Contents>> Vol. 12, No. 1

Farmers’ Reactions to Compulsory Land Acquisition for Urbanization in Central Vietnam

Nguyen Quang Phuc*

*University of Economics, Hue University, 99 Ho Dac Di, Hue City, Vietnam

e-mail: nqphuc[at]hueuni.edu.vn

![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7660-0836

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7660-0836

DOI: 10.20495/seas.12.1_169

Land is a means of production, a source of income, a form of valuable property, and a space for life. When land is compulsorily acquired by the state for development purposes, farmers react in different ways to protect their land benefits. This paper relies on resistance theories, combining both quantitative and qualitative research methodologies in order to explore how farmers in Hue’s peri-urban areas reacted to the decisions of land acquisition for urban expansion. By exploring the multiple forms and the diverse outcomes of land reaction adopted by the farmers, the study contributes to the literature on responses to land conflicts in Vietnam and elsewhere. The results show that the complaint is a common reaction of many farmers in expressing their attitude toward compulsory land acquisition, while collection resistance or rightful resistance are rare in the studied villages. This might be due to several reasons, but losing land—while still staying in their own social and physical environment, within the more dynamic economic context—has a significant influence on the forms of resistance toward land loss. We argue that the existence of complaints is logical, reflecting social tensions on the ground. They are however not strong enough to influence any fundamental changes in local government decisions.

Keywords: urban expansion, land acquisition, compensation, land protest, Vietnam

Introduction

Economic development and population growth require space to accommodate housing, businesses, services, infrastructure, and other facilities. An early step in the process of providing such facilities is the acquisition of appropriate land (FAO 2008). In order to procure land, when and where needed, governments often use the mechanism of compulsory land acquisition. This process may ultimately bring benefits to society, but is disruptive to the people who are forced to surrender their land; it displaces families from their homes and farmers from their fields and income sources. If compulsory acquisition is satisfactorily carried out by the government, people are moved to equivalent situations/lands, while at the same time the intended benefits are still provided to society. If, on the other hand, compulsory acquisition is poorly executed, it may leave people landless, with unequitable compensation, and with no way of earning a livelihood. Not surprisingly, compulsory land acquisitions are often contested and frequently meet with popular resistance in countless parts of the world, as indicated by many studies (Han and Vu 2008; Walker 2008; Schneider 2011; Mamonova 2012). When faced with the prospect of losing land, reactions from individuals vary greatly and range from covert “everyday resistance” to overt “mass social movements,” in order to defend their interests.

In Vietnam, compulsory land acquisition is used by the government as a policy instrument to convert massive amounts of land for urbanization and industrialization (DiGregorio 2011; Pham Thi Nhung et al. 2020). It has been estimated that nearly 1 million hectares of agricultural land were transformed for non-agricultural activities between 2001 and 2010 (World Bank 2011); and nearly 630,000 households and 2.5 million people were affected by these processes (Mai Thành 2009). One of the consequences of land loss is social tension and resistance by the affected people (Han and Vu 2008). At the national level, 70 percent of the nearly 700,000 petitions sent to the authorities between 2008 and 2011 related to land deals (Thanh tra Chính phủ 2012). More serious protests, such as mass demonstrations and violence, have taken place in the largest cities. For instance, on the outskirts of Hanoi, Tho Da villagers resorted to violence to press for higher compensation (Han and Vu 2008). Also in the west of Hanoi, Lụa villagers rejected the state’s authority to unilaterally claim their cultivated land or sent their petitions to higher levels through collective protest (Nguyen Thi Thanh Binh 2017). In Hung Yen, a province in the Red River Delta, hundreds of people in the Van Giang District, having lost their land to the Eco-Park new urban project, organized mass demonstrations in Hanoi and Hung Yen (Nguyễn Hưng 2012). Thousands of households affected by the Thu Thiem Peninsula Project in Ho Chi Minh City refused the compensation offered, as it was far below the speculative market price (Hoài Thu 2009).

The above literatures suggest that land has become a burning political issue in Vietnam, especially in the largest cities. Land acquisition for urban expansion or development, and the reaction of farmers to land loss, remain a big concern of scholars from various disciplines. Recently, some works have been done on this topic in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City; however, more can be added to the literature to better understand the social context and the influence of geography, culture, and tradition on the reaction of people to land loss in various communities. Drawing upon the case of Hue—a medium-sized city in Central Vietnam, the study seeks to understand how famers have reacted to the decisions of local authorities to acquire their agricultural land for urban expansion.

This article proceeds as follows: after a short review of the literature on the everyday resistance theories, we will outline the research site and data collection methods, followed by an overview of land loss, compensation, and change in livelihoods of affected households, as well as farmers’ reaction to land loss found in Hue’s peri-urban areas. The last section offers discussions and conclusions.

Everyday Resistance Theories and Land Protests in Vietnam

Over the last decade, research on resistance has grown within fields that partly overlap; mainly subaltern, feminist, cultural, queer, peasant, and post-structural studies. Since James Scott wrote Weapons of the Weak (1985), a significant part of resistance studies has investigated the area of “everyday resistance.” This concept is used in this study to understand how famers in a Hue peri-urban village have reacted to land acquisition for urban expansion.

“Everyday resistance” is a theoretical concept that covers a different kind of resistance; one that is not as dramatic and visible as rebellions, riots, demonstrations, revolutions, civil war, or other such organized, collective, or confrontational articulations of resistance (Scott 1985; 1990). Everyday resistance is quiet, dispersed, disguised, or otherwise seemingly invisible; something Scott interchangeably calls “infrapolitics.” Scott shows how certain common behavior of subaltern groups (for example, foot-dragging, escape, sarcasm, passivity, laziness, misunderstandings, disloyalty, slander, avoidance, or theft) is not always what it seems to be, but instead resistance. He argues that these activities are tactics that exploited people use in order to both survive and undermine repressive domination; especially in contexts when rebellion is too risky (Vinthagen and Johansson 2013).

