Contents>> Vol. 10, No. 2

Conjugal Mayorship: The Fernandos and the Transformation of Marikina, 1992–2010

Meynardo P. Mendoza*

*Department of History, School of Social Sciences, Ateneo de Manila University, Leong Hall Building, Ateneo de Manila University, Loyola Heights, Quezon City 1108, Philippines

e-mail: mpmendoza[at]ateneo.edu

DOI: 10.20495/seas.10.2_255

From 1992 to 2010, during the mayoral terms of Bayani and Maria Lourdes Carlos-Fernando, Marikina underwent an extensive transformation. The husband-and-wife team transformed it from a sleepy, semi-agricultural third-class municipality into a model city and the recipient of many awards and distinctions. Aside from providing the physical infrastructure needed to lay the foundation for the city, the Fernandos also transformed the residents by promoting a culture of order and discipline, and later on introducing corporatist practices in the delivery of basic services. In the process, Marikina became sustainable from a financial and environmental standpoint. This paper argues that Marikina’s transformation can be attributed to the following: first, that the skill sets the mayors possessed matched the city’s needs at the time of their tenure; second, that Marikina’s resurgence coincided with the reforms implemented after the transition to democratic rule starting in 1986, in particular, the passage of the Local Government Code; and, third, that Marikina experienced a continuity of policies even if there were changes in leadership. The city did not suffer from what may also be termed as “cancel culture,” wherein gains made by the previous administration were negated as a result of highly polarized politics. The paper further argues that aside from agency, Marikina’s development was also conjunctural. Marikina’s success may be attributed to the confluence of interests among stakeholders; a phenomenon termed policy coalition.

Keywords: Marikina, local transformation, policy coalition, good governance, model city, local politics

Introduction

Marikina’s Great Leap Forward occurred when Bayani Fernando (or BF, as he is called by locals) became the mayor of Marikina in 1992. But unlike the Great Helmsman, Bayani could not use charm and ideology to remold his vision, for he did not possess those attributes. Rather, he styled himself after another Asian strongman of another mold, the neo-Confucian leader Lee Kuan Yew, whose authoritarian style of governance made Singapore what it is today. Singapore, the bustling, clean, and modern city where discipline and respect for authority reign supreme, became the model for Marikina’s transformation. Thus, Bayani Fernando may well be Marikina’s version of Lee Kuan Yew. Both Lee Kuan Yew and Bayani command respect and admiration for their achievements, but certainly not affection. Mao Zedong, on the other hand, had a cult-like following and was treated as an icon even though he led the country to destruction along with the Red Guards. And while Mao and Bayani were succeeded by their spouses, Maria Lourdes (or Marides) is no Jiang Qing. Marides was elected by a big majority, possessed great talent not in drama but in management, and did not belong to a Gang of Four. And while Bayani may have utilized some of the more persuasive practices of Singapore and China in governance, Marikina’s success lay in the cooperation of other stakeholders—business, labor, nongovernmental organizations—who found themselves sharing a common issue and working with the local government to achieve a common goal.

On one level, the husband-and-wife team transformed Marikina by laying the infrastructure groundwork to remodel the city into something new. It has clean and orderly streets with wide sidewalks and bike lanes; motorists following traffic rules and regulations; residents paying their taxes before the deadline; a rehabilitated river park where residents can jog, stroll, or simply gather for family reunions or group meetings; and civility in public spaces. This was hardly the image Marikina had earlier. Until the early 1990s, it was a sleepy, laid-back third-class municipality where visitors came only for its shoe shops. After 18 years, the Fernandos had transformed Marikina into a vibrant model city, so much so that it was adjudged one of the best-managed cities in the Philippines and among the best choices to invest in and raise a family (Vera 2008, 28). After the end of the Fernandos’ terms, Marikina received many awards and distinctions.

On another level, the husband-and-wife team also undertook a sort of cultural revolution. In the Fernandos’ vision of the future, urbanization needed to go hand in hand with public order and decency in public spaces. The husband-and-wife team imposed discipline and public order in the form of urbanidad (roughly translated as “urbanity” or “civility”) or the aesthetic sense of living in a city. Gone are the days when men spat, drank, and urinated in public. Women can no longer hang out their laundry for the public to see. Drivers obey street signs. To provide residents with constant reminders, sidewalks have been inscribed with edicts.

I Marikina’s Geography and Politics

The area now known as Marikina was founded as a mission area by Jesuit missionaries around 1630 (Fabros 2006, 15). Its original inhabitants settled near the river, a tributary of the Pasig River, which linked San Mateo and Montalban in the north to Manila. The first church was established in present-day barangays Barangka and Jesus de la Pena at the foot of the Ateneo de Manila University. Old-time residents claim that Marikina’s boundaries extended to 15th Avenue in Cubao until the creation of Quezon City in 1937.1) In fact, President Manuel Quezon’s former Marikina rest house is now the site of the Light Rail Transit 2 Santolan Station. By 1773, Marikina had been given as a land grant to the Tuason family (Fabros 2006, 16), Chinese mestizos whose descendants include Miguel Arroyo, husband of former President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo.

