Beyond the Colonial State: Central Bank Making as State Building in the 1930s*

Takagi Yusuke**

** The writer revised this paper as a part of the writer’s Ph.D. dissertation, “Nationalism in Philippine State Building: The Politics of the Central Bank, 1933–1964,” which was submitted to the Graduate School of Law and Political Science, Keio University in October 2013.

** 高木佑輔, GRIPS, National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies, 7-22-1 Roppongi, Minato-ku, Tokyo 106-8677, Japan

e-mail: y-takagi[at]grips.ac.jp

DOI: doi.org/10.20495/seas.3.1_85__8211_1

The purpose, origin, and strength of the Central Bank of the Philippines remain a puzzle for students of the Philippine political economy. Trade policy and fiscal policy have been well studied within the theoretical framework of a weak state, but the politics of monetary policy have curiously been overlooked. As it happens, the bank enjoyed an excellent reputation as “an island of state strength.” This paper sheds new light on the politics of economic policies by arguing that monetary policy introduced a new type of politics in the 1930s. This was a period during which a network of Filipino policy makers emerged and became an incubator for other leading policy makers in the early years of the Republic of the Philippines. Established politicians such as Manuel L. Quezon and American colonial officers paid scant attention to monetary policy reform, while these policy makers shouldered the responsibility of policy proposals. Their proposal to establish a central bank went beyond the monetary policy mandate, because they aimed to depart from the conventional market-governed colonial economic structure to a managed currency system backed by economic planning. By focusing on their attempts, this paper reveals that while the emergent crop of Filipino policy makers were beneficiaries of the colonial state, they were not satisfied with colonial economic policies and worked toward building an independent state equipped with qualified institutions.

Keywords: colonial state, Central Bank of the Philippines, state building, nationalism, politics of economic policy

Introduction

The process of the setting up of the Central Bank of the Philippines remains a puzzle for students of the Philippine political economy. Existing studies, including those done by the bank’s first governor, Miguel P. Cuaderno, reveal that Cuaderno, who was responsible for designing the bank when he was the secretary of finance, enjoyed a cooperative working relationship with influential politicians (Cuaderno 1949; 1964; Valdepeñas 2003). The bank, after its establishment in 1949, was regarded as “an island of state strength in an ocean of weakness [of the state apparatus]” (Abinales and Amoroso 2005, 184). Not a few scholars, however, have argued that politicians representing an oligarchic society prevented the government from achieving efficient rule through bureaucracy—in other words, the state in the Philippines was weak (see, for example, Hutchcroft 1998). How could bureaucrats establish constructive relations with politicians to form solid institutions, such as the Central Bank, in the midst of a weak state?

Few studies have been undertaken on the politics of the formation of the Central Bank. Citing Cuaderno (1964) in a column, Abinales and Amoroso indicate that he played a pivotal role in the management of the bank (2005, 184). Cuaderno himself wrote two significant books (1949; 1964) but did not provide enough information on the political process of the formation of the bank. A historical study by a prominent economist, Vicente Valdepeñas (2003), on the development of central banking is helpful but does not pay much attention to the political context within which policy makers had to operate.1)

One exceptional study is Nick Cullather’s diplomatic history on the Central Bank and its policies from the 1940s to the 1950s, in which he asserts that the US government supported the establishment of the Central Bank of the Philippines, while the Philippines did not necessarily share the policy goal to create the bank (Cullather 1992). Cullather asserts that Filipino policy makers viewed the bank as a symbol of sovereignty, and yet he does not touch upon the domestic politics of the time. Instead, his study highlights the discrimination against Chinese and US businesses, the failure of the bank’s developmental policy, as well as graft and corruption in the 1950s (ibid.), as if these were the main targets that Filipinos aimed to achieve. The hypothetical argument we can draw from his description is that the US government was the only serious actor reluctantly sustaining the Central Bank in order to protect and promote its own interests in the US military bases in the Philippines.

The US influence on Philippine economic policy-making should not be overemphasized or misunderstood. Cuaderno gives an impressive account of the Joint Philippine-American Finance Commission, which officially recommended the establishment of a central bank to the Philippine government in its report published in 1947 (JPAFC 1947, 46–53; Cuaderno 1964, 9–11). However, what actually happened is that in a series of commission meetings the Filipino members had to refute the claims of the American members, who opposed the idea of setting up a central bank. The Filipino members eventually prevailed on the American members, gaining support from President Manuel A. Roxas, who was not a member of the commission (Cuaderno 1964, 9–11; Valdepeñas 2003, 85). In addition, several studies have emphasized US expansionist or imperialist attempts and actual interventions into Philippine affairs (e.g., Constantino and Constantino 1978; Jenkins 1985; MacIsaac 1993, Ch. 7, 9; Golay 1997).

A brief review of the literature demonstrates that the stage of Philippine-US relations was peopled by complicated actors. First, American residents who still maintained their influence on the colonial authority in Manila and on Filipino politicians opposed independence (MacIsaac 1993; Golay 1997). Second, Americans who supported the independence of the Philippine Islands were divided into two groups: the “isolationists” and the “internationalists” (MacIsaac 1993). While the isolationists in Congress endorsed cutting off relations with the colony as soon as possible, the internationalists in the US government did not hesitate to intervene in the domestic politics of the Philippine Islands so that the Philippines would establish an independent government (ibid.). Third, the internationalists paid a great deal of attention to the fiscal discipline of the Philippine Insular government (Golay 1997: 330–332),2) although some of them gradually accepted the protectionism of the Philippine government (Doeppers 1984, 29). Filipino policy makers, therefore, though they might have learned from the US experience, could not depend for support on the United States. Moreover, they had to deal with pressure from Manila Americans who were not in favor of the independence of the Philippine Islands. Their roles should be seriously analyzed.

Early attempts to establish a central bank gave an impetus to the politics of economic policy. Three major changes—in terms of actors, ideas, and political contexts—need to be examined. First, social change under colonial rule introduced a colonial middle class. By the beginning of the 1930s many professionals, such as colonial bureaucrats, lawyers, and professors, formed part of the colonial middle class (Doeppers 1984). The expansion of educational opportunities at all levels, and the Filipinization of bureaucracy, especially under the Francis B. Harrison administration (1913–21), created a colonial middle class in Manila who established their careers in white-collar jobs (ibid.). In fact, several delegates at the Constitutional Convention in 1934 belonged to the new generation of professionals, and therefore the convention could be assumed to be a “national congress” whose representatives had different antecedents from the traditional elites (Uchiyama 1999, 201).

Second, the members of this emerging colonial middle class expounded new ideas in their discussions at the Constitutional Convention (De Dios 2002). The inflow of international policy ideas such as economic nationalism (Aruego 1937, 658–669) and a strong presidency (De Dios 2002) greatly influenced the delegates. It is to be noted that, however sensational and well accepted at the convention, the idea of an international inflow of ideas was still taboo in the existing interest structure that had shaped the patronage politics that Manuel L. Quezon, the tycoon of colonial politics, made the best use of (McCoy 1988).3)

Third, we cannot overlook the fact that the formation of the Constitutional Convention was a part of the Filipino effort toward state building. US colonial rule had brought into the Philippine Islands both political machines and politics by reformers (Abinales 2005).4) While the former were characterized by patronage politics, the spoils system, and a cautious attitude toward the expansion of the influence of the federal government, the latter were led by those who aimed at overcoming political machines by strengthening the administrative capacity of the federal government in the United States (ibid.). While Quezon established his career making the best use of patronage politics (McCoy 1988), the aforementioned middle class apparently emerged from the latter aspect of the US influence, or the effort toward state building. A series of US policy changes, including the passage of the independence act in the 1930s, prompted Filipino policy makers to recognize the necessity to work for state building themselves, because the policy changes in the United States took place without consideration for the situation in the Philippines, as we will see below.

In a nutshell, this paper demonstrates that the emerging professionals, international inflow of policy ideas, and resurgence of nationalism motivated a handful of powerful Filipino policy makers to strive to establish a central bank. Although their proposals failed to materialize before independence, the policy makers elaborated on the idea and succeeded in establishing the bank in 1949. Through a study of the early attempts, this paper explores the ideas among policy makers in the 1930s that would result in the creation of the Central Bank in the 1950s. The first section examines the origin of the idea through a study of the first initiatives from 1933 to 1935, when US policy changes prompted Filipino policy makers to recognize the necessity of autonomy. The second section, covering the period from 1935 to 1944, analyzes subsequent political contexts where the key advocates continued to work for their goals despite indifference and opposition from government authorities.

