Contents>> Vol. 13, No. 3

Migratory Aspirations of the New Middle Class: A Case Study of Thai Technical Intern Training Program Workers in Japan

Jessadakorn Kalapong*

*เจษฎากร กาละพงศ์, Department of Inter national Studies, Faculty of Liberal Arts, Doshisha Women’s College of Liberal Arts, Kodo, Kyotanabe City, Kyoto 610-0395, Japan

e-mail: j-kalapong[at]dwc.doshisha.ac.jp

![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7575-6724

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7575-6724

DOI: 10.20495/seas.13.3_461

For decades, the migration of unskilled and low-skilled migrant workers from Southeast Asia to various destinations has continued to increase. Japan, which has long depended on Southeast Asian migrant workers, recruits workers through the Technical Intern Training Program (TITP). Migrant workers in this program undertake low-skilled 3D (dirty, dangerous, and difficult) tasks for lower wages and fewer rights than other foreign-worker groups. However, a closer look at their socioeconomic background prior to migration reveals they are often not simply unskilled labor. Using the case of Thailand, this paper shows that many belong to a newly configured middle class who, in terms of income, occupation, and educational attainment, have achieved certain levels of social and economic capital. Through ethnographic research on Thai TITP workers in Japan, this paper examines the relationships between migrants’ socioeconomic backgrounds in their home countries and their aspiration to migrate as unskilled labor. It clarifies how migration aspirations are shaped by their experiences within a new middle class through global cultural flows between Southeast and East Asia.

Keywords: international migration, migratory aspirations, Thai migrant workers, new middle class, Technical Intern Training Program

I Introduction

Since the 1970s, Southeast Asians have been migrating to participate in labor markets overseas (Asis and Piper 2008). The Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand, and more recently Vietnam are among the major source countries of migrant workers for many economies, particularly in the Middle East, East Asia, and even Southeast Asia (e.g., Malaysia, Singapore, and Brunei). Many of these workers perform unskilled and low-skilled or 3D (dirty, dangerous, and difficult) jobs, primarily to fill positions that citizens of the destination countries avoid. However, a closer look at the workers’ socioeconomic background before migration shows that this is not simply the flow of unskilled labor from developing to more developed countries. Many migrants have completed secondary or even tertiary education and held non-labor jobs in their home countries.1) They are not necessarily poor but rather part of a new middle class with upward mobility. This constitutes the principal question of this study: How do the dynamics in the migrant workers’ home countries affect their aspirations to migrate overseas for menial jobs?

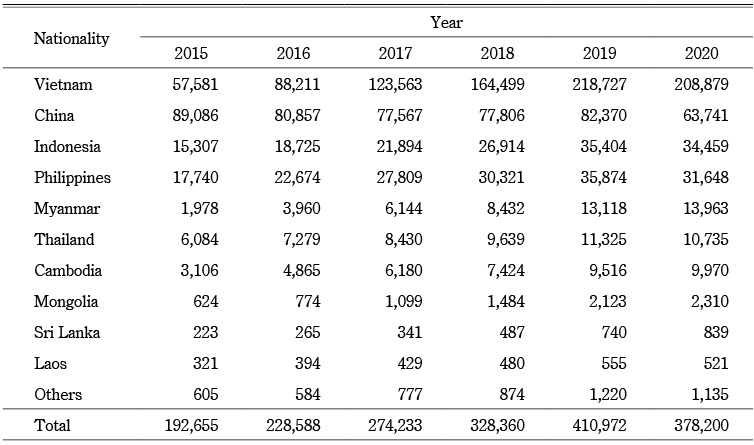

In recent years, Japan has become a top destination for Southeast Asian migrant workers. Many documented unskilled and low-skilled workers are recruited through the Technical Intern Training Program (TITP).2) Previous studies (e.g., Shipper 2010; Tanyaporn 2011; Kamibayashi 2013; Piyada 2021) suggest that TITP is a channel through which the Japanese government has engaged foreign workers as “trainees” to supply the labor market since 1993. Since its implementation, TITP has been criticized for serving as a channel for Japanese small and medium enterprises to hire foreign workers for 3D tasks at lower wages than other foreign workers and with limited professional and personal rights. There have been several cases of TITP workers fleeing their employers due to abuse, poor pay, and inability to switch employers or seek advice (Sunai 2019). Scholars have shown that TITP workers have limited contact with Japanese, since their Japanese-language skills are insufficient for communication at work or in society (Shitara 2021). Despite these criticisms, TITP workers in Japan have continuously increased, reaching more than 370,000 by 2020, even though the Covid-19 pandemic temporarily slowed cross-border travel that year, causing the number to drop slightly (see Table 1). Vietnam, China, Indonesia, the Philippines, Myanmar, Thailand, and Cambodia account for the majority of TITP workers. Previous studies have noted that the reasons for TITP workers migrating to Japan include the desire to earn a higher income and experience life abroad. Yet scholarship has not clarified the relationship between their socioeconomic background back home and their migration.

Table 1 Number of TITP Workers in Japan between 2015 and 2020

Source: Compiled from the change in the number of mid- to long-term residents with the residence status of

“Technical Intern Training (i),” “Technical Intern Training (ii),” and “Technical Intern Training (iii)”

between 2015 and 2020 (Japan, Immigration Service Agency 2020, 182; 2021, 184).

Incorporating class into the study provides an insight into TITP workers’ migration decision making based on the capital available at home. Disparities in the workers’ sources of social capital have a differential effect on their aspirations for migration (Pendergrass 2013). The perspective of class also provides an understanding of the influence of socioeconomic structures on the subjectivities of social agents, such as thoughts, perceptions, expressions, and actions. Pierre Bourdieu (2013) proposed that class habitus, as homogeneous systems of agents’ dispositions under homogeneous conditions, produces the subjectivities of social agents belonging to that class. This focus enables an understanding of migratory aspirations as emerging from subjectivities created by the socioeconomic circumstances shaping migrants’ lives and choices at home.

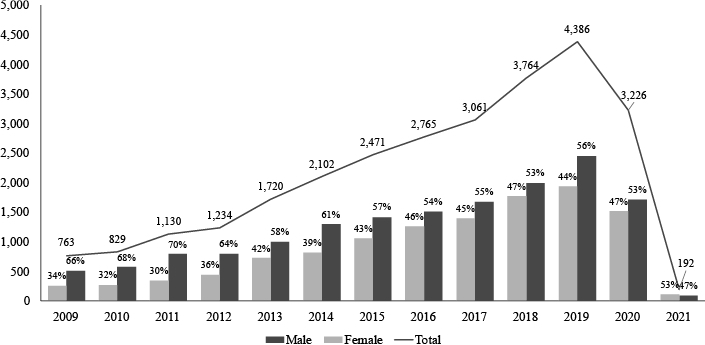

This paper focuses on Thai migrant workers in Japan under TITP and examines changes in their socioeconomic status—specifically, how their social class transformed and how this impacted their migratory aspirations. From the program’s inception, the trajectory of the number of Thai TITP workers increased in tandem with the total number of TITP workers (see Table 1). The ratio of female-to-male workers also constantly increased (see Fig. 1).3) Thailand’s current labor outflow coincides with its own demand for unskilled and low-skilled labor. Socioeconomic changes over the past three decades have resulted not only in a shift in the labor market but also in the configuration of a new class. This makes Thailand an important case study for examining the socioeconomic and cultural dynamics of migrants’ home countries and their influence on labor migration.

Fig. 1 Estimated Number and Percentage of Thai Male and Female Workers Permitted to Work in Japan under TITP from 2009 to 2021

Sources: Thailand, Department of Employment (2010; 2011; 2012b; 2013; 2014; 2015; 2016; 2017; 2018; 2019; 2021; 2022)

Note: The number of Thai TITP workers is estimated based on the number of job seekers permitted by the DOE to work in Japan, channeled through the DOE and recruitment agencies.

