Tracing Hồ Chí Minh’s Sojourn in Siam

Thanyathip Sripana*

* ธัญญาทิพย์ ศรีพนา, Institute of Asian Studies, Chulalongkorn University, Phyathai Road, Pathumwan, Bangkok 10800, Thailand

e-mail: sthanyat[at]hotmail.com

DOI: doi.org/10.20495/seas.2.3_527

Hồ Chí Minh, the Vietnamese revolutionary leader who sacrificed his life for his country’s independence, was in Siam from 1928–29 and briefly from March–April 1930. Siam was well placed to serve as an anti-colonial base for the Vietnamese fighting for independence in the west of central Vietnam, especially after the repression of the Chinese communists in Guangdong by Chiang Kai Shek in 1927. Northern Siam is connected to central Vietnam by land via Laos, while southern China is also accessible from Bangkok by sea routes.

Hồ Chí Minh arrived in Bangkok in 1928. He went to Ban Dong in Phichit and then to Udon Thani, Nong Khai, Sakon Nakhon, and Nakhon Phanom in the northeast of Siam. The paper studies when and how Hồ Chí Minh arrived in Siam; his mission there; the places he visited; and his activities during his sojourn. We also enquire how Hồ Chí Minh carried out his mission: who accompanied him in Siam; what pseudonyms he and his collaborators used; and what strategies he used to elude arrest by local authorities.

It cannot be denied that the instruction Hồ Chí Minh imparted to his compatriots during his stay contributed tremendously to the struggle for Vietnamese independence. By the end of the 1920s and the beginning of the 1930s, he had accomplished his task of reorganizing and strengthening the network, and educating the Vietnamese anti-colonial and revolutionary movement in Siam. In addition, he contributed to the founding of the communist party in the region, which was the task assigned to him by the Comintern.

Nonetheless, we should recognize that his mission in Siam was facilitated and supported by Đặng Thúc Hứa, who, prior to Hồ’s arrival, had gathered the Vietnamese into communities and set up several bases for long-term anti-colonial movements with the help of his compatriots.

Hồ Chí Minh’s presence in Siam has been commemorated by the Thai and Vietnamese through the Thai-Vietnamese Friendship Village and the memorial houses built after 2000 in Nakhon Phanom and Udon Thani in northeastern Thailand. These memorials have become a symbol of the good relationship between Thailand and Vietnam.

Keywords: Hồ Chí Minh in Siam, Hồ Chí Minh’s sojourn in Siam, Hồ Chí Minh in Nakhon Phanom, Hồ Chí Minh’s pseudonym in Siam, Đặng Thúc Hứa, Đặng Quỳnh Anh, Việt Kiều in Thailand, Hồ Chí Minh’s memorial houses in Thailand, Vietnamese anti-colonial movement in Siam

Hồ Chí Minh1) was a Vietnamese revolutionary leader who sacrificed his life for Vietnam’s independence. He left Vietnam for the first time in 1911 on a French steamer Amiral Latouche-Tréville in order to canvas support for the fight. He visited and stayed in many countries before arriving in Siam. Hồ Chí Minh was in Siam from 1928–29 and briefly in March and April 1930. Hồ Chí Minh did not just stay in Siam but also crossed the Mekong river to briefly meet the Vietnamese in Laos in order to learn about the resistance against the French and assist in the setting up of the Vietnamese Revolutionary Youth League in Laos.

As Hồ Chí Minh’s mission in Siam was confidential, there is very little information regarding his activities. However, multiple sources exist that shed light on his sojourn. These include the memoirs of his revolutionary compatriots who worked closely with him during his mission; interviews given by people whose family member worked or travelled with him or who lived in the same house in Siam; discussions with the Vietnamese scholars at the Museum of Hồ Chí Minh in Hanoi; documentary films produced by the museum; as well as discussions with elderly Vietnamese who used to live in Thailand2) and with Việt Kiều3) who are still living in Thailand.

The memoirs, considered primary sources, contain much precious informative and have been used by many writers, Vietnamese and foreigners. They include Giọt Nước trong Biển Cả (Hồi Ký Cách Mạng) [A drop in the Ocean: Hoàng Văn Hoan’s revolutionary reminiscences] by Hoàng Văn Hoan; Cuộc Vận Động Cứu Quốc Của Việt kiều ở Thái Lan [The patriotic mobilization of the overseas Vietnamese in Thailand] by Lê Mạnh Trinh, etc. These two memoirs may be slightly contradictory on the dates of some events as they were written years after the end of the 1920s, but this is easily clarified by cross-checking various documents. Some other Vietnamese books that made use of these memoirs also reproduced minor mistakes regarding the name of places in Thailand. Another notable source is Con Người và Con Đường [People and pathways] by Sơn Tùng, based on his interview of the revolutionary Đặng Quỳnh Anh, who resided and participated in the anti-colonial and revolutionary movement in Siam or Thailand from 1913–53. The book provides invaluable details about the role of the Vietnamese émigrés in the salvation of their homeland from the French, as well as Hồ Chí Minh’s activities at Ban Dong (บ้านดง), in Phichit (พิจิตร). As Hồ Chí Minh stayed in her house in Ban Dong for a while before leaving for Udon Thani (อุดรธานี), briefly called Udon (อุดรฯ), and Võ Tùng, her husband worked closely with Hồ Chí Minh, she came to know about Hồ Chí Minh’s whereabouts and activities while he was in Ban Dong and when he left Ban Dong for Udon. She did not know his true identity at that time but was very suspicious about his activities.

Hồ Chí Minh Toàn Tập, an official 12-volume set of documents of the Vietnamese Communist Party is another useful document. It compiles information from various sources, including Hồ Chí Minh’s reports submitted to the Comintern (the Communist International) and translated into Vietnamese. It includes his report dated February 18, 1930, containing information on Siam and the period when he arrived in Siam for the first time.

Books by foreign scholars have also been very informative and useful. They are, among others: Thailand and the Southeast Asian Networks of the Vietnamese Revolution (1885–1954) by Christopher E. Goscha; Ho Chi Minh: A Life by William J. Duiker; Ho Chi Minh: Du révolutionnaire à l’icône by Pierre Brocheux; Ho Chi Minh notre camarade: Souvenirs de militants Français edited by Léo Figuères; and Ho Chi Minh: The Missing Years by Sophie Quinn-Judge. However, most of these authors, apart from Goscha and Sophie Quinn-Judge, provided little detail about Hồ Chí Minh’s whereabouts and activities in Siam, with whom he resided, and his companions when moving from one place to another place.

Besides documentary research, I had the opportunity to visit the places where Hồ Chí Minh resided or where Vietnamese patriots conducted their activities such as: Ban Nong On (บ้านหนองโอน) in Udon; Ban May (บ้านใหม่) or Ban Na Chok (บ้านนาจอก) in Muang district in Nakhon Phanom (นครพนม); as well as That Phanom (ธาตุพนม) and Tha Uthen (ท่าอุเทน) districts in Nakhon Phanom. I was also able to meet and discuss with some elderly Việt Kiều. Likewise, in Vietnam, I met Sơn Tùng, who had interviewed Đặng Quỳnh Anh, and Trần Đình Lưu, a Việt Kiều Hồi Hương from Nakhon Phanom who had direct contact with the families of the revolutionaries and who had written a book entitled Việt Kiều Lào-Thái với Quê Hương [Lao-Thai overseas Vietnamese and their homeland]. He was also involved in revolutionary activities in the 1970s and 1980s. Back in Thailand, I also met and shared information with the Việt Kiều interested in the subject of Hồ Chí Minh in Siam. These meetings allowed me to crosscheck information. Nonetheless, the number of elderly people I could interview was limited, and the number diminishes with each passing year.4)

This article is an overview of Hồ Chí Minh’s sojourn in Siam. I have tried to compile scattered information from various sources and crosscheck as much as possible. There are, however, limits to the article. For now, I have focused on Hồ Chí Minh’s sojourn in Siam without considering the wider context of his activities in other countries. Secondly, I could not use information in Russian and, more importantly, Chinese, which would have shed more light on Hồ Chí Minh’s activities in Siam. I was also unable to access the Centre des Archives d’Outre-Mer (CAOM) in Aix-en-Provence, France, where valuable material, including that left by French security agents, is stored. Finally, while I have tried to draw upon previous studies on Hồ Chí Minh in Siam as much as possible, there are still a number of works I have yet to explore. It is expected that further research will make this study more complete.

In my paper, I explore the reasons for which Siam served as an anti-colonial base by the Vietnamese. Why was Hồ Chí Minh in Siam? By what means did he arrive in this country and where from? Where did he stay and what were his activities? Who worked with him and what pseudonyms did Hồ Chí Minh use during his mission in Siam?

The Migration of the Vietnamese to Siam

The migration of Vietnamese to Thailand (or Siam before 1939)5) took place over many periods: the Ayutthaya period in the mid-seventeenth century, the early Rattanakosin period during the reigns of King Rama I and II in the late eighteenth–early nineteenth centuries, the reign of King Rama IV in the mid-nineteenth century, the reign of King Rama V from the late nineteenth–early twentieth centuries, and the period during and after World War II.

Migration to Siam was motivated by various factors: religious persecution by the Nguyễn Court, French suppression, as well as hardship and suffering from poverty. During the reign of King Rama III, the Vietnamese were also forcibly moved from Cambodia as prisoners-of-war following the war between Vietnam and Siam on Cambodia in 1833–47. From the late nineteenth to mid-twentieth century, Vietnamese nationalists moved to present-day northeastern Thailand and used it as a base for their resistance to the French in Laos and Vietnam. During the Japanese Occupation at the time of World War II, famine and poverty also forced a number of Vietnamese to leave their country.

During the reign of King Rama I in the early Rattanakosin period, Siam was a refuge for Nguyễn Phúc Ánh or Nguyễn Ánh, a nephew of the last Nguyễn lord who ruled over southern Vietnam during the 1780s (Chao Phraya Thipakornwongse 1983, 29–30). Nguyễn Phúc Ánh or Nguyễn Ánh, later called Gia Long, fled from the Tây Sơn brothers to Siam with 1,000 followers in the 1780s. He was sheltered in Bangkok by King Rama I, who also provided him with troops and arms, enabling him to rebuild part of his forces to fight against the Tây Sơn. In return, he lent his forces to the Siamese army fighting against Burma in Dawei (ทวาย) and the Melayu rebellion in the Gulf of Siam (Thanyathip and Trịnh 2005, 16).