I Independence Act, Monetary Policy Change in the United States, and a Central Bank, 1933–35

I-1 First Independence Act and Creation of the Philippine Economic Association in 1933

The passage of the Hare-Hawes-Cutting (HHC) Act in the US Congress in 1933 led to a political power struggle among leaders of the dominant Nacionalista Party, with Senate President Quezon on one side and Senator Sergio Osmeña and Speaker Manuel A. Roxas of the House of Representatives on the other.5) The power struggle was an opportunity to consider the economic consequences of independence. Opposing the HHC Act in a speech, Quezon described it as a tariff act rather than an independence act (Golay 1997, 320). He said: “All I can say for the present is that the National City Bank [of New York] took an active interest in the passage of the Hawes-Cutting bill, . . .” (Tribune, January 1, 1933, 1, 19).6) He argued that the National City Bank worked for the passing of the HHC Act in order to protect Cuban sugar at the expense of Philippine sugar (ibid., 1; Golay 1997, 320). Quezon’s attack was so harsh that a split in the party was inevitable in early January 1933 (Tribune, January 3, 1933, 1).

Quezon expressed his opposition to the HHC Act on various occasions. When he was invited by a group of economists on March 17, 1933, he argued that the economic features of the act were so unfavorable to the Philippine Islands that social unrest could result in the rebirth of the military government rather than a commonwealth government (Tribune, March 18, 1933, 1). He explained that when the United States imposed the full tariff rate on Philippine sugar three years after the passing of the act, the US market would be virtually closed to Philippine sugar; this would precipitate the collapse of the export industry and be followed by massive unemployment, social unrest, and ultimately another military suppression by the United States (ibid.).

The group of economists who invited Quezon seemed to have been the founders of the Philippine Economic Association (PEA). The following three points support this assertion: first, Cuaderno points out that the PEA was organized after the passage of the HHC Act (Cuaderno 1949, 1). Second, the presiding officer of the day was Elpidio Quirino, who would have been the president of the PEA (Tribune, March 18, 1933, 2; PEA 1934).7) Third, the PEA’s first two publications indicate its gradual development as an organization from March 1933 (PEA 1933; 1934). Who, then, were the members of the PEA?

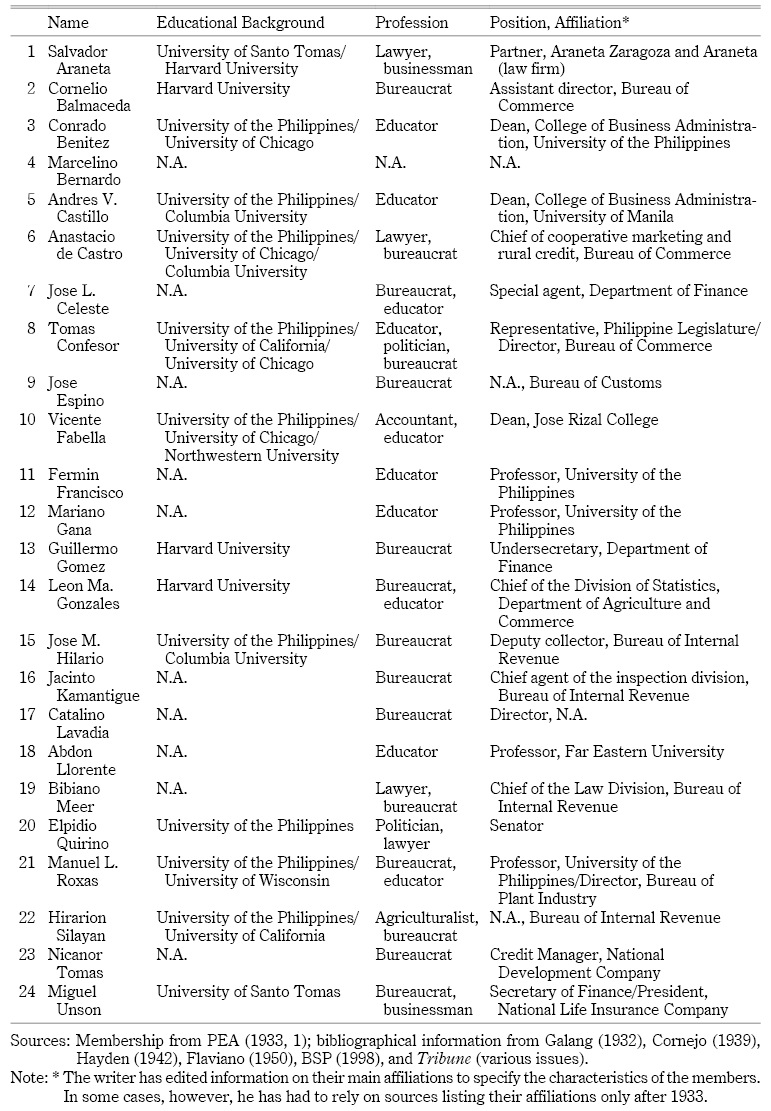

Table 1 is a compilation of biographic data about the founding members whose names were recorded in the first publication of the PEA (1933, I). From Table 1 we can glean three characteristics of the members. First, the only politician was Quirino, although some members had seats in the legislature. Second, the majority were bureaucrats with no visible representatives from any particular industry. Third, most of the members either studied economics or worked for administrations covering economic issues, and almost half of them went to the United States to study. All these points reflect the political as well as social developments under US colonial rule. These points are elaborated on below.

First, Quirino’s political career reflected the shifting phases in the politics of independence. Quirino, born in 1890 in Ilocos Norte, graduated from the University of the Philippines and became a public school teacher, a law clerk of the Philippine Commission, a legislator, and finally a senator. He was younger than Quezon by 12 years and established his political career under Quezon’s tutelage after he met the latter at the Philippine Columbian Club (Gwekoh 1949, 23). When Quirino was a clerk of the commission he also worked as a secretary of the club to get acquainted with the leading figures of the day (ibid.). Once he was elected to the Senate in 1925, he was appointed by Quezon as chairman of the Committee of Accounts and subsequently as chairman of the Special Committee on Taxation, because “a majority of lawyers of the old school [in the Senate] depended not only on the vigor of their young colleagues but on the steady flame of their mid-night lamps [to study the new problems of economics]” (ibid., 31–32).8) Quirino became so familiar with economic policy that he was referred to as the “high priest of protectionism” in a personal sketch published in the 1930s (Cabildo 1953, 13). Quirino, as well as Roxas—whom we shall study in the next section—belonged to the generation for whom the economic consequences of independence became an agenda, while Quezon and Osmeña belonged to the generation for whom independence itself was the prime concern.

Second, 15 of the 24 PEA members were former or incumbent bureaucrats working in various departments in charge of economic policy. For instance, Miguel Unson, born in Iloilo in 1877 and a graduate of the University of Santo Tomas, was a prominent bureaucrat who had been a provincial treasurer as well as an undersecretary and secretary of finance (Cornejo 1939, 2193). In addition to him, incumbent Undersecretary of Finance Guillermo Gomez was an original member. There were many members who must have had firsthand information of fiscal conditions as officers of the Bureau of Internal Revenue or Customs, both of which were supervised by the Department of Finance. Meanwhile, Tomas Confesor and Cornelio Balmaceda were director and assistant director of the Bureau of Commerce, which was supervised by the Department of Agriculture and Commerce. The PEA functioned as a network of bureaucrats from various economic agencies of the government.

While bureaucrats occupied the majority of seats, the business sector was represented by a few individuals as well. Salvador Araneta, born in Manila in 1902, studied at Harvard University and became a partner in a law firm in the Philippines. The businesses he engaged in included the National Railroad Company, a sugar firm, and several mining companies (ibid., 1602). He was not a representative of any particular industry but was a very active member of the Philippine Chamber of Commerce. He eventually joined in the founding of the National Economic Protectionism Association (NEPA) in 1934.9) Unson became another prominent representative of the business sector when he shifted to the insurance industry, but, as mentioned above, he established his early career as a bureaucrat.

