Contents>> Vol. 13, No. 2

Transformations of Anisong Manuscripts in Luang Prabang: Application of Modern Printing Technologies*

Silpsupa Jaengsawang**

*The research for this article was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy–EXC 2176 “Understanding Written Artefacts: Material, Interaction and Transmission in Manuscript Cultures,” project no. 390893796. The research was conducted within the scope of the Centre for the Study of Manuscript Cultures (CSMC) at Universität Hamburg.

**Centre for the Study of Manuscript Cultures (CSMC), Universität Hamburg, Warburgstraße 26, 20354 Hamburg, Germany

e-mail: silpsupa.jaengsawang[at]uni-hamburg.de

![]() https://orcid.org/0009-0006-3284-3936

https://orcid.org/0009-0006-3284-3936

DOI: 10.20495/seas.13.2_343

Printing technologies that arrived in Laos with French colonialism (1893–1945) facilitated the Lao manuscript culture by introducing new writing tools and writing support. When storing and categorizing manuscripts in a repository, librarians began using new technologies such as writing tools and paper labels as well as the Roman alphabet to encode pronunciations for vernacular titles of anisong manuscripts. Monk-preachers began using pen to correct sermonic texts written on palm leaves. Affiliation markers in the precolonial as well as colonial periods were written mostly in the modern script, since monastic lay assistants—who were sometimes responsible for transporting and storing manuscripts in the monastic library—were illiterate in the Dhamma script. Since the modern Lao script was available in modern printing machines, there was a gradual decrease in the use of the traditional Dhamma script. The modern Lao script was thus used to compensate for the dwindling knowledge of the Dhamma script and to accommodate those who could not read the traditional script but were still part of the manuscript culture.

Keywords: printing, transformation, Lao manuscripts, manuscript culture, anisong, colonialism

I Introduction

After King Saisetthathilat (1534–71) moved the capital of the Lao kingdom of Lan Sang from Siang Thòng to Vientiane in the mid-sixteenth century, Siang Thòng remained a center of Lao Buddhism.1) It was renamed Luang Prabang in honor of the Phra Bang statue, which had become Laos’s precious Buddha symbol. In the early eighteenth century Laos was split into three kingdoms: Luang Prabang, Vientiane, and Champasak. Each claimed to be the successor state of Lan Sang, and all were forced to recognize Siamese suzerainty in 1778. Following the failed uprising by King Anuvong of Vientiane in 1826–28 (in which Champasak—but not Luang Prabang—participated), Vientiane and Champasak became fully incorporated into the Siamese kingdom while Luang Prabang remained a vassal state. Hence, after 1893, when Siam ceded all territories on the left bank of the Mekong River to France, only Luang Prabang became a French protectorate while the rest of Laos became part of the French colony. This explains why Lao Buddhism was influenced by Siamese traditions even though Lao Buddhist practices depended upon local traditions (Khamvone 2015, 5). The French barely intervened in Buddhist activities in Luang Prabang, focusing instead on the restoration of Vientiane, which had been devastated by Siamese troops. Francis Garnier (1885, 286, cited in Ladwig 2018, 100) reported that the first French missions between 1866 and 1868 found Vientiane in ruins. Buddhist sermons were still part of daily life, which contributed to the commissioning of religious texts inscribed in palm-leaf manuscripts by laypeople. The Lao manuscript culture continued despite the French administration, which lasted approximately fifty years (1893–1945 with a brief interregnum in which Laos was a Japanese puppet state).2)

Western technologies were applied to Lao manuscript production from the late nineteenth century and resulted in, for instance, typewritten palm-leaf manuscripts unique to Luang Prabang. The existence of several typewritten copies of palm-leaf manuscripts suggests an effort to preserve religious texts, particularly under the manuscript-copying projects led by Sathu Nyai Khamchan Virachitto (1920–2007).3) While religious texts recorded in the manuscripts were preserved using this new method, Dhamma script literacy4) gradually declined as typewriters had the modern Lao script.5) In the late twentieth century, manuscripts written in the Lao variant of the Dhamma script could only be produced by hand, on mulberry and industrial paper.6)

Inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in December 1995, the town of Luang Prabang has a long religious and political history, with a mixture of indigenous and European—notably French—cultures.7) The use of palm leaf, mulberry paper, and industrial paper was steadily associated with new printing technologies that arrived there in the late nineteenth century. This article discusses manuscript transformations due to the application of new technologies in Luang Prabang. It also touches on the purposes behind and the results from encounters with modernity in Lao manuscript culture in the late nineteenth century. This study argues that French colonialism had a greater influence on the Lao manuscript culture than any other factor. After providing general information on the Lao manuscript culture and anisong manuscripts, this paper outlines the social and cultural setting of Luang Prabang in the late nineteenth century. The manuscripts discussed date from the French colonial period to the present. The use of new printing technologies is discussed next. The four key factors heuristic tool and paracontent are the core methodologies applied in this study.

Note on Quotations from Manuscripts

Since the manuscripts used as primary sources for this research were written in either the Dhamma or the modern Lao script, quotations are necessarily presented differently. Those from manuscripts written/typewritten in the modern Lao script are simply presented in that script, while texts written in Lao Dhamma (i.e., the Lao variant of the Dhamma script) have been transcribed into the modern Thai script, largely preserving the orthography of the original. Thus, readers familiar with modern Thai might better apprehend the English translations. I consider this approach—despite its shortcomings—more appropriate than transcribing the text into modern Lao (due to the script’s limited number of consonants) or using a Lao Dhamma font.

II General Information on Anisong Manuscripts

The impact of French colonialism on Lao Buddhist manuscript culture along with technological innovations in writing and composition is manifold. Some genres of texts reveal more nuanced perspectives on the changes than others. Anisong manuscripts’ popularity, their position in the manuscript corpus as a whole, and their social relevance and ritualistic use are considered here. This previously under-researched genre of Lao Buddhist texts deals with the rewards obtained from meritorious deeds.

In the Buddhist social context, where meritorious benefits derived from praiseworthy activities are hard to measure, concrete manifestations referring particularly to the Buddha matter. The liturgical culture of delivering anisong sermons has been passed down for centuries. The ritual of delivering these sermons assures practitioners of blissful consequences acquired through religious ceremonies and rituals and assures them that no meritorious deed goes unrewarded:

The outcomes and effects of this ritual engagement are people broadly subsumed under one notion—merit—in Lao called boun (from Pali puñña). Any ritual event conducted in temples is first and foremost labelled boun, which besides religious merit then refers to the event itself, also in the sense of a collective party. (Ladwig 2021, 26–27)

Anisong is the Lao (and Thai) pronunciation of the Pali word ānisaṃsa, meaning “rewards,” “benefits,” “advantages,” or “results of positive deeds” corresponding to puñña in Pali. Anisong also represents a textual genre and a type of sermon declaring the benefits derived from meritorious acts.

Another terminological alternative for anisong sermons/texts is the Khmer word sòng or its variant salòng. Sòng or salòng (chlòng ឆ្លង, ສອງ/ສະຫຼອງ), corresponding to chalòng (ฉลอง, “to celebrate”) in Thai, is a derivative of the Khmer verb chlòng, meaning “to cross,” “to inaugurate,” “to dedicate,” “to celebrate,” and “to spread” (Grabowsky 2017, 416). The sermons are called salòng or thet salòng (ເທດສະຫຼອງ) in Laos and anisong sermons or thet anisong (เทศน์อานิสงส์) in the historical region of Lan Na, in Thailand’s north. The term anisong (Th: thet anisong เทศน์อานิสงส์) in Northern Thailand signifies “the announcement of rewards,” while salòng or sòng (Lao: thet salòng ເທດສະຫຼອງ) in Laos signifies “the announcement of completion”:

Anisong is derived from Pali ānisaṃsa which means “benefit, advantage, good result.” In the Buddhist context Anisong or Salòng (Lao, from Khmer: chlaṅ, “to dedicate,” “to celebrate”)—often contrasted to Sòng—are used for homiletic purposes, such as performing sermons and preaching. Those texts, generally rather short (rarely containing more than twenty folios), describe the rewards in terms of merit, or literally the “advantage” which a believer may expect from a particular religious deed. (Grabowsky 2017, 416)

Sometimes salòng is defined as “gratuity” or “benefits.” Silpsupa Jaengsawang (2022, 66–67) discusses a manuscript containing five texts (BAD-13-1-0157, 1944 CE)8) from Luang Prabang that was partly written with blue pen in the modern Lao script to introduce the Anisong hask sin sermon. In a colophon added later, salòng is defined as “gratuity” for one’s religious faith (ฉลองศรัทธา) and “benefits” (ประโยชน์) one may gain from merit-making or listening to the Dhamma. For the second case, instead of Anisong haksa sin or Salòng/Sòng haksa sin, the sermon title is Payot haeng kan haksa sin: the term anisong or salòng or sòng is replaced by payot haeng kan,9) meaning “benefits derived from the activity of.” Accordingly, the two mentions of salòng in the newly written introduction define anisong as “gratuity” and “benefits” resulting from meritorious deeds. The new introduction is quoted below, with the key words related to anisong/salòng/sòng underlined:

บัดนี้ จักแสดงพระธรรมเทศนา เพื่อสลองศรัทธา ประดับสติปัญญาของท่านสาธุชน ผู้มีกุศลจิตมาบำเพ็ญกุศลบุญราศีในพระพุทธศาสนา เพื่อสั่งสมบุญบารมีในตนให้หลายยิ่งขึ้นไป เพราะการเฮ็ดบุญไว้นี้ มีแต่เพิ่มพูนความสุขให้แก่ตนตลอดเวลา ตรงกันข้ามกับการเฮ็ดบาปหยาบช้า ยิ่งเฮ็ดหลาย ก็ยิ่งนำความทุกข์ลำบากให้แก่ตนทั้งในปัจจุบันและอนาคต พระธรรมเทศนาที่จะนำมาแสดงนี้มีชื่อว่า ประโยชน์แห่งการรักษาศีล ตามคาถาบาลีที่ได้อัญเชิญไว้เบื้องต้นว่า สีเลนะ สุคะติง ยันติ แปลความว่า บุคคลจะไปสู่สุคติ ก็เพราะมีศีลเป็นที่รักษา จะได้โภคสมบัติมาก็เพราะมีศีล จะมีวาสนาถึงพระนิพพานก็เพราะมีศีลเป็นหลักปฏิบัติ Now the Dhamma sermon will be delivered as remuneration for your religious faith (gratuity) in order to promote the wisdom of devotees (you) who virtuously make merit for Buddhism for the purpose of higher meritorious accumulation; because merit-making always increases happiness. [Merit-making] is contrary to sinful deeds; [namely,] the more sinful deeds one does, the more grief one experiences in both present and future times. The following Dhamma sermon is titled Benefits of Precept Observance, which is in accordance with the introductory Pali expression as sīlena sugatiṃ yanti, [literally] meaning “With precept observance, one is destined to rest in peace.” Property and enlightenment are also derived from the following precepts. (BAP, code: BAD-13-1-0157, folio 8 [recto], Vat Saen Sukharam, Luang Prabang, 1944 CE)

Titles of anisong texts in Lao manuscripts are mostly preceded by the word salòng or sòng: for example, Salòng cedi sai (Rewards derived from [building] sand stupas), Sòng fang tham (Rewards derived from listening to the Dhamma), Salòng khamphi (Rewards derived from copying religious books). Thet salòng or salòng sermons are apparently associated with “dedicating” and “celebrating,” because they are delivered to mark a completion of merit-making—to acknowledge, celebrate, and value donors’ meritorious deeds: “The public act of lauding itself is in Laos called saloong (‘to celebrate the outcome of the meritorious deed’) and the donors have variously been described as having prestige or being worthy of veneration” (Ladwig 2008, 91).

In a sermonic ritual the monk usually holds an anisong manuscript while reading the text. However, sometimes monks improvise an anisong sermon or recite one by heart while holding another type of manuscript. An anisong sermon is delivered during or after a merit-making activity in a monastery’s main ordination hall,10) at a layperson’s house where a meritorious event is held, or even outdoors where a monastic object donated by local people has been installed (Silpsupa 2022, 103–106). The sermon is delivered in public and therefore “witnessed” by all participants, especially by the preaching monk who approves the successful merit and delivers the sermon to explain or “affirm” the forthcoming rewards.

Anisong liturgical texts have been copied and transmitted on several kinds of writing support, from palm-leaf manuscripts to mulberry paper and industrial paper. The earliest dated Lao anisong manuscript is titled Salòng paeng pham (Rewards derived from the construction of pavilions) and is from Attapü Province. The manuscript, made of palm leaves, was written in 1652 (DLLM, code: 17010106001-11). The most recent Lao anisong manuscript, dated 2016, is made of industrial paper (a blank notebook). Titled Anisong lai pae fai (Rewards derived from the donation of light floating vessels), it is from Luang Prabang (DREAMSEA, code: DS 0056 00645). Compared to anisong manuscripts from Northern Thailand, those in Laos are made of a wider variety of writing support, writing tools and substances, and bookbinding materials, thanks to the advent of new printing technologies.

Anisong manuscripts have been found in many places in the Upper and Middle Mekong region—the Dhamma script’s cultural domain, which includes Northern Thailand, large parts of Northeastern Thailand, Laos, the eastern parts of Myanmar’s Shan State, and southwestern Yunnan. Luang Prabang has the most manuscripts in Laos because of its role as a center of Buddhist education, supported by royal patronage until 1975, and its monastic schools that were operated without French involvement or even the French language/curriculum. Most lay and ordained students in Laos studied at monastic schools (McDaniel 2008, 39). Luang Namtha Province, bordering China and Myanmar, has the greatest variety of writing support: palm leaf, mulberry paper, and industrial paper.

III Luang Prabang Manuscript Culture in the Late Nineteenth Century

Although the French were not literate in the Dhamma script, they were involved in the manuscript culture. In 1900–53, for instance, they collected manuscripts from monastic libraries in Luang Prabang, Vientiane, Champasak, and Khammuan and deposited them in royal offices, libraries, and central monasteries. In doing so, they were able to learn about Laos’s history and culture in their effort to colonize, consolidate the population, and monopolize power. Many manuscripts were never returned to their original monasteries (Bouakhay 2008, 62–63), and some ended up in unintended temples, as recorded in their colophons.11) French efforts to rule Laos through building a harmonious and religion-friendly environment included the revival and patronage of Buddhism, with scholars from the École française d’Extrême-Orient (French School of the Far East) becoming engaged in historical and textual studies of the religion (Ladwig 2018, 104).

French colonialists aimed to incorporate Laos into French Indochina in order to use Lao territory, economically and strategically, for increased access to Vietnam and China (Stuart-Fox 1995, 111–112). They supported the construction and renovation of religious buildings, including That Luang (Laos’s most important Buddhist relic shrine) and Vat Si Saket, because they realized the power of the sangha over Buddhist rulers and the emotional appeal of their actions for the Lao. This was a strategic colonial plan of initiating statecraft and moving from assimilation to association (Ladwig 2018). Thus, religious manuscripts continued to be produced and circulated among local monasteries.

The colonial period brought challenges for Buddhism, with Vientiane being destroyed by Siam in 1828, Luang Prabang having to pay tribute to Siam, and large parts of Laos coming under French rule (Khamvone 2015). But during this period Lao people reinforced their Buddhist identity. They commissioned a large number of manuscripts and promoted Lao as the national language, which caused considerable conflict during the 1940s between Lao elites, led by Cao Maha Uparat Petcharat, and French officials, led by Charles Rocher, the French director of public education in Vientiane. The Lao elites declined the French proposal to use the Roman alphabet for book printing, thus protecting the country’s writing tradition, inherited manuscripts, and indigenous customs. The Lao elites’ success against the French represented “intellectual liberation” from “intellectual colonization” (Bouakhay 2008, 74–75). At the opening ceremony for the newly rebuilt manuscript library in Vientiane, a head of the Lao sangha gave a speech referring to Lao manuscripts as “Dhamma” manuscripts written by the Lao, in order to clarify that the French were responsible merely for the building that housed the manuscripts, not for the production of the manuscripts (McDaniel 2008). Thus, the Lao accepted religious support from the French but under limited conditions.

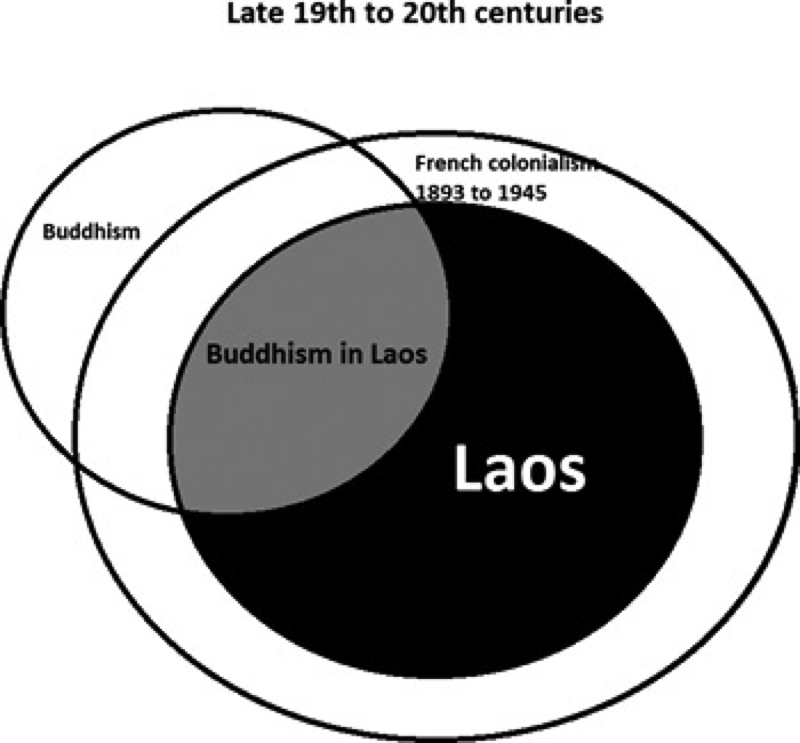

The French supported architectural innovation and the rebuilding of Buddhist monasteries (Ladwig 2018, 99). Fig. 1 illustrates the unique phenomenon of Lao Buddhism during colonial times. In the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries French colonialism spread over and outside Laos. As shown in the gray shaded area, Lao Buddhism featured a combination of French influences and indigenous beliefs. It was trapped by the positive and negative effects of colonialism and Western influence, thereby remaining in the “gray zone,” where indigenous traditions and a foreign power tolerated and negotiated with each other. Buddhism in other French colonies—represented by the white-colored parts of the diagram—had slightly different practices, depending on the people and history of the countries.

Fig. 1 Unique Situation of Buddhism in Laos during the French Colonial Period (1893–1945)

Source: Silpsupa Jaengsawang

In its half-century under French colonialism, Laos absorbed the influence of Western modernity on the local manuscript culture:

Anisong texts were also produced according to the traditional way of making manuscripts in the Buddhist circle of Luang Prabang. When the city was influenced by Western civilization in the twentieth century, it became possible for Buddhist scholars and scribes who had access to modern publications to employ modern techniques of writing for manuscript production. (Bounleuth and Grabowsky 2016, 250)

Typewriters were used to inscribe texts on palm leaf during 1960–90 by monks who had the required skills (Bounleuth 2016, 247).12) The sole surviving typewriter used for typing palm-leaf manuscripts, made of iron and weighing about 20 kg, is in the monastic library at Vat Suvanna Khili (Fig. 2). Characterized by the special length of the platen—26 cm—the typewriter, with its 29 cm roll, was suitable for typing palm-leaf manuscripts, which were generally longer than normal paper. A white piece of paper attached to the platen reads (in English): “This typewriter, Achan Khamvone brought it from the Buddhist primary school Vat Mano13) to the Buddhist Archive on 26 March 2014 for preservation.” “Achan Khamvone” or Dr Khamvone Boulyaphonh is the director of the Buddhist Archive of Luang Prabang, whose head office is in Vat Suvanna Khili. Partly hidden behind the white paper, the phrase “ຫ້ອງການສຶກສາ [room of education]” was lightly inked on the platen in the modern Lao script before the typewriter was moved to Vat Suvanna Khili.