Nguyễn Phúc Ánh and his followers were allowed by Rama I to stay at Ban Ton Samrong (บ้านต้นสำโรง) Tambon Khok Krabuu (ตำบลคอกกระบือ) (Chao Phraya Thipakornwongse 1983, 29). Later they were moved to Samsen (สามเสน) and Bangpho (บางโพ) in Bangkok. Samsen, called Ban Yuan Samsen (บ้านญวนสามเสน), is well known as a Vietnamese village. Another area where a number of the Vietnamese used to live is Bangpho, where Wat Annamnikayaram (วัดอนัมนิกายาราม) is presently located.6) These two places were 3–3.5 km apart and located in Bangkok on the left side of the Chao Phraya river. While in Bangkok, he was sometimes joined by his partisans from Vietnam. He left Siam after spending no less than four years there. He continued to receive help from Rama I who sent him ammunition and ships (ibid., 98–99, 106–108). With the help of the French, the Portuguese, Chinese merchants, and King Rama I, Nguyễn Phúc Ánh defeated the Tây Sơn in present-day southern Vietnam in 1802, unified the country, and proclaimed himself Emperor Gia Long. This is one of the instances when Siam served as a refuge and base of resistance by Vietnamese exiles who had fled the country because of internal politics.

Phan Đình Phùng and Phan Bội Châu were part of the first generation of Vietnamese anti-colonialists from the turn of the twentieth century. They spent time in Siam to canvas support for their anti-colonial movement. Phan Đình Phùng (1847–96) was the leader of the patriotic and anti-colonial Cần Vương movement in the 1880s and 1890s. For him, the Siamese were useful as a supplier of arms (Lê Mạnh Trinh 1961, 9). Since it was also opposed to French expansion from central Vietnam to northeastern Siam, the Siamese army provided arms to Cần Vương in the late 1880s (Goscha 1999, 25). Phan Bội Châu was a patriotic who founded the Đông Du movement in 1905. He admired Japan’s growing military and economic potential and brought some Vietnamese students with him to Japan. But in 1909, they were forced to leave as Japan’s good relationship with the French took precedence over Châu’s call for Asian unity against Western colonization. With the help of a prince and officials from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Siam, Phan Bội Châu, who visited Siam at least three times between 1908 and 1911, was allowed to transfer his students, who had been deported from Japan, to Siam. These students were allowed to reside at and use the land at Ban Tham (บ้านถ้ำ) in Paknampho (ปากน้ำโพ),7) taken care of by Đặng Thúc Hứa. At the same time, Phan Bội Châu also asked the Siamese government to allow him to transfer weapons from Hong Kong to Vietnam by way of Siam (ibid., 31). His request was not granted as the Siamese government feared disrupting the Franco-Siamese relationship.

The loss of territories on the left and right sides of the Mekong river as a result of the French-Siamese treaties signed in 1893 and 1904, coupled with the fact that the Siamese court was forced to renounce its claims on Cambodian territory following the treaties signed in 1907, led to increasing Siamese hostility, distrust and fear vis-à-vis the French. This forged a unity between the Siamese court and the Vietnamese; the Siamese hoped that the Vietnamese anti-colonialists would be a force against French colonization. The Siam authorities resisted pressure from the French authorities to arrest and hand over the Vietnamese to the French, but they were sometimes obliged to take action and close the Vietnamese communities, for example, Ban Tham in 1914 and Ban Dong in 1917, or when the revolutionary bases in Ban Dong were destroyed in 1930.

After the meeting in Hong Kong that saw the Vietnamese communist groups unify to form one party at the end of 1929 and the start of 1930, and after the Xô Việt Nghệ Tĩnh revolts in Vietnam from April 1930 to the summer of 1931, the Siamese authorities, pressurized by the French, became stricter with the Vietnamese than during Hồ Chí Minh’s stay. Some Vietnamese were arrested in Bangkok after Hồ’s voyage to Hong Kong, for example, Võ Tùng and Đặng Thái Thuyến on June 4, 1930 (ibid., 11). Siam served once again as a refuge and as a base for Vietnamese resistance against the French. Đặng Thúc Hứa, one of the Vietnamese exiles who joined Phan Bội Châu in Japan in 1908, was in Siam with the latter in 1909 and later on set up bases in this land.

Siam as a Vietnamese Anti-colonial Base

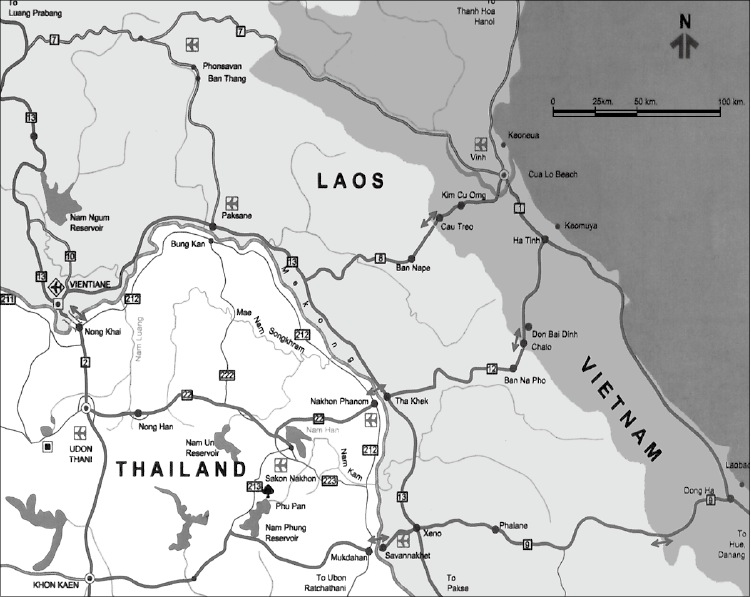

Geographically, Siam was well placed to serve as a base for anti-colonial operations in the west of central Vietnam. Siam can be connected to Vietnam by land and sea routes. Most of the Vietnamese arrived in Siam by land via Laos then crossed the Mekong river to northeastern Siam, present-day Isan (อีสาน). The distance is approximately 310 km from Vinh in Nghệ An province of Vietnam to Nakhon Phanom in northeastern Siam if travelers took the road currently called Road No. 8. But from the Vietnam-Laos border in Hà Tĩnh province to Tha Khek town (เมืองท่าแขก) in Khammuon province (แขวงคำม่วน) by Road No. 12, and then Nakhon Phanom, the distance is only approximately 145 km.

According to Đặng Quỳnh Anh in Con Người và Con Đường8) (Sơn Tùng 1993, 54), she took two months to travel by foot from Kim Liên village, Thanh Chương district in Nghệ An province to Ban Pak Hinboun in Khammuon province of Laos. Ban Pak Hinboun is located 3 km from the Mekong bank and opposite to Tha Uthen district in Nakhon Phanom. However, those in good physical condition may take less than two months. The route passes through jungle full of wild animals and diseases. It was believed that Đặng Quỳnh Anh and most of the Vietnamese leaving from Nghệ An and Hà Tĩnh would have travelled on the Road No. 8, or a part of the road, one that passed through the high mountain range called Trường Sơn, separating Vietnam and Laos. This mountain range and the Động Trìm and Động Trẹo caves were mentioned in her interview in Con Người và Con Đường (ibid., 10). Road No. 12 is another route connecting Hà Tĩnh to Tha Khek and Nakhon Phanom. Central Vietnam, starting from Quảng Trị, is also connected to northeastern Siam by Road No. 9, which was built by the French in the beginning of 1920s.9)

Map 1 Road No.s 8, 9 and 12 Presently Connecting Northeastern Thailand and Vietnam

Source: Former Thai Ambassador to Hanoi, Krit Kraichitti.

The Vietnamese scattered in Siam represented a good source of recruitment for the anti-colonial movement. They had been driven out by poverty and exploitation, and hated the French. This is one of the reasons why Đặng Thúc Hứa focused on setting up bases in Siam.10) Using Siamese territory as an anti-colonial base was safer than using Laos and Vietnam. Although the Siamese government was sometimes under French pressure to stop the Vietnamese activities, Siam was not a French colony or protectorate. Consequently, French intelligence agents could not operate freely in Siam. Moreover, Siam had sympathy for the Vietnamese fighting French colonization as it was also encountering the same thing at that time. Siamese authorities did not pay much attention to what the Vietnamese were doing. In the beginning of the 1910s, a Siamese prince even arranged for Phan Bội Châu and his followers to stay in a village in Ban Tham in Paknampho, Nakhon Sawan (Goscha 1999, 33).11) Paknampho, which is approximately 240 km away from Bangkok, was the first community set up by Đặng Thúc Hứa. It remains a very fertile area even today. Siam served as the liaison point between China, Hong Kong and Vietnam.

Hồ Chí Minh’s Choice of Siam

When the French Communist Party did not step in to help save his country from French colonization, Hồ Chí Minh realized that the Vietnamese should rely on themselves and that he should conduct his mission in Asia, not in Europe or the Soviet Union. He thus left for Guangdong in 1924. However, three years later, Chiang Kai Shek started cracking down on the Chinese communists. This was a severe setback for the Vietnam Revolutionary Youth League (Việt Nam Thanh Niên Cách Mạng Đồng Chí Hội), which had been established in 1925. It became difficult for them to operate and their headquarters had to be moved from Guangdong to Hong Kong (Figuères 1970, 43). Consequently, there was a need to set up a new base. When it became impossible to operate in Guangdong, Hồ Chí Minh or Lý Thụy12) had two choices: remain in China and risk being arrested, or leave for Siam to restore contact with the Vietnamese movement there, as well as to strengthen the movement in Indochina, especially Laos. He decided on Siam.

Hồ Chí Minh was advised by Jacques Doriot, a member of the French Communist Party, to return to Europe before proceeding to Siam. He agreed and proposed to the Comintern (the Communist International) that he should go to Siam where he would be able to work closely with the Overseas Chinese Communists in Bangkok. Moreover, he would be able to mobilize the Vietnamese and strengthen the anti-colonial movement in Siam, especially the training of the young members.

He thus left Guangdong for Hong Kong by train on May 5, 1927 (Duiker 2000, 145), then on to Shanghai and Vladivostok, which was the headquarters for the Soviet revolutionary operation in the Far East. From Vladivostok, he arrived in Moscow in early June 1927 (Brocheux 2003, 74–75; Duiker 2000, 88), where he sent a travel request to the Far Eastern Bureau (Duiker 2000, 88), proposing to go to Siam rather than return to Shanghai, as was suggested by the Comintern agent Grigory Voitinsky. The Comintern wanted Hồ Chí Minh to work in southern China because he had a very good relationship with the Chinese Communist Party.

