Advance Publication

Accepted: June 20, 2024

Published online: November 10 2025

Contents>> Vol. 14, No. 3

The People That Dwell on the Heights: The Pantaron Highlands of Southern Mindanao from the Nineteenth to the Early Twentieth Centuries

Andrea Malaya M. Ragragio* and Myfel D. Paluga**

*Department of Social Sciences, College of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of the Philippines Mindanao, Mintal, Tugbok District, Mindanao, Davao del Sur 8022, Philippines; Cultural Anthropology and Development Sociology, Universiteit Leiden Faculteit Sociale Wetenschappen, Pieter de la Court Building Wassenaarseweg 52, Leiden, South Holland 2300 RB, Netherlands

Corresponding author’s e-mails: amragragio[at]up.edu.ph; a.m.m.ragragio[at]fsw.leidenuniv.nl

![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5758-0307

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5758-0307

**Department of Social Sciences, College of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of the Philippines Mindanao, Mintal, Tugbok District, Mindanao, Davao del Sur 8022, Philippines; Cultural Anthropology and Development Sociology, Universiteit Leiden Faculteit Sociale Wetenschappen, Pieter de la Court Building Wassenaarseweg 52, Leiden, South Holland 2300 RB, Netherlands

e-mails: mdpaluga[at]up.edu.ph; m.d.paluga[at]fsw.leidenuniv.nl

![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0031-7839

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0031-7839

DOI: 10.20495/seas.25006

Browse “Advance online publication” version

This study reconstructs life in the southern Mindanao highlands from the midnineteenth century to the early twentieth century from historical accounts and contemporary ethnographic observations. It explores the evolving relationships among highland groups, referred to as “atas,” “ata-as,” or “ataas,” and other communities in the region. Such terms, later recognized officially as “Ata,” were used by non-highlanders to denote highland communities based on their geographical location, while they self-identified according to upland river configurations.

This study reveals that various named groups inhabited a three-tier highland/inland-to-lowland/coastal axis, engaging in both cooperative and adversarial interactions, such as trading and slave-raiding. By the time Spanish authorities established the Davao pueblo, the highlands were already a dynamic, inhabited space, independent of colonial influence. The Pantaron highlands emerged because of long-term, cumulative decisions by these communities, reflecting a complex history that predates colonial dynamics. The findings challenge colonial-centric narratives and emphasize highlander agency in shaping their social and geographical landscape.

Keywords: highlands, colonialism, slavery, Ata, Pantaron Manobo, Davao(Mindanao), indigenous peoples, ethnohistory

Introduction

“We have always been in the Pantaron,” is the oft-repeated answer of Manobo elders to questions about the old days. As far as they can remember, they, their parents, their parents’ parents, and so forth have lived on the mountain range. Prior to the implementation of formalized education, younger generations gained historical knowledge through epics and stories of heroes venturing across these highlands. Although the Manobo also have origin stories, or accounts of the creation of the world, these highland-focused narratives more intensely capture their excitement and imagination; everyday conversations are peppered with references to characters and places from them. During our year-long ethnographic fieldwork (from 2018 to 2019) with Manobo seeking shelter at the United Church of Christ in the Philippines (UCCP) Haran evacuation center in Davao City, they expressed the desire to return to their highland homes daily.

Home, and the ancestral domain, of our Manobo collaborators is the southern Pantaron Mountain Range in southern Mindanao, Philippines. Their communities are oriented toward the headwaters of the Talomo and Simong rivers (tributaries of the Libuganon River in Talaingod town, Davao del Norte Province), the upstream Kapalong and Libuganon rivers, and the Salug River (the upstream portion of what is called Davao River downstream, in the Paquibato area). Both the Libuganon and Davao rivers flow toward and empty into the Davao Gulf. While today “Ata-Manobo” is the official, state-recognized ethnonym of indigenous peoples in these upland areas, because they self-identify as Manobo from the Pantaron Range, we use “Pantaron Manobo” to refer to them instead.1)

This paper presents a historical reconstruction of the formation of the highland communities to which our collaborators belong. Like other Austronesian language-speaking groups in Maritime Southeast Asia and beyond, their distant ancestors must have first arrived, and lived, in coastal areas (Solheim et al. 1979). Their lexicon reflects this past: Manobo epics refer to a balangoy, certainly related to the central Philippine balangay described as a large, sea-going, edge-pegged boat (Scott 1994). But while the term and its broad meaning have been retained, elders today cannot fully describe the balangoy, saying only that it is “something that you can ride.”

Thus, our study explores the historical cogency of our elderly interlocutors’ claim that their people have always been in the Pantaron highlands. What has been the status of the highlands as both a dwelling place and identity marker throughout history? How did the different groups of people who lived in the southern Pantaron and contiguous Davao areas construe one another? What relationships did they have, and what transformations—if any—did these undergo? These questions direct us to a central query that has yet to be comprehensively investigated by studies on southern Mindanao: is highland dwelling across the Pantaron Range a reaction to colonization in the Davao region, or does it predate colonial presence in the area?2)

Challenges and Sources

Previous attempts to write a history of the southern Mindanao highlands are limited. Gloria and Magpayo (1997) and Bajo (2004) simply list the occurrences of “Ata,” “Atas,” and other related terms in the historical record, barely interrogating the category and its usages through time. Industan’s (1993) unpublished dissertation makes some progress in this regard, but his unpacking of “Ata” is largely confined to his study’s ethnographic present. Tiu’s work (2005, 48–52) explicitly problematizes the origins of “Ata,” but is bogged down by outdated approaches that use racialized, phenotypic impressions and blood quantum descriptors (103, 111).

A significant weakness of simply listing “Ata,” “Atas,” and other related terms in the historical record is that some of these communities do not fully embrace the term “Ata” as self-referential (see Bajo 2004, 26 and Masinaring 2014, 1–2 for similar observations). Such listing also overlooks the meaning of “Ata” and how its usage has changed through time. Indeed, the term itself has varied: during the nineteenth century, different spellings (“atas,” “ata-as” or “ataas”) were used, while usage as formal appellation (such as “the Atas” or “the Ata”) only began in the more ethnographically inclined literature of the early twentieth century.

The label of “Ata” (and other associated terms)3) is therefore not the narrow object of this study, but it is carefully analyzed to track the historicization of the people to whom it has been applied, to better understand their dynamics with differently named groups, and to forward insights about possible implications to present-day cultural and identity distinctions.

We also examine the place names associated with the Pantaron Manobo, such as the once-pueblo and now-city of Davao and the names of the rivers that flow from the uplands to the coast. This is important because 1) place names are directly related to the status and character of the highlands as a lived space, and 2) these names (and the geographical areas to which they refer) are more consistent through time.

This study draws from the same sources utilized by Industan (1993), Gloria and Magpayo (1997), Bajo (2004), and Tiu (2005). It is a small pool due to the relatively late establishment of a secure colonial foothold in southern Mindanao compared to other areas in the Philippines. The Davao area was not established as a pueblo with a consistent Spanish presence until after 1848, when Jose Cruz de Oyanguren’s colonizing expedition defeated the Moro chieftain Datu Bago, who controlled the mouth of the Davao River.4) This was more than two hundred years after most of the country—including north and northeastern Mindanao—had already been brought under colonial rule. Thus, while the mid-1800s onwards would be considered “late colonial” for the rest of the country, the integration of this part of Mindanao into the colonial order had only just begun. Therefore, sustained observations and systematic documentation in the Davao area were available only for the last 170 years or so.

The earliest body of work that can productively be used for historical reconstruction is the collected letters of the Jesuit order (Lynch 1956), first published from 1877 to 1895 as the Cartas de los Padres de la Compania de Jesus de la Mision de Filipinas. The Cartas were later translated by Arcilla (1998) into the six-volume Jesuit Missionary Letters from Mindanao; Volume 3 on Davao has been maximized for this study.5)

Establishing Davao as a Spanish settlement allowed European explorers to launch scientific expeditions from the pueblo; mountain ranges like the Pantaron and the country’s highest peak, Mt. Apo, attracted such endeavors (Bernad 2004). The published reports of the expeditions of French naturalist Joseph Montano and Davao governor Joaquin Rajal y Larre are notable. The transition from Spanish to American colonial rule at the turn of the twentieth century spurred another wave of Western exploration in the Davao Gulf area by writers with some degree of formal training in anthropology, namely, Fay-Cooper Cole, Laura Watson Benedict, and John Garvan.

The Reports of the Philippine Commission, or RPCs (published from 1900 to 1916), are a useful corpus with their preoccupation with cataloguing and classifying people, flora and fauna, and natural resources. While this reflected the interests of a newly reigning colonial authority, it also gives us a baseline from which to compare how these classified entities changed through time as the US consolidated its control over the Philippines. The RPCs also detail policies on “non-Christian tribes,” providing a view of the changing approaches of colonial management and their impacts on local groups.

Although these sources are associated with colonial bureaucracy and objectives, they can nevertheless be used with circumspection. William Henry Scott (1978, 174) likened such usage to looking through “cracks in the parchment curtain” to catch “fleeting glimpses of Filipinos and their reactions to [colonial] dominion.” With this approach, using such sources is not uncritically accepting what they convey. Rather, they are reevaluated using what Scott (1978, 182) calls “the principle of ‘incidental intelligence,’” recognizing that “unintentional and merely incidental” references to Filipinos “may be of greater historical revelation than what the authors wanted to say” (174, 181). In other words, tangential but important details may be productively gleaned from these sources for historical reconstruction.

Historical interpretation of these “fleeting glimpses” may be enriched in two additional ways. First is to pay attention not just to explicit instances wherein the highlanders are clearly referenced, but also to when they disappear. Absence can provide clues to actions, motivations, and overall conditions. Second is to reexamine the sources in light of insights derived from ethnographic collaborations with these highland communities. These collaborations include genealogical reconstruction and documentation of oral and ritual traditions, as well as conversations about highland space, their life in it, and how highlanders imagine their communities at varying scales. This is not just to remedy the colonial “taint” of historical (written) sources, but also to generate readings of highland historical experiences that are more resonant with Pantaron realities and our interlocutors’ understandings of their durable heritage. First, though, we review what has been recorded about the southern Mindanao highlands.