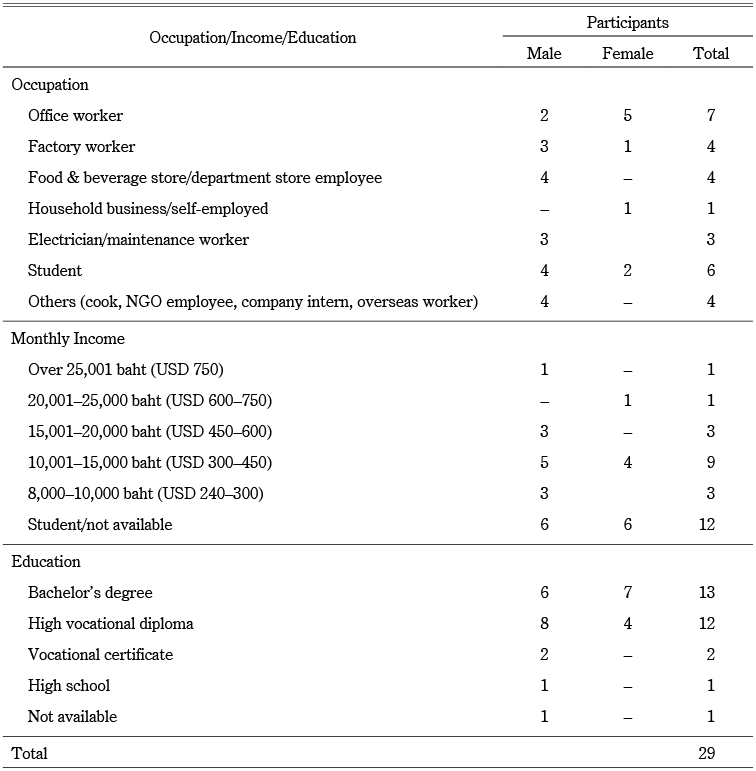

This paper is based on qualitative and quantitative data collected through fieldwork between July 2020 and June 2022 in Miyagi, Saitama, Aichi, Shiga, Mie, and Kumamoto Prefectures, with a total of 29 TITP workers (18 males and 11 females) from various sectors.4) Most participants were from Thailand’s northeastern provinces (20), with the rest from the northern (7), central (1), and eastern (1) regions. Most were aged 26–30 (12) and 21–25 (11) years, while the remainder were 31–35 (3) and 36–40 (3). They were introduced through the Thai network in Japan and the snowball sampling method. The ethnographic interview technique was used to elicit narratives from the workers regarding their lives before migration, their experiences working in Japan, and their expectations for the future. Additionally, questionnaire surveys were distributed to all 29 interviewees and an additional 19 respondents introduced through interviewees and the network of Thai. These consisted of multiple-choice questions designed to collect data on income, occupation, education level, and reasons for migration. While the sample sizes were relatively small, the results were compared to prior research on Thai migrant workers abroad, particularly to gain an insight into the present economic situation of such workers.5)

II Formation of the New Middle Class in Thailand

Thailand’s middle class has been identified differently by scholars in accordance with the country’s socioeconomic dynamics. Members of this class do not directly govern either the country or the peasantry (Nidhi 2011, 55), yet they are politically, economically, and culturally influential. The formation of this social class can be attributed to elements such as socioeconomic dynamics, regional development, nationalism, territorialization, and racialization. These processes, not always concurrent, have contributed to the upward mobility of different groups at different times. Previous studies suggest that the middle class consists of multiple groups of people from different ethnic and social backgrounds; thus, their consciousness is not always unified (Funatsu and Kagoya 2003; Nidhi 2011; Kanokrat 2021). This study differentiates between the old middle class, formed before the 1990s, and the new middle class, which emerged during the three subsequent decades.

Before the 1960s, Thailand’s middle class consisted of a small group of people such as bureaucrats and ethnic Chinese businessmen (Nidhi 2011, 55–58). The former had close historical ties to the ruling elites during the absolute monarchy. The latter were immigrants who, while barred from participating in administration due to their ethnicity, accumulated capital and forged ties with the state to safeguard their businesses. However, thanks to the nationalist policies during the 1910s–1940s, ethnic Chinese could assimilate into Thai ethnoideology (values, attitudes, and precepts that constitute Thainess) and increase their role in Thai politics in the following decades (Kasian 1997). Educational expansion in the 1960s and 1970s at the secondary and university levels led to the growth of the middle class. This benefited assimilated Chinese descendants the most, as it allowed several to enter the state bureaucracy (Anderson 1977, 17; Shiraishi 2008, 4–5). It also raised the social status of people from varied social backgrounds who had access to education, predominantly in urban areas (Funatsu and Kagoya 2003, 251–257). Thailand’s economic progress due to global finance and foreign direct investment from the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s led to an increase in the number of people working in the private sector as professionals, technicians, executives, managers, and white-collar office workers (Shiraishi 2008, 4–5).

In addition to their common educational and occupational traits, the Thai middle class of the 1990s shared consumption practices. Cars, condos, electronic gadgets, and fashion became the “standard package” representing their cultural identity (Shiraishi 2008). Most people possessing these forms of economic, social, and cultural capital lived in urban areas, particularly the Bangkok metropolitan area, where development was centered; rural areas, where most of the population were farmers, lagged behind.

From the 1990s, rural areas experienced significant social and economic development, which contributed to the emergence of a new middle class outside of the urban areas. In the 1990s, younger generations in rural areas moved to metropolitan areas to take up non-agricultural jobs. Traditional farmers, older people who relied on remittances from their migrant children, no longer engaged in full-time agricultural activities, thus diminishing their contribution to Thailand’s agricultural sector. Machinery-dependent farmers’ importance grew, and they became part of Thailand’s newly configuring middle class (Apichat et al. 2013; Fujita 2018).6) Over the years, they transformed from farmers to entrepreneurs at several market levels, including farmers who relied on wage labor for production and sales, owners of small agricultural product processing facilities, and intermediaries in the sale of agricultural products. As demand grew in rural areas, new occupations such as construction contractors, beauty salon owners, retailers, grocery store owners, and motor vehicle and agricultural machinery mechanics emerged (Attachak 2016). In the 2000s, most of the rural population comprised middle-income individuals earning more than 50 percent above the poverty line (Walker 2012, 36–44).

Another key factor affecting rural socioeconomic development and the background of Thai migrant workers was educational development. In the 1990s, the Thai government promoted secondary education in order to increase skilled labor. The 1997 Constitution and the 1999 National Education Act changed the requirement of six years’ compulsory education (primary school) to nine years (junior high school). Basic education was established at 12 years of attendance, the equivalent of high school. Thailand’s decline in fertility resulted in a smaller number of youngsters receiving schooling. Simultaneously, Thailand’s economic growth increased the government’s capacity to invest in education. Consequently, enrollment in Thailand’s educational system increased at all levels. The average duration of schooling increased from four years in 1967 to nearly 12 in 2007 (Michel 2010, 33–34). In short, improved access to education elevated rural people’s social and cultural capital—they now had degrees or certifications that qualified them for employment.

People in rural Thailand may be classified as middle class, but they have fewer educational, skill, and capital resources as well as fewer social and economic opportunities than urban dwellers. The income gap remains huge.7) Many in the emerging middle class work in the informal sector, such as household businesses and work for hire, with unsecured income (Apichat et al. 2013, 44–45). Some are employed in the public and private sectors but in low-level positions (Apichat and Anusorn 2017, 77–79). This socio-spatial disparity in prosperity is not only a result of the country’s uneven economic structure but also intersects with racialized territorialization on the domestic level. As a result of nation building throughout history, the formerly Lao ethnolinguistic population in rural Thailand’s Upper North and Northeast (Isan) as well as the Muslim population in the South have been subordinated to a lower position than Bangkok’s population (Glassman 2020). Thus, it can be said that the new middle class consists of predominantly ethnolinguistically inferior rural populations that are climbing up the socioeconomic scale with limited economic, social, and cultural capital.

This perspective on class formation in Thailand under an unequal socioeconomic and cultural structure is crucial to comprehending the migration of rural Thai today. Overseas migration is seen by the rural-based newly configuring class as a tool to overcome limitations at home.

III Thai Migrant Workers between the 1970s and 1990s

In migration studies Thailand is not depicted as a significant source of overseas workers, though Thai workers have participated in the migratory flow for decades. This section identifies the structural factors behind Thai workers, primarily from the agricultural sector, migrating as unskilled labor to Thai cities or abroad since the 1970s: these factors include social and economic conditions in Thailand, government policies in Thailand and destination countries, and the international political and economic situation.

In the 1960s, demographic changes along with counter-communist development projects in rural areas increased the domestic migration of rural Thai workers. The construction of roads connecting Bangkok with rural areas, particularly in the Isan region, enabled villagers to migrate to metropolitan centers. With the population growth in rural areas exceeding the capacity of the agricultural sector in the 1960s and severe constraints on the expansion of commercial agriculture and sale of local products during the following decade, both male and female villagers followed their relatives to Bangkok in search of work. Charles Keyes’s 1963 survey in an Isan village found that almost 30 percent of men under the age of 20 had experienced migration to Bangkok for a few months or years (Keyes 2012, 348–353).