Third, all PEA members shared a knowledge of economics. They learned economics either through education in school or from the school of hard knocks. A member of the PEA, Professor Abdon Llorente of Far Eastern University wrote a column in which he described the dawn of economics in the Philippines (Llorente 1935). The column suggested that the PEA included most of the pioneering economists of the time, although it did not mention the association directly. Llorente, for instance, praised Dean Conrado Benitez of the College of Business Administration from the University of the Philippines, together with Confesor, Vicente Fabella, Fermin Francisco, and others as “men who crossed the sea in the early days of American regime to delve into the intricacies of economics” (ibid., 16). Andres V. Castillo, who was born in 1903 and earned his bachelor’s degree from the University of the Philippines and his doctorate from Columbia University, followed the path of these men and joined the PEA. He was the dean of the College of Business Administration in the University of Manila in 1934 (Tribune, August 19, 1934, 17; BSP 1998, 37). Meanwhile, Llorente praised Unson, who led a group of practitioners, including Gomez, because they “began the study of economics from the so-called university of hard knocks” (Llorente 1935, 16). He also commended Quirino as the one “who can easily lead to [sic] the oldsters as well as the youngsters” and “who has in him the making of a Hamilton” (ibid.).

With regard to their education, at least half the PEA members studied in the United States—either through private funding or on a scholarship from the government. Recipients of the latter were called pensionados. Llorente described it thus: “The pensionado system, which was discontinued about 1910, was resumed in 1919. From 1919 to 1930, 379 students were sent by the government to the United States.10) Of this number, 58 took up the study of different branches of economics. . . . These returned pensionados are now employed as follows: 21 as government employees, 7 as teachers, 1 as a practicing attorney, 3 as actuaries, 3 as life underwriters, 2 as newspapermen, 7 in business and 2 as farmers” (ibid.). The pensionados were selected beneficiaries of the colonial policy and organized their own social club, known as the Philippine Columbian Club, in 1905.11)

As the following section shows, however, their experience in the United States did not turn them into pro-US economists. Carlos Quirino, a leading postwar journalist, asserts that pensionados became even more nationalistic because of their stay abroad and that “this [Philippine Columbian] club became the focal point in the nationalistic campaign for independence for the next three decades” (Quirino 1987, 39). Quezon, in fact, delivered the aforementioned critical speech on the HHC Act at a luncheon meeting of this club. In this context, it is intriguing that Llorente encouraged Filipinos to go to the United States, referring to Americans who had studied economics in Germany or Austria-Hungary in the last century. He praised Quirino as a man who understood Alexander Hamilton, who was US Secretary of the Treasury during the George Washington administration (Llorente 1935, 13). The German school of economics in the nineteenth century, which was influenced by the ideas of Hamilton, was famous for its nationalist orientation wherein scholars were skeptical of the effectiveness of free trade for newly independent nations (Lichauco 1988, 32–49).

Those who established the PEA adopted the idea of positive role of regulation in economic activities by the government, which the American Economic Association (AEA) advocated since the end of the nineteenth century (Skowronek 1982, 132), although neither Llorente nor Lichauco mentioned the name of the AEA. AEA was in fact established by the American economists who were skeptical to American Social Science Association which tended to advocate the idea of laissez-faire (ibid.). In fact, names such as (Johann G.) Fichte or Friedrich List, who were German nationalists, especially the latter, and pioneers of the German school of economics (Lichauco 1988, 44–49), were mentioned in a speech by the well-known Filipino businessman Benito Razon. Razon was the founding president of the NEPA, for which Llorente later worked as a manager (Tribune, February 10, 1935, 17; May 29, 1935, 16).

The PEA members were, however, not yet radical in their first publication, The Economics of the Hare-Hawes-Cutting Act: An Analysis (hereafter, An Analysis), where they criticized the independence act instead of proposing their own economic policy (PEA 1933). In I, “The National Bonded Indebtedness,” they studied the Philippine government’s fiscal stability as well as its ability to redeem bonds and concluded, “The present sinking fund arrangement is sufficient to guarantee the ultimate redemption of the Philippine government bonds, and any additional guarantee for their redemption, like the export tax, is not superfluous but is also harmful to national interests” (ibid., 5). They focused on the adversarial effect of export tax, which the HHC Act required the Philippine government to impose. In the subsequent two sections, which devoted 28 of the total 40 pages to the topic (II, “The Export Tax,” and III, “Effects of Limitations Imposed on Foreign Trade”), they reiterated that the Philippine government could pay its obligation and that it would be faced with difficulty once it was compelled to impose export tax.

The authors criticized the HHC Act as if they were aiming to maintain the status quo, although (or perhaps because) they recognized the fragility of the existing economic structure. While they admitted that free trade between the Philippine Islands and the United States had contributed to the rapid expansion of export industries such as the sugar industry, they argued that “development [of the export industries] has stood on a weak and unstable foundation. Its ultimate effect has been to place the Islands in a state of almost complete dependence upon the United States market” (ibid., 8). They did not yet argue that the Philippines should change its economic structure.

Reflecting the conservative tone of other sections, the authors did not advocate any radical proposal in IV, “Currency.” Here they concluded, “As long as the present free trade . . . remains the same there is hardly any need for autonomy in currency legislation because goods like anything else follow the line of least resistance” (ibid., 38). They hypothetically mentioned that the Philippines would need to depreciate its currency to seek new export markets in Asia, especially if it could no longer export its products to the US market (ibid.). The authors recognized that “it is necessary to have our currency at our absolute and free control to provide us with one of the instrumentalities for establishing markets in other countries. We cannot ‘remain on a gold island in the midst of a sea of depreciated currency’” (ibid.). They knew what they needed to do once the current arrangement was abandoned, but they did not present their own comprehensive policy proposal yet.12)

The critical but conservative tone of An Analysis apparently reflected the political position of Quirino, who was close to Quezon. On the same day that Quezon delivered his speech, Quirino “declared that the Hawes-Cutting-Hare Act is a challenge to the Filipinos” (Tribune, March 18, 1933, 2). It is, however, more important to remember the origin of An Analysis. The PEA responded to a US policy change and limited its activity to the issue involved. Another US policy change would prompt the PEA to work on another issue. But before we study the PEA’s next activity, we examine an official response from within the government to the US policy change.

I-2 The Gold Embargo in the United States and the First Proposal to Establish a Central Bank in the Philippines, 1933–34

The year 1933 is pivotal not only because of the HHC Act but also because of a drastic change in US monetary policy. Faced with a series of banking crises after the Depression, American President Franklin D. Roosevelt “had grown convinced that ending the Depression required raising prices to their 1929 level” (Eichengreen 1992, 331). Roosevelt, pressured by Congress to adopt a more radical proposal for inflation, placed an embargo on gold exports and endorsed the Thomas Amendment authorizing the president to take various inflationary measures on April 19, 1933 (ibid., 331–332). This piece of news was sensationally reported in the Philippines (Tribune, April 21, 1933, 1).

The Filipino populace attempted to understand the implications of the US measures by turning to the knowledge of professionals. Castillo’s remark was, for instance, published as an explanation by a “Filipino political economist” (Tribune, April 23, 1933, 5). The latter wrote in a relatively pedagogic manner that inflation would stimulate the domestic economy although there was a risk that it could result in hyperinflation, such as that experienced in Germany in 1923 (ibid., 5, 25). In the context of our study, it is more interesting that he briefly mentioned, “It cannot be overemphasized that a managed Philippine currency would serve the country best at this time. . . . Unfortunately there is no central bank in the Philippines upon which the task of managing the currency could be very well entrusted” (ibid.). Although it took some time before the currency issue was connected to the issue of central banking, there was a gradual development of the policy proposal within the government.

Acting Secretary of Finance Vicente Singson-Encarnacion (hereafter, Singson) took the lead in handling the situation. Singson was also mentioned as a pioneer of economics by Llorente (1935, 16) and would be a significant advocate for the formation of a central bank. He was born in 1875 in Ilocos Sur, graduated from the University of Santo Tomas, passed the bar examination, and became a fiscal (public prosecutor) of provincial governments, a representative of the Philippine Assembly, as well as a senator (Cornejo 1939, 2143). His career path was seemingly similar to that of his contemporaries, such as Quezon and Osmeña, but it differed from them in two ways. First, he was in the minority in the legislature as a member of the Federal Party (Quirino 1987, 44), although he maintained close relations with American colonial officers and was a member of the Philippine Commission from 1913 to 1916. The second point that distinguished Singson’s career from Quezon’s and Osmeña’s was his experience in private business. He was an entrepreneur in the insurance and finance industry. He worked for the Insular Life Assurance Company (Insular Life) first as a director and later as the president (Tribune, August 15, 1934, 16). He also worked for the Philippine National Bank (PNB) as a director (Willis 1917, 418; Nagano 2003, 226). These two institutions are significant in the historical development of the finance industry in the Philippines. While Insular Life, founded in 1910, was the first Filipino-owned life insurance company (Batalla 1999, 22), the PNB, founded in 1916, was the first multipurpose government bank. It functioned as an agricultural financial institution, a commercial bank, and a bank of issue (Nagano 2003, 197–198). Singson achieved a great deal in business and was appointed as secretary of agriculture and commerce on January 1, 1933.

