government building is also located. These church buildings with bell towers mostly have baroque designs made of coral brick and hardwood.

Some of Bohol’s heritage structures were destroyed by fire or natural disasters. The great Bohol earthquake of 2013 destroyed many historic buildings, including the churches of Loon and Loboc towns. Some have been totally restored or are undergoing restoration. Modern reconstruction also caused the degradation of some of these churches. Other heritage structures include ancient watchtowers and century-old houses that tourists can visit.

Aside from ancient buildings, Bohol is known also for its musical traditions. Talented Boholanos have caught the attention of tourists and international musicians. One of the best-known musical groups in the province is the Loboc Children’s Choir. The choir is composed of elementary and high school students from the town of Loboc carefully selected by their teachers. The group has won several international competitions, including first place at the “Europe and Its Songs” international choir festival in Barcelona in 2003 and first place at the Concorso Internazionale Di Canto Corale “Seghizzi” held in Italy in 2017. Tourists can experience Boholano musicality on a Loboc river cruise, which culminates with musical presentations.

Another occasion on which tourists can experience Boholano cultural creativity is during the monthlong Sandugo festival held every July in Tagbilaran City. The celebration commemorates the blood compact between the Spaniard Miguel Lopez de Legaspi and the native Rajah Sikatuna in 1565 marking the historic peace pact and the opening of the province to the world. The celebration starts on July 1 and wraps up with a street dancing competition on the third or fourth Sunday of the month. This is the major tourist attraction of the city of Tagbilaran.

Bohol is known for its religious festivals and parades, especially its grand fiesta celebrations. Dating back to the Spanish period, pista is a community (town, barangay, sitio) celebration of thanksgiving in honor of the local patron saint. Cultural presentations are held for at least two days. Families prepare food not only for their relatives and friends but for anybody who comes into their homes. Food is offered all day. During the pista season (especially in the month of May) tourists can experience a festive atmosphere while witnessing traditional dances and musical presentations, often in public places.

Bohol’s traditional handicrafts are produced for touristic consumption as well as for export. Products of loom weaving in the towns of Tubigon, Inabanga, Albur, and Buenavista, basket weaving in Antequera, and pottery making in Albur and Calape can be purchased in souvenir shops in tourist destinations as well as city malls. Tourists can also taste and take home traditional Boholano sweets, including calamay (made of glutinous rice powder, coconut milk, brown sugar, and peanuts) from Albur and Jagna, and peanut kisses and other locally baked pastries.

I-3 Tourist Facilities and Services

By Air, by Sea, and by Land

The island of Bohol can be reached by either airplane or boat. Bohol has one airport, Bohol-Panglao International Airport. The airport project was sponsored by the Japanese International Cooperation Agency. At present, there are seven direct flights connecting Bohol and Manila. Three main airline companies offer services on this route: Philippine Airlines, Cebu Pacific Air, and AirAsia. The one-way fare is around PHP3,500 (around US$67). On June 22, 2017, direct international flights began between Seoul-Incheon and Tagbilaran Airport.

An alternative way of getting to Bohol is by ship. There are at least four major seaports in Bohol: Tagbilaran, Tubigon, Jagna, and Ubay. There is no direct sea route between Manila and Tagbilaran. However, since air travel is inexpensive and more convenient than sea travel, people prefer to take a flight from Manila. From Cebu, it is most convenient to sail into the ports of Tubigon and Tagbilaran because of their proximity and the frequency of ferries. On the Cebu–Tagbilaran route, slow ferries cost around PHP210 (US$4) and fast ferries around PHP350 (US$7). The Cebu–Tubigon route is shorter and cheaper. Pump boats also ply between Cebu and the towns of Getafe and Inabanga. Traveling within Bohol is not a problem. Public land transportation is affordable. This includes open-air buses, air-conditioned vans, jeepneys, cabs, tricycles, and habal-habal (transport motorbikes). Tourists can also rent cars and motorcycles.

Accommodations and Other Services

Bohol has luxury hotels and resorts, tourist inns, pension houses, travel lodges, and homestays. In 2015 (the latest year for which data is available), the Bohol Tourism Office counted 360 accommodation establishments in the province, with a total of 6,370 rooms (Province of Bohol 2015, 24). This number is far higher than the 2,000 rooms counted in 2010 (Province of Bohol and German Development Service 2010, 8). These accommodations are spread throughout the province, especially in Tagbilaran City, Panglao Island, and Baclayon. With its fine white beaches and proximity to the capital city, Panglao Island has the greatest number of resorts and spas, including a five-star hotel and exclusive resorts.