While infrastructure development increased rural-to-urban mobility, the global economic and political situation in the 1970s created the first wave of international migration of Thai workers. The 1973 oil price increase necessitated the employment of migrant laborers, primarily from South and Southeast Asia, for massive construction projects in Gulf oil-producing nations (Amjad 1989, 3–4). Conversely, in Thailand the oil price increase caused economic stagnation. In addition, unemployment rose after 1975 with the withdrawal of American military bases that had employed many Thai, particularly in lawn care and labor services. The Thai government adopted a labor export policy for the Middle East in the early 1980s to alleviate economic stagnation (Baker and Pasuk 2014, 303). Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar, Iraq, the United Arab Emirates, and Libya accounted for more than 80–90 percent of Thai migrants abroad—mostly unskilled laborers in the construction and production industries (Wipawee 1988; Charit 1989; Surapun 2001). Previous studies on the first wave of rural Thai migrating overseas revealed that they came from a relatively low socioeconomic background in terms of income, occupation, and educational attainment. Most came from agricultural backgrounds, while others had worked as laborers, janitors, carpenters, bricklayers, and drivers. Almost 75 percent had completed primary schooling (Wipawee 1988, 95–100).

However, in the late 1980s growth in the Gulf countries began to slow. This, in conjunction with the Gulf War of 1990–91 and the global recession in the early 1990s, led to a decline in the demand for migrant workers. Also, Saudi Arabia, the largest labor market for Thai workers at the time, downgraded its diplomatic ties with Thailand following the theft of a Saudi prince’s jewels by a Thai worker as well as the murder of four Saudi diplomats and the disappearance of a Saudi businessman in Thailand in 1989 and 1990.8) Therefore, neither new nor reentry visas were issued to Thai workers for Saudi Arabia. Due to these economic and political constraints on both the international and bilateral levels, the flow of Thai workers to the Middle East decreased from the beginning of the 1990s. As a result, Hong Kong, South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore, which had begun industrializing in the 1970s and 1980s, became new destinations for Thai workers as they encountered labor shortages, particularly in construction and manufacturing (Kang 2000; Tsay 2000; Wong 2000).

Despite its earlier industrialization, Japan became one of the most popular Asian destinations for Thai migrant workers in the 1990s due to labor shortages there. To balance its need for migrant workers with its anti-foreigner sentiment, Japan refused to officially accept unskilled migrant workers. Instead, it created two “side doors”: for Japanese descendants or Nikkeijin from Latin America, and for TITP workers mostly from Southeast Asia and China (Higuchi 2019). Thus, TITP was the only official entry route for unskilled Thai workers—though, due to regulatory issues, the initial number of Thai TITP workers permitted to enter Japan was limited (Jessadakorn 2022). During the 1990s, most Thai workers in Japan were undocumented and had been smuggled in or overstayed their visas. In 1993 there were over 55,000 Thai overstayers in Japan,9) most of whom had become undocumented laborers. Women outnumbered men, most of them working in the sex and entertainment business. Males were generally employed at construction sites, manufacturing plants, stores, restaurants, and sex and entertainment facilities (Suriya and Pattana 1999; Pataya 2001).

A review of the history of Thai migrant workers suggests that labor shortages in destination countries, on the one hand, and the unemployment rates and labor export policy of the Thai government, on the other, historically involved Thai workers from rural areas in the labor migration flow both within and outside the country. The flow of Thai workers, particularly from rural areas, continues. The demand for migrant labor is increasing in many industrialized nations where depopulation is increasing, such as Japan. However, there have been numerous changes in Thailand during the past three decades that must be considered when studying the migration of Thai workers today.

IV Thai Migrant Workers Today as the New Middle Class and Their Migratory Aspirations

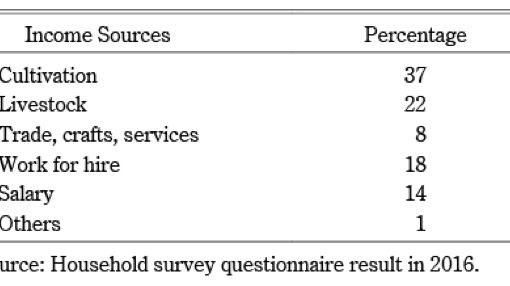

In the 1970s and 1980s, most Thai migrant workers overseas came from the rural agricultural sector and relatively poor socioeconomic backgrounds. Even though many Thai migrant workers today, particularly TITP workers in this study, come from rural areas, they have greater cultural and economic capital than the previous generation. Several belong to Thailand’s new middle class, which has emerged over the past three decades. Table 2 shows that none of the informants worked in agriculture or as laborers back in Thailand. Apart from the new graduates, who had never worked before, most informants had been employed as office workers, factory workers, service staff in food and beverage establishments, and electricians. Three male informants also had prior experience working abroad (in South Korea and Taiwan). With respect to income before migrating to Japan, all had earned more than 8,000 baht (approximately USD 240) per month,10) excluding new graduates. The minimum monthly income earned was around 8,000–9,000 baht (USD 240–270), while the maximum was 25,000–30,000 baht (USD 750–900). Half the informants earned more than the national average—9,450 baht (USD 284)—in 2019. Three of them earned approximately 1,000 baht (USD 30) less. Since the three were newcomers to their respective jobs at the time, presumably they would have earned more in the future.

Table 2 Occupations, Incomes, and Educational Backgrounds of Interviewees Before Coming to Japan

A report based on 2011–12 labor market research by the Department of Employment (2012a) revealed that most Thai technical intern trainees had a high vocational diploma, technical diploma, high school diploma, bachelor’s degree, or vocational certificate. This study found that most of the informants had completed tertiary education, with either a bachelor’s degree or a high vocational diploma. The university graduates’ majors were primarily in a business field, such as retail business, marketing, and hotel and tourism management. Vocational institution graduates had studied electronics, computers, plastic molding, etc. A 2019 labor force survey by Thailand’s National Statistical Office (2020b) showed that most bachelor’s degree students were employed in the wholesale and retail trade, motor vehicle and motorcycle repair, and manufacturing sectors, earning 7,500–20,000 baht (USD 224–598) per month. These results are similar to Wasana La-orngplew’s study (2018) on Thai migrant workers in the late 2010s, particularly in Australia and South Korea. While both generations of migrant workers performed unskilled labor, Wasana (2018, 55–56) noted a distinction between the educational backgrounds of the older and younger workers. The former were predominantly males from agrarian backgrounds with only a primary education, while the latter—children of these older-generation migrants—had at least a high school education. More than half held a vocational certificate or bachelor’s degree.

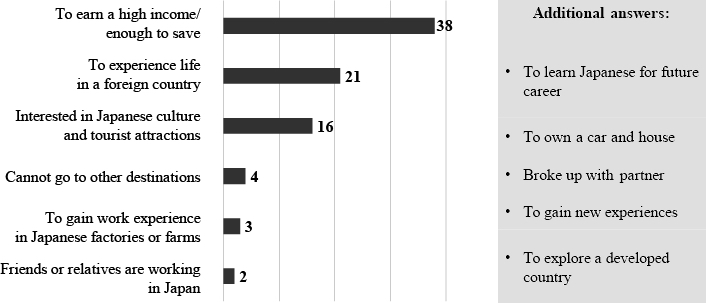

According to the questionnaire survey (see Fig. 2), the most frequently cited reason for migration was “To earn a high income/enough to save.” Since TITP employees are economic migrants, undeniably one of their primary reasons for coming to Japan is to earn money, despite having to work 3D jobs requiring more physical strength than they were used to in Thailand. Many are motivated by the desire to gain overseas living experiences and interact directly with Japanese culture. These economic and cultural motives correspond with findings from previous studies on TITP workers from Thailand and other nations (e.g., Shitara 2021; Piyada and Piya 2022). Nonetheless, I propose that their migratory aspirations should be treated as more complex than that. They should be understood as a spectrum of aspirations ranging from earning money and establishing opportunities for future careers to experiencing life in a different country. These aspirations manifest to varying degrees and overlap into multiple layers, and their structure can be examined along with the workers’ social mobility, class anxiety, and cosmopolitanism.

Fig. 2 Aspirations of TITP Workers with Regard to Coming to Japan

Note: Based on questionnaire survey responses from 48 Thai TITP workers.

V Structure of the New Middle Class’s Migratory Aspirations

V-1 Mechanism for Socioeconomic Mobility and Economic Independence

At one end of the aspiration spectrum, the desire to earn more suggests that the income disparity between Thailand and Japan remains relevant in explaining migration. Nevertheless, migration must also be examined through the lens of the workers’ class status back in Thailand. Also, there is a need to consider not only the income disparity between the home and host countries but also the disparity in socioeconomic structures in the home country. With their lower economic, social, and cultural capital, young workers use migration as a means to achieve social mobility back home by amassing a sum of money that is difficult to attain in Thailand. This is illustrated through the experiences of Oat and Pim.

