Advance Publication

Accepted: April 9, 2024

Published online: July 3, 2025

Contents>> Vol. 14, No. 2

“Karampátan ñg Tao”: Tracing the Rise of Tagalog Human Rights Discourse Using a Textual Corpus

Ramon Guillermo*

*Center for International Studies, University of the Philippines Diliman, Benton Hall, M. Roxas Avenue, U.P. Campus, University of the Philippines, 1101 Quezon City, Metro Manila, Philippines

e-mail: rgguillermo[at]up.edu.ph

![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1524-5807

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1524-5807

DOI: 10.20495/seas.25002

Browse “Advance online publication” version

This essay is a preliminary study on the rise of human rights discourse in the Tagalog language from the late nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth using a carefully designed textual corpus. The corpus is made up of original Tagalog texts as well as translations of political treatises from European languages into Tagalog. While it has been found that karapatan (rights) is indeed a central notion in the development of a specifically Tagalog revolutionary discourse, the matter of its “inherence” in the tao (human being) has followed a particularly convoluted path due to the existence of alternative interpretations revolving around the moral “worthiness” of individuals and classes.

Keywords: human rights, Tagalog, political lexicography, text corpora

Introduction

This essay aims to trace the historical process of development of the phrase “karapatang pantao,” the modern Tagalog equivalent for “human rights,” from the late nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth. It attempts to do this by using a carefully designed textual corpus. There are many difficulties with such an endeavor. Most pertinent is how to avoid arbitrariness and the charge of impressionism in the construction of such a corpus.

On the one hand, the most important type of textual source for Reinhart Koselleck’s (1972, xxiv) massive multivolume project Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe: Historisches Lexikon zur politisch-sozialen Sprache in Deutschland (Historical basic concepts: A historical lexicon of political-social language in Germany) (1972–97) falls under the category of “classical” writers and works. The tendency to refer to the use of “classical writers and works” as main references can be seen in the article “Recht, Gerechtigkeit” (Right/law, justice), which comprehensively discusses the contributions of Hugo Grotius, Jean Bodin, Thomas Hobbes, Samuel von Pufendorf, John Locke, Christian Thomasius, Christian Wolff, Montesquieu, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau in tracing the development of the modern German concept of rights (Loos and Schreiber 1982). On the other hand, Rolf Reichardt and Eberhard Schmitt’s (1985, 46) equally important Handbuch politisch-sozialer Grundbegriffe in Frankreich 1680–1820 (Handbook of basic sociopolitical concepts in France 1680–1820) branded Koselleck’s approach as a problematic Gipfelwanderungen, or jumping from one mountain peak to another. This latter project, therefore, tried as much as possible to avoid the so-called classics and made far greater use of all types of dictionaries, encyclopedias, memoirs, magazines, newspapers, pamphlets, flyers, minutes of meetings, catechisms, almanacs, songs, etc. (cf. Schmale 2000). The aim of the Handbuch, in contrast with Koselleck’s Lexikon, was to more closely reflect daily political usages and arrive at greater social representativeness. The Handbuch thus had to move away from intellectual history toward something approximating a history of mentalities in France. In relation to this, the increasing use of automated word search, frequency lists, and collocational analysis on massive amounts of digitized textual materials has revolutionized the possible scope and rigor of this type of conceptual history in recent years.

Pursuing similar undertakings in the Philippine context is complicated by several limitations. First, Koselleck’s approach presupposes a corpus of generally uncontested classic works by universally recognized authors on law and politics throughout the centuries, which does not exist in the Tagalog language. Any proposed selection of Tagalog texts would not appear self-evident in the way that the inclusion of the writings of Hobbes and Locke in a history of European political thought would be. Second, large comprehensive digital corpora comparable with Gallica of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (with ten million texts) and the Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek (with fifty million digital objects), which would facilitate implementing a project similar to Reichardt and Schmitt’s Handbuch, do not yet exist for Tagalog or for any Philippine language. The future availability of well-designed large textual corpora will minimize questions regarding arbitrariness in the selection of materials.

Since massively large corpora are not yet available for the historical study of Tagalog political discourse (as well as those of other Philippine languages), a quality corpus of selected texts may serve to give some preliminary insights on this important topic without foreclosing any possible future discoveries or refutations of findings based on more complete datasets. The proposed quality corpus includes selected Tagalog dictionaries from 1613 to 1978, original political treatises in Tagalog from 1889 to 1941, as well as translations from various European languages into Tagalog from 1593 to 1913. The present corpus has therefore been constructed which includes the following materials:

1) An early Tagalog translation: Doctrina Christiana, en lengua española y tagala (Christian doctrine in Spanish and Tagalog languages) (translated 1593);

2) Original Tagalog works from the late nineteenth century Philippine Revolution: Jose Rizal’s “Liham sa mga Kadalagahan sa Malolos” (Letter to the young women of Malolos) (1889); Emilio Jacinto’s “Kartilya” (primer) of the Kataastasaang Kagalang-galang na Katipunan ng mga Anak ng Bayan (The Highest and Most Revered Association of the Sons and Daughters of the People; KKK) (1892); documents of the KKK (1896–97) (Richardson 2013); Jacinto’s “Liwanag at Dilim” (Light and darkness) (1896);

3) Translations into Tagalog from the late nineteenth century Philippine Revolution: Déclaration des droits de l’homme et du citoyen, 1789 (Declaration of the rights of man and the citizen, 1789) (1949) (translated c. 1891–92); Friedrich Schiller’s Wilhelm Tell (translated 1886–87); Apolinario Mabini’s Programa Constitucional de la República Filipina (Constitutional program of the Philippine Republic) (self-translated in 1898);

4) Original Tagalog works from the Philippine labor movement: Lope K. Santos’s socialist novel Banaag at Sikat (Glimmer and ray) ([1906] 1993); Carlos Ronquillo’s Bagong Buhay: Ang mga Katutubong karapatan ng mga Manggagawa sa Harap ng Wagas na Matwid (New life [socialism]: The inherent rights of the worker in the light of pure reason) (1910); Cirilo S. Honorio’s Tagumpay ng Manggagawa: May Kalakip na Sampung Utos, Pitong Wika, Tula at Tuluyang Ukol sa Manggagawa na Sinulat ng mga Tanyag na Manunulat (Workers’ victory: Including ten commandments, seven discourses, poems, and prose about workers written by well-known writers) (1925); Crisanto Evangelista’s pamphlet Patnubay sa Kalayaan at Kapayapaan (Guide to freedom and peace) (1941);

5) Translations into Tagalog from the Philippine labor movement: Plataforma y Constitución del Gremio de Impresores, Litografos y Encuadernadores (Platform and constitution of the Guild of Printers, Lithographers, and Binders) (translated 1904); Errico Malatesta’s Fra contadini: dialogo sull’anarchia (Among peasants: A dialogue on anarchy) (translated 1913).

It is a truism that the construction of a bounded or restricted textual corpus must inevitably give rise to certain conceptions regarding the history of a particular language. The most important thing, therefore, is to ensure the transparency of the principles behind the construction of the corpus itself. In this particular case, and in contrast with Kosellek’s Lexikon and Reichardt and Schmitt’s Handbuch, translations of texts from the late nineteenth century onward associated with the Philippine Revolution of 1896 and the rise of the Philippine labor movement play an especially significant role insofar as these are able to show traces of the historically and linguistically conditioned constraints and possibilities in the dissemination of ideas originating from Europe. Many of the works included in the present corpus are quite rare, obscure, and little read by today’s scholars. Despite the limitations of this bounded corpus, transparency with respect to its construction, in terms of both its inclusions and omissions, can allow for a more precise and constructive discussion of the established textual facts and their possible interpretation and organization. What is given importance here is the dialectic between creativity and constraint posed by language as an intersubjective reality on both the synchronic and diachronic planes.

The present author has been involved in several small and medium-scale efforts in the digitization of Philippine materials and has focused his personal efforts on digitizing textual materials from the first decades of the Philippine labor movement to the rise of the Partido Komunista ng Pilipinas (Communist Party of the Philippines; PKP). In fact, his early work was devoted to the exploration of these materials (Guillermo 2009b). He is well aware that many more texts which have already been digitized could be included in the present corpus to give further nuance to the thesis he is presenting. However, due to space constraints, most of these materials had to be left out of consideration. These can be the subject of future studies.

