Indonesian Technocracy in Transition: A Preliminary Analysis*

Shiraishi Takashi**

*I would like to thank Caroline Sy Hau for her insightful comments and suggestions for this article.

**白石 隆, Institute of Developing Economies Japan External Trade Organization (IDE-JETRO), 3-2-2 Wakaba, Mihamaku, Chiba, Chiba Prefecture 261-8545, Japan; National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies (GRIPS), 7-22-1 Roppongi, Minato-ku, Tokyo 106-8677, Japan

e-mail: takasisiraisi[at]gmail.com

DOI: doi.org/10.20495/seas.3.2_255

Indonesia underwent enormous political and institutional changes in the wake of the 1997–98 economic crisis and the collapse of Soeharto’s authoritarian regime. Yet something curious happened under President Yudhoyono: a politics of economic growth has returned in post-crisis decentralized, democratic Indonesia. The politics of economic growth is politics that transforms political issues of redistribution into problems of output and attempts to neutralize social conflict in favor of a consensus on growth. Under Soeharto, this politics provided ideological legitimation to his authoritarian regime. The new politics of economic growth in post-Soeharto Indonesia works differently. Decentralized democracy created a new set of conditions for doing politics: social divisions along ethnic and religious lines are no longer suppressed but are contained locally. A new institutional framework was also created for the economic policy-making. The 1999 Central Bank Law guarantees the independence of the Bank Indonesia (BI) from the government. The Law on State Finance requires the government to keep the annual budget deficit below 3% of the GDP while also expanding the powers of the Ministry of Finance (MOF) at the expense of National Development Planning Agency. No longer insulated in a state of political demobilization as under Soeharto, Indonesian technocracy depends for its performance on who runs these institutions and the complex political processes that inform their decisions and operations.

Keywords: Indonesia, technocrats, technocracy, decentralization, democratization, central bank, Ministry of Finance, National Development Planning Agency

At a time when Indonesia is seen as a success story, with its economy growing at 5.9% on average in the post-global financial crisis years of 2009 to 2012 and performing better than its neighbor economies of Malaysia (with its economic growth of 4.1% a year in 2009–12), the Philippines (4.8%), and Thailand (3.0%), it is easy to forget that less than a decade ago many people wondered and worried whether Indonesia would turn into a Yugoslavia, in danger of breaking up owing to ethnic and religious tensions, or a Pakistan, subject to periodic military intervention and the rising jihadist threat, or a Philippines, democratic but with insurgencies simmering in the provinces and a weak and stagnant economy.

Nothing of this sort has happened. Instead, and most remarkably, a politics of economic growth has returned, but under conditions that are different from the politics of economic development pursued by Soeharto under the New Order.

The politics of economic growth is politics that transforms political issues of redistribution into problems of output and attempts to neutralize social conflict in favor of a consensus on growth, thus creating a “virtuous” cycle of political stability which leads to economic development which leads to the rising living standard which in turn leads to further political stability. Under Soeharto, this politics provided the ideological legitimation to his authoritarian state, while also delivering on its promise to improve the living standards of a substantial majority of the Indonesian people, helping to create a sizeable Indonesian middle class. In this context, technocrats emerged as major allies of Soeharto, working closely with the President on all economic policy issues.

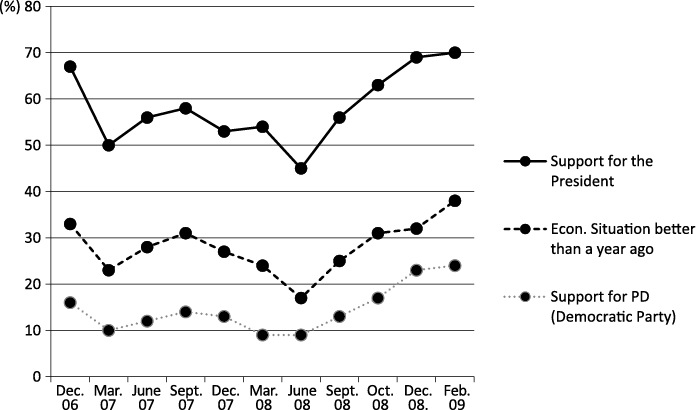

The new politics of economic growth works differently under the current decentralized democracy, and technocrats also now work under conditions different from Soeharto’s New Order. The salience of this politics of economic growth was underscored in the reelection of Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono in 2009 as President. Public support for the incumbent President and his Democratic Party nicely correlated with public perception of Indonesia’s economic performance. Thanks in part to the global financial crisis that pushed down fuel prices, for which the President took credit, Yudhoyono was reelected overwhelmingly in the first round voting with technocrat Budiono as his running mate. The resurgence of the politics of economic growth in Indonesia and with it the comeback of technocrats as a force (though as vulnerable as the technocrats in Soeharto’s time, but in a different way) in Indonesian politics can be seen in the prestige and authority that former Minister of Finance Sri Mulyani Indrawati enjoys even after she was sent off to the International Monetary Fund.

What made technocrats effective as economic policy-makers under Soeharto? What conditions have enabled technocrats to be effective under the current democratic system? Who are they in the first place? The answers to these questions illuminate the important but nevertheless fraught position occupied by technocrats in Indonesia’s changing political structure and processes of economic policy-making.

The Making of Indonesian Technocracy

Technocracy in Indonesia emerged and developed in the 1960s and 1970s in tandem with the rise and consolidation of Soeharto’s authoritarian developmental state. Soeharto fashioned his New Order regime with the state as his power base and the army as its backbone. The regime was centralized, militarized, and authoritarian. Army officers dominated the military and occupied strategic positions in the civilian arm of the state as district chiefs, provincial governors, directors-general, and ministers in the name of dual functions. State power was repeatedly impressed upon regime “enemies”—“communists,” “separatists” in East Timor, Aceh, and Papua (Irian Jaya), criminals, labor activists, journalists, and Islamists. The government contained the question of social divisions along ethnic and religious lines through state repression (politics of stability, that is) while it addressed the question of class divisions through its politics of economic development. The government thus achieved the state of political demobilization (as opposed high level of political mobilization under Sukarno’s Guided Democracy) deemed necessary to national development by barring oppositional groups (whether ethnic, religious, or political) from participation in the political processes and imposed its politics of stability and development on the public.

Technocrats, who were in charge of development, thrived in the state of political demobilization under the New Order. They started their technocratic career in the early days of the New Order as Soeharto’s economic advisers. They were young academics trained as economists at Indonesia’s premier university, the University of Indonesia (hereinafter UI), and abroad who maintained their academic status as UI professors while joining the government as technocrats. Five of them emerged as key members of Soeharto’s economic team and founding fathers of the Indonesian technocracy: Widjojo Nitisastro, Ali Wardhana, Emil Salim, Subroto, and Mohammad Sadli.

In the early years of the New Order, there were not very many Indonesians who had the technical expertise to formulate and manage economic policies and to communicate in the language of economics with their counterparts from other countries such as the United States and Japan and from international agencies such as the International Monetary Fund (hereinafter IMF), the World Bank (hereinafter WB), and the Asian Development Bank (hereinafter ADB). The first-generation of technocrats obtained the expertise and the language thanks to their training at foreign, largely American, universities. Their small number and close personal relationships with each other (as well as their expertise) set them apart from the great majority of civilian bureaucrats and military officers who ran the New Order state. While they could have a significant impact on broad economic policies, above all monetary policies and major allocations of government resources, they had relatively little influence on or control over the political and bureaucratic processes that enabled the policy implementation of contracts, licenses, promotions, payoffs, and other micro-economic details (Bresnan 1993, 73).

