Advance Publication

Accepted: October 8, 2024

Published online: November 5, 2025

Contents>> Vol. 14, No. 3

Marriage Migration in Tan Loc (Vietnam): Transformations and Considerations

Phạm Thị Binh*

*Department of Geography, Ho Chi Minh City University of Education (HCMUE), 280 An Duong Vuong, Ho Chi Minh City District 5, 700000, Viet Nam

e-mail: binhpt[at]hcmue.edu.vn

![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7081-4294

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7081-4294

DOI: 10.20495/seas.25008

Browse “Advance online publication” version

There has been abundant research on marriage migration from the perspective of the receiving side, but research from the perspective of sending countries is limited. This paper investigates transformations in the sending community of Tan Loc, Vietnam, an island greatly affected by international marriage migration over the last three decades. The results of an analysis of empirical data collected from field surveys in 2019, 2020, and 2022 reveal transformations in Tan Loc, such as economic improvement, changes in social values, new pathways of labor migration, and issues related to returned marriage migrants. The mechanism of marriage migration in Tan Loc today is different from the way it was from the 1980s to the 2000s. This may be the case in other sending communities as well. Thus, such transformations on both sending and receiving sides need to be addressed in scientific research.

Keywords: marriage migration, transformation, sending community, Tan Loc, Vietnam

1 Introduction

In contemporary Asia, the increasing number of female migrants is closely related to the need for foreign wives in developed countries. Some of the source countries are the Philippines, China, Thailand, and Vietnam. The receiving countries are usually Taiwan, Korea, and Japan. Due to a “bride shortage” in the latter countries, many rural men are forced to wed foreign wives via brokers. Thus, international marriage migration is most common between men and women of low socioeconomic status (Wang and Chang 2002; Kamiya and Lee 2009; Kawaguchi and Lee 2012; Pham et al. 2013).

Female migration for marriage, or “marriage migration,” has become an important research issue in destination countries due to resultant problems involving the settlement, adaptation, contribution, and integration of foreign wives and their mixed children. In order to maintain socioeconomic stability, receiving states devote great efforts toward helping foreign wives with the settling-in process. Various relevant campaigns and projects have been launched in Japan, Taiwan, and Korea. Meanwhile, issues caused by marriage migration in countries of origin have received little attention.

From the perspective of the receiving side, abundant studies have been carried out to find ways of supporting foreign wives, clarifying their reality after migration (Pham et al. 2013), helping multicultural families, maintaining social stability while integrating the role of foreign wives (Piper 2003; Kim 2011; Yang 2011), investigating the challenges of getting citizenship (Tuen and Yeoh 2021), comparing the adaptation of different groups of foreign wives, explaining the connection between countries of origin and destination (Vu and Lee 2012), investigating the inclusion/exclusion of foreign wives and their mixed children (Kim 2011), exploring the role of ethnicity in international couples (Ahsan and Chattoraj 2023), etc.

Migrant wives (whether they return to their home countries or settle down in the destination) become a link between the origin and receiving sides. They play an important role in developing and maintaining social networks between the two sides. They also influence local attitudes toward international marriage migration. Therefore, analysis from the view of the sending side helps to clarify the linkages as well as the push and pull factors of ongoing marriage migration flows. Without such analysis, inflows to specific destinations cannot be fully explained and views on international marriage migration at the macro level would be incomprehensive. This gap needs to be filled by doing more empirical research in sending communities to clarify the mechanism of international marriage migration globally. This paper tries to fill the void in the literature on marriage migration studies by answering the following research question: What transformations are caused by outmigration from Tan Loc?

This study investigates social changes resulting from international marriage migration within a specific geographical and national boundary—the mechanism of the push and pull factors of the first phase (via brokers, or marriage-led migration) and the second phase (via social networks, including marriage-led mobilization and migration-led mobilization). The push and pull theory is applied to analyze transformations in the sending community and ongoing migration from the community. Such international outflows are explained and viewed from a geographical perspective.

2 Outmigration for International Marriage in Vietnam

International marriages are nothing new in Vietnam. However, marriages via brokers and motivated by economic reasons began and increased rapidly after Doi Moi, or the country’s opening up in 1986. The phenomenon was first observed in the Mekong Delta region and soon became popular in rural areas around the country. Due to Vietnam’s close socioeconomic relationship with Taiwan in the 1980s and the idolization of Korean men via Korean film stars, most of the international marriages were between Vietnamese women and Taiwanese and Korean men. The first wave of marriage migration was to Taiwan, from 1986 to the late 2000s. After that, the migration flow shifted largely to Korea: from 2005 to 2019 there was a sharp increase in the number of Vietnamese women marrying Korean men. By 2019 the number of Vietnamese brides in Korea was about 180,000, accounting for 38.5 percent of foreign brides and the largest foreign brides’ group in the country. According to the Vietnam Ministry of Justice (2019), between 1995 and 2019 a total of 393,570 Vietnamese women were married to foreigners; 90 percent of them were from rural areas, and 83 percent were married via brokers. Their main destinations included Korea, Taiwan, the United States, China, Singapore, and Malaysia.