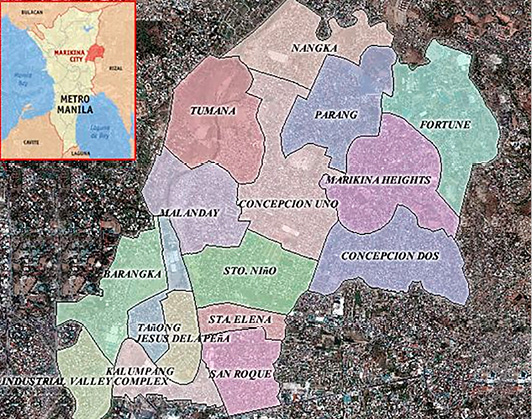

Marikina may be divided into two areas. The First District consists of nine barangays and has a land area of 850.53 hectares, or 39.56 percent of the total, while the Second District has seven barangays but a larger land area, with 1,297.47 hectares or 60.44 percent of the total (Marikina City 2020). The First District is the town center, composed formerly of four barangays—Sta. Elena, Sto. Niño, San Roque, and Calumpang—and straddles the southern part of the Marikina River (see Fig. 1). This is Marikina’s old quarters, where the first settlement took place. This is also where the munisipyo (municipal and later city hall), the main church, market, hospital, and sports center are located. As can be expected, this is where old families reside; their businesses (shoes, retail, small- to medium-scale industries) and professions (medicine, dentistry) have made them the municipality’s elites. Longtime residents of Marikina may be distinguished by their chinito (Chinese-like) features, as many are descended from Chinese migrants who settled in Marikina from the middle of the seventeenth century. As pioneer settlers who control the local economy, they may also be said to dominate or control politics.

Until the early 1970s, the First District was notorious for its many dance halls or cabarets. Long before Ermita, Pasay, and Quezon City became Manila’s red-light areas, Marikina was the red-light district. Marikina was at the end point of the Pasig Line of the American colonial-era tranvia (electric rail) system. Because of the area’s remote location, colonial officials favored placing these entertainment facilities in Marikina instead of the downtown area. Thus, for many young men Calumpang became the mecca for another rite of passage.

Because of its wide-open spaces and proximity to Manila, the Second District (Parang, Malanday, and Concepcion) drew numerous businesses to set up their factories there in the late 1950s and early 1960s. These included Fortune Tobacco Corp., BF Goodrich rubber and tire company, Arms Corp. of the Philippines, Eagle Electric, Holland Milk Products, Goya Chocolate Factory, and Mariwasa Tiles and Ceramics. Purefoods also set up shop, but in the First District. As a result, factory workers from many parts of the country started migrating to Marikina.

At the same time, the Second District’s wide-open spaces attracted another type of business: real estate. Beginning in the late 1960s and early 1970s, developers opened up new subdivisions and low-cost housing projects to solve Manila’s housing backlog. Foremost among them were the Marikina Subdivision, Provident Villages, SSS Village, and Rancho Estate. As newcomers to Marikina, it took some time before residents of these new homes could integrate and organize, first as neighborhood associations and later as a voting bloc. Thus, for a long time Marikina’s local officials almost always came from the First District. Even with a larger voter base, prospective candidates from the Second District were handicapped by having none of the traditional electoral networks or campaign machinery that candidates from the old political families in the First District possessed. This disadvantage ended only in 1992, when Romeo Candazo teamed up with Bayani Fernando to run for congress.

Bayani was no stranger to politics. His father, Gil, had also been the Marikina mayor—from 1947 to 1959. As a young boy, Bayani may have had his first exposure to how Marikina should be run. However, he had another calling. He studied civil engineering at the Mapua Institute of Technology, one of the top engineering schools in the country. Thereafter, he founded his own construction company, BF Corporation, becoming a major player in the construction industry. In the 1970s and 1980s local politics was not an option, as martial rule precluded elections and popular participation.

After the Aquino administration came to power, local elections were introduced in 1987. Bayani decided to try his luck, fueled initially by his boyhood dream to revive the stagnant Marikina River and make it a center for community activities (Damazo 2002). Being a neophyte, he lost to Rudy Valentino, the administration’s chosen candidate. Cory Aquino’s popularity was at an all-time high, and whoever she endorsed was ensured of victory. Valentino’s term, however, was lackluster. Not only did Marikina stagnate, but the town became notorious for a series of heinous crimes, including rape, murder, bank robberies, and extrajudicial killings.

Undeterred, Bayani ran again in 1992, this time campaigning on a platform of “an industrial and government-friendly, happy, working-class community” (Villaluz and Sanchez 2017). Bayani capitalized on his being an engineer, wearing his trademark construction helmet during the campaign, and came up with the catchy battle cry “BF gets it done!” The message worked, and his campaign gained momentum. The people of Marikina were fed up with the incompetence of the previous administration. Bayani’s gung-ho attitude and emphasis on discipline resonated with voters, who handed him a landslide victory. His centerpiece program, the Save the Marikina River Project, also appealed to voters. Unlike grandiose programs or projects that were promised at every election but seemed unattainable, Bayani’s project seemed like a doable one given his experience and expertise. Being a newbie candidate also had its advantages. One was that Bayani dodged the trapo (traditional politician) tag and was even supported by progressive forces, among them the Kilusang Mayo Uno.2) Not having many resources to count on, Bayani forged alliances with several sectors based on his vision to include the business community and the Iglesia Ni Cristo.