In November 1927, Hồ Chí Minh received word from the Comintern. Instead of Siam, he was instructed to work with the French Communist Party in Paris. He thus left for Paris, stopping briefly in Berlin in early December 1927 to help a German friend set up a branch of the new Anti-Imperialist League. The French tried to locate him when he arrived in Paris so he left for Brussels to attend a meeting of the executive council of the Anti-Imperialist League, where he met the Indian nationalist Motilal Nehru, the Indonesian nationalist Sukarno, and Song Qingling, Sun Yat Sen’s widow (ibid., 48–49). In mid-December, he returned briefly to France, then left for Berlin by train. He stayed in Berlin for several months.

He realized that although the French Communist Party paid attention to colonial problems, there was no concrete action. After travelling without purpose from country to country and waiting impatiently for approval for his journey to Siam, he wrote to the Far Eastern Bureau again from Berlin in April 1928 (ibid., 149–150). Within the same month, he finally received a reply from Moscow, giving him permission and funds to travel to Indochina, and three months’ rent for a room (ibid., 150). The Comintern’s decision was conveyed by V. P. Kolarov, a Bulgarian economist and communist leader and member of the Comintern presidium until its dissolution in 1943 (Brocheux 2003, 77). The Comintern gave permission to Hồ Chí Minh to set up a revolutionary movement in Siam (Goscha 1999, 76). His mission was to strengthen the revolutionary movement in Indochina against French colonization, using Siam as a base.

By the end of the 1920s, a number of the Vietnamese in Siam were already mobilized and trained, thanks to Đặng Thúc Hứa and his compatriots who had arrived in Siam earlier. Siam had already become an anti-colonial base in the west of Vietnam before Hồ Chí Minh arrived in 1928. After the repression by Chiang Kai Shek in 1927, more Vietnamese moved to Siam from southern China. Furthermore, the Xô Viết Nghệ Tĩnh movement, which faced difficulties in 1930–31, pushed more Vietnamese to northeastern Siam.

Hồ Chí Minh’s Voyage to Siam

In early June 1928, Hồ Chí Minh left Berlin and travelled by train from Switzerland to Italy, passing through Milan and Rome. He arrived in Naples where he embarked on a Japanese ship for Siam at the end of June (Duiker 2000, 150; Brocheux 2003, 77–78; Bảo Tàng Hồ Chí Minh 2011, 112). Goscha mentioned that according to the French Sûreté report written in January 1931, Hồ Chí Minh left Russia before the Comintern Congress of July 1928 and travelled clandestinely to Siam by way of Berlin. The ship passed by the Suez canal, Port Saïd, the Red Sea, Colombo (Sri Lanka), Singapore, and Bangkok (Sukpreeda 2006, 54).

When he arrived in Singapore, he was received by the Nanyang Organization. He had to embark on a smaller ship named Gola to continue his journey to Siam because of the sand bar at the mouth of Chao Praya river (ibid., 54). Sukpreeda mentioned that Hồ Chí Minh disembarked at BI port near Bangkok13) as an overseas Chinese trader under the name “Mr. Lai” (ibid., 54–55) or Nguyễn Lai (Trần Dương 2009, 42; Bảo Tàng Hồ Chí Minh 2011, 39). He spoke fluent Cantonese.

Hồ Chí Minh’s Activities in Siam

Hồ Chí Minh went twice to Siam: first in mid-1928 and subsequently at the beginning of 1930. Different documents and books give different dates for his first arrival in Siam, with many Western works following Hoàng Văn Hoan’s (1988) and Lê Mạnh Trinh’s (1975) memoirs.

Lê Mạnh Trinh did not specify when Hồ Chí Minh arrived in Siam but mentioned that he arrived in Ban Dong, Phichit in the autumn of 1928 (Lê Mạnh Trinh 1975, 31). Hoàng Văn Hoan,14) in his memoir entitled A Drop in the Ocean: Hoang Van Hoan’s Revolutionary Reminiscences, stated that Hồ Chí Minh first arrived in Siam in August 1928 and stayed between August 1928 and September 1929, then left for Hong Kong (Hoàng Văn Hoan 1988, 47, 51–52). He came back again and stayed briefly from March–April 1930.

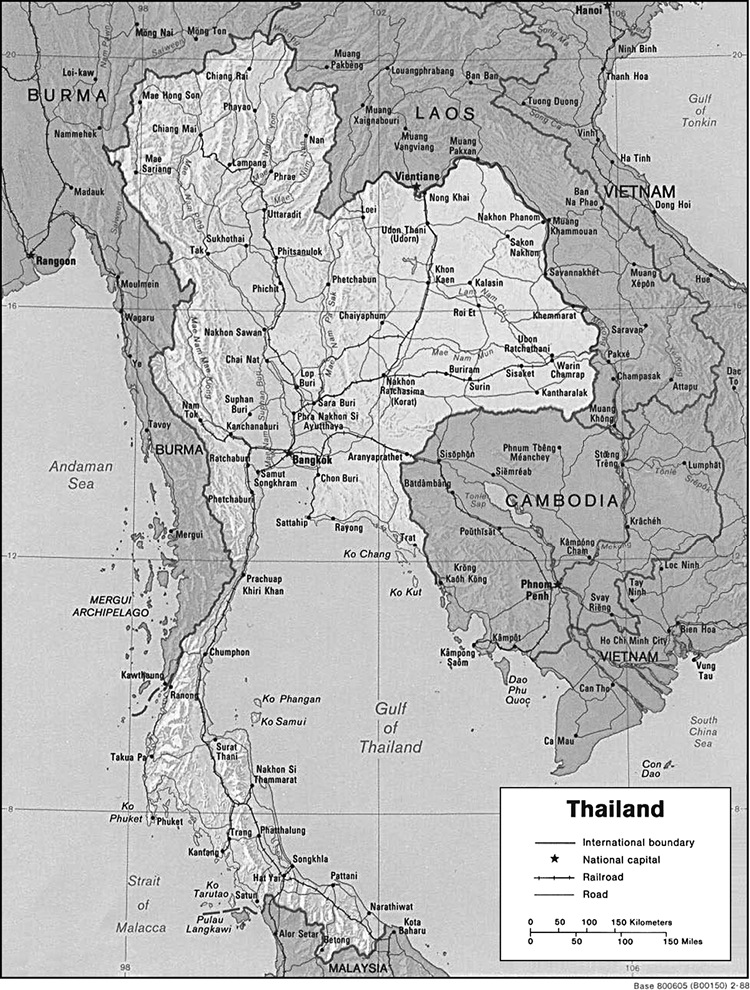

Map 2 Map Showing the Locations of Districts and Provinces

Source: http://www.google.com, accessed on December 5, 2012.

Note: Boundary representation is not necessarily authoritative. Names in Vietnam are shown without diacritical marks.

Goscha (1999, 75–76, 102, footnote 68), however, asserts that Hồ Chí Minh arrived in Siam sometime in mid-1928, left Siam at the end of 1929,15) and returned to Siam again in March 1930. According to William Duiker (2000, 150), he arrived in Siam in July 1928, left at the end of 1929, and came back in April 1930. He stayed briefly in Bangkok and Udon Thani, before leaving the country. Sophie Quinn-Judge (2002, 126) claims that Hồ Chí Minh spent time in Siam from July 1928–November 1929.

According to Hồ Chí Minh Toàn Tập (2000, Vol. 3, 13) and Trần Dương, Hồ Chí Minh arrived in Siam in July 1928 and stayed until November 1929, before leaving for China. This information is based on his report to the Comintern written on February 18, 1930. According to Trần Dương (2009, 29), he came back to Siam in March 1930 and left Siam at the end of March or the beginning of April 1930.

In Siam, after disembarking at a port near Bangkok and staying there briefly, he went to Ban Dong in the district of Phichit and then to Udon Thani. From Udon Thani, he continued to Sakon Nakhon (สกลนคร), Nakhon Phanom, as well as Nong Khai (หนองคาย). He left Siam for China and stayed in Hong Kong and Shanghai during the winter of 1929–30 (Figuères 1970, 43). He then returned to Siam in March and April 1930, staying briefly in Bangkok and Udon Thani, before leaving Siam for good.

According to Sukpreeda, during his first trip to Siam, Hồ Chí Minh visited an Annamese temple called Wat Lokanukhlor (วัดโลกานุเคราะห์) in Thai, or Chùa Từ Tế in Vietnamese. This temple is located within the Chinese community on Rajawong Road (ราชวงศ์) in Bangkok (Sukpreeda 2006, 55). Sukpreeda notes that there were many overseas Chinese residents as well as Nanyang Chinese in this area. Less than 100 m from the temple was a crossroad where Sun Yat Sen had given a speech to the overseas Chinese two or three years before October 1911 (ibid.). Wat Lokanukhlor or Chùa Từ Tế was a meeting-point for the Vietnamese cadres at that time. Hồ Chí Minh went to this temple to see the abbot Sư Cụ Ba or Bình Luơng Ba, who was a Vietnamese patriot with links to the Vietnamese in Siam. He was part of the Mouvement des Lettres patriotes that had sought refuge in Siam and he had also founded the temple. Later when he was seriously sick in 1964, Ho Chi Minh sent a plane to repatriate him to Hanoi to be hospitalized in Bệnh viện Hữu Nghị Việt-Xô (Việt-Xô Friendship Hospital) (Trần Dương 2009, 115). Hồ Chí Minh also visited him at the hospital. He stayed briefly in the temple before leaving for Ban Dong in Phichit.

From Bangkok to Ban Dong

According to Duiker (2000, 151), Hồ Chí Minh arrived in Ban Dong in August 1928; Lê Mạnh Trinh in Cuộc Vận Động Cứu Quốc Của Việt kiều ở Thái Lan (1961, 116) dates his arrival to the autumn of 1928.16)

Ban Dong is located near Nan river (แม่น้ำน่าน), which is a tributary of Chao Phraya river (แม่น้ำเจ้าพระยา). Ban Dong was part of Phichit district in Nakhon Sawan province, but today Phichit district has become a province on its own and Ban Dong is now called Ban Noeun Sa Mo (บ้านเนินสมอ), under Pa Ma Khab (ป่ามะคาบ) district in Phichit province.17) Phichit is approximately 340 km from Bangkok and is accessible by train and boat.