Fig. 2 Typewriter for Typing Palm-Leaf Manuscripts (photo by Silpsupa Jaengsawang, Vat Suvanna Khili, Luang Prabang, August 24, 2022)

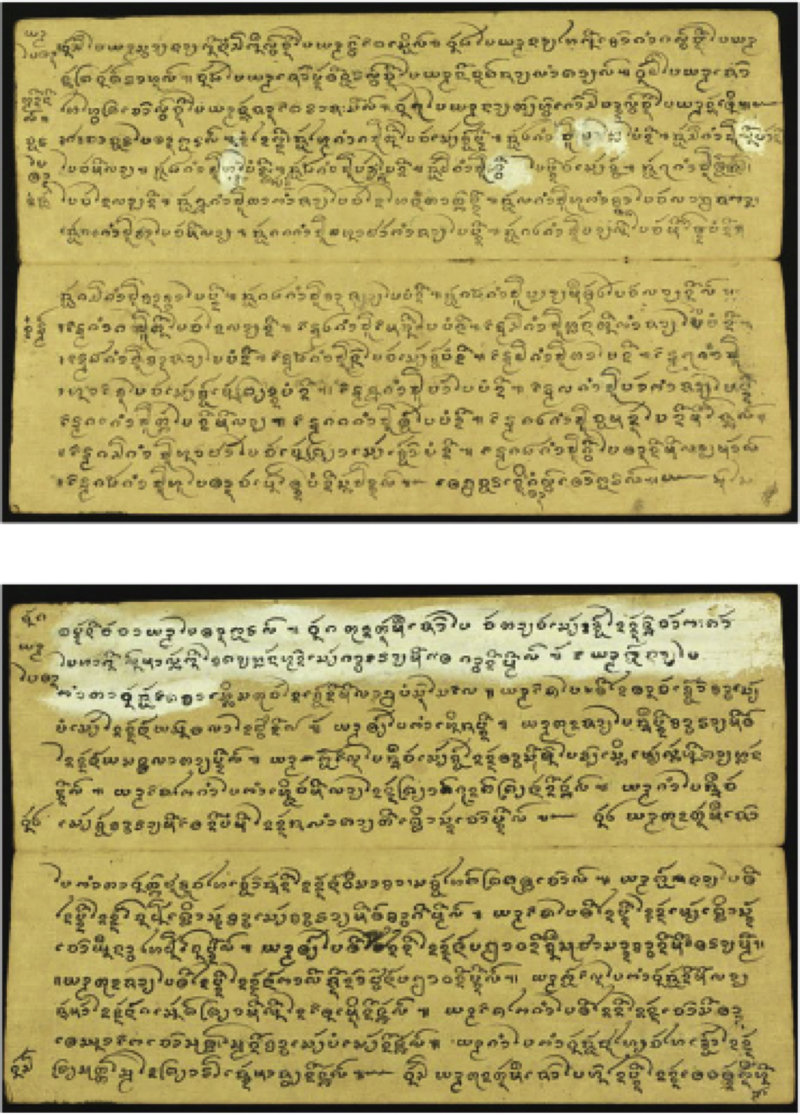

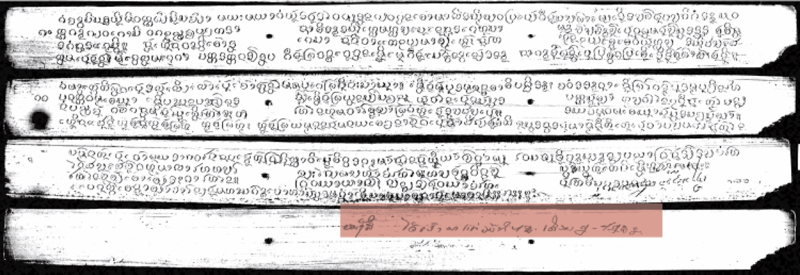

Because typewriters were used and donated among sangha communities in Luang Prabang monasteries, monks and novices were the only people who had access to them. Fig. 3 shows the first dated hybrid palm-leaf manuscript with handwritten and typewritten text (Silpsupa and Grabowsky 2023, 115). The manuscript is titled Panya barami (Rewards derived from following the Thirty Perfections). The colophon is newly typed, marking 2506 BE (1963 CE) as the year of production.

Fig. 3 Typewritten Colophon, Panya barami (Rewards Derived from Following the Thirty Perfections)

Source: Buddhist Archive of Photography (BAP), BAD-13-1-0760, Vat Saen Sukharam, Luang Prabang, 1963 CE

Not only were colophons written with a typewriter, in a number of palm-leaf manuscripts even texts were written with a typewriter. For example, a 1984 palm-leaf manuscript titled Anisong bun wan koet (Rewards derived from merit-making on birthdays) from Luang Prabang (see Fig. 4) was typed, though its cover folio was decoratively handwritten with blue and red ink. Typewritten manuscripts were produced under the Buddhist dissemination project of religious text preservation led by Sathu Nyai Khamchan Virachitto, the abbot of Vat Saen Sukharam. Between the 1940s and 1960s, he sponsored and donated hundreds of manuscripts to his monastery. He also asked monks (e.g., Sathu Phò Phan of Vat Hat Siao), novices, and laypeople to copy manuscript texts brought from neighboring countries (Khamvone 2015, 225). The availability of the modern Lao script on typewriters had two contrasting results: the decline of Dhamma script literacy and an increased accessibility to religious texts among non-Dhamma script communities. However, typewriters did not completely replace the Dhamma script—the latter was still used for handwriting texts and corrections and taking notes.

Fig. 4 Typewritten Manuscript Anisong bun wan koet (Rewards Derived from Merit-Making on Birthdays)

Source: Buddhist Archive of Photography (BAP), BAD-19-1-0137, Vat Siang Muan, Luang Prabang, 1984 CE

The tradition of dedicating religious books or manuscripts to a monastery preserved handwriting habits: sponsors wrote their own names, names of family members, and names of merit recipients—usually their dead relatives—in handwritten, typewritten, or even printed manuscripts. Modern printing technology can replace the process of transmitting texts, but the tradition of manuscript donation is irreplaceable (Silpsupa 2022, 173). The example in Fig. 4 is excerpted from the typewritten Anisong bun wan koet, made of palm leaves and aligned in three columns. Anisong manuscripts from Northern Thailand were less influenced by modern printing technologies and tend to preserve local traditional styles (Silpsupa 2022, 172).

White correction fluid is widely found in manuscripts from Luang Prabang; the earliest evidence of dated manuscripts applying correction fluid is Nangsü ha mü hai mü di (Book of calculation for [in]auspicious days). The manuscript, from 1908, is made of mulberry paper in the leporello style (see Fig. 5). White correction fluid is frequently used, and new text and corrections have been handwritten.

Fig. 5 Mulberry Paper Manuscript with White Correction Fluid: Nangsü ha mü hai mü di (Book of Calculation for [In]Auspicious Days)

Source: Buddhist Archive of Photography (BAP), BAD-13-2-042, Vat Saen Sukharam, Luang Prabang, 1908 CE

Easier accessibility to industrial paper was accompanied by the use of ballpoint pens, which were used on palm-leaf and mulberry paper manuscripts for corrections or even for writing text. Paper was bound in various ways: gluing and folding multiple sheets to form a concertina-like folded book, using metal staples to form a whirlwind book, or using strong string at the top margin. The last technique is similar to stab bookbinding.14) In many cases anisong manuscripts were written in blank school notebooks especially manufactured by Sawang Kanphim (Silpsupa 2022, 199–200). The notebooks are still in use and found in the library of Vat Ong Tü in Vientiane (Silpsupa 2022, 93). Since December 1975, when the Lao People’s Revolutionary Party came to power, anisong manuscripts have been less monitored by the government, due to a lack of Dhamma script literacy. Compared to the era of French colonialism, anisong manuscripts drastically decreased in number under the Lao People’s Revolutionary Party (Silpsupa 2022, 185–186), and religious activities were partly controlled and shaped according to Communist orientations: “Monks were constantly informed that Buddhism and socialism were congruent and complementary since both promoted equality, communal sharing, and the objective of ending suffering” (McDaniel 2008, 59).

One important case study was the collectivist religious event of building a temple in February 2019, hosted by a successful businesswoman in Vientiane (Ladwig 2021). Participants from different social backgrounds and both urban and rural areas made donations to join the construction campaign. However, the event seemed to have a business angle, because it included advertising and branding for a company. Merit was believed to be distributed among the participants, who treated one another as equals. However, in the end the businesswoman’s family name was inscribed on the new temple gate and the “artificial” space of a stratification-free collective ritual quickly evaporated (Ladwig 2021, 12–38). Such “invented” and romanticized egalitarian strategies allow feudalists to exploit and convince laypeople to donate their labor for religious pursuits in exchange for merit (Khamtan 1976, 18; Ladwig and Rathie 2020, cited in Ladwig 2021, 34). Phoumi Vongvichit, the minister of religion in Laos after the revolution, argued that the new Lao Buddhism should promote solidarity and donations should be given by people from all strata of society (Vongvichit 1995, cited in Ladwig 2021, 34–35).

IV Application of New Technologies to the Lao Manuscript Culture

Three Oxford University Press dictionaries give similar definitions of “technology”: the application of scientific knowledge for practical purposes (Wehmeier 2005, 1576–1577); developed machinery and equipment (Stevenson 2010, 1826); and a branch of applied science knowledge (Turnbull 2010, 1589–1590). In general, with the application of new technologies, the quality and quantity of products are improved, time taken is reduced, and human labor requirements are reduced. New printing technologies were initially beneficial to religion and education in Laos, as these fields employed such technologies the most (Hindman 1991, 3).

