Contents>> Vol. 13, No. 3

A Century of Media Representations of Muslim and Chinese Minorities in the Philippines (1870s–1970s)

Frances Antoinette Cruz* and Rocío Ortuño Casanova**

*Department of Literature, Faculty of Arts, University of Antwerp, Prinsstraat 13, 2000 Antwerp, Belgium; Department of Conflict and Development Studies, Faculty of Political and Social Sciences, Ghent University, Sint-Pietersnieuwstraat 41, 9000 Ghent, Belgium; Department of European Languages, College of Arts and Letters, University of the Philippines Diliman, Quezon City 1101, Philippines

Corresponding author’s e-mail: fccruz3[at]up.edu.ph

![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0789-6044

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0789-6044

**UNED, P.º de la Senda del Rey, 7, 28040 Madrid, Spain

e-mail: rocio.ortuno[at]flog.uned.es

![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2636-8279

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2636-8279

DOI: 10.20495/seas.13.3_547

The act of nation building has often stood at the center of postcolonial efforts to consolidate the governance of multiethnic and multireligious groups brought together under colonial regimes. In the Philippines, unresolved structural and cultural differences during colonialism can be seen in the vacillating treatment of ethnic or religious minorities such as Chinese and Muslims in the construction of the nation. This paper investigates the discursive exclusion of these identities in Philippine textual production, arguing that early postcolonial political assertions of plurality failed to align with continuing forms of discursive othering that aligned with colonial strategies and objectives. Subsequently, exclusivist narratives in the media were unable to reflect the inclusivist rhetoric in politics and academia on national unity. This is demonstrated through an empirical mixed-methods textual analysis involving word embeddings and collocations of identity discourses in digitized archives of multilingual periodicals dating from 1872 (the latter part of the Spanish colonial period, from the Cavite Mutiny to the Treaty of Paris) to 1972 (the end of democratic rule through the implementation of Ferdinand Marcos’ martial law in the Philippines after independence). These representations foreshadow the impact of antecedent narratives on contemporary efforts at imagining the nation.

Keywords: national identities, Philippines, Moros, Chinese, colonialism, print media, word embeddings, postcolonial

I The Exclusivist Idea of Nationhood in the Philippines

In 1975 the Moro National Liberation Front leader, Nur Misuari, voiced his concerns with the following words:

Even if we turn back the pages of history, it is impossible to find any single moment in our existence as a people where we were ever a part, let alone a possession, of the Filipino government. Ever since, our people have always zealously maintained their distinct character and identity as a nation. (Misuari 1975, cited in Stern 2012, 26)

Conceptual linkages can be drawn to an opinion column titled “Why Filipinos Distrust China” (Collas-Monsod 2018), in which the political loyalties of Chinese Filipinos were questioned in light of the rise of China as a regional and global economic power. Both collectives, Muslim Filipinos and Chinese Filipinos, with particular differences that will be elaborated upon in the following sections, were variously excluded from the construction of the nation despite the initial intention of cultural inclusivity. Isabelo de los Reyes (1899, 1) proposed such cultural inclusivity by saying that all the different cultures in the country, including Moors, Chinese-Malay, and negritos1) (see Mojares 2006, 470), were effectively brothers and sisters.

De los Reyes’s perspective was not, however, the most widespread among the Ilustrados, the Philippine educated class during the late nineteenth century. De los Reyes was born in Ilocos but defended the concept of national identity from the time of his first articles being published at the end of the nineteenth century on the defense of Luzon against the pirate Limahong (Mojares 2006, 290) to the time when he published a history of his region while building an “archive” about it (Mojares 2006, 306) or edited the first newspaper in the Ilocano language.

Oscar Evangelista (2002, 12) blamed the absence of a sense of nationhood in the Philippines precisely on regionalisms, and he distinguished between two sensibilities around the end of the nineteenth century and the configuration of the Philippine national idea: on the one hand, he identified the independence aspirations of the propagandists or Ilustrados, which were more in line with European romantic nationalist aspirations; and on the other, he drew on the work of Reynaldo Ileto2) to distinguish the nationalist perception of the native masses, who instead aspired to a return to freedom and life before the arrival of the Spaniards, a condition characterizing their notion of the Inang Bayan (motherland) (Evangelista 2002, 10). This version of popular nationalism, however, leaves out Chinese and Muslims, who were not part of the native pre-Hispanic utopia in which there were no invaders or foreign presences.

This conception of nationhood, which excludes ethnic but also social groups, aligns with Benedict Anderson’s (1991) explanation of the conception and formation of nationhood in his book Imagined Communities. Using as an example the opening pages of the novel Noli Me Tangere (Touch me not, 1887) by the Filipino writer José Rizal, Anderson speaks of how its description of a group of people unfamiliar with one another, but who nevertheless believe themselves to be a community existing in a certain place at a certain time, demonstrates the “we-ness” of a nation. Therefore, the exclusion of Chinese and Moros from the idea of the “Filipino nation” is also the exclusion of these two communities from the networks which the Ilustrados aspired to (Anderson 1991, 26–27). In line with this, Evangelista (2002, 12) notes that during the US invasion of the Philippines following the revolution, nationalist aspirations lacked a common archipelago-wide interest, worldview, and concept of the “national,” despite the existence of a flag and anthem.

This problem parallels that of other formerly colonized countries that excluded some ethnic-cultural groups from the idea of the nation in the name of forming a coherent national identity. Ignacio López-Calvo (2009, 18) gives the example of Cuba, where the national independentist heroes sought to build a nation based on a mestizaje (mixed ethnic ancestry) between blacks and whites, leaving out the significant Chinese population of the island. The exclusion in the Philippines is rooted in some historical reasons: while Christianized Filipinos formed a common identity around Catholicism during Spanish colonization, Moros and Igorots resisted invasion until the 1870s (Evangelista 2002, 8). According to the historian Onofre D. Corpuz (2005, 596–597), the Spanish had never effectively occupied Muslim territory, and thus the Muslims developed separately from the Christian population during the first Western colonization. For this reason, when Spain sold the archipelago to the United States for $20 million, it was in reality selling as a part of it, Moro lands it had never possessed.

Renato Constantino (1969, 298) points out that in 1903, at the beginning of the US colonization, when a new way of nationalism was being forged, Governor Taft enacted the policy of “the Philippines for the Filipinos,” implying the necessity of improving the standard of living of Filipinos and of giving them the benefits of an American education. The policy excluded the Chinese population, which had at the same time been marginalized and expelled from the archipelago with the extension of the Chinese Exclusion Act to Hawaii and the Philippines in 1902, but it also excluded the Muslims: Corpuz (2005, 602–609) highlights the various forms of violent resistance to the Americans by the Muslim peoples of the South from 1902 onward. Only in 1916 was Moro territory incorporated as a senatorial district into the Philippine government and covered under the recognition of religious freedom (Corpuz 2005, 611–612). In sum, neither Muslims nor Chinese were well integrated into the Philippine national imaginary in the early twentieth century, and they were similarly not seriously taken into account during the two main periods of nation formation: the Reform movement (1872–1896) (Agoncillo 1974, 2) and the first half of the twentieth century, when the United States proposed a national model for the Philippines.

Even as the Philippines gained independence from the United States in the 1940s, in a context characterized by regionalism and regional linkages, elites grappled with colonial-era discourses of belongingness and the nation-state. For the political elites and intelligentsia, this effectively meant addressing the question of whether the nation could transcend the models upon which previous colonial regimes had been built. From the 1970s, nationalist discourse further attempted to situate the belongingness of Moros into the Philippines by asserting a common anticolonial character. However, this justification has been criticized by scholars for its narrowness of scope, obscuring the fact that the anticolonial struggle was a common one among colonized peoples in the immediate region (Majul 1966), or, conversely, for its use of broad strokes to co-opt a struggle that did not resist Spanish occupation under a comparable framework to the nationalist discourse of the Christianized population (Abinales 2010).

In this article we argue that the representation of the Chinese and Moros in the given time frame reflected an exclusion from the idea of Filipino-ness, and we ask to what extent the Philippine media’s representation of these two groups was similar though the circumstances of exclusion were different. This leads us to posit the existence of a national hierarchy reproducing heavily racialized power hierarchies that were inherited from the colony until well into the first decades of independence.3) As we limit ourselves in this paper to a digital text analysis of the mid-nineteenth century in newspapers published by Spaniards in the Philippines until the end of the Third Philippine Republic in 1972, we lay the groundwork for future studies that investigate the development of minority identity discourses in the late twentieth and twenty-first centuries through computer-aided discourse analytical techniques.

II Moro and Sangley Representations

As the analysis of religious and ethnic representations has become a way to understand how political agents are configured (see Angeles 2016), it also allows for a “vertical” perspective in understanding how historical forces shape particular agents, of which representation is but one manifestation. This is particularly salient in national imaginaries of postcolonial states such as the Philippines, which has in recent history found itself navigating the contemporary geopolitics of the rising economic power of China and the “global war on terror” while articulating the ambivalent outlines of its own national identity, an identity that is particularly prone to politically driven ebbs and flows of tolerance toward Chinese and Muslim minorities, as shown above. While some strands of Filipino nationalist thought were keen on incorporating disparate societal groups into a common discourse of national unity (Thomas 2016), these often eschewed a critical interrogation of the endurance of divisive discourses on groups of people living under the same colonial regime.

One of the key differences between the colonial treatment of Indios on the one hand, and Chinese and Moros on the other, lies mainly in the intersection of religious conversion and (proto-)racial ontologies. Representations thus centered on a “bifurcated image” of the Indios as either “simple children of nature who would be receptive to tutelage in civilization and Christianity” (Fredrickson 2002, 36) or outright hostile and therefore deserving of violent countermeasures. Whereas the Moros were treated as Muslims, who in Europe were believed to have “been exposed to the gospel and rejected it” (Fredrickson 2002, 37), they were also treated as hostile Indios. On the other hand, the Chinese were tolerated as both foreign as well as “‘an entrepreneurial minority’—the kind of group that is likely to be deeply resented and readily turned into a scapegoat when conditions are unstable and times are hard” (Fredrickson 2002, 92).

