Contents>> Vol. 13, No. 2

Correction

This article was published on August 22, 2024 and amended on August 28, 2024 because the earlier version misidentified Pavin Chachavalpongpun as “an exiled anti-monarchy academic” and Somsak Jeamteerasakul as “another exiled antimonarchy activist-scholar” (page 323). Both Pavin Chachavalpongpun and Somsak Jeamteerasakul are exiled pro-monarchical-reform critic scholars. A corrigendum note is published for the printed version.

Smirking against Power: Cynicism and Parody in Contemporary Thai Pro-Democracy Movement (2020–2023)

Chai Skulchokchai*

*ชัย สกุลโชคชัย, Faculty of Political and Social Sciences, Ghent University, Campus UFO – Technicum, Sint-Pietersnieuwstraat 41, Gent, 9000, Belgium; Faculty of Historical and Cultural Studies, University of Vienna, Universitätsring 1, A-1010 Vienna, Austria

e-mail: Chaiyo1999[at]gmail.com

![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5158-6422

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5158-6422

DOI: 10.20495/seas.13.2_311

The 2020–23 wave of protests in Thailand forever changed the country’s political landscape. While stemming from and inspired by the 2011 protests, its ability to undermine the hegemony of form and the eternal state of Thailand remains unmatched. People no longer act as if everything is normal but have started to acknowledge the underlying problems. Through parodies and cynicism, they expose the fragility of the eternal state. The Internet has made it easier for subversive acts to spread. To evade censorship, subversive acts use metaphorical and paradoxical parody as a tool to disguise messages as innocuous. Thailand has experienced turbulence in the past decades with the interregnum crisis. People who believed in the regime have become ta sawang (disillusioned)—but with the draconian lèsemajesté law, they have no way to voice their dissent except through cynicism and parody.

Keywords: cynicism, hegemony of form, online activism, parody, Thailand

Introduction

On August 25, 2020, the Royalist Marketplace Facebook group—a parody of the royalist movement in Thailand, with more than one million members—was ordered to be disbanded by the Thai government under the Computer Act, which deals with the dissemination of false information. The group’s founder quickly announced plans to create another Royalist Marketplace, to demonstrate that no matter how many groups were closed, another would always be set up.

It is said that dictators have no sense of humor. Academically speaking, authoritarian regimes and their variants do not tolerate humor well. The study of humor and cynicism is well developed in studies of the former Soviet bloc and came to attention again during the Arab Spring uprising, which began in 2010 (Popovic and Joksic 2013; Damir-Geilsdorf and Milich 2020). Humor is used as a tool used to degrade the opposition. However, it has not been as widely studied as the use of technology and various aspects of social cleavage in the context of Thailand’s 18-year-long political turmoil. The continued protests in Thailand since 2020 are part of a greater resistance to the authoritarian regime. Thais are not only famous for their smiles and hospitality but have also become famous for their disapproval of repression through cynical humor and satire.

Thailand was under a decades-long political crisis that many attribute to the interregnum (possibly since 2006, 2014–23) between the reigns of King Rama IX (1927–2016, r. 1946–2016) and King Rama X (b. 1952, r. 2016–present), when the royal institutions lost considerable political and cultural hegemony (Hewison 2019). To preserve the status quo, there were two coups and a civilian massacre during the 2010 Thai military crackdown (Ferrara 2019). Like Antonio Gramsci’s quote “the old is dying and the new cannot be born in this interregnum, a great variety of morbid symptoms appear,” the Thai ancien régime is deteriorating rapidly but trying to prevent the new with government suppression of public expression. During the interregnum the “morbid symptoms” showed up; and under government suppression, several people became ta sawang, or “disillusioned.” Many blamed the king or his close confidants for Thailand’s ongoing political crisis (Sopranzetti 2018). Nevertheless, people are still constrained by the state’s ironclad censorship and suppression. To circumvent the abusive litigation, they express their subversion through cynical jokes, satire, and parody. The initial widespread circulation of such acts of subversion occurred in May 2011, the first anniversary of the 2010 Thai military crackdown. Subversion became popular again in 2020, when the public reached their breaking point after eight years of dictatorship, with the help of social networks such as Twitter and Facebook. Despite the popular youth movement’s early success, it took a hiatus in late 2021 after a series of failed attempts to force the government to dissolve the parliament. The movement almost died out while this paper was being written, for reasons that will be discussed later. Therefore, it is important to understand why the movement began and what it has achieved through various theoretical lenses.

Methods and Positionality

The scale of the 2020 protest and its contribution to Thailand’s democratization is debatable. However, this work focuses on the method of resistance rather than the movement’s outcome. Most of the physical protests discussed below were chosen because I was directly involved in them as an observer and could capture the zeitgeist. As for the online cases, they were selected for the scale of reaction from the royalists. Although some of the protests discussed below were small and had minimal effect, they were selected because of their creativity. Obviously, the jokes discussed in this paper are viewed from the perspective of this author—a middle-class observer of urban demonstrations. The jokes are open to interpretation, and therefore my interpretations are not absolute. There were several social classes that participated in the demonstrations. From Kanokrat Lertchoosakul’s (2021a) research, the most popular subaltern group was Thalugaz (Breakthrough Gas). They were rather violent, using Ping-Pong bombs and firecrackers against police. Their anti-establishment tactics were not hidden behind a humorous front, which most protests were—especially during the Din Daeng Triangle clash.

Brief History of Recent Political Developments in Thailand

King Bhumibol Adulyadej the Great, or King Rama IX, was the longest-reigning monarch in Thai history. He began his reign as a symbolic leader with no real authority in the military government (Asa 2019). He then became a junior partner in successive regimes: the infamous Sarit’s despotic paternalism era and the Thanom-Praphas era (Asa 2019). Although it is debatable whether he sided with the people in the 1973 uprising against Thanom-Praphas and the 1992 Black May uprising against Suchinda Kraprayoon, he strategically positioned himself away from the military. All of this helped him consolidate power through the “Bhumibol Consensus” after the 1992 Black May uprising (Asa 2019). There was an implicit consensus in the top echelons of Thai society to consider him as the leader and adjudicator of any issues (McCargo 2005). From then on, he became the most powerful person in Thailand, being able to intervene in all affairs through his proxies, a system dubbed the “network monarchy” (McCargo 2005). By the time of the diamond jubilee (sixty years) of his reign in 2006, he owned the hegemony of form. People paid respects to His Majesty without a second thought despite the superficial value of such acts: praying at the temple on his birthday, wearing a yellow shirt on Monday (his birth day), and celebrating Father (of the Nation) Day in schools and government bureaus. On the sixtieth anniversary of his enthronement, more than 500,000 people gathered at the Royal Plaza for a royal audience (Faulder 2016). The eternal state was perfect: people believed and wished that King Rama IX’s reign would last forever, even though his health had been declining. Later in 2006, a political crisis began with the coup d’état against Thaksin Shinawatra, an elected prime minister, on the pretext of Thaksin’s corruption and a political deadlock. Before the coup, the pro-monarchy “Yellow Shirts” demanded that the king appoint a new prime minister, which was legally impossible (Pasuk and Baker 2009). The coup was ineffective because it failed to eradicate Thaksin’s influence in Thai politics, and his supporters united under the banner of the “Red Shirts” in 2007. The Thaksin-affiliated party won the next election in 2008, only to be ousted by a judicial coup through a constitutional court. Before the case came before the constitutional court, the Yellow Shirts stormed Government House and Bangkok’s two airports. In one of the clashes with police, Angkhana Radappanyawut or Nong Bo, a Yellow Shirt protester, was killed (Khorapin 2018). The queen attended her funeral, which implicitly showed that the monarchy was aligned with the pro-royal, anti-government masses (Khorapin 2018). That day, October 13, was marked as the “day of disillusionment” for many people when the event was discussed on the Fah Deaw Kan Same Sky web board (Khorapin 2018). After the judicial coup, the leader of the opposition, Abhisit Vejjajiva, took office with support from the military and some of the semi-loyal government coalition who had turned against Thaksin’s government. The Red Shirts came from the North, Northeast, and provinces around Bangkok to demand that the parliament be dissolved. Instead, Abhisit allegedly ordered a crackdown that resulted in at least 98 deaths in Bangkok (Phasuk 2020). This led many to become disillusioned with the monarch, who was apparently aware of the crackdown but chose not to intervene.

The first anniversary of the crackdown in 2011 was the first time that royal hegemony was challenged through parodies and cynicism. While no one talked about the royal family, the graffiti on a burnt building showed the people’s disillusionment. From then, Article 112 (the lèse-majesté law) became more frequently used to suppress anti-monarchy acts. This led to the development of more sophisticated methods of subversion.

