Contents>> Vol. 8, No. 2

Local Agency in Development, Market, and Forest Conservation Interventions in Lao PDR’s Northern Uplands

Robert Cole,* Maria Brockhaus,** Grace Y. Wong,*** Maarit H. Kallio,† and Moira Moeliono††

* Department of Geography, National University of Singapore, AS2 03-01 1 Arts Link, Kent Ridge Singapore 117568; Center for Southeast Asian Studies (CSEAS), Kyoto University

Corresponding author’s e-mail: coler[at]u.nus.edu

** Department of Forest Sciences, University of Helsinki; Helsinki Institute of Sustainability Science (HELSUS), University of Helsinki, P.O. Box 27, Latokartanonkaari 7, FIN-00014, Finland

*** Stockholm Resilience Centre, Stockholm University, Kräftriket 2B, SE-10691, Sweden

† Viikki Tropical Resources Institute (VITRI), University of Helsinki; Helsinki Institute of Sustainability Science (HELSUS), University of Helsinki, P.O. Box 27, Latokartanonkaari 7, FIN-00014, Finland

†† Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), Situ Gede, Sindang Barang, Bogor (Barat) 16115, Indonesia

DOI: 10.20495/seas.8.2_173

Themes of inclusion, empowerment, and participation are recurrent in development discourse and interventions, implying enablement of agency on the part of communities and individuals to inform and influence how policies that affect them are enacted. This article aims to contribute to debates on participation in rural development and environmental conservation, by applying a structure-agency lens to examine experiences of marginal farm households in three distinct systems of resource allocation in Lao PDR’s northern uplands—in other words, three institutional or (in)formal structures. These comprise livelihood development and poverty reduction projects, maize contract farming, and a national protected area. Drawing on qualitative data from focus group discussions and household surveys, the article explores the degree to which farmers may shape their engagement with the different systems, and ways in which agency may be enabled or disabled by this engagement. Our findings show that although some development interventions provide consultative channels for expressing needs, these are often within limited options set from afar. The market-based maize system, while in some ways agency-enabling, also entailed narrow choices and heavy dependence on external actors. The direct regulation of the protected area system meanwhile risked separating policy decisions from existing local knowledge. Our analytical approach moves beyond notions of agency commonly focused on decision-making and/or resistance, and instead revisits the structure-agency dichotomy to build a nuanced understanding of people’s lived experiences of interventions. This allows for fresh perspectives on the everyday enablement or disablement of agency, aiming to support policy that is better grounded in local realities.

Keywords: agency, participation, rural development, forests, conservation, Lao PDR

I Introduction

To be an agent means to be capable of exerting some degree of control over the social relations in which one is enmeshed, which in turn implies the ability to transform those social relations to some degree. (Sewell 1992, 20)

The structure-agency dichotomy is a deep-rooted theme across most disciplines of the social sciences, depicting “the tension between individual freedom and social constraint” (Rigg 2007, 24). Though much theoretical debate in this vein functions at some degree of abstraction, agency is fundamental to more immediate discourse surrounding inclusion, empowerment, and participation—terms that have proliferated over several decades in relation to bottom-up approaches to development, and more recently in natural resource governance (Parkins and Mitchell 2005), to the point of becoming “institutional imperatives” (Agarwal 2001). Local participation in projects is “argued to exert a strong impact on development outcomes,” often associated with perceived positive impacts of empowerment on governance, inclusive policies, and equitable access to markets, though these claims are not always empirically substantiated (Ibrahim and Alkire 2007, 395). A key focus of participatory or empowering development approaches is “inclusion in decision making of those most affected by the proposed intervention,” with effective participation sometimes considered on a collective rather than an individual basis (Agarwal 2001, 1623). One example of this is the widespread policy trend toward participatory or community-based forest management in developing countries (Islam et al. 2015), implying “a designation of power over forest resources to local people . . . to decide how their forests will be managed and for what purposes” (Tole 2010, 1312). While both support for and skepticism toward community-based forest management have emerged over recent decades, there is mounting evidence that participation of communities and benefits to local livelihoods are “more likely to contribute to conservation effectiveness than conservation without local participation” (Martin et al. 2018, 93).

Contradictions nevertheless arise where external actors attempt to impose ideals of participation and inclusion, whose realization rests on the extent that expression of agency is constrained by entrenched social structures (Sesan 2014). Even where legal mandates for public participation are in place, it is often the case in environment-related interventions that those with crucial local knowledge are limited in their ability to contribute to policy design by the nature of institutional procedures (Simmons 2007, 136). Understanding these dynamics is arguably central to idealized inclusive development in general, as well as more effective and equitable forest policies, in which agency is often entangled in local-level power relations and differentiated access to resources and information (Brockhaus et al. 2014a; Gallemore et al. 2014; Kallio et al. 2016). “Inclusion” in such processes therefore implies the enablement of agency on the part of forest-dwelling communities to inform and influence how the policies and measures that affect them are shaped at different levels.

With this said, agency can often appear as something of a forgotten predecessor to participatory and inclusive notions of development, and is more commonly associated with decision-making in applied research or resistance in Marxian-influenced scholarship in agrarian contexts. In the research presented here, we seek to contribute to debates on participation in rural development and environmental conservation by returning to the structure-agency dichotomy that underpins these concepts, and assembling a nuanced understanding of people’s lived experiences of different forms of intervention. We argue that analysis of individual agency in response to social constraints remains highly relevant to understanding how such interventions are experienced, negotiated, adopted, or indeed rejected by those affected, particularly with respect to those interventions which aim to be participatory or inclusive.

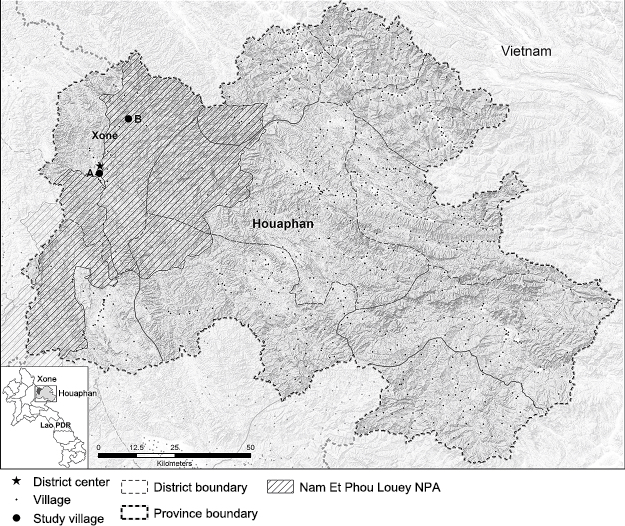

The sections that follow apply a structure-agency lens to examine experiences of marginal farm households in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic’s (Lao PDR, or Laos) northern uplands in three distinct systems of resource allocation—in other words, three institutional or (in)formal structures. We apply this lens to consider: i) the degree to which farmers may shape their engagement with the different systems; and ii) the ways in which agency may be enabled or disabled by this engagement. We explore these questions using qualitative data from focus group discussions and household surveys conducted in two villages of Xone district, Houaphan province (see Fig. 1, Section III-2), which although geographically remote, are far from isolated from the influence of mainstream development practices, state policies, and market integration. The three examined systems are: i) livelihood development and poverty reduction projects;1) ii) a market-based structure for maize contract farming; and iii) direct state regulation under a national protected area. The article proceeds as follows: Section II explores relevant theoretical applications on the theme of structure-agency in agrarian and developing contexts, and how a structure-agency lens might be applied with the regards to policies and interventions affecting forest communities. Section III describes the study context in further detail, the field sites, and methods employed. Sections IV and V analyze and discuss the results of the focus group discussions and household surveys. Section VI concludes with reflections on the application of a structure-agency approach in considering realities for ideals of inclusion and participation, and implications for enabling more direct involvement by marginal households in influencing the policies and interventions that affect them.

II Structures as Systems of Resource Allocation

Individual-society relations are fundamental to the theoretical and philosophical underpinnings of social science (Thompson 1989), forming the basis of thought in relation to the capacity of people to influence the circumstances of their existence (Emirbayer and Mische 1998). The common contrasting elements of the structure-agency tension are that, through the exercise of agency, individuals or groups may “act independently of and in opposition to structural constraints, and/or may (re)constitute social structures through their freely chosen actions,” while lack of agency implies passive adherence to structural constraints, and inability to choose otherwise (Loyal and Barnes 2001, 507). Viewing the social world from the perspective of agency prioritizes the extent of control individuals have over their lives (thereby assuming decision-making power), while the opposing perspective prioritizes structural factors that narrow individual choice (Rigg 2007). Giddens’ formative account, The Constitution of Society, conceptualizes structure as “rules and resources, recursively implicated in the reproduction of social systems” (1984, 377), by which “structures shape people’s practices, but it is also people’s practices that constitute (and reproduce) structures” (Sewell 1992, 5). Sewell expands on Giddens’ framing to focus on the nature of the resource allocation function of social structures, arguing that structure “always derives from the character and distribution of resources in the everyday world” (ibid., 27), with agency as the means of both its maintenance and transformation.