The present approach might be called a certain kind of linguistic empiricism due to its close attention to the recording and interpretation of concrete textual phenomena in definite collocational contexts (Sy 2022). Moreover, by methodologically eschewing tendencies toward any strong “etymologism,” the current approach diverges from the otherwise useful contributions in this field by Zeus Salazar (1999; Guillermo 2009a). The contrast between Salazar’s strong etymologism in the study of Philippine political vocabularies and a more empiricist approach to the same phenomena can be summarized as follows: where Salazar inextricably ties what he seemingly considers to be the true and unchanging semantic content of a word to its (purported) root, the second approach tries to draw out meanings from actual and verifiable usages of the relevant words as these appear through time. Unreflected hermeneutic predilections and strategies may also be made more visible when these come into conflict with textual facts. This study therefore tends toward the politico-lexicographic and is partly intended as an aid in advancing the more speculative and thematic approaches in intellectual history such as those previously embarked upon by Cesar Adib Majul (1996), Rolando Gripaldo (2001), and Johaina Crisostomo (2021). Indeed, these previous studies have, for the most part, dealt only very lightly with the problems of language and translation.

Why is it important to study the historical development of modern political discourse in Tagalog and other Philippine languages? For the most part, scholars interested in Philippine politics, with the exception of some brilliant scholars such as Benedict Kerkvliet (1990) and the Japanese political anthropologist Kusaka Wataru (2017), have shown little interest in how the masses, the rural and urban poor, and the working classes have actively discussed what counts as politics among themselves in the languages available to them (Ileto 2001). However, this kind of work is, on the one hand, becoming more and more indispensable even in mainstream scholarship due to the increasingly stiff competition faced by the complacently English-speaking liberal political establishment from non-traditional populist contenders from other factions of the Philippine ruling elite. This study contributes to scholarship on the languages of politics in the Philippines even as it has been inspired by Benedict Anderson’s (1990) similar work on Indonesia. On the other hand, such studies have always been crucial from the point of view of progressive and transformative Philippine politics, which is premised on the active participation and self-mobilization of the masses in the remaking of Philippine society (Guillermo et al. 2022).

The French Déclaration des droits de l’homme et du citoyen, 1789 in Tagalog Translation: “Les droits naturels et imprescriptibles” (Natural and Imprescriptible Rights)

The Tagalog translation of the French Déclaration des droits de l’homme et du citoyen, 1789, which was supposedly written by Jose Rizal (1861–96) (c. 1891–92; 1961a), the novelist and Philippine national hero, during his stay in Hong Kong is an early example of the development of the uneasy Tagalog reception of the European discourse on “rights.” The Tagalog translation is accompanied in its original printed form by a Spanish translation which it very closely mirrors. It is not clear whether the Tagalog translation was based on the Spanish text or vice versa. There is no source indicated for the Spanish text, and it is plainly quite different from the “Declaración de los derechos del hombre y del ciudadano, 1793” (Declaration of the rights of man and of the citizen, 1793), the canonical 1793 translation by Antonio Nariño (1981). Moreover, the Tagalog translation and the Spanish version accompanying it are both substantially abridged versions of the original Déclaration. The preamble of the Déclaration is omitted from the translation. One suspects that the accompanying Spanish translation was partially meant to lend a somewhat spurious authority to the accuracy and completeness of the Tagalog translation.

In the original French text with 17 articles, including the title, droit(s) is mentioned a total of 11 times. Seven instances of these are translated consistently using karampatan, while the other four occurrences are simply elided in both the Tagalog and accompanying Spanish translations. Though it does not seem self-evident, some dictionaries (Almario 2010) claim that karampatan shares the same root (dapat, ought) as karapatan, but one can also speculate on a possible derivation from katampatan (deserving/meritorious) instead. Karampatan would, however, eventually lose out to karapatan as the standard translation for “right.”

Article I of the Déclaration contains the famous sentence “Les hommes naissent et demeurent libres et égaux en droits” (Men are born and remain free and equal in rights). This is translated into Tagalog as “Ang tao’y malayang ipinaganak; nananatiling malayá at sa karampata’y paris-paris” (The human being is born free; remains free and equal in rights). The first thing one observes is that the Tagalog translation conveys the idea that a tao (human being), once born into the world, is free and equal to others in terms of rights. This is very close to the sixth Sabi (saying) in Rizal’s (1961b) essay “Sa mga kababayang dalaga ng Malolos” (To the young women of Malolos) (1889): “Ang tao’y inianak na paris-paris hubad at walang tali” (Each human being is born equal [paris-paris], naked, and without fetters). This is reminiscent of Rousseau’s phrasing in Du Contrat Social (The social contract) (1762), “L’homme est né libre, & partout il est dans les fers” (Man is born free and everywhere he is in chains)—but also quite different. Where Rizal writes of being born paris-paris (equal), Rousseau writes libre (free); where Rizal writes “walang tali” (without any fetters), Rousseau writes “dans les fers” (in chains). One notes that the Tagalog translation as well as Rizal’s essay did not yet make use of the word pantay-pantay (even, equal), which is more commonly used in contemporary Filipino for “equal,” but instead used paris-paris (coming in pairs, or identical).

The Tagalog translation (like the accompanying Spanish translation) does not include the first sentence of Article II of the French original, which is as follows: “Le but de toute association politique est la conservation des droits naturels et imprescriptibles de l’Homme” (The goal of all political association is the conservation of the natural and inalienable rights of man). The important phrase “droits naturels et imprescriptibles” (natural and imprescriptible rights) is therefore left untranslated. While the range of meaning of the French imprescriptible may include “inalienable” in its English sense, the word inaliénable itself occurs in the Déclaration in the phrase “les droits naturels, inaliénables et sacrés de l’Homme” (the natural, inalienable, and sacred rights of man), which appears in the untranslated preamble. The legal meaning of imprescriptible as “not being subject to any limitation or abridgement” is quite different from inaliénable, which means “non-transferable” or “cannot be taken away.”

The succeeding sentence in Article II, which contains an enumeration of basic rights, however, is maintained (“la liberté, la propriété, la sûreté, et la résistance à l’oppression” [liberty, property, security, and the resistance to oppression]). Quite important among these, especially for the purposes of the Tagalog translation, is the assertion of the right to “la résistance à l’oppression” (resistance to oppression), which is translated as “pagsuay sa umaapi” (to disobey/revolt against the oppressor). Another occurrence of “droits naturels” (natural rights) in Article IV is left untranslated (“l’exercice des droits naturels de chaque homme” [the exercise of natural rights by each person/man]). A stand-alone occurrence of droit in Article V is again left untranslated (“le droit de défendre” [the right to forbid]).

The right to free expression, characterized in Article XI as “un des droits les plus précieux de l’Homme” (one of the most precious rights of man), is translated straightforwardly as “isa sa mga mahalagang karampátan ñg tao” (one of the most important rights of the human being). On the other hand, the phrase “droits de l’Homme et du Citoyen” (rights of man and of the citizen) is truncated in the Tagalog translation as “karampátan ñg tao” (right of the human being), which drops the mention of “citizen.” This latter word was difficult to translate since it did not yet have a fixed equivalent in the Tagalog language at the time. A stand-alone mention of droits in Article XVI is unproblematically translated as karampatan (“la garantie des Droits” [guarantee the rights]). Finally, with reference to property, Article XVII contains the phrase “un droit inviolable et sacré” (an inviolable and sacred right), which is translated as “dakilà at di magagahas [sic] na karampatan” (great and inviolable right). (A typographical error has rendered the correct Tagalog word magagahis [can be violated/subdued/overpowered] as magagahas.)

To summarize, the Tagalog translation of the Déclaration attempts to express the following ideas in relation to karampatan (right): (1) tao are born paris-paris (equal); (2) tao are born with “karampatang paris-paris” (equal rights); (3) these karampatan that tao are born with are “di magagahis” (cannot be taken away); (4) tao possess the karampatan to “pagsuay sa umaapi” (disobey/revolt against the oppressor).

The Tagalog translation clearly elides all translations for difficult concepts pertaining to droit such as naturel, imprescriptible, and inaliénable. The main reason for these elisions is probably that each of these individual concepts may not have had any straightforward terminological equivalents in late nineteenth century Tagalog. The result is that these concepts, so important in providing the ideological background of the Déclaration in contractualist and natural law perspectives, simply disappear. The main innovation of this text is that it introduced what may have been one of the first Tagalog translations of “human rights” as “karampátan ñg tao.”

“Karampátan ñg Tao” and Notions of “Worthiness”

The Tagalog tao derives from the Proto-Austronesian (PAN) *Cau, which means “person” or “human being” (Greenhill et al. 2008). Its closest cognates are tau, tawo, and tawu, which are found throughout the Philippine archipelago (Ilokano [tao], Ilonggo [tawo], Cebuano [tao/tawo], Bikol [tawo], etc.). Tao and its closest cognates are also spread out in the present-day territories of Malaysia and Indonesia in Sabah (tau), Sarawak (tau), Sulawesi (tau/tawu), and Sumba (tau). It is found in the languages of Papua New Guinea in New Britain (tau) and Port Moresby (tau). Much farther east, one also finds it on the island of Guam (tao).