Abhisit soon dissolved the parliament and called for an election. The Thaksin-affiliated party again won the election, only to be ousted by another coup in 2014 by General Prayut Chan-o-cha when the government was blamed for dividing the nation. The coup is believed to have been staged by the royalists to consolidate the succession of King Rama X or King Vajiralongkorn (Pavin 2020). Once King Rama IX passed away in 2016, the new king, Vajiralongkorn, expanded his privileges by assigning two regiments of the Royal Thai Army as his personal armed force and changing the law to allow him to reside abroad without appointing a regent (Deutsche Welle 2017; Reuters 2019). The king is known to prefer living in Germany and to have a passion for the military. Those two privileges gave him greater influence, with taxpayer money, which generated much discontent among young people (BBC 2020). After the coup leader, Prayut, called and won the 2016 general election, progressive movements continued to be repressed. The anti-military, pro-democracy Future Forward Party, which was the younger generation’s favorite during the 2016 election, was dissolved in early 2020 after being accused of violating election regulations on its source of income (BBC Thai 2020). The court ruling instigated mass protests, which were soon brought to an end by the outbreak of Covid-19. The government took advantage of the emergency to order social-distancing protocols that halted any political movements (Kurlantzick 2020). Later that year Wanchalerm Satsaksit, a pro-democracy activist-in-exile, was allegedly abducted and disappeared. The news sparked public outrage and waves of protest despite the pandemic’s emergency decree (Wright and Praithongyaem 2020). The main differences between the youth movements in 2020 and the Red Shirt movement against Abhisit in 2010 were the former’s widespread use of social networks and young age of protesters (middle school to university students). The young urban middle-class protesters in 2020 were a contrast from the “urbanised villagers” of the Red Shirts of the Thaksin era (Naruemon and McCargo 2011). The youths used creative protest tactics that may have been learned from abroad, such as pop culture, jokes, and transnational pleas, rather than physical confrontation and disruption like the Red Shirt protest—although the youths did see the Red Shirt movement as an act of heroism.

Even though King Vajiralongkorn was made crown prince in 1972, he was overshadowed by his father’s accomplishments. King Bhumibol had had ample time to create his support base before gaining real power, unlike King Vajiralongkorn, who was crowned when he was 64 years old without any prior loyal support base. King Vajiralongkorn dismissed most of his father’s advisers, replacing them with his own (Bangkok Post 2016), and although the network monarchy he inherited still functions, he has lost some support. Scandals about his mistresses have also tainted his reputation as an unflawed royal (Handley 2014). For example, his ex-consort Yuvadhida was involved in a drug trade (Handley 2014). Such incidents have dealt a blow to the king’s charisma and legitimacy. Monogamy and respect for elders are important Thai social norms. Many people who were loyal to Rama IX changed their minds about the monarchy after King Vajiralongkorn came to power. King Vajiralongkorn is trying to replace his charisma with fear based on rumors that he ordered the forced disappearance of many dissenters and his “installation of discipline” program among his semi-loyal servants (Pavin 2022).

The State of Anti-Royalism and the 2019 Wave of Protests in Thailand

Thongchai Winichakul (2014) believed that Thai society was in a state of denial about the “two elephants in the room”: the intervention of the monarchy in Thai politics and the silencing of anti-monarchy sentiment by the superstructure. Although Thai society has modernized superficially, mentally many still reside in a state of denial, refusing to see the obvious suppression of free speech. An important argument from Thongchai (2014) is the Thai belief in Dhammaracha occult (worship of the king who has the mystical power to satisfy with his good deeds). This belief elevates the king as the representation of virtue, and thus he wields absolute power over the country. The belief is still popular among older generations of Thais but is in decline among younger generations. However, this belief is one of the keys to understanding how groundbreaking the 2019 protests were, as youths refused to believe in Dhammaracha occult. Thongchai discussed the extent of hyper-royalism in Thailand: “First, it is the permeation of royalism in everyday life and the increased demand for the expression of loyalty to the monarchy. Extravagant public displays of royal symbols and platitudes are encouraged and found everywhere” (Thongchai 2019, 289). He added another crucial characteristic of hyper-royalism: exaggeration and exaltation of the king’s work and achievement, together with tight control of public discourse through a repressive state apparatus and civil society. As a result, people feel compelled to participate in insincere acts to escape the state’s wrath (Thongchai 2019).

Khorapin Phuaphansawat (2018) tracked down the ideological shifts among Thais from 2006, as early as the aftermath of the 2006 coup when the Red Shirts were formed. The Red Shirts identified themselves as phrai or commoners/serfs pitched against the ammat or aristocrats. The early target of the Red Shirts was Prem Tinsulanonda, whom they identified as the leader of the ammat. Khorapin (2017) employed Alexei Yurchak’s concepts of stiob and hegemony of form, which this paper uses too—though in a different context and time frame.

To understand the force of anti-royalism, one has to first understand the dynamics of royalism. Duncan McCargo (2005) proposed the concept of a “network monarchy” headed by the king. The network works because everyone accepts the king as the adjudicator, and the king uses his privy council members as his proxies. Eugénie Mérieau (2016) has suggested that the Thai constitutional court operates according to the monarch’s will. The court also acts as a surrogate to preserve the king’s hegemony and interests. Thus, the state does not operate on its own. It is controlled by a higher political entity—the monarchy. This phenomenon may also be referred to as the deep state.

McCargo (2021) also wrote about youth protests in Thailand. The break from previous generations is stark from their radically different understanding of how power works in Thai society. Generation Z protesters call into question taboo topics in Thai society. But McCargo concluded that Generation Z protesters do not constitute a disruptor dilemma since their impact is too insignificant to change the system. However, the people’s attitude toward the monarchy has changed. Kanokrat (2021a) interviewed 150 school students and 150 university students about their motivations for protesting. She concluded that youth protests against the education system—a part of the authoritarian institutions and influenced by the monarchy—can result in change as the goal is more reachable for youths. This conclusion might contradict the definition of Mérieau’s deep state, as Kanokrat’s (2021b) research showed that even though everyone knows about the existence of the network monarchy, the concept of the state within a state can still be applied. Even Nidhi Eawsriwong (2017) suggested that the Thai state is a “shallow state” since there is no hidden controller behind the scenes.

Theoretical Background: Cynicism and Parody

Simulation and pretense, which describes the act of make-believe, has a long history in the study of anthropology. From Karl Marx to Yurchak, the study of simulation and pretense has grown tremendously. The phenomenon is closely connected to cynicism, which refers to rationalizing beliefs to conform to one’s viewpoint—usually in the context of skepticism toward the state, in the Steinmüller sense (2014). But for Hans Steinmüller, a cynical stance intended to undermine the state is ineffective as the state can operate normally in a cynical society. Explaining such a phenomenon facilitates our understanding of how the state tolerates cynicism in private spaces and how it creates an eternal state that allows minimal change. The best description of the eternal state is Yurchak’s book title Everything Was Forever, Until It Was No More: everything appears perfect and unchangeable until people start to doubt the status quo. Sometimes an eternal state is understood in colloquial Thai as “Frozen Thailand,” which originated from a proposal in 2012 to stop all political activities for five years, maintaining the status quo while fixing problems (Apichart 2012). However, the truth is that simulation and pretense, which are not uncommon in an authoritarian state, make the state vulnerable to small and sudden changes. In the past few decades, change began with the downfall of the Soviet Union, followed by the dot-com boom and smartphones, which increased the ability of cynicism to undermine the legitimacy of the state. Although authoritarian regimes are weakened by technological progress, some authoritarian societies like North Korea are still able to maintain the eternal state by limiting freedom. Though such eternal states are believed to be forever, they are actually fragile and prone to collapse at any time, as was seen in the Arab Spring and several disruptions in Hong Kong and Thailand.

Simulation and pretense were not understood as political practices in the past, because it was believed that people could not conceal their thoughts and acts. This was the idea of rule as “total control,” as observed from Marx’s false consciousness and Gramsci’s hegemony. Marx’s false consciousness is based on the idea that the superstructure uses infrastructure to create a systematic misrepresentation of dominant social relations, to obscure the realities of subordination and exploitation (Marx and Engels 2017). Gramsci’s hegemony is about total control politically, economically, and culturally through the normalization of the dominant worldview (Wacharapon 2018). The goal is to manufacture consent among people as well as urging them to actively show their consent. Simulation and pretense were introduced as forms of political practice in James C. Scott’s (1987) Weapons of the Weak, a study on peasants in Southeast Asia. It explains the impossibility of openly and successfully opposing the dominant power given the overwhelming power advantage of the state. As a result, peasants choose to resist in quieter ways such as false compliance and foot-dragging (Scott 1987). However, this line of thinking assumes that people are resisting the system, as opposed to Marx and Gramsci’s belief in total state control. Yurchak (2003) developed an alternative to this dichotomy: His idea is that there are people who know about the problems with the system but still serve the system, actively reproducing consent while not believing in it. This contradictory performance may be observed through many examples, such as a student who preaches about the decadence of the West in public but enjoys rock music in private without seeing the contradiction. Thus, Yurchak’s idea goes beyond simulation and pretense, which actors are conscious of doing, to the realm of the subconscious. The realm of the subconscious is why simulation and pretense is related to hegemony—it is about ingrained habits. Yet the paradox is that the actors, despite knowing the problem, still follow ingrained habits (Sloterdijk 1987, cited in Steinmüller 2014). Hence, simulation and pretense is also about hegemony of form (of practice). Actions are performed not only for their face value but also for practical reasons (Steinmüller 2010). Thus, we see different states of simulation and pretense—from their absence to their being used as weapons of the weak and part of the hegemony of form.