Agriculture and Commerce Secretary Singson promoted local production and domestic commercial activities through the Bureau of Commerce, which his department oversaw. Under his leadership, the government established the Manila Trading Center and organized the first “Made in the Philippines Products Week” in August 1933 in order to promote local production and domestic trade (Stine 1966, 85). Balmaceda, a member of the PEA and assistant director of the Bureau of Commerce, said that Secretary Singson took the initiative to organize the Products Week and to establish the center (Tribune, December 30, 1933, 6).

Singson was concurrently appointed as acting secretary of finance on April 21, 1934, after Rafael Alunan, a representative of the sugar industry, resigned from the post (Tribune, August 15, 1934, 16). In the Finance Department, Singson took the initiative to reduce Philippine dependence on the US economy. Informed of a possible change in the Philippine monetary system from the gold exchange standard to the dollar exchange standard in June 1934, he expressed his serious concerns about its “harmful” effect on the Philippines (Singson to Governor-General, 1933, JWJ, 2).13) In a memorandum dated July 6, 1933, he commented on the following two points: first, he argued that it was undesirable to link the Philippine currency system to the US one “much more intimately” (ibid.). He was worried about a situation where the Philippine currency would become more vulnerable to US currency policy, since the latter was managed regardless of Philippine conditions. Second, he believed that US inflationary measures would adversely affect the Philippine economy. He asserted, “In many cases, the likelihood is that this country would be the loser in the sense that its currency would depreciate in value . . .” (ibid.). Based on these considerations, he proposed inviting a monetary expert to consider whether the Philippine Islands should establish an independent monetary system or not (ibid.).

Singson aimed to gain autonomy for economic policy-making through the independent currency system. In another memorandum to the governor-general on August 5, 1933, he suggested that the Philippine government establish a monetary system sustained by the gold bullion standard rather than the dollar exchange standard. He also proposed that the government devalue the peso by half the current ratio (Quirino to Governor-General, 1935, JWJ, 2–5). The Philippine government had a gold exchange standard that functioned through gold deposits in New York prior to April 1933. Meanwhile, Singson proposed the establishment of a gold bullion standard, which required the government to establish a totally new monetary standard.14) The other proposal, devaluation, was heading in the same direction of reducing Philippine dependence on the United States because it would encourage Philippine exports to other countries.

While Singson continued to appeal for the services of a monetary expert, he made another policy proposal: founding a central bank in the Philippines (MacIsaac 2002, 159). After he came back from the United States, where he joined Quezon’s last independence mission, he publicly “advocated the separation of the control over the monetary system from the government, and the establishment of a central bank to assume such control under the government supervision” in a speech at a banquet for Singson and Unson on May 17, 1934, hosted by the Chamber of Commerce of the Philippine Islands then headed by Eugenio Rodriguez (Tribune, May 18, 1934, 1, 7). The proposed central bank, according to him, should be a bank of the government, a bank of banks, and a bank whose responsibility was to manage the integrity and stability of the national currency.

The benefits Singson emphasized were the bank’s contributions to fiscal discipline and the expansion of commercial credit (ibid., 7). He argued that because the democratic government tended to carry out inflation-oriented policies to gain support from the people, the commonwealth government would not be able to resist the temptation to fall into inflationary finance unless it directly managed its currency policy (ibid., 1, 7). With regard to the credit market, he recognized the existence of doubts over the usefulness of a central bank at a time when the credit market had not yet fully matured. He argued, though, that “there is no better instrument to develop credit in a nation than the establishment of a central bank” (ibid., 7). Under the circumstances, what was the basis for his conviction?

In the speech mentioned above, Singson brought up the emerging international policy idea of establishing a central bank. He said, “The body of financial experts and economists of the League of Nations, about five years ago, had recommended the establishment of central banks where such banks do not exist” (ibid.). The Financial Committee of the League of Nations founded a Gold Delegation to conduct research on problems of the gold standard in 1929 and published the results of the research in several reports from 1930 (Eichengreen 1992, 250; Sudo 2008, 2–3). After World War II, European countries and the United States attempted for more than a decade to establish a systematic cooperation to respond to international monetary problems (Eichengreen 1992, Ch. 6–7). They failed to resolve the problems but held several conferences and published reports with recommendations. Regardless of the results of the efforts of the League of Nations, Singson used the recommendations for his proposal. Drawing examples from other countries, Singson also emphasized the necessity of establishing an independent central bank, citing responsibilities that the existing PNB could not fill. He argued that a central bank should be independent of the government and that the PNB should concentrate on long-term finance for the development of agriculture as in the case of Greece (Tribune, May 18, 1934, 7). He elaborated his proposal through a study of the recommendations of international organizations or cases from other countries.15) It is obvious that he was determined that the Philippines prepare the institutions necessary for an independent state.

In addition to these proposals, Singson expressed his interest in economic planning so as to change the economic structure of the Islands. On another occasion, he pointed out that “excessive attention was given to the development of the sugar industry while practically abandoning the other industries, so that when the crisis came in sugar, the country faced a great economic difficulty. . . . What is lacking, he said, is a plan” (Tribune, June 13, 1934, 1, 11). He clearly recognized and publicly announced the necessity to change the economic structure, which depended too much on the sugar industry. Economic planning in this context was not only an economic preparation for independence, but also a political challenge to those who were supported by the sugar industry.

Singson’s multiple proposals to change the Philippines’ economic structure failed to receive support either from Quezon or from the influential Americans. We can hardly find a written document directly explaining Quezon’s motive but can still use the data that mention two influential groups that were close to Quezon opposed Singson’s proposals. The sugar industry, which had enjoyed easy loans from the PNB and established close relations with Quezon (Larkin 2001), opposed the idea of establishing a central bank (Cullather 1992, 81). Most American residents, or so-called Manila Americans, were beneficiaries of the existing free trade and opposed the independence of the Philippines (Golay 1997, 332–333). In the Philippine Insular government, Governor-General Leonard Wood reconstructed the currency system based on the idea of “self-regulating markets” with the least intervention from the government (Giesecke 1987, 117–124). J. Weldon Jones, who was the Insular Auditor and “a valuable adviser to [Governor-General Frank] Murphy” (Golay 1997, 331), was concurrently appointed the adviser on currency to the Governor-General almost at the same time when Singson advocated making a central bank (Tribune, June 2, 1934, 3). Jones was one of those who undoubtedly opposed Singson’s proposal, as we will see below. Singson left the government without implementing any of his proposals when Governor-General Murphy appointed Quirino as the secretary of finance and Rodriguez as the secretary of agriculture and commerce on July 14, 1934 (Tribune, July 15, 1934, 1, 7).

I-3 PEA, Economic Planning, and a Central Bank, 1934–35

Before being appointed as secretary of finance, Quirino had already reactivated the PEA. He populated the association with several additional members in November 1933 when he prepared to join Quezon’s independence mission, which Singson also joined (Tribune, November 3, 1933, 10). After the last independence mission won another independence act, the Tydings-McDuffie Act, on March 24, 1934, PEA members began to prepare for a national economic program (Tribune, April 17, 1934, 2). The members who led the discussion reflected on the fact that the association was still composed of prominent bureaucrats—Undersecretary of Finance Gomez was the presiding officer of the day, and Assistant Director of Commerce Balmaceda was the secretary of the association (ibid.).16) PEA members paid attention to Singson’s proposal and invited him for a meeting while he was still the finance secretary (Tribune, June 24, 1934, 3rd ed., 4).

Cuaderno, the then PNB assistant Manager, became active in the PEA, especially in the field of finance and banking (Tribune, November 3, 1933, 10). Cuaderno, born in Bataan in 1890, graduated from the National University, became a lawyer in 1919, and was hired at the Bureau of Supply. He transferred to the PNB in 1926 (Cornejo 1939, 1657–1658). He energetically dealt with the bank’s legal cases, specifically in its reconstruction from damage caused by the financial crisis of the early 1920s (Galang 1932, 107). Although he established his career as a lawyer rather than as an economist, he received on-the-job training in banking during his time as a working student in Hong Kong (Ty 1948). When the PEA expanded its membership, he became the vice chairman of the Committee on Currency of the PEA, headed by Chairman Unson (PEA 1934, xii).

