Advance Publication

Accepted: February 28, 2024

Published online: July 3, 2025

Contents>> Vol. 14, No. 2

Pocketing the Prize: Lingering Patterns of Prestige in Southeast Asian Studies

Jemma Purdey* and Antje Missbach**

*Australia-Indonesia Center, Monash University, Clayton, Victoria, Australia

e-mail: jemma.purdey[at]monash.edu

![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3388-7299

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3388-7299

**Faculty of Sociology, Bielefeld University, Universitätsstraße 25, 33615 Bielefeld, Germany

Corresponding author’s e-mail: antje.missbach[at]uni-bielefeld.de

![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1378-146X

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1378-146X

DOI: 10.20495/seas.25001

Browse “Advance online publication” version

While the field of Southeast Asian studies in US, European, and Australian academies faces challenges and decline, the discipline has developed significantly in Southeast Asia and elsewhere in Asia. Given the apparent shift in academic investment, this examination of patterns in awarding prizes for work in the field over the past two decades seeks to understand where “prestige” in the field is located. Assuming that prizes are more than just recognition for a scholar’s individual work, and that they also act as indicators for the development of Southeast Asian studies in a broader sense, this analysis concludes that prestige continues to be bestowed predominantly to those studying, working, and publishing in countries outside the region, particularly the United States. Our analysis reveals that overwhelmingly awardees of the preeminent book prizes given for excellence in Southeast Asian studies completed their higher research degree in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia (91 percent) and are currently affiliated with institutions in Europe, the United States, and Australia (94 percent). Although the number of institutions based in Asia, both old and new, has increased in recent decades, these institutions do not yet award book prizes akin to those under study, nor is there a regional association that does. It may be that a lack of institutionalized collaboration across these regional centers is one of the factors that indirectly boosts the ongoing dominance of institutions based in the US, Europe, and Australia. Rather than explaining this absence, in this article we seek to raise questions about the current state of Southeast Asian studies, who is shaping global ideas about Southeast Asia, and who currently—and will in the future—constitute their “communities of assessment” (Appadurai 2000).

Keywords: academic awards, knowledge production

Introduction

In 2014 the eminent America-based Thai scholar Thongchai Winichakul delivered the keynote address at the Association for Asian Studies (AAS) conference, an important gathering for scholars in the field in North America and arguably also globally. He observed that in the context of “post-Cold War conditions and paradigms,” Asian studies was undergoing significant change. He noted the development of academies in Asia and the proliferation of PhD programs in the region, meaning that the West was no longer the sole producer of scholars with great expertise in, or knowledge about, Asia. Though he gave no timeline, Thongchai (2014, 883) predicted, “It is very likely that Asian studies in Asian countries will become more important in global scholarship.” He recounted, anecdotally it should be noted, that within the Western (“Euro-American and Australian”) academy students in classrooms studying Asia were more and more likely to be from Asia and likewise taught by lecturers from there. He highlighted the ongoing imbalance in intellectual relationships between scholars in the West and those in Asia. Whilst his speech was in part based on observations and extrapolations, his message was prescient:

The intellectual relationship in Asian studies between the Euro-American and Asian academies is complicated by the ongoing hegemony of the West, thanks to the lasting legacies of the colonial and Cold War foundations of academia, and the reactions to such hegemony and the variety of alternatives in Asia . . . [T]he friction in this relationship is likely to become an important factor in the production of scholarship in Asian studies. How the effects will play out is beyond my ability to foresee. But we should pay attention to this issue and let our discussions begin. (Thongchai 2014, 891)

This article seeks to contribute to the ongoing discussion sparked by Thongchai and many others who have addressed the global power asymmetries in knowledge production in great depth, including the “geopolitics of knowledge” (Mignolo 2002), its (neo)colonial extractivism (Melber 2018), its “competition fetish” (Shahjahan and Morgan 2016), and the “machineries of neoliberal academia” (Burman 2018, 60) that seek to enhance the race for more and faster knowledge production. Addressing parochialism within the origin story, structures, and pedagogy of area studies is an ongoing project with which a vital literature and debate has been deeply engaged for several decades (Heryanto 2002; Jackson 2019; Fleschenberg and Baumann 2020). In response to criticism of the power structures underlying Western (or Euro-centric or US-centric or even Australia-centric) knowledge production, the field has rightly continued to confront its past and consider a future located in Southeast Asia and elsewhere in Asia. In the region itself, governments, individual scholars, and networks have embarked on establishing the requisite institutional frameworks for research and teaching centers, publications, and associations for the development of the field of study.

Whilst these theoretical debates continue, critical empirical examination is needed to document and analyze progress and emancipatory claim-making from within the Southeast Asian academy and elsewhere in Asia. We are interested to learn how much, if anything, has changed in response to this debate. In this article we scrutinize the current state of the relationship between the “local” academy and the “Western” academy and ultimately its impact on the production of knowledge. The underlying question driving our explorations concerns who is “shaping global ideas about Southeast Asia” (Farrelly 2018, 8) and who currently—and will in the future—constitute their “communities of assessment” (Appadurai 2000).

Investigating these questions demands a broad, multiregional, and multifaceted approach, including a combination of surveys, qualitative biographical studies, and mobility mapping. This article contributes toward this larger goal of assessing the progress of these developments locally, and the ways in which they are being seen in the broader context of the field globally, by tracing the awarding of prestigious book prizes for Southeast Asian studies from 2000 to 2022. The production of academic outputs, and especially the recognition and appreciation of produced knowledge, provides an indicator of the state of the field.

This article is structured along the following themes: first, we discuss the significance of networks and mobility in academia more generally to apprehend the impacts of the flows of Southeast Asian undergraduate and postgraduate students into US, Australian, and European academies on the epistemology of the field. Second, we shift the focus to book prizes and symbolic capital to offer a short history of Southeast Asian studies book prizes. Third, we present our empirical findings to illustrate clear patterns of prestige in current Southeast Asian studies. Fourth, in order to further analyze our findings, we return to the issues of politics, prizes, and prestige in academia; and fifth, we ask what the development of local academies for Southeast Asian studies in East and Southeast Asia means for knowledge production on Southeast Asia and whether these emerging centers are interested in challenging the prevalent dominance in one way or another. We close this article with a short conclusion and suggestions for future investigations about the de-Westernization of the institutional framework globally, which we argue would inhibit deeply ingrained patterns of prestige.

Networks and Mobility

Our focus is on the preeminent prizes for books published in Southeast Asian studies. A survey of book prizes in the field helps to illustrate not only who was awarded but where the awardees studied and now work. Based on our findings, which are outlined in detail below, most prizes are awarded to scholars trained and based in1) the US, the UK, Europe, and Australia. The findings further show that authors from the Global South (“insiders”) who are affiliated with institutions in the Global North tend to dominate the field (publication count and citations), while homeland-based scholars are in the periphery (“outsiders”). With their insider-leaning hybrid positionality, overseas scholars from the Global South in the Global North accrue more network-mediated benefits than their colleagues residing in the Global South and perhaps even more than their Global North colleagues who lack the hybrid positionalities (Arnado 2021). We pose the question, when will we expect to see symbols of prestige transferred from these countries in the Global North to an academy based in the region? We argue that prizes serve as signposts for such mobilities and ultimately the development of the discipline both within and outside US, Australian, and European institutions. The book prize, in this regard, becomes a litmus test for institutional change and inclusivity and for what knowledge is valued and ultimately accorded prestige.

For the purpose of this study, our interest is not in the subject matter or discipline of the awarded books. Neither do we seek to make a determination about the identity, ethnicity, or nationality of the individual authors. Taking into consideration that some authors could hold more than one citizenship makes the question of identity far more complex and is beyond the scope of this article. Whilst such analysis is undoubtedly critically important in order to answer broader questions about the future of Southeast Asian studies, we believe it should be reserved for another more deeply biographical study including whole-of-life interviews and career tracking.2) In this instance, our concern is with the institutional representation reflected in prize giving and receiving and its requisite association with prestige in the field.

