Contents>> Vol. 1, No. 1

Javanese Women and Islam:

Identity Formation since the Twentieth Century

Kurniawati Hastuti Dewi*

* Center for Political Studies, the Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI); Graduate School of Asian and African Area Studies, Kyoto University, 46 Shimoadachi-cho, Yoshida Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan

e-mail: kurniawatihastutidewi[at]yahoo.com

DOI: doi.org/10.20495/seas.1.1_109

Despite the vast research over the last three decades devoted to the lives and social interaction of Javanese women, little has been written on the formation of these women’s identity by focusing on its development from the twentieth century up to the early twenty-first. This paper endeavors to show that the religio-cultural identity of Javanese women was forged through a number of sociocultural circumstances. While revealing different features of the relationship between Javanese women and Islam, I shed light on the role Islam played, particularly since the early twentieth century, in providing transformative power to the role and status of Javanese Muslim women, manifested by the adoption of such Islamic dress codes as veiling, as also an important means of identity politics. I argue that new Islamic discourses have always been born out of the desire to challenge the conservative understanding of the role and status of Javanese women in different historical periods.

Keywords: Javanese women, Islam, identity formation, veiling, identity politics

Introduction

Since the late fifteenth century, Islamization has brought about a significant social transformation in Java. Islamization in Java was marked by the transition from the ancient East Javanese Hindu-Buddhist regimes (Majapahit Kingdom) to the Javanese Islamic rulers on the north coast, and later to the Mataram Islamic Kingdom (Yogyakarta). The shifting configuration wrought changes not only in Javanese religiosity but also in Javanese livelihoods, affecting everyone, including the women. However, over the last three decades, studies of women in Java have tended to overlook Javanese women’s dynamic intersection with Islam, framing it within identity formation. For example, some earlier scholars—including Hildred Geertz (1961), Robert Jay (1969), and Koentjaraningrat (1957)—focused on the structure of the relationship between the sexes in Java. Ann Stoler (1977) examined rural Javanese women’s economic independence under the Dutch cultivation system (1830–70). In the urban-contemporary context, Norma Sullivan (1994) observed the livelihood of a Javanese lower-class urban family in Yogyakarta, and Hotze Lont (2000) studied urban Javanese women’s responses to microfinance credit institutions. In a rural setting, Valerie Hull (1976) researched the different degrees of Javanese women’s autonomy in Yogyakarta. In the context of the household, G. G. Weix (2000) studied the agency of elite Javanese women in controlling the home-based cigarette business in Kudus, while Ratna Saptari (2000a) focused on the utilization of kin-based and inter-household networks. The dominant role of Javanese women in trading and economic activities has been the subject of copious research by prominent academics such as Geertz (1961), Cora Vreede-De Stuers (1960), Suzanne Brenner (1995), Barbara Hatley (1990), and Ward Keeler (1990).

Scholars have only recently begun to consider Islam as a variable affecting Indonesian women. Susan Blackburn (2002) looked into the twentieth-century discourse of Indonesian Muslim women’s roles in politics, and then further examined the history of Indonesian women in political Islam (2008). Sally White and Maria Ulfah Anshor (2008) provided current snapshots of the growth of Islamic perspectives after 1998. Kathryn Robinson (2009, 11–29) offered the latest analysis of Islam and Indonesian women after 1998, where she provided some examples of the local adaptation (such as in Java) to Islam in the early 1920s. In all, I suggest that there is a gap between the empirical situation of Javanese women’s intersection with Islam, which was an important element shaping the formation of the women’s identity, and the bulk of research that has only recently begun to address it. This paper bridges that gap by providing a portrait of the role of Islam in the identity formation of Javanese Muslim women, focusing on the subject from the twentieth century up to the early twenty-first.

I contend that the identity formation of Javanese Muslim women has been influenced by the nature of Islam and the political configuration in which, since the early twentieth century, new Islamic discourses have always emerged from the need to challenge conservative understandings of the role and status of Javanese women. Based on the nature of Islamic thinking and practice that influenced the different historical periods as the defining force in shaping Javanese Muslim women’s identity, I identify four periods depicting these women’s interaction with Islam. While in the first phase the nature of “syncretic” Islam in Java constrained particularly the Javanese noble-women, in the second phase, since the early twentieth century, Islam (pioneered by the Islamic reformism of Muhammadiyah) and nationalism were positive transformative powers in the social positioning of Javanese women by employing a new discourse and setting out a portrait of the ideal Javanese Muslim woman. In the third phase, the resurgent Islam of the 1970s lent considerable spirit to Javanese Muslim women to express identity politics as a way of countering the New Order’s severe stance on political Islam. In the fourth phase, Islam as a belief has provided a strong religious foundation for female leadership in local politics that has facilitated the rise of Javanese Muslim women as political leaders in direct local elections since 2005.

Koentjaraningrat (1985, 2) defined Java as encompassing the Javanese people, culture, and linguistic group of Central and East Java, while the western part of the island was home to the Sundanese. Based on Koentjaraningrat’s concept, the examples explored in this paper are centered mainly on Javanese women in Central and East Java, although a few are derived from West Java to give a general picture of Islamization on the island of Java. The historical records cited in this paper date back from the 1850s through to the 1950s and were obtained mainly from the National Library of Indonesia in Jakarta, with a few from the library of the Center for Southeast Asian Studies in Kyoto University, Japan, in January 2010 and April 2010.

