Contents>> Vol. 12, No. 3

Vocabulario de Iapon, a Seventeenth-Century Japanese-Spanish Dictionary Printed in Manila: From Material Object to Cultural Artifact

Patricia May Bantug Jurilla*

*Department of English and Comparative Literature, College of Arts and Letters University of the Philippines Diliman, Quezon City, Meto Manila 1101, Philippines

e-mail: pbjurilla[at]up.edu.ph

![]() https://orcid.org/0009-0009-2724-7330

https://orcid.org/0009-0009-2724-7330

DOI: 10.20495/seas.12.3_401

In order to survive, books in the Philippines have had to contend with multiple forces: the humid tropical climate, typhoons, floods, fires, earthquakes, termites, wars throughout the nation’s colonial history. This fact is often raised in studies on the history of the book in the Philippines, but how and why the book survives in spite of such conditions has hardly been given attention. Such a lacuna in Philippine book history is what this study seeks to fill. It explores the survival of Philippine incunabula (books printed from 1593 to 1640), with a focus on the transformation from material object to cultural artifact that the book undergoes in the course of enduring through the centuries. This study examines the case of the Vocabulario de Iapon (Japanese vocabulary), with a particular interest in the copy in the Bernardo Mendel Collection at the Lilly Library of Indiana University. The Vocabulario de Iapon, which was printed in Manila in 1630, is both typical and unique among Philippine incunabula for the circumstances it saw from its publication to its survival. It has much to tell about publishing in the Philippines in the seventeenth century, the reception of books through the ages, and the culture of collecting in modern times.

Keywords: Philippine book history, Philippine incunabula, survival of books, Japanese-Spanish dictionary

A great irony about the printed book is that each is created as an object among many exactly like it, yet it usually—if not inevitably—ends up becoming one of a kind. The manufacturing of a printed book renders it identical to the hundreds or thousands of other copies in its edition; its survival ultimately nullifies this uniformity and makes it unique. Once a book has been acquired, whether by an individual or by an institution, it is no longer—and will never be—the same as any copy that was like it. It gains a new and distinct character in both concrete and abstract forms—customized by its owner with labels, annotations, covering, or rebinding; and afforded a historical, cultural, or sentimental value. A book’s condition also adds to its distinction, and how it has stood the test of time is just as dependent on its owner who may have used and cared for it well or not, who may have kept it in an environment conducive to its preservation or not.

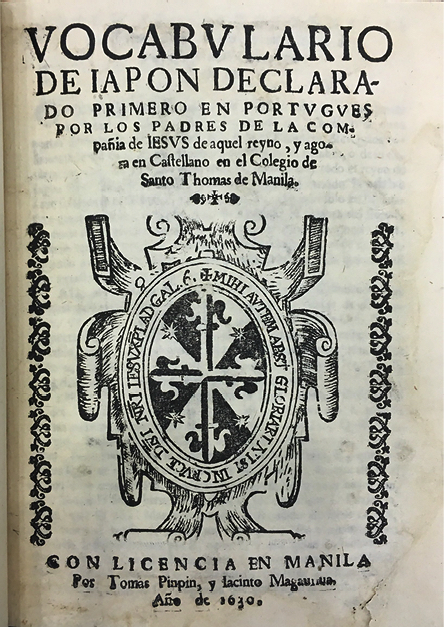

Rare old books display well this process of transformation from uniformity to uniqueness in the course of their survival.1) Some of these books further exhibit the progression from material object to cultural artifact, one that bears a special significance for a community, society, or country. Such volumes make for important study because they can deepen our comprehension of the survival of books, the last and the least understood event in the life cycle of the book, and ultimately broaden our knowledge on the book, culture, and history in general (Adams and Barker 2001, 37). Rare old books that have become cultural artifacts can reveal much about the publishing experiences and practices of their periods, the reception of books through the ages, and the culture of collecting in modern times. In this respect, and with reference to Philippine incunabula in particular—i.e., books printed locally from 1593 to 1640—Jacinto Esquivel’s Vocabulario de Iapon declarado primero en portvgves por los padres de la Compañia de Iesus de aquel reyno, y agora en castellano en el Colegio de Santo Thomas de Manila (Japanese vocabulary declared initially in Portuguese by the fathers of the Society of Jesus of that kingdom, and now in Castilian in the Colegio de Santo Thomas of Manila) (1630b) serves as a salient example. Of its surviving copies, that in the Bernardo Mendel Collection at the Lilly Library of Indiana University particularly stands out as a case that invites examination.

The Study of the Survival of Books and Philippine Incunabula

In 1993, as the history of the book was emerging and rapidly developing, Thomas R. Adams and Nicolas Barker proposed a new framework for the discipline in their manifesto titled “A New Model for the Study of the Book.” They identified the events in the life cycle of the book as publication, manufacture, distribution, reception, and survival. Of these five events, the last—survival—was the least studied at the time. The authors made the following observation:

The multiple forces which have worked and still work to allow books to survive for us to study so that we can have a “history of the book” at all are little understood, or rather their interaction within themselves and with the other factors which must be taken into account is little understood. (Adams and Barker 2001, 37)

It has been more than two decades since Adams and Barker presented their model, and the history of the book is a well-established and ever-growing discipline. The survival of the book is now better understood, as many studies have been conducted on various aspects of the subject—from book collecting in the Renaissance (Hobson 2012) to the plunder of Jewish private libraries during World War II (Grimsted 2004), from archival development in imperial Ming China (Zhang 2008) to the destruction of libraries from antiquity up to contemporary times (Raven 2004; Knuth 2006; Polastron 2007; Báez 2008). In the Philippines, however, not much is known or has been made known about the survival of books. It remains a little understood subject. On the one hand, this is not surprising, for the history of the book is still practically in its infancy in Philippine studies. On the other, it is startling, and disturbingly so, for the survival of books in the Philippines is a pressing matter.

Books in the Philippines have an almost ephemeral quality to them due to the conditions they are subjected to—the humid tropical climate, typhoons, floods, fires, earthquakes, termites, wars throughout the nation’s colonial history—and, generally, the inferior materials used in their manufacture. That the book has to contend with these multiple forces in order to survive is often raised in studies on Philippine book history, but how the book survives and why it does so in spite of such forces have hardly been given attention. Studies on Philippine incunabula, for instance, are generally descriptive bibliographies with a focus on the production and the physical elements of the books. Among these is P. van der Loon’s “The Manila Incunabula and Early Hokkien Studies” (1966), a survey of printing in Manila from 1593 to 1607 that examines six of the earliest Philippine imprints.2) There are also the monographs on early books, each with a facsimile of the volume it deals with: Edwin Wolf 2nd’s Doctrina Christiana: The First Book Printed in the Philippines, Manila, 1593 (1947); J. Gayo Aragón and Antonio Domínguez’s Doctrina Christiana: Primer libro impreso en Filipinas (Doctrina Christiana: the first book printed in the Philippines) (1951); J. Gayo Aragón’s Ordinationes Generales: Incunable Filipino de 1604 (Ordinationes Generales: Philippine incunabula of 1604) (1954); and Fidel Villarroel’s Pien Cheng-Chiao Chen-Chúan Shih-lu, Testimony of the True Religion: First Book Printed in the Philippines? (1986). All these studies are doubtless valuable for the information and insight they provide on Philippine incunabula, but the data or discussions they offer on the survival of the books are not comprehensive. Wolf, for instance, includes in his study just a brief albeit lively account of how the single extant copy of the 1593 Doctrina Christiana ended up in the collection of the United States Library of Congress in the 1940s.

The ground for the study of the survival of Philippine books, incunabula in particular, is not fallow. Along with the abovementioned works, which serve well as preliminary matter, the seminal bibliographies and printing histories of José Toribio Medina (1896; 1904), W. E. Retana (1897; 1906; 1911), Trinidad H. Pardo de Tavera (1903), and Angél Perez and Cecilio Güemes (1904) also provide essential information on the early Philippine imprints: what titles were printed, how and where they were printed, and what their physical characteristics were. It was Retana who determined the period 1593–1640 as the incunabula age of Philippine printing, based on the appearance in 1593 of the first locally produced book, the Doctrina Christiana, en lengua española y tagala (Christian doctrine in Spanish and Tagalog) (Plasencia et al. 1593), and the publication in 1640 of Diego Aduarte’s Historia de la Provincia del Sancto Rosario de la Orden de Predicadores en Philippinas, Iapon, y China (History of the Province of the Holy Rosary of the Order of Preachers in the Philippines, Japan, and China), which Retana regarded as “[e]l volumen más considerable y mejos hecho, tipográficamente hablando, publicado en Filipinas en el siglo XVII” (the most considerable and best work, typographically speaking, published in the Philippines during the seventeenth century) (Retana 1911, 129). Retana also believed that the printer Tomas Pinpin, whom he dubbed “el principe de los tipográficos filipinas” (the prince of Filipino typographers), must have retired for good or died in 1640 (Retana 1911, 60).

A more recent work is especially important in the study of the survival of Philippine books: Regalado Trota Jose’s Impreso: Philippine Imprints 1593–1811 (1993). It comprises an exhaustive list of early books printed in the Philippines, with each entry displaying not only thorough bibliographical information but also the location of its extant or known copies. Although the data it offers on the surviving incunabula is in need of updating, Jose’s Impreso remains an indispensable and indeed impressive resource for the study of the survival of early Philippine imprints.