Quirino worked for economic planning and expected PEA members to be the “new dealers for the new Philippine Republic” (Tribune, May 2, 1934, 2). The PEA, with an additional 27 members, published the results of its study and policy recommendations in the form of a 270-page book titled Economic Problems of the Philippines (hereafter, Problems) in 1934 (PEA 1934). In the preface, Quirino asserted, “Our national economic structure, with the severance of our relations with the United States, must claim our attention. A comprehensive program of economic planning for the nation is imperative. . . . it is my hope that the work of the Philippine Economic Association in this regard will be helpful in crystallizing the mind of the people on the necessity of economic planning” (ibid., iv).

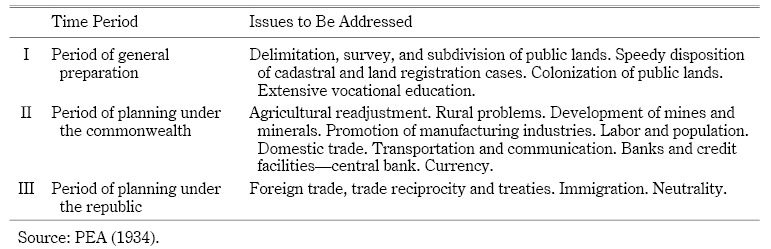

Quirino provided a time frame for his proposal and pointed out the actions to be taken during each period. Table 2 reveals the three steps Quirino had in mind before the establishment of the commonwealth, during the commonwealth period, and after independence. Before the establishment of the commonwealth, he suggested that the government focus on land issues and vocational education. During the commonwealth period, he proposed a more radical change in the economic structure, including the establishment of a central bank. After independence, he planned for the government to enhance foreign trade, to deal with immigration issues, and so on. The timetable and agenda bear testimony to Quirino’s intention to change the comprehensive economic structure of the Philippines.

In the chapter of Problems on banks and other financial institutions, the committee headed by Campos, president of the Bank of the Philippine Islands (BPI), Rafael Corpus, president of the PNB, and Cuaderno asserted that the majority of the local banks had agreed upon the idea of organizing a central bank (ibid., 219). As for the functions of a central bank, “the power of a central bank to control the currency and the credit of the country and to stabilize foreign exchange is a fact recognized by monetary and banking experts” (ibid.). Campos, Corpus, and Cuaderno argued that they should form a central bank to increase credit facilities, to stabilize foreign exchange, and to meet periodic demands for circulation through note issues, all of which would help the government achieve credit elasticity (ibid.).

In the chapter of Problems on currency, the PEA reiterated the necessity of a central bank. The committee headed by Unson and Cuaderno argued that the existing system had failed to provide enough money in 1920 and 1921 and that the Philippine Islands should have a financial organization such as a central bank. While they admitted that “The Philippines is not in a position to adopt an independent currency at this time,” they argued that “the main objective, therefore, of an independent system is an adequate management of currency” (ibid., 242). In other words, the PEA distinguished the issue of the enhancement of the banking system from that of the establishment of a new currency system.

However, it was not true that Quirino gave up on the idea of establishing an autonomous currency system through the central bank. He kept his movement confidential, because “A wide open agitation coming from above in the discussion of such a delicate matter might invite alarm and misapprehensions to so serious a degree as to shake the confidence of capital in the stability of the financial structure of the country and thus disastrously affect investments and business in general” (Quirino to Governor-General, 1935, JWJ, 13). Quirino might have abandoned Singson’s strategy but not his idea.

In a memorandum to the governor-general on January 13, 1935, Quirino argued that the Philippines should establish an autonomous currency system and quoted Singson’s proposal (ibid., 15). Quirino, following Singson’s proposal, took it for granted that the Philippines should establish an autonomous currency system based on the gold standard because, first, the Philippines was a gold-producing country, and second, because it had a simpler economic structure than the United States and other European countries (ibid., 17). He also agreed with Singson on the necessity to devalue the peso. Taking into consideration an almost 40 percent devaluation of the US dollar in January 1934, Quirino suggested a one-eighth reduction of the peso against the US dollar, which would be almost equivalent to the ratio suggested by Singson in 1933.

Quirino also proposed the formation of a central bank to conform to the international policy idea, as well as to emphasize the merits of a national economy. Like Singson, he said, “The Financial Committee of the League of Nations would entrust a new important role to central banks. It has made these specific recommendations: ‘The aim of the Central Bank should be to maintain the stability of international prices both over long periods and over short periods, i.e., they should both keep the average steady over a period of years and avoid fluctuations round this average from year to year’” (ibid., 21). He emphasized that central banks were “necessary ingredients for the promotion of economy and finance of a country” because they would lower interest rates as well as expand credit supply through rediscounting operations (ibid., 22).

Quirino, however, failed, just like Singson. The Philippine Insular government introduced Act No. 4199 on March 16, 1935, stipulating that two pesos should be equal to one US dollar regardless of the content of gold. This was the first official introduction of the dollar exchange standard that had come to be the de facto standard of the Islands in the 1920s (Castillo 1949b, 429; Nagano 2010, 45). The currency system of the Philippine Islands “could be considered as representative of the evolving export economy of the Philippines under American rule” (Nagano 2010, 47). Quirino’s proposal was influenced by vested interests during the 1930s.

In addition to the US authority, Quezon publicly declined the idea of establishing an autonomous currency system when he accepted the nomination for presidency at the election for the commonwealth government. On July 20, 1935, he declared, “I shall keep our present currency system in all its integrity and will allow no changes that will affect its value. . . . For the present I can see no reasons for any radical modifications in our monetary system” (Tribune, July 21, 1935, 3rd ed., 1, 14). However, although Quezon did not share the idea of seeking currency autonomy with Singson or Quirino, he did not persuade policy makers to abandon it altogether, as we will see below.

II Stalwart Advocacy for Autonomy in Economic Policy-making, 1935–44

II-1 Early Work of the National Economic Council, 1935–37

The PEA succeeded in persuading the then newly elected President Quezon to organize a central agency for economic planning, although it had failed to convince him to create an autonomous currency system. President Quezon sent a message to the National Assembly on December 18, 1935, to endorse a bill to create the National Economic Council (NEC), which would be responsible for giving occasional advice to the president on economic affairs as well as for proposing comprehensive economic planning. In the message, Quezon mentioned a certain limitation to the idea of laissez-faire and emphasized the significance of the active role of the government in economic affairs (Soberano 1961, 185). The government created Commonwealth Act No. 2 stipulating the establishment of the NEC, presided over by the secretary of finance (NEC 1937; Soberano 1961, 182, 192). The establishment of the NEC and economic planning were the proposals of Singson, Quirino, and the PEA (PEA 1934, 213).

By the time the NEC began its operations on February 14, 1936, Antonio de las Alas had replaced Quirino as the secretary of finance and chair of the NEC. Quirino was appointed as secretary of the interior. Quezon initially preferred Roxas as finance secretary, but he finally chose de las Alas after Roxas declined the offer (Romero 2008, 119). De las Alas, born in Batangas in 1889, graduated from the University of Indiana and Yale University as a pensionado, worked for the Executive Bureau, became a lawyer, and was elected as a representative from Batangas (Cornejo 1939, 1586). Before he was appointed as secretary of finance, he was the secretary of public works and communication (ibid.). De las Alas was close to Quezon but was not as ambitious as Quirino or Roxas. He seemed to be more an able administrator than an aggressive politician.

In the first report of its activity in 1936, the NEC explained the reasons for the inactivity of the council in an apologetic tone, rather than proclaiming its achievements (NEC 1937). After mentioning the lack of data, funding, personnel, and so on, the NEC concluded, “The main reason [sic], however, why no complete economic program could be formulated at present are the uncertainty of our economic relations with the United States and the limitations placed upon the powers of the commonwealth government by the Tydings-McDuffie Law” (ibid., 31). The uncertainty came from the ongoing trade conference, while the limitations pointed to the fact that the commonwealth government could not enjoy any autonomy on tariff issues or currency (ibid.). Former Governor-General Francis B. Harrison, who was appointed as an adviser to Quezon, reported to the United States that the NEC “was ‘paralyzed’ because all of the energies of the government ‘are now bent towards getting a relaxation of the trade sanctions of the Tydings-McDuffie Act’” and that another government attempt to promote diversification of the economic structure was opposed by the “influence of the sugar interests and their lobby in Washington” (Golay 1997, 358).