Support for research institutions, publishing, and higher-degree teaching programs is a key step toward creating what Arjun Appadurai (2000) described as a “community of assessment” and Robert Cribb (2005) termed “circles of esteem” within the academy, whereby the rules and parameters for a discipline or field of research are established and its membership decided. We ask, where is the field of Southeast Asian studies on this journey so far? Is it moving toward a process of institution building within Southeast Asian studies in the region that includes the creation of the necessary circles of esteem within its academy, in order to ultimately establish its own community of assessment capable of judging its own symbols of prestige? Will Southeast Asian studies in these relatively new centers ever catch up with or even overtake the declining (in terms of student and faculty numbers) centers of Southeast Asian knowledge production in the West? What role do institutions such as professional associations, research institutes, publishers, scholarship programs, award programs, and governments play in promoting and directing Southeast Asian studies?

Though intrinsically linked to a broader discussion on the future of Southeast Asian studies, our article is intended not so much to trace epistemological trajectories as to look for signs of the impacts of the transnational collaboration, scholarly exchange, and academic interconnections that Carlo Bonura and Laurie Sears (2007) hoped would shift the discipline from its unidirectional path.

Book Prizes and Symbolic Capital

Receiving a top award in one’s field translates to academic currency with significant bearing on the career trajectory of the recipient. In this way, the awardees of such prizes are not just examples of what is regarded as good science but also trailblazers for the future institutional development of the discipline. Where the recipients of these prizes choose to carry out their doctoral study and—also important—thereafter choose to pursue their careers correlates with the status and prestige of those institutions themselves. The book prize is only one of several signifiers/symbols of excellence and prestige in academia and elsewhere, bestowing what Pierre Bourdieu (1977, 179) called “symbol capital,” which “takes the form of prestige and renown.” Other symbols carrying this capital include fellowships, invitations for keynote speeches, publications in highly regarded journals and book series, for example, as well as career promotion and—as has been much discussed—citation metrics (Cribb 2005; English 2005). Whilst all these achievements most certainly benefit the individual scholar, we have chosen to highlight book prizes for what they reveal about the locus of prestige within Southeast Asian studies temporally, geographically, and on an institutional level as well as what they reveal about institutional development and legitimacy not only for beneficiaries but also for the givers of prizes (Best 2008).

At the AAS conference in March 2022, eight years after Thongchai’s keynote address, the prestigious Harry J. Benda Prize was awarded for the 37th time since its establishment in 1977 in honor of the pioneering Yale historian. Managed by a committee of the AAS, the Benda Prize was initially given biennially to a promising emerging scholar. Since 1991 it has been an annual award for a first book on Southeast Asia in the humanities and social sciences, and in 2022 it bestowed a US$1,000 prize on the awardee. The winner of the 2022 award was Teren Sevea for his Miracles and Material Life: Rice, Ore, Traps and Guns in Islamic Malaya (Cambridge University Press, 2020). A decade earlier, in 2012, the winner was Karen Strassler for Refracted Visions: Popular Photography and National Modernity in Java (Duke University Press, 2010). In 2000 the award was given to Suzanne April Brenner for The Domestication of Desire: Women, Wealth, and Modernity in Java (Princeton University Press, 1998).

Though these book prizes were separated by decades, during which many observers highlighted key shifts in who was learning and teaching in this field, it remains the case that between 2000 and 2022 those recognized by the Benda Prize givers as the best “new” talent were all US based, as were their publishers.3) In the case of the Benda Prize, perhaps this is unremarkable for a number of reasons, including that it is given by a committee of the US-based AAS and most of the books are published by university presses with long and prestigious Southeast Asian lists (more on this below). Nonetheless, the competition is not limited to AAS membership. The Benda Prize (like all the prizes under study here) is open to authors from anywhere in the world without restrictions on nationality or institutional affiliation.

As already mentioned, for some time now debates within Asian studies have grappled with and called for a decentering/decolonization/de-Westernization of the field, with an emphasis on the “growing importance of Asia not only as the object of studies by the ‘first world’ academia but also as the producer of knowledge” (Thongchai 2014, 881). We acknowledge and embrace the ways in which, for many decades, the flow of scholars across borders has disrupted a reductionist understanding and blurred the boundaries of classification and origin for who is producing knowledge about Southeast Asia. As we seek to demonstrate, our small study was conceived with this very much top of mind.

The prizes under study here were selected for two reasons: eligibility for entry was open to English-language sole-authored books of original work (regarded as the pinnacle of quality research output), and there were no limitations on the authors’ nationality or place of residence.4) These prizes are the Harry J. Benda Prize, the ICAS Book Prize, the George McT. Kahin Prize, the EuroSEAS Book Prize, and the Asia Society’s short-lived Bernard Schwartz Book Award. Each prize was awarded by associations based in Europe and the US. Notably, the period under study saw a proliferation of prizes for Southeast Asian studies,5) whilst the number of publications6) in the field largely remained constant.

As mentioned, our focus was not only on the authors and books themselves but also on the institutions where the awardees undertook their PhD, the institutions in which they were based at the time of our research, and their publishers, as it is the latter who often decide which book to submit to a competition. Bearing in mind that many of the submitted, longlisted/shortlisted, and winning books are first books, it is likely that authors depend on the support and resources of their publishers to participate in competitions.

In seeking to understand where the field of study is positioned today—who is involved and what type of work is held in high regard—and what the future might look like, it is salient to consider the origins of the prizes. The following stories highlight the roles of key individuals, and the prizes still awarded in their honor reveal the potential of deeper biographical studies to tell us much more about the wider social, political, and cultural contexts—links between the imperatives of the nation-state and scholarship, for example—that ultimately enable and facilitate the production of knowledge.

The man for whom the aforementioned Benda Prize is named, Harry J. Benda, was a Czech Jewish refugee from Nazism. In the 1940s Benda found temporary sanctuary in colonial Netherlands Indies, from where he was later interned by the Japanese. After the war he migrated to New Zealand. In the early 1950s, Benda undertook his PhD at Cornell University’s then booming Modern Indonesia Program in the company of George McT. Kahin, Ruth McVey, Benedict Anderson, and Herb Feith (Purdey 2011). After Benda’s death at just 52 years of age, W. F. Wertheim, who had known him as a young man in the Netherlands Indies, opened his obituary to his friend by positioning him between the “old” and “new” worlds of colonial European and American traditions in Southeast Asian studies:

The postwar period has witnessed an impressive burgeoning of American scholarship on Indonesia, which was before the war largely the preserve of Dutch colonial experts. Among the prominent American students of Indonesian history, sociology and political science, Harry Benda occupied a special place, since in certain respects he formed a link between Dutch and foreign scholarship. (Wertheim 1972, 214)

Studies by Bonura and Sears (2007), McVey (1995), and many others provide critical accounts of the colonial projects of the European and US-American powers that sought to acquire knowledge of the cultures, languages, and histories of the peoples of Southeast Asia whom they governed—their subjects—and the lingering aftermath of this colonialist pursuit of “instrumental knowledge” (Bonura and Sears 2007, 15). As Heather Sutherland (2012, 106) explained in relation to Indonesian or Indology studies in the Dutch academy, “The origins of the teaching of Indonesian languages, ethnography and law at university level were pragmatic, driven by the need for more professionally qualified colonial officials.”

For the founders of Southeast Asian studies in the US—Kahin, Benda, Clifford Geertz—and the Australians John Legge, Jamie Mackie, and Herb Feith (also a European Jewish refugee), their first encounters with the region were tied to and shaped by World War II (Reid 2009; Purdey 2011) and thereby inextricably “inaugurated the field of Southeast Asian studies in the United States” (Bonura and Sears 2007). As Bonura and Sears (2007, 15) describe it: “WWII changed US attitudes toward Southeast Asia, where the Pacific war was being fought, rich natural resources were located and the battleground for the Cold War was slowly coming into focus.” Benda and his largely US-trained cohort from the 1950s went on to pen seminal texts in the study of the politics, nationalist histories, and cultures of the region. They established a community of scholars who formed the discipline and, most important, prescribed and rewarded its standards for excellence in the form of scholarships, fellowships, tenure, publishing contracts, and prizes. Seven decades later, what is the continuing legacy of this post-World War II project on Southeast Asian studies, particularly when it comes to defining excellence and patterns of prestige for the community of its contemporary adherents?