After Ban Tham in Paknampho, site of the first Vietnamese community and center of the movement set up by Đặng Thúc Hứa, was closed in 1914 by local authorities under French pressure, the Vietnamese moved to Ban Dong, 100 km away. The Vietnamese had been allowed by a Siamese prince, who sympathized with the Vietnamese resistance against the French, to settle down and start plantations in Ban Tham in 1910, when Phan Bội Châu was in Bangkok (Goscha 1999, 33).

According to Ngô Vĩnh Bao in Cuộc Hành Trình Của Bác Hồ Trên Đất Thái Lan, Hồ Chí Minh went to Phichit by train and stayed in a hotel (Trần Dương 2009, 42). The next day he went to a shop named Quyên Truyền Thịnh, owned by an overseas Chinese sympathetic to the Việt Kiều’s cause. This shop was in fact a clandestine contact point between Ban Dong, Guangzhou, and Hong Kong, ideal to hide from the eyes of the Siamese authorities and French spies. At the shop, Hồ Chí Minh gave a sheet of paper to the shop’s owner containing a message for Võ Tùng (Lữ Thế Hành or Lưu Khải Hồng) (ibid.).18) According to Trần Dương, the message was received by Võ Tùng’s compatriot named Hy. As Võ Tùng was busy in the rice field, Hy came to pick Hồ Chí Minh by boat, but he refused to go with him. He wanted to see Võ Tùng in person. Hy had to return and Võ Tùng came personally to receive Hồ Chí Minh (ibid., 43). This shows that Hồ Chí Minh was very cautious. In Con Người và Con Đường, Đặng Quỳnh Anh mentioned that one night Võ Tùng returned home with a man, later identified as Nguyễn Ái Quốc or Hồ Chí Minh (Sơn Tùng 1993, 158). This confirms that Hồ Chí Minh arrived in Ban Dong with Võ Tùng. According to Trần Đình Lưu (2004, 60–61), Võ Tùng introduced his guest as a close friend from Guangzhou and a medicine trader named Thầu Chín19) (ibid., 61) and that he was here to stay for a while. In Ban Dong, Hồ Chí Minh stayed in Võ Tùng and Đặng Quỳnh Anh’s house.

According to Lê Mạnh Trinh (1961, 32) and Trần Đình Lưu (2004, 61–62), Hồ Chí Minh stayed in Phichit for around 10 days; according to Duiker (2000, 151), he stayed for two weeks before leaving for Udon Thani in northeastern Siam. Đặng Quỳnh Anh in her interview by Sơn Tùng in Con Người và Con Đường states that during his stay in Ban Dong, he also made trips to nearby areas with his compatriots such as Đặng Thúc Hứa, Võ Tùng, Đặng Thái Thuyến, and Ngọc Ân (Trần Đình Lưu 2004, 64). All of them arrived in Ban Dong in the 1910s, that is, before Hồ Chí Minh.

Hồ Chí Minh used his time in Ban Dong to educate the Việt Kiều. He informed them about the political situation in Vietnam and around the world, and taught them how to hold discussions, elevating the political level and revolutionary understanding of the Vietnamese people in Ban Dong. He usually exchanged views with Đặng Thúc Hứa, Võ Tùng, Đặng Thái Thuyến, and other colleagues. In the daytime he engaged in physical work in the fields with his compatriots and cleaned the house; at night he gathered the people to instruct them about politics. His lectures were simple and brief but meaningful and persuasive. They usually consisted of three parts. The first part was about the situation in Vietnam and in the world, as well as the cooperation of Vietnamese in other places. The second part concerned revolutionary theory and the last part was dedicated to answering questions or explaining unclear points. His teaching on politics always combined Marxist-Leninist theory with the main strategies of the Vietnamese revolution, explaining the way to gain independence and freedom.

Words such as “comrade,” “imperialism,” “socialism,” “Marxism,” “Lenin,” and “Stalin” were heard for the first time among the Vietnamese in Siam during the meeting in Ban Dong (ibid., 63). He explained that “comrades” or “đồng chí” in Vietnamese meant people sharing the same will and fighting for the same purpose (ibid., 62). While in Ban Dong, he moved from one community to another and spent time meeting with the Vietnamese and teaching them to behave well, to follow Thai law, to preserve Vietnamese culture, to help each other, to be honest, and to take good care of their children.

Vietnamese Revolutionary Organizations in Siam in the Mid-1920s

Even prior to Hồ Chí Minh’s arrival in Siam, Vietnamese revolutionary organizations had already been established in the country, starting with Ban Dong (Phichit).

As mentioned earlier, when Phan Bội Châu arrived in Siam for the third time in 1910, the Siamese government made arrangements for him and his student to reside in Ban Tham, Paknampho and use the land for plantations. Đặng Thúc Hứa was in charge of this place. Later, Đặng Quỳnh Anh was sent to Ban Tham to take responsibility of this Ban and the Vietnamese children. In 1914, Ban Tham was closed due to the pressure the French exerted on the Siamese government. Consequently, Đặng Thúc Hứa and Đặng Quỳnh Anh had to move to Ban Dong, Phichit, which was also closed in 1917. Đặng Thúc Hứa had to sell the farm and he left for southern China with his student (Goscha 1999, 64), while Đặng Quỳnh Anh left for Lampang (ลำปาง) (Sơn Tùng 1993, 79).

Đặng Thúc Hứa returned to Ban Dong in 1919 and rebuilt it with the help of Đặng Quỳnh Anh. We can see that the setting up of communities turned bases during the 1910s was not very stable. In the beginning of the 1920s, Đặng Thúc Hứa had increasingly gathered the Vietnamese, particularly those along the Mekong river, which was used as a contact point for the Vietnamese base in central Vietnam and to receive the Vietnamese coming from Nghệ Tĩnh. Ban Dong became the center of the Vietnamese resistance in Siam and the main political training center for the revolutionary youth (ibid., 81, 89–91; Goscha 1999, 45–46).

In 1926 a branch of the Vietnamese Revolutionary Youth League (Việt Nam Thanh Niên Cách Mạng Đồng Chí Hội) was established (Lê Mạnh Trinh 1961, 3, 33) by Hồ Tùng Mậu who arrived in Siam in 1925.20) It came under the direction of the Vietnamese Revolutionary Youth League in Guangzhou (later moved to Hong Kong) that was set up in 1925. Võ Tùng was nominated Secretary (Trần Đình Lưu 2004, 49–50). In 1927, the second branch of the Vietnamese Revolutionary Youth League (the Youth League) was established in Udon Thani (Lê Mạnh Trinh 1961, 33).

The main task of the Youth League was to teach the Việt Kiều and awaken their consciousness of nationalism; establish communications between Vietnam and the Youth League in Guangzhou; and receive and train patriots from Vietnam. Two organizations were set up in 1926: Cooperatives (Hội Hợp Tác) and the Việt Kiều Friendship Organization (Hội Việt Kiều Thân Ái) (Hoàng Văn Hoan 1988, 36; Lê Mạnh Trinh 1961, 24–26). The first Cooperatives and the Việt Kiều Friendship Organization appeared in Ban Dong in 1926, followed by Udon, Sakon Nakhon, and Nakhon Phanom in 1927 and 1928.

The Cooperatives was an organization of patriotic youth who were involved in the revolutionary movement. This included both Việt Kiều in Siam and Vietnamese from Vietnam (Trần Đình Lưu 2004, 49; Duiker 2000, 151). The youth from Vietnam were mostly intellectuals from the lower middle class or students. The Cooperatives trained reserve forces for the Youth League and gave them an understanding of politics and patriotism. It selected the best members to the Youth League and sent them to Guangzhou or back to Vietnam to work clandestinely.

The youth lived in collectives. Some worked on the farm in groups of five or six, while other specialized in sawing, bricklaying, carpentry, and trade. They made their own work plan and shared the tasks. They put aside part of the harvest for the community’s consumption and sold the rest of it. The income was spent on living expenses for each group and the rest went into common funds for the Cooperatives, which would be used for sending people to Vietnam or China, building schools, subsidizing student expenses, and paying the printing costs of propaganda and publication. The Cooperatives also recruited Việt Kiều who resided permanently in Siam. These Việt Kiều were independently engaged in small businesses and were in a good financial situation, so they could contribute funds in accordance to their ability. They also helped exiled patriots or orphans, and leveraged their status to deal with the local authorities. The Cooperatives from the early 1920s were well organized and well managed, especially in terms of their budget. This gave the Vietnamese confidence in their cause. With the hard work of members, after five or six years, the Cooperatives had gathered enough funds to carry out revolutionary missions.

The Việt Kiều Friendship Organization was a broad organization that could be found almost everywhere the Việt Kiều resided, particularly in the northeastern provinces of Siam. There were two kinds of members: full members and associate members. Full members registered with the organization, paid fees, and attended meetings regularly. Associate members were scattered in various remote areas and could not meet regularly. They provided moral support and material assistance to the organization to the best of their abilities. Though some of the Việt Kiều had lived in Siam for a long time and had obtained Thai nationality, they were still attached to Vietnam. Organizations affiliated with the Việt Kiều Friendship Organization were the Women’s Group and the Youth and Children Group (Lê Mạnh Trinh 1961, 26).

From Ban Dong (Phichit) to Udon Thani

According to Duiker (2000, 151), Hồ Chí Minh left Ban Dong for Udon Thani in September 1928. Hoàng Văn Hoan21) stated that Hồ Chí Minh took 15 days to travel by foot from Ban Dong to Udon, arriving in August 1928 (Goscha 1999, 47). According to Lê Mạnh Trinh, his trip took 40 days, but for Đặng Quỳnh Anh, it was only slightly more than 10 days (Sơn Tùng 1993, 153). He was accompanied by Đặng Thái Thuyến, Võ Tùng, Ngọc Ân, and probably also Đặng Thúc Hứa. The distance between Ban Dong and Udon is approximately 500 km. Forty days seems too long; if the trip really took so long, Hồ Chí Minh and his colleagues might have stopped in a few places along the way to observe the condition of the Vietnamese and the topography along the route.

Udon Thani is a big town and the center of northeastern Siam. It is easily accessible from Khon Kaen (ขอนแก่น), Nong Khai, Sakon Nakhon, Nakhon Phanom, and Mukdahan (มุกดาหาร). Udon Thani was packed with Việt Kiều. The number of Việt Kiều there was bigger than in Phichit because Udon was located not far from the Mekong and was one of the receiving points of the Vietnamese from central Vietnam. As such, Hồ Chí Minh stayed for quite a while in order to meet, educate, and encourage the Việt Kiều to participate in anti-colonial and revolutionary activities.