The NEC report is intriguing, because it reveals that Filipino policy makers made continuous efforts to establish an autonomous currency system and a central bank even under considerable constraints. The first report on the activities in 1936 said, “the peso, under the present system, must follow the dollar for good or for ill, and the Philippines is helpless to influence the American currency policy” (NEC 1937, 33). The NEC advocated that “The Commonwealth should work for an independent currency system, and if granted, the gold bullion standard should be set up to take the place of the present system. . . . With the establishment of a Central Bank as the necessary accompaniment of an independent currency system, the management of the currency to suit the needs of the Commonwealth and an independent Philippines could be easily accomplished” (ibid.). It is easy to spot the influence of Singson’s 1934 proposal on this recommendation. Singson was, in fact, a member of the NEC (Tribune, July 2, 1937, 1).

Gradually the idea of an autonomous currency system found sympathizers in the legislature. Assemblymen Benito Soliven and Juan L. Luna, for instance, submitted Bill No. 2444 “to establish an independent currency system in the Philippines” (Luna and Soliven 1937). Luna, born in Mindoro in 1894, graduated from the University of Santo Tomas and was a teacher and a lawyer before he became a member of the legislature in the 1920s (Cornejo 1939, 1903). Soliven, born in Ilocos Sur in 1898, graduated from the University of the Philippines and became a lawyer and a member of the legislature in the 1920s (ibid., 2151). These two representatives, however, did not seem to have close relations with Singson or Quirino, although Soliven was from Ilocos Sur, where Singson and Quirino had also been born. In fact, Soliven would contest and defeat Quirino in the election to the National Assembly in 1938 (Espinosa-Robles 1990, 46).

In the explanatory note of Bill No. 2444, the authors argued that the currency issue was “a grave problem” untouched during the trade conference (Luna and Soliven 1937, 1). They asserted that the devaluation of the US dollar in 1934 was harmful to the Philippine economy, because the Philippine government would now pay more for its debt to other countries. They also asserted that the Philippine Islands needed to establish an independent currency system based on the gold bullion standard (ibid.). Generally speaking, however, the NEC’s direct input is barely visible in this bill. In fact, in the explanatory note the authors just briefly mention the name of Professor Jacinto Kamantigue, who was a founding member of the PEA when he was still affiliated with the Bureau of Internal Revenue.

The fact that there seemed to be no clear cooperation between these lawmakers and the NEC reflected President Quezon’s conviction about the currency system. In a memorandum by Jones, Quezon was recorded as having told Secretary de las Alas in April 1937, “Please inform the National Economic Council of my fixed purpose not to recommend or approve during my administration measures establishing a new currency system. The present system will be maintained in its integrity because, after consulting expert advice, I am convinced that it is best for the country” (Excerpt from the Quarterly Report of the High Commissioner, 1937, JWJ, 1).

Quezon reiterated his position to maintain the status quo of the currency system. What follows is a record from a press conference dated October 6, 1937:

Press: How about the currency, Mr. President?

President: The currency? That is tabooed. [sic] That is definitely settled; there is no more talk about that. (Press Conference, 1937, MLQ, 20)

Quezon’s brief reply elicits two interpretations: first, the currency issue had already been settled before the press conference. Second, the currency issue was literally tabooed by someone, although that was struck out with a line. It is highly possible that the US authorities restricted Quezon from taking a radical position on this matter.

Jones, now the financial adviser to the American high commissioner, criticized Bill No. 2444 in his memorandum to Washington (Jones to Coy, 1937, JWJ). Jones first stated that the authors of the bill did not understand the existing situation that prompted the Philippine government to adopt the dollar exchange standard (ibid., 1). He reported that there had been no serious problems after the devaluation of the US dollar in 1934 and that it was confusing that the authors condemned the US devaluation but asserted the necessity of peso devaluation (ibid., 1–2). The following concluding sentences of the memorandum clearly express Jones’ strong conviction about the existing monetary system and his unsympathetic attitude toward Filipinos who were seeking autonomy:

First, because if any currencies survive in this world of uncertainty we can feel that the dollar and the pound sterling will be included; and second, the economy of the exchange standard and the fact that Philippine foreign trade is so heavily over-balanced by trade with the United States that we can feel that now and for a number of years to come the Commonwealth and the independent Philippines can do more things with a dollar and do them more economically than they can with an actual gold peso. (ibid., 4)

The outcome was that Bill No. 2444 failed to receive enough support from Filipinos and Americans.

Facing strong opposition from the authorities, the NEC shifted the focus of its advocacy from making the currency system autonomous to creating a central bank. The NEC’s second report, a summary of its activities in 1937 during which the council had only two meetings (NEC 1938, 6), can be read as a record of its desperate efforts to win support for its ideas. In the report it reiterated that it was an internationally accepted idea to have a central bank (ibid., 7, 9–10). The report stated:

Since the war, under the leadership of the League of Nations, countries that have availed of expert financial advice of the League have established a central bank as one of the principal agencies in effecting the reconstruction of their disorganized economic life. Today, most countries find the central bank an indispensable part of their economic system, and even countries that are not yet independent, like the Dominions, India, and Java, have already established a central bank. (ibid., 7)

Another point that makes the second report important is the cue taken from it in order to figure out key advocates. The NEC mentioned, “Vicente Singson-Encarnacion, a member of the Council, has already framed with the aid of our technical staff the proposed charter for a central bank in the Philippines” (ibid., 11). Since we already know that Singson had been active in the advocacy, it is more interesting to find out whom the NEC meant by “our technical staff.” We can easily assume who the technical staff was, because the NEC report reiterates that the NEC had very few technical staff (NEC 1937; 1938). The first report said that Jose L. Celeste was the executive secretary, Castillo the technical adviser, and Juan S. Agcaoili the technical assistant (NEC 1937, 14). The second report said that after Celeste’s resignation in December 1936, Castillo was appointed as acting executive secretary of the council (NEC 1938, 1). Two of the three technical staff, Celeste and Castillo, were original PEA members.

II-2 Joint Preparatory Committee and Manuel A. Roxas, 1936–39

While Singson and others fought in the NEC, Roxas, who would be a significant advocate for the formation of the Central Bank in the late 1930s, fought for the expansion of economic autonomy in the trade conference. On April 14, 1937, the Joint Preparatory Committee on Philippine Affairs (JPCPA) was finally formed “to study trade relations between the United States and the Philippines and to recommend a program for the adjustment of the Philippine national economy” (JPCPA 1938, 3). Roxas joined the committee, which was headed by Jose Yulo, Quezon’s close aide and an important representative of the sugar industry (Larkin 2001, 169). The activity of the JPCPA revealed the clear difference between the positions of those who wished to maintain the status quo and those who sought a structural economic change.

Roxas was as keen about economic issues as Quirino and organized a movement named Ang Bagong Katipunan (the New Katipunan) to advocate economic adjustment for independence in 1930, although he soon abandoned the movement—partly because of Quezon’s indifference (Golay 1997, 292–293). Castillo praised Ang Bagong Katipunan as “The first serious attempt to apply economic principle [sic] on a national scale” when he explained the development of economics in the Philippines (Castillo 1934, 15). Roxas, born in Capiz in 1892, graduated from the University of the Philippines and became a lawyer and a representative in the Lower House. He belonged to the same generation as Quirino but had soared to the third-highest rank in colonial politics next to Quezon and Osmeña in 1922 when he was elected speaker of the Lower House. Quezon appointed him as a member of the JPCPA because of his knowledge and experience. Another member of the JPCPA, the then Majority Floor Leader of the National Assembly Jose Romero, tagged Roxas as “our leading economist” (Romero 2008, 134).

Roxas made his thoughts open to the public in a newspaper contribution before he joined the JPCPA, which was published under the title Philippine Independence May Succeed without Free Trade in the same year (Roxas 1936; Tribune, April 1, 1936, Sec. 4, 1, 2, 4). What he wrote about was close to the ideas of Singson and Quirino, although he did not mention reform in the currency or banking system. He argued, “Knowing that we cannot be certain of the continuance of free trade after independence, the logical course for us to take is to reduce as much as possible the relative importance in the national economy of the industries depending for their existence on free trade with America” (Roxas 1936, 14).