Thanks to the living tradition of anisong sermons, manuscripts have been revised by contemporary users for purposes ranging from aiding in chanting to updating the contents, improving some chanting words with respect to the audience, adding a new salutation, and even reproducing a new anisong manuscript for inexperienced preaching monks. Due to their active use, anisong manuscripts have been changed using modern tools—to the modern Lao script and foreign languages. The French arrival gave monks and novices access to new technologies, as explained in the context of Venerable Sathu Nyai Khamchan Virachitto’s manuscript collection:

Together with the manuscripts, a great number of various modern publications and printed materials—such as books, magazines, newspapers and documents—were found in Pha Khamchan’s abode. This indicates that the Venerable Abbot himself might have had access to different types of such modern publications. This may have been the case for the other monks, novices, and lay Buddhist scholars. Anyone who was able to write the Dhamma script on palm-leaf might use similar “modern” techniques in his writings. Not only did some anisong texts found in Pha Khamchan’s abode develop “modern” structures and contents, but the layout of such anisong manuscripts was influenced by features of modern printing technology as well. (Bounleuth 2015c, 259)

IV-1 Writing Tools, Writing Materials, and Modern Lao Script

Traditional palm-leaf manuscripts were inscribed with a stylus or pin-topped pencil. A dark substance such as lamp oil was applied on the inscribed surface to expose the textual traces engraved by the stylus. Ink, ballpoint pens, and pencils gradually came to be used not only in mulberry and industrial paper manuscripts but also in palm-leaf manuscripts. Additions and corrections often appear to have been made by ballpoint pen to avoid blurring by re-darkening processes.

White correction fluid was convenient and popular for deleting words and replacing them with new words written by pen or even typewriter.15) The author (Silpsupa 2022) has highlighted a remarkable example of new writing on a spot covered by white correction fluid in a palm-leaf manuscript titled Sòng Sapphathung (Rewards derived from the donation of all kinds of religious flags) (BAD-13-1-0387, 1910 CE). Correction fluid “concealed” the inscribed traces of mistakes, so that dark resin would not remain in the inscribed traces while the surface was being coated (Silpsupa 2022, 350–351).

Computer printing is the most recent technology for facilitating the production of anisong and non-anisong texts. One example of a hybrid printed-handwritten anisong manuscript is Anisong sang pha tai pidok (อานิสงส์สร้างพระไตรปิฎก Rewards derived from copying the Buddhist canon, n.d.). The manuscript is made of paper and was printed by computer, with three columns and a running head resembling the modern format of printed books. The manuscript cover was also produced by computer, with the logo of the institution and a decorative title. The names of sponsors and merit recipients are handwritten.

With typewriters and computer printers featuring the modern Lao script,16) this script replaced the Dhamma script, which could only be written by hand. In the late nineteenth century the Dhamma script was not widely installed in typing machines, although it was first used in the 1890s by the American Presbyterian Mission Press in Chiang Mai (Anonymous 1890, 115–116, cited in Dao 2022, 88). Modern and foreign characters could be used in Luang Prabang manuscripts due to Lao people’s exposure to foreign influences. Increasing numbers of anisong manuscripts were therefore produced with new kinds of writing machines, which allowed preaching monks who were newly ordained or less experienced in the Dhamma script as well as laypeople to use typed or printed manuscripts. Mass-produced manuscripts had blank spaces for adding personal details: sponsors’ names, recipients’ names, colophons, or wishes. Such handwritten entries made some manuscripts unique.17)

Colophons appear to include more entries in the modern Lao script than the main texts. According to Bounleuth Sengsoulin (2015c, 255), due to their short length—usually fewer than 15 folios—anisong manuscripts were popular for newly ordained monks and novices to practice reading and copying the Dhamma script. Apart from the model texts written in Pali, mostly in the Dhamma script, student monks were supposed to write colophons with various wishes18) and were sometimes allowed to write in the more familiar modern Lao script. Colophons are thus found in several scripts.

IV-2 Roman Alphabet and Foreign Languages

The Roman alphabet was most frequently used by librarians for categorizing and organizing manuscripts on shelves, especially in the case of anisong manuscripts at the National Library of Laos in Vientiane. Added in the first or second folio, the manuscript titles were spelled in the Roman script, with the Thai-Lao pronunciations provided. This was intended to help foreigners catalogue the manuscripts and shows the involvement of Westerners in Lao manuscript libraries. A striking example is the aforementioned case of the French gathering manuscripts for their own cultural and historical investigation into Laos along with other projects.19) According to Harald Hundius (2009), 3,678 manuscripts from 94 monasteries in nine provinces were surveyed by Lao and French scholars in 1970–73:

A notable initiative is the work of the Chanthabouly Buddhist Council, under the leadership of Chao Phetsarat, which asked abbots throughout the country to submit lists of their manuscript holdings between 1934 and 1936.

Work on the EFEO [École française d’Extrême-Orient] inventory, plus research and analysis of manuscripts, followed in the 1950s and 1960s by Henri Deydier, Pierre-Bernard Lafont, and Charles Archaimbault. An Inventaire des Manuscrits des Pagodes du Laos (Lafont 1965), building on the previous work of French scholars, was conducted under the leadership of Pierre-Bernard Lafont in 1959 and covered altogether 83 monasteries: 13 in Luang Prabang, 25 in Vientiane, and 45 in Champasak. (Hundius 2009, 21)

Not only did Western technology permeate the written language, but French words were also used in manuscripts from Luang Prabang. French words are written in the Dhamma script in modern Lao orthography and appear in the colophons of some anisong manuscripts (see Section V-1). Sathu Nyai Khamchan Virachitto headed several Buddhist missions and helped in the transmission of Buddhist texts from palm-leaf manuscripts. He was knowledgeable in French (Khamvone 2015, 46) as well as Lü and Pali (phone interview with Khamvone Boulyaphonh, August 31, 2023).

IV-3 Paper and Ink Stamps

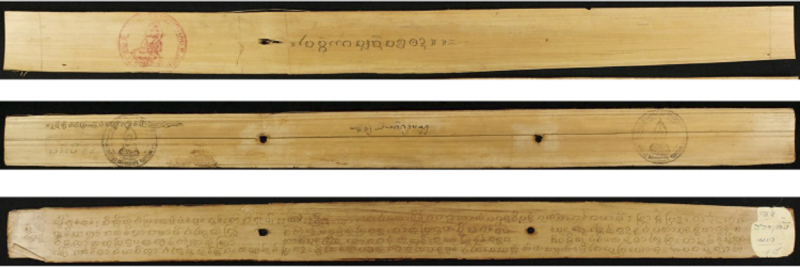

The most widespread use of new technologies was in the manufacture of labels: these were made of various new materials, including paper, glued paper (stickers), and ink stamps. Ready-to-use stickers were mass-produced in different shapes, indicating their popular usage and the development of the industrial paper business. Ink stamps were made of wood or rubber and engraved with institute logos. Red and blue were the most common ink colors. Fig. 6 shows examples from three palm-leaf manuscripts at the National Library; red and blue stamps appear in their first folios. The white label in the last picture is on the right-side margin that bears the beginning of the text. The label indicates the code “554,” the title Sòng thammat (Rewards derived from the donation of pulpits), and the number of fascicles—“1 fascicle”—in the bundle.

Fig. 6 Palm-Leaf Manuscripts with Inked Stamps and White Sticker

01012906004-05, n.d.: Salòng phasat phüng (Rewards Derived from the Donation of Beeswax Castles)

01012906005-01, 1901 CE: Salòng umong (Rewards Derived from the Construction of Chapels)

01012906006-07, n.d.: Sòng thammat (Rewards Derived from the Donation of Pulpits)

Source: Digital Library of Lao Manuscripts, National Library of Laos (n.d.)

V Manuscript Transformations in Luang Prabang

Anisong manuscripts appear to have been most strikingly influenced by new printing technologies, according to the survey by Bounleuth (2015c, 250) on manuscripts kept in the abode (kuti) of Pha Sathu Nyai Khamchan Virachitto. For instance, a palm-leaf manuscript titled Salòng khao phan kòn (Rewards derived from the donation of one thousand rice balls) (BAD-13-1-0685, 1985 CE) was written with a typewriter and ink; a palm-leaf manuscript titled Sòng pathip hüan fai (Rewards derived from the donation of light floating vessels) (BAD-13-1-0714, n.d.) was revised with ink by later users; the colophon of a palm-leaf manuscript titled Anisong katham bun taeng ngan (Rewards derived from merit-making at wedding ceremonies) (BAD-22-1-0899, 1997 CE) was written in blue ink. Blank school notebooks became popular for writing anisong manuscripts: for instance, Sòng pha nam fon (Rewards derived from the donation of monk robes in the rainy season) (DS 0056 00643, n.d.) and Anisong thung (Rewards derived from the donation of all kinds of religious flags) (DS 0056 00644, 2012 CE). Anisong preaching is a living tradition, and anisong manuscripts are still produced, with new technologies being adopted. The transformation of Luang Prabang’s manuscript culture is relevant for the following six purposes: production, librarians’ work, editions and revisions, affiliation and ownership statements, dedication rituals, and Buddhisization.

V-1 Production

New printing technologies are important for producing anisong manuscripts as both texts and objects. As mentioned above, the breakthrough project of manuscript reproduction led by Venerable Khamchan Virachitto in the late twentieth century was associated with modern printing. Anisong manuscripts came to be reproduced easily and quickly, in unlimited quantities. Printing houses manufactured paper, published books, produced blank notebooks, and printed manuscripts in the pothi shape20) using paper. Mulberry paper and industrial paper were popularly used for printing pothi-shaped leporello manuscripts known as lan thiam (ลานเทียม), literally, “artificial palm-leaf manuscripts” (they resembled traditional palm-leaf manuscripts). The manuscripts had blank spaces for filling in the names of manuscript donors (phu sang ผู้สร้าง) and deceased persons to whom the merit derived from donation was transferred. This practice reveals the surviving tradition of offering religious books to monasteries and the common belief in meritorious dedication to the dead. Traditions and beliefs remain alive even with the rise of modern printing technology (Silpsupa 2022, 116).