Technocrats enjoyed Soeharto’s trust and confidence as his ally and were appointed as ministers in charge of key economic agencies: Widjojo Nitisastro as Chairman of BAPPENAS (Badan Perencanaan Pembangunan Nasional) (1967–83), Coordinating Minister for Economy, Finance and Industry (hereinafter Menko, 1973–83), and presidential economic advisor (1993–98);1) Ali Wardhana as Minister of Finance (1973–83) and Menko (1983–88);2) Emil Salim as State Minister for State Apparatus (1971–73), Minister of Transportation, Communication and Tourism (1973–78), State Minister for Development Supervision and Environment (1978–83), and State Minister for Population and Environment (1983–93);3) Subroto as Minister of Manpower, Resettlement and Cooperatives (1978–83) and Minister of Mining and Energy (1983–88);4) Mohammad Sadli as Minister of Manpower (1971–73) and Minister of Mining and Energy (1973–78).5) They were soon followed by their juniors: J. B. Sumarlin who served as State Minister for State Apparatus (1973–83), State Minister for National Development Planning and BAPPENAS Chairman (1983–88), and Minister of Finance (1988–93);6) Saleh Afif who served as State Minister for State Apparatus and Deputy Chairman of BAPPENAS (1983–88), State Minister for National Development Planning and Chairman of BAPPENAS (1988–93) and Menko (1993–98);7) Adrianus Mooy as BI (Bank Indonesia) Governor (1988–93);8) Rachmat Saleh as BI Governor (1973–83) and Trade Minister (1983–88);9) Arifin Siregar as BI Governor (1983–88) and Trade Minister (1988–93);10) Soedradjad Djiwandono as BI Governor (1993–98).11)

As their careers show, four of the first-generation technocrats studied at the University of California, Berkeley, and three of them obtained their Ph.Ds there, hence the group appellation “Berkeley Mafia.” But a more appropriate label for the technocrats under Soeharto should have been the “UI-Gadjah Mada Mafia” because many of the technocrats who followed their footsteps were either trained at the UI or Gadjah Mada University, which would serve as the nesting grounds for grooming the technocrats who succeeded the original five.

In the early years of the New Order, technocrats were instrumental in setting the principles that informed the macro-economic policy framework under Soeharto: the balanced budget, the open capital account, and the pegged exchange rate system. The balanced budget principle and its international institutional framework, IGGI/CGI, served as a mechanism to keep total public expenditures under domestic government revenues plus official capital inflows.12) It was instrumental in keeping the government from resorting to deficit financing and served to shield the Minister of Finance from excessive financing demands (Ginandjar and Stern forthcoming, 13–14). It also functioned to prevent the government from attempting to raise funds by issuing domestic government bonds (and indeed, the government did not issue domestic bonds until the 1997 crisis). But it was never made into a law. It essentially depended on the ability of the Finance Minister to persuade the President to reject proposals that required excess expenditure. The government also relied on off-budget expenditures, the size of which was often unknown even to senior policy-makers. Over time, the government increasingly resorted to off-budget accounts to fund numerous pet projects (such as the state aircraft industry and Krakatau Steel), finance government election campaigns, and underwrite persistent public enterprise sector deficits by borrowing from state banks (ibid.).

The second principle—the open capital account—was introduced in 1971, when the government eliminated controls on foreign exchange transactions, most notably capital flows. The open capital account was meant to provide a further brake on monetary policy by ensuring that any monetary mismanagement would show up almost immediately in an outflow of foreign exchange. And finally, an adjustable pegged exchange rate (the third principle) was meant to maintain the real international value of the rupiah by adjusting the nominal rate to reflect changes in domestic consumer prices relative to the international prices of its major trading partners (ibid.).

Technocrats, enjoying Soeharto’s trust and armed with the three principles, proved effective in the economic policy-making as long as the president supported them. They formulated broad economic policies collectively. A good example is monetary policy. Under the New Order, the BI was not independent. Central Bank Law No. 13, 1968 (Law of the Republic of Indonesia Number 13 of 1968 concerning the Central Bank) explicitly stated that BI implement monetary policy formulated by the Monetary Board. The board was composed of the Finance Minister, Minister of Trade and Industry, State Secretary, government Economic Advisers (Widjojo Nitisastro and Ali Wardhana, that is), and the Governor of BI. Policy recommendations and decisions as well as their implementation were in due course reported and discussed with the President. Decisions were generally made after going through him. Sometimes decisions were made for immediate implementation. Otherwise, they went through Cabinet meetings, which were conducted once a month (Djiwandono 2004, 46).

But the above technocrats only represented one school of thought on Indonesia’s economic development. They adhered to the doctrine of free trade and advocated limiting state intervention in the market to a minimum and guaranteeing as much as possible the free economic activities of the private sector. They also hewed to the notion of “comparative advantage” of a country for economic development. Another school of thought—mainly represented by engineers, many of whom were trained at the Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB)—believed in industrial policy and upheld state-led economic nationalism, arguing that the state should actively intervene to promote long-term growth of domestic industries, if necessary shielding these domestic industries from outside competition.

Officials representing these two opposing camps sought Soeharto’s support and blessings. Indonesia’s development strategies oscillated between the two schools of thought as Soeharto oscillated between the two strategies. When the economy was booming, economic nationalism manifested itself in the form of large-scale capital-intensive state projects, which often turned out to be wasteful and served to increase Indonesia’s external debt. When the economy experienced a downturn, those projects were shelved, the exchange rate was devalued, and deregulations were introduced to integrate the Indonesian economy more deeply into the global market.

BAPPENAS was the stronghold of technocrats with the physical presence, either formal or informal, of Widjojo Nitisastro, while the nationalist school was represented by such high-ranking officials as B. J. Habibie, who served as State Minister for Science and Technology and Chief of Technology Assessment and Application Agency (Badan Pengkajian dan Penerapan Teknologi, BPPT) from 1983 to 1998; Ginandjar Kartasasmita who served as Junior Minister for the Promotion of Domestic Products (1983–88), Head of the Investment Coordinating Board (Badan Koordinasi Penanaman Modal, BKPM) (1985–88), Minister of Mining and Energy (1988–93), and State Minister for National Development Planning and Chief of BAPPENAS (1993–98); Hartarto, Minister of Industry (1988–93); and Tunky Ariwibowo, Minister of Industry (1993–95) and Minister of Industry and Trade (1995–97). Rent-seekers with vested interests, above all presidential cronies and, increasingly, Soeharto’s family members, openly allied themselves with the nationalist school.

Technocrats had their heyday in the mid- to late 1980s. One contentious issue between technocrats and nationalists was import controls. In 1982, an “approved traders” system was introduced. The system established a list of categories of raw materials, components, and products that could be imported only by specified agencies. By early 1986, 1,484 items were under import license controls and 296 items were under physical import quotas. These items amounted to USD2.7 billion worth of imports in 1985, representing more than half the value of Indonesia’s total imports. These controls did little to protect local industries, and functioned more as a means of generating income for the president’s family and friends (Bresnan 1993, 247, 249). Another issue was controls on private investment. Foreign investment was tightly controlled; from 1974 onward, the Investment Coordinating Board (BKPM) issued comprehensive guidelines every year listing the priority areas for investment. Under the leadership of Ginandjar Kartasasmita, the 1985 investment priority list, for instance, included 400 projects which were open to foreign investors, others which were restricted to domestic investors, and areas that were closed to investment altogether (ibid., 251).

But oil revenues were declining because of the collapse of oil prices in the early 1980s. The Fourth Five-Year Plan, announced in 1984, made it clear that the days of state-funded projects were over. The Plan estimated that the economy would have to create nine million new jobs over the five-year period; this in turn would require the investment of Rp145.2 trillion, but the government budget would only be able to provide around half of that amount. The remainder, Rp67.5 trillion, would have to come from the private sector and state enterprises. Both the Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces Gen. Benny Murdani and the State Secretary and Chairman of the government’s party, Golongan Karya (Golkar) Lt. Gen. Suhdarmono—Soeharto’s two top lieutenants in those days—called on ethnic Chinese businessmen to support the Plan by calling for the end of racial discrimination in government policies (ibid., 254–255).

With this broad political backing, technocrats took initiatives toward deregulation from 1983 to 1989. The economic team which retained control over the major economic portfolios took steps to reform the financial system, adopted a more open trade stance, and introduced a modern tax system (Ginandjar and Stern forthcoming, 17). Soeharto took his economic ministers’ advice, as he had on earlier occasions when resources were constrained. Menko Ali Wardhana and his economic ministers proceeded with their reforms when they had the formal authority, bureaucratic strength, political backing, and Soeharto’s personal support to act on such issues as trade, investment, exchange rates, interest rates, and taxes. The incremental approach included bank reforms in 1983; a tax reform at the end of that year; reform of the customs service in 1985; the devaluation of the rupiah in 1986; and partial trade reforms in 1986 and 1987. Investment controls were eased in 1986 and 1987, and in 1988 a package of deregulation measures in trade and customs was announced by Radius Prawiro, the new Menko (Bresnan 1993, 262–263).