The first printed bilingual and biscript book in Tagalog and Spanish, the Doctrina Christiana, en lengua española y tagala (Christian doctrine in Spanish and Tagalog languages) (1593), contains some of the earliest appearances of tawo/tawu in print. There are 29 occurrences of tawo/tawu in the baybayin writing system spelled as “ta-wo” (human being). Some of the more relevant usages are “nagkatawan tawo” (to take on a human form), “ang pagkatawo niya” (his humanness, human quality, or nature), “kapuwa mo tawo” (your fellow human being), and “lahat ng tawo” (all human beings). It is hard to determine whether some of these constitute new usages and collocations due to translational processes or whether they belong to older cultural-linguistic strata. However, an extant recorded usage of perhaps much older provenance from the Philippine area, though not in Tagalog, may be found in an idiom present in the ambahan poetic form written in the Hanunoo language in the Mangyan writing system, ᜨᜳᜤᜦᜯᜳᜧᜲᜥᜭ (no ga tawo di ngaran) (Postma 2005, 64). This can be unpacked very literally as “if something appears to be that to which the name tawo can be applied.” In this particular case, being a tao, or pagkatao, is not simply a given but something which must be ascertained before one can relate to that being as a fellow tawo. For example, ᜰᜣᜬᜬᜢᜰᜧ||ᜨᜳᜤᜦᜯᜳᜧᜲᜥᜭ||ᜩᜩᜨᜤᜲᜮᜳᜧᜲᜫ (Sa kang yaya ugsadan/No ga tawo di ngaran/Pagpanagislod diman) may be translated in a more abbreviated form as “to you who are outside the house/if you are a tawo/come in.” A tawo is worthy of hospitality, while a being who is not a tawo is, by implication, unwelcome to enter.

Pedro de San Buenaventura’s Vocabulario de Lengua Tagala (Vocabulary of the Tagalog language) (1613) defines tauo (pronounced ta-wo) as hombre (man) and as persona (person). Interestingly, it also defines the word as “estos Tagalos por si mismo, a diferencia de los demás naciones. Dilì tauo at Castila” (these Tagalogs themselves, in contradistinction with other nations. Not a tao, rather a Spaniard). In contrast with this, however, ca-taou-han is defined in the same dictionary as humanidad (humanity) in a presumably broader sense. It is significant that San Buenaventura’s dictionary recorded what may have been a pre-Hispanic “anthropological nominalism” which did not yet recognize the usage of tauo as a universal category translatable as “human” (Losurdo 2019, 424). The third edition of Juan Jose de Noceda and Pedro de Sanlucar’s Vocabulario de la Lengua Tagala (Vocabulary of the Tagalog language) (1860) more conventionally defines tauo as gente (people, folk) and gives an example followed by a translation: “Mey tauo sa Simbahan, hay gente en la Iglesia” (There are people in the church). Like San Buenaventura, Noceda and Sanlucar also define cataouhan as humanidad. However, the question arises whether cataouhan was a Tagalog concept existing originally independent of Christian theology or whether it was devised specifically by the Spaniards to serve as an equivalent to humanidad, which had its origins in a specifically European Christological vocabulary (Bödeker 1982, 1063). The philosophically realist, and probably newer, usage of cataouhan as a synonym for humanidad may indicate a crucial transition from nominalism to realism in the history of tauo. In noting this, it is not being asserted that the resulting term cataouhan is flatly “non-indigenous,” since such a stark distinction between the “indigenous” and “non-indigenous” does not make any sense in translational studies which cannot rigidly bracket out one side from the other. Cataouhan now simply exists until the present day in the Tagalog language.

The updated 1860 edition of Noceda and Sanlucar’s Tagalog dictionary is separated by only a few decades from Rizal’s Tagalog translation of the play Wilhelm Tell. Rizal undertook the translation in 1886–87 during his stay in Germany upon the request of his brother Paciano (Schiller 1907; Guillermo 2009c). The latter was apparently keen on using it for nationalist propaganda purposes. Originally published and performed in 1804, this play is considered Friedrich Schiller’s (1759–1805) most popular and politically significant play (Schiller 2000). It is important to note that Wilhelm Tell was written during a significant period of transition in the development of modern European (and specifically German) political concepts called the Sattelzeit (Koselleck 1972; Guillermo 2009c). Koselleck invented the term Sattelzeit (saddle period) to refer to the historical period between the middle of the eighteenth and the middle of the nineteenth centuries, when the most important European political and social concepts supposedly obtained their present and more recognizably “modern” meaning. Schiller’s play was composed right in the middle of this period.

It so happened that the era in which Schiller was writing was when modern conceptualizations of the German idea of Menschlichkeit (humanity in the moral sense) (as well as humanité in French) were also consolidating and taking shape. According to Henri Duranton (2000, 11–12), the history of the concept of humanité in French from the seventeenth century onward reveals three major strands: (1) “le caractère de ce qui est humain or la nature humaine” (the character of that which is human or human nature); (2) “un sentiment du bonté, de bienveillance pour son prochain qui fait éprouver compassion ou pitié pour le reste des hommes” (a sense of kindness, of benevolence for one’s neighbor which makes one feel compassion or pity for the rest of mankind); (3) “le genre humain dans son ensemble, tous les hommes” (humankind as a whole, all men). On the other hand, in the German language the theological senses of Menschheit carried over into the eighteenth century in the senses of Mitmenschlichkeit (humanity) and Nächstenliebe (love for one’s neighbor). In the same period, the quantitative and collective meaning of Menschheit denoting all human beings (alle Menschen), formerly very rare, began to enter popular usage in Germany (Bödeker 1982, 1063–1064). In broad strokes, one observes the existence of two main tendencies in both French and German in employing humanité and Menschheit as generic terms for the human species as well as in reference to the possession of certain moral-ethical attributes.

With respect to Rizal’s Wilhelm Tell translation, an observable feature is his penchant for translating, or neutralizing, several different German words into single Tagalog equivalents (Guillermo 2009c, 174). Tao is one of the most interesting cases. Generic concepts of tao such as Mensch (human being, person), Mann (man), or Leute (people, folk) are more or less unproblematically made equivalent to tao as this has been defined in the Spanish dictionaries as hombre, persona, and gente. For example, the sentence “Wo Mensch dem Menschen gegenübersteht” (Where a human being [Mensch] faces another human being) is translated as “kapag sa tao humahadlang ang kapwa tao” (when a human being [tao] is obstructed by his or her fellow human being). More interesting are Rizal’s idiomatic translations of German Menschlichkeit in the following examples:

Wenn Ihr Mitleid fühlt und Menschlichkeit– Steht auf! (If you feel compassion and possess humanity—stand up!)

Kung kayo ay may habag at may pagkatao. Tumindig kayo! (If you feel compassion and possess humanity. Stand up!) (Guillermo 2009c, 148)

Du Glaubst an Menschlichkeit! (You have faith in humanity!)

Naniniwala ka sa magandang loob ng kapwa tao! (You believe in the innate goodness of your fellow human being!) (Guillermo 2009c, 100)

Pagkatao, equated in the first example with Menschlichkeit, therefore implies not just the fact that one can be counted as human but also that one feels a moral sense of responsibility for other human beings. The second example shows how Rizal tried to define rather than translate Menschlichkeit in Tagalog as “magandang loob ng kapwa tao” (innate goodness of fellow human beings). In Rizal’s translation of Menschlichkeit as pagkatao, it therefore appears that pagka-tao (being human) implies not only the bare fact of one’s existence as a tao but also one’s possession of the moral-ethical attributes associated with the concept of a human being.

Another interesting translational record for understanding the meaning of tao and pagkatao as compared with Rizal’s usage is a Tagalog translation of a famous nineteenth-century anarchist pamphlet. It is said that one of the books which served as the basis for the Constitution of the Union Obrera Democratica, the first Philippine labor union—established in 1902—was Fra contadini: dialogo sull’anarchia (1884) by the Italian anarchist Errico Malatesta (1853–1932). This pamphlet was translated into Tagalog in 1913, most likely from a Spanish version, by Arturo Soriano under the pseudonym Kabisang Tales (a character from Rizal’s El Filibusterismo) and published as Dalawang magbubukid (entre campesinos): mahalagang salitaan ukol sa pagsasamahan ng mga tao (Two peasants: Important conversations about human society) (1913) (Sison 1966; Scott 1992). Little information is available about Soriano. He worked as a printer and became a leading member and officer of the Union de Impresores de Filipinas, Katipunan Anak ng Bayan (Association of the Sons of the People) as well as the PKP (established in 1930) (Richardson 2011, 25). Because the original Spanish source text cannot yet be identified, the most accessible Spanish translation by the anarchist writer Diego Abad de Santillan (1897–1983) will have to serve as a kind of hypothetical point of comparison. For example, words appearing in the Spanish translation such as gente (people, folk) and persona (person) are rendered as tao in the Tagalog. However, the instances in the Spanish translation where humano (human) appears seem to be rather more complex. On the one hand, “género humano” (human species) in the Spanish, or the fact of existing as a human as defined by some common attributes, appears in the Tagalog as pagkatao (to be human). On the other hand, “deber humano” (human duty), the moral dimension of being human in the Spanish, appears in the Tagalog as pagpapakatao (literally translatable as “the striving to become fully human”).