Even before Hồ Chí Minh’s arrival in Udon, Đặng Thúc Hứa, Võ Tùng, and other cadres had already started in 1924 to establish a new base in Ban Nong Bua (บ้านหนองบัว), 3 km from the center of Udon. This base served as a connecting point between Phichit and Nakhon Phanom because the base in Phichit was too far from the base in Nakhon Phanom, which served as the reception base of the Vietnamese from central Vietnam.

A branch of the Youth League in Udon was set up in 1927, as well as the Cooperatives and the Việt Kiều Friendship Organization. At the first meeting of the Youth League in Udon, Hồ Chí Minh gave a report of the global situation and the struggle of the socialist revolution in general and in Vietnam in particular. He suggested an expansion of the organization, a reorganization of the bases, and the building of a close and harmonious relationship with the Thai people, giving due respect to Thai customs, traditions, and laws (Lê Mạnh Trinh 1961, 34). As for the Cooperatives, initially only the Vietnamese who had come to Siam from Vietnam were accepted as members, but Hồ Chí Minh suggested opening it up to any Việt Kiều who volunteered (ibid.).

While in Ban Nong Bua, Hồ Chí Minh spent much time translating books, for example, Historical Materialism (translated to History of Human Evolution) and ABC of Communism by Bhukarin and Preobrazhensky, to be used for the mobilization and training of young cadres of the League (Brocheux 2003, 80; 2007, 46). He worked with Hoàng Văn Hoan on the translations, with him reading, particularly the texts in Chinese, and translating, and Hoàng Văn Hoan transcribing. Hồ Chí Minh also conducted political classes for the cadres of the Youth League, reorganized the activities and lifestyles of members, raised their consciousness of patriotism, and encouraged them to work in the farms with the Việt Kiều. He encouraged the Việt Kiều to learn Thai and to send their children to schools to learn Thai and Vietnamese, urging them to ask permission from the local authorities to open schools for children. When permission had been granted, he also took part in the building of the school.

Initially, most of the Việt Kiều considered Thailand as a temporary homeland. They were eager to return to Vietnam to join the resistance movement and waited for the declaration of independence to return. As such, they did not focus on life in Siam. They did not learn Thai and did not allow their children to do so either (Trần Đình Lưu 2004, 86). But Hồ Chí Minh realized that the colonial resistance in Siam would be a long-running matter and that it was necessary for the Việt Kiều to learn the Siamese language and familiarize themselves with the people, culture, and authorities. In this way, the Việt Kiều would gain the friendship and sympathy of the Siamese people, and local authorities would not object toViệt Kiều activities and movements.

After Đặng Thúc Hứa received permission from the Siamese local authorities to use land to build a farm and plant rice in Ban Nong Bua, the Vietnamese moved in rapidly. The number of Vietnamese families in the Ban Nong Bua community increased from 40 in 1925 to 100 in 1929, and continued to grow (Goscha 1999, 48). After Ban Nong Bua, Đặng Thúc Hứa and his colleagues expanded their activities by setting up another community and base at Ban Nong On (บ้านหนองโอน), 13 km from the center of Udon where currently stands Hồ Chí Minh’s house.

Beside these bases, Đặng Thúc Hứa, Võ Tùng, and their comrades also went to other provinces to reach out to more Việt Kiều, such as Sakon Nakhon, Nong Khai, Nakhon Phanom (in Tha Uthen and That Phanom districts), and Ubon Rachathani (Trần Đình Lưu 2004, 46). At Ban Nong Bua and Ban Nong On in Udon, Hồ Chí Minh drew up a clear plan of activities for the community, such as farming in the day and attending political classes and listening to the news at night. These two villages became populous and strong revolutionary bases receiving young people from Vietnam who were first received in Ban May in Nakhon Phanom. After a short stay in Ban May, if they proved to be reliable patriots, they would be sent for preliminary instruction and language training in Ban Nong Bua and Ban Nong On. If they then showed promise, they would be transferred from Udon to Ban Dong for advanced studies on politics. From there some of them would be sent to China on missions (Goscha 1999, 48). The bases in Udon thus became an important midpoint base connecting Ban Dong in Phichit and Nakhon Phanom.

From Udon, Hồ Chí Minh also made some visits to Nong Khai.22) He stayed near a temple called Wat Srichomcheun (วัดศรีชมชื่น). According to Nguyễn Tài, he accompanied Hồ Chí Minh to Nong Khai in November 1928 in order to meet with Mau and Chu coming from Vientiane, who came to report to Hồ Chí Minh about the situation in Laos and the activities of the Vietnamese there. According to Nguyễn Tài, the contact point in Nong Khai was a tailor’s shop owned by Lục (Trần Dương 2009, 106). Hồ Chí Minh stayed in Nong Khai for six days in November 1928 (ibid.). From Udon, Hồ Chí Minh continued on his journey to Sakon Nakhon and Nakhon Phanom.

From Udon Thani to Sakon Nakhon and Nakhon Phanom

Sakon Nakhon and Nakhon Phanom, in particular, are two other provinces with a large number of Việt Kiều. To reach Nakhon Phanom from Udon, it was necessary to pass by the Sawang Daendin (สว่างแดนดิน) and Muong districts of Sakon Nakhon. Nakhon Phanom and central Vietnam are connected to Laos, which is why Nakhon Phanom was strategically well placed as the receiving point of patriots and revolutionaries from Vietnam. Nakhon Phanom served as the main liaison point between the cadres in Vietnam and the Vietnamese Revolution Youth League in Ban Dong, who were in contact with the Vietnamese Revolution Youth League in Guangzhou via Bangkok.

From Udon, Hồ Chí Minh, accompanied by Nguyễn Tài, went to Sawang Daendin district and then to Muang district of Sakon Nakhon where he stayed in Đặng Văn Cáp’s traditional medicine shop. In Sakon Nakhon, the Việt Kiều Friendship Organization, the Cooperatives, and classes for Việt Kiều children were already in place (Trần Đình Lưu 2004, 69). As in Udon, he organized political classes, updated the teaching of theories of Marxist-Leninist theory and nationalism, and taught new patriotic poems and songs. From Sakon Nakhon, he proceeded to Nakhon Phanom with its three strong revolutionary bases: Ban May (บ้านใหม่), presently called Ban Na Chok; Ban Ton Phung (บ้านต้นผึ้ง); and Ban Wat Pa (บ้านวัดป่า). It was in Ban May that he stayed the longest.

In Ban May, 5 km from the Mekong, hundreds of cadres had already been trained (ibid., 70). Hồ Chí Minh’s purpose in going to Nakhon Phanom was not only to instruct the movement or organize political classes for the cadres; he also wanted to establish a liaison point between central Vietnam and Laos so as to investigate revolutionary potential in Laos and set up a branch of the Vietnamese Youth League in Laos, to make the transition to communism (Goscha 1999, 79). For this purpose, according to Hoàng Văn Hoan (1988, 51), Hồ Chí Minh took a boat from Nakhon Phanom with Nguyễn Tài, crossing the Mekong to inspect the Youth League’s activities among the Việt Kiều in Laos.

I had the opportunity to cross the Mekong from Nakhon Phanom to Ban Xieng Vang (บ้านเซียงวาง or บ้านเซียงหวาง) in Khammuon province in Laos,23) to meet an old revolutionary Việt Kiều whose family lived there when Hồ Chí Minh was in the village. I was aware that Hồ Chí Minh had met up with some Vietnamese to discuss their revolutionary activities there. It is believed that he did not stay there for long because there was a high risk of being followed and arrested by the French who were everywhere in Laos. His visit, though short, deserves more attention.

Ban Xieng Vang is now located in Nong Bok district (บ้านหนองบก), 27 km from Tha Khek town in Khammuon province in Laos and across from Nakhon Phanom province. At present, it takes 30–40 minutes to drive from Tha Khek town to Ban Xieng Vang. During the anti-French and anti-American periods, Vietnamese revolutionaries from Vietnam would pass through Ban Xieng Vang before crossing the Mekong to Nakhon Phanom. A number of Việt Kiều fleeing from the French in Vietnam, from Nghệ Tĩnh in particular, resided there. According to Đặng Văn Hồng,24) there were 5,000 Vietnamese in Ban Xieng Vang in the anti-French period. In 1946, the French learned that Ban Xieng Vang was a strategic point for the Vietnamese resistance operation.

Đặng Văn Hồng was informed by Ông Khu, a Vietnamese in Ban Xieng Vang, that Hồ Chí Minh was accompanied by two persons to Ban Xieng Vang in 1928, but returned to Siam with only one person, probably Nguyễn Tài. I believe that it was Ông Khu who remained in Ban Xieng Vang. Đặng Văn Hồng did not have any idea how many days Hồ Chí Minh stayed in Ban Xieng Vang but was told that Hồ Chí Minh stayed at the residence of Đặng Văn Yến, who had relatives in Ban Na Chok. Some Việt Kiều in Nakhon Phanom speculated that Hồ Chí Minh might have crossed the Mekong from Ban Nard (บ้านหนาด) in Nakhon Phanom, where a number of Vietnamese resided, to Ban Tha (บ้านท่า) in Laos, and continued approximately 2 km to Ban Xieng Vang.

I did not find any memoirs mentioning Hồ Chí Minh’s stay in Ban Xieng Vang. At present, it is recognized by the Vietnamese Museum of Hồ Chí Minh in Hanoi as a place visited by Hồ Chí Minh. Vietnam and Laos have jointly built Hồ Chí Minh’s memorial site consisting of the museum and his altar, built on land donated by the Việt Kiều in Laos and Thailand. This memorial site has been officially inaugurated in December 2012. I had opportunity to visit the site for the second time on September 11, 2013.

During the journey from Udon to Nakhon Phanom and during his stay in Ban May, Hồ Chí Minh was believed to have been accompanied by Hoàng Văn Hoan and sometimes by Nguyễn Tài (Hoàng Văn Hoan 1988, 59; Goscha 1999, 79). It is believed that no-one in Ban May knew his identity, apart from Ngoéc Đại25) (Trần Đình Lưu 2004, 76). He was known instead as Thầu Chín, a member of the Youth League. When he arrived in Ban May, the Cooperatives house was being built. He worked with the Vietnamese and stayed in the house for a time. As he did in Udon and elsewhere, during the day he joined the Cooperatives’ activities in farming, gardening, and fishing (ibid., 75), and organized political classes for cadres at night. He also taught the cadres about underground work and the tricks of French detectives in Indochina, and worked for the education of children and the mobilization of women.