But technocrats had lost their momentum and political support by the early 1990s. In the 1993 reshuffle, most of the technocrats were replaced by economic nationalists and bureaucrats (Ginandjar and Stern forthcoming, 17–18). This was in part because of the rise of nationalists led by Habibie and Ginandjar and in part because of the rise of a new breed of career bureaucrats who were able to obtain technical expertise by doing graduate work abroad (technocratic bureaucrats) and who were often supported by Soeharto and his family members and cronies.

Mar’ie Muhammad13) replaced J. B. Sumarlin as Finance Minister; Ginandjar Kartasasmita14) replaced Saleh Afif as State Minister for National Development Planning and BAPPENAS Chief; S. B. Joedono,15) Habibie’s ally, replaced Arifin Siregar as Trade Minister; while one of two remaining technocrats, Saleh Afif, was appointed as Menko to replace Radius Prawiro16) and another, Soedradjad Djiwandono, replaced Adrianus Mooy as BI Governor.

It is also important to note that the Indonesian economy was undergoing major changes by the early 1990s. The private sector emerged as the driving force for economic growth. There was a general surge in foreign direct investment after the 1985 Plaza Accord as realized foreign investment rose from USD0.3 billion in 1985 to USD4.3 billion in 1995. Most notable was the shift in the ratio of non-oil and gas revenue receipts as a proportion of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), which rose from slightly more than 8% in 1985–86 to nearly 12% in 1994–95 (ibid., 19, 22). But attempts at curbing vested interests were not very successful. As Menko, Saleh Afif knew that eliminating or even reducing the monopolies Soeharto’s cronies controlled would be impossible. Protectionism also reared its head in the form of Soeharto’s son’s national car project, which began in 1996 and was routinely ridiculed as the “family car project.”

But most important was the fact that as private capital flows increased in the 1990s, the government found it increasingly difficult to manage the exchange rate regime. The BI purchased foreign currencies to manage increasingly large capital inflows and to prevent an appreciation of the rupiah, thereby increasing the money supply and forcing the BI to offer higher Certificates of Deposit rates to raise interest rates, which in turn invited more private capital inflows under the pegged exchange rate regime. As the economy overheated and the real exchange rate appreciated, imports grew rapidly while exports slowed down. Though the government took steps to reduce domestic demand, it failed to address the issue of export growth. As a result, the growing trade imbalance and Indonesia’s debt, above all short-term private debt, began to rise significantly. The BI widened the intervention bands around the pegged exchange rate in a belated effort to introduce more flexibility into the foreign exchange market and to warn offshore borrowers that they were taking considerable foreign exchange risks that had to be covered. But widening the bands was immediately followed by pressures that drove the exchange rate to the appreciation edge of the band. Serious concerns were also raised when it became known that the president’s cronies and family members were using state banks to obtain foreign funds for a range of large investment projects since such borrowings were assumed to have a measure of sovereign guarantee. In short, adherence to the exchange rate regime in place led in the 1990s to significant and large unhedged foreign exchange exposure by many Indonesian companies. Eventually, widespread bankruptcies would follow when the exchange rate regime collapsed in 1997–98.

Technocrats in Crisis

The implicit inconsistency between the open capital account policy and the reliance on a pegged exchange rate was exposed when the economic crisis started in Thailand and spread to Indonesia (Ginandjar and Stern forthcoming, 17, 34–35). Technocrats initially believed that Indonesia’s economic fundamentals were sound and viewed the crisis as containable.17) They in fact characterized it as a “mini crisis” that could be used to redress long-term structural problems which had not been addressed after the deregulations lost steam in the early 1990s. Between 1989 and 1996, real GDP growth averaged 8%; the overall fiscal balance remained in surplus after 1992; public debt as a share of GDP fell; and inflation hovered near 10%. Confident of Indonesia’s sound economic fundamentals, technocrats seized the opportunity to persuade Soeharto to introduce structural reforms as they deemed fit and to address structural problems such as expanding bad loans in the banking sector, the dependence of business groups on short-term dollar-denominated funds from foreign sources, and the control of Soeharto’s children, lieutenants, and crony business tycoons over commanding heights of the Indonesian economy.

The government abandoned its long-standing crawling peg exchange rate regime on August 1, 1997; in September, the government announced 10 policy measures, which technocrats named their own IMF conditionality, calling for financial and fiscal tightening and structural reforms, including the suspension of government development projects and banking sector reforms, i.e., bailing out healthy banks which faced temporary liquidity difficulties, merging unhealthy banks with other banks, or else liquidating them (Shiraishi 2005, 33; Ginandjar and Stern forthcoming, 48).18)

Yet the rupiah kept going down; by early September 1997, it plunged below the symbolic USD1:Rp3,000 line. On October 8, Widjojo persuaded Soeharto to ask for assistance from the IMF. The President appointed Widjojo Nitisastro to head the economic team to make the necessary preparations to notify the IMF (Djiwandono 2004, 63). The team was composed of members of the Monetary Board—Minister of Finance Mar’ie Muhammad, Minister of Trade and Industry Tungky Ariwibowo, State Secretary Moerdiono, Economic Advisors Widjojo Nitisastro and Ali Wardhana, and BI Governor Soedradjad Djiwandono. Interestingly, Ginandjar Kartasasmita, BAPPENAS Chief, was not included in the team. A small team who negotiated the program in details assisted the team, which was composed of Director General of Financial Institutions (MOF) Bambang Subianto, BI Managing Director Boediono, and Assistant to Coordinating Minister for Economic and Financial Affairs Djunaedi Hadisumarto.

In November 1997, the government signed the letter of intent (LOI) with the IMF. The President was well aware of the essence of the program. But Soedradjad Djiwandono tells us in his memoirs that whether the program should be precautionary or stand-by was never brought up in discussions between the economic team and the President. After the signing of the first LOI, BI Governor proposed at an economic team meeting that the team should explain the details of the program, including the meaning of first and second line of defense and the issue of conditionality, to the President. But Widjojo Nitisastro, the chairman of the team, decided to wait for a better moment. This never happened (ibid., 72).

The November 1997 LOI was based on the assumption that the crisis was essentially a moderate case of contagion and overshooting of the exchange rate. The program was thus designed for such a mild crisis (Ginandjar and Stern forthcoming, 49). But the LOI required every structural and bureaucratic reform that were deemed good for Indonesia. Both technocrats and the IMF wanted to use the crisis to achieve what Indonesian technocrats had worked for. Taking over the broad reform agenda without fully appreciating what the reforms entailed, what political and social changes they implied, and the capacity of the government to manage such rapid economic change, the team and the IMF not only weakened the focus of its own agenda but in the end undermined the political structure that had evolved under Soeharto over 40 years (ibid., 109).19)

The structural reforms required by IMF not only threatened to hurt the business interests of Soeharto’s children, his crony business tycoons, and his lieutenants, but also worked to undermine Soeharto’s huge patronage networks and the informal funding mechanisms of state agencies (including the military). When the government closed 16 troubled banks and suspended government development projects right after it signed the agreement with the IMF, Soeharto learned that he was duped. He allowed his son to take over another bank and revived government development projects the government had suspended and which were controlled by his family and crony businesses. The closure of banks also triggered a bank run and led to a systemic crisis in the banking sector.

Technocrats’ attempt to correct the “distortions” of cronyism backfired because they failed to understand the huge political significance and functions of patronage under the New Order. In trying to rein in the activities of Soeharto’s children as well as cronies, the technocrats not only antagonized their President, but unwittingly triggered a crisis in an already jittery market. Bank closures, rather than addressing the question of unhealthy banks, had the opposite effect, undermining confidence in all private banks and precipitating an open political confrontation between the presidential family and the Minister of Finance and BI Governor. The presidential family won the battle. But the price paid was high: the market confidence in the government will in complying with the IMF conditionality was deeply undermined, while technocrats lost the presidential confidence.