While now is as good a time as any to pay dedicated attention to the survival of Philippine books—given their ephemeral nature and the neglect in studying their destruction, preservation, or collection—it is a particularly opportune moment to do so because the history of the book is at a turning point. Rapid technological developments in the book industry (digital publishing) as well as in scholarship (digital humanities) are changing the way books are perceived and used, and altering the value original physical books are afforded in terms of not only their cultural and historical significance but also their monetary worth. In the case of rare old books, these issues are perhaps all the more pronounced. It seems imperative, thus, to take stock of such volumes at present to better serve their future survival, whether in physical or electronic form, and to foster further scholarship on the books themselves, on their texts and contexts. And it seems but natural to begin this task with the incunabula, the rarest and oldest books of the Philippines.

As far as can be ascertained, based on Jose’s listing in Impreso, 101 books were published in the Philippines from 1593 to 1640: 89 in Manila, three in Pampanga, three in Bataan (one being probable), one in Laguna, one likely in Batangas, and four in unknown locations (possibly Manila or other cities in central or southern Luzon) (Jose 1993, 21–51). The printing of these books was done by Chinese and Filipino craftsmen, under the supervision of Spanish friars, using locally made and imported equipment and materials. The texts were written in Spanish, Tagalog, Visayan, Hiligaynon, Iloko, Kapampangan, Chinese, Japanese, and Latin. They were on Christian catechism, doctrine, rituals, and prayers; grammars and vocabularies of various languages; rules and regulations of the religious orders; lives of the saints; accounts of contemporary Catholic martyrs; homilies; letters; historical writings; and government edicts.

Of the 101 books, 54 titles have extant or known copies while 47 have none. Copies of the extant books are located in various libraries around Asia, Europe, and North America—with eight titles held only in the Philippines, 15 in the Philippines and elsewhere, and 31 elsewhere. “Elsewhere” includes Austria, England, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Japan, the United States, and Mexico. Among the surviving Philippine incunabula, the Vocabulario de Iapon is quite extraordinary for having a large number of extant copies, with 15 confirmed and possibly one or more held in libraries in the Philippines, Japan, England, Italy, France, Spain, and the United States.

It is impossible to say with any certainty what made the Vocabulario de Iapon one of the best survivors among Philippine incunabula, and what made those 47 titles with no extant copies the worst, for there are many forces and variables that come into play in the survival of books in general, not discounting sheer luck, and accounts and records on the early Philippine imprints are few, scattered, incomplete, or inaccessible. What can be said with certainty about the Vocabulario de Iapon, however, is that the route it took to its survival is no different from that of the other extant books. And just as the latter did in the course of their survival through the centuries, the Vocabulario de Iapon underwent a transformation from being a material object to a cultural artifact, gaining in the process a great and varied worth beyond its original function and materiality.

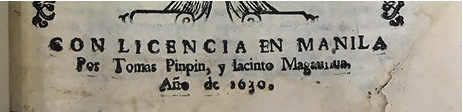

The Creation of a Material Object: Vocabulario de Iapon, Manila, Seventeenth Century

In 1630 three books were published in the Philippines, all in Manila: two by the press of the Dominicans and one by that of the Jesuits. Interestingly, both religious orders issued the same text by the same author, although with variations in spelling and pagination: Ritval para administrar los sanctos sacramentos sacado casi todo del ritual romano i lo demas del ritual indico (Ritual for administering the holy sacraments drawn almost entirely from Roman ritual and the rest from Indian ritual) by the Augustinian priest Alonso de Mentrida (Mentrida 1630; Jose 1993, 40–41).3) In effect, while there were three books that appeared that year, they were of only two titles. The other title published by the Dominicans was the Vocabulario de Iapon, which was printed by Tomas Pinpin and Jacinto Magarulau (see Fig. 1). The book was produced in quarto (4º) format, measuring around 28 × 22 cm, with 619 leaves or 1,238 pages. It was printed on what was then called “China paper,” due to where it was imported from, or “rice paper,” since it was thought to have been made from that grain though was actually made from paper mulberry (Pardo de Tavera 1893, 9).

Fig. 1 Title Page of the Vocabulario de Iapon, Printed in Manila in 1630. From the copy in the Bernardo Mendel Collection of the Lilly Library, Indiana University (photograph by author)

The Vocabulario de Iapon was a translation of the Portuguese Vocabulario da lingoa de Iapam (Vocabulary of the Japanese language) and its supplement, which were compiled by Jesuit missionaries and published by their press in Nagasaki—the Vocabulario da lingoa de Iapam in 1603 and the supplement in 1604 (Cooper 1976, 418).4) Hefty as the Vocabulario de Iapon may seem, it was actually an abridged combination of the original Portuguese books and, according to the Jesuit bibliographer Johannes Laures, “omitted a good many words” (Sophia University 2004). It was a remarkable effort nonetheless and stands as the first Japanese-Spanish dictionary ever produced. Although he is not identified in the book itself, the Dominican missionary Esquivel is credited with the translation of the work in Aduarte’s Historia de la Provincia del Sancto Rosario (Aduarte 1640, vol. 2, 302). Aduarte was also a missionary of the same order and personally knew Esquivel.

Esquivel, who was born in Vitoria, Spain, in 1593, joined the Dominican order in 1611 and set out for Manila as a missionary in 1625, arriving in 1626 or 1627 (Aduarte 1640, vol. 2, 301–302; Borao 2001, 130).5) In Manila, he studied theology at the Colegio de Santo Tomas while learning Japanese under the tutelage of Fr. Jacobo de Santa Maria (born Kyusei Gorobioye Tomonaga, now St. James of St. Mary), who helped him translate the Portuguese dictionary (Aduarte 1640, vol. 2, 302; Medina 1896, 29; Christian 2006, 67). Esquivel also produced two more works of Spanish translation from another language—the Doctrina Christiana e la lengua de los indios Tanchui, en la Isla Hermosa (Christian doctrine in the language of the natives of Tamsui on Hermosa Island) and the Vocabulario de la lengua de los indios Tanchui, en la Isla Hermosa (Vocabulary of the language of the natives of Tamsui on Hermosa Island)—both dated 1630 in manuscript form and neither of which saw print (Medina 1896, 29; Jose 1993, 40).6) He eventually left Manila for Isla Hermosa (Formosa, now Taiwan) and arrived there in 1631, settling in the province of Tamsui to preach the Catholic faith and pursue the missionary work of the Dominicans (Borao 2001, 122). But Esquivel’s intended destination was actually Japan, thus his formidable effort in producing the Vocabulario de Iapon, and Isla Hermosa served only as a stopover for him, as it did for other missionaries seeking to preserve and propagate Christianity in Japan (Aduarte 1640, vol. 2, 300–302; Borao 2001, 122).7) Esquivel was finally able to embark on that journey in 1633, leaving Isla Hermosa on a Chinese boat along with a Franciscan friar. The priests never reached Japan, for they were murdered at sea a few days into the trip (Aduarte 1640, vol. 2, 311; Medina 1896, 29).

Esquivel lived during a time that was perhaps like no other for Spanish missionaries, amidst the Spanish Crown’s expansion of its colonial empire and the Catholic Church’s heightened endeavor in proselytization as part of the Counter-Reformation movement. Both these efforts were pursued with great zeal particularly in Asia. For Catholic missionaries, the ultimate destinations for conversion were Japan and China—due in no small measure to the possibility of being martyred, as the rulers of the kingdoms had become inhospitable or hostile to Christianity and eventually became intolerant of it.

Japan had its first contact with the Catholic faith in 1549 with the arrival of the Jesuit St. Francis Xavier and his party of two other Jesuit priests, three Japanese Christian converts, and two manservants (Boxer 1967, 36). Xavier was successful in his mission of sowing the seeds of Christianity in Japan, and by the time of his departure in 1551 he had “left behind him a promising Christian community of a thousand souls” (Boxer 1967, 39). However, the gains in proselytization made by Xavier and the Jesuits who followed him were jeopardized when, in 1587, the ruler of the kingdom—Toyotomi Hideyoshi—issued an edict banishing missionaries from Japan for reasons seemingly more political than religious.8) However, this did not deter the Catholic Church from its goal of spreading the faith, with Dominican priests entering the land in 1592, followed by Franciscans in 1593 (Osswald 2021, 929). The peril of this venture was perhaps made most evident by the crucifixion of six Franciscan missionaries and twenty Japanese Christians (now known as “The Twenty-Six Martyrs”) in Nagasaki on February 5, 1597. More persecutions and executions followed in the succeeding years. In 1614 the shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu issued an edict banning Catholicism altogether, which forced missionaries and their followers to conduct their religious activities surreptitiously. It is estimated that up to five thousand or six thousand of them were martyred during the period 1614–40 (Boxer 1967, 360–361).

In China Christianity was introduced much earlier, possibly in the seventh century, although it would not be until the thirteenth century that missionary priests came to proselytize in the kingdom and only in the seventeenth century that a permanent mission was established in Peking (Beijing) by the Jesuit Matteo Ricci in 1602 (Cordier 1908). Throughout this early history of the Catholic Church in China, missionaries faced persecution in one form or another—from arrest to assassination, from proscription to expulsion. The Dominican St. Francis Fernández de Capillas, who was beheaded in the province of Fukien in 1648, is considered the “protomartyr of China” (Christian 2006, 141).