Over time simulation and pretense developed into cynicism—a distrust of the system, making fun of it, and looking down on it. Nevertheless, passive aggression is feeble in the eyes of the state, and the fear of social sanction still outweighs people’s intention to go against the system. The base arguments for cynicism and Weapons of the Weak are different. Weapons of the Weak views every action as resistance, while cynicism views action as a well-calculated habit focusing on the trade-off if people do not comply with the state, which they are very dependent on (Steinmüller 2010).

Simulation and pretense, hegemony of form, and cynicism show that there can be discrepancies between thoughts and actions. These are coping mechanisms often found in authoritarian regimes (Navaro-Yashin 2002; Yurchak 2003; Steinmüller 2015). People do what they have to, from attending meetings and passing meaningless resolutions to attending their leader’s funeral pretending to cry (Mbembe 1992; Yurchak 2003; 2013). Such actions become routine, as the government constantly directs people to join state ceremonies such as national days and parades (Mbembe 1992; Yurchak 2013). Nationalism may even become banal when people unconsciously perform patriotic gestures in daily life (Billig 1999). Such acts are pushed by the state to condition the people according to its own agenda.

The hyper-royalism in Thailand parallels what happened in late socialism in the Soviet bloc in the 1960s–1980s (Yurchak 2013). Constant public expressions of loyalty became meaningless acts performed in order to avoid public sanction. Exaggeration and exaltation were used to portray the leader as perfect. Such obligations do not come from state sanctions alone. Although Thailand has laws on royal defamation (Article 112) and sedition (Article 116) that foster a climate of fear, the conservative civil society also contributes by suppressing critics of the monarchy. Thus, the country fits in with Yurchak’s (2013) condition of the hegemony of form. On the other hand, gossip about royalty is widespread in Thailand. The conclusion is that hegemony of form is about culture as well as totalitarianism.

As mentioned above, simulation and pretense are especially important in modern life. Cynics use pretense and simulation to evade censure (Sloterdijk 1987, cited in Steinmüller 2014)—not due to fear but due to common sense, since not participating in performative acts could take a toll on their social status. Achille Mbembe (1992) suggests that participating in public events such as oath-taking and medal ceremonies is necessary for individuals to have a respectable social status regardless of their beliefs. Lisa Wedeen (1998) suggests it is important for people to act “as if” they believe in something even if they are skeptical. She gives the example of a soldier in Syria who defied his superior officer by talking about his dream, which was different from the other soldiers’ dreams. By giving an alternative interpretation, he also stopped demonstrating active consent to the state’s absolute control. His not having the same dream as the others was a crime worthy of punishment despite its triviality. This case study shows there can be serious consequences for defiance, which makes most people choose to do nothing despite questioning the system. Acts of defiance like the soldier’s matter, because language can be used to create social change. Hollow actions may be founded on cynicism, but scripted words burrowed within conversations hold power in real life. People act with cynicism but speak as if they believe the official narrative. Repetitive dialogue can generate even more state control. Hence, performativity is a state tool to fabricate a reality in people’s minds, while cynicism creates a small safe space for people to express their doubts.

Parodying and joking is a tool for expressing cynicism. Since it can be taken lightly, it is what the state fears most—it can spread quickly and undermine the state’s legitimacy in a short time. Since language can affect our worldview, the use of parody can alter perceptions. As a result, when the hegemon becomes an object of absurdity, it is easier to undermine its legitimacy.

Hegemony of Form at Its Finest

Thailand’s hegemony was consolidated after May 1992 by the “Bhumibol Consensus” with the support of the ruling elites (McCargo 2005). The hegemony of form has been developed ever since. From 2006 it became normalized for everyone to wear a yellow shirt on Mondays to celebrate the king’s birth day. The “sufficiency economy” philosophy credited to the late King Bhumibol became both state policy and practice by the people. Irrespective of social class, this economic principle was supposed to be a part of every individual’s spending practices—though in reality it was not that common. During the mourning period for King Rama IX in 2016, those not wearing black faced public shame and risked physical abuse (Masina 2016). Discussions about the appropriateness of the lèse-majesté law have always been taboo as they show disrespect for the king, an indication of how ingrained the hegemony of form is in Thailand.

King Rama X ascended to the throne in December 2016. He is alleged to be a playboy with many mistresses whom he mistreats (Economist 2019). This rumor has fostered cynicism, as the king having mistresses goes against Thai as well as modern ethics. However, disapproval is expressed mostly in private, with inside jokes like “I have only one father” (which means only my biological father is my true father, not the king—the national father) or “When is Mother’s Day again?” (Since Thailand’s Mother’s Day is on “the queen’s” birthday, this joke implies that the current king has more than one queen). The traditional role of the king is to be a respected, paternal figure. However, since King Rama X’s promiscuous lifestyle does not foster such an image, increasing doubts are cast on his royal status and legitimacy. Nevertheless, the public continued to praise the new king until the youth protests of 2020 (McCargo 2021). At the beginning of King Rama X’s reign everyone performed the traditional rituals, such as standing up when the royal anthem was played in cinemas and calling him a father figure. Change came with the student movement in 2020, which called for a reform of the monarchy. The Internet played a major role in the protests. A video titled “A Clip at the Pool,” widely circulated on YouTube and Twitter, allegedly depicted the former royal consort, Srirasmi, celebrating the king’s dog’s birthday wearing only a G-string (Ramboisan4somchai 2011). Rumors about this were already circulating, but things came into the open with the video. Images of the king’s maltreatment of his mistress and his former princess also came to light, generating even more cynicism. However, no one was prepared for the magnitude of the 2020 protests.

The First Instance of the Great Subversion

Following the crackdown on the Red Shirt protest in 2010, the Thai government organized a “Big Cleaning Day,” which would remove all the evidence of state crime (Cod 2020). The political situation stabilized the following year. The first anniversary of the crackdown in 2011 drew large crowds even though the Red Shirts were still viewed as the enemy of the people. To everyone’s surprise, the ruins of the Central World department store were found to have been decorated with anti-monarchy graffiti, the most prominent of which showed Hitler blinded in one eye with the caption “The blind who cannot smile”—a reference to King Rama IX being blind in one eye and one of his biographies being titled The King Never Smiles (Ünaldi 2016). It directly accused the king of having ordered the violent crackdown. Many messages in the graffiti were about King Rama IX’s sufficiency economy, such as “Tha di jing prathet charoen kwa ni” (If that was done, our country would be thriving) and “Mi pen lan, tae hai ku phophiang” (You have millions [of baht] but still made us stingy) (Ünaldi 2016). Such messages challenged the notion that a sufficiency economy was the universal solution to problems and highlighted the king’s status as the world’s richest monarch—a fact often disregarded by citizens due to the humble way in which he was represented. Another message in the graffiti was the widely circulated term krasun praratchatan (royally given bullet). This too implied that the crackdown was an order from the king (Ünaldi 2016).

At the Ratchaprasong intersection during the first anniversary of the 2010 Red Shirt massacre, an unknown individual put up a banner saying “Gu mai roo gu puey” (I don’t know, I am sick) (Somsak 2011). “Gu mai roo gu mao” (I don’t know, I was drunk) is a common excuse for denying responsibility for acts committed while someone is drunk. It is connected to “Yaa tue kon baa, yaa waa kon mao” (Do not hold grudges against crazy people, and do not judge drunk people), which is a way to lessen the accountability of those whose senses are compromised. In a similar vein, being sick should exempt one from blame. At the time, King Rama IX was hospitalized. On that pretext, he should have been exempted from responsibility for his inaction. According to traditional beliefs, all Thais are children of the king, and a father should not abandon his own in the face of harm. Nevertheless, it is possible that the king chose not to prevent the 2010 massacre, like on October 6, 1976, when more than one hundred Thammasat University students were massacred.