The most contentious issue between the President and the economic team was the question of liquidity. The BI had to deal with banks that suffered from bank runs, but adding liquidity into the banking sector could jeopardize the efforts to strengthen the rupiah and possibly violate IMF conditionality. The BI thus found itself in between the two opposing camps. “On the one hand, the President mounted pressure for easing liquidity to help the weakening real sectors. On the other hand, the Fund (IMF) kept reminding BI of the need to keep interest rates high to defend the rupiah as agreed upon in the LOI” (Djiwandono 2004, 99). Besides, the President instructed state banks to start lending to small and medium scale enterprises with subsidized rates of interest. To make things worse, this scheme was designed by the President and some Cabinet ministers and senior officials of several ministries without consulting either the Governor of BI or the Ministry of Finance (ibid., 112–113). Soedradjad Djiwandono asked for the presidential approval to raise the interest rate in compliance with the LOI, but he never got it (ibid., 113). Instead the President instructed the BI to inject liquidity into the troubled banks and loosen monetary controls. The resulting sharp increase in liquidity support from the last quarter of 1997 to 1998 spurred further deterioration of the macro-economic situation and increasingly strained the relationship between the government and the IMF (Ginandjar and Stern forthcoming, 95). Sino-Indonesian businesses benefited the most from the liquidity support. A 2000 study by the Supreme Audit Agency (Badan Peneriksi Keuangan) claimed that around Rp138 trillion of the BLBI funds issued was misused between 1997–98 (ibid., 96).

Then, in December 1997, Soeharto fell seriously ill and did not attend the ASEAN summit meeting. This instantly transformed the economic crisis into a political crisis. Conflict manifested itself again between the government and the IMF in January 1998 when the government announced a draft budget with no surplus, in spite of the IMF requirement of a 1.3% GDP surplus in the November agreement. The draft budget was also criticized for its “unrealistic” tax revenue and exchange rate assumptions. In reaction, the rupiah plummeted by 70%, reaching 10,000 rupiah per dollar. Another round of negotiations between the government and the IMF began. This time, though, it was Soeharto himself, and not the technocrats, who took charge of the negotiations with IMF representative Stanley Fisher (ibid., 51)—another sign that the President had lost faith in his economic team. To compound the matter, Soeharto pointedly chose not to invite the Minister of Finance and the Governor of BI to the official signing of the LOI.

By that time, US high officials began to see Soeharto as part of the problem. Soeharto understood this very well and wanted to wage what he called “guerrilla warfare.” He let the IMF spell out all the structural reform measures it wanted (which amounted to over 100) without any intention of abiding by the conditionality (Shiraishi 2005, 24; Ginandjar and Stern forthcoming, 53). Soeharto also entertained the possibility of introducing a currency board system as a solution to the crisis, calling it “IMF plus”; this was supported by some officials in the MOF (Ginandjar and Stern forthcoming, 52). Japan and the United States, however, were alarmed since the ill-timed introduction of a currency board system would instantly deplete Indonesia’s foreign currency reserves and devastate the Indonesian economy while providing Soeharto’s children and cronies with a small window of opportunity for bailout. BI Governor Soedradjad Djiwandono opposed the idea and was dismissed in February 1998.20) In a few weeks, Deputy Governor of the BI, Boediono, was also dismissed.21) Ginandjar writes: “For a time it seemed that Finance Minister Mar’ie Muhammad would be headed for a similar fate but he survived for reasons that may never be known” (ibid., 101).

With the economic team in disarray, Japan and the United States intervened. President Clinton sent former Vice President Walter Mondale in March 1998 to dissuade Soeharto from introducing a currency board system. Suspicious of US intentions, however, Soeharto was in no mood to listen to the US envoy. The meeting was cut short when Soeharto rejected Mondale’s suggestion about the need for “political reform.” Shortly thereafter, Japanese Prime Minister Ryutaro Hashimoto visited Indonesia, met with Soeharto, persuaded him not to introduce the currency board system, and opened the way for yet another IMF rescue package, which was to be agreed on in April 1998.

In the meantime, Soeharto was re-elected president once again on March 11, 1998, with B. J. Habibie as his vice president. The positions of Menko and BAPPENAS chief were held by Ginandjar Kartasasmita. Fuad Bawazir,22) who was known to be close to Soeharto’s children and in favor of introducing a currency board system, was appointed as the Minister of Finance, while Syahril Sabirin,23) the only survivor of the BI massacre and in support of a currency board system, had replaced Djiwandono as BI Governor. The new cabinet thus further reduced the role of technocrats with some ministers becoming closely identified with the presidential family.

After his re-election, Soeharto established the Economic Stabilization Council with Menko Ginandjar Kartasasmita as its executive chairman. Ginandjar promptly set as his top priority the need to repair relations with the international community and regain market confidence. The committee also had Anthony Salim, the son of Indonesian Chinese business tycoon Liem Sioe Liong, as Secretary General (ibid., 55–58). He also regularly consulted with Widjojo.

Ginandjar was in charge of negotiations with foreign governments and the IMF. His counterparts were the so-called “Three Musketeers”: US Treasury Undersecretary for International Affairs, David Lipton; Japanese Vice Minister for International Finance, Eisuke Sakakibara; and German Director General of International Affairs, Ministry of Finance, Klaus Regling. The committee decided to abandon the currency board scheme, reestablished dialogue with the IMF, and concluded a new LOI two weeks after the new cabinet was formed. Ginandjar states that all the programs resulting from the negotiations were embraced by the Indonesian economic team as its own. All the government departments were given specific and written instructions by the Menko to carry out reforms within their areas of responsibilities and to abide by the timetable (ibid., 56–57).

But it was too late. By then Soeharto’s politics of stability and economic development had been thoroughly discredited. Its collapse was triggered by the fuel price increase in May 1998. Following massive riots in May in Jakarta and elsewhere, Soeharto resigned. The New Order came to an end.

The Remaking of Indonesian Technocracy

B. J. Habibie succeeded to the presidency according to constitutional stipulation. He had a weak presidential mandate and power base. He chose to present himself as a reformer, initiating measures in the name of reformasi, which eventually led to the transformation of the Indonesian political system from developmental authoritarianism into decentralized democracy.

The basic shape of the post-Soeharto regime was defined by the constitutional revisions and new laws introduced over the transitional period under Presidents Habibie (May 1998–October 1999), Abdurrahman Wahid (October 1999–July 2002), and Megawati Sukarnoputri (July 2002–October 2004). These constitutional revisions—which took place incrementally from 1998 to 2003—reformulated the relationship among the three branches of government in terms of the division of powers. The President and the Vice President, formerly elected by the People’s Consultative Assembly (Majelis Permusyawaratan Rakyat, hereinafter MPR), are now to be elected directly; the legislature is to consist of the DPR (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat), the Council of People’s Representatives and the newly created DPD (Dewan Perwakilan Daerah), the Council of Local Representatives; and the MPR, the highest decision-making body under Soeharto which saw the peak of its power in the transitional years under B. J. Habibie and Abdurrahman Wahid, lost much of its powers. While Soeharto controlled the MPR through direct and indirect appointment of its majority members and by extension all the government organs, constitutional revisions in the post-Soeharto era have created a division of powers in which the presidency has to share power with a parliament whose members are directly elected and in which political parties dominate. Elections, both parliamentary and presidential, are to be held every five years and define the national political calendar. Though still powerful with its own sphere of influence and interests curved out in the name of national unity and security, the army no longer dominates politics. The military doctrine of dual functions was scrapped and military officers were withdrawn from the civilian arm of the state. New defense and police laws were enacted. The army domination over the military establishment came to an end. Navy and air force officers serve as a military chief in rotation with army officers. The police was separated from the military (Matsui and Kawamura, 2005, 75–99; Honna, 2013).

Free and fair parliamentary elections were held in 1999, 2004, and 2009. The first direct presidential election, which brought the current president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono to power, took place in July and October 2004. The second presidential election brought the incumbent back the second term in 2009. Democratization has also gone hand in hand with decentralization. New laws on local autonomy and local finance in 1999 have created local governments which are no longer accountable to the central government but answer to the local parliament. While Soeharto could in effect appoint provincial governors, district chiefs, and mayors, the central government now has to share powers with local governments. More powers and resources have been devolved to local governments, above all district and municipality governments at the expense of—and often in tension with—the central and the provincial government. An increasing proportion of central government budget has been allocated to local governments: from 19.3% in 2001 to 30.7% in 2005, when direct elections of local chiefs started, to 33.9% in 2007. Expanded authority combined with guaranteed and increasing resource allocation to the local governments created incentives for local groups to create more local governments and to control such governments with their own men. The number of districts and municipalities increased from 311 in 1998 to 478 in 2008 while the number of provinces expanded from 27 in 1998 to 41 in 2008. Parties formed coalitions to control local governments, the composition of a governing coalition different from one locality to another, some being made up with only nationalist parties or Islamic and Islamist parties, but more often combining both nationalist and Islamic and Islamist parties (Okamoto 2010).