Our analysis of the small but highly prestigious collection of prizes for Southeast Asian studies indicates that the production of the most prized and thereby valued knowledge about the peoples and cultures of the region remains centered in the academy based in the US, Europe, the UK, and—to a lesser extent—Australia. The dominance of US-based and -trained scholars is hard to ignore. Observing this continuing pattern of awarding prestige made us wonder whether academic award committees and judges were still lagging behind in their oft-stated efforts to “decolonize” academia, particularly Southeast Asian studies in this case. Despite the rising intensity of the debate in recent decades, there appears to be little noticeable change in how quality is denoted. What are the enduring power structures in both the publishing institutions and quality-measuring award committees that may inhibit change? Are the book award committees gatekeepers who unconsciously act against the emancipatory trends of the discipline? Or is it the case that academia can decolonize as much as it wants, but as long as Western-based academic book publishers remain dominant, nothing much will change (Schöpf 2020)?

In the last two decades, there has been a proliferation of prizes for Southeast Asian studies and Asian studies more broadly. As already mentioned, the Harry J. Benda Prize, first awarded in 1977, is the longest-running major book prize for work on Southeast Asia. The AAS awards the prize annually to an “outstanding newer scholar from any discipline or country specialization of Southeast Asian studies for a first book in the field” (Association for Asian Studies 2019b). For 26 years this was the most significant and prestigious international book prize for emerging talent in Southeast Asian studies as recognized by those within the discipline.

In 2003 the International Convention of Asia Scholars (ICAS), based at Leiden University in the Netherlands, established the ICAS Book Prize (IBP) for outstanding publications in the field of Asian studies. Initially two book prizes were given biennially, the ICAS Social Science Award and ICAS Humanities Award, and also a prize for best dissertation in those disciplines; more categories of prizes have since been added.7) Indeed, as is the intention behind many prizes, ICAS hoped that they would “bring a focus to academic publications on Asia; to increase their worldwide visibility and to encourage a further interest in the world of Asian Studies” (International Convention of Asia Scholars, n.d.a.). However, the creators of the IBP had a further rationale for establishing the prize that went beyond promotion and celebration of talent in the field: “New awards must be justified by an argument that some additional, formal expression of esteem is needed or at least desirable” (Best 2008, 13). The ICAS website states the following:

Right from the start, the IBP was designed to be different in nature than the (few) prizes in the field of Asian studies at that time. The existing prizes were limited to particular regions or disciplines, and often named after one of the professorial stars in the field. Access to and judgement of the prizes tended to occur in a rather closed circle of familiarity, and was mostly resistant to outside interference. There was clearly room for improvement and innovation. (Van der Velde 2020)

Joel Best describes the proliferation of prizes as, in part, representing a process of legitimation, for “any group that feels its accomplishments are insufficiently appreciated . . . can establish its own awards for excellence. This helps ratify and display esteem both within the group and for others” (Best 2008, 15). More recently, ICAS has expanded its list of awards to include publications in languages other than English: “With this multilingual approach, in cooperation with a host of partners and sponsors worldwide, ICAS is increasingly decentring the landscape of knowledge about and in Asia” (International Convention of Asia Scholars, n.d.b.). ICAS Book Prizes are awarded also for books published in Chinese, French, Russian, Portuguese/Spanish, German, Japanese, and Korean. Of these eight languages, however, five are European—and so far, the list does not include a Southeast Asian language (International Convention of Asia Scholars, n.d.a.; n.d.b.). Since the prize was established, three books on Southeast Asian subjects have won the main Humanities and Social Science prizes, although more Southeast Asia-related works have been on other, also prestigious, shortlists for the dissertation prize and Colleagues’ Choice Award. For the purposes of this analysis, we have included only the books that claimed either of the two top prizes.

In 2007 the Association for Asian Studies created the George McT. Kahin Prize, to be given biennially “to an outstanding scholar of Southeast Asian studies from any discipline or country specialization to recognize distinguished scholarly work on Southeast Asia beyond the author’s first book” (Association for Asian Studies 2019a). The award was initiated to honor Kahin’s (1918–2000) contributions to the field of Southeast Asian studies by the Cornell University Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kahin’s friends and students, and the Southeast Asia Council of the Association for Asian Studies (Association for Asian Studies 2019a).8) As briefly mentioned, Kahin’s legacy looms large over Southeast Asian studies, and especially Indonesian studies, in the American academy and also globally. Kahin was a founding member of the preeminent Southeast Asia Program at Cornell University and the head of the Cornell Modern Indonesia Project in the early 1950s. The program—and Kahin himself—attracted students from around the world, in turn establishing an international network of Cornell-trained scholars in centers for Southeast Asian studies (Lev 2007).

In 2015 the European Association for Southeast Asian Studies (EuroSEAS) established two book prizes to be awarded at its conference—initially every three years and now biennial. Arguably a latecomer to prize-giving, EuroSEAS was founded in 1992 to encourage scholarly cooperation within Europe in the field of Southeast Asian studies. The EuroSEAS Humanities Book Prize was set up for the best academic book on Southeast Asia in the humanities—including archeology, art history, history, literature, performing arts, and religious studies—and the EuroSEAS Social Science Book Prize for the best academic book on Southeast Asia published in the social sciences—including anthropology, economics, law, politics and international relations, and sociology.9)

The Bernard Schwartz Book Award is something of an outlier in that it was not awarded by an academic association or collective but rather by the Asia Society, a New York-based organization focused on connecting business, philanthropy, and policy makers with an interest in Asia. For only six years, from 2009 to 2015, this book award—named for a wealthy New York businessman and philanthropist—was given for “nonfiction books that provide outstanding contributions to the understanding of contemporary Asia and/or U.S.-Asia relations . . . [and] designed to advance public awareness of the changes taking place in Asia and the implications for the wider world” (Asia Society Policy Institute 2024). Of the six books awarded the rich US$20,000 prize, two were on Southeast Asia: The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia by James C. Scott (2010 winner) and Tearing Apart the Land: Islam and Legitimacy in Southern Thailand by Duncan McCargo (2009 winner). Unlike the other awards listed above, this prize was judged by a jury made up of experts not exclusively from within academia but also from the media, business, and government.

Patterns of Prestige

We examined the lists of winners of the above book prizes awarded to publications on Southeast Asia in the social sciences and humanities from 2000 to 2022, a total of 42 individual winners. As mentioned, during this period there was a sharp rise in the number of prizes—from only one in 2000 (the Benda Prize) to six in 2009–10—before falling back to five. The prizes are variously awarded annually and biennially. Books in the fields of Indonesian and Vietnamese studies accounted for over half of the prizes examined, and 62 percent of the recipients were men.

Our study was concerned primarily with identifying the institutional affiliations of the prizewinners—for both their PhD study and for most recent employment—and the books’ publishers. Beyond gender, we did not seek to include details related to the identity, nationality, or ethnicity of individual authors because such data, even when available, would need to be qualified by interviews and other quantitative methods.

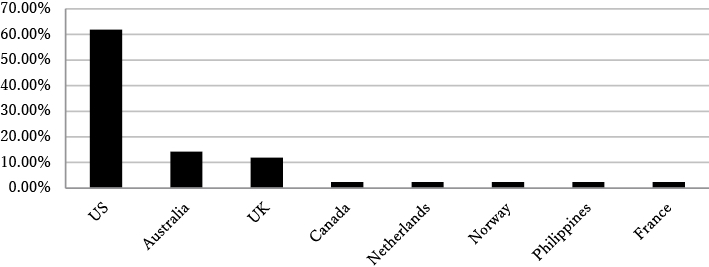

We found that 98 percent of the prizewinners had done their PhD in Europe, Australia, or North America (Fig. 1). The exception was one prizewinner who completed their doctorate in the Philippines.10)

Fig. 1 Location Where Prizewinners Obtained Their PhD

Source: Data collected by Jemma Purdey. Data is for the period 2000–22.