While he was in Nakhon Phanom, other than in Ban May, Hồ Chí Minh stayed with the family of Nguyễn Bằng Cát or Hoe Lợi, an active member of the Youth League in Nakhon Phanom. The family did not know his true identity; they only knew that he was an active member of the League. In order not to be detected by authorities during his stay, he arranged to work in Nguyễn Bằng Cát’s traditional medicine shop as an apprentice with the name Tín or Chú lang Tín (ibid.).

According to Ngô Vĩnh Bao in Cuộc Hành Trình Của Bác Hồ Trên Đất Thái Lan, apart from Muang district of Nakhon Phanom, Hồ Chí Minh also visited Tha Uthen and That Phanom districts, and stayed with six or seven Việt Kiều families in Na-ke (นาแก) district, 27 km from Muang (Trần Dương 2009, 91). He was accompanied by Nguyễn Tài (ibid., 94).

He operated in Siam until November 1929 according to Hồ Chí Minh Toàn Tập (2000, Vol. 3, 11). Goscha (1999, 77) mentioned that he left Siam for Hong Kong in late November or early December 1929. In Ho Chi Minh: Du révolutionnaire à l’icône (2003, 81), Brocheux states that Hồ Chí Minh arrived in Hong Kong on December 23, 1929 under the name of Song Man Cho to lay the foundation of a communist party. Whether it was in November or December, we know that he arrived at the end of 1929. At the same time, there was political chaos in Vietnam and conflicts broke out among Vietnamese communist organizations. He thus had to leave Siam for Hong Kong and Shanghai to resolve problems. It was impossible, however, to pass through the Vietnam-Laos border as it was under tight French control, so he went to Bangkok and took a boat to China. Assigned by the Far East Bureau of the Comintern, he convened a meeting of representatives in Hong Kong and succeeded in merging various organizations into the Communist Party of Vietnam, which was founded on February 3, 1930 (Hoàng Văn Hoan 1988, 51–52).

He came back to Bangkok by boat for the second time in March 1930 (Goscha 1999, 78).26) He met with Chinese communists in Bangkok before moving to Udon Thani to inform the members of the Udon Provincial Committee of the Youth League regarding the merger of the various Vietnamese communist groups, and to transmit the views of the Communist International regarding the foundation of the Siamese Communist Party (Hoàng Văn Hoan 1988, 52). He told them that according to the guidelines of the resolution adopted by the Comintern, communists should participate in the proletarian revolutionary activities of the country in which they reside. Therefore, Vietnamese communists living in Siam had the duty of assisting the oppressed and exploited people in Siam to engage in revolutionary activities (ibid., 53).

On April 20, 1930, Hồ Chí Minh, in his capacity as representative of the Comintern, convened a meeting at Tun Ky Hotel in front of the Hua Lamphong (หัวลำโพง) central railway station in Bangkok27) where he announced the founding of the Siamese Communist Party (ibid., 55). After that, he went to Malaya to help his comrades establish the Malayan Communist Party. According to Hoàng Văn Hoan, Hồ Chí Minh never returned to Siam again (ibid.). During his two visits in Siam, he had trained revolutionary cadres, fostered proletarian internationalism among the Vietnamese revolutionaries residing in Siam, and formed the Siamese Communist Party. The party was formed mainly by the Chinese and Vietnamese in Siam, with the help of the Comintern (ibid., 55–57, 76, 78). A number of members of the Youth League in Siam also joined under Hồ Chí Minh’s persuasion.

Ngô Chính Quốc or Lý, a Vietnamese born in Siam, and Trần Văn Chân or Tăng, were elected to the central executive committee of the party, later called Siam Committee (ibid., 55). Ngô Chính Quốc was also elected the first secretary-general of the party.28) In 1930, Hoàng Văn Hoan became a member of the Siam Committee (ibid., 63), and in 1933 he was in charge of propaganda (ibid., 76) after Ngô Chính Quốc was arrested in Bangkok and handed over by the Siamese authorities to the French (ibid., 63).

Hồ Chí Minh’s Strategies in Siam

We can see that Hồ Chí Minh used various strategies during his mission in Siam in order to minimize the risk of being arrested by Siam authorities and to hide from the French intelligence agents.29) He used pseudonyms and was always escorted by his compatriots wherever he went. He led a simple life and disguised himself, for example, as a traditional medicine apprentice. He also used liaison persons to contact Siamese local authorities and set liaison points—a small shop in Ban Dong, traditional medicine halls in Udon, Sakon Nakhon, and Nakhon Phanom, temples including Wat Lokanukhlor in Bangkok or in the vicinity of temples such as Wat Sichomchuen (วัดศรีชมชื่น) in Thabo (ท่าบ่อ), Nong Khai.

In general, the Siamese authorities did not pay much attention to the activities of the Vietnamese in Siam, but when events in Vietnam provoked the fleeing of Vietnamese to Siam, the French would ask the Siamese authorities to watch the Vietnamese communities and their activities. Hồ Chí Minh’s mission in Siam was confidential and required secrecy. Disclosure of his identity could lead to his arrest and the destruction of the network. It is interesting to see how Hồ Chí Minh hid his identity, with whom he travelled in Siam, and how he escaped detection by local authorities in Siam.

Firstly he used pseudonyms when abroad. One of the pseudonyms he used in China was Lý Thụy. In Siam, he used the names Nguyễn Lai, Thầu Chín, Thọ, Tín or Chú lang Tín, and Nam Sơn as his pen name. He even changed names when moving from one place to another. When he arrived in Bangkok for the first time, his passport carried the name Lai or Nguyễn Lai. When he was in Ban Dong, he was known as Thầu Chín. When he was at Nguyên Bằng Cát’s traditional medicine shop in Nakhon Phanom, his name was Tín or Chú lang Tín. Only a select few knew his true identity—those he had met before or had been his students in Guangdong. Among them were Đặng Thúc Hứa, Võ Tùng, Hoàng Văn Hoan, Lê Mạnh Trinh, Đặng Thái Thuyến, Nguyễn Tài, and Đặng Quỳnh Anh, who was Võ Tùng’s wife and Nguyễn Thị Thanh’s friend.30) All these people kept Hồ Chí Minh’s identity a secret.

Other revolutionary leaders also used pseudonyms when they were in Siam. Võ Tùng used Sáu or Sáu Tùng, and in China, Lữ Thế Hanh or Lưu Khải Hồng. Hoàng Văn Hoan used Nghĩa and Dương. Lê Mạnh Trinh used Tiến, Nhuận, and Tú Trinh. Hồ Tùng Mậu used Ích. Nguyễn Tài used Lê Ngôn, also Tài Ngôn. Đặng Thái Thuyến used Đặng Canh Tân, while Ngọc Ân used Nghĩa. Đặng Thúc Hứa or Cụ Ngọ Sinh was called Cố Đi or Tú Đi. “Cố” means senior person and “Đi” means walking, so Cố Đi means a senior person who has travelled much by foot.

Hồ Chí Minh blended in by leading a simple life. He also participated in physical work such working on farms, gardening, and laying bricks for the school building in Ban Nong Bua. During his voyage from province to province, he also carried belongings like his companions. In this way, he was not perceived differently from others. He also learned some Siamese words every day.

Another strategy he adopted was to always be on the move. His longest stay was in Nakhon Phanom and Udon. In Nakhon Phanom, he stayed in Ban May and a traditional medicine shop owned by Nguyễn Bằng Cát or Hoe Lợi, under the name of Chú lang Tín. In Udon, he stayed in Ban Nong Bua and Ban Nong On, and in another traditional medicine shop owned by Đặng Văn Cáp,31) taking on the identity of an apprentice. In Sakon Nakhon, he stayed at yet another medicine shop owned by Đặng Văn Cáp. I believe that Hồ Chí Minh chose to stay in these traditional medicine shops for two reasons: he wanted to use these shops as liaison points for the Vietnamese revolutionaries and he wanted to learn about traditional medicine (Trần Dương 2009, 72). Sophie Quinn-Judge (2002, 129) mentioned that according to Đặng Văn Cáp’s memoirs, Hồ Chí Minh wished to learn how to use traditional medicine to treat sick villagers and possibly to cure his own tuberculosis. Hồ Chí Minh had revealed to his Vietnamese colleague in Hong Kong that he had been sick for more than a year in Siam.

During his stay in Siam, it did not seem that Hồ Chí Minh had direct contact with local authorities. This was to avoid being suspected or followed by Thai police and the French intelligence agents. Consequently, in order to get permission from local authorities to build a school in Ban Nong Bua, he suggested that his compatriots, the Việt Kiều Cũ or Việt Cũ, the Việt Kiều of the older generation who had lived in Siam for a long time and were familiar with the Siamese local authorities, do so. Hoàng Sâm, pseudonym Kỳ (Hoàng Văn Hoan 1988, 75), was one of Hồ Chí Minh’s intermediaries for two years.32) He had studied and resided for a long time in Udon Thani so he was on good terms with local authorities. He later became a Vietnamese general in the army of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (Trần Đình Lưu 2004, 86–87), or colonel according to Goscha (1999, 102, footnote 66).

There were occasions, however, where Hồ Chí Minh came under suspicion and was followed by local authorities who were under French pressure. Once in Udon Thani, he was followed by the police and took refuge in a Buddhist temple named Phothi Somporn or Wat Phothi Somporn (วัดโพธิสมภรณ์), whose construction he had taken part in as a bricklayer. He was protected by the abbot Phra Kru Thammajedi (พระครูธรรมะเจดีย์), who forbade the police from entering the temple, assuring them that there were no “bad people” in the temple. It was believed that the abbot did not know Hồ Chí Minh’s true identity at that time. This story was later told by the abbot himself to Phan Văn Tượng, a Việt Kiều representative in Udon.33) On another occasion, Hồ Chí Minh found himself tailed while in Thabo, Nong Khai. He was saved by a seven-year-old girl who saw him trying to dodge the police. She put a rope tethered to her buffalo in Hồ Chí Minh’s hand and handed him a hat, allowing him to pass off as a farmer bringing his buffalo to the rice field. It appears that the French intelligent agents had learned of his presence in Siam at that time. This could have been due to the changing of the name of a newspaper Đồng Thanh to Thân Ái, and by the articles he wrote in it. The Việt Kiều had also become more active at that moment.