II The Marikina Way, 1992–2010

For Bayani, Marikina’s transformation necessitated a strong emphasis on order and discipline. He likened his emphasis on discipline and meticulousness to the “broken windows” theory. As the theory explains, an unnoticed broken window, however small, if left unrepaired shows an uncaring attitude on the part of the house owner. If unchecked, this attitude becomes contagious and spreads to others. In practice, this meant rehabilitating and renovating Marikina’s poor infrastructure to allow discipline and order to set in. Bayani said:

There ought to be law and order to put everything in order, and without it there will be iniquity and worse, anarchy. Order is the key to change and progress. When the order is pervasive, people think and behave with civility and urbanity. There can be urbanity only when order is pervasive. (Fabros 2008, 17)

On many occasions, the new mayor could be seen berating those who disregarded Marikina’s ordinances in public.

To restore order and discipline on Marikina’s congested and chaotic streets, Bayani reclaimed the easement designated for pedestrians from illegal structures, parked vehicles, and vendors. To do this, the city council passed a resolution that classified all materials and illegal structures in public conveyances (streets, sidewalks, riverbanks) as garbage, and therefore apt for disposal (Fernando 2007, 11). With this legal mandate, it became possible to reclaim public spaces and enhance mobility. After establishing the necessary right-of-way, Bayani started concreting and asphalting Marikina’s notorious roads. Later, a standard pattern and color were used to pave sidewalks in the whole city. Bike lanes were incorporated between roads and sidewalks. Next came big-ticket items such as renovating the public market and city hall and setting up a new health center and satellite centers in each barangay, covered courts, new school buildings, and much more. Great attention was paid to Bayani’s pet project—the Marikina City River Revival and Park Project. The river was first dredged of silt and garbage, then aerated to remove foul odor and revive fish stocks. Both banks were developed for joggers and picnickers, and restaurants were invited to set up shop in the newly developed area. This project was so successful that it won many awards and citations and received distinguished visitors, both local and foreign.3)

To keep residents physically fit and active, Bayani redeveloped the Marikina Sports Center. Aside from the full-length tartan-covered track oval, this facility also has an Olympic-size swimming pool, a baseball field, and a football field. Marikina was lucky to inherit this facility from the province of Rizal. Formerly called the Rodriguez Sports Center, the facility was created to host the 19th World Softball Championships in 1971 as well as the inaugural edition of the Palarong Pambansa in 1974. But when Metro Manila was created in 1975, Marikina ceased to be part of Rizal Province and joined the new entity. Rizal lost its premier sports facility, to the advantage of Marikina. Bayani further enhanced the facility by erecting a new building for basketball, volleyball, table tennis, and aerobics and spaces for physical education classes. The track oval is open 24 hours a day, while other sports facilities are closed for only six hours daily.

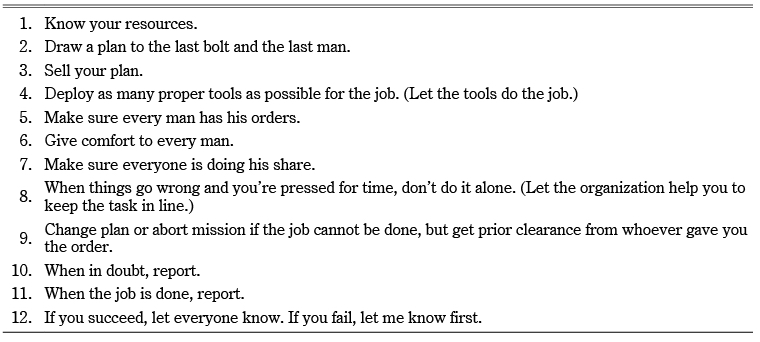

Marikina’s swift physical transformation could be greatly attributed to Bayani’s engineering experience. Unlike other mayors whose education or background was in law or medicine, Bayani knew at once what needed to be done and how to obtain the necessary resources. He applied the principles he used in his company and his work methods to the City Engineering Office (see Table 1). Inefficiency and corruption in government infrastructure projects became things of the past. For the first time, Marikina experienced how it was to be rebuilt as if it was a privately contracted project. In this manner, corporatist practices in the private sector worked well when applied to public service (Tordecilla 1997, 17–18).