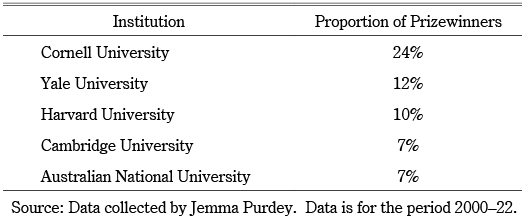

Of these winners, 46 percent had received their doctorate from just three American universities: Cornell, Yale, and Harvard (Table 1).11)

Table 1 Top Institutions from Which Prizewinners Obtained Their PhD

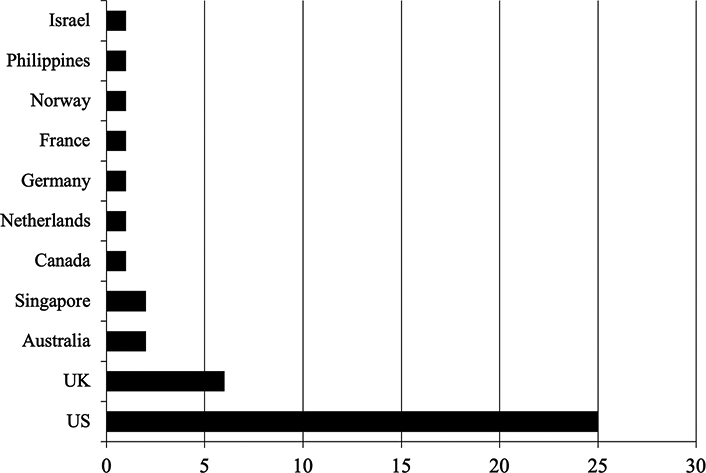

Among those who received one of the book prizes during the period under study, 62 percent at the time of writing are affiliated12) with institutions in North America, 14 percent with institutions in the UK, 5 percent with institutions in Australia, and 7 percent with institutions in the Asian region (two in Singapore and one in the Philippines) (Fig. 2). One is in Israel, and the rest have affiliations in European countries. All recipients appear to have maintained careers in academia and remain active in the field of Southeast Asian studies.

Fig. 2 Prizewinners’ Current Country of Employment

Source: Data collected by Jemma Purdey. Data is for the period 2000–22.

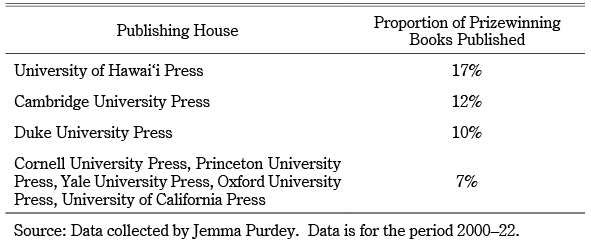

Seventy-nine percent of the awarded books were published by US-based publishers and 14 percent by publishers in the UK (Table 2). The Singapore-based NUS Press accounted for 5 percent (two awarded publications) and the Philippines’ Ateneo de Manila University Press for 2 percent (one publication).

Table 2 Locations of Top Prizewinning Publishing Houses

The two most successful presses—the University of Hawai‘i Press and Cambridge University Press—were also two of the most prolific publishers of work on Southeast Asia during the period under study. Nonetheless, simply having a long publication list of Southeast Asian titles did not equate to success in prize winning. In the period surveyed, Singapore’s ISEAS Publishing and NUS Press had the longest lists of Southeast Asia-related titles, with more than a thousand between them.13) Even taking into account their important position in the region and dedication to Southeast Asian studies, the sheer number is rather remarkable. Nevertheless, from their combined long list of Southeast Asia-related publications, only two books (both co-publications between NUS Press and the University of Hawai‘i Press) received a major book prize between 2000 and 2022. Duke University Press, which ranked third for most prizes awarded, had the best return, publishing one to four Southeast Asia-related books per year (a total of 48 books) and taking home four prizes. Despite the good intention to offer greater opportunity to prizes for which access and judgment had “tended to occur in a rather closed circle of familiarity” (Van der Velde 2020), the old tradition of bestowing prizes and awards to people trained in the Global North and the older centers for Southeast Asian studies has continued. Whilst ICAS and arguably also AAS and EuroSEAS include a diverse and global membership, the organizations are Europe and US based.

Politics, Prizes, and Prestige in Academia

Esteem is one of those rather admirable emotions that provides pleasure to both the giver and the receiver. A recipient of esteem, of course, basks in the admiration of others, but the giver also derives great satisfaction from the sense of having made an apt judgment about another scholar. (Best 2008, 8)

Why study the awarding patterns of book prizes? As Bourdieu (1977), James English (2005), Sarah Bowskill (2022), and others have written, such prizes carry symbolic, cultural, and economic capital, which can translate into prestige, status, career advancement, and advantages in their relevant field. The authors/recipients of such awards are accorded the benefits brought from winning such a prize, but equally, the givers and audiences also benefit: “in this way, awards can dramatize a group’s values, and in the process affirm its solidarity” (Cribb 2005; Best 2008, 8). Book prizes have definitory power in that they define what good science is—what is valued—and who a good scientist is (they manifest a Western understanding of doing research, defining research gaps, applying appropriate methodology, and using appropriate language in science communication). This provides new directions for disciplines and enables them to define their present values as well as future orientation.

Our focus was on prizes open to submissions of English-language books of original work without limitations on place of publication, nationality, or affiliation. This excluded book prizes awarded by the Asian Studies Association of Australia (ASAA), for example, for which only Australians or those affiliated with Australian universities are eligible to apply. The awards under study were all given to single-authored books (although their guidelines do not necessarily exclude multi-authored books). With the exception of the short-lived Bernard Schwartz Book Award, the prizes were awarded by associations of, or for, Asian or Southeast Asian studies. In each case the judging criteria and form of the expert panel were vague, but in general the selection was carried out by a committee of members of the respective association.

All the prizes required nominations to be submitted by the publisher.14) Perhaps this was deemed to be the most expedient process, in that the publishers would need to arrange for review copies and so on and would often have the resources to complete the submission. In reality, as the resources of many publishers shrink, more and more of this sort of work is taken on by the authors themselves. As such, the divide grows ever wider between publishers with the means to participate in the award submission process and those without.15) Without such support, increasingly, the onus is on the authors to, first, be connected into the right networks to know about the prizes; and, second, have the time and resources to submit an application, pursue their publishers to make review copies available, and so on. The nomination processes are in themselves impediments to greater representation from authors who publish outside well-resourced publishing houses on the one hand, and/or do not personally have the time and resources available to undertake the process of submitting their books on the other. Therefore, even as the number of prizes available has increased,16) outside of a few well-funded and well-staffed US and UK university presses, the resources available within publishing houses have declined, with reduced budgets for libraries and research, and digital “disruption” (Mrva-Montoya 2012; Greco 2017; Björnmalm 2018).

The adage “success follows success” most certainly plays a part, as the reputations of well-resourced publishers attract the “best” manuscripts and authors to their imprints, in turn developing a “prestige brand” that can both attract and inhibit certain authors (with thoughts such as “I’m not good enough, so why even try?”). The reality of academic rankings and notions of prestige around particular publishers filters through and influences advice given to early career academics seeking tenure, for example. Largely unwritten, such standards related to reputation and rank impact directly on choices authors make, including not to publish with local regional publishers such as ISEAS or NUS Press but instead to seek out larger US- or Europe-based houses.

When it comes to notions of prestige and excellence in shaping ideas about Southeast Asia, decisions made by US-based university presses and the organizing committees and judging panels responsible for US- and Europe-based book prizes still hold great weight. Whilst not entirely surprising, and recognizing that yawning resource inequalities and strategic imperatives all play a part, the results documented here indicate that the field is possibly further from where Nicholas Farrelly (2018) and others anticipated US-centric influence might be in 2023. The pathways to prestige in the field of Southeast Asian studies remain too narrow and do not reflect the growth in sources of knowledge and the varieties of expertise about Southeast Asia. As Southeast Asian studies centers grow in number across the region and more broadly in Asia, where are their equivalent associations and initiatives establishing prizes like those discussed in this study and thereby establishing their own symbols of prestige?

