Contents>> Vol. 11, No. 2

The Struggling Aristocrats? Noble Families’ Diminishing Roles after the Splitting of Tana Toraja Region

Ratri Istania*

*NIPA School of Administration (STIA LAN Polytechnic Jakarta), Jl. Administrasi II Pejompongan Jakarta Pusat DKI Jakarta 10260, Indonesia

e-mail: ratri.istania[at]stialan.ac.id; ristania[at]gmail.com

![]() http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7446-1414

http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7446-1414

DOI: 10.20495/seas.11.2_195

How did the splitting of the Tana Toraja region in 2008 challenge the local aristocrats’ dual role in adat and politics in the new North Toraja? Why and how did these aristocrats fail to secure their dual role after the 2015 election? After 32 years of the New Order regime, adat rights were finally revived through the Return to Lembang regulation in 2001. The law channelled noble families’ hereditary rights back to local political affairs. However, the splitting of the region, or pemekaran daerah, opened a new venue for power contestation in North Toraja District. Following the second direct local head election in 2015, noble families’ role in politics gradually diminished due to the participation of a growing class of wealthy and politically strong non-traditional elites in democratic elections. Using interviews, triangulated with government archives and media resources, I extend previous studies of North Toraja aristocrats’ advantage to reassert their dual role—in adat and politics—after the region’s split. I argue that decentralization policies initiated through democratic elections came with high risks for aristocrats to again secure their traditional hereditary rights. This study was inspired by Lee Ann Fujii’s (2014) accidental ethnography study based on stories and unplanned encounters in Bosnia, Rwanda, and other places. It aims to contribute to an understanding of decentralization and indigenous minority groups’ survival in Indonesia’s multicultural society.

Keywords: decentralization, regional splitting, aristocratic role, hereditary rights, North Toraja, Indonesia

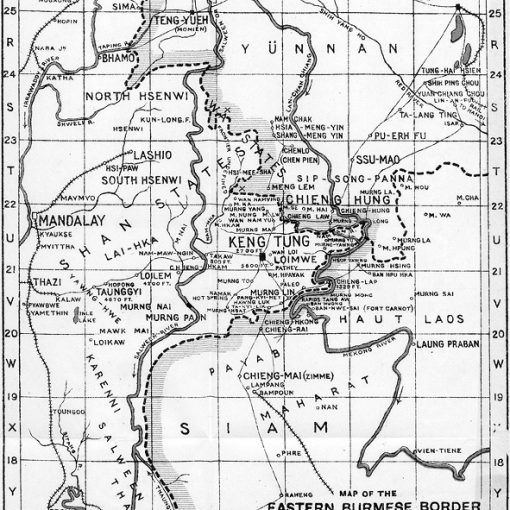

How did the splitting of the Tana Toraja region in 2008, into Tana Toraja and North Toraja Districts, challenge local aristocrats’ dual role in the new North Toraja? Why and how did aristocrats fail to secure their dual role—in both adat and politics—after the 2015 election? Following the breakdown of Suharto’s authoritarian regime in 1998, the World Bank advocated for an aggressive decentralization reform throughout the country. One of the many decentralization-related policies—Government Regulation 129/2001 on the Requirements and Criteria for the Creation of a New Administrative Unit, or pemekaran daerah—allowed regions to split into autonomous regions and territories. This culminated in a sudden proliferation of territories across the nation. As mentioned earlier, the region of Tana Toraja was split in two in 2008, leading to the creation of the new Toraja Utara (North Toraja). The region now has two separate governments and administrative boundaries. However, the people remain connected to their 32 original adat1) jurisdictions.

Decentralization also introduced democratization. Many localities celebrated the transformation from an authoritarian regime to a democratic, decentralized one as liberation from central government control. Torajans live on Sulawesi, the fourth largest island in Indonesia, where noble or aristocratic bloodlines remain predominant. They are found mostly in Tana Toraja and North Toraja, but also in neighboring districts. The Torajan aristocrats’ privileged status is embodied within traditional practices such as land distribution, feasts, wedding ceremonies, and gift-offering rituals (Schrauwers 1995). The regional split, or pemekaran daerah, brought the aristocrats new hope of their dual role in adat and politics being restored, and the first direct election in 2010 did help them reassert themselves in both roles.

As is showcased in this study, the Tana Toraja government passed Regulation 2/2001 on the Return to Lembang2) in 2001 to replace the uniform desa or village structure imposed by the New Order regime. Under this new regulation, anyone could be a candidate for the head of a lembang (smaller administrative unit). In addition, the statute provided aristocrats with room to bring back their adat influence (hereditary rights) to politics and government affairs. Unfortunately for the aristocrats, this lasted only until 2010, when their dual position was challenged through a democratic election.

The direct election for bupati (regent) in 2010 challenged the aristocrats’ dual position. The caretaker bupati, the aristocrat Y. S. Dalipang, ran independently. He lost to other aristocrats from Papua who had a vast political network and were backed by the previous South Sulawesi provincial government. In 2015 the aristocratic family from Ke’te’ Kesu’ fully supported Kalatiku Paembonan, a noble himself, and Yosia Rinto Kadang, a successful Papua-based businessman acting as the largest campaign contributor during the 2015 election. Kalatiku’s easy win was followed by the dramatic demotion of 18 government officials. Even the bupati, who was of noble blood himself, seemed helpless in preventing the massive demotion of high-ranking officers to government officers without an assigned position (Interview with demoted North Toraja officer 1, 2017).

Using accidental ethnography (Fujii 2014), I extend previous studies of the North Toraja aristocrats’ dual role—in adat and politics—and address the challenges facing North Torajan aristocratic leaders after the 2015 election for bupati. Previous studies confirm the advantages of regional splitting for aristocrats seeking to reassert their role in politics (Li 2001; Roth 2007; Tyson 2011; Sukri 2018). However, the evidence in this study suggests the opposite: the splitting of the region diminished the dual role of aristocrats within society.

For analytical purposes, I conducted series of in-depth interviews in addition to a careful examination of government archives and media sources. I argue that North Torajan aristocrats’ struggles to maintain their dual role with the advent of democratic elections weakened their attempts to preserve their traditional hereditary rights under the new decentralized system of government. Ultimately, the diminishing presence of traditional elites in policy-making bodies, local government, and parliament crippled the elites’ means of securing funding and maintaining their centuries-old adat and tourism objects. Thus, this study contributes to the discussion of decentralization and minority groups’ survival in Indonesia’s multicultural society.

Literature Review

Territorial Autonomy in a Decentralized Indonesia

The 1997 Asian financial crisis impacted most Asian economies. As a result of the crisis, Indonesia had to give in to the World Bank’s prescription for “big bang” decentralization reforms.3) The reforms democratized the country but divided it into additional regencies and provinces (Snyder 2000; Hadiz 2004; Fitria et al. 2005). The divisions further accelerated the growth of identity-based groups aiming to pursue autonomy (Rizal 2012). The issuance of Government Regulation 129/2000 and its revision, 78/2007, on the Requirements and Criteria for the Creation of a New Administrative Unit broke the sub-national government structure into four tiers—province, district/regency (kabupaten), subdistrict (kecamatan), and village (desa) (Booth 2011). From 1999 to 2001 the number of provinces increased dramatically, from 26 to 31, while the number of regencies rose from 292 to 341. Between 2012 and 2014, the number of regencies almost doubled in number to 514, and the number of provinces increased to 34. In 2019, at least 524 regencies were recorded in the Komite Pemantauan Pelaksanaan Otonomi Daerah (Regional Autonomy Watch) (Indonesia, Setkab 2019).