Roxas’ voice, however, failed to gain the support of the majority in the JPCPA. After surveying the process of the JPCPA, a historian succinctly summed it up thus: “It is clear that American economic policy toward the Philippines during the transition to independence was designated to increase American exports and curb Philippine imports. It was a classic example of economic imperialism” (MacIsaac 1993, 345). Echoing the US neglect of the Filipino plea, the JPCPA final report said:

Commercial banking facilities appear to be adequate in Manila and in the larger cities. . . . In view of the present structure of the Philippine banking and currency systems, there appears to be no necessity at the present time for the establishment of a bank in the Philippines whose functions would be primarily those of a central bank. (JPCPA 1938, 122–123)

This conclusion, however, did not reflect the position of Roxas, who would soon be appointed as the new chairman of the NEC as well as the secretary of finance.

II-3 Continuing Attempts to Establish a Central Bank, 1939–44

Roxas did not abandon his idea of changing the economic structure of the Philippine Islands after he was appointed as chairman of the NEC in August 1938, and subsequently secretary of finance on December 1, 1938. On January 4, 1939, he held a meeting with local bankers together with the NEC staff to discuss banking sector reform (Tribune, January 5, 1938, 1, 15). He did not invite anybody from foreign banks, because he expected that economic readjustments should be carried out in cooperation with local rather than foreign banks (ibid., 15). The local bankers Roxas invited included PNB President Vicente Carmona, Bank Commissioner Pedro de Jesus, BPI President Campos, and Philippine Bank of Commerce (PBC) President Cuaderno (ibid.). The PNB and BPI were the two biggest local banks, while the PBC was newly established in 1938.

Roxas’ plan, revealed on January 6, 1938, proposed overhauling the role of the PNB (Tribune, January 7, 1939, 1, 15). Roxas suggested that the government establish a commercial bank, convert the PNB into an investment bank, and “set up a reserve and discount department in the Philippine National Bank which will perform the same functions as those of the federal reserve system” (ibid.). It is impressive that Roxas did not refer to a specific name such as “central bank,” and that he did not advocate the establishment of an independent bank but proposed the setting up of a new department within the existing PNB.

His phraseology, however, did not reflect a retreat of the advocacy to establish a central bank. As a member of the JPCPA, he must have been familiar with the strong opposition from the United States, with whom Filipino policy makers had to negotiate to pass any act regarding currency issues under the Tydings-McDuffie Act. Roxas seemed to have chosen the least controversial way to propose a central bank under the circumstances. What he expected from the department was, however, an enhancement of the banking system and a reduction of interest rates, which were some of the roles Filipino policy makers had expected the central bank to play.

Later on, the bill to establish the Reserve Bank of the Philippines was completed. This time the bill was passed by the Philippine Assembly, signed by President Quezon, and became Commonwealth Act No. 458, “an act to provide for the establishment of a Reserve Bank in the Philippines,” on June 9, 1939 (Bureau of Banking 1940, 21). The Reserve Bank, whose design was taken from those of the newly established Bank of Canada and New Zealand (Cuaderno 1949, 4), would function as a central bank in the Philippines. The commonwealth government could not, however, implement the act immediately because it had to be approved by the American president. Again, Jones opposed the Filipinos’ attempts to establish a central bank (Jones to High Commissioner 1939, JWJ). He argued in a memorandum that Commonwealth Act No. 458 was against the general policy of the Office of the High Commissioner, which had been supported by President Quezon and recommended by the JPCPA as well (ibid., 1).

In the rest of his memorandum, Jones recorded the development of this move and mentioned Cuaderno’s name. Jones wrote that he had been told by A. D. Calhoun, manager of the Manila branch of the National City Bank of New York, that Secretary Roxas had pushed the Assembly to pass the bill despite Speaker Yulo’s skepticism. Jones also reported that “Mr. Mike Cuaderno of the Bank of the Commonwealth was the moving spirit behind the agitation. Mike is the more or less discredited former Vice-President of the Philippine Bank of Commerce [sic]” (ibid., 6). Jones’ hostility toward Cuaderno was obvious. After briefly mentioning the initiative without any comments on Roxas’ personality, he emphasized the role of Cuaderno, who was from one of “the small banks of the street owned by Filipinos,” and the uselessness—or even adverse effect—of Commonwealth Act No. 458 on the financial system (ibid.).

Cuaderno was, however, an established figure as a lawyer-banker in the 1930s. In addition to his job as the deputy manager of the PNB and his participation in the PEA, he was an elected delegate to the Constitutional Convention in 1934 and became a member of the Committee of Seven, which drafted the constitution (Cuaderno 1937). At the convention, he again advocated the establishment of a central bank in the committee report, as the chair of the Committee on Currency and Banking (House of Representatives 1965, 52), although he could not convince other delegates to put the clause into the constitution. After resigning from the PNB in 1936, he became the head of the Finance Mining and Brokerage Company, which was designed as an investment business in the mining industry but was foreseen to become a bank providing financial support to other industries (Tribune, September 6, 1936, 13). Influenced by his work experience in Hong Kong, he nurtured a vision to promote manufacturing, rather than commerce, in his country.17)

In 1938 he established the PBC, the first private bank with Philippine capital (Reyes-McMurray 1998). The PBC was small in terms of quantum of business, but it played a significant role because it provided Filipino practitioners the opportunity to manage a bank, unlike most of the big banks, which were controlled by foreigners and did not provide Filipino workers with enough opportunities for banking experience. President Cuaderno of the PBC would become the first governor of the Central Bank. The first vice president of the PBC, Alfonso Calalang, became the third governor of the bank (ibid., 93).18) Sixto L. Orosa, one of the founding members of the PBC and a prominent banker in the postwar period, later recalled that the PBC was “the Alma Mater of Bankers” (Orosa 1988, 35–36). Jones’ aforementioned quote, however, failed to cite any of Cuaderno’s achievements and rather worked to discredit him.

In addition to Roxas and Cuaderno, Celeste, a founding member of the PEA as well as the first executive secretary of the NEC, took action to support the bill. There was a report on the history of the creation of the Central Bank written by a Japanese officer of the Southern Development Bank (Nampo Kaihatsu Kinko) in 1943 (Awano 1943). The book was, according to the postscript, based on A Reserve Bank of the Philippines written by a Dr. Celeste in 1940 (ibid., 44). It would not be misleading to assume that the author, Dr. Celeste, was Jose Celeste, considering his involvement in the proposal to establish a central bank. According to the author, Celeste mentioned the following four points as reasons to establish a central bank: the currency system’s dependence on the United States, the imperfection of the financial structure, the lack of a credit market, and the lack of investment credit (ibid., 1). The points Celeste mentioned reflected the argument of the previous proposals. The fact that Celeste wrote this document reflected his continuous commitment to the restructuring of the economy.

The act, however, did not receive support from President Quezon and the Assembly. Jones reported the following personal remark by President Quezon on Act No. 458 at a dinner held by the high commissioner. Asked about Act No. 458, Quezon told Jones:

To tell you the truth, Mr. Jones, I did not want to sign the bill. Joe [Speaker Jose Yulo] was not in favor of it particularly. I signed it because I did not wish to indicate any opposition to Roxas. I do not think the Bank will help us any. It is useless unless we have an independent currency. (Jones to High Commissioner, 1939, JWJ, 8)

What this conversation tells us is that Quezon signed the bill only because he did not want to show his opposition to Roxas. Quezon seemingly avoided any unnecessary confrontation with Roxas, who was still a man of influence—especially among politicians, having supported the Os-Rox mission in 1933—and might take over from Quezon in the years to come. Considering the lack of active support from the president, the National Assembly finally adopted a resolution to withdraw Act No. 458 from US government consideration on April 19, 1940 (Bureau of Banking 1941, 29).

Even after the failure of the Roxas plan, policy makers continued to advocate the establishment of a central bank whenever they had a chance. In 1941 Castillo published the first comprehensive textbook of economics in the Philippines, which he dedicated to Filipino students (Castillo 1949a).19) In the chapter on central banking, he summarized the historical development of central banking worldwide and reiterated its necessity in the Philippines (ibid., Ch. 19). In this context, he gave the following brief explanation: “The Reserve Bank of the Philippines would perform the traditional functions of a central bank and make possible the establishment of a banking system which could adequately and efficiently provide the credit needs of business” (ibid., 438). Here we can discern Castillo’s deepest convictions.