There are 15 BTO-accredited local travel agencies in Bohol. For those who like shopping, Bohol has shopping malls and department stores. The three main shopping malls are Bohol Quality Mall, Island City Mall, and Alturas Malls. Withdrawing cash is convenient, with 49 banking units and ATMs scattered around the city and municipalities (Province of Bohol and German Development Service 2010, 8). Communications are convenient, with telecommunications companies providing mobile and Internet services.

II Governing Bohol Tourism

As mentioned earlier, tourism is a major industry in Bohol. Concerned with reducing the province’s poverty incidence, the provincial government considers tourism as one of the means to achieve economic growth. Adopting the concepts and strategies of pro-poor tourism, local government officials and planners look to tourism to uplift the socioeconomic condition of poor local communities through employment, sharing of income, and growth of local entrepreneurship while at the same time conserving the province’s natural resources (Province of Bohol and German Development Service 2010, 1). To achieve these goals, it is crucial for the local government to build institutions and craft legislation.

II-1 Institutionalizing Tourism

Establishing institutions for nature-based tourism strengthened Bohol’s tourism development. With the aim of developing a general framework for tourism development, a memorandum of agreement was signed between the Soil and Water Conservation Foundation and the provincial government of Bohol in 2005. Through the Provincial Planning and Development Office (PPDO), the Bohol Environment Management Office (BEMO), and the BTO, preparatory steps were taken for the formulation of the Biodiversity Conservation and Ecotourism Framework Plan of Bohol as mandated under the Bohol Environment Code of 1998.

The partnership project involved national agencies, particularly the DOT and the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). European development agencies assisted by providing technical and financial support. These agencies included the German Development Service (DED) and Soil and Water Conservation Foundation (SWCF) for technical support; InWEnt for financial assistance; and the UNDP-GEF-SGF Program and the European Union, both through SWCF (Province of Bohol and German Development Service 2010, 2).

To provide technical assistance during the formulation of the tourism framework plan, the provincial government of Bohol established a multi-sectoral Ecotourism Technical Working Group. This was composed of regional and provincial government agencies—such as the DENR, DOT, BEMO, PPDO, and BTO—and nongovernmental organizations. Organizers provided modular training for LGUs, NGOs, local communities, academe, and the private sector from March to November 2005. The training focused on topics such as ecotourism and biodiversity, ecotourism product development, marketing and promotion, and monitoring and evaluation (Province of Bohol and German Development Service 2010, 3).

The workshop produced the Bohol Ecotourism Club, composed of representatives from local governments, NGOs, local communities, and the private sector. Serving as a “prime mover” and “watchdog” for ecotourism activities in the province, the body ensures the inclusion and implementation of ecotourism principles in municipal tourism development projects. It also seeks to educate the public on ecotourism and to recommend acceptable ethical standards on tourism development projects in Bohol. One of the organization’s roles is to be a “communities’ mentor” to guide people to see alternative income-earning opportunities through tourism (Province of Bohol and German Development Service 2010, 3).

The project came to be known as the Biodiversity Conservation and Ecotourism Framework Plan of Bohol 2006–2015. It served as a bible for investors, people in the tourism business sector, municipal executives, planners, and NGOs in the province for their tourism development and biodiversity conservation projects. Guidelines included principles, regulations, standards, best practices, and ethics for tourism activities that the government considered to be in line with its vision.

Specialized agencies composed of national, provincial, and local government units, NGOs, and organizations from the private sector are in place to promote and facilitate the development of tourism in the province. One is the Provincial Tourism Council. The council was originally composed of more than 50 members—60 percent from the private sector and 40 percent from the government. Before this body was created, a Committee on Tourism was an integral part of the Sanguniang Panlalawigan (provincial council). During that time there was an independent Provincial Investment Office, which had a section for the tourism sector until 1997.

Intending to run for mayor, the Committee on Tourism chairperson of the Sanguniang Panlalawigan decided to turn over the responsibilities of the committee to the Provincial Investment Office. In 2007 the tourism section of the investment office became a separate provincial government entity. This was when the tourism industry started to grow, and the former office was no longer adequate to accommodate the growing needs of the industry. Now, the Bohol Tourism Office (formerly the Provincial Tourism Office) functions as the secretariat of the Provincial Tourism Council.