During my 2018 research trip to Phrae Province, I found lan thiam manuscripts at a supermarket near the provincial temple Wat Sung Men. The temple is known to be the largest repository of palm-leaf manuscripts. The manuscripts were, interestingly, placed near the bottom of the shelves, even though they were intended for donation to the monastery. I found that disrespectful because religious manuscripts are normally placed at an elevation. For the business owner, however, the manuscripts were simply commodities. Customers could buy them, write their names, and dedicate them to a monastery.

This case study reveals two dimensions of the transformation of manuscript culture. First, the relationships and statuses of manuscript commissioners and production agents21) have changed. Compared to the traditional commissioning and dedicating of anisong manuscripts to monasteries, “scribes” have become “factories” of printed or lan thiam manuscripts, and “sponsors” have become “customers.” The traditional merit-reciprocal relationship between scribes and sponsors has been replaced by a demand-supply or market-centered relationship, and the special aura that manuscripts take on in rituals has been weakened through the demand-supply circuit. Printed manuscripts are mass-produced and traded as normal products in the market; they are elevated to sacred objects only after being ritually dedicated to a monastery. Thus, spatial or environmental changes transform them from commercial products to sacred objects. The micro-settings22) of the two locations (supermarket and monastery) determine the role of the manuscript. A book is a carrier of two relationships: between the book and its makers, and the book and its readers (Davis 1975, 92, cited in Hindman 1991, 3). Books are thus characterized by commercial and social factors, corresponding to two broad approaches in the sociology of literature. This study explains that literature is concerned with man’s social world, his adaptation to it, and his desire to change it (Laurenson and Swingewood 1972, 12) and that literature exists in its own sociology. The first and more popular approach adopts the documentary aspect of literature, arguing that it provides a mirror of the age. The second approach emphasizes the production aspect, especially the social situation of the writer (Laurenson and Swingewood 1972, 7–17).

Figs. 7 and 8 show hybrid productions combining new technologies (typewriters and computer printers) with handwriting.

Fig. 7 Hybrid Typewritten-Handwritten Manuscript

Salòng khao phan kòn (Rewards Derived from the Donation of One Thousand Rice Balls)

Source: Buddhist Archive of Photography (BAP), BAD-13-1-0685 (1985 CE), Vat Saen Sukharam, Luang Prabang

Fig. 8 Hybrid Printed-Handwritten Manuscript Anisong sang pra tai pidok (Rewards Derived from Copying the Buddhist Canon)

Source: Buddhist Archive of Photography (BAP), BAD-13-2-033 (n.d.), Vat Saen Sukharam, Luang Prabang

The cover folio, containing the manuscript title, is handwritten in modern black ink to resemble printed books in which titles tend to be enlarged and aligned in the middle. The title is flanked on the left by the usage purpose, “Anisong liturgical text for religious merit-making occasions,” and on the right by the sponsor and his affiliation, “Pha Khamchan Virachitta Thera, affiliated with Vat Saen Sukharam in Luang Prabang.” The title folio is handwritten in the modern Lao script, like the text, which is typewritten in that script. The text is set in three columns to be read sequentially rather than in one column as in the case of handwritten palm-leaf manuscripts. The title and foliation orders are typewritten vertically on the left margins of the recto sides (black box, Fig. 7), influenced by the modern templates of printed books. This is different from handwritten palm-leaf manuscripts, in which foliation is generally on the verso side.

The manuscript in Fig. 8 is made of paper and computer-printed in the modern Lao script. The first picture shows a small paper cover for holding the manuscript in order, while the second shows the cover page. On the cover page the centralized title is enlarged and curved, followed by a statement showing the usage purpose: “[this manuscript text is] for liturgical uses on great merit-making occasions and at other special events.” There are emblems in the left and right margins: the left one is a Buddha image in a locket-like frame; the right one is the national emblem of the Lao Kingdom, a triple-headed elephant under a tiered umbrella.23) The left-side emblem is identical to that on the paper cover, which is flanked by the title (left) and source of text (right).

The third picture shows the beginning of the text, which is—unlike in handwritten palm-leaf manuscripts—preceded by a colophon. The colophon dominates the first page and has blank spaces to be filled in with sponsors’ names (two boxes in the third element) (ທອງວັນ ສຸຕະພົມ ພ້ອມຄອບຄົວ ແລະລູກທຸກຄົນ ຢູ່ສະຫະຮັຖອະເມຮິກາ ຮັຖຄາລີຟໍເນັຽ ທີ່ເມືອງຢູ່ນຽນ Thòngwan Sutaphrom and his/her family who live in Union City, California in the US) and merit recipients’ names (ແມ່ຊື່ສາວຄຳພັນ His/her mother named Khamphan). Providing a colophon at the beginning of the manuscript allows a recipient monk to navigate the names of sponsors to be announced in dedicational rituals, which is traditionally followed by a water-pouring act (kruat nam)24) (see Silpsupa 2022, 351). The tradition of writing colophons at the end of the main text was perhaps unfamiliar among laypeople because monks and novices were mostly responsible for manuscript production and therefore knew where the colophons were. Colophons at the end of the text could be unintentionally overlooked, and manuscript donors could miss filling in their names. Hence, placing the colophon at the beginning made the donation act more visible—future readers and users could see the sponsors’ names at first glance.

In the last picture of Fig. 8 the box in the last element shows the names of those who participated in the manuscript’s production by composing the text from other sources (Master Monk Suwat Paphaso), transcribing and translating the text into the Lao language and script (Monk Wòn Varapañño), and printing and checking the manuscript (Khampòn Phothirat). While the work of the production team (scribal task) is shown through printing, the work of the dedication team (sponsoring task) is shown through handwriting, which eventually results in a codex unicum and creates an original. Dedicated manuscripts can thus be donated individually to one monastery. As the scribal tasks in this case included translation and consultation of other sources, this printed manuscript was not merely a copy like traditional handwritten manuscripts. Rather, the production team adapted the text in order to serve market demand. Such a scribal practice is somewhat innovative and leads to language change: “Observing language change over time, we can see that scribes are both active agents of change but also have a more passive role when—perhaps unknowingly and unintentionally—documenting variation or developmental tendencies and patterns in language” (Wagner et al. 2013, 3).

Because computerization allows for the production of several copies, many people besides sponsors and scribes are involved in textual corrections and visual design, as shown by the list of people and their tasks in Fig. 8. Traditional manuscripts require precision and writing expertise from monks, while modern manuscripts require skillful typing and proofreading from lay technicians. The collaboration between sangha and laity is similar to the commissioning of handwritten palm-leaf manuscripts, though experts are required for more elaborate tasks:

By changing their work and their writing, it [print] forced the writer, the scholar, and the teacher—the standard literary roles—to redefine themselves, and if it did not entirely create it, it noticeably increased the importance and the number of critics, editors, bibliographers, and literary historians. (Kernan 1987, 4)

French text occasionally shows up in colophons. The scribe of the manuscripts in Fig. 9 was a monk named Phui Thiracitto (ผุย ถิระจิตโต),25) who sponsored Anisong bun wan koet, the aforementioned anisong palm-leaf manuscript typewritten by a monk named Cinna Thammo (จินนะธัมโม).26) Thiracitto was familiar with commissioning typewritten palm-leaf manuscripts and with other modern—namely, French—influences. Fig. 9 shows the colophons of three handwritten manuscripts, with French words for years and months.

Fig. 9 Manuscripts with French Words in Colophons

(Top) BAD-22-1-0910, 1968 CE: Sòng cedi (Rewards Derived from the Construction of Pagodas)

(Middle) BAD-22-1-0934, 1967 CE: Salòng hò pha (Rewards Derived from the Donation of Cloth)

(Bottom) BAD-22-1-0936, 1968 CE: Sòng cedi (Rewards Derived from the Construction of Pagodas)

Source: Buddhist Archive of Photography (BAP), Vat Maha That, Luang Prabang

The three French month names, in the boxes in each element, are written in the Dhamma script and orthography and indicate the pronunciations of nowòn (novembre), chòngwiye (janvier), and desòm (décembre). In the first picture nowòn is in parentheses, followed by the vernacular term “November,” while the French words in the next two pictures replace the vernacular words for January and December, implying that the monastic scribal community was familiar with the French language—or even French people. Venerable Khamchan Virachitto’s personal letters contain both English and French words: “They (i.e., personal letters) were written in various languages such as Lao, Thai, English and French, and in various scripts such as old Lao (pre-1975), modern Lao (post-1975), Tham-Lao, Thai, and Latin” (Khamvone 2015, 161). The use of French shows communications and interrelationships between the Lao and the French, as well as French influences on Laos, especially on Lao manuscript culture:

It is not unusual for scribes to mix the orthographic systems (Lao: labop akkhalavithi or lak khian thuai) of both scripts, and in some instances, we find idiosyncrasies, reflecting particular multi-lingual and multi-ethnic cultural environments the scribes were exposed to. (Bounleuth and Grabowsky 2016, 7)

V-2 Librarians’ Tasks

Librarians used new technologies for identifying and cataloguing manuscripts in archival storage. Individual fascicles of anisong manuscripts are identified by their titles, codes, and textual genre labels with inked stamps and paper stickers. These identifiers were added after the manuscripts were moved from their original repositories to be restored at the National Library, where they were catalogued and digitized for online access. Roman numerals and the Latin alphabet were used for the titles, revealing the participation of Westerners in librarians’ work.

When the National Library (Fig. 10) was made a repository of manuscripts, categorization aids were devised to indicate textual genres, mark dates of manuscript acquisition, identify fascicle orders, and add tables of contents. Cataloguing facilitates the digitization of manuscripts. Begun in January 2012, digitization was completed through collaboration with the University of Passau and Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin Preußischer Kulturbesitz and funded by the German Research Foundation and German Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development (National Library of Laos, n.d.). With manuscripts sourced from several repositories, the National Library required international financial and collaborative support to systematize registration codes, shelves, and online access. Coding phrases newly written on the manuscript pages or on glued white paper have different handwriting styles, scripts, and languages.