New Centers for Southeast Asia Knowledge Production

Bearing in mind the patterns of prestige evident in our findings, one may wonder where signs of diversity and vitality to challenge the dominance of US-based scholars and publishers in the field exist or may emerge. For the past twenty years, the field has undergone a significant reflexive exercise to examine its legitimacy. During this time institution-building projects have been launched within the Southeast Asian academy, which was (coincidentally?) coupled with a decline in research and teaching in these areas in the Western academy. Can the de-Westernization of Southeast Asian studies counter the hegemonic knowledge production about Southeast Asia that has so long been under the aegis of Western academic institutions and with it the associated patterns of prestige? What would be the benefits of a “transfer” of such centers of prestige to the region?

Mieno Fumiharu et al. (2021) posit that since such debates about the tensions between regionally based Southeast Asia scholarship and scholarship in the West were initiated in the early to mid-2000s, there appears to have been a noticeable shift: “Southeast Asian studies have become remarkably globalized, through a series of transformations including a significant geographic shift of major research centers from the West to Asia itself.”

Southeast Asian studies has become increasingly globally focused, with a locus of key knowledge production emerging in the region itself, as well as elsewhere in Asia—indicated by the burgeoning of research centers, academic journals, and teaching programs. Cynthia Chou (2017) and others observe that these recent patterns indicate a new self-confidence within Asia more broadly and Southeast Asia in particular. In the past decade, in Singapore, Indonesia, and Malaysia higher education reforms and investment on the back of strengthening economies have shown increased confidence and commitment to the knowledge production sector, with new research centers and journals receiving funding from their governments and other entities.

Since the early 2000s Singapore has led the way, extending its investments in institutions supporting research and publishing, and in the process attracting growing numbers of higher degree research students from the region and beyond (Thompson and Sinha 2019). Singapore’s flagship research institution, the Asia Research Institute at the National University of Singapore, has positioned itself as a leader in the field of Asian studies and research globally. Its director, Tim Bunnell (2023), credited this in part to its location, which provides an “incomparable institutional and geographical home for research on Asia.” Several generations of Southeast Asian scholars have been trained there, and a small number have managed to find ongoing employment in Singapore’s universities.

Malaysian universities have become an attractive choice for both international and local students to enjoy an international (English-language) education at a lower cost. In addition, there are as many as ten foreign university branch campuses in the country (Grapragasem et al. 2014). The Department of Southeast Asian Studies (DSEAS) at the Universiti Malaya was established in 1975 in accordance with one of the objectives of the 1967 ASEAN Declaration—to promote Southeast Asian studies. Other Malaysian universities offer distinguished profiles and expertise in Southeast Asian studies, such as IKMAS at Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, though DSEAS alone offers postgraduate programs.

In Indonesia the internationalization of the higher education sector has been under way since the early 2000s, with numerous government regulations and instructions, including collaboration with foreign universities, international recognition, and validation of academic programs through accreditation and the adoption of international standards in teaching and learning (Bandur 2013). In 2017 the Center for Southeast Asian Social Studies at Universitas Gadjah Mada established IKAT: The Indonesian Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, and it holds a regular series of international seminars and conferences. Universitas Indonesia started a Southeast Asian studies program in response to what it claimed were the needs of society (anyone interested in the diversity of sociocultural and political phenomena in Southeast Asia) and also a growing employment market (diplomats, educators, journalists, practitioners, politicians, diplomats) in which formal education at the master’s level in Southeast Asian studies was sought after.

The rapid expansion of Thailand’s education sector in the 1990s, including institutions of higher learning, saw a prolific “localized Thai response” (Charnvit 2016) in Southeast Asian studies in the 2000s. Centers and programs for undergraduate and postgraduate study were established in numerous universities—Thammasat, Chulalongkorn, and Mahidol, among others. Chulalongkorn University, in particular, hosts centers for research and teaching in Thai studies and Southeast Asian studies more broadly. The Institute for Thai Studies was established in Chulalongkorn University in 2010 as a research center for Thai-Tai studies, emerging from what was previously a government initiative called the Thai Studies Project founded in 1975 (Institute of Thai Studies, n.d.). The institute supports a strong publications program in Thai and English, including a number of journals and book imprints, and has well-established international networks, scholarships, and research activities. Also at Chulalongkorn University, the Thai Studies Center provides postgraduate teaching programs and supports some research activity (Thai Studies Center 2024). Similarly, the university’s Southeast Asian Studies Program, established in 2003, offers an English-language master’s degree in Southeast Asian studies, inviting prospective students to “Understand Southeast Asia from a Southeast Asian Standpoint” (Southeast Asian Studies, n.d.). The three programs and institutions at Chulalongkorn link together to form what appears to be a strong and dynamic research and teaching ecosystem with significant international reach. Outside of the capital city, Walailak University and Payap University also offer Southeast Asian studies programs. While we see important investments being made in regional knowledge production, we agree with Thongchai Winichakul’s findings that higher education and research in Southeast Asia have become hyper-utilitarian and—maybe more frustrating—that most Southeast Asian countries are thriving on education in the natural sciences and communication technology at the expense of social sciences and the humanities (Thongchai 2020, 11). Perhaps this development is characteristic not only of the new but also of some older knowledge production centers.

Elsewhere in Asia, Japan has been a long-term and significant contributor to the production of knowledge on Southeast Asia. The Institute for Southeast Asian Studies was established as an intramural organization at Kyoto University in 1963, as a research department responsible for comprehensive research on Southeast Asia. This was followed by the Center for Southeast Asian Studies (CSEAS), which became a government organization in 1965. The current iteration of CSEAS came about in January 2017 through the merger of various predecessors, and it is currently at the center of global initiatives to revisit and reconsider area studies in order to question, shape, and foster the politics of knowledge production. CSEAS hosts the Secretariat for the Consortium for Southeast Asian Studies in Asia (SEASIA), established in 2013 by area studies institutions in North and Southeast Asia. As of 2023, the consortium included 15 institutions from ten countries.17) SEASIA holds regular conferences, but so far it has not awarded any book prizes. The Asian Law and Society Association, an interdisciplinary association based in Waseda University, is perhaps the only institution based in the region to offer a book prize for Asian studies. It awarded the prize to Southeast Asian studies-related books twice between 2017 and 2023.18) Both books were on Myanmar and published by US university publishers.

More recently, as China has extended its economic and geopolitical engagement with the countries and economies of Southeast Asia through its Belt and Road Initiative, it has looked to expand its knowledge of these societies, polities, and cultures (Saw 2006; Ngeow 2022). In 2016 China’s Ministry of Education issued the Education Action Plan for the Belt and Road Initiative, launching a coordinated effort to follow the lead of its infrastructure and investment program to build university campuses and research and cultural centers in the region (Ngeow 2022). This follows an initiative launched by the ministry in 2011, China’s Regional and Country Studies Bases policy, calling for a nationwide network of area studies centers in China to carry out basic and applied research on foreign regions and subregions (Myers and Barrios 2018). In recent years this has translated into an investment in China’s academy in the study of various regions, including Southeast Asia, with a particular emphasis on language and economics (Van der Eng 2019). As Ngeow Chow-Bing and others point out, China’s ascendency as a knowledge producer and provider within Southeast Asia, though initially faced with “teething problems” (Hoon 2024), is well under way (Ngeow 2022). The ramifications of this geopolitical shift for the production and dissemination of knowledge and the development of networks within the Southeast Asian region are potentially history shaping: “China is now confident to be a teacher, proud of its achievements, and ready to offer its knowledge to the world, especially to the developing world” (Ngeow 2022, 223). So far, however, we have been unable to identify any Southeast Asian studies-related book prizes bestowed by Chinese institutions.

In Korea, in just the past decade several new centers and institutes with a focus on Southeast Asian studies have been established (Ahn and Jeon 2019). The Southeast Asia Center was set up in 2012 at Seoul National University to cater to existing socioeconomic and cultural interest in Southeast Asia within Korea. In late 2018 the Jeonbuk National University Institute for Southeast Asian Studies was launched. Its activities include an annual lecture and paper series, policy reports, and other publications with the aim to “contribute to Korean society by raising awareness of Southeast Asia”; but to date no specific book award for Southeast Asian studies scholars has been established (Jeon 2020).