Oat was a 23-year-old TITP worker from Udon Thani Province whose parents were sugarcane and cassava farmers. He graduated from Panyapiwat Technological College in Bangkok, after which he worked for a 7-Eleven store in Bangkok, earning approximately 10,000 baht (USD 300) monthly. Oat is a member of the emerging class who mobilized upward from his parents’ generation. Still, his income was insufficient for him to achieve his goal of starting a cow farm. Consequently, he quit his job and applied for a job in Japan in 2019 through a recruiting firm in Udon Thani. He was hired by a construction company in Miyagi Prefecture, earning 150,000–160,000 yen (USD 1,336–1,425) monthly. Although Oat earned significantly more than he had done back home, his transition from convenience store worker to construction worker was difficult. He explained why he chose to come to Japan despite knowing the difficulties:

I want to accumulate some money. I want to own a business in my hometown engaged in agriculture. Coming to Japan provides an opportunity to raise money for this purpose. I’m interested in starting a cow farm or something similar.

Oat introduced me to his friends who had applied for jobs through the same recruitment agency and were employed by the same construction company as him. Two of them expressed similar reasons for migrating: to save money to invest in land that they already possessed, where they wanted to cultivate commercial trees and other crops.

Thus, workers sometimes migrate to a country with higher pay in order to improve their status back home. The money they receive in exchange for their labor in the destination country is required for future businesses, and their experiences can help create further social and economic opportunities. In the case of Oat and his friends, a lack of capital hindered them from implementing their projects. In the past, when rural culture played a vital role in maintaining order and relationships among community members, a network of families and relatives could have resolved such issues. However, as Attachak Satayanuruk (2016) argues, socioeconomic changes have transformed rural communities such that they can no longer be characterized as the “tightly structured society” they once were.11) The decreasing reliance on kinfolk and the local community forces rural Thai to shoulder their entire economic burden independently. Thus, money enhances their socioeconomic status and economic independence.

Twenty-three-year-old Pim’s account reveals an alternative motivation for migrating. She graduated from a vocational school in Udon Thani Province with a high vocational diploma, after which she became a quality checker at a factory in Ayutthaya Province, earning more than 10,000 baht (USD 300) monthly. Although the job was not difficult, the salary was insufficient for Pim’s lifestyle, which included frequent pai thiao with friends. Pai thiao is a Thai term meaning “hanging out, going out, seeking entertainment outside, shopping, or traveling.”12) Added to her accommodation and food expenses, Pim’s pai thiao expenses made her feel her income was insufficient. After seeing her friend earn well working for a flower farm in Japan, she applied to TITP through a recruitment agency, the same one as Oat. She became employed on a vegetable farm in Aichi Prefecture, earning approximately 140,000 yen (USD 1,246) monthly. Pim anticipated that this income would enhance her lifestyle in Thailand, even though her living conditions in Japan were constrained.

Thus, it is anticipated that migrants’ higher incomes in Japan will improve not just their economic situation, as in Oat’s case, but also their social and cultural conditions back home. Especially for women, whose traditional gender role is closely tied to the domestic sphere (Whittaker 1999, 45–47), the capacity to pai thiao signifies sociocultural mobility in terms of growing independence.

V-2 Anxiety of the New Middle Class

The social mobility of rural dwellers indicates that their livelihoods have become closer to those of people in urban areas. Nonetheless, their inferior economic, social, and cultural capital compared to the urban middle class creates anxiety. This is related to the awareness of class formation and manifests itself in migration aspirations shaped by a sense of failure or lack in others’ eyes. Anxiety emerges from a distressing state of self-consciousness brought on by the sudden recognition of a discrepancy between certain norms and values and those considered superior (Felski 2000, 39). Due to their limited capital, young workers cannot enjoy the entire spectrum of the middle-class package, whether materially or culturally, which results in an experience of lack and motivates them to migrate as a coping strategy. This is evident from the narratives of Pat and Gift.

After graduating from a four-year university in Bangkok, 25-year-old Pat returned to his hometown in Sakon Nakhon Province and worked as a manager at his cousin’s coffee shop, earning approximately 15,000 baht (USD 450) monthly. However, Pat found his income insufficient for his life goals of a house, a car, a business, and financial independence. He sought a means to work abroad, as his father had previously done. He initially considered Korea, but his girlfriend, a Japanese-language teacher, suggested Japan. Pat applied for a position in Japan through the Department of Employment (DOE) and found a job at a Saitama Prefecture metal sheet pressing company, where he was responsible for pressing automobile components. His heavy work included cutting, pressing, and welding metal sheets. Pat earned approximately 100,000 yen (USD 890) per month after housing, pension, and health insurance expenses. He said that working in Japan for three to five years would allow him to achieve his goals in Thailand.

Pat’s aspiration to become a TITP worker can be explained by his pursuit of socioeconomic mobility through migration. He emphasized concrete goals: “to have a house, a car, a business, and financial independence after graduation.” Sai Hironori (2021) has suggested that the social dynamics in rural areas, which make lifestyles more consumerist amidst rising living costs, have generated a gap between the desires and incomes of young rural dwellers. However, material objectives may not be simply the result of rural areas transitioning to a market economy; they may be strongly tied to the standard middle-class package mentioned above. Rural workers’ limited capital makes it difficult for them to attain these objectives, resulting in a cultural gap between the new and old middle classes. Obtaining possessions and money or modern commodities such as a new iPhone—which many participants purchased while in Japan—serves to alleviate anxiety. Therefore, TITP workers’ engagement in migration can reduce the gap not only between their desires and income but also between the new and old middle classes.

Traveling abroad, whether for work, leisure, or temporary living, is regarded as part of the middle-class culture and frequently shown in Thai media. The film One Day (Thai: Faen de . . . faen kan khae wan diao), for example, tells the romantic story of two coworkers during a company trip to Hokkaido. It was a huge box office success in 2016 (Matichon Online 2017). Limited capital prevents young workers from enjoying this aspect of middle-class culture, but becoming an unskilled laborer in Japan can help, as expressed in Gift’s narrative. Gift was a 28-year-old TITP worker from Sukhothai Province who earned a bachelor’s degree in English literature from Kasetsart University in Bangkok. With no previous work experience, she applied for a job in Japan and was employed by a metal sheet pressing factory in Aichi Prefecture. Gift was motivated by her acquaintance Pear, who received a scholarship to study in Canada and posted details of her life there on Facebook:

You are a Facebook friend of Pear’s? I was acquainted with her younger sister. Pear is very talented, right? She won a scholarship to study in Canada. When I was younger, I was often envious of her. I also desired to travel overseas, just like she did. This was the dream of a rural girl. Indeed, Pear was my inspiration. Yet, I am not as talented as she is. Additionally, my family is not wealthy. As a result, I sought a way to travel abroad and found this program. It was simpler, and I was also able to earn money.

Like Gift, many participants explained that they came to Japan to work as laborers because their families were poor. It is reasonable to assume that their feelings stemmed from an aspiration for intergenerational social mobility. While the participants mobilized themselves, their parents’ social positions remained the same. In addition to the participants’ limited capital, their perception of being poorer than others made the culture of traveling abroad difficult for them to access. Migration helped to alleviate their anxiety by allowing them to travel internationally despite their inferior socio-occupational standing in the destination country. Being abroad—the consumption of foreign locations and cultures—helps to elevate social status (Kelly 2012, 175). It exposes migrants to the culture of developed countries and is viewed as a form of upward social mobility in and of itself.

V-3 Life Beyond the Boundaries of Local Communities

While the aspiration to go abroad can be partly explained by status anxiety, it should also be understood with reference to rural people’s cosmopolitan characteristics. Keyes (2012) coined the term “cosmopolitan villagers” to characterize rural people’s livelihoods in the late 2000s and early 2010s. Family members’ migratory experiences as well as information exchange via social media have led rural people to view themselves as part of a world larger than the one bounded by their home communities’ borders. With the global cultural flow—people moving, technological configurations, global capital disposition, electronic capabilities for producing and disseminating information, and ideological links—social agents experience and simultaneously mold a social space that Arjun Appadurai (1990, 296–297) termed the “imagined world,” the multiple worlds formed by the historically situated imaginations of individuals and groups across the globe. Thai rural people’s actual and imagined lives are more intertwined in social spaces than in Bangkok (Pattana 2014, 29).

A cosmopolitan life, or living in an imagined world, indicates at least two categories of rural people’s aspirations for migration. On the one hand, the connected spaces enabled by technology, notably the Internet and (mainly social) media, provide information about the migratory route to becoming TITP workers. On the other hand, as rural dwellers see themselves belonging beyond the confines of their local community, they may envision themselves migrating overseas for work, travel, experiencing life in other countries, skill development, or even self-discovery. For instance, Cake and Gift wanted to enhance their Japanese-language skills.