In democratic politics, the DPR, the lower house of the parliament, has emerged as a new power center along with the presidency and the military, and electoral politics has assumed a crucial role in organizing the government. Yet no single party controls the parliament. A party or two may emerge or disappear every election, but the multiparty system will remain with no single party controlling the parliament, as long as the current electoral system stays and deep social divisions along religious (pious Muslims vs. statistical Muslims and non-Muslims, traditionalist vs. modernist Muslims), ethnic, and class lines inform party divisions. It is not easy for any president to organize any cabinet to work as a team because a “team” composed of technocrats, professionals, military officers, bureaucrats, and politicians from different parties needs to be cobbled together not only for the business of governing but also for achieving a majority in the parliament.

This is evident in all the teams assembled by the successive Presidents. Instrumental in checkmating Soeharto in his final days, Ginandjar Kartasasmita emerged as a key player in the Habibie government, along with the President himself and General Wiranto, Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces and Defense Minister. Ginandjar, not Habibie, assembled his economic team as Menko, including Boediono24) (formerly Ginandjar’s deputy for macro-economic affairs at BAPPENAS before his transfer to the BI) as BAPPENAS Chief and State Minister for National Development Planning, Bambang Subianto25) as Minister of Finance (appointed at Widjojo’s recommendation), and Syahril Sabirin as BI Governor. The arrival of Abdurrahman Wahid as the fourth President marked a clear break with the New Order past. Elected as an outcome of back room dealings among political party bosses in the MPR, his cabinet was dominated by party politicians: out of 35 cabinet ministers in his first cabinet, 22 were party politicians while 6 were retired military officers and 4 career bureaucrats; in the second cabinet, 11 party politicians, 4 military officers, 6 career bureaucrats in the 26 member cabinet. Kwik Kian Gie,26) Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (Partai Demokrasi Indonesia Perjuangan, hereinafter PDI-P) politician and Vice President Megawati’s confidant, became Menko. Bambang Sudibyo,27) Gadjah Mada accounting professor and a confident of National Mandate Party (Partai Amanat Nasional) Chairman and People’s Consultative Assembly (Majelis Permusyawaratan Rakyat, MPR) General Chairman, Amien Rais, was appointed Finance Minister. Djunaedi Hadisumarto,28) inheriting the technocratic mantle, served as Chairman of BAPPENAS, but was not made State Minister for National Development Planning. Syahril Sabirin remained as BI Governor. In the second Abdurrahman Wahid cabinet, Rizal Ramli—a former student activist with the background in engineering who was sent by technocrats to do graduate work at Boston University, but who rebelled against his seniors by openly attacking technocracy and establishing his own business consultancy firm upon his return to Indonesia—became Menko, while Prijadi Praptosuhardjo, previously Bank Rakyat Indonesia director, became Finance Minister.29)

Mindful of the fate of Abdurrahman Wahid whose administration was chaotic and who was eventually ousted from power in impeachment, Megawati was careful not to antagonize any party. The Jakarta elite had also come to the agreement that political alliance alone would not suffice to lift Indonesia out of the mess and that Megawati needed “professionals” unbound by party politics. She gave ministerial positions to party representatives, but reserved some of the more important economic posts for non-partisan professionals and her confidants. Dorodjatun Kuntjoro-Jakti,30) UI professor of political economy whom Soeharto in his final days sent to the United States as ambassador, was appointed Menko; Boediono Minister of Finance; and Kwik Kian Gie Minister of National Development Planning. Burhanuddin Abdullah replaced Syahril Sabirin in 2003 as BI Governor.

By the time Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono came to power in 2004, Boediono had restored the credentials of technocrats by his success in achieving macro-economic stability. With his party controlling only 10% of the parliament, it was imperative for the President to gather a stable parliamentary majority. He enlisted most of the political parties except Megawati’s PDI-P for the government coalition, while encouraging the Vice President to take over the Golkar leadership and destroying the opposition coalition of PDI-P and Akbar Tandjung-led Golkar. But he paid a high price. He gave almost one third of ministerial positions to party representatives in organizing his cabinet and allowed the Vice President to have a say in appointing economic team members, even though parties, including the Golkar, in the governing coalition do not hesitate exploiting opportunities to promote their own gains at the expense of the President and the government.

As mentioned earlier, the fact that the Indonesian economy did well under Yudhoyono enhanced the stature of his Finance Minister Sri Mulyani and was a factor in his designation of BI Governor and former Menko Budiono as his running mate in the 2009 presidential election. Given the new division of powers and the effects of decentralization on center-local relations, however, it is clear that the president can no longer preside over Indonesia’s political life in the way Soeharto had done before. This was amply demonstrated recently when Sri Mulyani was sent off to the IMF in 2010 despite (or perhaps because of) her success as Finance Minister because her principled budget-making angered many politicians, particularly Golkar boss Aburizal Bakrie, who demanded pork barrel funding. Even a technocrat of her stature who has enjoyed good relations with the President can be politically expendable.

The government can take policy initiatives to address problems and policy issues only on the basis of an achieved national consensus. But achieving a national consensus under the new democratic dispensation is a challenge precisely because the era of political demobilization is over and various social forces are making themselves felt in political processes.

There are important commonalities among those who now dominate local and national politics: the great majority of national and local parliamentary members are men, born in the areas they represent (putra daerah), highly-educated at least formally, with activist backgrounds in party, youth, and religious organizations (whether nationalist or Islamic), belong to Indonesia’s small but fast expanding middle classes, and are represented by business people, professionals, civil servants, school teachers, military and police officers, religious teachers, and journalists. There are hardly any parliamentary members with peasant, labor, and urban poor backgrounds.

The implications are clear. In national as well as local politics, local men with middle-class backgrounds dominate. In part a product of Soeharto’s politics of stability and development, this emergent elite thrived under Soeharto, but now encompasses formerly marginalized (but nonetheless middle-class) groups composed of journalists, school teachers, and religious leaders. This elite shares in the belief that economic growth is the key to Indonesia’s future, and is in a position to make its belief a part of the national agenda, even though its members disagree on how to achieve growth and they do not shy away from calling for populist and protectionist measures in the name of welfare whenever those measures suit their political and economic interests. In his election manifesto, Yudhoyono (2004) made the achievement of economic growth, along with maintaining national unity, central to his agenda. The new system of decentralized democracy has also worked for him, despite its decisive curbing of the executive power of the presidency.

At the same time, however, decentralization has given real powers and resources to local governments, above all district chiefs and mayors. To see how decentralization combined with democratization, above all direct elections of local chiefs worked, it is useful to examine two provinces with very different sets of social conditions, North Sumatra and Central Java (including the special region of Yogyakarta).

In North Sumatra, which is ethnically and religiously highly diverse (with 33% Javanese, 16% Tananuli Bataks, 10% Toba Bataks, 8% Mandailing Bataks, 6% Nias, 5% Karo Bataks, 5% Malays, 3% Angkora Bataks as well as smaller minorities, while 65% Muslim, 27% Protestant, 5% Catholic, 3% Buddhist), the number of districts and mayoralty increased from 19 in 2000 to 26 in 2008 (BPS 2001a). Seventeen small parties (which do not have members in the national parliament) along with seven national parties helped forge governing coalitions that differed in composition and membership from one district to another (on average, about 2.7 small parties in a coalition). In 12 out of 26 districts/municipalities, governing coalitions were made up with a combination of nationalist parties (PD, Golkar and/or PDI-P) and Islamic parties; only 4 districts/municipalities were controlled by Islamic/Islamist parties.

In Central Java which is ethnically and religiously homogeneous, with 98% Javanese and 96% Muslim, a different picture obtains (BPS 2001b). The number of districts and municipalities has remained the same. A smaller number (2.3 on average) of small parties joined governing coalitions in smaller number of districts and municipalities (6 out of 40); in 18 out of 40, a coalition of nationalist parties (PD, Golkar and/or PDI-P) with Islamic and Islamist parties, while 6 districts and municipalities came under the governing coalition of Islamic and Islamist parties.

