Contents>> Vol. 1, No. 1

State Recognition or State Appropriation?

Land Rights and Land Disputes among the Bugkalot/Ilongot of Northern Luzon, Philippines

Shu-Yuan Yang*

*楊淑媛, Institute of Ethnology, Academia Sinica, Nankang, Taipei 11529, Taiwan

e-mail: syyang[at]gate.sinica.edu.tw

DOI: doi.org/10.20495/seas.1.1_77

The Bugkalot/Ilongot were awarded the Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title (CADT) issued by the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples in a joyful celebration on February 24, 2006. The CADT is a contemporary assertion of indigenous peoples’ ability to negotiate claims to land, livelihood, and autonomy within the nation-state. So far, however, the acquisition of the Bugkalot/Ilongot CADT has not made any substantial difference in the everyday lives of the people of Ġingin, a settlement located at the heartland of the Bugkalot area. Not only does the trend of in-migration of lowland settlers and other indigenous groups continue, there are heightening social tensions caused by growing numbers of land-grabbing incidents among the Bugkalot themselves. This issue is examined in the context of state-promoted settlement projects, the advance of capitalism, and the process of commodification, which have given rise to a new notion of exclusive landownership. State provision of land rights and capitalist market forces have combined to shape land relations in new and often surprising ways. By exposing some of the diverse and changing forms of dispossession, as well as the failure of barangay officials and government agencies in mediating and resolving land disputes, this article questions whether the seemingly novel avenues that the Philippine state has taken to “legitimate” indigenous peoples’ rights, in practice, actually extend state control.

Keywords: Bugkalot/Ilongot, ancestral domain, land titling, land dispute, capitalism, dispossession

Several scholars have pointed out that the Philippines shows a positively progressive attitude toward indigenous peoples. It is one of the leading countries when it comes to legislations regarding indigenous peoples (Eder and McKenna 2004; Persoon et al. 2004). In 1987 the Philippine Constitution recognized indigenous peoples’ rights to their ancestral territories and their rights to live in accordance with their own traditions, religions, and customs. How these rights are legally defined, and the procedures whereby indigenous communities can secure a Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title (CADT) as evidence of communal ownership of ancestral lands, are detailed in the Indigenous People’s Rights Act (IPRA or Republic Act 8371) of 1997 (Malayang 2001; Hirtz 2003; Eder and McKenna 2004). Hailed as a landmark piece of legislation (Rovillos and Morales 2002, 11), the IPRA is a rejection of the long-standing assimilationist policy of the Philippine state as part of its colonial legacy (Bennagen 2007, 182).

In 1998, less than a year after the passage of the IPRA, a petition before the Philippine Supreme Court was filed challenging the constitutionality of the IPRA and its ancestral domain ownership provisions as a violation of the Regalian Doctrine embodied in the Philippine Constitution. The Regalian Doctrine, a concept dating back to the days of the Spanish monarchy that still underpins the Philippines’ legal system of landownership, declares that the state owns all public lands and natural resources.1) From the point of view of the Regalian Doctrine, most indigenous occupants are squatters on public lands, since any land not covered by official documentation is considered part of the public domain and owned by the state (Prill-Brett 1994; Lynch and Talbott 1995). The proposition that the IPRA and the Regalian Doctrine are incompatible was dismissed by the Supreme Court on December 6, 2000.2) The court upheld the constitutionality of the IPRA and explicitly recognized indigenous peoples’ ownership of their ancestral lands (Bennagen and Royo 2000, 37; Crisologo-Mendoza and Prill-Brett 2009, 44).

Although the IPRA is praised as “a comprehensive law on indigenous peoples’ rights unprecedented in the modern legal history of Southeast Asia” (Wenk 2007, 138), its constraints and limitations have become evident more than a decade after it came into effect. Critical assessments of the IPRA and the Philippine state’s approach to “restorative justice” (Padilla 2008, 451) have revealed four main problems connected with the mapping and titling of ancestral domains. First, the IPRA is anthropologically naïve (Gatmaytan 2007, 21). It is based on simplistic, even romantic, assumptions about indigenous peoples. Indigenous communities are presented as economically self-sufficient and thus free of debt relations that force them to use land as collateral. They are thought to have a collective interest in preserving their cultures and traditions, as though they are not fascinated by mainstream lifestyles and willing to sell their land to purchase goods such as karaoke machines and refrigerators. The law also assumes bounded, homogenous communities on likewise bounded territories. This is an error that has been addressed in the anthropological literature (McDermott 2000; 2001; Van den Top and Persoon 2000; Duhaylungsod 2001; Gatmaytan 2005; McKay 2005a; Gray 2009; Wenk forthcoming) but which still pervades policy-making in the Philippines.

Second, although the IPRA is also known as the Ancestral Domain Law, which recognizes the communal rights of indigenous peoples to their ancestral lands in a way that goes beyond all prior efforts, there are competing claims and conflicting state mandates to land and natural resources. Section 56 of the IPRA subjects the indigenous peoples’ property rights to other existing rights. Moreover, the category “ancestral domain” is glaringly absent on the list of official land-use categories because these categories were determined long before the enactment of the IPRA, and no amendment has yet been made to rectify this omission (Wenk forthcoming). As a consequence, the state retains its prerogative to use and exploit ancestral domains for mining or logging.

Third, the implementation of the IPRA has been slow and ineffective (Eder and McKenna 2004; Gatmaytan 2007; Padilla 2008). The National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP), the implementing agency stipulated in the law, has meager resources at its disposition. The constitutional insecurity of the IPRA mentioned above has been further exacerbated by the curtailing of the NCIP’s budget to such a degree that the commission is rendered toothless, deprived of the means to exercise its mandate (Hirtz 2003, 902). Despite the NCIP’s being under the Office of the President, lack of government funding hampers the implementation of the NCIP’s programs, particularly the ancestral domain titling line. Also, the NCIP has acquired a reputation as a dumping ground for politicians’ protégés who cash in on their patrons’ political debts by seeking government positions. Thus, the impression at the indigenous grassroots is that NCIP officers continue the government tradition of doing nothing while waiting for their salaries and allowances (Padilla 2008, 468).

Finally, the mapping and titling of ancestral domains can serve as a vehicle for intensifying state control and territorial administrations over upland communities. As Li (2002, 274) points out, delineation produces the requisite lists, maps, census data, and agreements for pinning indigenous peoples in place and enmeshing them more firmly as state clients. The legal homogenization or standardization of the notion of, and rights to, ancestral lands also facilitates the exercise of state power (Gatmaytan 2005). Thus, the IPRA has an essential ambiguity or paradox: it can be read as an instrument for asserting indigenous self-determination or for the extension of state control and sovereignty over natural and human resources (Bennagen 2007).

To understand the relevance of the IPRA to indigenous peoples today and whether it has made any substantial difference in their lives, it is necessary to grasp the complexity and dynamics that attend the day-to-day practice of social life in local settings (Gatmaytan 2007, 24). This article is a response to the IPRA’s foremost critic, Augusto Gatmaytan, and his call for the importance of shifting away from a perspective dominated by the state, with its hegemonic categories and rules on land and resources, to looking into how specific actors in specific settings exercise their agency in pursuit of their respective rights or interests. The Bugkalot, or Ilongot as they are known in the previous anthropological literature, will provide the ethnographic context for dis cussion.

The State and Indigeneity on the Frontier

The Bugkalot live at the headwaters of the Cagayan River in Northern Luzon, the area where the Sierra Madre mountain range meets the Caraballo Sur. Since the sixteenth century, the name Ilongot has been used in the colonial and ethnographic literatures to designate this Austronesian-speaking people (Fernandez and de Juan 1969, 84–85). The group has also been known by various other names: “Italon” by the Gaddang, “Ibilao” by the Isinai, and “Abaca” derived from the mountain river system where they were encountered (R. Rosaldo 2003 [1978]; Worcester 1906).3) These names all entered documentary records, and only at the beginning of US colonial rule was the official classification of Ilongot instituted. However, the group call themselves and their language Bugkalot.

The endonym Bugkalot did not enter the ethnographic literature before the time of Michelle Rosaldo and Renato Rosaldo’s fieldwork.4) This reflects the historical fact that this group was never subjugated by the Spaniards or, for the majority of the group, the Americans. The Bugkalot have fiercely resisted incorporation into colonial states for several centuries. The agents of colonization have been various and diverse: ranging from the first military expeditions to the days of the mission outposts, from the American Bureau of Non-Christian Tribes to the present government of the Philippines. Until a few decades ago, the upland the Bugkalot occupied was a typical non-state space in Scott’s definition: the population was sparsely settled, practiced slash-and-burn or shifting cultivation, maintained a mixed economy (including, for example, a reliance on forest products), and was highly mobile, thereby severely limiting the possibilities for reliable state appropriation (Scott 1995, 24–25; 1998, 186–187; 2009, 13). The sociocultural characteristics of the Bugkalot, such as headhunting, lack of formal structure, bilateral kinship, and strong egalitarianism (R. Rosaldo and M. Rosaldo 1972; M. Rosaldo 1980; R. Rosaldo 1980), have contributed to the maintenance of the group’s political autonomy. Human agency plays a significant role in creating and sustaining non-state spaces (Scott 2009). The Bugkalot have not merely taken advantage of their geographical remoteness and isolation from centers of state power; they have purposefully resisted the projects of nation building and state making.

