Contents>> Vol. 11, No. 3

Media Representation of China in Malaysia: Television News Coverage of Najib Razak’s Visit in 2016

Ng Hooi-Sean*

*Department of Southeast Asian Studies, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

e-mail: khsng79[at]gmail.com

DOI: 10.20495/seas.11.3_477

The increasing prominence of China on the world stage has sparked scholarly interest in studying the country’s representation in the media. Also driving the enthusiasm is the global expansion of Chinese state media, which some refer to as an attempt to export Chinese propaganda. Research on the topic in Southeast Asia remains lacking despite the region’s being in China’s backyard. This qualitative study aims to narrow the knowledge gap by looking at China’s representation in Malaysia. Using content analysis and in-depth interviews, it examines specifically the coverage of former Prime Minister Najib Razak’s 2016 visit to China by the Malay, Mandarin, and English bulletins on public and private television. The results show that China’s portrayal in the coverage is positive, notwithstanding the stories indicating concerns about the implications of China’s rise. The outcome points to the dominance of the state narrative, with instances of the press breaking the authorities’ restrictions to inform the audience. It appears that the reportage was not much impacted by Chinese media’s efforts to go global. Drawing on the Hierarchy of Influences model, the study demonstrates that the representation of China in Malaysian media coverage is a product shaped by intertwined social, cultural, and political factors as complex as Malaysian society.

Keywords: Malaysia, China, representation, media, Southeast Asia, Najib Razak

Introduction

Being a one-party Communist state with the world’s largest population, the second-largest economy, and a growing influence on the world stage, China has always been an “exotic” topic regularly featured in international news coverage. In the West, media coverage of China surged significantly after the end of the Cold War (Goodman 1999; Stone and Xiao 2007). The trend became stronger as China rose to power over the years (Okuda 2016). This triggered scholarly interest in finding out how this Far East country is represented in the media.

While research on the representation of China is nothing new, as with other studies seeking to investigate media bias when representing the “Other” (Parenti 1986), the enthusiasm appears to have gained new momentum in recent years following the global expansion of Chinese media. The endeavor, which started as part of Beijing’s Go Out Policy (走出去战略, also known as the Go Global Policy), sees Chinese state media outlets such as China Central Television (CCTV) and Xinhua News Agency expanding their operations abroad to boost the presence of Chinese content worldwide (Wu 2012; Sun 2014). Unsurprisingly, the move is a controversial one, given China’s poor record in press freedom. Some equate it to the export of Chinese propaganda: “For the party, propaganda is not a degraded form of information—it is information,” writes Nicholas Bequelin (2009), referring to the initiative as being “not about informing the foreign public” but about “channeling a specific view of China to the rest of the world.”

Concerns about biased media representation and the potential implications of Chinese media expansion have resulted in a growing body of literature on the representation of China (Akhavan-Majid and Ramaprasad 2000; Peng 2004; Seib and Powers 2010; Willnat and Luo 2011; Feng et al. 2012; Zhang et al. 2016). Despite attention from the international academic community, few studies on the topic have been carried out in the context of Southeast Asia. This is notwithstanding the region’s being in the backyard of China, where the impact of China’s rise can be directly felt and experienced. Southeast Asia is a strategically crucial region to China and one of the critical areas for the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) (Gong 2019). As Chinese media strive to expand their presence across the globe, initiatives also appear to be taking place in the region. This can be seen from the various regional-level and government-to-government partnerships and agreements that signify Beijing’s efforts in engaging media players in the region, such as the ASEAN-China Media Cooperation Forum and the collaboration between CCTV and Malaysia’s national broadcaster, Radio Televisyen Malaysia (RTM) (Malay Mail 2014; Sun 2014; ASEAN-China Centre 2021; CCTV+ 2021).

Nonetheless, relationships between Southeast Asian countries and China have been rather complicated. Economically relying on and benefiting from China’s rise, some of these countries remain wary about the implications of China’s growing clout on the region, be they political, economic, strategic, or geopolitical (Acharya 2009; Gong 2019). Territorial disputes between China and its neighbors—such as Vietnam, the Philippines, and Malaysia—over competing claims in the South China Sea continue to play out. There is also concern over China’s attempts to influence and interfere with other nations’ domestic affairs through ethnic Chinese minorities, whose “allegiance” is often doubted by local leaders and communities (Elina and T.N. 2017; Liu and Lim 2019).

Given all these scenarios, it would be interesting to find out how China is represented by the media in the region. The present study offers a Malaysian perspective on the topic by looking at the representation of China in the television news coverage of former Prime Minister Najib Razak’s visit to China in 2016. It is framed by two research questions:

1. How is China represented in television news coverage of Najib’s visit to China?

2. What are the factors that played a role in shaping the coverage and subsequently China’s representation in the reportage of the visit?

Background

Taking place in early November 2016, the official visit raised eyebrows following Malaysia’s inking of trade and investment deals worth a record RM144 billion with China. It was said to be an event marking Kuala Lumpur’s pivot to Beijing despite Malaysia’s ongoing territorial dispute with China in the South China Sea. It came amidst Najib’s attempt to boost the economy ahead of the elections, as well as strained ties with Washington after the US Department of Justice implicated him in the 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) money laundering scandal (Mustafa 2016; Sipalan 2016). Critics equated the deals to selling off the country, arguing that some of the items, such as the RM55 billion East Coast Rail Link (ECRL) project, could lead to mounting debt and jeopardize Malaysia’s sovereignty. They also highlighted the possible link between these projects and the intention to bail out 1MDB’s debt (Lakshana 2016; Gunasegaram 2017).

Technocratic reasoning aside, there is a more communal explanation for the controversy surrounding the visit that stems from the interethnic relations in the country. Malaysia is a multiethnic, multireligious society represented mainly by Malays, Chinese, Indians, and the Orang Asal indigenous peoples. Its political culture is fundamentally defined by ethnicity. Political parties, regardless of ruling or opposition coalition, are mostly divided along ethnic lines (Lee 2010; Segawa 2017). Plans and policies, apart from the larger goals of economic growth and development, are often drafted with the intention to win electoral support and secure political legitimacy (Liu and Lim 2019; Camba et al. 2021). The high-profile ECRL, which connects the less developed, Malay-heavy states of Pahang, Terengganu, and Kelantan on the peninsular east coast with the wealthier, more developed regions on the west, for instance, is said to be Najib’s attempt to woo voters in the rural Malay constituencies following the loss of popularity of his party, the United Malays National Organization (UMNO), in the more urban seats (Liu and Lim 2019; Lim et al. 2021). Similarly, it is not uncommon for a development agenda to get spun into an issue of race and religion to rally support. In the case of Najib’s visit, as far as China was concerned, the prospect of increased Chinese presence and the potential of being dragged into a Chinese-dominated order were destined to sound the alarm for Malay leaders who were apprehensive about “Chinese” (Mustafa 2016; Sipalan 2016). This points to the fact that despite Malaysia having been independent for over half a century, internal differences between ethnic groups remain problematic (Shamsul 1997).

A case in point is Forest City, a residential development by the Chinese firm Country Garden in collaboration with the Sultan of Johor. The project was criticized by Najib’s predecessor, Mahathir Mohamad, who claimed it would result in an influx of Chinese immigrants and subsequently alter the demographics and status of Malays in the country. Tapping into the fears of conservative Malays, who often see the Chinese, Malaysian or not, as a threat to Malay-Muslim interests, the move was Mahathir’s tactic to garner support for his newly formed Parti Pribumi Bersatu (Malaysian United Indigenous Party, commonly known as Bersatu) in Johor, where it competed for the Malay votes with UMNO, the largest party in the National Front (Barisan Nasional or BN) ruling coalition (Liu and Lim 2019). The strategy worked: UMNO lost Johor to Bersatu in the 2018 general election, an event that saw the unprecedented defeat of BN after reigning Malaysia for decades since the country’s independence in 1957 (Malhi 2018).