The Faiyen band released their first album in 2011, just before the first commemoration of the crackdown. They had released their songs earlier but became more popular after the crackdown. Their most famous song is Loong Somchai, Pa Somchit (Uncle Somchai and Aunt Somchit), a parody of the Thai monarch. Somchai and Somchit are common names in Thailand (Khorapin 2017). The song tells the story of a broken family: the son and daughter’s failing relationship, the aunt’s gambling addiction and financial mismanagement, and the uncle’s hospitalization. This greatly resembled the state of the royal family. Another song, Ngua Yod Deaw (Single drop of sweat), parodies the famous photo of King Bhumibol perspiring while commanding officials during a tour to “develop” Thailand. Via the photo, the song deromanticizes King Bhumibol’s role in helping the country. The lyrics instead give credit to the farmer who does the actual work, implying that the king should not claim the country as his. The song exposes the glorification of the king’s image as meaningless. Faiyen’s most radical song is Krai Ka Ror 8 (Who killed King Rama VIII?). This touches on the taboo subject of who killed King Rama VIII. It mentions the questions being asked, with no one able to give a definite answer, and ends with a young boy replying—but only a bleat comes out, suggesting that the supposed murderers were scapegoats. The death of King Rama VIII was mysterious and the investigations inconclusive. Three of his aides-de-camp were blamed and sentenced to death. However, many suspect that the murderer was King Rama IX (King 2011). Once people became brave enough to discuss this sensitive subject, the long-lived legitimacy of King Rama IX was finally challenged.

From 2006 to 2020, many activists-in-exile set up channels on YouTube or posted commentaries on Same Sky web boards such as Lung Sanam Luang, DJ Soonho, and Chuphong Theethuan. These commentaries were about gossip from the palace. “Canned Fish Factory” by “Grandma Hi” is another example of gossip and subversion preparing Thais for change. There were 199 weekly online publications of this story, which does contain some facts, from 2009 on a Same Sky web board narrating the situation of the royal family (Sirimalee 2022). After the 2014 coup, many of the activists-in-exile were allegedly forced disappeared. Their sound bites, however, survived and enjoyed greater popularity during the 2020 wave of protests, which prompted more young people to question the royal institution.

Online and Real-Life Subversion

In 2011 social media was not as widely used as in 2020. Most of the protesters in 2011 were also of a different generation (Generation X or Y). During the early stages of the Covid-19 pandemic, protesters came to fear the state of emergency. With widespread layoffs, the unemployed turned to freelancing and selling products online. One way to expand target customers was through educational networks. For example, Chula Marketplace was a trendy Facebook group for Chulalongkorn University alumni, students, and staff to sell their products. Later, Pavin Chachavalpongpun, an exiled pro-monarchical-reform academic, created another similarly named Facebook group—Royalist Marketplace—to mock the trend of marketplaces. Contrary to what its name suggests, Royalist Marketplace does not advocate for royal privilege. It is a discussion board for Pavin’s followers, democracy sympathizers, and more radical republicans (Schaffar 2021). The group became a safe space to criticize and make fun of the monarchy. With increasing discontent over the expansion of royal privilege and government mismanagement, more people joined the group and it grew to over two million members, making it one of the world’s largest Facebook groups. The name “Royalist Marketplace” cannot be taken at face value as the group sells nothing; its name is a mask for ridiculing the monarchy. This became one of the biggest inside jokes in Thailand. Pavin was given the mock royal name Somdej Phra Nangjao Pavinsuda Phraphanpee Luang (Queen Dowager Pavinsuda) and a royal coat of arms. Somsak Jeamteerasakul, another exiled pro-monarchical-reform critic activist-scholar, was given the title Somdej Phra Jeamklao Chao Yuu Hua (King Jeam) as can be observed in Fig. 1.

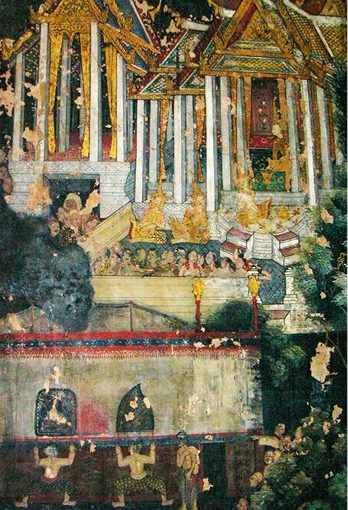

Fig. 1 A Banner from the #ThammasatWillNotTolerate Protest on August 10, 2020 Projects the Image of Pavin and Somsak against a Gold Background, Usually Reserved for the Royal Family. Pavin and Somsak Also Have Their Coat of Arms. The Writing on the Banner Is “Duay Kao Duay Kang-om Moo Krata” (With Rice, Curry, and Pork Barbecue), a Parody of “Duay Klao Duay Kramom Kor Decha” (With the Top of My Forehead Paying Respects).

Source: Prachatai (2020)

On Twitter, hashtags can intensify public opinion. Hashtags such as #WhyDoWeNeedAKing were used more than 1.2 million times in 24 hours on March 21–22, 2020, showing the public’s attitude toward the king’s abandoning the country during the Covid-19 pandemic (Reuters 2020). Hashtags such as #RoyalMotorcade and #IslandShutdown also showed the people’s discontent with the monarchy: #RoyalMotorcade was a complaint about unplanned road closures causing traffic disruptions just because a member of the royal family wanted to travel. Another role of hashtags, together with the Facebook group, was to rally people to protest. Hashtags such as #15OctoberGoToRatchaprasong—to display protesters’ strength through numbers—reached 68,000 posts within minutes on October 15, 2020 (Cod 2020).

However, online subversion alone was not enough to bring about regime change; real-life mobilization was needed. From the Royalist Marketplace banner to the image of Pavin in royal uniform, there were frequent signs of resistance at gatherings and political events—even at Thammasat University’s graduation ceremony, which was attended by the king. Anti-monarchists gave Pavin the title of queen dowager, ranked above Queen Suthida and Royal Consort Sineenat.

The power of hashtag activism transformed tweets into real-life activism. Two instances will be discussed here: the mobilization of #CastPatronusCharmProtectingDemocracy and People’s Runway. The first hashtag event was inspired by the iconic Patronus Charm from the Harry Potter franchise. The charm was used against “He Who Must Not Be Named,” an alias of “Lord Voldemort.” Lord Voldemort was none other than the monarch, whose name cannot be uttered in a negative way. The creative theme represented the younger generation who participated in this protest. Not long after that, People’s Runway was organized on Silom Road, Bangkok’s financial hub. Intended to mock the lavish spending of Princess Sirivannavari on her fashion brand and runway events, the event took place on the same day as the release of the princess’s new winter collection. Its iconic photo portrayed a woman in Thai national costume walking on a red carpet, similar to Queen Suthida walking to the Grand Palace, while the king described Thailand as the “Land of Compromise.” Traditionally, Thai national costumes were designed and promoted by Queen Dowager Sirikit. Wearing them symbolized loyalty to the monarchy. On the surface, People’s Runway demonstrated loyalty, but its true intent was to mock Queen Suthida and Princess Sirivannavari. Both cases show how protesters avoided directly calling out the monarchy, instead doing so under the guise of a fictional character or a show of loyalty. Although the People’s Runway leader was charged under Article 112, the district court put aside the matter by claiming that it fell under the criminal court’s jurisdiction (Anonymous 2022a). However, the person dressed as Queen Suthida was sentenced to two years in prison (Anonymous 2022b).

Another example of subversion by innuendo is the “Mom Dew Diary” Facebook page. Mom Dew is a transgender woman who looks like Queen Dowager Sirikit. Using the word “Mom” (The Honorable) to pretend she has royal lineage, she imitates the way Queen Dowager Sirikit talks and dresses. Her cover photo shows her aiming a gun in a shooting range, similar to a famous photo of Queen Dowager Sirikit. She often visits places with her attendant to support (democratically aligned) people. Traditionally, wearing a royal-designed Thai dress signifies that one is upholding national values, which include loyalty to the monarch. Parodying acts of patriotism and Queen Dowager Sirikit has become one of Mom Dew’s most iconic aspects. In late 2022 she started a TV program called News from Mom Dew Page, a parody of News from the Palace, which is broadcast every day at 8 a.m. With a marching song and a news anchor’s voice reading the introduction, it is similar to News from the Palace.

Parit Chiwarak, one of the leaders of the resistance, wore a crop top (inspired by a photo of the king in Munich) to Siam Paragon, which is partly owned by King Rama X’s sister Princess Sirindhorn, to mock the king by copying his infamous fashion choices. He was immediately charged under the lèse-majesté law. In another case, he performed a Choi song in public under the alias of “Khai Nui.”1) The lyrics were about two women fighting over a man. Viewers could immediately recognize that Khai Nui was a parodic version of Queen Suthida, as her nickname is Nui and the dress Parit wore was very obvious. The fight between Queen Suthida and Royal Consort Sineenart is a topic of gossip among Thai people, but previously no one vocalized it.

The Royalist Reasons

Before the protests started, Pavin and Somsak, together with many academics and activists, were labeled as “nation haters” for wanting to abolish the monarchy. Many of them, including Pavin, explained that they were also “royalists” who cared, that they wanted to transform the monarchy to make it more resilient to change and adapt to the present-day world. They by no means wanted a republican Thailand. Therefore, Royalist Marketplace may not be a parody but indeed a genuine effort to improve the monarchy by pointing out its weaknesses.