Since the introduction of everyday resistance, scholarly works on protests over land have applied this concept to understand the rural politics of peasants. In case of Java, Indonesia, Peluso (1992) used the model of everyday forms of resistance to illustrate the behavior of the Samin movement. The Saminists “refused” to speak to the foresters, or to any officials. They saw the forest officials as obstructions to their inherent right to forest wood and forest land. Some villagers would “lay down” on their land and cry out “Kanggo” or “I own it.” In the Philippines, Kerkvliet (1990) stated that villagers discussed, among themselves, various government policies and programs and the legitimacy or illegitimacy of the entire Marcos regime. They also debated access to land, grain, wages, and credit; how employers treated workers, and about other issues related to the control, allocation, and use of important resources. These are recognized as the political issues that permeate everyday village life (Kerkvliet 1990). Despite the characteristics of being quiet and rarely organized or direct, Scott (1985) argues that everyday resistance is the foundation for large-scale change by constantly foiling policies. It can lead to open and confrontational forms of resistance. Accordingly, farmers’ disaffection may be written down or expressed through open protests and organized petitioning (Kerkvliet 2009).

Vietnam has, for a long time, been a fertile land for studies on peasant resistance in which theories of moral economy, the rational peasant, or the power of the weak are introduced or elaborated (Nguyen Thi Thanh Binh 2017). Kerkvliet (2005) pointed out that Vietnamese farmers used “everyday forms of resistance” to express their attitude toward the collective farming cooperatives between the 1950s and 1980s. They often “cut corners,” doing things that did not comply with what authorities expected of them. In addition, unless a work team, assigned to fertilize planted fields, was closely supervised, they sometimes did the work sloppily to complete the task quickly and easily, rather than taking the job seriously. Whether they worked diligently or not, the farmers reasoned, they received the same number of work points, so they took the easy way out. Consequently, collective properties—such as land, work animals, and tools—were not well cared for, and yields amounted to less than what the country needed within the context of war requirements and rapid population growth. Kerkvliet (2005; 2009) concluded that everyday resistance without social upheaval, without violence, without a change in government, and even without significant organized opposition, nonetheless contributed to authorities rethinking cooperative programs and land policy. A similar effect was also found in communist governments in Laos, China, Eastern European countries, and in the Soviet Union (Kerkvliet 2009).

Despite the characteristics of being quiet and rarely organized or direct, Scott (1985) argues that everyday resistance is the foundation for large-scale change by constantly foiling policies. It can lead to open and confrontational forms of resistance (Kerkvliet 2009). However, certain transformation conditions need to be met for this to actually take place. This, firstly, comprises political circumstances that allow farmers and disadvantaged individuals to express their opinions. For instance, in Vietnam, various laws and regulations (The Land Law 2013, the Grassroots Democracy Decree No. 34/2007) have been promulgated, encouraging social organizations and citizens to participate in formulating, implementing, and monitoring policies at the local level. Secondly, the emergence of individual leaders and groups (e.g. civil social organizations) that are able to band villagers together in order to mold their actions and behaviors into powerful entities (Kerkvliet 2009). These conditions, as highlighted by Scott (1985) and Kerkvliet (2005; 2009) have changed the forms of farmers’ reactions to move from hidden to open forms of resistance (Schneider 2011). Scholarly works on protests over land have moved beyond the everyday resistance model to focus on a contestatory mode of politics—rightful resistance (Labbé 2011; Nguyen Thi Thanh Binh 2017). Rightful resistance, according to O’Brien, is a form of popular contention against the state in which groups of weak peasants use nonviolent methods. However, rightful resisters actively seek the attention of the elites, and their protests are public and open (O’Brien 1996). In China, for instance, people affected by land lost to urbanization expressed their discontent through rightful resistance. These included petitions sent to local authorities or face-to-face meetings with officials (Walker 2008). In peri-urban Hanoi, Labbé (2011) examines the resistance of villagers to land redevelopment projects and found that groups of villagers relied on a strategy of “rightful resistance” embedded in the official discourse of deference, inasmuch as they based their claims on official policies and ethical pronouncements by the Vietnamese party-state itself. Nguyen Thi Thanh Binh (2017) also applies rightful resistance theory to analyze why and how Lụa villagers protest. Lụa villagers went further by rejecting the state’s authority to unilaterally claim their cultivated land. They did it by showing their disagreement on land appropriation, demanding to retain the land to maintain their livelihood, or by not allowing the taking of land.

However, not all the cases of resistance in practice have applied “rightful resistance” to protest about land issues. The difference in socio-economic conditions as well as the extend of land loss between regions or between localities in which resisters live has led to different forms and scales of resistance (Savage 1987). In the studied villages, most forms of reaction to land loss correspond to what the everyday resistance theory describes of villagers reacting to protect their land rights. Therefore, everyday resistance theory is mainly applied in this study to better understand how famers in Hue’s peri-urban areas have reacted to the decisions of local authorities to take their agricultural land for urban expansion. This study is also a valuable contribution to the literature on responses to land acquisition in Vietnam and elsewhere.