Fig. 10 Manuscript Bookshelves in the National Library of Laos (photo by Silpsupa Jaengsawang, March 15, 2017)

Fig. 11 shows a round paper sticker made and attached by a librarian on the verso side of the last folio for cataloguing purposes. On it in blue ink is written “206” (code), Sòng thung lek (manuscript title), and “1 fascicle” (number of fascicles). The numbers 206 and 1 are written in Roman numerals and the words Sòng thung lek and fascicle in the modern Lao script. Instead of the Dhamma script, which was understood by only a limited group, librarians used the modern script and Roman numerals. Through the use of a non-Dhamma script and modern writing/printing materials, anisong manuscripts written in the Dhamma script gained a wider audience.

Fig. 11 Paper Sticker Used for Cataloguing

01012906006-04, 1870 CE: Sòng thung lek (Rewards Derived from the Donation of Religious Iron Flags)

Source: Digital Library of Lao Manuscripts, National Library of Laos (n.d.)

In Fig. 12 the gray-highlighted writing in the last folio reads “ໜັງສື ໄດ້ເອາມາແຕ່ວັນທີ່ 12 ເດືອນ 9 1938” (This manuscript was given on the 12th day of the ninth month in the year 1938). The date is written according to the Common Era, with the ninth month referring to September and not to the ninth month of the Lao lunar calendar (August). According to its colophon in the following quote, the manuscript was written in 1847 by a monk from Vat Sop Sikkharam before it was, almost a century later, forwarded to its current location, Vat Mai Suvanna Phumaram:

Fig. 12 Notation on the Date of Manuscript Acquisition

06011406004-09, 1847 CE: Sòng pha sangkat lòng (Rewards Derived from Merit-Making at Traditional New Year Festivals)

Source: Digital Library of Lao Manuscripts, Vat Mai Suvanna Phumaram, Luang Prabang

จุลศักราชได้พัน ๒ ร้อย ๙ ตัว ปีเปิกสัน วันอาทิตย์ เดือน ๑๑ ขึ้นค่ำ ๑ รจนาแล้วยามกองดึก หมายมีเจ้าหม่อมพ่อมั่น วัดสบ เป็นมูลศรัทธา ได้สร้างธรรมปิฏกะผูกนี้ไว้กับศาสนาเท่า ๕ พันวัสสา ขอให้อานิสงส์ส่วนบุญอันนี้ ไปค้ำชูพ่อแม่ลูกเมียแห่งข้าพเจ้า ผู้ที่จุติไปสู่ปรโลกภายหน้านั้นแด ก็ข้าเทอญ นิพฺพา นิพฺพา ปรมํ โหนฺตุ

[The writing of this manuscript was finished] in 1209 CS (1847), a poek san year, on a Sunday, on the first waxing-moon day of the 11th [lunar] month,27) at the time of the evening drum (19:30–21:00). Cao Mòm Phò (father-aged monk) Man from Vat Sop [Sikkharam] was the principal initiator who sponsored the production of this Piṭaka religious manuscript to ensure the continuation of the five-thousand-year Buddhist era. May this merit support my parents, my wife, and my children who passed away and entered the other world. Nibbā nibbā paramaṃ sukkhaṃ hontu.

The notation was written as a new layer of affiliation (see Section V-4) with ballpoint pen in the modern Lao script, with Arabic numerals and the year of the Common Era. This implies either that the librarian of Vat Mai Suvanna Phumaram was more familiar with modern and Western scripts or that the librarian wrote the notation for future librarians who may be inexperienced in the Dhamma script. The librarians’ work in the two examples above can assist users illiterate in the Dhamma script.

V-3 Editions and Revisions

The third purpose of using new technologies was for editing and revising manuscripts, for both texts and objects/leaves. In sermonic practices, aids such as pronunciation markers and pause markers were added. Scriptural learning (Lao: hian thet hian sut ຮຽນເທດຮຽນສູດ, literally “learning preaching and learning sermons”) is an important task (Lao: thit-thang nathi ທິດທາງໜ້າທີ່)28) of the Lao Buddhist sangha, as defined by the Lao Buddhist Fellowship Organization in 2007 (Bounleuth 2015a, 51). Monks are thus required to devote themselves to supporting basic pedagogy.

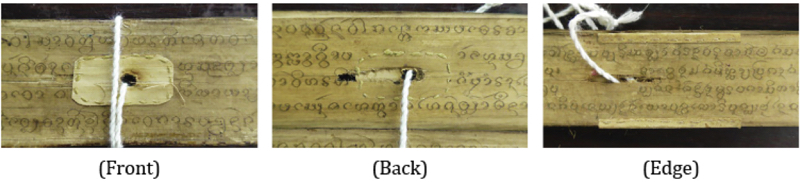

The text of a manuscript is not shown to the audience during a sermon, and a number of manuscripts are filled with corrections made in ink. Inscribing manuscripts is a one-way process in which no stroke can be undone, especially in the case of writing tools that leave permanent traces, e.g., inked handwriting and traces of engravings. Mistakes cannot be corrected without affecting adjacent words, worsening surface texture, and reducing legibility. White correction fluid was commonly applied to manuscript surfaces to correct mistakes. Ink and ballpoint pens were used to write additions, delete mistakes, emphasize faded traces, provide a statement for organizing folios, and mark replacement positions. New writing and correction tools saved scribes time: scribes no longer had to discard wrongly written folios and start afresh. In the case of palm-leaf manuscripts, a small piece of palm leaf or cloth was sewn with yarn to fix fragile spots but not to make textual corrections (Fig. 13).

Fig. 13 A Piece of Palm Leaf and Cloth Sewn to Strengthen Bookbinding and Edges (photos by Silpsupa Jaengsawang, February 21, 2017; February 24, 2017)

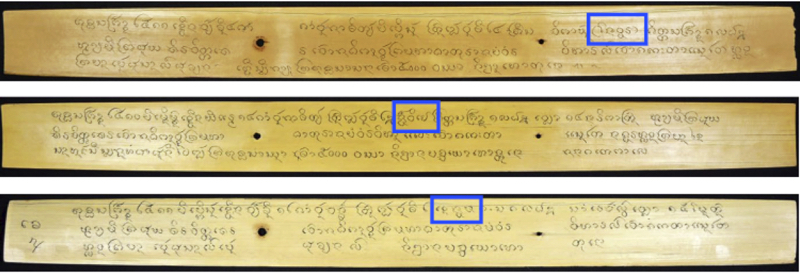

In Figs. 14 and 15 revisions were made with blue ballpoint pen: faded spots were emphasized, unwanted words were deleted or marked for deletion, and new words were added to replace unwanted ones. In Fig. 15 unwanted sentences were framed to be deleted and marked “discard” (ບໍ່ເອົາ) and “delete this row” (ແຖວນີ້ເອົາອອກ) in the modern Lao script. It is not unusual for anisong manuscripts to have corrections, even the most organized ones. Especially in the late twentieth century, manuscripts were regarded as utilitarian objects for scientific studies rather than sacred objects that it was sinful to interfere with; correctness of spelling was considered more important than the sacredness of the Dhamma script (Bounleuth 2015b, 213–214). Revisions made by later users are considered acceptable as long as the texts have not deteriorated and are still out of the audience’s sight. Since some colophons have scribal statements openly inviting users to correct mistakes, revisions are not regarded as sinful but as helpful, as in the following example:

Fig. 14 Corrections with Blue Ballpoint Pen

BAD-13-1-0714, n.d.: Sòng pathip hüan fai (Rewards Derived from the Donation of Light Floating Vessels)

Source: Buddhist Archive of Photography (BAP), Vat Saen Sukharam, Luang Prabang

Fig. 15 Deletion of Lines and Sentences with Blue Ballpoint Pen

BAD-22-1-0181, n.d.: Sòng sim (Rewards Derived from the Construction of Ordination Halls)

Source: Buddhist Archive of Photography (BAP), Vat Maha That, Luang Prabang

เจ้าหม่อมหมั้นได้สร้างสองทุงเหล็กไว้กับศาสนาโคตมะเจ้า ๕๐๐๐ วัสสา ขอให้ได้ดังคำมักคำปรารถนาสู่เยิงสู่ประการก็ข้าเทอญ ตัวหนังสือบ่งามเท่าใดแล้ว อายเจ้าหม่อมอายจัว ตกผิดเหลือผิดให้คอยพิจารณาหาใส่ได้เน้อ

Cao Mòm (monk) Man sponsored this manuscript titled Sòng thung lek to ensure the continuation of the five-thousand-year Buddhist era. May all my wishes be fulfilled. It is embarrassing [if] monks and novices [see this manuscript, because] my handwriting is not elaborate. [You are allowed to] correct missing parts and mistakes. (Sòng thung lek [Rewards derived from the donation of religious iron flags], code: BAD-22-1-0366, Vat Maha That, Luang Prabang, n.d.)

In Fig. 16, according to the comment in the gray box—“ໃບນີ້ບ່ແມ່ນ ເຈົ້າຂອງໃສ່ຜິດ” (This folio is wrong; the owner put the wrong one)—a blue ballpoint pen has been used to delete the mistaken folio. The comment is written in the modern Lao script in vernacular, indicating a folio wrongly allocated. This wrong folio likely belongs to a Jātaka story, as it mentions a Bodhisatta (Buddha-to-be).

Fig. 16 Indication of a Wrong Folio

01012906006-04, n.d.: Sòng thung lek (Rewards Derived from the Donation of Religious Iron Flags)

Source: Digital Library of Lao Manuscripts, National Library of Laos, Vientiane

V-4 Affiliation and Ownership Statements

Affiliation and ownership statements are reflected through a new layer of affiliation notes written in ink or ballpoint pen. The new layer reflects the tradition of manuscripts being circulated among local temples. Secular and even religious manuscripts were limited in number due to the lack of Dhamma script literacy, which was restricted to (ex-)monks and (ex-)novices. It was thus quite common for a sermonic manuscript to be available at only one monastery. Since circulating manuscripts could get lost, affiliation and ownership statements (monasteries and monks) were added to remind users to return the manuscripts to their original owners after use. As affiliation/ownership statements are not found in every extant manuscript, those with new entries may be considered to have been particularly popular: if a manuscript had not been borrowed often by other monasteries, an ownership statement would not have been added.