1 A Historical Reconstruction of the Highlands

1.1 “A Race of Infidels”: The Highlands in the Nineteenth Century

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, inhabitants of the Davao region highlands were referred to as “de los atas,” “grupo de atas,” “los ata-as,” and “grupo de ataas,” terms used by Visayan lowlanders to mean “those who live on the heights”6) (Rajal 1891, 123). According to Montano (1885, 170), “atas” and “ataas” were variations of the adjective dessus, or “above” in Malay and other Mindanao languages. Thus, in the Visayan usage at least, the term may have been first used as a simple description of where these groups resided and not an ethnonym.

The earliest written mention of Atas was in 1877 in a letter by the Jesuit Quirico Moré, who wrote “The tributary Libaganun [now the Libuganon], sufficiently deep, is inhabited, according to the Mandaya chief with whom I spoke, by 900 Mandayas, more than 4,000 Atas and as many Manguangas” (Arcilla 1998, 9). Four years later in 1881, Mateo Gisbert reported that “The Atas are plentiful along the tributaries of Tuganay [river]” and “the Mandaya settlement by Tuganay should serve as the door through which to extend the mission to the Atas” (Arcilla 1998, 43, 44).

These early references to Atas mark their close association with rivers. Both rivers mentioned here flow parallel to each other in what is now Tagum City (at that time a visita of Davao pueblo under the Jesuits), and empty into the Davao Gulf. The headwaters of both are in the Pantaron and, as Moré and Gisbert note, Atas and Mandaya communities live along them. It appears that some Mandaya villages were close enough to the lowlands that Gisbert was optimistic that they could mediate access to Atas areas farther upriver.

In an 1885 letter, the Jesuit Quirico Moré described what the Davao region was like at the time of Spanish conquest in 1848: “When Oyangúren came, the Moros . . . dominated the Mandayas, and collected tribute from all of them even from those [upriver] of Caraga, and were engaged in continual war with the Bilanes, Manobos and Atas”7) (Moré [1885] 1906, 197). This letter indicates the variety of distinct “tribes” present in and around Davao pueblo, and notes that several of them had antagonistic relations with the so-called Moro.

The expeditions of Joseph Montano and Joaquin Rajal y Larre in the 1880s yield more substantial information about the Atas. Their accounts are important because they document what the two men personally witnessed and observed. Thus, although they are still the products of the colonial milieu, helpful details for historical reconstruction can still be gleaned from them. For example, upon arriving at Davao pueblo in April 1880, Montano (1886, 202–203) classified the population he encountered into 1) “Bisaya Indians” (or Christian converts), 2) “Malay or Mohammedan Moros,” 3) “Chinese,” and 4) “infieles,” including “all the natives, of diverse races . . . occupying the interior of the island.” He identifies one group of infieles as the Atas, whom he describes this way:

The Bisayas designate at the same time, under the name of Atas, the Negritos whom I have met here only as slaves, and other tribes who live to the north-west of the Apo. These last belong to a high type; they have a fairly advanced social state; they are the only ones who do not fear to measure themselves with the Moros, to whom they have committed a hereditary hatred; their daring is often successful. (Montano 1886, 221)

In an earlier report, he gives a similar definition of Atas:

This name, which in the Philippines designates populations of such diverse races, is given, in southern Mindanao, to the Negritos who exist (or existed only a short time ago) in the interior, in the northwest of the gulf of Davao, and to some tribes of Indonesian race which inhabit the slope of the Apo volcano, in the same direction.

The Indonesian Atas present a superior type, especially the chiefs; these have aquiline noses, profuse beards, and tall stature.

These Atas tribes enjoy a well-deserved reputation for bravery; they are the only ones who are not afraid to pit themselves against the Moros, although they do not have more firearms than the others, and success often crowned their value. (Montano 1885, 77)

From these excerpts we learn that first, Atas was a term that Christianized Visayans used; this accords with our interlocutors’ assertion that it is not self-referential. Second, Atas was not applied to a single “race,” which, at that time, was often used to mean a physically distinguishable and mutually exclusive homogenous group. According to Montano, Atas applied to what he saw as both physically and socially distinct “Negritos” and “Indonesians,” the latter being “a superior type” with an “advanced social state” (presumably relative to the former “Negritos”). This “superiority” was marked by their courage to fight their traditional enemies, the Moros. Although Montano provides more information about the Atas than had been previously available, he does not elaborate the sources of this information. It is possible he learned from Christianized Visayans who explicitly used the term “Atas,” or from Bagobo and Mandaya people, with whom he interacted more.

Rajal, on the other hand, was able to visit Atas villages. Intent on finding a route connecting Davao pueblo to Misamis District in northern Mindanao, Rajal traversed the highlands once in mid-1881 and again in early 1882. In his Exploración del Territorio de Davao (Filipinas) (published in 1891), he narrates the first voyage in detail (including interactions with upland peoples) and provides a day-to-day itinerary of the second trip such that his passage can be plotted on a map (Map 1).

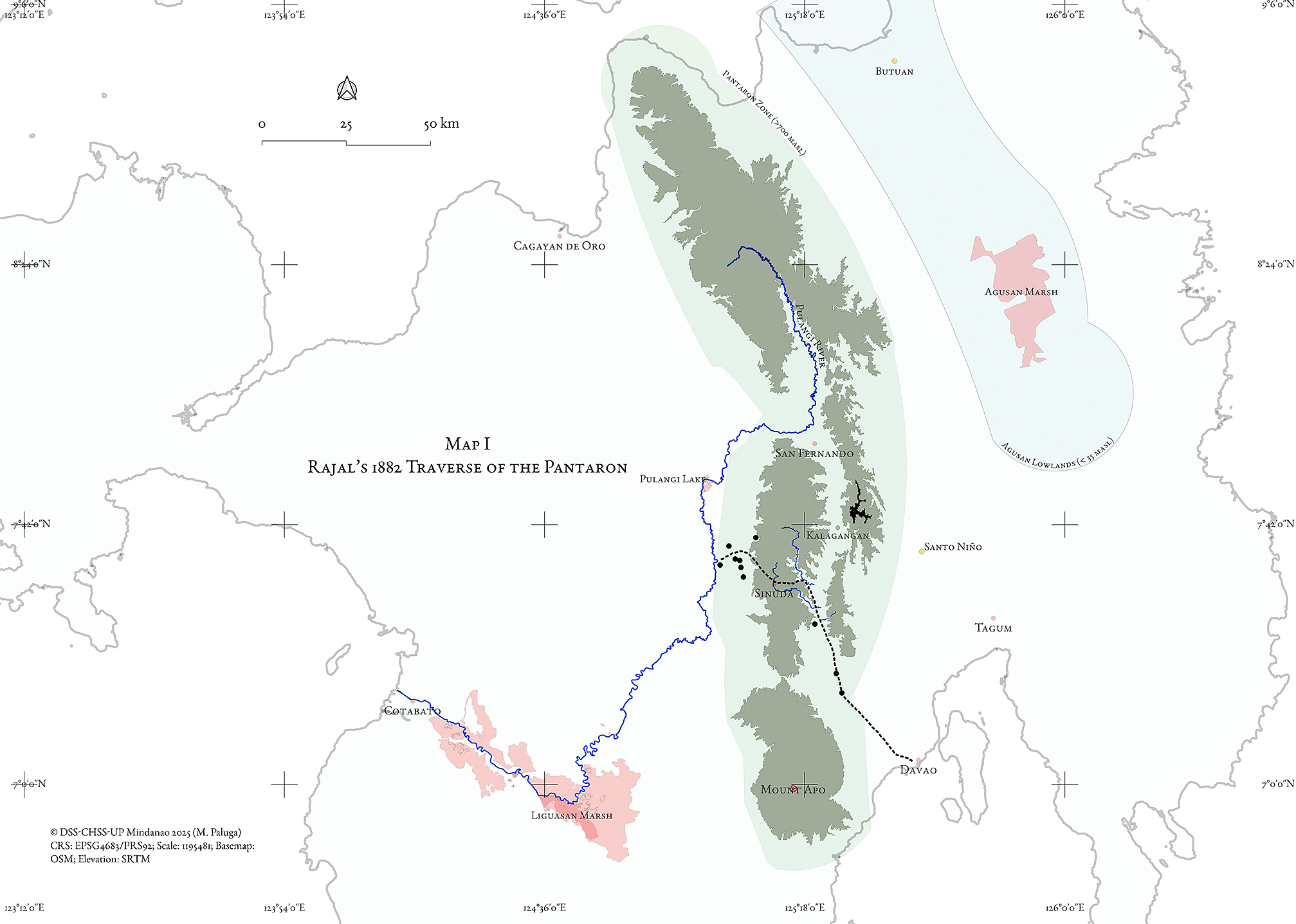

Map 1 Rajalʼs 1882 Traverse of the Pantaron Mountain Range with Elevations (Black circles mark current villages along Rajal’s party’s path.)

Rajal’s account is important for two reasons. First, as far as we know, his observations of the highland interior are the first to be published. This does not mean, however, that the interior was unknown. Indeed, Rajal was encouraged to find this northward route precisely because he was told that local people traversed it. His main guide was the son of a Visayan named Francisco Belmonte, who had, decades before, told Oyanguren that the crossing was possible. Belmonte described how “he had reached the nearby mountains inhabited by the so-called Atas” by hopping “from ranchería to ranchería, crossing the island by one of its greatest diameters . . .” (Rajal 1891, 117). Rajal’s account details various groups interacting and consciously living in a multi-cultural space; his guides were well-versed in the locations of named villages and the names of some of their leaders. In this “la cordillera central,” Rajal (1891, 10, 132, 142) notes that “it always turned out that internal communication could take place” (118).

The expedition’s first sign of Atas was a killing of a young girl belonging to the Giangan tribe. The dead girl’s father told Rajal that the killing had just been committed by manga-yaoa8) warriors, who launched sneak attacks either to capture slaves or to exact revenge against perpetrators of slave raids.9) Manga-yaoa killings were said to be done by all the “infidel” tribes (including the Giangan); it was alleged that this particular killing was committed by two Atas men who subsequently escaped inland. Rajal, diverting his route to pursue the killers, reaches what he records as two Atas villages, resulting in a very early description by a Westerner of such settlements.