One can observe here some kind of misalignment with Rizal’s translations of Mensch as tao and of Menschlichkeit as pagkatao. In Rizal’s case, tao can be interpreted as pertaining to the mere fact of existing as a human while pagkatao (being truly human) could be understood as the state of possessing the moral-ethical attributes of genuine humanity. In contrast with this, Soriano’s translation implies that pagkatao simply pertains to existing as a member of the “género humano” (human species), whereas pagpapakatao refers to the striving to become truly human. In spite of this, both Soriano’s and Rizal’s renderings imply, in different ways, the Tagalog folk saying “Madali maging tao pero mahirap magpakatao” (It is easy to be a human [tao] but difficult to become a human being [pagka-tao]), which suggests a gap between merely existing as a human being on the one hand and attaining one’s essence as a human being on the other.

The difference between Soriano’s and Rizal’s translations reveals a certain ambivalence in the meaning of pagkatao, which might even be traceable to the (pagkatawo) in the Doctrina Christiana of 1593. Following Soriano’s usage, pagkatao could simply be taken as pertaining to the mere fact of existing as human (pagka-tao). However, Rizal’s interpretation of pagkatao as a translational equivalent of Menschlichkeit means that a person who has pagkatao has attained the moral-ethical attributes associated with truly being a tao. The question which arises is, can one become a tao without undergoing the process of pagpapakatao? If the answer is in the negative, what is the status of a tao which has not yet become tao through pagpapakatao? The first meaning of tao takes pagkatao as the starting point and premise, while the second meaning takes it as the endpoint.

If the tao in “karampátan ñg tao” is an ambivalent concept, what then of karampátan? The use of the word karampátan/karapatan as “right” was in fact rather novel at the turn of the twentieth century. Its collocation with tao was therefore a relatively new linguistic innovation in Tagalog. In order to look more closely at this idea of “karampátan ñg tao” (human rights), one would have to look at the development of the concept of “rights” in Tagalog.

The earliest Tagalog dictionary, by San Buenaventura (1613), does not mention karapatan but defines Spanish derecho (“right”/“law”) in the sense of “straight” as matouir. The 1754 edition of Noceda and Sanlucar’s Tagalog dictionary also defines derecho as matoid/matouid (straight). However, carampatan appears there as the Tagalog equivalent of ajustamiento (fitting) and mediania (average). In Domingo de los Santos’s Tagalog dictionary (1794), derecho is once again defined as matouir (straight). Carampatan also appears but as an equivalent to razonable (reasonable). And for the first time in a Tagalog dictionary, carapatan appears in De los Santos with the meaning merecimiento (deserving, worthy). In the updated 1860 edition of Noceda and Sanlucar’s dictionary, derecho appears again as matoid (straight) while carampatan (and catampatan) is defined as justo (fair, just), razonable (reasonable), and mediania (average). However, the later edition contains carapatan, which is defined as aptitud (suitable) and mérito (worth). The Serrano Laktaw dictionary (1889) again defines derecho as matowid (straight) and katowiran (reason). Karapatan (now spelled in the modern way with the letter “k”) is given quite a few equivalents, which include dignidad (dignity), mérito (worth), merecimiento (being deserving, worthiness), and aptitud (suitable). For its part, the Calderon Tagalog dictionary (1915) defines derecho (law, justice, fairness) both as matwid and as karampatan. On the other hand, karapatan is still considered equivalent to dignidad (dignity), mérito (worth), merecimiento (worthiness), and aptitud (suitable).

It was therefore only in the 1860 edition of the Noceda and Sanlucar dictionary and in the Calderon dictionary of 1915 that carampatan began to be equated with derecho (right). These earlier dictionaries stand in contrast with the modern Tagalog-English dictionary of Vito Santos (1978), which plainly distinguishes between karapatan defined as the equivalent to the English “right(s)” and Spanish derecho(s) and its other, older meaning as “deserving” and “worthy,” which is now equated with the Tagalog karapat-dapat. Karapatan never seemed to escape its meaning as “worthiness” in dictionaries from 1613 to 1918.

Collected Katipunan texts (Richardson 2013) show at least twenty appearances of karapatan. Most of these occurrences can be understood without much ambiguity as still pertaining to “worthiness.” For example, a person has to pass certain trials to prove that he is “may karapatang tanggapin” (worthy of being accepted) into the organization. Another usage equates karapatan with “what is necessary.” For example, the phrase “sa karapatang kami’y magsidalo” is best understood as “the necessity that we should attend.” The same holds for “tamuhin natin ang . . . kaunting karapatan sa kabuhayan ng tao,” which should be read as “to enjoy the few necessities in human life.” Another possible meaning of karapatan is “capable of,” which can be seen in the sentence “Tunay na kami ay umasa din, gaya ng makapal na mga kababayan na nagakala na ang inang España ay siyang tanging may karapatang mag bigay ng kaginhawahan nitong Katagalugan” (It is true that we hoped like many of our countrymen who thought that Mother Spain was the only one capable of bringing prosperity to the Katagalugan). The phrase “taong may tunay na karapatang magpanukala” may indeed be read as “the person with a right to make a proposal.” However, this “right” depends on the “merit,” “privilege,” or “entitlement” of the person in question. It could just as well be understood as “the person who is entitled to make proposals.” The same persistent connection of karapatan with worthiness holds for the self-translation by the lawyer and revolutionary leader Apolinario Mabini (1864–1903) of his Programa Constitucional de la República Filipina (1898) into Tagalog as Panukala sa Pagkakana nang Republika nang Pilipinas (Draft constitution of the Republic of the Philippines) (1898). In this work, carapatan is used as the translational equivalent of digno (worthy), aptitud (suitability), honradez (uprightness), and capaces (capable). On the other hand, derecho(s) is translated most frequently as capangyarihan (power) and catuiran(g). The phrase “derechos individuales” (individual rights) is translated twice as “catuirang quiniquilala . . . sa mga mamamayan” (the recognized right[s] of the people), which also indicates the difficulties encountered in finding a Tagalog equivalent for the word “individual.”

There is thus a dual ambivalence in the terms tao and karapatan, which are both necessary for formulating the notion of “human rights.” A case in point from Malatesta’s (1913, 86) pamphlet is the phrase in the Spanish translation “los hombres tienen el derecho” (Men have the right), which is rendered in Tagalog as “mga tao’y laging may karapatan” (Human beings always have rights). On the one hand, the question arises of whether the tao “always” possesses karapatan by simply being a tao or whether the tao has to go through a process of pagpapakatao in order to claim these karapatan. On the other hand, are karapatan inherent in the tao, or does the tao have to prove his or her moral “worthiness,” being karapat-dapat, to be able to possess karapatan? One possible way of reading this ambivalence is to read it against the notion of the “inherence” of rights. In short, in order to be truly a tao, one must go through a moral process of pagpapakatao, and it is only when one has finally become a tao that one proves one’s worthiness of possessing karapatan. Rights (karapatan) are therefore predicates which are not inherent in the subject (tao).

Schiller’s Wilhelm Tell in Tagalog Translation: “Natürliche und Unveräusserliche Rechte” (Natural and Inalienable Rights)

Rizal’s abovementioned Tagalog translation of Wilhelm Tell consistently used katwiran as the translational equivalent of the German word Recht. For example, Volkes Rechte (the rights of the people) was translated as “katwiran ng bayan” (the right[s] of the people). In contrast to this, Mariano Ponce’s heavily edited version of Rizal’s translation (Schiller 1907) already reflects the shifts in usage at the turn of the century. In this connection, one notes that the literary scholar Christopher Mitch Cerda observed that Felipe Calderon’s (1868–1908) “Ang ABC nang mamamayang Filipino” (The ABCs of the Filipino citizen) already represents, as early as 1905, the slow, indecisive transition from the use of catuiran to carapatan as the translation for derecho(s). In his revised version, Ponce replaced all of Rizal’s translations of Recht as katwiran with karapatan (Schiller 1907). For instance, the German sentence “Das Volk hat aber doch gewisse Rechte” (But the people have definite rights) was originally translated by Rizal as “Ngunit ang bayan ay may ilan din namang katwiran” (But the people do have some rights [katwiran]). Ponce would retain the whole sentence while replacing katwiran with karapatan as follows: “Ngunit ang bayan ay may ilan din namang karapatan” (But the people do have a few rights [karapatan]). Nevertheless, as far as Rizal was concerned, Recht did not pose any insuperable challenge to translation since he had come upon katwiran as a more or less consistent translational equivalent. However, some of Schiller’s most famous lines on rights were much more difficult to translate. For example:

Wenn der Gedrückte nirgends Recht kann finden,

Wenn unerträglich wird die Last – greift er

Hinauf getrosten Mutes in den Himmel,

Und holt herunter seine ew’gen Rechte,

Die droben hangen unveräusserlich

Und unzerbrechlich wie die Sterne selbst

(When the oppressed can find no justice [Recht],

When the burden can no longer be endured—

he reaches up confidently to the sky,

And brings down his eternal rights [ew’gen Rechte],

Which hang above, inalienable [unveräusserlich]

And unbreakable [unzerbrechlich] like the stars themselves) (Guillermo 2009c, 133)

is translated by Rizal as:

Kapag ang nagigipit ay ualang makitang tulong,

kapag ang bigat ng pasa’i lumabis . . .

kukunin nga niyang masaya sa langit at ipananaog sa lupa

ang di matingkalang katuiran nahahayag doon

sa itaas di nababago at di nasisira,

paris din ng mga bituin . . .