The implications should be clear enough. In ethnically diverse North Sumatra, ethnic politics are now very much localized and contained in local politics because ethnic groups have ended up with creating their own local governments and/or joining governing coalitions. Religious politics have also to some extent come to be contained locally because the areas with a high concentration of pious Muslims now have Islamic/Islamist party coalition under which local governments introduce religious regulations to meet the demands of pious Muslims, while in other districts these religious issues remain muted because of the coalition that brings together both nationalist and Islamic/Islamist parties.

To put it simply, democratization and decentralization have “contained” ethnic and religious politics by localizing them. Politics of identity, once suppressed by Soeharto, now thrives, but as a local issue, with some exceptions (such as pornography) flaring up occasionally. “National” issues are now largely framed by, and very much tied to, a politics of economic growth, with the central government deriving its public support and electoral success from its perceived capacity to deliver economic growth, create jobs, reduce poverty, and keep inflation under control as we can see in Fig. 1. The language of economic growth—a byproduct of economics as a discipline—is part of a discursive field in which technocrats claim expertise. But the irony is that the elevation of this discourse of economic growth to the national agenda comes at a time when technocrats have become no more than technicians who are charged with “fixing” the economy while having no control or say over how politics, or more specifically the purpose of politics, is defined. The transformation of technocracy and the changing conditions under which technocrats now work need to be located—and can only be understood—within this larger context of political and ideological transformation, rather than a simple question of economics and economic policy.

Fig. 1 Economic Performance and Public Ratings of the President and the Democratic Party

Source: Lembaga Survei Indonesia (LSI) (2009).

This is not to say that Indonesia did not undergo important institutional changes for the economic policy-making in these transitional years. The Central Bank Law, enacted in 1999 under Habibie, guaranteed the independence of the BI from the government for the first time; and prohibited the BI from purchasing government domestic bonds. BI’s independence was tested in 2000 when President Abdurrahman Wahid asked BI Governor Syahril Sabirin to resign while promising him other positions. Syahril Sabirin refused to resign and was arrested and put in jail, but was subsequently cleared of all charges by the High Court.31) It was a symptom of the technocrats’ marginalization from economic policy-making that Wahid’s first Coordinating Minister (Menko) for Economic Affairs, Kwik Kian Gie, went so far as to refer to his government as “they” and did not bother to coordinate. No State Minister for National Development Planning was appointed, because the President wanted to undercut the power of BAPPENAS.32)

Under Megawati, who came to power in July 2001, restoring macro-economic stability became the top priority. Megawati appointed “professionals” who were unbound by party politics to two strategic posts for this objective. Boediono33) was named Minister of Finance and Burhanuddin Abdullah replaced Syahril Sabirin as BI Governor. Both Boediono and Burhanuddin did their jobs well to achieve macro-economic stability and banking sector reform to pave the way for Indonesia’s graduation from the IMF program. But the economic ministers did not work as a team. Megawati confidant Kwik Kian Gie, appointed Minister of State for National Development Planning, openly attacked his own agency, BAPPENAS, as a nest of corruption.

Megawati years also witnessed two major institutional developments in the economic policy-making. One was the enactment of Law Number 17 on State Finance in 2003. It introduced the European Union Maastricht treaty-type rule to achieve economic and financial stability, legally requiring the government to keep the annual budget deficit below 3% of the GDP and the total government bonds issuance (both central government and local government bonds) below 60% of the GDP. In other words, the law holds the government politically accountable for maintaining a self-restraining fiscal policy.

This law led to the reorganization of the Ministry of Finance, expanding its powers at the expense of BAPPENAS, the National Development Planning Agency. The Agency for Economic, Fiscal, and International Cooperation Research was created out of the former Agency for Fiscal Analysis and was made responsible for budget making, while the budget planning function was assigned to the Directorate General for Budgetary and Fiscal Balance, which was created out of the former Directorate General of Budgeting. The power to make the Fiscal Policy and Macro Economic Framework, a power previously shared by BAPPENAS and MOF, came under MOF jurisdiction with the passing of the new law. Equally important, the budget which had previously been classified as the routine budget and development budget and were respectively under the jurisdiction of the MOF and BAPPENAS came under MOF jurisdiction with the elimination of the routine and development budget distinction. By abolishing the distinction, the law stripped BAPPENAS of its control over the development budget (Hill and Shiraishi 2007, 123–141).

Under Soeharto, BAPPENAS was in charge of national planning, the development budget, coordination with foreign governments and international organizations for international assistance, and development project coordination and implementation. This in effect made BAPPENAS the super ministry to oversee the entire economic policy-making. In its heyday, Widjojo Nitisastro, Soeharto’s most trusted economic adviser, served as Coordinating Minister for Economic and Fiscal Affairs, State Minister for National Development Planning, and Chief of BAPPENAS simultaneously. Under Soeharto, national development planning was implemented by presidential decree, not by law. The legal status of BAPPENAS was not clearly defined. Its effectiveness depended on its chief’s ability to work with Soeharto and on his commitment to prioritizing national development.

In the post-Soeharto era, BAPPENAS lost much of its powers. A new law on the national development planning system was enacted in 2004 in the final days of the Megawati presidency. It granted legal status to BAPPENAS and stipulated that the Chief of BAPPENAS support the president in formulating the presidential national development plan and assume responsibility for drafting the central government development plan. Now, however, almost two thirds of budget for public works, for instance, is allocated to provinces and districts/municipalities. BAPPENAS not only lost its control over the development budget, but also has no say in almost two thirds of the public works budget.

The Indonesian technocracy evolved under the New Order from 1966 to 1998 as a strategic component of its politics of stability and economic development. Technocrats were instrumental in persuading Soeharto to adopt reform measures in the 1980s that imposed market discipline on the government’s developmental policies. Indonesian technocrats as a group were effective because they were cohesive in their adherence to the three principles of balanced budget, open capital account, and pegged exchange rate system, and also because they enjoyed Soeharto’s confidence and could therefore function as his right arm in formulating and executing national development policies. In the 1990s, however, technocrats faced increasing challenges from economic nationalists entrenched in the government agencies such as the Ministry of Industry, the Investment Coordination Agency and the BPPT/BPIS (Agency for State Strategic Industries), Soeharto’s family and crony business interests, and bureaucrats who were trained abroad and rose in their individual departmental hierarchies as career officials. In their attempt to regain their power, technocrats tried to seize the opportunity offered by the 1997 currency crisis to persuade Soeharto to go to the IMF and to introduce reform measures, but the move backfired because technocrats lost his confidence.

The transitional governments led by B. J. Habibie, Abdurrahman Wahid, and Megawati Sukarnoputri sought institutional and political alternatives to the discredited Soeharto-era economic policy-making process. These alternatives ranged from relying on technocrats while consulting key players in Indonesia’s economy and politics such as businessmen, mass media, politicians, public intellectuals, and future technocrats, as well as foreign governments and international organization (as Ginandjar Kartasasmita did as Coordinating Minister under Habibie) to outright disregard for technocracy and its institutional bulwark BAPPENAS (under Abdurrahman Wahid) to the empowerment of MOF for the sake of macro-economic stability at the expense of BAPPENAS and long-term national planning (under Megawati).

In retrospect, however, it is decentralized democracy, introduced in those transitional years, which created a new set of conditions for a politics of economic growth: social divisions along ethnic and religious lines are no longer suppressed as they had been under Soeharto but are now contained locally, while the politics of economic growth is embraced not only by middle-class people who dominate local and national politics but more broadly by the population. With the enactment of a series of laws governing the BI and government finance as well as constitutional revisions, a new institutional framework based on the two preeminent agencies of BI and MOF is now in place for macro-economic policy-making. But technocrats are now more dependent on their ability to court public support for policy measures they are advocating and to secure the backing of the president and the vice president who may or may not agree on any policy issue and whose decisions on economic policy will be influenced by non-technical and highly political issues such as public reception, parliamentary approval, and personal chemistry. The era of political demobilization during which technocrats had a freer hand in formulating economic policies and could rely on the backing of the president alone is over. In retrospect, however, technocracy has never been shielded from “politics.” If it once looked as if this had been the case under the New Order, it was because Soeharto used the enormous state power to demobilize popular politics. But those days are over. Although the institutional foundation is now in place for the independence of the Central Bank and the fiscal prudence of the Ministry of Finance, their performances ultimately depend on who runs these institutions and the complex political processes that inform their decisions and operations.

Accepted: November 1, 2013

References

Asanuma Shinji 浅沼信爾. 2005. Zaisei no Jizoku Kanosei: Indoneshia no Kesu 財政の持続可能性―インドネシアのケース [Financial sustainability: The case of Indonesia]. Unpublished manuscript.