Identity Formation: Current Debate and Position

Erik Erikson’s work (1950), based on Freudian psychological theory, is a pioneering treatise on identity formation. However, Erikson and neo-Eriksonian identity theories such as those proposed by James Marcia (1980), or James Cote and Charles Levine (1987), are currently being evaluated in order to incorporate sociocultural aspects. For example, Cote (1996) and Gerald Adams and Sheila Marshall (1996, 438) argued that identity formation was influenced by macro and micro environments,1) as did Seth Schwartz (2001, 49) and Elli Schachter (2005, 390). In this paper, I adopt Adams and Marshall’s concept (1996) that identity formation is influenced by macro and micro environ ments.2) In revealing the identity formation of Javanese Muslim women, I initially present the experiences of some individual Javanese women in dealing with Islamic norms, values, and ideology that were socialized, constructed, and communicated through signs, symbols, and expectations either in language or discourse in the early stages of Islamization in Java. These are useful for gaining an insight into the general picture of the Javanese Muslim women’s identity.

There are numerous studies on identity formation in Indonesia.3) This paper is positioned within the ethno-religious gender-based group of studies because it observes specifically the identity formation of ethnic Javanese women. In dealing with Islam, I pay special attention to the norm and practice of wearing the veil, because I believe it is an important aspect signifying identity formation in Javanese Muslim women, which later became an important means of creating a distinct political identity and attracting Islamicbased voters in direct local elections first implemented in 2005.

Islamization and Its Consequences for Javanese Women

At least up to the late fifteenth century, Hindu civilization was the defining force that shaped the identity of Javanese women. For example, Javanese noblewomen enjoyed a preeminent status and played a strong role in the family and community during the Hindu-Javanese period, including in the Majapahit Kingdom around the thirteenth to the fifteenth centuries, as noted by Peter Carey and Vincent Houben (1987, 15) and Ann Kumar (2000, 88–104). However, the situation changed considerably following Islamic penetration into Java.

Scholars often disagree on the nature of Java’s Islamization. For example, Clifford Geertz’s “syncretic Islam” (1960, 5–6, 130) asserts that the Javanese religious system is one of syncretic Islam characterized by a mix of animism, Hinduism, and Islam. Anthony Reid (2000) suggested that Southeast Asian Islam, including that in Malaya and Java, was primarily influenced by mystical Sufism brought by Sufi orders (Malay tarekat). Mark Woodward (1989, 2–17) believed that Islamic Sufism was the most influential element in Islamization in Java, while Jay (1963, 6) argued that Islam’s spread to Java involved the contestation between syncretism (embraced by the Javanese aristocracy of the Mataram/Yogyakarta Islamic court) and orthodox Islam (embraced by the northeastern coastal rulers).

Despite the diverging theories, it is obvious that the history of Islamization in Java is closely linked to the religion’s practice by the nobility, as Barbara Andaya (2000, 246) suggests, where the Mataram/Yogyakarta aristocracy took control of Islamization following the defeat of the orthodox Islam (Jay 1963, 11–13) of the northeastern coastal rulers in the mid-seventeenth century. I suggest it was the Javanese noblewomen who initially interacted considerably with, and had to conform to, the Islamic norm. Here, I believe the Javanese noblewomen’s early intersection with Islam was not a calm one. The next section explores the tensions surrounding the Javanese noblewomen’s adjustment to the new Islamic code of behavior and principles.

Constructing Identity as Javanese Muslim Women: Struggle and Adjustment

By the end of the sixteenth century, there was a new Islamized Javanese elite as a consequence of Islamic penetration into Java (Ricklefs 2007, 2). The Mataram Islamic court under Sultan Agung (1613–46) actively promoted, to borrow from M. C. Ricklefs, “Islamic mystic piety,” but by the mid-nineteenth century this was to be challenged by Sharia-oriented reformers such as students at pesantren (Islamic boarding schools) and religious teachers from the north coast of Java ( ibid. , 31–52).

While the spread of Islam on the island of Java had started long before the 1870s, stories of its proliferation were recorded in Slompret Melayoe, the first Malay-language newspaper published in Java (Semarang). The Slompret Melayoe from 1870 to 1897 features various issues related to the spread of Islam. For example: the inauguration of two ponds in the Kendal Mosque in which women participated ( Slompret Melayoe, August 24, 1878);4) the influence of Islam on marriage and ceremony in Anyer ( Selompret Melaijoe, September 3, 1870); neighborhood conflict arising from the noise of beduk,5) which in this case was amplified during the days and nights of Ramadan in Pandeglang ( Slompret Melaijoe, February 19, 1876); the story of pengulu 6) at the Semarang Mosque explaining the rationale of issuing talak 7) between husbands and wives ( Slompret Melaijoe, May 17, 1873); and stories of pilgrimage or Haj ( Selompret Melaijoe, October 1, 1870, March 11, 1871; Slompret Melaijoe, December 31, 1875).

Equally interesting are the published opinions on the change in manners of Javanese who had recently returned from the Haj. Olo Ngangoer ( Slompret Melaijoe, March 8, 1873) criticized the tendency among Javanese who had undertaken the Haj to adopt Arabic-style clothes and shoes, and their preference to be addressed as “tuan hadji.” Ngangoer proposed that Javanese pilgrims should retain traditional Javanese dress to preserve Javanese values and customs, because he believed that being a haji (a pilgrim) was not always a guarantee of morality and obedience to the Islamic code. All of the foregoing indicate that Islamization in Java had a significant impact not only in signifying Islamic piety through devotion to the five pillars of Islam,8) but also in defining the ideal relationship between men and women, behavioral changes related to the adoption of new Islamic principles or Arabic customs, and the gradual spread of mosques that soon dominated the social and architectural landscape in Java. A vivid picture of Islamization in Java can also be seen in the adoption of Islamic-style dress by Javanese women, which had been expected since the sixteenth century and spread further after the early twentieth century, as we shall see below.

