Contents>> Vol. 13, No. 2

US-Vietnam Defense Diplomacy: Challenges from the Ukraine War

Pham Thi Yen*

*Faculty of Oriental Studies, Van Hien University, HungHau Campus: Nguyen Van Linh Avenue, Southern City Urban Area, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

e-mail: yenpt[at]vhu.edu.vn

![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7717-5472

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7717-5472

DOI: 10.20495/seas.13.2_201

This article analyzes activities of defense diplomacy between Vietnam and the US before the Ukraine war. Based on these, the author assesses the possible impacts of the war on US-Vietnam defense cooperation. By clarifying Vietnam’s stance on the Ukraine war as well as the benefits that the US enjoys through its relationship with Vietnam, the author projects an optimistic view of the prospects of US-Vietnam relations in general and the two nations’ defense diplomacy in particular. The article asserts that Russia’s “special military campaign” in Ukraine had short-term impacts on US-Vietnam relations, but in the long term the United States’ strategic interest in cooperating with Vietnam remains unchanged. The fact that the US has actively sanctioned Russia over the Ukraine war does not mean that it has forgotten China, which has been stepping up its unilateral actions in the Indo-Pacific region, where the US is also building up its influence. Moreover, the concern that China may imitate Russia to use force against Taiwan or in the South China Sea will likely further motivate the US to increase cooperation with Vietnam.

Keywords: US-Vietnam relations, defense diplomacy, Indo-Pacific, Ukraine war, Vietnam’s perspective, challenges

Introduction

Defense diplomacy—which is sometimes labeled as military diplomacy—has emerged as one of the most important tools of military art in its attempt to minimize the use of force, although its precise definition has not yet been agreed upon. Historically, the term appeared in the last decade of the twentieth century. The 1998 “Strategic Defence Review,” which defined the scope of operations of the UK armed forces, referred to these activities as “defense diplomacy” deployed to

provide forces that are responsive to the diverse range of operations conducted by the Ministry of Defence to dispel dissolving hostilities, building and maintaining trust, and supporting the development of democratically responsible armed forces, thereby making a significant contribution to conflict prevention and resolution. (New Challenges to Defence Diplomacy 1999, 38)

Juan Emilio Cheyre in The Oxford Handbook of Modern Diplomacy (2013) defined defense diplomacy as “implementation, without coercion [or without urgent international or national obligations], in peaceful time of defence resources to achieve specific national targets, primarily through relationship with others [defense factors/elements based abroad]” (Cheyre 2013, 2).

Dhruva Jaishankar defined defense diplomacy at the widest and narrowest levels. Defense diplomacy, according to its broadest definition, covers almost all outward military operations. Under a narrower definition, the term refers to military activities carried out with the sole purpose of diplomacy (Jaishankar 2016, 18). Defense diplomacy activities can be seen as a variant of soft power, used for such purposes as eliminating hostility and building and maintaining trust, supporting the development of the armed forces, and contributing to preventing and resolving conflicts. Although there are many different understandings of the concept, in general the main goal of defense diplomacy is to implement the state’s security policy, and its mission is to create stable, long-term international relations in the field of defense (Drab 2018, 59). Ian Storey (2021) perceives defense diplomacy as a political instrument that can be utilized to serve a multitude of objectives, including attempts to expand political, economic, and military influence in foreign countries as well as mitigate the influence of rival nations. Additionally, defense diplomacy can facilitate comprehension of the security perspectives and military capabilities of other countries, and enhance defense cooperation with friendly nations. Capacity-building support can also be offered to allies, partners, and friends as part of this process (Storey 2021). Accordingly, defense diplomacy activities include arms sales, combined military exercises, educational exchanges, naval port calls, strategic dialogues, and participation in peacekeeping and humanitarian and disaster relief operations.

Thus, in essence, the connotation of defense diplomacy is close to defense cooperation—which is understood as a general term for the scope of activities carried out by the Ministry of Defense with allies and other friendly countries to promote international security. Accordingly, the activities of defense cooperation include (but need not be confined to) security assistance, industrial cooperation, armaments cooperation, Foreign Military Sales, training, logistics cooperation, cooperative research and development, Foreign Comparative Testing, and Host Nation Support (DAU 2023)—which are also prominent activities of defense diplomacy. However, the difference between these two concepts lies in their political connotations. While defense diplomacy emphasizes peace, defense cooperation does not necessarily do so. For example, in war, certain parties may cooperate with each other against one or more other parties.

The Vietnamese government considers defense diplomacy to be a critical task and an important component of its three pillars: Party diplomacy, state diplomacy, and people-to-people diplomacy. It strives to protect the country by preventing conflicts early on and resolving disputes peacefully in accordance with international law, contributing to building a peaceful environment, and strengthening strategic trust with partners to develop the country (Government of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam 2021). It should be noted that Vietnam has not used the term “defense diplomacy” in official documents of the Party and the state. Instead, it uses the phrase “foreign defense affairs” (đối ngoại quốc phòng) or, more broadly, “defense cooperation” and “defense cooperation relations,” all of which emphasize the peaceful spirit of national defense. Therefore, many Vietnamese scholars use these concepts interchangeably (Nguyễn Thị Huệ 2023).

The main purpose of this article is to clarify the deployment of defense diplomacy between Vietnam and the US since 1995, then assess the challenges of the Ukraine war with regard to US-Vietnam relations in general and defense cooperation between the two countries in particular. The analysis is conducted based on the perspective of balance of power theory and theory of great powers balance. The balance of power theory helps the author explain why the US has increased its presence in the Indo-Pacific region, thereby strengthening relations with Vietnam, in the face of China’s strong rise. Meanwhile, the theory of great powers balance helps to clarify Vietnam’s tendency to promote relations with the US as well as shed light on the country’s caution in the face of “enthusiasm” from the US.

The article is divided into two parts. The first part goes into the details of defense diplomacy between Vietnam and the US from 1995 to the present. Part two assesses the challenges of Vietnam-US relations since the outbreak of the Ukraine war, after clarifying Vietnam’s position on the war.

I Defense Diplomacy between Vietnam and the US since 1995

The US-Vietnam relationship is a special one in the international political arena. Both countries have made incredible efforts to promote cooperation in the spirit of putting aside the past and looking toward the future. In 2013 the two countries established a Comprehensive Partnership, and on September 10, 2023 the relationship was elevated to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership. This event positioned the United States on an equal footing with China, as both became Comprehensive Strategic Partners of Vietnam, bypassing the level of a Strategic Partnership. The trade turnover between Vietnam and the US has grown continuously, from US$450 million in 1994 to US$123 billion in 2022 (Government of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam 2023). The US is Vietnam’s second-largest trading partner after China, while Vietnam is among the top ten trading partners of the US. In terms of foreign direct investment, America is Vietnam’s 11th biggest investor, with a total of 1,138 projects and accumulative registered capital of US$10.28 billion as of end-2021, up 32.8 percent and 4.1 percent from 2017, respectively (Hong-Kong Nguyen and Pham-Muoi Nguyen 2022). All of these facts demonstrate the unremitting efforts and increasing trust between the two countries. In that space, defense diplomacy, although it began more slowly than other areas of the relationship, has gradually been tightened and manifested in many practical activities. In the first ten years after the normalization of diplomatic relations between the two countries, defense interactions between them were limited to Vietnam sending officers to attend seminars of the US Pacific Command; exchanges of high-ranking officials; and cooperation in search and rescue, military medicine, and demining. From that initial foundation, however, defense diplomacy gradually took on a more prominent role, contributing to the development of US-Vietnam relations.

I-1 Defense Leaders’ Bilateral Interactions

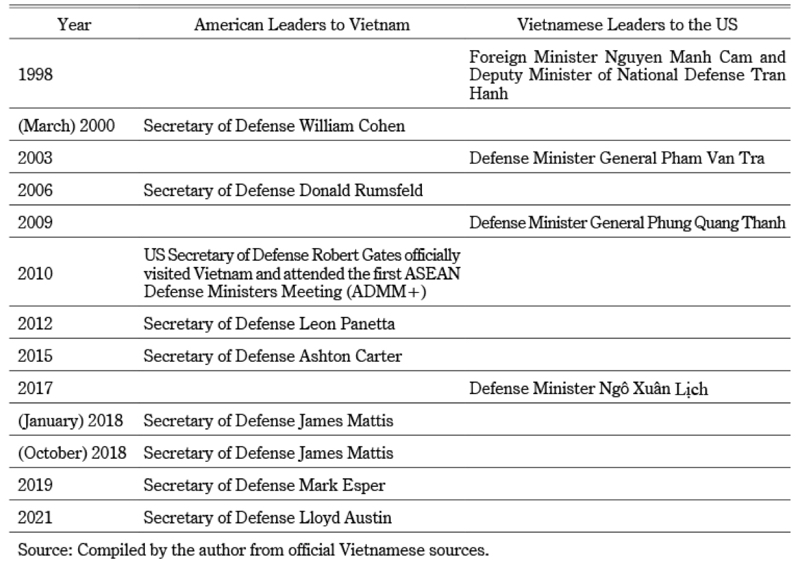

Bilateral defense communications between Vietnam and the US have been built through visits by defense leaders of the two sides and three dialogue mechanisms: (1) bilateral defense dialogue chaired by the US Pacific Command, starting in 2005; (2) security-politics-defense dialogue chaired by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the two sides, starting in 2008; and (3) defense policy dialogue chaired by the two Defense Ministries, starting in 2010. In the early years after the normalization of relations, although there were not many significant activities, a series of reciprocal visits were made to build the foundation for US-Vietnam defense relations. The first contact was the visit to Vietnam by the US deputy assistant secretary of defense for Asia-Pacific affairs, in March 1997. This was followed by a visit to the US by Vietnamese Deputy Defense Minister Tran Hanh in October 1998, shortly after Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs Nguyen Manh Cam visited the Pentagon that same month.