(When the oppressed can find no aid [tulong],

When the burden can no longer be endured—

he reaches up happily to the sky and brings down to Earth

the incomprehensible rights [di matingkalang katuiran] proclaimed there,

Hanging above, eternal [di nagbabago] and indestructible [di nasisira]

Like the stars themselves) (Guillermo 2009c, 133)

One notices that Rizal rather idiomatically translates Recht in the stanza’s first line as tulong (help, aid), while ew’gen Rechte (eternal rights) in the fourth is puzzlingly translated as “di matingkalang katuiran” (incomprehensible rights/reason [katwiran]). The “eternal rights” Schiller speaks of which will be grasped from the sky and brought down to Earth obviously pertain to “natural rights.” Unzerbrechlich (unbreakable) in the sixth line is very faithfully translated as di nasisira (cannot be broken). However, problems arise in the translation of unveräusserlich. The German verb veräußern simply means “to sell or alienate.” Unveräusserlich is therefore defined as something which cannot be sold or is “inalienable.” Rizal’s translation of unveräusserlich as di nagbabago (unchanging) clearly does not capture the legal, commercial, and contractualist inflections of the original German concept. Schiller’s equation of “ew’gen Rechte” (eternal rights) with “unveräusserliche Rechte” (inalienable rights) reflects the efforts of natural law thinking to preclude the possibility that one can, through a perfectly legal contractual relationship, divest oneself of one’s own fundamental rights. It attempts to preempt and void the legitimacy of any contract which may be entered into by a willing (or even coerced) subject to sell himself or herself into slavery. Schiller’s play is therefore firmly grounded in the tradition of natural law. A just society is one where the natural rights of human beings are recognized. Schiller’s hypothetical example for one such society is that wherein “der alte Urstand der Natur” (the ancient state of nature) holds. Rizal struggled to translate the idea of Natur in the instances where it occurs in the play (Guillermo 2009c, 172–175). But since there was no available direct translational equivalent for “nature” in late nineteenth century Tagalog, the closest translation he could devise for the abovementioned phrase was “ang matandang lagay ng lupa” (the ancient state/situation of the land). Translating Natur as lupa (land) obviously does not capture any of its philosophical shades of meaning. In terms of the discourse on rights, it is evident that Rizal’s Tagalog translation of Wilhelm Tell found it impossibly difficult to articulate the dominant European philosophical paradigms of contractualism and natural law. It could therefore not move from a representation of rights as “natural,” and therefore “eternal,” to their purported “inalienability.”

Moreover, though the translation tried to convey the idea of Revolutionsrecht (the right to revolution) which an oppressed people could resort to in order to overthrow unjust authority, Tagalog readers might have been stumped over what this puzzling talk about “di matingkalang katuiran” was about. The conceptual equivalents of unveräusserlich and Natur in the German Wilhelm Tell and inaliénable and nature in the French Déclaration therefore find no Tagalog translations. There is thus a translational impasse which needs to be overcome.

Jacinto’s “Liwanag at Dilim”: “Ang Katwirang Tinataglay na Talaga ng Pagkatao”

Like Rizal’s Wilhelm Tell translation, and in contrast with the Tagalog translation of the Déclaration (from around four years earlier), Emilio Jacinto’s (1875–99) famous politico-philosophical essay “Liwanag at Dilim” (Light and darkness) (1896) (Almario 2013, 154–176) does not have any mention of the words karapatan and karampatan, in the sense of rights, at all. However, it is incontestable that in some cases, and consonant with both Rizal’s earlier and Mabini’s later usage, Jacinto—often referred to as the “Brains of the Revolution”—employed katuiran and matwid in a similar sense as rights. It must nevertheless be emphasized that this usage unavoidably induces semantic slippages between the two dominant translational meanings of katuiran as “right” and as “reason.” For example, a sentence from Article IV of the Déclaration of 1789 is as follows:

La liberté consiste à pouvoir faire tout ce qui ne nuit pas à autrui: ainsi, l’exercice des droits naturels de chaque homme n’a de bornes que celles qui assurent aux autres Membres de la Société la jouissance de ces mêmes droits.

(Liberty consists in being able to do anything which does not harm others: therefore, the exercise of the natural rights of each person is not limited except by the assurance that other members of society will enjoy the same rights.)

This is translated very incompletely in the Tagalog translation of the Déclaration attributed to Rizal with the simple sentence “Kalayahan [La liberté] ay ang makagawâ ñg balang [à pouvoir faire tout] dî makasasamâ sa ibá [qui ne nuit pas à autrui]” (Freedom is being able to do whatever does not harm others) such that, as has been remarked above, the phrase “droits naturels” (natural rights) is completely elided. For Jacinto’s part, his short text contains a version of Article IV and a definition of kalayaan (freedom) which is somewhat more complete but also quite free: “Ang kalayaan ng tao ay ang katwirang tinataglay na talaga ng pagkatao na umisip at gumawa ng anumang ibigin kung ito’y di nalalaban sa katwiran ng iba” (The freedom of a human being is the right [katwiran] truly possessed in being human [pagkatao] to think and act according to what he desires as long as this does not come in conflict with the rights [katwiran] of others) (Almario 2013, 156).

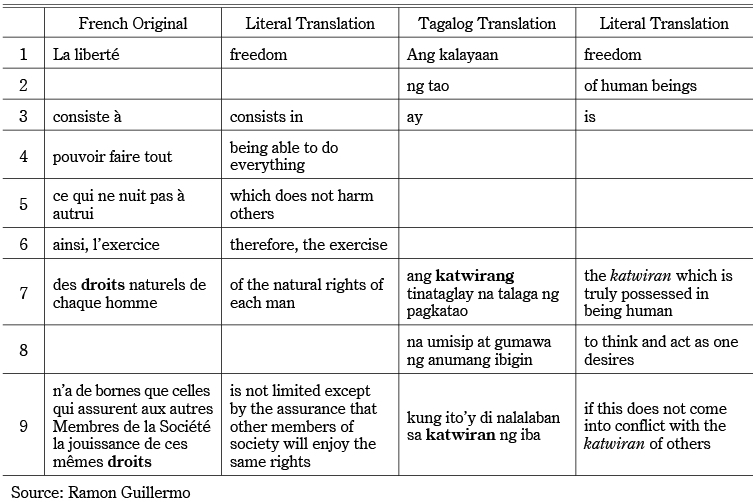

Possible translational correspondences with Article IV of the Déclaration may be unpacked as shown in Table 1. Both sentences are plainly definitions of liberté/kalayaan (freedom). Line number 4 from the Déclaration has apparently been shifted translationally to position 8 in Jacinto’s sentence since these correspond closely with each other. This is because the French “pouvoir faire tout” (being able to do everything) is very similar to the Tagalog “na umisip at gumawa ng anumang ibigin” (to think and act as one desires). The latter simply unpacks the “faire tout” (do everything) as applying to both thoughts and deeds (“umisip at gumawa”). Line number 9 from the Déclaration represents the notion that rights should not be limited except in order to ensure that others will be able to enjoy the same rights (“ces mêmes droits”)—that is to say, the free exercise of one’s rights should not come in conflict with the equally free exercise by others of these very same rights. The underlying implication is that rights, under certain conditions, can be limited. This is also the same idea in line number 9 from Jacinto but in simplified form. The Tagalog line simply asserts that one can think and act as one desires as long as one’s thoughts and actions do not conflict with the katwiran of others. Like droit, therefore, the free exercise of katwiran is strictly limited by the assurance that these should not come in conflict with everyone else’s free exercise of these same droit or katwiran. Finally, it is presumed that line number 7 in the Déclaration has received a translation in Jacinto’s line number 7. One can further break down line number 7 into its component parts. The phrase “chaque homme” (each man) corresponds to pagkatao (being human). Droits can be provisionally equated translationally with katwiran. However, as has been pointed out above, naturel (natural) represents a translational obstacle for nineteenth-century Tagalog. How does Jacinto attempt to overcome this? Naturel is apparently translated as “tinataglay na talaga.” The Tagalog word taglay means “to possess,” while talaga means “truly, genuinely, or even designated” (katalagahan in its theological usage means “what is preordained”). “Tinataglay na talaga” thus seems to emphasize the unquestionable and rightful possession of something within a particular theo-cosmological non-naturalistic conception of the world.