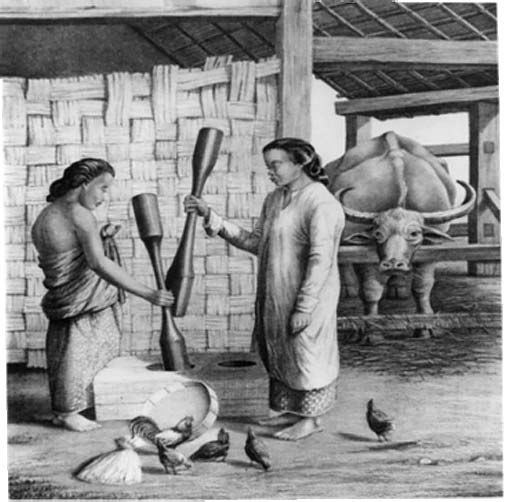

The first code of conduct commonly associated with Islam is the adoption of the veil ( kudung, or veiling).9) Andaya (2000, 247) suggested that around the sixteenth century, upper-class women were expected to adopt the veil because Islam decreed that physical beauty was not for public display. However, I believe this normative expectation of veiling among noblewomen had not proliferated widely in Java between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries. There are barely any photographs or pictures reflecting widespread adoption of the kudung among either noblewomen or ordinary women on the island in the nineteenth century. I suggest that the traditional dress style of Javanese women—namely, the kemben 10)—was the dominant norm until the twentieth century. This is evident in Photo 1 and 2. Photo 1 below shows the typical Javanese noble-woman’s dress .

Why had Javanese women not embraced the kudung by the 1800s? I believe this had to do with the social and political conditions in Java at the time. Under the compulsory crop system from 1830 to 1870 ( kultuurstelsel), all Javanese peasant men were conscripted as forced labor to service Dutch economic prosperity (Ratna 2000b, 17). It was a time of hardship for the majority of Java’s indigenous population. There was famine among the peasants due to poverty, which was compounded by the outbreak of a typhoid epidemic in Central Java from the 1840s to the 1850s (Ricklefs 2001, 157–161). Eduard Douwes Dekker’s book, Max Havelaar, clearly describes the harsh life of Javanese peasants due to exploitation by the colonial government and the Javanese aristocracy.11)

|

Photo 1 A Javanese Noblewoman Source: Seorang wanita Jawa berdarah biru ( Java: Past and Present, n.d.). Reproduced from the collection at the Indonesian National Library, Jakarta, January 2010. |

Photo 2 Javanese Women Pounding Rice Source: Para wanita Jawa menumbuk padi. Neder-landsch Oost-Indiche, 1856. Reproduced from the collection at the Indonesian National Library, Jakarta, January 2010. |

Moreover, rather than paying attention to Islamic dress style, Javanese noblewomen were busy defending their existence vis-à-vis the Javanese noblemen’s declining supremacy. For example, Florida (1996, 212), in assessing Javano-Islamic literature, reveals that the intensification in Javanese elite men’s writing of women’s literature in the Surakarta court around the end of the nineteenth century was a result of the diminution of indigenous royal men’s power in Java following the end of the Diponegoro War in 1830. Without military or political authority, the royal male elite, particularly in the Surakarta court, tried to assert their power by writing on women’s literature to show the dominance of the male voice in constructing gender relations in late-nineteenth-century Java. For example, Piwulang Estri resonates with the male voice of the ideal, elite Javanese woman as a good wife (or co-wife) who is perfectly accommodating of her husband’s polygamous desires and submissive to his authority ( ibid. , 210–211). A similar illustration of the total submission of a woman to her husband’s authority is given in Serat Murtasiyah, a poem in the genre of Islamic santri (devout Muslim) dating back to early-nineteenth-century Java. The poem describes the exemplary, virtuous Javanese wife who surrenders completely to her husband—including to his violence—and devotes herself to his happiness ( ibid. , 217–219). This example corresponds with Koentjaraningrat’s (1980, 13) observation that Javanese intellectuals had to accept Islamic concepts and incorporate them into the Central Javanese cultural tradition from the second half of the eighteenth century.

The second practice associated with Islam, although it is actually not new to Javanese custom ( adat), is polygamy. During the Hindu-Buddhist civilization, it was common for noblemen to maintain co-wives ( selir) or concubines. The practice persisted. For example, one edition of Selompret Melaijoe contains a description of Javanese priyayi (noblemen) who often had two or three wives ( Selompret Melaijoe, October 26, 1887). Another well-known example is that of R. A. Kartini (1879–1904), daughter of the Regent of Jepara, Central Java. Born of a mother who had been trapped in a polygamous marriage, Kartini wrote in one of her letters that she would be more than willing to end this unfair adat, which she believed was exacerbated by a narrow interpretation and practice of Islam.12) Although Kartini opposed polygamy, she could do nothing when in 1903 her father asked her to marry the Regent of Rembang, who already had three secondary wives (Thomson Zainu’ddin 1980, 9–10; Cote 2005). One instance of resistance to polygamy is Pakubuwono IX’s first queen, who committed suicide following her husband’s decision to take another wife. There is also Sekar Kadhaton, the daughter of Pakubuwono VII, who refused to get married, in rejection of the male ideology of polygamy and the construction of the virtuous and defeated wife (Florida 1996, 215–216).