The first village was “at the foot of the gigantic mountains that are close to the source of the Taumo [Talomo10)] river” (Rajal 1891, 122). On top of a hill was what he describes as a choza-palacio, or “palace-hut”:

The palace-hut was located in the center of an extensive caiñguin [swidden field] planted with rice and corn. In its vicinity, under a small shed, there were two grotesque wooden figures, crudely carved and dressed in rags, representing a man and a woman; they were the tutelary gods of that family, and they were also the first material representation of the divinity that was offered to our sight in those regions. At their feet were plates containing fruits and rice, offerings of piety dedicated to them with the first of the fruits that they daily collected for their sustenance. We wanted to inquire about their origin, their name, and the beneficial influence attributed to them, and from their imperfect explanations we deduced the age of their cult, which according to them represented a marriage from heaven called Diuata, to whom they attributed all happy or unfortunate events. (Rajal 1891, 123–124)

Two days later, Rajal and his party arrive at the second Atas village, Sua-uan, where the suspects supposedly lived. They find it abandoned and are told that the inhabitants likely fled. They stay in “a house located on the top of a bare mountain, from where a picturesque panorama was offered,” which Rajal describes like this:

A multitude of more or less high and conical mountains, whose ensemble resembled a tray full of sorbets, surrounded us, making out others of greater height in the distance. On its cusps and on some slopes, some groups of houses were scattered, and in the same way some clearings in the forest, which were just as many fields for planting. (Rajal 1891, 131)

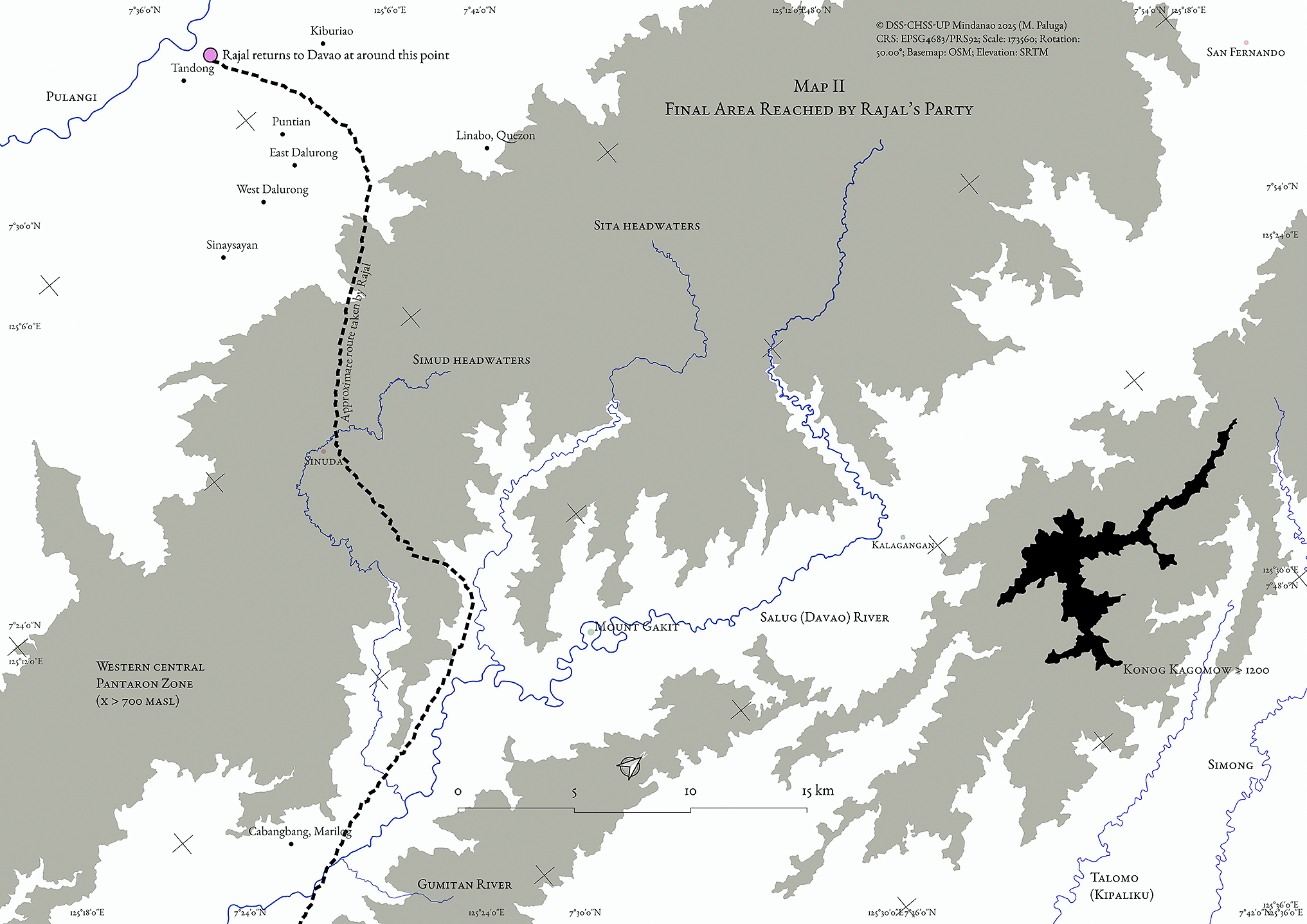

The second significance of Rajal’s account is how it makes both moving upward into higher elevations and moving through the lived space of the highlands phenomenologically palpable. The route he took was made possible by countless other previous journeys by locals, and it is a route that remains relevant today. For example, the route Rajal took from Tamugan to Sinuda via the Davao River is one that Pantaron Manobo are still very familiar with; the modern Bukidnon-Davao highway also approximates this route. In Rajal’s time, this route was dotted with villages identified as settlements of “Giangas,” “Manguangas,” and Atas. At the farthest point up/inland reached by the 1882 expedition, where the Sita River (a Davao River tributary) and the Pulangi River flow closest to each other, Rajal (1891, 141) notes no less than five Atas villages in proximity to each other: Mantavi, Matunda, Dal-laon, Sebugay, and Linabo (Map 2). Rajal was able to index on to the party’s (colonial) mapping the individual significance of, and links between, the Pulangi and Davao rivers (from which Maguindanao and Davao, respectively, are easily accessible)—which is palpable only at the high elevations of the Pantaron.

Map 2 Final Area Reached by Rajal’s Party, between the Pulangi and Sita Rivers, Where Five Atas Villages (including Linabo) Were Recorded (Other current villages also indicated.)

Learning from Rajal’s expeditions, by May 1884 Mateo Gisbert confidently reported to the Mission Superior a comprehensive listing of Davao non-Christian groups for conversion and resettlement, with Atas occupying the vast upland territory of southern and central Mindanao: “With the expedition dispatched from Davao to Misamis, Mr. Rajal proved an inland route can be easily opened to facilitate the relocation of unbaptized tribes. Even if only the Atas are converted, the government will have won a new province in Mindanao” (Arcilla 1998, 87).

However, two years later, missionary work remained slow. In February 1886, Gisbert ([1886] 1906, 242–243) repeats that “The Atás are another race of wild and savage heathens who live in the interior . . . It is the least known race, but it is believed with foundation, to be the most numerous, aggregating not less than twenty-five thousand souls.” Nevertheless, by this time Gisbert had been to visit a village himself:

Only the rancheria of Dato Lasiá, which is the nearest, has been visited as yet. They speak their own tongue. I have baptized a few Atás, by making myself understood in Visayan or Bagobo. On that day that the Atás hear a father missionary speak their language, I have no doubt their conversion. (Gisbert [1886] 1906, 242–243)

Gisbert’s reference to “their own tongue” perhaps indicates distinct groupings better than any impressionistic criteria. He also noted that while the Atas language is distinct from Visayan and Bagobo, the Atas could understand both. Montano’s Rapport (1885) provides a word list that includes some Atas terms, as distinguished from Malay, Bisaya, Bagobo, and five other Mindanao languages.

How well the persons being baptized understood the rite’s meaning however, is an entirely different question. Neither Dato Lasiá nor his rancheria are mentioned again in the Davao Cartas. Two years later in 1888, Gisbert reports that the people were as “wild” as ever:

Unbaptized Atas, Bagobos, Bilaans, Giangas, Mandayas, Manobos, and Tagakaolos with their numerous progeny fill the entire district [of Davao] and have known hardly any other civilization than that of the Chinese and the other retailers who have gone to their ranches and generally are usually more immoral and godless than the mountaineers themselves. (Arcilla 1998, 173)

1.2 “Steeped in Slavery”: The Impacts of Slave-raiding

An oft-repeated proof that Mindanao’s inhabitants were “wild” was the practice of slavery and its associated cycle of violence. Specific highland groups, including Atas, were targeted by Mandaya raiders who, occupying the intermediate ground between highland and lowland elevations, were able to raid the upland interiors and pass their captives to Moro slave traders on the coast. These captives were then sold to people living in Davao, including Christian Visayans and Chinese tradespeople (Montano 1886, 216 and Bernad 2004, 238–239). The flow of slaves was always from highland to lowland, not the other way around.

In an 1892 letter, the Jesuit Saturnino Urios describes a slavery supply-chain from the highlands and to the lowlands:

What trouble gathering these Mandayas is! They come armed to the teeth, fearful of the Atas with whom they are in constant warfare.

[But] the Mandayas have no reason to complain about the harm done by the Atas. These, as their name signifies, are upland people, gentle, picking up arms only to defend themselves and avenge the injuries caused them by the Mandayas. The latter are quite shrewd. Through the years, they have had much contact with Moros and old Christians. They are the ones who, instigated by the Moros, supply slaves to whoever asks for them. The system is, those from Davao order slaves from the Moros; who egg the Mandayas on to procure them. This they do by killing and kidnapping the Atas. This is the cause of the state of chronic warfare between the two groups. The former provoke the latter, who naturally must avenge the wrongs unjustly done them. They will not allow themselves to be killed with impunity, for one protects one’s own life.

Fr. Superior, this region of Davao is so steeped in slavery, one’s heart breaks over the manner by which the unbaptized natives are treated . . . The supply line starts from the unbaptized Tagakaolos, Atas, Mangulangas of Salug and Libaganon; the Manobos of the Kulaman coast and the opposite shore of the gulf until Pundagitan; and the Bilaans dwelling on the peaks of the southwestern range down to Glan. (Arcilla 1998, 283–285)

According to the Cartas, slavery had been pervasive for at least as long as Spanish presence in the Davao area (recall Moré’s description of Moro dominance at the time of Oyanguren’s arrival in 1848). In the latter half of the nineteenth century, the heightened vigilance of Spanish forces against the raiding of Christianized communities in Luzon and the Visayas resulted in the intensification of slave-sourcing from the interior of Mindanao (Ileto 2007, 38–42), transforming nearby Sarangani Bay into a major slave market (Hayase 2007, 140). This period also coincided with the latter stage of Iranun and Samal Balangingi dominance in slaving operations (Warren 1981; 2003). In Davao pueblo itself there was a brisk demand for slaves. As Urios complained, “Poor or rich, old and new Christians from Davao and the other settlements own slaves purchased or as payment for the marriage of others. One finds slaves in the farms, in the houses, everywhere” (Arcilla 1998, 284).