Badan Pusat Statistik (BPS). 2001a. Penduduk Sumatera Utara [Population of North Sumatra]. Jakarta: BPS.

―. 2001b. Penduduk Jawa Tengah [Population of Central Java]. Jakarta: BPS.

―. 2001c. Penduduk D.I. Yogyakarta [Population of Yogyakarta Special Region]. Jakarta: BPS.

Bresnan, John. 1993. Managing Indonesia: The Modern Political Economy. New York: Columbia University Press.

Djiwandono, J. Soedradjad. 2004. Bank Indonesia and the Crisis: An Insider’s View. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Fachry Ali; Eahtiar Effendy; Umar Juoro; Musfihin Dahlan et al. 2003. The Politics of Central Bank: The Position of Bank Indonesia Governor in Defending Independence. Jakarta: LSPEU.

Ginandjar Kartasasmita; and Stern, Joseph J. Forthcoming. Reinventing Indonesia. Singapore: World Scientific.

Hill, Hal; and Shiraishi, Takashi. 2007. Indonesia after the Asian Crisis. Asian Economic Policy Review 2(1): 123–141.

Honna Jun 本名 純. 2013. Minshu-ka no Paradokkusu: Indoneshia ni Miru Ajia Seiji no Shinso 民主化のパラドックス―インドネシアにみるアジア政治の深層 [Paradox in democratization: Deep strata of Asian politics as seen in Indonesia]. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

Iijima Satoshi 飯島 聰. 2005. Indoneshia Kokka Kaihatsu Keikaku Shisutemu Ho no Seitei to sono Igi ni tsuite インドネシア国家開発計画システム法の制定とその意義について [About the significance of the establishment of Indonesia’s national development planning system]. Kaihatsu Kinyu Kenkyu-sho Ho 開発金融研究所報 [Journal of JBIC Institute] 25 (July): 167–197.

Lembaga Survei Indonesia (LSI). 2009. Efek Calon Terhadap Perolehan Suara Partai Menjelang Pemilu 2009: Trend Opini Publik Updated 8–18 Februari 2009 [Effect of candidates for party support toward the 2009 elections: Public opinion trend updated on February 8–18, 2009]. Jakarta: LSI.

Matsui Kazuhisa 松井和久; and Kawamura Koichi 川村晃一. 2005. Indoneshia So-Senkyo to Shin-Seiken no Shido: Megawatei kara Yudoyono e インドネシア総選挙と新政権の始動―メガワティからユドヨノへ [From Megawati to Yudhoyono: Indonesian general elections and the beginning of a new administration]. Tokyo: Akashi Shoten.

Oiwa Takaaki 大岩隆明. 2005. Indoneshia ni okeru Seisaku, Seido Kaikaku to sono Enjo e no Gani: Keikaku, Zaisei, Kinyu Bumon o Chushin ni インドネシアにおける政策・制度改革とその援助への含意―計画・財政・金融部門を中心に [Institutional changes in policy-making in Indonesia and its implications for and effects on assistance]. Unpublished manuscript.

Okamoto Masaaki 岡本正明. 2010. Minshuka shita Taminzoku Kokka Indoneshia ni okeru Antei no Poritikusu 民主化した多民族国家のインドネシアにおける安定のポリティクス [Politics of stability in democratic and multi-ethnic Indonesia]. Ph.D. dissertation, Kyoto University, 2010.

Shiraishi, Takashi. 2005. The Asian Crisis Reconsidered. In Dislocating Nation-States: Globalization in Asia and Africa, edited by Patricio N. Abinales, Noboru Ishikawa, and Akio Tanabe, pp. 17–40. Kyoto: Kyoto University Press.

1) Widjojo Nitisastro (UI; Ph.D., University of California, Berkeley) joined Soeharto’s advisory team in 1966 as a member of the National Economic Stabilization Board. He was appointed Chairman of BAPPENAS in 1967 and served in that position until 1983, while also serving as Menko from 1973 to 1983. He was appointed as advisor to BAPPENAS (1983–98) and presidential economic advisor (1993–98), while working as professor of economics at UI from 1964 to 1993.

2) Ali Wardhana (UI; Ph.D., University of California, Berkeley) was professor of economics at UI. From 1966 to 1968, he was a member of the Economic Advisory Team of the President, served as Minister of Finance from 1973 to 1983, and replaced Widjojo as Menko from 1983 to 1988.

3) Emil Salim (UI; Ph.D., University of California, Berkeley) served as Deputy Chief of BAPPENAS (1967–71), State Minister for State Apparatus (1971–73), Minister of Transportation, Communication and Tourism (1973–78), State Minister for Development Supervision and Environment (1978–83), and Minister of State for Population and Environment (1983–93).

4) Subroto (UI; Ph.D., University of Indonesia) served as Director General of Research and Development at the Department of Trade, Minister of Manpower, Resettlement and Cooperatives, and finally Minister of Mining and Energy (1983–88) before becoming Secretary General of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, OPEC, in 1988.

5) Mohammad Sadli (UI; Ph.D., University of Indonesia) studied at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and the University of California, Berkeley, and served as Minister of Manpower (1971–73) and Minister of Mining and Energy (1973–78).

6) J. B. Sumarlin, a UI graduate, who obtained his Ph.D. from the University of Pittsburgh started his technocratic career as deputy chairman for fiscal and monetary matters at BAPPENAS (1970–73), then served as Vice Chairman of BAPPENAS (1973–82) and State Minister for State Apparatus (1973–83); as State Minister for National Development Planning as well as BAPPENAS Chairman (1983–88); and finally Minister of Finance (1988–93).

7) Saleh Afif, another UI graduate, obtained his Ph.D. from the University of Oregon and started his technocratic career as State Minister for State Apparatus and Deputy Chairman of BAPPENAS (1983–88) before being appointed State Minister for National Development Planning and Chairman of BAPPENAS (1988–93) and finally Menko (1993–98).

8) Adrianus Mooy was a Gadjah Mada graduate, and had a Ph.D. in Econometrics from the University of Wisconsin. He joined BAPPENAS in 1967, and rose up the BAPPENAS hierarchy, serving as Bureau Chief for Domestic Finance, Assistant to the Minister for Development Planning/BAPPENAS, and Deputy Chairman for Fiscal and Monetary Affairs (1983–88) before being appointed BI Governor (1988–93).

9) Rachmat Saleh, a UI graduate, joined the BI and climbed the central bank hierarchy as Representative of BI in New York in 1956; Secretary to the Board of Directors of BI in 1958; Head of Research, and later Vice Director of BI, in 1961; Director of BI, 1964; and Chairman of the Directorate of Foreign Exchange Institute, Jakarta, in 1968; BI Governor (1973–83) before being appointed Trade Minister (1983–88).

10) Arifin Siregar graduated from the Netherlands School of Economics, Rotterdam, in 1956; got his Ph.D. from the University of Muenster, West Germany, in 1960; then worked as Economic Affairs Officer in the United Nations Bureau of General Economic Research and Policies in New York in 1961 and the United Nations Economic and Social Office, Beirut, in 1963. He was an Economist at the Asian Development, IMF, in 1965 and a representative of the IMF in Laos (1969–71), then joined the BI as Director in 1971, served as Alternate Governor of the IMF in Indonesia (1973–83) and finally as BI Governor (1983–88) before being appointed Trade Minister.

11) Soedradjad Djiwandono, BI Governor (1993–98), was a graduate of Gadjah Mada (1963) and had a Ph.D. from Boston University (1980). Married with a daughter of Sumitro Djojohadikusumo, the founder of the Faculty of Economics, University of Indonesia, he joined the Ministry of Finance (MOF) as a staff member of the Director General for Monetary Affairs in 1964, rose to Junior Minister for Trade (1988–93) under Arifin Siregar, and was subsequently appointed BI Governor in 1993.

12) IGGI (Inter-Government Group for Indonesia) was established in 1966 and was succeeded by the CGI (Consultative Group on Indonesia) in 1992 as an international framework for consultation to provide concessionary loans to the Indonesian government.

13) Mar’ie Muhammad, a UI Accounting graduate with an Islamic activist background, joined the MOF in 1970 and rose in the Finance bureaucracy to serve, from 1988–93, as Director General of Taxes before being appointed as Minister of Finance from 1993–98. Soeharto gave him the finance portfolio because he had known him since his student activist days and because he was impressed by his performance as the clean and forceful Director General of Taxes.