Decentralization policy is formulated to, among other actions, split a territory into smaller autonomous administrative units. Decentralization is also a devised strategy for Territorial Autonomy (TA) in order to break the concentration of power in one dominant identity-affiliated group (i.e., an ethnic or religious group). Across nations, decentralization has been widely credited with increasing public expenditure and providing better services for the people (Tiebout 1956; Fitria et al. 2005; Grossman and Pierskalla 2014). Decentralization generally takes two forms: vertical and horizontal. Both processes include the substantial transfer of political, economic, and administrative power from the central administrative unit to a local one—province, district, or subdistrict. While regional splitting has often been perceived as interchangeable with decentralization, each has different characteristics and consequences within a locality.

On the one hand, decentralization has been associated with a vertical process in which there is a delegation of authority from the central government to lower-level government units (Litvack et al. 1998; Falleti 2005). Among the various forms of delegation, political decentralization provides local governments with a significant amount of decision-making power that is intended to serve local needs (Berger 1983; Fox and Aranda 1996; Litvack et al. 1998; Treisman 2007). Advocates of decentralization view a decentralized system as one that leads to a more efficient provision of public goods to the people (Tiebout 1956). Under a decentralization arrangement, the government works better in more densely populated districts while also increasing the people’s welfare (Pierskalla 2016). However, the ongoing policy debate on decentralization and government efficiency depicts the ambiguity of reforms in various developing countries from sub-Saharan Africa (Asiimwe and Musisi 2007; Grossman and Pierskalla 2014) to Southeast Asia (Fitria et al. 2005; Lewis 2017). Pessimists argue that decentralization policies do not improve either governance or service delivery (Bardhan and Mookherjee 2006).

On the other hand, regional splitting has been connected with a horizontal process that involves “a large number of local governments splitting into two or more units over a relatively short period” (Treisman 2007; Grossman and Lewis 2014). The split mainly involves a territorial division that is not directly related to the power distribution and authority argument described in vertical decentralization. Thus, regional splitting is a TA strategy that considers the quantity and size of government units. Since the mid-1990s, the breakdown of authoritarian regimes in ethnically divided societies in Southeast Asia, including Indonesia, has been followed by a dramatic increase in the number of territorial units (i.e., districts and provinces). This TA strategy has been prevalent also in developing areas such as sub-Saharan Africa, where half the countries have increased their number of local administrative units by about 20 percent (Grossman and Lewis 2014).

The logic of regional splitting is different from that of an ethno-federal arrangement. Instead of providing ethnic groups with a separate autonomous territory or allowing them to secede from their mother country, unitary states pursue regional proliferation to close the gap between the government and the people. For example, district splits bring the government “closer to the people” and promote more responsiveness and accountability (Tiebout 1956; Pierskalla 2016). In addition, establishing homogeneous smaller units creates better opportunities in an ethnically diverse society for local people to organize and manage their collective action (Pierskalla 2016; Bazzi and Gudgeon 2021).

Studies on Indonesia’s decentralization offer conflicting theoretical analyses on the significance of TA implementation (Ganguly 2013; Mohammad Zulfan Tadjoeddin et al. 2016). Some suggest that the rapid regional splits set the stage for identity-affiliated groups to compete for access to political power and economic resources; one way of competing was through contesting local elections (Snyder 2000; Hadiz 2004). Other studies indicate that decentralization may promote conflict within a diverse population (Van Klinken 2007; Wilson 2008; Pierskalla and Sacks 2017; Bazzi and Gudgeon 2021). A close investigation of regional elections in Maybrat regency, West Papua Province, revealed political candidates’ likelihood of using ethnic identity (based on territory, class, and blood lineage) as an electoral strategy to appeal to constituents. However, this strategy frequently resulted in long-standing conflicts among groups with different affiliations aiming to win the election (Haryanto et al. 2019). Meanwhile, one study found that regencies with greater ethnic homogeneity were likely to have reduced communal conflict (Pierskalla 2016; Bazzi and Gudgeon 2021). Other studies have revealed that new homogeneous regencies with greater polarization are likely to experience more violence (Montalvo and Reynal-Querol 2005).4) According to Samuel Bazzi and Matthew Gudgeon’s study (2021), districts with a more homogeneous population are likely to be more stable after a split than heterogeneous ones. However, no single territory is populated with only one homogeneous group. There is always a tiny fraction of minority groups within the bigger group. In this connection, Bazzi and Gudgeon also state that a district with greater polarization among ethnic or identity groups has a greater probability of engaging in an identity-led conflict. Polarization refers to a situation in which one group can identify themselves as different from other groups (e.g., Hutus and Tutsis in Rwanda; Bodos and non-Bodos in India). The greater polarization means that one group can tell that they are very different from others.

To understand the underlying cause of a conflict arising from ethnic identity, scholars must examine the intricacy of local historical backgrounds and the social processes behind the contestation of power transformation (Peluso and Watts 2001). Sometimes the tension between groups is simply to gain adat power over a depleting resource (Henley and Davidson 2008). However, other deeper causes, such as ethnic rivalry, may push a group to assert its domination over other groups. Democratization provides the group with leverage to win executive government control over the desired territory and natural resources (Crystal 1974; Aspinall and Fealy 2003; Roth 2009).

Toraja’s Social Structure and Governing Systems

Prior to its split in 2008, Toraja was a large regency in South Sulawesi Province’s highlands. It was inhabited largely by a minority ethnic group, the Torajans. After the split, Tana Toraja District—the government and agricultural center in the Toraja area—has an almost homogeneous population, with 87.51 percent Torajans. Meanwhile, 94.7 percent of the North Toraja population is accounted for by the Torajan ethnic group (Evi et al. 2015).

However, the Torajans form a minority group within South Sulawesi Province’s predominantly Muslim population. After the 2008 split, the ethno-religious Torajan Christian group continued to dominate in Tana Toraja and North Toraja, in a nation that is 87 percent Islamic (Indonesia, BPS Sulawesi Selatan n.d.). Few Torajans maintain the practices of their ancient religious heritage, Aluk to Dolo or “ancestor’s guidelines” (Sukri 2018).5) While Torajans generally adhere to adat customs, their struggles to reclaim adat rights are long overdue. Since 1993, the movement for a return to the lembang system has established a connection with global networks calling for the government’s awareness of political rights and protection of the adat community (Tyson 2011).

Before the splitting of their region, the Torajans lived in a hierarchical structure based on family connection, age, wealth, and occupation under 32 adat jurisdictions. In precolonial times they were divided into three strata: the aristocracy, or puang or to parenge’; ordinary commoners or to buda, to sama; and slaves or to kaunan (Adams 2006). Their status was primarily assigned by birth. The noble families lived widely spread apart in Toraja’s mountainous terrain and often engaged in rivalries, even warfare, with neighboring villages. The rivalries ended with the imposition of Dutch colonial rule, and the noble houses were forced to unify in 1906 (Bigalke 1981; 2005; Adams 1997; Nooy-Palm 2014). The Dutch colonial government found it easier to control the sparsely populated areas in the northern Toraja region by centralizing the leadership under the largest tongkonan6) house due to its significant share of the population (Interview with a Papua-based North Toraja businessman, 2017; Sukri 2018).

However, Toraja’s governing system is not monolithic and straightforward. There are at least three observed governing adat systems in three regions. The first is a highly feudalistic system in Tana Toraja. Tana Toraja’s social structure is hierarchical, with three tallu lembangna (kingdom alliances)—Mengkendek, Sangalla, and Makale—that preserve feudalistic governing traditions even in current times. In addition, noble families in Tana Toraja, called puang, lead society in both adat and government.

The second system is less feudalistic: often referred to as demokrasi terpimpin or Guided Democracy, it applies to the political arrangement of North Toraja. The reference to Sukarno’s demokrasi terpimpin to characterize North Toraja’s governing system does not necessarily relate to the 1950s–1960s era of Sukarno’s single-strongman leadership.7) For North Toraja’s noble families, it is merely the simplest way to describe a system of organization between the smaller houses and the largest house under the principle of equality (Interview with a Papua-based North Toraja businessman, 2017).