II-1 Agency and Agrarian Change

In agrarian societies, as wide expanses of rural Laos continue to be, agency has long been associated with peasant resistance to structural constraints, such as exploitative extraction of surpluses, arbitrary top-down policies, elite- or state-driven pressures on land and livelihoods, and resulting social differentiation (Scott 1985; Hart et al. 1989; Kerkvliet 2005; Caouette and Turner 2009; Hall et al. 2015). The exercise of agency in these forms is exemplified in the Southeast Asian context in Scott’s work on “moral economy” and everyday resistance (1976; 1985). While moral economy is concerned with social unrest resulting from the undermining of subsistence arrangements and violating peasants’ “notion of economic justice” (Scott 1976, 3), open rebellion is an exception to the norms of everyday resistance (Scott 1985)—mundane, day-to-day struggles against exploitation through non-adherence to rules. The power of everyday resistance as a form of collective agency in response to top-down structural constraints is perhaps nowhere better depicted than in the widespread non-compliance that reversed Vietnam’s agricultural collectivization policies in the 1970s and 1980s (Kerkvliet 2005). Laos enacted a concurrent collectivization campaign in the late 1970s (see context, below), although coercion and the (albeit often grudging) participation of the population meant that its reversal was less a result of direct resistance than the urgencies of low productivity and food shortages (Evans 1995; High 2014). Because of general subservience to the directives of the centralized state, and in some cases, fear (High 2014), resistance took more evasive forms in Laos compared to Vietnam. These included smuggling farm output to cross-border markets, moving upland swidden cultivation deeper into remote mountains with less state control, and the mass exit of refugees across the Mekong river to Thailand (Brown and Zasloff 1986; Bourdet 2000).

Despite its value as an understanding of local agency in response to structural constraint, resistance can also be overapplied or “essentialized” into narratives which fail to provide a balanced reflection of people’s abilities to pursue positive outcomes from changing political and economic conditions (Forsyth 2009). In the post-reform re-engagement of Laos and Vietnam with the wider Southeast Asian region during the 1990s, and rapid expansion of transboundary investments in commercial agriculture and natural resources that followed, agency remains a key consideration in how the remnants of agrarian societies navigate structural changes to maintain and seek new opportunities (Michaud and Forsyth 2011; Turner 2012). Beyond everyday resistance, understanding responses to rural transformation can be enhanced by considering the relationship between individual agency and people’s perceptions of structural constraints (Drahmoune 2013), examined below in the context of development, market, and forest conservation interventions in Laos.

II-2 Agency, Development, and Sustainability

Applied understandings of agency have in many ways significantly expanded through recent focus in mainstream development literature on concepts of participation, inclusion, and empowerment, frequently in relation to human well-being. It is a measure of the leeway in these terms that they are often used in combination, if not interchangeably, while applying diverse definitions (on agency and empowerment, see Ibrahim and Alkire 2007). Much work on these themes draws from Sen’s widely influential capabilities approach (1999), which considers the constraining effects of deficient agency on human well-being, through limiting the ability of people to pursue the life they value. Several significant advancements to the capabilities approach include the proposal of internationally comparable indicators for agency and empowerment (Ibrahim and Alkire 2007); quantitative study of the relationship between agency, dignity, and subjective well-being (Hojman and Miranda 2017); and of the suppressive effects of low agency (or “unfreedom”) on the relationship between wealth and well-being (Victor et al. 2013); with implicit links in each case to the central structure-agency tension between individual freedom and social constraint (Rigg 2007).

Although it is useful as a basis for policymaking to explore the effects on individual choices and well-being outcomes of constraints on agency in a comparable and systematized way, the meeting of subjective terms with numerical indicators is not without problems. Loyal and Barnes (2001) reject the possibility of finding a robust measure of agency at all, while Emirbayer and Mische (1998) portray the exercise of agency as an internal process, by which individuals prioritize between past iteration or habit, responding to immediate contingencies, and a “projective” capacity toward future possibilities. Meanwhile, agency has had an increasing tendency to be operationalized in the social sciences as “decision-making” (Kabeer 1999), though often with limited reference to the intangible circumstances surrounding individual decisions, and whether these may be enabling or disabling. In the context of sustainability, agency is considered a critical determinant of the response of individuals, households, and communities to external stressors, but rarely features in policy approaches which tend to remain predisposed to “objective,” distributional issues relating to resources and infrastructure (Brown and Westaway 2011).

Efforts toward participatory governance are one approach to correcting this imbalance, emphasizing the importance of diverse voices of those directly impacted by processes of change (Leach et al. 2010). Studying the representation of such voices in the context of protected area management in Indonesia, Myers and Muhajir observe that “people struggle to participate where governance structures ignore them by either an unwillingness or inability to advance community claims upward within the democratic structures” (2015, 379). This is exacerbated by technocratic interventions that tend to compartmentalize socio-political concerns into measurable and obtainable targets, while multi-level governance increases the complexity of realizing the participation of stakeholders at local level. Myers and Muhajir argue for “securing a voice for forest users . . . to participate in the decisions about land over which they lay claim” (ibid.). We now turn to agency in relation to forest conservation in greater detail, before exploring lived experiences of policies and interventions in the uplands of northern Laos.

II-3 Agency in Forest Conservation Interventions

The extent of agency on the part of forest-dwelling communities in relation to often externally designed (i.e., by national and/or international organizations) policies and interventions is an open question, and highly context-dependent. Referring to would-be inclusive forest management, Galvin and Haller observe that participatory approaches appear to have emerged as institutional means of “reconciling local people with conservationists, and conservation with development,” with the underlying objective of balancing participation with protection agendas (2008, 17). Even as community participation in managing local resources has become firmly embedded in mainstream development logics, policy support has often remained in the domain of rhetoric (Colfer and Capistrano 2005).

At global level, indigenous alliances have on the one hand been increasingly acknowledged in policy negotiations, though with less direct agency in terms of participation in shaping rules relating to interactions between people and forests (Schroeder 2010). At the national level, Brockhaus et al. (2014b) observe that while minority coalitions have focused attention toward environmental justice in some countries, including participation of indigenous peoples in policy processes, these are rarely framed in opposition to large-scale investments that impact forests, inadvertently reinforcing structural drivers of deforestation and forest degradation. Focusing at national and subnational scales in Vietnam, Thu et al. (in press) emphasize the gulf between actors engaged in the design and implementation of forest policies and swidden farmers living in forested upland areas, despite the latter being among the most affected, largely due to a state-led discourse that rejects the continuing existence of swidden cultivation, and thus blocks participation of farmers in policy processes.

Upland farmers in Laos have similarly faced a range of constraints set in place by policies in which they have minimal input, including resettlement of rural populations and land reclassification measures aimed at tightening control over access to forests and eradicating swidden cultivation (Baird and Shoemaker 2007; Hett et al. 2011; Castella et al. 2013). As part of these measures, Laos’ network of national protected areas (NPAs), nominally covering about 14% of national territory, resulted from shifts in policy since the late 1980s to maintain the surviving forest resource base after prolonged heavy logging (Ingalls 2017; Robichaud et al. 2001; Sirivongs and Tsuchiya 2012). Renewed policy emphasis toward protecting forests and biodiversity also meshed well with the rising global development focus on sustainability, which came to dominate aid priorities and strongly influence international project funding in Laos in the 1990s (Singh 2012). Reliance on forest land and resources for livelihoods among marginal rural populations living in proximity to the NPAs make local participation integral to their effective management (de Koning et al. 2017; Sirivongs and Tsuchiya 2012). To this end, while beginning from an expert-led and exclusionary “fortress conservation” model of forest management (Ingalls 2017), soon after establishing the NPAs, the Lao government set in law a participatory approach to protected area management with the aim of involving and benefitting local populations (Rao et al. 2014). Despite the apparent meeting of interests between international donors and the state, Singh notes that “this interpretation is strongly challenged when the focus shifts from policy to practice” (2012, 40), and scientific approaches to conservation have tended to be persistently viewed as a foreign aspiration, concealing people’s everyday knowledge and the needs of local livelihoods.

