Contents>> Vol. 12, Supplementary Issue

Disguised Republic and Virtual Absolutism: Two Inherent Conflicting Tendencies in the Thai Constitutional Monarchy*

Kasian Tejapira**

*This is a translated transcript of my keynote speech “สาธารณรัฐจำแลงกับเสมือนสัมบูรณาญาสิทธิ์: 2 แนวโน้มฝังแฝงที่ขัดแย้งกันในระบอบราชาธิปไตยภายใต้รัฐธรรมนูญไทย,” originally given in Thai for the 14th International Conference on Thai Studies organized by the Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University, on May 1, 2022. I would like to thank Ajarn Piya Pongsapitaksanti of the Division of Sociology, Graduate School, Kyoto Sangyo University, and Professor Hayami Yoko of CSEAS for the initial transcription and translation of my talk. I have taken this opportunity to extensively revise, elaborate and improve upon its style and content. Final responsibility for the article of course lies with me. As supplementary materials, English slides from the presentation can be accessed from the link below: https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/seas/12/SupplementaryIssue/12_105/_article/-char/en.

**เกษียร เตชะพีระ, Professor, Thammasat University

e-mail: kasiantj(at)gmail.com

![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1701-521X

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1701-521X

DOI: 10.20495/seas.12.SupplementaryIssue_105

The current inclination towards monarchical absolutism of the Thai government and politics is in essence the actualization of one of the two conflicting tendencies that have been inherent in Thai constitutional monarchy from the start. I intend to trace the political and scholarly discourse about them at some key junctures in modern Thai history. My main argument is that it had been the royal hegemony of King Rama IX that managed to maintain a relatively stable if tilted balance between the opposing principles of monarchy and democracy and keep the two opposite tendencies at bay. The perceived threat of a disguised republic under the Thaksin regime and the waning of royal hegemony led to a hyper-royalist reaction from the monarchical network that disrupted the pre-existing balance and prepared a potential ground for a virtual absolutism which has been taken over and actualized under the present regime.

Keywords: disguised republic, virtual absolutism, Thai constitutional monarchy, the military, shogun, palladium, Walter Bagehot, Atsani Phonlajan

Good afternoon, dear friends, colleagues, and those who are interested in Thai studies. I would like to thank Kyoto University and the Japanese Society for Thai Studies for organizing this long-delayed conference. I would like to also thank Professor Tamada Yoshifumi and Professor Hayami Yoko.

Today’s topic, in English, is “Disguised Republic and Virtual Absolutism: Two Inherent Conflicting Tendencies in the Thai Constitutional Monarchy.” Why did I choose this topic? First, it is a response to the contemporary situation. During the last few years, prominent political and academic figures in Thailand have observed that the Thai political regime is changing in some strange and unexpected new directions. This is something that we should consider and respond to academically. So, on the one hand, it is the contemporary situation.

On the other hand, I am thinking of the overall study of modern Thai politics. In the past, the main axis of consideration has been the “2D-axis,” of either Democracy or Dictatorship. However, the political situation of the last decade, and particularly of the last few years, presents us with another axis—one that cuts across the original axis. That is, modern Thai politics is not only about “Democracy and Dictatorship,” but also about “Disguised Republic” and “Virtual Absolutism.” In plotting the characteristics of the Thai political order of a certain period, we may have to consider not only its authoritarian or democratic nature, but also other relevant characteristics that may make it either a disguised republic or a virtual absolutism. With this additional lens, I believe such a combined approach may help us to analyze Thai politics over a long period.

What I intend to do is to highlight the process by which I slowly came up with this idea, rather than to detail the idea, because the details are included on the slides, which can be read later. Today I would instead like to emphasize how the sequence of the logical thinking for this idea began.

Let us begin with a snapshot of the Thai political situation in the early 1990s. Thai politics at that time had come to a fairly stable state after experiencing three tumultuous trials and tribulations: the two-decade long civil war against the Communist Party of Thailand in 1985 (Saiyud 1986, 179–188), the Cold War on a global and regional level in the early 1990s,1) and the mass uprising against the military government in the 1992 Black May incident (Charnvit 2013, 3–117). Having overcome these significant threats and crises, Thai politics settled into a political order called the Democratic Regime of Government with the King as Head of State.2) This reasonably stable regime lasted until 2006, when it faced a new crisis, which began with a mass movement and coup d’état against the popularly elected government of Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra and has not stopped since. So far, this protracted crisis has continued for roughly 15 years.

Politically speaking, it has been a turbulent 15 years: during this period Thailand has had six prime ministers, not including the acting ones,3) experienced two coups,4) and adopted four constitutions.5) On top of that, nine waves of huge anti-government mass protests by both the yellow-shirt and red-shirt sides6) have resulted in five major bloody repressions by state security forces, with hundreds of civilians killed and thousands wounded, not to mention economic damage worth hundreds of billions of Baht.7)

Given the situation, some people began to draw public attention to the political malaise as an anomaly that deviated further and further away from the traditional Democratic Regime of Government with the King as Head of State. Out of the hitherto stability, there seemed to emerge a threat in the form of a regime that could replace in toto a constitutional monarchy, or the Democratic Regime of Government with the King as Head of State. Contrary to the former threat during the Cold War, the current threat to the Thai constitutional monarchy does not come from outside the system in the form of an anti-system communist armed struggle. Rather, this round of threats is unique in that it is embedded within the constitutional monarchy itself as latent inherent tendencies. Two specific conflicting tendencies have manifested themselves alternately during the last 15 years.

The matrix of the two conflicting tendencies was clearly articulated in 2006 by Professor Dr. Nakharin Mektrairat, a member of the current Constitutional Court who was elected by the coup-installed National Legistrative Assembly in 2015. In the foreword to his book The Case of King Rama VII’s Abdication, he notes that Thai politics is extraordinary in that the conceptually incompatible notions of “monarchy,” i.e., rule by one person, and “democracy,” i.e., rule by many or by all the people, have been made compatible in practice in the form of the Democratic Regime of Government with the King as Head of State. Nakharin commends this merging of monarchy and democracy Thai style as an ingenious, phenomenal intellectual and political construct in the modern world (Nakharin 2006, 5). However, developments in Thailand since 2006 have deeply destabilized the said regime and put it out of sync with itself.

An early and significant alarm came in 2007 from Jaran Pakdithanakul, the deputy chairman of the constitution drafting commission formed after the 2006 coup d’état against the Thaksin government. He had played a key role in the judiciary as a former Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Justice, and later as a member of the Constitutional Court. He criticized the 1997 constitution for introducing a mixed-member majoritarian representation with an unlinked partial party-list electoral system that had a countrywide single constituency. This change from the previous block voting system, Jaran argued, deformed Thai politics, transforming it from a parliamentary regime to a de-facto presidential one. This led to the unfortunate opportuneness by the head of the party that won the most party-list votes to mistakenly arrogate to himself/herself the monarch-like stature of the Lord of the Land.8)

On the other hand, in 2019 Ajarn Nidhi Aeusrivongse, a foremost Thai historian and public intellectual, cautioned against the 2017 constitution in view of its actual non-observance. This came after the Constitutional Court’s ruling in the case of the Cabinet, led by PM General Prayut Chan-o-cha, taking an incomplete (as specified by the constitution) oath of allegiance to King Rama X. The Court ruled that the Cabinet’s oath-taking to the King was an exclusive mutual relationship between the two institutions in which no one could interfere. Therefore, if the King raised no objection to the incomplete oath, then it was acceptable (although it went against the provision of the Constitution). In view of the ruling, Nidhi suspected that Thailand no longer had a Democratic Regime of Government with the King as Head of State, but a Democratic Regime of Government with the King above the Constitution. We must remember that this new regime had been furtively ushered in neither by a coup nor a new constitution. And yet, it was not a pure monarchy either, since the prime minister was nominated by a Parliament consisting of an elected House of Representatives and an appointed Senate. What resulted was a peculiar regime that did not conform to the usual principles of constitutional monarchy (Nidhi 2019).

The next group of people that called out this peculiar regime was the Move Forward Party (พรรคก้าวไกล), a newly reconstituted version of the Future Forward Party (พรรคอนาคตใหม่), which had been disbanded by the Election Commission. In March 2022, they vowed to undertake as their political mission the defense of democracy from “an absolutist authoritarian dictatorship (เผด็จการอำนาจนิยมสมบูรณาญาสิทธิ์)” (Move Forward Party, March 25, 2021).