An important dimension of state making is the homogenization, rationalization, and partitioning of space (Alonso 1994, 382). This involves what Scott (1998) calls state simplification. The process of state simplification refers to the strategy of the state to turn a complex, varying, and diverse social hieroglyph into a legible and administratively more convenient format through categorization and standardization. For the state, the natural world, including the actual social patterns of human interaction with nature, is “bureaucratically indigestible” in its raw form. Simplified approximations of the reality, therefore, are indispensable for the state.

State simplification is evident in the state’s ideology and management of the frontier, and its relationship with indigenous peoples or ethnic minorities (Uson 2005). Gathering information about peoples and territories, taxation, registration, and land classification are the very means by which states have traditionally expanded power into areas not yet under politico-administrative control. In the process of internal territorialization, states divide their territories into complex and overlapping political and economic zones, rearranging people and resources within these units, and create regulations delineating how and by whom these areas can be used (Vandergeest and Peluso 1995, 387). An effec tive strategy for territorializing the frontier is sending settlers out to these regions to assert and consolidate state control (De Koninck 1996; Duncan 2004). The Philippines is no exception. The trend of settlers’ large-scale migration into the Bugkalot area began in the late 1950s, and the original impetus for migration was state-organized resettlement projects.

The imperative of the state to bureaucratize space influences the state’s approach to the demands of indigenous peoples, and its consequent construction of indigenous tenure (Gatmaytan 2005, 79). The complexity and variance of indigenous peoples’ customary tenure and resource management practices are reduced to a fixed construction of communal ownership to facilitate manipulation and administration.5) Although the IPRA is an attempt by the Philippine state to come to terms with indigenous peoples’ rights within the framework of the nation-state, it also sets up the procedures for the investigation and documentation of largely unregulated frontier areas that are still, up until today, contested. In order to apply for their CADT, indigenous peoples have to produce the requisite lists, survey plans, maps, census data, agreements, and endorsements in the delineation process. By accepting the state as guarantor of their rights to land, indigenous peoples subscribe to the state’s disputed claim of ownership of the lands they inhabit as part of the so-called public domain (Wenk forthcoming).6)

The construction of indigeneity as the permanent, collective attachment of a group of people to a fixed area of land in a way that marks them as culturally distinct is often evoked by lawmakers, scholars, and activists seeking to expose and contest the devastating threat to indigenous peoples’ livelihoods posed by capitalism. However, the purpose of preventing dispossession may not be served by legislations based on state simplification. Moreover, in some countries the introduction of frameworks that rest on traditionalist assumptions of the centrality of territorial connection have been seen as effectively having a dispossessory effect (Merlan 1998; 2009; Povinelli 2002; Sylvain 2002). Thus, whether the titling of ancestral lands gives the Bugkalot greater land security must be examined in real-life settings.

The Bugkalot/Ilongot and Their Ancestral Domain

Although the name Ilongot is widely used in documentary records and by other groups, many Bugkalot resent the term for its pejorative connotations. The word Ilongot is a Tagalog version of iġ ongott (from the forest), which some Bugkalot along the Baler coast also use to refer to themselves, and connotes wildness and barbarity. Attempts have been made to change the name used in the official classification of indigenous peoples. Now the NCIP mainly calls this group of people Bugkalot. However, on their Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title (CADT), they are referred to as the Bugkalot/Ilongot.

The Bugkalot/Ilongot CADT was approved by the NCIP on July 26, 2003. But due to a lack of administrative efficiency and funding constraints, it was not officially awarded until February 24, 2006 (Figs. 1 and 2). The Bugkalot celebrated the awarding of their CADT with a joyful ceremony that consisted of feasting and dancing in Nagtipunan, Quirino Province, where the current Overall Chiefdom of the Bugkalot Confederation, Rosario K. Comma, also served as the mayor of the municipality.7) Because of the acquisition of their CADT, the Bugkalot are no longer “squatters in the eyes of the law,” as one Ilocano official in the provincial government of Nueva Vizcaya put it.

The CADT is a contemporary assertion of indigenous peoples’ ability to negotiate claims to land, livelihood, and autonomy within the nation-state. It is the result of the fruition and merging of several social and political agendas since the 1980s, namely, issues of environment, indigenous peoples’ struggle for autonomy, and sustainable development. The notion of ancestral domain is predicated on an assumption that land and people are inseparable, and that each group has a definitive place-based identity. However, this idealized picture of boundedness and rootedness is difficult to sustain when there are so many Igorot, Ifugao, and Ilocano settlers in the ancestral domain of the Bugkalot. In several barangays, settlers have outnumbered the Bugkalot and become the majority. When I discussed this issue with my Bugkalot friend who works for the NCIP’s provincial office in Solano, Nueva Vizcaya, his opinion was that “those Igorot and Ifugao should go back to their place in the Cordillera because they also have their own CADT.”

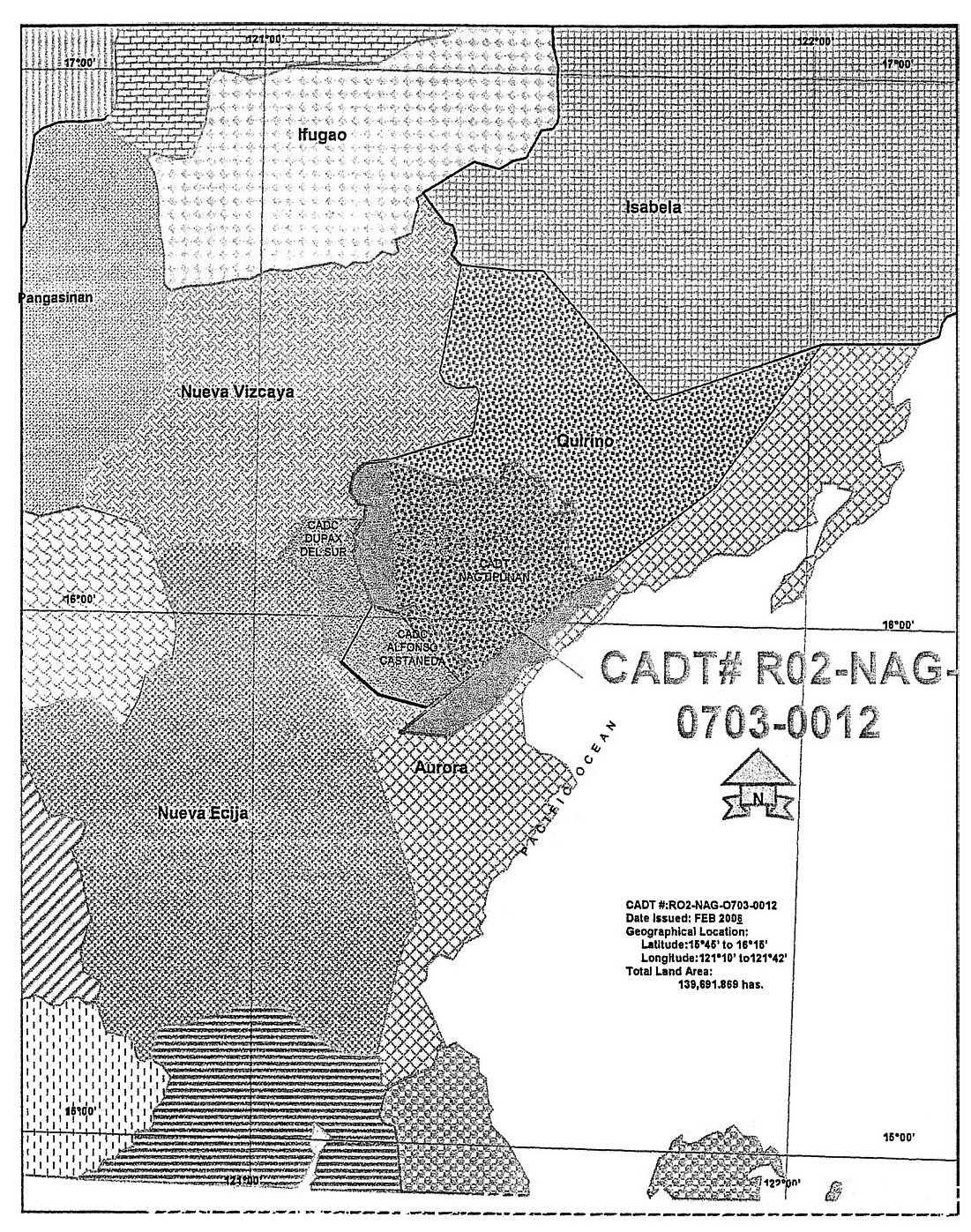

Despite the Bugkalot’s wishes, the settlers have no intention of leaving. In fact, the approved CADT is much smaller than the Bugkalot had hoped for, because of strong opposition from the settlers during the delineation process. The ancestral domain for the Bugkalot covers an area of about 139,691 hectares, located in five municipalities under the jurisdiction of three provinces (Nagtipunan, Quirino; Dipaculao and Maria Aurora, Aurora; Kasibu and Dupax del Norte, Nueva Vizcaya) (Map 1). This CADT area does not correspond to the indigenous notion of Ka-Bugkalotan (the Bugkalot land). According to the Bugkalot Confederation, two municipalities of Nueva Vizcaya Province, Dupax del Sur and Alfonso Castaneda, should also be included in their ancestral domain. Therefore, they are now in the process of petitioning for the granting of a new CADT for these areas, which will be incorporated into the existing Bugkalot CADT when it is approved.8) The exclusion of these two municipalities in the issued Bugkalot CADT is a result of ongoing political struggle and contestation between the Bugkalot and the settlers.9)