In general, marriage outmigration of Vietnamese women can be explained by the following reasons: the influence of Vietnam’s “open policy,” the operation of marriage brokers, and economic motives (Pham et al. 2013). Today Vietnam is one of the major sources of marriage migrants in Asia, just after China and the Philippines.

The primary motivation for most Vietnamese female marriage migrants is to send remittances back their natal families. Bélanger and Tran (2011) concluded that altruism theory could explain why some Vietnamese women chose to marry foreigners—to show gratitude and alleviate their family’s poverty. And after migration, most of them remitted funds to their natal families (Park et al. 2012). Their remittances motivated young girls in the sending communities to do the same thing, which created momentum for a wave of migration in rural Vietnam. The first and biggest source of marriage migrants in Vietnam is the Mekong Delta region, particularly Can Tho (Nguyen and Tran 2010). In fact, Tan Loc island (part of Can Tho city) was called the Taiwanese island and then the Korean island because of the great number of women from here who got married to Taiwanese and Korean nationals.

The Mekong Delta is one of the three regions in Vietnam with the lowest levels of education and literacy. In economically disadvantaged rural areas of this region, families often have many children. They marry off the daughters as soon as they can, allowing the sons to continue with their education. With low education and limited understanding, these girls easily accept both domestic arranged marriages as well as international marriages via brokers.

The wave of migration for marriage via brokers in the Mekong Delta from the 1980s to 2000s has attracted public and scientific attention. In contrast, marriage outflows via social networks (such as relatives and friends) have attracted less notice. Previous studies viewed Vietnamese marriage migrants as poor, uneducated girls migrating for money (marriage-led migration). That may have been true in the past, but it is not necessarily the case today. Modern girls are proactive in taking charge of their future and actively plan for marriage (migration-led marriage). This change needs to be reflected in research.

The waves of international marriage had a great impact on sending communities of the Mekong Delta—especially Can Tho city, since this has had the region’s largest number of marriage migrants over the last three decades. Thus, I carried out field surveys in 2019, 2020, and 2022 in Tan Loc commune (which is on Tan Loc island, Thot Not District, Can Tho city) to collect empirical data on economic changes, social transformations, new forms of labor migration, emerging issues of returned migrants and their mixed children, etc. By investigating a case study in Tan Loc, this paper calls attention to continual outmigration from developing to developed countries, focusing on the relationship between marriage migration and transformations in sending communities.