The “other settlements” Urios writes about were of so-called pagan tribes, who also procured slaves for human sacrifice. Montano (1886, 216, italics in original) similarly observed:

A few rare settlers, Indian Bisayas . . . it is sad to report, have taken the manners [of the infieles]; like them they have slaves and seem very surprised at our observations on this subject. “But señor,” said one of them, “all our neighbors have slaves; if I did not have one, I would no longer be respected, and soon I would be captured myself, exchanged for some platos [Chinese porcelain] and taken to all the devils beyond the [Mount] Apo.”

The “devils beyond Apo” here refer to the same “pagan” tribes in the vicinity of Mount Apo, who ritually killed enslaved people. Slaves could therefore also be acquired at various points along the highland-to-lowland supply chain. In these raiding dynamics, membership in named groups designated who were the main slave raiders and who were most vulnerable to these raids, and where they were located. Mandaya raiders did not capture and enslave fellow Mandaya, for example. Also, as far as can be inferred, retaliatory attacks by Atas were only directed towards non-Atas. Slave-raiding may thus have contributed both to the consolidation of previously existing groupings into named entities, and to how external observers (like missionaries) perceived them. For example, the highland Atas were considered pitiful victims, but at the same time, warlike and ready to defend themselves.

Violent incidents attributed to slave raiding were documented throughout the 1880s up to the 1890s. But in this later decade, Jesuit missionaries and tribal representatives steadily held more joint meetings wherein they discussed protection from attacks and resettlement (including the 1892 meeting that Urios writes about). The Jesuits seized this opportunity. In November of 1895, they reported the first baptisms of people identified as Atas, in the lowland settlements of Astorga and Malalag, trumpeting it as a breakthrough. Father Jaime Estrada wrote that “In God’s mercy, the fruit went beyond expectations. There were about 500 baptisms of Tagakaolos, Kalagans, and a majority of Bagobos, not excluding a number of Atas, till now the most marginalized and closed race” (Arcilla 1998, 475).

Interestingly, the highlanders had been deemed uncontactable until March of that same year, when Urios wrote:

The upper slopes of the Mount Apo mountain range and the other side are full of pagans who, since they live there, are called “Atas.” Wild and recalcitrant in the face of civilization, they prefer being deprived of the conveniences and benefits of trade and contact with others to leaving their hideouts. (Arcilla 1998, 432)

But the increasing frequency of tribal conferences must have given Urios hope, because he continues: “I say we are closer to them [Atas] than before” (Arcilla 1998, 432). Subsequent events seemed to prove Urios correct, because soon after the baptisms in Astorga and Malalag, the Jesuits report—for the first time—the establishment of a settlement that included people identified as Atas. In January 1896, Urios writes: “A new resettlement of Atas and Giangas is forming above Belen [along the Davao River]” (Arcilla 1998, 489). The following month, more people identified as Atas were baptized and re-settled. In May, Father Juan Llopart wrote that “a commission of [Atas]” in Mati, east of Davao, were “desirous of forming a settlement” (Arcilla 1998, 503).

This movement towards lowland settlements of highland inhabitants opting into the Jesuit offer of protection continued until 1896. But the Philippine Revolution against Spain breaks out in August of that year, and the Jesuits are eventually recalled to Manila in 1899. This halted their work just when their mission seemed to be reaching highlanders, some of whom agreed to resettlement alongside Giangan converts. Recall that the Giangan were vulnerable to Ata attacks (as Rajal documented); a community integrating both may have been considered a positive step towards peace and order by the Jesuits. However, the transition to American colonial rule stopped these developments.

1.3 “An Entirely Unknown Tribe”: From Ethnographic Entity to Outlaws

After successfully occupying the Philippines, American authorities and scholars produced the Philippine Commission reports (RPCs) and various academic monographs. The former body of work was meant to facilitate colonial rule and was thus more focused on bureaucratic policies, while the latter group of works—though still suffering from the scientific limitations of the time—documented ethnographic observations and addressed anthropological questions about cultural change and colonial impacts. These works heavily referenced publications of the previous century, specifically the Cartas, Montano, and Rajal, and adopted views deemed useful in naming, describing, and classifying the local inhabitants of the Philippines.