US Secretary of Defense William Cohen’s visit to Vietnam in 2000 began to make a difference as it marked the first visit by a US defense secretary to Vietnam since the Vietnam War. This event became even more meaningful since it took place on the eve of President Bill Clinton’s visit to Vietnam, which helped create positive coordination and bring the two countries’ relations to a new height. Three years later, in 2003, General Pham Van Tra became the first Vietnamese defense minister to visit the US, giving a new impetus to defense cooperation between the two countries. On this occasion, the leaders of the two Defense Ministries agreed to hold meetings and exchanges at the defense ministerial level every three years on a rotating basis between the two countries. This was considered a visit of historic significance, symbolizing a new phase of US-Vietnam relations, in which there were regular meetings and exchanges between defense leaders of the two sides (see Table 1).

Table 1 Visits by Defense Leaders from the US and Vietnam

Prime Minister Phan Van Khai’s subsequent visit to the US in 2005 further opened up the defense relationship between Vietnam and the US. As the first high-ranking Vietnamese leader to pay an official visit to the US after the war, Prime Minister Phan Van Khai took an important step when he signed a memorandum for Vietnam to participate in Washington’s international military education and training program. Although Vietnam later participated only in less sensitive programs (English training), this activity also helped to strengthen political trust and dialogue, which created an important foundation for the two sides to promote cooperation. Bilateral defense dialogues between the two countries were started in 2005, chaired by the US Pacific Command (Nguyễn Đức Toàn 2016, 66).

As agreed in 2003, the defense ministers of Vietnam and the United States alternately made reciprocal visits in 2006 and 2009, strengthening the growth momentum of bilateral defense relations. After the 2006 visit to Vietnam by US Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, the George W. Bush administration announced a partial relaxation of the ban on the sale of non-lethal defense equipment to Vietnam on December 29, 2006, paving the way for US companies to export some defense goods and services to Vietnam (Nguyễn Mại 2008).

In June 2008, on the occasion of Vietnamese Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung’s visit to Washington, the two countries agreed to hold security-politics-defense dialogues at the deputy ministerial level. This form of dialogue—which was first held in October 2008 in Washington—became an important annual mechanism for Vietnam and the US to promote cooperation on security and defense issues. The US-Vietnam defense dialogue took on a more focused direction in 2010, when the two Defense Ministries agreed to hold a defense policy dialogue at the deputy ministerial level. The objective of the dialogue was to help the two Defense Ministries strengthen cooperation, enhance mutual trust and understanding, and contribute to peace and stability in the region. The defense policy dialogue together with the security-politics-defense dialogue have become two strategic dialogue mechanisms in US-Vietnam defense cooperation and are held almost every year.

In 2011, within the framework of the second US-Vietnam defense policy dialogue, the two countries signed a memorandum of understanding on promoting bilateral defense cooperation (Tuổi Trẻ 2011), which identified five key areas: (1) maritime security cooperation, (2) search-and-rescue cooperation, (3) peacekeeping operations, (4) humanitarian and disaster relief, and (5) cooperation between defense universities and research institutes. The memorandum of understanding was a big step: it marked the first time the two countries officially formed a clear framework for defense cooperation. Although the agreement was only in the form of a memorandum of understanding, with a low level of legal binding, it was a very important milestone. The mechanism for defense cooperation between Vietnam and the US was elevated to a Joint Vision Statement during US Defense Secretary Ashton Carter’s visit to Vietnam in 2015. US-Vietnam defense cooperation then started to be implemented on the basis of the memorandum of understanding (in 2011) and the Declaration of Joint Vision on Defense Cooperation (in 2015).

Accordingly, there was a series of activities to tighten defense ties between Vietnam and the US. Especially from 2010, visits by defense ministers became more frequent, no longer based on the previous principle of rotating every three years. More significantly, these regular exchanges took place on Washington’s initiative, with the US secretary of defense visiting Vietnam in 2010, 2012, 2015, 2018 (twice), 2019, and 2021. In 2012, during his visit to Vietnam, US Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta called at Cam Ranh port1)—where there was a US military base during the Vietnam War. This event symbolized the good prospects of US-Vietnam relations, especially in the context of the US adjusting its policy toward a pivot to Asia in order to contain China.

The two countries’ subsequent actions in the following years demonstrated the breakthrough growth of US-Vietnam defense relations. In December 2013 US Secretary of State John Kerry visited Vietnam, where he announced that the US intended to provide new assistance to Vietnam with a value of up to US$18 million; this would start with personnel training and the provision of five high-speed patrol boats (US Department of State 2013). In October 2014 the US partially lifted the arms embargo on Vietnam, and in May 2016 this ban was officially done away with during President Barack Obama’s emotional visit to Vietnam.

The progress of US-Vietnam defense cooperation continued to be displayed through subsequent visits to Vietnam by US defense leaders. In particular, in 2018 US Defense Secretary James Mattis visited Vietnam twice (in January and October). While the first trip set the stage for the historic visit of the aircraft carrier USS Carl Vinson to Da Nang port two months later (March 2018), Mattis’s return to Vietnam for the second time in less than a year showed America’s attention to strengthening its partnership with Vietnam. After Mattis, the new US defense secretary, Mark T. Esper, visited Vietnam in November 2019, reaffirming the US commitment to relations with Vietnam. During the visit, Esper called for an end to bullying and illegal activities that were negatively affecting coastal ASEAN countries, including Vietnam; he asserted that “such behavior is in stark contrast to the US vision of a Free and Open Indo-Pacific in which all countries, large or small, can develop together in peace and stability” (VOV 2019). More important, Esper once again emphasized the United States’ support for a strong, prosperous, and independent Vietnam that would contribute to international security and the rule of law. At the same time, he also stressed the importance of the bilateral partnership between Vietnam and the US as well as how this partnership had contributed to peace and stability in the Indo-Pacific region.

The messages that Esper conveyed were very meaningful to Vietnam in the context of China bullying Vietnam in the South China Sea. In July 2019, the Chinese ship Haiyang Dizhi 8 violated Vietnam’s exclusive economic zone to supposedly carry out a petroleum survey and seismic research. China blatantly repeated its illegal action in the waters of Vanguard Bank,2) which was completely within Vietnam’s exclusive economic zone, as if it wanted to challenge the power of international law. Esper’s statement in this context therefore showed the United States’ support and sympathy for Vietnam. The fact that Esper visited Vietnam soon after replacing Mattis also proved America’s commitment to strengthening relations with Vietnam despite the turnover of personnel during President Donald Trump’s administration at the time.

I-2 Ship Visits and Naval Exercises

In addition to exchanges between defense leaders, visits by military ships made a great contribution to the process of strengthening US-Vietnam defense relations. After the first successful visit by a Vietnamese defense minister to the US—General Pham Van Tra in 2003—US Navy warships were allowed to visit Vietnam. A week after the historic visit by General Pham Van Tra, at noon on November 18, 2003, the US destroyer USS Vandegrift FFG-48 docked at Saigon port. This was the first visit by an American naval ship to Vietnam after nearly thirty years, and it was viewed as a symbol of ice-breaking in US-Vietnam relations. Over the following years, many US warships made friendly visits to Vietnamese ports,3) conducting meaningful civilian exchanges. For instance, the naval medical ship USNS Mercy visited and treated more than eleven thousand Nha Trang patients in June 2008, and it continued to do the same with thousands of Quy Nhon people two years later (June 2010). These were not only symbolic activities of defense diplomacy; with the practical significance of the visits by US ships, the understanding and trust between the peoples of the two countries were also enhanced.

The significance of American ships in Vietnam was most evident in Cam Ranh Bay. After Vietnam announced (in 2010) the opening of Cam Ranh to military and civilian ships of all countries in need, the US became the first partner to make use of this strategic gulf. In November 2011 the USNS Richard E. Byrd, a dry cargo/ammunition ship of the 7th Fleet of the US Navy, made a historic visit to Cam Ranh (MarineLink 2011), marking the first arrival of a US naval ship at Cam Ranh port in more than three decades (since 1975). The USNS Richard E. Byrd remained at Cam Ranh port for seven days to carry out regular repair and maintenance. The majority of staff on board were civilian forces, helping to reinforce the peaceful goodwill and cooperation that the two countries had built. The sight of American ships in Cam Ranh became more frequent after Cam Ranh international logistics service port came into operation in March 2016. After the USS John S. McCain and the submarine USS Frank Cable (AS 40) became the first US Navy ships to visit the strategic port in October 2016, a series of visits were made by other naval vessels. Famous American warships such as the USS Mustin, USNS Fall River (T-EPF-4), and USS Coronado (LCS 4) showed up in Cam Ranh within a short period of time. Among the major powers that were interested in and visited Cam Ranh international logistics service port, the US was the country with the highest number of visits (Pham Thi Yen 2021, 41).