Much like the country’s social and political construct, the media outlets in Malaysia are also largely divided along racial and linguistic lines. Despite the diversity, press freedom in the country is restricted. Under BN—led mainly by UMNO, the Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA), and the Malaysian Indian Congress—the mainstream media outlets are consolidated in the hands of a small number of companies, parties, and individuals aligned with the government (Abbott and Givens 2015; Yang and Md. Sidin 2015). The national broadcaster, RTM, is a government department (RTM 2020). The country’s largest media conglomerate, Media Prima—which owns the Malay dailies Berita Harian and Harian Metro, the English daily New Straits Times, and all the free-to-air private television channels—was an investment arm of UMNO until the party disposed of its majority stake after the 2018 election (Yang and Md. Sidin 2015; Edge Markets 2019). The country’s leading English-language newspaper, the Star, was published by Star Media Group, a cash cow for MCA (Tan and Tay 2018). The Chinese market was dominated by tycoon Tiong Hiew King’s Media Chinese International, which took up 89 percent of the share with the top four Chinese-language newspapers: Sin Chew Jit Poh, China Press, Guang Ming Daily, and Nanyang Siang Pau (Abbott 2011). Furthermore, the media was bound by a set of laws, including the Printing Presses and Publications Act, Sedition Act, Official Secrets Act, and Communications and Multimedia Act, that penalized the publication of “offensive” content and effectively fostered a culture of self-censorship among media practitioners (Wong 2000; Abbott 2011; Yang and Md. Sidin 2016; Hector 2018).

Although there were positive developments in the media landscape, among them the purported freer environment under the fifth prime minister, Abdullah Ahmad Badawi (Pepinsky 2007; Tang 2018), as well as the emergence and proliferation of online media—which was seen as a game changer in Malaysian politics (Liow 2012; Abbott and Givens 2015; Yang and Md. Sidin 2015)—the truth is media continued to be shackled and press freedom stifled under the BN government (Pepinsky 2007; Teoh 2018). Scholars and journalists have generally regarded the control on the media as a feature of BN’s being a quasi-democracy—a hybrid regime treading the line between democracy and authoritarianism (Wong 2000; Abbott and Givens 2015; Yang and Md. Sidin 2015).

While one might argue that studying the representation of China in the Malaysian media would be futile given the government’s control of the media, research is still necessary. This is because the perspectives of the media outlets are different, with each focusing on issues that concern their respective audiences (Wong 2000). Jason Abbott and John Givens (2015) examined three separate efforts at coding political bias in the Malaysian media and concluded that significant pro-government bias was present in the Malay- and English-language media, while the Chinese-language and online media were much more balanced and independent in their reporting. Yang Lai Fong and Md. Sidin Ahmad Ishak (2016) analyzed the coverage of the controversy involving banning of the use of the word “Allah” by a Catholic weekly, and they found that the Chinese-language Sin Chew Daily was vocal, with the greatest number of voices criticizing the ban and condemning the ruling parties for fanning the sensitivities of the people. The English-language Star was moderate, with voices supporting and criticizing the use of “Allah” by non-Muslims; but none of the opinions were critical of the government. And the Malay-language Utusan Malaysia presented only the government’s view and was strongly supportive of the status quo. Furthermore, Utusan Malaysia downplayed negative topics, excluded dissenting views, and explicitly described non-Muslims as challenging and threatening the status of Islam and Malays.

Given the different angles and emphases of the media outlets in their coverage, it is believed that interesting differences can also be observed in how they report a rising China, hence the worth of such research in the context of Malaysia.

Culture, Power, and Media Representation

Media representation is the practice of giving meaning to the subjects depicted in the media (Hall 2005). It involves using signs and symbols such as words, images, and body language to create and communicate meaning to the audience (Hall 1997; 2005). Media representation is more than a mere re-presentation or re-depiction of someone or something. It can never be separated from politics, as those who wield power in society will seek to influence what gets to be represented in the media and the meaning associated with it (Hall 2005). Culture also plays a vital role, because representation is a process taking place between members of a culture that share the same conceptual map (Hall 1997; 2005). Nick Lacey (1998) defines media representation as a product of institutions, which inevitably have an influence on what they produce.

In that sense, representation appears to share some commonalities with framing. Framing is a practice whereby the media guide the audience’s understanding of a news event by regulating the amount and prominence of details in a story (Entman 1991). It is an essential tool in the political process, used to influence public opinion by making “one basic interpretation more readily discernible, comprehensible, and memorable than others” (Entman 1991, 7). This bears a resemblance with the fixing practice in representation, whereby the authorities fix meanings associated with certain events or topics so that they become the only definitions emerging in people’s minds when they think about the terms (Hall 2005). Also, framing often appears very natural, without the audience noticing it. According to Baldwin Van Gorp, this is due to the “repertoire of frames in culture” shared between journalists and audiences (Van Gorp 2007, 61). This shows that framing, just like representation, is a communication process involving the communicators creating messages meaningful to the receivers using the conceptual maps both parties share.

Factors Shaping Representation of China

The media is powerful because it can shape our opinions and attitudes. This power extends beyond international boundaries. With international news coverage, the media can shape our perceptions of a country (Galtung and Ruge 1965; Griffiths 2013) or even a government’s foreign policy toward it (Goodman 1999; Johnston 2013). This is because most people rely on the media to learn about other countries (Brewer et al. 2003). The same applies also to China.

The outcome of representation can look and mean different as it moves across individuals, groups, and societies (Hall 2005). A review of the literature on the representation of China shows a divide between the Western/US and Chinese media: researchers have found that China is often painted in a negative light in the Western media and exclusively positive in the Chinese media. For instance, Feng Miao et al. (2012) compared how China’s Xinhua News Agency and the United States’ Associated Press (AP) framed the 2008 baby formula scandal in China. They discovered that Xinhua portrayed the Chinese government positively as open, well prepared, and swift in handling the incident, whereas AP depicted Beijing negatively as dishonest and inadequate in dealing with the scandal. Similarly, in their analysis of American and Chinese newspaper coverage of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) epidemic in China, Catherine Luther and Zhou Xiang (2005) found that the New York Times and Washington Post focused on negative aspects of the outbreak, such as the negative consequences on the economy, responsibility of the Chinese leaders for the spread, and failed struggles of individuals fighting the disease. This reporting was in contrast to China Daily and People’s Daily, which focused on positive aspects such as initiatives undertaken by Beijing to curtail the impact on the economy, as well as success stories of individuals and families in overcoming the disease.

Several scholarly works have suggested that the ideological and political system is the main cause of the telling differences in China coverage by the Western and Chinese media. Wang Xiuli and Pamela Shoemaker (2011), for example, claimed that the persistent negative tone in US media coverage of China was driven by the “China as challenger” sentiment engendered by the fundamental differences between the two countries’ cultural, ideological, and political systems. Peng Zengjun noted that the US press coverage of China was highly critical when certain aspects of the Chinese domestic environment conflicted with the American values of individual liberty, democracy, and human rights, reflecting “the dominant political agenda of the US government and the ideological framework of the American media” (Peng 2004, 58). Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky (2002) highlighted that the US media coverage of Communist countries such as China and Russia was driven by the intent of maintaining the status quo of American society and securing the interests of the political and business elites who regarded Communism as a threat to the United States’ capitalist democratic system and ultimately their powers, properties, and privileges. As such, propaganda against Communism is orchestrated, leading to persistent negative portrayal of these countries in the US media.

In China, on the contrary, the positive representation comes from the fact that the news media, including CCTV, People’s Daily, and Xinhua News Agency, are state owned and run by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) propaganda arm (Hearns-Branaman 2009). In China, propaganda is deemed a legitimate tool for building the society sought by the authorities (Shambaugh 2007). This makes the content on Chinese media outlets information from the Party and the state. To illustrate, Alex Chan (2002) discovered that Jiaodian Fangtan, a CCTV current affairs program said to be breaking Chinese media convention with exposé and sharp criticism of government misconduct, was hardly “revolutionary” as the voice of the Party still dominated the content, sensitive issues related to the grassroots were rarely discussed, and the so-called criticism was never directed at the central administration. It also reflected the Chinese journalistic norm of “covering good news while avoiding the bad,” whereby the press would focus on reporting the positive aspects of a story in order to reduce the negative impact of news and give publicity to the government. This contrasts with the Western-style watchdog journalism, whereby the media report “bad news” supposedly to keep the authorities in check (Gans 2004; Farah and Mosher 2010).