Map 1 Location Map of Bugkalot CADT

Source: Bugkalot Ancestral Domain Sustainable Development and Protection Plan, NCIP

It is not surprising that the acquisition of the CADT does not prevent encroachment on Ka-Bugkalotan by new waves of settlers. After all, the intrusion of land-grabbing settlers is a long-standing problem in the area (M. Rosaldo 1980; R. Rosaldo 1980; Salgado 1994; Van den Top and Persoon 2000; Aquino 2003; 2004), and the IPRA largely fails to address this contentious issue. However, land grabbing among the Bugkalot themselves is a fairly recent phenomenon that has never been discussed before. This new phenomenon of “intimate” exclusions from land use involving kin and co-villagers (Hall et al. 2011) is more striking when the Bugkalot are assumed—or appear—to be such a homogenous whole in the CADT. In what follows, I will focus on land disputes among the Bugkalot themselves. I suggest that this issue must be examined in the context of state-promoted settlement projects, the advance of capitalism, and the process of commodifica-tion, which give rise to a new notion of exclusive landownership. The ways in which the Bugkalot understand and explain this issue demonstrate the continuing importance of emotional idioms for the Bugkalot, and we can see in their attempt at resolving land disputes the culturally specific form of social change. The failure of barangay officials and government agencies in mediating and resolving land disputes reflects both the dynamism of Bugkalot culture and the inadequacy of the state in the delivery of service, support, and social well-being to the Bugkalot people.

The Encroachment of Settlers and the Privatization of Land

Traditional Bugkalot subsistence is based on shifting cultivation and hunting, supplemented by some fishing and gathering. Rice is the main crop—and carries important social values—while sweet potato, cassava, manioc, tobacco, bananas, sugar cane, and a variety of vegetables are the major subsidiary crops. The usual sexual division of labor is that men hunt, fish, forage, and clear first-year swiddens, while women do most of the routine gardening. Neither irrigation nor domestic animals are used in cultivation. Unlike shifting cultivators in many parts of the Philippines, the Bugkalot have never entered into symbiotic relations or debt bondage with wet-rice farmers in the nearby lowland (R. Rosaldo and M. Rosaldo 1972; R. Rosaldo 1979).

Land traditionally belongs to those who clear it; it is free and public good (R. Rosaldo and M. Rosaldo 1972, 104). The general principle in claiming land rights among the Bugkalot is to be the first to occupy the land by clearing it through the slash-and-burn method. Before the intrusion of settlers into Bugkalot territory, land was in abundant supply, and the Bugkalot did not recognize among themselves exclusive ownership right to land (M. Rosaldo 1980, 4). As with many shifting cultivators in the Philippine uplands, usufruct is more important than ownership of land (Zialcita 2001). During the period of cultivation, the land and its produce were considered private; but once the land was left fallow, it gradually became communal property again, free for other members of the same beġ tan, the largest unit of social organization or category of affiliation among the Bugkalot, to cultivate.10) As many Bugkalot told me: “In the past it was very easy to get land. If we needed land, we just cut down the forest and made oma (swidden field).” Because population density in their territory was low and wild land was always available, the Bugkalot did not bequeath land. There was no inheritance rule such as primogeniture governing the transmission of land, and the Bugkalot have never developed corporate group tenure regimes like the wet-rice cultivating Igorot and Ifugao (Maceda 1974; Prill-Brett 1993; 1994; McKay 2007; Omura 2008).

This pattern of communal land rights began to change with the coming of land-grabbing settlers. The trend of settlers’ large-scale migration to the Bugkalot area began in the late 1950s. The original impetus for migration was state-supported relocation projects for Ibaloi, Kankanai, and Ifugao peoples directly impacted by the construction of the Ambuklao Dam (1956) and the Binga Dam (1960) in the province of Benguet.11) The well-known bounty of the Sierra Madre and the availability of patches of land in the mountain range were attractive to the people of the Cordillera. Although officially only a few were entitled to be resettled with government support, many of the disenfranchised migrated with the others on their own (Aquino 2004, 177). Because of the encroachment of settlers, the Bugkalot started to lay claims to previously cleared areas and to parcel their common land into individual shares as an attempt to resist these settlers more efficiently (M. Rosaldo 1980, 4; 1991, 157; R. Rosaldo 1980, 277). However, this incipient notion of private landownership did not provide an efficient defense mechanism. In fact, it might even have facilitated the loss of land to subsequent settlers. Because the Bugkalot did not value land or have a clear idea of its worth, they readily gave away tracts of land in exchange for radios, guns, dogs, blankets, salt, sugar, cloth, cooking utensils, etc.

At my field site, Ġingin, a settlement located at the center of the Bugkalot area,12) Igorot, Ifugao, Ilocano, Bicol, and Visayan settlers started to arrive in the 1970s with the logging boom. By this time, most people of Ġingin had already converted to Christianity after more than a decade of evangelism, and headhunting was in serious decline.13) The extraction of timber came from the Nueva Vizcaya side. The logging route originated from the highway town of Bambang, going through Malasin, Dupax, Belancé, Binnuangan, and Giayan before reaching Ġingin. Skilled loggers from as far away as the Bicol region and the Visayas were brought in by the logging companies. Some loggers, road builders, and drivers stayed in Ġingin after their jobs at the logging companies were finished. Several of them courted Bugkalot women, got married, and acquired land from their affines. However, a majority of them, like settlers in other frontier societies in the Philippines (Lopez 1987; Li 2002), tended to regard indigenous land as state land and generally treated it as open access.

The arrival of settlers in Ġingin was soon followed by more state attempts at incorporation. From 1978 to the mid-1980s, the Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR) launched several development projects in Ġingin, including settlement projects, irrigation, and wet-rice cultivation aimed at increasing agricultural productivity in the uplands. These development projects were related to the green revolution in the lowlands, but they were also driven by the government’s persistent desire to involve the Bugkalot in sedentary agriculture in order to make them more controllable. The settlement project was originally intended for Igorot and Ifugao displaced by the construction of the Ambuklao and Binga Dams in the Cordillera. Ġingin was chosen as a settlement site because the government regarded it as state land, basically treating the Bugkalot as squatters. The indigenous residents of Ġingin found the DAR’s project, which aimed at bringing in more settlers, troubling. As one DAR official who lived in Ġingin for eight months at the beginning of the project told me, the Bugkalot were highly suspicious of the settlers, and they were afraid that the settlers would poison the water to kill them all and get their land. Thus, they asked their relatives, who had migrated to Lipuga, Pelaway, and Cawayan during World War II in order to flee from the Japanese soldiers invading the area, to move back to Ġingin as a strategy of defending their territory against the settlers. As Apun Maria succinctly answered when I inquired about the reason for their return: deġ in (land).14) Free housing provided by the DAR was not the most important incentive. The Bugkalot decided to move back to Ġingin because the lands here were “fat” ( oabe, fertile) and beautiful ( okedeng).