There was no record of US warships docking at Cam Ranh port in 2018; however, the visit of the aircraft carrier USS Carl Vinson to Da Nang port in March 2018 marked a new turning point in defense diplomacy between Vietnam and the US. An American aircraft carrier appearing for the first time in Vietnam was an important symbol, a testament to America’s growing interest in the country. In March 2020, exactly two years after the visit of the USS Carl Vinson, a second US aircraft carrier, USS Theodore Roosevelt, called at Da Nang port, conducting technical, sports, and community exchanges in the central coastal city. This was the first event commemorating the 25th anniversary of US-Vietnam relations.

According to the report by Radio Free Asia on July 5, 2022, the aircraft carrier USS Ronald Reagan was scheduled to visit Vietnam in the latter half of July (Army Recognition 2022). However, this plan was scrapped following the crisis that erupted after the visit to Taiwan by Nancy Pelosi, the Speaker of the US House of Representatives. In fact, it is reported that the US had been pushing for an annual aircraft carrier visit to Vietnam but Vietnam had consistently declined. Vietnam’s reluctance to host frequent visits by US aircraft carriers stemmed from the potential security implications that may have had on the country’s relations with China. The regular presence of US aircraft carriers may have sent unintended messages to China and even been perceived as a hostile act, thus complicating Vietnam’s efforts to balance its relationships with major powers and peacefully resolve territorial disputes.

Apart from the visits by US ships, there were joint military exercises for peaceful purposes by Vietnam and the US. One notable feature of Vietnam’s participation in joint military exercises with the United States and other countries has been its confinement to training activities. Vietnam engages only in diễn tập (practice/exercise; positive connotation) rather than tập trận (exercise; negative connotation), in order to avoid sending messages of taking sides to prevent/counter the other side, which is in line with its steadfast “Four Nos” policy. Accordingly, joint military exercises between the US and Vietnam have been conducted since 2010 with an initial focus on non-traditional security issues of concern to the two countries. On August 8, 2010, the US nuclear aircraft carrier USS George Washington arrived in international waters off Da Nang and conducted exchange activities with Vietnamese military and government officials. The two navies then conducted a joint search-and-rescue exercise. In 2011 and 2012, the USS George Washington continued to welcome delegations of Vietnamese officials and military officers while operating in the South China Sea.

In 2012, Vietnam participated in the Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) exercise for the first time as an observer. Started in the 1970s, RIMPAC is the world’s largest multilateral naval exercise; it is organized by the United States every two years in areas of Hawaii and Southern California. Vietnam continued to be an observer at RIMPAC 2016, then in 2018 it sent a force (without warships) to attend for the first time.4) Also, since 2018, Vietnam has participated in Southeast Asia Cooperation and Training (SEACAT)—an annual maritime exercise initiated by the US in 2002 with the original name “Southeast Asian Cooperation against Terrorism.” SEACAT aims to promote commitments on partnership, maritime security, and stability in Southeast Asia. To date, Vietnam has participated in this exercise three times.5) Besides SEACAT, Vietnam has also cooperated with the US in another form of multilateral exercise in Southeast Asia, the ASEAN-US maritime exercise. This exercise was held in September 2019 under the agreement signed between ASEAN defense ministers and the US in 2018. The participation of all ASEAN members (including Vietnam) marked the first time that the ten ASEAN countries had a simultaneous military presence in the South China Sea.6) The ASEAN-US exercise—held under the theme of “Enhancing mutual understanding and combined maritime combat capability”—highlighted the interaction and coordination between ASEAN and the US in the face of maritime security challenges in the region. This activity demonstrated that ASEAN’s trend toward multilateralism7) was not merely symbolic but also brought value to each member country, especially Vietnam.

Although ship visits and maritime exercises are symbolic in nature, such continuous interaction has fostered the substantial development of Vietnam-US defense relations, especially in the fields of military aid and post-war settlement.

I-3 Defense Trade and Defense Aid

Due to historical factors, Vietnam’s largest partner in defense trade is Russia. Although the US was the world’s largest arms supplier and Vietnam-US relations have existed since 1995, defense cooperation between Vietnam and the US in the early years was not normal. This was because the ban on the sale of weapons (both lethal and non-lethal) imposed on Vietnam since 1984 had not been lifted. After 2006, when the George W. Bush administration allowed the sale of non-lethal military equipment to Vietnam (Jordan et al. 2012, 6), the door to defense trade cooperation between the two countries was partly opened. Unfortunately, nearly ten years later (in 2014), the promotion of cooperation in defense trade between Vietnam and the US came to a halt because the latter’s focus shifted to the Middle East in its fight against terrorism. Entering the 2010s, given the strong rise of China, the US made a “pivot” to Asia in which it reinforced alliance connections as well as promoted relations with potential partners in the region. The relationship between Vietnam and the US was strengthened again, creating a foundation for the prospect of defense trade between the two countries.

Nearly two years after announcing a partial lifting of the ban on the sale of lethal weapons to Vietnam (October 2014), in May 2016 US President Obama announced a complete lifting of the ban, which bore many marks of a hostile past. Vietnam-US relations from that moment were officially considered fully normal, which meant Vietnam had more choices in defense equipment procurement; it also had the opportunity to access military equipment with modern technology from the US, which helped to improve its defense capacity, especially in the field of maritime security.

Cooperation opportunities were created shortly later through defense aid activities. At the end of 2017, Vietnam received the 3,250-ton Hamilton-class cutter Morgenthau (WHEC 722)8) from the US Coast Guard. This was the first major weapons transfer from the US to Vietnam, and it helped Vietnam strengthen its maritime law enforcement capabilities and search-and-rescue capabilities at sea. Next, it was announced during the visit to Vietnam by US Defense Secretary Esper that a second Hamilton-class Coast Guard ship would be transferred to Vietnam in 2019 (VOV 2019). The last Hamilton-class ship of the US Coast Guard, Douglas Munro (WHEC 724), was also declared decommissioned at the end of March 2021; and according to an unofficial source, this last ship would also be transferred to Vietnam (Trúc Huỳnh and Yến My 2021)—though that has not happened yet. The US Coast Guard has a total of 12 decommissioned Hamilton-class ships and it has so far transferred or pledged to transport to Bangladesh (two), Bahrain (one), Nigeria (two), the Philippines (three), Sri Lanka (one), and Vietnam (two). If Vietnam receives the Douglas Munro (WHEC 724), it will join the Philippines—a regional ally of the US—in receiving the maximum number of these large patrol boats.

According to the US State Department, from 2016 to 2019 Vietnam received more than US$150 million in security assistance from the US Foreign Military Financing program (US, Bureau of Political-Military Affairs 2020), of which more than US$58 million was for supporting the transfer of the two large Hamilton-class patrol ships from the US Coast Guard mentioned above. The program also supported the supply of 24 Metal Shark high-speed patrol boats to the Vietnam Coast Guard to improve its maritime capacity, of which the last six were handed over in May 2020 (Anh Sơn 2021).

Apart from the patrol boats, Vietnam was granted access to unmanned aircraft systems made in the United States. Per the US Department of Defense, Vietnam was scheduled to receive six ScanEagle unmanned aerial vehicles with an overall value of over US$9.7 million (US Department of Defense 2019). It is not known whether these have been delivered. Furthermore, the US is scheduled to transport 12 T-6 military training aircraft to Vietnam within the 2024–27 time frame (Tuoi Tre News 2022), which will aid in enhancing pilot training in the Southeast Asian nation. The T-6 aircraft program also creates possibilities for cooperation between the two countries in the areas of logistics, flight safety, and aviation medicine, and the US can potentially transfer other defense equipment to Vietnam. Additionally, Vietnam has registered its pilots to participate in the US Air Force training program in the United States. In 2019, Senior Lieutenant Dang Duc Toai became the first Vietnamese pilot to complete a training course utilizing T-6 trainer aircraft under the 52-week US Air Force Aviation Leadership Program. All of these undertakings demonstrate that defense cooperation between Vietnam and the US is not only symbolic but also practical.

I-4 Cooperation to Resolve War “Legacy” Issues

Another feature of the Vietnam-US defense relationship is resolving the consequences of the Vietnam War, including mainly the issues of Agent Orange/dioxin and the search for soldiers missing in action (MIA). These are legacies left over from the fierce armed confrontation between Vietnam and the US. Since the normalization of relations, such issues have been jointly worked on by the two countries, as a testament to the willingness of the two former enemies to ignore the past by facing the past. It is estimated that from 1961 to 1971, the US military sprayed about 11 million to 12 million liters of Agent Orange on the battlefields of Vietnam and about five million Vietnamese people (from three generations) were infected with this poison (Martin 2012, 1). This is a deep wound from the past, and strengthening the bilateral relationship will not make much sense if the two countries do not focus on healing it.