Aside from ideological and political systems, the representation of China can also be shaped by other factors. Huang Yu and Christine Leung (2005) asserted that China’s negative portrayal in the Western coverage of the SARS epidemic was caused by China’s poor handling of the crisis rather than being a deliberately biased and inaccurate representation of the “Other” by the Western media. Lars Willnat and Luo Yunjuan (2011) argued that the lack of representation and comprehensiveness in global television news coverage of China—which accounted for only a small percentage, with little variation in the topics reported—could be due to the nature of broadcast news, where airtime is limited. Zhu Yicheng and Wang Longxing (2017) found that the attitudes of the ruling class, geopolitical factors, relationships with China, national differences, and political stances of media outlets were the major factors shaping the local newspaper coverage of China’s outward foreign direct investment in Latin American countries.

Chinese Media’s Globalization and Local Media Coverage

When studying the representation of China in the global media landscape, one trend to note is the global expansion of Chinese media outlets under the Go Out Policy. Referred to as the “global propaganda campaign” by the Guardian, the initiative sees Beijing employing various strategies to boost the presence of CCP-sanctioned content worldwide, such as establishing overseas bureaus and offices for its state media outlets, placing China-friendly advertorials in international media, and securing content deals with foreign media organizations (Farah and Mosher 2010; Sun 2014; Lim and Bergin 2018). The aim is to “tell China’s story well” (Lim and Bergin 2018). With that, it reportedly seeks to reclaim storytelling rights from the “biased and negative” West (Sun 2014, 1906), improve international public opinion and create a pro-China global environment (Brady 2009), redraw the global information order dominated by the Western media (Lim and Bergin 2018), and even establish some form of cultural imperialism (Wasserman and Madrid-Morales 2018).

It is worth paying attention to the possible changes in media coverage of China following the endeavor. Zhang Xiaoling (2013), for instance, examined the content of Africa Live, a program on CCTV’s sister station CCTV Africa and observed that it painted only a positive image of China while being highly critical of the West. Zhang Xiaoling et al. (2016) looked at press coverage of China in South Africa and Zimbabwe and found that in South Africa, where journalists are more independent minded, the media generally painted a balanced picture of China, with neutral reports dominating the coverage; in Zimbabwe, where China’s involvement had been long with a government-to-government approach, the reportage was torn between public and private media: China had greater exposure with mostly positive coverage in the former, as opposed to the latter, where the reports were fewer and much more critical due to the more Western, liberal stand adopted.

Back in Southeast Asia, few studies have suggested the role of ruling elites in shaping local media coverage of China. Bui Nhung (2017), for example, demonstrated that Vietnam tried to keep a lid on anti-Chinese sentiment in the coverage of the 2014 Haiyang Shiyou 981 oil rig crisis, noting domestic stability and policy flexibility could be the reasons prompting Hanoi to adopt such a strategy in reporting what was referred to as one of the most severe clashes between the two countries in recent history. Lupita Wijaya and Cheryl Bensa (2017) concluded that the coverage of the South China Sea dispute by Indonesian media outlets was predominantly neutral and corresponded to President Joko Widodo’s policy of conflict resolution via diplomacy when they asserted that neither China nor other claimant states should claim ownership of the waters and called for peaceful resolution of the dispute.

In Malaysia, Ch’ng Huck Ying (2016) studied the ways in which Malaysian newspapers framed foreign news events and issues and learned that the Malay-language Utusan Malaysia presented a highly positive view of the Malaysia-China relationship, the Chinese-language Sin Chew Daily presented a positive frame of China’s rise as a political and economic superpower, and the English-language New Straits Times cast China’s rising influence on regional economic development in a remarkably positive light. The positive portrayals showed not just Malaysia’s intention of strengthening economic ties with China, but also the close connection between mainstream media and political leadership as well as the restrictive laws that compel media compliance.

Teoh Yong Chia et al. (2016) compared the coverage of Najib’s 2014 visit to China by Malaysia’s Star and China’s People’s Daily and found that although the friendly relationship between the two countries was the most highlighted aspect in both papers’ coverage, the Star appeared to focus more on the visit’s economic consequences, while People’s Daily underlined the need for further action on the disappearance of Malaysia Airlines flight MH370 with two-thirds of Chinese nationals aboard. The authors attribute the varied framing patterns to the papers’ ownership and the political cultures in which they operate, as government control results in their coverage being informed by the respective states’ viewpoints and interests.

Yang Lai Fong and Ramachandran Ponnan (2019) examined the coverage of MH370 by newspapers in Malaysia and China and found that Malaysian newspapers gave much more attention to the incident and Malaysia-China bilateral relations than did their Chinese counterparts. This indicates that maintaining a good relationship with Beijing is vital for Kuala Lumpur as it seeks to maximize benefits from China’s vast and growing economy—not just for commercial or strategic reasons but also for the political legitimacy and survival of the administration.

A review of the literature on the representation of China reveals several gaps. First, it is dominated by research using major media outlets from the United States and China. Second, television news appears to be a less explored medium despite being an important source of information that is no less influential (Reese and Buckalew 1995). This is especially relevant for Malaysia given that most people still regard mainstream media as more credible than online media (Liow 2012), most people consume content from traditional media despite the rise of digital media (Nielsen 2018), and more people get their news from television than from newspapers (Star 2017). Finally, there is a lack of Southeast Asian perspectives on the topic. The media does not only act as a means of social control but also reflects social and cultural patterns of a particular society (Shoemaker and Reese 1996). Studies by Lim Guanie et al. (2021), Alvin Camba et al. (2021), and others have shown that the success of the BRI in Southeast Asia is not determined solely by the Chinese government but also by dynamics in the host countries. The same can be said of the representation of China, whereby domestic factors can affect how the country is portrayed. Hence, more research is needed to promote a better understanding of the region and narrow the gap in the literature. Building on the existing studies about media coverage of China, the present paper seeks to offer new insights with the two research questions above on the representation of China in Malaysia.

Theoretical Framework

This study employs the Hierarchy of Influences model as the theoretical framework. Proposed by Pamela Shoemaker and Stephen Reese (1996; 2014), the model theorizes that media content is shaped by multiple forces throughout the process of its making. It categorizes the forces into five levels, based on the strength of their influence on media content:

1. Individual: Content is affected by a media worker’s characteristics and experiences, such as gender, ethnicity, and upbringing, but only to the extent where the influence is sufficient to override more powerful forces coming from professional ethics and higher levels of the hierarchy;

2. Routine: Content is shaped by the repeated and patterned practices used by media workers to cope with their jobs while serving the needs of the organization;

3. Organizational: Forces impacting the content come from the policies that ensure the goals of a media organization are achieved and the interests of the owner are served;

4. Extra-media/Social institutional: Forces come from interested parties such as sources, government, audience, and advertisers. Competition, market trends, and technology can also have an impact on content;

5. Ideological/Social system: Ideological/social system forms the foundation for how media content is produced in the first place by dictating the interactions of social institutions, ownerships of media organizations, media routines, and also the values of journalists. It ensures the media perpetuates the status quo and interests of the power elites.

The model is relevant to this study in several aspects. First, it allows the coverage of Najib’s visit to China to be examined more systematically: the author is able to identify the sources of influence based on the tiered framework. For example, Jason Abbott (2011) offered three explanations for the pro-government bias in the Malaysian media: legislative checks on freedom of the press, structural or institutional constraints, and cultural or environmental constraints. With the Hierarchy of Influences model, this would translate into influences from the social institution (legislative checks), organization (structural or institutional constraints), and social system (cultural or environmental constraints). Yang and Md. Sidin (2016) have argued that the diverse points of view held by Malaysia’s newspapers in different languages are rooted in different political beliefs and institutional practices. This denotes forces from the owners with different political beliefs and the audiences they target (social institution), which in turn affect practices such as reporting policy (organization) and editorial decisions (routine).