I would like to argue here that the aforementioned disparate voices represent a call to the Thai public on the emergence of two separate and opposing anti-system political alternatives to the Thai constitutional monarchy, or the so-called Democratic Regime of Government with the King as Head of State. These alternatives were, namely, a Disguised Republic (à la Jaran Pakdithanakul) and Virtual Absolutism (à la Nidhi Aeusrivongse and the Move Forward Party). Both alternatives are conflicting tendencies that have been inherently embedded in the Thai constitutional monarchy from the start, i.e., the 1932 constitutionalist revolution that held on to the monarchy while ridding it of absolute power. However, they have become politically manifest during the last 15 years or so due to the unravelling of the conditions that had made “democracy” and “monarchy” compatible and coexistent until then in Thai politics.

The said conditions, as commended by Nakharin, consisted mainly of the largely moderate and compromised character of Thai democratization since its inception in the 1932 unfinished revolution as well as the later cautious conservative reformist hegemony of King Rama IX’s reign (1946–2016) that developed intermittently in the 1970s and reached its apogee in the early 1990s, resulting in the Bhumibol consensus.9) The rise of the strong, popularly elected Thaksin government in the early 2000s, the subsequent protracted political polarization and violent conflict between the anti-Thaksin yellow-shirts and the pro-Thaksin red-shirts, the glaring politicization and increasing authoritarianization of the monarchy in two successive coups in 2006 and 2014, and the aging and declining health of King Rama IX led to the waning of royal hegemony in the final years of his reign amid a burgeoning new wave of progressively radicalized democratization. The conditional ties between monarchy and democracy thus loosened and unraveled to the extent that a new generation of audacious young activists have begun to seriously question their compatibility and coexistence.

Next, I would like to probe, in a manner similar to “conceptual digging” or excavation work, the discourse and concepts of the two alternative regimes of Disguised Republic and Virtual Absolutism as they appeared in Thai politics, culture, and literature, so as to unearth a preliminary archaeology of the said concepts. I would like to show how past Thai scholars and poets, activists, and revolutionaries spoke about or alluded to these two inherent anti-system tendencies.

My point of entry is Walter Bagehot’s classic The English Constitution, first published in 1867. This book was used as an authoritative reference when I studied Thai government and politics in university, as it helped clarify the fundamental principles of the Democratic Regime of Government with the King as Head of State in Thailand. Leading mainstream senior Thai scholars who wrote about the Thai monarchy and politics, be they the late Dr. Kasem Sirisamphan (former Dean of the Faculty of Journalism, Thammasat University, who was a minister during the government of MR. Kukrit Pramoj in the 1970s), or Professor Bowornsak Uwanno and Professor Tongthong Chandransu (two foremost royalist legal scholars and government advisors who published standard textbooks and a thesis on the Thai monarchy and politics), also always referred to this book. In particular, they referred to the same single point in the book: what political rights the monarch as a sovereign had in a constitutional monarchy. In summary, Bagehot argues that three rights belong to the constitutional monarch in relation to the government of the day: the right to be consulted, the right to encourage, and the right to warn (for the application of this in Thailand, see Kamnoon 2005; Tongthong 2005, 60–62, 74–76).10)

The frequent referencing of the text aroused my mounting curiosity and interest in the book, which was finally satisfied when nearly forty years ago I found and bought a 1963 edition in a used book store near Cornell University, my alma mater. Much to my surprise, the relevant text concerning the monarch’s political rights in a constitutional monarchy occupies only a single paragraph (Bagehot 1963, 111) in a four-page-long overall discussion of this topic. The discussion is included only in one chapter (Chapter 2, “The Monarchy”) of the eight-chapter book. Needless to say, the above-mentioned conventional Thai scholars’ usage was a highly selective reading of Bagehot’s classic text, which is generally considered an authoritative reference work on the British model of constitutional monarchy. In short, Thai scholars of the Thai constitutional monarchy have arbitrarily and bafflingly made use of a single paragraph from a few pages in a single chapter of the 208-page book as their main point of reference. The question is, why?

My further research indicates that knowledge of the author’s professional and political background is important in understanding his realistic and reflective position toward the English constitutional monarchy. Who, then, was Walter Bagehot? Bagehot lived from 1826 to 1877 in England and he was responsible for making The Economist weekly magazine famous across the globe. The Economist was originally founded, owned, and edited by Bagehot’s father-in-law, James Wilson (1805–60), a Scottish businessman, economist, and Liberal politician, but as he aged and had health problems, Bagehot succeeded him in 1859. Bagehot developed the magazine, turning it into a leading liberal business elite publication in the Western world (The Economist, August 8, 2019).

What were Bagehot’s political and economic views of England? Based on The English Constitution, his other writings, and his biographies (of which there have been several in recent years), one can conclude that he was a hard-boiled bourgeois political analyst. He analyzed the English constitutional monarchy in very realist and instrumentalist terms. That is, he began from the actual role the monarchy played as a tool for the existing regime. One might be inclined to think that, since The English Constitution has been cited by Thai scholars who highly value the role of the monarchy in Thai politics, Walter Bagehot must have been a devotee of the monarchy. This was not the case. Actually, Bagehot had an extremely cold-hearted view of the British monarchy (Collini 2020).

Many passages in the book reflect Bagehot’s view, but I would like to highlight two of them. First, Bagehot’s answer to the question of why the British monarchy should continue to exist—that most English people were still stupid—is very blunt and brutal, although it may sound familiar to the Thai public. He argued that the British monarchy was still needed, to enchant, tame, and shepherd the uneducated populace. In case anyone did not believe this, he said, they should try striking up a conversation with servants in a kitchen and they would surely find that the servants could not comprehend what was normally easy to understand. As long as the British were like this, Bagehot said, the British monarchy was still necessary (Bagehot 1963, 62–63).

Second, Bagehot describes royal ceremonies or official celebrations in Britain—those of a spectacular parade of mounted cavalry, line infantry, and carriages for VIPs on the streets of London—to point to the monarchy’s utility. Usually, the magnificently decorated royal carriage would lead the procession, followed by more plain carriages for the PM, Cabinet members, and so on. The English people, Bagehot explains, keenly watched and highly appreciated such parades as a kind of theater. Their gaze naturally focused on the royal carriage at the head of the procession, which carried the King and Queen of England, while scant attention was paid to the carriages that followed. And yet, the real power to govern the country lay precisely in those carriages behind, those that the spectators were less interested in. The function and utility of the front carriage, then, was to win the consent of the English people to the new political order that was in fact run by the back carriages. Hence, the real function and utility of the monarchy in the English constitutional monarchy (Bagehot 1963, 248–249).

From these examples, we can clearly see that Walter Bagehot was no sentimental, heartfelt “royalist” in the usual Thai sense of the term. Rather, he provided clear-eyed, searing analysis of the British monarchy from a “realist” and “instrumentalist” perspective.

Now, in terms of conceptual tools for analyzing the English constitutional monarchy, what did he propose? He proposed the following: a division of the unwritten and traditional English constitution into two main parts, namely the “Dignified Parts” (or the prestigious and “exciting” parts), which aimed to “preserve the reverence of the population.” These were the parts of the constitution that people honored and respected, and they included the monarchy and the House of Lords. The other main part of the English Constitution consisted of the “Efficient Parts,” which were in fact, those that governed. These included the Cabinet and the House of Commons (Bagehot 1963, 61).

Bagehot used the changing relationship between these two parts to describe the evolution of the English constitutional monarchy: that in the “Absolute Monarchy” era of English politics, the dignified and the efficient parts of the English constitution were united in the King.11) Later, as the power of the English monarch became limited, sovereign powers were shared between the King and the landed aristocracy in a period called “Early Constitutional Monarchy,” when the House of Commons exerted some checks as the people’s representative.

Bagehot paradoxically described England since 1832, in a period dubbed “Mature Constitutional Monarchy,” as “a Republic [that] has insinuated itself beneath the folds of a Monarchy” (Bagehot 1963, 94). That is, the dignified and efficient parts of the constitution were separated and then welded together. The dignified parts were maintained to conceal from the public the revolutionary shift in power that took place behind the scenes. In fact, sovereign powers moved decisively from the dignified parts to the efficient parts, i.e., to the Cabinet and the House of Commons. Consequently, according to Bagehot, the true if oblique nature of the mature English constitutional monarchy was “a disguised republic.”12)

In other words, a sub-component of the monarchy was converted into a republic-like quintessence. What used to be a subordinate, supporting element was transformed into the superordinate essence of the regime, which was still dubbed a constitutional monarchy, but, for all intents and purposes, functioned as a republic. The constitutional façade was meant to obscure from the public that real power had already moved from the dignified and enchanting monarchy and House of Lords to the ordinary and mundane Cabinet and House of Commons.