Starting with Defense Secretary Cohen’s visit to Vietnam in March 2000, the US committed to closer cooperation with Vietnam on the Agent Orange issue. In November 2000, on the occasion of President Clinton’s visit to Vietnam, the two sides agreed to establish a joint research center on the effects of Agent Orange/dioxin (Nguyễn Đức Toàn 2016, 68–69). In March 2002 the first Vietnam-US scientific conference on Agent Orange/dioxin was held in Hanoi, with the participation of hundreds of researchers from the two countries. A memorandum of understanding was later signed between Vietnam and the US, in which the two countries agreed to cooperate in research on human health and future environmental effects from Agent Orange/dioxin as well as establish an advisory council to monitor the progress of cooperation.

In the following years, the US became more concerned about dealing with the consequences of Agent Orange/dioxin. In fact, it made practical contributions with financial support packages through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the War Victims Fund. In May 2007, US Congress approved a budget of nearly US$3 million to deal with the consequences of dioxin poisoning—related health care and medical services—at the military base in Da Nang (which was used by the US as a distribution center for Agent Orange during the war) (Martin 2012). In addition, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Atlantic Philanthropies foundation funded a US$6 million laboratory in Vietnam to enable high-resolution dioxin analysis. From 2008 to 2012, three USAID partners—East Meets West, Save the Children, and Vietnam Assistance for the Handicapped—provided medical, rehabilitation, and employment support to more than eleven thousand people with disabilities in Da Nang (Nguyễn Đức Toàn 2016, 70), regardless of the cause of disability.

Along with supporting Agent Orange victims, the US is interested in environmental cleanup activities in the airport areas that used to be US air bases during the war. In June 2012, USAID spent US$8.34 million on executing a contract to manage and monitor pollution treatment projects in Da Nang (Manyin 2014). Later, in July 2013, the US pledged to continue spending US$84 million on environmental cleanup projects at airports (Nguyễn Đức Toàn 2016). After completing pollution treatment at Da Nang airport in 2017, the two countries promoted similar work at Bien Hoa airport. According to Vietnamese media, the US committed US$300 million for restoring the environment at Bien Hoa airport and surrounding areas (Tuổi Trẻ 2019). The project was expected to be completed in ten years and has entered phase 1 after the Air Defense–Air Force (Ministry of National Defense of Vietnam) handed over 37 hectares of airport land (Pacer Ivy area) to USAID. According to the agreement signed between USAID and Vietnam’s Ministry of National Defense, phase 1 will last five years, with US$183 million in funding from the US (USAID 2019). The US efforts to clean up the environment in airfields that used to be wartime air bases as well as to support Agent Orange victims have greatly contributed to healing war wounds. This has helped the two countries move toward a good relationship.

The search for missing soldiers, especially missing American soldiers, from the Vietnam War is also one of the outstanding activities of US-Vietnam defense diplomacy. If the United States’ efforts with regard to Agent Orange/dioxin show its acknowledgment of responsibility for the painful wounds that it caused in the Vietnam battlefield, when it comes to searching for missing Americans Vietnam’s cooperation highlights the friendly spirit of a peace-loving country. No matter what each country’s perspective, the goodwill on both sides has contributed to bridging the gap and healing the relationship between the governments and peoples of the two countries.

According to the US State Department, as of November 12, 2010, there were still 1,711 Americans missing in Southeast Asia, of which 1,310 were in Vietnam (US Embassy & Consulate in Vietnam 2020). As of 2015, Vietnam had returned 945 sets of remains of US soldiers and identified seven hundred (Dương Thúy Hiền 2015). From the reverse direction, the US also supports the search for Vietnamese people missing in the war. In September 2010, USAID and Vietnam’s Ministry of Labour, Invalids, and Social Affairs agreed on a two-year program under which the US contributed US$1 million to help Vietnam locate thousands of its soldiers missing from the war. Thanks to financial resources and information provided by the US, Vietnam has found nearly one thousand cases (there are still about three hundred thousand Vietnamese soldiers missing) (Dương Thúy Hiền 2015). Speaking in Vietnam in November 2019, US Defense Secretary Esper reaffirmed the US commitment to solving the MIA problem; he also presented a map of a burial site on a battlefield provided by a US Marine veteran who had fought in the war (VOV 2019).

In addition to searching for missing soldiers, the US is cooperating with Vietnam to implement mine clearance projects under the Investigation, Survey, Assessment of Toxic Effects of Bombs and Mines and Explosives Left Over from the War program. Using mine detectors and personal protective equipment supplied by the US, the program has identified three thousand mine-affected areas, cleared 1,354 hectares of land, and removed twenty-five thousand pieces of unexploded ordnance (UXO) (Nguyễn Thị Hằng 2011, 48). Since 1993, the US has contributed more than US$154 million toward efforts related to UXO in Vietnam, including surveys and demining activities, information management, risk education, victim support, and capacity building for the Vietnam National Mine Action Center (US, Bureau of Political-Military Affairs 2020).

The US also pledged to support Vietnam with funding for landmine and coastal demining projects in 2016–20 and providing resources to carry out scientific and technological research and development programs in mine remedial work in 2016–25 (Lương Văn Mạnh 2017, 9). The long war of resistance against the French and the Americans from 1858 to 1975 has led to the land of Vietnam, even in peacetime, being threatened by explosives left over from the war—mainly UXO, including ball bombs. Demining is therefore an activity of practical significance, helping Vietnamese people stabilize their lives. The cooperation of the United States with Vietnam in detecting and removing UXO has contributed significantly to the development of substantive bilateral relations between the two countries.

II Challenges from Russia-Ukraine War

II-1 Vietnam’s Perspective on the War

The war (which Russia calls a “special military operation”) between Russia and Ukraine, which began in February 2022, has posed new challenges to international relations. Although Russia’s main reason for attacking was its perception of being threatened by NATO’s eastward expansion and Ukraine’s determination to join the military bloc, which was marked by East-West confrontation during the Cold War, its aggression was strongly condemned by the international community, especially Western countries. A wide range of sanctions targeting Russian individuals, banks, businesses, currency exchanges, bank transfers, exports, and imports were imposed. The United Nations General Assembly so far has adopted seven resolutions related to the Ukraine war. The first resolution (March 2, 2022) condemned the “aggression by the Russian Federation against Ukraine” and called on Russia to immediately withdraw from Ukraine. The second resolution (March 24, 2022) called on Russia to end its special military operation in Ukraine and called on the international community to increase humanitarian aid to Ukraine. The third resolution (April 7, 2022) called for suspending Russia’s membership in the UN Human Rights Council. The fourth resolution (October 12, 2022) urged countries not to recognize Russia’s annexation of four Ukrainian territories. The fifth resolution (November 14, 2022) required Russia to pay reparations for Ukraine, the sixth resolution (February 23, 2023)—on the first anniversary of Russia’s invasion—called for an immediate end to the war in Ukraine, while the seventh one (July 11, 2024) demanded Russia to “urgently withdraw troops and other unauthorized personnel” from Ukraine’s Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant. Vietnam abstained from voting on six of the resolutions (the first two and the last four) and voted against the third resolution.

Vietnam’s voting behavior on the United Nations General Assembly resolutions reflects its consistent foreign policy mindset—that is, the spirit of independence, peace, and respect for international law rather than taking sides. In fact, Vietnam has always maintained independence and consistency in its foreign policy, and from the very beginning it has made its point of view clear through a series of statements by state leaders. Ambassador Dang Hoang Giang, head of the Permanent Delegation of Vietnam to the UN, emphasized:

Vietnam calls on relevant parties to de-escalate tensions, resume dialogues and negotiations through all channels, in order to reach a lasting solution that takes into account the interests and concerns of all parties, on basis of international law, especially the principle of sovereignty and territorial integrity of states. (VOV 2022)

Vietnamese Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Le Thi Thu Hang also affirmed:

Vietnam’s current priority is to exercise maximum restraint, stop the use of force to avoid causing civilian casualties and loss, and resume negotiations on all channels to reach lasting solutions taking into account the legitimate interests of all parties, in accordance with the Charter of the UN and the fundamental principles of international law. (Vũ Văn Tự 2022)

Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh, during his visit to the US on May 11, 2022, once again emphasized that Vietnam firmly adhered to a foreign policy of independence and self-reliance, choosing justice instead of choosing sides (TTXVN 2022). Obviously, the message in these statements was that Vietnam opposed the war, stood for international law, and stood for justice—through which means Vietnam would support any party or point of view that had legitimacy. The fact that no specific country was named to support or condemn (as some countries expected) in Vietnam’s view of the Ukraine war was just a clever strategy to avoid going against the policy of not siding with one party to oppose the other and non-interference in the internal affairs of other countries. In terms of security and defense, Vietnam has transparently persisted in implementing the “Four Nos” policy,9) in which, except for the fourth “No”—no using force or threatening to use force in international relations—the remaining three “Nos” all represent Vietnam’s avoidance of choosing sides. Having been a victim of wars of aggression, Vietnam understands the terrible and persistent long-lasting consequences of war; therefore, it never wants to suffer a war and never wants to engage in war with any other country. Vietnam has also paid a heavy price for choosing sides in the past, so it understands the pain of being interfered with and losing its independence and self-control. Hence, its foreign policy prioritizes independence and self-reliance, persistently fighting to resolve all disputes and disagreements by peaceful means, on the basis of international law. Thus, in the context of the conflict between Russia and Ukraine, Vietnam relies on international law—the ground of “rightness”—to consider, recognize, evaluate, speak, and act. Certainly in the case of the Ukraine war, some would argue that standing on the side of “rightness” means being on the side of Ukraine. However, siding with Ukraine contradicts Vietnam’s stance of not siding with one side to fight the other; this is why Vietnam upholds the principle of standing for what is right, what is in accordance with international law.