3 Research Site: Tan Loc Island

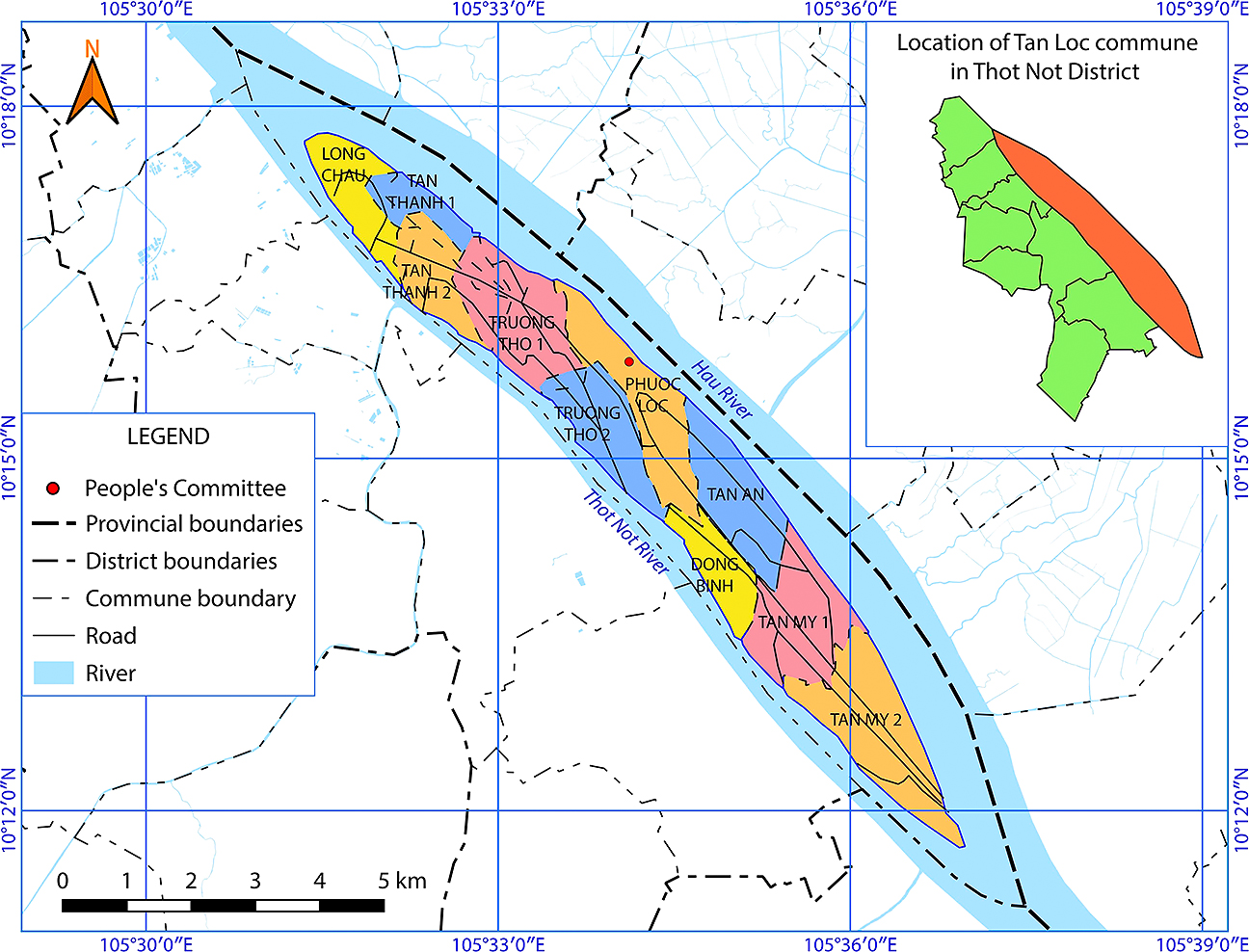

The research site for this study was Tan Loc island (Fig. 1). This island, with an area of 32.68 km2 and a population of around 30,595, is part of Thot Not District in Can Tho city. It is located on the Hau River, one of the two main branches of the Mekong River. Tan Loc can be reached only by ferry or boat, and most of its residents depend on farming for a livelihood.

The trend of migrating for marriage started in Tan Loc in the 1990s. About 80 percent of families on the island have daughters married to foreigners—mainly to Taiwanese before 2005 and Korean men after that. The living conditions of migrant families have improved, partly thanks to remittances from migrant daughters. Most of the marriage migrants are young, with a low education level, and from poor families.

In Tan Loc, the percentage of women married to Taiwanese men decreased from around 80 percent in the 1990s to 50 percent in the 2000s and 20 percent in the 2010s. In contrast, the percentage of women married to Korean nationals increased from around 40 percent in the 2000s to 70 percent in the 2010s. Table 1 shows that marriages to Korean men peaked in 2010, partly due to the ease of legal procedures and Korean men paying large sums of money for marriage tours.

Table 1 Number of Migrants Due to Marriage to Korean Nationals

| Year | Vietnam | Can Tho | Tan Loc |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 560 | 34 | 0 |

| 2005 | 1,030 | 379 | 60 |

| 2006 | 7,853 | 700 | 250 |

| 2010 | 8,425 | 635 | 157 |

| 2011 | 6,957 | 732 | 135 |

| 2012 | 6,343 | 856 | 112 |

| 2013 | 6,066 | 943 | 98 |

| 2014 | 4,374 | 658 | 78 |

| 2015 | 4,158 | 616 | 57 |

| 2016 | 1,492 | 212 | 38 |

4 Data and Methodology

To collect empirical data, in-depth interviews and convenience sampling were used. Thus, small sample size and sampling bias are limitations of this study. In December 2019 in-depth interviews were carried out with nine families whose daughters had migrated for marriage. Because one family had three daughters married to Taiwanese and Korean men and one family had two daughters married to Taiwanese and Korean men, the total number of marriage migrants was 12. This group is hereafter called Group 1. In order to obtain more recent information on the trend of marrying foreign men on Tan Loc island, I returned to interview 35 young and unmarried girls in March 2020 (20 interviewees) and May 2022 (15 interviewees). This group is hereafter called Group 2. The samples are documented in Table 2.

Table 2 Details of Samples

| Group 1 | ||

| Year | Details | Number of Subjects |

| 2019 | 1 family | 3 migrants |

| 1 family | 2 migrants | |

| 7 families | 1 migrant per family | |

| Total | 12 migrant women | |

| Group 2 | ||

| 2020 | 10 families | 20 young girls |

| 2022 | 8 families | 15 young girls |

| Total | 35 young girls | |

Source: Surveys by Phạm Thị Binh (2019, 2020, 2022)

5 Results

5.1 Characteristics of Marriage Migrants in Group 1

Table 3 summarizes the general characteristics of the 12 marriage migrants in Group 1. In general, the migrants in this group are young, have a low education level (below junior high school), and worked poorly paid and unstable jobs in Vietnam. After migration, most of them are in a better economic situation (based on their own assessment).