The final governing system, the liberal one, characterizes the free western Toraja people who are ruled by the adat elder called Makdika (Muhammad Fadli et al. 2018). In general, all noble houses and their leader, Ambe’ or To parenge’, enjoy a similar status and voice.

The three types of governance system discussed above (feudalistic, less feudalistic, and liberal) determine the interaction between local aristocratic leaders and their supposed followers, the commoners. In the less feudalistic or more democratic system of North Toraja District, ordinary people have more freedom to contest aristocratic power than in the feudalistic Tana Toraja District.

Recently, the social mobility of North Toraja’s non-traditional elites has increased due to acquired wealth (Hollan and Wellenkamp 1996). While the hierarchical structure still applies, the influence of modernization since the 1960s, the growing size of the Torajan diaspora, and the influx of money from those working outside North Toraja District have brought significant changes to Torajans’ perception of the role of aristocrats in society (Volkman 1985). Furthermore, following the fall of the authoritarian New Order regime in 1998, many indigenous groups gained impetus to revive their traditional practices. According to eyewitnesses, adat revivalism became part of a continuing effort to recover adat rights through any available means, legal or otherwise (Benda-Beckmann and Benda-Beckmann 2010).

Decentralization, Democratization, and Dual Role of Aristocratic Leadership

The territorial homogenization policy of Suharto’s New Order era replaced the lembang governance system with a desa or village arrangement. The abolishment of the lembang adat government practice aimed to promote equality in development and modernization (Robinson 2020). However, the traditional elites and aristocratic leaders perceived the village system as endangering their position within the adat communities (de Jong 2013). Therefore, alongside the Aliansi Masyarakat Adat Nusantara’s (Indigenous Peoples’ Alliance of the Archipelago) (AMAN 2019)8) struggle to reclaim the rights of indigenous groups, Torajan aristocrats launched their own movement to revive the lembang system taken away by the Suharto regime. The return to the lembang system gave aristocrats new legal ground to reassert their dual role in adat and government. The lembang structure paved the way for aristocrats to regain their power to control the government.

Law 22/1999 on Regional Autonomy, followed by a return to the lembang policy, resulted in a restructuring of the Tana Toraja territorial units to the adat governing unit or lembang and the administrative unit. This process involved unification or amalgamation of lembang and a reorganization of units at the regency level (de Jong 2013). Suddenly, the adat leaders saw an opportunity to reclaim their dual position in adat and politics by using their influence to intervene, for instance, in the leadership recruitment process.

On January 1, 2001, the movement for a return to the lembang system achieved some success when the Tana Toraja parliament passed Peraturan Daerah Kabupaten Tana Toraja (Local government regulation) 2/2001 on the Return to Lembang. This policy restored the villages’ administrative structure to the lembang system and recognized kobongan kalua, the representative body of 32 adat communities (Klenke 2013). The lembang system consists of a government structure, social and cultural leadership customs, and an adat territorial boundary: a geographical territory wherein populations with similar predecessors share social and cultural customs within a traditional way of government. A lower administrative unit under the lembang structure, the kampung, replaced Suharto’s dusun, a sub-village unit (de Jong 2013).

Besides the restoration of the lembang system of government, a new democratic institution was introduced: Badan Permusyawaratan Lembang (Lembang consultative council), to bridge people’s interest in lembang and lembang’s executive government. Lembang is a system of government that has two features: a representative council and an executive government. Members of the representative council articulate the concerns of ordinary Torajans before the executive government. After the passage of Regulation 2/2001 on the Return to Lembang, council members were still descendants of aristocratic families directly elected by people living in lembang (de Jong 2013). Although the rules did not clearly indicate the privilege of aristocrats to claim elected office or the highest membership status in the representative council, the law channelled the hereditary rights of nobles back to local politics. For example, according to Regulation 2/2001, Article 19: “The establishment and membership of a lembang’s consultative council is hereby decided through consensus among the adat community, social and political organizations, professionals, and youth leaders, as well as other local respected figures within the respective lembang.”

In the highly hierarchical Torajan society, this arrangement led to a strengthening of the aristocrats’ dual role. However, the previous lembang’s non-aristocratic officers did not make it easy for the aristocrats to return to lembang politics. The claim for adat rights disrupted the political patronage secured under Suharto’s 32-year rule at the desa level. Notably, non-traditional elite government officials still felt entitled to control land usage and tenure (see Tyson 2011). Former officials from the desa or village apparatus and its subordinate units opposed the lembang governing system (Noer Fauzi and R. Yando Zakaria 2002; de Jong 2013). In addition, wealthy non-traditional elites—mostly migrants—contested the power of aristocratic families through at least two means. First, they challenged the older aristocrats’ traditions by creating their own lembang. Second, they competed directly for power with the aristocrats by participating in democratic elections (de Jong 2013).

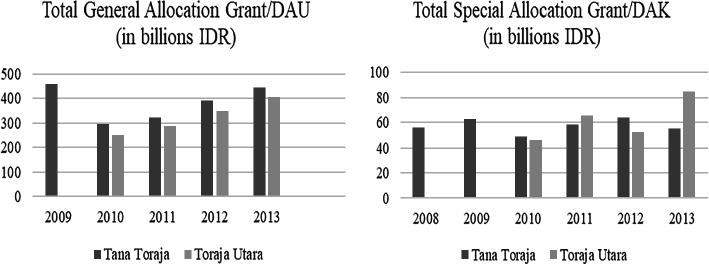

The struggle between Torajan aristocrats and non-traditional elites carried over into the early days of the pemekaran daerah, or the splitting of the Tana Toraja region into North Toraja and Tana Toraja Districts. The division was carried out with the intention of delivering more effective public services to both districts. Law 22/1999 on Regional Autonomy and Law 25/1999 on Inter-governmental Fiscal Transfer resulted in three types of fiscal decentralization. The first transfer was to be a general allocation grant (Dana Alokasi Umum) distributed to all regencies every year based on a calculation of the amount of land and the size of the population. The second was to be a special allocation grant (Dana Alokasi Khusus), an earmarked fund intended to ensure that the new units would follow the national priority program. The third was to be shared taxes that generated significant amounts of revenue.

Tana Toraja, being the original district government headquarters, collected a substantial amount of the revenue generated by North Toraja’s prospective tourism resources prior to pemekaran daerah. This allowed Tana Toraja to build its infrastructure, such as asphalt roads, the bupati’s residence, government and local parliament buildings, and many beautiful and massive monuments.

Under the government regulation on district splitting or pemekaran daerah, the parent district (Tana Toraja) was required to assist the child district (North Toraja) for a fixed number of years (please see Fig. 1). Approximately three years after the split, North Toraja received its own funding from the central government as well as South Sulawesi Province. This amount was calculated based on the amount of the parent district’s budget. The amount would subsequently be prorated based on the population and land area. Resources from either national or provincial fiscal decentralization funds were allocated mostly for infrastructure and restructuring government personnel (Fitria et al. 2005). Amidst the national and provincial transfers, the child district, North Toraja, needed to work harder than Tana Toraja to catch up on its own infrastructure projects by diversifying its sources of income, which were very limited.

Fig. 1 Comparison of Decentralization Transfer between Two Torajas

Source: World Bank INDO-DAPOER Political Economy Data (2019)

Methodology

This study utilizes a series of interviews with individuals from diverse social backgrounds in both regencies—Tana Toraja and North Toraja—and South Sulawesi Province conducted in the summer of 2017. The interviews involved twenty participants: government officials, local parliament members, and aristocrats from both Tana Toraja and North Toraja regencies as well as the provincial level. The interviewees were selected through purposive sampling, with the average time of each interview being one to two hours. Thus, each respondent could be interviewed multiple times. Subsequently, the interview data were triangulated with national news and online news media, government archives, and scholarly publications to better understand the most prominent factors behind the declining role of aristocrats in politics after the 2015 election.