Vietnam’s six abstentions and one vote against the resolutions of the UN General Assembly fully express this point of view. Obviously, these resolutions all carry the implication of an alignment of nations against Russia—a form of choosing sides that Vietnam has persistently avoided. Vietnam’s abstentions are thus consistent with its foreign policy as analyzed. As for the vote against the third resolution, which concerns the expulsion of Russia from the UN Human Rights Council, Vietnam also acted in the spirit of international law and independence. The basis for this against-vote, as Ambassador Dang Hoang Giang emphasized, was that exchanges and decisions of international agencies and organizations need to comply with their operational processes and procedures. All discussions and decisions of the UN General Assembly should be based on verifiable, objective, and transparent information, with the cooperation of relevant stakeholders and in broad consultation with countries. Originally this resolution was issued on the basis of accusations that Russia had carried out a “civilian massacre” in the town of Bucha, though Russia denied the allegation and said that it was a staged incident (Marchant de Abreu 2022). It was therefore entirely reasonable for Vietnam to want an independent UN investigation before making a decision. Its against-vote was in that spirit, not in favor of Russia or in the spirit of being dominated by any country. This behavior also shows that in its foreign relations, Vietnam is independent rather than neutral in a way that does not distinguish between right and wrong or stand on the sidelines. That response is clearly consistent with international law as well as with Vietnam’s long-standing foreign policy.

It must be admitted that Vietnam’s behavior in relation to the Ukraine war was also influenced by other geopolitical factors. Vietnam’s dependence on the Russian defense industry does not allow it to react too strongly. The dispute between Vietnam and China in the South China Sea also adds an incentive for Vietnam to think carefully in this regard. Russia remains an important factor in Vietnam’s multilateral policy. It is not in Vietnam’s interest to see Russia weakened and/or made dependent on China, and it is definitely not in its interest to provoke Russian retribution. In other words, Vietnam had interests grounded in realpolitik that prevented it from supporting the seven UN General Assembly resolutions.

II-2 Challenges from the Ukraine War

Despite such a clear point of view, Vietnam’s response to the Russia-Ukraine war still causes subjective inferences—based mainly on the history of the Vietnam-Soviet alliance—thereby creating challenges for Vietnam’s relations with other countries, including the United States.

The first challenge is Vietnam’s difficulty building strategic trust with the US. “Strategic trust” can be understood as sincere trust between parties, for the strategic benefit of the two (or more) parties. Strategic trust is of particular interest in Vietnam-US relations because both countries were once enemies in a large-scale armed war—the Vietnam War, which was also seen as a typical proxy war of the Soviet-American confrontation and beyond, an ideological confrontation between the socialist and capitalist blocs during the Cold War. Since then, the relationship between Vietnam and the US has grown tremendously in the spirit of respecting differences. However, with different political institutions, strategic trust is needed by both sides to overcome doubts from the past. With the positive gestures from both nations in recent years, the prospect of strategic trust being built between Vietnam and the US is very promising. However, the Russia-Ukraine war has created uncertainty for this outlook.

Russia-Ukraine relations were strained by Ukraine’s desire to join NATO, which was created during the Cold War by the US with the main purpose of providing security against the Soviet Union. As a result, the Russia-Ukraine war represents not only the conflict between Russia and Ukraine but also the conflicts of Russia with Europe and the United States. Meanwhile, Vietnam used to be an ally of the Soviet Union and has had close relations with Russia since 1991. This makes it easy for many Western countries to believe that Vietnam supports Russia. The fact that Vietnam abstained six times and once voted against the resolutions of the UN General Assembly only strengthened this view. Due to the nature of Vietnam-Russia relations and the historical conflict between Russia and the West, such Vietnamese action is likely to be misinterpreted, causing “unnecessary noise,” even creating doubts regarding Vietnam’s perspective on the situation in Ukraine (Lao Động 2022) and thereby affecting the prospects of good Vietnam-US relations. This argument became even more convincing in May 2022, when the United States, Canada, Australia, and a number of European countries signed an article calling on countries outside Europe, including Vietnam, to speak out against Russia’s violations of human rights and international humanitarian law10) (US Embassy & Consulate in Vietnam 2022).

The historical tensions between Vietnam and the United States remain a crucial element of the bilateral relationship. The contrast between their political systems offers a valuable perspective to examine their past conflicts whenever relevant opportunities appear. And the war in Ukraine has the potential to create that opportunity. The closeness of Vietnam-Russia relations and the tension between Russia and the United States are reminiscent of the triangular relationship between the Soviet Union, Vietnam, and the United States during the Vietnam War. Because the Soviet Union used to be Vietnam’s main supporter against the US, during the Russia-Ukraine war it is difficult for conservatives in the US Congress to avoid the perception that Vietnam supports Russia. Vietnam’s independent foreign policy has put it in a position of being innocent but having the evidence stacked against it, as illustrated by the controversial case of six abstentions and one negative vote in the United Nations General Assembly.

From another perspective, the United States’ suspicion of Vietnam against the background of the Ukraine war may potentially affect Vietnam’s faith in the US commitment to bilateral relations. In the final year of the Trump administration, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and other high-ranking officials launched an anti-Chinese Communist Party crusade. This was aimed directly at China, and the criticisms did not cause concern for Vietnam as it perceived them as part of the US-China trade war. However, the West’s suspicion of Vietnam choosing Russia after the outbreak of the Ukraine war could potentially raise anxiety for Vietnam; US criticism of the Chinese Communist Party could potentially be extended to the Communist Party of Vietnam, especially when China is building a close relationship with Russia. Thus, the Ukraine war may make it more difficult for Vietnam and the US to build strategic trust. Vietnam’s apprehension surrounding “peaceful evolution,” which was previously directed mainly toward the US, gradually shifted toward China. Now there is a concern that this fear may resurface and once again be directed toward the United States.11) This will affect the prospects of improved Vietnam-US relations, especially when it comes to joint diplomatic and defense activities.

The second challenge is the possibility that the war between Russia and Ukraine will change the foreign policy trajectory of the US, reducing the latter’s focus on the Indo-Pacific region and thereby impacting the growth momentum of US-Vietnam relations. Undeniably, the Russia-Ukraine conflict has to some extent diverted the world’s attention away from the Indo-Pacific region. This war serves as a reminder of the Russian threat to the US and Europe, and it has become a catalyst for NATO to regroup and reaffirm its value after a period of disagreement caused by disparities among the contributions by its members as well as the existential goals of the alliance. The NATO summit in June 2022 introduced a new Strategic Concept in which, for the first time in more than ten years, NATO officially changed its stance toward Russia, moving from viewing it as a “strategic partner” (in the 2010 Strategic Concept) to seeing it as “the biggest, the most direct threat”—although it still insisted it did not seek confrontation with Russia (NATO 2022). Russia’s special military operation in Ukraine has led member states toward greater consensus in defining the “Russian threat.” Meanwhile, China has also become a formal subject for the first time in NATO’s Strategic Concept and is seen as a lasting “systemic challenge” to the union. Obviously, NATO members are interested in the risks posed by both Russia and China. However, unlike the US, which wants stronger words and actions against China, its traditional allies (France and Germany) want NATO’s words and actions to have “more moderation” (Shalal and Pamuk 2022). The prime minister of Belgium (where NATO is headquartered), Alexander De Croo, on June 27, 2022 warned: “we will not want to turn our backs on China as completely as we have turned our backs on Russia” (Zhang and Wan 2022). The US had to compromise with other NATO members and acknowledge Russia rather than China as the primary threat. As a result, as part of its NATO responsibilities, the US must allocate resources to counter the Russian threat rather than focusing solely on China. In addition, as the EU has to deal with security problems caused by the Ukraine war, the US is also experiencing difficulty mobilizing power from its allies for its Indo-Pacific strategy. This has affected the prospects for Vietnam-US cooperation, causing anxiety in Vietnam that the US will reduce its focus on the Indo-Pacific region.