Table 3 Profiles of Vietnamese Marriage Migrants in Group 1 (n = 12)

| Criterion | No./% | |

|---|---|---|

| Education | Primary | 3 (25%) |

| Junior | 7 (58%) | |

| Senior | 2 (17%) | |

| Marriage Age | 17–19 | 7 (58%) |

| 20–24 | 3 (25%) | |

| 25–29 | 2 (17%) | |

| Occupation Before Migration | Maidservant | 5 (42%) |

| Worker | 3 (25%) | |

| Farmer | 1 (8%) | |

| Selling* | 1 (8%) | |

| Others | 2 (17%) | |

| Occupation After Migration | Housewife | 6 (50%) |

| Worker | 3 (25%) | |

| Farmer | 2 (17%) | |

| Other | 1 (8%) | |

| Number of Children | 0 | 2 (17%) |

| 1 | 4 (33%) | |

| 2 | 6 (50%) | |

| Present Residence | Taiwan | 6 (50%) |

| Korea | 4 (33%) | |

| Vietnam | 2 (17%) | |

| Economic Situation After Marriage (Self-assessment) | Higher | 9 (75%) |

| Unchanged | 2 (17%) | |

| Lower | 1 (8%) | |

| Send Remittances | Yes | 8 (67%) |

| Not much/No | 4 (33%) | |

| Family Attitude | Supportive | 12 (100%) |

Source: Survey by Phạm Thị Binh (2019)

Notes: * Selling lottery tickets or peddling small items on the street.

After marriage, half the Vietnamese marriage migrants are housewives. Most of them have children and still live in the destination countries. About 75 percent of them believe that their economic situation has improved. However, only 67 percent remit funds to their natal families. To some extent, this figure corroborates the findings of previous studies that most natal families’ economic condition is improved thanks to the daughters’ remittances.

We now analyze the information collected via in-depth interviews with parents of cases 2, 3, and 4 (three migrants from the same family), cases 6 and 7 (two migrants from the same family), and case 8. The parents of cases 2, 3, and 4 (Group 1) were pleased and eager to share information on their daughters. The father said:

I am very happy and proud of my three daughters. They have money and can support us. They have bought everything in this house. We no longer have to work hard. The remittances from my daughters are more than we expected. I think we are lucky to have daughters. Especially my two daughters in Taiwan can remit money and visit us regularly, about twice a year. If I had one more daughter, I would suggest that she marry a foreign man.

The father expressed satisfaction and pride in his daughters. He supported his daughters in migrating for marriage. He considered himself lucky to have daughters. With the support of his three daughters, his only son was able to start a business producing cartons and open a coffee shop:

My family was so poor, we did not have enough rice for raising four children [three girls and a boy]. But now, we have everything. Next year I will buy a car for my son. He is now running a small carton factory and a coffee shop in Tan Loc.

The father noted that the attitudes of local residents toward his daughters’ migration were changing and becoming more positive. He was no longer accused of selling his daughters for money:

At first, we were accused of selling my daughters for money. But now many parents have followed us. They changed and thought about it openly. You see, there are girls marrying Vietnamese men, but they’re unhappy and so poor. My daughters are all lucky. So I feel comfortable now.

The parents of cases 6 and 7 (Group 1) said:

I wish I had more than two daughters. My two sons in Vietnam cannot help. My older daughter (living in a suburb of Taipei) works on her big farm, planting vegetables and fruit. My younger daughter married a Korean. She works in a factory (in Kyeongnam). They sometimes visit us. Their children are too small, and they are busy with farmwork as well as taking care of their parents-in-law. Farmwork in Taiwan is not as hard as in Vietnam. My daughter has to hire people to work on her big farm.

The father’s wish to have more daughters represents the shifting roles of children in his family, closely related to economic factors.

The parents of case 8 were pleased that the mother had a chance to work in Korea as a result of the daughter’s migration. The father said:

Things are much better since my daughter married a Korean man. I do not have to work hard. I just stay home to take care of my second daughter, who is 12 years old. My wife has the chance to work in Korea. She earns a lot of money. She often stays there six months for work. Next week she will go to Korea again. I will take care of the house.

The mother added:

First, I came to Korea to take care of my daughter’s baby. Then I took up a part-time job because I had free time. Now my husband encourages me to go to Korea for work again, like many other parents from here. My daughter can give a guarantee for my visa. I am happy. So, I am ready to go.

The parents of case 8 also demonstrate a new, safe, and free-of-charge pathway to migration for work via the connection of marriage migrants.

5.2 Potential Marriage Migrants in Group 2

Interview data show that the economic improvement of marriage migrant families inspires many young girls in Tan Loc to find their own ways of supporting their parents via international marriage—but differently. They have active plans for migration, as shown in the analysis below.

Table 4 presents the profiles of 35 young, unmarried girls hoping to migrate for marriage. The data was collected through in-depth interviews in 2020 and 2022.