Methods

Background: The Research Site

This study was conducted in Hue, a medium-sized city in central Vietnam. Hue is organized into 29 wards and 7 communes with a total area of 265,99 square kilometers. Due to the restrictions imposed by heritage conservation policy in the north of the city (the Citadel area), the core of Hue has mainly expanded to the south of city. The south has become the center of administrative bodies for the province and city, for tourism, and for residential areas. As a result, the administrative area of Hue increased from 71.68 km2 to 265.99 km2 in 2021 (Ủy Ban Thường vụ Quốc hội 2021). This process has created pressure regarding land use, especially in the peri-urban areas.

The peri-urban area, as defined by Simon et al. (2006), is a zone of direct impact—which experiences the immediate impacts of land demands from urban growth, pollution and the like, and a wider market-related zone of influence—recognizable in the handling of agricultural and natural resource products. The urban expansion of Hue has remarkably impacted the socio-economic transformation of peri-urban localities. First, there is the decline of agriculture, particularly planted areas and the production of the main crops such as rice, sweet potatoes, cassava, and vegetables. Second, the improvement of infrastructural systems and institutional innovations has significantly contributed to the establishment of business enterprises in various fields such as commerce, construction, manufacturing, the textile industry, etc. This has brought the local population many employment opportunities in non-farming sectors. Third, the peri-urban localities have become denser in recent years. The main cause of this upward tendency might be the growth of population in this area, the moving of urban citizens into peri-urban villages, and the influx of migrants from other parts of the country.

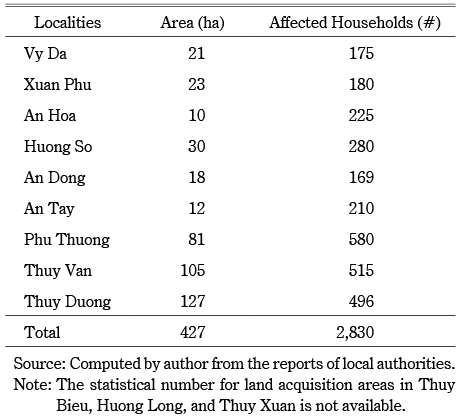

Land acquisition in Hue’s peri-urban areas is characterized mainly by the acquisition of agricultural land, after which the vast majority of affected households have remained in their original homes and received compensation money, while a limited number of households who lost their housing plots have resettled elsewhere within the same village or surrounding villages. It is estimated that 427 hectares of land in Hue’s peri-urban areas (over 80 percent of which was agricultural land) were acquired between 2000 and 2018 (HSO 2018). Nearly 3,000 households have been impacted by land acquisition processes. This process is predicted to expand in the coming years, when the urban development becomes more intensive.

Table 1 Compulsory Land Acquisition in Hue’s Peri-Urban Zones (2000–18)

According to the 2013 Land Law, households that have lost part or all of their land to urban expansion were compensated and supported for livelihood reconstruction. In principle, compensation and support for the losses consist of three main components: (i) compensation for land use rights; (ii) compensation for assets on current land; and (iii) monetary support for life stabilization and job change training (Land Law 2013). However, the amount of money paid depends on compensation rates, set yearly by the provincial governments, and depends on the locality in which the land is situated, the size of loss, and when the acquisition took place.

For this study, the author selected four peri-urban sites: Thuy Duong, Thuy Van, Phu Thuong, and Huong So, where most of the agricultural land has been acquired to build new urban developments such as An Cuu City, An Van Duong, Vicoland, Royal Park, Eco Garden Hue, etc.

Data Collection and Analysis

The research was carried out by using both quantitative and qualitative research methodologies. For the quantitative component, 170 households were surveyed by questionnaire to investigate the impacts of land loss. The questionnaire addressed three central areas, namely: (i) general household characteristics; (ii) the amount of land lost, the level of participation, and the compensation process; and (iii) changes in livelihood assets, livelihood activities, and livelihood outcomes. The surveys were done in early 2015. Sample households were randomly selected based on the land acquisition decision lists provided by local authorities. These interviews were mostly conducted with one or two household members (usually the husband and/or wife). The data from the household surveys was coded and analyzed using SPSS 22. For the qualitative component, 10 villagers were selected for the in-depth interviews. They were identified from the stories collected during the quantitative interviews that we believed played an important role or were directly involved in the reactions to land acquisition. The villagers were encouraged to share their reactions and participation in the response to land acquisition processes.

Land Loss, Compensation, and Change in Livelihoods

Loss of Land and Compensation

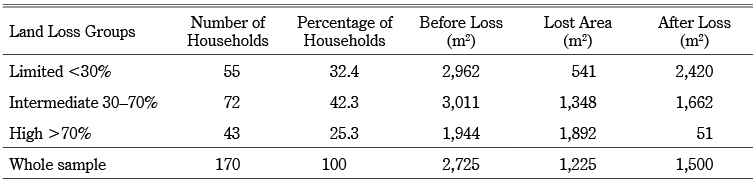

The household surveys show that the average area of agricultural land has decreased from 2,725 m2 to 1,500 m2 per household. In other words, the average household has lost nearly 56 percent of their agricultural land (or 1,225 square meters). Of the total number of households interviewed, 25.3 percent have lost over 70 percent of their agricultural land, 42.4 percent have lost between 30 and 70 percent, and 32.4 percent have lost less than 30 percent of their agricultural land.

According to the 2013 Land Law, households that lost part or all of their land were compensated and supported for livelihood reconstruction. Households received, on average, 26.8 million VND (1 USD=21,828 VND) in compensation. Furthermore, depending on the size of loss, households were supported for vocational training, as well as for funding to assist with occupational change. However, this type of compensation package was only awarded to households that lost between 30 and 70 percent (180 kg of rice per person for six months) and households that lost over 70 percent of their agricultural land (180 kg of rice per person for 12 months). In practice, all support was paid in a single cash payment without rice. Farm workers who lost their land use rights, on average, received between 1.8 and 3 million VND in support to assist with occupational change.