II-1 Methodology for the Study of Representations

While there have been valuable studies employing a close reading of films, literature, and other media to map the representations of Moros and Chinese in the Philippines (Chu 2002; 2023; Gutoc-Tomawis 2005; Hau 2005; Angeles 2010; 2016), this paper employs a computer-assisted mixed-methods analysis of a digitized corpus of periodicals in the Philippines to provide quantitative insights into how the identity terms “Moro,” “chino,” “Chinese,” “Intsik,” and their associated morphological forms were represented in media discourses. The quantitative results are supported with a close reading of text excerpts with the target terms. The present corpus is constituted of Philippine newspapers in three languages (Spanish, English, and Tagalog) and spans the colonial and early independence eras (1872–1972) in three stages:

(1) From the Cavite Mutiny, which showed for the first time an archipelago-wide attempt at an anticolonial and national conscience (1872), until the end of Spanish colonization (1898);

(2) From the beginning of the Spanish-American War (1898) to the end of the US colonization of the Philippines (1946); and finally,

(3) From the beginning of the Second Philippine Republic, and therefore democracy and independence in 1946, to the end of democracy in 1972 with the beginning of the martial law promulgated by Ferdinand Marcos.

Our hypothesis is that, despite the fact that regime change supposedly implied a shift in social hierarchies from Spanish to US colonialism, and from the latter to an independent democratic government, the reality is that these hierarchies persisted with respect to the perception of Chinese and Muslim minorities. This raises questions about the link between representation and power distribution in the Philippines. The article explores the methodological possibilities and empirical support for diachronic analysis of identities in large corpora.

Our aim is therefore to compare the representation of Chinese and Muslims in the media over the three periods and across the languages in the study in order to highlight the repetition of colonial models over time, demonstrating their continuity well into the Philippines’ independent period in the 1970s.

II-2 Historical Roots of the Spanish and Philippine Representation of Muslim and Chinese Populations in the Philippines

II-2-1 Spanish Colonial Period

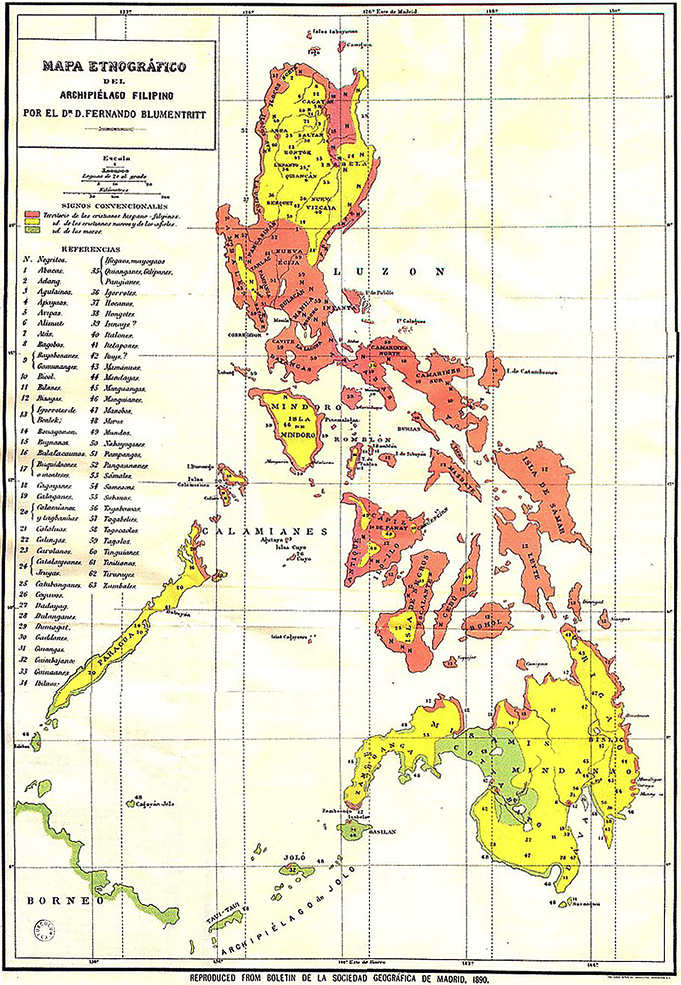

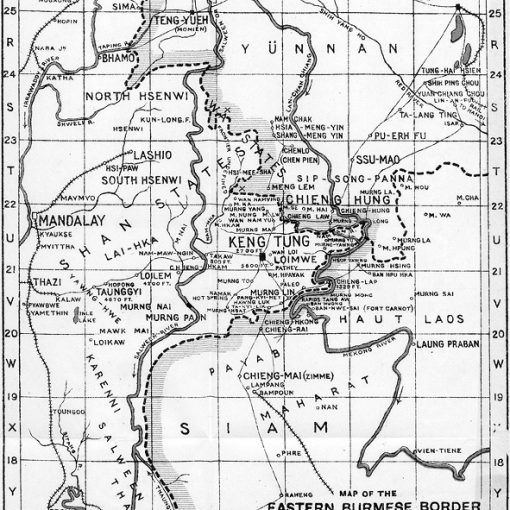

Writing on the history of Muslims in the Philippines, Cesar Adib Majul (1966, 306) described Spanish colonial policy as “deliberate” in its resolve to keep non-Christianized peoples separate from Christianized, colonized subjects of the Spanish Crown, as it dispatched Christianized soldiers from strongholds in the North to aid in subduing Muslim-held territories in Mindanao (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Map of the Philippines: Christianized Areas Cover Large Sections of Luzon and the Visayas (darker), while Majority Muslim Areas are Found in the Southwest of Mindanao.

Source: Blumentritt (1890)

For the Spaniards, the presence of Muslims evoked their history of conflict with the Moors on the Iberian Peninsula (Rodríguez-Rodríguez 2018, chap. 5). Mutual antagonisms based on “Moros” vs. “Christian” subjects in the Philippines thus began to take root, in terms of both official state policy and cultural expression. Historically, the term “Moro” was coined to refer to a class of Islamized Indios based on categories appropriated from the Spanish experience with the Moors (Rodríguez-Rodríguez 2018, chap. 5). One of the most enduring forms of cultural representation of the relationship between Islam and Christianity is the Philippine theatrical form of the komedya, also called Moro-moro, which depicts the triumph of Christians over Muslims and the latter’s conversion to Christianity (Tiongson 1999, cited in Angeles 2010). This is further reflected in the work The Roots of the Filipino Nation (2005) by the Filipino academic Corpuz, which cites the reproduction of a medieval narrative as a basis for national identity: the conflict between Muslims and Christians in Europe and the Middle East is both alluded to and extended in order to incorporate the national origins of the Philippines.

It is important to note that the spread of Islam in the Southeast Asian region posed challenges to the colonial aims of proselytizing and dominating trade links to Islamic Southeast Asia; the Chinese were similarly seen as a target of religious conversion and as a threat to Spanish interests in trade.4) In other words, Spanish colonial forces realized that the key to securing lucrative and monopolized access to the Spice Islands and China was by way of controlling the capacities of Chinese traders and merchants as well as the Moros, who were geographically closer to the Moluccas than the colonial capital established in Manila (Scott 1985, 47). Both the Chinese and Moros were well versed and well situated in the maritime trading routes of Southeast Asia.

The Chinese came to play a crucial role in the colonial economy, drawn by the galleon trade between Acapulco, China, and Manila (Chu 2002). As Edgar Wickberg (2000, 9) put it, “taxation, control, and conversion” were the main components of Spanish policy regarding the Chinese. Growing settlement of Chinese peoples in the Philippines during the Spanish colonial era was met with ethno-legal classifications and their attendant tax duties, which were higher for those of Chinese descent than for Indios (Elizalde 2019, 345), particularly since the Spaniards associated greater trade and economic prospects with Chinese in the Philippines, who dominated commerce and had created new occupations and services (Wickberg 1997, 155). Some of the concrete outcomes of the policies were: (1) segregation, through the creation of the parián, an area that acted as a marketplace and residential area, where some Moro merchants were also placed (Crailsheim 2020); the parián in Manila was built next to Intramuros, the walled city that acted as the colony’s seat of government and was home to Spanish-run churches, schools, and colonial functionaries; and (2) the creation of ethno-specific administrative roles: the Spaniards appointed a Christianized Chinese mayor in 1603 to facilitate relations with the Chinese in Manila. Christianization functioned as a similar aspirational civilizing strategy for the Moros, as it was believed to be a way to ensure Catholic subjects loyal to the Spanish Crown (Wickberg 2000, 15).

These policies triggered mutual tensions. Fears of a Chinese invasion and the corresponding breakdown of trust culminated in the Sangley Rebellion in 1603, with up to 25,000 Chinese residents being massacred (Wills 1998, 358). This episode was followed by revolts in 1639 and 1686. After the uprising in 1686, the Chinese community was expelled from the archipelago by the Spanish government. Expulsions were repeated in 1744, 1749, 1754, and 1766 due to different reasons.

With residential segregation, geographic mobility restraints within the islands for non-Christian Chinese, and quotas infrequently imposed on the Chinese population in Manila (Wickberg 1997, 156), a policy of ethnic-based social regulation was implemented in the day-to-day governance of the colony. The Spanish desire to Christianize the Chinese was further reflected in changing ethno-legal labels, such as the labels of Sangley Cristiano and Sangley infiel, which distinguished between Christianized and non-Christianized Chinese, respectively, and Sangley invernado and Sangley radicado, referring to resident and transient Chinese (Chu 2023, 10). Conversion efforts continued throughout the Spanish colonial era, culminating in the Sangleyes being given the option in 1840 to become naturalized Spanish subjects (Wickberg 2000, 155–156).

Conversely, the Spanish could not easily initiate social change or secure access to crucial trading routes without assuming territorial control over Muslim strongholds in the South. Even with nearby Spanish fortifications, such as Fuerte del Pilar in Zamboanga, they were not able to maintain control of Islamized groups and territories in the South, with only sporadic attempts at peace that rarely encompassed the entire territory. Treaties between the Sultan of Sulu and Spain were signed, for instance, in 1646, 1726, 1737, 1805, 1836, 1851, and 1878, with those of 1737, 1836, and 1851 being regarded as a “capitulation” (Wright 1966, 474). The Sultanate of Sulu was merely one amongst a number of Muslim polities in Mindanao and as such not representative of all the area’s inhabitants.