Thus, simply put, there begot an inherent potential within a mature constitutional monarchy to become a disguised republic wherein executive power lay in the hands of bourgeois commoner politicians. The monarchy was accordingly merely a symbolic figurehead that served to decorate and sanctify the utilitarian capitalist state power of the bourgeoisie. Therefore, far from simply inscribing the three political rights of the sovereign monarch in a constitutional monarchy, the main thrust of Bagehot’s political arguments in The English Constitution is that a mature constitutional monarchy is essentially a disguised republic, with the monarchy retained as a cultural-ideological apparatus for the purpose of placating and duping the working-class public and defeating, or neutralizing, their democratic demands.

Such a blunt message clearly strikes a discordant note to the ears of Thai mainstream conservative scholars, both past and present. Furthermore, it coincides with the anxiety of Thai royalist public intellectuals, who detest any meaningful changes to the Democratic Regime of Government with the King as Head of State à la King Rama IX. And it is precisely such changes that have taken place since the Thaksin government came to power in 2001.

Prominent among the said royalist public intellectuals at that time was Mr. Kamnoon Sidhisamarn, a well-known veteran journalist and columnist, as well as a leader of the right-wing, royalist People’s Alliance for Democracy (PAD) mass movement who later became a junta-appointed Senator (and who remains a Senator today). In his memoir of the PAD’s initial rallies against the Thaksin government in 2006, The Sondhi Phenomenon: From Yellow Shirts to Blue Scarves (2006), Kamnoon avows that he cannot possibly accept a key principle of the constitutional monarchy, that “the King can do no wrong,” if it means in practice that “the King can do nothing” (Kamnoon 2006, 70–71).

Implicitly, Kamnoon wanted the King, within the Thai constitutional monarchy, to retain the royal prerogative to independently carry out important political tasks, especially in times of crisis. Chief and most urgent among these at the time was the replacement of then elected PM Thaksin Shinawatra with a new royally appointed prime minister to lead an essentially anti-democratic and counter-majoritarian political reform process. Kamnoon perceived the same threat that alarmed Jaran Pakdithanakul in the foregoing discussion, namely the emergent tendency toward a disguised republic, represented by the Thaksin regime.

At this point, I want to take you in another direction, to review some landmarks in the political, literary, and scholarly literature on Thai politics that have reflected on and discussed the two tendencies of disguised republic and virtual absolutism in the Thai constitutional monarchy.

Two key works first caught my attention. One is an essay written by Thailand’s late Senior Statesman, Dr. Pridi Banomyong (1900–83) entitled “Defend the Spirit of Complete Democracy of the Heroes of October 14th.” It was written in late 1973 in commemoration of the historic student and popular rising against military rule on October 14 of that year. Residing in Paris at the time, Pridi was 26 years into his exile following a military coup in 1947. He wrote the essay in response to the Thammasat University Student Union’s supplication (Pridi 1992, 171–195). The second work is “Withdrawal Symptoms” (1977), a celebrated scholarly intervention by the late Professor Benedict Anderson, a world-renowned scholar of Southeast Asian Studies and Nationalism and a beloved teacher of mine at Cornell University, in the aftermath of the bloody state massacre and coup on October 6, 1976 in Thailand (Anderson 2014a).

Coincidentally, both these works mark historic incidents in modern Thai politics. I read them on different occasions for unrelated purposes. But one day I came to notice that both Ajarn Pridi and Khru Ben13) happened to cannily use the same couple of terms in their comparative analyses of Thai politics, namely shogun (general) and roop thepharak (image of palladium).

Ajarn Pridi said that in eleventh century-Japan, the emperor had no real power, even though he was supposed to descend from the Sun-God. In fact, ruling power rested with the shogun, who was a dictator (Pridi 1992, 192). Ajarn Pridi raised this point to compare the actual power relationship between the emperor and the shogun in age-old Japan with the relationship between the king and the military dictator in modern Thailand.

Khru Ben made much the same point when he stated that the regime of Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat actualized the shogun’s autocratic characteristics latent in early military rule under Field Marshal Plaek Phibunsongkhram. Therefore, real effective ruling authority lay in the shogun-like prime minister, or the efficient parts of the constitution à la Bagehot, not in the king, or the dignified parts (Anderson 2014a, 69).

What then is the function of the king under Thai military dictators? Both Ajarn Pridi and Khru Ben also compared the monarchy to a sacred object without real power. Ajarn Pridi, writing in Thai, used the word roop thepharak, while Khru Ben, writing in English, used the word “palladium” (Pridi 1992; Anderson 2014a, 68). Thepharak denotes “an angel who protects a certain place” (Royal Institute 2011), whereas a palladium signifies “a safeguard or source of protection,” or “a protecting deity” (Fowler et al. 1995). Their meanings are evidently close enough to be considered equivalents. Therefore, without any premeditated plan or coordination, two different acknowledged authorities on Thai politics who wrote on two different occasions concurred on the use of shogun and palladium to describe and conceptualize the power relationship obtained between military rulers and the king in the Thai constitutional monarchy under military dictatorship.

What does this tell us? It tells us that in the Thai constitutional monarchy, a “military dictatorship” can also be a “Disguised Republic,” as was the case under Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat (1959–63) and Field Marshal Thanom Kittikachorn (1963–73). The analyses of both Ajarn Pridi and Khru Ben reached the same conclusion. One should also note at this point that a similar concern about a “Disguised Republic” has been raised during the past two decades in Thailand; this was caused by the Thaksin regime, comprising various governments of Thaksin Shinawatra and his nominees between 2001 and 2014. These were all civilian administrations that came to power via elections, unlike those of Field Marshal Sarit and Thanom. Therefore, a “Disguised Republic” can emerge either in the form of a military dictatorship via coup or a civilian democracy via election.

Then, where does the other inherent tendency, of virtual absolutism, in the Thai constitutional monarchy come from? Although Walter Bagehot never mentioned it in The English Constitution, by following the same logic that Bagehot used in his conception of a “Disguised Republic” in reverse, one can conceive of a virtual absolutist eventuation. Instead of having the all-powerful efficient parts of the constitution welded together with the essentially symbolic dignified parts, as in a mature constitutional monarchy or “Disguised Republic,” one can have it the other way round. That is, the dignified parts of the constitution can become more and more powerful to such an extent that the conjoined and politically dependent efficient parts are under their de facto, if not de jure, thumb, resulting in a “Virtual Absolutism.”

To my surprise, I found that some Thai revolutionaries of yore had already remarked on and cautioned against such a possibility when they contemplated and conspired to overthrow the absolute monarchy back in 1912 under King Rama VI or Vajiravudh (1910–25). Of course, I am referring to radical members of the Kek Meng (“revolutionary” in Teochew dialect) rebel group of junior army officers led by Captain Leng Srichan (silpa-mag.com, February 15, 2021).

Discontented with their professional prospects and meager pay, disillusioned with the undignified personal behavior and anti-regular armed forces disposition of King Rama VI, and influenced by democratic ideas and movements from China and the wider world, these junior army officers came to agree on the need for the removal of absolute monarchy and a regime change early in the king’s reign. Formed as a clandestine conspiracy inside the army, the Kek Meng group secretly, if not very discreetly, held anti-monarchist lectures, recruited new members, and expanded rather rapidly. Initially, the radical wing that comprised the group’s majority preferred an outright republic as their revolutionary goal. However, the moderate wing, which came to dominate the group numerically afterwards, opted for a constitutional monarchy instead and outvoted the radical wing.

With hindsight, what is interesting is the reasoning provided by the radical wing of the Kek Meng group for their republican preference, i.e., they were afraid of a possible “reversal” or “return” of the ancien régime. They feared that the continued existence of the monarchy, albeit with no real power in a “limited monarchy,” might provide the King with an opportunity to restore his status above the law. Simply put, they dreaded that in a constitutional monarchy, the “dignified parts” of the constitution, under conducive circumstances, might find it opportune to rise above the “efficient parts” and reclaim ruling power. Therefore, they found it politically prudent to simply change to a republic (Nattapoll 2012, 76–94).