Change in Livelihoods

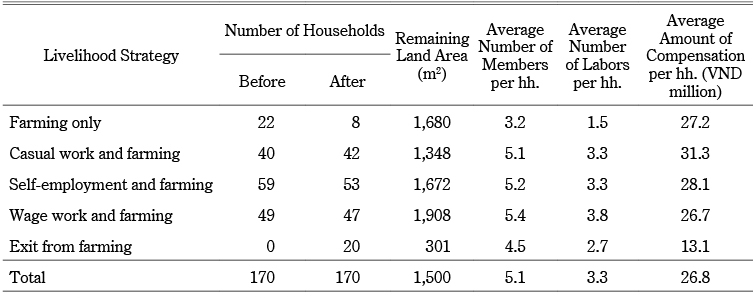

Looking at the ways in which households have coped with urban expansion and their main income source after land loss, we observed five key livelihood strategies: (i) farming only; (ii) a diversified livelihood where farmers combine casual employment and farming; (iii) a combination of self-employment with farming as a supplementary form of work; (iv) a diversified livelihood based on stable waged labor and farming; and (v) an exit from farming altogether.

Table 2 Comparison of Agricultural Land before and after Land Loss

Source: Nguyen Quang Phuc et al. (2017).

Table 3 presents some key characteristics of households, subdivided according to the five livelihood strategies observed. Some of these characteristics are in line with expectations; for instance, households exiting farming altogether are seen to have very little land left. Meanwhile, households continuing a livelihood focused on farming alone have in fact lost slightly more land than other groups. Most of these households, with an average number of 3.2 members, were relatively old, widowed, or no longer healthy enough to move into jobs outside of self-employed farming. The average size of the remaining land after appropriation amounts to 1,680 m2—generally not enough to provide an adequate livelihood based purely on farming. As a result, three out of eight households with a sufficient labor force leased additional agricultural land to pursue a strategy of intensification by combining rice cultivation for food supply with vegetable cultivation and livestock for markets.

Table 3 Household Livelihood Strategies before and after Land Loss

Source: Nguyen Quang Phuc et al. (2021).

Households basing on casual work and farming largely depend on casual work (day-labor) as the main income source. Casual work includes roles such as construction workers, motorbike riders, or lottery ticket sellers—these are jobs that are unstable, low-paying, and require little or no education. As a result of both land loss and tourism growth, the number of households applying the strategy of self-employment and farming (knitting, handicrafts, and small-scale trade) has increased from 28 to 41 people. Women often play an important role in this work; this may be due to the fact that self-employment tends to offer a relatively stable source of income that can be combined with other activities, especially work at home. Households pursuing the strategy of wage work and farming are represented by those who have more land than others, even after suffering land loss. The number of wage-laborers after land loss increased from 68 to 92 people. Most wage laborers in households pursuing the strategy of wage labor and farming are young people with marketable educational levels and social networks. They found work in Thuy Duong textile factories and manufacturing enterprises in Phu Bai industrial zones, as well as in tourism, government offices, and commercial centers.

In terms of household income, the results of the household surveys show that urban growth and land acquisition may not threaten the livelihood of affected households. Of the 170 households interviewed, 84.1 percent increased their income after land loss. The gross household income per household has increased significantly for the vast majority of households affected by land loss, from 64.4 (US$ 3,066) to 75.1 million VND (US$ 3,576). It should be noted that this result may be due to many different reasons, particularly job opportunities in an expanding local economy such as Hue, and losing farmland without displacement. Interestingly, while being forced to leave part or almost all of their farmland for urban expansion projects, the important role of farming as an income source is only slightly reduced. Farming income after land loss still contributes 15.3 percent to household income, compared to 26.8 percent before land loss. This indicated that farming appeared as a main source of food supply for household consumption.

Farmers’ Reactions to Land Acquisition for Urban Expansion

As stated by Scott (1985), Kerkvliet (2005), and Peluso (1992), everyday resistance involves little or no organization. It is done by individuals or small groups, and often occurs where people live and work. However, Scott (1985) also argues that everyday resistance is the foundation for large-scale change by constantly foiling policies. It can lead to open and confrontational forms of resistance. Looking at how villagers in the studied villages reacted to land loss, we observed four basic forms: (i) adaptation to the land acquisition but with complaint; (ii) acceptance land loss but “false declaration” to get more compensation; (iii) acceptance of land loss but “delaying” reception of compensation money; and (iv) open reaction through petitions and face-to-face questioning. Among these forms of reaction, the complaints took place more frequently than the remaining types of reactions. We now need to take a closer look at the main characteristics of four forms of farmers’ reactions to land acquisition.

Adaptation to Land Loss but with Complaint

We found that complaint is commonly used by almost all affected farmers to express their disagreement about land acquisition processes. “The topic of land loss and compensation appeared in our daily life. We complained to our friends, neighbors, or relatives about whatever we [were] dissatisfied [with]. The complaint took place at the accidental meetings, parties within family, hamlets, or communes. The complaint might not bring any benefit for us. It might only satisfy our discontent” (In-depth interview, male, 65 years, Thuy Van commune). Interestingly, the young people were less likely to care about what was going on. Conversely, the old people paid much attention to the consequences of land loss. Explaining their reasons, a 70-year-old widow in Huong So stated: “They [the young] were no longer attached to farming activities. Most worked in non-farm sectors and their lives were not much changed due to the land loss. They welcomed absolutely investors because they prefer urban lifestyles taking shape in villages. We [the elderly] might face numerous challenges in the life if there is insufficient social security and support from the government and our children.”