In the mid-1980s the DAR left Ġingin in fear of the New People’s Army (NPA), the armed wing of the Communist Party of the Philippines, who burnt the DAR’s office in Belancé in 1986 and terrorized the region. Although it was—and is—not uncommon to see the NPA interacting and forming reciprocal relationships with local people in the remote mountainous areas of the Philippines (Kwiatkowski 2008; Shimizu 2011, 6), the Bugkalot had violent encounters with the NPA and even perceived them as the land grabbers’ helpers (Yang 2011a). After peace and order were restored in the area, the DAR returned in the early 1990s to start land measuring and titling, which was part of the resettlement project. The legal foundation of land titling is provided by the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Law of 1988 (Republic Act No. 6657). Because of financial constraints, the DAR did not have enough staff or resources to measure the whole area of Ġingin, so those who wanted land titles had to take the initiative themselves and apply. Land titles acquired under the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Law of 1988 are different from other schemes based on communal tenures (Brown 1994); they are private properties, which are alienable. Settlers were very keen on obtaining land titles, which they considered a guarantee of their land security. However, at this time the land market was not really formed, and land was not commoditized in Ġingin. Some Bugkalot applied for land titles, but many did not see the usefulness of a piece of paper that carried an obligation to pay taxes to the government, and as a result they did not apply for land titles.15)

In the 1980s, the nearest lowland town—Bambang—became the main trading center of commercial vegetable gardening in the Cagayan Valley (Sajor 1999, 107). However, the cultivation of cash crops did not spread to Ġingin until the turn of this century, due to transportation barriers and the lack of capital. The first person to plant cash crops was an Igorot from Baguio, whose sister married a local Bugkalot man. From 1997 to 2002, he borrowed his brother-in-law’s land in Ganépa, about one hour’s hike from Ġingin proper, to grow string beans, pepper, and tomatoes. At that time, jeepneys did not come to Ġingin—only to Ganépa. Also, the schedule was not regular. Frequently, the man had to use carabao to haul his products to the previous village—Giayan—for transportation to the market. In 1999, a half-Ilocano, half-Igorot man, newly married to a Bugkalot girl, moved to Ġingin and started to plant sweet peas in Manoġatoġ, a sitio (settlement, local cluster) of Ġingin about one hour’s hike from the main settlement. In 2003, Ilocano and Igorot settlers started to plant cash crops in gardens near Ġingin proper. In 2005 and 2006, more Bugkalot joined them to produce cash crops for a volatile market.

The cultivation of cash crops is labor intensive and capital intensive. Labor is not a problem, but getting the capital to start commercial vegetable gardening is a highly challenging task for the people of Ġingin. Few of them, mostly barangay officials, were able to get development funds from the DAR or the Department of Agriculture. The purpose of providing low-interest loans to the Bugkalot, as a DAR official told me, is “to bring them closer to the government.” However, the majority of aspiring commercial gardeners were not beneficiaries of these interest-free loans, and they had to improvise and use kinship and other social ties to obtain seeds, fertilizers, pesticides, and agricultural tools. Some settlers had relatives in the Cordillera or the lowland working abroad and acquired remittance as their capital.16) The Bugkalot, however, had to sell their carabao or pawn ( sangla) their lands or guns to settlers to get a start-up fund. Therefore, the scale of cash crop cultivation was usually small. In their attempts to obtain capital to start commercial vegetable gardening, the people of Ġingin began to use their land titles as collateral to apply for bank loans.

In 2004, an Ilocano settler who married a local Bugkalot woman used one of their land titles to apply successfully for a loan of 30,000 pesos from the Cooperative Bank of Solano. This caused quite a stir in the remote village of Ġingin. Despite the fact that the interest charged by the bank was unreasonably high, many people began asking the man about the process of applying for bank loans. Later in 2004, a young Bugkalot woman who married an Ilocano used her carabao as collateral to get a loan of 10,000 pesos; and with this capital, she was able to open a small grocery store. In 2005 at least 11 Bugkalot were successful in getting bank loans, and the annual interest rates they paid varied from 16 per cent to 20 per cent. In concurrence with this sudden and sharp increase of cash in Bugkalot’s daily lives, land grabbing began to take place among them and caused heightened social tensions in Ġingin.

Land Grabbing among the Bugkalot Themselves

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the traditional pattern of communal land tenure began to change when lowlanders and other indigenous migrants entered Ġingin. The Bugkalot could not hope to hold uncultivated lands against the increasing numbers of settlers, and began to designate particular plots as “private property” that individual owners could decide what to do with. Among the Bugkalot themselves, however, access to land was still fairly easy and was not a concern that led to social conflict. When about half the population moved from Lipuga and Pelaway back to Ġingin in the late 1970s and early 1980s, they obtained land simply by talking to their relatives and choosing a site where they wanted to open oma. Because the returnees had lived in the area before the invasion of Japanese soldiers made them flee in fear, kinship ties and historical connections to the place entitled them to open land ( emmatoġ nima deġ in, pimmeyan ma deġ in) as they saw fit.

Although the Bugkalot started to develop the notion of private ownership of land, land was not yet commoditized. Land borrowing among the Bugkalot was free of charge, and several of the earliest settlers married local women and obtained affinal ties with the Bugkalot. They were obliged to share goods they brought with them from the lowland, as kinship norms dictated, but this was not payment for land. The commoditization of land happened later, at the turn of the century, when the advance of the full-fledged capitalist market economy penetrated Ġingin. As several Igorot who live in the area between Giayan and Ġingin told me, before the late 1990s, new settlers could acquire land through exchange, but now they had to buy land with money. This was also the period during which commercial vegetable gardening spread to the area.

When land became the easiest way to obtain cash, land grabbing among the Bugkalot themselves began to occur. Manoġatoġ, a sitio of Ġingin, is a vast area not far from the main road and with dense forest nearby. In the 1970s, no Bugkalot lived there. When Bugkalot moved back to Ġingin from Lipuga and Pelaway, one Pasigian family settled there in 1982 to open their oma. The siblings and children got married, built their own houses, and opened more oma and later rice paddies; gradually Manoġatoġ grew into a settlement consisting of ten households and its own church. In the mid-1990s, the govern ment started the construction of the Casecnan Dam in Pelaway, Alfonso Castaneda, and many Bugkalot moved to Pelaway and Lipuga in search of employment. The population of Manoġatoġ shrank considerably, dwindling to five households. In 2001, another Pasigian family in Yamu, also a sitio of Ġingin, sold some land in Manoġatoġ to an Igorot settler for 3,000 pesos. In 2004, they sold more land here to another Igorot family for 5,000 pesos and one gun. These were lands in the early stage of fallowing. The owner of these lands, Uncle Topdek, was very unhappy about this. However, he was originally from Landingan, Quirino Province, and had little status in Ġingin, so he kept his complaints to himself.17) In 2005 Topdek’s leg was seriously injured in an accident, and he was hospitalized for a long period. In order to pay Topdek’s medical expenses and to acquire capital for planting cash crops, his son used his land title to obtain a big loan from the bank. The Yamu people took this opportunity to grab more lands from Topdek and his brothers-in-law, Bernardo and Sigmund. They started to use Topdek’s oma, sold his rice paddy to the Igorot, occupied his kamaġ it (field hut), and stole his son-in-law’s agricultural equipment. In 2006, they essentially took over Manoġatoġ and cut down a vast area of forest to make new oma there. In fear of them, Topdek and Bernardo’s families moved to Ġingin proper, and used their land in Kaantagan to plant rice and cash crops.

It is striking that there were close kinship ties between these two Pasigian families. Not only were there consanguineous connections between them, Topdek’s sister-in-law and Bernardo and Sigmund’s sister Alita was married to Samuel, one of the Yamu brothers. To have one’s land grabbed by close relatives hurt the victim’s feelings deeply. As Topdek’s daughter Grace said to me: “They said we are relatives, but I don’t believe them. If they were true relatives ( anewed katan-agi), how could they have done this to us?”

Although there are at least eight other cases of land dispute among the Bugkalot themselves, this is the most serious and controversial one because it violates Bugkalot social norms to the fullest extent. Other cases do not depart as far from the traditional pattern of land use. The most common dispute over land concerns the question of precedence, which is difficult to decide in an originally nonliterate society that depends on eyewitness accounts. Exactly whose ancestors opened the land in a certain area first, entitling their descendants to the right to claim it, is often contested. The problem arises because the Bugkalot did not bequeath land. As Lingling said, “Land was not important before, so the old people didn’t pass it down to anyone before they died.” In these situations, however, the two parties involved can usually talk it over and find a solution or a compromise. Other cases of land dispute evoked bad feelings ( en-oget ma nemnem, en-oget ma ġ inawa) but did not become a social issue. For example, Apun Maria is over 80 years old, and a few years ago she decided that it was time for her to retire from working in her oma. Her son did not use her land and left it to fallow, so the Yamu people took it. Apun Maria is not happy about this, because they did not respect her by asking her for the land first—but since they are relatives, she tolerates the situation. Her son, the barangay kapitan (captain) of La Conwap, also keeps quiet because he needs the Yamu people’s support at election time.18)

Another case is the conflict between Lisa and Dengpag. After Gading-an died, Lisa started to till one of his parcels of land in Yamu without asking his family. The land was steep and stony and was not considered good land, but Lisa liked it because it was close to Ġingin and would save her a lot of time and effort hiking to the oma every morning. She hoped to acquire the land by cultivating it, as the Bugkalot had done before. Nobody objected when she opened her oma there. However, after Lisa had a good harvest, Dengpag told her that Gading-an had given the land to him before his death, and he demanded its return. Lisa gave up this land, but she was bitter that Dengpag did not cultivate it and “left it to grow grass.”