Chou made the following observation:

The Southeast Asian studies project, which began primarily in the West and has come under severe attack by globalist thinkers in one way or another, has significantly not crumbled under these pressures. Instead, it has forged ahead into an exciting new phase of expanding its spheres of knowledge production. (Chou 2017, 245–246)

Indisputably, the production of knowledge is heavily influenced by hegemonic imbalances, competition privileges, and impermeable patterns of prestige, which—while increasingly challenged by metacriticism of science—still rest on long-lasting mechanisms and self-perpetuating principles of “quality assurance” that determine what good science is and what makes a good scientist (Shahjahan and Morgan 2016). Unlike the old academic core disciplines (such as history and philosophy), which are by default Western-centric and introspective, the newer area studies are directed at understanding the other. Although the outward orientation seems like a specific trait of Southeast Asian studies/area studies, its purpose is nevertheless also self-serving, as the Western gaze has dominated knowledge production through its institutionalized academic hegemony. This hegemony remains visible in the award-giving practices in Southeast Asian studies/area studies. Our findings testify that most books deemed worthy of prizes have been written by scholars trained and based in the Global North and published by Global North publishers.

We are not yet able to answer what the ongoing exclusion of works by Southeast Asia scholars outside the US, the UK, Europe, and Australia in award giving means for progress in the development of Southeast Asian studies in the region itself. Consortia of prominent regional institutions such as SEASIA, working together, may have the potential to generate new momentum in the middle to long term. Nonetheless, current trends show that arbiters of prestige in the field are still based outside the region. In the short term, we wonder whether it might be possible to make changes to the ways in which the book prizes are designed and the eligibility and nomination process managed, which would make for a more inclusive competition.19) As it stands, the nomination processes for the prizes under study advantage resource-rich publishers and individuals. The ASAA’s decision to move away from publisher nomination to peer nomination for the recently inaugurated Reid Prize may potentially widen the field of play by reducing the dependency on resource-rich publishers and authors; and the ASAA prize’s region-based model could be one that others follow.

Following Cribb’s notion of “circles of esteem,” one approach may be for a book prize to emerge from within, governed by scholars based in the region. Indeed, the proliferation of prizes shows that this would not be difficult to implement, but instead the major challenge is how to imbue the prize with the same prestige as existing (Euro-American) prizes. A community of scholars based in the region could choose to ignore existing measures entirely and begin anew, defining their own standards and levels for esteem focused around a gold-standard book prize for Southeast Asian studies by their own definition. Of course, there is every chance that a prize committee based in Bangkok or Singapore might simply replicate existing patterns or definitions of prestige. As described in the origin stories of the existing prizes, their very naming, together with the historical and institutional impetus (and resources) behind the creation of such awards, matter greatly.

Conclusion

It is well acknowledged that the discipline of area studies and subdiscipline of Southeast Asian studies emerged in the wake of World War II, with the geopolitical imperatives of the Cold War in the US, Australia, and elsewhere in the West to “know” the new nation-states emerging in this region. Born from an American hegemonic imperative to understand, inform public policy, and extract from Southeast Asia, knowledge production about “other” cultures, peoples, places, and languages occurred primarily in the Western academy and was conducted by non-Southeast Asians (Said 1978; Cumings 1997; Chou and Houben 2006).The loss of interest in area studies in Western academies since the early 1990s, with the end of the Cold War, has resulted in an institutional decline in the deep study of places, cultures, and languages, including Southeast Asia. This is evident not only in the closure of some institutions and programs but also in reduced funding and scope for research and teaching in Southeast Asian studies in the remaining higher education institutions in the West (Aspinall and Crouch 2023). Unsurprisingly, there is a growing interest in recruiting more secondary and tertiary students from Southeast Asian countries, particularly if they bring in their own funding or scholarships.

Alongside the decline of the discipline in some parts of the world and an emergence of interest in other parts, scholars and researchers within Southeast Asian studies have debated epistemologies and reflected deeply on their field (Sutherland 2012; Mielke and Hornidge 2017; Fleschenberg and Baumann 2020). A focus on the underlying power imbalances or the positionalities of those who thrive in the discipline is also not new (Feith 1965; Reid 1999; Kratoska et al. 2005; Asif 2020).20) Bonura and Sears (2007, 17) and others proposed linkages between new and old Southeast Asian studies hubs as potential antidotes to the presumption that Southeast Asian studies remained largely a “unidirectional project in which academies in Europe, the US, Australia or Japan remain distant from the methods, scholarship and academic trends or politics emerging out of Southeast Asia.” While many strategic temporary and ongoing partnerships, exchanges, and collaborations have been established—including Western universities setting up campuses in the Southeast Asian region with, it must be said, varying levels of success—it remains to be seen whether they can contribute to overcoming the deeply embedded power imbalances in knowledge production and knowledge appreciation (Missbach 2011).

Though such discussions are beyond the scope of this article, we are keenly aware that many questions remain about the mid- to long-term geostrategic relevance and implications of emerging hubs of knowledge production elsewhere in Asia and beyond. What is driving this invigoration within Southeast Asian studies in the region and emerging centers? And will Southeast Asian studies in these new centers ever catch up with, let alone overtake, the declining centers of Southeast Asia knowledge production in the West? Why do top-tier Southeast Asia scholars continue to select US, UK, and Australian institutions for pursuing their advanced degrees? As Manan Ahmed Asif has pointed out, it is imperative to derive such insights from these scholars themselves:

What the post-colonised scholar asks are the resources for being a scholar, for accessing the archives in Europe and the United States, for accessing the social capital of European and US-American universities, for availing themselves of the distribution circuits of printing presses of the world, newspapers of the world, conferences of the world. The post-colonised scholar wishes for the security for their body in order for their minds to be able to question their own local, their own history as constructed and as imagined. (Asif 2020, 77)

As Asif argues, why should scholars from the region not continue to be trained in well-resourced “traditional” centers in the Global North and West? At the same time, what do we know about the emerging generation that is being trained locally in Southeast Asia or elsewhere in emerging centers? What are the connections and bridges being forged between them?

Where and how Southeast Asia knowledge is being created, disseminated, consumed, and prized today, and where it is likely to be created and lauded in the future, depend largely on the institutional, societal-structural, and national interests and biases that exist within the process of knowledge production. Whilst book prizes represent only a part of the economy of prestige within Southeast Asian studies, our survey shows that the work deemed most valuable is a product of expert training emanating from the West and feeds directly back into its institutional structures. So far, the flows of scholars (including the “new” generation from Southeast Asia) are indeed unidirectional (into and within the West), and there is nothing to indicate this will change any time soon.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Robert Cribb and Joanna Pfaff-Czarnecka as well as the two anonymous reviewers of this paper for their constructive feedback.

References

Acharya, Amitav and Buzan, Barry. 2017. Why Is There No Non-Western International Relations Theory? Ten Years On. International Relations of the Asia Pacific 17(3): 341–370. https://doi.org/10.1093/irap/lcx006.↩

Ahn Chung-si and Jeon Je Seong, eds. 2019. Southeast Asian Studies in Korea: The History, Trends and Analysis. Seoul: Seoul National University Press.↩

Antweiler, Christoph. 2017. Area Studies @ Southeast Asia: Alternative Areas vs. Alternatives to Areas. In Area Studies at the Crossroads: Knowledge Production After the Mobility Turn, edited by Katja Mielke and Anna-Katharina Hornidge, pp. 65–81. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.↩

Appadurai, Arjun. 2000. Grassroots Globalization and the Research Imagination. Public Culture 12(1): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-12-1-1.↩ ↩ ↩

Arnado, Janet M. 2021. Structured Inequalities and Authors’ Positionalities in Academic Publishing: The Case of Philippine International Migration Scholarship. Current Sociology 71(3): 356–378. https://doi.org/10.1177/00113921211034900.↩

Asia Society Policy Institute. 2024. Bernard Schwartz Book Award. Asia Society Policy Institute. https://asiasociety.org/policy-institute/bernard-schwartz-book-award, accessed June 22, 2024.↩

Asian Law and Society Association. 2023. Awards & Competitions. Asian Law and Society Association. https://www.alsa.network/awards-competitions, accessed June 22, 2024.↩

Asif, Manan Ahmed. 2020. The Newness of Area Studies. International Quarterly for Asian Studies 51(3–4): 75–77.↩ ↩