With respect to the main reason for complaints, the interviews showed that the inequality in compensation processes has become contentious issues among farmers. Nearly 93 percent of households surveyed contended that the compensation was unequitable and did not account for the increase in land values following the completion of projects. They argued that, when the construction of new urban infrastructure projects is completed, land prices will rapidly increase. None of this gain in value is shared with the people vacating the land in question. Moreover, compensation rates are also deemed unfair by land users due to the inconsistency across projects, administrative boundaries, and over different time periods. For example, one square meter of farm land in Xuan Phu Ward was compensated with 41,000 VND in 2010, while in Thuy Van Commune—a neighboring locality of Xuan Phu—the rate was only 19,000 VND per square meter. Even when projects are located in the same locality, compensation also differs for households who lost land in different time periods. In Thuy Duong, one square meter of farmland was compensated at 1,250 VND in 2004, but ten years later yielded 11 million VND per square meter. Therefore, some households received compensation amounting to tens of millions of VND, while others had to accept a much lower amount, depending on the timing of land conversion.

Additionally, the complaints originated from lacking of participation in the land acquisition process. Local governments usually play a dominant role in the decision-making process while the people who stand to lose their land and livelihoods generally are not part of such discussions. People were allowed to attend all formal meetings organized by the local governments; however their roles in practice were limited: they only listened to announcements and identified the land loss areas. They also did not have right to negotiate about the compensation rates or additional support. For those who are elderly, widowed, or disabled, their participation in the land acquisition process is even more limited.

“I am 79 years old and live alone. I am not strong enough to go to the communal people’s committee to get land acquisition information. I only know summary information provided by Mr. B (a neighbor)—that my family will lose 1,000 square meters of farmland for a new urban area to be built, Dong Nam Thuy An. However, I do not know anything about compensation rates and how to get it. The local authorities also do not invite me to attend the meetings.” (In-depth interview, Female, 79 years, Thuy Duong commune)

Lastly, the complaints also originated from the use of the concept of “public interest” (lợi ích công cộng) to justify the taking of land. In theory, the governments have the right to compulsorily acquire land from current land users for public interest and economic development (e.g. construction of public infrastructure, commercial centers, new urban areas, and resettlement areas). Accordingly, all land acquisition projects implemented in Hue’s peri-urban zones relate to public interest. This argument is advanced by governments who state that these projects deliver benefits to the majority of the population. Contrary to the government’s point of view, the majority of respondents question whether or not taking land can be justified as serving public interest. They argue that taking land does not serve the public at large, but rather the interests of investors and businesses. They believe that when the government transfers low-value agricultural land for high-value residential and commercial development, the investors and the state stand to obtain a massive profit from the increase in land prices. Conversely, the affected people are not satisfactorily compensated as they do not share in the increase in land values.

“We (villagers) accept the decision to acquire land for urban development, but we are not satisfied with the benefit-sharing mechanism between the investors and affected people. The fact is that the villagers do not benefit from the My Thuong new urban area. The beneficiaries are the investors. We are only compensated 21,000 VND per square meter for farmland while land then is being advertised in the media as construction land at the rate of 5 million VND per square meter. This is not fair! The state is taking land from the people (poor) to give to elite urban consumers and firms (rich). Is this in the public interest?” (In-depth interview, man, 62 years, Phu Thuong commune)

Acceptance of Land Acquisition Decisions but Attempt to Exploit Benefit from Compensation Packages through “False Declaration”

According to the 2013 Land Law, the Board of Compensation, Support, and Resettlement (BCSR) conducted surveys on land size and assets on land before compensation. Farmers were required to declare how much land was acquired, as well as to make a statement about their assets on land such as rice, vegetable, trees, houses, etc. These documents were then sent to the People’s Committee at the commune level and the BCSR for review. The BCSR prepared an overall compensation plan based on the results of the surveys.

The “false declaration” (khai báo sai) did not occur in Thuy Duong or Phu Thuong where only agricultural land (land use rights and rice crops) was lost. Conversely, it took place in Thuy Van and Huong So where both agricultural land and other physical assets were dispossessed in particular graves and tombs (mồ mả). The main reasons why “false declaration” appeared in Thuy Van and Huong So were: (i) that one grave (mộ thật) was compensated with 1.6 million VND which is equivalent to 84.2 times the compensation rate for one square meter of agricultural land; (ii) that local governments did not actually know the number of graves and tombs belonging to each family; and (iii) that the BCSR is not likely to excavate and check the graves, as this would be offensive to local beliefs and customs.

“One new road connecting Pham Van Dong with the Tu Duc—Thuan An Road was constructed in Thuy Van in 2013. Thirty-eight households had to move ‘mồ mả’ (real graves) from the local burial-ground to other places. According to the current land law, graves are recognized as land-related assets. Therefore, affected people have to declare them to local authorities when they are displaced by the land acquisition process. At this stage, some villagers sneak into the local burial-ground (nghĩa địa) at night to make fake graves (mộ giả), hoping to get more compensation money. Consequently, the declaration of villagers in the survey questionnaires is rather different from the real number of graves they own. Mr. T, the director of the Center for Land Fund Development1) of Huong Thuy District (CLFD) said at a meeting that: I cannot imagine! Graves in this locality spring up like mushrooms. More than forty persons die each night. However, the local authorities did not find a suitable solution. Therefore, the BCSR agreed to compensate the ‘fake graves’ created by villagers.” (In-depth interview, man, 56 years, Thuy Van commune)

Delaying Reception of Compensation Money

This form of reaction took place in Thuy Duong and Thuy Van Commune. The main reason for this occurrence was due to the provincial compensation framework, which results in low compensation and resistance. In many cases, the amount of compensation paid was not enough to buy an equivalent parcel of land in the same village (in the case of residential land), or not enough to buy the necessary food to sustain daily living (in the case of land loss in Thuy Duong).