The third practice, which I believe already existed in adat but was amplified by Islam, is pingitan.13) Islam decreed that pious women and noblewomen should lower their gaze before men, to preserve their purity. Men were encouraged to show their devotion publicly, such as by going to mosques, while women were expected to stay home as a manifestation of their devotion and dignity (Andaya 2000, 246). Seclusion, according to Andaya ( ibid. , 246–247), was a condition for noblewomen in Java before the 1500s; and when the Dutch arrived in Banten in 1596, they made the same observations of both Java and Flores. The practice persisted until the late nineteenth century among priyayi women such as Kartini, who underwent pingitan from 1892—when she was 12 years old—to 1898 (Thomson Zainu’ddin 1980, 4; Kartinah 1955).

In the early years of Java’s Islamization (from the 1700s to the end of the 1800s), Javanese noblewomen were those most affected, precisely because of the nature of Islamization that was implemented in the Javanese royal court. Ordinary Javanese women seem to have been less affected. For example, poverty made it difficult for lower-class Javanese men to have more than one wife (see Locher-Scholten 2000, 32–33). Javanese noblewomen struggled with the various rules of conduct imposed on them by the Javanese male elite through textualized norms such as Piwulang Estri or Serat Murtasiyah. This was the “authority-defined” context of identity (to borrow from Shamsul A. B. 1996) invoking the Javanese noblewomen to show their Islamic modesty.

In my view this is actually a further consequence of the nature of the syncretic Islam propagated by the Mataram Kingdom since the mid-seventeenth century. I argue that Islamization at this stage was not intended to liberate Javanese women from the established adat (for example, the practice of polygamy and pingitan explored earlier). I believe that in this early stage of Islamization, Javanese noblewomen found Islamic discourse and practice more hampering than liberating. Although by the mid-nineteenth century there were professional Javanese Islamic groups of putihan (the “white” or “pure ones”) in pesantren communities throughout Java’s coastal areas, I believe their appearance had little impact on Javanese women because the pesantren allowed only males to attend sessions, as Ricklefs (2007, 50–70) points out. However, the situation changed considerably with the Islamic reformist movement of the early twentieth century, which gradually opened the door for Javanese women to actively pursue Islamic teachings and allowed their entry into public schools. This will be discussed shortly.

Consciousness, Contestation, and Revelation of Identity

The spread of Islam in Java after the early twentieth century occurred at the same time as the rise of women’s emancipation, in line with the spirit of nationalism and the establishment of the Islamic reformist movement. The awakening of women’s consciousness in the East Indies (now Indonesia) had been preceded by a largely Java-based movement to educate women. Kartini has been regarded as the champion of women’s emancipation. After her death, her spirit inspired subsequent efforts to educate women through various educational institutions (Vreede-De Stuers 1960, 58–59). The period between 1912 and 1928 also recorded a rise in the number of women’s associations both across and outside of Java. Prominent among them was Putri Mardika, founded in Jakarta in 1912 with the aid of the nationalist organization Budi Utomo (Indonesia, Department of Information, 1968, 10; Sukanti 1984, 85–86).

Some of the women’s associations published their own magazines to voice their concerns. In the Putri Mardika magazine there is evidence to show how Islam was perceived vis-à-vis the old-fashioned Javanese adat in defining the ideal woman in the early twentieth century. Putri Mardika’s goal, which was inspired by Kartini’s spirit, was as follows: “Mardika” means freedom, which gives women room to express their thoughts as independent citizens who are able to make their own decisions ( Poetri Mardika 1915; 1917). This goal was underpinned by the rising awareness among bumiputra Jawa ( lit., the sons of Java, or indigenous Javanese) that the old-fashioned adat (child marriage, pingitan, no schooling, polygamy, and total submission to the husband) were no longer acceptable and that things must change.14)

The early twentieth century was also an era of a global consciousness of nationalism, as reflected in Putri Mardika’s goal that both men and women were important elements in the nation’s aspirations concerning the progress and dignity of the bumiputra (Sd 1915a; S Koesoemo 1917a). Putri Mardika proposed that the ideal Muslim woman should be able to maintain the good aspects of adat and imbibe Islamic religiosity so that she would not be easily fooled by her husband in her march toward progress, in order to ensure that Muslim women would not follow in the footsteps of their European counterparts who had crossed boundaries (S Koesoemo 1917b). In practice, Putri Mardika encouraged women to participate in the public sphere in partnership with men (Sd 1915a). The association provided scholarships for women to study in Java or in the Netherlands ( Poetri Mardika 1915) and built schools for women in West Java, with branches in East Java (Bestuur 1917). Isteri, the official magazine of the Indonesian Wives Association (Perikatan Perhimpunan Isteri Indonesia, or PPII, founded in 1928), also framed women’s progress within the national consciousness. For example, in one of its 1932 editions it exhorted Indonesian women to be knowledgeable so as to be progressive and to work alongside men in the fight for Indonesian independence (Patrem 1932).

The limits of Javanese women’s development were framed by the concept of kodrat 15) or fitrah. 16) K. H Dewantoro, leader of the Perguruan Taman Siswa, an educational institution founded in Yogyakarta in 1922, used the concept of kodrat without reference to Islam when explaining women’s progress. He believed that in trying to achieve progress in the public sphere alongside men, women should remember their kodrat rooted in iman (belief in God)—without reference to any religion (K. H Dewantoro 1938). Kodrat, without reference to Islam or other religions, was also used by PPII representatives in the Budi Utomo Congress ( Isteri 1931b).