Table 4 Profiles of Potential Marriage Migrants, Group 2 (n = 35)

| Criterion | No./% | |

|---|---|---|

| Education | Primary | 7 (20%) |

| Junior | 10 (28.5%) | |

| Senior | 15 (42.9%) | |

| Tertiary | 3 (8.6%) | |

| Age | 17–19 | 21 (60%) |

| 20–24 | 6 (17%) | |

| 25–29 | 8 (23%) | |

| Occupation | Maidservant | 7 (20%) |

| Worker | 10 (28.5%) | |

| Farmer | 3 (8.6%) | |

| Student | 15 (42.9%) | |

| Expectation to Migrate for Marriage | Expect | 19 (54.3%) |

| Hesitate | 16 (45.7%) | |

Source: Surveys by Phạm Thị Binh (2020, 2022)

Table 4 shows that more than half the young girls expect to migrate for marriage. They are relatively well educated: more than half of them (51.5 percent) have a high school and tertiary education, 20 percent have completed only primary school, and almost half the respondents were students at the time of the survey.

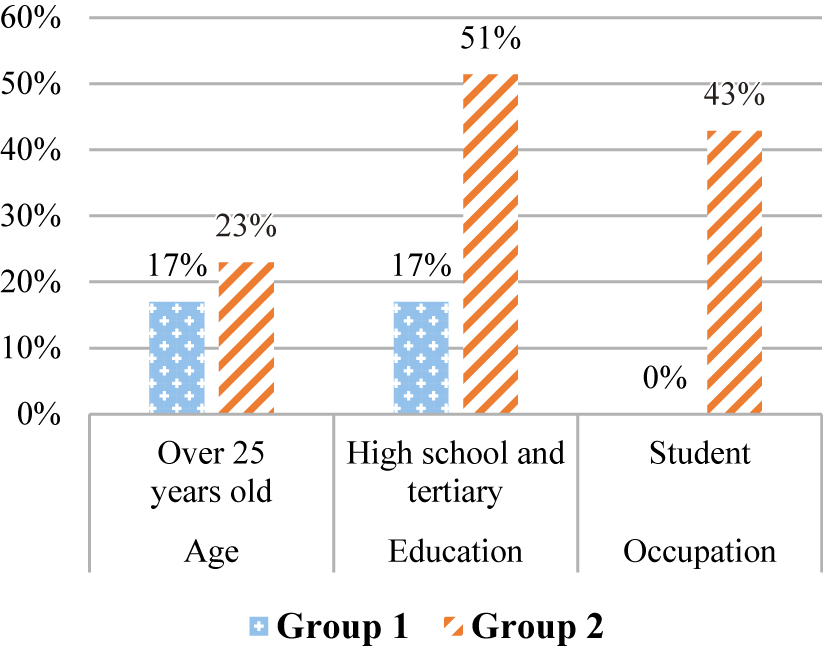

Fig. 2 shows the differences between the two groups in terms of age, education level, and occupation. Migrants in Group 1 are younger (83 percent under 25 years old), they are less educated (83 percent secondary school and lower), and none of them are students. In contrast, the Group 2 girls are a little older (77 percent under 25 years old) but better educated (about 50 percent secondary school and lower). And nearly half of them were students in universities in the Mekong Delta region at the time of the surveys.

One of the girls, Ngan (Group 2), said:

I will get a Korean certificate (aim for Topik 3) after finishing high school. Then I will have a good chance of marrying a Korean man, like my two cousins. They have a good life in Korea, much better than in Vietnam. They can even bring their mum, dad, and siblings to Korea for work. That sounds great. I hope to do the same.

Upon being asked why she had not chosen Taiwan, Ngan replied:

There are two reasons. The first is the language; it is more difficult to learn. The second is the fear of Taiwanese men. Near my home there are two returned cases who were married to Taiwanese men in 2000. After five years, they returned to Vietnam. One migrant returned alone. She soon got remarried to a Korean. The other migrant was accompanied by her two-year-old daughter. She faced a lot of difficulties. People looked down on her. She left her daughter in Vietnam and moved to Korea after remarrying a Korean man. Last year she brought her daughter (19 years old) to Korea, also for marriage.

Another girl, Ba (Group 2), expressed her own thinking:

My aim is to go to Korea. I am learning Korean now. To me, Korea is better than Taiwan. I have seen that migrants in Korea can remit much more to their parents than those in Taiwan. More important, it is easier to take relatives to Korea for work with a higher salary.

Ba seems to be actively making her own plans for migration. When asked how she obtained information on Korea, Ba replied:

I chat with my close friend regularly via Facebook, and I know that her life in Korea is good and safe. She advised me to finish high school and study Korean. People with a low education level and who are poor at Korean like her (secondary) cannot quickly get citizenship, and it is not easy to get a job or higher education in Korea.

Ba mentioned her parents’ support:

They support me, like many other parents here. You see, most parents who receive money from their migrant daughters do not want to work hard like before. Their land is on rent, and they go to Korea for work. Isn’t that much better?

Ut Em, one of the girls in Group 2 who hesitated to migrate for marriage, said:

I sometimes want to migrate to Korea through marriage. However, I also think of migrating to Korea for studying, like one of my friends. So, I am learning Korean. I hope to get my Topik 4 certificate this year. One of my friends went to Korea to study, and after some time she got married to a Korean man. She works as a nurse in a hospital. Her husband is a doctor. To me, they are so rich.

The above cases indicate that there may soon be a tendency toward migration-led marriage in Tan Loc as well as other sending places.