14) Ginandjar Kartasasmita, a Chemical Engineer graduate of the Tokyo University for Agriculture and Technology (1960–65), rose in the state secretariat bureaucracy from the G-5 of the Supreme Command as one of future Vice President Sudharmono’s lieutenants in the early days of New Order to Junior Minister for the Promotion of Domestic Products from 1965–83. He then served as Chief of the Investment Coordinating Board (BKPM) from 1985–88; as Minister of Energy from 1988–93; and finally as State Minister for National Development Planning and Chief of BAPPENAS from 1993–98. He was given the job of the BAPPENAS chief in part because he enjoyed the presidential trust and in part because he was acceptable to B. J. Habibie who was intent on increasing his bureaucratic power at the expense of the technocrats.

15) Satrio Budihardjo Joedono was born on December 1, 1940 in Pangkalpinang, Bangka. A graduate of UI (Economics), he obtained his Ph.D. in Public Administration from the State University of New York, Albany. While teaching at UI (promoted to professor in 1987) and serving as director of the Institute for Economic and Social Research (1970–78) and Dean of the Faculty of Economics (1978–82), he also served as assistant to the Minister of Trade (1970–73) and to the Minister of Research (1973–78), Assistant Minister of Research and Technology (1978–82 and 1986–88) and Assistant Minister for Industry and Energy (1988–93) before being appointed as Minister of Trade (1993–95). Known to be incorruptible, he was elected Chairman of the Board of Audit, 1998–2003.

16) Radius Prawiro, a graduate of the Nederlandse Economische Hogeschool (The Netherlands Economic High School), obtained his Ph.D. from the UI. He began his technocratic career as Governor of BI (1966–73), and served as Minister of Trade in 1973–83, Minister of Finance (1983–88), and finally Menko (1988–93).

17) What Djiwandono has to say in his memoirs is instructive. He writes: “A question that I kept being asked was, if our fundamentals were strong how come Indonesia suffered so much? To shed some light on this issue, I like to think that there is a different perception about what constitutes the macro fundamentals of an economy. I would argue that at least until the Asian crisis, macroeconomists generally thought about growth of national products, exports, current accounts, inflation rates, unemployment rates and several other macro indicators every time they talked about economic fundamentals. I would even argue that, in general, macroeconomists did not include the state of the banking sector as an important item in economic fundamentals. Banking issues have traditionally been treated as microeconomics. . . . In other words, in a macro-economic analysis, the workings and soundness of the banking sector had been assumed to be present or taken for granted” (Djiwandono 2004, 28).

18) Djiwandono says about the bank closure as follows: he went to President Soeharto to propose closing seven small commercial banks as a first step in December 1996. But the President did not approve the proposal and instructed Djiwandono to finalize a government decree to regulate bank closure. It was issued at the end of 1996 as Government Decree No. 68, 1996. In April 1997, he went back to the President with the proposal to close the seven banks once again. This time he approved it, but asked him to postpone execution until after the 1997 general election and the general assembly of the People’s Consultative Assembly in March 1998. The financial crisis began in July 1997 (Djiwandono 2004, 128).

19) It is useful to note what Djiwandono has to say about the conditionality and the bank closure. He writes on the IMF conditionality that “my instincts told me then that our government would not be able to fulfill the stringent conditionality that went with the stand-by arrangement” (Djiwandono 2004, 64). He also tells us about the bank closure as follows: “I was comfortable about liquidating the seven banks with the President’s approval. However, I had to admit that liquidating more than twice the number of banks really scared me” (ibid., 130).

20) To be precise Soedradjad Djiwandono never opposed a CBS because he was afraid to publicly air his difference with the President on the matter. But he says he also knew that being vague was the best technique in that peculiar environment to send a message to the President that he did not support the CBS scheme (Djiwandono 2004, 9, 19).

21) In fact all the BI managing directors except one, Syahril Sabirin, were dismissed before their terms ended (Djiwandono 2004, 3). This untimely dismissal demonstrated his intention to the public that he would punish any official for violating his unwritten rule not to embarrass his family (ibid., 12).

22) Fuad Bawazir who is of Arab descent and a Gadjah Mada graduate with a Ph.D. from the University of Maryland rose in the MOF hierarchy. Similar to Mar’ie Mohammad, he had an Islamic activist background and granted favors to Soeharto’s family members while he was Director General of Taxes before he was appointed the Minister of Finance.

23) Syahril Sabirin, a graduate of Gadjah Mada University (1968), obtained his Ph.D. in 1979 from Vanderbilt University. From 1969 to 1993, he worked at the BI, rising in the bank hierarchy and serving as section chief for current account (1982–83) and for bank development (1982–84), bureau chief of economics and statistics (1985–87) and of clearing (1987–88), and director (1988–93). He was senior financial economist at the WB (1993–96) before returning to BI as director (1997–98), and finally as governor (1998–2003).

24) Boediono was trained abroad (B.A., University of Western Australia; M.A., Monash University; Ph.D., Wharton School of Business, University of Pennsylvania) and served as deputy for fiscal and monetary affairs at BAPPENAS (1988–93) and Deputy Governor of the BI (1993–98) before being made State Minister for National Development Planning and BAPPENAS Chief in 1998.

25) Bambang Subianto, a graduate of Leuven Catholic University in Belgium, rose in the finance hierarchy to become Director General of Monetary Affairs, and was appointed the first Chief of Indonesian Bank Restructuring Agency, only to be dismissed by Soeharto after a few months.

26) Kwik Kian Gie, born in Juwana, Central Java, is of ethnic Chinese ancestry. A graduate of the Nederlandse Economische Hogeschool (The Netherlands Economic High School) Rotterdam in 1963, he worked as an investment company executive and joined the Indonesian Democratic Party (PDI). He served as a member of the People’s Consultative Assembly (MPR) from 1987 to 1992. He became the chief economic advisor to Megawati Soekarnoputri after her election as the Chairman of PDI in 1994. He headed the party’s research and development department until Megawati elected as Vice President before he was appointed as Menko under Abdurrahman Wahid.

27) Born in Temanggung, Central Java, on October 8, 1952, Bambang Sudibyo, a graduate of Gadjah Mada University and a Ph.D. (Business Administration) from the University of Kentucky (1985), spent most of his career at Gadjah Mada University. He joined the National Mandate Party when it was established in 1998 and served as chairman of its Economic Council before he was appointed as Finance Minister under Abdurrahman Wahid.

28) Under normal circumstances, Djunaedi Hadisumarto should have inherited the mantle from Boediono to serve as State Minister for National Development Planning and Chief of BAPPENAS. But Abdurrahman Wahid did not appoint any minister for national development planning. Djunaedi, a UI graduate and UI professor of economics, had served as Secretary General of the Ministry of Transportation and Vice Chairman of BAPPENAS under Boediono before being promoted to Chairman of BAPPENAS.

29) Rizal Ramli, a graduate of the ITB and a student activist, obtained Ph.D. in economics from Boston University in 1990. Upon completion of his graduate work, he established an economic research and publishing firm, Econit, and emerged as a critic of Soeharto’s crony Liem Sioe Liong, Freeport, and the IMF. He served as Head of the National Logistic agency (Bulog) before he was appointed as Menko from 2000 to 2001. Prijadi Praptosuhardjo, Abdurrahman Wahid confidant, is a graduate of the Bogor Institute of Agriculture (IPB) where he studied fishery. He spent his career in Bank Rakyat Indonesia (BRI) where he became friends with Abdurrahman Wahid. He was appointed as BRI director in 1992 but failed in his bid to become the bank president despite Abdurrahman Wahid’s recommendation. Instead, he was appointed Minister of Finance.

30) Dorodjatun Kuntjoro-Jakti, a UI Economics graduate, holds a Ph.D. (Political Economy) from the University of California at Berkeley, and was ambassador to the United States before being appointed as Menko under Megawati.

31) For Abdurrahman Wahid’s attempts to oust Syahril Sabirin from the BI governorship, see Fachry et al. (2003, Ch.5). It should be noted that Abdurrahman Wahid even entertained the idea of liquidating the BI to oust him and that he was supported by some of the key players in the economic policy-making in those days such as Kwik Kian Gie, Rizal Ramli, and Prijadi Praptosuhardjo.