Competing power claims inevitably underlie the enclosure of forests containing established communities, and local agency in Laos’ NPA system has in some cases been noted as more on the basis of opposition and subversion than participation (Ingalls 2017). Although aimed towards creating a model of “sustainable livelihood and conservation strategies which strongly advocates people’s involvement,” trust issues, contestation over resources, poor information flow to forest-dwelling communities, and unsustainable funding and political will have sometimes constrained ostensibly agency-enabling ideals (de Koning et al. 2017, 88). While NPAs play an essential role in conserving Laos’ forests, they do so in a complex policy arena in which technical interventions remain driven by international organizations, though as is the case elsewhere, often failing to engage powerful economic interests that underpin unsustainable exploitation of forests (Cole et al. 2017a), and in which local voices may go unheard.

Referring specifically to the Nam Et Phou Louey NPA in Laos (also the study location of the present article, see below), Martin et al. (2018) observe that despite livelihoods being in some cases severely curtailed by the enclosure of the forest, local communities nevertheless express broad support for the NPA. The high degree of receptiveness to internalizing messages on NPA restrictions and intended benefits is shown in the study to be due to perceived historic dependence on authority, such that “rules are followed not because they have popular support, but simply because they are the rules and are backed up by hierarchical power” (Martin et al. 2018, 103). De Koning et al. argue for rights-based decentralized governance as a pathway to collaborative management of protected forests in Laos, notwithstanding the needed “ongoing political will to consolidate and sustain these arrangements” (2017, 87). This argument might equally apply across diverse forms of development intervention, and we add that such inclusive ideals should be understood as rooted in the enablement of agency, underpinned by the conditions of interactions among the actors involved, and those of engagement and exchange of information and resources among would-be participants.

In the following sections, we consider how agency can be understood by people’s lived experiences of three distinct rules-based systems of resource allocation that affect everyday life, as identified by respondents in two villages of Laos’ mountainous Houaphan province. We defined such a “system” to comprise: i) resources and/or knowledge that are exchanged; ii) actors who instigate exchanges; iii) purposes for the exchange; and iv) social foci and tools that facilitate the exchange (in other words: what, among whom, why, where, and how exchanges occur). As such, these systems can be considered analogous to how social structures are (re)produced through actors’ recursive actions, according to (or in defiance of) schemas of rules surrounding resource allocation (Sewell 1992).

While the livelihood development and poverty reduction projects and national protected area systems are policy-driven interventions, involving both national and international organizations, the maize contract farming system is primarily market-driven (albeit complying with state aims to commercialize the agricultural sector, and with limited local government involvement), and run by networks of Vietnamese and Lao traders. In the context of continued reliance on swidden agriculture among a majority of upland farmers in the studied communities, the interaction between these systems highlights long-running tensions between State objectives and local realities. As is commonly observed in upland areas of Southeast Asia, Laos’ rural development policies have for decades sought to stabilize and ultimately eradicate swidden due to its perceived destructive environmental impacts and non-adherence to State-favored, sedentary practices (Heinimann et al. 2013; Kenney-Lazar 2013; Scott 1998; 2009). Moves toward intensive commercial agriculture such as maize contract farming are thus welcomed and indeed promoted by local governments as a more stable alternative to swidden (despite frequently accelerating conversion of land and forests), though upland farmers often continue to cultivate swidden rice as the main food crop, whether by necessity or choice (Heinimann et al. 2013; Vongvisouk et al. 2016).

III Study Context, Sites, and Methods

III-1 Context

Rural development has been an unwavering focus of government rhetoric and policy since the founding of the Lao PDR in 1975, with consistent aims to reinforce state legitimacy by improving living conditions and “modernizing” livelihoods; and to extend state authority over marginal rural spaces and integrate upland minorities into the mainstream (Évrard 2011; Singh 2012; Cole and Ingalls, forthcoming). During the post-war period of “high communism,” these objectives were pursued through a collectivization campaign—envisaged to boost agricultural output and achieve food security, while also reordering peasant society under a “legible” social structure (Evans 1988). To a large extent, these efforts proved ineffective, and coupled with the risk of general economic collapse brought on by Laos’ isolationism, led to an urgent push for reforms by the mid-1980s (the New Economic Mechanism), and subsequent re-engagement with the ensuing regionalization under the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) (Evans 1995; Stuart-Fox 1995; Pholsena and Banomyong 2006). Market reforms have underpinned long-term policy emphasis on agricultural commercialization as a foreseen fast-track to poverty reduction in rural areas, alongside the widespread resettlement of remote villages closer to roads and district centers, albeit with widely observed negative impacts among the poorest sections of society (Rigg 2005; Baird and Shoemaker 2007). ASEAN integration and infrastructure-building since the 1990s, in combination with the government’s decade-long policy on “turning land into capital,” have created inroads for large-scale transboundary land acquisitions, transforming land relations, and frequently increasing pressure on marginal land and livelihoods (Baird 2011; Ingalls et al. 2018a; Cole and Ingalls, forthcoming). These same processes of integration have gradually geared Laos’ rural economy toward the demands of neighboring China, Vietnam, and Thailand (Bourdet 2000; Rigg 2005), including for bulk agricultural commodities via a proliferation of cross-border contract farming arrangements (Cole et al. 2017b), as exemplified below.

With Laos’ global re-engagement came the significant presence and influence (particularly via aid funding patterns, see Singh 2012) of the international development sector, and sharpening discursive focus on participatory, inclusive, and sustainable development, environmental conservation, and more recently “green growth” (Kallio et al. 2018). However, the heavy emphasis of elite interests and foreign investments in land- and resource-intensive sectors places notions of sustainability firmly at odds with an economic model based on agricultural intensification and the exploitation of natural resources (Cole et al. 2017a; Ingalls et al. 2018b). Epitomizing the complexity of this tension is the forestry sector: at once a key source of revenue for the nascent communist government since the late 1970s; the focus of entrenched elite interests for large-scale land concessions, such as plantations; and of wide-ranging donor-funded forestry initiatives, including the extensive national protected area network (Robichaud et al. 2001; Cole et al. 2017a; Cole and Ingalls, forthcoming). Similar tensions are observed in other sectors that loom large in the sustainability agenda in Laos, notably water resources management, and are commonly framed as “trade-offs” between conserving the environment and rural livelihoods on the one hand, and harnessing resources for national development on the other (Friend and Blake 2009; Wong 2010). The level of local participation in such decisions may often be questionable, highlighting the fragility of terms such as inclusive or participatory development, and the importance of understanding the varying extents to which plans made from afar may enable or disable agency among the people most directly affected.