Second, the model provides a comprehensive explanation of the nature of media content by taking into account the “multiple forces that simultaneously impinge on the media and suggest how influence at one level may interact with that at another” (Shoemaker and Reese 2014, 1, cited in Reese and Shoemaker 2016, 396). The argument that the social system is the most powerful influence on media content also corresponds with the concept of representation, which contends that meaning-giving is a practice rooted in the cultural and political context of society (Hall 2005). Ultimately, the framework that places media content in a social context is consistent with the intent of the present study, which seeks to understand the impact of Malaysia’s sociopolitical construct on the news-making process.

Methodology

The study was conducted qualitatively in two stages. First, content analysis was carried out to uncover the extent and patterns of coverage, as well as the resulting representations of China. In the second stage, in-depth interviews were conducted with media practitioners to get their explanation for the findings recorded in the content analysis phase.

The samples were news stories about Najib’s visit to China, which took place between October 31 and November 5, 2016. They were collected using the purposive sampling method from six primetime newscasts on free-to-air television:

1. TV3’s Buletin Utama (Malay)

2. 8TV’s 8TV Mandarin News (Mandarin)

3. ntv7’s 7 Edition (English)

4. TV1’s Nasional 8 (Malay)

5. TV2’s TV2 Mandarin News (Mandarin)

6. TV2’s News On 2 (English)

TV3, 8TV, and ntv7 are private television channels operated by Media Prima, whereas TV1 and TV2 are run by the public broadcaster RTM. The bulletins were chosen for their prominence as well as practical reasons: Buletin Utama has the highest viewership, 8TV is the number one Chinese channel, and the now ceased 7 Edition was the only English bulletin aired during primetime (Chua 2018; Media Prima 2020). Malay, Mandarin, and English news programs from RTM stations were selected so that a comparison could be made between the coverage on commercial television and that on public television.

To gather the samples, the author visited the bulletins’ online archives: RTMKlik (https://rtmklik.rtm.gov.my) for news on TV1 and TV2, and Tonton (www.tonton.com.my) for news on TV3, 8TV, and ntv7. The sampling period was set between October 24 and November 12, 2016—one week before the visit and one week after. Newscasts within the sampling period were watched from beginning to end to scour the coverage of the visit. Relevant stories were recorded using a camera and labeled according to their dates, channels, and topics. The duration of these stories was also calculated.

The research continued with a close reading of the content of the samples. The focus was to uncover the patterns or characteristics of coverage, and also how China was represented as a result. The former could be detected by identifying the organizing ideas in the stories that helped the audiences in “making sense of relevant events, suggesting what is at issue” (Gamson and Modigliani 1989, 3), while the latter could be discovered through the themes arising from “patterned response or meaning” about China in the stories (Braun and Clarke 2006, 82). The unit of analysis was individual news stories. The author viewed the footage repeatedly to achieve immersion and took note of the clues and insights that emerged from the stories. Specific attention was placed on the narratives, namely, what was conveyed verbally by the news presenters; but other elements such as tone (excited or neutral), presentation style (descriptive or straight), and visuals (captions or expressions) could also be taken into account when applicable. During data collection, the data was also analyzed. For qualitative research, this is standard and even crucial because it can help in “adding to the depth and quality of data analysis” (Vaismoradi et al. 2013, 401).

To get more accurate findings, the coverage of the various news programs was compared and contrasted. This was intended to uncover news frames that normally appear natural to the audience and are hard to detect unless a comparison of narratives is carried out (Entman 1991, 6), disclosing “what stories, stakeholders and frames are included and excluded . . . and to what effect” (Seib and Powers 2010, 10). The procedures were repeated until saturation was reached and no new information or theme was recorded. Finally, the themes about China that had been collected were sorted to ensure only those containing the “essence” that captured a particular aspect of the data remained (Braun and Clarke 2006, 92). They were then calculated to find out their frequency of appearance. This step helped unveil the salience of the themes, which reflected not just China’s representation in the coverage but also the overall reporting pattern of a bulletin on the topic.

Finally, to substantiate the findings of content analysis, the study continued with in-depth interviews with media practitioners who possessed firsthand experiences in television newsrooms. A total of four semi-structured interviews were conducted.

The outcome of the study will be presented in the next section.

Results: Content Analysis

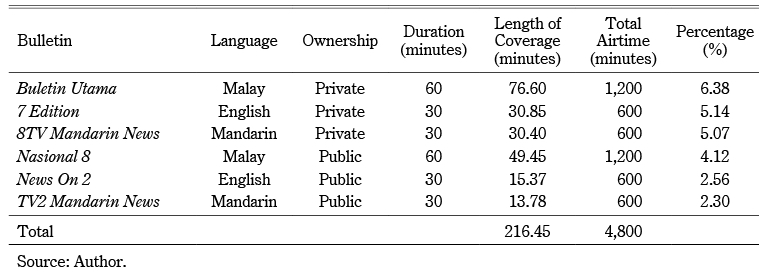

A total of 216.45 minutes of coverage related to Najib’s visit was collected between October 24 and November 12, 2016. It is worth noting that the airtime for the Malay news is 60 minutes, as opposed to 30 minutes for the English and Mandarin news. Table 1 shows the amount of coverage given to the visit in the total airtime of each bulletin, which is obtained by multiplying their respective durations by the 20 days that cover the sampling period. The news programs on private television offered significantly more coverage than their public counterparts, with 137.85 minutes (63.69 percent) compared to only 78.6 minutes (36.31 percent) by the latter. By linguistic line, the Malay newscasts contributed the bulk of the coverage with 126.05 minutes (58.24 percent), the English newscasts dedicated 46.22 minutes (21.35 percent), and the Mandarin newscasts offered the least with 44.18 minutes (20.41 percent).

Table 1 Amount of Coverage of Najib’s Visit to China between October 24 and November 12, 2016

Overall, the portrayal of China in the coverage was positive because the messages contained in the majority of the stories were favorable to China’s image. As demonstrated in Table 2, the messages that contribute to the shaping of China’s representation can be categorized into 11 themes. A single news story can carry more than one theme at the same time.

Table 2 Themes of China’s Representations in the Coverage of Najib’s Visit to China

| Themes | Implications | Representative Quotes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Economic importance | A country important to Malaysia’s economy | “China has been Malaysia’s largest trading partner since 2009.” (ntv7 2016b) |

| 2. | Strategic partner | A country Malaysia shares extensive and strategic cooperation with | “. . . the cooperation is not limited only to politics, economy and investment but also in the sectors of science, social, defence and security.” (TV3 2016a) |

| 3. | Close friend | A country Malaysia shares a good relationship with | “China’s relations with Malaysia as being as close as lips are to teeth.” (ntv7 2016a) |

| 4. | Geopolitics | A country that is involved in the region’s geopolitics | “China appears to be assertive in the South China Sea issue.” (TV3 2016c) |

| 5. | Sovereignty issue | A country associated with Malaysia’s sovereignty issues | “. . . several agreements signed by Prime Minister Datuk Seri Najib Tun Razak with China might jeopar- dize Malaysia’s sovereignty.” (ntv7 2016c) |

| 6. | Governance issue | A country associated with Malaysia’s governance issues | “. . . embrace China after the US Department of Justice announcing seizure of assets and investigation on 1MDB for allegedly involving in money laundering.” (8TV 2016c) |

| 7. | Advanced country | A country with modern, innovative technologies | “In China, even loan is made online . . . the approval is done within three minutes and repayment within one minute, without any interface with humans.” (TV1 2016d) |

| 8. | Economic power | One of the world’s eco- nomic powerhouses | “China is seen as an economic power and is expected to become the largest economy in the world by 2050.” (TV3 2016e) |

| 9. | Superpower | One of the world’s superpowers | “China as a superpower is confident with Malaysia’s prosperity and political stability.” (TV3 2016e) |

| 10. | Competitor | A fearsome rival for Malaysian businesses | “China as an economic giant with giant companies, how are Malaysian companies going to compete?” (8TV 2016f) |

| 11. | Courtesy | A country that respects Malaysia | “. . . a country that has a lot of respect for us.” (TV1 2016a) |

Source:Author.