One way to understand the context is by observing and comparing the surroundings, pictures, monuments, buildings, government offices, infrastructure, and people’s interactions in daily life. I followed the accidental ethnography approach suggested in political science research for studying mainly post-conflict situations (Fujii 2014). Unlike lengthy ethnographic fieldwork, accidental ethnography involves the researcher as a participant-observer (Emerson et al. 2011), even if only for a brief period, to watch for any unplanned or accidental events systematically beyond an interview or any other structured qualitative research methods. For instance, I attended the annual Torajan music festival at Ke’te’ Kesu’ to observe the dynamic between the national, provincial, and local North Toraja governments and the aristocratic family member hosting the feast. I also visited burial sites and talked to the cave guide to gain an insight into the possible causes for the lack of support for infrastructure (e.g., decent roads) and basic services (e.g., public restrooms, trash cans). Furthermore, I undertook a two-hour trip with my adviser’s fieldwork family to observe more tourist destinations, had conversations with ordinary Torajans in local cafes, and talked to souvenir sellers on the street and in the market. I engaged in casual conversation with demoted officers, observed newly built tongkonans belonging to wealthy non-traditional elites, attended festivals, and attended a prominent aristocratic leader’s funeral. These engagements were carried out to better understand how the Torajans viewed their identity, the dual role of aristocrats, and the aristocrats’ interactions with people in North Toraja before and after the district’s splitting. Such a research method allows the researcher to gain in-depth contextual knowledge about the nature of groups, boundaries, and perhaps cultures (Wimmer 2013; Fujii 2014). In 2019 I revisited North Toraja to observe mangrara, a ritual to consecrate a tongkonan house. During this second visit, I reconnected with earlier acquaintances to clarify some of my previous findings.

Analysis

Before the Split: Strong Dual Role of Aristocrats

After the enactment of the Return to Lembang legislation in 2001, aristocrats regained their dual role to serve as government officers and in adat. The dual role prompted the aristocrats to exercise their hereditary rights of leadership power within adat and politics. By reasserting their influence in both positions, aristocrats could reap more benefits by securing funding transferred from provincial and national governments. One way of using the funding was to build better infrastructure, maintain adat sites, and strengthen their influence, especially in the case of the non-traditional elites.

Many of them served as high-ranking government officials in various local offices. Their bureaucrat-aristocrat status was evident especially when resolving identity-related issues, such as conflicts due to adat rituals. According to a former subdistrict head, the dual role of the nobility was apparent in a 2004 incident involving two subdistricts separated by the Sa’dan River—Kecamatan Makale Utara on the eastern side and Se’ke and Bontongan villages in Kecamatan Sanggalangi (Landah after the split):

As the story goes, there was a Torajan resident who died in Irian (Papua). The death became a source of conflict between the two groups [though affiliated with the same family, they lived in different subdistricts]. Both groups claimed the right to perform the adat funeral feast. The people who lived in Makale Utara, across the Sa’dan River, felt entitled to conduct the ritual since the deceased was one of their residents. They did not allow the deceased to be transported to the other side, Sanggalangi Subdistrict [where the family burial site was located]. Therefore, the Makale Utara people insisted that the feast had to be performed at their location. Since the rituals usually take two to three days, it just did not make any sense to repeat the same rituals on the other side [at the final resting place for the dead]. This issue escalated into conflict. (Interview with a former camat or subdistrict head, 2017)

While two groups may belong to the same familial community, disputes related to identity (prestige) can often occur during funeral rituals.9) Since the most significant source of income for a Torajan family is generated from the practice of rituals, it is not surprising that the two groups above fought for the right to perform the ceremony. Additionally, the location and event that determine where the money is circulated can be a source of tension between families of similar socioeconomic backgrounds that are separated by administrative boundaries.

The influx of money from the diaspora as well as tourism and revenue from rituals benefit both the population and the government. However, the enormous cost of funerals—which includes building structures, procuring a decorated coffin, building a small tongkonan house for the ceremony, buying food to serve the family and guests, and renting buildings for the lavish funeral service—can amount to more than USD 70,000, or nearly IDR 1 billion. Not surprisingly, families that sponsor funerals sometimes fall heavily into debt.

In the above case, trouble arose when the poorer side of the population, which felt entitled to receive equal benefits from the ritual, was prevented from receiving such benefits because of the territorial divide:

Although the conflict was generally resolved before the split period, some provocateurs could not be dismissed entirely. Those people agitated others to persistently claim the body for the sake of performing the ritual. People from Makale Utara Subdistrict refused to ask for permission from the other side. At that time the bupati, the head of the local police, had given up, and the camat was called out to mediate the conflict. With military backing, the camat met the disputing parties, who had already prepared themselves with blocks and machetes. (Interview with a former camat, 2017)

Acknowledging the presence of the camat or subdistrict head, who was also a renowned aristocrat from the same family as both groups, the feuding parties agreed to resolve their differences. The camat’s approach of using his concurrent positions of bureaucrat and aristocrat to mediate the conflict was practical. The camat successfully united the two groups by proposing funding to build a connecting bridge and install electricity in the more impoverished region in Makale Utara Subdistrict.

After the Split: The Issue of Resource Competition and Diminishing Role of Aristocrats

The elites’ intention behind the splitting of the Tana Toraja region was to provide better public services (i.e., education, health, and identity-related paperwork services) and bring the government closer to the people. However, the changing boundaries worried some of the aristocrats about their adat. The process of splitting Tana Toraja into Tana Toraja and North Toraja, like any pemekaran daerah, had its pros and cons. Different perceptions also arose among the Torajan aristocrats. Following were the thoughts of an aristocratic leader who had also served as a high-ranking official in North Toraja:

Those who opposed the idea of Toraja divided into two argued that the adat and culture were going to be breaking apart. . . . Again, pemekaran [daerah] was intended solely for government administrative purposes, for the sake of service delivery. While some disagreed, the idea continued to persist, and we always tried to approach those who contradicted it. (Interview with a former high-ranking elected government official and aristocrat from North Toraja, 2017)

Immediately after the split, the North Toraja transitional government was led by Dalipang, the then caretaker bupati (2009–10), who was from an aristocratic background. It appeared that the appointment of someone from the nobility signalled a solid reference to the three dearly held principles for selecting a leader: tomaluangan ba’tengna tomasindung mayanna, which can formally be interpreted as kindness, wisdom, and skill/knowledge; sometimes it is construed as defining an individual who is from an upper stratum of society, wealthy, and skillful/knowledgeable (Priyanti 1977).

Law 32/2004 on Regional Autonomy changed the election system into a direct voting system or pemilihan kepala daerah langsung. Thus, regardless of their status in society, people would be able to participate in elections and vote for their favorite candidate without fear of being sanctioned by, for example, adat. However, due to the local-head election, aristocratic leaders expressed widespread concern about the increasing rivalry between traditional elites in North Toraja (Sukri 2018). They were also worried about the disruption of the hierarchical structure in the adat community, which ultimately caused political instability in Tana Toraja and North Toraja Districts.

During the first direct election in North Toraja, in 2010, Dalipang ran as an independent candidate with Simon Liling. Dalipang, an aristocrat from the most prominent house in North Toraja, previously served as an important bureaucrat: the regional secretary, or Sekretaris Daerah, in Tana Toraja’s government. His dual role in the government and adat boosted his confidence to run as an independent candidate. However, he was defeated by a pair of candidates also from an aristocratic background: Frederick Batti Sorring, a former deputy bupati in Asmat, Papua; and Frederik Buntang Rombe Layuk, a former public officer from the Tana Toraja government. Although Frederick Batti Sorring spent most of his life outside Toraja, his vast political network provided him with enough political parties backing him to win the election.