Transnational Parodies

In 2020, at the peak of the youth protest, an insignificant Twitter post showing cityscapes from Hong Kong, Japan, Singapore, and Thailand and referring to Hong Kong as a country sparked a Twitter war between China and Thailand. The person who posted was the girlfriend of a Thai actor who had Chinese audiences. The actor retweeted the post, which led to his Chinese audience demanding that he apologize for calling Hong Kong a country rather than a territory (Buchanan 2020). Soon after, Chinese Twitter trolls joined in and a Twitter war erupted. Many Chinese trolls tweeted derogatory statements about Thailand, such as “The Thai government sucks” and “Your king is ugly.” They found that Thai young adults already hated their government and questioned their king. As a result, not only did the Chinese Twitter trolls fail to insult Thais, but Thai Twitter accounts used the Chinese trolls’ posts to criticize Thailand instead—something that confused even the angry Chinese. This roundabout criticism helped the Thais to avoid risking jail time of three to 15 years.

Some Thais countered Chinese trolls with memes undermining Chinese cultural hegemony by pointing out its oppressive nature. By mentioning the Tiananmen Square massacre and Winnie the Pooh, Thais put Chinese trolls in an uncomfortable situation, since such references are heavily censored in China. The adverse outcome for China from this Twitter war was pan-Asian solidarity against China’s authoritarianism and in favor of democracy. The Milk Tea Alliance was formed by Thais, Hongkongers, and Taiwanese, followed by people from the Philippines, Malaysia, Singapore, and India as a coalition for democracy (Barron 2020; Salam 2022). This greatly benefited the Thai youth movement as its democratic agenda gained international publicity. The practice of Thais taking the help of foreigners to question their own country became so normalized that a Malaysian model even asked Thais to roast the Malaysian government in exchange for Malaysians roasting the Thai monarchy—a way for both sides to avoid getting into legal trouble observable in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2 This Post Illustrates Transnational Cooperation between Thais and Indonesians in Criticizing Each Other’s Government to Avoid Being Prosecuted.

Source: @_nsyakinah (2022)

The Change

“No God, No King, Only Human,” a quote from the BioShock video games, was displayed on Ratchaprasong SkyWalk during the 2020 protests and chanted by young protesters at the Pathumwan intersection. It indicated the people’s loss of faith in religion and the king as an agent of positive change. Parody and cynicism weaken authoritarian regimes by exposing their flaws and mocking them under the guise of loyalty. Though it is not sufficient to topple a regime, satire can increase the cost of repression to a point that it is no longer worth the trouble, which may prompt a regime to reconsider its position. Demonstrations in Thailand have led to tremendous changes. People are bolder in speaking about the royal family in public, and reverence for the monarch has decreased. One example is discussions on the amendment and appropriateness of Article 112, previously a taboo topic, which every political party discussed openly during the 2023 election. Royal sayings became something to mock and change, such as “Duay klao duay kramom kor decha” (With the top of my forehead paying respects) to “Duay kao duay kang-om moo krata” (With rice, curry, and pork barbecue). An abbreviation of SPCR, or “Song phra charoen” (May the monarch prosper), was trivialized to “Thappee cha rueng” (The rice paddle is falling).

The decreased reverence for the monarch is not merely superficial. Every graduation ceremony in Thailand is traditionally presided over by a member of the royal family. This is one of the few chances to get close to royalty in Thailand and usually counts as an opportunity of a lifetime. However, after King Rama IX died, fewer students began attending graduation ceremonies. The number dropped further after the start of the youth movement, with campaigns urging people not to attend. The Thammasat University graduation ceremony is always presided over by the king. In 2020, of the 7,756 graduating students only 3,280—or 42.29 percent—attended the graduation rehearsal, a requirement for attending the main ceremony (Isranews 2020). Attendance had already fallen from 70 percent to 50 percent in prior years, reflecting the monarch’s drop in popularity among the younger generation (Isranews 2020). Instead, people printed out life-size models of three academics-in-exile—Pavin, Somsak, and Puey Ungphakorn—dressed as royals and received their degrees from the models instead as can be observable Fig. 3.

Fig. 3 Life-Size Printout of Highly Respected People from Thammasat University on the Occasion of the 2020 Graduation Ceremony

Source: Freetupandit (2020)

Many businesses joined in the protests to boost their sales, demonstrating that the younger generations are now the target audiences of businesses. In 2022 Thai Vietjet Air announced an April Fool’s promotion of a flight from Nan Province to Munich for 1,010 baht, reflecting the country’s ten reigns (ManagerOnline 2022). Nan is the birthplace of Royal Consort Sineenart, and Munich is the king’s favorite luxury vacation destination. Lazada, one of Thailand’s largest e-commerce platforms, issued a May 5 or 5.5 promotional video featuring Aniwat, a transgender woman, sitting in a wheelchair with an unusual neck position (BBC Thai 2022). The video was a caricature of Princess Chulabhorn, who often uses a wheelchair and has a distinctive posture. Both cases led to a public outcry from royalists demanding that the government take action. The video was even accused of mocking the disabled. Lazada was threatened with being charged under Article 112, and the army prohibited deliveries from the company (Hoskins 2022)—though as of this writing no legal action has been taken. Nevertheless, the cases showed that parodic sentiments had spread from the individual to the corporate level, reflecting the general perception of a legitimacy crisis with the royal family. Acts that were once meaningless displays for revering the monarch have become acts used against hegemony.

Salim is a word to describe conservative urban-educated middle-class baby boomers who support traditional establishments such as the monarchy and the use of military force. As such, they distrust any elements that pose a threat to their core values, such as the Thaksin government and a more liberal democratic system. Since this generation are now adults, they are convinced they are more qualified and morally superior when it comes to judging politics (Faris 2011). Though salim were once the main determiners of government stability, the word has regressed to becoming a derogatory identifier for people who prefer authoritarian governance. Kwai daeng (Red buffalo), once a term for uneducated provincial people who protested against the salim and their system, became a symbol of pride as society began seeing their cause as pro-democracy. The commemoration of the 1976 massacre, which had come to be regarded as obsolete by the public, gained interest among young people as it represented the democratic movement that had been suppressed by the military. None of this would have happened if not through the use of social networks to spread information, mock the regime, and display cynicism. Similarly, the Siamese Revolution of 1932, once viewed as a premature transformation to democracy, became a symbol of improvement for commoners.

Breaking with the Past

Waso Vandenhaute (2021) has discussed in detail how Thais have lost faith in “Thai-style democracy.” Thai-style democracy and its belief in “goodman politics,” supported by many royal speeches, originated from Dhammaracha occult and King Rama IX’s speech in which he said Thais could not prevent bad people from politics but could select good people to prevent bad people from governing the country (Bhumibol 1969). As hyper-royalism intensified from 1992, King Rama IX represented the ultimate “goodman” since he practiced Dhammaracha precepts well. His guiding influence in Thai politics gave birth to “guided democracy,” in which he guided his nation using goodmen. This strategy was successful in helping the economy prosper under the Prem Tinsulanonda government.

Prayut’s coup and government were welcomed initially because of his appeal as a good and loyal man. Nevertheless, his regime lost support due to its mismanagement and inability to improve the country’s economy. The death of King Rama IX and scandals of King Rama X had a ripple effect that lessened the junta’s legitimacy, since the monarchy and junta were viewed as being aligned. The goodness of the royal institution, which supports the government’s legitimacy, became questionable. With that came the realization that guided democracy or Thai-style democracy was not working anymore—what had been viewed as beneficial was actually contributing to people’s despair politically, economically, and mentally. Consequently, many chose to distance themselves from the past, from good and moral politics. The state’s emphasis on virtue and goodness became so intense that these qualities became objects of absurdity. Parodies and mockery of the monarch became a way for people to cope with reality, similar to stiob in the Socialist bloc during late socialism. The fact is that no matter how strong hegemony of form is, subversion will eventually find a way to bypass it. The irony of this type of regularity (where everything looks normal and people still perform meaningless activities, so there is no warning of change) is that the authoritarian system works with almost no direct resistance—a peaceful society. Nonetheless, since this system is not accustomed to change, it is also structurally fragile. The direct effect of laughter stemming from despair and anger is the delegitimization of the royal institution by convincing people to take it lightly (although the Thai government takes it very seriously). As a result, when there is an attempt at change, the system cannot adapt and maintain the status quo since people are already prepared for the change.

Dictators Have No Sense of Humor

As stated by Yurchak (2003) and Yael Navaro-Yashin (2002), small acts of subversion are allowed in the private sphere as a way for people to express their discontent. For the state, such acts in public must be prevented at all costs, apart from the few “acceptable” parodies in stiob. With traditional media in decline, the focus has shifted to new media and education. Thailand’s army established the Information Operations Unit to combat subversion in the online world, while the new preschool curriculum forces children to learn about King Rama X—mostly about his virtues, such as being the wise patriarch of the nation and a unifying figure (Thailand, Ministry of Education 2018; Wongsapan 2022). However, the intensity of royal propaganda led to an increasing number of demonstrations by middle-school students advocating for a propaganda-free curriculum.