The third challenge after the outbreak of the Ukraine war is that future Vietnam-Russia cooperation may become a hindrance to US-Vietnam cooperation. Vietnam is faced with a dilemma: it has to be careful about buying Russian weapons, because of sanctions from the West; but on the other hand, it is unable to find a suitable alternative source of supply. Russia is currently the second-largest arms supplier in the world and an important source of weapons for China, India, and Vietnam. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, between 2000 and 2019 Russia sold 10.7 billion euros’ worth of defense equipment to Southeast Asian countries, 61 percent of which was exported to Vietnam (Wezeman 2019, 14–15). Since 2000, nearly 80 percent of Vietnam’s military equipment has been supplied by Russia. Although Vietnam’s expenditure on arms procurements from Russia decreased from US$1.054 billion in 2014 to US$72 million in 2021 (SIPRI 2023),12) during 2017–21 Vietnam was the world’s fifth-largest importer of Russian weapons (after India, China, Egypt, and Algeria) and the largest in Southeast Asia.13)

Meanwhile, in 2017 US Congress passed the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA), which imposes sanctions against countries that buy Russian weapons. To date, the United States has applied CAATSA only to China and Turkey, both of which purchased the S-400 surface-to-air missile system from Russia. In the case of Vietnam, the United States continues to turn a blind eye, due to the former’s important role in the Indo-Pacific region as well as the increasingly close strategic relationship between the two countries. Given Vietnam’s geostrategic location and rising status, its military buildup also contributes to the United States’ interest in preventing China’s expansion in the region. From the US perspective, it would be better for Vietnam to buy Russian weapons than to buy Chinese weapons. Also, since the Ukraine war has raised concerns about the prospect of China imitating Russia to use force against Taiwan and in the South China Sea, the US needs to keep good relations with Vietnam more than ever.

However, the close relationship between Hanoi and Moscow continues to embarrass the US. Although the US wants to build a strategic partnership with Vietnam, it holds CAATSA as a key tool for punishing Russia (through sanctioning Russian defense companies and disrupting Russia’s arms sales by threatening countries that buy Russian weapons). Vietnam-Russia cooperation is therefore likely to “affect US expectations to make Vietnam a strategic partner in the Indo-Pacific region” (Carl Thayer, quoted in Hutt 2022). According to Carl Thayer (2018), in 2018 defense officials from the Trump administration pressed Vietnam to reduce its dependence on Russian weapons and military technology. Washington lobbied Hanoi to buy American weapons instead. The problem is that although the US lifted the arms embargo against Vietnam in May 2016, its weapons remain unaffordable for Vietnam. Vietnam’s military modernization has slowed down since 2016, with tighter budgets making it even harder for the country to buy expensive Western weapons. Vietnam’s spending on weapons purchases dropped from US$603 million in 2018 to US$95 million in 2022 (SIPRI 2023). Moreover, Vietnam is familiar with Russian/Soviet weapons systems as well as doing business with Russian partners, which would make it difficult for it to change suppliers if forced to.

It is clear that although the US has so far turned a blind eye to Vietnam’s buying of Russian weapons, Vietnam’s continuation of military relations with Russia in the current context is a sensitive subject. This might be the reason that Vietnam’s participation in the 2022 Army Games14) was interpreted by some as a further indication of its “choosing Russia” (Thayer 2022). In this context, Vietnam’s continuing cooperation with Russia needs to be carefully calculated and take into account the US reaction.

It should be noted that Vietnam is engaged in efforts to modernize its national defense, a plan that was already in progress prior to the outbreak of the Ukraine conflict, as indicated at both the 11th All-Army Party Congress in 2020 (Quân đội nhân dân 2020) and the 13th National Party Congress in 2021 (Vũ Cương Quyết 2021). However, given Vietnam’s reliance on Russian weaponry, any change must be gradual, and Vietnam will require Russia’s assistance to upgrade its current equipment. This situation also creates an opportunity for Vietnam to engage in defense trade with the United States. If the US can establish trust and handle the matter delicately (taking into account Vietnam’s need to balance its relationship with China), it could accelerate the modernization of Vietnam’s national defense. In fact, following the conclusion of the Vietnam International Defense Expo in 2022, several American defense contractors held discussions with officials from the Ministry of National Defense. This could potentially pave the way for a more substantial defense cooperation partnership between Vietnam and the US.

Conclusion

In conclusion, defense diplomacy between Vietnam and the US has taken place in nearly all areas of defense relations. In the beginning, the two countries focused on less sensitive issues such as English training and dealing with the aftermath of the Vietnam War. Following the growth of the bilateral relationship, in the context of increasing regional security challenges, Vietnam and the US have actively coordinated as well as jointly established and joined defense cooperation mechanisms at a higher and more diverse level. The current mechanisms are a solid foundation for the prospects of Vietnam-US relations in general and defense diplomacy in particular. However, the Ukraine war is likely to pose some challenges to that good outlook. Due to the historical Vietnam-Russia relationship and the traditional Russian-Western confrontation, Vietnam’s Russia-related foreign activities—regardless of their consistency with Vietnam’s long-standing foreign policy direction—are likely to be misinterpreted, thereby affecting the development of Vietnam-US relations. The building of strategic trust between the two countries is also challenged with the Ukraine war creating a situation that overlaps in many aspects with the Vietnam War period (the closeness of Vietnam-Soviet/Russia relations and the Russia-US confrontation).

Nevertheless, it can still be affirmed that the growth momentum of US-Vietnam relations in general and the defense diplomacy of the two countries remain unchanged. After all, the strategic interests of the US and Vietnam in the bilateral relationship are still important enough for the two countries to overcome temporary roadblocks. With the increasingly fierce US-China competition, Vietnam is a valuable partner for the US due to its geostrategic position, the history of Vietnam-China relations, and the current status of disputes between Vietnam and China in the South China Sea. On the Vietnamese side, the US plays a leading role in its balancing policy. Of all the major powers that are Vietnam’s partners at the comprehensive level (comprehensive partnership) or higher, only the US has a fully comprehensive and positive relationship with Vietnam. The US is also the country with the greatest motivation and the highest ability to counterbalance China’s power. This role of the US becomes more and more meaningful to Vietnam with China’s increasing assertiveness in the South China Sea.

Dealing with a scheming China—which also understands Vietnam well—requires Vietnam to be more flexible in its strategy of responding to China. Vietnam’s upgrading and transition from a “Three Nos” to a “Four Nos”15) policy in 2019 showed its flexibility. Moreover, Vietnam also publicly explained in the 2019 National Defense White Paper:

[D]epending on the development of the situation and specific conditions, Vietnam will consider developing necessary defense and military relations to an appropriate extent, based on mutual respect for each other’s independence, sovereignty, territorial integrity, as well as fundamental principles of international law. This cooperation will be mutually beneficial, serving the common interests of the region and the international community. (Vietnam, Ministry of National Defense 2019, 25)

This interpretation can be extended to mean that, depending on China’s further actions, Vietnam may have appropriate defense solutions and, under necessary conditions, may further cooperate on security with the US. These factors are a solid premise to affirm the good prospects of Vietnam-US defense diplomacy.

Accepted: June 27, 2023

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author declares no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

Anh Sơn. 2021. Tàu tuần tra Mỹ John Midgett treo cờ Việt Nam, chuẩn bị bàn giao [US John Midgett coast guard ship flies the Vietnamese flag, preparing for handover]. Thanh Niên. February 8. https://thanhnien.vn/the-gioi/tau-tuan-tra-my-john-midgett-treo-co-viet-nam-chuan-bi-ban-giao-1339925.html, accessed April 27, 2023.↩

Army Recognition. 2022. Nimitz-Class Aircraft Carrier USS Ronald Reagan to Visit Vietnam. Army Recognition. July 5. https://www.armyrecognition.com/news/navy-news/2022/nimitz-class-aircraft-carrier-uss-ronald-reagan-to-visit-vietnam, accessed May 27, 2024.↩

Bộ Quốc phòng. 2004. Quốc phòng Việt Nam những năm đầu thế kỷ XXI [Vietnam national defence in the early years of the twenty-first century]. Hà Nội: Thế Giới Publisher.↩

Cheyre, Juan Emilio. 2013. Defence Diplomacy. In The Oxford Handbook of Modern Diplomacy, edited by Andrew F. Cooper, Jorge Heine, and Ramesh Thakur. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199588862.013.0021.↩ ↩

DAU. 2023. DAU Glossary. Defense Acquisition University. https://www.dau.edu/glossary/defense-cooperation, accessed May 17, 2024.↩

Delegation of the European Union to Vietnam. 2022. Op-Ed by the Ambassadors of the European Union, Norway, Switzerland and the United Kingdom in Hanoi. Delegation of the European Union to Vietnam. March 8. https://www.eeas.europa.eu/delegations/vietnam/op-ed-ambassadors-european-union-norway-switzerland-and-united-kingdom-hanoi_en?s=184, accessed April 27, 2023.↩

Drab, Lech. 2018. Defence Diplomacy: An Important Tool for the Implementation of Foreign Policy and Security of the State. Security and Defence Quarterly 20(3): 57–71. https://doi.org/10.5604/01.3001.0012.5152.↩

Dương Thúy Hiền. 2015. Hợp tác quốc phòng, an ninh Việt – Mỹ sau 20 năm bình thường hóa quan hệ [Vietnam – United States defense and security cooperation after twenty years of normalizing relations]. Quan hệ Quốc phòng, No. 29, quý I/2015.↩ ↩