The newly added affiliations shown in the gray boxes in Figs. 17 and 18 read “[This manuscript] belongs to Monk Phui” and “Vat [temple] Pa Fang,” respectively. Both ownership statements are written in blue pen in vernacular in the modern Lao script, at the end of the text. Monk Phui or Sathu Nyai Phui Thirachitta Maha Thela (1925–2005) was the abbot of Vat Maha That (Grabowsky 2019, 136); the manuscript in Fig. 17 is thus marked with his name as the affiliation or principal authority. This manuscript’s colophon also mentions his name as the sponsor and scribe.29) In the example in Fig. 18, the affiliation “Vat [temple] Pa Fang” was added in the last folio of the manuscript fascicle even though, according to its code preceded with “BAD-15,” its current monastic archive is Vat Pak Khan. The manuscript was sponsored by a couple and donated to Vat Pa Phai, according to its short colophon: “มูลศรัทธาทิดยา ผัวเมียสร้างแล ป่าไผ่” (The principal sponsors [of this manuscript] were Thit [ex-monk] Ya and his wife. [The manuscript was donated to a temple] named Pa Phai). The manuscript’s journey thus commenced at Pa Phai Monastery through the donation of the sponsors, traveled to Pa Fang Monastery, and eventually reached Pak Khan Monastery. The three monasteries are close to one another. Manuscripts were ordinarily circulated within a local community, with village monasteries having limited numbers of liturgical or educational manuscripts. Monastic libraries functioned as local or public ones. Manuscripts are thus held by either monasteries or individuals, and ownership is not static (Bounleuth and Grabowsky 2016, 12). A number of colophons in anisong manuscripts include reminders that borrowed manuscripts need to be returned to their home affiliations.

Fig. 17 Affiliation Monk

BAD-22-1-0913, 1975 CE: Salòng thung lek (Rewards Derived from the Donation of Religious Iron Flags)

Source: Buddhist Archive of Photography (BAP), Vat Maha That, Luang Prabang

Fig. 18 Affiliation Monastery

BAD-15-1-0031, n.d.: A compilation of anisong texts

Source: Buddhist Archive of Photography (BAP), Vat Pak Khan, Luang Prabang

V-5 Dedication Rituals

Since the dedication of manuscripts to a monastery requires a short religious ritual for anumodanā or a celebration of merit-making,30) a number of manuscripts have the names of sponsors to be announced at the ritual. There are two kinds of donation: original donation and re-donation. Originally donated manuscripts were never donated elsewhere after being produced. Re-donated manuscripts were donated to a monastery before being circulated or “allowing” the names of new donors to be written. New donors can offer money to support monastic tasks such as repairing a monastic library, funding monk-scribes, and providing funds for monastic education. People still believe in merit gained through sustaining the Dhamma and the next Buddha Metteyya after the end of the current five-thousand-year Buddhist era.31) The use of modern ink pen for writing re-donation statements reflects the living tradition of religious manuscripts being donated to monasteries. Re-donated manuscripts are viewed as multilayered manuscripts32) as they contain representations of different donation authorities.

Fig. 19 shows a statement of manuscript donation newly written with blue pen in the modern Lao script: “ໜັງສືຊຽງສຸກຜັວສາວຈັນ” (This manuscript [belongs to] Siang [ex-novice] Suk [who is] the husband of Sao [Miss] Can). The names of the sponsors also appear at the end of the text, as shown in the gray box reading “Ban [village] Bak Lüng, Siang [ex-novice] Suk [and] Sao [Miss] Can,” which was inscribed with a stylus in the Dhamma script before the new text was written. The only occasion where sponsors are addressed is a dedication ritual in which a recipient monk announces the names of donors when praising their meritorious deeds. The paracontent33) in the manuscript provides barely any traces, probably why the sponsors’ names are repeated in the modern Lao script. However, the position of the last folio leads to speculation on the purpose of the new writing. It was likely an aid for a recipient monk who was moderately skilled in the Dhamma script but responsible for holding a dedication ritual in which the sponsors’ names had to be announced. The names were therefore written in the modern Lao script in the last folio or back cover, which was easily visible.

Fig. 19 Statement of Original Donation

BAD-22-1-0440, n.d.: Sòng anisong pitaka (Rewards Derived from Copying the Buddhist Canon)

Source: Buddhist Archive of Photography (BAP), Vat Maha That, Luang Prabang

Fig. 20 shows the first folio of a palm-leaf manuscript containing a colophon. Unlike this example, colophons in anisong manuscripts were normally at the end of the text. This photograph shows original donation and re-donation. The initial colophon was inscribed in the Dhamma script with a stylus and mentions “[A]Can [teacher] Suk” and his family, who lived in the United States (black box). Framed in the gray rectangles, the names “Thao [Mr.] Thòng Wan” and “Thao [Mr.] Can Pheng” were newly added in the modern Lao script with blue pen, obviously showing the re-donation of this manuscript by the two new donors to gain shared merit from dedicating the manuscript. Re-donated manuscripts can thus contain several donor names. Like the example in Fig. 19, the modern Lao script may have aided a recipient monk inexperienced in the Dhamma script in a dedication ritual.

Fig. 20 Statements of Original Donation and Re-donation

BAD-13-1-0155, n.d.: Panya barami (Rewards Derived from Following the Thirty Perfections)

Source: Buddhist Archive of Photography (BAP), Vat Saen Sukharam, Luang Prabang

V-6 Buddhisization

Like in other regions whose manuscript cultures were transformed through new printing technologies and writing tools, manuscripts as objects in Laos were influenced by modernity in the postcolonial period. Particularly in Luang Prabang, however, anisong manuscripts were regarded as texts in the contemporary cultural context. They were created for actual events and to Buddhisize secular34) or non-Buddhist rituals—such as birthdays and marriages—as evidenced by the extant anisong manuscripts. Anisong, as studied by Gregory Kourilsky and Patrice Ladwig (2017–18), is regarded as a case of hybrid writing, a genre composed in Pali and vernacular languages to link vernacular writings to local customs:

A review of existing manuscripts in Laos reveals that while the most ancient manuscripts available (sixteenth century) are Pali texts, vernacular language writings progressively replaced Pali to such an extent that from the nineteenth century onwards, the vast majority of texts is actually written in Lao, but interspersed with Pali fragments, sentences or words. These hybrid writings belong to specific categories such as nissaya, vohāra, sap, anisong (P. ānisaṃsa), sutmon (P. sutta-manta), gāthā, nithan, (P. nidāna), tamnan (“chronicles”), and so forth. Actually, Pali (or, to a lesser extent, Sanskrit) scriptures are used as a “tool box” of notions, concepts and technical terms, whose main purpose is to connect vernacular writings and local customs to what Steven Collins has aptly termed the “Pali imaginaire.” (Kourilsky and Ladwig 2017–18, 200–201)

Formerly non-Buddhist rituals were elevated to Buddhist ones by inviting a (chapter of) monk(s) to give an anisong sermon explaining meritorious rewards. Among other definitions given by various scholars, Justin McDaniel defines anisong and salòng, which also deal with non-monastic rituals, as follows: “Ānisong (ānisaṃsa) are ‘blessings’ that honor gifts made to the sangha and are often preludes to honor other Buddhist texts. Xalǭng (Chalong) are ‘celebratory’ texts used to describe and instruct, often, non-monastic rituals” (McDaniel 2009, 130). Manuscripts concerning birthdays and weddings did not originate from Buddhism, because birth and marriage, as part of the cycle of birth and rebirth, are contrary to Buddhism’s ultimate goal of enlightenment (nibbāna). To Buddhisize these secular ceremonies, anisong manuscripts were composed from several (non-)canonical sources and associated with the teachings of the Buddha so that audiences at anisong sermons could be convinced the Buddha’s teachings could be applied to their everyday lives.

Although the two main duties of Buddhist monks were—and still are—scriptural learning and meditation training, monks were invited to give blessings, hold religious sessions, and add a sacred element to nonreligious ceremonies (Bounleuth 2015a, 44; Bounleuth and Grabowsky 2016, 3). The Buddhist sangha held a privileged position in traditional Lao society and was in times of political crisis even able to intervene in secular matters (Grabowsky 2007, 137). There was a reciprocal relationship between monks and laypeople: “while a vat (temple-monastery) determines the identity of a community, the members of that community have the obligation to maintain the vat” (Khamvone and Grabowsky 2017, 19). Buddhisization of secular ceremonies was a result of mutual agreement between the sangha and the laity who promoted activities that were unrelated to the goal of nibbāna but not sinful. Buddhism does not prohibit secular life, and the Buddha even delivered teachings for those who were not part of the monkhood, e.g., Iddipāda (Paths of accomplishment),35) Brahmavihāra (Sublime states of mind),36) Saṅgahavatthu (Bases of social solidarity).37)

Anisong manuscripts containing sermonic texts to Buddhisize secular rituals and ceremonies and even other profane matters have been discovered in Luang Prabang: Anisong taeng ngan lü kin dòng (Rewards derived from merit-making at wedding ceremonies), Anisong tham bun wan koet (Rewards derived from merit-making on birthdays),38) among others.39) Ten anisong manuscripts concerning birth and marriage (1952–98) have been discovered in Luang Prabang. Nine of them were donated by monks, implying monks’ openness to Buddhisizing secular rituals by giving anisong sermons. Within the expansion of the anisong preaching tradition, secular activities contributing to beneficial outcomes are valued as merit-making:

This “Buddhization” of formerly non-Buddhist rites and rituals is best reflected in Anisong texts which are generally known under the terms Salòng or Sòng in Lao. . . . More surprisingly, collections of manuscripts also include titles referring to non-Buddhist rituals, such as marriage ceremony (Anisong taeng ngan) in which monks are not supposed to intervene in this region of Southeast Asia. In truth, Anisong could be seen as a paradigm of the principle of what we might call “Buddhization by means of text,” that is, the legitimization of a given practice by its written record with a sacred script (the Dhamma script) on a sacred object (the manuscript). In this way, any local custom may become unquestionably “Buddhist” if it is included as a subject in an Anisong. (Bounleuth and Grabowsky 2016, 3)

One example is a manuscript titled Anisong salòng taeng ngan lü kin dòng (Rewards derived from merit-making at wedding ceremonies), which is combined with another text titled Anisong thawai pha pa (Rewards derived from the donation of monk robes) to make a multi-text manuscript,40) from Vat Mai Suvanna Phumaram. The text pertains to two types of marriage in India: awaha,41) which is performed at the husband’s house and the couple live in the husband’s house; and wiwaha,42) which is performed at the wife’s house and the couple live in the wife’s house. It explains what the wealthy man (setthi) Thananchai taught his devout and generous daughter Nang Wisakha (Visākhā),43) the ten proper habits of a good wife and how to cherish married life. The manuscript was used in wedding ceremonies to teach couples how to keep the family peaceful and happy, even though marriage was not regarded as a way to enlightenment. With hopes for a bright future, luck, and propitiousness during life transitions or rites of passage, ceremonies could be Buddhisized by making merit, offering alms to monks, and inviting monks to pray and give blessings. This was often accompanied by an anisong sermon. Evidently, Buddhisizing anisong manuscripts reflects the harmonious coexistence of non-Buddhist activities in the Buddhist context and the reciprocal relations between the sangha and laity, who, as long as they are not sinful, support one another.