II-2-2 US Colonial Period

After the Philippines was ceded to the United States following the Spanish-American War, lingering questions about the status of the Moro territories and Chinese in the Philippines were inherited by the new colonial administration. For one, Moros and Chinese continued to be distinguished by differences in their political status from Christianized Filipinos of Austronesian descent, particularly with the new US concept of citizenship that distinguished between Filipinos and aliens, which impacted the latter (Chu 2023). These societal categories that had political and legal consequences in the colony came against the backdrop of pervasive racial discourses in the US itself (Kramer 2006, 185). On a political level in the Philippines, distinctions were made between areas that had been urbanized and assimilated into Spanish rule, for which the Americans established a civil regime, and areas such as the Cordilleras and “Moroland,” which fell under a military regime (Abinales 2010). While the Americans continued their attempts to assimilate Moros into the administrative structures of the colony, through measures such as the payment of land tax and obligatory military service, the Chinese were included as part of the extended Chinese Exclusion Act in 1902, which encompassed the overseas territories under the control of the US and placed limits on Chinese immigration. However, Filipino opinions were divided, as some intellectuals and politicians had started—since the end of the nineteenth century and during the first decades of the twentieth—to highlight the cultural connections between the Philippines and China as well as the Chinese population in the Philippines, and to look toward the latter for support in their anticolonial aspirations (Ang See and Go 2015, chap. 6; Ortuño Casanova 2021). Philippine intellectuals saw in the “yellow peril” discourse that had spread over Europe and the Americas (Dower 2012) a justification to perpetuate the Western dominion of Asia and took the opportunity to distance themselves from this discourse and look for affinities and connections aiming for an Asian identity. This attitude can be seen in works written in Spanish by prominent intellectuals such as Rizal, but also in the biography of Sun Yat-Sen written by Mariano Ponce in 1912 with an introduction by Teodoro M. Kalaw condemning the treatment given to Chinese in the Philippines and laying the blame on Western colonization (Ortuño 2021). A similar attitude was expressed by the first president of the Second Philippine Republic, Manuel L. Quezon:

There seems to be an impression that we Filipinos are prejudiced toward these Oriental brothers and sisters of ours. We should not be; it would be ridiculous for the Filipino who is Oriental to pretend to look with a certain tone of superiority upon the other inhabitants of the Far East who are of the same color as himself. . . . When these more or less temporary relations which unite us with other countries of a different race from our own are broken, it is those relations imposed by nature itself and by geography which will remain. (Quezón 1926, translated from Spanish)

II-2-3 Identity Markers After Independence

It was only in the twentieth century that the appropriation of the term “Moro,” which long held connotations of uncivilized peoples in faraway islands, and the coining of the term “Tsinoy” (in 1987) by Kaisa Para Sa Kaunlaran, a civic organization promoting the integration of ethnic Chinese into the Philippines, would eventually occur (Chu 2023). “Moro” has come to mean peoples with a shared history and become a term associated with Muslim resistance to colonialism and the dominant Christian culture in the Philippines. “Tsinoy/Tsinay,” “Filipino Chinese,” or “Chinese Filipino” is often used as an alternative to the Tagalog Intsik, a word derived from the Hokkien in-chek, meaning “his uncle,”5) to distinguish settled Filipino nationals of Chinese descent from recently settled non-nationals or expatriates from China (Chu 2023).

Contemporary images of Moros and Tsinoys in film and literature reveal a continuing dialogue and reinterpretation of the cornerstones of Philippine national identity. In the decades following independence, new visions of what it meant to be “Filipino” were promulgated through print media and academic writings and implemented through policies. For instance, the mass naturalization of Chinese Filipinos in the 1970s

entailed a shift in the discourse of nationalism away from monoculturalist and melting-pot claims of assimilation toward a strictly political definition of national belonging, which held that ethnic or minority groups could be integrated into Philippine society while preserving their cultural identities. (Cariño 1988, 47, cited in Hau 2005, 497)

Alongside calls for social integration and greater cultural tolerance within Philippine society, discourses that draw on old stereotypes of Moros and Chinese in the Philippines resurface in media, politics, and intellectual discourses.

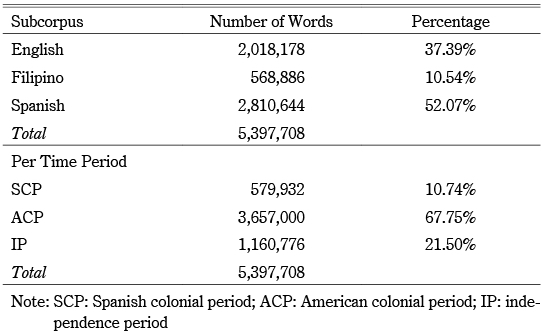

III The Corpus

The periodicals used in this study form part of the PhilPeriodicals project, an initiative to digitize over twelve thousand issues of periodicals published more than fifty years ago in the Philippines (Ortuño Casanova, n.d.). The present study utilizes print media from three time periods: the Spanish colonial period (1872–December 10, 1898), the American colonial period (December 11, 1898–July 4, 1946), and independence (July 5, 1946–1972) (see Appendix 1). Twelve periodicals in English, 12 in Tagalog, and 31 in Spanish from the collection were selected for study (see the language distribution in Table 1). Thematically, the collection is diverse to reflect a wide contextual scope for representation: from news and features (e.g., Graphic, Excélsior) to religious matters (e.g., Apostle, Ang Ebangheliko), military activities (e.g., Khaki and Red), literature (e.g., Ilang-Ilang, Bulaklak), and commerce (e.g., American Chamber of Commerce Journal, Boletín de la Cámara de Comercio Filipina) (for a list of journals, see Appendix 2).

Table 1 Summary of Corpus Word Counts

IV Methodology

One approach to discourse analysis has emerged from the study of the forms and functions of language using digitized corpora (Partington et al. 2013, 5), which came about as technological developments facilitated storage capacity and machine reading. The way “big data” is produced, stored, and read has posed new challenges for researchers, who consequently “need theories and methods that are [cap]able of accounting for the emergence of meaning in the different social, historic, and textual contexts, in which phenomena become meaningful and therefore can become social” (Scholz 2019, 11). Thematically, these methods have found an important intersection with questions on the regulation of bodies and identities, in the sense of “uncovering, in the discourse type under study, of what we might call non-obvious meaning, that is, meaning which might not be readily available to naked-eye perusal” (Partington et al. 2013, 11). The linguistic subcorpora of this study are formed based on the primary language of a periodical, in order to identify ideological or cultural views about a referent object that emerge through the comparative analysis of subcorpora in each language.

We thus apply techniques such as word frequency extraction, collocation analysis, and word embeddings and support them with close readings of relevant excerpts identified by quantitative tools on the present corpus of digitized periodicals to determine time-bound and language-bound semantic fields associated with Muslims and Chinese in the Philippines. These digital methods for text analysis serve to test hypotheses and have been useful in tracing the changing content of signifiers. For instance, William Hamilton et al. (2018) used word embeddings to visualize historical semantic change in words such as “broadcast” and “gay,” and Li Ke and Zhang Qiang (2022, 176) investigated articles in the New York Times on Islam, emphasizing stereotypical depictions such as “unacclimatized outsider” and “turmoil-maker.” Seen in this way, quantitative approaches to text analysis serve to validate hypotheses generated through qualitative studies for a large volume of texts and to provide empirical bases for the strength of particular discourses as opposed to others.6)

Historical texts, which can now be studied en masse with digital methods, were not only crucial in ascertaining the social categories of Moro and Sangley as deserving of a distinct treatment from Indios but used to inform social policies of successive regimes. The idea that power is inextricable from the processes of naming and the regulation of bodies—what Michel Foucault (1978, 139) would call biopolitics—foregrounds the following analyses, as subjectivation through language and practice may persist well beyond the formal cessation of policies based on ethnic distinctions. Depictions in literature and similar media further demonstrated the relationship between power and identity, as noted in the exoticized treatment of Islam and the Orient in the arts during the colonial era: depictions of the Orient could not be understood separately from the binary construction of a European identity, of which the Oriental was the negative counterpart (Said 1979; Hall 1997, chap. 4). However, linguistic binaries are only one means of othering and may be too limited in their capturing of meaning, in the sense that binaries often represent the two ends of a spectrum of possibilities (Hall 1997, chap. 4). Studies such as this can provide greater insights.

This study’s method involves first gathering word frequencies and co-occurrences, or collocations in particular contexts. Collocational analysis identifies words used within a defined window around the target word to determine contextually derived meanings. In this study, we further make use of word embeddings to provide a “macro” lens for identifying common themes in the corpora before closely examining individual instances of a term in context. Word embeddings are representations of words as vectors that are trained by machine learning techniques and can be used to derive semantic similarity. A popular method, represented here by Word2Vec (Mikolov et al. 2013), involves the identification of semantically similar words through the generation of a multidimensional vector space from a large corpus of text. Each vector in this method represents a specific word, while the closeness of one word vector to another (calculated by measuring the cosine distance between vectors) represents the similarity of linguistic context. Countries or ethnicities, for instance, may be used in similar contexts to one another, which can be detected and represented mathematically. In order to visualize the data, this paper makes use of t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) (Van der Maaten and Hinton 2008), a machine learning algorithm that reduces the results gathered from Word2Vec into two or three dimensions.

We first performed a layout analysis on the texts using Transkribus’s print block detection module (Kahle et al. 2017) and converted the texts to a readable format using a customized Optical Character Recognition model. The model was based on a training set of 157 manually annotated pages that included samples from each of the target languages, and a validation set of 15 pages. Transkribus further employs a character error rate (CER), which “compares the total number of characters . . . including spaces, to the minimum number of insertions . . . substitutions . . . and deletions of characters” (Transkribus, n.d.). The CERs for the model used in the study are 1.94 percent (training set) and 1.87 percent (validation set).