Since all tourist sites are under the administration of LGUs, the provincial government cannot develop tourist attractions on its own. However, it oversees the overall tourism development activities in the province and provides for the needs of LGUs. The BTO has become the advice-giving and coordinating body of the province for tourism development. The BTO has specific responsibilities. First, it helps LGUs and the private sector in developing their own tourist sites. It also orients planners regarding policies and other issues concerning tourism in the province. It accepts tourism project proposals from LGUs and provides advice and suggestions concerning the viability and marketability of such projects. Second, being the marketing arm of the provincial government, the office employs forms of communication such as posters, brochures, and videos to promote Bohol tourism to the world. Seeing the potential of proposed tourism projects, the office also provides clients for local tourism businesses.

Third, the BTO organizes basic skills training for tourism and hospitality services. In coordination with other government agencies, such as the Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (TESDA), the office organizes seminars and workshops for LGUs, community organizations, and other tourism practitioners to enhance their services. Training includes basic culinary arts, customer service, tourist guiding, and operation of cottages and accommodations. The office also coordinates closely with other government agencies like the DOT for professional and financial resources, especially in organizing seminars, and the DENR on issues concerning protected areas that are now being utilized as tourist attractions.

The Provincial Tourism Council and the BTO have limited power. Although these institutions are under the Office of the Provincial Governor, they cannot take decisions regarding implementation of policies, nor can they regulate tourist activities. Officers are elected, but members meet regularly only twice a year. Core group members meet regularly, and in special cases they discuss pressing issues.

Another government agency that is involved in the province’s tourism industry is the Protected Area Management Board (PAMB) under the DENR. The body is composed of barangay captains (village chiefs) and municipal mayors of localities enclosed within protected areas. One-fourth of the entire island of Bohol (75,766 hectares) consists of protected areas (Province of Bohol and German Development Service 2010, 11–12). Many of these have become tourist sites, including the Chocolate Hills, Man-made Forest in Bilar, Loboc Watershed, Tarsier Sanctuary in Corella, and 15 marine sanctuaries within the seas of Panglao, Dauis, and Baclayon.

As the governing body for deciding on matters related to policy and the administration of protected areas, the PAMB reviews project proposals and tourist activities to check that they comply with the set standards for ecological conservation. The body also decides on budget allocations (Province of Bohol and German Development Service 2010, 15). Coordinating closely with the BTO, the PAMB discusses with development planners on issues related to developing tourist sites in protected natural environments.

II-2 Enacting Tourism

Aside from institutionalizing tourism, the Bohol provincial government also enacts policies and environmental ordinances for tourism development. This legislation aims to ensure the protection of natural and cultural resources in order to help the tourism industry. Such ordinances are put in place in response to national legislations (e.g., Protected Areas System in the Philippines [RA 7586 or NIPAS Act of 1992]) that promote ecological conservation and ecotourism. Bohol pioneered a provincial legislation, the Bohol Environmental Code of 1998, to protect the natural environment, which has become a major component of its tourism industry. This code has become a model for other local governments in the country.

In 2007 the Act to Declare the Province of Bohol as an Eco-cultural Tourism Zone (RA 9446) was promulgated. This law mandates the DOT, the provincial government, and the city of Tagbilaran to coordinate closely in developing and promoting tourism in the province. Coordination involves formulating development plans, protecting natural and cultural resources, consolidating political powers, providing technical and material assistance, and partnering with private and nongovernmental agencies. The law produced the Bohol Tourism Master Plan, which “would be a unified direction of the province to further harness and sustain its vast tourism potential” (Province of Bohol 2007, 1). This law was further strengthened by the promulgation of the Tourism Act of 2009 (RA 9593).

Since 1995 there have been at least 165 provincial ordinances, resolutions, and policies related to tourism development. Many of these concern coordination among different LGUs, particularly with municipal mayors, NGOs, and private agencies. These ordinances urge and encourage partnerships among stakeholders in developing and governing tourist activities. In 2017 the province prepared the Bohol Surprise Tours program, which highlighted 12 new local ecotourism destinations. This program showcases the livelihood activities of host communities as tourist sites. The same year, the province—along with the DOT, the United States Agency for International Development, and private sector representatives—launched the province’s new branding: “Behold Bohol.” This branding aimed to project the revival of Bohol after the 2013 earthquake.

Developing Bohol tourism is a collaborative effort between the provincial government and municipalities. Through the BTO, the provincial government provides municipalities with technical assistance. Technical support includes training of local tourism officers and staff, advertising and packaging of products, and mapping of possible tourism resources. The provincial government also helps in constructing roads leading to tourist destinations. Though the provincial governor heads the entire province, the municipal mayors still have the power to decide the direction of local tourism development. In this sense, the municipalities have greater influence than the provincial government. However, the provincial government provides the general framework and legislative mechanisms to encourage the growth of tourism in municipalities.