In the end, the Kek Meng group was betrayed to the absolute monarchy authorities by a newly recruited member; its members were arrested, tried, and jailed for treason; and the whole conspiracy came to naught politically (see Kullada 2004). And yet its radical wing was the first to anticipate and sound the alarm about a possible emergence of a “Virtual Absolutism” in a Thai constitutional monarchy. Recent political developments in Thailand seem to have proven them prescient indeed.

Let us turn next to some recent academic works that have picked up and discussed this tendency toward “Virtual Absolutism.” First is a 2016 article entitled “The Resilience of Monarchised Military in Thailand” (Chambers and Napisa 2016). The authors propose that to explain the political action of the Thai military, it is inadequate to merely look at their economic and/or corporate interests. One must also focus on the crucial relationship between the Thai military and the monarchy. The former’s loyalty to the latter and its royalist ideology is key to understanding their political behavior. The authors coin the term “monarchized military” to capture the asymmetrical relationship between the two political actors and to signify the monarchy’s ideological hegemony and command over the Thai military, which usually yields to the royal will.

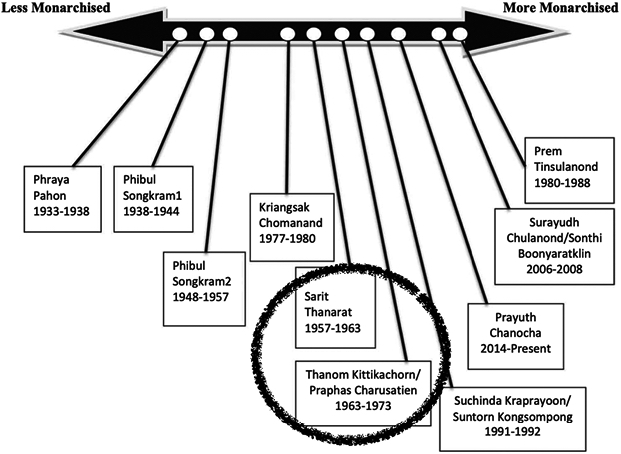

To illustrate the changing configurations of the “monarchized military” in Thailand, the authors devise a graphic depicting the degrees of monarchization of military rulers in Thailand since the 1932 constitutionalist revolution (Fig. 1 above and on p. 430 of the article). Those that appear on the left of the graphic are military prime ministers considered “less monarchized,” while those on the right are deemed “more monarchized,” so to speak. Thus, the less monarchized military PMs include Phraya Pahon and Field Marshal Phibunsongkhram, whereas those considered more so include General Prem Tinsulanonda and General Prayut Chan-o-cha.

Fig. 1 Degree of Monarchization in Thai Military-Dominant Regimes

Source: Chambers and Napisa (2016, 430; circle added by the author).

To put it in Bagehot’s parlance, in a less monarchized military government, “the efficient parts” dominate “the dignified parts” (i.e., a “Disguised Republic”) while a more monarchized one indicates vice versa (i.e., a “Virtual Absolutism”).

The dynamics of the monarchization of the Thai military can be gleaned from a recent important work on the Thai network monarchy, namely, “To Achieve Royal Hegemony: The Evolution of Monarchical Network in Interaction with the Thai Elites, BE 2490s–2530s” (2021), a doctoral thesis-based book by Dr. Asa Kumpha, a researcher at the Thai Khadi Research Institute, Thammasat University (Asa 2021). Asa depicts the dynamics of royal power during the reign of King Bhumibol or Rama IX (1946–2016), specifically, how he achieved royal hegemony as well as influenced and upheld a political consensus among Thai elites of different power bases, which I dub the Bhumibol consensus (Kasian 2017). These political achievements of the King made possible the paradoxical coming together of democracy and monarchy under his reign, as extolled by Nakharin.

Asa also analyzes the fluctuating nature of royal hegemony. In the case of King Bhumibol, his royal hegemony was gradually built up and accumulated through royal-nationalist discourse, monarchical network, and royal-initiated development projects under Field Marshals Sarit and Thanom’s absolutist military dictatorship (1958–73). It reached maturity on the October 14, 1973, when the King sided with the student protest movement against military rule. The power vacuum in the aftermath of the fall of the military government allowed the King to reclaim sovereign powers and step in to reconstitute the Thai polity in a democratic and reformist, if conservative, direction (Kasian 2016).

Subsequently, the American military withdrawal from Indochina and Thailand, the growing regional influence of the People’s Republic of China, the spreading communist-led guerrilla war in the Thai countryside, the counter-hegemony of the increasingly radicalized Thai student movement, domestic political polarization, and state-sponsored far-right activism and terrorism, all led to an increasing fanaticization of royal-nationalism, the decline of royal hegemony, and the October 6, 1976 inhumane massacre and coup (Anderson 2014a, 47–76).

Unexpected and fortuitous developments in the 1980s helped salvage royal-nationalism and royal hegemony from a blind, suicidal rightist extremization. A moderate, if opportunistic, military coup in 1977 put a timely end to the royal-backed, right-wing Thanin Kraivixien government. Under the rule of the loyal, reformist, semi-democratic government of General Prem Tinsulanonda, both the far-left alternative of communist revolution and the far-right military dictatorship were defeated. At the same time, the Thai economy greatly benefited from a new policy direction of export-oriented industrialization, the windfalls of natural gas discovery in the Gulf of Thailand, the stronger Yen, and an enormous incoming wave of Japanese FDI (Anderson 2014b, 101–115).

In particular, the auspicious celebratory occasion of the 200th anniversary of the founding of Bangkok in 1982 followed close on the heels of the bloodless subjugation of the Young Turk rebellion against the Prem government staged by a group of hot-headed rising army colonels one year earlier. The royal family’s publicized and unequivocal siding with PM General Prem was decisive in turning the political tide against the Young Turk rebels and proved to the Thai business class and public that royal hegemony trumped even greater firepower (Asa 2021, 377–417).

King Bhumibol’s royal hegemony reached its zenith in the form of the Bhumibol consensus in the aftermath of the May 1992 popular uprising against the military government of PM General Suchinda Kraprayoon. Nothing captured the essence of royal hegemony better than the televised newsreel showing PM General Suchinda and Major General Chamlong Srimuang, the leader of the anti-government mass protest movement, kneeling in audience with the king and listening docilely to his majesty’s admonition as to the importance of peace and national reconciliation (Asa 2021, 419–496).

The next scholarly work to note is one that most students of recent Thai politics know: the 2016 “deep state” essay by Eugénie Mérieau entitled “Thailand’s Deep State, Royal Power and the Constitutional Court (1997–2015).” In this important work, Mérieau describes and analyzes the Thai ruling elite’s efforts to adapt to the then imminent post-Bhumibol era, given King Rama IX’s deteriorating health and the challenges to royal hegemony and the Bhumibol consensus posed by the resilient Thaksin network and militant mass movements. The upshot, according to Mérieau, is the deep state’s institutionalization of its judicial component—in the form of the Constitutional Court—to function as a “surrogate king”-like legitimizing substitute for the aging king in an attempt at hegemonic preservation during the approaching crucial period of transition of the reign.

Mérieau notes that at key moments since its establishment, the Constitutional Court has exercised sovereign powers that it is not constitutionally entitled to, as those powers rightfully belong only to the people and their legitimately elected representatives. This specifically includes the power to amend the constitution. In 2013, the Constitutional Court blocked the House of Representatives from doing precisely that, thus arbitrarily usurping le pouvoir constituant originaire ou absolu (the original or absolute constituent power), which belongs properly and exclusively to the people or their rightfully elected representatives (Avril and Gicquel 2013; Toupictionnaire). From then on, we can observe a tendency toward “Virtual Absolutism.”

What were some key conditions for the emergence of “Virtual Absolutism”? I think there are a few. First, it is imperative that the Thai monarchy is not a “political object” (as had been the case in Japan after the Meiji Restoration), but rather it retains the inclination and capacity of a “political subject” (or actor) even in a presumably constitutional monarchy. This was pointed out by Professor Benedict Anderson in his consummate, wholesale, pathbreaking and iconoclastic review of Thai studies in the US academy, “Studies of the Thai State: The State of Thai Studies” (Anderson 2014c, 25–27). Obviously, only when the king is a “political subject” and can do something as wished for by Kamnoon, could a “Virtual Absolutism” be possible.