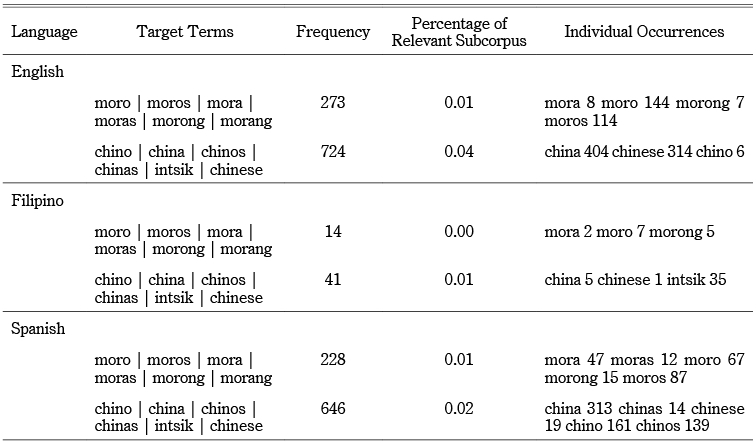

The texts were then pre-processed to eradicate numbers, punctuation, and stop words, which include function words such as articles, pronouns, conjunctions, and particles, among others. Stop word lists were taken from Sedgewick and Wayne (2020) (English), Diaz (2016a) (Tagalog), and Diaz (2016b) (Spanish) and refined based on further function words7) or orthographical errors that appeared in the corpus. Due to the presence of multilingual periodicals, a combined stop word list was built from the main languages in the study (Filipino, English, and Spanish) and applied to the dataset. Subsequently, the appearance of words related to identities was studied through examining word frequencies and word collocations appearing in each subcorpus through the use of Gephi and AntConc (Anthony 2019).8) The collocations mentioned below were identified on the basis of the mutual information score that measures the probability of a keyword occurring next to a collocate, relative to the number of times each word occurs in total (Stubbs 1995). As mutual information scores tend to be higher for infrequently occurring collocates, the frequency floor for this corpus was set to three occurrences and above. The searched words were drawn from the literature on Moros and Chinese Filipinos (e.g., Angeles 2010; Chu 2023). Due to the multilingual nature of the corpus, collocations were identified for all possible morphological forms of the target word across languages, e.g., moro|moros|mora|moras|morong|morang9) and chinese|chino|chinos|china|chinas|intsik.10) English collocations centered around the words “moro” and “chinese” were first gathered by AntConc (Anthony 2019) and assigned a mutual information score, as described above. Only those collocations with mutual information scores greater than zero with a frequency floor of three were considered in the analysis due to the relatively small (Davies 2019) and particular nature of the corpus. Collocations of up to five words on each side were then collected per target word per subcorpus, while Word2Vec (Mikolov et al. 2013) was used to determine words occurring in a similar semantic space to each target word.

V Analysis

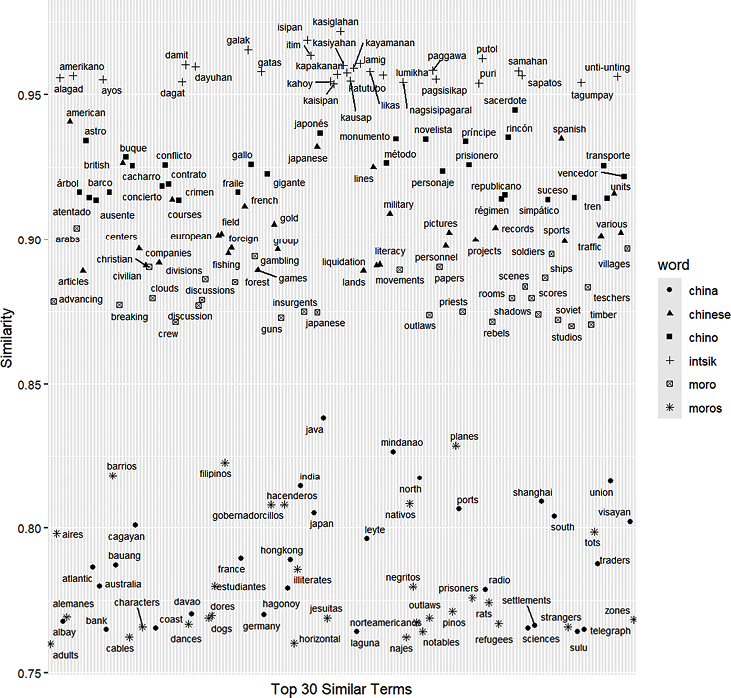

V-1 Word Embeddings

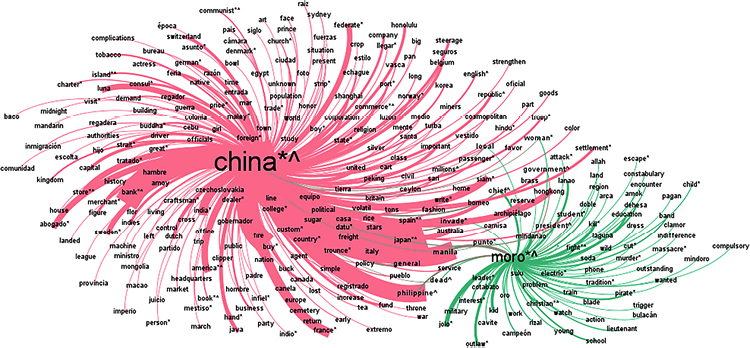

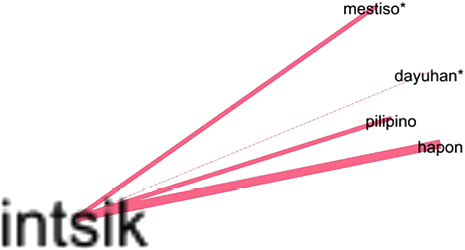

Word embeddings were created using Word2Vec (Mikolov et al. 2013), which can be used with a cosine similarity measurement to estimate the semantic difference between two words used in similar contexts. As the selected corpus is relatively small, comprising just over five million words, all time periods and languages were entered as input for the measurement of similarity. For the terms “Moro” and “Moros,” which are shared amongst all three languages, embeddings included words with implications along the binary dimensions of savagery/civilization and rural/urban—“forest,” “illiterates,” “nativos” (natives), and “barrios”—as well as terms related to operating outside of the law, such as “outlaws,” “prisoners,” and “insurgents”; while chinese|chino|china included “prisionero” (prisoner) and “crimen” (crime) (Fig. 2). The results for the terms chinese|chino|china|intsik revealed associations with other places and nationalities, trade and commerce, and otherness, found in the terms “foreign” and “dayuhan” (foreigner). Furthermore, both target terms (words relating to Moros and Chinese) were found in similar contexts to words indicating armed forces or government positions, such as “gobernadorcillos” (governors) or “military,” and maritime transportation—“ship” and “barco” (boat). It is worth noting that there were notably positive embeddings found in Spanish and Filipino, such as “simp[á/a]tico” (nice), “kasiglahan” (liveliness/cheerfulness), “galak” (joy), and “puri” (praise) for the Chinese-related terms (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Word2Vec Similarity Results for Target Terms

Source: Generated by Cruz

Note: Other variants of the target terms, such as chinos and chinas, have not been included in this visualization for more clarity. For the code to the embeddings, as well as the vector visualization of the top thirty target terms, see Cruz and Ortuño Casanova (2022).

We can thus surmise that the multilingual semantic fields for Chinese and Moros come together in their foreignness and nonconformity to law, yet it is only in the Spanish and Filipino texts that positive (as opposed to negative or neutral) terms are found. In the following section, an overview of the per-language collocations of the target terms is provided (for a summary of term distribution, see Tables 2 and 3).