Fleurant, Aude; Wezeman, Pieter D.; Wezeman, Siemon T.; Nan Tian; and Kuimova, Alexandra. 2018. Trends in International Arms Transfers, 2017. Stockholm: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.↩

Government of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. 2023. Quan hệ kinh tế-thương mại-đầu tư Việt-Mỹ nhiều tiềm năng phát triển [Vietnam-US economic-trade-investment relations have great potential for development]. Báo Điện tử Chính phủ. September 9. https://baochinhphu.vn/quan-he-kinh-te-viet-my-nhung-diem-nhan-noi-bat-102230904162103725.htm, accessed May 27, 2024↩

―. 2021. Đối ngoại quốc phòng là một trọng tâm của ba trụ cột đối ngoại [Defense diplomacy is a focus of the three foreign policy pillars]. Báo Điện tử Chính phủ. December 14. https://baochinhphu.vn/doi-ngoai-quoc-phong-la-mot-trong-tam-cua-ba-tru-cot-doi-ngoai-102305500.htm, accessed April 27, 2023.↩

Hoàng Đình Nhàn. 2017. Đối ngoại quốc phòng Việt Nam đầu thế kỷ XXI đến nay [Vietnam’s defense diplomacy from the beginning of the twenty-first century to the present]. PhD dissertation, Diplomatic Academy of Vietnam. https://static.dav.edu.vn/images/upload/2017/09/Tom%20tat%20Luan%20an%20Hoang%20Dinh%20Nhan.pdf, accessed May 27, 2024.↩

Hong-Kong Nguyen and Pham-Muoi Nguyen. 2022. It Takes Two to Tango: Vietnam-US Relations in the New Context. Fulcrum. June 8. https://fulcrum.sg/it-takes-two-to-tango-vietnam-us-relations-in-the-new-context/, accessed April 27, 2023.↩

Hutt, David. 2022. Russia-Vietnam Ties Put US in a Sanctions Dilemma. AsiaTimes. April 21. https://asiatimes.com/2022/04/russia-vietnam-ties-put-us-in-a-sanctions-dilemma/, accessed April 27, 2023.↩

Jaishankar, Dhruva. 2016. India’s Military Diplomacy. GMF (German Marshall Fund of the United States). http://www.gmfus.org/sites/default/files/Military_Layout_Final-1.20-26.pdf, accessed August 27, 2023.↩

Jordan, C.; Stern, M.; and Lohman, W. 2012. U.S.-Vietnam Defense Relations: Investing in Strategic Alignment. Backgrounder, No. 2707.↩

Lao Động. 2022. Sự ‘ồn ào’ không đáng có [The ‘noise’ is not worth it]. Lao Động. March 7. https://laodong.vn/thoi-su/su-on-ao-khong-dang-co-1020842.ldo, accessed April 27, 2023.↩

Lương Văn Mạnh. 2017. Việt Nam nỗ lực khắc phục hậu quả bom mìn sau chiến tranh: vai trò của quân đội [Vietnam’s efforts to overcome the consequences of landmines after the war: the role of the military]. Quan hệ Quốc phòng, No. 37.↩

Manyin, Mark E. 2014. U.S.-Vietnam Relations in 2014: Current Issues and Implications for U.S. Policy. CRS Report, Congressional Research Service. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/R40208.pdf, accessed August 27, 2023.↩

Marchant de Abreu, Catalina. 2022. Debunking Russian Claims that Bucha Killings Are Staged. France 24. April 4. https://www.france24.com/en/tv-shows/truth-or-fake/20220404-debunking-russian-claims-that-bucha-killings-are-staged, accessed April 27, 2023.↩

MarineLink. 2011. MSC Ship: First USN Ship Visit to Vietnam Port in 38 Years. MarineLink. August 23. https://www.marinelink.com/news/vietnam-first-visit340094, accessed April 27, 2023.↩

Martin, Michael F. 2012. Vietnamese Victims of Agent Orange and U.S.-Vietnam Relations. CRS Report, Congressional Research Service. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/RL34761.pdf, accessed August 27, 2023.↩ ↩

NATO. 2022. NATO 2022 Strategic Concept: Adopted by Heads of State and Government at the NATO Summit in Madrid. NATO. https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2022/6/pdf/290622-strategic-concept.pdf, accessed August 27, 2023.↩

New Challenges to Defence Diplomacy. 1999. Strategic Survey 100(1): 38–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/04597239908461108.↩

Nguyễn Đức Toàn. 2016. Hợp tác Việt Nam – Hoa Kỳ về quốc phòng và giải quyết vấn đề ‘di sản’ chiến tranh Việt Nam từ năm 1995 đến nay [Vietnam-US cooperation on defense and resolving the “legacy” issue of the Vietnam War from 1995 to the present]. Lý luận chính trị No. 2/2016: 65–72. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

Nguyễn Mại. 2008. Quan hệ Việt Nam – Hoa Kỳ hướng về phía trước [Vietnam-US relations moving forward]. Hà Nội: Tri thức Publisher.↩

Nguyễn Thị Hằng. 2011. Thực trạng mối quan hệ Việt Nam – Mỹ [Current status of Vietnam-US relations]. Quan hệ Quốc phòng, No. 16.↩

Nguyễn Thị Huệ. 2023. Đối ngoại quốc phòng – Bảo vệ Tổ quốc xã hội chủ nghĩa từ sớm, từ xa [Defense diplomacy: Defending the fatherland early, from afar]. Tạp chí Cộng sản. January 6. https://www.tapchicongsan.org.vn/web/guest/quoc-phong-an-ninh-oi-ngoai1/-/2018/826935/doi-ngoai-quoc-phong—bao-ve-to-quoc-xa-hoi-chu-nghia-tu-som%2C-tu-xa.aspx, accessed April 27, 2023.↩

Pham Thi Yen. 2021. Strategic Use of Cam Ranh Bay in Vietnam’s External Relations with Major Powers. Strategic Analysis 45(1): 38–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/09700161.2020.1870270.↩

Pháp luật. 2019. Tập trận ASEAN-Mỹ khác gì tập trận ASEAN-Trung Quốc? [What is the difference between the ASEAN-US joint military exercises and the ASEAN-China exercises?]. Pháp luật. https://plo.vn/quoc-te/chuyen-gia/tap-tran-aseanmy-khac-gi-tap-tran-aseantrung-quoc-857253.html, accessed April 27, 2023.↩

Quân đội nhân dân. 2020. Khai mạc trọng thể Đại hội Đại biểu Đảng bộ Quân đội lần thứ XI, nhiệm kỳ 2020-2025 [The opening ceremony of the 11th Congress of the Military Party Committee, term 2020–2025]. Quân đội nhân dân. September 28. https://www.qdnd.vn/chinh-tri/dua-nghi-quyet-cua-dang-vao-cuoc-song/tin-tuc/khai-mac-trong-the-dai-hoi-dai-bieu-dang-bo-quan-doi-lan-thu-xi-nhiem-ky-2020-2025-636288, accessed April 27, 2023.↩

Shalal, Andrea and Pamuk, Humeyra. 2022. “Systemic Challenge” or Worse? NATO Members Wrangle over How to Treat China. Reuters. June 27. https://www.reuters.com/world/china/systemic-challenge-or-worse-nato-members-wrangle-over-how-treat-china-2022-06-27/, accessed April 27, 2023.↩

SIPRI. 2023. SIPRI Arms Transfers Database. SIPRI. https://armstrade.sipri.org/armstrade/html/export_values.php, accessed April 27, 2023.↩ ↩

―. n.d. Importer/Exporter TIV Tables. SIPRI. https://www.sipri.org/databases/armstransfers, accessed May 17, 2024.↩

Storey, Ian. 2021. Russia’s Defence Diplomacy in Southeast Asia: A Tenuous Lead in Arms Sales but Lagging in Other Areas. ISEAS. March 18. https://www.iseas.edu.sg/articles-commentaries/iseas-perspective/2021-33-russias-defence-diplomacy-in-southeast-asia-a-tenuous-lead-in-arms-sales-but-lagging-in-other-areas-by-ian-storey/, accessed April 27, 2023.↩ ↩

Tạp chí Quốc phòng toàn dân [National Defense Journal]. 2011. Sách trắng Quốc phòng Việt Nam 2009 – sự thể hiện nhất quán chính sách quốc phòng tự vệ vì hoà bình, hợp tác và phát triển [Vietnam National Defense White Paper 2009: a consistent expression of the defense policy of self-defense for peace, cooperation, and development]. Tạp chí Quốc phòng toàn dân. https://mod.gov.vn/en/intro/detail/!ut/p/z1/tVI9b4MwEP0tGTpa52IoMJKhiaKoatMQghfkDyBuwUCxSPvvi9OhUyAd6uXuSe_87t4dUDgC1WxQJTOq0awacUofssfoaRcs7yOM91sHvyzdgxeGPnFDH5IpwmpDgN5Sj6-8CM_VH4ACFdq05gRp3cg73DM0RtQrk19A1w7aJplNMtF37S_qjUXSCbEkjCOPewy5IiSIE-wgXzhcBkXBhcBWphVKQnoTO5nzjU5PnVi9iR_W_jTh4vycSDo26V-VeCaQDCo_Q6ybj3q8hdc_erDGsAFaVg3_OST11nU0GrfVaJN_Gjj-57raOo7rgHyh911w3henqlwsvgGFsm_N/, accessed May 27, 2024↩