III-2 Sites

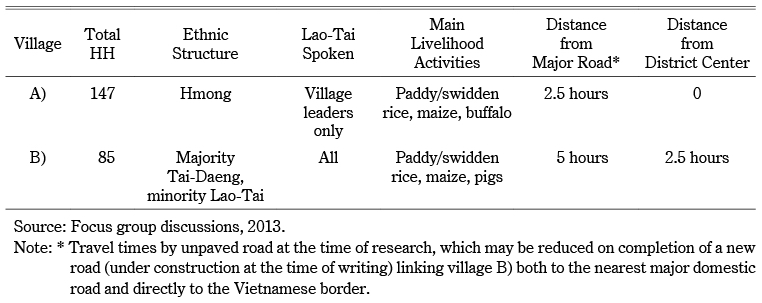

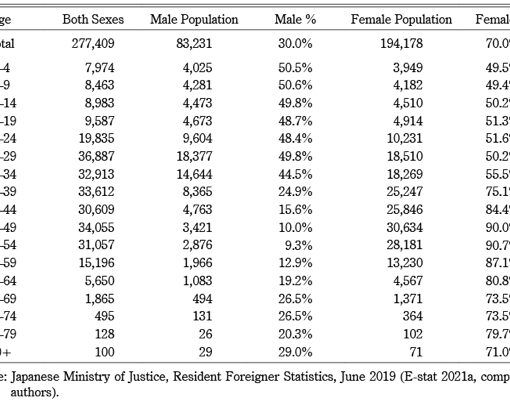

The analysis that follows is based on data collected in 2013 in two villages of Xone district, Houaphan province, northern Laos (Fig. 1), anonymized as village A) and village B). The sites were selected on the basis of swidden cultivation being the dominant land-use system; the presence of significant forest cover; and the presence of factors affecting land access and the maintenance of forest cover—in this case, proximity to protected forest. Xone and the neighboring district of Hiem2) collectively cover more than 3,750 km2, approximately 70% of which is enclosed by the Nam Et Phou Louey National Protected Area (NEPL-NPA). Established in 1993 as part of the above-mentioned land reclassification and expansion of the NPA system, NEPL-NPA covers an area of 422,900 ha spanning three provinces, of which the majority area is located in Houaphan. NEPL-NPA has been under active management since 2000, aimed at protecting forest and endangered wildlife, and promoting sustainable land-use via regulations endorsed at provincial and district levels in 2008 (Hett et al. 2011). While NEPL-NPA has a significant role in provincial-level forest governance in Houaphan, it has nevertheless been encroached by commercial maize cultivation since the rapid uptake of the crop by farmers in the 2000s (Vongvisouk et al. 2016). Agriculture is the main livelihood, commonly a combination of paddy and swidden rice, vegetable gardening, and maize, the main locally-produced commodity crop,3) for which Xone district serves as a collection point for several Vietnamese- and Lao-operated businesses. Cultivation of maize expanded dramatically around 2010, when high demand in Vietnam fostered promotion of the crop by district authorities to support rural income improvement, while simultaneously encouraging traders and collectors to engage with farmers in Laos. In village A), maize was commonly grown on the available sloping land surrounding the village, in combination with a range of other livelihood activities including livestock and non-farm work in the neighboring peri-urban district economy. Although more remote than village A), village B) is also more self-contained, with a large area of paddy land and overall territory of 20,000 ha, including swidden fields mostly turned over to maize at the time of the research. Table 1 summarizes basic characteristics of the two sites.4)

Fig. 1 Map of Study Sites, Xone District, Houaphan Province, Lao PDR

Table 1 Characteristics of Study Sites

III-3 Methods

Focus group discussions differentiated by gender and age were undertaken at each village during May 2013. These activities first aimed to gain detailed accounts of historical structural conditions of resource allocation, particularly relating to land, along with general environmental, economic, and social characteristics at the two sites. Second, the discussions were designed to distinguish and prioritize social structures that dominated village life in the eyes of respondents, represented by the systems described above, comprising livelihood development and poverty reduction projects, maize contract farming, and NEPL-NPA. The three systems and networks of actors involved were then further explored in household surveys conducted from September to December 2013, with 40 randomly selected household heads per village. Resulting qualitative data were analyzed by focusing on patterns of participation in decision-making processes and resulting actions, the nature of interactions between actors and ability to influence decisions within the three systems, aspects of dependency and circumstances of non-participation. We do not claim that this approach offers a fixed measure of agency, though we argue that the value in applying a structure-agency lens lies in considering ways that agency might be enabled or disabled by structural conditions, which in the context of this study can be linked to respondents’ ability to engage in and shape decisions and interventions that affect them.

IV Results

IV-1 Historical Structural Conditions of Resource Allocation

Differing historical trajectories in the two villages offer insights into the structural conditions of resource allocation, particularly in terms of differentiated access to land, and the influence of this on local livelihoods. Village A) was established through the resettlement of several remote Hmong hamlets since the late 1990s to land adjacent with present-day Xone district, in line with long-running government policy to relocate isolated ethnic minority communities in the uplands closer to roads and state services (Évrard and Goudineau 2004; Évrard and Baird 2017). The initial resettlement comprised 37 households, and more than 100 further households had since relocated there by 2013. Though an integral policy objective of village resettlement has been to contribute to the stabilization of swidden cultivation in the uplands (Baird and Shoemaker 2007), resettled populations must also navigate existing (formal and informal) land allocation regimes in the new location (Lestrelin and Giordano 2007). This process is differentiated not only between resettled and existing populations, but among the social strata of the resettled group, and among earlier and later arrivals. In village A), irrigated paddy land was allocated only to initial settlers, who were also commonly assigned various official roles, thereby gaining positions of enhanced agency in local-level decisions. While the initial settlers and those following shortly thereafter were also able to access additional agricultural plots reallocated from neighboring villages, later arrivals received land only for housing construction. The allocation of land in village A) is thus observably embedded in a historically bound schema of rules, derived from a combination of government resettlement policies, local regimes of land allocation, and stratified social relations at different stages of resettlement.

Many households maintained former swiddens and sanam (secondary villages close to rice fields, built to accommodate peak labor requirements in the agricultural cycle) in the areas they previously farmed before resettlement. These were continuously occupied to some degree, sometimes for two to three months at a time by a varying number of individuals based on the size of household, and thus mobility between the village and the sanam was virtually constant. Villagers accessed sanam lands at different locations and distances from the new village, the furthest being more than 20 km away along mountain tracks. The need to retain distant former lands might on the one hand be viewed as demonstrating minimal agency in the face of constraints that the households had no control over—in this case barring some (especially late-comers) from accessing land in the new village. On the other hand, the act of sustaining a livelihood in a location far from the reach of local authorities, and in doing so operating on one’s own terms, might also be viewed as a form of agency through passive dissent. Those cultivating the sanam swiddens continued to primarily grow rice as opposed to maize, since this was considered more practical for storage and transporting to market while providing a secure supply of food. Living in the remote sanam also entailed isolation from services and wider economic opportunities however, and thus “agency” in this case should be considered as actions within a severely limited field of options.

Village B) is the more established of the two sites, existing since the late nineteenth century. In accordance with the collectivization campaign set in place nationwide in the late 1970s (Evans 1988; Castella and Bouahom 2014), village B) was instructed to reorganize as a production cooperative. This entailed a reorientation from the former traditional mode of land allocation within the community (on a five-year basis according to household size), to the communal contribution of labor, and allocation of output among all households based on the labor invested. The cooperative model remained in place in the village until 1987 with the shift in national policy toward market-orientation, and despite the collectivization policy having been officially cancelled several years earlier due to general ineffectiveness (Evans 1995).

One direct local outcome of this transition was that all former privately owned paddy lands collectivized during the 1980s were returned to the previous owners. While those who had not previously owned land were largely excluded by this process, some of the paddy area that had been expanded through collective efforts during the cooperative period was assigned as communal, and referred to as “village land.” Half of the collectively expanded paddy was initially reallocated among individual households and the rest held communally, eventually reducing to one-third in 2004. This land remained communal at the time of the research, though there were plans for further reallocation according to household size. The differing trajectories of the two villages, and resulting schemas of rules surrounding the distribution of agricultural land, underline ways that marginal upland communities in Laos have historically been subjected to shifts in policies in which they have minimal control, but which often carry dramatic and long-term impacts. As development policies and interventions designed at both international and national levels have increasingly emphasized participation and inclusion, whether this is subsequently reflected by greater enablement of agency among local populations remains a source of ambiguity.

IV-2 Participation in Resource Allocation Systems

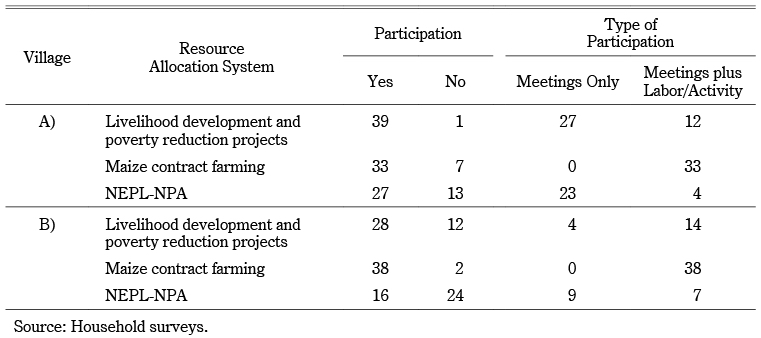

Table 2 shows the share of respondents in the two villages reporting participation in the three systems of resource allocation. Our analysis further differentiates whether their self-described participation was confined to attending village meetings, implying presence during related decisions and receipt and/or exchange of information, or also included providing labor for specific system-related activities, implying more active engagement. The highest proportions of participation for both villages were in livelihood development and poverty reduction projects and maize contract farming. The maize system universally entailed both attending village meetings and labor (i.e., cultivating maize) among all who described themselves as participants. Responses were more mixed for livelihood development and poverty reduction projects, with a greater overall share of participation in village A), perhaps reflecting its proximity to the district seat of power, though participation was more active in terms of labor in the more remote village B). Participation in the protected area system was lower in both villages, particularly village B) which is located deepest within the boundaries of NEPL-NPA (see Fig. 1), and mostly entailed attending meetings only.