Second, as observed by Ajarn Thongchai Winichakul in his 2016 research entitled Thailand’s Hyper-Royalism: Its Past Success and Present Predicament, there had been a high tide of “hyper-royalist” ideological campaigns and mass movements in the previous ten years.14) This can also be considered an enabling factor contributing to the rise of “Virtual Absolutism.”

The third factor is presented in a penetrating historical analysis entitled The Invention of History (2001) by Dr. Somsak Jeamteerasakul, a former Thammasat lecturer specializing in Thai monarchy studies who became a political refugee in France in the aftermath of the 2014 coup by the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO) (Prachatai English, June 27, 2015). Commenting on the political turmoil following the 1932 constitutionalist revolution in Siam, he points out that the prime ministership was the key strategic position in the overall configuration of the new Thai constitutional monarchy regime. Thus, to have a loyal and obedient king’s man, like the first Prime Minister Phya Manopakorn Nitithada, in office would be enough to satisfy King Rama VII or Prajadhipok. What really bothered the king and eventually led to his abdication in 1935 was not the December 10th, 1932 permanent constitution per se, but rather the removal of PM Phya Mano from office via a coup by Colonel Phya Phahon Phonphayuhasena, Head of the revolutionary People’s Party and the new congenial but unyielding PM. In other words, for the Thai constitutional monarchy to effectively become a “Virtual Absolutism,” the king must have the right prime minister in place (Somsak 2001, 9–19).

In conclusion, to sum up my entire argument in a nutshell, let me present an extraction from a long Thai poem by Naiphi (or Mr. Specter, a penname of Mr. Astani Phonlajan, 1918–87), entitled “Change” and composed around 1952 (Astani 2014, 67–118). Born to a noble family, Astani was among the first batch of graduates from Thammasat University (back when its name was still the University of Moral and Political Sciences) after it was founded by Pridi Banomyong in 1934 to train adult citizens in law and politics for the new constitutional regime. Astani was a famed poet, a radical columnist, and an incorruptible prosecutor during and after WWII before joining the banned Communist Party of Thailand as a convinced communist and going underground in 1952.15)

It was around that time that he penned “Change,” not as a stylized narrative of his personal profile and family background, as suggested by Mr. Naowarat Pongpaiboon, the first Thai S.E.A. Write Awardee for poetry and later a pro-NCPO senator, in his forward (Naowarat 1990) to the 1990 edition of Naiphi’s poem (Astani 1990). Rather, I would like to argue, he wrote it as a running, incisive and prescient commentary on Thai politics past and then, more precisely on the 1932 revolution against absolute monarchy and the unsettled and problematic power nexus between the monarchy and the military at the heart of the Thai constitutional monarchy as well as its alternate dynamics toward a “Disguised Republic” or a “Virtual Absolutism.”16)

Let us hear from the melodious, wise, and prophetic words of Naiphi (in my translation):

Mr. Specter’s poetic riddle (excerpts from the poem “Change,” 1952)

|

“What where why |

|

| Boom! Boom! Boom! Boom! | Bombs explode and people die. |

| From early till late morning | The roaring never dies down. |

| Artillery fires rain down upon us | Like gushing fireworks, |

| Shaking the earth, | Rumbling all over Thailand. |

| The age of commotion arrives | With horrendous volatile chaos. |

| Burning earth and sky | Crackling flames on the pyre. |

| The old corpse has become rotten | Covered with crawling worms. |

| Lying on the pyre for years | Waiting to be cremated. |

| Foul smell spreads | From the ancient cadaver. |

| Rice husk ashes used to cover it | Fail to prevent its odor from spreading far and wide. |

| The corpse’s bereaved descendants | Keep it for memorial sake |

| In an artificial coffin | Made of myrrh wood. |

| Weaving a garland | Of refreshing floral scent, |

| And yet it’s no match for | The pungent smell of cadaver. |

| The unrelated folks | Harbor no longing for the cadaver. |

| They want very much to cremate it | And yet fear the dangers involved. |

| For this is no common corpse | But that of the Leonine, |

| Whose descendants | Still jealously guard it. |

| Then the four fierce warriors | With defiant courage |

| Rush in to burn the corpse | Firm in their merciless resolve. |

| The lying-down rats | Jump around the coffin. |

| It becomes engulfed in flames | And the angels vanish away. |

| A Javanese musical pipe | Cries resoundingly |

| As though the solid earth | Shrinks with cold fear. |

| Saddened by the Lacrimosa | Weakened by the final farewell, |

| The heart is pierced | By torturing chants. |

| Wailing sobbing female mourners | Cry their hearts out |

| That the retinue | Will suddenly disappear; |

| The reign will come to an end | In squirming wriggling sorrow; |

| The longstanding law and rule | Will completely vanish; |

| The cumulative culture and philosophy since time immemorial | |

| Will become extinct. | |

| Whatever resists karma and fatality | Will be destroyed |

| Birth, aging, sickness and death | Are the fate of everyone. . . . |

| The voices of bourgeois commoners | Are irrelevant sound effects |

| That aren’t worthy | Of thy attention. |

| Then the bourgeoisie | Could no longer bear it |

| And rise up to burn down | Their misery into ashes. |

| They are the four fierce warriors | With defiant courage |

| Who rush in to burn | The utterly rotten cadaver. |

| While the peasant serfs | Stay neutral and refuse to fight, |

| The feudal lords feel distressed | And deeply disheartened. |

| They ask for the ashes | And longingly worship them. |

| They then erect a shrine | To shelter and honor the ghost. |

| And the four fierce warriors | Set up a figurehead |

| Then put it in the shrine | To serve as a contrivance. |

| Of connivance and conflict | Circumstances necessitate pretense, |

| To dupe people into | Being forever fearful. |

| One side tries to resurrect the ghost | So that it may become omnipotent |

| While the other side flanks the shrine | To cast on people a spell. |

The telltale sign is “the four fierce warriors,” or “สี่ทหารเสือ,” which evidently refer to the four colonels who led the army faction of the People’s Party (see Matichon Weekly, June 24, 2017). With that, most of the above-cited stanzas are an oblique narration of the eventual overthrow of the Thai absolute monarchy in 1932, allegorically portrayed as a long-delayed cremation of an ancient, stinking corpse. However, the most interesting stanza is the last one of the excerpt, which describes the possible alternate power relationship between the two sides, namely the monarchy and the military, in the shrine-like political setting of a constitutional monarchy regime.

While the monarchy and its allies try to resurrect royal power and monarchize the military so that the constitutional monarchy regime may become a “Virtual Absolutism,” the military in turn attempt to flank and effectively control the monarchy as a praetorian guard in order to enchant the people in a “Disguised Republic” under their rule.17)

That, in a rhyming nutshell, is the real political equation of the Thai constitutional monarchy, detected and revealed long before the fact by the piercing and prophetic Mr. Specter.

References

Aim Sinpeng. 2021. Opposing Democracy in the Digital Age: The Yellow Shirts in Thailand. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11666233.↩

Anderson, BOG. 2014a. Withdrawal Symptoms: Social and Cultural Aspects of the October 6 Coup. In Exploration and Irony in Studies of Siam over Forty Years, edited by Benedict R. O’G. Anderson, pp. 47–76. Ithaca, New York: Southeast Asia Program Publications, Cornell University.↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

―. 2014b. Murder and Progress in Modern Siam. In Exploration and Irony in Studies of Siam over Forty Years, edited by Benedict R. O’G. Anderson, pp. 101–115. Ithaca, New York: Southeast Asia Program Publications, Cornell University.↩

―. 2014c (first published in 1978). Studies of the Thai State: The State of Thai Studies. In Exploration and Irony in Studies of Siam over Forty Years, edited by Benedict R. O’G. Anderson, pp. 15–45. Ithaca, New York: Southeast Asia Program Publications, Cornell University.↩

Aphirak Kanchanakhongkha อภิรักษ์ กาญจนคงคา. 2014. Astani phonlajan อัศนี พลจันทร [Astani Phonlajan]. HUMAN EXCELLENCE. http://huexonline.com/knowledge/15/67/, accessed July 6, 2021.↩