In 2020 a constitutional amendment was proposed to abolish the authority of the senate to vote for the prime minister. Ultimately rejected, this was a petition by the ILaw Project and received more than 100,000 signatures, double the original target. The reason for the proposal was that senators were handpicked by the junta, giving General Prayut the advantage to be elected as prime minister. A crowd rallied to the parliament at Kiakkai to pressure the senate to accept the amendment because they wanted a democratic system in which the prime minister could be chosen (indirectly) by the people. During deliberations, the parliament was heavily guarded by fully equipped riot police. The People’s Party 2020 group rallied the people to confront the police. The protesters claimed to have an army (the masses) and navy (represented by floating rubber ducks) by their side. They brought rubber ducks to the Chaophraya River, behind the parliament. In the ensuing confrontation, the police deployed a high-pressure chemical water gun and the protesters used the rubber ducks as a shield. Rubber ducks, which are a protest symbol in Serbia, Kosovo, and Russia, are becoming a symbol of the masses in Thailand. Within a few days, the police banned a wholesale store in Bangkok from selling rubber ducks. The rubber ducks were called Kromluang Kiakkai Ratsadorn Boriruk, or “Prince Protector of People at Kiakkai.” In subsequent protests, these rubber ducks became an icon. An anonymous Facebook user started selling “Royally given duck calendars,” mocking the tradition of distributing calendars with photos of the royal family. The court jailed the seller for two years for selling something indirectly mocking King Rama X.

Sanctions against parodies and subversion came slow but firm. Many protest leaders were charged with lèse-majesté and accusations of sedition. Although most of the charges were eventually dismissed, the accused were ordered to be jailed without bail while awaiting the court’s decision because the charges fell under national security. In retaliation, many went on hunger strike to demand the right to bail. Many of them were not sui juris. The longest hunger strike lasted 64 days (Standard Team 2022). There were at least 15 cases of hunger strikes from 2021 to 2022 (Admin28 2022). All of this reflects the lengths to which both the state and youths were willing to go. While the state imposed sanctions to prevent anyone from undermining its authority, including through mockery, youths became more desperate. To protest against the regime and the abuse of legal power, they upped the stakes by going on dry fasts as a last resort.

On January 16, 2023, Orawan (Bam) and Thantawan (Tawan) announced their hunger strike against injustice, calling on the court to allow political prisoners to file for bail (Online Reporters 2023). They decided to go on hunger strike after the court canceled their friends’ bail. Bam and Tawan found themselves pushed into a corner. With the movement’s strength greatly weakened by despair, the chances of their being imprisoned while awaiting trial were now higher than before. They refused bail and used their bodies and lives as a final weapon against injustice; they had nothing left to lose. After nearly two months, the court finally heard their pleas and granted bail to 13 of their 16 fellow protesters who were on trial (Online Reporters 2023). On March 11, 2023, Bam and Tawan announced that they would stop their hunger strike as they could not survive much longer and their close confidant had asked them to stop (Online Reporters 2023). Some of their demands were met. They still urge the masses to continue fighting along with them.

From Laughter to Symbols

It was clear that various types of violence—from tear gas to high-pressure chemical water canon—used by the state could undermine morale. Consequently, the movement had to adopt new tactics. Symbols became a handy tool, replacing laughter with something more serious and more representative of the struggle of the masses. The use of the Hunger Games’ three-finger salute was the first symbol used to represent the movement’s three demands. The rubber duck was introduced later as a mascot of the movement and a mockery of the state—a mere plastic toy turned into a security threat. Bam and Tawan’s dry-fasting strikes were a symbol of nonviolent campaigns against the broken legal system. On March 29, 2023, a member of Taluwang (Penetrate the Palace), one of the many protesting groups, painted the wall of the Grand Palace with an anarchist symbol and a crossed-out number 112 (Khaosod English 2023). That man, along with his camerawoman, was apprehended on site by the police. To quote the anonymous artist Banksy, “Graffiti is one of the few tools you have if you have almost nothing.” The man who defaced the palace wall had almost nothing: he was a child of a CD vendor during the Red Shirt protest and had had to escape the bloody government crackdown. He was clearly a working-class person who had already experienced trauma and had nothing much left to lose (Khaosod English 2023). As for the camerawoman, at 15 she was the youngest person to be charged under Section 112 (Admin20 2023). She defied the court’s authority and the entire procedure by turning her back to the judge during the hearing (Admin20 2023). Within a day, similar graffiti was found across Bangkok. The Grand Palace wall was swiftly repainted the day it was defaced, and the next day there were mounted police patrolling the area. Posters showing the crossed-out number 112 by Commoner publishing house were taken down by undercover police without notification to the publishing house (Natthapol and Kittiya 2023). All these incidents demonstrated the fragile state of the hegemony of form. Every small act of defiance was met with an exaggerated reaction from the state. These reactions created friction that seemed absurd to the people and displayed the vulnerability of the state.

Conclusion

Posts with statements such as “You will see what you never saw” are frequently put up by Charnvit Kasetsiri, a renowned Thai historian. Thailand has been mired in a political crisis for almost two decades, during which time many of the “old” have declined while the “new” have grown up. However, in order to understand why “you will see what you never saw,” one has to understand the condition Thailand has been in for several years. There was hyper-royalism throughout the reign of King Rama IX and continuing into the reign of King Rama X. However, it intensified when the king had more power. As a result, at one point the state of hegemony in Thailand was similar to that of the late socialist Soviet bloc, as every act was reduced to face value and people performed meaningless acts in order to fit in. That was how the people were made to believe that things would stay the same forever. The eternal state ended when the reign was subjected to the differences between the two kings.

Cynicism and performativity have played an important role in creating and sustaining nations, especially in authoritarian societies. They are part of what Michael Herzfeld (2005) calls “cultural intimacy” by being part of the community of complicity. Simulation and pretense are means of cynicism and performativity in that they conceal people’s true thinking and motives in order to save them from prosecution. When hegemony of form is imperfect and the eternal state is undermined, people start to question the system and protest against oppression, seeking more creative ways.

Thailand joined the third wave of democratization in the 1990s. However, the attempt was unsuccessful because of the coup in 2006. From the 1990s to 2006, hegemony of form was developed until the eternal state was achieved. The loss of hegemony became visible during the final phase of King Rama IX’s reign and surfaced a few years into King Rama X’s. However, the cracks had begun long before, with many scandals about the royal family being discussed privately.

The proclaimed neutrality of the royal institution was disproved when the institution sided with the anti-government Yellow Shirts. With the violent crackdown on the Red Shirts by the military, many people became disillusioned about the neutrality of the royal institution. Anti-monarchy graffiti was found in the ruins of the Central World department store, and the Faiyen band released satirical songs questioning royal propaganda. The songs challenged the Dhammaracha precepts even before the widespread use of social media.

The 2020 wave of protests had unprecedentedly young participants who were concerned about their future. Royalist Marketplace was created on Facebook and became popular among this demographic. On Twitter, there were hashtags attracting people to join the movement. Information on flash protests spread through these platforms. Such actions led to cultural change. Many people who would have been happy to receive their university degree from the royal family opted out and instead received it from a parodic figure of someone they respected. In protests and daily life, the use of innuendo became more common. This was not only in the real world but also in the safe haven of the digital world. The Twitter clash between Thai and Chinese netizens is one example of Thai netizens using others to indirectly ridicule their royal institution. With fewer people showing respect to the royalty through their words and actions, the cost of repression increased—but not enough for the government to give in. The corporate world also exploited this trend, which prompted the army to take action. The word salim, once used with pride for those who opposed the elected government, has become something many people prefer to forget, while kwai daeng, once a derogatory term for Red Shirts, has become a source of pride.

One characteristic of Thai politics is the yearning for a morally superior person to place on a pedestal. However, mismanagement of the royal institution has tainted its image. The government’s intense hyper-royalism propaganda became so absurd after a point that people began responding with laughter.

The younger generation like to use Twitter. The social platform creates an illusion of masses of people, as retweets and comments perpetuate the fabricated reality of onsite political engagement. Though Twitter was used to rally people to protests, the number of people present was much lower than the number of tweets. The affect generated by the illusion and empowerment of Twitter—fear and anger—also played a huge role. Fear discouraged some people from joining the protest movement, while anger helped to radicalize others. Police brutality and the risk of severe punishment led many people to contribute financially rather than showing up. Feeling alienated, protest leaders resorted to more risky methods. This was the case with Tawan and Bam, who went on a dry fast to demand their friends’ right to bail. The government also arrested and charged children as young as 15 years with lèse-majesté.