Table 1 Bayani’s Guide to Leadership

Bayani also promoted the practices of a clean and green city. Waste segregation was introduced: green bags for compostable materials and black bags for recyclable materials. Specific days were set for which garbage bag was to be collected. Offenders—those who put in the wrong waste material—could expect their garbage to be refused or returned. Students and residents were reminded of Marikina’s strict anti-littering policies so that it became practice for many to hold on to their trash until they saw a garbage can. In one of his reelection campaigns, instead of handing out campaign leaflets Bayani handed out metal tongs in his signature green color with a reminder for people to pick up their own litter. Aside from restoring order and addressing Marikina’s deficient and dilapidated structures, Bayani also focused on a seeming disregard for what old-timers called urbanidad. Resolutions were passed that prohibited spitting, urinating, drinking alcoholic beverages, and strolling around shirtless in public areas (Lorenzo 2007). There was even a ban on hanging out laundered underwear exposed for the public to see.

Bayani’s success in transforming Marikina into a model city was due, to a large extent, on the passage of the 1991 Local Government Code. By granting local chief executives more leeway in managing their cities/municipalities, mayors became in a sense more powerful than the president of the republic. While the power of the purse belonged to Congress and not to the president, at the local level the chief executive had the power to decide where to allocate resources or what projects or programs to include in the budget and implement. In many ways, Bayani was able to use this newfound capability. Another contributing factor in Bayani’s success had to do with Fidel V. Ramos’s election to the presidency. Ramos and Bayani had much in common: they were both methodical and sticklers for detail when it came to planning and execution; they also favored infrastructure development, an admirable work ethic, and commitment to discipline. Even their public image was identical: a folded barong tagalog with a hard hat, denoting the willingness of a public executive to roll up his sleeves and do the spadework, or an image of a hands-on manager.

Local chief executives can deliver more and become electable if they are able to access funds and support from the center. As Alfred McCoy (1994) and Patricio Abinales (1998) have pointed out, while local elites are the supreme authority in their locality, they are also dependent on their relations with the central power or the state for their survival. Eventually, Bayani’s hard work and brand of service, along with the visible improvements he made, caught the attention of Malacanang.

III Public Goods and Civic Virtues

Like the ancient Indian ruler Asoka, who reminded his constituents of Buddhist teachings through the construction of the Rock and Pillar Edicts, Bayani inscribed tenets of his philosophy on sidewalks to remind the people of Marikina of them even after his term ended. Sidewalks were painted red to convey a strong message (see Fig. 2). Among the messages Bayani imparted were the following:

Fig. 2 Sidewalks Are Marked with Reminders or Edicts in the Form of Slogans.

Source: Author’s personal photo.

- Pantay Pantay Kung May Disiplina (Discipline leads to Equality);

- Disiplina Nagsisimula sa Bangketa (Discipline starts at the sidewalk);

- Magbihis ng Angkop at nang Igalang Ka ng Iyong Kapwa (Wear proper attire to gain respect);

- A walkable city is a healthy city;

- Marikina: a bicycle-friendly city;

- Marikina: a city of government and business-friendly working-class people; and

- Work hard, work well, and work together.

While other cities abroad may have used this strategy, it was a novel idea in the Philippines. Not only were the messages original and innovative, they also reminded citizens that the government was always present and watching. As people walked past these messages, the messages became part of their subconscious, reminding them of the city’s rules and edicts. Most important, Bayani was able to convey that there was a public space where there were rules and norms and that public facilities built by the city government were public goods. They were not for individual use but for the common good.

After reaching the maximum allowable three terms in office, Bayani was succeeded by his wife, Marides, who ran Marikina for the next nine years, from 2001 to 2010. Like in Singapore, where Lee Kuan Yew made way for his son to take his place—thanks in part to Goh Chok Tong’s holding the line until Brig. Gen. Lee Hsien Loong was mature enough—Bayani asked his wife to take his post and continue the project he had started. After all, if a woman could continue the succession in running a business corporation or even a revolt (Gabriela Silang) after the death of her husband, why not in public office!

If Bayani’s term as mayor was focused on improving Marikina’s physical infrastructure, Marides’s term was spent on consolidating the gains made by Bayani and making sure the city became sustainable financially and environmentally. Her term in office was made easier by Marikina becoming a city on December 8, 1996 by virtue of Republic Act 8223. Under the Local Government Code, cities have more leeway in running their affairs than municipalities do; they also have a bigger share of the Internal Revenue Allotments (IRA) of the national budget.4) Marides was no ordinary housewife or a pushover. She was the daughter of Meneleo Carlos, one of the most successful local entrepreneurs in the country. Carlos attended Cornell University, where he obtained a degree in biochemical engineering in the 1950s. He set up a business empire focused on the production of fiberglass, resins, polymer, and other industrial products. Like her father, Marides also went to the Ivy League school, where she obtained a master’s degree in business management. With her outstanding education and extensive experience running a corporation, Marides was able to further push the transformation of Marikina by coming up with a management system that set the standard for governance in a highly urbanized setting. For her efforts, she was nominated as one of the finalists for World City Mayor in 2008. By the time Marides completed her three terms in 2010, Marikina had received numerous awards both locally and internationally.