Asa Kumpha อาสา คำภา. 2021. Kwaa ja khrong amnat nam: Kan khlikhlai khayai tua khong khreuakhai nai luang phaai tai patisamphan chon chan nam thai thosawat 2490–2530 กว่าจะครองอำนาจนำ: การคลี่คลายขยายตัวของเครือข่ายในหลวงภายใต้ ปฏิสัมพันธ์ชนชั้นนำไทย ทศวรรษ 2490–2530 [To achieve royal hegemony: The evolution of monarchical network in interaction with the Thai elites, BE 2490s–2530s]. Nonthaburi: Same Sky Publishing House.↩ ↩ ↩

Astani Phonlajan (Naiphi) อัศนี พลจันทร. 2014. Khwam plianplaeng, lae phak phanuak, raw chana laew mae ja lae kapklon khwam plianplaeng “ความเปลี่ยนแปลง”, และ “ภาคผนวก”, เราชะนะแล้วแม่จ๋า. และกาพย์กลอน “ความเปลี่ยนแปลง” [“Change,” and appendix, we have already won mother, and the poem “change”]. Executive Editor, Aida Arunwong, Original Editor, Naowanit Siriphatiwirat. Bangkok: Read Publishers.↩ ↩

―. 1990. Khwam plianplaeng ความเปลี่ยนแปลง [Change]. Bangkok: Kiaoklaaw-Pimpakarn.↩

Avril, Pierre and Gicquel, Jean. 2013. Lexique de droit constitutionnel [Glossary of Constitutional Law]. Paris: Presses universitaires de France. (Entry for pouvoir constituant).↩

Bagehot, Walter. 1867 (1963). The English Constitution. London: Collins.↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

Bank of Thailand ธนาคารแห่งประเทศไทย. 2014. Praden setakit nai rop pii 2557 lae naewnom pii 2558 ประเด็นเศรษฐกิจในรอบปี 2557 และแนวโน้มปี 2558 [Economic issues in 2014 and trends in 2015]. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwiTntu3-O-BAxVoe2wGHWPdBr4QFnoECAwQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.bot.or.th%2Fcontent%2Fdam%2Fbot%2Fdocuments%2Fth%2Fthai-economy%2Fthe-state-of-thai-economy%2Fannual-report%2Fannual-econ-report-th-2557.pdf&usg=AOvVaw3xGTrrK8ioAO_jfJdsOAhN&opi=89978449, accessed October 12, 2023.↩

BBC Thai. 2021. 89 pi aphiwat sayam kap kan chumnum khrang raek lang ok jak reuam cam khong kaen nam raasadon 89 ปี อภิวัฒน์สยามกับการชุมนุมครั้งแรกหลังออกจากเรือนจำของแกนนำ “ราษฎร” [89 anniversary of the Siamese revolution and the first rally after leaving prison of the “people” party’s leaders]. June 24. https://www.bbc.com/thai/thailand-57597789, accessed July 2, 2021.↩

―. 2020. Flash mob naksueksa thueng chumnum yai khong khana raasadon 2563 lamdap hetkan chumnum thang kan meuang pii 2563 แฟลชม็อบนักศึกษาถึงชุมนุมใหญ่ของ “คณะราษฎร 2563” ลำดับเหตุการณ์ชุมนุมทางการเมืองปี 2563 [Students’ flash mob to the big rally of “People’s Party 2020” timeline of political rally events 2020]. October 30. https://www.bbc.com/thai/thailand-54741254, accessed July 2, 2021.↩

Chaitawat Tulathon ชัยธวัช ตุลาธนและคณะ et al. 2012. Khwam jing pheua khwam yutitham: Hetkan lae ponkrathob cak kan salai kan chumnum mesa-phrutsaphaa ความจริงเพื่อความยุติธรรม: เหตุการณ์และผลกระทบจากการสลายการ ชุมนุมเมษา-พฤษภา 53 [Truth for justice: Events and effects of the April–May 2010 protest dispersal]. Bangkok: Information Center for people affected by the protest dispersal in April–May. February 2010, 2012.↩

Chambers, Paul and Napisa Waitoolkiat. 2016. The Resilience of Monarchised Military in Thailand. Journal of Contemporary Asia 46(3): 425–444. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2016.1161060.↩ ↩

Charnvit Kasetsiri ชาญวิทย์ เกษตรศิริ, ed. 2013. Phrutsapha-phrutsapha: Sangkhom rat-thai kap khwam runraeng thang kan meuang พฤษภา-พฤษภา: สังคม-รัฐไทยกับความรุนแรงทางการเมือง [May–May: Thai society-state and political violence]. Bangkok: Social Science and Humanities Textbook Project Foundation.↩

Collini, Stefan. 2020. Review of Liberalism at Large: The World According to the ‘Economist’ by Alexander Zevin. London Review of Books 42(3). February 6. https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v42/n03/stefan-collini/in-real-sound-stupidity-the-english-are-unrivalled, accessed July 2, 2021.↩

Fowler, H. W. et al., eds. 1995. The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Current English. Oxford: Clarendon Press.↩

Hathaikan Treesuwan หทัยกาญจน์ ตรีสุวรรณ. 2019. Ratthamanuun 2560: Witsanu-michai law thi maa meua rang rattamun chabab disain ma pheua phuak raw รัฐธรรมนูญ 2560: วิษณุ-มีชัย เล่าที่มามือร่างรัฐธรรมนูญฉบับ “ดีไซน์มาเพื่อพวกเรา” [The 2017 Constitution: Witsanu-Meechai tells the source of the draft constitution designed for us]. BBC Thai. December 8. https://www.bbc.com/thai/thailand-50703356, accessed July 1, 2021.↩

Kamnoon Sidhisamarn คำนูณ สิทธิสมาน. 2006. Prakot kan sonthi: Cak seua si leuang thueng phaa phankhaw si fa ปรากฏการณ์สนธิ: จากเสื้อสีเหลืองถึงผ้าพันคอสีฟ้า [The Sondhi phenomenon: From yellow shirts to blue scarves]. Bangkok: Ban Phra Athit Publishing.↩

―. 2005. Phra racha amnat nai mum mong khong nakwichakan พระราชอำนาจในมุมมองของนักวิชาการ [Royal prerogatives in the view of scholars]. MGR Online. August 29. https://mgronline.com/daily/detail/9480000117067, accessed July 21, 2021.↩

Kanokrat Lertchusakul กนกรัตน์ เลิศชูสกุล. 2020. Cak muetop thueng nok wit: Phattanakaan lae phonwat khong khabuankaan tawtan thaksin จากมือตบถึงนกหวีด: พัฒนาการและ พลวัตของขบวนการต่อต้านทักษิณ [From clappers to whistles: Development and dynamics of the anti-Thaksin movement]. Bangkok: TRF & Illuminations Editions.↩

Kanokwan Peamsuwansiri กนกวรรณ เปี่ยมสุวรรณศิริ. 2021. Kamnoet lae botbat khong sathanii withayu siang prachachon haeng prathet thai nai thana khabuankaan totan rat khong kulab saipradit lae pannyachon fai sai rawang pi p.s. 2505–2517 กําเนิดและบทบาทของสถานีวิทยุเสียงประชาชนแห่งประเทศไทย (สปท.) ในฐานะขบวนการต่อต้านรัฐของ กุหลาบ สายประดิษฐ์ และปัญญาชนฝ่ายซ้าย ระหว่างปี พ.ศ. 2505–2517 [The origins and roles of the people’s voice of Thailand radio station as an anti-state movement of Kularb Saipradit and left-wing intellectuals during 1962–1974]. Draft Chapter of a Masters Thesis. Faculty of Political Science Thammasat University.↩

Kasian Tejapira เกษียร เตชะพีระ. 2017. Phumithat mai thang kan meuang ภูมิทัศน์ใหม่ทางการเมือง [A new political landscape]. Matichon Weekly. June 17. https://www.matichonweekly.com/column/article_42308, accessed July 21, 2021.↩ ↩

―. 2016. The Irony of Democratization and the Decline of Royal Hegemony in Thailand. Southeast Asian Studies 5(2): 219–237. https://doi.org/10.20495/seas.5.2_219.↩ ↩

―. 2008. Thang phraeng lae phongnam: Thang phan su prachathipatai thai ทางแพร่งและพงหนาม: ทางผ่านสู่ประชาธิปไตยไทย [Crossroads and thickets: Passageway to Thai democracy]. Bangkok: Matichon Publishing House.↩

―. 2001. Commodifying Marxism: The Formation of Modern Thai Radical Culture, 1927–1958. Kyoto: Kyoto University Press; Melbourne: Trans Pacific Press.↩