With the government becoming more violent, cynicism could not protect the masses anymore. More people were charged with lèse-majesté for creating parodies, so the movement began using symbols instead. From the Hunger Games’ three-finger salute to the anarchist graffiti at the Grand Palace, protests became more subjective, yet everyone understood their meaning. For radicalized participants, turning their backs to the judge and not uttering a word was an act of opposing the Thai judicial system and its nontransparent treatment.

This study continues the long tradition of studies of satire and cynicism from late socialism to the Arab Spring uprising. It shows the digitization of resistance by Internet users who learned from the past and from other movements such as the one in Hong Kong. However, the government also learned about those movements. With symbols and protests inspired by popular culture, it is complicated for the authorities to explain why certain jokes are offensive and a national threat. This demonstrates the fragility of the eternal state, which the establishment is fighting to protect.

Accepted: August 21, 2023

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Dr. David Malitz for introducing me to the world of satire, Dr. Ivan Rajkovic for pushing me to initiate this project, and Dr. Jeroen Adam, who has always supported my work. I also appreciate the feedback from two anonymous reviewers, which improved this work tremendously.

References

@_nsyakinah. 2022. offer for indonesians: please roast our power figures more and in return we will roast your government so neither of us go to jail 🤝 thailand can join in too and we’ll talk shit about your monarchy. Twitter. https://twitter.com/_nsyakinah/status/1581669772348964865?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1581669772348964865%7Ctwgr%5E67878687e1c77bd6e6753e16b2ebb820fbf78173%7Ctwcon%5Es1_&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cxomedia.id%2Fgeneral-knowledge%2F20221019154455-55-176651%2Findonesia-malaysia-mengapa-kita-terus-bertengkar, accessed May 10, 2023.↩

Admin20. 2023. “Yok” Thukkuapkumkhadee Mor.112 To ik 15 wan Mae phu waiwangjai kho berk tua masan tae san mai anuyat rabu mai chai phu pokkrong lae phu tong ha yang mi thi prueksa kotmai mae yok yuenyan wa thoe mai khoei sen taeng tang krai ‘หยก’ ถูกควบคุมตัวคดี ม.112 ต่ออีก 15 วัน แม้ผู้ไว้วางใจขอเบิกตัวมาศาล แต่ศาลไม่อนุญาต ระบุไม่ใช่ผู้ปกครอง และ ผตห.ยังมีที่ปรึกษากฎหมาย แม้หยกยืนยันว่าเธอไม่เคยเซ็นแต่งตั้งใคร [“Yok” under arrest under Article 112 for another 15 days even though confidant calls for the court. The court refused, saying they are not parents and they also have a legal counselor even though Yok affirms that she never appointed any counselor]. Thailand Lawyer for Human Rights. https://tlhr2014.com/archives/55615, accessed May 8, 2023.↩ ↩

Admin28. 2022. Chak phai tueng tawan: Thopthuan patibatkan 22 Ratsadon ‘ot ahan’ phuea pratuang riakrong totan hai rat lae tulakan mop khwam yutitham จากไผ่ถึงตะวัน: ทบทวนปฏิบัติการ 22 ราษฎร ‘อดอาหาร’ เพื่อประท้วง-เรียกร้อง-ต่อต้าน ให้รัฐและตุลาการมอบความยุติธรรมกลับคืน [From Phai to Tawan, reconsider operation by 22 ordinary people “hunger striking” to protest-call out-defy]. Thailand Lawyer for Human Rights. July 29. https://tlhr2014.com/archives/43053, accessed May 19, 2023.↩

Anonymous. 2022a. Sarnyokfong 2 korha MobHarry Potter pi 62 “Mild” ti khlum chumnum mai phit thang thi anan don khadi 112, 116 ศาลยกฟ้อง 2 ข้อหา ม็อบแฮร์รี่พอตเตอร์ ปี 63 “มายด์” ตีขลุมชุมนุมไม่ผิด ทั้งที่อานนท์โดนคดี 112, 116 [Court dismisses two charges against Harry Potter protest in 2020, “Mind” said protest is not a crime even though Anon got charged under Articles 112 and 116]. Thai Post. November 28. https://www.thaipost.net/x-cite-news/272692/, accessed May 14, 2023.↩

―. 2022b. San tatsin cham khuk 2 pi “New Chatupon” Tang chut thai catwalk ratsadon chi mi chetana lolian ศาลตัดสินจำคุก 2 ปี “นิว จตุพร” แต่งชุดไทยแคตวอล์กราษฎร ชี้มีเจตนาล้อเลียน [Court sentences “New Jatuporn” to two years in prison for dressing in Thai catwalk costume, points out intent to mock]. Matichon มติชนออนไลน์. September 12. https://www.matichon.co.th/local/crime/news_3557679, accessed May 14, 2023.↩

Apichart Sathitniramai อภิชาต สถิตนิรามัย. 2012. Chae khaeng prathet thai: Krai aw bang yok mue khuen แช่แข็งประเทศไทย: ใครเอาบ้าง ยกมือขึ้น [Frozen Thailand: Who wants to join? Raise your hand]. ThaiPublica. November 27. https://thaipublica.org/2012/11/thailand-frozen/, accessed May 19, 2023.↩

Asa Khampha อาสา คำภา. 2019. Kwa cha khrong amnat nam: Kan khli klai tua khong krueakhai nai luang phai tai patisampan chon chan nam thai totsawat 2490–2530 กว่าจะครองอำนาจนำ : การคลี่คลายขยายตัวของเครือข่ายในหลวงภายใต้ปฏิสัมพันธ์ชนชั้นนำไทย ทศวรรษ 2490–2530 [Until hegemony is achieved: The expansion of the king’s network with the interaction among elites from 2490s to 2530s]. Nonthaburi: Same Sky Press.↩ ↩ ↩

Bangkok Post. 2016. King Appoints 10 Members to His Privy Council. Bangkok Post. December 6. https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/general/1152824/king-appoints-10-members-to-his-privy-council, accessed November 11, 2022.↩

Barron, Laignee. 2020. ‘We Share the Ideals of Democracy.’ How the Milk Tea Alliance Is Brewing Solidarity Among Activists in Asia and Beyond. Time. October 28. https://time.com/5904114/milk-tea-alliance/, accessed May 17, 2024.↩

BBC. 2020. Thai Protests: How Pro-Democracy Movement Gained Momentum. BBC News. October 15. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-54542252, accessed May 16, 2023.↩

BBC Thai. 2022. Laza da kho thot nayok sang to ro sopsuan kan talad ‘kao luang sathaban ลาซาด้าขอโทษ นายกฯ สั่ง ตร. สอบการตลาด ‘ก้าวล่วงสถาบันฯ’ [Lazada apologize: PM orders police to investigate “monarchy-related” marketing]. BBC News ไทย. May 6. https://www.bbc.com/thai/61338237, accessed May 7, 2023.↩

―. 2020. Anakhot mai: Matisan ratthathammanun sang yup pak anakot mai tat sit kammakan borihan 10 pi อนาคตใหม่: มติศาลรัฐธรรมนูญสั่งยุบพรรคอนาคตใหม่ ตัดสิทธิ กก.บห. 10 ปี [Future Forward: Constitutional court decision to dissolve Future Forward Party and ban its administrative committee from political activities for ten years]. BBC News ไทย. https://www.bbc.com/thai/thailand-51582581, accessed May 6, 2023.↩

Bhumibol Adulyadej ภูมิพลอดุลยเดช. 1969. Phrarachadamrusnainganphitheeperdnganchoomnumluksuahangchartkrangthi 6 พระราชดำรัสในงานพิธีเปิดงานชุมนุมลูกเสือแห่งชาติครั้งที๖ [His Majesty’s speech at the opening ceremony of the 6th National Scout Jamboree]. Silpakorn University Library. July 31 2024. https://lib.su.ac.th/royal-voices/resource/d8c81870-fc31-409a-b6cb-cb8b4d661f44/, accessed July 31, 2024.↩

Billig, Michael. 1999. Banal Nationalism. London: Sage.↩

Buchanan, James. 2020. How a Photo Sparked a Twitter War between Chinese Nationalist Trolls and Young Thais. VICE. April 14. https://www.vice.com/en/article/xgqjkw/twitter-war-thailand-china-nationalism-trolls-memes, accessed March 8, 2024.↩

Cod Satrusayang. 2020. Protesters Defiant as New Rally Hashtag Trends on Social Media Platforms. Thai Enquirer. October 15. https://www.thaienquirer.com/19630/protesters-defiant-as-new-rally-hashtag-trends-on-social-media-platforms/, accessed November 11, 2022.↩ ↩

Damir-Geilsdorf, Sabine and Milich, Stephan, eds. 2020. Creative Resistance: Political Humor in the Arab Uprisings. First Edition. transcript Verlag. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv371cdrf, accessed April 15, 2024.↩