Among these themes, “economic importance,” “strategic partner,” “close friend,” “advanced country,” “economic power,” “courtesy,” and “superpower” are likely to give China a positive portrayal, whereas “geopolitics,” “sovereignty issue,” “governance issue,” and “competitor” are likely to give China a mixed or negative portrayal. Nevertheless, all of the themes can give China a positive, negative, or mixed portrayal depending on the context of the story. In general, China’s positive representation in the coverage is contributed to by the dominant presence of “economic importance” and “strategic partner” themes, even though “strategic partner” is a less substantial theme in the RTM newscasts.

The representation of China in the coverage of the visit on public television was overwhelmingly positive. Since public television is the government’s media, its reportage was based on the positive official view of the relationship between Malaysia and China. Most of the themes related to China in the stories were positive. To illustrate, in a report under the “economic importance” theme featured on all three RTM newscasts on November 6, Minister of Plantation, Industries and Commodities Mah Siew Keong was seen saying:

China is the second-largest importer of commodities, exceeding RM15 billion last year. In Malaysia, there are more than 1 million smallholders . . . so China is a very important market for all of our commodities; we want to sell more to China. (TV1 2016e; TV2 2016g; 2016h)

The report highlighted China’s importance to Malaysia’s economy, hence presenting a positive image of China.

Another example would be a story from News On 2 about Najib’s trip to the Gu’an New Industry City on November 2. In the report, the city was reported to be a former agricultural area that had been transformed into an international industrial development powerhouse focusing on the five clusters of aerospace, biomedical, high-end equipment manufacturing, e-commerce, and modern services industries. The audience was also informed that JD.com’s sorting center in Gu’an had the capacity of sorting 300,000 JD.com orders daily (TV2 2016a). By underlining the innovative features of the city, the story took on an “advanced country” theme and contributed to a positive impression of China as a country with advanced technology.

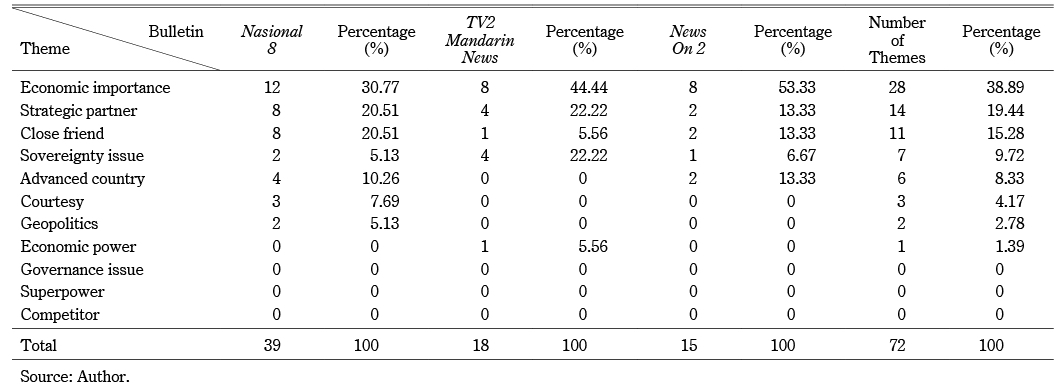

Even so, the representation of China in the news programs varied from one to another despite the programs belonging to the same RTM network. It appears that China’s portrayal was decidedly positive in the Malay and English bulletins and much more neutral in the Mandarin bulletin. This follows the higher ratio of “economic importance” stories in the English news, “close friend” and “courtesy” stories in the Malay news, and “sovereignty issue” in the Mandarin news (Table 3). The difference is also contributed to by the angle of coverage and the amount of details provided.

Table 3 Frequency of Appearance of Themes Related to China in the Coverage of Najib’s Visit to China (Public TV)

For example, in the coverage of Najib’s travel to Tianjin on November 3, TV2 Mandarin News merely reported that he and the delegation “took high-speed rail (HSR) and reached Tianjin from Beijing in only 30 minutes,” as opposed to Nasional 8, which offered details such as it “took only 30 minutes compared to 90 minutes using the highway” and “among the fastest in the world,” besides claiming that the “renowned HSR has demonstrated the ability of Chinese technology amid its effort to bid the HSR project between Kuala Lumpur and Singapore” (TV1 2016c; TV2 2016b). As a result, China received a more positive representation in the latter compared to the former.

Such contrast can be seen also in the November 4 reportage about the appointment of the founder of Alibaba Group, Jack Ma, as Malaysia’s digital economy adviser and the launch of Malaysia Tourism Pavilion on Alibaba’s e-commerce platform for tourism. In News On 2, the story came with visuals of Jack Ma paying a courtesy call on Najib and friendly interaction between him and the Malaysia delegation, in addition to him saying, “Malaysian people are very friendly, very inclusive, they’d love to make friends” (TV2 2016f). Coverage of the same event by TV2 Mandarin News, on the other hand, reported that the Pavilion was a platform to attract Chinese tourists to Malaysia and that Alibaba was actively expanding its presence in the ASEAN market of 600 million people, where the digital economy was projected to reach USD200 billion by 2025 (TV2 2016d). Because of this difference in angle, China appeared to take on the image of a “close friend” in the former and a “strategic partner” in the latter.

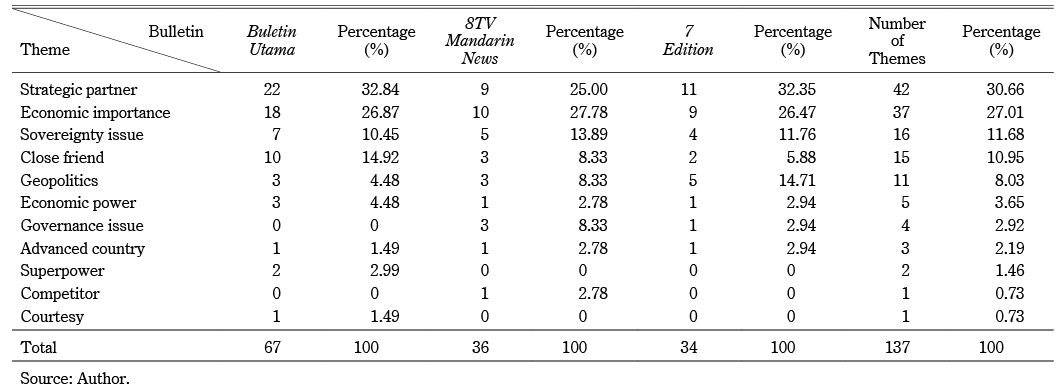

On private television the representation of China was positive, albeit to a lesser extent. This was due to more variety in the messages and focuses of coverage of China, with themes not seen in the formal and comparatively monotonous reporting on the national broadcaster (Table 4). The country was portrayed positively in the Malay news and in a more mixed manner in the Mandarin and English news.

Table 4 Frequency of Appearance of Themes Related to China in the Coverage of Najib’s Visit to China (Private TV)

In 8TV Mandarin News, the coverage focused on the trade and economic aspect of the visit, as well as the contentious issues related to the deals signed during Najib’s trip. As a result, although China received positive representation in stories that highlighted its “economic importance,” such as one on October 31 about the mission to increase palm oil exports to China (8TV 2016a), the favorable portrayal can be discounted by the bulletin’s heavy feature of news concerning the controversy surrounding the deals signed. For example, in a story about the ECRL project on November 2, the opposition leaders claimed that the project was signed with China without going through the necessary studies and that at RM92 million per kilometer, the cost was ridiculously high compared to even the allegedly most difficult railway to build, the Qinghai-Tibet Railway, which cost RM17 million per kilometer (8TV 2016d). The report suggested a “governance issue” was involved and tended to give China a negative portrayal because it associated the country with dubious approval and costing of the ECRL project.

In 7 Edition, the representation of China was also mixed following the bulletin’s geopolitical and strategic focus in the coverage. To illustrate, the former premier was seen in a story on November 5 telling the Malaysian diaspora and students in Beijing that he believed Malaysia would benefit from China’s rise under the strong leadership of President Xi (ntv7 2016d). While reports with a “geopolitics” theme like this tend to cast China in a positive light, others give a rather mixed image of the country as they imply superpower rivalry and territorial disputes in the region. This can be seen, for instance, in a story on November 5 in which the author of the book When China Rules the World, Martin Jacques, suggested that Malaysia “think more strategically” about what it wanted from its relationship with China before embracing the BRI (ntv7 2016e), and another report on November 2 in which Najib was reportedly “telling off former colonial powers not to meddle in the internal affairs of their former colonies” and that he had “acquired China’s commitment to protect and defend the sovereignty of the separate states” (ntv7 2016b).