Table 2 System Participation by Village

Respondents who described themselves as participants had varying knowledge of and interactions with the networks of actors involved in the three systems, in turn implying different levels of knowledge of how the systems function, and the distribution of responsibilities within them. Respondents who stated knowing one actor (or actor category, e.g. “district staff,” “foreign experts” or simply “the government”) tended to be the largest group, while those listing second and third actors tended to be respectively fewer. Respondents who personally knew actors referred in the majority of instances to maize traders or members of the village committee. The most commonly named actors were the village heads, who in turn were often the only residents of the two villages who stated that they personally knew local officials, demonstrating both their intersecting role in the functions of each of the three systems, and as gatekeepers to official information.

IV-3 Livelihood Development and Poverty Reduction Projects

Almost all respondents in both villages reported regular visits by staff of projects, one village A) respondent commenting that “they’re always coming here” [A4]. In village B), most respondents referred to each project by its purpose, such as “livestock project,” “poultry project,” or “assistance,” though source organizations were often conflated (e.g. a visit by a German development agency was described by one respondent as an “aid project of America” [B27]). The most commonly named project activities in both locations were those relating to the Poverty Reduction Fund (PRF),5) understood by many respondents to be behind most village-level development activities, particularly construction of hard infrastructure such as local water supplies, clinics, and schools. Some respondents had contributed labor to the construction of these facilities, which in village B) included irrigation for paddy fields allocated to resettled villagers. Altruistic views of the visits by officials connected to the PRF were quite common among respondents, that “they develop the rural areas” [B7]; “they came here to develop our village” [B8]; and “to solve the poverty of the people” [B35]. Another village B) respondent elaborated on the rationale behind the PRF: “they want us to be happy and have a comfortable living . . . they just want us to make money” [B26]. In village A), perceived purposes of project visits tended to be more general, often referring to improving living conditions, some linking this to policy and geographical disparities, “because people in the highlands do not gain enough from government policy goals” [A28]. Others associated project visits with announcements and the promotion of various aims, including planting commercial crops, and the more idealistic “village solidarity” and “self-development.”

The village head was considered a focal point in both locations, convening meetings, channeling information to the village, mobilizing labor for projects, and explaining local needs to project staff, thereby exerting influence over outcomes at the village level. Specifically for the PRF, the village head was also considered responsible for gathering the opinions and concerns of villagers and appealing to the government to support development needs, for which funding and construction may then be considered. Village A) respondents were least aware of specific actors relating to livelihood development and poverty reduction projects, commonly depicted as unnamed external officials visiting the village head, who sought agreement with the “relevant organizations,” after which the “officials called on the village and assembled the villagers for development” [A16]. The procedures of working with projects were reflected on in more detail by the village head, which for the PRF would begin with a visit by an extension officer to survey the condition of the village, after which the village committee would send a written request for assistance to the “agriculture office,” which then “sent the project to help the village” [A35].

Respondents in village B) considered district officials to be responsible for announcing PRF projects, promoting agriculture, and being a source of funding and occasional rice donations, while provincial officials were considered responsible for gathering and announcing information. District government staff were perceived as the most influential actors in the delivery of development interventions to village B), and described by some respondents to be acting out of concern for local living conditions, providing guidance over how to improve the village, including construction of PRF infrastructure. Other respondents connected the work of district officials in the village to broader national development and poverty reduction narratives, “because now the society is more convenient than before, and to help villagers develop to improve [their] life” [B24] and “avoid being out of date” [B32]. Some focused more strongly on this modernization role, describing the efforts of the district as helping “villagers to make their lives more like in the town, with electricity, water supply” and birth control [B9]; as well as to “upgrade their living to be better than the old system, and give them the new system to bring income to the family” [B40], based on livestock raising and cash crops.

IV-4 Maize Contract Farming

Perhaps representative of this perceived “new system,” most respondents in both villages had actively participated in maize contract farming for about two to three years at the time of the research. Vietnamese traders and companies were considered to hold greatest influence over the maize system in village B), having initiated production of the crop in the village, though some respondents were only aware of “businessmen” of both Lao and Vietnamese origin. The diverse perceptions of importance of business actors included showing villagers how to produce maize, offering contracts, seed loans, and other credit, and collecting and transporting the harvest (including cutting feeder roads to hard-to-reach hillsides). Some respondents explained that the companies directly approached the village leaders to invite them to encourage villagers to engage in maize contracts. Others considered that district officials had played the most prominent role in promoting commercial maize production and authorizing maize companies to operate. In both villages, the village head continued to hold significant influence in the maize system for many respondents, introducing the companies to the village, acting as the facilitator of contracts, arranging meetings, and keeping records. The village A) head’s role extended to managing the engagement of different households in contracts and distribution of seeds supplied on credit by the company, and in some cases, guiding villagers on maize production, based on knowledge gained from the village cluster (sub-district) or other villages.

Of the more than three-quarters of respondents in village A) who grew maize, a majority were directly acquainted with business actors that introduced the contract farming system to the village. Varying accounts were given of how this process occurred, involving combinations of Vietnamese, Lao, and local Hmong actors, with kinship networks seemingly playing a prominent role. Many respondents considered that the Vietnamese company first cooperated with the district authority over the buying price, after which the district allowed the company to operate, local authorities encouraging people to “turn to new jobs to make progress, and stand on your own two feet” [A12]. Some even alluded to a kind of moral philanthropy on the part of the business actors, who would highlight the deficiencies of “people’s living in the past, when they only cut trees and destroyed forest. We cleared forest for shifting cultivation for many generations, but we never achieved prosperity” [A5], arguing the case for commercial crops as a solution, which the company would buy “to reduce poverty” [A18]. Others reported that the district and company organized a village meeting to “announce information about plans for growing maize to transform people’s livelihoods” [A13]. In these cases, the company would be considered of greatest importance: “these businessmen arranged everything” [A5], lending seeds and purchasing the product, as well as ploughing fields and cutting feeder roads based on the contract terms with producers. Lack of land and labor were barriers for the few respondents who did not grow maize.

IV-5 Nam Et Phou Louey National Protected Area

Most respondents’ experiences of NEPL-NPA related to announcements and meetings delivered by district or project staff, with the village head often the point of contact, who would then inform villagers of conservation restrictions, as well as penalties of failing to observe them. Few respondents were able to name specific project actors in the NPA system, and those of influence were otherwise generalized in both villages as project and/or district staff. Few respondents listed a second actor beyond the village head. Provincial and district staff were considered important in translating policy, in that they “come to the village to announce what the government announces, especially about the rules and principles” [A8], initially training and informing the village leaders on “advantages and disadvantages of forests in the past, present and future” [A6]. Respondents also referred to visits by a survey team of district staff to identify and announce where the NPA borders affect village land, “so that [villagers] don’t go to destroy” the forest [A6]. Such visits would include providing information on using forests sustainably, occasionally delivered by “foreign experts,” but in some cases also village elders. The experience of NPA visits seemed less constructive in village B), the head expressing frustration that NPA staff “just say they will come to help people like this, like that, but that project is not good, they just come to advertise, such as pictures of hunting animals” [B36]. Most respondents identified the role of the village head with calling meetings to announce the NPA borders and banned activities such as wildlife hunting and forest clearance, cooperating with the provincial and district staff and following up enactment of regulations. Perhaps again reflecting closer proximity to the district center, the village A) head was directly acquainted with senior staff of the NPA and described their role as demarcating accessible land, explaining its sustainable use and rules to restrict activities that impact forests and wildlife.