Photo 1 Đặng Thúc Hứa’s Cemetery in Wat Ban Chik or Wat Thipayaratnimitre, Udon Thani (Photo by Thanyathip Sripana, February 2011)

Though Hồ Chí Minh could move freely from one place to another, he had to be cautious. From 1930 onwards, the Siamese authorities became stricter with the Vietnamese, but Hồ Chí Minh had already left Siam by then. As mentioned earlier, Hồ Chí Minh and Đặng Thúc Hứa taught the Việt Kiều to respect Thai laws and culture. This was a sound strategy because wherever they were (Ban Tham, Ban Dong, Udon Thani, Nakhon Phanom, Nong Khai, or elsewhere), they gained sympathy, friendship, and help from the Siamese people and authorities.

Hồ Chí Minh’s instruction and mission in Siam greatly contributed to the Vietnamese revolutionary movement and independence. However, it is worth noting that Hồ Chí Minh’s operation was facilitated by Đặng Thúc Hứa’s efforts in gathering the Vietnamese into communities beforehand. Thanks to Đặng Thúc Hứa, many bases for long-term patriotic movements were established with the help of his compatriots—not only at Ban Tham in Paknampho, Ban Dong in Phichit, but also in northeastern Siam such as Ban Nong Bua, Ban Nong On in Udon Thani, Sakon Nakhon, Ban May in Nakhon Phanom, etc. It cannot be denied that Đặng Thúc Hứa was the center of the Việt Kiều movement in Siam, although his name has not been mentioned in Vietnam. He spent no less than 20 years in Siam from 1909 and passed away in Udon Thani in 1932. His cemetery is still in Wat Ban Chik (วัดบ้านจิก) or Wat Thipayaratnimitre (วัดทิพยรัตน์นิมิตร) in Muang district, Udon Thani.

Hồ Chí Minh Memorial Houses and the Thai-Vietnamese Friendship Village

Hồ Chí Minh’s presence in Siam has attracted attention from both the Thai and Vietnamese general public, and in particular, scholars. The researchers from the Museum of Hồ Chí Minh in Hanoi came to Thailand to conduct research in collaboration with the Việt Kiều. It has even evolved into cultural diplomacy, strengthening the relationship between the two countries. During the ceremony held at Hồ Chí Minh’s memorial house in Nakhon Phanom, Udon and that of the Thai-Vietnamese Friendship Village in Ban May, presently called Ban Na Chok, the Vietnamese ambassador evoked Hồ Chí Minh’s name on more than one occasion.

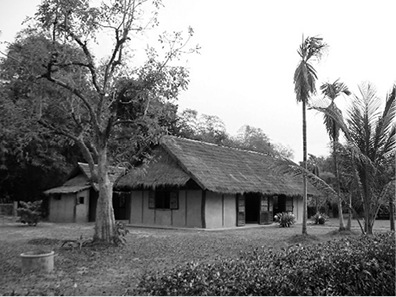

Hồ Chí Minh’s memorial house in Ban May or Ban Na Chok, Nakhon Phanom was built in the end of 2001 with the support of the Việt Kiều in Nakhon Phanom on Võ Trọng Tiêu’s land.34) It was reconstructed from his memory of the house when he was six years old. It is doubtful that a child can remember accurately the form of the house, but I was told that other elderly Việt Kiều also contributed their memories. This place, according to Võ Trọng Tiêu, was where Hồ Chí Minh stayed for a period of time in Nakhon Phanom. It was also one of the revolutionary bases in Siam. The memorial house was built to recall the presence of Hồ Chí Minh in Ban Na Chok and to strengthen Thai-Vietnamese relationship. The house at Ban Nong On in Udon was built with the same objective.

Photo 2 Hồ Chí Minh Memorial House in Ban May (Now Called Ban Na Chok), Nakhon Phanom (Photo by Thanyathip Sripana, February 2011)

Photo 3 Thai-Vietnamese Friendship Village, Ban Na Chok (Ban May), Nakhon Phanom (Photo by Thanyathip Sripana, February 21, 2004)

The Thai-Vietnamese Friendship Village in Ban Na Chok was built after the Hồ Chí Minh memorial house. It includes a small museum recounting Hồ Chí Minh’s brief stay in Siam and the itinerary of his journey to other countries after he left Vietnam in 1911. The Friendship Village does not actually have a direct connection to Hồ Chí Minh’s sojourn in Siam—it was not where he resided, neither was it used as a revolutionary base. Nonetheless, it was inaugurated by the Thai and Vietnamese prime ministers in February 2004, after the first Thai-Vietnamese joint cabinet in Đà Nẵng. The Friendship Village was built to symbolize the understanding, mutual trust, and development of relations and cultural cooperation between the two countries after the Cold War. It also signifies the recognition of the Việt Kiều by the Thai government and their integration into Thai society.

Every year, Hồ Chí Minh’s birth anniversary on May 19 is celebrated in a ceremony that is attended by the Việt Kiều from Nakhon Phanom and other provinces in Thailand, as well as by the Vietnamese from Vietnam, including those who used to live in northeastern Thailand. It is presided by the Vietnamese ambassador or consul general, and the governor of Nakhon Phanom province or other high-ranking authorities.

Another memorial house, located in the Hồ Chí Minh historical site in Ban Nong On, Udon Thani, was inaugurated by the deputy governor of Udon Thani province and the Vietnamese ambassador in Bangkok on September 2, 2006. On August 31, 2011, an educational center at the same site was inaugurated by the Vietnamese consul general and the governor of Udon Thani province. The center and the memorial house are the site of popular celebrations and an exhibition every year on May 19.

The Friendship Village and the memorial houses are visited all year round by Thai, Vietnamese, foreigners, and the Việt Kiều in Thailand, as well as by Vietnamese who used to reside in Thailand but who were repatriated to Vietnam in the beginning of the 1960s. They are called “Việt Kiều Hồi Hương,” which means the Việt Kiều who returned to their homeland.

Photo 4 Hồ Chí Minh Memorial House in Ban Nong On, Udon Thani (Photo by Thanyathip Sripana, February 2011)

Photo 5 Việt Kiều in Thailand, Vietnamese, and Thai on the Occasion of the Opening Ceremony of the Thai-Vietnamese Friendship Village, Ban Na Chok, Nakhon Phanom (Photo by a Việt Kiều, February 21, 2004)

The building of the Friendship Village and Hồ Chí Minh memorial houses in the two provinces was accomplished due to the participation and support of Việt Kiều. As a result, the Friendship Village, Hồ Chí Minh’s memorial houses, and the Việt Kiều are considered as a cultural bridge linking the people of the two countries and a strong base of the Thai-Vietnamese relationship (Thanyathip 2004a).

Conclusion

Siam was well placed to serve as an anti-colonial base in the west of central Vietnam, especially after Chiang Kai Shek’s repression of the Chinese communists in Guangdong and its repercussions on the Vietnamese anti-colonial movement. Geographically, Siam is accessible from Vietnam by land via Laos, and from southern China by sea routes.

Long before Hồ Chí Minh’s arrival in Siam, a number of patriotic Vietnamese had already settled there to carry out their mission, and a number stayed on after his departure to fulfill their task. Some of them returned to Vietnam only in the beginning of the 1960s as Việt Kiều Hồi Hương, while others died in Thailand with no chance to go back to their homeland.

It is without a doubt that Hồ Chí Minh’s instruction of his compatriots during his sojourn in Siam contributed tremendously to the struggle for Vietnamese independence. By the end of the 1920s, he had accomplished his objectives of reorganizing and strengthening the network, dispensing instruction to the Vietnamese patriotic and revolutionary movement in Siam, and participating in the founding of the communist party in the region, which was the task assigned to him by the Comintern.

Hồ Chí Minh’s presence in Siam has been recalled through the Thai-Vietnamese Friendship Village and the memorial houses in northeastern Thailand. It is a reminder to the young Vietnamese generation of the sacrifice and contribution of Hồ Chí Minh and his compatriots to their country’s independence. It also reminds Thai people that only unity and solidarity, a strong will, and a sense of sacrifice can build a strong nation.

It is hoped that this paper will contribute to studies of Hồ Chí Minh’s revolutionary activities abroad, which is part of Vietnamese revolutionary history. Though information regarding his activities in Siam is lacking, what I have gathered in this paper enables us, to some degree, to trace his whereabouts and activities in Siam. It is expected that deeper research will yield more information on this subject.

Accepted: September 7, 2012

Bibliography

Bảo Tàng Hồ Chí Minh. 2011. Hành Trình theo Chân Bác (1911–1941) [The journey following Uncle Ho’s footstep (1911–1941)]. Hà Nội: Nhà Xuất Bản Thanh Niên.

―. 2007. Những Tên Gọi, Bí Danh, Bút Danh Của Chủ Tịch Hồ Chí Minh [President Hồ Chí Minh’s names, aliases, and pseudonyms]. Hà Nội: Nhà Xuất Bản Chính Trị Quốc Gia.

Brocheux, Pierre. 2007. Ho Chi Minh. New York: Cambridge University Press.

―. 2003. Ho Chi Minh: Du révolutionnaire à l’icône [Ho Chi Minh, from a revolutionary to an icon]. Paris: Éditions Payot & Rivages.

Chan Ansuchote. 1960. The Vietnamese Refugees in Thailand: A Case Study in Decision-Making. M.A. Thesis, Thammasat University.

Chao Phraya Thipakornwongse เจ้าพระยาทิพากรวงศ์. 1983. Phra Rajaphongsawadan Krung Ratanakosin Rajakan Thi 1 พระราชพงศาวดารกรุงรัตนโกสินทร์ รัชกาลที่ 1 [The Ratanakosin royal annals of Rama I]. 5th edition. Bangkok: Khuru Sapha.

Duiker, William J. 2000. Ho Chi Minh: A Life. New York: Hyperion.

Figuères, Léo, ed. 1970. Ho Chi Minh notre camarade: Souvenirs de militants Français [Ho Chi Minh, our comrade: Remembrances of French militants]. Paris: Éditions Sociales.

Goscha, Christopher E. 1999. Thailand and the Southeast Asian Networks of the Vietnamese Revolution (1885–1954). London: Curzon Press.

Hau, Caroline S.; and Kasian Tejapira, eds. 2011. Travelling Nation-Makers: Transnational Flows and Movements in the Making of Modern Southeast Asia. Singapore: NUS Press; Kyoto: Kyoto University Press.

Ho Chi Minh. 1988. Hanoi: Éditions en Langues Etrangères.

Hồ Chí Minh Toàn Tập, Vol. 3: 1930–1945 [Hồ Chí Minh full collection, Vol. 3: 1930–1945]. 2nd edition. 2000. Hà Nội: Nhà Xuất Bản Chính Trị Quốc Gia, Xuất Bản.