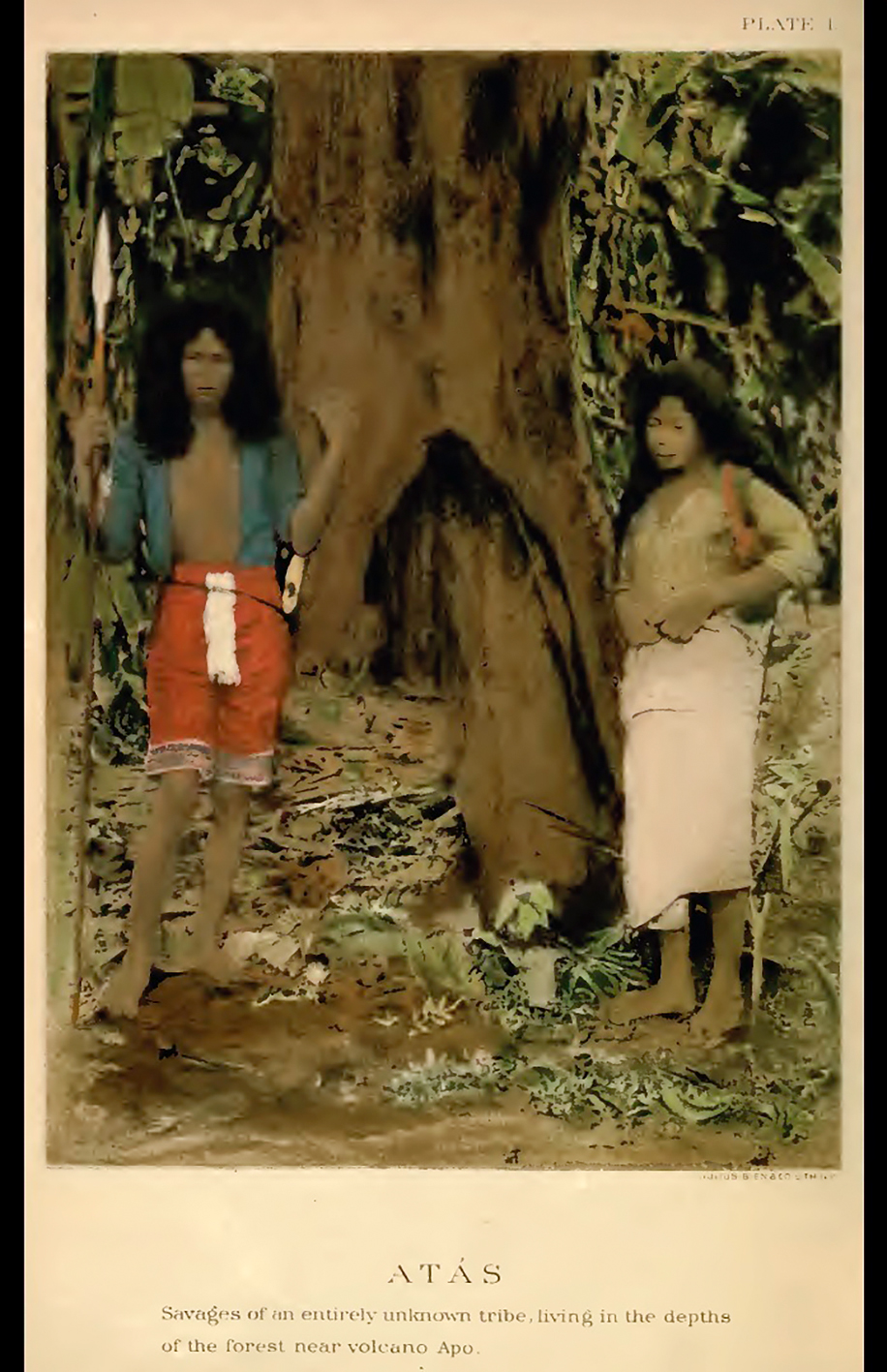

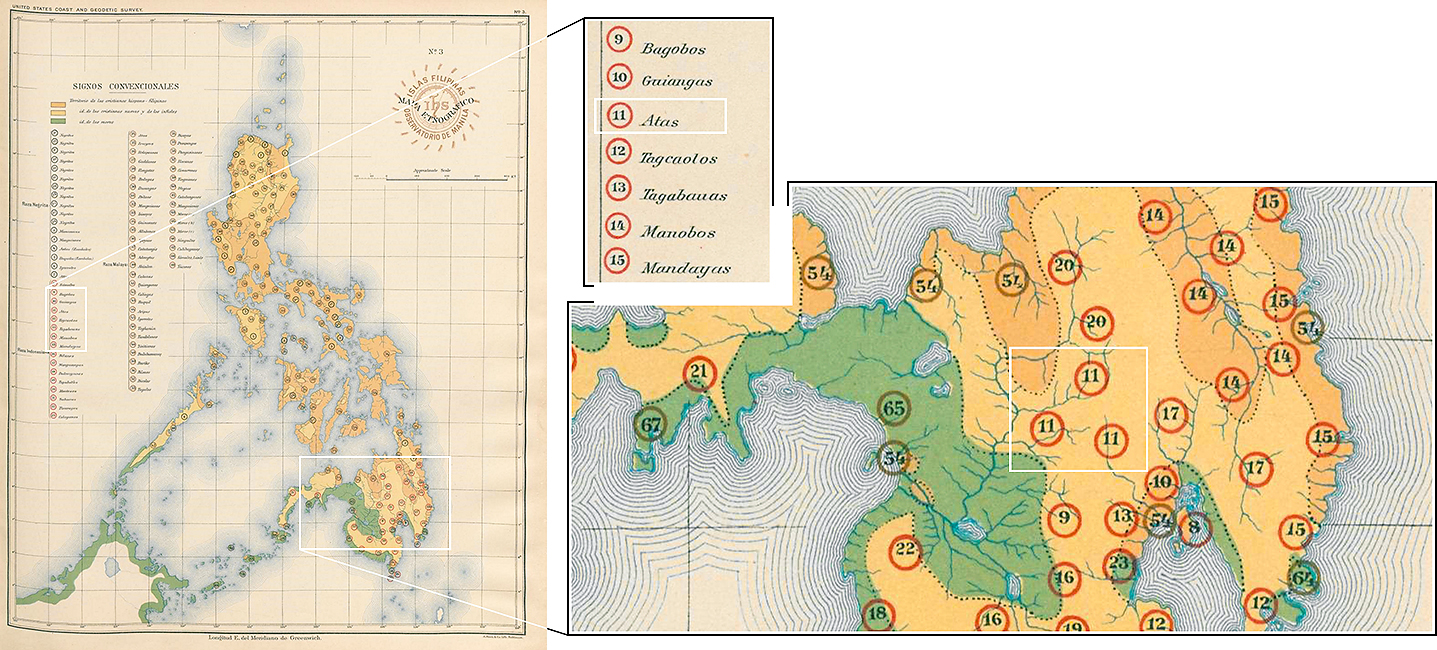

In the case of those living in the Davao highlands, the term “Atas” was retained while “ataas” and “ata-as” were not. In the more classification-focused documentation of American authorities, “Atas” began to shift from a label describing upland habitation to a more formalized ethnonym and tribal classification, as evidenced by Volume III of the RPC from 1901 (see Fig. 1). The latest iteration of the term Atas as a tribal ethnonym (and the photo in Fig. 1) can also be considered emblematic of the perceived diversity of tribal groups in the Philippines, which the American colonial administration was preparing itself to govern. There was renewed interest in Montano’s discussions about the “race” of Atas (Philippine Commission 1900, 13–14), and the inability to classify the Atas into a neatly defined “racial category” was touted as raising “one of the most interesting problems in ethnology” (Philippine Commission 1903, 680).

Fig. 1 Frontispiece of Volume III of the 1901 Report of the Philippine Commission describing “Atás” as “Savages of an Entirely Unknown Tribe”

American authorities were preoccupied with neatly defining the population into groups to better manage people through the establishment of Tribal Wards. On paper, the Tribal Wards were supposed to consist of “a single race or a homogenous division thereof” with a government-assigned headman who was a member and recognized leader of that group (Philippine Commission 1907a, 369). However, this did not always work in practice (Hayase 2007, 172–174). A single Ward could include members from different named groups, and the headman may be an American. The Wards were formed primarily to integrate the locals into the American capitalist economy by imposing taxes and turning them into wage laborers on American-run plantations. The colonial government considered wage work and permanent settlement, not maintaining or supporting local customs or leadership formations, essential to civilizing the local population.

The Philippine Commission report on the year 1905 stated that the four wards of “Bagobo,” “Giangas,” “Mandaya,” and “Moro” had been established, with mention of Atas as “unorganized” under the Ward system (Philippine Commission 1906, 347–348). The report did list thirty Ata inhabitants in its population census of Davao pueblo, but without further elaboration.

Although Ata and Tagacaolo were added to the list of established Tribal Wards in 1906 (Philippine Commission 1907a, 369), even the RPCs could not gloss over the policy’s poor implementation, acknowledging that most (including the Ata Tribal Ward) were “practically wards only in name” (Philippine Commission 1907a, 384). Just one year later (in 1907), the Ata Tribal Ward disappears from the list of seven Tribal Wards for Davao and the Ata revert to an entity shrouded in mystery, a group whose “exact number” and “exact whereabouts” in the “lofty mountain ranges” is “unknown” (Philippine Commission 1908, 386–387). The Ata seem to be slipping away from the colonial authorities’ information-gathering and governing grasp.

From 1908 onwards, there are no more substantive mentions of the group called Ata in the RPCs (which were published until 1916). A factor that could have led to this was a change in American policy towards plantation labor. By 1909, the colonial government had shifted from harnessing local labor from the Tribal Wards to recruiting external laborers from other provinces (particularly Christianized areas). The experiment to “civilize” local tribes via the plantations was largely a failure: as Hayase (1985; 2007) notes, only Bagobo communities were relatively successfully integrated into the plantation economy. The Tribal Ward system officially ended with the establishment of the US Department of Mindanao and Sulu in 1914 (Hayase 2007, 152).

The last two specific mentions of persons identified as Ata in the RPCs are from reports of the Philippine Constabulary (the American-established, anti-insurgency police force). In 1908, an Ata individual was arrested in a skirmish in “Tugaya” (possibly Tudaya in what is now Davao del Sur Province) and an Ata individual escaped constabulary custody (it is unclear from the report if these were separate incidents) (Philippine Commission 1909, 373). Finally, the last mention of Atas in the RPCs was in 1915, which noted that “a small band of about 20 Atas living on the upper Davao and Lasanga [Lasang] Rivers [has] caused some trouble from time to time” (Philippine Commission 1916, 136).

The term “Atas” and “Ata” in the RPCs thus begins as the marker of an ethnographic entity and a delineated tribal group to be organized into a Tribal Ward, but when this attempt fails and the plantations are up and running, documenting recalcitrant highlanders no longer appears to be worthwhile for the colonial authorities. As the Philippine Commission winds down, the Atas are finally mentioned merely as interior-dwelling, troublesome bands that are more the concern of law enforcement than of benevolent governance.

1.4 “Wild Tribes”: Highlanders in Early Ethnographic Accounts

Moving into the 1910s, while the Ata highlanders gradually recede from the view of official colonial government documentation, there are indicators of their continued presence and interaction with other local groups, which seem little disturbed by the shifts of the previous decade.

As discussed above, an important phenomenon connecting the lowlands and highlands was slave raiding and revenge killings. Reverberations of this were still apparent during the colonial transition. American anthropologist Laura Benedict’s pioneering study of Bagobo society (published in 1916 but based upon fieldwork in 1906) includes a description of a customary dance called Bulayan that is supposed “to express fear of the Atas” (Benedict 1916, 86). This is likely a throwback to the revenge raids of the past: recall that Bagobo people had participated in slave-raiding both as raiders and as people who ritually sacrificed enslaved persons. They thus may have been targets of revenge killings in the same way that (as the Jesuits noted) Mandaya and Ata people were embroiled in revenge-driven conflicts.

Being fearful of Atas notwithstanding, when a young man named Uan explained Bagobo deities to Benedict, he said, “Diwata are good manobo who live in the sky. They protect Bagobo, Americans, Kulaman, Tagakaola, Kalagan, Ata—not the Moro; Moro are bad people” (Benedict 1916, 29). Although Benedict does not mention it, the explicit exclusion of Moro people (and perhaps the implicit exclusion of the Mandaya middlemen) as “bad” and not under the protection of the Diwata11) could be additional proof of highlander enmity towards the main instigators of the slave trade, who lived closer to the coast.

Although Bagobo communities raided for and sacrificed slaves, this did not diminish the shared highland enmity towards the Moro. As mentioned above, slavery may have contributed to the consolidation of named groups in the Davao region according to the raiders and the raided. It should also be noted that the Bagobo term for deity, Diwata, is the same as the Diuata Rajal noted decades before. While not ironclad, this commonality in invoked spiritual figures also may have been a factor (at this historical point) in facilitating a sense of familiarity among these groups, further distinguishing them from the Islamized Moro.

Benign interactions between Ata and other groups also persisted. For example, Benedict (1916, 265, parentheses in original) notes that an “Ubu (Ata)” tattoo practitioner was active in Bagobo communities. There was also trade. Edward C. Bolton, the American governor of the Davao district from 1903 to 1906, told Fay-Cooper Cole (1913, 163) that he once met a group of people who called themselves “Tugauanum,” spoke an “Ata” language, and carried “knives and hemp cloth” that must have come from “the west side of the Davao gulf region,” an area traditionally part of the Bagobo domain well-known for abaca (hemp) cloth weaving.

Cole also notes what he perceived were “close alliances” between Ata and other local but non-Ata groups. In particular, he writes: “in the region adjoining the Guianga they [the Ata] have intermarried with that people and have adopted many of their customs as well as dress” (Cole 1913, 162). Recall that just before the abrupt end of their missions, one of the last permanent settlements that the Jesuits established (in 1896) was one of Ata and Giangan along the Davao River. Could the people Cole encountered in the Guianga area (where the Davao River also flows through) be the highlanders who had settled closer to the pueblo to avoid being embroiled in slavery-related violence and had since adopted semi-lowland life? This reflects another possible historical development that has impacted highland-lowland dynamics in the Davao region: the permanent settlement of highlanders to the lowlands.

Settlement at lower elevations seemed to create new cultural cleavages in the Davao region. Dean C. Worcester notes how, among people identified as Agusan Manobo in eastern Mindanao, there were “really wild Manobos,” distinct from “Christianized Manobos” whom, he said, “seem a rather supine and spiritless lot” (Philippine Commission 1910, 125). Similar distinctions may remain salient in more recent times; in a 2011 interview with this paper’s second author, Datu Guibang Apoga, the well-known Pantaron leader and elder, observed that there were Manobo no na-Bisaja-on, or Visayan-like Manobo “who no longer do things the Manobo way.” Such observations reveal that the connectedness and mobility of people residing in this region continue to enable settlement choices and facilitate culture change in ways that echo the patterns of the early twentieth century.

Another case is significant for its possible direct connection to the contemporary communities of our interlocutors. A report from Misamis Province in the 1906 RPC details a request from a group of “Tigwahanos” (that is, people from the Tigwa River) regarding how they were governed:

These people are tree dwellers, tattooed with the design of a leaf, peaceful if well treated, and will assist rather than hinder any expeditions or explorations. These mountain people some time ago applied for some form of government among themselves, and that they be not subject to the government of Misamis Province. A recommendation was made to that effect, and that they be placed under the rules and laws of the Moro Province and an American stationed among them as a tribal ward chief. I understand, however, that they have been attached to Misamis Province. (Philippine Commission 1907b, 308)

The Tigwa people are included here because the Tigwa River headwaters are in the Pantaron Range. Moreover, a prominent extended family to which many of our long-time collaborators belong recalls ancestors from the Tigwa River who, some generations ago, crossed from the western side of the Pantaron to the east and then moved south, closer to Davao, finally stopping at the headwaters of the Talomo River, where they have stayed since. The timing of this movement, remembered by our interlocutors, generally corresponds to the excerpt above. Therefore, if colonial authorities saw fit to transfer their jurisdiction from Misamis to Moro Province (of which Davao was part), there may have been an associated southward movement by some members of the Tigwa community, although no Tigwa Tribal Ward seems to have ever been formed. What must be noted here is how such a group tried to initiate closer relations with non-local entities but ultimately remained in the highlands.