In Buletin Utama, China enjoyed positive representation due to coverage that stressed the benefits Malaysia could receive from its close relationship with China, as well as the justification for the deals signed during Najib’s visit. To illustrate, in a story on November 5 with “economic power” and “superpower” themes, a commentator was seen asserting:

China is expected to become the largest economy in the world by 2050. It will play an important role in 10 or 20 years to come, so Malaysia doesn’t want to be left out. Now the son of Tun Abdul Razak [Najib’s father, Malaysia’s second prime minister] is opening the door for Malaysians to take part in China’s greatness. (TV3 2016e)

Buletin Utama also featured UMNO leaders refuting the opposition’s selling-off allegations, an approach not seen in Nasional 8 that used government officials for the same purpose. For example, in a report on November 6, the party’s Supreme Council member Tajuddin Abdul Rahman stated that the Chinese merely financed the projects and gained profit as a contractor, just like the foreign investors brought in by Mahathir to develop Langkawi into a tourist destination (TV3 2016f).

As in the case of RTM, the representation of China in the coverage on the commercial channels was similarly affected by the choice of details offered to the audience. For instance, in a story by 8TV Mandarin News on November 5, UMNO Information Chief Annuar Musa noted that the deals inked during Najib’s visit were “something to be proud of because not every country gets such opportunity, yet it has been interpreted as selling off the country. Since when did trade between two countries become selling off the country?” (8TV 2016e). Buletin Utama also had the same story, albeit with a longer quote ending “the trade between Malaysia and China has been going on for hundreds of years yet the country has not been sold off” (TV3 2016d). The latter would give a more positive portrayal of China compared to the former.

Such a situation can also occur with two bulletins on different networks covering the same event. For example, a story from News On 2 on November 3 about Deputy Prime Minister Ahmad Zahid Hamidi clarifying that the move of bringing in Chinese investments would not threaten Malaysia’s sovereignty concluded with him quoted saying “Malaysia-China relations were over 40 years old, but the question of sovereignty being threatened had never arisen” (TV2 2016c). In 7 Edition, however, the same story ended with Mahathir reportedly claiming that “the agreements could send the wrong signal to China on the dispute between the two countries pertaining to the South China Sea” (ntv7 2016c). As a result, China took on a positive “close friend” image in the former and a negative image in the latter as a country involved in the “sovereignty issue” and “geopolitics” that affected Malaysia.

On both public and private television, stories with a “close friend” theme that gave China a favorable depiction were featured more prominently in the Malay news programs. An example would be a Buletin Utama report on November 2, in which Najib recounted him asking his father (second Prime Minister Abdul Razak Hussein) why he was so confident about establishing ties with China, to which his father answered: “Because Zhou Enlai is a trustable man” (TV3 2016b). This is in addition to “courtesy,” a theme exclusive to Malay newscasts that has the potential to strengthen China’s positive image among Malay viewers. It can be seen, for example, in a story about the purchase of Littoral Mission Ships by Nasional 8 on November 2, where Defense Minister Hishammuddin Hussein claimed it was done “with a country that has a lot of respect for us” (TV1 2016a).

When it comes to messages that can affect China’s image negatively, the “sovereignty issue” is a clear theme capable of hampering China’s overall positive representation in the coverage. It appeared mainly in stories related to the “selling-off” controversy raised by the opposition leaders who argued that the deals worth RM144 billion signed with China could jeopardize Malaysia’s sovereignty. The issue was covered by all six bulletins and was sometimes reported along with geopolitical issues under the “geopolitics” theme, particularly the South China Sea dispute. To illustrate, 8TV Mandarin News reported on November 2 that “With Malaysia awarding contracts of many mega projects to China, the government getting loans from China, both countries strengthen defense cooperation, the opposition members of parliament worried that Malaysia would become a puppet state of China” (8TV 2016b). In another example, Buletin Utama reported on November 3 that Mahathir “expressed concerns about the impact of over-reliance on borrowings from a single source such as China, besides claiming China appears to be assertive in the issue of overlapping claims in the South China Sea” (TV3 2016c).

The coverage of the controversy on public television was far briefer. It was reported by Nasional 8 on November 3 as “certain parties claiming that several agreements Prime Minister Najib Razak signed with China might be able to jeopardize the country’s sovereignty” (TV1 2016b). In News On 2, it was merely referred to on November 3 as certain individuals “spreading stories that national sovereignty was at stake with the signing of the MOUs” (TV2 2016c). TV2 Mandarin News was the most detailed of the three. For instance, its story on November 4 reported that “former Prime Minister Mahathir criticized Prime Minister Najib for piling up debt, notably the RM 55 billion ECRL project signed with China may seriously impact the country’s sovereignty” (TV2 2016e).

As illustrated in Table 4, other stories with “negative themes” that could challenge China’s favorable portrayal in the coverage of the visit were also found on private television only. For instance, in a “governance issue” story on November 2, 8TV Mandarin News cited a Reuters report claiming that Najib’s pivot to China was driven by the US Department of Justice’s investigation into 1MDB over alleged involvement in money laundering activities (8TV 2016c). Another report under the same theme by 7 Edition on November 7, on the other hand, quoted an opposition member of parliament arguing that the ECRL project was a move to bail out the 1MDB debt crisis (ntv7 2016f). Lastly, 8TV Mandarin News also had a story with the “competitor” theme on November 6 about the business community calling on the government to ensure that “Chinese companies are coming to Malaysia as partners instead of competitors” (8TV 2016f). These reports to some extent reflected the concerns arising from China’s growing presence in the country. Overall, 8TV Mandarin News offered the most extensive coverage of the contentious issues related to Najib’s visit. Interestingly, such news was absent from Buletin Utama, where the focus was on defending the government’s policy, hence giving China a positive portrayal instead.

Results: In-depth Interviews

Discussions with the informants revealed that several factors contributed to the differences in how the news programs reported on Najib’s visit to China, which in turn affected how China was represented in the coverage. The outcome supported the proposition of the Hierarchy of Influences model and showed that reportage is a product shaped by five levels of forces coming from individual media workers, media routines, media organizations, extra-media/social institutions, and the ideological/social system. The following section presents information shared by the informants according to the model’s framework. For the sake of confidentiality, the informants are referred to as Informant 1, Informant 2, Informant 3, and Informant 4.

Influence of Individual Media Workers

The respondents admitted that their personal experiences affected how they wrote a story, which in turn shaped the angle or focus of a report. Such influence has an even greater impact when it is in the form of shared experiences among a group of media workers. This was highlighted when a Mandarin news presenter explained why their coverage focused on business and trade instead of other aspects of the visit such as geopolitics, as had been done by the English news:

I’m not sure why, but we weren’t really interested in that. Maybe Chinese Malaysians are particularly concerned about the economy, trade, money, things like that. The direction is also decided by the mentality, attitude, and thinking of the people behind a news program. We report news from our [Chinese Malaysian] perspective. For people from the English or Malay background, their ways of thinking are different, and their concerns would be different too. For us, it is almost natural to pay more attention to topics related to the economy. Not just because the audience wants to see it, we also want to show news that we can relate to our audience. (Informant 2, interview with the author, November 22, 2018)

The response shows that the ethnic and cultural background of media workers plays a significant role in news making in a plural society like Malaysia. Interestingly, this also explains Mandarin newscasts’ greater willingness to report on the controversy surrounding Najib’s visit. This has to do with the news teams’ attitude toward journalism, drawing upon their experiences as Malaysians of Chinese descent:

Personally, I would like to compare the difference to a child trying to challenge the rules set by the adults. This is because for the local Chinese media, we are still hoping for fairness [amidst the country’s race-based policy]. In a TV station, we are actually divided along the racial line instead of the linguistic line, so it’s a representation of our country. For us, we hope to let our audience see more and know more. (Informant 2, interview with the author, November 22, 2018)