Conversely, the concept of fitrah with reference to Islam is apparent in Taman Moeslimah, an Islamic magazine published in Solo and affiliated with Muhammadiyah.17) It states that the progress of Javanese women should be in accordance with fitrah—not taking on men’s work (as doctors, machinists, or politicians, for instance) and not mixing with men publicly (Sriwijat 1926). A more progressive view was printed in the Islam Raja magazine, which was also affiliated with Muhammadiyah and published in Solo. Asm Sdm (1939) said that Muslim women had an obligation to support public movements, or to be educators inside and outside of the home, to perform duties as good wives, and to propagate Islam. Later, in 1940, the norm of being a good wife was further specified as isteri Islam yang berarti (the truly Islamic wife), according to which Muslim women were expected to serve as best they could as wives and mothers ( Islam Raja 1940). Considering Islam Raja’s affiliation with Muhammadiyah, it may not be a coincidence that prior to 1940, ‘Aisyiyah (Muhammadiyah’s female branch) had introduced the classical book titled Isteri Islam yang berarti (in 1937), which focused on women’s private roles as wife and mother (PP Muhammadiyah Majlis ‘Aisyiyah n.d., 10).18) To facilitate Muslim women’s growing understanding of Islamic principles, they were encouraged to join preacher schools to become female preachers ( mubhalighot), such as those in Solo ( Islam Raja 1939). These examples reveal the influence Islam had in defining the ideal Javanese woman. Islam was perceived as a guidance and norm (such as fitrah) that differentiated its followers from those pursuing European-style progress. In the broader context, the general discourse of Indonesian women’s progress is framed in the spirit of nationhood and the concept of kodrat.

At the same time, my observations uncovered criticism of Islamic practices. R Soepomo (1931) argued that while women’s status and rights according to customary law ( hukum adat) were equal to those of men (such as in inheritance or divorce) before the arrival of Islam, Islamic practices replaced this customary law, which in effect degraded their status and rights. Dewi Sekartadji (1932b) also criticized Islam, which she believed deprived women of the rights—such as rights in divorce and polygamy—that they enjoyed under Hindu civilization. Sekartadji’s writing certainly provoked debate. Muslims writing in the Bintang Islam magazine, and a reader in Medan, refuted Sekartadji’s opinion. Sekartadji responded by arguing that she did not intend to degrade Islam; rather, she was urging a return to the spirit of nationalism exemplified in Java’s past Hindu civilization, and prioritization of Indonesian independence (Dewi 1932a). There was also criticism of the Islamic norm of segregating women in public meetings such as the Indonesia Raya Congress (Rit 1931–32).

Maria Ulfah Santoso, a prominent Indonesian activist, criticized the Islamic practices further by arguing that while the Qur’an was not intended to degrade women, in practice the husband enjoyed a greater religious right in initiating talak and that the religious court often refused a woman’s initiation of divorce, thereby rendering wives, especially battered wives, more vulnerable to spousal abuse (Maria 1940). In response, devout Muslims, such as those writing in the Solo magazine Islam Raja, defended Islam by arguing that it was a religion of progress and was in full compliance with modernity, citing several santri who succeeded in managing modern educational institutes, hospitals, orphanages, and a publishing house (Sarwo 1940).

The above exploration clearly indicates a shifting perception toward the contribution of Islam to women’s progress. While around the 1920s Islam had been perceived as an alternative value to steer Indonesian women’s progress vis-à-vis European progress, between 1920 and 1940 there was a mounting debate between those who perceived Islam as detrimental to women, and the champions of reformist Islam (Muhammadiyah) who defended Islamic practices by acknowledging Islam’s contribution to progress.19) Although the above discourse in newspapers and magazines refers mostly to Indonesian women, and a few specifically refer to Javanese women, I believe it had a significant impact on the identity formation of Javanese women, who had been surrounded by the raging debate on a daily basis. The deliberations intensified toward the end of the first quarter of the twentieth century, contesting the definition of the ideal Javanese Muslim woman.

Since the early twentieth century, the norm of wearing the kudung gained acceptance; polygamy has persisted even to this day, while pingitan has become a relic of the past. Andree Feillard’s study reveals that prior to the 1920s many women in the Indonesian archipelago wore the traditional kemben, but Islamization brought on the adoption of what would become the Malay-Indonesian dress consisting of the kebaya,20) the sarong, and the head shawl (Feillard 1999). This dress code was observed in both urban and rural areas, but particularly among santri, who wore a kain 21) wrapped tightly around their hips, a kebaya blouse, and kerudung,22) while rural women wrapped the kerudung around their necks ( ibid. ).

Islamic groups such as ‘Aisyiyah also promoted the adoption of the kudung, initially in Kauman, Yogyakarta. Since the 1920s, ‘Aisyiyah’s promotion of the kudungg was underpinned by K. H. Ahmad Dahlan’s eagerness to elevate the status of female priyayi (noble-women) and santri in Kauman. At the time, it was widely believed that the proper place of the priyayi was at home (Koentjaraningrat 1985, 242). The unquestioned acceptance of the Islamic-Javanese proverb “Wadon iku neroko katut, suwargo nunut” 23) indicated this subordinate status (Ahmad 2000, 96). Dahlan launched his pursuit to enhance women’s social status by citing from the Qur’an verse 97 of An-Nahl 24) and verse 124 of An-Nisa 25) (Pimpinan Pusat ‘Aisyiyah n.d.: 1). Dahlan, together with his wife Siti Walidah, developed a religious consciousness among Muslim women by sending girls in Kauman to formal schools (Alfian 1969, 272).