Marides emphasized the concept of a healthy city. A healthy city is not only clean but has the facilities for an improved quality of life, such as parks, sports facilities, water treatment plants, a waste management facility, etc. A healthy city is one that promotes a healthy lifestyle. With the city’s motto of “A healthy city leads to a sustainable city,” the initial intention was to rehabilitate the city to make it livable and habitable. But the concept evolved to financial viability, ensuring the city’s standards could be maintained with sufficient funding (Vera 2008, 29). Marikina City provided each family with a health passport—a family record that contained details of each family member’s check-ups, vaccinations, and dental examinations and the nutritional services available at the city health office.

Because of Marides’s corporate background and experience in running a manufacturing firm, her natural inclination was to lead an organization and deal with partners and customers whose satisfaction she had to always take into consideration. Thus, her attitude toward public office was not to shake hands and dole out money but to manage city hall and its employees like a corporation—to deliver its products, which consisted of basic services (Siao 2013). Because Marikina residents were her clientele, she treated them as customers. While customers may not always be right in such a setting, they can certainly demand quality service. And this Marides was keen to fulfill. The mayor instituted a number of feedback mechanisms to gauge the delivery of basic services in terms of courtesy, timeliness, and efficiency. She instituted a “one-strike” policy, meaning city employees could face disciplinary measures or even dismissal if they were subject to complaint. Another aspect of corporate management that she carried into public service was the delegation of powers, making sure that everyone became part of a team and did his or her job.

Marikina’s success under the leadership of the Fernandos may also be attributed to the continuity of the programs and leadership style. What had been started during Bayani’s early years was continued and built upon so that there was ample time for the initiatives to take root and develop. Likewise, the drive for excellence and innovation among employees, and the culture of discipline and urbanity among citizens, became established. A set of doable programs and projects, rootedness in the community, a middle-class constituency that was articulate and politically active, and a system of elections every three years added to the equation. Bayani and Marides Fernando invested heavily in empowering Marikina City by strengthening the administrative and field support services of the city, the pillars that made up the delivery of basic services and the long-term viability of the local government unit (LGU), by allocating sizable funds for capital goods (engineering equipment, riverboats for rescue and relief operations, and ambulances), infrastructure (medical, educational, and sports facilities), as well as capacity building and training. The husband-and-wife team invested in strengthening the capability of Marikina in the long term. While political will has always been mentioned as a key factor in effectively running LGUs, there are limits to what political will can achieve if the foundation is weak and wanting. An analogy may be made to a cart driver beating an old and weary horse. Political will may be important, but so is the means or the capability to deliver services.

IV Policy Coalition through Common Interests

Marikina City is unique in having a statue in honor of a known Communist, Filemon “Ka Popoy” Lagman (see Fig. 3). Moreover, Marikina presents a unique case where labor unions, businesses, and the LGU formed an alliance and institutionalized a tripartite body. If relationships between these groups were marked by enmity in the past, what brought them together was quite unexpected—the ill effects of globalization. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the processes of globalization were being felt more and more in the Philippines. Liberalization, or the entry of foreign goods and services, and the need for greater competition to do away with inefficient, expensive services were becoming the norm. Local businesses that benefited or were protected by the previous trade regime became wary and disturbed. In Marikina, the moribund shoe industry now faced the prospect of demise and extinction. This fear was not without basis. The national government, through the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI), favored an approach based on comparative advantage. Like Darwin’s concept of survival of the fittest, industries that could not keep up with the competition would naturally wither away. What the DTI favored was the so-called One-Town-One-Product approach. Instead of pouring resources into unprofitable industries, the DTI advocated for specialization, concentrating on products that the town could excel in producing. For Marikina, this meant closing the century-old shoe industry and opening up new business ventures.

Fig. 3 A Statue Dedicated to Filemon “Ka Popoy” Lagman, Former Labor Leader, Communist Cadre, and Co-founder of the Partido Manggagawa (Workers Party), Who Worked Out an Amicable Relationship between Business, Labor, and the Marikina City Government during Bayani’s Term.

Source: Author’s personal photo.

Note: The statue is undergoing repainting, obscuring the hammer-and-sickle emblem.

Globalization has its underside too. Opening windows may let in fresh air, but it also lets in flies and other insects. In the case of Marikina, smuggled and dirt-cheap Chinese-made shoes, some as cheap as 60 pesos a pair, started flooding the market. This caused deep concern not only among business owners but also among shoe workers and the Marikina city government. In late 1999, progressive groups wary—or critical—of the ill effects of globalization initiated the formation of the Free Trade Alliance. This group was composed of labor federations, NGOs, advocacy groups like the Freedom from Debt Coalition, members of the academic community (notably from the University of the Philippines’ School of Labor and Industrial Relations), and many other like-minded individuals. It comes as no surprise that the chairman was the notable former Senator Wigberto “Bobby” Tanada, whose nationalist credentials were without reproach. By the early 2000s, a common ground between business and labor had been established and a partnership began to take shape.

This collaboration led to the formation the following year of the Philippine Employment–Labor Social Partnership, Inc. (PELSPI), an advocacy group focusing on economic policies and development. The mechanism instituted by the group was to arrive at a social dialogue among partners. PELSPI attracted big business actors, among them the chambers of commerce and business federations, the Employers Confederation of the Philippines, and Marcos-related industrialists such as Lucio Tan, owner of Fortune Tobacco Corp. Because Meneleo Carlos, Bayani’s father-in-law, was the chairman of one of the big business federations in the country, he became part of the consultative process. Carlos’s influence among businessmen enabled Bayani to bring together concerned business and workers groups to dialogue and achieve industrial peace in Marikina (Mendoza 2018).