“One square meter of farmland in Thuy Duong was compensated with VND 1,250. Some farmers complain that this is not enough to lease a similar area of land, or to buy a bowl of Hue’s beef noodle soup (tô bún bò Huế). Not agreeing with the compensation paid, 15 households affected by land loss for the Dong Nam Thuy An project delayed reception of compensation money (trì hoãn nhận tiền đền bù) from the BCSR. Eager to overcome this constraint and push ahead with its project, the investor—Investment and Construction Joint Stock Company No. 8 (CIC8), a state-owned company—was very flexible in seeking solutions. CIC8 provided financial incentives and valuable ‘gifts’ (TV, fridge, and electric fan) to land-losing households. In addition, community leaders such as heads of villages tend to ‘campaign’ in favor of land acquisition projects because local authorities receive one-fifth of the benefits from land conversion gained by the public sector. Thus, local authorities spending and community projects, to some extent, depend on revenue from land acquisition. Only after receiving additional benefits from the investor, and under pressure from local leaders, did those who delayed the reception of compensation money finally agree with the compensation rate offered by local governments? Only then could the transaction be concluded and did the BCSR disburse compensation packages.” (In-depth interview, man, 58 years, Thuy Duong commune)

Another reason for delaying reception of compensation money paid is that, the compensation methods in practice do not seem suitable, especially for displacement projects.

“Fifty-two households affected by an infrastructure project did not agree to move to the resettlement area. Although they accepted the land acquisition decisions, they delayed to get compensation packages from the BCSR due to two reasons: (i) almost all people preferred to relocate within the old locality, Xuan Hoa Village, where they lived for many years, and enjoyed good relationships with their neighbors; (ii) each household was allocated between 90 to 120 square meters to build new houses. This size, according to the villagers, is not enough for a new house and a vegetable garden, as they had before. Therefore, the people in question continue to wait for the provincial government to provide a suitable solution.” (In-depth interview, man, 47 years, Thuy Van commune)

Open Reaction through Petitions and Face-To-Face Questioning

A review of literature indicates that an increased number of petitions are being sent to the local authorities in recent years. It is rather difficult to obtain systematic information from the local authorities about the number or nature of such forms of popular reaction. The fact is that information related to “reaction,” “petition,” “complaint,” or “resistance” is often sensitive in the political system of Vietnam.

In the villages studied, the local annual reports showed that 120 petitions had been sent to the local authorities between 2010 and 2013 by households. Approximately 15 percent of the petitions (18 petitions) deal with land disputes, compensation, and resettlement. On average, there were five petitions related to land issues sent annually to the local authorities. With respect to the outcomes of open reactions, the local reports and interviews indicate that around 20 percent of the petitions (mainly relating to low compensation and unsuitable resettlement policy) have not yet been answered by those responsible for the land acquisition process. This is not surprising; the compensation framework is annually fixed by the provincial government; therefore, local leaders may not be in a position to directly answer the petitions or questions raised in meetings. For a final answer, farmers and local authorities have to wait for decisions from the higher levels of government.

Another type of open reaction is face-to-face questioning. This often occurs at meetings: (i) between the BCSR and households affected by land loss when they discuss the compensation plan; and (ii) between people and people’s councils which are organized twice a year at the communal level (Tiếp xúc cử tri). These meetings are perceived as important forums for local people to raise their concerns. However, face-to-face questioning is a rare practice in rural communities. Mr. H, a retired man in the commune of Phu Thuong who has participated in numerous meetings, explains this as follows: “people are often allowed to join the meetings but their role is relatively limited: attending and listening to announcements. A limited number of participants can raise questions. These questions mainly come from those who have a good educational background or access to relevant information.”

These above analyses illustrate that famers in the studied villages have used different forms of resistance to respond to compulsory land acquisition. While some people satisfy their discontent through complaints, others might obtain extra economic benefits through false declarations and delaying reception of compensation money or through petitions. Although everyday resistance is a more common form of reaction and is low-profile in nature, it has also created losses for investors and governments at the local levels (e.g., the time is not used towards solving problems, increases in compensation expenditure, and delayed projects).

Discussion and Conclusion

The case of Hue’s peri-urban areas allows us to draw a few key discussions and conclusions about farmers’ reactions to compulsory land acquisition. First, the result shows that complaint is a common reaction by many farmers in expressing their attitude toward land acquisition. The complaint is a safe method, flexible, and quite natural in everyday village life, where villagers can express their views and attitudes at any time. For those who want to seek safety first, the complaint is a safe choice. This trend is consistent with the findings found in other post-communist countries and in various post-Soviet countries, where power is controlled by a single party-state, where a process of institutional reform is happening, and where the role of rural associations is limited (Kerkvliet 2009).