Thayer, Carl. 2022. Is Vietnam Going to Hold a Military Exercise with Russia? Diplomat. April 27. https://thediplomat.com/2022/04/is-vietnam-going-to-hold-a-military-exercise-with-russia/, accessed April 27, 2023.↩

―. 2018. U.S. Defense Secretary to Visit Vietnam – 2. Thayer Consultancy Background Brief. October 15. https://fr.scribd.com/document/390890911/Thayer-U-S-Defense-Secretary-to-Visit-Vietnam-2, accessed April 27, 2023.↩

Trần Đức Tiến and Lưu Mạnh Hùng. 2022. Bộ mặt mới của chiến lược “diễn biến hòa bình” trong cục diện thế giới hiện nay [The new face of the “peaceful evolution” strategy in the current world situation]. Tạp chí Cộng sản [Communist review]. February 9. https://tapchicongsan.org.vn/web/guest/dau-tranh-phan-bac-cac-luan-dieu-sai-trai-thu-dich/chi-tiet/-/asset_publisher/YqSB2JpnYto9/content/bo-mat-moi-cua-chien-luoc-dien-bien-hoa-binh-trong-cuc-dien-the-gioi-hien-nay, accessed April 27, 2023.↩

Trúc Huỳnh and Yến My. 2021. Việt Nam sẽ được chuyển giao tàu tuần tra lớp Hamilton cuối cùng của Mỹ? [Vietnam will be delivered the last US Hamilton coast guard ship?]. Thanh Niên. March 9. https://thanhnien.vn/viet-nam-se-duoc-chuyen-giao-tau-tuan-tra-lop-hamilton-cuoi-cung-cua-my-post1253584.html, accessed April 27, 2023.↩

TTXVN. 2022. Toàn văn bài phát biểu của Thủ tướng Phạm Minh Chính tại CSIS Hoa Kỳ [Full text of Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh’s speech at CSIS (US)]. TTXVN. May 12. https://www.vietnamplus.vn/toan-van-bai-phat-bieu-cua-thu-tuong-pham-minh-chinh-tai-csis-hoa-ky/789684.vnp, accessed April 27, 2023.↩

Tuổi Trẻ. 2019. 300 triệu USD xử lý dioxin ở sân bay Biên Hòa [US$300 million for dioxin remediation at Bien Hoa airport]. Tuổi Trẻ. December 6. https://tuoitre.vn/300-trieu-usd-xu-ly-dioxin-o-san-bay-bien-hoa-20191205222527411.htm, accessed April 27, 2023.↩

―. 2011. Việt Nam – Hoa Kỳ ký ghi nhớ hợp tác quốc phòng [Vietnam-US signed memorandum of understanding on defense cooperation]. Tuổi Trẻ. September 21. https://tuoitre.vn/viet-nam—hoa-ky-ky-ghi-nho-hop-tac-quoc-phong-456792.htm, accessed April 27, 2023.↩

Tuoi Tre News. 2022. US to Deliver 12 Brand-New Military Training Aircraft to Vietnam. Tuoi Tre News. December 10. https://tuoitrenews.vn/news/politics/20221210/us-to-deliver-12-brandnew-military-training-aircraft-to-vietnam/70416.html, accessed April 27, 2023.↩

US, Bureau of Political-Military Affairs. 2020. U.S. Security Cooperation with Vietnam. Bureau of Political-Military Affairs. July 27. https://2017-2021.state.gov/u-s-security-cooperation-with-vietnam-2/index.html, accessed April 27, 2023.↩ ↩

US Department of Defense. 2019. Contracts for May 31, 2019. U.S. Department of Defense. https://www.defense.gov/News/Contracts/contract/article/1863144/, accessed April 27, 2023.↩

US Department of State. 2013. Expanded U.S. Assistance for Maritime Capacity Building. U.S. Department of State. December 16. https://2009-2017.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2013/218735.htm, accessed April 27, 2023.↩

US Embassy & Consulate in Vietnam. 2022. Joint Article by 24 Diplomatic Missions in Vietnam about the OSCE’s Independent Investigation. U.S. Embassy & Consulate in Vietnam. May 4. https://vn.usembassy.gov/joint-article-by-24-diplomatic-missions-in-vietnam-about-the-osces-independent-investigation/, accessed April 27, 2023.↩

―. 2020. Quan hệ Hoa Kỳ – Việt Nam [US-Vietnam relations]. U.S. Embassy & Consulate in Vietnam. https://vn.usembassy.gov/vi/u-s-vietnam-relations/, accessed May 17, 2024.↩

USAID. 2019. Tờ thông tin: Xử lý ô nhiễm dioxin tại sân bay Đà Nẵng và khu vực sân bay Biên Hòa [Fact sheet: Dioxin Remediation at Da Nang airport and Bien Hoa airbase area]. USAID. December 3. https://2017-2020.usaid.gov/vi/vietnam/documents/fact-sheet-dioxin-remediation-danang-airport-and-bien-hoa-airbase-area-vi, accessed May 17, 2024.↩

Vietnam, Ministry of National Defense. 2019. 2019 Vietnam National Defense. Hanoi: National Political Publishing House.↩ ↩ ↩

VOV. 2022. Toàn văn tuyên bố của Việt Nam tại Đại hội đồng LHQ về tình hình Ukraine [Full text of Statement of Vietnam at the UN General Assembly on the situation in Ukraine]. VOV. March 2. https://vov.vn/chinh-tri/toan-van-tuyen-bo-cua-viet-nam-tai-dai-hoi-dong-lhq-ve-tinh-hinh-ukraine-post927707.vov, accessed April 27, 2023.↩

―. 2019. Mark Esper Secretary’s Visit Highlights Strong US – Vietnam Partnership. Đảng bộ Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh. VOV. November 22. https://english.vov.vn/en/politics/mark-esper-secretarys-visit-highlights-strong-us-vietnam-partnership-406526.vov, accessed May 17, 2024.↩ ↩ ↩

Vũ Cương Quyết. 2021. Xây dựng Quân đội tinh, gọn, mạnh theo Nghị quyết Đại hội XIII của Đảng [Building an elite, compact, and strong army according to the resolution of the 13th Party Congress]. Tạp chí Quốc phòng toàn dân. July 22.↩

Vũ Văn Tự. 2022. Bác bỏ luận điệu xuyên tạc, suy diễn quan điểm của Việt nam về vấn đề xung đột giữa Nga – Ukraine [Rejecting distorted allegations of Vietnam’s perspective on the conflict between Russia and Ukraine]. Tạp chí Quốc phòng toàn dân. May 26. http://tapchiqptd.vn/vi/phong-chong-dbhb-tu-dien-bien-tu-chuyen-hoa/bac-bo-luan-dieu-xuyen-tac-suy-dien-quan-diem-cua-viet-nam-ve-van-de-xung-dot-giua-nga-ukraine/18754.html, accessed April 27, 2023.↩

Wezeman, Siemon T. 2019. Arms Flows to Southeast Asia, pp. 14–15. Stockholm: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.↩

Zhang Hui and Wan Hengyi. 2022. NATO Summit to Show Unity amid Deeper Cracks. Global Times. June 29. https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202206/1269286.shtml, accessed April 27, 2023.↩

1) This was the Cam Ranh International Port, which is a purely civilian-run enterprise—distinct from the military base at Cam Ranh Bay, which was used by the United States and Soviet Union/Russian Federation.

2) During the nearly four months from July 3, 2019 to October 24, 2019, the Chinese ship Haiyang Dizhi 8 entered and left Vietnam’s waters four times.

3) From 2003 to 2016, there were about twenty visits by US warships to Vietnam’s seaports (see Hoàng 2017, 75).

4) The US invited Vietnam to participate in RIMPAC 2020, but due to the Covid-19 pandemic Vietnam and many other countries did not attend. Other ASEAN countries that have participated in this activity are Thailand, the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and Brunei. China participated twice in RIMPAC—in 2014 and 2016; since 2018, the US has not invited China to attend.

5) In 2018, 2019, and 2020.

6) Even though the training area is located in the Gulf of Thailand and offshore of Ca Mau (Vietnam), a location that is relatively far from the hotly disputed areas of the South China Sea, the exercise did not include any drills involving significant combat simulations.

7) Before the exercise with the US in September 2019, ASEAN held three exercises with China: (1) in July 2018, some ASEAN countries and China held a maritime exercise at Changi Naval Base (Singapore); (2) in October 2018, six ASEAN countries and China held joint maritime exercises in the waters of Zhanjiang City, Guangdong Province (China); (3) an exercise between ASEAN (ten member countries) and China took place in April 2019, in Qingdao (China) (see Pháp luật 2019).

8) In the Vietnam Coast Guard, the Morgenthau is called CSB-8020.