What makes the Bugkalot of Ġingin highly concerned about the Yamu people’s land grabbing is that they completely disregard the morality of kinship and seem to be driven by greed. They grab other Bugkalot’s land in order to sell it to new settlers. To make matters worse, Topdek and Bernardo had already applied for and obtained land titles ( titole) in Manoġatoġ when the DAR came in the early 1990s to survey the land. Their land titles did not provide sufficient protection for their land security. Thus, the general feeling was that nobody could be certain that they would not fall victim to “the number one land grabber in Ġingin.”

Although land grabbing among the Bugkalot must be understood in the context of the expansion of capitalism and the commoditization of land, Bugkalot themselves do not prioritize utilitarian reasons or economic needs in perceiving and explaining land disputes. They consider envy ( apet, apiġ) the most important motivation for land grabbing. Bugkalot have a strong sense of competition and a desire not to be outdone by others (Jones 1907-09, book 10, 7; M. Rosaldo 1980, 18). Therefore, it is said that when Yamu people see others with things they themselves don’t have, such as chainsaws, televisions, and generators, they become envious ( meaapet, en-apiġ), so they grab other people’s land. Similarly, when Yamu people see others getting large loans from the bank with their land titles, while they themselves have no land title, they are envious, so they grab other people’s land. We can also see the continuing significance of emotional idioms in the land dispute between Lisa and Dengpag mentioned above. Dengpag did not object when Lisa opened her oma. However, after he saw that Lisa was able to reap a bumper harvest, he asked her to return the land. He did not cultivate it or sell it but left it fallow, and he was said to be “just envious of Lisa’s good harvest.”19)

Map 2 Barangays within the Bugkalot CADT

Source: Bugkalot Ancestral Domain Sustainable Development and Protection Plan, NCIP

Note: Ġingin is located at a boundary dispute area between Nueva Vizcaya Province and Quirino Province. On the Vizcaya side it is named New Gumiad, while on the Quirino side it is named La Conwap.

Barangay officials have made several attempts to resolve social conflicts over land between the Yamu people and Topdek’s family. Besides acting as go-betweens between the two parties, they have also organized three public meetings ( poġong) attended by the whole community. However, a solution or compromise is yet to be found. In the following section, I will discuss the culturally specific method of dispute resolution among the Bugkalot, and show how different discourses are intertwined in these negotiations. The political implications of the failure of barangay officials and government agencies to resolve land disputes will be addressed as well.

Poġong: Oratory, Persuasion, and Attempt to Resolve Land Dispute

In her refined discussions of Ilongot oratory, poġong ( purung in her spelling), Michelle Rosaldo (1973; 1980; 1991) contrasts its public nature with the more fluid, more direct, and personal nature of everyday talk. The word poġong describes at once a public meeting in which opposing parties come together to discuss and resolve their differences, and an elaborate style of speech, which is rich in art, wit, and indirection. Rosaldo suggests that this “crooked,” curvy, and allusive style of speech is closely linked with indigenous egalitarian norms, and it emerges in a social order based on persuasion rather than compulsion. Traditional oratorical events typically concern either marrying or killing (headhunting), both of which are occasions for “anger” ( liget, energy/anger/passion). Anger is the product of “envy,” and “envy” is created when the ideals of “sameness” and equality are breached (M. Rosaldo 1991, 154). In poġong, adult men use their knowledge and verbal skills to negotiate “anger” and to achieve balance in social relationships. In this individualistic society where each man is his own master, poġong provides a focused context in which it is appropriate to invoke shared norms and public understanding, and to explain obligations and commitments in terms of social ideals.20)

At the time of her fieldwork (1967–69, 1974), Michelle Rosaldo also observed the emergence of a new style of speech among the Ilongot. Modern oratory, represented by the speech of recently Christianized Ilongot, substituted an ideal of simplicity and directness for the complex, evasive style of traditional oratorical speech. Rosaldo argued that the public use of “straight speech” was linked with externally imposed authoritarian relationships, such as the government, the law, and God. The emergence of a modern oratorical style has caused the genre of poġong to lose its appeal among a people who once enjoyed it.

Before the first poġong for a land dispute took place, I had the opportunity to observe another poġong. This poġong was called by the barangay captain of New Gumiad and was held in the barangay hall. The matter for discussion was a fight between two young men, Roland and Rodney. The previous afternoon, a group of young men had been playing basketball. Roland was drunk, got too competitive in the game, and started a fight with Rodney. Rodney was punched in the face and sustained an obvious injury. This was not a serious matter, but the meeting was surprisingly long—about 3.5 hours. Almost every man present wanted to give a speech and advise the young men. They invoked kinship idioms and social norms to “cool down” the youthful heated heads. Even though my ability to understand the Bugkalot language was quite limited at the time, I could tell that the elder men’s speeches were repetitive. Later I discussed this poġong with some young people, and they, like the young men of Rosaldo’s time, showed a similar reaction to poġong. They rejected the speeches of elder Bugkalot men as confusing and foolish: “Old men talk in a funny way. They never express their opinions directly and clearly. So it’s difficult to know exactly what they mean”; “Old men talk slowly, and they like to repeat and repeat. That’s why I am not interested in poġong. It’s a waste of time.”

Uncle Siklab’s style of speech was singled out and mocked by the young generation. In the poġong, Uncle Siklab asked whether Rodney wanted to—as per Bugkalot custom—demand a pig as beyaw (compensation). However, he did not say so directly. Rather, he said that since Rodney had been injured in the face and the wound was painful, did he want Roland to put some oil on his wound to soothe it. However, barangay captain Bobby interrupted him, saying that it was a simple matter and so he did not want to see any animal butchered. The meeting was concluded with a handshake between Roland and Rodney, and no animal blood was shed. It seems that the simplicity of modern ways is favored over burdensome traditions, and the barangay captain is able to derive power from his position.

Fig. 3 Bugkalot Men Waiting for the First Poġong to Start

However, when it came to finding a resolution for the land dispute between the Yamu people and Topdek’s family, the efforts of both barangay captains were to no avail. Ramon, the barangay captain of La Conwap, was closely related to the Pasigian family of Yamu, so he acted as the main go-between. It took him many visits over the course of more than a year to finally persuade the Pasigian family to have a poġong with Topdek’s family. The first poġong took place at Yamu on June 18, 2006 (Fig. 3). It was attended by more than 40 people, most of them men. Barangay captain Ramon, who was also the leading elder in the church, opened the poġong with a prayer. However, the land dispute negotiation did not proceed in the Christian spirit. The Pasigians of Yamu adamantly stated their claim that Manoġatoġ was their place because their ancestors had been the first to open the land there before the Japanese period. They asserted their rights derived from their ancestors’ precedence, even though Apun Maria’s late husband, Tobe Pasigian, was recognized commonly by other members of the community as the first person to have opened the land in Manoġatoġ and he had given his consent to—and had helped—Topdek’s family to cultivate the area in the early 1980s. The Yamu Pasigians did not have even the slightest intention of returning the land. In fact, they also claimed that Kaantagan, the land Topdek’s family was using at that time, was theirs as well. The barangay captains and most councilors ( kagawad) did not support either side, as they were in the middle ( bengġi) trying to mediate and negotiate a compromise. They evoked the authority of the state and the law ( batat) and suggested that since Topdek and Bernardo had land titles the Yamu people should respect that and return the titled lands to them. However, since Manoġatoġ is a vast area, the Yamu people could use those areas not covered by existing land titles.

Barangay officials’ attempts to find a balance between the authority of the state and the Bugkalot notion of precedence failed completely. Timothy, an elder in the church, evoked the Christian ethic when he said to Samuel, one of the Yamu brothers, “Can we bring the land to Heaven? God sees everything we do; He judges our actions.” Samuel saw this as a personal attack and reacted angrily. He used to be an elder in the local church, but recently he had been suspended for land grabbing. He resented being disci-plined and stopped attending the Sunday service.

Different discourses were intertwined in this poġong: the Bugkalot notion of precedence ( sinangat), the legal landownership instituted by the state, and the Christian ethic. Barangay officials placed emphasis on land titles and expected to derive power from the law, but this failed to impress or persuade the Yamu Pasigians. In fact, the latter said bluntly in private that they did not care how thick Topdek and Bernardo’s land titles were; the land was still theirs. The second poġong was held in the barangay hall in September, while I was away. That too failed to reach a middle ground between the two sides involved in the land dispute.

The third poġong took place in the barangay hall on January 7, 2007. Barangay captains Ramon and Bobby opened the meeting stating their sincere wish to solve the problem of the land. Then Tagem, the father of the Yamu brothers, adopted the traditional oratorical style and said that they had talked to each other ( penen opo), which was comparable to opening a path to go to the hunting ground, and he hoped they could have some gains. However, Sigmund replied by asking the reason for their gathering there that day. What was their purpose? He acted as though he was in the dark, but was really questioning the Yamu people’s sincerity in resolving the land dispute. Topdek’s uncle Longilong made it explicit again that that day’s poġong aimed to solve the problem of the land, and since Topdek and Bernardo had land titles, Tagem and his sons should return the land to them. However, Tagem said they were willing to return only Topdek’s land, and that Topdek, Bernardo, and Sigmund could decide how to divide that land among themselves. This was the first time the Yamu Pasigians had made some concession, so Uncle Siklab and the barangay officials encouraged Topdek’s family to accept it; they also proposed determining the boundary so that no more disputes would occur in the future.