Highlanders were thus not averse to moving to or accessing the lowland, potentially subjecting themselves to new challenges and influences, and reassessing their options from there—it had happened before with the Jesuit-established settlements of 1896. Cole (1913, 164) confirms this flexibility and adaptability of the Atas: “They have been free borrowers from their neighbors in all respects, and hence we find them occupying all the steps from the nomad condition of the pygmy blacks to the highly specialized life of the Guianga” (emphasis added). Either as “nomadic” “pygmy blacks” or as adapters of the “specialized life of the Guianga,” the Ata eventually slipped under the radar of colonial monitoring: first, as they drew away and remained in the highlands, and second, as they integrated into life closer to the colonial center.

1.5 An Early Chronology of the Southern Mindanao Highlands

A chronology of highlanders (as Atas or other associated names) based upon the available sources is proposed here to summarize the historical data presented above. In the mid-1800s, Western observers such as missionaries were only able to track highlanders to the extent of generally noting names, settlement locations, and population estimates. This begins to change after 1) expeditions produce the first written eyewitness documentation of highland villages and peoples, and 2) slave-raiding-associated violence intensifies and some highlanders accept the Jesuit offer of protection by settling closer to Davao pueblo. At this point, the Atas become more trackable by Western actors.

The abrupt end to the Jesuit mission and the transition of the Philippines to a new colonial authority from 1899 to 1900 resets the information-gathering on the Atas. The Atas again become an “entirely unknown tribe,” suggesting a withdrawal from the inroads and overtures of the missions of the past century. The American colonial government tries to institute the Tribal Ward system, which is unsuccessful and is not revisited for the remainder of its rule.

The explicitly anthropological orientation of studies produced during the American colonial period prioritized classifying people to better manage them and were generally remiss in historicization. This had the effect of reifying Atas (and others) as a discrete and homogenous ethnic group, which has left its mark in the academic, civic, and popular imagination until today.

By the second decade of the twentieth century, the Atas again slip under the radar of colonial monitoring. In the 1910s, nothing is heard of them (in the written record) beyond some reported run-ins with the law. In the decades that follow and into the post-colonial era, their presence in official accounts remains elusive. In the comprehensive volume by the Human Relations Area Files (Lebar 1975), contributor Aram Yengoyan can only present an entry of about 600 words for the “Ata,” barely half of Cole’s three-page description published in 1913.

This gap in knowledge persists today, as reflected in the brevity of the information provided by the official website of the Philippine National Commission on Indigenous Peoples on the “Ata,” which is short enough to be quoted in full: “The Ata-Manobo of Davao del Norte, aboriginally called Ata, believed that they originated from Paquibato, Davao City. The Ancestral Domain of the Ata-Manobo covers portions of the Municipalities of Kapalong, san [sic] Isidro, Sto. Tomas and Talaingod” (NCIP 2020).

2 Towards a View of Highland Life Beyond Written Documents

The following discussion synthesizes the above gleanings, adding insights from ethnographic collaborations12) to respond to the limitations of Western historical sources to forward a comprehensive historical look at the southern Mindanao highlands and the Pantaron groups who call it home.

2.1 Named Groups along a Three-tiered Highland/Inland-Lowland/Coastal Axis

A variety of named groups existed in the Davao area at the advent of sustained written documentation, including the Mandaya, Bagobo, Giangan, Tagakaolo, and others. Western documenters did not invent these names, they were already in circulation by the time documentation began. While Western sources tended to lump these groups together under broad terms such as “infieles,” they still could not deny the ethnographic reality of these diverse named groups because the names proved useful in their daily operations and interactions with locals.

While discussing the origins of these names and the groups they represent is beyond this study’s scope, some inferences may be made as to what distinguished these groups from each other. One factor was language: Montano’s (1885) vocabulary tables present differences in dozens of lexical terms of various Mindanao groups (named as “Atas,” “Bilaan,” “Bagobo,” “Manobo,” “Samal,” and “Tagakaolo”).

Another factor was settlement patterns. The named groups were associated with corresponding named villages that locals could readily identify (as Rajal observed). These settlements, in turn, were distributed along a highland/inland-to-lowland/coastal axis. There were roughly three tiers along this axis, as reflected in early expeditions that mapped movement from lowland/coastal towards highland/inland areas. Davao pueblo, dominated by Christianized Visayan-language speakers, was at the lowest (coastal) elevation. Along the coast but outside Davao pueblo there were also Moro settlements. Meanwhile, groups referred to as Mandaya, Bagobo, Giangan settled a bit further inland and at middle elevations.

Those living at the highest elevations were designated as “Atas,” and this settlement pattern was consistently used to distinguish them from other peoples in the area. American anthropologist John Garvan succinctly summed up the description, originally from Montano, that the “Atás” were:

. . . a tribe of a superior type, of advanced culture, and of great reputation as warriors. They dwell on the northwestern slope of Mount Apo, hence their name Atás, hatáas, or atáas, being a very common word in Mindanao for “high.” They are, therefore, the people that dwell on the heights. (Garvan 1931, 5)

Western observers could not readily reach these “heights” without traversing middle elevations and interacting with the groups that occupied the intermediate space; indeed, the Jesuits recognized that such groups could help facilitate access farther into the interior. Those who occupied this middle range may have also served as buffer between coastal dwellers and those living at higher elevations.

2.2 Rivers, Naming, and Identity

Many places and geographical features in the highlands were also named and Westerners documented the contemporary names of rivers and mountains as they did with appellations of groups of people. But since rivers were indispensable for purposes of navigation,13) expeditions more consistently recorded river names than those of mountains or other features. Among the documented river names are “Libaganon,” “Taumo,” “Tamugan,” and “Tuganay,” which are known today as Libuganon, Talomo, Tamugan, and Tuganay, respectively. These names were recorded by missionaries, who mapped local groups for conversion (like the earliest mention of Atas by Moré in 1877), and by expeditions like Rajal’s (1891, 122), which first encountered the edges of an Ata village “at the foot of the gigantic mountains that are next to the source of the Taumo river.” Note that while Rajal records the name of the river, he does not name the “gigantic mountains.”14)

The names of rivers often served as identifiers of people, such as the “Tigwahanos” who requested self-governance in 1906. Another example is the trading “Tugauanum” whom Bolton met, about whom Garvan (1931, 4)—spelling it as “Tugawanon”—writes were “a people that lived at the headwaters of the River Libaganon on a tributary called Tugawan” and who speak “an Atas dialect.” We know that these upper Libuganon “Atas” of “Tugawan” were involved in slave-raiding activities because, as Garvan reports, “the Mandayas of Kati’il [Cateel] and Karaga [Caraga]” bought “Negrito slaves” from them. Garvan also reports that, according to persons he calls “Salug authorities,” “Libaganon” Manobos capture “Negrito” to sell to the “Debabaon” (Garvan 1931, 15, footnote 15). The “Salug” most probably refers to the present Saug River (in the New Corella and Asuncion areas), which links into the lower Libuganon River, near Tagum City.

Considering the candid manner by which these names were gathered, they are likely self-appellations. In a colonialism-centered study, Paredes (2013, 25) stresses that it was the “colonial-era observers [who] wished to be more precise” who used “a more specific locative label . . . based on the name of the closest identifiable . . . settlement or river tributary” in naming various groups the “Agusanon, Pulangion, Tagoloanon,” and others. But aside from noting that the capacity for fine-grained naming is shared by both colonizers and colonized, what should not be missed is the locally-rooted nature of these names: they are derived from specific tributaries, conjugated in accordance with pan-Manobo grammar (adding the affixes –on or –non), and appear in local epics, such as the character named Bato to Umayamon or “Young Man from Umayam River.” It is outsiders like Bolton and Garvan who insist that the highlanders be classified as “Atas.” Indeed, learning that the Tugawanons were “speaking an Atas dialect,” Garvan (1931, 4) concludes that “[p]erhaps the term Tugawanon is only a local name for a branch of the Atas tribe.”

This construal of the highlands remains relevant today because existing settlement organization and self-appellations are tied to rivers, with village structures built on the ridgetops that follow the river course (Fig. 2). This orientation towards rivers has generated a river-focused identity that links and distinguishes villages according to specific waterways. For example, our collaborators come from different villages along the Talomo, Salug, Simong, and Kapalong rivers. Depending on where they primarily reside, they readily call themselves (at present) Matigtalomo, Matigsalug, Matigsimong, and Matigkapalong respectively, with the prefix “Matig-” meaning “from.” Amongst themselves, “from-a-named-river” is a widely understood way of introducing oneself. In terms of scale, this river-oriented identity falls between family and village membership, and identity as “Manobo indigenous people” within the Philippine nation-state.

Fig. 2 A Pantaron Manobo Village along a Ridgetop in 2008 (Photo by MD Paluga)

That river systems, settlement, and identity are related to each other is plain enough to see in any research with various ethnolinguistic groups in Mindanao (see for example Paredes 2016, 335). But rather than surmise, as Paredes (2016, 339–340) does, that this relationship is metaphoric and expresses the sprawl and fluidity of identity, what should be stressed instead is the salience of its geographic-spatial tangibility. In other words, explicit river-based self-appellations substantiate these groups’ status as highlanders. The names Talomo, Salug, Tigwa, Kapalong, and even Garvan’s “Tugawan” refer specifically to tributaries at higher elevations that feed into bigger rivers, which, in the lowlands where they empty to the Davao Gulf, are named differently. The Talomo and Kapalong are tributaries of the Libuganon River and the Salug is the upstream name of the Davao River. Tigwa is a tributary of the Pulangi River, which flows west into Maguindanao Province. Self-identification that uses the names of highland tributaries and not the names of lower elevation rivers to which these tributaries connect is evidence that it is precisely the highland geographical space that is significant both as a dwelling place and a group name-marker.

This significance was apparent also to lowlanders like Christianized Visayans or Western observers, even if their interpretation of it was coarse-grained (i.e., the use of the singular term Atas to encompass varied highland communities). The ethnographic map in the Atlas of the Philippine Islands (Algue and The U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey 1900, 29), based upon maps prepared in 1899 by the Jesuit-run Manila Observatory, identifies three points in the interior as “Atas” areas (Fig. 3). These points correspond to the headwaters of three highland tributaries (the Tigwa, Salug, and Arakan) that have lent their names to a significant portion of Manobo-identifying people (the Tigwahano, Matigsalug, and Arakan Manobo) who still inhabit the area and who all consider the Pantaron as their ancestral domain. Since this map dates to 1899, this settlement configuration has thus prevailed for at least one hundred years, and likely longer than that, since these conditions were already established at the time of the earliest available records.