However, the so-called “everyday forms of resistance” of famers found in the villages studied did not have much effect on changing the decisions of local governments. In the short term, they may only serve as an outlet for farmer to vent, and/or only bring immediate benefits to a limited number of farmers in the community—increases in compensation benefits through “false declaration” or by creating immediate losses for investors (e.g. increase in compensation expenditures or delayed projects) due to “delaying” the reception of compensation money. In the long term, we argue that everyday resistance may no longer be just a “weapon of the weak” for social demand-making. The existence of this form of resistance in everyday life is logical, reflecting social tensions on the ground. They cannot result in changes in the decisions of the local governments. This finding differs from conclusions offered by previous studies which showed that everyday forms of resistance of villagers in Vietnam, Laos, China, Thailand, and other countries influenced government policy (Stuart-Fox 1996; Kerkvliet 2005; 2009). In this sense, we argue that the compelling pressures for the change in the decision-making process in Hue or elsewhere might not come from everyday resistance, but from open resistance through collective actions such as those which took recently in Hanoi, Hung Yen, and Ho Chi Minh City.

The weakness of the farmers’ reaction in Hue’s peri-urban zones might stem from several reasons. First, the employment opportunities derived from urban growth in a medium-sized city like Hue may be relatively accessible to local people, even more so since the improvement of infrastructure, particularly the roads in the peri-urban areas, enables daily commuting between villages to city and industrial zones. Without this dynamic economic context, the livelihood options of the research population would have been far less positive (and of course, there would also have been less land conversion). It is the creation of alternative income sources, especially outside of agriculture, i.e., the demand for labor in the regional economy (construction, handicrafts for tourism, small-scale trade, textile factories, and manufacturing enterprises in industrial zones) that has enabled the successful reconstruction of the livelihoods for almost all of surveyed households. Livelihood outcomes after land loss are, overall, relatively positive, as evidenced by the fact that most of the affected households have been able to restore their pre-land-loss income levels. Second, the lost area per household is quite small—more than half of their agricultural land. Most of households still pursue diversified livelihoods after losing land by combining farming with non-farming activities as before urban expansion. In other word, peri-urban villages are no longer agricultural communities, though most households do value their link to farming. The ability to produce food for household consumption is viewed as a safeguard for the vagaries of the market, protecting one against outside risk. In this case, farming is considered not only as a “livelihood insurance” of the rural population, but it also makes households less vulnerable to urban expansion. As a result, the farmers affected by urban expansion easily accept the land loss. Third, the final reason in explaining the weakness of farmers’ reactions to land loss might come from historical, social, and cultural dimensions. Indeed, social life and characteristics of Hue people are profoundly affected by the ideology of feudal system under the Nguyen Dynasty (1802–1945) as well as the spirit of Buddhism. Accordingly, honesty, hospitality, and temperateness are salient features of people in Hue. They are often self-controlled people, and do not engage in intense conflict (Phùng Đình Mẫn 2008; Trương Tiến Dũng 2016). This is also why the complaint is a common form of reaction used by farmers in expressing their attitude toward land acquisition.

Whether everyday resistance or rightful resistance, the nature of farmers’ reaction is the first sign of social tension and might imply a failure of the top-down approach in land acquisition processes. This is a challenge in land governance for equitable and sustainable development. It can be tackled by strengthening institutions, enhancing the responsibility of local governments and investors in policy implementation, and in better involvement of affected people during decision-making processes.

Accepted: November 29, 2022

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the support of Hue University under the Research Grant No. DHH 2023-06-131.

References

DiGregorio, M. 2011. Into the Land Rush: Facing the Urban Transition in Hanoi’s Western Suburbs. International Development Planning Review 33(3): 294–319. https://doi.org/10.3828/idpr.2011.14.↩

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). 2008. Compulsory Acquisition of Land and Compensation. FAO Land Tenure Studies 10. Rome: FAO.↩

Han, S. S. and Vu, K. T. 2008. Land Acquisition in Transitional Hanoi, Vietnam. Urban Studies 45(5–6): 1097–1117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098008089855.↩ ↩ ↩

Hoài Thu. 2009. Tiền bồi thường Thủ Thiêm là bao nhiêu? [How much is the compensation for Thu Thiem?]. VnEconomy. July 1. https://vneconomy.vn/tien-boi-thuong-thu-thiem-la-bao-nhieu.htm, accessed on February 3, 2023.↩

Hue Statistical Office (HSO). 2018. Niên giám thống kê [Statistical yearbook]. Hue: Chi cục thống kê thành phố Huế.↩

Kerkvliet, Benedict J. Tria. 2009. Everyday Politics in Peasant Societies (And Ours). The Journal of Peasants Studies 36 (1): 227–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150902820487.↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

―. 2005. The Power of Everyday Politics: How Vietnamese Peasants Transformed National Policy. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

―. 1990. Everyday Politics in the Philippines: Class and Status Relations in a Central Luzon Village. Berkeley: University of California Press.↩ ↩

Labbé, D. 2011. Urban Destruction and Land Disputes in Periurban Hanoi during the Late-Socialist Period. Pacific Affairs 84(3): 435–454. https://doi.org/10.5509/2011843435.↩ ↩

Land Law. 2013. Luật đất đai. Hà Nội: Nhà xuất bản chính trị quốc gia Sự thật.↩ ↩

Mai Thành 2009. Về chuyển đổi cơ cấu lao động nông thôn sau thu hồi đất [About the transformation of labor structure after land acquisition]. Tạp chí Cộng Sản 15(183). https://www.tapchicongsan.org.vn/nghien-cu/-/2018/1003/ve-chuyen-doi-co-cau-lao-dong-nong-thon-sau-thu-hoi-dat.aspx, accessed January 24, 2023.↩

Mamonova, N. 2012. Challenging the Dominant Assumptions about Peasants’ Responses to Land Grabbing: A Study of Diverse Political Reactions from Below on the Example of Ukraine. Paper presented at the International Conference on Global Land Grabbing II, organized by the Land Deals Politics Initiative (LDPI), October 17–19.↩