Cake was a thirty-year-old TITP worker from Loei Province, where her family ran a rubber farm. She graduated from Loei Rajabhat University with a bachelor’s degree in marketing, following which she worked as a general affairs staff member for Siam Denso Manufacturing, a Japanese company in Chonburi Province. After a year she moved to Musashi Paint, another Japanese company based in Chonburi Province, where she worked as a logistics officer, earning approximately 20,000 baht (USD 518) monthly. She learned about TITP through colleagues who were ex-TITP workers; they recommended she apply through the DOE, as this was cheaper than using a recruitment agency. However, Cake was unable to clear the DOE’s selection process. She then applied through a recruitment agency, paying approximately 200,000 baht (USD 5,180) in fees. In Japan, she was employed by an outsourcing company in Mie Prefecture that sent employees to automobile factories and warehouses for packing jobs. Her work was challenging, requiring her to move and wrap heavy automobile components. She explained her reason for coming to Japan:

I believe that everyone comes to Japan [as a TITP worker] for better pay. . . . We earn more money in this country than in Thailand, but my job in Thailand was far better. Additionally, the payment was fine. I came to Japan because I want to improve my Japanese skills to get a higher wage when I return to Thailand and apply for a job with a Japanese company. . . . Moreover, coming to Japan allows me to travel through the country. I always wanted to visit Japan, and because living in Thailand at the time was boring, I took the opportunity to come to Japan.

Gift described how she wanted to discover herself in Japan and worked to attain her ambition. She applied and prepared well for the DOE’s physical examination but failed the interview due to her lack of work experience. During the interview, Gift explained that she wanted to go to Japan to learn Japanese. As a fresh graduate, she was also eager to experience life abroad. However, the examiners said they would rather send candidates to work than to study. After the disappointment, Gift found a private recruitment agency, financially supported by her partner. However, the couple broke up when Gift extended her stay in Japan to five years. She explained her migratory aspirations as follows:

I chose this path because I wanted to continue discovering myself, and I believe that if he truly loved me he would have waited; I probably watched too many dramas. I have discovered what I value the most. My wage is lower than that at other companies, but I am satisfied. TITP is very similar to the Summer Work Travel Program,13) except that we are required to work in Japan for longer periods. My goal is to pass the JLPT N114) and communicate fluently in Japanese, just as the Japanese do. This may be far-fetched. Returning to Thailand to work as an interpreter is not my objective. I enjoy my life in Japan, from watching anime to freely traveling across the country and having Japanese friends. If possible, I will apply for an extension of my stay using the Specified Skilled Worker visa.

Cake’s and Gift’s accounts exemplify how young workers from rural areas are inspired to migrate owing to global cultural flows and how they regard their capacity constraints. While they are inspired to imagine themselves in a larger social sphere, they are aware of their limitations and hence choose to become migratory laborers to realize their aspirations. Migration is, therefore, a way of fostering social mobility, bridging the social gap for the new middle class and expanding their opportunities and capabilities beyond the structural constraints of their hometown and home country.

When exploring the cosmopolitan imagination, we should keep in mind that many participants chose Japan because they were familiar with it, as evident from the survey results and Gift’s and Cake’s narratives. In the survey questionnaire, “Interested in Japanese culture and tourist attractions” was one of the main responses (Fig. 2). Cake also explicitly stated her wish to visit Japan. Although Gift preferred Korea, she was familiar with Japan’s tourist attractions and anime, which made her appreciate living in Japan. This imaginary familiarity with Japan can be attributed to the transnational flow of Japanese culture, particularly popular culture, which has been accelerated throughout East and Southeast Asia since the 1990s with media globalization (Iwabuchi 2002). Japanese music, animation, manga, video games, and other consumer technologies have infiltrated the lives of not only the old but also the new middle class. These cultural products—which offer the emerging middle class a prism through which to imagine life in Japan (Appadurai 1996, 53–54)—might not directly attract Thai workers to move to Japan, but they have increased the presence of Japan in Thai’s cosmopolitan imagination.

VI Relationship between the Emergence of the New Middle Class and Their Migratory Aspirations

Incorporating a class perspective into examining migrants’ experiences reveals connections between socioeconomic and cultural structures and migratory aspirations. Over the past three decades, rural development in Thailand has changed people’s economic, social, and cultural lives. Contemporary young migrants can be characterized as the newly configured middle class in the Thai social structure. Inequality in the country’s development has created a disparity between the old middle class, who reside mostly in urban areas, and the new middle class, who come mostly from rural areas. The capabilities of rural people today are superior to those of the economically disadvantaged villagers of the past, but they still remain inferior to those of the urban population. Class anxiety and social mobility are, therefore, ingrained in the experiences of rural Thai workers. Cosmopolitanism—the ability to see and experience life outside the confines of one’s country—is growing among rural Thai workers as globalization continues to penetrate rural life. Within such complex class formation, migration aspirations manifest themselves as a spectrum of desires, such as earning higher income, seeking new opportunities, and experiencing life overseas. Overseas migration has emerged as a potential strategy for young workers from rural areas to navigate the limitations of Thailand’s sociocultural structure.

Through migration, Thai workers as social agents negotiate their identity and power in multilevel social spaces—their household, local community, and imagined world. Migrants and their families can elevate their socioeconomic status by using remittances to purchase new products and services, build new houses, invest in their businesses, etc. They can improve their opportunities upon returning home with new experiences and skills. They are more able to possess the same things or engage in the same activities as the old middle class, which helps alleviate their sense of lack. Migration also enables people to negotiate a superior social status in their home communities thanks to remittances from overseas. As evidenced by the cases of pholiang nok or Thai male migrant returnees—similar to balikbayan or Filipino returnees—the superior economic capacity and distinctive lifestyles of migrant returnees give them greater prestige within their communities (Nagasaka 2009; Panpat 2009). Migration enhances the sense of superiority that comes from experiencing the wider world (Aguilar 2018, 107–109), enabling a subjective upward mobilization and creating a distance from people lower down the social scale.

Migration also enables Thai workers to deal with the psychological changes that come with social and cultural changes. Mary Beth Mills’s (1999) study of Thai women’s rural-to-urban migration in the 1990s, for example, indicated that migrants’ needs, values, and concerns extended beyond family and economic survival to engagements with modernity. This prompted their desire for modern consumer commodities and stimulated their imagination regarding the urban employment possibilities created by migration. The emergence of the new middle class has increased rural people’s aspirations, especially with respect to educational attainment, accessibility to new media, and income (Appadurai 2004).

In a way, migration to low socio-occupational positions entails class descent, especially in terms of deskilling and deprofessionalization: for example, Oat, Pat, and Cake held more menial jobs in Japan than they had in Thailand. Some university graduates, such as Pat and Gift, could have used their degrees to get non-menial jobs in Thailand; instead, they put up with a deterioration in self-esteem while striving to attain their aspirations.

However, class should be examined transnationally. While migrants may have a low socioeconomic position in their destination country, they sometimes belong to a higher social class in their home country (Kelly 2012). Therefore, their class consciousness applies to both settings. In their narratives, Thai TITP workers acknowledged the downward mobility inherent in their migration but saw it as a means of achieving their goals, whether in terms of money or experiences that would aid in their upward mobility in Thailand. In addition, as with Nikkeijin workers who came from a more affluent socioeconomic position in their home country (Tsuda 2003), this deskilling and deprofessionalization was viewed as temporary. In other words, the migrants anticipated returning to a new middle-class life with more capital after their sojourn as menial workers in Japan.

Thailand is not the only nation where a new class is emerging. The phenomenon can be observed also in the Philippines, Indonesia, Vietnam, and other Southeast Asian labor-exporting countries. As others (see, for example, Rigg 1998) have shown, rural and urban boundaries in Southeast Asia are becoming blurred. Younger rural dwellers, in particular, move between their hometowns and metropolitan workplaces. Agricultural activities in Southeast Asian households have been substituted by non-agricultural activities that often propel rural livelihoods into higher incomes or even into the rural middle class—what this study calls the new middle class. The lives of migrant workers from rural areas become, in many ways, closer to those of the old middle class in their home countries. However, this does not mean that all rural people can gain wealth and generate high income or invest in education through migrating.15) Migratory aspirations, such as the desire to accumulate money, build a future career path, or experience a foreign culture, can be viewed as dispositions of the new middle class to pursue mobility, tackle status anxiety, and deal with the global cultural flow outside of the constraints imposed by the uneven structures at home.