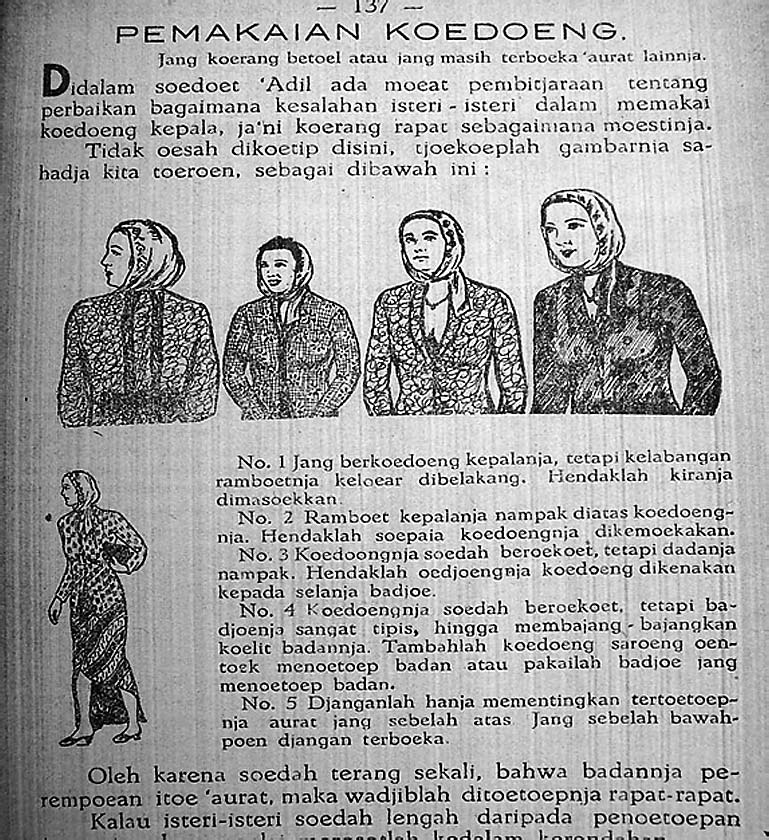

While Islam via Muhammadiyah under Dahlan’s leadership liberated Javanese women from the old-fashioned adat, the latter still had to conform to the Islamic norm of becoming wanita sholehah,26) through, among other things, wearing the kerudung. It was ‘Aisyiyah that initially introduced the Islamic woman’s clothing style, for instance wearing the jaritt as a lower cloth to cover the hips and legs, and the kebaya as an upper cloth in combination with the kudung, and socks to cover the feet (Lin 1952). ‘Aisyiyah’s propagation was facilitated by the Suara ‘Aisyiyah magazine, which began using the Indonesian language in 1928 ( Soeara ‘Aisjijah 1940; Pimpinan Pusat ‘Aisyiyah n.d., 30). Photo 3 illustrates the proper way of wearing the kudungg among (Javanese) Muslim women.

The wearing of the kudung was also demonstrated outside of Muhammadiyah, such as in the Islam Raja magazine, one of whose regular readers believed that wearing the kudung did not lower women’s status and that it was a religious obligation for Muslim women to wear it (Soeminar 1940). Much later, the Nahdlatul Ulama (NU)27) also adopted the kudungg but more tolerantly than did the Islamic reformists. Women in NU believed that an “open kudung” was the rule, and they did not talk about the jilbab 28) prior to the 1980s (Feillard 1999). Moreover, the adoption of veiling seems to have varied across social classes and across urban and rural settings. This can be seen from Jay’s notes (1963, 79) on the process of differentiation between orthodox and syncretic Islam in Modjokutho, East Java, around the 1960s. He observed that rural female santri wore a white headscarf that framed but did not cover the face; urban female priyayi and santri wore light and colorful scarves only when they went to town or attended upper-class—and therefore syncretic—urban affairs. According to Jay ( ibid. ), the adoption of the headscarf among santri and urban upper-class women resulted in the gradual disappearance of the scarf among abangan 29) communities.

In fact, the kudung and the segregation of women in public meetings did not meet with the approval of some Islamic leaders. For example, in a speech at the second convention of the League of Young Muslims (Jong Islamieten Bond, or JIB) in Solo in 1926, Hadji Agus Salim (1978, 66–71), a prominent Islamic modernist and nationalist, argued that veiling of women and their segregation in public meetings was not an Islamic but an Arabic adat or custom. He urged the JIB to free itself from false Arabic adat that did not stem from Islamic teachings. Although he opposed veiling and the segregation of women in public meetings, he defended polygamy because he believed the Qur’an allowed it ( ibid. , 62).

The persistence of polygamy to date is another interesting case in point. For example, the santri woman Siti Walidah—Dahlan’s wife—could do nothing about her husband’s polygamous marriage to four other women (Suratmin 1990, 38).30) Achmad Djajadiningrat, the assistant wedono or sub-district officer in Bojonegoro, as cited in Vreede-De Stuers (1960, 104), noted that polygamy was widely practiced among the upper class in Java, including civil servants, santri, and merchants. The 1930 census recorded the incidence of polygamy among Javanese and Madurese men at 1.9 per cent, lower than the rate in the outer islands (4 per cent); while among the Minangkabau it stood at 8.7 per cent ( ibid. ).

Polygamy was further endorsed under the Old Order (1945–66), when President Sukarno issued Government Regulation No. 19/1952, which provided government pensions to the multiple widows of polygamous civil servants (Blackburn 2004, 129). In response, women’s organizations held divergent positions. While ‘Aisyiyah ( ibid. ) and other Islamic women’s organizations defended the practice ( Harian Rakjat, October 14, 1952), Catholic women ( Harian Rakjat, October 13, 1952) and other women’s organizations, including Isteri Sedar, called for its abolition (Tj. T vis Si De 1940). Sukarno’s polygamous marriage in 1954 (Blackburn 2004, 130) also served to fuel the public debate on the issue. And last but not least, while pingitan was still practiced in Java in the early twentieth century among santri and priyayi, as Sewojo noted (cited in Vreede-De Stuers 1960, 51), it gradually disappeared following the rise of the Islamic reformist movement in 1912 and the emergence of women’s associations that encouraged education for girls.