After the implementation of the Bohol Tourism Master Plan, LGUs at the municipal level started to develop their own tourism programs and activities. Since LGUs administer most of the tourist sites, they have control over these areas in terms of management. LGUs either coordinate with private agencies to provide environments conducive to tourism, or they develop and manage touristic enterprises by themselves.

Loboc municipality provides an example of collaborative tourism. The town is known for its river cruise. The tourism project is a product of a partnership among the LGU, donor agencies, private investors, and local community organizations. The LGU provided the necessary facilities around the tourism complex, including building the river port for boats and floating restaurants, developing the tourism office and terminal, and providing access and a huge parking area. Private businesses manage the cruise, the shops, and the floating restaurants. Local community organizations participate through musical and cultural performances held along the riverside. Foreign government donors sponsor the lighting in the river’s vicinity.

The Abatan river tour is an example of an exclusively LGU-managed tourism enterprise. The project involves the four neighboring municipalities of Cortes, Maribojoc, Balilihan, and Catigbian. The tour features a cruise through the mangrove forest along the river connecting these municipalities. It includes a visit to waterfalls and local villages, and cultural presentations at the Tourism Center. The coastal municipalities of Panglao, Dauis, and Baclayon have also initiated a similar partnership, called Padayon. The three towns are located within the Bohol Marine Triangle, where there are five major marine ecosystems (see Green et al. 2002, 48). This collaborative project aims at environmental preservation for tourism development.

II-3 Tourism Leadership

Leadership plays an important role in the growth of tourism. The tourism industry of Bohol would not be possible without the leadership of local politicians. Prominent local figures helped bring Bohol tourism to where it is now. The three main personalities were Rene Relampagos, Erico Aumentado, and Edgardo Chatto. With political will and shared vision, these leaders were able to continue what their predecessors had started, despite their differences in political affiliation.

The laying of the groundwork for tourism development in Bohol can be attributed to Relampagos. He has served as a Provincial Board member (1989–92), vice governor (1992–95; 2019–), governor (1995–2001), and member of the House of Representatives (2010–19). During Relampagos’s term as governor, the Bohol Environmental Code (Province of Bohol 1998) was promulgated, which created the BEMO. The code is considered to be the first of its kind in the Philippines and became a model for other provinces in the country. This legislation became the ground on which tourism policies and guidelines sprouted.

During Relampagos’s term as governor, concerns over environmental protection and management were brought to the fore. These gained primary importance in policy making and in formulating development programs for the province. Care for the environment became the starting point for Bohol to engage in ecotourism as a model for tourism development. During Relampagos’s term, the province collaborated with various international and national government agencies, NGOs, and local communities.

What Relampagos prepared, Aumentado cultivated. Aumentado defeated Relampagos in the 2001 gubernatorial race. He started as a member of the Provincial Board (1967–86), then became the vice governor (1988–92), a congressman (1992–2001; 2010–12), and the governor of Bohol (2001–10). In 2001 Bohol was considered one of the poorest provinces in the country. Aumentado saw the potential in tourism as a means of poverty reduction. During his term he placed Bohol on the tourism map, and eventually the province emerged as one of the top tourist destinations in the country.

Aumentado continued what his predecessor had started, establishing ties and crafting development plans. Through collaborative work among local and national government agencies and NGOs, Aumentado’s administration produced the Biodiversity Conservation and Ecotourism Framework Plan of Bohol 2006–2015. The plan came about as a response to Executive Order No. 111 (EO 111) (Estrada 1999), which laid the guidelines for ecotourism in the country. The framework became the basis for development projects and activities in the province. During Aumentado’s administration the Bohol Arts and Heritage Code (Province of Bohol 2008) was also promulgated. This code provided the legal basis for the promotion and development of culture-based tourism.

Aside from establishing legislative and institutional mechanisms, Aumentado improved the basic infrastructure of the province. He fixed the circumferential road (the Carlos P. Garcia Circumferential Road) and the minor roads connecting the municipalities, which made transport and access to tourist destinations faster and more convenient. Pacifying the Communist insurgency in Bohol was also considered a great achievement of the former governor. He died in December 2012.