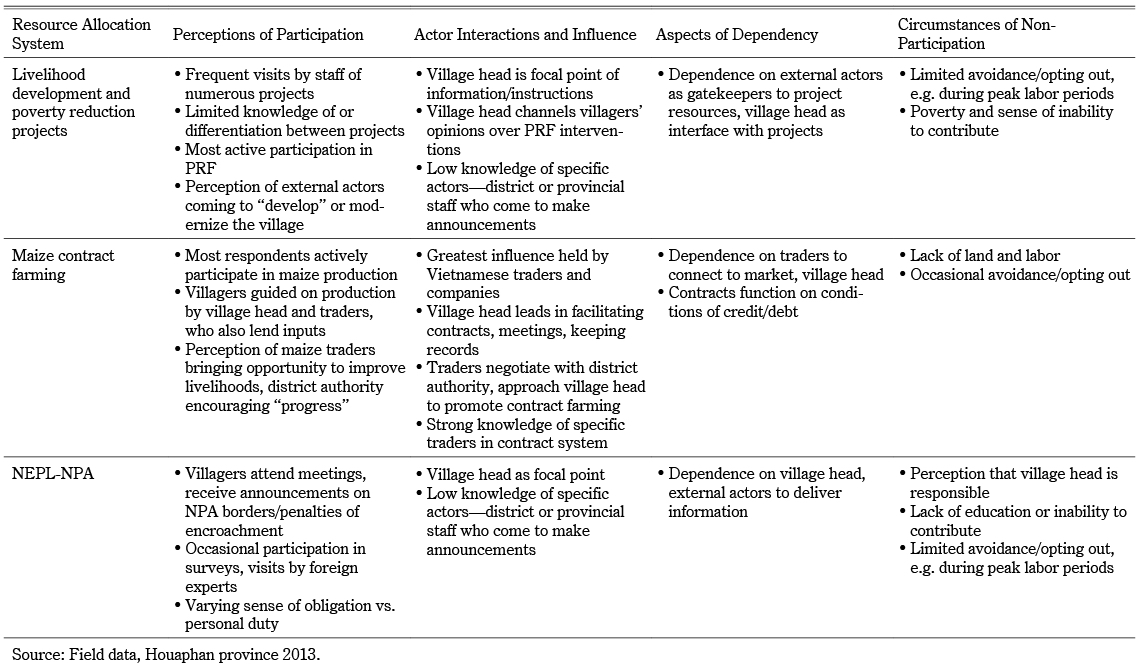

About one-third of respondents in both villages had some knowledge of further planned forest or conservation related projects. Descriptions in village B) included awareness of climate change projects gained from forest conservation staff, and announcements relating to NEPL-NPA and the ongoing drive to eradicate swidden cultivation. Respondents in village A) referred to forest-related projects, including those associated with NEPL-NPA, information campaigns on forest conservation led by the district authorities, and related visits from foreign experts. Most respondents expressed interest to participate in forest conservation, whether to fulfil government plans and prescribed obligations, or responding to the need to protect local resources. Other motivations ranged between the more passive stances observed in relation to the other systems (e.g. “I will wait for the head of the village to announce the relevant information” [B15]; “I’ll do, if they want me to do” [B22]), to concerns over missing out on opportunities for material or informational advantage (“If the project has benefits to the villagers, I also want to join” [B16]; “If they tell us I want to attend, I need to know what they talk about” [B30]). For others, desire to participate was more pragmatic, some expressing the wish to do so only if “convenient.” When asked how they considered they might contribute to implementation, responses again varied between passive recipience and following changes in laws and regulations (“we will do what they order” [A2]; “I will follow the plan the government announces” [B30]); to desiring an active role and being a model for other households. Of the more active responses, some directly referred to learning how to protect the forest, contributing labor and equipment if they possess it, and planting trees, while one respondent asserted that “the villager must be in a strong role in this program” [B27]. The few respondents who were not interested either believed forest-related projects to be the responsibility of the village head, or otherwise considered themselves ill-equipped in terms of knowledge, too old, or facing too many difficulties of their own to engage in such things. Table 3 summarizes the results by the three systems of resource allocation.

Table 3 Summary of Results by System

V Discussion: Local Agency in Systems of Resource Allocation

Part of what it means to conceive of human beings as agents is to conceive of them as empowered by access to resources of one kind or another. (Sewell 1992, 10, original emphasis)

The previous section examined the historical-structural conditions of resource allocation within the study villages, and patterns and experiences of participation in the three resource allocation systems of livelihood development and poverty reduction projects, maize contract farming, and the NEPL-NPA. Respondents’ interactions with each system are governed by its respective institutional structure and resulting allocation of different kinds of resources—varying forms of development assistance through the projects system; production inputs and income through the maize system; and information and the maintenance of forest resources through the NPA. The further aim of adopting a structure-agency lens is to examine the ways that these structures may “limit, constrain or enable human action” (Rigg 2007, 27), by contrasting their agency-enabling features that may allow people to influence the decisions that affect them with aspects of dependence and circumstances of non-participation.

Within the poverty reduction and livelihood development projects system, the bottom-up, consultative aspect of the PRF is perhaps most strongly resonant with the enablement of agency, through influence to some degree over what activities are undertaken and how, and hence the allocation of resources. This is because the PRF is ostensibly designed to allow autonomous proposals of local needs by villagers for higher authorities to consider and respond to with funding, thereby presenting a form of vertical communication with decision-makers that is otherwise rare within existing governance hierarchies. Respondents at both sites referred to the village head appealing to the government for assistance in this way, and expressions of agency on the part of households might thus be viewed as being channeled via the local leaders. However, it should be noted that participating villages in the PRF select options from an externally predefined project “menu,” based on agreement between the government and the World Bank (GoL 2003), and the rules of resource allocation are thus to some extent remotely set within the project structure. This is confirmed in some aspects in village A), where respondents viewed district or project staff as disconnected from local reality, in that they could “only make the plan” from afar [A2]. Other village A) respondents considered “villagers” to be key actors in the first system, since it is they who undertake all activities in the village, though still considering themselves less influential overall than government staff or village leaders. Several respondents referred to a further expression of agency in the form of avoidance, by opting out of activities and meetings when other needs take precedence, particularly during peak labor periods when it was necessary to stay in the fields. Despite the apparently community-driven approach of the PRF, a sense of dependence on external actors as gatekeepers to project resources prevailed, reflected in statements such as “if there is not this project, our village would be poorer than now” [B17] and “we will not have this project if there is no one like [district official]” [B24]. In village A), the role of the head was considered paramount: “if we don’t have the head of the village [the project] is impossible” [A11]. Villagers who held the perception of being unable to participate whatsoever in such projects considered themselves barred by circumstance, one respondent stating that the household could not join “because I am just a regular villager and go to listen to them only . . . we are very poor and we don’t have anything to provide them” [B2]. These statements highlight the impact of localized structural conditions over the enablement versus disablement of respondents to influence the interventions that affect them, through the sense of self-reinforcing circumstances of poverty, and of prevailing dependence on institutional hierarchy, as similarly observed by Martin et al. (2018).

As a market-based structure, the clearest expression of agency within the maize contract system is through the business decisions that households are, on the surface, free to make—that is, whether to grow the crop or not, and if so for whom. However, the fact that most farmers enter contracts under credit conditions (typically for start-up capital, seasonal inputs, and construction of feeder roads by traders) means that apparent degrees of autonomy on the part of contract farmers may often quickly lead to conditions of dependency. This is consistent with research elsewhere in Houaphan province, which reveals how farmers are “often locked in relationships that they did not even choose” with traders, later becoming ensnared in a cycle of increasing inputs to compensate for degrading land, with farmers struggling to repay production costs and loans (Vagneron and Kousonsavath 2015, 6–10). A further layer of this dependency was evident in the importance attached to external actors in connecting farmers to the Vietnamese market: “Vietnamese businessmen started this project and come to buy, so this is the most significant encouragement to grow more maize” [A9]. With this said, most participants were directly aware of different local traders, and there was evidence in both villages of switching to new contracts where others had proven untrustworthy (particularly by reneging on agreed prices). While almost all households were active participants in the system, some had nonetheless decided to opt out, one farmer stating that “I don’t connect with the maize project, and they don’t know about me either” [B14]. As with the PRF, the role of local institutional structures was evidenced by perceptions of the village head’s importance, and the dependency within this relationship: “if the village head allows, we can do, if he doesn’t want us to do we won’t, if we don’t listen to him, if something happens he won’t be responsible for us” [B33]. Village A) respondents generally considered this in a more enabling light, that the village head “leads the people to change their occupation, to make progress to help themselves” [A9]. Agency could be seen as enabled in various ways through the maize contract system, particularly improving income and living standards, though as has proven the case elsewhere in Houaphan province at the time (Martin et al. 2018), the benefits were short-lived, while the impacts on the land were a source of concern for most respondents. In a broader sense, the historically bound nature of land regimes in both villages acted as a filter through which differentiated access to land for cultivation resulted in uneven economic outcomes among farmers. Agency-enabling aspects of maize production should therefore be carefully considered against a backdrop of economic precarity, with contracting rules governed by external actors, and geographical constraints over market access.