To ensure a smooth election, the governor of South Sulawesi, Syahrul Yasin Limpo, appointed Tautoto Tanaranggina as the caretaker bupati of North Toraja. This was necessary to ensure the smooth transition to the elected bupati, Frederick Batti Sorring, who was officially sworn in on March 31, 2011. However, Tautoto’s appointment was controversial owing to his alleged support of a particular candidate and political partisanship among rank-and-file bureaucrats (Antaranews, July 14, 2010; July 30, 2010). Angered by the widespread violations in the second round of elections, Dalipang and Simon decided to bring the case before the Constitutional Court, or Mahkamah Konstitusi. However, the court rejected their appeal and declared their opponents as the winners in 2011. The status quo of the aristocracy was now being challenged by non-traditional elites under the new democratic electoral system. In North Toraja, the increasing political polarization between the old aristocrat-led administration and the new political newcomers may stem from their different social strata.

After recuperating from his loss in the 2010 election, Dalipang decided to run in the North Toraja House of Representatives election under the banner of the Indonesian Justice and Unity Party, or PKPI, in 2014. However, his political comeback was not successful. Meanwhile, a wealthy Jakarta-based Torajan high-ranking officer, Kalatiku Paembonan, then secretary of the director general of community development from the Ministry of Home Affairs, won the election for local head in 2015. Kalatiku used his vast nationwide political and bureaucratic networks to win the seat of North Toraja bupati. On March 21, 2015, Kalatiku and Yosia Rinto Kadang, a wealthy Papua-based businessman, were sworn in as North Toraja bupati and deputy bupati for the term 2016–21 (later changed to 2016–20).

Dalipang’s losses in the 2010 bupati and 2014 House of Representatives elections impacted his life as well as the careers of aristocrats who followed his career path in the North Toraja government. Dalipang decided to withdraw from public life. Despite having been one of the most influential figures in North Toraja’s pemekaran daerah, he ended up surrendering his dream of building his homeland.

The dramatic story of Dalipang shows how his belief in a bright future of maintaining a dual role as an aristocrat and high-ranking bureaucrat was easily broken. The changing nature of North Toraja’s high politics also rearranged the bureaucratic structure within the government’s rank and file.

The transition from the old parent district, Tana Toraja, to the new child district, North Toraja, also required a significant transfer of government officers to the new region. For those officers who were already residents of North Toraja District, the transfer guaranteed them new positions in the executive and legislative branches. In other words, officers who were originally from North Toraja continue to strengthen their traditional dual role as bureaucrats and aristocrats.

However, the district split came with a cost. A democratic election soon posed a direct challenge to the circulation of elites in the government, once dominated by North Toraja aristocrats (Interview with a Papua-based North Toraja businessman, 2017). Specifically, in the 2015 election, the first local election to simultaneously elect local heads of government—the governor at the provincial level and bupati (regent) and walikota (mayor) at the district/city level—the aristocratic family from Ke’te’ Kesu’ fully supported Kalatiku, a noble himself. However, the deputy bupati was not an aristocrat. He was a successful Papua-based businessman and allegedly the most prominent financial donor during the 2015 election. Afterward, there was a dramatic dismissal of 18 government officials from various ranks. They were replaced by loyal supporters of the current bupati and mainly of the deputy. Unfortunately for them, these 18 high-ranking North Toraja government officials were stripped of their positions while undergoing training in Jakarta to be promoted to levels of higher office. While such incidents are common in politics, this shocking episode still disturbs North Toraja aristocrats, since many of the 18 were affiliated with noble families. These demoted high-ranking officers were made to occupy a small, confined place with only one table and two benches. They sarcastically referred to themselves as occupying “the special place” while awaiting the outcome of their appeal through a class action suit against the sitting bupati (Interview with demoted North Toraja high-ranking official 1, 2017). The suit has not been settled at the time of writing.

Even though the window of opportunity would soon close for members of the nobility to win elections, some of them were hopeful about their future. As one of the demoted high-ranking officials from the North Toraja government said:

Members of aristocratic families are proactive [when it comes to legislative elections]. Since many families live under one big tongkonan, if one figure—the elder—leads one tongkonan, everyone [will follow] the adat leader who holds [the strongest influence] over the tongkonan. (Interview with demoted North Toraja high-ranking official 2, 2017)

According to a prominent adat leader from one of the biggest tongkonans in North Toraja, it was essential to have an aristocratic family member in every level of politics. To provide context, he recalled the past success of two Torajan members of the nobility in the national parliament in guarding the passing of Law 5/1992 on Preservation of Cultural Heritage (perlindungan cagar budaya). The leader continued that the involvement of nobility in revising Law 11/2010 “allowed more severe financial sanctions on those who steal objects. [The previous law] only fined the thief 100 million rupiahs (around USD 7,000), while the total value of the object could be two billion rupiahs (around USD 140,873)” (Law 11/2010 on Cultural Heritage [Cagar Budaya], Article 107).

The changing nature of power contestation after the 2015 election prompted aristocratic leaders to lower the bar for the involvement of their members in government. Despite eyeing the highest elected office, they were satisfied with a few lower government positions in order to assert their aristocratic influence in politics:

Therefore, we encourage members of our family to be involved in politics. [This is important] to safeguard, [for instance] proposed policies. . . . One of us should be government officials, such as camat, lurah, to harmonize the regulation with the adat. (Interview with North Toraja aristocrat leader, 2017)

In this regard, a smaller number of aristocrats working in the government office could also translate into lower funding, for example, to maintain adat sites (i.e., objects, artifacts, tongkonans). An adat leader had to personally find sources of dana abadi (endowment) to maintain the site. Of the tourist contributions, 60 percent went to the adat community and 40 percent to the district government. The recent quest to recover stolen artifacts, such as tau-tau (effigies of the dead), still has a long way to go due to lack of funding and support from the local and national governments. Effigies are adat objects that have substantial monetary value and are meaningful for the adat community as they are believed to harbor the spirits of the dead (Adams 2006). Stolen effigies bring sellers a significant amount of money, primarily in the black market.

Instead of increasing their ability to secure funding through political influence, aristocrats must compete tirelessly with ordinary Torajans who are swiftly adopting modern carving styles (Interview with a local craftsman and souvenir seller, 2017). Though hesitant, they need to bring in money by selling souvenirs and performing in an annual festival in collaboration with the government (Casual conversation with visitors to a local cafe, 2017). Unfortunately, ordinary Torajans’ adoption of new, modernized carving techniques jeopardizes the preservation of traditional carving methods that have been passed down through the generations (Adams 2006). Modern carving techniques are a modification of conventional carving methods in which patterns have been well preserved through generations of noble houses (tongkonans). Traditional carving patterns and styles are considered sacred and cannot easily be passed down or adopted. Aristocrats see the modification of conventional carving patterns and techniques as a direct challenge to their social status.

Discussion

Many studies have been carried out on Toraja after the fall of Suharto’s regime in 1998 and a few years after the split in the region, for example, the crucial period when the return of lembang was just newly introduced in 2001 (Li 2001; Roth 2007; de Jong 2013; Sukri 2018). However, the evidence in this study shows a different narrative regarding the diminishing dual role of bureaucrats-aristocrats within society, which may be due to the different study periods.

This study also attempts to capture the role of the elites both before and after the regional split in 2008. However, it emphasizes aristocrats’ gradually declining role, mainly after the 2015 election for local head. The dual role of traditional elites has continuously been challenged by new elites from a non-traditional background who have been eyeing power. Unsurprisingly, the declining presence of aristocratic families in politics may also have contributed to North Toraja’s failure to fulfill the original intent of the pemekaran daerah, or splitting of the district, in order to bring welfare to the people.