A lawyer by profession, Chatto has served as a member of the Provincial Board (1980–86), mayor (1988–95), vice governor (1995–2001), congressman (2001–10; 2019–), and governor (2010–19). The greatest challenge Chatto faced as governor was the 2013 earthquake. The 7.2 magnitude earthquake left the province with a high number of casualties and heavily damaged roads, bridges, houses, and buildings. Tourist sites and cultural structures, including the Chocolate Hills complex and many of the century-old heritage churches, were heavily damaged.

Through the help of international agencies, Chatto was able to rehabilitate the province. The Behold Bohol project highlights how Bohol reemerged as a tourist destination after the tragic earthquake. During Chatto’s administration, Panglao-Bohol International Airport was also inaugurated. Though Chatto belongs to the opposition party, his support for the Duterte administration gives him a political advantage in pursuing his plans and projects.

III Selling Tourism: The Case of the Local Government of Danao

The town of Danao is in the central part of Bohol. It is located around 66 kilometers (the fastest route) northeast of Tagbilaran City and can be reached by car in around two hours. The town has 17 barangays and had a population of 17,890 in 2015, with 3,364 households. It has an average income of PHP90 million and in 2016 had an Internal Revenue Allocation amounting to around PHP75,526,524. The main source of livelihood in Danao is basic farming. With the LGU-run tourism development, Danao rose from being a sixth-class municipality in 1999 to a fourth-class municipality and ranks first in Bohol and the region in income generation efficiency.

III-1 From Insurgency to Hospitality

Before tourism was developed in Danao, the town was known for its political insurgencies and poverty. The province of Bohol was an insurgent hotbed from 2000 until it was declared insurgent free in March 2010 (Torres 2011, 1). Several attacks and gunfights took place in the province, including raids of government and business centers that were related to insurgent groups. The extreme poverty in the area, especially in farming communities, formed a seedbed for ideology-based conflict. This was the experience of people for decades, although this phenomenon was not something new for Danao. Historically, the town was the headquarters of the group of Fernando Dagohoy, the leader of the longest revolution in Philippine history (1744–1829).

Danao was known also for its poor, malnourished, and low-educated population. In 2003 it was considered the poorest municipality of Bohol and one of the poorest in the country, with a score of 57.2 on the poverty index (National Statistical Coordination Board 2009). Some people survived on small-scale traditional farming and charcoal making. Others moved away to work as domestic help and laborers, undermining family life. With these social and economic conditions, Danao became a pilot area for national government assistance. Government agencies started to introduce livelihood projects among the local people. However, local communities found the assistance insufficient, and the help made people more dependent on government support rather than motivating them to exert the effort to improve their livelihoods.

Today, the local government of Danao is noted for its tourism enterprises. The LGU-run tourism program came to be known as E.A.T. Danao (Eco, Educational, Extreme Adventure Tour). The program’s activities take place at Danao Adventure Park, around 7 kilometers from the town center. The landscape includes cliffs, caves, rivers, rock formations, and century-old trees. These natural features provide a unique venue for outdoor adventure activities, including trekking, kayaking, caving, cliff plunging, zip-lining, rappelling, and root climbing. Visitors can also enjoy the “Sea of Clouds,” a formation of fog and clouds suspended near the tops of neighboring mountains in the early morning.

Then Municipal Mayor Jose Cepedoza floated the idea of having a tourism enterprise in 2001. The idea was realized through his successor, Mayor Louis Thomas Gonzaga, and led to the opening of the park in 2006. Informants said that the concept of an adventure park came about after the mayor experienced AJ Hackett Bungy Jumping in Queenstown, New Zealand. The country offers several adventure activities, particularly on its mountainous terrain. The mayor shared the plan with his advisers and formed a team to conduct a feasibility study. After the death of Mayor Gonzaga in 2016, his mother, Natividad, took office and is continuing the project.

Danao Adventure Park is a product of collaboration and partnerships among stakeholders. The tourist activities started with caving and mountain trekking, until groups of tourists saw the potential of the place. River-based activities were added later. Danao LGU started to connect with adventure enthusiasts, government agencies, and tour businesses for support. Danao’s fame spread, and government agencies—including the DOT and DENR—came to acknowledge the potential of the park.

The DENR helped Danao with resource inventory. The DOT assisted the LGU with product development and marketing. The Department of Trade and Industry helped with the making of souvenir items, while the TESDA helped with the training of local personnel in tourist services. Tour businesses in Bohol and private individuals also helped. Tour agents, Web bloggers, and adventure enthusiasts assisted with the product test run, product development, and marketing. The World Bank and the Development Bank of the Philippines also assisted.