As the more top-down and restrictive of the three systems, for many respondents, participation in NEPL-NPA mostly involved attending meetings and following instructions, echoing the findings of Martin et al., who observed “consistent evidence that the district government came to inform, rather than to engage in discussion about the formation of the NPA” (ibid., 99). Perceptions ranged from having a personal stake (“we have to take care of the forest surrounding our village” [B11]), to simple obligation (“I have to do whatever they said” [B9]). Participation in NPA activities was described by one respondent as follows: “agriculturalists and foreigners come to our village for inspecting, to survey the area that they want and the head of the village informed the villagers by telling them to go and survey with them” [B12]. While the emphasis among these statements is firmly on households acting in accordance with institutional structures, as opposed to having a role in shaping policies that affect them, some respondents also considered villagers as influential actors in organizing and undertaking activities. Others presented the NPA staff in a more enabling light as “teaching” villagers the advantages and benefits of maintaining the forest; albeit often at the same time as advising, announcing, or “warning” people to protect it: “they come to control the protected area of the village” [B30]. As with the other two systems, the village head was once again the focal actor for many respondents, typified by statements that “I just know [about the NPA] by the head of the village” [B24]. For some, NEPL-NPA appeared to transcend any potential for individual involvement or influence, existing beyond “our responsibility, they just come here to advise and work with the village [leaders]” [B3], who would then counsel them to “accept the rules of protected forest. Those who don’t follow the rules will be fined and done with according to the government strategy” [A5]. As with the other systems, some ability to opt out of the NPA was suggested by those who considered themselves too busy tending crops to join activities or meetings. While forest communities in Laos have been observed to dispute state-sponsored enclosure of resources (Ingalls 2017) and elsewhere to reject participation in and benefits from government forest management activities to avoid legitimizing them (e.g. Myers and Muhajir 2015), it is perhaps a stretch to consider opting out in the studied case as such an exercise of agency, since this may often be a matter of simple pragmatism. Finally, although age and lack of education or ability to understand the project were stated as common barriers to participation in the NPA system, the same respondents stated that they already knew how to protect the forest. This points to separation between knowledge of the NPA as a project, perceived as out of the hands of respondents; and unspoken knowledge of the need to protect forest, that respondents may enact via everyday agency as a matter of course.

VI Conclusion

This article has applied a structure-agency lens to examine the experiences of marginal farm households in the northern Laos uplands of three distinct systems of resource allocation, the degree to which farmers may shape their engagement with the different systems, and how agency may be enabled or disabled by this engagement. This was explored via examining participation in and perceptions of decision processes and resulting actions, the nature of interactions between actors and ability to influence decisions within the three systems, and aspects of dependence and circumstances of non-participation. Our analytical approach has sought a nuanced understanding of people’s lived experiences of such interventions, thereby the everyday enablement or disablement of agency, with the aim of supporting policy that is better grounded in local realities while contributing to debates on participatory and inclusive development in the social sciences. The systems identified by respondents comprised livelihood development and poverty reduction projects, maize contract farming, and a national protected area, each reflecting in different ways how the influence and practices of different sets of actors are steered by deeply embedded structures (Leach et al., 2010).

In his influential structuration theory, Giddens depicts a “dialectic of control” through which “all forms of dependence offer some resources whereby those who are subordinate can influence the activities of their superiors” (1984, 16). The extent and nature of such resources offered through the studied systems is governed by local hierarchies and, in the case of the maize system, geographical isolation and economic constraint. Critically, in these examples of everyday experiences of development and environmental policies, it appears to remain firmly the norm that knowledge production and influence over highly impactful policy decisions remain in the ambit of external actors and experts (Simmons 2007), and restricted from incorporating local knowledge and practices by the nature of institutional structures and procedures. It is difficult to view the mode of delivery of information on forest management and conservation at the time of the research as one that might foster local agency, and by extension, an inclusive model (though some respondents viewed the flow of information more positively than others), and existing local conservation knowledge and practices are thus at risk of being overlooked. On the other hand, the vocal desire among some respondents for a stronger local role in forest conservation is indicative that alternative approaches are possible, given enabling structural conditions. These conditions would first need to include varied platforms to capture the diversity of local voices in adapting, contributing to, or opposing interventions. In parallel, stronger recognition of the existing exercise of local agency in everyday livelihood practices, together with the removal of agency-disabling barriers, would allow for more direct involvement by marginal forest communities in policy processes.

The findings of this study contribute to a wider body of work on experiences of development in Southeast Asia by focusing on the nuances of agency and perceptions of participation and inclusion in decision processes relating to resource allocation in upland Laos. These perceptions, as expressed by respondents in remote upland communities, reflect both the structural and cultural constraints of institutional hierarchy and a willing dependence on external “patrons” in exchange for resources. Li (2001) argues that there are definite tracks of power in rural landscapes and livelihoods laid by previous laws, policies, and development interventions, such as in the rules of resource allocation and access to land we have described in the two study villages. Do the interventions we have examined, with the varied dependencies and differentiated enablement of agency they foster, reduce or reinforce forms of agrarian differentiation and inequality? Although our study provides only a starting point for such questions, we consider that a more nuanced sense of agency is critical for the design of inclusive and equitable policies, which can be developed through understanding people’s everyday experiences of the interventions that affect them.

Accepted: February 19, 2019

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted under the ASEAN-Swiss Partnership on Social Forestry and Climate Change (ASFCC), funded by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC). The research was undertaken in collaboration with the Department of Forestry, Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry of Laos, and Faculty of Forestry, National University of Laos. We are grateful to the directors and staff of our partner institutions for their support, to our respondents for sharing their time and insights, and reviewers for their constructive inputs. We thank Jean-Christophe Castella at Institute de Recherche pour le Développement for his contributions to the fieldwork, and Rasso Bernhard at the Laos country office of the Centre for Development and Environment, Bern University, for producing the map. Grace Y. Wong is supported by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency-funded GRAID program at the Stockholm Resilience Centre. Robert Cole greatly appreciated a research attachment with the Center for Southeast Asian Studies at Kyoto University while preparing the manuscript.

References

Agarwal, B. 2001. Participatory Exclusions, Community Forestry and Gender: An Analysis for South Asia and a Conceptual Framework. World Development 29(10): 1623–1648.

Baird, I. G. 2011. Turning Land into Capital, Turning People into Labour: Primitive Accumulation and the Arrival of Large-Scale Economic Land Concessions in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic. New Proposals: Journal of Marxism and Interdisciplinary Inquiry 5(1): 10–26.

Baird, I. G.; and Shoemaker, B. 2007. Unsettling Experiences: Internal Resettlement and International Aid Agencies in Laos. Development and Change 38(5): 865–888.

Bourdet, Y. 2000. The Economics of Transition in Laos: From Socialism to ASEAN Integration. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Brockhaus, M.; Di Gregorio, M.; and Carmenta, R. 2014a. REDD+ Policy Networks: Exploring Actors and Power Structures in an Emerging Policy Domain. Ecology and Society 19(4): 29.

Brockhaus, M.; Di Gregorio, M.; and Mardiah, S. 2014b. Governing the Design of National REDD+: An Analysis of the Power of Agency. Forest Policy and Economics 49: 23–33.

Brown, K.; and Westaway, E. 2011. Agency, Capacity, and Resilience to Environmental Change: Lessons from Human Development, Well-Being and Disasters. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 36: 321–342.

Brown, M.; and Zasloff, J. J. 1986. Apprentice Revolutionaries: The Communist Movement in Laos, 1930–1985. Stanford: Hoover Institution Press.

Caouette, D.; and Turner, S. 2009. Agrarian Angst and Resistance in Contemporary Southeast Asia. Oxford: Routledge.

Castella, J.-C.; and Bouahom, B. 2014. Farmer Cooperatives Are the Missing Link to Meet Market Demands in Laos. Development in Practice 24(2): 185–198.

Castella, J.-C.; Lestrelin, G.; Hett, C.; Bourgoin, J.; Fitriana, Y. R.; Heinimann, A.; and Pfund, J.-L. 2013. Effects of Landscape Segregation on Livelihood Vulnerability: Moving from Extensive Shifting Cultivation to Rotational Agriculture and Natural Forests in Northern Laos. Human Ecology 41: 63–76.

Cole, R.; and Ingalls, M. L. (Forthcoming). Rural Revolutions: Socialist, Market and Sustainable Development of the Countryside in Vietnam and Laos. In The Socialist Market Economy in Asia: Development in China, Vietnam and Laos, edited by A. Hansen, J. I. Bekkevold, and K. Nordhaug. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cole, R.; Wong, G.; Brockhaus, M.; Moeliono, M.; and Kallio, M. 2017a. Objectives, Ownership and Engagement in Lao PDR’s REDD+ Policy Landscape. Geoforum 83: 91–100.