Many accounts of the persecution of European missionaries in Japan and China were produced during the seventeenth century, several of them printed in Manila, and these circulated in the European colonies as well as in Europe itself. In spite of the gruesome details they related—or perhaps precisely because of them—the stories served to quicken rather than quell the desire of other missionaries to be sent by their religious orders to these Asian kingdoms, as this offered opportunities for martyrdom. For missionaries, who were just as interested in their own salvation as that of others, “a martyr’s death was widely considered exemplary” (Clossey 2006, 49). The news of Fernández de Capillas’s martyrdom, for instance, “proved an incentive and more men than ever offered for service in China” (Latourette 1929, 110). Many others had been aspiring to go to Japan specifically to seek martyrdom ever since the Christian persecutions began in 1597.9) With a colonial government well in place and a large portion of the local population Christianized, the Philippines served as an ideal “base for missionary activity in China and Japan” (Latourette 1929, 89). Missionaries who came from Spain and Mexico did not go directly to these destinations “but first went to the Philippines to acclimatize themselves and to gather experience,” as in the case of Esquivel, who stayed in Manila for four years (Borao 2001, 109).

In light of the missionary zeal in Asia during the early seventeenth century, it is plain to see how vital were the works on local languages, from dictionaries and grammars to translations of Christian doctrines and rituals. Esquivel’s Vocabulario de Iapon, which Aduarte describes as a grand book produced with immense determination and effort (“libro grande, con inmenso teson, y trabajo”), was one among many such works created to aid the missionaries in their proselytization (Aduarte 1640, vol. 2, 302). It was also produced, as were the others, in accordance with the law issued by the Spanish monarch Philip III in 1619 ordering all missionaries to “know the language of the Indians” (quoted in Wasserman-Soler 2016, 690).10) Prior to the issuance of this law, however, missionaries in the Philippines had already been learning the local languages and producing works in them, which were meant primarily for their fellow priests and not their native converts, such as the Doctrina Christiana of 1593, which is one of the two earliest books printed in the Philippines. It featured the Tagalog syllabary and the basic Catholic doctrines translated into Tagalog and printed in the Roman alphabet as well as in the indigenous script Baybayin. Among the other works on local languages issued before 1619 were Arte y reglas de la lengva tagala (Art and rules of the Tagalog language) by Francisco Blancas de San José, printed in 1610; Arte de lengua Pampanga (Art of the Pampanga language) by Francisco Coronel, 1617; and Arte de lengua bisaya hiligayna de la isla de Panay . . . (Art of the Visayan Hiligaynon language of Panay Island . . .) by Alonso de Mentrida, 1618.

Missionaries in the Philippines did not limit their linguistic undertakings to the local vernaculars. The other earliest book, also printed in 1593, was in Chinese: Hsin-k’o seng-shih Kao-mu Hsien chaun Wu-chi t’ien-chu cheng-chiao chen-chuan shih-lu (A printed edition of the veritable record of the authentic tradition of the true faith in the infinite God, by the religious master Kao-mu Hsien), written by the Dominican Juan Cobo (Kao-mu Hsien). The Shih-lu, as the book is referred to by scholars, contained discussions on theology and Western concepts of cosmography and natural history (Van der Loon 1966, 2). Cobo expressly intended the book for Chinese converts to Christianity, but its high language and expensive price did not align with this aim, as noted by Lucille Chia (2011). The Shih-lu was written in classical Chinese, which few Chinese in the Philippines would have understood—“not only because they lacked the necessary education, but also because nearly all of them spoke exclusively Minnanese [Hokkien]” (Chia 2011, 262). As for Cobo’s fellow missionaries who could have read and learned from the book, Chia supposes that “they would also have been primarily concerned with mastering spoken Minnanese to minister to their parishioners” (Chia 2011, 262). While not discounting Cobo’s purpose in publishing the work, she suggests that the Shih-lu could have been written also “to show what the Dominicans were capable of in their task of converting the Chinese” (Chia 2011, 262).

Other books in Chinese came in the wake of the publication of the Shih-lu, appearing even before works in the vernacular languages: the Doctrina Christiana en letra y lengua china (Christian doctrine in Chinese letters and language) by Miguel de Benavides et al., printed c. 1605; Memorial de la vida christiana en lengua china (Memoir of the Christian life in Chinese) by Domingo de Nieva, 1606; and Simbolo de la fe, en lengua y letra china (Symbol of the faith, in the Chinese language and letters) by Tomas Mayor, 1607. Unlike the Shih-lu, these publications seemed to have been more suited to local Chinese communities. The text of the Chinese Doctrina Christiana, for example, “was clearly composed for Minnanese readers and listeners,” according to Chia (2011, 265). The likely audience of these books, then, were missionaries in Manila and elsewhere in the Philippines as well as their Chinese converts. It is not unlikely, though, that the books were also put to use by missionaries headed for or already in China.

Missionaries in the Philippines also produced books in Japanese, with five titles issued during the incunabula period.11) All the volumes were printed in roman letters (Romaji), which may have had to do with the capacity of the local presses—or their limitations, being unequipped with types in Japanese script (kanji) or with no craftsmen to create woodblocks for xylographic printing. Esquivel’s Vocabulario de Iapon was the last among the books in Japanese to see print. It was the only book on language, the others being on religious matters, and its text was the longest among them. Given that it was produced entirely in roman letters and that the Japanese community in the Philippines at the time was not as large or widespread as that of the Chinese, it seems evident that the Vocabulario de Iapon was published primarily for missionaries who were going or aspired to go to Japan, as Esquivel himself did. Since the production of the book was quite a massive undertaking, it could have also served as a showpiece for the Dominicans, as the Shih-lu might have done. This seems plausible in light of the rivalry between the mendicant orders—the Dominicans, Franciscans, and Augustinians—and the Jesuits over “the right to evangelise Japan” (Tronu 2015, 25).

Outside of the remarks by Aduarte on the authorship of the Vocabulario de Iapon, there appear to be no other records on the book, no available data on its print run, distribution, and reception in its time. What is known, though, is that its publisher, the Colegio de Santo Thomas, did not issue any edition other than the first. After its initial circulation, Esquivel’s book lay dormant for centuries.

Transformation into a Cultural Artifact: Vocabulario de Iapon, Nineteenth to Twenty-first Century

There are three stages in the survival of a book, according to Adams and Barker: its creation and initial reception, when “it is used to perform the function for which it was brought into existence”; its resting period, when “it comes to rest without any use or at least intensive use”; and its entrance into the world of collecting and scholarly research, “when it is discovered that it is . . . desirable as an object, either in its own right or because of the text it contains” (Adams and Barker 2001, 32). It is in the third stage of its survival that the book transforms from a material object to a cultural artifact.

Susan M. Pearce describes “artifact,” which means “made by art or skill,” as a term that

takes a narrow view of what constitutes material objects, concentrating upon that part of their nature which involves the application of human technology to the natural world, a process which plays a part in the creation of many, but by no means all, material pieces. (Pearce 1994, 10–11)

Artifacts, as Henry Pratt Fairchild asserts, “embody and concretize various cultural values and achievements” (Berger 2009, 17). It might be said of the surviving book, then, that in transcending its original function and its materiality, or in its transformation from material object to cultural artifact, it gains a worth founded not only on its craftsmanship, which is a manifestation of the artistry and technology of its time, but also on its symbolic meaning to its owners or users during the periods when it is found to be desirable. This significance bears intellectual influences; political, legal, and religious influences; commercial pressures; and social behavior and taste—or, in Adams and Barker’s model, “the whole socio-economic conjuncture” (Adams and Barker 2001, 14). Thus, it is not static: it adapts to and changes with the times.

Esquivel’s Vocabulario de Iapon entered the third stage of its survival in the nineteenth century, becoming a collectible in the antiquarian market for its age, rarity, and possibly exoticism or “orientalism,” and a scholarly source or historical text in the academe for its prototypical nature. In 1835, a copy bound in vellum was put up for sale by the bookseller Ch. Citerne in Ghent as part of the library of the famed English book collector Richard Heber, listed as item number 705 in the Catalogue d’une belle collection de livres et manuscrits ayant fait partie de la bibliothèque de feu M.R.H. . . . (Catalog of a fine collection of books and manuscripts that were part of the library of the late M.R.H. . . .) (Ch. Citerne 1835, 49).12) In 1868, the Dictionnaire japonais-français . . . traduit du dictionnaire japonais-portugais composé par les missionnaires de la Compagnie de Jésus et imprimé en 1603, à Nagasaki . . . et revu sur la traduction espagnole du même ouvrage rédigée par un père dominicain et imprimée en 1630, à Manille . . . publié par Léon Pagès [Texte imprimé] (Japanese-French dictionary . . . translated from the Japanese-Portuguese dictionary composed by the missionaries of the Society of Jesus and printed in 1603, in Nagasaki . . . and reviewed from the Spanish translation of the same work written by a Dominican father and printed in 1630, in Manila . . . published by Léon Pagès [printed text]) by the French diplomat Léon Pagès was published in Paris. Laures notes that this translation was based on the Bibliothèque nationale de France’s incomplete copy of the Vocabulario da lingoa de Iapam supplemented by its complete copy of the Vocabulario de Iapon (Sophia University 2004). In 1887 a copy of Esquivel’s dictionary was offered for sale at £30 by the London bookseller Bernard Quaritch, listed as item number 35211 in his Catalogue of Works in the Oriental Languages Together with Polynesian and African and described as a “4to. printed on native paper, a few letters wanting on the first two leaves, and the last two leaves slightly defective, otherwise good copy in vellum, from the Sunderland library” (Quaritch 1887, 3410). Its list price converts to around £2,400 today (National Archives n.d.). According to Laures, “Upon inquiry from Quaritch to whom it had been sold we were told that this was not known” (Sophia University 2004).