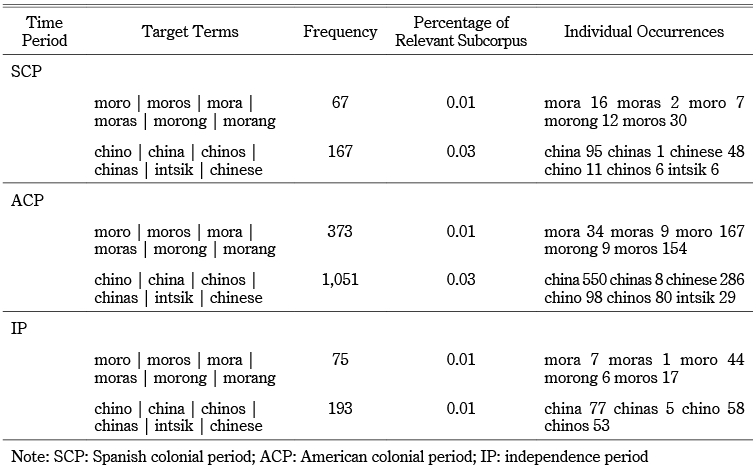

Table 2 Frequencies of Keywords per Language Corpus

Table 3 Frequencies of Target Words per Time Period

V-2 Collocation, Frequency, and Close Reading Analysis per Language Corpus

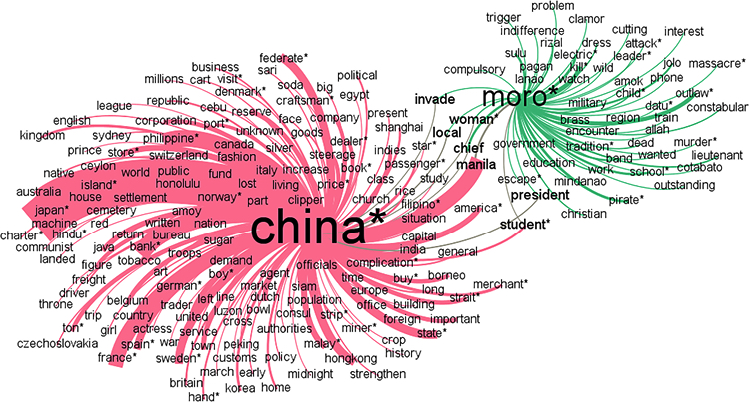

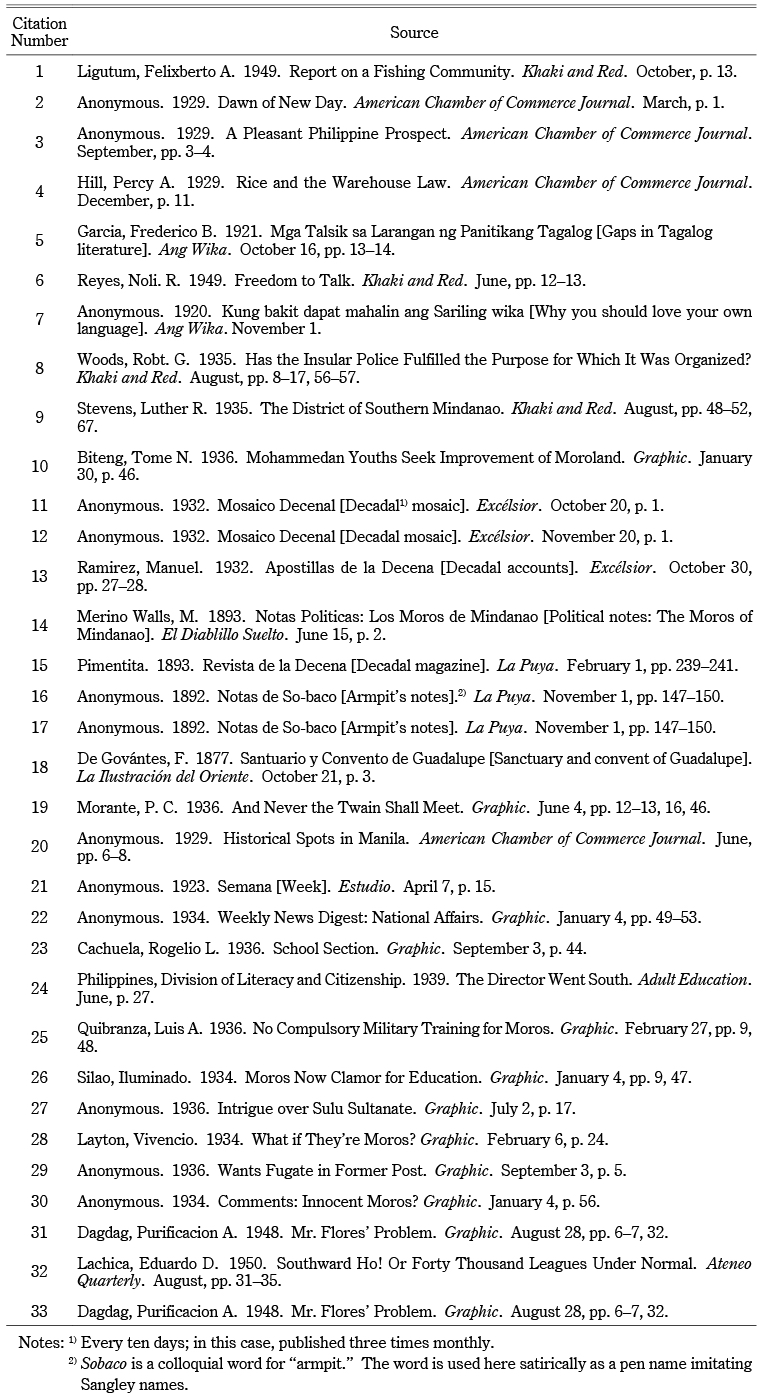

Collocations, as opposed to word embeddings, take a closer look at non-function words in the immediate vicinity of the target terms. In the English corpus, the adjective “Chinese” was often employed in conjunction with known landmarks in Manila, such as the “Chinese Cemetery” and the “Chinese General Hospital,” but also to describe places where ownership or patronage comprised mostly people of Chinese descent, such as “Chinese school” or “Chinese store.” The corpus further revealed collocations with terms related to trade and goods, such as “store” (12), “dealers” (11), “demand” (7), “business” (5), “merchants” (5), “sari” (from sari-sari store) (4), “market” (4), “trader” (3), “crop” (3), “silver” (3), “rice” (6), and “sugar” (4) (see Figs. 3 and 4).

Fig. 3 All Collocations of moro|mora|moros|moras|morong|morang and chinese|chino|chinos|china|chinas|intsik (MI > 0; frequency floor ≥ 3; * = lemma; ^ = appears in more than one language)

Source: Generated by Cruz

Fig. 4 English-Language Collocations (MI > 0; frequency floor ≥ 3; * = lemma)

Source: Generated by Cruz

Apart from the ambiguity between Chinese who were resident in the Philippines and Chinese from mainland China, the use of the word “Chinese” and its collocations did not distinguish itself among previous Spanish social categories that indicated the duration of settlement in the Philippines or ethnic mixing with non-Chinese, such as Sangley invernado or mestizo de Sangley. This ambiguity was further demonstrated in blanket statements such as “Chinese in Davao” or “Chinese in Manila,” as well as the following:

(1) “Chinese who control the greater part of the industry . . .” (Khaki and Red, October 1949, 13)11)

(2) “Those Americans who recall Manila life . . . remember the entire dominance of the Chinese in retail trade . . . The Escolta was a Chinese street. . . . Today it is predominantly Filipino. . . . The Filipino is gradually taking over retail trade.” (American Chamber of Commerce Journal, March 1929, 1)

Each of these excerpts presumes a presence of Chinese in the country, but without simultaneously explicitly asserting that they are Filipino, or “local” in any way. The distinction overlaps with the strict ethnic division seen in other texts, such as the third excerpt, which distinguishes “Malayan” from “Chinese” inhabitants:

(3) “The culture of Lilio is quite purely Malayan, influenced only by the Spanish church. Chinese don’t live there.” (American Chamber of Commerce Journal, September 1929, 4)

Terms such as “foreign” (4) and “mestizo” (2) are shared with the Filipino corpus, in the case of “mestisong” (4) and “dayuhang” (3) (see Fig. 6). Apart from emphasizing the dominance of the “Chinese” in business and commerce, the third excerpt above points toward ethnic rivalry in retail ownership. In the fourth excerpt (below), “Chinese” who have maintained a long presence in the Philippines are not associated with “Filipino.” The fifth excerpt shows the different ethnicities of people within the Philippines who speak Tagalog. For all the emphasis on a national language, it is not implied that linguistic proficiency equates to national belonging. In this regard, the sixth excerpt shows displeasure at the situation of illegal migrant “Chinese” against whom the law is on the “warpath,” yet it does not otherwise provide any further information on what constitutes national belonging or “Chinese” who are “legally” in the Philippines. But the presumption that there are legal “Chinese” in the Philippines or “Chinese” who are not entirely “foreign” is implied in the seventh excerpt, in which the term dayuhang instik (foreign Chinese) appears.

(4) “The Chinese here in the business for centuries have not been able to do that.” (American Chamber of Commerce Journal, December 1929, 11)

(5) “Samantalang . . . may mga intsik, hapon, bumbay, at ibang pang nagsasalita ng aming matamis na wikang Tagalog” [However, there are Chinese, Japanese, Indians, and others speaking our sweet Tagalog language]. (Ang Wika, October 16, 1921, 13)

(6) “The law is now on the warpath against all Chinese who entered this country illegally.” (Khaki and Red, June 1949, 13)

(7) “. . . na sa mga dayuhang intsik na pumasok dito sa Maynila ay nakabilang ang isang babae . . .” [. . . that among the foreign Chinese that entered Manila there was a woman . . .] (Ang Wika, November 1, 1920, 2)

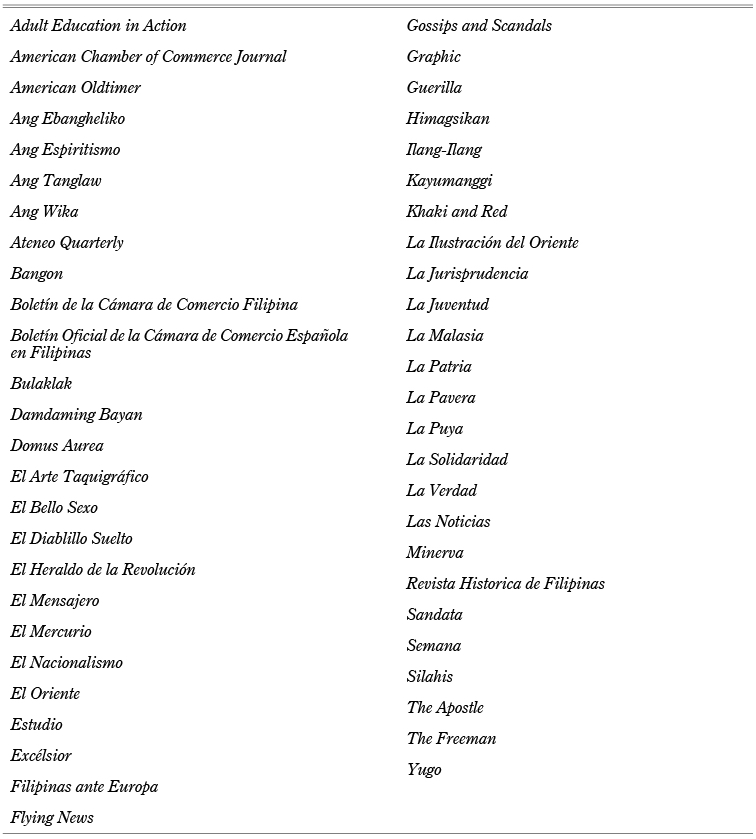

Nevertheless, the term “Filipino Chinese” does indeed appear in the corpus, such as in the proper names “Northern Filipino Chinese Chamber of Commerce” or “Filipino-Chinese Anti-Communist League,” though only as self-attributed names and not a fixed expression in discourse. Terms such as “Filipino-Chinese” do not appear in the Spanish texts, which employ terms such as “los mestizos de Sangley” instead, or in the Tagalog/Filipino texts, which do not seem to go beyond implying that there are “local” Chinese as opposed to dayuhang Instik (foreign Chinese). Related to views on the economic role of the Chinese in the area are Spanish collocations with “chino,” such as “banco” (9) or “canela” (cinnamon) (6) (see Fig. 5).

On the other hand, with regard to Moros, the English-language corpus features references to “Moro” as violent outlaws, bandits, or criminals—“killed” (13), “outlaws” (12), “pirates” (8), “band” (6), “encounter” (4), “dead” (4), “blade” (3), and “datus” (ruler) (3) (see Figs. 3 and 4)—and attempts to socialize them into the institutions of the colonial regime or, alternatively, the Philippine government:

(8) “The moro then seized him by the throat, . . . each trying to cut the other’s head off. The moro, an expert with cutting weapons, the kriss [kris] and the barong . . .” (Khaki and Red, August 1935, 16)

Following the revolutionary period (1896–1901) came what the nationalist historian Teodoro Agoncillo (1974, 2–3) called “‘suppressed’ nationalism” (1901–10), “Filipinization” (1910–21), and the Commonwealth (1935–41). It was during the latter period that US-American sociopolitical and territorial consolidation and control over the colony supported the promotion of a broad spectrum of American sociocultural and political norms through institutions such as public schools, banks, and government agencies. Throughout this period, the colonial regime retained elites from the Spanish colonial era while preparing a new set of bureaucrats and educators, or pensionados, through scholarship programs in the US (Francisco 2015; Lumba 2022). This became clear in the introduction of the English language through public schooling, and thus the emergence of English-language discourse during the American era, which was used as a tool for upward mobility in American-ruled “Moroland” as well as to facilitate Moro-led adaptation and propagation of the norms of the regime:

(9) “The young men of the Moro and Pagan tribes who lived in contact with the government during their one or more enlistments acquired a respect for and understanding of the government . . .” (Khaki and Red, August 1935, 51)

(10) “Datu Mariga Alonto also believes that the best way to solve the Moro problem is to educate the Moros because ‘in this way they will learn their duties and obligations to the government.’” (Graphic, January 30, 1936, 46)

The Moro as both “outlaw” and “law-abiding citizen” served to draw a binary between “educated”/positive and “violent”/negative Moros based on compliance with the regime. As students, law-abiding citizens, and teachers, Moros were positively represented in discourse, yet their “violence” was always portrayed as outside of and against colonial aims (and therefore “criminal”), or an inherent feature of their culture.