Table 5 shows the differences between the two groups. Unlike Group 1, the young girls in Group 2 have a variety of aims and make active preparations before migrating. This not only represents their greater control over the future but also implies a change in the migration trend, from marriage-led mobility to migration-led mobility.

Table 5 Differences between the Two Groups

| Group 1 | Group 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Younger | Older |

| Education | Lower | Much higher |

| Aim | Money | Better service, better employment, economic betterment |

| Preparation | Passive (limited information) | Active (better language, higher education, connection with friends/relatives in the destination, more information) |

| Marriage Pathway | Via broker | Via social networks (friends, relatives) |

Source: Surveys by Phạm Thị Binh (2019, 2020, 2022)

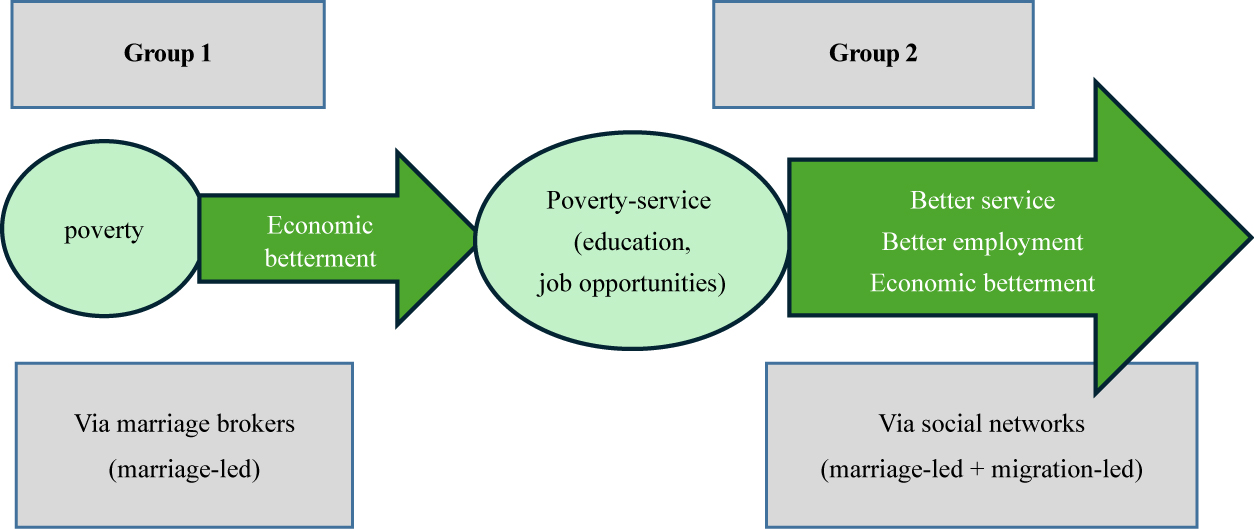

The push and pull factors for marriage outmigration among the two groups in Tan Loc are different, as discussed below (Fig. 3). The Group 2 subjects have more aims, and they make active preparations and take control of their migration strategy. This reflects a change from marriage-led to migration-led mobility.

Fig. 3 Push-Pull Factors for Outmigration of Both Groups on Tan Loc Island

Source: Surveys by Phạm Thị Binh (2019, 2020, 2022)

6 Discussion

Data collected from the interviews show the following socioeconomic transformations in Tan Loc: economic improvement of natal families, changing attitudes of local people, the development of migration networks, a new form of labor migration, changing social values, and emerging issues involving returned marriage migrants and their mixed children. The mechanism of these transformations is heavily impacted by economic factors, both directly and indirectly.

6.1 Improvement of Economic Conditions

The 12 cases in Group 1 agree that marriage migration is one way to reduce poverty in rural areas of Vietnam, as concluded by Nguyen and Tran (2010), Le et al. (2012), and Pham et al. (2013). This also explains why in economically disadvantaged rural areas the number of women marrying foreign men continues to increase (Nguyen and Tran 2010; Hoang 2013; Pham et al. 2013). And the economic improvement of certain families in Tan Loc not only changes local people’s attitude and behavior but also encourages young girls to make their own plans to migrate for marriage.

6.2 Changing Attitudes and Behavior

Changes in the Tan Loc community include changes in attitudes and behavior (Table 6).

Table 6 Contrasts in Attitude and Behavior

| Parties | In the Past | At Present | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | Migrant women, prospective migrants | Passive, unrealistic ideas | Active, realistic |

| Family members | Expect, urge | Encourage | |

| Communities | Criticize | Accept and praise | |

| Behavior | Migrant women, prospective migrants | No preparation | Make their own decisions with careful preparation and strategy |

| Family members | Actively support | Agree | |

| Communities | Accuse parents | No longer accuse parents |

Source: Surveys by Phạm Thị Binh (2019, 2020, 2022)

Local attitudes toward international marriage migration have changed. In the past, parents marrying off their daughters to unknown men in foreign countries via brokers were accused of selling their daughters for money, leaving the future to chance. Gradually, as the phenomenon became more familiar and people saw the improved economic condition of migrants’ natal families, local people stopped criticizing the parents. Some parents of marriage migrants even became role models to emulate.