The development of Danao tourism is a result of local participation. Local people were involved in the planning and implementation of the project. During the initial stages, they worked together with private agencies and individuals. LGU employees and officials contributed extra hours of work without pay. Barangay officials encouraged their communities to do voluntary work. Civil society organizations helped on the ground without pay. Volunteers helped with clearing the areas where the adventure park would be established, landscaping, and marketing adventure tours. They also started to act as tour guides (Jensen 2010). Local leaders learned through feedback from visitors and tourists how to improve the place and services. This spirit of cooperation led to a sense of community ownership among the local people.

III-2 Tourism Benefiting Local People

The main sources of income from tourism activities in Danao include revenues from individual entrance and parking, adventure activities, and accommodation services. At the time of this study, entrance fees were around PHP40 and parking fees PHP10–30. Adventure activities cost around PHP350 per person, aside from the more expensive “Plunge,” which costs PHP700. Danao Adventure Park has accommodations ranging from PHP600 to PHP1,000 per night. The park also offers adventure packages, which cost PHP1,500–3,500 per person and may include food and accommodations.

LGU-run tourism was able to contribute to the economic and social well-being of the local people. It took two years for Danao to profit from its LGU-run tourism industry. Based on municipal records provided by the Danao LGU, in 2009 Danao had an income of around PHP4.8 million from tourism-related enterprises. The figure grew to PHP21.25 million in 2012. In 2010 the LGU started to give back to the local people what had been gained through their cooperation. However, after the great earthquake hit Bohol in October 2013, Danao experienced a decrease in income due to the low number of tourists. The LGU also had to spend huge amounts on repairing tourist facilities. In 2014 the number of tourists plunged to 7,261 from 25,531 the preceding year. Danao is slowly regaining its visitors. From January to October 2017, there were 23,042 tourist arrivals.

Tourism has provided alternative means of livelihood and social services for the community. Benefits from tourism come in the form of livelihoods, employment, and social services. Social services include scholarship programs, subsidized hospitalization programs, free use of ambulances, supplemental feeding, and health insurance programs. Danao Adventure Park employed 13 local guides in 2006. The number grew to 35 in 2008 and continued to increase to 45 in 2009. Today, local tourism directly employs more than 100 local people as tour guides, accommodation and food service staff, and maintenance and support personnel. Other local people who are earning an income from tourism are the People’s Organizations, which provide food to the LGU-run restaurant and sell souvenir items to visitors. In the area of education, the LGU started the Iskolar sa Torismo (Scholars of tourism) program in 2011. At the time of this study, 83 college students were receiving scholarships in various state colleges and universities in the province. The scholarship program has produced 12 graduates since its inception.

Most of the benefits from tourism go toward health services. The subsidized hospitalization program helps poor patients with their medical fees. From 2011 until the time of this study, 221 people had benefited from the program. The subsidy for the health insurance program had benefited around 4,000 people. The LGU’s free ambulance service has been supported by revenues from tourism activities since 2011. However, the supplemental feeding program for preschoolers ran for only a year.

Aside from the economic and social benefits, tourism has created environmental awareness among local people. People have started to participate in ecological preservation activities. They have stopped cutting trees for their former livelihood of charcoal making. In a personal interview, Mayor Natividad Gonzaga argued that aside from the material benefits gained from tourism, the most valuable outcome was the regaining of pride among the people of Danao. She emphasized that tourism had brought back pride to the place, and the municipality had evolved from being identified as backward and poor to attracting people from around the world with its natural and cultural wonders.

Conclusion

This study examines the changing role of governments in tourism development. Governments play a crucial role in the development of the tourism industry. Local governments have evolved from being passive to more active actors in the industry. From merely providing laws and building infrastructure, governments now manage their own tourism-related businesses. In past decades, the management of tourism was entrusted to the business sector. Multinational corporations and private businesses controlled the operation of resorts, hotels, and other tourist services with minimal intervention from the government. Now, LGUs are competing with private operators.

Entrepreneurial LGUs are a new phenomenon. From governing tourism, LGUs are now also selling tourism. Aside from tax revenues, local governments are gaining additional income from their self-managed tourism businesses, and at the same time they provide employment to local people. This new trend challenges the traditional role of governments in tourism development. It raises questions over how LGUs can carry out governance as well as do business at the same time. With their political advantage, are LGUs more effective than their private counterparts in managing tourism and delivering its benefits to communities?