The trail of the Vocabulario de Iapon went cold again for several years until some traces of its copies emerged during World War II. As Laures states, “The copy of Professor C. R. Boxer was stolen from his valuable collection [in London] during the war, that of the Franciscan Convent and probably also that of the Philippines Library, Manila, perished as a result of the war” (Sophia University 2004). In 1972 the book saw a resurrection in the form of a facsimile reproduction published by the Tenri Central Library under its Classica Japonica Facsimile Series (Esquivel 1972). This reproduction was itself reissued in 1978 as part of the Tenri Central Library Reprint Series.

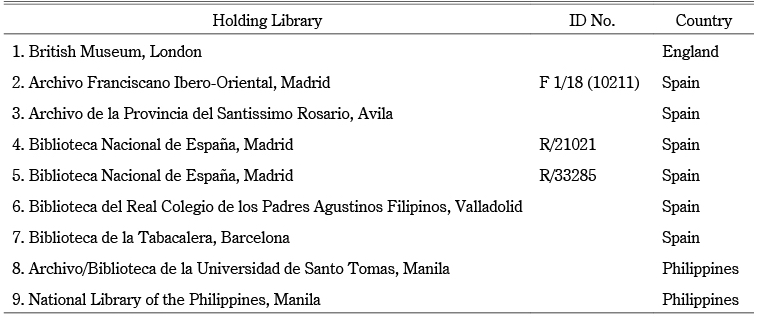

In 1993, according to Jose in Impreso, there were nine known copies of the Vocabulario de Iapon. Although Jose does not specify which of these were actually extant, he identifies the libraries where the copies “may, or used to, be found” (Jose 1993, 13), as outlined in Table 1.

Since Jose’s listing, more copies of the book have surfaced in institutional libraries. The digitization of the catalogs of these libraries and their accessibility online have made it possible to create a more accurate and fuller sketch of the survival of the Vocabulario de Iapon into the twenty-first century, nearly four hundred years after it was first printed. Today, there are 15 verified extant copies of the book and one unverified due to accessibility issues with the catalog of the holding institution13) (see Table 2). There is also a microform copy of the book held in the Biblioteca Nacional de España in Madrid. The copies of the Biblioteca Histórica Marqués de Valdecilla of the Universidad Complutense de Madrid and the Bibliothèque nationale de France have been digitally photographed and are accessible online.

Table 2 Known Extant Copies of the Vocabulario de Iapon, 2022

| Holding Library | ID No. | Country |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Bodleian Library, University of Oxford | 014322948 | England |

| 2. Bodleian Library, University of Oxford | 014705866 | England |

| 3. British Library, London | 001853658 | England |

| 4. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris | 3123111 | France |

| 5. Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale de Roma | 69.1.F37 | Italy |

| 6. Kirishitan Bunko Library, Sophia University, Tokyo | KB211:31 | Japan |

| 7. Biblioteca Estudio Teológico Agustiniano de Valladolid | I-125 | Spain |

| 8. Biblioteca Histórica Marqués de Valdecilla, Universidad Complutense de Madrid | BH FG 2997 | Spain |

| 9. Biblioteca Nacional de España, Madrid | R/14687 | Spain |

| 10. Biblioteca Nacional de España, Madrid | R/21021 | Spain |

| 11. Biblioteca Nacional de España, Madrid | R/33285 | Spain |

| 12. Real Biblioteca, Madrid | 38401 | Spain |

| 13. National Library of the Philippines, Manila | R0007 I4 | Philippines |

| 14. Lilly Library, Indiana University | PL681.E82 | USA |

| 15. Copy sold at auction in 2016, PBA Galleries, San Francisco | USA |

B. Unverified

| Holding Library | ID No. | Country |

|---|---|---|

| Cited in Impreso (Jose 1993, 41): 16. Archivo Franciscano Ibero-Oriental, Madrid |

F 1/18 (10211) | Spain |

Sources: Author’s research; Jose (1993, 41).

Of the 15 verified copies of the Vocabulario de Iapon on the 2022 list, only five appeared in the account by Jose (1993): those of the British Museum (now the British Library), Biblioteca de Real Colegio de los Padres Agustinos (now Biblioteca Estudio Teológico Agustiniano de Valladolid), Biblioteca Nacional de España (two copies), and National Library of the Philippines. However, this does not necessarily indicate that the ten copies that have since emerged were all acquired by their institutions during the 1993–2022 period, for there were copies that, understandably, Jose missed in his listing. As far as can be determined, these copies are those of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, which was already in its collection in the 1860s; the Kirishitan Bunko Library of Sophia University in Tokyo, which was in its ownership in the 1940s; the Lilly Library of Indiana University, which was acquired in the 1960s; and, as noted in Laures’s bibliography produced in the 1940s, the Bodleian Library (one copy) and the Real Biblioteca (known previously as the Biblioteca del Palacio del Rey).14) It may well be assumed that the copies of the remaining institutions on the 2022 list were indeed acquired within the last 29 years. This is certain, for instance, in the case of the copy of the Biblioteca Histórica Marqués de Valdecilla, which was obtained in 2006 from the physician-bibliophile Francisco Guerra, who donated his library to the university (Universidad Complutense de Madrid n.d.).

That copies of the Vocabulario de Iapon are held in national and university libraries in seven nations and three continents attests to the cultural and historical value that the book has gained through the years, a worth that has been recognized outside of the countries it was originally relevant to—the Philippines, Japan, and Spain. A recent development serves as further testimony of the book’s value, both symbolic and monetary: in 2016 PBA Galleries in San Francisco put up for auction a copy that it described as “exceedingly rare” and, based on a note on the front endpaper, “purchased in Manila in 1933 from the Librarian of the Philippine National Library, initialed C.R.B.” (PBA Galleries 2016).15) No doubt this was Boxer’s copy that was stolen during the war, for the copy’s title page bears his Chinese seal. PBA Galleries did not provide information on the owner of the copy (perhaps the person who stole it from Boxer) nor the buyer at the auction. The market value of the book was estimated at $4,000–$6,000; it sold for $15,600.

Each of the extant copies of the Vocabulario de Iapon bears its own character and value due to its provenance and condition, making it distinct from the others. The copy in the Lilly Library is especially interesting because of its appearance, from which can be drawn distinct insights on the artifactual nature of rare old books and on the survival of Philippine incunabula.

The Bernardo Mendel Collection Copy in the Lilly Library

The copy of the Vocabulario de Iapon in the Lilly Library at Indiana University was part of the private library of Bernardo Mendel. Born in Vienna in 1895, Mendel studied law, became a decorated soldier in World War I, and then went into business, exporting “elegant Austrian goods” mostly to South America (Byrd 1973, 6). In 1928 he moved to Colombia, where he pursued his business and other interests—the promotion of music and the collection of books, initially those related to Latin American history and then to the discovery of the New World, the Spanish conquests, and independence movements in South America (Byrd 1973, 7–8). In 1952, having retired from his business in Bogotá, he bought the antiquarian book firm of Lathrop C. Harper in New York and moved to that city shortly after (Byrd 1973, 9). He “continued to add to his private library of Latin Americana, which he kept completely apart from the Harper business” (Lilly Library 1970, 4). Mendel sold his entire library to Indiana University in 1961 and “dedicated the remainder of his life to augmenting and increasing the scope of his original collection” at the university (Byrd 1973, 10). By the time of Mendel’s death in 1967, his library of 2,200 titles had come to be supplemented by “more than 20,000 titles, approximately 70,000 manuscripts, and 15,000 broadsides” from other private collections that the university acquired through his efforts (Byrd 1973, 14).

The Vocabulario de Iapon is one of the six titles of Philippine incunabula in the Bernardo Mendel Collection and the earliest book printed among them.16) It is in remarkably good condition. It bears no markings or stamps of previous owners and appears to have been hardly used or lightly so at most. Barring the foxing and the small tears on some of its pages, which are not unusual for a book of its age—especially given the material it was made out of—it is a clean, complete, and intact copy. This is in stark contrast with the conditions of other surviving copies, such as all three volumes in the Biblioteca Nacional de España, which are deteriorated, with two (R/s14687 and R/21021) withdrawn from room use (Biblioteca Nacional de España n.d.); that in the National Library of the Philippines, which is disfigured by insect holes, tears on many pages, several ownership stamps on its title page, and its amateur repair; or the copy auctioned by PBA Galleries, which is described as “Extensively repaired with 8 leaves provided in facsimile and numerous other leaves silked on both sides or with other repairs to tears, chips, and worming, [with] some loss to text” (PBA Galleries 2016).