Table 1 Possible Translational Equivalences between Article IV of the Déclaration and Jacinto’s “Liwanag at Dilim”

One sees, therefore, that unlike the earlier Tagalog translation, Jacinto here seems to make a serious attempt to render the phrase “droits naturels de chaque homme” (natural rights of each human being) as “katwirang tinataglay na talaga ng pagkatao” (katwiran truly possessed in being human). One ought to emphasize here how the conceptual inherence of katwiran (right) in pagka-tao (being human) now finds expression in Tagalog without having to resort to any direct translational equivalent for “natural.” Moreover, given the plausible translational impulse behind it, this is one instance where katwiran may be understood as standing in for “right.” This interpretation is further reinforced by the explicit assertion that rights cannot simply be exercised without restraint and may be limited (borner) in order to ensure the universalizability of these rights perhaps in the sense of Immanuel Kant’s (2016, 28) statement “ich soll niemals anders verfahren, als so, daß ich auch wollen könne, meine Maxime solle ein allgemeines Gesetz werden” (I should never act otherwise than that I could also want my maxim to become a general law).

One must, however, take note of all the semantic slippages which the word katwiran generates. The very next sentence states, “Ayon sa wastong bait, ang katwirang ito ay siyang ikaiba ng tao sa lahat ng nilalang” (According to good conscience, this [capacity to] reason is what differentiates human beings from other creatures) (Almario 2013, 156). This usage seems to straightforwardly refer to “reason” rather than rights. The translational neutralization of both “rights” and “reason” in Tagalog as katwiran can therefore lead to grave difficulties in interpretation. One could conceive of different possible ways of reading Jacinto’s definition of kalayaan, which could interpret katwiran as “rights,” “reason,” or even a synthesis of both. However, there are also other usages of the related word matwid in the same essay which are close to the sense of “right” (Guillermo 2009c, 143). The following passage is an example:

Datapwat ang katotohanan ay walang katapusan; ang matwid ay hindi nababago sapagkat kung totoo na ang ilaw ay nagpapaliwanag, magpahanggang kailanman ay magpapaliwanag. Kung may matwid ako na mag-ari ng tunay na sa akin, kapag ako’y di nakapag-ari ay di na matwid.

(Since truth is eternal; what is just [matwid] does not change because if it is true that light enlightens, it will give light eternally. If I have the right [matwid] to own something that is really mine, if I do not own it, this is not just [matwid]). (Almario 2013, 159)

One sees in the selected passage how matwid can be used to refer translationally to “right,” “reason,” and what is “just.” The phrase “ang matwid ay hindi nababago” (justice/right does not change) adds the attribute of “permanence” to the katwiran/matwid, which is “taglay ng pagkatao” (an attribute of being human). Another similar usage of matwid in Jacinto’s essay is in the phrase “pagsasanggalang ng mga banal na matwid ng kalahatan” (the defense of the sacred rights [matwid] of all). “Banal na matwid” (sacred matwid) is “les droits sacrés” (sacred rights) in the Déclaration. If one is unable to defend these rights (which are made plural by mga), it may happen that “muling maagaw ang iyong mga matwid” (your rights [matwid] will once again be taken from you). Being deprived of one’s rights through force (maagaw), or even by one’s own neglect or acquiescence, does not at all mean that these have suddenly lost their inherence. It just means that the aim of the “political association” mentioned in Article XII of the Déclaration, which is the “conservation des droits naturels et imprescriptibles de l’homme” (preservation of the natural and imprescriptible rights of man), has not been adequately achieved.

Even though Jacinto does not use the word karapatan itself, it seems that his usage of katuiran in its stead actually paved the way for a concept of “right” in Tagalog which could detach itself from the discourse of “worthiness.” Despite the interpretative issues engendered by the translational neutralization of “right” and “reason” as katwiran, one possible and very important advantage of katwiran is that it is able to circumvent the abovementioned semantic ambivalences of karapatan. This is arguably the case with Jacinto’s abovementioned possible translation of “natural right” in the sense of inherence, as “katwirang tinataglay na talaga ng pagkatao” (katwiran truly possessed in being human). How then does Jacinto deal with the observed ambivalences of tao, pagkatao, and pagpapakatao? It is here that his assertion of the equality of rights is significant. According to him, “Ang lahat ng tao’y magkakapantay sapagkat iisa ang pagkatao ng lahat” (All human beings are equal because they share in a single humanity). Furthermore, “At dahil ang tao ay tunay na magkakapantay at walang makapagsasabing siya’y lalong tao sa kanyang kapwa” (And because human beings are really equal and no one can say that he or she exceeds the humanity [lalong tao] of his or her fellow human being). Finally, one can add here Jacinto’s declaration in the “Kartilya” of the Katipunan (1892) that “Maitim man at maputi ang kulay ng balat, lahat ng tao’y magkakapantay; mangyayaring ang isa’y higtan sa dunong, sa yaman, sa ganda . . .; ngunit di mahihigtan sa pagkatao” (One’s skin may be dark or white, but all human beings are equal; one may be more learned, wealthier, more beautiful than another . . .; but cannot exceed the other in humanity [mahihigtan sa pagkatao]) (Almario 2013, 143).

Jacinto does not leave any doubt about his notion of pagkatao. All those born as human beings, with no exceptions, are equal by birth because they all share in a single pagkatao. No one can claim that he or she is “lalong tao” (more human) or “higit ang pagkatao” (more of a human being) than anyone else. And because everyone is equally human, they also equally possess the “katwirang tinataglay na talaga ng pagkatao” (katwiran truly possessed in being human) as inherent attributes. It is true, however, that the label tao sometimes seems to no longer fit its referent in Jacinto’s ruminations. According to him, “Kung sa tao’y wala ang kalayaan ay dili mangyayaring makatalastas ng puri, ng katwiran, ng kagalingan, at ang pangalang tao’y di rin nababagay sa kanya” (If a human being is not free, he or she cannot discern honor, rights, good, and the name human [tao] is no longer fitting) (Almario 2013, 156). It seems that Jacinto is here raising the possibility that the name tao can no longer be an appropriate signifier for a person. The crucial question therefore arises: Can a tao actually lose his or her pagkatao in Jacinto’s thinking? Can a tao stop being a tao? In order to answer this, one must carefully consider the following passages:

Ay! Kung sa mga Bayan ay sukat nang sumupil ang kulungan, ang panggapos, at ang

panghampas katulad din ng hayop ay dahil sa ang mga A.N.B. ay di tao, pagkat ang

katwiran ng pagkatao ay namamatay na sa kanilang puso.

(Ay! If the bayan can be suppressed by jails, shackles, and floggings like an animal [hayop], it is because the sons and daughters of the people are not tao [di tao], because the reason [katwiran] of their being human [pagkatao] is perishing in their hearts.) (Almario 2013, 156)

Bakit ang Tagalog ay kulang-kulang na apat na raang taong namuhay sa kaalipinan na pinagtipunang kusa ng lahat ng pag-ayop, pagdusta, at pag-api ng kasakiman at katampalasan ng Kastila? . . . Dahil kanyang itinakwil at pinayurakan ang Kalayaang ipinagkaloob ng Maykapal upang mabuhay sa kaginhawaan; at dahil dito nga’y nawala sa mga mata ang ilaw at lumayo sa puso ang kapatak mang ligaya.

(Why have the Tagalog lived for almost four hundred years in slavery accumulating humiliation, degradation, and oppression under the greedy and villainous Spaniards? . . . Because s/he has rejected [itinakwil] and allowed the freedom [kalayaan] God gave him/her to be trampled upon [pinayurakan] in order to live in comfort; and because of this his/her eyes have lost their light and his/her heart feels not a drop of happiness.) (Almario 2013, 158)

These passages seem to point to a state of affairs where the tao loses his or her character of being a tao and becomes its conceptual opposite, a hayop (animal). Indeed, Crisostomo (2021, 278–279) believes that this is an argument for the alienability of rights in Jacinto. However, as a corrective, Jacinto’s rhetorical question must be understood in light of other, more axiomatic, passages such as the following: “Kung sa santinakpan ay walang lakas, walang dunong na makakakayang bumago ng ating pagkatao, ay wala rin namang makapakikialam sa ating kalayaan” (If the universe does not have any power, no intelligence which can change our being human [pagkatao], there is also nothing which can impede our freedom) (Almario 2013, 156).