Kasikorn Research Center ศูนย์วิจัยกสิกรไทย. 2008. Pit Suwannaphum . . . sankhlon khwamcheuaman to kan pen sunklang thurakit nai phumiphak lae at tong chai weelaa nan kwa ja fuen khuen ปิด สุวรรณภูมิ . . . สั่นคลอนความเชื่อมั่นต่อการเป็นศูนย์กลางธุรกิจในภูมิภาค และอาจต้องใช้เวลานานกว่าจะฟื้นคืน (กระแสทรรศน์ ฉบับที่ 2119) [Shutting down Suvarnabhumi . . . confidence as a business center in the region shaken and may take a long time to recover (Current Issue No. 2119)]. December 1, 2008. https://www.kasikornresearch.com/th/analysis/k-econ/economy/Pages/17912.aspx, accessed July 21, 2021.↩

Kullada Kesboonchoo Mead. 2004. The Rise and Decline of Thai Absolutism. London and New York: Routledge.↩

Matichon Weekly. 2017. Yon pum si thahaan seua khana raasadon sahai ruam aphiwat roiraaw khwaam phaiphae ย้อนปูม “สี่ทหารเสือคณะราษฎร” สหายร่วมอภิวัฒน์-รอยร้าว-ความพ่ายแพ้ [Tale of “the People Party’s four musketeers” revolutionary comrade-in-arms, divisions, and defeat]. June 24. https://www.matichonweekly.com/scoop/article_41978, accessed July 21, 2021.↩

Mérieau, Eugénie. 2016. Thailand’s Deep State, Royal Power and the Constitutional Court (1997–2015). Journal of Contemporary Asia 46(3): 445–466. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2016.1151917.↩

Move Forward Party พรรคก้าวไกล. 2021. Pokpong prachathipatai totan phadetcakan amnatniyom sonburanayasit ปกป้องประชาธิปไตย ต่อต้านเผด็จการอำนาจนิยมสมบูรณาญาสิทธิ์ [In defense of democracy against absolutist authoritarian dictatorship]. March 25. Facebook Post. https://www.facebook.com/MoveForwardPartyThailand/posts/285124786452882/, accessed July 21, 2021.↩

Nakharin Mektrairat นครินทร์ เมฆไตรรัตน์. 2006. Karani ram 7 songsala rachasombat kan tikhwam lae kan santo khwammai thang kan meuang กรณี ร. 7 ทรงสละราชสมบัติ: การตีความและการสานต่อความหมายทาง การเมือง [The case of King Rama VII’s abdication: Interpretation and continuation of political meaning]. Bangkok: Torch Publishing Project and the Research Fund Office.↩

Naowanit Siriphatiwirat เนาวนิจ สิริผาติวิรัตน์. 2014. Maaihet cak samnak phim หมายเหตุจากสำนักพิมพ์ [Notes from the publisher]. In Khwam plianplaeng, lae phak phanuak, raw chana laew mae ca lae kapklon khwam plianplaeng ความเปลี่ยนแปลง, และ “ภาคผนวก”, เราชะนะแล้วแม่จ๋า. และกาพย์กลอน “ความเปลี่ยนแปลง [“Change,” and appendix, we have already won mother, and the poem “change”], edited by Astani Phonlajan อัศนี พลจันทร, pp. 67–118. Bangkok: Read Publishers.↩

Naowarat Pongpaiboon เนาวรัตน์ พงษ์ไพบูลย์. 1990. Khamnam คำนำ [Forward]. In Khwam plianplaeng ความเปลี่ยนแปลง [Change] by Naiphi (Astani Phonlajan). Bangkok: Kiawklaw-Phimpakaan.↩

Nattapoll Chaiching ณัฐพล ใจจริง. 2012. Sayam bon thang song phraeng: 1 satawat khong khwam phayayam patiwat RS 130 สยามบน “ทางสองแพร่ง”: 1 ศตวรรษของความพยายามปฏิวัติ ร.ศ. 130 [Siam at “a crossroads”: A century of revolutionary efforts, 130 RS]. Silapa wattanatham ศิลปวัฒนธรรม [Arts and culture] 33(4) (February): 76–94.↩

Nidhi Aeusrivongse นิธิ เอียวศรีวงศ์. 2019. Na mai khong prawattisat หน้าใหม่ของประวัติศาสตร์ [A new page in history]. Prachatai. September 29. https://prachatai.com/journal/2019/09/84547, accessed July 21, 2021.↩

Oxford Paperback Encyclopedia. 1998. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.↩

Phimmasone Michael Rattanasengchanh. 2012. Thailand’s Second Triumvirate: Sarit Thanarat and the Military, King Bhumibol Adulyadej and the Monarchy and the United States. 1957–1963. Unpublished Masters Thesis, University of Washington.↩

Positioning Magazine. 2009. Hetkaan runraeng chuang songkran kranam sam thong thiaw pii 52 . . . thoy lang pay 5 pii เหตุการณ์รุนแรงช่วงสงกรานต์ กระหน่ำซ้ำท่องเที่ยวปี’ 52 . . . ถอยหลังไป 5 ปี [Violent incidents during the Songkran period: The 2009 tourism thrashed again . . . sliding back 5 years]. April 27. https://positioningmag.com/47468, accessed July 21, 2021.↩

Prachachart Business Online ประชาชาติธุรกิจออนไลน์. 2020. Thurakit rarchaprasong uam mob tangchat kum khamap chalaw longthun ธุรกิจราชประสงค์อ่วมม็อบ ต่างชาติกุมขมับชะลอลงทุน [Ratchaprasong business overwhelmed by the mob, foreigners slow down investment]. October 17. https://www.prachachat.net/economy/news-539209, accessed July 21, 2021.↩

Prachatai English. 2015. France Grants Refugee Status to Thai Political Exiles. June 27. https://prachatai.com/english/node/5213, accessed July 21, 2021.↩

Prajak Kongkirati and Veerayooth Kanchoochat. 2018. The Prayuth Regime: Embedded Military and Hierarchical Capitalism in Thailand. TRaNS: Trans-Regional and -National Studies of Southeast Asia 6(2): 279–305. https://doi.org/10.1017/trn.2018.4.↩

Pridi Banomyong ปรีดี พนมยงค์. 1992. Cong phithak cetanarom prachathipatai sombun khong wirachon 14 tulakhom จงพิทักษ์เจตนารมณ์ประชาธิปไตยสมบูรณ์ของวีรชน 14 ตุลาคม [Defend the spirit of complete democracy of the heroes of October 14th]. In Naew khwamkhit prachathipatai khong pridi phanomyong แนวความคิดประชาธิปไตยของปรีดี พนมยงค์ [Pridi Banomyong’s idea of democracy], edited by Waanee Phanomyong-Saaipradit วาณี พนมยงค์-สายประดิษฐ์, pp. 171–195. Bangkok: Pridi Banomyong Foundation and the 60th Anniversary of Democracy Project.↩ ↩ ↩

Royal Institute. 2011. Phocananukrom chabab rachabandit sathan BE 2554 พจนานุกรมฉบับราชบัณฑิตยสถาน พ.ศ. 2554 [Royal Institute dictionary 2011]. https://dictionary.orst.go.th/, accessed December 22, 2022.↩

Saiyud Kerdphol. 1986. The Struggle for Thailand: Counter-Insurgency 1965–1985. Bangkok: S. Research Center Col, Ltd.↩

Sathian Janthimathorn เสถียร จันทิมาธร. 1982. Saithan wannakam pheua chiwit khong thai สายธารวรรณกรรมเพื่อชีวิตของไทย [The current of Thai literature for life]. Bangkok: Chao Phraya Publishing House.↩

Silpa-mag.com. 2021. Anuson ngansop khana “kek meng” sayam RS130 itkon raek prachathipatai thai 130 อนุสรณ์งานศพคณะ ‘เก๊กเหม็ง’ สยาม ร.ศ. อิฐก้อนแรกประชาธิปไตยไทย [Cremation volume of the “Kek Meng (change of regime)” Siamese RS 130, The first brick of Thai democracy]. February 15. https://www.silpa-mag.com/history/article_63104, accessed December 31, 2021.↩