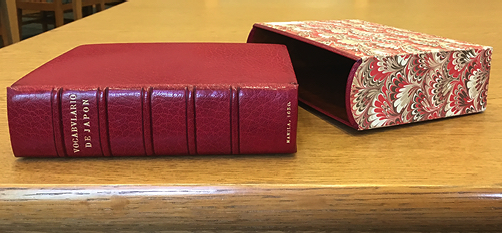

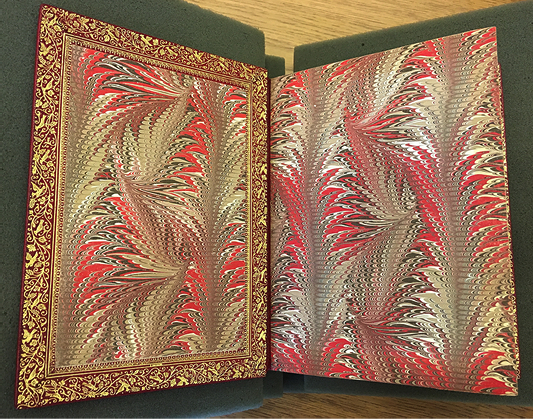

What is particularly striking about the condition of the Mendel copy, however, is its binding, even if—or perhaps precisely because—it is not the original one (see Fig. 2). The binding of the book is made of red morocco leather with false bands, with the short title and the place and date of publication in gold tooling on the spine. The inside covers are also tooled, with gold dentelles, and the endpapers marbled (see Fig. 3). The binding is complemented by a slipcase covered in marbled paper. It is, altogether, an exemplar of fine design and quality craftsmanship. The person behind such work, as indicated by his mark on the inside front cover, is the Spanish bookbinder Antolín Palomino (1909–95). Renowned for his absolute technical perfection (“absoluta perfección técnica”), Palomino ran a bindery in Madrid that was active from 1942 to 1982 (Lafuente 1995). He counted Mendel among his many clients and also as his friend (Palomino 1987, 41).

Fig. 2 Binding of Mendel Copy of the Vocabulario de Iapon, with Slipcase (photograph by author)

Fig. 3 Inside Front Cover of the Mendel Copy of the Vocabulario de Iapon (photograph by author)

It is important to note that the Mendel copy of the Vocabulario de Iapon was not just preserved but was actually restored: its repair involved the replacement of some of its original elements, its binding in particular. Restoration usually diminishes the historical and monetary value of an item in the antiquarian market, which puts a premium on the object’s condition being as close as possible to its original state. However, it is more likely than not for very old books, such as those from the seventeenth century, to have undergone some form of repair in the course of their survival. As far as restored items are concerned, rare book dealers and collectors generally hold to the principle that the older the repair of the book, the better it is for its value. In the case of the Mendel copy of the Vocabulario de Iapon, then, its twentieth-century rebinding might be considered a negative in terms of the volume’s historical authenticity and monetary worth. But on the other hand, it may well be regarded as an element that adds to the book’s aesthetic value and physical soundness, which may offset some of the devaluation from restoration.

The Mendel copy’s original binding probably would have been in plain vellum, which was the common material for book coverings in the seventeenth century. This would not have made the copy visually striking. Furthermore, despite the minimal usage of the book, as suggested by the condition of its pages, this binding would have displayed signs of the inevitable wear and tear for a book of its age: discoloration from oxidation, stains from dust and other elements, cracking, rubbing, loose joints and hinges, or all of the above. The work done on the book by Palomino involved removing the original binding, and with it all the marks of use and aging, then replacing it with a covering that was by no means ordinary or merely functional. Handsomely designed and created, the rebinding of the Mendel copy enhances the visual art element of the book. That it was produced by an esteemed craftsman gives this aspect a brand-name value, which consequently provides the book itself with a unique worth.

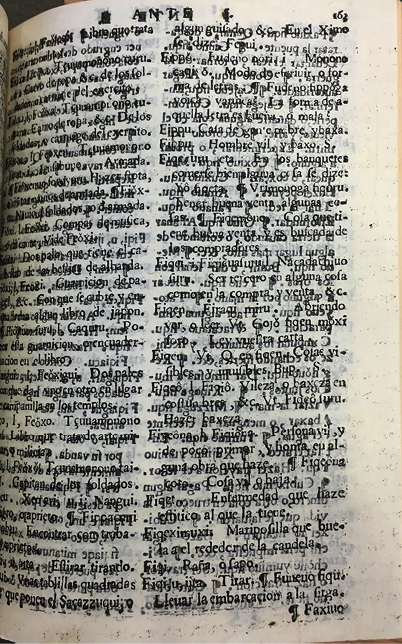

The binding of the Mendel copy of the Vocabulario de Iapon is elegant indeed, so much so that it seems ill matched with the pages it holds together and protects, pages whose printing was not of the highest caliber. Immediately telling of this is the typographical error in the last name of the printer Jacinto Magarulau, which appears to have been spelled as “Magaurlua” using some worn types and displaying uneven pressing (see Fig. 4). One might even describe the printing of the entire book as downright shoddy given the paper used, the kind that the historian-bibliographer Trinidad Pardo de Tavera described as detestable, brittle, without consistency or resistance (“detestable, quebradizo, sin resistencia ni consistencia”) (Pardo de Tavera 1893, 9). The paper of the book has varying textures and gradations. More significantly, it is so thin that the text on the leaves with printed matter on both sides looks like it has bled onto the reverse side. The text appears nearly illegible (see Fig. 5).

Fig. 4 Detail of the Title Page of the Vocabulario de Iapon, Mendel Copy (photograph by author)

Fig. 5 A Page from the Vocabulario de Iapon Displaying the Quality of the Paper and the Printing of the Book (photograph by author)

Due to the unavailability or inaccessibility of records, it is not known when, from whom, and for how much Mendel acquired his copy of the Vocabulario de Iapon. It is also undetermined whether he bought the copy already rebound or had it rebound himself, although the latter is more likely given his connection to Palomino. It is certain, however, that the book in its present condition was part of the lot sold to the Lilly Library in 1961. The copy is stored in the vault of the library, where it is available for room use upon request. The Lilly Library would not say why the book is in special storage. Two other books of the six Philippine incunabula in the Bernardo Mendel Collection are also kept in the vault: Succesos felices, que por mar, y tierra ha dado N. S. a las armas españolas . . . (Happy successes, at sea and land, that were granted by Our Lady to the Spanish army . . .), which was printed anonymously in 1637; and Relacion de lo qve asta agora se a sabido de la vida y martyrio del milagroso padre Marcelo Francisco Mastrili de la Compañia de Iesus . . . (Account of what until now has been known about the life and martyrdom of the miraculous Father Marcelo Francisco Mastrili of the Society of Jesus . . .) by Geronimo Perez, printed in 1639. What these books seem to have in common with the Vocabulario de Iapon—unlike the remaining three incunabula, which are kept in the stacks—is that their rebinding includes extra features: a folding case for the Succesos and a book box for the Relacion. More significant, perhaps, is that all three books were printed by the “prince of Filipino typographers,” Tomas Pinpin.

The Mendel copy of the Vocabulario de Iapon tells no great stories about its ownership through the ages or its journey from seventeenth-century Manila to twentieth-century Bloomington, Indiana, where the Lilly Library is, for the book bears hardly any physical evidence of its provenance and the records on it are scant. But it does say something significant about its survival as a book as well as that of the other extant copies of the Vocabulario de Iapon. With its pages in good condition, notwithstanding its poor printing, and its binding so fine, the Mendel copy inevitably calls attention to its materiality and aesthetic as a book and to the circumstances and technology involved in its preservation and restoration, which in turn highlight the process of its becoming an artifact.

The Survival of the Vocabulario de Iapon and Other Philippine Incunabula

The Vocabulario de Iapon was a pioneering work in the history and study of the Japanese and Spanish languages, and even in the history of the Catholic Church and the Spanish colonial empire. In the course of its survival, however, it became less a dictionary produced by Christian missionaries than a very expensive, old, rare book; a prestige item for antiquarian book collectors; an object of colonial or orientalist interest; a resource on the history of the Japanese language; an example of seventeenth-century printing in Asia; or one of the 18 known books produced by the most famous printer in Philippine history. Besides being any or all of these now, the Mendel copy distinctly serves also as a manifestation of the craftsmanship of a renowned bookbinder of the twentieth century.

Not every extant Philippine incunabulum can evoke special interest in its physicality, but being among the earliest outputs of Philippine presses and having endured for centuries, each is like the Mendel copy of the Vocabulario de Iapon in undergoing a transformation from material object to artifact. Each has gained a cultural, historical, and monetary worth beyond its original function and materiality, although in different ways and in varying degrees. Furthermore, each can reveal something about other aspects of the survival of early Philippine imprints—be it on their reception, republication, or provenance.

Adams and Barker note, “The function of the book as text, as a vehicle carrying information within it, is obvious, but the information that it provides by virtue of its mere survival and the existence is not less important because less obvious” (Adams and Barker 2001, 37). The survival of the incunabula of the Philippines can offer much information not only on the publication, manufacture, distribution, and reception of early Philippine imprints—on which not enough is known—but also on Spanish colonial rule, particularly during the seventeenth century, which itself is an understudied period; Christian missions in Asia during the Counter-Reformation; global trade and travel since the early modern period; and Philippine historiography in general. As the survival of the book is “not merely a physical fact, but the degree to which that fact is known” (Adams and Barker 2001, 38), it is important to study how early Philippine imprints have withstood the circumstances and effects of time (or how some titles have not), where the extant copies are, and how and why they got there, for this would ensure their continued survival.

Accepted: March 31, 2023

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to the Mendel Fellowship from the Lilly Library of Indiana University and to the Visiting Research Scholar Fellowship from the Center for Southeast Asian Studies of Kyoto University for the support that made the research and writing of this article possible.