Aspinall, Edward and Crouch, Melissa. 2023. Australia’s Asia Education Imperative: Trends in the Study of Asia and Pathways for the Future. Canberra: Asian Studies Association of Australia.↩

Association for Asian Studies. 2019a. George McT. Kahin Prize. Association for Asian Studies. https://www.asianstudies.org/grants-awards/book-prizes/kahin-prize/, accessed June 22, 2024.↩ ↩

―. 2019b. Harry J. Benda Prize. Association for Asian Studies. https://www.asianstudies.org/grants-awards/book-prizes/benda-prize/, accessed June 22, 2024.↩

Bandur, A. 2013. Internationalization of Indonesian State Universities: Current Trends and Future Challenges. Conference Proceedings, Opportunities and Challenges for Higher Education Institutions in the ASEAN Community, pp. 22–27.↩

Best, Joel. 2008. Prize Proliferation. Sociological Forum 23(1): 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1573-7861.2007.00056.x.↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

Björnmalm, Mattias. 2018. The Future for Academic Publishers Lies in Navigating Research, Not Distributing It. LSE Blog. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2018/01/29/the-future-for-academic-publishers-lies-in-navigating-research-not-distributing-it/, accessed July 24, 2023.↩

Bonura, Carlo and Sears, Laurie J. 2007. Introduction: Knowledges that Travel in Southeast Asian Area Studies. In Knowing Southeast Asian Subjects, edited by Laurie J. Sears, pp. 3–32. Seattle: University of Washington Press.↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1977. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.↩ ↩

Bowskill, Sarah E. L. 2022. The Politics of Literary Prestige: Prizes and Spanish American Literature. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.↩

Bunnell, Tim. 2023. Message from the Director. Asia Research Institute. https://ari.nus.edu.sg/management/message-from-the-director/, accessed June 24, 2024.↩

Burman, Anders. 2018. Are Anthropologists Monsters? An Andean Dystopian Critique of Extractivist Ethnography and Anglophone-Centric Anthropology. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 8(1–2): 48–64. https://doi.org/10.1086/698413.↩ ↩

Charnvit Kasetsiri. 2016. Southeast Asian Studies in Thailand. CSEAS Newsletter. http://www-archive.cseas.kyoto-u.ac.jp/www/2016/2014/03/southeast-asian-studies-in-thailand/, accessed July 21, 2023.↩

Chou, Cynthia. 2017. The Case for Reconceptualizing Southeast Asian Studies. In Area Studies at the Crossroads: Knowledge Production After the Mobility Turn, edited by Katja Mielke and Anna-Katharina Hornidge, pp. 233–249. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.↩ ↩ ↩

Chou, Cynthia and Houben, Vincent, eds. 2006. Southeast Asian Studies: Debates and New Directions. Singapore: ISEAS.↩

Chua Beng Huat; Dean, Ken; Ho Engseng et al. 2019. Area Studies and the Crisis of Legitimacy: A View from South East Asia. South East Asia Research 27(1): 31–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/0967828X.2019.1587931.↩

Consortium for Southeast Asian Studies in Asia. 2023. Institutions. Consortium for Southeast Studies in Asia. https://seasia-consortium.org/institutions/, accessed June 22, 2024.↩

Cribb, Robert. 2005. Circles of Esteem, Standard Works, and Euphoric Couplets. Critical Asian Studies 37(2): 289–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/14672710500106408.↩ ↩ ↩

Cumings, Bruce. 1997. Boundary Displacement: Area Studies and International Studies During and After the Cold War. Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars 29(1): 6–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/14672715.1997.10409695.↩

Derichs, Claudia. 2017. Knowledge Production, Area Studies and Global Cooperation. New York: Routledge.↩

English, James F. 2005. The Economy of Prestige. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.↩ ↩

Farrelly, Nicholas. 2018. Notes on the Future of Southeast Asian Studies. In Southeast Asian Affairs, edited by Malcolm Cook and Daljit Singh, pp. 3–18. Singapore: ISEAS Publishing.↩ ↩

Feith, Herbert. 1965. History, Theory, and Indonesian Politics: A Reply to Harry J. Benda. Journal of Asian Studies 24(2) (February): 305–312. https://doi.org/10.2307/2050572.↩

Fleschenberg, Andrea and Baumann, Benjamin. 2020. New Area Studies and Southeast Asia: Mapping Ideas, Agendas, Debates and Critique. International Quarterly for Asian Studies 51(3–4): 5–16.↩ ↩

Grapragasem, Selvaraj; Krishnan, Anbalagan; and Mansor, Azlin Norhaini. 2014. Current Trends in Malaysian Higher Education and the Effect on Education Policy and Practice. International Journal of Higher Education 3(1): 85–93.↩

Greco, Albert N., ed. 2017. The State of Scholarly Publishing: Challenges and Opportunities. Milton: Routledge.↩

Heryanto, Ariel. 2002. Can There Be Southeast Asians in Southeast Asian Studies? Moussons 5: 3–30. https://doi.org/10.4000/moussons.2658.↩

Hoon Chang-Yau. 2024. Strengthening Southeast Asian Studies in China. Fulcrum: Analysis on Southeast Asia. June 28. https://fulcrum.sg/strengthening-southeast-asian-studies-in-china/, accessed July 29, 2024.↩

Institute of Thai Studies. n.d. Thai Studies Wisdom for Thai and Global Communities. Institute of Thai Studies, Chulalongkorn University. http://www.thaistudies.chula.ac.th, accessed June 26, 2024.↩

International Convention of Asia Scholars. n.d.a. ICAS Book Prize. International Convention of Asia Scholars. https://icas.asia/icas-book-prize, accessed June 22, 2024.↩

―. n.d.b. Previous IBP Editions. International Convention of Asia Scholars. https://www.icas.asia/previous-ibp, accessed June 22, 2024.↩ ↩

Jackson, Peter A. 2019. South East Asian Area Studies beyond Anglo-America: Geopolitical Transitions, the Neoliberal Academy and Spatialized Regimes of Knowledge. South East Asia Research 27(1): 49–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/0967828X.2019.1587930.↩ ↩

Jeon Je Seong. 2020. Director’s Message: JISEAS, Openness and Solidarity. JISEAS. https://jiseaseng.jbnu.ac.kr/jiseaseng/15828/subview.do, accessed July 29, 2024.↩

Kratoska, Paul H.; Raben, Remco; and Schulte Nordholt, Henk, eds. 2005. Locating Southeast Asia: Geographies of Knowledge and Politics of Space. Singapore: Singapore University Press.↩

Lev, Daniel S. 2007. George McT Kahin (1918–2000). Inside Indonesia 62 (April–June). https://www.insideindonesia.org/george-mct-kahin-1918-2000, accessed April 14, 2023.↩

McVey, Ruth. 1995. Change and Continuity in Southeast Asian Studies. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 26(1): 1–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/s0022463400010432.↩

Melber, Henning. 2018. Knowledge Production and Decolonisation: Not Only African Challenges. Strategic Review for Southern Africa 40(1): 4–15.↩

Mielke, Katja and Hornidge, Anna-Katharina, eds. 2017. Area Studies at the Crossroads: Knowledge Production after the Mobility Turn. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.↩ ↩

Mieno Fumiharu; Bi Shihong; Nualnoi Treerat; Didi Kwartanada; and Feener, R. Michael. 2021. Southeast Asian Studies in Asia: Recent Trends. Asian Studies 67(1): 18–34. https://doi.org/10.11479/asianstudies.67.1_18.↩ ↩

Mignolo, Walter D. 2002. The Geopolitics of Knowledge and the Colonial Difference. South Atlantic Quarterly 101(1): 57–96.↩

Missbach, Antje. 2011. Ransacking the Field? Collaboration and Competition between Local and Foreign Researchers in Aceh. Critical Asian Studies 43(3): 373–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/14672715.2011.597334.↩

Mrva-Montoya, Agata. 2012. Academic Publishing Must Go Digital to Survive. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/academic-publishing-must-go-digital-to-survive-5286, accessed July 23, 2023.↩