Jacinto quite clearly asserts in these lines that nothing in the universe (santinakpan) can change the nature of pagkatao. Even under extreme conditions of subjugation, kalayaan (freedom) cannot completely die out in the heart of the tao and the light of reason cannot fully be extinguished in his or her eyes. For Jacinto, therefore, the “katwirang tinataglay na talaga ng pagkatao” (katwiran truly possessed in being human) will necessarily remain unchanged under any circumstances, even the most oppressive ones.

As a point of comparison, one can consider the following sentence from Rizal’s essay for the women of Malolos: “taong walang sariling isip, ay taong walang pagkatao; ang bulag na taga sunod sa isip ng iba, ay parang hayop na susunod-sunod sa tali” (a human being who cannot think for herself is a human who lacks the attributes of being human; the blind who merely follows what others think is like an animal that is tethered to a rope) (Rizal 1961b). In this case, the tao has become similar or comparable to a hayop or animal. One should emphasize Rizal’s usage of parang (like, similar to). In other words, he stops short of considering the actual conversion of tao into hayop. Rizal’s very notion of “taong walang pagkatao” (a human who lacks the attributes of being human) points to an aporia. It means that someone who lacks pagkatao (the attributes of being human) cannot be called a hayop but must still be called a tao. This implies that the rights of pagkatao which may have been taken away by the oppressor are nevertheless still inherent in each tao and may be restored. The name of the entity called tao does not change even though he or she may fail to live up to what is considered the essence of being tao. What Jacinto and Rizal actually gesture toward is the notion that even as pagkatao is inherent in terms of rights as a political principle, it is still paradoxically something which should be striven for as moral beings. In other words, a human can be “inhuman” or can still lack humanity but nevertheless remain indubitably human.

In short, Jacinto’s phrase “katwirang tinataglay na talaga ng pagkatao” (right[s] truly possessed in being human) heralds the formulation of something approximating the notion of rights inherence in Tagalog. His further clarifications of katwiran as something that is hindi nagbabago (unchanging) and of pagkatao as being indisputably magkakapantay (equal) put to rest any remaining ambivalences. But if rights are indeed inherent, how does one explain conditions where humans are deprived of them? The original founding document of the Katipunan (dated January 1892) sheds some light on this question. Paragraph 18 of the first section, titled “Casaysayan” (History), contains the following:

Nangag papangap na manga lalaquing maningning (ilustrados) may pinag aralan at conoa,i, manga majal, datapoa,i, labis ang manga cabastosan at dito y maquiquita. Sa alin mang pulong nang manga Castila ay ang tagalog na mapaquilajoc ay ibinibilang na alangan sa canilang pag catauo at cung magcaminsan ay jindi pa aloquin nang luclocan (baga man maningning na capoa nila,) lalo pa cung pumapanjic sa canilang manga tirajang bajay; datapoa cung sila ang naquiquituloy ay ualang pagcasiyajan ang nang mga tagalog at sila,i, sinasalubong nang boong ucol at pag irog, tuloy ipinag papalagay jalos na silay manga Dioses, bucod pa sa ganoong manga asal ay balang tagalog na causapin jindi iguinagalang caunti man caya ngat ang mapuputi na ang bujoc sa catandaan, ano man ang catungcolang, jauac ay cung tauagin ay icao, tuloy tutungayaoin ng negro o chongo. ¿Ganito caya ang naquiquicapatid? Jindi cung di ganoon ang naquiquipag cagalit at jumajamon nang auay o guerra.

(The pretensions of the enlightened men [ilustrados] who have education and profess to be highborn, but of excessive rudeness [cabastosan] which can be observed here. In any meeting among Spaniards joined by a Tagalog whose person [pag catauo] is considered unworthy of such company, he is sometimes not even offered a seat [even though he is just as enlightened as they are], especially if they are in a Spaniard’s house; on the other hand, if they enter the house of a Tagalog, they are received enthusiastically with respect and love so that they believe themselves to be gods. Aside from this behavior, they do not speak with the least respect to all Tagalogs so that they use informal modes of address even with those whose hair is white with age, regardless of their official positions, even to the point of calling them “niggers” or “monkeys.” Is this the way to demonstrate fraternity? No. Because this is the way to express hatred and challenge the other to a fight or to a war.) (Richardson 2013, 8)

The paragraph seems to be a dramatization of a typical encounter between Spaniards who claim to be “enlightened” and upper-class Tagalogs. Spaniards are said to be excessively bastos (uncouth, rude) in their dealings with Tagalogs based on the following: (1) in the Spaniard’s house, they sometimes do not even offer a seat to the Tagalog who is present; (2) they use informal modes of address even for Tagalogs of advanced age or high status; and (3) they even hurl insults at Tagalogs, calling them “monkeys” or “Negroes.” In contrast to this, they behave as if they are gods who should be worshipped by the indios. This disparity is explained, according to the paragraph, by the fact that Spaniards consider Tagalogs as “alangan sa canilang pag catauo” (not quite equal to their human-beingness). In Jacinto’s phrasing, therefore, they consider themselves to be “lalong tao” (more human) or “higit ang pagkatao” (more of a human being) compared to Tagalogs. As such, they consider Tagalogs—and of course indios as a whole—not necessarily as “lower” fellow human beings or subhumans but perhaps even as hayop who can be called chongo (monkey). Certainly, taking offense at being called a negro could be problematic since it may draw from the same European racist sentiment which may have been imbibed by some ilustrado indios. However, one ought to remember Jacinto’s assertion that “Maitim man at maputi ang kulay ng balat, lahat ng tao’y magkakapantay” (The skin may be dark or light, but all human beings are equal). The fact is that the Spaniards in this dramatization refuse to “recognize” the equal humanity of indios (as well as “Negroes”). The Katipunan founding document thus finds no other recourse to rectify this degrading situation than to declare pag jiualay (separation) from Spain since the nonrecognition of the humanity of indios is tantamount to “jumajamon nang auay o guerra” (challenging to a fight or war). As Jacinto wrote: “Ang Kalayaan nga ay siyang pinakahaligi, at sinumang mangapos na sumira at pumuwing ng haligi at upang maigiba ang kabahayan ay dapat na pugnawin at kinakailangang lipulin” (Freedom is the very pillar, and whoever puts it in chains to destroy the pillar and demolish the house must be crushed and annihilated) (Almario 2013, 157).

To revolt against the oppressor, to “lipulin at pugnawin” (annihilate and crush) him, is not only possible but also a duty of those who have been deprived of their freedoms. This is fully in accord with Article II of the Déclaration regarding the right to revolt against oppressors (“la résistance à l’oppression”), translated into Tagalog as “pagsuay sa umaapi” (to challenge the oppressor). The responsibility of the revolutionaries is then to create a society where these rights of the indios are recognized and which is capable of “pagsasanggalang ng mga banal na matwid ng kalahatan” (protecting the sacred rights of all). As Article II of the French Déclaration states, “Le but de toute association politique est la conservation des droits naturels et imprescriptibles de l’Homme” (The goal of all political association is the conservation of the natural and inalienable rights of Man). Ironically, therefore, the verbal declaration of the inherence of rights requires at the same time a foundational revolutionary act of making these rights truly inherent in the human being.

The Rise of the Labor Movement and the Modern Discourse of Karapatan

The direct appropriation of Jacinto’s phrase “katwirang tinataglay na talaga ng pagkatao” (right[s] truly possessed in being human) can be observed in the labor leader Hermenegildo Cruz’s (1880–1943) short text on the founding of a Workers’ School (Paaralan ng mga Manggagawa) in the early years of the twentieth century: “Sa makatwid ang ipinakikilala ng Derecho Natural ay yaong mga katwirang katutubo, na taglay ng tao sa kanyang pagkatao . . .” (Therefore, what Derecho Natural [natural right] introduces are those innate rights which are possessed by a human/person in his or her being human) (Cruz 1905). One notices here the use of both taglay (to possess) and katutubo (innate/inborn) even as the word used for “right(s)” continued to be katwiran. Cruz was also the president of the Gremio de Impresores, Litografos y Encuardenadores (Guild of Printers, Lithographers, and Binders), which had earlier published a “Plataforma y Constitución” (Platform and constitution) (1904). In the Tagalog translation accompanying the Spanish document, which was kindly supplied by the scholar Mitch Cerda, one observes the translation of “derechos de asociados” (rights of members) as “karapatan ng mga kasapi” (rights of members) as well as a generally consistent usage of karapatan as an equivalent for derecho(s) in the text itself.

However, the full-blown transition to the more contemporary modern idiom was accomplished by Lope K. Santos (1879–1963), Cruz’s contemporary and fellow teacher at the aforementioned Workers’ School. The latter was an important labor leader and the first president of the Union del Trabajo de Filipinas (Philippine Labor Union) (Richardson 2011, 21). He is also considered a foremost Filipino journalist and prominent Tagalog writer.