The framework for cooperation was capsulized in the slogan “Marikina—Bayan ng Masasayang Manggagawang Kaibigan ng Industriya” (Marikina—home of happy workers friendly to industries). To institutionalize this mechanism, Bayani set up the Workers’ Affairs Office (WAO), which also acted as the secretariat of the tripartite body. In a way, the WAO assumed the role of the Bureau of Labor Relations and the National Labor Relations Commission of the Department of Labor and Employment because any strikable labor issue passed through it first for dispute resolution. A key factor in the success of tripartitism in Marikina may have been Bayani’s pragmatism. As a mayor well rooted in the community, Bayani was able to differentiate the different levels of radicalism within the labor movement, and identify which among these he could speak to and negotiate with. He did not meddle directly in labor problems. Rather, he let the WAO handle them. He may have been dictatorial in other aspects, but with this tripartite body Bayani consulted first before making a move, even if his decisions did not please the business and labor sectors. In the end, Bayani saw the importance of a cooperative labor sector when it came to attaining industrial peace, a key ingredient for a business-friendly environment (Magtubo 2018).

In the same manner, labor also demonstrated pragmatism in dealing with business and the Marikina city government. Labor groups belonging to the Sanlakas/Bukluran ng Manggagawa/Partido ng Manggagawa were open to negotiation and compromise at the shop (factory) level even if they positioned themselves as radicals at the national level. By working with businesses and the LGU, they received support or resources for mobilization, education, organizing, and other purposes (Magtubo 2018). Being pragmatic himself, Bayani did not interfere with, or oppose, the radical posturing of labor groups at the national level so long as they made Marikina peaceful.

V What Is Local Is Not Always National

All politics is local! So goes the famous dictum describing politics in the Philippines. This may be a truism, as the efforts of the Fernandos to replicate their success in local governance at the national level did not meet with the same level of success. If policy coalition was a factor in Marikina’s transformation, the same could not be said at the national level. On the contrary, Bayani’s projects and programs for the metropolis were met with resistance and hostility. Clearly, the constituency at the national level was so diverse that a minimal amount of consensus among stakeholders could not be reached. Furthermore, interest groups opposed to his plans for change gravitated toward each other and formed a strong lobby against his policies. The same may be said of the teaming up between Richard Gordon and Bayani Fernando as presidential and vice-presidential candidates in the 2010 elections. Despite showcasing the successes of both Olongapo and Marikina Cities, the team fared badly when the election results came in.

Because of Bayani’s success in Marikina’s transformation, he was appointed chairman of the Metropolitan Manila Development Authority (MMDA) in 2001 by President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo. There were high expectations from residents and the business sector for him to turn Manila into a clean and orderly metropolis. As soon as Bayani assumed office, he undertook almost exactly the same projects and approach he had in Marikina, naming it Metro Gwapo (Good-looking metro). In theoretical terms, Metro Gwapo aimed to increase the metropolis’s livability by achieving safety, efficiency, accessible amenities, and pleasant surroundings. In practical terms, the project meant no obstructions, no litter, no decay, no diseases, no stink, and no discourtesy (Lopez 2007, 18).

As in Marikina, what Bayani wanted to do right away was to clear the metropolis of illegal settlers, sidewalk vendors, grime, and crime as well as rebuild the city’s waterways and infrastructure. Clearing operations targeting sidewalk vendors and illegal settlers near waterways became common, much to the consternation and anguish of those affected (Kusaka 2017). U-turn slots, separate bus lanes, concrete barriers separating private from utility vehicles, and traffic constables in uniform dotted the streets of the metro. In addition, much of the signage bore the color pink, a reminder to residents to bring the metropolis to the pink of health.

Bayani’s close association with the president enabled him to acquire additional funds to undertake projects. There was a command center to monitor traffic, the recruitment of more traffic enforcers, the acquisition of more equipment to support operational requirements, the widening of main thoroughfares to ease traffic congestion, the dredging of heavily silted rivers and waterways, the operationalization of pumping stations to mitigate flooding, and even the establishment of motels for employees and stranded commuters in need of short-term lodging (Lopez 2007).

Yet, after several years in office Bayani was able to achieve only a modicum of success in his planned vision for the metropolis. As expected, resistance from street vendors and urban poor in public conveyances was reported vociferously in the media. The negative image created of Bayani (a dictator, heartless, anti-poor, and a tyrant) would impact him later when he ran for national office (Kusaka 2017). The biggest stumbling block to Bayani’s vision, however, came from the mayors themselves. Apprehensive that the reforms being initiated by Bayani would impact on their constituents and governance (traffic, garbage collection, etc.), Metro Manila mayors resisted by insisting that the role of the MMDA was consultative and that, unlike them, the chairman was not an elected official, did not have the people’s mandate, and thus could not force them to obey.