References

Adams, Thomas R. and Barker, Nicolas. 2001. A New Model for the Study of the Book. In A Potencie of Life: Books in Society, edited by Nicolas Barker, pp. 5–43. London: British Library; Delaware: Oak Knoll Press. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

Aduarte, Diego. 1640. Historia de la Provincia del Sancto Rosario de la Orden de Predicadores en Philippinas, Iapon, y China [History of the Province of the Holy Rosary of the Order of Preachers in the Philippines, Japan, and China]. Manila: Colegio de Sancto Tomas, por [printed by] Luis Beltran impressor de libros. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

―. 1631. Relacion de varias cosas y casos, qve han svcedido en los reynos de Iapon, que se han sabido en estas islas Philippinas por cartas de los padres de S. Domingo q esta alla . . . [Account of various things and cases, which have occurred in the kingdoms of Japan, which have been known in these Philippine Islands through letters from the fathers of S. Domingo who are there . . .]. Manila: Colegio de Sancto Thomas por [printed by] Jacinto Magarulau. ↩

Angeles, Juan de los. 1623. Virgen S. Mariano tattoq I Rosariono iardin tote fanazoni tatoyuru qio. Vanaiiqu Jesusno Cofradiano regimientono riaco [Garden of the Holy Rosary of the Blessed Virgin Mary or book similar to flowers. And a brief rule for the confraternity of Jesus]. Binondocno: Dominican Press. ↩

―. 1622. Virgen S. Mariano tattoqi rosario no xuguioto, vonajiqu Iesusno minano cofradiani ataru riacuno qirocu [A short list pertaining to the followers of the Holy Rosary of the Blessed Virgin Mary, and of the confraternities of the Holy Name of Jesus]. Binondocno: Dominican Press. ↩

Anonymous. 1637. Succesos felices, que por mar, y tierra ha dado N. S. a las armas españolas: en las Islas Filipinas contra el Mindanao; y en las de Terrenate, contra los holandeses, por fin del año de 1636. y principio del de 1637 [Happy successes, at sea and land, that were granted by Our Lady to the Spanish army in the Philippine Islands against Mindanao; and in the Terrenate, against the Dutch, at the end of the year 1636 and beginning of 1637]. Manila: [Imp. de los Jesuitas] por [printed by] Tomas Pimpin. ↩ ↩

Arce, Pedro de. 1632. Copia de una carta que embió el señor obispo de Zebú, gouernador del arçobispado de Manila de las islas Filipinas, al Rey nuestro señor [Copy of a letter sent by the bishop of Cebu, governor of the Archbishopric of Manila of the Philippine Islands, to the King Our Lord]. Manila: n.p. ↩

Author unidentified. 1623a. Lozonni voite aru fito svcaxono tevo voi yagate xixezu xite canauazarixi teitarito iyedomo, tattoqi Rosariono goqidocunite inochiuo nobetamo coto. Manila: n.p. ↩

―. 1623b. Vareraga voaruji Iesv Christo S. Brigida, S. Isabel, S. Mitildesni tçuguetamo vonmino go Passiono voncuruximino iroxinano coto . . . Binondoc: Thomas Pinpin (printer). ↩

Báez, Fernando. 2008. A Universal History of the Destruction of Books: From Ancient Sumer to Modern-Day Iraq. Translated by Alfred MacAdam. New York: Atlas. ↩

Basbanes, Nicholas A. 1995. A Gentle Madness: Bibliophiles, Bibliomanes, and the Eternal Passion for Books. New York: Henry Holt. ↩ ↩

Benavides, Miguel de, et al. c. 1605. Doctrina Christiana en letra y lengua china [Christian doctrine in Chinese letters and language]. Manila: Keng Yong [printer]. ↩ ↩

Berger, Arthur Asa. 2009. What Objects Mean: An Introduction to Material Culture. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press. ↩

Biblioteca Nacional de España. n.d. Vocabulario de Japon [Japanese vocabulary]. In Catálogo BNE. http://catalogo.bne.es/uhtbin/cgisirsi/?ps=FnCcFWpaTJ/BNMADRID/183171805/8/12606670/Vocabulario+de+Japon, accessed September 29, 2023. ↩

Blancas de San José, Francisco. 1610. Arte y reglas de la lengva tagala . . . [Art and rules of the Tagalog language]. Bataan: Thomas Pinpin (printer). ↩

Borao, José Eugenio. 2001. The Dominican Missionaries in Taiwan (1626–1642). In Missionary Approaches and Linguistics in Mainland China and Taiwan, edited by Ku Wei-ying, pp. 101–132. Leuven: Leuven University Press and Ferdinand Verbiest Foundation. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

Boxer, C. R. 1967. The Christian Century in Japan, 1549–1650. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

Brockey, Liam Matthew. 2017. Books of Martyrs: Example and Imitation in Europe and Japan, 1597–1650. Catholic Historical Review 103(2): vi, 207–223. https://doi.org/10.1353/cat.2017.0060. ↩

Byrd, Cecil K. 1973. Bernardo Mendel: Bookman Extraordinaire, 1895–1967. Bloomington: Lilly Library, Indiana University. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

Carter, John. 1994. ABC for Book Collectors. Seventh Edition. Revised by Nicolas Barker. London: Werner Shaw. ↩

Ch. Citerne. 1835. Catalogue d’une belle collection de livres et manuscrits ayant fait partie de la bibliothèque de feu M.R.H., suivi d’un supplément . . . [Catalog of a fine collection of books and manuscripts that were part of the library of the late M.R.H., followed by a supplement . . .]. Ghent: Imprimerie de D. Duvivier Fils. ↩

Chia, Lucille. 2011. Chinese Books and Printing in the Early Spanish Philippines. In Chinese Circulations: Capital, Commodities, and Networks in Southeast Asia, edited by Eric Tagliacozzo and Wen-chin Chang, pp. 259–282. Durham: Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822393573-012. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

Christian, George G., O.P., ed. 2006. Witnesses of the Faith in the Orient: Dominican Martyrs of Japan, China, and Vietnam. Second Edition. By a team of Dominican fathers under the direction of Ceferino Puebla Pedrosa, O.P. Translated by Maria Maez, O.P. Hong Kong: Provincial Secretariat of Missions, Dominican Province of Our Lady of the Rosary. ↩ ↩

Clarke, William. 2014. Richard Heber, Esq. In Repertorium bibliographicum: Or, Some Account of the Most Celebrated British Libraries, pp. 288–298. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107446076.040. ↩

Clossey, Luke. 2006. Merchants, Migrants, Missionaries, and Globalization in the Early-Modern Pacific. Journal of Global History 1(1): 41–58. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1740022806000039. ↩

Cobo, Juan 高母羨[Kao-mu Hsien]. 1593. Hsin-k’o seng-shih Kao-mu Hsien chuan Wu-chi t’ien-chu cheng-chiao chen-chuan shih-lu 新刻僧師高母羨撰無極天主正教真傳實錄[A printed edition of the veritable record of the authentic tradition of the true faith in the infinite God, by the religious master Kao-mu Hsien]. Manila: Dominican Press. ↩ ↩

Cooper, Michael. 1976. The Nippo Jisho. Monumenta Nipponica 31(4): 417–430. https://doi.org/10.2307/2384310. ↩ ↩

Cordier, Henri. 1908. The Church in China. The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton. New Advent. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03669a.htm, accessed March 6, 2018. ↩

Coronel, Francisco. 1617. Arte de lengua Pampanga [Art of the Pampanga language]. Manila?: n.p. ↩

Esquivel, Jacinto, trans. 1978. Vocabulario de Iapon declarado primero en portvgves por los padres de la Compañia de Iesus de aquel reyno, y agora en castellano en el Colegio de Santo Thomas de Manila [Japanese vocabulary declared initially in Portuguese by the fathers of the Society of Jesus of that kingdom, and now in Castilian in the Colegio de Santo Thomas of Manila]. Tenri Toshokan hon fukusei, dai 54-go 天理図書館本複製, 第54号(Tenri Central Library reprint, no. 54). Tokyo: Yushodo Shoten.

―, trans. 1972. Vocabulario de Iapon declarado primero en portvgves por los padres de la Compañia de Iesus de aquel reyno, y agora en castellano en el Colegio de Santo Thomas de Manila [Japanese vocabulary declared initially in Portuguese by the fathers of the Society of Jesus of that kingdom, and now in Castilian in the Colegio de Santo Thomas of Manila]. Tenri Toshokan zempon sosho: Yosho no bu, dai 1-ji kanko gogaku hen 天理図書館善本叢書: 洋書之部, 第1次刊行語学篇[Classica Japonica Facsimile Series in the Tenri Central Library, Vol. 1: Linguistics]. Tokyo: Tenri Central Library. ↩

―. 1630a. Doctrina Christiana e la lengua de los indios Tanchui, en la Isla Hermosa [Christian doctrine in the language of the natives of Tamsui on Hermosa Island]. Manila: Unpublished. ↩

―, trans. 1630b. Vocabulario de Iapon declarado primero en portvgves por los padres de la Compañia de Iesus de aquel reyno, y agora en castellano en el Colegio de Santo Thomas de Manila [Japanese vocabulary declared initially in Portuguese by the fathers of the Society of Jesus of that kingdom, and now in Castilian in the Colegio de Santo Thomas of Manila]. Manila: [Colegio de Santo Thomas] por [printed by] Tomas Pinpin and Iacinto Magarulau. ↩

―. 1630c. Vocabulario de la lengua de los indios Tanchui, en la Isla Hermosa [Vocabulary of the language of the natives of Tamsui on Hermosa Island]. Manila: Unpublished. ↩