VII Conclusion

Examining the relationships between migrants’ socioeconomic background in their home countries and their aspirations to migrate as unskilled labor provides an opportunity to reflect on the choices available to young Thai. A study of socioeconomic conditions in rural Thailand, where most Thai migrant workers come from, shows that the conditions for pioneer Thai migrant workers before the 1990s and those for migrant workers today are significantly different. Before the 1990s, rural areas were largely remote and people subsisted primarily through agriculture; migrant workers were surplus laborers in the agricultural sector. However, as villagers have progressed from being poor peasants to being part of the new middle class, their lives have become intertwined with the market economy and an imagined world that stretches beyond the confines of their local communities or even Bangkok. Many migrant workers today are better off than their predecessors in terms of income, occupation, and education. Yet their economic, social, and cultural capital is less than that of the old middle class, which emerged earlier in urban areas and established Thailand’s middle-class culture. In this sense, we need to keep our analytical lens on the migratory aspirations of Thai workers through the formation of the new middle class.

The spectrum of aspirations—from economic benefits to personal fulfillment, such as self-discovery and emancipation from old surroundings—is shaped by class mobility, class anxiety, and cosmopolitanism. Migration offers a chance for the new middle class to overcome class anxiety and gain upward mobility through accumulating economic, social, and cultural capital. Imagining life as part of the new middle class takes them beyond their communities through engagement with the global cultural flow.

Development in Southeast Asia has enabled the emergence of a new social class with a certain amount of social and economic capital, albeit less than the older middle class. It is members of this class that migrate overseas as unskilled and low-skilled workers. Leaving Thailand is a product of their agency in shaping desired identities and accessing power within their social spaces back home. By examining how migrants from Southeast Asia negotiate their class-related social status at home while migrating to low socio-occupational status in the destination, we can rethink the dynamics that shape their aspirations in the first quarter of the twenty-first century.

Accepted: November 10, 2023

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my gratitude to Associate Professor Mario Ivan López at the Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University, for his careful reading of this manuscript and for providing insightful comments on the clarity of the arguments.

References

Aguilar, Filomeno V., Jr. 2018. Ritual Passage and the Reconstruction of Selfhood in International Labour Migration. Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 33(S): S87–S130. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26531809.↩

Amjad, Rashid. 1989. Economic Impact of Migration to the Middle East on the Major Asian Labour Sending Countries: An Overview. In To the Gulf and Back: Studies on the Economic Impact of Asian Labour Migration, edited by Rashid Amjad, pp. 1–27. New Delhi: International Labour Organisation, Asian Employment Programme.↩

Anderson, Ben. 1977. Withdrawal Symptoms: Social and Cultural Aspects of the October 6 Coup. Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars 9(3): 13–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/14672715.1977.10406423.↩

Apichat Satitniramai อภิชาต สถิตนิรามัย and Anusorn Unno อนุสรณ์ อุณโณ. 2017. Raingan wichai chabap sombun khrongkan “kanmueang khon di”: khwamkhit patibatkan lae attalak thang kanmueang khong phusanapsanun “khabuankan plianplaeng prathet thai” รายงานวิจัยฉบับสมบูรณ์ โครงการ “การเมืองคนดี”: ความคิด ปฏิบัติการ และอัตลักษณ์ทางการเมืองของผู้สนับสนุน “ขบวนการเปลี่ยนแปลงประเทศไทย” [“Good man’s politics”: Political thoughts, practices, and identities of the “Change Thailand Movement” supporters]. Bangkok: Thailand Research Fund.↩

Apichat Satitniramai อภิชาต สถิตนิรามัย; Yukti Mukdawijitra ยุกติ มุกดาวิจิตร; and Niti Pawakapan นิติ ภวัครพันธุ์. 2013. Thopthuan phumithat kanmueang thai ทบทวนภูมิทัศน์การเมืองไทย [Re-examining the political landscape of Thailand]. Chiang Mai: Log in Design Work.↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

Appadurai, Arjun. 2004. The Capacity to Aspire: Culture and the Terms of Recognition. In Culture and Public Action, edited by Vijayendra Rao and Michael Walton, pp. 59–84. Stanford: Stanford University Press.↩

―. 1996. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.↩

―. 1990. Disjuncture and Difference in the Global Cultural Economy. Theory, Culture & Society 7(2–3): 295–310. https://doi.org/10.1177/026327690007002017.↩

Asis, Maruja M.B. and Piper, Nicola. 2008. Researching International Labor Migration in Asia. Sociological Quarterly 49(3): 423–444. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.2008.00122.x.↩

Attachak Satayanuruk อรรถจักร์ สัตยานุรักษ์. 2016. Luemta apak chak “chaona” su “phuprakopkan” ลืมตาอ้าปาก จาก “ชาวนา” สู่ “ผู้ประกอบการ” [Economic betterment: A transition from “farmer” to “entrepreneur”]. Bangkok: Matichon Public Company.↩ ↩

Baker, Chris คริส เบเคอร์ and Pasuk Phongpaichit ผาสุก พงษ์ไพจิตร. 2014. Prawatsat thai ruam samai ประวัติศาสตร์ไทยร่วมสมัย [A history of Thailand]. Bangkok: Matichon.↩

Bourdieu, Pierre. 2013. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Translated by Richard Nice. New York: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511812507.↩

Bowman, Catherine and Bair, Jennifer. 2017. From Cultural Sojourner to Guestworker? The Historical Transformation and Contemporary Significance of the J-1 Visa Summer Work Travel Program. Labor History 58(1): 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/0023656X.2017.1239889.↩

Charit Tingsabadh. 1989. Maximising Development Benefits from Labour Migration: Thailand. In To the Gulf and Back: Studies on the Economic Impact of Asian Labour Migration, edited by Rashid Amjad, pp. 303–342. New Delhi: International Labour Organisation, Asian Employment Programme.↩

Embree, John F. 1950. Thailand: A Loosely Structured Social System. American Anthropologist 52(2): 181–193. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1950.52.2.02a00030.↩

Felski, Rita. 2000. Nothing to Declare: Identity, Shame, and the Lower Middle Class. Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 115(1): 33–45. https://doi.org/10.2307/463229.↩

Fujita Wataru 藤田渡. 2018. Howaitokara nomin no shutsugen: Tai nambu no aburayashi saibai to hitobito no seikatsu sekai ホワイトカラー農民の出現―タイ南部のアブラヤシ栽培と人々の生活世界 [White-collar farmers: Oil palm cultivation and the living world in a southern Thai village]. Tonan Ajia Kenkyu 東南アジア研究 [Japanese journal of Southeast Asian studies] 55(2): 346–366. https://doi.org/10.20495/tak.55.2_346.↩

Funatsu Tsuruyo and Kagoya Kazuhiro. 2003. The Middle Classes in Thailand: The Rise of the Urban Intellectual Elite and Their Social Consciousness. The Developing Economies 41(2): 243–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1049.2003.tb00940.x.↩ ↩

Glassman, Jim. 2020. Class, Race, and Uneven Development in Thailand. In Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Thailand, edited by Pavin Chachavalpongpun. London: Routledge.↩

Higuchi Naoto 樋口直人. 2019. Rodo: Jinzai e no toshi naki seisaku no gu 労働―人材への投資なき政策の愚 [Labor: The foolishness of policies without investment in human resources]. In Imin seisaku towa nani ka: Nihon no genjitsu kara kangaeru 移民政策とは何か―日本の現実から考える [What is an immigration policy? Considering the case of Japan], edited by Takaya Sachi 髙谷幸, pp. 23–39. Kyoto: Jimbun Shoin.↩

Iwabuchi Koichi. 2002. Recentering Globalization: Popular Culture and Japanese Transnationalism. Durham: Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11vc8ft.↩

Japan, Immigration Bureau. 2003. Shutsunyukoku kanri: Shin jidai ni okeru shutsunyukoku kanri gyosei no taio 出入国管理―新時代における出入国管理行政の対応 [Immigration control: Immigration administration in the new age]. Tokyo: Ministry of Justice.↩

Japan, Immigration Service Agency. 2021. 2021 nemban “Shutsunyukoku zairyu kanri” 2021年版「出入国在留管理」 [2021 immigration control and residency management]. Tokyo: Ministry of Justice.↩

―. 2020. 2020 nemban “Shutsunyukoku zairyu kanri” 2020年版「出入国在留管理」 [2020 immigration control and residency management]. Tokyo: Ministry of Justice.↩

Jessadakorn Kalapong. 2022. Constraints on Migrant Workers’ Lives due to Structural Mediation in Labour Migration: A Case Study of Thai Technical Intern Trainees in Japan. Asian and African Area Studies 22(1): 73–100. https://doi.org/10.14956/asafas.22.73.↩

Kamibayashi Chieko. 2013. Rethinking Temporary Foreign Workers’ Rights: Living Conditions of Technical Interns in the Japanese Technical Internship Program (TIP). Working Paper, Institute of Comparative Economic Studies, Hosei University.↩