The interpreters of Islamic religious texts have been predominantly male. For example, in Muhammadiyah, women were rarely included in the Majlis Tarjih (Council on Lawmaking and Development of Islamic Thought, founded in 1927), resulting in ‘Aisyiyah’s 40th Muktamar or Congress in Surabaya in 1978 recommending women’s involvement in the Majlis Tarjih ( Suara Muhammadiyah 1978).31) Similarly, in the NU tradition, interpretations of the divine message by male kyais (religious teachers) were prioritized and women’s voices were not officially taken into account until 1938 (Blackburn 2008, 88). However, this does not change the fact that they delivered a different discourse and interpretation of the roles and status of Javanese Muslim women compared to the old Javanese-Islamic literature such as Piwulang Estri or Serat Murtasiyah explored earlier. In turn, the teaching and interpretation of Islam since the early twentieth century—on issues of veiling, women’s education, segregation, child marriage, and the still-contentious issue of polygamy—facilitated a closer connection between Javanese women and Islam, leading to a change in perception of the status, rights, and obligations of their modern Islamic-Javanese identity. By conforming to the Islamic-style kudung, pious Javanese Muslim women reveal a new identity that remains distinct from their non-pious counterparts and even other non-Muslim Javanese women. The next section elaborates on the new stages Javanese Muslim women went through in trying to consolidate their identity in light of the social challenges of the New Order.

Individual Elevation and Collective Action: Revealing Identity Politics

The position of Javanese women during the New Order (1966–98) was largely influenced by Suharto’s iron grip on political Islam in the name of economic development. To consolidate power, Suharto steadily undercut the influence of political parties in the lead-up to the 1971 General Election (Emmerson 1978, 99) and promoted a confederation of functional groups, Golkar. Shortly afterward, in 1973, the New Order government launched the “fuse party” policy, which consolidated four existing Islamic political parties into a single entity called the United Development Party (Partai Persatuan Pembangunan); while the Nationalist, Protestant, and Catholic parties were merged into the Indonesian Democratic Party (Partai Demokrasi Indonesia) (Ricklefs 2001, 361; M. Rusli 1992, 4).

Despite the successful marginalization of Islamic political parties, the New Order policy ironically triggered the rise of pro-democratic Islam beginning in the early 1980s (Hefner 2000, 72). This was inspired by the resurgence of Islam elsewhere in the world, such as in Iran and Pakistan, in the 1970s. One of the pioneers of this cultural movement in Indonesia was Nurcholis Madjid, who proposed pararelisme Islam, which emphasized the oneness of Indonesia and Islam based on Islamic principles that were universal and inclusive (Nurcholish 1992). Similarly, Abdurrahman Wahid proposed pribumisasi Islam, in which Islam complemented Indonesian nation building. This Islamic cultural movement was also promoted by the two biggest Indonesian Islamic organizations, Muhammadiyah and Nahdlatul Ulama. The Muhammadiyah Congress in Ujung Pandang in 1971 declared no affiliation with political parties.32) The Nahdlatul Ulama Congress in Situbondo in 1984 declared a return to the “khittah 1926”—or a withdrawal from political praxis to strengthen individuals and society toward developing a civic culture as a basis for democracy (M. A. S Hikam 1999, 40). The younger generation of Javanese Muslim women grew up in this sociopolitical context.

This Islamic resurgence was grasped mainly by Muslim students in high schools and universities, particularly in Java, such as at the Bandung Institute of Technology, Indonesia University, Gadjah Mada University, the Education and Teaching Institute, and the Islamic State Institute. Why did Java figure prominently in this development? We must consider the historical and sociological facts that contributed to the rapid socio-political developments in Java. The 1952 figures from Indonesia’s Ministry of Home Affairs show the islands of Java and Madura as the most densely populated areas, a fact that can be attributed to natural factors such as fertile soil and cultivable land, amount of rainfall, and development initiatives by former Dutch administrators (Indonesia, Ministry of Social Affairs, 1954, 11). This situation persists to this day: for example, 63.83 per cent of the Indonesian population lived on the island of Java in 1971, and the number declined only to 60.12 per cent in 2000 (Leo et al. 2003, 4). Moreover, the percentage of women in Java was higher, at 59.32 per cent, than that outside Java, which constituted only 40.68 per cent in 1995 (Indonesia, Biro Pusat Statistik 1995, 11). This unequal population distribution is attributed to education, health facilities, and employment opportunities. Javanese women’s better access to education, as a result, can be seen in the percentage of illiterate women aged 10 to 19: while the lowest percentage—4.11 per cent —was in Yogyakarta province, the highest—32.12 per cent—was in West Kalimantan province in 1980 (Indonesia, Biro Pusat Statistik 1989, 102). Javanese women, therefore, had better opportunities to intersect with both progressive and conservative Islamic ideas, through higher learning.

One of the manifestations of the religio-cultural movement was the practice of adopting the veil among high school and university students in Java. Since the late 1980s there have been several studies on the rationale, dynamics, and meaning of veiling in Java. Brenner (1996) studied the gradual adoption of veiling among young Javanese women in universities and Islamic schools in Yogyakarta and Solo since the 1980s and concluded that in Java, the growing adoption of veiling marked not only a historical consciousness but also a path to modernity. Feillard’s (1999) study in the 1990s on veiling among elite women in Muhammadiyah and Nahdlatul Ulama in Java concluded that while veiling among ‘Aisyiyah was perceived as a pledge to a virtuous life, the traditionalist Islamic NU viewed the veil as a modern fashion accessory. Moreover, based on the dramatic increase in the number of Muslim female students who wore the veil in two prominent universities in Yogyakarta from the 1990s to 2003, Nancy Smith-Hefner’s (2007, 389) study concluded that the contemporary phenomenon of veiling among those women reflected a valiant struggle to meld their individual autonomy and modern education with a strong commitment to Islam.