To illustrate this new phenomenon, this study highlights the case of the tourism industry in the province of Bohol in the Philippines. It examines how LGUs in Bohol can perform both political and corporate functions in tourism. First, the study explores how the provincial government lays the foundation for the development of tourism in its local destinations. Second, this study examines the case of the municipality of Danao as a model for how a once-poor town could grow to become an LGU. With Danao’s natural beauty, its culture, and the cooperation of the local people, the LGU of Danao was able to harness the economic, social, and environmental benefits of tourism.

Bohol has evolved from being a poor to a high-income-generating province with the growth of local tourism. Tourism development has also become a tool to address the problem of political insurgency, which affected people of the province for decades. The province has become one of the top tourist destinations in the country. Its natural beauty and colorful cultures have attracted both domestic and international tourists. Despite the disruption brought about by the great earthquake of 2013, the number of tourist arrivals continued to grow through the years.

The provincial government set the ground for tourism to grow in Bohol. It institutionalized tourism by organizing collective action among various government units, nongovernmental agencies, and local people. Collaboration among stakeholders created political mechanisms that governed tourism and at the same time encouraged LGUs to engage in tourism development projects. Aside from governing tourism, multi-sectoral institutions enable local executives and their communities to obtain the necessary knowledge and skills to manage and operate tourism-related businesses. Tourism has become embedded into local governance.

Aside from institutionalizing tourism, the provincial government of Bohol has provided legislative mechanisms that directly impact tourism. Bohol pioneered a tourism code for regulating tourism development. This code has become a model for other LGUs in the country. Enacting tourism provides a solid legal basis for regulating tourist activities and development. The Bohol tourism code has become a framework for the provincial tourism development plan.

Institutional and legislative mechanisms could not have been efficient without the leadership of Bohol’s local executive. This study highlights the crucial role of three local politicians in the growth of tourism: Relampagos, Aumentado, and Chatto. With their political will and openness to collaboration with other agencies, they were able to put Bohol on the global tourism map.

The municipality of Danao illustrates how an LGU is able to carry out governance as well as do business. From being a poor town, Danao has evolved into a top income-generating municipality in the region. From being a hotbed of insurgency, it is now a top adventure tourism destination in the province. Danao tourism development is a result of leadership and collective action. Collaboration among stakeholders has transformed the once-sleepy town into an ecotourism playground. The LGU, with its political advantage, built its own tourism business through collaboration with different government agencies, NGOs, businesses, and private individuals. This collaboration facilitated the planning, marketing, and operation of tourist services. Thanks to government-run tourism businesses, local people are now participating in and enjoying the rewards of the industry.

Close collaboration enabled the development of tourism in Bohol. The growth of the industry would not have been possible without collaboration among the provincial government, municipalities, and private sector. Although this collaboration was challenged by issues of power relations, particularly between the provincial and municipal agencies, these issues were addressed through constant communication among leaders. Legislative and technical assistance from the provincial government is crucial since it enables municipal governments to engage in the industry. Municipal leadership is crucial in encouraging communities to participate in the tourism industry. The provincial government provides the face of Bohol tourism to the world, while municipal governments provide the actual experience.

This study has mainly explored the wider view of tourism in Bohol. A grassroots-level study of the experiences of local households with the growth of tourism in their localities would be relevant. Examining the political and moral economy of local tourism development would also generate insights into the dynamics of local tourism development.

Accepted: December 15, 2020

References

Crick, Malcolm. 1989. Representations of International Tourism in the Social Sciences: Sun, Sex, Sights, Savings, and Servility. Annual Review of Anthropology 18: 307–344.↩

Department of Tourism Region VII. 2016. Report on Regional Distribution of Travelers – Bohol: January–November 2016 (Partial Report).↩

Eadington, William; and Smith, Valene. 1992. Introduction: The Emergence of Alternative Forms of Tourism. In Tourism Alternatives: Potentials and Problems in the Development of Tourism, edited by Valene Smith and William Eadington, pp. 1–12. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.↩

Edgell Sr., David; Allen, Maria DelMastro; Smith, Ginger; and Swanson, Jason R. 2008. Tourism Policy and Planning: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow. Oxford and Burlington: Elsevier.↩

Estrada, Joseph Ejercito. 1999. Executive Order No. 111 (EO 111), s 1999: Establishing the Guidelines for Ecotourism Development in the Philippines. Office of the President of the Philippines.↩

Farrell, Bryan; and Runyan, Dean. 1991. Ecology and Tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 18(1): 26–40.↩

Fennell, David. 2008. Ecotourism: Third Edition. London and New York: Routledge.↩