―. 1630d. Ritval, para administrar los santos sacramentos sacado casi todo del ritual romano i lo demas del ritual indico. Con algunas advertencias necessarias para la administracion de los santos sacramentos. Con vna declaracion sumaria de lo que las religiones mendicantes pueden en las Indias por privilegios apostolicos, los quales se train a la letra . . . [Ritual, for administering the holy sacraments drawn almost entirely from Roman ritual and the rest from Indian ritual. With some necessary warnings for the administration of the holy sacraments. With a summary declaration of what the mendicant religious can do in the Indies for apostolic privileges, which are brought to the letter . . .]. Manila: Imprenta de la Compañia de Jesus por [printed by] Simon Pinpin. ↩

Gayo Aragón, J. 1954. Ordinationes Generales: Incunable Filipino de 1604. Facsimile del ejemplar existente en la Biblioteca del Congreso, Washington, con un ensayo histórico-bibliográfico por Fr. J. Gayo Aragón, O.P. [Ordinationes Generales: Philippine incunabule of 1604. Facsimile of the extant copy in the Library of Congress, Washington, with a historical-bibliographical essay by Fr. J. Gayo Aragón, O.P.]. Manila: University of Santo Tomas. ↩ ↩

Gayo Aragón, J. and Domínguez, Antonio. 1951. Doctrina Christiana: Primer libro impreso en Filipinas. Facsímile del ejemplar existente en la Biblioteca Vaticana, con un ensayo histórico-bibliográfico por Fr. J. Gayo Aragón, O.P., y observaciones filológicas y traducción española de Fr. Antonio Domínguez, O.P. [Doctrina Christiana: the first book printed in the Philippines. Facsimile of the extant copy in the Vatican Library, with a historical-bibliographical essay by Fr. J. Gayo Aragón, O.P., and philological observations and Spanish translation by Fr. Antonio Domínguez, O.P.]. Manila: Imprenta de la Real y Pontificia Universidad de Santo Tomás de Manila. ↩

Grimsted, Patricia Kennedy. 2004. The Road to Minsk for Western “Trophy” Books: Twice Plundered but Not Yet “Home from the War.” Libraries & Culture 39(4): 351–404. http://doi.org/10.1353/lac.2004.0075. ↩

Hobson, Anthony. 2012. Renaissance Book Collecting: Jean Grolier and Diego Hurtado de Mendoza, Their Books and Bindings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ↩

Jesuit Missionaries. 1603. Vocabulario da lingoa de Iapam, com adeclaração em portugues, seito por alguns padres e irmaõs da Companhia de Iesu [Vocabulary of the Japanese language, with the declaration in Portuguese, used by some priests and brothers of the Society of Jesus]. Nangasaqui: Collegio da Japam de Companhia de Iesus. ↩

Jose, Regalado Trota. 1993. Impreso: Philippine Imprints 1593–1811. Makati: Fundación Santiago and Ayala Foundation. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

Knuth, Rebecca. 2006. Burning Books and Leveling Libraries: Extremist Violence and Cultural Destruction. Westport: Praeger. ↩

Lafuente, Carlota. 1995. Necrológicas: Antolín Palomino, encuadernador [Obituaries: Antolín Palomino, bookbinder]. El País. July 28. https://elpais.com/diario/1995/07/28/agenda/806882402_850215.html, accessed June 7, 2016. ↩

Latourette, Kenneth Scott. 1929. A History of Christian Missions in China. New York: Macmillan. ↩ ↩

Lilly Library, Indiana University. 1970. An Exhibition of Books Presented to the Lilly Library by Mrs. Bernardo Mendel. Bloomington: Lilly Library, Indiana University. ↩

Mayor, Tomas. 1607. Simbolo de la fe, en lengua y letra china [Symbol of the faith, in the Chinese language and letters]. Binondo: Pedro de Vera (printer). ↩ ↩

Medina, José Toribio. 1904. La imprenta en Manila desde sus origenes hasta 1810: Adiciones y ampliaciones [The printing press in Manila from its origins until 1810: additions and amplifications]. Santiago de Chile: Impreso y grabado en casa del autor. ↩

―. 1896. La imprenta en Manila desde sus origenes hasta 1810 [The printing press in Manila from its origins until 1810]. Santiago de Chile: Impreso y grabado en casa del autor. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

Mentrida, Alonso de. 1630. Ritval para administrar los sanctos sacramentos sacado casi todo del ritual romano i lo demas del ritual indico. Con algunas advertencias necessarias para la administracion de los santos sacramentos. Con una declaracion sumaria de lo que las religiones mendicantes pueden en las indias por Privilegios Apostolicos, los quales se train a la letra. Recopilado por Fr. Alonso de Mentrida de la Orden de S. Augustin, para servicio, y uso de los ministeros de su orden en estas Islas Philipinas [Ritual for administering the holy sacraments drawn almost entirely from Roman ritual and the rest from Indian ritual. With some necessary warnings for the administration of the holy sacraments. With a summary declaration of what the mendicant religious can do in the Indies for apostolic privileges, which are brought to the letter. Compiled by Fr. Alonso de Mentrida of the Order of S. Augustin, for the service and use of the ministries of his order in these Philippine Islands]. Manila: Colegio de Sancto Thomas por [printed by] Thomas Pinpin and Iacinto Magarulau. ↩

―. 1618. Arte de lengua bisaya hiligayna de la isla de Panay . . . [Art of the Visayan Hiligaynon language of Panay Island . . .]. Manila: Oficina de los Jesuitas. ↩

National Archives. n.d. Currency Converter: 1270–2017. http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/currency-converter, accessed August 25, 2022. ↩

Nieva, Domingo de, trans. 1606. Memorial de la vida christiana en lengua china [Memoir of the Christian life in Chinese]. Binondoc: Pedro de Vera (printer). ↩ ↩

Osswald, Cristina. 2021. On Christian Martyrdom in Japan (1597–1658): El martirio Cristiano en Japón (1597–1658). Hipogrifo: Revista de literature y cultura del Siglo de Oro 9(2): 927–947. https://doi.org/10.13035/H.2021.09.02.63. ↩

Pagès, Léon. 1868. Dictionnaire japonais-français . . . traduit du dictionnaire japonais-portugais composé par les missionnaires de la Compagnie de Jésus et imprimé en 1603, à Nagasaki . . . et revu sur la traduction espagnole du même ouvrage rédigée par un père dominicain et imprimée en 1630, à Manille . . . publié par Léon Pagès [Texte imprimé] [Japanese-French dictionary . . . translated from the Japanese-Portuguese dictionary composed by the missionaries of the Society of Jesus and printed in 1603, in Nagasaki . . . and reviewed from the Spanish translation of the same work written by a Dominican father and printed in 1630, in Manila . . . published by Léon Pagès (printed text)]. Paris: Firmin-Didot fils et Cie. ↩

Palomino Olalla, Antolín. 1987. Autobiografía conocimientos y recuerdos sobre el arte de la encuadernación [Autobiographical knowledge and memories about the art of bookbinding]. Madrid: Imprenta Artesenal. ↩

Pardo de Tavera, Trinidad H. 1903. Biblioteca Filipina [Philippine library]. In Bibliography of the Philippine Islands. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. ↩

―. 1893. Noticias sobre la imprenta y el grabado en Filipinas [News about printing and engraving in the Philippines]. Madrid: Tipografia de los hijos de M. G. Hernandez. ↩ ↩

PBA Galleries. 2016. Lot 164 of 284: Vocabulario de Japon Declarado Primero en Portugues. Sale 601: Rare Books & Manuscripts. https://pbagalleries.com/lot-details/index/catalog/410/lot/128283?url=%2Fsearch%3Fkey%3Dvocabulario%2Bde%2Bjapon%26xclosed%3D0%26page%3D1, accessed September 29, 2023. ↩ ↩

Pearce, Susan M. 1994. Museum Objects. In Interpreting Objects and Collections, edited by Susan M. Pearce, pp. 9–11. London and New York: Routledge. ↩

Perez, Angél and Güemes, Cecilio. 1904. Adiciones y continuación de ‘La imprenta en Manila’ de D. J. T. Medina [ó] rarézas y curiosidades bibliográficas filipinas de las bibliotecas de esta capital [Additions and continuation of “La imprenta en Manila” by D.J.T. Medina (or) Filipino bibliographic rarities and curiosities from the libraries of this capital]. Manila: Imprenta de Santos y Bernal. ↩

Perez, Geronimo. 1639. Relacion de lo qve asta agora se a sabido de la vida y martyrio del milagroso padre Marcelo Francisco Mastrili de la Compañia de Iesus: martyrizado en la ciudad de Nãgasaqui del Imperio del Iapõ a 17 de octubre de 1637 . . . [Account of what until now has been known about the life and martyrdom of the miraculous Father Marcelo Francisco Mastrili of the Society of Jesus: martyred in the city of Nagasaki of the Japanese empire on October 17, 1637 . . .]. Manila: Collegio de la Compañia de Iesus, Impresor Tomas Pimpin. ↩ ↩

Plasencia, Juan de, et al. 1593. Doctrina Christiana, en lengua española y tagala [Christian doctrine in Spanish and Tagalog]. Manila: Dominican Press. ↩ ↩

Polastron, Lucien X. 2007. Books on Fire: The Tumultuous Story of the World’s Greatest Libraries. Translated by Jon E. Graham. London: Thames and Hudson. ↩

Quaritch, Bernard. 1887. Catalogue of Works in the Oriental Languages Together with Polynesian and African. London: Bernard Quaritch. ↩