A 2019 study evaluating regional autonomy in Indonesia found that among the 524 regencies that split between 2001 and 2019, North Toraja and Lanny Jaya in Papua Province received the least funding from the national and provincial governments (Siregar and Rudy Badrudin 2019). North Toraja’s impoverished state is a paradox. The beauty of Tana Toraja and North Toraja has been known for centuries, long before the Toraja region became one of UNESCO’s World Heritage nominees (UNESCO World Heritage Centre n.d.).10)

After the 2015 election, political dynamics prevented aristocratic family members from holding multiple positions in government. The politically motivated purge of high-ranking North Toraja government officials from the previous administration left just the two largest North Toraja noble houses’ family members with middle-ranking official positions. One was the camat, or subdistrict head, in the North Toraja government at Ke’te’ Kesu’; and a second was on the border between North Toraja and Tana Toraja. Rather than feeling threatened by the decreasing number of aristocratic family members holding office in North Toraja’s government structure, the aristocratic leader from Ke’te’ Kesu’ seemed to accept this arrangement as fair compared to having no aristocrat serving in the government. While pemekaran daerah introduced an opportunity to strengthen the dual role of noble families in adat and politics (Li 2001; Roth 2007; Tyson 2011), North Toraja’s aristocrats appeared to be on the losing side of the power dynamics, as suggested by Nancy Peluso and Michael Watts (2001).

The aristocrats’ diminishing role in politics reduces their leverage in securing legislation to protect their hereditary rights. It also reduces their leverage when it comes to other development projects, such as infrastructure, that are necessary to maintain adat objects. Deteriorating infrastructure in the region, such as roads leading to popular cave burial sites (i.e., Ke’te’ Kesu’ and Londa), is in need of repair. North Toraja’s aristocrats are increasingly powerless and losing their battle to influence decision makers to help them protect their ancestors’ valuable heritage.

During my field research, there was a sense of frustration among aristocratic leaders at the annual Toraja International Festival in Ke’te Kesu’ village. Initially, the festival gave slight hope to a particular noble family for finally getting all the attention they needed from national and provincial policy makers, such as high-ranking officials from the Ministry of Tourism. The family was struggling to maintain their adat site and search for stolen artifacts, such as effigies (Informal communications with a member of a noble family and a foreign expert on North Toraja, 2017).

The three-day festival was supposed to attract overseas and domestic tourists to see the beauty of the oldest tongkonan complex and enjoy performances by international artists. The noble family invited a renowned foreign expert on North Toraja to help them negotiate with Indonesian officials to retrieve stolen effigies from the international black market. The expert held a casual discussion with Indonesian officials, with no members of the noble family in attendance. Disappointingly for the family, the discussion ended unsuccessfully due to bureaucratic obstacles. Apart from missing this strategic lobbying opportunity, the aristocratic leader preferred to take on an insignificant backstage role; he was not even willing to deliver the opening remarks at the ceremony. Unsurprisingly, after the festival there was no significant change in the area. During my second visit, in 2019, the area still had no adequate parking lot for tourists, decent public restrooms, or well-constructed roads; and unfortunately, the noble family had still not found a way to bring the tau-tau home. The absence of strong regulations allowing North Toraja aristocrats’ voices to be heard in protecting adat objects may jeopardize the sustainability of the entire adat system.

The recognition of adat rights in written regulations, such as perda or regional government regulations, is viewed as vital for noble families to gain legal standing to preserve their hereditary rights. However, written rules are just a “dishonest illusion” (Benda-Beckmann and Benda-Beckmann 2010), because local governments are half-hearted in enforcing them. Therefore, noble families’ hopes of preserving their rights may never be realized. North Toraja’s less feudalistic governance system welcomes ordinary people to participate in decision making. After North Toraja’s split from Tana Toraja in 2008, the aristocrats’ acceptance of democratic values quickly opened a new way for North Toraja’s non-traditional elites to contest aristocrats’ dual role in adat and government through elections. This backfired for the aristocrats, since the democratic election was an open invitation for non-traditional elites to replace the domination of aristocrats in the government (Snyder 2000; Hadiz 2004). Under democratic rule and aristocrats’ lack of representation in political bodies or government, aristocratic rights can be easily revoked or ignored in favor of a new line of rulers.

While many aristocrats are still convinced that the democratic system does not threaten their adat position, their presence is diminishing within politics, and the government may ultimately weaken the noble families’ efforts to protect their hereditary leadership. The new open democratic governing system allows non-traditional elites to directly contest aristocrats’ dual role. The new line of leadership may not necessarily value adat as much as aristocrats do.

Conclusion

Democracy brought about a new way of governing people through decentralization. Decentralization and democracy were expected to provide more efficient delivery of public goods and ultimately provide better welfare for the people, including indigenous people such as Torajans. Unfortunately, after more than a decade of district splitting or pemekaran daerah, North Toraja has not come face to face with its promised future. The increased funding from the national and provincial governments along with income from the tourism sector do not cater to the neediest among the residents, nor to the adat sites that made North Toraja famous as a tourist destination in the first place.

This study is an in-depth investigation into how the dual role of North Toraja’s aristocrats is diminishing amidst the dominant non-traditional government rule. With the weakening of their role, aristocrats are hampered from maintaining their adat heritage and securing funds from the government for the preservation of adat sites. The finding of this study is limited to one potential cause for the diminishing role of aristocrats in politics: democratization and its concomitant decentralization. This evidence does not necessarily suggest that more people from the upper social and economic strata should be added to the North Toraja government. However, the study points to an ambiguous effect of adat revivalism on the minority indigenous group in a decentralized and democratized Indonesia. Moreover, I recognize the weakness of basing this study on individuals’ recollections of past events and relying too much on interview data. Thus, future studies may consider an alternative approach to the phenomenon by focusing on the literature on power sharing among elites.

Accepted: September 29, 2021

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank BAPPENAS-World Bank for the Scholarships Program for Strengthening Reforming Institutions; the School of Public Administration (STIA-LAN Jakarta Polytechnic); the National Institute of Public Administration; and the Political Science Department, Loyola University Chicago—especially Professor Kathleen M. Adams from the Anthropology Department and her Toraja network—for their support during my field research and writing.

References

Adams, Kathleen M. 2006. Art as Politics: Re-crafting Identities, Tourism, and Power in Tana Toraja, Indonesia. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.↩ ↩ ↩

―. 1997. Ethnic Tourism and the Renegotiation of Tradition in Tana Toraja (Sulawesi, Indonesia). Ethnology 36(4): 309–320. doi: 10.2307/3774040.↩

Aliansi Masyarakat Adat Nusantara [Indigenous Peoples’ Alliance of the Archipelago] (AMAN). 2019. Aliansi Masyarakat Adat Nusantara. https://www.aman.or.id/, accessed December 17, 2020.↩

Asiimwe, Delius; and Musisi, Nakanyike B. 2007. Decentralisation and Transformation of Governance in Uganda. Kampala: Fountain Publishers.↩

Aspinall, Edward; and Fealy, Greg. 2003. Introduction: Decentralisation, Democratisation and the Rise of the Local. In Local Power and Politics in Indonesia: Decentralisation and Democratisation, edited by Edward Aspinall and Greg Fealy, pp. 1–12. Singapore: ISEAS. doi: 10.1355/9789812305237-006.↩

Bardhan, Pranab; and Mookherjee, Dilip. 2006. Decentralisation and Accountability in Infrastructure Delivery in Developing Countries. Economic Journal 116(508): 101–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0297.2006.01049.x.↩