Nguyễn Hưng. 2012. Hơn 160 hộ dân Văn Giang bị cưỡng chế thu hồi đất [More 160 households in Van Giang were compulsory acquired the land]. VnExpress. April 25. https://vnexpress.net/hon-160-ho-dan-van-giang-bi-cuong-che-thu-hoi-dat-2229379.html, accessed on February 3, 2023.↩

Nguyen Quang Phuc; van Westen, A. C. M.; and Zoomers, A. 2021. Land Loss with Compensation: What Are the Determinants of Income among Households in Central Vietnam? Environment and Urbanization ASIA 12(1): 40–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/0975425321990383.↩

―. 2017. Compulsory Land Acquisition for Urban Expansion: Livelihood Reconstruction after Land Loss in Hue’s Peri-urban Areas, Central Vietnam. International Development Planning Review 39(2): 99–121. https://doi.org/10.3828/idpr.2016.32.↩

Nguyen Thi Thanh Binh. 2017. Multiple Reactions to Land Confiscations in a Hanoi Peri-urban Village. Southeast Asian Studies 6(1): 95–114. https://doi.org/10.20495/seas.6.1_95.↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

O’Brien, Kevin J. 1996. Rightful Resistance. World Politics 49(1): 31–55. https://doi.org/10.1353/wp.1996.0022.↩

Peluso, N. L. 1992. Rich Forests, Poor People: Resource Control and Resistance in Java. Oakland: University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/california/9780520073777.001.0001.↩ ↩

Pham Thi Nhung; Kappas, M.; and Wyss, D. 2020. Benefits and Constraints of the Agricultural Land Acquisition for Urbanization for Household Gender Equality in Affected Rural Communes: A Case Study in Huong Thuy Town, Thua Thien Hue Province, Vietnam. Land 9(8): 249–268. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9080249.↩

Phùng Đình Mẫn. 2008. Bước đầu tìm hiểu tính cách người Huế qua văn hóa của xứ Huế [The first step to learn the Hue’s personality through the culture of Hue]. Tạp chí Tâm lý học 12(117): 1–4.↩

Savage, Mike. 1987. Understanding Political Alignments in Contemporary Britain: Do Localities Matter? Political Geography Quarterly 6(1): 53–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/0260-9827(87)90034-6.↩

Schneider, A. E. 2011. What Shall We Do without Our Land? Land Grabs and Resistance in Rural Cambodia. Paper presented at the International Conference on Global Land Grabbing organized by the Land Deals Politics Initiative (LDPI), April 6–8.↩ ↩

Scott, J. C. 1990. Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.↩

―. 1985. Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

Simon, D.; McGregor, D.; and Thompson, D. 2006. Contemporary Perspectives on the Peri-urban Zones of Cities in Developing Areas. In The Peri-urban Interface: Approaches to Sustainable Natural and Human Resource Use, edited by D. McGregor, D. Simon, and D. Thompson, pp. 1–17. London: Earthscan.↩

Stuart-Fox, M. 1996. Buddhist Kingdom, Marxist State: The Making of Modern Laos. Bangkok: White Lotus.↩

Thanh tra Chính phủ. 2012. Báo cáo số 1198/BC-TTCP tình hình, kết quả công tác tiếp công dân, giải quyết khiếu nại, tố cáo từ năm 2008 đến năm 2011 và giải pháp trong thời gian tới, ban hành vào ngày 16 tháng Năm năm 2012 tại Hà Nội, Việt Nam [Report No. 1198/BC-TTCP, which was released on May 16, 2012 in Hanoi, Vietnam, regarding the situation and results of citizen reception, settlement of complaints and denunciations from 2008 to 2011 and solutions in the coming time].↩

Trương Tiến Dũng. 2016. Biểu hiện của văn hóa Huế và Việt Nam qua một số sản phẩm lưu niệm ở Huế [Expression of Hue and Vietnamese culture through some souvenir in Hue]. Tạp chí Nghiên cứu và Phát triển 3(129): 115–125.↩

Ủy Ban Thường vụ Quốc hội. 2021. Nghị quyết số 1264/NQ-UBTVQH14 về việc điều chỉnh địa giới hành chính các đơn vị hành chính cấp huyện và sắp xếp, thành lập các phường thuộc thành phố Huế, tỉnh Thừa Thiên Huế, ban hành ngày 27 tháng Tư năm 2021 tại Hà Nội, Việt Nam [Resolution No. 1264/NQ-UBTVQH14, which is released on April 27, 2021 in Hanoi, Vietnam, regarding adjustment of administrative boundaries of district-level administrative units and arrangement and establishment of wards in Hue City, Thua Thien Hue province]. https://vanban.chinhphu.vn/default.aspx?pageid=27160&docid=203240, accessed January 25, 2023.↩

Vinthagen, S. and Johansson, A. 2013. Everyday Resistance: Exploration of a Concept and Theories. Resistance Studies Magazine No. 1: 1–46.↩

Walker, K. L. M. 2008. From Covert to Overt: Everyday Peasant Politics in China and the Implications for Transnational Agrarian Movements. Journal of Agrarian Change 8(2–3): 462–488. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0366.2008.00177.x.↩

World Bank. 2011. Recognizing and Reducing Corruption Risks in Land Management in Vietnam. Hanoi: The National Political Publishing House – Su That.↩

1) The Center for Land Fund Development is established at two levels: province and city/district. It is an important member of BCSR in preparing compensation and resettlement plans. It is responsible for controlling planned land areas for development projects and introducing planned areas for investors.