Understandably, Topdek’s family did not consider this a fair offer. Bernardo and Sigmund insisted that their in-laws should return all their lands. However, in typical Bugkalot fashion, they emphasized the opposite. They said they could give all the lands in Manoġatoġ to their in-laws, as if Samuel’s family had paid lango (bridewealth) for their sister Alita. This innuendo was intended to shame the Yamu people, because Samuel had violated the rule of uxorilocal postmarital residence when he married Alita, and his family had not paid any lango according to Bugkalot tradition. Bernardo’s formal talk was punctuated with more sarcasm, as he expressed his heartfelt wish for Samuel to return to the church and attend Sunday services. Although women seldom give speeches at a poġong, usually preferring to comment in private, Bernardo’s mother, Apun Lonsa, spoke out on this occasion. She recalled her sadness when Samuel did not come to live in her house while he was courting Alita, taking Alita instead to their house in Yamu. She was further saddened by their land grabbing, and asked Tagem why, if Manoġatoġ was indeed their place, he had raised no objection when her family opened their oma there when they came from Lipuga. Apun Lonsa also brought up another issue: Samuel’s domestic violence toward Alita. Alita had quarreled with Samuel when he grabbed land from her brothers and brother-in-law, but he had silenced her by beating her badly. Samuel defended himself saying he had had good reason to beat Alita, that she had not obeyed her husband as a good wife should always do. Pastor Rene, a Visayan missionary of the New Tribes Mission who was stationed in Giayan, also came that day and tried to mediate. He urged Samuel’s family to return all the land so the Lord would be pleased. His words, too, failed to persuade them.

Another poġong ended in futility. Compared with the first poġong, there was a shift in the rhetoric or discourse. While at the first poġong barangay officials had attempted to derive power or authority from the government and the law, this time the land title was mentioned only briefly by Uncle Longilong at the beginning. The focus of this poġong was kinship idioms and social norms concerning how relatives ( makatan-agi) and affines ( niman naagiagi) should treat each other. Sigmund, Topdek, and Apun Lonsa all expressed their deep sadness and distress. They recalled how close the two families used to be and the mutual conviviality resulting from frequent visits, working together, and joint hunting trips. However, the problem of the land had created a gulf between them, and they no longer visited each other; only their children continued to do so.

The emphasis on kinship idioms did not move the Yamu people to return the land. Although Tagem’s stance seemed to soften, he held that he could not force his sons to change their attitude. The failure of yet another poġong to resolve this land dispute did not come as a surprise to the people of Ġingin. Before the meetings, they had commented on the “bad character” of the Yamu people and questioned the sincerity of their desire to solve the problem. Many referred to them as “very angry people” ( oliliget ta too) or “uncivilized.” These words connote headhunting, a practice the Yamu people have not abjured completely. In spite of the fact that Tagem and all his sons had been zealous churchgoers in the past and some of them had been elected as elders, they had “backslid” and resumed the practice of headhunting.21) I was constantly warned by the Bugkalot never to go to Yamu or anywhere alone.

The threat of violence and the fear of a possible resurgence of tribal warfare are given by the people of Ġingin as some of the reasons why poġong fail to resolve land disputes. There are other reasons why barangay officials are unable to assert authority and curb land grabbing. It has already been mentioned that Ġingin is located at an area of boundary dispute between the provinces of Nueva Vizcaya and Quirino. In 2007, there were 190 registered voters in New Gumiad (the Vizcaya side) and 202 in La Conwap (the Quirino side).22) Barangay elections are often competitive, and the margin of winning or losing is small. For instance, in 2001 Ramon won the election for barangay captain of La Conwap by fewer than 10 votes.23) The Pasigian families of Yamu register on the Quirino side and control more than 40 votes, which means that they are able to swing the result of barangay elections. As a formidable power in local politics, they have more grounds to continue with what Pastor Rene describes as a “the paper is yours, but the land is ours” attitude.

Compared with oratorical events in the past, contemporary poġong is much more “straight,” direct, simple, and short. However, contrary to what Michelle Rosaldo’s discussion of oratorical style and mode of authority would lead us to expect, straight speech does not enable barangay officials to claim authority by identifying with offices assigned to them by the Philippine government. On the one hand, this can be seen as continuity with the past: the Bugkalot are not responsive to authority and uphold the tradition of strong egalitarianism (Jones 1908, 4; M. Rosaldo 1980; Campa 1988 [1891], 76). On the other hand, there is a significant difference that indicates a fundamental change in their social lives. While the Bugkalot traditionally deploy egalitarian norms to minimize conflict among themselves (M. Rosaldo 1980, 187), this nonresponsiveness to authority now makes the successful mediation of land disputes almost impossible. So far, the heightened social tensions caused by land grabbing still “have no place to go.”

The insult and wrong Topdek’s family suffered at the hands of the Yamu people would have led to a headhunting feud in the past. Now, the victims of land grabbing try to find, with increasing difficulty, peace and consolation in their Christian faith. For instance, they interpreted an illness contracted by Tagem’s eldest son, Benjamin, as divine retribution. In the fall of 2005, Benjamin started to develop symptoms of a serious illness, which was diagnosed a year later in hospital as bone cancer. He died a painful death in 2007. However, Tagem did not see Benjamin’s ailment as punishment ( padusa) from God, but thought the witchcraft of the Igorot family to whom he had sold Topdek’s land in Manoġatoġ was to blame. In a state of rage, he fired several gunshots near that Igorot family’s house and threatened to kill them. The Igorot were very frightened, and they planned to move to Ganépa to be near their relatives.

Barangay officials’ lack of authority and their failure in resolving land disputes reflect both the dynamism of Bugkalot culture and the weakness of the Philippine state. Disillusioned by the incapability of barangay officials, Topdek’s family have tried to seek the assistance of other government agencies in this matter. They requested Ramon to plead their case with politicians at the municipal and provincial levels, but they were disappointed. As a result, they withdrew their support for him in the 2007 barangay election and took the matter into their own hands. After the first poġong failed, Bernardo reported the crime of land grabbing to the police in Malasin, but they said such a matter should be dealt with by barangay officials and refused to take any action. This is read as another example of the corruption prevalent in the country: “You know what police are like in the Philippines. They are corrupt. If we don’t bribe them they will not help.” However, Topdek’s family was poor and unable to pay the pisi (police). Bernardo made another attempt to obtain government assistance by petitioning the DAR’s local office in Malasin. The director there showed sympathy and replied that she would arrange a visit to Ġingin with the DAR’s lawyer to explain the law to the Bugkalot so they would “learn how to respect land titles”; but when I left Ġingin in May 2008, this promised visit had not yet come.

Having tried in vain all avenues of resolution they can think of, Topdek’s family now see the NCIP as their last hope. Although most Bugkalot do not have a clear idea of the overall politics of the whole land titling situation, they do know that the IPRA and the CADT are about state provisions of land rights. After the CADT was officially awarded to the Bugkalot on February 24, 2006, the NCIP held barangay-level meetings in the following months to explain to the Bugkalot their rights and responsibilities to ancestral domain, and asked each barangay to form a board of so-called CADT officials. CADT officials and barangay officials often overlap, and they constitute what Section 66 of the IPRA refers to as the Council of Elders/Leaders, which has the authority to settle disputes according to customary laws and practices. If all remedies provided under the customary laws are exhausted and a resolution is yet to be found, then a dispute within the ancestral domain shall be brought to NCIP’s jurisdiction. This is what Topdek’s family hope to do. However, given the financial constraints of the NCIP and its internal ethnic politics, there are considerable grounds for pessimism.24) Therefore, Topdek’s daughter Rachel often exclaims: “We have no law here!”

Land Titling, Capitalism, and Dispossession

A young Bugkalot woman’s exasperation at the absence of law in Ġingin shows that “the actual application of the law is open to a host of contingent factors” (Aguilar 2005, 127). Land security is not a guaranteed outcome of land titling; it is dependent upon local economic and political conditions. Although communal land tenure, designed to prevent piecemeal dispossession, is a built-in feature of the IPRA, the assumption that indigenous peoples are tightly bound communities and are united in their struggle for land does not stand up to scrutiny. Today the Bugkalot face competition for land not only from settlers but also from fellow Bugkalot. Land disputes in Ġingin cannot be seen simply as a result of conflicts between traditional indigenous land tenure and state legislation. Instead, disputes over land have been concomitant with the emergence of the land market when Ġingin was brought into the orbit of capitalism.

The notion of private landownership began to develop in Ġingin with the arrival of land-grabbing settlers in the 1970s. The private, exclusive, and alienable land right gained legality and state recognition through the DAR’s land-titling program in the early 1990s. The coexistence of two types of land tenure systems, one individualized and the other collective, is the historical outcome of capitalist processes and the state’s attempt to manage dispossession. The link between the collective, inalienable land tenure currently associated with indigeneity, as pointed out by Li (2010, 410), should not be taken as a prior state to capitalism on a linear, evolutionary trajectory or as a marker of ineffable otherness. Rather, the two co-emerged.