Kang Su Dol. 2000. Thai Migrant Workers in Korea. In Thai Migrant Workers in East and Southeast Asia 1996–1997, edited by Supang Chantavanich, Andreas Germershausen, and Allan Beesey, pp. 177–209. Bangkok: Asian Research Center for Migration.↩

Kanokrat Lertchoosakul. 2021. The Paradox of the Thai Middle Class in Democratisation. TRaNS: Trans-Regional and -National Studies of Southeast Asia 9(1): 65–79. https://doi.org/10.1017/trn.2020.16.↩

Kasian Tejapira. 1997. Imagined Uncommunity: Lookjin Middle Class and Thai Official Nationalism. In Essential Outsiders: Chinese and Jews in the Modern Transformation of Southeast Asia and Central Europe, edited by Daniel Chirot and Anthony Reid, pp. 75–98. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press.↩

Kelly, Philip F. 2012. Migration, Transnationalism, and the Spaces of Class Identity. Philippine Studies: Historical & Ethnographic Viewpoints 60(2): 153–185.↩ ↩ ↩

Keyes, Charles. 2012. “Cosmopolitan” Villagers and Populist Democracy in Thailand. South East Asia Research 20(3): 343–360. https://doi.org/10.5367/sear.2012.0109.↩ ↩

Matichon Online. 2017. Poet raidai nang thamngoen pi 2559 nai thai fang thet “kaptan amerika” khwa pai suan fang thai “luang phi chaet” khrong เปิดรายได้หนังทำเงินปี 2559 ในไทย ฝั่งเทศ ‘กัปตันอเมริกา’ ควาไป ส่วนฝั่งไทย ‘หลวงพี่แจ๊ส’ ครอง [Thailand’s 2016 box office was dominated by Captain America for foreign films and Luang phi chaet for Thai films]. Matichon Online. January 14. https://www.matichon.co.th/entertainment/news_426895, accessed October 10, 2021.↩

Michel, Sandrine. 2010. The Burgeoning of Education in Thailand: A Quantitative Success. In Education and Knowledge in Thailand: The Quality Controversy, edited by Alain Mounier and Phasina Tangchuang, pp. 11–37. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books.↩

Mills, Mary Beth. 1999. Thai Women in the Global Labor Force: Consuming Desires, Contested Selves. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.↩ ↩

Nagasaka Itaru 長坂格. 2009. Kokkyo o koeru Firipin murabito no minzoku-shi: Toransunashonarizumu no jinrui-gaku 国境を越えるフィリピン村人の民族誌―トランスナショナリズムの人類学 [Ethnography of Philippine villagers crossing borders: Anthropological transnationalism]. Tokyo: Akashishoten.↩

Nidhi Eoseewong นิธิ เอียวศรีวงศ์. 2011. Watthanatham thang kanmueang thai วัฒนธรรมทางการเมืองไทย [Thai political culture]. Institute of Culture and Arts Journal 2(24): 49–63.↩ ↩ ↩

Panpat Plungsricharoensuk พรรณภัทร ปลั่งศรีเจรญสุข. 2009. Phochai painok khuenthin kap kanniyam khwammai “khon pai klai” พ่อชายไปนอกคืนถิ่นกับการนิยามความหมาย “คนไปไกล” [Male transnational labor returnees and contested meanings of “khon pai klai” (who going far away)]. Social Sciences Academic Journal 21(2): 59–100. https://so04.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/jss/article/view/173138, accessed July 15, 2024.↩

Pataya Ruenkaew. 2001. Towards the Formation of a Community: Thai Migrants in Japan. In The Asian Face of Globalisation: Reconstructing Identities, Institutions, and Resources: The Work of the 2001/2002 API Fellows, edited by Ricardo G. Abad, pp. 36–47. [Tokyo:] Nippon Foundation.↩

Pattana Kitiarsa พัฒนา กิติอาษา. 2014. Su withi isan mai สู่วิถีอีสานใหม่ [Isan becoming: Agrarian change and the sense of mobile community]. Bangkok: Vibhasa.↩

Pendergrass, Sabrina. 2013. Routing Black Migration to the Urban US South: Social Class and Sources of Social Capital in the Destination Selection Process. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 39(9): 1441–1459. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2013.815426.↩

Piyada Chonlaworn. 2021. Cheap and Dispensable: Foreign Labor in Japan via the Technical Intern Training Program. jsn Journal 11(1) (June 27): 33–49. https://doi.org/10.14456/jsnjournal.2021.3.↩

Piyada Chonlaworn and Piya Pongsapitaksanti. 2022. Labor Migration from Thailand to Japan: A Study of Technical Interns’ Motivation and Satisfaction. Kyotosangyodaigaku ronshu: Shakai kagaku keiretsu 京都産業大学論集. 社会科学系列 [Kyoto Sangyo University essays. Social science series] 39: 379–397.↩

Rigg, Jonathan. 2016. Challenging Southeast Asian Development: The Shadows of Success. New York: Routledge.↩

―. 1998. Rural-Urban Interactions, Agriculture and Wealth: A Southeast Asian Perspective. Progress in Human Geography 22(4): 497–522. https://doi.org/10.1191/030913298667432980.↩

Sai Hironori 崔博憲. 2021. Nichijo no naka no iju rodo: Tai-jin gino jisshu-sei o chushin ni 日常のなかの移住労働―タイ人技能実習生を中心に [Migrant labor in daily life: Focusing on Thai technical intern trainees]. In Nihon de hataraku: Gaikoku-jin rodo-sha no shiten kara 日本で働く―外国人労働者の視点から [Working in Japan: From the perspective of foreign workers], edited by Ito Tairo 伊藤泰郎 and Sai Hironori 崔博憲, pp. 199–230. Kyoto: Shoraisha.↩

Shipper, Apichai W. 2010. Contesting Foreigners’ Rights in Contemporary Japan. North Carolina Journal of International Law and Commercial Regulation 36(3): 505–556.↩

Shiraishi Takashi. 2008. Introduction: The Rise of Middle Classes in Southeast Asia. In The Rise of Middle Classes in Southeast Asia, edited by Shiraishi Takashi and Pasuk Phongpaichit, pp. 1–23. Kyoto: Kyoto University Press.↩ ↩

Shitara Sumiko 設楽澄子. 2021. Kita no daichi no Betonamu-jin: Gino jisshu-sei to Hokkaido no chiiki shakai ni tsuite kangaeru 北の大地のベトナム人―技能実習生と北海道の地域社会について考える [Vietnamese in Hokkaido: Technical intern trainees and local society in Hokkaido]. In Chiiki kenkyu e no apurochi: Gurobaru sausu kara yomitoku sekai josei 地域研究へのアプローチ―グローバル・サウスから読み解く世界情勢 [Approaches to regional studies: Understanding the world situation from the Global South], edited by Kodamaya Shiro 児玉谷史朗, Sato Akira 佐藤章, and Shimada Haruyuki 嶋田晴行, pp. 121–136. Kyoto: Minerva Shobo.↩ ↩ ↩

Sunai Naoko 巣内尚子. 2019. “Shisso” to yobu na: Gino jisshu-sei no rejisutansu 「失踪」と呼ぶな―技能実習生のレジスタンス [Don’t call it “disappearance”: The resistance of technical intern trainees]. Gendai shiso 現代思想 [Contemporary thought] 47(5): 18–33.↩

Surapun Suwanpradid สุรพันธ์ สุวรรณประดิษฐ์. 2001. Khwamruammue thangdanraengngan rawang thai taiwan rawang pi phutthasakkarat 2534–2542 ความร่วมมือทางด้านแรงงานระหว่างไทย-ไต้หวัน ระหว่างปี พ.ศ.2534–2542 [Thailand-Taiwan cooperation on labor forces, 1991–1999]. Master’s thesis, Chulalongkorn University.↩

Suriya Smutkupt สุริยา สมุทคุปติ์ and Pattana Kitiarsa พัฒนา กิติอาษา. 1999. Manutsayawitthaya kap lokaphiwat: ruam botkhwam มานุษยวิทยากับโลกาภิวัตน์: รวมบทความ [Anthropology and globalization: Thai experiences]. Nakhon Ratchasima: Thai Studies Anthropological Collection, Institute of Social Technology, Suranaree University of Technology.↩

Tanyaporn Budsaen ブドセン・タンヤポーン. 2011. Gaikoku-jin kenshu gino jisshu seido: Zainichi Tai-jin kenshusei no genjo to kadai 外国人研修技能実習制度―在日タイ人研修生の現状と課題 [Foreign trainees and technical internship programs: The case of Thai trainees]. Ningen bunka sosei kagaku ronshu 人間文化創成科学論叢 [Journal of the Graduate School of Humanities and Sciences] 14: 311–319.↩

Thailand, Department of Employment. 2022. Sathiti chatha ngan 2564 สถิติจัดหางาน 2564 [Yearbook of employment statistics 2021]. Ministry of Labour, Thailand.↩