Hoàng Văn Hoan. 1988. A Drop in the Ocean: Hoang Van Hoan’s Revolutionary Reminiscences. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press.

―. 1986. Giọt Nước trong Biển Cả (Hồi Ký Cách Mạng) [A Drop in the ocean: Hoàng Văn Hoan’s revolutionary reminiscences]. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press.

Lê Mạnh Trinh. 1975. Hồi Ký Cách Mạng [Revolutionary reminiscences]. Hà Nội: Tư Liệu Lưu Trữ Viện Nghiên Cứu Đông Nam Á (bản đánh máy).

―. 1961. Cuộc Vận Động Cứu Quốc Của Việt kiều ở Thái Lan [The patriotic mobilization of the overseas Vietnamese in Thailand]. Hà Nội: Nhà Xuất Bản Sự Thật.

Nghiêm Đình Vì. 2001. Bác Hồ ở Thái Lan [Uncle Hồ in Thailand]. Paper presented at conference on “25 Years of Thailand-Vietnam Relationship,” Institute of Asian Studies, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok.

Nguyễn Tài. 1965a. Mấy Mẫu Chuyện về Cụ Đặng Thúc Hứa [Some stories about grandfather Đặng Thúc Hứa]. Tạp chí Nghiên cứu Lịch sử [Journal of historian research] 79 (Oct.): 26–40.

―. 1965b. Mấy Mẫu Chuyện về Cụ Đặng Thúc Hứa. [Some stories about grandfather Đặng Thúc Hứa]. Tạp chí Nghiên cứu Lịch sử [Journal of historian research] 80 (Nov.): 40–46.

Onimaru, Takeshi. 2011. Living “Underground” in Shanghai: Noulens and the Shanghai Comintern Network. In Travelling Nation-Makers: Transnational Flows and Movements in the Making of Modern Southeast Asia, edited by Caroline S. Hau and Kasian Tejapira, pp. 96–125. Singapore: NUS Press; Kyoto: Kyoto University Press.

Quinn-Judge, Sophie. 2002. Ho Chi Minh: The Missing Years. California: University of California Press.

Sơn Tùng. 1993. Con Người và Con Đường [People and pathways]. Hà Nội: Nhà Xuất Bản Văn Hóa-Thông Tin.

Sukpreeda Bhanomyong ศุขปรีดา พนมยงค์. 2006. Ho Chi Minh: Thepphachao Phu Yang Mee Lomhaijai โฮจิมินห์ เทพเจ้าผู้ยังมีลมหายใจ [Ho Chi Minh: A living legend]. Bangkok: Mingmitre Publishing house.

T. Lan. 1976. Vừa Đi Đường Vừa Kể Chuyện [Walking and talking]. Hà Nội: Nhà Xuất Bản Sự Thật.

Thanyathip Sripana. 2005. The Vietnamese in Thailand Who Returned to Their Homeland. Journal of Science 4E: 83–94.

―. 2004a. The Vietnamese in Thailand: A Cultural Bridge in Thai-Vietnamese Relationship. Paper presented at the 2nd International Conference on Vietnamese Studies, Ho Chi Minh City, July, 14–16.

―. 2004b. Cộng Đồng Người Việt Nam ở Đông Bắc Thái Lan [Vietnamese community in Northeast Thailand]. Tạp chí Nghiên cứu Đông Nam Á [Journal of Southeast Asian studies] 4(67): 68–73.

―. 2003. Bao Giờ Mới Được Nhập Quốc Tịch Thái Lan? [When will they be granted Thai citizenship?] Tạp chí Nghiên cứu Đông Nam Á [Journal of Southeast Asian studies] 4(61): 80–84.

―. 2001. 25 Năm Thiết Lập Quan Hệ Ngoại Giao Thái Lan [25 years of Thai-Vietnamese relationship]. Tạp chí Nghiên cứu Đông Nam Á [Journal of Southeast Asian studies] 6(51): 77–79.

Thanyathip Sripana ธัญญาทิพย์ ศรีพนา; and Trịnh Diệu Thìn. 2005. Viet Kieu Nai Prathet Thai Kab Khwam Samphan Thai-Vietnam เหวียตเกี่ยวในประเทศไทยกับความสัมพันธ์ไทยเวียดนาม [Viet Kieu in Thailand in Thai-Vietnamese relationship]. Bangkok: Sriboon Computer and Publishing.

Trần Đình Lưu (Trần Đình Riên). 2004. Việt Kiều Lào-Thái với Quê Hương [Lao-Thai overseas Vietnamese and their homeland]. Hà Nội: Nhà Xuất Bản Chính Trị Quốc Gia.

Trần Dương. 2009. Cuộc Hành Trình Của Bác Hồ Trên Đất Thái Lan [The journey of Uncle Hồ in Thailand]. Hà Nội: Nhà Xuất Bản Văn Hóa-Thông Tin.

Trần Ngọc Danh (Biên soạn). 1999. Bác Hồ ở Thái Lan [Uncle Hồ in Thailand]. Thành Phố Hồ Chí Minh: Nhà Xuất Bản Trẻ.

1) Hồ Chí Minh (May 19, 1890–September 2, 1969), was named Nguyễn Sinh Cung by his family, then Nguyễn Tất Thành. Later he was known as Nguyễn Ái Quốc. He was Prime Minister (1945–55) and President (1945–69) of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam). He was a key figure in the formation of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in 1945, as well as the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) and the Việt Cộng during the Vietnam War until his death in 1969. He led the Việt Minh independence movement from 1941 onward.

2) These people were repatriated from Thailand to Vietnam between 1960 and 1964 under the Agreement between the Thai Red Cross Society and the Red Cross Society of Democratic Republic of Vietnam concerning the Repatriation of Vietnamese in Thailand to the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. See Chan (1960); see also Thanyathip and Trịnh (2005).

3) Việt Kiều means “Overseas Vietnamese.” Việt Kiều Hồi Hương means “Overseas Vietnamese who returned to their homeland.”

4) For example, Sơn Tùng’s health condition has been fragile for some years now. On November 8, 2011, I paid Trần Đình Lưu or Trần Đình Riên (whom I call Chú Riên, meaning Uncle Riên) a visit. I waited for ages in front of his house but found out later that he had passed away in August 2011. As a former member of the Bureau of External Relations which was under the Central Committee of the Vietnamese Communist Party, and as a Việt Kiều who returned from Nakhon Phanom and lived for a long time in Vietnam, Uncle Riên was very informative and had many contacts with the Việt Kiều Hồi Hương in Vietnam. He had worked at the Embassy of Vietnam in Bangkok for at least four years. Perfectly fluent in the Thai language, he served as translator for Vietnamese Prime Minister Phạm Văn Đồng and Thai Prime Minister Kriengsak Chamanand during the former’s visit to Bangkok in 1978. I am tremendously grateful to him for his contribution to my research over a period of 10 years. He was an invaluable fount of information for whom I have the greatest respect. Hoàng Nhật Tân, Hoàng Văn Hoan’s son, has also been very helpful regarding his father’s and Hồ Chí Minh’s activities in Siam. He has been inactive due to his weak health condition and as of November 2011 is staying in a medical care center for the elderly in Hanoi.

5) The name of the country was changed from Siam to Thailand in 1939.

6) Wat Annamnikaya is located not far from the Bangpho intersection.

7) Paknampho (ปากน้ำโพ) is presently in Nakhon Sawan (นครสวรรค์).

8) Đặng Quỳnh Anh, also known as Bà Nho or Bà O, was Đặng Thúc Hứa’s cousin. She is not Đặng Thúc Hứa’s daughter as mentioned in some books. She arrived in Siam in 1913 to help Hứa form a base and take care of children in Ban Tham, Paknampho in Nakhon Sawan (Sơn Tùng 1993). I had the opportunity to talk to Đặng Quỳnh Anh’s niece, Đặng Thanh Lê, in November 2011 and July 2012 at her house in Hanoi. She confirmed that Đặng Quỳnh Anh was Đặng Thúc Hứa’s cousin. A brave woman, she sacrificed her life for the salvation of her homeland for 40 years in Siam. She took care of the youth who arrived from Vietnam and taught Vietnamese children in Ban Tham, Nakhon Sawan and Ban Dong, Phichit. Con Người và Con Đường describes her life very well—the activities she conducted and the difficulties she faced in Siam. She was sentenced to 20 years of imprisonment on communist charges (according to the 1933 Act Concerning Communism). She was imprisoned for 10 years in Thailand. Upon her release, she was invited by the Communist Party of Vietnam to return home in 1953. She spent the rest of her life until 1976 or 1977 in Vietnam. She is survived by three children. Đặng Quỳnh Anh was admitted as a member of the Communist Party of Indochina when she was in Khon Kaen in April 1934. She became a member of Duy Tân Hội in 1908, as well as of Quang Phục Hội. In 1926, she joined the Vietnamese Revolutionary Youth League (Việt Nam Thanh Niên Cách Mạng Đồng Chí Hội) at its Ban Dong branch (ibid., 188; interviews with her first son, Võ Thung, between 2002 and 2011).

9) Road No. 9 was used by most of the Vietnamese, including patriots who fled the French after the Nghệ-Tĩnh incident in the beginning of the 1930s. Road No. 9 connects Đông Hà town in Quảng Trị in central Vietnam to Kaison Phomvihan town in Savannakhet, and then to Mukdahan in northeastern Siam or Thailand. The distance from Đông Hà town to the Lao Bảo border gate at the Vietnam–Laos border is 84 km, while the distance from this border to Kaison Phomvihan town in Sawannakhet province is 240 km.

10) Đặng Thúc Hứa was born in 1870 in Lương Điền village, Thanh Chương district, Nghệ An province. He realized that in order to fight against the French, the Vietnamese should rely on themselves, not on other countries, and that Siam was a good place to develop Vietnamese revolutionary bases. He went to the places in Siam where the Vietnamese resided and gathered them into a community. With his friends, he established bases for long-term patriotic movements. The first community was in Ban Tham, Paknampho, which was used as the center of the movement in the beginning of 1910s. There, they built farms and trained youths. He realized that the revolution was a long-term struggle and that it was necessary to create a future generation of comrades and nationalists. As he was concerned about illiteracy among the Việt Kiều children, he and others built schools, mobilized Việt Kiều to send their children to school, and also welcomed children from Vietnam. Đặng Thúc Hứa and his compatriots organized classes for children in language, morality, and patriotic consciousness.