Influence of Routines

The influence of routines is manifested through the application of newsworthiness in news reporting. Given the backdrop of the study, which was inspired partly by China’s global media expansion efforts, the author asked the informants whether initiatives such as the MOU on media cooperation between RTM and CCTV (Malay Mail 2014) would have an impact on how China was reported in the news about Najib’s visit. All of the informants responded that they were guided principally by news values, including when covering China. They also claimed that there was no cooperation in news reporting between their newsrooms and Chinese media organizations. For instance, a former broadcast journalist remarked:

News values are most important. Yes, instructions [from the top management] or MOUs might contribute to what is being highlighted in the news, but most importantly, generally, it’s because of news values. It [Najib’s visit] is a must for us to report because it is a state visit. The purpose of MOU is to make news exchange easy; let’s say you want to share with me the news from China or you want to have news about Malaysia. Even so, it doesn’t mean we must use the content. (Informant 3, interview with the author, December 1, 2018)

Another influence at the media routine level is the gatekeeper. This is defined as individuals or procedures that do not only determine what stories get to reach the audience in the end but also how the messages are shaped, handled, and disseminated (Shoemaker et al. 2001). The styles and focuses of the news programs appeared to vary slightly from one to another in the coverage of Najib’s visit to China. On this observation, the informants noted that it had to do with gatekeeping decisions. For example:

This [difference in reportage] is due to the editorial arrangements made by the editors. The editors have the right to decide how they want to present the news. This is planned along with the policy of news coverage, the policy of the company, news values, and also instructions from the top management. (Informant 3, interview with the author, December 1, 2018)

Influence of Organization

The statement about the editors making their decisions based on company policies and orders shows that the gatekeeper carries out their duty as a representative of the company (Shoemaker and Reese 1996). It further points to the organizational-level influence on media content. There were several occasions when the power of the media owner was referred to by the informants. To start, all of them mentioned the need to follow company rules or risk losing jobs, demonstrating that they were subject to the organization’s reward system. Another case in point is RTM’s policy as the national broadcaster. According to the informants, the mission of RTM is to promote the government’s policies and inform the public; therefore, it avoids sensationalism in news reports. Besides, it is funded by taxpayers’ money, and advertising income has never been a concern. The case is different for private television, where advertising and other sources of funding are vital for sustainability. These ownership and funding factors are likely to be the cause for the differences in the extent and style of coverage between RTM and Media Prima stations, whereby the former appears to be more direct, formal, and shorter in general compared to the latter, which is more descriptive, sensationalized, and lengthy not just for audience appeal reasons but also because of the propaganda content that traces back to its UMNO ownership. This indicates news reporting is subject to the influence of the owner/funder.

Other policies also affected how RTM reported on Najib’s visit to China. For example, the state broadcaster uses news programs in different languages as a “platform” to reach out to different communities in the country. As one informant noted:

When covering some issues, they would use the Malay platform [bulletin] for certain matters, while in the Mandarin news they focus on something else. . . . If I want to push for my Chinese audience to understand a specific issue, I would extend my coverage of that topic on the Mandarin platform. (Informant 3, interview with the author, December 1, 2018)

The comment sheds light on some of the attributes observed in RTM bulletins’ reportage. For instance, the highlighting of the “sovereignty issue” theme in TV2 Mandarin News was likely caused by the intent of clarifying the selling-off claims and stressing the economic importance of the visit to the Chinese audience, just as the underlining of Malaysia-China friendship and partnership in Nasional 8 could be motivated by the intention of showing the close relations between the two countries to the Malay audience.

Notably, RTM’s foreign news coverage is based on the principle of Malaysia’s foreign policy of maintaining good relations with all countries, as one informant revealed:

We cannot come up with reports that contain negative elements about China or other countries because sensitivities also exist in the relations between two countries, so the rule of thumb is to report only what is happening without going into the details. (Informant 4, interview with the author, December 5, 2018)

Although this policy of RTM applies also to other countries and is not limited to China specifically, it might help to explain the limited amount of news under the “sovereignty issue,” “geopolitics,” and “strategic partner” themes in its coverage of Najib’s visit to China, given the negative connotations some of the stories might carry for China’s or even the Malaysian government’s image.

Stephen Reese and Pamela Shoemaker (2016) cited a study by Francis L. F. Lee and Joseph Chan (2008) on the increasing political pressure faced by the local media in Hong Kong following the handover to China and categorized it as an organizational level of influence. This seems to be the case for Malaysia as well, where a foreign government’s interference in local media coverage, should it occur, also takes place at the organizational level. One informant shared his knowledge on the matter:

The ambassador can meet with the foreign minister, deputy prime minister, or the prime minister to discuss and reach a decision on not to highlight a particular issue, and then we’ll get a letter from the government. You can’t stop social media from reporting about it, but for the government or conventional media, we’ll have to stop reporting about it. (Informant 3, interview with the author, December 1, 2018)

Influence of Extra-media/Social Institutions

The informants were frank about the presence of political influence in the news-making process at their organizations, which inevitably played a role in shaping the coverage of Najib’s visit to China. For example, they noted that the blatant government propaganda in Buletin Utama’s coverage was the result of UMNO’s intention to get voter support, and that being the most-viewed program on the country’s number one television station had made it susceptible to political influence. As a news presenter pointed out: “Because their reach is bigger. The mass market is their audience, the mass Malays are their audience, so influencing them means you influence the people” (Informant 1, interview with the author, May 23, 2018).

Audiences are another important social institutional influence on the coverage of Najib’s visit to China. It was often the first answer the informants came up with when asked about what contributed to the differences in the bulletins’ reports. They noted that news programs tailor their content according to their target audience. This means selecting news items that carry value and relevance for their respective communities. As one informant said of the observation that 7 Edition’s coverage was focused on geopolitical issues, 8TV Mandarin News on business and trade, and Buletin Utama on how the visit could benefit Malaysia:

The mass Malay or the rural Malaysians are not concerned about how China will affect the country in general in five years’ time, but they are thinking about how it will benefit them. It is very different the way people think, different groups of people think differently, that’s how we find the different angles [to report on the visit]. (Informant 1, interview with the author, May 23, 2018)

Influence of Ideological/Social System

The influence of the ideological/social system is rightly manifested through the way all of the six bulletins reported on Najib’s visit to China. The varying coverage styles are a testament to Malaysia’s plural society, where each community has its own concerns, culture, and thinking. Notwithstanding this, there is still a marked similarity in their coverage, with stories about the PM’s itinerary remaining at the center of their reporting. This indicates the presence of a “guiding hand” trying to control what the media reported about the visit. An informant’s disclosure confirmed this:

Correspondents, media, and reporters get information on what to highlight in coverage from the person in charge of the media during official visits. They have to follow the instructions given, but obviously their presentations would be different based on their in-house styles. (Informant 3, interview with the author, December 1, 2018)

Moreover, from the conversations with the interviewees, it could be easily observed that media control and self-censorship were accepted as part and parcel of working in the industry. It appears that the nature of Malaysian society, where racial and religious tensions are consistently present, is the primary reason that led them to subscribe to the notion of “responsible reporting.” This is epitomized in one informant’s comment on free media:

The real free media do report everything, but does that really matter? We have to look at the culture of Malaysia. Sometimes even if we come out with a balanced report, although it is true, it might still cause sensitivities, or even worse, this is what we don’t want to see. (Informant 4, interview with the author, December 5, 2018)

Limiting freedom of speech on the grounds of stability and harmony has been an ideology propagated at various levels of Malaysian society. Although the rule is often disregarded by politicians, who always seem to manage to evade disciplinary action for their offensive remarks, the ideology is promoted and abided by on the part of the media. This underlines how the media can act as a means of social control and help secure the interests of the power holder through perpetuating limited press freedom, thus proving the influence of the ideological/social system in shaping news coverage in Malaysia.