Myers, Margaret and Barrios, Ricardo. 2018. In Pursuit of Global Know-how: China’s New Area Studies Policy. Diplomat. August 3. https://thediplomat.com/2018/08/in-pursuit-of-global-know-how-chinas-new-area-studies-policy/, accessed April 14, 2023.↩

Ngeow Chow-Bing. 2022. China’s Universities Go to Southeast Asia: Transnational Knowledge Transfer, Soft Power, Sharp Power. China Review 22(1): 221–248. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48653985, accessed June 24, 2024.↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

Purdey, Jemma, ed. 2012. Knowing Indonesia: Intersections of Self, Discipline and Nation. Clayton: Monash University Publishing.↩

―. 2011. From Vienna to Yogyakarta: The Life of Herb Feith. Sydney: UNSW Press.↩ ↩

Reid, Anthony. 2009. Indonesian Studies at the Australian National University: Why so Late? RIMA: Review of Indonesian and Malaysian Affairs 43(1): 51–74. https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/items/4923ef32-4aa1-49c7-9125-f11d184bc9df, accessed June 24, 2024.↩

―. 1999. Studying “Asia” in Asia. Asian Studies Review 23(2): 141–151.↩

Said, Edward W. 1978. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books.↩

Saw Swee-Hock. 2006. A Review of Southeast Asian Studies in China. In Southeast Asian Studies in China, edited by Saw Swee-Hock and John Wong, pp. 1–7. Singapore: ISEAS Publishing.↩

Schöpf, Caroline. 2020. The Coloniality of Global Knowledge Production: Theorizing the Mechanisms of Academic Dependency. Social Transformations: Journal of the Global South 8(2): 5–46.↩

Shahjahan, Riyad A. and Morgan, Clara. 2016. Global Competition, Coloniality, and the Geopolitics of Knowledge in Higher Education. British Journal of Sociology of Education 37(1): 92–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2015.1095635.↩ ↩

Southeast Asian Studies. n.d. Understand Southeast Asia from a Southeast Asian Standpoint. Southeast Asian Studies Program, Chulalongkorn University. https://seachula.com/, accessed June 22, 2024.↩

Sutherland, Heather. 2012. Finding a Middle Way: The Future of Indonesian Studies in the Western Academy. In Knowing Indonesia: Intersections of Self, Discipline and Nation, edited by Jemma Purdey, pp. 97–121. Clayton: Monash University Publishing.↩

Thai Studies Center. 2024. Welcome to Thai Studies Center. Thai Studies Center, Faculty of Arts, Chulalongkorn University. https://www.arts.chula.ac.th/international/thai/, accessed June 22, 2024.↩

Thompson, Eric C. and Sinha, Vineeta, eds. 2019. Southeast Asian Anthropologies: National Traditions and Transnational Practice. Singapore: NUS Press.↩

Thongchai Winichakul. 2020. Southeast Asian Studies in Asia in the Age of Disruption. Southeast Asia: History and Culture 49: 11–25. https://doi.org/10.5512/sea.2020.49_11.↩

―. 2014. Asian Studies across Academies. Journal of Asian Studies 73(4): 879–897. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43553457, accessed June 24, 2024.↩ ↩ ↩

Van der Eng, Pierre. 2019. Academic Interest in Indonesia’s Economy Accelerates in China. Asian Currents. February 11. https://asaa.asn.au/academic-interest-indonesias-economy-accelerates-china/, accessed April 14, 2023.↩

Van der Velde, Paul. 2020. The ICAS Book Prize: A Multilingual Window on the World of Asian Studies. IIAS Newsletter 86 (Summer). https://www.iias.asia/the-newsletter/article/icas-book-prize-multilingual-window-world-asian-studies, accessed June 26, 2024.↩ ↩

Vickers, Paul. 2020. Review of Katja Mielke and Anna-Katharina Hornidge, Area Studies at the Crossroads: Knowledge Production After the Mobility Turn. Connections: A Journal for Historians and Area Specialists. May 16. https://www.connections.clio-online.net/publicationreview/id/reb-28417, accessed June 24, 2024.↩

Wertheim, Willem F. 1972. Harry J. Benda (1919–1971). Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 128(2/3): 214–218.↩

1) “Based in” refers to scholars who appeared to be resident (living and working) in these countries at the time we conducted the research. We did not seek to establish their citizenship status, which may have consisted of more than one citizenship.

2) We plan to conduct future studies tracing the career trajectories of book prize awardees in order to measure the impact of the accolades on their academic life, using whole-of-life interviews and associated quantitative methodologies.

3) See the discussion on the relationship between Southeast Asian studies and university presses below.

4) Consequently, book prizes awarded by the Asian Studies Association of Australia, for example, were not included as these are limited to applications from residents and students enrolled in Australian institutions.

5) As will be detailed later, our survey indicates that over the 22 years under investigation, 42 books were awarded prizes matching our criteria (sole-authored, original, open). The small sample size is indicative of the relative scarcity and therefore enhanced prestige attached to these prizes, on the one hand, and the relatively marginal state of the field within the academy on the other.

6) Using open-access sources we compiled data for book publications on Southeast Asian studies topics from 15 leading academic publishers. Together they published a total of over two thousand books between 2000 and 2022.

7) An amount of 2,500 euros is awarded to each major prize winner—half of which is cash and half of which is given as a travel grant to attend the next ICAS conference.

8) In 2022 a prize of US$1,000 was awarded to the winner.

9) In 2022 the prizewinners were each awarded 750 euros.

10) Sixty-two percent of the awarded authors completed their PhD in the US, 14 percent in Australia, and 12 percent in the UK. The remaining 12 percent obtained their PhD from other European universities, one Canadian university, and one university in the Philippines.

11) Universities that house centers for Southeast Asian studies (such as Yale University, Cornell University, and University of Hawai‘i) also have publishers with imprints with Southeast Asia series. Logically, this creates an ecosystem in which these publishers have more editors with expertise in Southeast Asia, which in turn means greater support for books in this field of study, including those written by authors with affiliations to Southeast Asian studies.

12) In most cases this means staff in a university institution. In some cases, it may be an adjunct or similar; however, it is their primary institutional affiliation. Data were compiled from open-access online sources, including public university websites, LinkedIn, and personal websites and blogs.

13) Based on data publicly available on the publishers’ websites. Note that there are many other publishers of Southeast Asian studies in the region, but we have chosen to focus on these two based on their significant output and potential influence.

14) It is beyond the scope of this article to consider the “gatekeeping” role of large university presses in their manuscript selection process. Suffice it to say that due to resource limitations, this often involves a tiered sorting process, with several hurdles before a manuscript is likely to be considered. The entry point for many is by way of introduction from a contact such as a supervisor or colleague who has previously worked with a publisher or editor of a book series, for example. Another hurdle is the submission of work that is of a very high standard of English and the Anglophone-centrism more generally (Burman 2018, 50).

15) See note 11 regarding universities in the US with the resources (human and financial) to support Southeast Asian imprints in their university presses (notably, Cornell, Hawai‘i, and Duke).

16) As publishers (particularly smaller ones) have less and less resources to market books and provide alternative promotional pathways for authors, for academic communities (associations and so on) prize giving is one way of drawing attention to certain works. This may also help to explain the proliferation of awards during the period under study.

17) The countries with member institutions are China (and Hong Kong), Taiwan, the Philippines, Brunei, Cambodia, Thailand, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, and Singapore (Consortium for Southeast Asian Studies in Asia 2023).

18) The prize consists of US$300 cash and ALSA membership (Asian Law and Society Association 2023).

19) Initiatives by organizations like AAS and others in the Western academy provide funding and scholarships to emerging scholars working on Southeast Asia and from the region. If sustained over a long period of time and, crucially, extended to those who are both from and in the region, such initiatives may contribute to shifting the balance to the region.

20) Others include Purdey (2012), Acharya and Buzan (2017), Antweiler (2017), Chou (2017), Derichs (2017), Mielke and Hornidge (2017), Chua et al. (2019), and Jackson (2019). The reflection on positionalities occurred largely within and among scholars in countries outside Asia, in what has historically been referred to as the “West”—US, UK, Europe, and Australia and New Zealand—or between this cohort and a small number of scholars from the countries under study (Vickers 2020; Mieno et al. 2021).