George, E. Wanda; Heather, Mair; and Reid, Donald G. 2009. Rural Tourism Development: Localism and Cultural Change. Bristol, Buffalo, Toronto: Channel View Publications.↩

Green, Stuart J.; Alexander, Richard D.; Gulayan, Aniceta M.; Migriño III, Czar C.; Jarantilla-Paler, Juliet; and Courtney, Catherine A. 2002. Bohol Island: Its Coastal Environmental Profile. Cebu City: Bohol Environment Management Office, Bohol and Coastal Resource Management Project.↩

Hall, Michael; and Boyd, Stephen, eds. 2005. Nature-Based Tourism in Peripheral Areas: Development or Disaster? Clevedon: Channel View Publications.↩

Hitchcock, Michael; King, Victor; and Parnwell, Michael, eds. 1993. Tourism in South-East Asia. London: Routledge.↩

Holden, Andrew. 2008. Environment and Tourism. London and New York: Routledge.↩

Hunter, C.; and Green, H. 1995. Tourism and the Environment: A Sustainable Relationship? London and New York: Routledge.↩

Jamal, Tazim B.; and Getz, Donald. 1995. Collaboration Theory and Community Tourism Planning. Annals of Tourism Research 22(1): 186–204.↩

Javier, Aser B. 2002. Public Entrepreneurship as a Local Governance Strategy in Decentralizing Polity: Exemplary Initiatives from the Philippines. Forum of International Development Studies 21: 17–42.↩

Jensen, Øystein. 2010. Social Mediation in Remote Developing World Tourism Locations: The Significance of Social Ties between Local Guides and Host Communities in Sustainable Tourism Development. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 18(5): 615–633.↩

Krippendorf, Jost. 1982. Towards New Tourism Policies: The Importance of Environmental and Sociocultural Factors. Tourism Management 3(3): 135–148.↩

Long, Veronica. 1992. Santa Cruz Huatulco, Mexico: Mitigation of Cultural Impacts at a Resort Development. In Tourism Environment, edited by T. V. Singh, V. Smith, M. Fish, and L. Richter, pp. 135–147. New Delhi: Inter-India Publications.↩

McIntosh, Robert W.; and Goeldner, Charles R. 1986. Tourism: Principles, Practices, Philosophies. New York: John Wiley & Sons.↩

Murphy, Peter. 1985. Tourism: A Community Approach. New York: Methuen.↩

National Statistical Coordination Board (NSCB). 2009. 2003 Municipal and City Level Poverty Estimates. Makati: NSCB.↩

Philippine Statistics Authority. 2018. Quickstat Bohol. https://psa.gov.ph/content/bohol-quickstat-february-2018, accessed March 20, 2018.↩

―. 2017. Contribution of Tourism to the Economy Is 8.6 Percent in 2016. http://www.psa.gov.ph/content/contribution-tourism-economy-86-percent-2016, accessed February 5, 2018.↩

Province of Bohol. 2015. Tourism Profile. PPDO Bohol: Economic Sector.↩

―. 2008. Bohol Arts and Heritage Code.↩

―. 2007. Master Plan Report for the Tourism Master Plan and Pre-feasibility Study on the Tourism Clusters of Bohol Province.↩

―. 1998. The Bohol Environmental Code of 1998.↩

Province of Bohol; and German Development Service. 2010. Biodiversity Conservation and Ecotourism Framework Plan of Bohol 2006–2015. http:www.ppdobohol.lgu.ph/?page_id=2727, accessed June 18, 2011.↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

Republic Act No. 7160 (RA 7160). 1991.↩

Republic Act No. 7586 (RA 7586). 1992.↩

Republic Act No. 9446 (RA 9446). 2007.↩

Republic Act No. 9593 (RA 9593). 2009.↩

Torres Jr., Ernesto C. 2011. A Success Story of Philippine Counterinsurgency: A Study of Bohol. Master’s thesis, Faculty of the United States Army Command and General Staff College.↩

United Nations Steering Committee on Tourism for Development. 2011. Tourism and Poverty Reduction Strategies in the Integrated Framework for Least Developed Countries. Geneva: Trade and Human Development Unit.↩

Vanhove, Norbert. 1997. Mass Tourism. In Tourism, Development and Growth: The Challenge of Sustainability, edited by Salah Wahab and John J. Pigram, pp. 50–77. London and New York: Routledge.↩

World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). 2017. Tourism Highlights 2017 Edition. https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284419029, accessed February 5, 2018.↩

―. 2015. Tourism Highlights 2015 Edition. Madrid: World Tourism Organization.↩