Unlike many local politicians, Bayani was a loyal member of the Lakas-NUCD, the party of Presidents Ramos and Macapagal Arroyo. When Joseph Estrada won as president, Bayani did not switch parties even though the former San Juan mayor derided Lakas-NUCD members. This party loyalty, along with Bayani’s efficient and effective leadership, endeared him to President Macapagal Arroyo. Like many politicians, however, Bayani did not hide his desire to secure national office in the 2010 elections. He believed that he possessed the attributes of a leader: experience, vision, and commitment. Unfortunately for him, his chosen party had other plans. Because Bayani was not considered winnable, the party chose instead the young, energetic, and charming Defense Secretary Gilbert Teodoro, even though he was not a party member. During the Lakas-NUCD national convention, Bayani was not even considered as Teodoro’s running mate.

The party’s decision angered Bayani, and he left Lakas-NUCD permanently. He teamed up with Gordon, former Olongapo City mayor, in the 2010 elections and ran as his vice-presidential candidate. Before Marikina’s transformation under Bayani, Gordon had transformed Olongapo into a model city. Gordon also managed the transformation of the former Subic naval station into an economic zone and freeport. The team capitalized on their success stories. They chose the catchy name “The Transformers” and projected an image of strong leadership and political will. Timing, however, was not on their side. Because they exhibited qualities that were so close to the unpopular president’s, their candidacy did not resonate with voters’ preference. The pair lost miserably: Bayani ended up fourth out of eight candidates.

Aside from the negative publicity he generated as MMDA chairman, Bayani fared badly because he was pitted against veteran Senators Loren Legarda and Mar Roxas as well as Makati Mayor Jojo Binay, a longtime human rights lawyer. When asked during political debates about national issues such as foreign policy, economy, and security, Bayani could not respond. Not only did Bayani lack the eloquence of his rivals, the debates exposed his lack of knowledge beyond local concerns. Unfortunately for him, Bayani showed voters that while he was well versed in running a city, the same could not be said if he took on national office. During the televised debates, all Bayani could muster was the appeal to discipline and obedience to authority, demonstrating to voters that his perspective was very localized. While attention to detail in running a locality proved its worth when he was mayor, the same could not be said should he be elected as vice president. In short, he was not qualified for the position he aspired to.

Bayani’s failed run for national office coincided with Marides’s exit after reaching her three-term limit as mayor. Shortly after, the couple returned to the private sector, focusing on their construction enterprise. Their only child did not show any interest in entering politics, thus ending the Fernandos’ venture into politics.5) This case is atypical of familial politics or dynastic rule in Philippine politics (Quimpo and Kasuya 2010). While many experiences of familial politics in the Philippines have been marked by inequality, poverty, and even being contrary to good governance, Marikina’s is quite the opposite.

Conclusion

There are a number of possible reasons for why the Fernandos’ mayorship did not fit the pattern of political dynasties or dynastic politics. As discussed above, their ascent to office was not inherited but won through elections. Their successors have not necessarily enjoyed cooperative relations with the Fernandos while maintaining the legacy of reform policy. Second, no other member of the family ran for office to continue the Fernandos’ hold on power. Third, while dynasts usually inherit their position and come to public office unprepared or unqualified, the Fernandos brought with them technical and managerial skills as well as long experience in the private sector. It may seem that the Fernando brand of leadership became a thing of the past when the husband and wife left local politics. But the standards set by them became the benchmark by which to measure an aspiring local chief executive (Gregorio-Medel et al. 2007). In the end, the people of Marikina would not expect less from their mayors, expecting them to provide services similar to those that they had received from the Fernandos, if not better.

Marikina’s success may also be attributed to the support the residents gave to the Fernandos. Bayani’s style of leadership resonated well with the mindset of Marikina’s residents. It may be argued that Bayani’s management style appealed to the city’s mostly middle-class residents. For a long time, political leadership and control came from longtime residents of the First District: they dictated the values to the new arrivals in the city. So when Bayani pitched the concept of urbanidad, it was not an alien idea. Rather, it was a common and respected value that the old residents took to heart. Thus, Bayani’s campaign regarding urbanidad was simply a reiteration of an old value in an old setting that was being eroded by rapid development and an influx of migration.

It is doubtful whether this approach or appeal to civility can take root in the much bigger cities of Metro Manila. The departure of old-time residents and the massive influx of migrants from rural areas settling in blighted communities have produced a different demographic, shifting government spending away from capital goods to more basic services. The wide disparity in economic standing and orientation has created a very diverse constituency that makes governance complicated. In contrast, Marikina is still the small municipality that it once was and has a large degree of homogeneity in civic norms. In this sense, the Fernandos were able to govern for a long time and enable Marikina’s transformation because of the consent of local residents.

Accepted: December 15, 2020

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to acknowledge the generosity and kind consideration of Prof. Takagi Yusuke and the Graduate Research Institute for Policy Studies (GRIPS) for the opportunity to collaborate on this project. The author likewise acknowledges the support given by the secretarial staff and resource persons who made this project possible and gratifying. The author would like to dedicate the paper to Ms. Corazon dela Paz Forteza, former librarian and head of the Personnel Department who died while serving the City of Marikina.