Santos’s socialist novel Banaag at Sikat ([1906] 1993) powerfully reflects the dominant usage of karapatan at the turn of the twentieth century. One already sees here the fully developed and modern concept of karapatan as rights. This novel contains a more sure-footed translation of “natural rights” as “mga katutubong karapatan” (innate or inborn rights), which is still familiar to most Tagalog speakers of the present day. Santos also includes in the novel formulations such as the right of the worker to the fruits of his or her labor, such as “karapatang makinabang sa bagay na pinagtulungan” (right to benefit from something produced cooperatively) and “pag-uusig ng kanyang karapatan sa nagagawa” (his or her demand for his or her right to what he or she has produced). One also finds phrases here such as “karapatan nang mabuhay” (right to live) and “karapatan sa buhay” (right to life), which, in relation to proletarian demands, more explicitly come in tension with the “sacred” bourgeois right to private property as stated in Article XVII of the French Déclaration.

It is in this regard that Santos’s novel contains perhaps the first printed instance in Tagalog of describing karapatan in the context of what was then a new word, kalikasan. The first appearance of this word in a Tagalog dictionary as the equivalent of natural and naturaleza was apparently much later, in 1922 (Ignacio 1922; Guillermo 2009c, 172). This word had just been invented to serve as a direct equivalent to naturaleza (nature) and now began to form a conceptual bond with karapatan though its root word likas. The phrase “likas na karapatan,” though not present in Santos’s novel, is still in use today as a result of this process. Santos describes the “karapatan nang mabuhay” (right to life) as follows:

Paglitaw ng tao sa ibabaw ng lupa ay may karapatan nang mabuhay. Ano mang kailangan niya’y naririto rin lamang sa lupa ay di dapat pagkasalatan. Ang kalikasan o Naturaleza ay mayamang-mayamang hindi sukat magkulang sa pagbuhay sa lahat ng tao. Ang umangkin ng alin mang bahagi o ari ng Kalikasan, ay pagnanakaw. Ang mag- ari o sumarili ng ano mang bagay na labis na sa kailangan ng kanyang buhay, at kakulangan ng sa iba, ay pangangamkam at pagpatay sa kapwa. Ang lupa at ang puhunan, ay siyang lalung- lalo nang hindi maaaring sabihing akin, ni iyo, ni kanya, kundi atin: sapagka’t ang una’y pinaka-punlaan ng mga binhi ng buhay na panlahat, at ang ikalawa’y pinaka-kasangkapan sa pagbuhay ng mga itinatanim ng paggawa ng lahat.

(As soon as a human being appears on the surface of the earth, he or she has the right to life. Everything he or she needs is on this earth and should be sufficient. Nature is bountiful and can never be lacking in providing for all human beings. The appropriation of any part or ownership of Nature is thievery. To own or take for oneself more than what a person needs for his/her life and deprive others is pillage and murder of one’s fellow human being. Land and capital cannot be said to be mine, yours, his/hers, but rather ours, because the first is the soil for seeds of life for everyone, and the second is the instrument for giving life to what has been cultivated by the labor of all.) (Santos [1906] 1993, 37)

Carlos Ronquillo (1877–1941), a revolutionary and chronicler of the 1896 Philippine Revolution, wrote a somewhat obscure work titled Bagong Buhay: Ang mga Katutubong karapatan ng mga Manggagawa sa Harap ng Wagas na Matwid (New life [socialism]: The inherent rights of the worker in the light of pure reason) (1910), which expanded upon the various usages found in Santos’s novel. One notices in its very title how the meanings of the words katwiran, matwid, and karapatan have been clarified to attain their more contemporary meanings. Katwiran and matwid now pertain to razon (reason) in all of its usages in Ronquillo’s book so that “wagas na matwid” now attains a kind of allusion to Kantian “pure reason” (reine Vernunft). On the other hand, karapatan—having completely superseded the earlier usage of katwiran—is now definitively equated with “rights.” Ronquillo speaks of “katutubong karapatan ng tao” (inherent rights of human beings) and “katutubong karapatan ng mga manggagawa” (workers’ inherent rights). Three basic rights are mentioned: (1) “katutubong karapatan sa buhay” (inherent right to life), which subsumes “karapatan sa hanapbuhay” (right to work); (2) “karapatan sa karangalan” (right to dignity); and (3) “karapatan sa kalayaan” (right to freedom). According to Ronquillo, to violate these rights would be “labag sa karapatan” (contrary to rights). This may be the first time that this very contemporary idiom would appear in the materials used for this study. “Walang karapatan” (having no right), also a popular contemporary idiom, appears here perhaps for the first time in print. According to Ronquillo, the “katutubong karapatan” (native rights) are as follows:

. . . mga karapatang kasamasama na natin paglabas sa maliwanag at mga karapatang di maiwawalay kailan man ni ng tunay na nag-aangkin, palibhasa’y pawang likas at angkin ng buhay natin, sapul pa sa tiyan ng nagkakandong na ina. Iyan ang mga karapatang di mangyayaring bawiin, ni pigilin, paris ng mga karapatang likha ng mga bulaang.

(. . . the rights [karapatan] which accompany us as we come out into the world and the rights which cannot ever be separated even by those who possess it, because these are natural [likas] and a part of our life, even as we were still in the womb of our mothers. These are the rights which cannot be taken away, unlike the rights fabricated by pretenders.) (Ronquillo 1910, 8)

The above quotation attempts to translate both “droits naturels” (natural rights) and “droits inalienables” (inalienable rights). For the first time in Tagalog, karapatan is described as being likas (natural) to pagkatao (being human). This is more explicitly formulated in another part of Ronquillo’s work which contains the phrase “karapatang likas sa pagkatao” (a right which is in the nature of being human). The phrase “droits naturels” (natural rights) thus finally finds an equivalent as the Tagalog “karapatang likas.” Such usages of likas have in the meantime become quite common in contemporary Filipino. Furthermore, the idea of “inalienable” is expressed in the above passage as “mga karapatang di maiwawalay kailan man ni ng tunay na nag-aangkin” (rights which can never be separated even by those who rightly possess them). Though rather long-winded, it accurately explains what inalienability means for the possessors of rights who cannot divest themselves of these rights even by means of their own consent to self-enslavement through outwardly legal contracts.

Moving further on, Soriano’s Tagalog translation of Malatesta’s work from 1913 demonstrates that karapatan had already definitively superseded katwiran as the most frequently used equivalent for “rights.” For instance, the sentence “ang lahat ng tao’y may karapatan sa mga pinakapangulong bagay sa pamumuhay, gayon din sa mga kasangkapang kailangan natin sa paggawa” (all human beings have the right to the main necessities of life as well as the instruments we need for production) (Malatesta 1913, 25) can be compared to the Spanish translation: “cada uno tiene derecho a las primeras materias, y a los instrumentos de trabajo” (each one has the right to the raw materials and to the instruments of labor). The Tagalog translation obviously diverges from the Spanish version “materia prima” (raw materials) as “pinakapangulong bagay sa pamumuhay” (main necessities of life), but the meaning of karapatan as “right” is nevertheless evident.

After a span of around three decades from the publication of Santos’s Banaag at Sikat, Crisanto Evangelista (1888–1942), the first general secretary of the PKP (PKP-1930), wrote Patnubay sa Kalayaan at Kapayapaan (1941), which can serve as a useful record for the further development of the Tagalog word karapatan (Richardson 2011, 21). What is striking with Evangelista’s usages of karapatan is the shift of emphasis toward civil rights and liberties which still reflected the anti-fascist policies of the Popular Front on an international level (Pagkakaisa ng Bayan). This orientation can be seen in the following examples: “karapatang demokratiko” (democratic rights), “karapatan sa pagkamamamayan” (citizenship rights), “karapatang bumoto” (right to vote), “karapatan sa paghalal” (right to elect), “malayang karapatan sa pagsasapi-sapi” (right to free association), “malayang karapatan sa pagpupulong” (right to hold meetings), “karapatang makapagpahayag” (right to free expression). In Evangelista’s rights idiom, in order for these rights to be recognized (“kilalanin ang karapatan”), the people must collectively stand up for (“naninindigan sa karapatan”) and demand their rights (“pag-uusig ng karapatan”). Quite importantly, Evangelista’s essay contains the phrase “di-malalabag na karapatan sa pagkatao” (the inviolable right to being human). Pagkatao therefore does not here only guarantee the possession of rights but has now itself become a right. This phrase is equivalent to the human right to have rights. Finally, in consonance with the burgeoning anticolonial struggles of the time in Asia and Africa and in anticipation of their explosion in the postwar era, Evangelista also called for the collective, national right known as the “karapatan sa sariling pagpapasya” (right to self-determination) (Lenin 1964; Prashad 2020).