Formerly, one factor attracting Vietnamese migrants to Korea was the idolization of Korean film stars (Hoang 2013). However, this study’s survey results show that young girls have become more realistic. They do not have any illusions about foreign men and life overseas. Through their social networks they seek information from various sources. Many young girls still expect to migrate for marriage, but they do so with greater intention. They pursue higher education and work toward language proficiency so they can avoid the discomforts experienced by returnees and other cases. Their expectations derive from successful cases of marriage migrants in Tan Loc.

Sixteen-year-old Ngan is actively strategizing to follow her two cousins who married Korean nationals. This is different from what Nguyen and Tran (2010) found, that many young girls in the Mekong Delta region in the 2000s ended their schooling before the age of 16 and sought opportunities to become foreign wives. Today, young girls tend to aim for more education before marriage. Some make careful plans to study in Korea and later look for opportunities to get married.

6.3 Transformation of Social Values

There has been a transformation of gender roles within the family in Vietnam as a result of marriage migration. Daughters were generally viewed less favorably than sons: they were often uneducated and married off as soon as possible, after which they were expected to devote themselves to their husband’s family. But this has been changing. As Bélanger and Tran (2011) concluded, the motivation of migrant daughters was to send remittances to their parents to show their gratitude. All parents of migrants expected to receive remittances. The parents of cases 2, 3, and 4 expressed happiness and pride over their three daughters’ remittances. They emphasized the important role of their daughters in improving the family’s economic condition.

The parents of cases 6 and 7 demonstrated that parents in Tan Loc were gradually changing their minds about gender preference: the role and position of daughters had become more important, since daughters were able to support their natal family. These parents preferred daughters to sons. Such widespread thinking among local people could in the long term lead to gender imbalance at birth and adverse consequences in family and social relations. The results of the interviews (Group 2) also show the changing attitude toward children’s duties by gender among the young girls themselves, who expect to take on the role of supporting their parents in different ways after migration. For example, Ba expects to bring her relatives to Korea for work in addition to sending remittances.

6.4 Development of a Migration Network

An analysis of the 35 cases in Group 2 reveals that the prospect of remitting funds to natal families attracts young girls in Tan Loc to dream of a new and better life in foreign countries through marriage. However, the young girls are more active and realistic than girls of the past. After connecting with their relatives and friends in Korea, they make their own plans, decisions, and preparations. For example, instead of aiming just to send remittances, some young girls prepare for a long-term journey that involves getting dual citizenship after migration to guarantee their relatives the opportunity of working in the destination country. This is a safer strategy—migration-led rather than marriage-led. Thus, social networks play an important role in marriage migration in Tan Loc today, unlike the past mechanism of brokered marriages investigated by Wang and Chang (2002). Parents today seem more concerned about the quality of their daughters’ lives. They do not expect remittances immediately after migration, in contrast to the days of brokered marriages when parents were not bothered about the quality of their daughters’ post-migration lives and were interested only in remittances.

6.5 Development of a New Pathway for Labor Migration

Marriage migrants become a link between sending and receiving communities to promote the labor migration network. As mentioned with reference to case 8 (Group 1), the mother (in her 40s) migrates to Korea to work every six months to a year, depending on her visa status. In the beginning, case 8 used to send money back to Vietnam. However, after bringing her mother to Korea for work, she no longer needs to remit funds. The mother has been to Korea five times and can earn much more money there than in Vietnam. The family has built a new, big, and well-appointed villa-like house in Tan Loc.

Case 8 shows that marriage migrants can guarantee visas for their relatives (a long-term multiple-entry F-1-5 visa in the case of Korea) to enter destination countries and work. This new pathway is becoming more popular in families with marriage-migrant daughters. For parents or siblings of migrants, it is a legal, secure, and reliable option to get jobs in foreign countries without paying fees to agents or brokers and much better than labor migration. This is a new pathway of labor movement from sending to receiving countries, though it is not very visible or acknowledged in the literature on marriage migration.

6.6 Emerging Issues with Regard to Returned Migrants and Their Mixed Children

As shared by Ngan, the sending side is often faced with problems related to the return of female marriage migrants. Some returnees find a way to remigrate for marriage to Korea, leaving their mixed children in Vietnam. Before a daughter migrates for marriage, many families are criticized for selling the dignity of Vietnamese women, etc. Thus, returned marriage migrants find it difficult to settle back in the community. Community members look down on them and consider them to be failures. It is hard—perhaps impossible—for them to remarry a Vietnamese man. Their situation is even worse if they return with mixed children. Such mixed children could do with more support from local governments and communities. Future research needs to be done to devise solutions for supporting Vietnamese returnees and their mixed children, as mentioned by Kim et al. (2017).