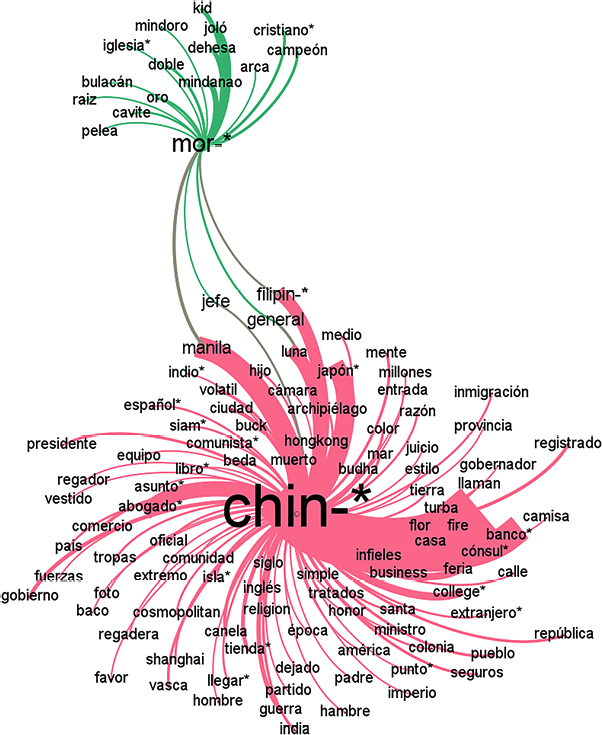

These descriptors can be seen having some continuities with Spanish-language discourses, characterized by their pessimism, distance from Moros (excerpt 11), and monolithic views, in contrast to a majority of English-language discourses, particularly during the American period, which demonstrate more social contact, optimism, and binarism. In the Spanish corpus, collocations over the frequency floor include “kid” (for Kid Moro, a boxer) (8), “general” (4), “cristianos” (Christians) (4), “filipino” (4), “pelea” (fight) (3), “oro” (gold) (3), and “iglesias” (churches) (3), reflecting underlying religious thematic foci (see Fig. 5).

(11) “Hoy como ayer, los moros levantiscos de Joló han vuelto a hacer una sonada. El Gobierno ha tenido que enviar un buen golpe de soldados constabularios para sofocar la ‘rebelión’ . . . Y el ‘hueso’ moro seguirá tan duro de roer como siempre lo ha sido” [Today, as yesterday, the Moorish rebels of Jolo went on the rampage again. The government has had to send in a good contingent of constabulary to put down the “rebellion” . . . And the Moorish “nut” will be as tough to crack as it has always been]. (Excélsior, October 20, 1932, 1)

Associations between Moros and violence can also be inferred from a discussion on the resolution of the continuing “problems”:

(12) “La primera es el ‘problema moro’ que continúa sin resolverse, pues los ‘rebeldes’ o remontados no cejan ni se rinden . . .” [The first is the “Moorish problem,” which remains unresolved, as the “rebels” or “remontados” do not give up or surrender]. (Excélsior, November 20, 1932, 1)

Absent from the English corpus but supported by historical data on immigration to Mindanao is another solution—the settlement of “Filipinos” to terra incognita. Mindanao is seen in an example of Spanish-language discourse below as worthy of settlement, which assumes the eventual social incorporation of Moros into the nation by virtue of belonging to the same race:

(13) “Y así como los microbios sostienen la lucha por la existencia, deben emigrar a la Morolandia elementos sanos de las demás regiones del Archipiélago magallánico, . . . , en fraternal convivencia con los naturales de las mismas, quienes, arrollados por la avasalladora corriente de la civilización, acabarán por asimilarse las saludables instituciones sociales de sus hermanos de raza, se confundirán con ellos en unos mismos usos, hábitos y cos[t]umbres, y respirarán una sola alma nacional, sin distinción de credos políticos, clases sociales ni creencias religiosas” [And just as microbes sustain the struggle for existence, healthy elements from the other regions of the Magellanic Archipelago must emigrate to Morolandia . . . in fraternal coexistence with the natives of those regions, who, overwhelmed by the sweeping tide of civilization, will end up assimilating the healthy social institutions of their brothers of race; will mingle with them in the same uses, habits, and customs; and will breathe a single national soul without distinction of political creeds, social classes, or religious beliefs]. (Excélsior, October 30, 1932, 27)

The Filipino/Tagalog corpus had the lowest number of occurrences of the word “moro,” with no collocations with a frequency greater than or equal to three, although “suntukan” (fistfight or boxing) and “kid” (referencing Kid Moro) but also “kris” (a type of sword) and “alipin” (slave) were among the collocations found, terms which evoke traditional and precolonial representations. On the other hand, “Intsik” features various identity categories associated with the Chinese (Filipino, foreigner, and mestizo) (see Fig. 6).

Fig. 6 Filipino/Tagalog-Language Collocations (* = lemma)

Source: Generated by Cruz

Note: Only one word, “kid,” was found for “moro” collocations.

All in all, the word embeddings were able to reveal the possibilities of Spanish and Filipino target terms being found in similar contexts to positive terms, whereas the terms in the immediate context of the target terms showed mostly negative and neutral word associations and little to no high-frequency positive terms. Although it is difficult to separate the languages from the respective eras in which they were used, it is worth noting that during the American colonial period, when Spanish was still used in print media, ideas of an unsettled Mindanao were deemed necessary to communicate to Spanish-speaking audiences. However, the Spanish-era focus on religion, missions, and conversion did not necessarily carry over into English-language materials. Furthermore, it appears that identity-related issues mostly did not appear in periodicals in Tagalog/the Filipino language at this time, which indicates not only their relative paucity in terms of volume, but also that social and political media discourse on identities in the time period covered by this study were conducted instead in the languages of power and prestige, circulated between and amongst educated elites. Having determined the era-driven characteristics of language use, we turn to diachronic word associations.

V-3 Collocation, Frequency, and Close Reading Analysis per Time Period

V-3-1 Spanish Colonial Period

The Spanish colonial period shows representations of Moros almost exclusively in the context of conflict with the colonial regime, and confined to certain areas of Mindanao. While there are not many mentions of “moro,” it is clear that Moros are presented as both an obstacle to the colony and incommensurable with Christianity (excerpt 14).

(14) “No hay fusión posible entre moros y cristianos; ya lo han dicho en España siete siglos de encarnizada lucha” [There is no possible fusion between Moors and Christians; seven centuries of fierce struggle in Spain have already said it]. (El Diablillo Suelto, June 15, 1893, 2)

The theme of continuing struggle, or lucha, can be further seen in La Puya, where fictionalized dialogues were sometimes employed as a device to discuss current events. In one such dialogue, the incompatibility of the Moros’ existence with peace and order for the rest of the country is emphasized:

(15) – “. . . ha habido un ataque entre moros y nuestras tropas habiendo estas matado cuatro moro[s] y hecho muchos heridos” [There has been an attack between Moros and our troops, the latter having killed four Moro[s] and wounded many].

– “Y te lo tengo dicho, Goyo—mientras en Mindanao quede un solo moro tendremos de esos casos á diario” [And I have told you, Goyo—as long as there is a single Moro left in Mindanao we will have such cases every day]. (La Puya, February 1, 1893, 239)12)

The lack of social encounters with the Moros due to their resistance to the Spanish occupation stands in contrast to the discourses on Chinese, who maintained a long-standing presence in the major cities of the Philippines. More than simply containing references to the economic role of the Chinese, as can be gleaned from the word embedding and frequency results, periodicals of this time focused on attributing the Chinese with a lack of civilization, particularly with regard to discounting their sincerity in religion, one of the main cornerstones of Hispanic civilizing discourse. China was not only cast as a place of non-religious peoples:

(16) “Las supersticiones y aberraciones del espíritu, constituyen un curioso estudio en la vida de los chinos. Aquel pueblo no es religioso. no concibe en elevada esfera la existencia de Dios, ni cree en los destinos del alma, redimida por la penitencia, salvada por las buenas obras” [The superstitions and aberrations of the spirit constitute a curious study in the life of the Chinese. Those people are not religious. They do not conceive in a high sphere the existence of God, nor do they believe in the destiny of the soul, redeemed by penance, saved by good works]. (La Puya, November 1, 1892, 147)

The othering of Chinese living in the Philippines was based on their insincerity in matters of faith, as seen in excerpts 17 and 18 below.

(17) “Así los chinos solo van á los templos cuando tienen necesidad de pedir algo á Dios” [Thus, the Chinese only go to temples when they need to ask God for something]. (La Puya, November 1, 1892, 147)

(18) “Todos llevan consigo la estampa de San Nicolás y apenas hay un chino infiel en Manila que no la tenga en su casa, colocada con gran veneración, al lado de Confucio” [Everyone carries with him the prayer card of St. Nicholas, and there is hardly an infidel Chinese in Manila who does not have it in his house, placed with great veneration, next to Confucius]. (La Ilustración del Oriente, October 21, 1877, 3)

V-3-2 American Colonial Period

The depiction of either a natural or strategic form of (in this case, religious) insincerity on the part of the Chinese to appease dominant society is a trope which has been referenced in pejorative US-American depictions of Asians, such as those showing them as “manipulative, with a tendency to use natural wiles and treachery to achieve their own ends” (Lippi-Green 2012). Self-serving attitudes toward religion were similarly used as a basis of othering in the Spanish era, during which Christianization acted as a measure of loyalty to the colonial regime and its objectives (Wickberg 1997). Subsequently, during the American colonial period, “othering” by imputing disloyalty would diverge from the religious dimension: instead, economic and political alignment would come into question (for a critique of opinion columns questioning Tsinoy allegiances, see Hau 2018). As the Americans eschewed previous ethno-legal categories of the mestizo de Sangley and Sangley, they instituted citizenship based on a binary of Filipino vs. alien (Chu 2023). The racial basis of how such an idea was put into practice can be gleaned from the discouragement of mixed marriage (see below), which clearly marked the Chinese as a different “race” from “Filipinos,” further conflating nationality and race while reviving old stereotypes and fears of Chinese attacks on Philippine communities:

(19) “I am not in favor of mixed marriage. I am not saying this with particular reference to the Filipinos, but also to Japanese, Chinese, and others of a different race marrying American girls.” (Graphic, June 4, 1936, 12–13)

(20) “The walls served the republic, such was the community designated, well on many an occasion; and at least once they served to preserve the city from annihilation at the hands of the Chinese, who had either been scared into revolt or had plotted the city’s destruction.” (American Chamber of Commerce Journal, June 1929, 7)

We can also observe in the data that ethnic roots of division between “Chinese” and “Filipinos” that extended to the provision of services were already established discursively (excerpt 21):

(21) “Será uno de los objetivos principales de ese Banco ayudar a los pequeños comerciantes chinos que no encuentran ningún apoyo de los e[sta]blecimientos bancarios ‘no-chinos’ que operan en estas Islas. ¿Cuándo seguiremos el ejemplo los filipinos?” [It will be one of the main objectives of that bank to help small Chinese traders who find no support from the “non-Chinese” banking establishments operating in these islands. When will we Filipinos follow suit?] (Estudio, April 7, 1923, 15)

On the one hand, there was at least implicit recognition during this period of Chinese longevity in Philippine society, as evidenced by residency or the ownership of schools, stores, and hospitals:

(22) “He eulogized the splendid treatment accorded the Chinese residents in Cabadbaran and expressed the hope that there will always be a peaceful relationship between the natives and the Chinese aliens in this part of the country.” (Graphic, January 4, 1934, 51)

(23) “Recently, all the Chinese and Chinese mestizo students of the Southern Institute formed an organization, the main purpose of which is to foster better relationships and understanding among themselves and to do something good for their Alma Mater.” (Graphic, September 3, 1936, 44)

While the Chinese were represented as alien residents, the American colonial period marks a transition in the representation of Moros in the sense that violence and backwardness are depicted as consequences of a Moro unsocialized into the US-American form of modernity, as discussed in Section V-2. Through this juxtaposition, the Americans and Filipinos of the time lauded Moros who were educated in the American-established school systems and conformed with the requirements of the national government, while dismissing those who fought against American rule as barbaric, rebellious, or criminals. In contrast to the Chinese, who were associated with the settings of urban life and the civilization of mainland China, the Moros, despite maintaining close trade links with the rest of Southeast Asia and entering into international treaties through the Sultan of Sulu, were not represented through an equivalent civilizational lens.

(24) “The survey revealed the deplorable conditions of the Moros in Cotabato and Lanao, particularly in the latter where the rules of hygiene and sanitation are entirely unknown to the Mohamedan Filipinos. Th[e] Moro houses need more ventilation and more windows. The plan of the Offic[e] to modernize the social lif[e] of the Moros appears to be a real need to effect the necessary changes in their ways of living.” (Adult Education, June 1939, 27)

(25) “Moros who have had a taste of education in the public schools, however, give an opposite opinion. They are heartily for the National Defense Act.” (Graphic, February 27, 1936, 48)

(26) “For years, the indifference of Moro parents toward the education of their children was the chief drawback of their own progress. Only the persistent striving of the government has made possible the conquest of that indifference.” (Graphic, January 4, 1934, 9)

(27) “It seems, it is said, that Moros cannot seem to bring themselves to recognize a woman as their leader because the Moros have antiquated beliefs with regards to the place of women in religion, in the government, and in society.” (Graphic, July 2, 1936, 17)

Furthermore, while the citizenship of Moros was already recognized at this point, the presence of moderate voices advocating for acceptance of the Moros (excerpts 28–30) did not allay the tension that existed as a result of the desire of the Americans to rapidly assimilate the Moros into the Philippine state. Tensions that came with accepting Christian Filipino judges or authorities did not dissipate easily, as can be seen in the Moros’ preference for an American governor and their distrust of courts (excerpts 29–30).

(28) “But what kind of people are Moros anyway? . . . Are they not, as proven, willing to lend a helping hand in the molding of the Philippines for a sound and secure future? . . . Take away your regional prejudice and be friends with them. Moros are also true-blooded Filipinos, and were born in the same archipelago where Rizal was born.” (Graphic, February 6, 1934, 24)

(29) “The assemblyman-datu believes the time inopportune for the appointment of either a Christian Filipino or a Moro governor as one would arouse the antagonism of the Moros and the other would intensify the existing factional enmity there.” (Graphic, September 3, 1936, 5)

(30) “Give the Moro incontrovertible proofs that he can be sure of justice at the hands of his Christian neighbors and the greater part of the so-called Moro problem will disappear.” (Graphic, January 4, 1934, 56)

V-3-3 Independence Period

Noteworthy characteristics of Philippine nationalism during the American period can be said to have stemmed from both the “official nationalism” of the US (Quibuyen 2008) and various attempts at Filipinization to counter US cultural dominance, which in its syncretic sociocultural expression consisted of selected reconstructed precolonial practices and values and Spanish-era religious expression and beliefs (Francisco 2015). Scholars such as Allan Lumba (2022) argue that this period presented a continuation of the conditional decolonization of Filipino nationalists that resulted in little structural reform to the economy or to ethnic categories—what Samuel Tan (2010, 69) would cast as neocolonialism, an “ideological brew [that] is a blend or synthesis of colonial and Filipino values including the justification of colonial prejudice against the non-Christian communities.”

The independence period is thus marked by a continuous sense of ambiguity in the use of the terms “Chinese,” “chino,” and “Intsik.” However, rather than indicating a domestic-oriented policy of conversion, the use of “Chinese” is associated with events in mainland China, as news began to encompass foreign affairs and developments of the Cold War, in association with an outward-looking vision of religious conversion. Other usages of the term pertaining to local affairs show the Chinese continuing to own businesses and various properties in the Philippines, with the term “Chinese” being increasingly combined with “Filipino” (Filipino-Chinese) in business and organization names. The corpus does not, however, cover the mass naturalization of aliens in 1975, which heralded the legal inclusion of Chinese migratory backgrounds in the concept of “Filipino.”

With regard to Moros, the independence period corpus distinguishes itself from the American-era corpus through eschewing the previous dichotomy between “educated” Moros and the “tribal” or “violent” other. The loss of the Americans and the political bargaining position that prominent Moros enjoyed while under American occupation meant that the Moros came under the rule of a majority Christian state, or gobirno a sarwang a tao (government of a different people) (Gutoc-Tomawis 2005, 11). For the Moros, it was a state which had considered Mindanao through a colonial lens, such as through Legislative Act 4197, the Quirino-Recto Colonization Act, which provided for the establishment of agricultural colonies on the island. The absence of particular collocations in the corpus is about as revealing as their presence. What was referred to by the Americans and Spanish-speaking elites as a Moro “problem” was left unmentioned in discourse, leaving two discursive possibilities: either the “problem” was considered “resolved” by the time of independence, or the notion of a “problem” ceased to emerge as a common way of speaking about Muslim Filipinos—in other words, the “problem” became symptomatic of the Philippine state. Christian settlers moved into Mindanao with the discourse of claiming “virgin” territories, and new settlers became a source of renewed conflict within the region. With the eschewing of the dichotomy aimed toward creating moral valuations based on the degree of regime acceptance, the discourse reverted to orientalist framing and a return of violent narratives.

(31) “He travelled far and wide and learned much about the land and its people, the Moros and the settler[s] from the Luzon provinces who came to claim virgin territory.” (Graphic, August 28, 1948, 32)

(32) “I walked down Pershing Plaza looking for Moros. I was told they were very peaceful people, although occasionally one gets jilted by a ranee, after which he goes home to take a bath, then runs through the streets shrieking in an unspeakable manner, hewing at the Christians with a gleaming kris. He generally continues this routine until he stops a dozen Constabulary bullets, at which point he goes home.” (Ateneo Quarterly, August 1950, 34)

(33) “The Moro espied him and rushed at him with fiery, bloodshot eyes, swinging his glistening ‘kris’ which, Mr. Flores saw, was already stained with blood at the end.” (Graphic, August 28, 1948, 7)

VI Conclusion

Both the quantitative and qualitative approaches employed here determined common features of minority representations in the discourse of “Moros” and “Chinese” that highlighted the persistence of stereotypes in print media throughout different colonial regimes and in the period from Philippine independence in 1946 to the 1970s. Such ideas were reflected mostly in media written in languages associated with power and upward mobility, such as Spanish and English, yet nuances were determined largely by era rather than linguistically. In particular, the results per time period reveal that even as different discourses developed with regard to Moros and Chinese in the Philippines, their signifiers retained a relatively stable core with shifting meanings depending on the nature of the political regime. This sensitivity of cultural representation to political tides was noted also by Vivienne Angeles (2016, 15), such as in the “fierce” Moro warriors depicted in the American-era films Brides of Sulu (1937) and The Real Glory (1939) vis-à-vis modern films in which Moros are “no longer isolated and confined to the south,” and was more determinant of changes in discourse than language-based attributions, with the possible exception of Filipino/Tagalog due to the paucity of digitized periodicals available for the language.

Semantic shifts between both colonial eras and the immediate independence period were not necessarily punctuated by a shift in discourse, even when somewhat conciliatory excerpts were to be found in American-era periodicals. Rather than a continuation of the dichotomous goal-oriented representation of the Americans, the image of the violent, strange, and uncivilized Moro persisted in discourse found in periodicals after 1946, albeit without the fatalism of the Spanish era. Instead, independence came with at least a tacit acceptance of the Moro as national fact, yet monolithic in character. The element of proximity is perhaps interesting to note in these representations: Chinese maintained a constant presence in urban centers of the country,13) while the Moro cultural communities were discursively separated geographically and politically from larger cities, where many of the periodicals’ publication offices were situated. Chinese representations were nevertheless noted for reproducing stereotypes and colonial attitudes. The portrayals were ambivalent: Chinese were lauded in an aspirational sense as rivals to “Filipino” businesspeople, recognized for their rootedness in the Philippines through adapting the language and setting up businesses, yet distrusted precisely because of their association with wealth and their perceived political or religious loyalties (Hau 2005). The discourses on minority identities until the 1970s demonstrate not only the twin role of colonial discourses and languages in shaping the contours of the national imaginary until well after formal colonialism, but the way in which ethnic and religious identities become essentialized through the repetition and reproduction of particular associations through discourse.