When Bugkalot started to lay claims to previously cleared areas, and to parcel their common land into individual shares in an attempt to resist the encroachment of settlers, the inadvertent consequence was that it facilitated the dispossessory process. Again, when the Bugkalot began to participate in the production of cash crops and to use their lands as collateral to apply for bank loans, a different form of dispossession took place. Some people failed to repay their bank loans and as a result lost their lands. They were caught up in what Li ( ibid. , 388) calls “mechanisms of dispossession”: the debt was there, the interest the bank charged was too high, the price fetched by their commodities was thus, the cost of inputs exceeded outputs, they could not make ends meet. These dispossessory effects of the capitalist processes emerging “from below” ( ibid., 396) are often overlooked or underestimated by the state.

Because of their desire to obtain pecuniary benefits from capitalist ventures, the Bugkalot are exposed to the risks and opportunities of market participation. The IPRA and the CADT cannot simply erect a wall to protect them by insisting that indigenous peoples’ right to the land is collective and inalienable. In fact, after the Bugkalot were officially awarded their CADT, there was a renewed move to individualize land rights within the Bugkalot ancestral domain. The settlers were acutely aware that their presence in the Bugkalot ancestral domain was problematic and urged the DAR to title more of their lands. The DAR’s local office was dominated by Irogot, Ilocano, and Ifugao settlers, and it swiftly responded. In 2007, the DAR began a new land-titling program in Ġingin that aimed to cover the whole area (Figs. 4 and 5). The DAR asserts that its new land-titling program is fully supported by the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Law of 1988 (Republic Act No. 6657), and that it has higher authority in the Bugkalot CADT area because the government issued an Executive Order (#364) that placed the NCIP under the direct supervision of the DAR in 2004. Placing ancestral domain concerns with the DAR has the drawback of misconstruing communal titles belonging to indigenous communities as properties with a corresponding commercial value (Padilla 2008, 468), but this is exactly what the settlers want.

The IPRA recognizes communal land tenure of indigenous peoples as a legitimate right and creates a favorable legal environment for it to continue. Economic forces, however, appear to be pushing in the opposite direction. A similar tilt toward individual ownership of common resources has been observed in the Cordillera region, the sending communities of settlers. Although wet-rice cultivating groups such as the Bontoc Igorot and the Ifugao have developed traditional corporate group tenurial practices that fit squarely with the IPRA’s assumption of communal land tenure, new livelihood opportunities such as cash crop cultivation and even tourism are motivating individuals to claim personal ownership over resources that have been owned by their clans or by the community (Crisologo-Mendoza and Prill-Brett 2009, 36). State provision of land rights and capitalist market forces have combined to shape land relations in new and often surprising ways.

Fig. 4 Ġingin Residents and a DAR Official Having a Discussion on Land Titling

Fig. 5 A Survey Map of the Land-titling Program

In this article, I have exposed some of the diverse and changing forms of dispossession that took place in Ġingin. It is apparent that the state should attempt to reverse the dispossessory effects of capitalism. However, the failure of barangay officials and government agencies alike in halting land grabbing reflects the inadequacy of the state in the delivery of service, support, order, and social well-being to the Bugkalot people. It also indicates “the apparent continuing unwillingness, or inability, of the state to match words with deeds” (Eder and McKenna 2004, 56) when it comes to indigenous peoples’ legislation. Despite the considerable progress toward greater land security for indigenous peoples established in the 1987 Constitution and subsequent legislative and policy initiatives, promise has not yet become practice. It is a sobering reality that a title is but a piece of paper—itself neither altering existing power asymmetries, nor empowering indigenous peoples, nor protecting their territory against encroachment—and that new challenges begin once a title is legally secured (Wenk forthcoming). Title-holding indigenous groups such as the Bugkalot are in need of sincere state assistance and support, which they do not get at the moment. So far the CADT process has succeeded in making the frontier region legible to the state, but it fails to provide land security promised in the IPRA. Thus, 15 years after the passing of the IPRA, the realities on the ground provide sufficient reasons to wonder whether the seemingly novel avenues that the Philippine state has taken to “legitimize” indigenous peoples’ rights, in practice, merely extend state control.

Acknowledgements

The fieldwork among the Bugkalot on which this article is based was funded by the National Science Council. I thank the Institute of Philippine Culture, Ateneo de Manila University, for assistance during my research. An earlier version of this article has been presented at Workshop on “Indigenous Peoples in Southeast Asia and Pacific Islands: New Laws and Discourses, New Realities?” held at the International Institute for Asian Studies (IIAS), Leiden University. I thank the discussant, Serge Bahuchet, and the participants, especially Cynthia Chou, Levita Duhaylungsod, Gerard Persoon, and Oscar Salemink, for their helpful comments. I am very grateful to Irina Wenk for sending me her forthcoming article, I have benefited greatly from her discussion. I also thank two anonymous reviewers of Southeast Asian Studies for their encouragements and insightful suggestions. My biggest debt is to the people of Ġingin who opened their lives to me.

References

Aguilar, Filomeno V. Jr. 2005. Paradise Lost? Forest Resource Management between the State and Upland Ethnic Groups. In Control and Conflict in the Uplands: Ethnic Communities, Resources, and the State in Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam, edited by Filomeno V. Aguilar Jr. and Ma. Angelina M. Uson, pp. 125–135. Quezon City: Institute of Philippine Culture, Ateneo de Manila University.

Alonso, Ana Maria. 1994. The Politics of Space, Time and Substance: State Formation, Nationalism and Ethnicity. Annual Review of Anthropology 23: 379–405.

Aquino, Dante M. 2004. Resource Management in Ancestral Lands: The Bugkalots in Northeastern Luzon. Leiden: Institute of Environmental Science, Leiden University.

―. 2003. Co-Management of Forest Resources: The Bugkalot Experience. In Co-Management of Natural Resources in Asia: A Comparative Perspective, edited by Gerard A. Persoon, Diny M. E. van Est, and Percy E. Sajise, pp. 113–137. Copenhagen: Nias Press.

Bennagen, Ponciano L. 2007. “Amending” IPRA, Negotiating Autonomy, Upholding the Right to Self-Determination. In Negotiating Autonomy: Case Studies on Philippine Indigenous Peoples’ Land Rights, edited by Augusto B. Gatmaytan, pp. 179–198. Quezon City/Copenhagen: International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs.

Bennagen, Ponciano L.; and Royo, Antoinette G., eds. 2000. Mapping the Earth, Mapping Life. Quezon City: Legal Rights and Natural Resources Center.

Brown, Elaine C. 1994. Grounds at Stake in Ancestral Domains. In Patterns of Power and Politics in the Philippines: Implications for Development, edited by James F. Eder and Robert L. Youngblood, pp. 43–76. Tampa: Arizona State University.

Campa, Buenaventura, O. P. 1988 [1891]. An Exploration Trip to the Ilongots and the Negritos in 1891. Translated by Fr. Pablo Fernandez, O. P. UST Journal of Graduate Research 17(2): 67–82.

Crisologo-Mendoza, Lorelei; and Prill-Brett, June. 2009. Communal Land Management in the Cordillera Region of the Philippines. In Land and Cultural Survival: The Communal Land Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Asia, edited by Jayantha Perera, pp. 35–61. Mandaluyong City: Asian Development Bank.

De Koninck, Roldolphe. 1996. The Peasants as the Territorial Spearhead of the State in Southeast Asia: The Case of Vietnam. Sojourn 11(2): 231–258.

Duhaylungsod, Levita. 2001. Rethinking Sustainable Development: Indigenous Peoples and Resource Use Relations in the Philippines. Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 157(3): 609–628.

Duncan, Christopher R. 2004. Legislating Modernity among the Marginalized. In Civilizing the Margins: Southeast Asian Government Policies for the Development of Minorities, edited by Christopher R. Duncan, pp. 2–23. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Eder, James F.; and McKenna, Thomas M. 2004. Minorities in the Philippines. In Civilizing the Margins: Southeast Asian Government Policies for the Development of Minorities, edited by Christopher R. Duncan, pp. 56–85. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Fernandez, P., O. P.; and de Juan, J. O. P. 1969. Social and Economic Development of the Province of Nueva Vizcaya, Philippines. Acta Manilana Series B 1(8): 56–134.

Gatmaytan, Augusto B. 2007. Philippine Indigenous Peoples and the Quest for Autonomy: Negotiated or Compromised? In Negotiating Autonomy: Case Studies on Philippine Indigenous Peoples’ Land Rights, edited by Augusto B. Gatmaytan, pp. 1–36. Quezon City/Copenhagen: International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs.