Somsak Jeamteerasakul สมศักดิ์ เจียมธีรสกุล. 2001. Ram 7 sala raat: Rachamnak kan aenti khommiwnit lae 14 tula ร. 7 สละราชย์: ราชสำนัก, การแอนตี้คอมมิวนิสม์และ 14 ตุลา [King Rama VII abdicated: The Royal Court, Anti-Communism and October 14]. In Prawattisat thii pheng sang: Ruam botkhwam kiawkap karanii 14 tula lae 6 tula ประวัติศาสตร์ที่เพิ่งสร้าง: รวมบทความเกี่ยวกับกรณี 14 ตุลาและ 6 ตุลา [The invention of history: Collected articles on October 14 and October 6], pp. 9–19 Bangkok: October 6 Publishing House.↩

Sopranzetti, Claudio. 2018. Owners of the Map: Motorcycle Taxi Drivers, Mobility, and Politics in Bangkok. Oakland, California: University of California Press.↩

Sorawit Chumsri สรวิศ ชุมศรี and Arin Jiajunphong อริน เจียจันทร์พงษ์. 2007. Thot rahatcai charan phakdithanakul thot khwam prathanathibodi baep loplop ถอดรหัสใจ ‘จรัญ ภักดีธนากุล’ ถอดความ “ประธานาธิบดีแบบลับๆ” [Decoding the mind of ‘Charan Phakdithanakul’, deciphering the covert presidential system]. Matichon Daily. February 5.↩

Sujira Guptarak สุจิรา คุปตารักษ์. 1983. Wikhraw bot roikrong khong nai phi วิเคราะห์บทร้อยกรองของ ‘นายผี’ [An analysis of the poetry of ‘Naiphi’]. Unpublished Master’s Degree Thesis, Srinakharinwirot University Prasarnmit.↩

Thailand, Legal Information Service Center and Senate Liaison Unit ศูนย์บริการข้อมูลด้านกฎหมายและหน่วยประสานงานวุฒิสภา. 1991. Ratthamanuun haeng raacha aanaachak thai รัฐธรรมนูญแห่งราชอาณาจักรไทย [Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand]. Bangkok: Secretariat of the Senate.↩ ↩

Thailand, Secretariat of the Cabinet สำนักเลขาธิการคณะรัฐมนตรี. Prawat naayok ratamontri thai (PS 2475–pajjuban) ประวัตินายกรัฐมนตรีไทย (พ.ศ. 2475–ปัจจุบัน) [Biographies of the Prime Ministers of Thailand (1932–present)]. https://www.soc.go.th/?page_id=182, accessed July 1, 2021.↩

Thailand, Secretariat of the House of Representatives สำนักงานเลขาธิการสภาผู้แทนราษฎร สำนักรายงานการประชุมและชวเลข. 2007. Raingan kan prachum khana kammathikan yokrang ratthamanuun khrangthi 39 wanthi 7 mithunaayon 2550 รายงานการประชุมคณะ กรรมาธิการยกร่างรัฐธรรมนูญ ครั้งที่ 39/วันที่ 7 มิถุนายน 2550 [Minutes of the Meeting of the Constitution Drafting Commission No. 39/7 June 2007]. Bangkok: The Secretariat of the House of Representatives.↩

The Economist. 2019. A New Biography of Walter Bagehot, “the Greatest Victorian” and The Economist’s Greatest Editor. The Economist. August 8. https://www.economist.com/books-and-arts/2019/08/08/a-new-biography-of-walter-bagehot-the-greatest-victorian, accessed July 21, 2021.↩

Thongchai Winichakul. 2016. Thailand’s Hyper-Royalism: Its Past Success and Present Predicament. Singapore: ISEAS Yusof Ishak Institute.↩

Tongthong Chandransu ธงทอง จันทรางศุ. 2005. Phrarachamnat khong phramahakasat nai thang kotmai rattamanuun พระราชอำนาจของพระมหากษัตริย์ในทางกฎหมายรัฐธรรมนูญ [Royal prerogatives of the King in Constitutional Law]. Bangkok: S.C. Print and Pack Co., Ltd.↩ ↩

Toupictionnaire: Le dictionnaire de politique [Topictionary: The dictionary of politics]. Entry for Pouvoir constituant originaire. https://www.toupie.org/Dictionnaire/Pouvoir_constituant_originaire.htm, accessed July 6, 2021.↩

Uchen Chiangsen อุเชนทร์ เชียงเสน, ed. 2011. 19–19 Phap chiwit lae kan tosu khong khon seua daeng cak 19 kanya 49 thueng 19 phrutsapha 53 19-19: ภาพ ชีวิตและการต่อสู้ของคนเสื้อแดงจาก 19 กันยา 49 ถึง 19 พฤษภา 53 [Portraits, lives and struggles of Red Shirts from September 19, 2011 to May 19, 2010]. Bangkok: Same Sky.↩

United States Army Human Resources Command. Cold War Recognition Certificate Program Overview. https://www.facebook.com/profile/100064282135689/search?q=cold%20war%20certificate, accessed October 12, 2023.↩

Zawacki, Benjamin. 2017. Thailand: Shifting Ground between the US and a Rising China. London: Zed Books Ltd.↩

1) Regionally speaking, the Third Indochina War ended when Vietnam completed the withdrawal of its troops from Cambodia in 1989. Globally speaking, the US government dates the end of the Cold War as December 26, 1991, when the Soviet Union was officially dissolved. See Oxford Paperback Encyclopedia (1998: 240–241, 1259–1260, 1398–1399) and United States Army Human Resources Command (accessed October 12, 2023).

2) According to Chapter 1 General Provisions, Section 2 of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand, B.E. 2534 (1991). See Thailand, Legal Information Service Center and Senate Liaison Unit (1991).

3) See Thailand, Secretariat of the Cabinet (accessed July 1, 2021).

4) A comparative analysis of the two coups can be found in Kasian (2016) and Prajak and Veerayooth (2018).

5) Thailand, Legal Information Service Center and Senate Liaison Unit (1991). The final version was drafted by the Constitution Drafting Commission chaired by Mr. Meechai Ruchuphan (see list of Constitution Drafting Commission at https://cdc.parliament.go.th/draftconstitution2/committee_list.php, accessed July 1, 2021). The draft constitution of the constitutional drafting commission under Dr. Bowonsak Uwanno’s presidency was not approved by the National Reform Council, reflecting how difficult it was to make the constitution “fit” with the political situation (for Constitution Drafting Commission, “List of Commissioners,” see https://cdc.parliament.go.th/draftconstitution/committee_list.php, accessed July 1, 2021; Hathaikan [2019]).

6) See Aim (2021); Kanokrat (2020); Uchen (2011, 9–19); Sopranzetti (2018); BBC Thai (October 30, 2020; June 24, 2021).

7) Chaitawat et al. (2012). For various assessments of the economic damage caused by the protracted political conflict during the past 15 years or so, see for example, Kasikorn Research Center (2008); Positioning Magazine (2009); Bank of Thailand (2014); Prachachart Business Online (2020).

8) See Thailand, Secretariat of the House of Representatives (2007). As for the “Thaksin regime,” see Kasian (2008, 89–164). Prior to this, Jaran gave several interviews to the press that expressed similar views. See for example Sorawit and Arin (2007).

9) I first presented this line of argumentation in Kasian (2017).

10) On the royal power to receive a government report and offer consultation, see Tongthong (2005, 137–52).

11) Based on the discussion by R.H.S. Crossman in Bagehot (1963 edition, 14–15).

12) Bagehot’s whole passage containing the term “a disguised republic” deserves to be quoted in full: “So well is our real government concealed, that if you tell a cabman to drive to ‘Downing Street,’ he most likely will never have heard of it, and will not in the least know where to take you. It is only a ‘disguised republic’ which is suited to such a being as the Englishman in such a century as the nineteenth” (Bagehot 1963, 266).

13) Ajarn and Khru are honorific addresses in Thai, meaning teacher.

14) By such benighted rightist organizations and groups as the People’s Alliance for Democracy, the Protect Siam Organization, the People’s Democratic Reform Committee, as well as the Thai Pakdee Party, and the Thai Move Institute in the present. See Thongchai (2016).

15) Astani’s bio-profile is gathered from Kasian (2001); Sujira (1983); Naowanit (2014, 67–118); Kanokwan (2021); and Aphirak (2014).

16) My interpretation is based on Naiphi’s letter dated May 10, 1980 to a young poet cited in Sathian Janthimathorn (เสถียร จันทิมาธร) (1982, 314–15); and Astani (2014, 114–15).

17) As to the enabling external dimension of the monarchy-military power nexus during the Cold War, see Zawacki (2017) and Phimmasone (2012).