7 Conclusion

The results of this study show various transformations in Tan Loc brought about through marriage migration: economic upliftment, changing social values and attitudes, the development of migration networks, new forms of labor migration, emerging issues concerning returnees, etc. Such changes in other sending communities are worth researching. The internet has made it easy for marriage migrants and people in source countries to connect via Facebook, Zalo, etc. It is necessary to apply migration network theory (focusing on both online and offline networks) to investigate the linkage between migrants’ social networks and outflows to destination countries. Moreover, there are issues faced by the sending side, such as problems with returnees and their mixed children, a new pathway of labor migration, etc. The contribution of receiving countries is needed to help with resolving such issues. This study provides a preliminary empirical investigation of the phenomenon. Further research is necessary to gain a comprehensive view of marriage migration, analyzing the phenomenon from both sides in order to understand international flows and the relationships between push and pull factors globally as well as regionally.

References

Ahsan Ulla, A.K.M. and Chattoraj, Diotima. 2023. International Marriage Migration: The Predicament of Culture and Its Negotiations. International Migration 61(6): 262–278. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.13172. back1

Bélanger, Danièle and Tran Giang Linh. 2011. The Impact of Transnational Migration on Gender and Marriage in Sending Communities of Vietnam. Current Sociology 59(1): 59–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392110385970. back1 back2

Hoang Ba Thinh. 2013. Vietnamese Women Marrying Korean Men and Societal Impacts: Case Studies in Dai Hop Commune, Kien Thuy District, Hai Phong City. Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies 2(8): 782–789. http://dx.doi.org/10.5901/ajis.2013.v2n8p782. back1 back2

Kamiya Hiroo and Lee Chul Woo. 2009. International Marriage Migrants to Rural Areas in South Korea and Japan: A Comparative Analysis. Geographical Review of Japan Series B 81(1): 60–67. https://doi.org/10.4157/geogrevjapanb.81.60. back1

Kawaguchi Daiji and Lee Soohyung. 2012. Brides for Sale: Cross-Border Marriages and Female Immigration. Working Paper 12-082, Harvard Business School. back1

Kim Hyun Mee; Park Shinhye; and Shukhertei, Ariun. 2017. Returning Home: Marriage Migrants’ Legal Precarity and the Experience of Divorce. Critical Asian Studies 49(1): 38–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/14672715.2016.1266679. back1

Kim Young Jeong. 2011. “Daughters-in-Law of Korea?” Policies and Discourse on Migration in South Korea. Working Paper No. 92, Centre on Migration, Policy, and Society, University of Oxford. back1 back2

Le Nguyen Doan Khoi; Nguyen Van Nhieu Em; and Nguyen Thi Bao Ngoc. 2012. Analysis of Socio-economic Efficiency of International Marriage: The Study of Vietnamese and Taiwanese/Korean Marriages in the Mekong River Delta. Can Tho University Journal of Sciences 24b: 190–198. back1

Nguyen Xoan and Tran Xuyen. 2010. Vietnamese-Taiwanese Marriages. In Asian Cross-Border Marriage Migration: Demographic Patterns and Social Issues, edited by Wen-Shan Yang and Melody Chia-Wen Lu, pp. 157–178. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. back1 back2 back3 back4

Park Soon Ho; Pham Binh; and Kamiya Hiroo. 2012. The Cognition of Vietnamese Women Marriage Migrants on the Economic Condition Change before and after Marriage. Journal of the Korean Association of Regional Geographer 18(3): 269–282. back1

Pham Thi Binh; Kamiya Hiroo; and Park Soon Ho. 2013. The Economic Conditions of Vietnamese Brides in Korea before and after Marriage. Geographical Sciences 68(2): 69–94. https://doi.org/10.20630/chirikagaku.68.2_69. back1 back2 back3 back4 back5

Piper, Nicola. 2003. Wife or Worker? Worker or Wife? Marriage and Cross-Border Migration in Contemporary Japan. International Journal of Population Geography 9: 457–469. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijpg.309. back1

Tuen Yi Chiu and Yeoh, Brenda S.A. 2021. Marriage Migration, Family and Citizenship in Asia. Citizenship Studies 25(7): 879–897. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2021.1968680. back1

Vietnam Ministry of Justice. 2019. Thông tin thống kê. Ministry of Justice. https://www.moj.gov.vn/cttk/chuyenmuc/Pages/thong-tin-thong-ke.aspx accessed September 4, 2025. back1 back2

Vu Hong Tien and Lee Tien-Tsung. 2012. Soap Operas as a Matchmaker: A Cultivation Analysis of the Effects of South Korean TV Dramas on Vietnamese Women’s Marital Intentions. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 90(2): 308–330. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699013482912. back1

Wang Hong-zen and Chang Shu-ming. 2002. The Commodification of International Marriages: Cross-Border Marriage Business in Taiwan and Viet Nam. International Migration 40(6): 93–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2435.00224. back1 back2

Yang Hyunah. 2011. “Multicultural Families” in South Korea: A Socio-legal Approach. North Carolina Journal of International Law and Commercial Regulation 37(1): 47–81. back1