―. 2005. Constitutions in Conflict: Manobo Tenure as Critique of Law. In Control and Conflict in the Uplands: Ethnic Communities, Resources, and the State in Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam, edited by Filomeno V. Aguilar Jr. and Ma. Angelina M. Uson, pp. 63–96. Quezon City: Institute of Philippine Culture, Ateneo de Manila University.

Gray, Andrew. 2009. Indigenous Peoples and Their Territories. In Decolonising Indigenous Rights, edited by Adolfo de Oliveira, pp. 17–44. London: Routledge.

Hall, Derek; Hirsch, Philip; and Li, Tania Murray. 2011. Powers of Exclusion: Land Dilemmas in Southeast Asia. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Hirtz, Frank. 2003. It Takes Modern Means to Be Traditional: On Recognizing Indigenous Cultural Communities in the Philippines. Development and Change 34(5): 887–914.

Jones, William. 1908. Copy of Letter from William Jones to Franz Boas dated August 25, 1908. Chicago: Field Museum.

―. 1907–09. Diary. Chicago: Field Museum.

Keesing, Felix M. 1962. The Ethnohistory of Northern Luzon. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Kwiatkowski, Lynn. 2008. Fear and Empathy in Revolutionary Conflict: Views of NPA Soldiers among Ifugao Civilians. In Brokering a Revolution: Cadres in a Philippine Insurgency, edited by Rosanne Rutten, pp. 233–279. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

Li, Tania Murray. 2010. Indigeneity, Capitalism, and the Management of Dispossession. Current Anthropology 51(3): 385–414.

―. 2002. Engaging Simplifications: Community-Based Resource Management, Market Processes and State Agendas in Upland Southeast Asia. World Developmentt 30(2): 265–283.

Lopez, Maria Elena. 1987. The Politics of Lands at Risk in a Philippine Frontier. In Lands at Risk in the Third World: Local Level Perspectives, edited by Peter D. Little, Michael M. Horowitz, and A. Endre Nyerges, pp. 213–229. Boulder: Westview Press.

Lynch, Owen J.; and Talbott, Kirk. 1995. Balancing Acts: Community-Based Forest Management and National Law in Asia and the Pacific. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute.

Maceda, Marcelino N. 1974. A Survey of Landed Property Concepts and Practices among the Marginal Agriculturalists of the Philippines. Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society 2(1–2): 5–20.

Malayang, Ben S. III. 2001. Tenure Rights and Ancestral Domains in the Philippines: A Study of the Roots of Conflict. Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land-en Volkenkunde 157(3): 661–676.

McDermott, Melanie Hughes. 2001. Invoking Community: Indigenous People and Ancestral Domain in Palawan, the Philippines. In Communities and the Environment: Ethnicity, Gender, and the State in Community-Based Conservation, edited by Arun Agrawal and Clark C. Gibson, pp. 32–62. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

―. 2000. Boundaries and Pathways: Indigenous Identity, Ancestral Domain, and Forest Use in Palawan, the Philippines. PhD dissertation, University of California, Berkeley.

McKay, Deirdre. 2007. Locality, Place, and Globalization on the Cordillera: Building on the Work of June Prill-Brett. In Cordillera in June: Essays Celebrating June Prill-Brett, Anthropologist, edited by Ben P. Tapang, pp. 147–167. Diliman, Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

―. 2005a. Rethinking Locality in Ifugao: Tribes, Domains, and Colonial Histories. Philippine Studies 53(4): 459–490.

―. 2005b. Reading Remittance Landscapes: Female Migration and Agricultural Transition in the Philippines. Danish Journal of Geography 105(1) 89–99.

―. 2003. Cultivating New Local Futures: Remittance Economies and Land-use Patterns in Ifugao, Philippines. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 34(2): 285–306.

Merlan, Francesca. 2009. Indigeneity: Global and Local. Current Anthropology 50(3): 303–333.

―. 1998. Caging the Rainbow: Places, Politics, and Aborigines in a North Australian Town. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Omura, Makiko. 2008. Traditional Institutions and Sustainable Livelihood: Evidence from Upland Agricultural Communities in the Philippines. In Economics of Poverty, Environment and Natural Resource Use, edited by Rob B. Delink and Arjan Ruijs, pp. 141–156. New York: Springer.

Osingat, Lasin P. 2007. Effectiveness of the Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title (CADT) as Tenure Instrument of the Bugkalot Tribe in Nueva Vizcaya. MS thesis in rural development. Nueva Vizcaya State University.

Padilla, Sabino G. Jr. 2008. Indigenous Peoples, Settlers and the Philippine Ancestral Domain Land Titling Program. In Frontier Encounters: Indigenous Communities and Settlers in Asia and Latin America, edited by Danilo Geiger, pp. 449–481. Copenhagen: International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs.

Persoon, Gerard A.; Minter, Tessa; Slee, Barbara; and van der Hammen, Clara. 2004. The Position of Indigenous Peoples in the Management of Tropical Forests. Wageninger, Netherlands: Tropenbos International.

Povinelli, Elizabeth A. 2002. The Cunning of Recognition: Indigenous Alterities and the Making of Australian Multiculturalism. Durham: Duke University Press.

Prill-Brett, June. 1994. Indigenous Land Rights and Legal Pluralism among Philippine Highlanders. Law and Society Review 28(3): 687–697.

―. 1993. Common Property Regimes and the Bontoc of the Northern Philippine Highlands and State Policies. Cordillera Studies Center Working Paper 21. Baguio City: Cordillera Studies Center, University of the Philippines Baguio College.

Rosaldo, Michelle Z. 1991. Words That Are Moving: Social Meanings of Ilongot Verbal Art. In Dangerous Words: Language and Politics in the Pacific, edited by Donald Brenneis and Fred R. Myers, pp. 131–160. New York: New York University Press.

―. 1980. Knowledge and Passion: Ilongot Notions of Self and Social Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

―. 1973. I Have Nothing to Hide: The Language of Ilongot Oratory. Language in Society 2(2): 193–223.

Rosaldo, Renato. 2003 [1978]. Viewed from the Valleys: Five Names for Ilongots, 1645–1969. Saint Mary’s University Research Journal 5: 101–112.

―. 1980. Ilongot Headhunting 1883–1974: A Study in Society and History. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

―. 1979. The Social Relations of Ilongot Subsistence. In Contributions to the Study of Philippine Shifting Cultivation, edited by Harold Olofson, pp. 29–41. Laguna, Philippines: Forest Research Institute.

―. 1975. Where Precision Lies: The Hill People Once Lived on a Hill. In The Interpretation of Symbolism, edited by Roy Willis, pp. 1–22. London: Malaby Press.

Rosaldo, Renato; and Rosaldo, Michelle Z. 1972. Ilongot. In Ethnic Groups of Insular Southeast Asia, Vol. 2: Philippines and Formosa, edited by Frank M. LeBar, pp. 103–106. New Haven: Human Relations Area Files Press.

Rovillos, Raymundo D.; and Morales, Daisy N. 2002. Indigenous Peoples/Ethnic Minorities and Poverty Reduction, Philippines. Mandaluyong City: Asian Development Bank.

Sajor, Edsel E. 1999. Upland Livelihood Transformation: State and Market of Social Processes and Social Autonomy in the Northern Philippines. The Hague: Institute of Social Studies.

Salgado, Pedro V., O. P. 1994. The Ilongots: 1591–1994. Sampaloc, Manila: Lucky Press Inc.

Scott, James. 2009. The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia. New Haven: Yale University Press.

―. 1998. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven: Yale University Press.

―. 1995. State Simplifications: Some Applications in Southeast Asia. Wertheim Lecture Series. Amsterdam: Centre for Asian Studies.

Shimizu, Hiromu. 2011. Grassroots Globalization of an Ifugao Village, Northern Philippines. Newsletter, Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University 62: 4–6.

Sylvain, Renée. 2002. “Land, Water, and Truth”: San Identity and Global Indigenism. American Anthropologists 104(4): 1074–1085.

Uson, Ma. Angelina M. 2005. Upland Ethnic Minorities, Resource Conflicts, and State Simplification. In Control and Conflict in the Uplands: Ethnic Communities, Resources, and the State in Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam, edited by Filomeno V. Aguilar Jr. and Ma. Angelina M. Uson, pp. 1–22. Quezon City: Institute of Philippine Culture, Ateneo de Manila University.

Van den Top, Gerhard; and Persoon, Gerard. 2000. Dissolving State Responsibilities for Forests in Northern Luzon. In Old Ties and New Solidarities: Studies on Philippine Communities, edited by Charles McDonald and Guillermo Pesigan, pp. 158–176. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

Vandergeest, Peter; and Peluso, Nancy Lee. 1995. Territorialization and State Power in Thailand. Theory and Society 24(3): 385–426.

Wenk, Irina. Forthcoming. Land Titling in Perspective: Indigenous-Settler Relations and Territorialization on a Southern Philippine Frontier. In Colonization and Conflict: A Comparative Study of Contemporary Settlement Frontiers in South and Southeast Asia, edited by Daniel Geiger. Munster: LIT.