Bazzi, Samuel; and Gudgeon, Matthew. 2021. The Political Boundaries of Ethnic Divisions. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 13(1): 235–266. doi: 10.1257/app.20190309.↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

Benda-Beckmann, Franz von; and Benda-Beckmann, Keebet von. 2010. Multiple Embeddedness and Systemic Implications: Struggles over Natural Resources in Minangkabau since the Reformasi. Asian Journal of Social Science 38(2): 172–186. doi: 10.1163/156853110X490881.↩ ↩

Berger, Suzanne, ed. 1983. Organizing Interests in Western Europe: Pluralism, Corporatism, and the Transformation of Politics. New York: Cambridge University Press.↩

Bigalke, Terance W. 2005. Tana Toraja: A Social History of an Indonesian People. Singapore: NUS Press.↩

―. 1981. A Social History of “Tana Toraja” 1870–1965. PhD dissertation, University of Wisconsin-Madison. https://www.proquest.com/openview/bdd68351dfdc0d05cfc6260cc7bcf11d/1.pdf/advanced, accessed November 9, 2021.↩

Booth, Anne. 2011. Splitting, Splitting and Splitting Again: A Brief History of the Development of Regional Government in Indonesia since Independence. Bijdragen tot de taal-, land- en volkenkunde [Journal of the humanities and social sciences of Southeast Asia] 167(1): 31–59. doi: 10.1163/22134379-90003601.↩

Crystal, Eric. 1974. Cooking Pot Politics: A Toraja Village Study. Indonesia 18: 119–151. doi: 10.2307/3350696.↩

de Jong, Edwin. 2013. Making a Living between Crises and Ceremonies in Tana Toraja: The Practice of Everyday Life of a South Sulawesi Highland Community in Indonesia. Leiden: Brill.↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

Emerson, Robert M.; Fretz, Rachel I.; and Shaw, Linda L. 2011. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes. 2nd ed. Chicago Guides to Writing, Editing, and Publishing series. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.↩

Evi Nurvidya Arifin; Aris Ananta; Dwi Retno Wilujeng Wahyu Utami; Nur Budi Handayani; and Agus Pramono. 2015. Quantifying Indonesia’s Ethnic Diversity: Statistics at National, Provincial, and District Levels. Asian Population Studies 11(3): 233–256. doi: 10.1080/17441730.2015.1090692.↩

Falleti, Tulia. 2005. A Sequential Theory of Decentralization: Latin American Cases in Comparative Perspective. American Political Science Review 99(3): 327–346. doi: 10.1017/S0003055405051695.↩

Fitria Fitrani; Hofman, Bert; and Kaiser, Kai. 2005. Unity in Diversity? The Creation of New Local Governments in a Decentralising Indonesia. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 41(1): 57–79. doi: 10.1080/00074910500072690.↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

Fox, Jonathan A.; and Aranda, Josefina. 1996. Decentralization and Rural Development in Mexico: Community Participation in Oaxaca’s Municipal Funds Program. Monograph Series 42. Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies, University of California San Diego. doi: 10.13140/2.1.5160.0960.↩

Fujii, Lee Ann. 2014. Five Stories of Accidental Ethnography: Turning Unplanned Moments in the Field into Data. Qualitative Research 15(4): 525–539. doi: 10.1177/1468794114548945.↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

Ganguly, Rajat, ed. 2013. Autonomy and Ethnic Conflict in South and South-East Asia. New York: Routledge.↩

Grossman, Guy; and Lewis, Janet I. 2014. Administrative Unit Proliferation. American Political Science Review 108(1): 196–217. doi: 10.1017/S0003055413000567.↩ ↩

Grossman, Guy; and Pierskalla, Jan H. 2014. The Effects of Administrative Unit Proliferation on Service Delivery (mimeographed). https://polisci.osu.edu/sites/polisci.osu.edu/files/GrossmanPierskalla_v6.pdf, accessed November 9, 2021.↩ ↩

Hadiz, Vedi R. 2004. Decentralization and Democracy in Indonesia: A Critique of Neo-Institutionalist Perspectives. Development and Change 35(4): 697–718. doi: 10.1111/j.0012-155X.2004.00376.x.↩ ↩ ↩

Haryanto; Mada Sukmajati; and Lay, Cornelis. 2019. Territory, Class, and Kinship: A Case Study of an Indonesian Regional Election. Asian Politics & Policy 11(1): 43–61. doi: 10.1111/aspp.12444.↩

Henley, David; and Davidson, Jamie S. 2008. In the Name of Adat: Regional Perspectives on Reform, Tradition, and Democracy in Indonesia. Modern Asian Studies 42(4): 815–852. doi: 10.1017/S0026749X07003083.↩

Hollan, Douglas W.; and Wellenkamp, Jane C. 1996. The Thread of Life: Toraja Reflections on the Life Cycle. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.↩

Indonesia, Badan Pusat Statistik Provinsi Sulawesi Selatan [South Sulawesi Province Central Agency on Statistics] (BPS Sulawesi Selatan). n.d. Badan Pusat Statistik Provinsi Sulawesi Selatan. https://sulsel.bps.go.id/, accessed December 18, 2020.↩ ↩

Indonesia, Sekretariat Kabinet Republik Indonesia [Cabinet Secretariat of the Republic of Indonesia] (Setkab). 2019. Usulan 314 DOB dikaji, Mendagri: Pemerintah tetap berlakukan moratorium pemekaran daerah [Proposal of 314 new autonomous regions is under examination, Ministry of Home Affairs: The national government still upholds regional splitting moratorium policy]. https://setkab.go.id/usulan-314-dob-dikaji-mendagri-pemerintah-tetap-berlakukan-moratorium-pemekaran-daerah/, accessed January 5, 2020.↩

Klenke, Karin. 2013. Whose Adat Is It? Adat, Indigeneity and Social Stratification in Toraja. In Adat and Indigeneity in Indonesia: Culture and Entitlements between Heteronomy and Self-Ascription, edited by Brigitta Hauser-Schäublin, pp. 149–165. Göttingen: Göttingen University Press. https://books.openedition.org/gup/179?lang=en, accessed November 9, 2021.↩

Lewis, Blane D. 2017. Does Local Government Proliferation Improve Public Service Delivery? Evidence from Indonesia. Journal of Urban Affairs 39(8): 1047–1065. doi: 10.1080/07352166.2017.1323544.↩

Li, Tanya Murray. 2001. Masyarakat Adat, Difference, and the Limits of Recognition in Indonesia’s Forest Zone. Modern Asian Studies 35(3): 645–676. doi: 10.1017/S0026749X01003067.↩ ↩ ↩

Litvack, Jennie; Ahmad, Junaid; and Bird, Richard. 1998. Rethinking Decentralization in Developing Countries. Washington, DC: World Bank. doi: 10.1596/0-8213-4350-5.↩ ↩

Mohammad Zulfan Tadjoeddin; Athia Yumna; Sarah E. Gultom; M. Fajar Rakhmadi; M. Firman Hidayat; and Asep Suryahadi. 2016. Inequality and Stability in Democratic and Decentralized Indonesia. SMERU Working Paper. SMERU Research Institute, Jakarta. https://www.smeru.or.id/sites/default/files/publication/inequalitystability_eng_0.pdf, accessed November 9, 2021.↩

Montalvo, José G.; and Reynal-Querol, Marta. 2005. Ethnic Polarization, Potential Conflict, and Civil Wars. American Economic Review 95(3): 796–816. doi: 10.1257/0002828054201468.↩

Muhammad Fadli; Muh. Kausar Bailusy; Jayadi Nas; and Achmad Zukfikar. 2018. Keterlibatan elit lokal dalam peningkatan partisipasi politik pada pemilihan bupati dan wakil bupati Kabupaten Toraja Utara tahun 2015 [Local elites’ involvement to increase political participation in North Toraja bupati and vice bupati election 2015]. ARISTO 6(2): 301–328. doi: 10.24269/ars.v6i2.1025.↩