During World War II, he continuously advocated the establishment of the bank (Castillo 1943, 84–87). He said that the central bank would be “a responsible guardian of our monetary and credit system” (ibid., 84). He pointed out:

Already prices are rapidly increasing, bringing hardships to consumers and the country has not gotten the right weapons to combat a run-away inflation. . . . With the successive and unregulated issue of notes together with those already in circulation, bringing the total to around 300 million pesos as against about 241.5 million pesos before the war, coupled with economic scarcity, there is little hope that prices could be brought under effective control at present. (ibid., 86)

The Philippine Assembly, in fact, passed a bill to establish the central bank on February 29, 1944 (National Assembly 1943, 132–138; Cuaderno 1949, 4),20) but the bill was not implemented because of the objections of the Japanese, who feared losing the prerogative to issue military notes (Cuaderno 1949, 4). The diary of the Japanese ambassador to the Philippine Republic, Shozo Murata, recorded the last efforts of de las Alas and Castillo, who joined an official mission to Japan in April 1944 and appealed for the implementation of the bill (Fukushima 1969, 45–48). Meanwhile, in the Philippines, Cuaderno as the president of the PBC wrote to de las Alas to open the proposed central bank to curtail inflation in the Philippines (Cuaderno to de las Alas, 1944, MAR). Before the results of their appeals could be declared, the war was over. The agenda to establish a central bank was taken over by the Republic of the Philippines, in which Roxas and Quirino were elected president and vice president respectively while Cuaderno was appointed as the secretary of finance and Castillo became the secretary-economist.

Conclusion

Two policy changes of the US government prompted Filipino policy makers to perceive the existing constraints of policy-making and recognize the necessity to change the system of policy-making in 1933. First, the HHC Act drove Quirino and others to organize the PEA, a network of bureaucrats and professionals who shared common interests in economics, to study the economic consequences of political independence themselves. Second, the US government drastically changed its monetary policy to get out of its serious banking recession, and its policy change had certain impacts on the currency value of the Philippine peso. Although American colonial officers assumed the impact on the peso was negligible, Filipino policy makers regarded it as a crucial sign of the absence of autonomy.

Ideas that were irrelevant to the existing interest structure but emerged internationally encouraged Secretaries of Finance Singson and Quirino to propose the establishment of an autonomous currency system along with a central bank. The ideas were supported not only by Singson, who had been out of the center of political power, but also by Quirino, who had been a close aide of Quezon. They aimed to achieve autonomy in policy-making and to establish a suitable institution necessary for an independent state.

The commonwealth period witnessed continuous endeavors by Filipino policy makers to establish a central bank as well as consistent opposition by American colonial officers. The persistence of the proposal, despite objections and failures, testifies to the fact that the proposal was the creation not of a single individual but of a group of policy makers who were determined to work toward its realization. Roxas took over the proposal from former Secretaries Singson, Quirino, and de las Alas. The proposal grew as an agenda that no finance secretary could afford to avoid and which was worth addressing to attain renown as a new political leader. Professionals such as Castillo and Cuaderno, who scrutinized the issues and channeled the ideas into specific policy proposals, found like-minded partners in the Finance Department.

When we consider the development of the political process, we cannot overestimate the role the US government played in establishing the Central Bank of the Philippines after independence. It was true that Cuaderno collaborated with some American specialists when they pondered on a suitable design for a central bank in the Philippines. It was also true that Cuaderno and Roxas had to prevail over opposition from other Americans. History from the 1930s suggests that Filipino policy makers established the bank in spite of, but with help from, some Americans. Looking at the broader picture, the policy makers appeared to be beneficiaries of colonial state building but were never satisfied with the colonial status of the Philippines.

These findings lead to a reconsideration of our understanding of Philippine politics. First, the policy makers emerged from a changing political context rather than from the existing interest structure. Second, they took advantage of internationally accepted policy ideas to which American colonial officers paid little attention. Third, they were products of the US colonial state and yet at the same time promoters of Filipino nationalism to change the colonial structure. This study has thus revealed that the development of the colonial state spawned a group of policy makers who went beyond the realm of colonial administration. In sum, the setting up of the Central Bank was indispensable to the process of state building by Filipino policy makers.

Accepted: October 10, 2012

Acknowledgments

The writer appreciates comments on earlier drafts at the seminar on “Population Problems and Development Policy in the Philippines” organized by Associate Professor Suzuki Nobutaka (Tsukuba University), supported by the Center for Southeast Asian Studies (Kyoto University), at Kyoto University on March 27, 2012; and at the round table discussion at the Third World Studies Center (University of the Philippines) on May 24, 2012. He is also grateful for comments on an earlier draft by Professor Yamamoto Nobuto (Keio University) and anonymous reviewers. The opinions and errors herein are, of course, his own.

References

Official Documents

Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP). 2003. Money & Banking in the Philippines. Manila: BSP.

―. 1998. 50 years of Central Banking in the Philippines. Manila: BSP.

Bureau of Banking. Various years. Annual Report of the Bank Commissioner of the Philippine Islands. Manila: Bureau of Printing.

House of Representatives. 1965. Constitutional Convention Record, Vol. 11: Committee Reports. Manila: Bureau of Printing.

Joint Philippine American Finance Commission (JPAFC). 1947. Report and Recommendations of the Joint Philippine-American Finance Commission. Washington: US Government Printing Office.

Joint Preparatory Committee on Philippine Affairs (JPCPA). 1938. Report of May 20, 1938, Vol. 1. Washington: US Government Printing Office.

Luna, Juan L.; and Soliven, Benito. 1937. Bill No. 2444: Explanatory Note. In Jones to Coy. 1937. “Memorandum for Mr. Coy, Subject, National Assembly Bill. No. 2444, Nov. 4, 1937,” Folder “Currency, 1933–1937,” Box No. 5, J. Weldon Jones Papers, Harry S. Truman Library, United States.

National Assembly. 1943. Act No. 60: An Act Creating the Central Bank of the Philippines. In National Assembly Year Book, edited by anonymous, pp. 132–138. Manila: No publisher.

National Economic Council (NEC). Various years. Annual Report. Box No. 29 “National Economic Council, 1936–1948,” Series No. 4 “General Miscellany.” Manual A. Roxas Papers, Main Library, University of the Philippines.

Private Papers

J. Weldon Jones Papers (JWJ), Harry S. Truman Library, United States.

“Excerpt from Quarterly Report of H. C. For Quarter Ended September 30, 1937,” Folder “Currency, 1933–1937,” Box No. 5.

Jones to Coy. 1937. “Memorandum for Mr. Coy, Subject, National Assembly Bill. No. 2444, Nov. 4, 1937,” Folder “Currency, 1933–1937,” Box No. 5.

Jones to High Commissioner. 1939. “Memorandum for the High Commissioner, Subject Commonwealth Act No. 458, Nov. 27, 1939,” Folder “Currency Reserve,” Box No. 5.

Quirino to Governor-General. 1935. “Memorandum for His Excellency, the Governor-General: Subject: Independent Philippine Currency System. January 13, 1935,” Folder “Currency, 1933–1937,” Box No. 5.

Singson-Encarnacion to Governor-General. 1933. “Memorandum for His Excellency, the Governor-General, Subject: Amendment to the Provisions of Section 1611 of the Administrative Code, July 6, 1933,” Folder “Currency, 1933–1937,” Box No. 5.

Manual A. Roxas Papers (MAR), Main Library, University of the Philippines.

Cuaderno to de las Alas. 1944, “Memorandum for Minister Alas, June 23, 1944,” Folder “Central Bank of the Philippines, 1944–1948,” Box No. 7 “Cabinet—Central, 1938–1948,” Series No. 4 “General Miscellany.”

Manuel L. Quezon Papers (MLQ), National Library, Republic of the Philippines.

Press Conference. 1937, “Press Conference at Malacañan, October 6, 1937,” Box No. 15, Series No. 3.

Other Sources

Abinales, Patricio N. 2005. Progressive-Machine Conflict in Early-Twentieth-Century U.S. Politics and Colonial-State Building in the Philippines. In The American Colonial State in the Philippines: Global Perspectives, edited by Julian Go and Anne L. Foster, pp. 148–181. Pasig: Anvil Publishing.

Abinales, Patricio N.; and Amoroso, Donna J. 2005. State and Society in the Philippines. Lahman: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Agoncillo, Teodoro A.; and Alfonso, Oscar M. 1961. A Short History of the Filipino People. Quezon City: University of the Philippines.

Anderson, Benedict R. O’G. 1988. Cacique Democracy in the Philippines: Origins and Dreams. New Left Review 169 (May–June): 3–31.

Aruego, Jose M. 1937. The Framing of the Philippine Constitution, Vol. 2. Manila: University Publishing.

Awano Gen粟野 原. 1943. Senzen Hito ni okeru Chuo Ginko Setsuritsu Mondai 戦前比島に於ける中央銀行設立問題 [The issue of the establishment of the central bank in the Philippines before the war]. Tokyo: Research Division, Southern Development Bank.