Discussion

This study examines the representation of China in Malaysia’s ethnically and linguistically divided social and media environments by looking into television news coverage of Najib Razak’s visit to China in 2016. The findings reveal that China enjoyed a positive representation in the coverage. This was especially true in the case of RTM, due to its role as the public broadcaster that communicates the Malaysian government’s view. On private television, China’s representation was largely positive but also more diverse, and in some cases mixed, as a result of the different styles and focuses of the bulletins. Interestingly, it turns out that the expansion of Chinese media under the Go Global initiative did not have much impact on how Malaysian television portrayed China in its reportage. Discussions with media practitioners indicate that the outcome was brought about by a mix of factors. The coverage affirms the presence of individual, routine, organizational, extra-media/social institutional, and also ideological/social system forces, as proposed by the Hierarchy of Influences model, in shaping coverage of the visit. It points to five implications, discussed in detail below.

First, the reporting was shaped by the ruling elites’ interests. Media coverage can reflect the views and expectations one country has from its relationship with another country or even act as an intermediary between states (Tortajada and Pobre 2011; Lalisang 2013). With the positive representation of China resulting from the dominance of stories with “economic importance” and “strategic partner” themes, the coverage of Najib’s visit to China implied an emphasis on economic and strategic gains in Malaysia-China relations, especially at a time when his administration was pressured by the 1MDB scandal and the need to ensure the survival of his administration (Elina and T. N. 2017). It supports the findings by Ch’ng (2016), Teoh et al. (2016), and Yang and Ponnan (2019), which showed economic interests being the focus of Malaysian media when covering diplomatic ties with China. The outcome attests to the goals of Malaysia’s China policy, which seeks to achieve economic growth, fulfill strategic and geopolitical interests, and ultimately maintain political legitimacy (Kuik 2015). It also demonstrates the continuation of the trend suggested by Bui (2017) and Wijaya and Bensa (2017), where China coverage was guided by state policies and interests.

Second, the coverage demonstrates the intention to create a positive image of China among Malay audiences, with the eventual goal being to secure voter support. This can be seen from the greater emphasis on the close relationship between Malaysia and China in the Malay news programs, both on public and private television, with a stronger presence of stories under the “close friend” and also the exclusive “courtesy” themes. Framing can promote public awareness or even shape public opinion toward a news topic (Iyengar et al. 1982; Entman 1991). The intention became more obvious given that the coverage of the visit by the Malay newscasts was lengthier than other newscasts. This shows a continuation of the pro-government slant in the Malay news, suggesting the attempt to garner Malay viewers’ approval for the government’s China policy and the government as a whole. Nonetheless, it is worth noting the slight difference between the positive representation of China by Nasional 8 and Buletin Utama: portrayal by the former was more of a direct result of RTM’s status as the national broadcaster communicating the government’s stand and Malaysia’s foreign policy, as opposed to the latter, whose portrayal was more of an outcome of political propaganda.

Third, the coverage demonstrates the government’s control of the media, cemented by restrictive laws and ownership structure. Additionally, it affirms the findings by Abbott and Givens (2015) and Yang and Md. Sidin (2016) about the variations in the extent of influence imposed upon different media outlets in the country. Taking the coverage on private television as an example, the noticeably pro-government bias in Buletin Utama indicates it was the most influenced, whereas the comparatively balanced and neutral reporting in 8TV Mandarin News suggests a lower level of interference. When this is placed against the focus of coverage of the bulletins, as seen in the former’s emphasis on the benefits Malaysia could receive from close ties with China so as to seek the Malay audience’s support for the government’s China policy, versus the highlighting of business and trade in the latter due to presumed Chinese Malaysians’ interest in the economy and anything “money-related” (Informant 2, interview with the author, November 22, 2018), it implies that the more influenced a bulletin is, the less able it is to cater to audience interest, as political agenda overtakes editorial independence. It also hints at the positive correlation between government control and the media image of China as proposed by Zhang et al. (2016). The 7 Edition reportage of Najib’s visit to China supports Abbott and Givens’ (2015) and Yang and Md. Sidin’s (2016) argument about the pro-government tone in Malaysia’s traditional English-language media, despite its being more moderate and less driven by party politics compared to its Malay counterpart. Furthermore, its focus on the geopolitical and strategic aspect of the visit is consistent with the point made by Ch’ng about English-language media’s emphasis on international power relations in its reporting, through which it underlines Malaysia’s perspective as a country “sitting at the intersection of a range of global relations” (Ch’ng 2016, 236).

Fourth, one should not overlook the insights offered by stories with minority themes. Amidst a flood of news that placed China in a favorable light, these stories with themes such as “sovereignty issue” and “geopolitics” shed light on the concerns that cast a shadow over Malaysia-China ties. The low visibility of these reports was likely caused by the meaning-fixing practice or deliberate interference of the ruling class so as to limit interpretations related to certain topics (Hall 2005). Even so, the mere act of reporting the issues might still benefit the public “in ways unintended by the communicators and unwelcomed by the policymakers” (Parenti 1986, 208). This is all the more relevant in the case of Najib’s visit to China: the selling-off controversy, together with the 1MDB scandal, is in fact part of a larger governance issue that plagues the country. Although mostly found on private television, it can be said that reports with “negative” themes are a showcase of how the Malaysian media put to use the limited freedom available, the very same practice that could not be discounted in the defeat of Najib’s administration in the 2018 general election.

Finally, it is possible for the local media to overcome the restrictions imposed by the authorities and influence content in a reverse manner. This is demonstrated in 8TV Mandarin News’ willingness to provide more reporting on the controversy surrounding the visit, which could result in a more mixed or even negative representation of China and the Malaysian government. This follows the revelation that the country’s ethnic inequality has driven local Chinese media practitioners to challenge the rules of the game and make informing audiences their mission (Informant 2, interview with the author, November 22, 2018). The observation proves the comparatively independent reporting culture of the local Chinese-language media (Abbott and Givens 2015; Yang and Md. Sidin 2015). It indicates that Malaysian media coverage of China does not always tie to national interests and can be of service to community interests as well. It also attests to the argument that representation is a practice taking place between members of a culture (Hall 1997). It would appear that such connections between media practitioners and their audiences are what contribute to the variations in how the Malay, Mandarin, and English news covered Najib’s visit to China. After all, a media practitioner coming from the same cultural background as the audience would be more likely to have the same worldview and use the same conceptual map when creating content. This underlines the role of culture in linking news production (journalists) and news consumption (audiences), and the fact that culture is as important as power in the making of news and media representations (Hall 2005; Van Gorp 2007).

Conclusion

The representation of China in Malaysian television coverage of Najib’s 2016 visit to China is positive, despite episodes of stories that carry negative connotations for China’s image. The outcome points to a state-dominated narrative, with instances of the press seeking to inform their audiences despite the restrictions they face. While “China” is an important element in the coverage of the visit, the portrayal of the country has not been much impacted by Chinese media’s Go Global efforts. Instead, it is shaped by the social, cultural, and political environments of Malaysia. In other words, the representation of China found in this study is a product of the local context created by multiple intertwined factors “as complex as Malaysian society itself” (Yeoh 2019, 416) rather than one influenced by Beijing’s interests.

It is unclear whether differences in the ways the news programs in this study cover China would have any implications on how different ethnic groups in Malaysia view China, and how that might impact society in the long run. This follows concerns about the potential effects of ethnically and linguistically divided media offerings on national integration (Amira 2006). Admittedly, this study is far from perfect. To start, there is the issue of subjectivity due to the methods used—content analysis, which involves subjective interpretation of data by the researcher (Hsieh and Shannon 2005; Wimmer and Dominick 2011), and in-depth interviews where the responses are built upon the subjectivity of interviewee and interviewer (Qu and Dumay 2011, 256). The representativeness is also limited because of the small sample size used and the exclusion of samples from pay television and Tamil-language news. Therefore, the outcome can hardly be generalized as the representation of China on Malaysian television as a whole.

Despite the shortcomings, this study has managed to achieve its objective of providing insight into the representation of China in Malaysia, as well as narrowing the gap in the literature, which needs more Southeast Asian perspectives. For future studies, it is recommended that this research be carried out on a larger scale to cover other news topics or sectors of the media industry for a more comprehensive picture of China’s representation. The study can also be replicated in other countries in the region to better understand how China is covered and perceived in these societies. Finally, it would be interesting to see a study being done on the influence of media on their audiences by looking at the relationship between choices of media outlets and perceptions of China.

Accepted: May 12, 2022

Acknowledgments