Noer Fauzi; and R. Yando Zakaria. 2002. Democratizing Decentralization: Local Initiatives from Indonesia. Paper Submitted for the International Association for the Study of Common Property Ninth Biennial Conference, Victoria Falls. https://dlc.dlib.indiana.edu/dlc/bitstream/handle/10535/2169/fauzin170502.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y, accessed November 9, 2021.↩

Nooy-Palm, Hetty. 2014. The Sa’dan-Toraja: A Study of Their Social Life and Religion. Dordrecht: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-94-017-7150-4.↩

Peluso, Nancy Lee; and Watts, Michael, eds. 2001. Violent Environments. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.↩ ↩

Pierskalla, Jan H. 2016. Splitting the Difference? The Politics of District Creation in Indonesia. Comparative Politics 48(2): 249–268. doi: 10.5129/001041516817037754.↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

Pierskalla, Jan H.; and Sacks, Audrey. 2017. Unpacking the Effect of Decentralized Governance on Routine Violence: Lessons from Indonesia. World Development 90 (February): 213–228. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.09.008.↩

Priyanti Pakan. 1977. Orang Toraja: Identifikasi, klasifikasi dan lokasi [Torajan people: Identification, classification, and location]. Berita Antropologi 9(32–33): 21–49.↩

Rizal Sukma. 2012. Conflict Management in Post-authoritarian Indonesia: Federalism, Autonomy and the Dilemma of Democratisation. In Autonomy and Disintegration in Indonesia, edited by Damien Kingsbury and Harry Aveling, pp. 78–88. London: Routledge.↩

Robinson, Kathryn. 2020. Islamic Influences on Indonesian Feminism. Social Analysis 50(1): 171–177. doi: 10.3167/015597706780886012.↩

Roth, Dik. 2009. Lebensraum in Luwu: Emergent Identity, Migration and Access to Land. Bijdragen tot de taal-, land- en volkenkunde [Journal of the humanities and social sciences of Southeast Asia] 161(4): 485–516. doi: 10.1163/22134379-90003705.↩

―. 2007. Many Governors, No Province: The Struggle for a Province in the Luwu-Tana Toraja Area in South Sulawesi. In Renegotiating Boundaries: Local Politics in Post-Suharto Indonesia, edited by H. G. C. Schulte Nordholt and Gerry van Klinken, pp. 121–147. Leiden: Brill. doi: 10.1163/9789004260436_007.↩ ↩ ↩

Schrauwers, Albert. 1995. In Whose Image? Religious Rationalization and the Ethnic Identity of the To Pamona of Central Sulawesi. PhD dissertation, University of Toronto.↩

Siregar, Baldric; and Rudy Badrudin. 2019. The Evaluation of Fiscal Decentralization in Indonesia Based on the Degree of Regional Autonomy. Journal of Reviews on Global Economics 8: 611–624. doi: 10.6000/1929-7092.2019.08.53.↩

Snyder, Jack. 2000. From Voting to Violence: Democratization and Nationalist Conflict. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.↩ ↩ ↩

Sukri Sukri. 2018. The Toraja as an Ethnic Group and Indonesian Democratization since the Reform Era. PhD dissertation, Universitäts Bonn. https://bonndoc.ulb.uni-bonn.de/xmlui/bitstream/handle/20.500.11811/7439/5049.pdf?sequence=1, accessed November 20, 2021.↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

Tiebout, Charles M. 1956. A Pure Theory of Local Expenditures. Journal of Political Economy 64(5): 416–424. doi: 10.1086/257839.↩ ↩ ↩

Treisman, Daniel. 2007. The Architecture of Government: Rethinking Political Decentralization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511619151.↩ ↩

Tyson, Adam. 2011. Being Special, Becoming Indigenous: Dilemmas of Special Adat Rights in Indonesia. Asian Journal of Social Science 39(5): 652–673. doi: 10.1163/156853111X608339.↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

UNESCO World Heritage Centre. n.d. Tana Toraja Traditional Settlement. https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5462/, accessed December 18, 2020.↩

Van Klinken, Gerry. 2007. Communal Conflict and Decentralisation in Indonesia. Australian Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies Occasional Paper 7. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.1025846.↩

Volkman, Toby Alice. 1985. Feasts of Honor: Ritual and Change in the Toraja Highlands. Illinois Studies in Anthropology No. 16. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.↩

Wilson, Chris. 2008. Ethno-religious Violence in Indonesia: From Soil to God. London: Routledge.↩

Wimmer, Andreas. 2013. Ethnic Boundary Making: Institutions, Power, Networks. New York: Oxford University Press.↩

World Bank. 2019. The Indonesia Database for Policy and Economic Research (INDO-DAPOER). May 7. https://databank.worldbank.org/source/indonesia-database-for-policy-and-economic-research, accessed November 19, 2019.↩

Online News Sources

Kerusuhan Toraja terindikasi dirancang sistematis [Riots in Toraja indicated to be systematically orchestrated]. Antaranews. July 30, 2010. https://makassar.antaranews.com/berita/17468/kerusuhan-toraja-terindikasi-dirancang-sistematis, accessed December 18, 2020.↩

Pilkada Toraja Utara rawan konflik [North Toraja local head election is prone to conflict]. Antaranews. July 14, 2010. https://www.antaranews.com/berita/211754/pilkada-toraja-utara-rawan-konflik, accessed December 18, 2020.↩

1) Adat is customary law applied mainly to the indigenous population within Indonesia and the Malay Peninsula. The unwritten community rules of conduct cover various events and activities such as birth, marriage arrangements, rituals, way of life, and death.

2) Lembang is a centuries-old traditional structure with a universal village system adopted within Toraja.

3) “Big bang” is a term used by the World Bank and decentralization advocates to describe the first wave of decentralization in developing countries after the Asian financial crisis in 1997. The term indicates an abrupt implementation of decentralization, marked by the dramatic splitting of a region (regency or province).

4) Ethnic polarization is a situation in which individuals from one group can be easily identified as different from individuals from other groups.

5) Aluk to Dolo or Alukta is an ancient animistic belief system adopted by the indigenous Torajan population in South Sulawesi. Since 1969, Alukta has been considered an offshoot of Hindu Dharma. According to the South Sulawesi Province Central Agency on Statistics, approximately 4 percent of the 618,578 people in Tana Toraja, North Toraja, and Mamasa still adhere to this belief system (Indonesia, BPS Sulawesi Selatan n.d.).

6) A tongkonan is an ancient Torajan Austronesian-style house with a unique and massive boat-shaped saddleback roof. This type of house may be found in numerous places in Indonesia.

7) Demokrasi terpimpin, or Guided Democracy, was a term used by Indonesia’s first president, Sukarno, who was dissatisfied with Western liberal democracy. He established a new political system that blended three different political ideologies—nationalism, Communism, and religion—under the leadership of a strongman, Sukarno himself.

8) AMAN is an Indonesian alliance of indigenous groups to protect and fight for their rights. Adat is a system of customary law characterized by its historical narrative and interpretation through generations via oral transmission rather than written legal documents. The oral history becomes law, which is internalized within the community.

9) Rambu solo’ is a massive and prolonged ancient Toraja funeral rite to pay tribute to the ancestors’ spirits and send the deceased into eternity. Rambu tuka is a big feast to celebrate a wedding, the blessing of a new tongkonan, or a successful harvest.

10) Ten traditional settlements in Tana Toraja are still on the tentative list of UNESCO World Heritage nominations. The nomination was submitted on June 10, 2009, but no decision has been announced yet.