Deutsche Welle. 2017. Regency Rules Altered, so Thai King Can Travel. DW. January 13. https://www.dw.com/en/thai-parliament-backs-constitutional-changes-allowing-king-easier-travel/a-37121671, accessed May 19, 2023.↩

Economist. 2019. Beauty and the Beast: Thailand’s Ruthless King. Economist 433(9166), p. 35.↩

Faris Yothasamuth ฟาริส โยธาสมุทร. 2011. Arai khue salim? Wa duay thi ma boribot khwammai lae khunnalaksana chapo อะไรคือสลิ่ม? ว่าด้วยที่มา บริบทความหมาย และคุณลักษณะเฉพาะ [What is a wedge? Regarding the origin, context and meaning, and specific features]. Prachatai ประชาไท. November 21. https://prachatai.com/journal/2011/11/37957, accessed April 13, 2023.↩

Faulder, Dominic. 2016. Thais Observe the 70th Anniversary of King Bhumibol Adulyadej’s Accession. Nikkei Asia. June 16. https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/Thais-observe-the-70th-anniversary-of-King-Bhumibol-Adulyadej-s-accession, accessed November 11, 2022.↩

Ferrara, Federico. 2019. The Logic of Thailand’s Royalist Coups d’État. In Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Thailand, edited by Pavin Chachavalpongpun, pp. 71–85. London: Routledge.↩

Freetupandit. 2020. Phop kan prungni “Lan pho” na Thammasat Thaphrachan 10.00 pen ton pai! พบกันพรุ่งนี้ “ลานโพธิ์”ณ ธรรมศาสตร์ ท่าพระจันทร์เวลา 10.00 เป็นต้นไป! [See you tomorrow at Pho Square at Thammasat Tha Prachan 10.00 am onwards!]. [Status update] Facebook. October 22. https://www.facebook.com/freetupandit/photos/pb.100064514691919.-207520000/103645911542744/?type=3, accessed October 19, 2023.↩

Handley, Paul M. 2014. The King Never Smiles: A Biography of Thailand’s Bhumibol Adulyadej. New Haven: Yale University Press.↩ ↩

Herzfeld, Michael. 2005. Cultural Intimacy: Social Poetics in the Nation-State. Second Edition. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203826195.↩

Hewison, Kevin. 2019. The Monarchy and Succession. In Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Thailand, edited by Pavin Chachavalpongpun, pp. 118–133. New York: Routledge.↩

Hoskins, Peter. 2022. Thai Army Boycotts E-commerce Giant Lazada over Video. BBC News. May 10. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-61389117, accessed April 13, 2023.↩

Isranews อิศระนิวส์. 2020. Bandit TU. Khao som rap parinyatri 48.52% chak chamnuan thang mot 7,756 khon บัณฑิต มธ.เข้าซ้อมรับปริญญาตรี 48.52% จากจำนวนทั้งหมด 7,756 คน [TU graduates attend the bachelor’s degree rehearsal, 48.52% out of a total of 7,756 people]. Isra News. October 26. https://www.isranews.org/article/isranews-news/93027-isranews-tu.html, accessed November 11, 2022.↩ ↩

Kanokrat Lertchoosakul. 2021a. The White Ribbon Movement: High School Students in the 2020 Thai Youth Protests. Critical Asian Studies 53(2): 206–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/14672715.2021.1883452.↩ ↩

―. 2021b. Thai Youth Movements in Comparison: White Ribbons in 2020 and Din Daeng in 2021. New Mandala. https://www.newmandala.org/thai-youth-movements-in-comparison-white-ribbons-in-2020-and-din-daeng-in-2021/, accessed May 6, 2023.↩

Khaosod English. 2023. Graffiti on the Grand Palace Wall, Controversial Lese Majeste Law. Khaosod English. https://www.khaosodenglish.com/news/2023/03/30/graffiti-lese-majeste/, accessed May 8, 2023.↩ ↩

Khorapin Phuaphansawat. 2018. Anti-Royalism in Thailand since 2006: Ideological Shifts and Resistance. Journal of Contemporary Asia 48(3): 363–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2018.1427021.↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

―. 2017. “My Eyes Are Open but My Lips Are Whispering”: Linguistic and Symbolic Forms of Resistance in Thailand during 2006–2016. PhD dissertation, University of Massachusetts Amherst. https://doi.org/10.7275/10006944.0.↩ ↩

King, Gilbert. 2011. Long Live the King. Smithsonian Magazine. September 28. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/long-live-the-king-1-91081660/, accessed November 11, 2022.↩

Kurlantzick, Joshua. 2020. A Popular Thai Opposition Party Was Disbanded: What Happens Next? Council on Foreign Relations. February 27. https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/thailand-future-forward-party-disbanded-thanathorn-protest, accessed November 11, 2022.↩

ManagerOnline. 2022. “Thai Vietjet” Chichaeng len muk bin “Nan-Munich” don khaojai phit tae lai khon yang khajai phrom loek bin “ไทยเวียตเจ็ท” ชี้แจง เล่นมุกบิน “น่าน-มิวนิค” โดนเข้าใจผิด แต่หลายคนยังคาใจ พร้อมเลิกบิน [“Thai Vietjet” explains that making a joke about flying “Nan-Munich” was misunderstood, but many are still confused and are ready to stop flying]. Manager. April 2. https://mgronline.com/travel/detail/9650000031971, accessed November 11, 2022.↩

Marx, Karl and Engels, Friedrich. 2017. The Communist Manifesto, edited by Jeffrey C. Isaac. New Haven: Yale University Press. https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.12987/9780300163209/html, accessed November 11, 2022.↩

Masina, Pietro. 2016. Thailand 2016: The Death of King Bhumibol and the Deepening of the Political Crisis. Asia Maior 27: 243–259.↩

Mbembe, Achille. 1992. The Banality of Power and the Aesthetics of Vulgarity in the Postcolony. Public Culture 4(2): 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-4-2-1.↩ ↩ ↩

McCargo, Duncan. 2021. Disruptors’ Dilemma? Thailand’s 2020 Gen Z Protests. Critical Asian Studies 53(2): 175–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/14672715.2021.1876522.↩ ↩

―. 2005. Network Monarchy and Legitimacy Crises in Thailand. Pacific Review 18(4): 499–519. https://doi.org/10.1080/09512740500338937.↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

Mérieau, Eugénie. 2016. Thailand’s Deep State, Royal Power and the Constitutional Court (1997–2015). Journal of Contemporary Asia 46(3): 445–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2016.1151917.↩

Naruemon Thabchumpon and McCargo, Duncan. 2011. Urbanized Villagers in the 2010 Thai Redshirt Protests. Asian Survey 51(6): 993–1018. https://doi.org/10.1525/as.2011.51.6.993, accessed March 29, 2024.↩

Natthapol Meksopol ณัฐพล เมฆโสภณ and Kittiya Orainthra กิตติยา อรอินทร์. 2023. Ruam korani “Tamruat-thahan” Pai ngan nangsue yuet rue but buk samnak phim ang “minme – lamok – sang khwam mai sabaijai” รวมกรณี “ตำรวจ-ทหาร” ไปงานหนังสือฯ ยึด-รื้อบูธ บุกสำนักพิมพ์ อ้าง “หมิ่นเหม่-ลามก-สร้างความไม่สบายใจ” [Includes cases of police and soldiers going to book fairs, seizing and dismantling booths, raiding publishing houses claiming “disrespectful-obscene-creating discomfort”]. Prachatai.com ประชาไท. https://prachatai.com/journal/2023/03/103424, accessed May 19, 2023.↩

Navaro-Yashin, Yael. 2002. Faces of the State: Secularism and Public Life in Turkey. Princeton: Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780691214283.↩ ↩

Nidhi Eawsriwong นิธิ เอียวศรีวงศ์. 2017. Rat phan tuen รัฐพันตื้น [The shallow state]. Matichon มติชนออนไลน์. August 28. https://www.matichon.co.th/columnists/news_643049, accessed March 20, 2023.↩

Online Reporters. 2023. Activists End Hunger Strike After 52 Days. Bangkok Post. March 11. https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/general/2525574/activists-end-hunger-strike-after-52-day, accessed May 8, 2023.↩ ↩ ↩

Pasuk Phongpaichit and Baker, Chris. 2009. Thaksin. Second Edition. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books.↩

Pavin Chachavalpongpun. 2022. Kingdom of Fear: Royal Governance under Thailand’s King Vajiralongkorn. Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs 41(3): 359–377. https://doi.org/10.1177/18681034221111176.↩

―. 2020. Introduction. In Coup, King, Crisis: A Critical Interregnum in Thailand, edited by Pavin Chachavalpongpun, pp. 1–31. New Haven: Yale University Press.↩

Phasuk Sunai. 2020. No Justice 10 Years after Thailand’s “Red Shirt” Crackdown. Human Rights Watch. October 28. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/05/12/no-justice-10-years-after-thailands-red-shirt-crackdown, accessed April 6, 2024.↩