―. 2021. Sathiti chatha ngan 2563 สถิติจัดหางาน 2563 [Yearbook of employment statistics 2020]. Ministry of Labour, Thailand.↩

―. 2019. Sathiti chatha ngan 2561 สถิติจัดหางาน 2561 [Yearbook of employment statistics 2018]. Ministry of Labour, Thailand.↩

―. 2018. Sathiti chatha ngan 2560 สถิติจัดหางาน 2560 [Yearbook of employment statistics 2017]. Ministry of Labour, Thailand.↩

―. 2017. Sathiti chatha ngan 2559 สถิติจัดหางาน 2559 [Yearbook of employment statistics 2016]. Ministry of Labour, Thailand.↩

―. 2016. Sathiti chatha ngan 2558 สถิติจัดหางาน 2558 [Yearbook of employment statistics 2015]. Ministry of Labour, Thailand.↩

―. 2015. Sathiti chatha ngan 2557 สถิติจัดหางาน 2557 [Yearbook of employment statistics 2014]. Ministry of Labour, Thailand.↩

―. 2014. Sathiti chatha ngan 2556 สถิติจัดหางาน 2556 [Yearbook of employment statistics 2013]. Ministry of Labour, Thailand.↩

―. 2013. Sathiti chatha ngan 2555 สถิติจัดหางาน 2555 [Yearbook of employment statistics 2012]. Ministry of Labour, Thailand.↩

―. 2012a. Raingan phonkanwichai talat raengngan pii 2554–2555 รายงานผลการวิจัยตลาดแรงงานปี 2554–2555 [Report of labour market research during 2011–2012]. Ministry of Labour, Thailand.↩

―. 2012b. Sathiti chatha ngan 2554 สถิติจัดหางาน 2554 [Yearbook of employment statistics 2011]. Ministry of Labour, Thailand.↩

―. 2011. Sathiti chatha ngan 2553 สถิติจัดหางาน 2553 [Yearbook of employment statistics 2010]. Ministry of Labour, Thailand.↩

―. 2010. Sathiti chatha ngan 2552 สถิติจัดหางาน 2552 [Yearbook of employment statistics 2009]. Ministry of Labour, Thailand.↩

Thailand, Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 2009. Ratcha-anachak sa u di arabia ราชอาณาจักรซาอุดีอาระเบีย [Kingdom of Saudi Arabia]. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Kingdom of Thailand. https://www.mfa.go.th/th/content/5d5bcc1c15e39c3060009fd4, accessed October 11, 2021.↩

Thailand, National Statistical Office. 2020a. Kansamruat phawa setthakit lae sangkhom khong khruaruean pho so 2562 thua ratcha-anachak การสํารวจภาวะเศรษฐกิจและสังคมของครัวเรือน พ.ศ. 2562 ทั่วราชอาณาจักร [2019 household socioeconomic survey, whole kingdom]. Ministry of Digital Economy and Society, Thailand.↩

―. 2020b. Kansamruat phawa kanthamngan khong prachakon thua ratcha-anachak traimat thi 4: tulakhom-thanwakhom การสำรวจภาวะการทำงานของประชากรทั่วราชอาณาจักร ไตรมาสที่ 4: ตุลาคม-ธันวาคม 2562 [The labor force survey whole kingdom, quarter 4: October–December 2019]. Ministry of Digital Economy and Society, Thailand.↩

Tsay Ching-lung. 2000. Labour Flows from Southeast Asia to Taiwan. In Thai Migrant Workers in East and Southeast Asia 1996–1997, edited by Supang Chantavanich, Andreas Germershausen, and Allan Beesey, pp. 140–158. Bangkok: Asian Research Center for Migration, Institute of Asian Studies, Chulalongkorn University.↩

Tsuda Takeyuki. 2003. Strangers in the Ethnic Homeland: Japanese Brazilian Return Migration in Transnational Perspective. New York: Columbia University Press.↩

Walker, Andrew. 2012. Thailand’s Political Peasants: Power in the Modern Rural Economy. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.↩

Wasana La-orngplew วาสนา ละอองปลิว. 2018. Kanmueang khong kan (mai) khlueanyai khong raengngan numsao thai การเมืองของการ(ไม่)เคลื่อนย้ายของแรงงานหนุ่มสาวไทย [Politics of (im)mobility of young Thai workers]. In Chiwit thangsangkhom nai kankhlueanyai ชีวิตทางสังคมในการเคลื่อนย้าย [Social life on the move], edited by Prasert Rangkla, pp. 44–78. Bangkok: Parbpim.↩ ↩

Whittaker, Andrea. 1999. Women and Capitalist Transformation in a Northeastern Thai Village. In Genders & Sexualities in Modern Thailand, edited by Peter A. Jackson and Nerida M. Cook, pp. 43–72. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books.↩

Wipawee Sripian วิภาวี ศรีเพียร. 1988. Kanwikhro thangsathiti kiaokap raengnganthai nai tawanokklang การวิเคราะห์ทางสถิติเกี่ยวกับแรงงานไทยในตะวันออกกลาง [A statistical analysis on Thai workers in the Middle East]. Master’s thesis, Chulalongkorn University.↩ ↩

Wong, Diana. 2000. Men Who Built Singapore: Thai Workers in the Construction Industry. In Thai Migrant Workers in East and Southeast Asia 1996–1997, edited by Supang Chantavanich, Andreas Germershausen, and Allan Beesey, pp. 58–107. Bangkok: Asian Research Center for Migration, Institute of Asian Studies, Chulalongkorn University.↩

1) See, for example, the cases of Filipino workers in Canada (Kelly 2012) and Vietnamese workers in Japan (Shitara 2021).

2) The Technical Intern Training Program (TITP) was officially established by the Japanese government in 1993 to allow Japanese employers to hire foreign workers as “trainees” and “technical interns.” In the 2009 amendment of Japan’s immigration law, the dual status of trainee and technical intern was replaced by the “technical intern training” residence status. Today, TITP workers are permitted to work in Japan for three to five years. They are employed in agriculture, fishery, construction, food manufacturing, textiles, and machinery, among other areas. The Japanese government plans to discontinue TITP and replace it with a new scheme, which is expected to be implemented by 2027. TITP workers are able to come to Japan until the new system is fully implemented.

3) Between 2009 and 2021, the ratio of Thai female to male TITP workers increased. Particularly in 2021, when only a small number of workers were permitted to cross borders due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the proportion of female TITP workers exceeded that of males.

4) Each participant is provided a pseudonym in the Thai nickname fashion to maintain their anonymity.

5) The limited number of narratives lead to some limitations in this paper. It is difficult to fully incorporate an analysis from other perspectives, such as gender, as they were not explicitly reflected in discussions with informants. The intersection between class and gender will form the basis of future research to pull out a more nuanced analysis.

6) Apichat et al. (2013) identified a new middle class in Thailand by using an income indicator of 5,000–10,000 baht (about USD 147–295), while the average monthly income of Thai people was 6,239 baht (about USD 184) in 2009 (Apichat et al. 2013, 42–45). They noted that traditional farmers and laborers were the only two occupations that could not be classified as middle class because their incomes fell below that threshold.

7) According to the National Statistical Office of Thailand (2020a), the average monthly income per capita in 2019 was 9,450 baht (USD 284). The highest income group, comprising 42.7 percent of the population, had an average monthly income of 25,894 baht (USD 776), while the lowest income group, comprising 7.7 percent of the population, had an average monthly income of 2,890 baht (USD 86).

8) See Thailand, Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2009).

9) See Japan, Immigration Bureau (2003).

10) Based on 2021 exchange rates, this paper converts USD 1 to approximately THB 33 and JPY 112.

11) The term “tightly structured society” is used in contrast to “loosely structured social system,” which was coined by John Embree (1950) to characterize the individualistic nature of Thai culture. Embree described Thai society as lacking in regularity, discipline, and neatness. In the 1970s, many scholars argued against Embree’s claim by emphasizing the importance of Thai culture in controlling community members, which Attachak refers to as a “tightly structured society.”

12) For men in particular, it sometimes also implies going for commercial sex (see also Mills [1999]).

13) The Summer Work Travel Program is operated by the US Department of State. It allows overseas university students to live and work in the United States for up to four months, working low-wage jobs at hotels, restaurants, supermarkets, amusement parks, etc. (see Bowman and Bair 2017).

14) The Japanese-Language Proficiency Test (JLPT) is a twice-yearly test conducted worldwide to evaluate and certify non-native speakers’ proficiency in Japanese. The exam levels vary from N5 (needs the least linguistic proficiency) to N1 (requires the greatest).

15) See, for example, Rigg (2016, 23–53).