Cole, R.; Wong, G.; and Bong, I. W. 2017b. Implications of the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) for Transboundary Agricultural Commodities, Forests and Smallholder Farmers. Infobrief 178. Bogor: Center for International Forestry Research.

Colfer, C. J. P.; and Capistrano, D., eds. 2005. The Politics of Decentralization: Forests, Power and People. London: Earthscan.

De Koning, M.; Nguyen, T.; Lockwood, M.; Sengchanthavong, S.; and Phommasane, S. 2017. Collaborative Governance of Protected Areas: Success Factors and Prospects for Hin Nam No National Protected Area, Central Laos. Conservation and Society 15(1): 87–99.

Drahmoune, F. 2013. Agrarian Transitions, Rural Resistance and Peasant Politics in Southeast Asia. Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs 32(1): 111–139.

Emirbayer, M.; and Mische, A. 1998. What Is Agency? The American Journal of Sociology 103(4): 962–1023.

Evans, G. 1995. Lao Peasants under Socialism and Post-Socialism. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books.

―. 1988. Agrarian Change in Communist Laos. Occasional paper No. 85. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Évrard, O. 2011. Oral Histories of Livelihoods and Migration under Socialism and Post-Socialism among the Khmu of Northern Laos. In Moving Mountains: Ethnicity and Livelihoods in Highland China, Vietnam and Laos, edited by J. Michaud and T. Forsyth, pp. 76–99. Vancouver: UBC Press.

Évrard, O.; and Baird, I. G. 2017. The Political Ecology of Upland/Lowland Relationships in Laos since 1975. In Changing Lives in Laos: Society, Politics and Culture in a Post-Socialist State, edited by V. Bouté and V. Pholsena, pp. 165–191. Singapore: NUS Press.

Évrard, O.; and Goudineau, Y. 2004. Planned Resettlement, Unexpected Migrations and Cultural Trauma in Laos. Development and Change 35(5): 937–962.

Forsyth, T. 2009. The Persistence of Resistance: Analysing Responses to Agrarian Change in Southeast Asia. In Agrarian Angst and Resistance in Contemporary Southeast Asia, edited by D. Caouette and S. Turner, pp. 267–276. Oxford: Routledge.

Friend, R. M.; and Blake, D. J. H. 2009. Negotiating Trade-Offs in Water Resources Development in the Mekong Basin: Implications for Fisheries and Fishery-Based Livelihoods. Water Policy 2(1): 13–30.

Gallemore, C. T.; Dini Prasti H. R.; and Moeliono, M. 2014. Discursive Barriers and Cross-Scale Forest Governance in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Ecology and Society 19(2): 18–30.

Galvin, M.; and Haller, T., eds. 2008. People, Protected Areas and Global Change: Participatory Conservation in Latin America, Africa, Asia and Europe. Perspectives of the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR) North-South, University of Bern, Vol. 3. Bern: Geographica Bernensia.

Giddens, A. 1984. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Government of Lao PDR (GoL). 2003. The Poverty Reduction Fund Manual of Operations. Government of Lao PDR, Vientiane.

Hall, R.; Edelman, M.; Borras, S. M. Jr.; Scoones, I.; White, B.; and Wolford, W. 2015. Resistance, Acquiescence or Incorporation? An Introduction to Land Grabbing and Political Reactions ‘From Below’. Journal of Peasant Studies 42(3-4): 467–488.

Hart, G. P.; Turton, A.; and White, B. 1989. Agrarian Transformations: Local Processes and the State in Southeast Asia. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Heinimann, A.; Hett, C.; Hurni, K.; Messerli, P.; Epprecht, M.; Jørgensen, L.; and Breu, T. 2013. Socio-economic Perspectives on Shifting Cultivation Landscapes in Northern Laos. Human Ecology 41(1): 51–62.

Hett, C.; Castella, J.-C.; Heinimann, A.; Messerli, P.; and Pfund, J.-L. 2011. A Landscape Mosaics Approach for Characterizing Swidden Systems from a REDD+ Perspective. Applied Geography 32: 608–618.

High, H. 2014. Fields of Desire: Poverty and Policy in Laos. Singapore: NUS Press.

Hojman, D. A.; and Miranda, Á. 2017. Agency, Human Dignity and Subjective Well-Being. World Development 101: 1–15.

Ibrahim, S.; and Alkire, S. 2007. Agency and Empowerment: A Proposal for Internationally Comparable Indicators. Oxford Development Studies 35(4): 379–403.

Ingalls, M. L. 2017. Not Just Another Variable: Untangling the Spatialities of Power in Social-Ecological Systems. Ecology and Society 22(3): 20–34.

Ingalls, M. L.; Diepart, J.-C.; Truong, N.; Hayward, D.; Neil, T.; Phomphakdy, C.; Bernhard, R.; Fogarizzu, S.; Epprecht, M.; Nanhthavong, V.; Vo, D. H.; Nguyen, D.; Nguyen, P. A.; Saphangthong, T.; Inthavong, C.; Hett, C.; and Tagliarino, N. 2018a. State of Land in the Mekong Region. Centre for Development and Environment, University of Bern and Mekong Region Land Governance. Bern, Switzerland and Vientiane, Lao PDR: Bern Open Publishing.

Ingalls, M. L.; Meyfroidt, P.; To, P. X.; Kenney-Lazar, M.; and Epprecht, M. 2018b. The Transboundary Displacement of Deforestation under REDD+: Problematic Intersections between the Trade of Forest-Risk Commodities and Land Grabbing in the Mekong Region. Global Environmental Change 50: 255–267.

Islam, K. K.; Jose, S.; Tani, M.; Hyakumura, K.; Krott, M.; and Sato, N. 2015. Does Actor Power Impede Outcomes in Participatory Agroforestry Approach? Evidence from Sal Forests Area, Bangladesh. Agroforestry Systems 89: 885–899.

Kabeer, N. 1999. Resources, Agency, Achievements: Reflections on the Measurement of Women’s Empowerment. Development and Change 30: 435–464.

Kallio, M. H.; Hogarth, N. J.; Moeliono, M.; Brockhaus, M.; Cole, R.; Bong, I. W.; and Wong, G. Y. 2018. The Colour of Maize: Visions of Green Growth and Farmers’ Perceptions in Northern Laos. Land Use Policy 80: 185–194.

Kallio, M. H.; Moeliono, M.; Maharani, C.; Brockhaus, M.; Hogarth, N. J.; Daeli, W.; Tauhid, W.; and Wong, G. 2016. Information Exchange in Swidden Communities of West Kalimantan: Lessons for Designing REDD+. International Forestry Review 18(2): 203–217.

Kenney-Lazar, M. 2013. Shifting Cultivation in Laos: Transitions in Policy and Perspective. Report commissioned by the Secretariat of the Sector Working Group for Agriculture and Rural Development of Lao PDR, Vientiane.

Kerkvliet, B. J. T. 2005. The Power of Everyday Politics: How Vietnamese Peasants Transformed National Policy. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Leach, M.; Scoones, I.; and Stirling, A. 2010. Dynamic Sustainabilities: Technology, Environment, Social Justice. London and New York: Earthscan.

Lestrelin, G.; and Giordano, M. 2007. Upland Development Policy, Livelihood Change and Land Degradation: Interactions from a Laotian Village. Land Degradation and Development 18: 55–76.

Li, T. M. 2001. Agrarian Differentiation and the Limits of Natural Resource Management in Upland Southeast Asia. IDS Bulletin 32(4): 88–94.

Loyal, S.; and Barnes, B. 2001. “Agency” as a Red Herring in Social Theory. Philosophy of the Social Sciences 31(4): 507–524.

Martin, A.; Myers, R.; and Dawson, N. M. 2018. The Park Is Ruining Our Livelihoods. We Support the Park! Unravelling the Paradox of Attitudes to Protected Areas. Human Ecology 46: 93–105.

Michaud, J.; and Forsyth, T., eds. 2011. Moving Mountains: Ethnicity and Livelihoods in Highland China, Vietnam and Laos. Vancouver: UBC Press.

Myers, R.; and Muhajir, M. 2015. Searching for Justice: Rights vs. “Benefits” in Bukit Baka Bukit Raya National Park, Indonesia. Conservation and Society 13(4): 370–381.

Parkins, J. R.; and Mitchell, R. E. 2005. Public Participation as Public Debate: A Deliberative Turn in Natural Resource Management. Society & Natural Resources 18(6): 529–540.

Pholsena, V.; and Banomyong, R. 2006. Laos: From Buffer State to Crossroads? Chiang Mai: Mekong Press.