Fig. 3 Mapa Etnográfico (Ethnographic Map) from the Atlas of the Philippine Islands (The “Atas” areas in Central Mindanao are marked by the number 11.)

2.3 Interconnections

While these waterways served to name and geographically orient communities, they also threaded together various distinctly named groups along the described highland-lowland axis. The Jesuits recognized this early on (even if implicitly) as they built their communication networks via these rivers. The highlands that Rajal explored were also well-connected to coastal settlements via rivers: the area between the Pulangi and the Davao rivers dotted with Ata settlements may have been attractive partly because of its ease of access both to Maguindanao and Davao. Rivers connected, playing a significant role in the trading, raiding, and communicating that were well-established by the advent of consistent written documentation in southern Mindanao.

Small details in these writings reflect linkages with other groups, such as Rajal’s observation of corn—introduced by Spaniards to the Philippines—planted alongside rice in Ata villages, or the deity Diwata/Diuata commonly revered by Ata, Bagobo, and other local groups in the Davao area. Today, corn remains an important crop for Pantaron communities and Diwata is still invoked as a deity.

Reaching highland Ata communities may have been very difficult for the Jesuits, but Gisbert’s offhand remark in 1888 that the Atas were familiar with “Chinese and the other retailers” (Arcilla 1998, 173) reveals that the uplands were quite accessible to other sections of the Davao population, especially for activities like trading, which highlanders may have deemed more beneficial than religious conversion. Bolton’s encounter with Tugauanum traders is another example.

Finally, Urios records in 1895 that after what he thought was a successful mission campaign, much to his surprise:

. . . the whole world went back to the mountains at dawn the following day, burning crops, devastating plains, Moros mixing it up with Mandayas, Mandayas with Atas, then with everyone else—war with Spain! (Arcilla 1998, 409)

This may have foreshadowed the revolutionary unrest that would erupt the following year. What it suggests is that in times of turbulence, various people could run to the mountains, perhaps to avoid Spanish authority or to demonstrate defiance to it.

It must be made clear that movement went both ways: from the lowlands to the highlands (such as slave-raiders from lower elevations) and from the highlands to the lowlands (such as Ata tattoo practitioners in Bagobo communities). People traded. In 1896, the final Jesuit-established villages helped settle highlanders on the coast. In the case of the Tigwahanos petitioners in 1906, if the speculation that this group is related to our interlocutors (who remember no other way of life than in the upper Pantaron) is correct, then there were also movements toward the lowlands (to register a petition) and then back up again, to finally settle in the highlands.

These movements and activities facilitated the generation and dissemination of knowledge such that people who self-identified as from distinct tribes were well-aware of the existence and locations of others. From Moré’s “Mandaya chief” to Garvan’s “Salug authorities,” Western researchers maximized local informants’ knowledge of settlement names and locations. The Jesuits, Rajal, and Montano benefitted greatly from such information as they ventured into areas unknown to them. This knowledge may have been locally circulating as early as the conquest-expedition of Oyanguren in the mid-1800s, when Francisco Belmonte informed him that a north-south highland traverse of Mindanao was possible, prompting Rajal’s (1891, 118) simple observation that: “[I]t always turned out that internal communication could take place.” It is almost expected for any historic-ethnographic study to aver that spaces and communities are never isolated, but what is important is to show what comprised these connections. This study fills that gap for the Pantaron highlands.

2.4 The Pantaron Highlands via Epics and Genealogy

A historical reconstruction of the formation and transformation of the Pantaron highlands based primarily on ethnographic data deserves a study of its own (for an indicative example, see Claver [1973]). Here we discuss some ethnographic insights (based on genealogical reconstructions and epic-and-ritual-based practices) that have a direct bearing on the historical data above and community members’ claim of long, continuous dwelling in the Pantaron highlands.

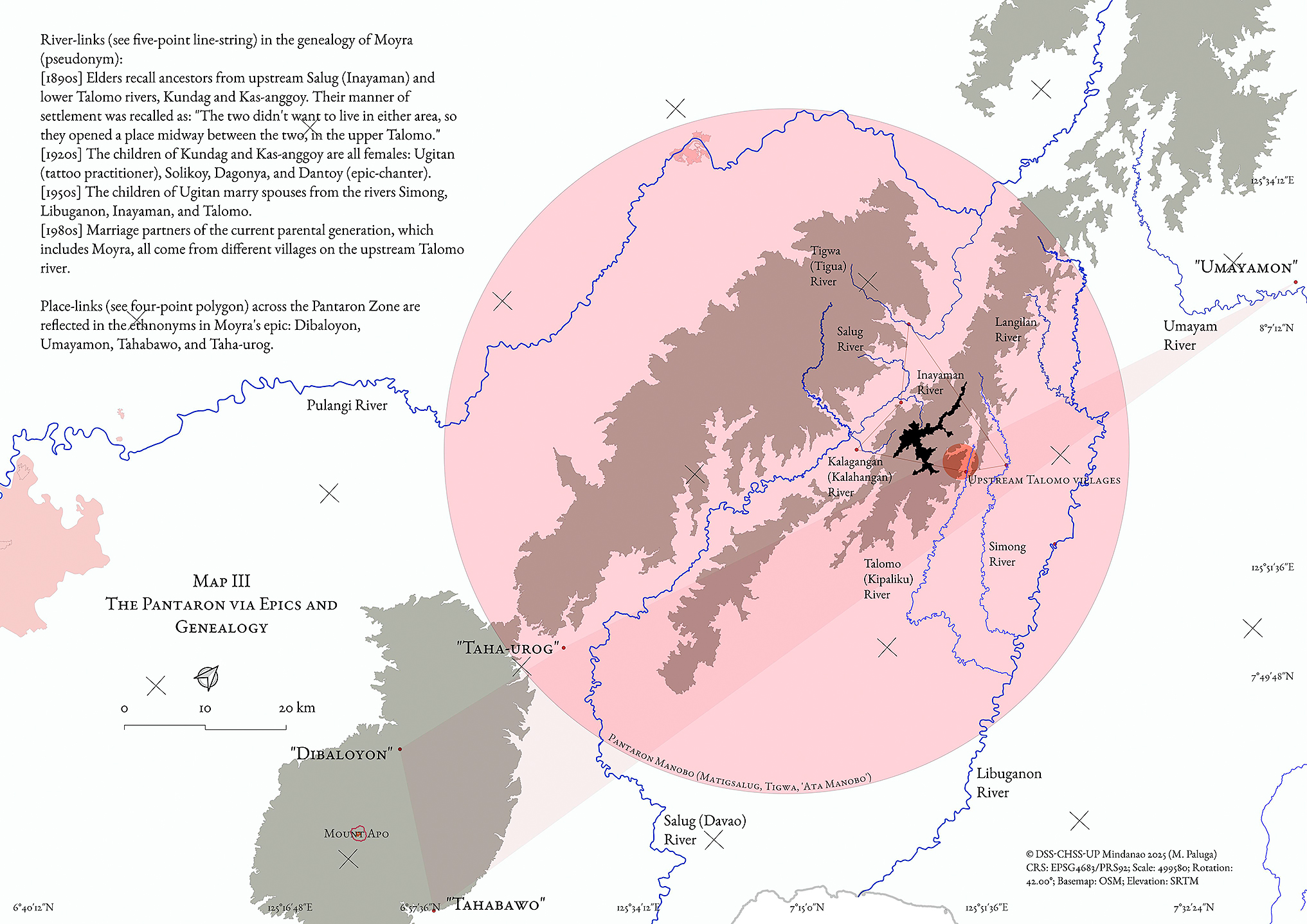

First, we relate an indicative genealogy of Moyra,15) a close interlocutor and epic chanter who lives along the upper Talomo River in what is now Davao del Norte Province. This genealogy, reconstructed through working with her and her family, spans to the 1860s (using a 30-year per generation estimator, see Map 3). Note that the genealogy immediately links four major rivers (including their tributaries) in the upper portions of the Pantaron: the Talomo, the upper Salug (and its tributaries, the Inayaman and Kalahangan), the Tigwa, and the upper Libuganon, which are plotted on Map 3. Comparing this plotting to Rajal’s journey (Maps 1 and 2), Moyra’s genealogy pushes the extent of related highland territory farther east, corresponding closely to the “Atas” areas of the 1900 Mapa Etnografico (Fig. 3).

Map 3 Pantaron Zone Links in the Genealogy of an Epic Chanter from Basalon Village and the World Depicted in Her Man-oloron Epic

Moyra’s family’s genealogy is only one among multiple branches of our genealogical reconstruction. Other branches not detailed here further encompass the wider upper areas of other rivers, such as the Pulangi, Langilan, and Simong. Taken together, these family linkages stretch far beyond what has been tracked in Western expeditions and mapping; Rajal’s encounters with Atas villages west of these rivers may have only brushed up against the outer edges of the highland Pantaron zone demarcated in this study.

Returning to the case of a group of Tigwa people who petitioned for self-governance in 1906, note that the generation of Moyra’s paternal grandfather Piagol (also known as Pialan) is from the Tigwa River. Could Piagol and/or his family members be part of the Tigwa group that moved south, closer to the Talomo? They are never mentioned again after that 1906 petition; they most likely remained in the highlands. Piagol’s marriage to Ugitan suggests the option they took: to forge kinship links, settle in the highlands, and cultivate their lifeways. Ugitan was a tattoo practitioner (Ragragio and Paluga 2019), and her sister Dantoy was an epic chanter who taught Moyra this practice (Paluga and Ragragio 2021).

The epic chanting passed on in Moyra’s family expresses—at the collective, imaginary level—such historical links, which, unsurprisingly, foregrounds river systems both as actual places and as identity anchors. For example, Pantaron epics repeatedly feature (male) characters identified according to the river from which they come, such as the “Young Man from Umayam” (Bato to Umayamon).16) This not only presents, in condensed form, river-oriented identity, but also further expands the sense of relatable and familiarized space beyond what actual kinship or interpersonal links can encompass (Map 3). As one interlocutor expressed, as a child, he knew of the Umayam River because of the character in the epic, but he had never actually been there. Years later, in the midst of an indigenous peoples political campaign, when he finally meets a person from Umayam, he immediately recalls the epic. It is reasonable to think that this prior familiarity (via memories of listening to epics) could have helped foster a sense of solidarity apart from pressing political imperatives.