Raven, James, ed. 2004. Lost Libraries: The Destruction of Great Book Collections Since Antiquity. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230524255. ↩

Retana, W. E. 1911. Origenes de la imprenta en Filipinas [Origins of the printing press in the Philippines]. Madrid: Librería General de Victoriano Suárez. ↩ ↩ ↩

―. 1906. Aparato bibliográfico de la historia general de Filipinas deducido de la colección que posee en Barcelona la Compañia General de Tabacos de dichas islas [Bibliographic apparatus of the general history of the Philippines deduced from the collection owned in Barcelona by the Compañía General de Tabacos of said islands], 3 vols. Madrid: Imprenta de la Sucesora de M. Minuesa de los Rios. ↩

―. 1897. La imprenta en Filipinas: Adiciones y observaciones á La Imprenta en Manila de D.J.T. Medina [The printing press in the Philippines: additions and observations on the printing press in Manila by D.J.T. Medina]. Madrid: Imprenta de la viuda M. Minuesa de Los Ríos. ↩

Sophia University. 2004. Vocabulario de Japón . . . [Japanese vocabulary . . .]. Laures Kirishitan Bunko Database. https://digital-archives.sophia.ac.jp/laures-kirishitan-bunko/view/kirishitan_bunko/JL-1603-KB28a-27-22, accessed February 11, 2018. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

Tronu, Carla. 2015. The Rivalry between the Society of Jesus and the Mendicant Orders in Early Modern Nagasaki. Agora: Journal of International Center for Regional Studies 12: 25–39. https://opac.tenri-u.ac.jp/opac/repository/metadata/3748/AGR001202.pdf, accessed February 28, 2023. ↩

Universidad Complutense de Madrid: Biblioteca Complutense. n.d. Vocabulario de Iapon . . . [Japanese vocabulary . . .]. https://ucm.on.worldcat.org/search/detail/1025367350?queryString=vocabulario de iapon&clusterResults=false&stickyFacetsChecked=true&lang=es&baseScope=sz%3A37628&groupVariantRecords=true&scope=sz%3A37628, accessed August 29, 2022. ↩

Van der Loon, P. 1966. The Manila Incunabula and Early Hokkien Studies. Asia Major: A British Journal of Far Eastern Studies 12: 1–43. ↩ ↩

Villarroel, Fidel. 1986. Pien Cheng-Chiao Chen-Chúan Shih-lu, Testimony of the True Religion: First Book Printed in the Philippines? Manila: University of Santo Tomas Press. ↩

Wasserman-Soler, Daniel I. 2016. Lengua de los indios, lengua española: Religious Conversion and the Languages of New Spain, ca. 1520–1585. Church History 85(4): 690–723. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0009640716000755. ↩ ↩ ↩

Wolf, Edwin 2nd. 1947. Doctrina Christiana: The First Book Printed in the Philippines, Manila, 1593. Washington, DC: Library of Congress. ↩

Zhang Wenxian. 2008. The Yellow Register Archives of Imperial Ming China. Libraries & the Cultural Record 43(2): 148–175. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25549473. ↩

1) “Rare” books are not necessarily old, just as “old” books are not necessarily rare. The distinction between the terms is particularly blurry in the case of Philippine books given that, in general, they are published in low print runs and tend to have short shelf lives due to conditions in the local environment that threaten their survival. A recently published book, for instance, might become a rarity shortly after its release if it were issued in a small edition that sold out and there remained a demand for it while out of print. The definition of a rare book itself is not always clear and simple for bibliographers and bibliophiles, although John Carter in ABC for Book Collectors notes that “Paul Angle’s ‘important, desirable and hard to get’ has been often and deservedly quoted” (Carter 1994, 175).

2) The books studied by Van der Loon in his survey are: Hsin-k’o seng-shih Kao-mu Hsien chaun Wu-chi t’ien-chu cheng-chiao chen-chuan shih-lu (A printed edition of the veritable record of the authentic tradition of the true faith in the infinite God, by the religious master Kao-mu Hsien) (1593); Doctrina Christiana, en lengua española y tagala (Christian doctrine in Spanish and Tagalog) (1593); Doctrina Christiana en letra y lengua china (Christian doctrine in Chinese letters and language) (c. 1605); Ordinationes generales provintiae Sanctissimi Rosarii Philippinarum (General ordinances of the Philippine Province of the Holy Rosary) (1604); Memorial de la vida christiana en lengua china (Memoir of the Christian life in Chinese) (1606); and Simbolo de la fe, en lengua y letra China (Symbol of the faith, in Chinese language and letters) (1607).

3) The title cited, which is in short form, is from the Dominican version of the book (Esquivel 1630d).

4) A number of sources credit Fr. João Rodrigues with the editorship of the dictionary, but Michael Cooper maintains that the identity of the editor “still remains a matter of conjecture. The best bet at present is that Francisco Rodrigues supervised the joint work of compilation before he sailed from Nagasaki in 1603 and was drowned in a shipwreck later in the same year. But this hypothesis, plausible as it may be, rests on the testimony of only one author—Daniello Bartoli—and he was writing in Rome more than fifty years after the event” (Cooper 1976, 428).

5) Some sources cite 1595 as the year of Esquivel’s birth. Laures, for instance, provides the date December 30, 1595 (Sophia University 2004).

6) José Eugenio Borao cites a slightly different title for the latter work, Vocabulario muy copioso de la lengua de los indos de Tanchui en la Isla Hermosa (An extensive vocabulary of the language of the natives of Tamsui on Isla Hermosa), which he says was finished in “1633 or earlier” (Borao 2001, 122).

7) As Borao notes, “The Dominicans certainly came [to Isla Hermosa] with long-sustained hopes and ambitions of entering China. They wanted a passage different from the route via Macao, because this had caused them many problems. Isla Hermosa was not only a better alternative, but it was a clandestine passage to Japan, whose doors were then absolutely shut to missionaries” (Borao 2001, 105).

8) See Boxer (1967), particularly Chapter 4, “Jesuits and Friars.”

9) On the fervent interest in missionary assignments in Japan as part of the revival of the cult of martyrs in Western Christendom during the early modern period, see Brockey (2017).

10) In 1634 a contradictory law was issued by Philip IV ordering “churchmen to ensure that the native peoples learn Castilian Spanish” (Wasserman-Soler 2016, 690). On the observance of these contrasting laws in Mexico, Daniel Wasserman-Soler contends that “the Spanish monarchs permitted a kind of linguistic coexistence between indigenous languages and Castilian” (Wasserman-Soler 2016, 693). This clearly differs from the situation in the Philippines and other lands in Asia that Spanish missionaries sought to Christianize, where the 1619 law seems to have taken effect or was more enforced, or was observed instead of the 1634 law.

11) Other than the Vocabulario de Iapon, the following Japanese books were printed in the Philippines during the incunabula period: Virgen S. Mariano tattoqi rosario no xuguioto, vonajiqu Iesusno minano cofradiani ataru riacuno qirocu (A short list pertaining to the followers of the Holy Rosary of the Blessed Virgin Mary, and of the confraternities of the Holy Name of Jesus) by Juan de los Angeles, printed in 1622; Virgen S. Mariano tattoq I Rosariono iardin tote fanazoni tatoyuru qio. Vanaiiqu Jesusno Cofradiano regimientono riaco (Garden of the Holy Rosary of the Blessed Virgin Mary or book similar to flowers. And a brief rule for the confraternity of Jesus), also by Juan de los Angeles, 1623; Lozonni voite aru fito svcaxono tevo voi yagate xixezu xite canauazarixi teitarito iyedomo, tattoqi Rosariono goqidocunite inochiuo nobetamo coto by an unidentified author, 1623; and Vareraga voaruji Iesv Christo S. Brigida, S. Isabel, S. Mitildesni tçuguetamo vonmino go Passiono voncuruximino iroxinano coto . . ., also by an unidentified author, 1623 (Jose 1993, 33–34).

12) Heber (1773–1833), the son of a wealthy rector, was recognized in his day as “the most indefatigable collector” of books (Clarke 2014, 288). He “is remembered today as the man who left eight houses, four in England, and one each at Ghent, Paris, Brussels, and Antwerp, all filled with books” (Basbanes 1995, 110). His entire collection was estimated to have comprised more than 200,000 volumes, covering “a full range of literary and historic interests,” and “his collections of foreign-language books, particularly works in French, Portuguese, Spanish, Greek, and Latin were superior” (Basbanes 1995, 110–111).

13) It has not been confirmed whether or not the copy of the Archivo Franciscano Ibero-Oriental currently remains in its collection or if elsewhere is still extant, as there is no record of it online, the author was unable to personally check the archive due to the Covid-19 pandemic, and queries made to the institution via email went unanswered.

14) The Vocabulario de Iapon was listed in Kirishitan Bunko: A Manual of Books and Documents on the Early Christian Mission in Japan, edited by Laures, published by Sophia University in 1940 (first edition), 1941 (second edition), 1951 (revised edition), and 1956 (third edition). This catalog of rare books held in Sophia University was revised, updated, and made available online in an electronic database in 2004. The copies in the Bodleian Library and the Biblioteca Real are listed in the bibliographical notation for the entry on the Vocabulario de Iapon.

15) It may be presumed that the “Librarian” referred to is Teodoro M. Kalaw, who served as director of the National Library of the Philippines from 1929 to 1938. It is not known who owned the copy he sold to Boxer, whether it was his own or the library’s, and how and why he came to sell it.