VI Conclusion

During the period of French colonialism, the relationship between Lao people and their French administrators influenced the use of the vernacular language as well as manuscript culture in Laos. New printing technologies introduced by the French affected the Lao manuscript culture in the following four ways. First, projects pertaining to the dissemination of Buddhist teachings were supported by new writing tools and writing support for mass production. New printing technologies helped monks and novices to propagate the Buddha’s teachings. Second, the librarians’ tasks of storing and categorizing manuscripts in a repository used the new technologies of writing tools, paper labels, and especially the Roman alphabet to encode pronunciations for vernacular titles of anisong manuscripts; this reflected the participation of foreigners. Third, delivering a sermon requires familiarity with the recorded text; monk-preachers thus took time to practice and in the process marked and corrected texts written on palm leaves by using pens. Due to this, the original texts inscribed with a stylus look completely different from the text added in ink. Lastly, affiliation markers were written mostly in the modern script, reflecting the illiteracy in the Dhamma script of the monastic lay assistants who sometimes transported and stored manuscripts in monastic libraries.

There were four kinds of actors involved in the use of new technologies: sponsors, scribes, monks, and librarians. The modern Lao script was accompanied by new technologies, with a gradual decrease in the use of the Dhamma script. The modern Lao script was used to compensate for the dwindling knowledge of the Dhamma script and to accommodate those who could not read the script but were still part of the manuscript culture.

Accepted: October 2, 2023

Acknowledgements

With the attentive and helpful support of several people, the quality of this paper was greatly improved. First, I would like to thank Professor Dr. Volker Grabowsky, the principal investigator of my research project, who carefully read and commented on the paper. He tirelessly responded to my questions and guided me on the direction the paper should take. Second, I would like to express my greatest gratitude to the anonymous reviewers who spent their precious time on reading, evaluating, and giving constructive feedback and comments. They gave me new insights on relevant issues and ideas. The additional sources they recommended gave me a better understanding of the social context during the case-study period.

References

Manuscripts

01012906004-05. รวมอานิสงส์: สลองพระเจดีย์ทราย; สลองปราสาทผึ้ง; สลองปราสาทผึ้ง; สลองปราสาทผึ้ง [A compilation of anisong texts: Salòng pha cedi sai rewards derived from building sand stupas; Salòng phasat phüng rewards derived from the donation of beeswax castles; Salòng phasat phüng rewards derived from the donation of beeswax castles; Salòng phasat phüng rewards derived from the donation of beeswax castles]. Palm-leaf manuscript; languages: Lao and Pali; script: Tham Lao; 24 folios; n.d.↩

01012906005-01. รวมอานิสงส์: สลองอุมง; สลองอุมง; สลองอุมง [A compilation of anisong texts: Salòng umong rewards derived from the construction of chapels; Salòng umong rewards derived from the construction of chapels; Salòng umong rewards derived from the construction of chapels]. Palm-leaf manuscript; languages: Lao and Pali; script: Tham Lao; 48 folios; CS 1263 (1901 CE).↩

01012906006-04. รวมอานิสงส์: สองทุงเหล็ก; สองทุงเหล็ก; สองทุงเหล็ก; สองทุงเหล็ก; สองทุงเหล็ก; สองทุงเหล็ก [A compilation of anisong texts: Sòng thung lek rewards derived from the donation of religious iron flags; Sòng thung lek rewards derived from the donation of religious iron flags; Sòng thung lek rewards derived from the donation of religious iron flags; Sòng thung lek rewards derived from the donation of religious iron flags; Sòng thung lek rewards derived from the donation of religious iron flags; Sòng thung lek rewards derived from the donation of religious iron flags]. Palm-leaf manuscript; languages: Lao and Pali; scripts: Tham Lao and modern Lao; 27 folios; CS 1232 (1870 CE).↩ ↩

01012906006-07. รวมอานิสงส์: สองวิด; สองธรรมาสน์ [A compilation of anisong texts: Sòng wit rewards derived from the construction of public toilets; Sòng thammat rewards derived from the donation of pulpits]. Palm-leaf manuscript; languages: Lao and Pali; script: Tham Lao; 13 folios; n.d.↩

06011406004-09. สองพระสังกาดล่อง [Sòng pha sangkat lòng Rewards derived from merit-making at traditional New Year festivals]. Palm-leaf manuscript; languages: Lao and Pali; script: Tham Lao; 13 folios; CS 1209 (1847 CE).↩

06011406004-17. รวมอานิสงส์: อานิสงส์สลองแต่งงาน; อานิสงส์ถวายผ้าป่าบังสุกุล [A compilation of anisong texts: Anisong salòng taeng ngan rewards derived from merit-making at wedding ceremonies; Anisong thawai pha pa bangsukun rewards derived from the donation of monk robes]. Palm-leaf manuscript; languages: Lao and Pali; script: Tham Lao; 15 folios; CS 1324 (1962 CE).↩

06011406005-15. อานิสงส์ทำบุญวันเกิด Anisong tham bun wan koet [Rewards derived from merit-making on birthdays]. Palm-leaf manuscript; languages: Lao and Pali; script: Tham Lao; 7 folios; CS 1335 (1973 CE).↩

06018504078-00. ปะริวาร Parivāra [Palivan epitome of the Vinaya]. Palm-leaf manuscript; languages: Pali; script: Tham Lao; 22 folios; CS 882 (1520 CE).↩

17010106001-11. สลองแปงผาม Salòng paeng pham [Rewards derived from the construction of pavilions]. Palm-leaf manuscript; languages: Lao and Pali; script: Tham Lao; 11 folios; CS 1014 (1652 CE).↩

BAD-13-1-0155. ปัญญาบารมี Panya barami [Rewards derived from following the Thirty Perfections]. Palm-leaf manuscript; languages: Lao and Pali; script: Tham Lao; 8 folios; n.d.↩

BAD-13-1-0157. รวมอานิสงส์: สองดอกไม้ธูปเทียน; สองรักษาศีล; สองฟังธรรม; สองเผาผี; สองมหาเวสสันตระชาดก [A compilation of anisong texts: Sòng dònk mai thup thian rewards derived from the donation of flowers, incense sticks, and candles; Sòng haksa sin rewards derived from precept observance; Sòng fang tham rewards derived from listening to the Dhamma; Sòng phao phi rewards derived from the participation in funerals; Sòng maha wetsantara chadok rewards derived from listening to Vessantara Jātaka]. Palm-leaf manuscript; languages: Lao and Pali; script: Tham Lao; 40 folios; CS 1306 (1944 CE).↩ ↩

BAD-13-1-0387. สองสรรพทุง Sòng sapphathung [Rewards derived from the donation of all kinds of religious flags]. Palm-leaf manuscript; languages: Lao and Pali; script: Tham Lao; 6 folios; CS 1272 (1910 CE).↩

BAD-13-1-0685. สลองข้าวพันก้อน Salòng khao phan kòn [Rewards derived from the donation of one thousand rice balls]. Palm-leaf manuscript; languages: Lao and Pali; script: modern Lao; 6 folios; CS 1344 (1985 CE).↩ ↩

BAD-13-1-0714. สองประทีปเรือนไฟ Sòng pathip hüan fai [Rewards derived from the donation of light floating vessels]. Palm-leaf manuscript; languages: Lao and Pali; script: Tham Lao; 8 folios; n.d.↩ ↩

BAD-13-1-0760. ปัญญาบารมี Panya barami [Rewards derived from following the Thirty Perfections]. Palm-leaf manuscript; languages: Lao and Pali; scripts: Tham Lao and modern Lao; 6 folios; CS 1325 (1963 CE).↩

BAD-13-2-033. อานิสงส์สร้างพระไตรปิฎก Anisong sang pha tai pidok [Rewards derived from copying the Buddhist canon]. Mulberry paper manuscript; languages: Lao and Pali; script: modern Lao; 6 sides; n.d.↩

BAD-13-2-042. หนังสือหามื้อร้ายมื้อดี Nangsü ha mü hai mü di [Book of calculation for (in)auspicious days]. Mulberry paper manuscript; language: Lao; script: Lao Buhan; 80 sides; CS 1270 (1908 CE).↩

BAD-13-2-093. อานิสงส์ถวายกฐิน Anisong thawai kathin [Rewards derived from participation in the Kathin festival]. Mulberry paper manuscript; languages: Lao and Pali; script: Tham Lao; 21 sides; n.d.↩

BAD-15-1-0031. รวมอานิสงส์: สองอุมง; สองหอกลอง; สองหีบหนังสือ [A compilation of anisong texts: Sòng umong rewards derived from the construction of chapels; Sòng hò kòng rewards derived from the construction of drum shelters; Sòng hip nangsü rewards derived from the donation of book chests]. Palm-leaf manuscript; languages: Lao and Pali; script: Tham Lao; 30 folios; n.d.↩