References

Abinales, Patricio N. 1998. Images of State Power: Essays on Philippine Politics from the Margins. Diliman, Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.↩

Adamos, Pompeyo C. III. 2007. Local Chief Executive’s Political Leadership and Private Voluntary Organization’s Participation: A Case Study of the “Save the Marikina River Project.” Master’s thesis, Ateneo de Manila University.↩

Damazo, Jef. 2002. Bayani the Hero. http://www.archives.newsbreak-knowledge.ph/2002/07/22/bayani-the-hero, accessed June 12, 2017.↩

De la Paz, Amelia. 2017. Interview by Meynardo P. Mendoza, November 8.↩

Fabros, Dann. 2008. The Marikina Way. Philippines Free Press, August 2, pp. 16–22.↩

―. 2006. Pursuit of Excellence. Philippines Free Press, December 2, pp. 14–24.↩ ↩

Fernando, Bayani. 2007. Doing the Right Thing in Marikina. Biz News Asia 5(41) (November 12–19): 10–22.↩

Gregorio-Medel, Angelita Y.; Lopa-Perez, Margarita; and Gonzalez, Dennis T., eds. 2007. Frontline Leadership: Stories of 5 Local Chief Executives. Quezon City: Ateneo School of Government; Makati City: Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung.↩

Kusaka Wataru. 2017. Moral Politics in the Philippines: Inequality, Democracy and the Urban Poor. Singapore: NUS Press; Kyoto: Kyoto University Press.↩ ↩

Lopez, Antonio S. 2007. Super Governor: He Is Rebuilding Metro Manila. Biz News Asia 5(41) (November 12–19): 18–21.↩ ↩

Lorenzo, Isa. 2007. Marikina’s (Not-So-Perfect) Makeover. iReport, Good (Local) Governance. January 12. Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism. https://old.pcij.org/stories/marikinas-not-so-perfect-makeover/, accessed January 23, 2021.↩

Magtubo, Renato. 2018. Interview by Meynardo P. Mendoza, Marikina City, January 8.↩ ↩

Marikina City. 2020. Marikina City: The Shoe Capital of the Philippines. http://marikina.gov.ph/webmarikina/Our-City.html, accessed February 29, 2021.↩

McCoy, Alfred, ed. 1994. An Anarchy of Families: State and Family in the Philippines. Loyola Heights, Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.↩

Mendoza, Maria S. 2018. Interview by Meynardo P. Mendoza, Quezon City, January 6.↩

Ocampo-Salvador, Alma M. 1997. Local Budgeting, A Closed-Door Affair: The Case of the Municipality of Marikina. In Demystifying Local Power: Perspectives and Insights on Local Government Processes, edited by Letty C. Tumbaga, pp. 29–42. Quezon City: Ateneo Center for Social Policy.↩

Palisoc, Marilou P. 2000. Improving Local Fiscal Administration through the 1991 Local Government Code: The Case of Marikina City. Master’s thesis, Ateneo de Manila University.↩

Quimpo, Nathan Gilbert; and Kasuya Yuko. 2010. The Politics of Change in a “Changeless Land.” In The Politics of Change in the Philippines, edited by Kasuya Yuko and Nathan Gilbert Quimpo, pp. 1–20. Manila: Anvil Publishing.↩

Siao, Felyne. 2013. Because We Want to Make Marikina Even Better. Rappler. March 19. http://www.rappler.com/nation/politics/elections-2013/24107-because-we-want-to-make-marikina-even-better, accessed July 26, 2016.↩

Tordecilla, Roberto B. 1997. People’s Participation in Crafting Award-Winning Local Government Programs: Local Planning in Marikina and Irosin. In Demystifying Local Power: Perspectives and Insights on Local Government Processes, edited by Letty C. Tumbaga, pp. 5–28. Quezon City: Ateneo Center for Social Policy and Public Affairs.↩

Vera, Millie. 2008. The Power to Transform. New Vanity Magazine 15(3): 19–30.↩ ↩

Villaluz, Vanessa C.; and Sanchez, Joseph C. 2017. Innovations in City Development: The Marikina Experience. In Transforming Local Government, edited by Ma. Regina M. Hechanova et al., pp. 73–85. Quezon City: Bughaw (Ateneo de Manila University Press).↩

1) Interview with Amelia de la Paz, November 8, 2017.

2) Before the split within the Communist Party in the Philippines.

3) For a detailed discussion on the topic, see Pompeyo C. Adamos III, “Local Chief Executive’s Political Leadership and Private Voluntary Organization’s Participation: A Case Study of the ‘Save the Marikina River Project’” (master’s thesis, Ateneo de Manila University, 2007).

4) For studies on Marikina’s fiscal administrative and budgeting systems, please see Ocampo-Salvador (1997) and Palisoc (2000).

5) In the 2016 general elections Bayani ran for a congressional seat in Marikina and won, representing the city’s First District in Congress.