After all, while epics often focus on combat and adventure, the relevant social unit is usually a group of focal siblings and cousins (such as Tolalang, Agyu, Man-oloron, and others who are the narratives’ “heroes”). These patterns of journeying (under the ambit of the term panow, see Ragragio and Paluga [2023]) across a landscape, when plotted, show the scale and breadth of spatial links in the epic imagination. One epic chanted by Moyra dramatically concludes with the gathering of all Man-oloron’s kin, who are scattered across “five rivers,” to journey together towards the “Land With No Death.”

2.5 Beginnings of the Highlands?

The conventional view of Mindanao history holds that indigenous highland peoples were initially coastal dwellers who were pushed to the higher interiors around the beginning of Western colonization and as a response to the incursions of colonial (and post-colonial) outsiders (Gaspar 2000; Rodil 2003; 2021; TRICOM 1998). However, at least in the Davao area, it can be gleaned that highland communities were already established by the time Spanish authorities definitively took over in the mid-nineteenth century. The formation of such communities therefore took place earlier than colonial actions, such as the founding of Davao pueblo and the sustained Jesuit missions. The sources reviewed here say little about the beginnings of these highland communities. The limited retention of the term balangoy (as explained in the introduction) in Pantaron Manobo oral history could suggest that significant time has passed between the point when these objects functioned as they were intended (such as for sea voyaging) and now.

One catalyst of mobility in the highlands may have been slave-raiding (discussed above). Could this have spurred intensified movement into the highlands? If so, then it is reasonable to expect this historical circumstance to have left its mark in various ways. For example, our collaborators still recount stories of enemies called Ikugan (literally, “creatures with tails”) who attacked villages and captured people. Another such “mark” is the observation that:

The tattoo is especially widespread among the tribes which surround the Gulf of Davao; it is practiced on children from 5 to 6 years old by the mother, in order to impose an indelible mark on them and to be able to recognize them when they are removed by ruse or violence, excessively frequent cases. (Montano 1885, 74)

This insight is repeated in Garvan’s manuscript (1931, 56) a few decades later: “[i]t was customary to change the name of a captive, and as he was sold and resold, the only way to identify him was by his tattoo marks.” Garvan’s account makes it seem that captives were tattooed to mark them as slaves. However, Montano clearly states that Davao tribes practiced tattooing among themselves as protection in the event of being kidnapped and as a means of identification if they were. Community members who practice customary tattooing today do not associate this practice with slavery or captivity (Ragragio and Paluga 2019). Montano’s passage alerts us to how a shift to highland life (spurred by raiding) may have affected certain practices. Speculatively, the practice of tattooing may have originated from the context of slave raids, or—if tattooing existed beforehand (also possible)—it was further reinforced and given new meanings. The emergence of highland life did not only involve shifting location and occupying a new ecological niche but also innovating new practices and/or applying old ones in novel ways. This study foregrounds such developments as shaping highland life, instead of the more oft-cited tropes of an overwhelming “resistance to” and “rejection of” the lowlands.

Conclusion

Combining insights from ethnographic collaborations with Pantaron Manobo and rereading historical documents have cast new light on old sources, questions, and views about the highlands.

The earliest recorded usage of the term Atas (and “ata-as” and “ataas”) was by lowlanders from Davao pueblo to refer to people living at the highest inhabited elevations of the Pantaron in southern Mindanao. They shared a language—or a clinal chain of languages—distinct enough to be discernible to outsiders. “Ata” was formalized as an ethnonym at the turn of the twentieth century, but self-referentially, these communities use names derived from rivers, towards which their settlements were oriented. That many of these river-based names refer to tributaries at upper elevations affirm the importance of the highlands as actual lived space and for establishing identities. That such names were in common use by the time of colonial consolidation in southern Mindanao also strongly suggests that highland habitation and self-identification predate colonial incursions, challenging the conventional view of highland movement and settlement as a response to those incursions.

The Pantaron highlands were an open, multi-cultural space accessible to various people. Its inhabitants were vigorous participants in assorted activities and relationships along the highland-lowland axis, open to a range of outside influences even as their own practices (like tattooing) spread across southern Mindanao.

The first imaginings of the highlands as an inhospitable place inhabited only by people who were forced to live there may be traced to the harbingers of colonialism, whose unfamiliarity with the terrain and whose failure to conquer it would have been a source of significant frustration. But the supposition of the highlands as a tough, undesirable place to live in must be reevaluated (Reid 1998; Mcdonald 2011). Highland living could very well be exceedingly viable; it could be consciously preferred for reasons other than duress. Our collaborators emphasize the sheer beauty and freedom of living in the open highlands. Adopting a “hard, highland living” view unwittingly centers colonialism—and its thematic cognates of resistance or accommodation/negotiation—as the overriding historical circumstance that determined people’s choices; it would do well today to reconsider repeatedly asserting this view.

Foregrounding highlander choices as agentive moves during specific historical circumstances offers more promise for accurate and empowering historicizing. The proposed chronology notes how highland inhabitants alternately appear and drop out of the historical sources. What if moments of high visibility were reconsidered as occasions when they actively assessed potential lowland benefits, and moments when they recede from record as occasions of intentionally choosing highland life? Consider the option of Moyra’s grandparents Piagol and Ugitan, who occupied themselves with practices other than dealing with (or even frequently thinking about) the lowlands. Through varied historical vicissitudes, agents could determine whether to link or delink at any time, an option afforded by highland life.

By adopting this view, we can appreciate the highlands as an inhabited space that was, and continues to be, a recognizable, palpable entity from both within and without. Taken together, Rajal’s phenomenologically vivid account of climbing the highlands, the self-appellations derived from elevated tributaries, and the dense upper river connections of Pantaron communities formed through kinship and epic imaginaries convey a broad-scaled dynamic that has yet to be captured in other ethnohistoric studies on Mindanao, such as Paredes (2013). Instead, Paredes (2013, 31–36; 2016, 335) repeatedly emphasizes the loaded nature of “mountain people,” a term used to denigrate indigenous groups. But by distancing from this connotation to avoid reinforcing it, her studies end up eliding the question of the nature of the highlands as such, thus foreclosing the possibility that the highlands—and the way of life it fosters—can be a productive object of study and reflection.

We argue that not only are highlanders a recognizable entity, but that throughout history, they have been active, inquiring, and decisive whenever they needed to be. Moreover, their decisions would have been taken with a conscious understanding of a highland collectivity that gradually coalesced, if needed, in distinction from lowland “Moro” or “Christian” or “Visayan” peoples. If the settlement of the southern (and possibly central) Mindanao highlands has indeed been longer than previously assumed, then there would have been ample time for highlanders to design a distinct way of life and to develop the highlands into a genuinely vibrant landscape.

Our study draws attention to the historical underpinnings for what has been termed a “tradition of change” (Lundström-Burghoorn 1981, 47), or the conditions under which a community can robustly retain their identity and integrity whilst dealing with various other groups, being receptive to influences, and dynamically experimenting with those influences according to a design of living, which, in the case of the Pantaron Manobo, has been forming and enduring for more than a century-and-a-half.

Pantaron highlanders have been “free borrowers” (Cole 1913, 164) in a milieu where “it always turned out that internal communication could take place” (Rajal 1891, 118); they have been a people who “have caused some trouble from time to time” (Philippine Commission 1916, 136), but were also “of advanced culture, and of great reputation as warriors” (Garvan 1931, 5). Our interlocutors affirm they “have always been in the Pantaron,” which is their way of saying that they are indeed “the people that dwell on the heights.”

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. Erik de Maaker, Dr. Jan Jansen, and Professor Dr. Pieter ter Keurs for contributing to the shaping of this paper, as well as to the anonymous reviewers who helped improve it further for publication.

Notes

1) Our collaborators do not fully embrace the appellation “Ata-Manobo” and “Pantaron Manobo” was arrived at in consultation with them (see Ragragio and Paluga 2019, 263–264) by using a similar approach adopted by Tsing (1990, 429) with Meratus Dayak collaborators.

2) Acabado and Martin (2022) tackle this question for the Northern Luzon Cordillera and claim that highland dwelling is the consequence of expanding colonization.

3) “Manobo” is a label closely associated with indigenous Davao inhabitants (including those from the Pantaron), but because the word simply means “person” or “human being” across widely distributed Mindanao languages, it may be too broad to be useful. Additionally, the earliest uses (by Western recorders) of the term “Manobo” refer to Manobo-identifying people located in eastern Mindanao, as these areas came under colonial control much earlier. Garvan’s (1931) The Manóbos of Mindanáo is exemplar in that it discusses Manobo-identifying people living farther east of the Pantaron, specifically in the Agusan Valley. While our interlocutors know that the current residents of the Agusan Valley are indigenous like them and use the term Manobo, they say they have little else in common. These limitations notwithstanding, “Manobo” is still used on occasions when the term is useful either directly or comparatively regarding the southern Mindanao highlands.

4) The conquest of Davao has been well-covered by Gloria (1987), Corcino (1998), Lizada (2002), Tiu (2003; 2005), and Rivera-Ford (2010).

5) Arcilla’s translation erroneously replaced “atas,” “ataas,” or “ata-as” with “Agtas” (this was verified by examining digitized copies of original Spanish-language Cartas and early translations of Blair and Robertson [1903–07]). Therefore, when directly quoting from Arcilla’s translation, “Agtas” has been replaced with “Atas.”

6) Except for translations by Arcilla (1998) and Blair and Robertson (1903–07), all translations into English are by the authors.

7) Direct quotes retain the original spelling of names of people and places, even if they no longer accord with current, standardized spellings.

8) Rajal (1891, 119) proposes that the term’s root is yawa, a common Bisaya term for “evil spirit.” However, it may more correctly be rooted in mangayow, the Manobo word defined as “to raid, to band together in mass to kill and attack people” (Hartung 2016, 14).

9) See Rajal (1891, 120) for his description of manga-yaoa killings.

10) This Taumo/Talomo River flows from Mount Apo to Davao City and is different from the Taumo/Talomo River whose headwaters are in the Pantaron and flows to the Libuganon River.

11) The inclusion of the “Americans” in the list of people protected by Diwata was possibly a courtesy extended to Benedict by her interlocutor.

12) From the late 2000s to today, with the most recent extended fieldwork from 2018 to 2019 in Davao City (see Ragragio and Paluga 2020).