While this study does not cover nuances within its periodization or in the years following the 1970s (for contemporary discourses, see Gutoc-Tomawis 2005; Hau 2005; Angeles 2016; Chu 2023), the increased availability of digitized material and archived Internet sites brings ample opportunities for future studies to examine representations through time and text type. Recent years have brought a degree of resignification of Chinese mestizoness, in order to identify with the affluence of rising East Asian economies on the one hand, while increasing social and cultural capital for Chinese Filipinos on the other (Hau 2005, 521). Yet if the identification with “Asian-ness” serves as the epilogue to this story, it comes with limitations. While the corpus contains multifaceted references to China and its civilizational and economic status through references to art, political events, and trade, the Moros are not afforded a civilizational-material discourse—whether through references to the maritime trade network of Southeast Asia, Islamic civilization, or the Muslim ummah that stretches from Southeast Asia to the Middle East and North Africa. This suggests that the modern identification and recognition of regional “Asian” power is fraught, not only because of aspirational middle class identification with rising (East) Asian economies but because connections with Moros continue to be expressed in media through a lens that views the Philippine nation as bound with images of Christian and Muslim conflict and social incompatibility, insurgency, and colonialist narratives regarding the Southern Philippines. Resignification of Moro identities in the decades following World War II thus did not carry the implications of economic connections or regional affinities with ASEAN states with significant Muslim populations, and instead it reproduced colonial-era identity narratives that emphasized security issues, religious conflict, and geographical or cultural remoteness. In the conclusion of his book A Nation Aborted, Floro Quibuyen (2008, 383) forwards an interpretation of the Ilustrado writer José Rizal that eschews the outlines of the colonial chauvinism of the nation-state: Rizal’s exile serves instead as a community-building project that promoted an ethical national community anticolonial in the sense that it imagined a form of coexistence that went against the very definitions of the modern nation-state, not being based on a one-nation, one-language ideology or exclusivism. As far as minorities in the Philippines go, interrogating the colonial character of representation suggests an accompanying need to critically examine the continuity of political and material forms of oppression and exploitation that accompanied their genesis in the first place.

Accepted: January 30, 2024

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the University of Antwerp-VLIR-UOS and Global Minds Small Research Grant 2021 for the project “Decolonizing Media Discourses in the Philippines: Representations of Chinese and Muslim Minorities,” and the University of the Philippines FRASDP grant for supporting this research.

References

Abinales, Patricio. 2010. Orthodoxy and History in the Muslim-Mindanao Narrative. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.↩ ↩

Agoncillo, Teodoro A. 1974. Filipino Nationalism: 1872–1970. Quezon City: R.P. Garcia Publishing Co.↩

Anderson, Benedict. 1991. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.↩ ↩

Ang See, Teresita and Go Bon Juan. 2015. The Ethnic Chinese in the Philippine Revolution. In More Tsinoy than We Admit: Chinese-Filipino Interactions over the Centuries, edited by Richard T. Chu, pp. 133–172. Quezon City: Vibal Foundation.↩

Angeles, Vivienne S. M. 2016. Philippine Muslims on Screen: From Villains to Heroes. Journal of Religion & Film 20(1). https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol20/iss1/6, accessed January 15, 2024.↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

―. 2010. Moros in the Media and Beyond: Representations of Philippine Muslims. Contemporary Islam 4: 29–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11562-009-0100-4.↩ ↩ ↩

Anthony, Laurence. 2019. AntConc (Version 3.5.8). Tokyo: Waseda University. https://www.laurenceanthony.net/software, accessed September 29, 2020.↩ ↩

Blumentritt, Ferdinand. 1890. Mapa Ethnográfico Del Archipiélago Filipino [Ethnographic map of the Philippine Archipelago]. Boletín de La Sociedad Geográfica de Madrid [Bulletin of the Geographic Society of Madrid] 38: 43. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demographics_of_the_Philippines#/media/File:Blumentritt_-_Ethnographic_map_of_the_Philippines,_1890.jpg, accessed June 30, 2024.↩

Chu, Richard T. 2023. From “Sangley” to “Chinaman,” “Chinese Mestizo” to “Tsinoy”: Unpacking “Chinese” Identities in the Philippines at the Turn of the Twentieth-Century. Asian Ethnicity 24(1): 7–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/14631369.2021.1941755.↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

―. 2002. The “Chinese” and “Mestizos” of the Philippines: Towards a New Interpretation. Philippine Studies 50(3): 327–370.↩ ↩

Collas-Monsod, Solita. 2018. Why Filipinos Distrust China. Philippine Daily Inquirer. November 24. https://opinion.inquirer.net/117681/why-filipinos-distrust-china, accessed January 10, 2024.↩

Constantino, Renato. 1969. The Making of a Filipino: A Story of Philippine Colonial Politics. Quezon City: Malaya Books.↩

Corpuz, Onofre D. 2005. The Roots of the Filipino Nation. Vol. 2. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

Crailsheim, Eberhard. 2020. Trading with the Enemy: Commerce between Spaniards and “Moros” in the Early Modern Philippines. Vegueta: Anuario de La Facultad de Geografía e Historia 20: 81–111.↩

Cruz, Frances Antoinette and Ortuño Casanova, Rocío. 2022. Philippine Periodicals. GitHub. https://github.com/minoritynarratives/philippine_periodicals/tree/word2vec, accessed June 30, 2024.↩

Davies, Mark. 2019. Corpus-Based Studies of Lexical and Semantic Variation: The Importance of Both Corpus Size and Corpus Design. In From Data to Evidence in English Language Research, edited by Carla Suhr, Terttu Nevalainen, and Irma Taavitsainen, pp. 66–87. Leiden: Brill.↩

De Govántes, F. 1877. Santuario y Convento de Guadalupe [Sanctuary and Convent of Guadalupe]. La Ilustración del Oriente. October 21, p. 3.↩

De los Reyes, Isabelo. 1899. El dictamen de la Comisión parlamentaria de los Estados-Unidos [The opinion of the United States Parliamentary Commission]. Filipinas Ante Europa [Philippines facing Europe]. November 10, p. 1.↩

Diaz, Gene, Jr. 2016a. Stopwords-Es. GitHub. https://github.com/stopwords-iso/stopwords-es/blob/master/stopwords-es.txt, accessed January 15, 2024.↩

―. 2016b. Stopwords-Tl. GitHub. https://github.com/stopwords-iso/stopwords-tl/commit/39b8f37a571bfe76bf0f7bd22f19f91b4af76699, accessed January 15, 2024.↩

Dower, John. 2012. War without Mercy: Race and Power in Pacific War. New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.↩

Elizalde, María Dolores. 2019. Beyond Racial Divisions: Bridges and Intersections in the Spanish Colonial Philippines. Philippine Studies 67(3–4): 343–374.↩

Evangelista, Oscar L. 2002. Building the National Community: Problems and Prospects and Other Historical Essays. Quezon City: New Day Publishers.↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

Foucault, Michel. 1978. The History of Sexuality. Vols. 1–3. New York: Pantheon Press.↩

Francisco, Adrianne Marie. 2015. From Subjects to Citizens: American Colonial Education and Philippine Nation-Making, 1900–1934. PhD dissertation, University of California, Berkeley.↩ ↩

Fredrickson, George M. 2002. Racism: A Short History. Princeton: Princeton University Press.↩ ↩ ↩

Gutoc-Tomawis, Samira. 2005. The Politics of Labeling Philippine Muslims. Arellano Law and Policy Review 6(1): 7–19.↩ ↩ ↩

Hall, Stuart. 1997. The Spectacle of the “Other.” In Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices, edited by Stuart Hall, pp. 223–290. London, Thousand Oaks, New Delhi: Sage/Open University.↩ ↩

Hamilton, William L.; Leskovec, Jure; and Jurafsky, Dan. 2018. Diachronic Word Embeddings Reveal Statistical Laws of Semantic Change. arXiv:1605.09096v6 [Cs.CL]. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1605.09096.↩

Hau, Caroline S. 2018. Why I Distrust Solita Monsod’s “Why Filipinos Distrust China.” Esquire. November 27. https://www.esquiremag.ph/politics/opinion/caroline-hau-winnie-monsod-a2262-20181128-lfrm, accessed December 3, 2022.↩

―. 2005. Conditions of Visibility: Resignifying the “Chinese”/“Filipino” in Mano Po and Crying Ladies. Philippine Studies 53(4): 491–531.↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

Ileto, Reynaldo. 1979. Pasyon and Revolution: Popular Movements in the Philippines, 1840–1910. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.↩

Kahle, Philip; Colutto, Sebastian; Hackl, Günter; and Mühlberger, Günter. 2017. Transkribus: A Service Platform for Transcription, Recognition and Retrieval of Historical Documents. 14th IAPR International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, pp. 19–24. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICDAR.2017.307.↩

Kalaw, Teodoro M. 1912. Prólogo [Prologue]. In Sun Yat Sen: El Fundador de la República China [Sun Yat Sen: The founder of the Republic of China], by Mariano Ponce, pp. vii–xxi. Manila: Imprenta de la Vanguardia y Taliba.

Kramer, Paul A. 2006. Race-Making and Colonial Violence in the U.S. Empire: The Philippine-American War as Race War. Diplomatic History 30(2): 169–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7709.2006.00546.x.↩

Li Ke and Zhang Qiang. 2022. A Corpus-Based Study of Representation of Islam and Muslims in American Media: Critical Discourse Analysis Approach. International Communication Gazette 84(2): 157–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048520987440.↩

Lippi-Green, Rosina. 2012. English with an Accent: Language, Ideology, and Discrimination in the United States. New York: Routledge.↩

López-Calvo, Ignacio, ed. 2009. One World Periphery Reads the Other: Knowing the “Oriental” in the Americas and the Iberian Peninsula. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.↩

Lumba, Allan E. S. 2022. Monetary Authorities: Capitalism and Decolonization in the American Colonial Philippines. Durham and London: Duke University Press.↩ ↩

Majul, Cesar Adib. 1966. The Role of Islam in the History of the Filipino People. Asian Studies: Journal of Critical Perspectives on Asia 4(2): 303–315.↩ ↩

Mikolov, Tomas; Kai Chen; Corrado, Greg; and Dean, Jeffrey. 2013. Efficient Estimation of Word Representations in Vector Space. ArXiv:1301.3781v3 [Cs.CL], 1–12. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1301.3781.↩ ↩ ↩

Mojares, Resil B. 2006. Brains of the Nation: Pedro Paterno, T.H. Pardo de Tavera, Isabelo de los Reyes, and the Production of Modern Knowledge. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.↩ ↩ ↩