At this point I deliver a different interpretation from Brenner’s on the growing adoption of veiling among young Javanese Muslim women since the 1980s. While for Brenner the adoption of the jilbab in the 1980s signified a path to modernity involving individual transformation from the past to a modern and religious Islamic Java, this phenomenon can also be seen as an expression of identity politics. In my view, the phenomenon is a consequence of Suharto’s strong control over Indonesian women—which springs from his patriarchal Javanese background. Suharto, in fact, styled himself as the “father of development” ( Bapak Pembangunan) and instigated what Julia Suryakusuma (1996, 96) calls “state ibuism”—a gender ideology that expected complete devotion from all Indonesian women as wives and mothers in developing Indonesia. Borrowing from Ratna Saptari (2000b, 19), who used the term “Java-centric” in addressing Sylvia Tiwon’s (2000, 71–73) notion of the centrality of the Javanese ideology of womanhood, the politically active husband (Suharto) and his faithful companion-wife (Tien Suharto) were the bedrock of a stable family as the foundation of a strong state. In line with this, Suharto introduced the new Marriage Law No 1/1974, which promoted monogamy (Blackburn 2004, 130–134) and encouraged the division of labor between husband and wife for all Indonesian families. It is at this stage, I suggest, that the influence of resurgent Islam gave considerable spirit to young Javanese Muslim women to collectively adopt the jilbab as early as the 1980s, as an expression of political resistance against the New Order’s severe policy on political Islam and the construction of defeated women.

This suggestion that the growing adoption of the jilbab among young Javanese Muslim women signifies identity politics is strengthened by the fact that the women’s actions were initially opposed by the New Order regime. For example, in Jakarta, under the support of the Indonesian Islamic Students’ Association (Pelajar Islam Indonesia), girls began to wear the jilbab in school although school principals opposed it (Alwi and Fifrida 2002, 30). In response to the growing adoption of the jilbab among high school students, the Director-General for Elementary and Tertiary Education ( Direktur Jenderal Pendidikan Dasar dan Menengah) issued the Letter of Instruction ( Surat Keputusan, SK) No. 052/C/Kep/D.82, which ruled on a compulsory national uniform for all school students ( ibid. ). Following this, various jilbab confrontations occurred—not only in high schools in Jakarta, Bandung, Bogor, and Surakarta, but also in Sulawesi and Bengkulu—from 1981 to 1989 ( ibid. , 28–49). Throughout the year, local and national levels of the Indonesian Council of Ulema (Majelis Ulama Indonesia, or MUI), the Indonesian Council for Islamic Propagation (Dewan Dakwah Islam Indonesia), various religious leaders, and lawyers supported the wearing of the jilbab in schools, while the Indonesian Department of Education opposed it. In the aftermath of mounting press coverage on jilbab confrontations in late 1990, the Director-General for Elementary and Tertiary Education issued SK No. 100/C/Kep/D/ 1991, which permitted individuals to wear special uniforms according to their faith ( ibid. , 74). Nevertheless, the series of confrontations indicates the New Order’s anxiety over the growing adoption of the jilbab among young Javanese Muslim students after the 1980s. I suggest the New Order’s anxiety was based on the perception that the phenomenon could potentially endanger the domination of the New Order’s narrative and gender ideology of politically defeated women, and its general policy to suppress political Islam.

In examining the more recent context, we shall differentiate the above phenomenon with the current trend of jilbab adoption among young Indonesian women post-New Order, which, according to Rachmah Ida, has become part of contemporary—indeed stylish—fashion and has little association with the conservatism of the 1980s (Rachmah 2008, 63–65). In understanding that the growing adoption of the jilbab after the New Order is not an expression of political interest as a form of silent resistance to the regime, wearing the jilbab reflects a different meaning in the context of popular democracy.

Engaging Islam and Playing Identity Politics

Since 1998, Indonesia has undergone a process of democratization signified by structural changes to political systems such as the election system, the introduction of the decentralization policy, and a vibrant atmosphere of civil society. One interesting development has been the rising awareness and attention among female Muslim activists and intellectuals with regard to feminism and gender equality in Islam. One leading Muslim feminist—Siti Musdah Mulia, a researcher at the Indonesian Department of Religious Affairs—has criticized the 1974 Marriage Law and the Compilation of Islamic Law (Kompilasi Hukum Islam, or KHI)33) since 2004, urging that it be reformed as it no longer meets the spirit of gender equality and violates human rights (Siti 2007, 131–149). In October 2004 Mulia and her friends in the Working Group for Gender Mainstreaming at the Department of Religious Affairs launched the Counter Legal Draft (CLD) to the KHI, which proposed a more equal relationship between husband and wife (Marzuki 2008, 2–4). There were positive and negative responses to the CLD ( ibid. , 13–17).34) The controversy ended with the Indonesian Ministry of Religious Affairs officially banning the CLD in February 2005 ( ibid. , 19), which was followed by a fatwa—or religious decree—from the MUI on July 29, 2005 stating that pluralism, liberalism, and secularism, as manifested in the CLD, were contradictory to Islamic teachings and thus Muslims were forbidden ( haram) to follow such ideas ( Kompas Cyber Media, July 30, 2005).

In the meantime, the debate over women’s leadership hit the ground running when Megawati Sukarnoputri announced her nomination as a female presidential candidate in the first General Election of the democratic era in 1999. Islamic scholars began to look for possible justification for a female presidential candidate. It was the Congress of Indonesian Muslims (November 3–7, 1998) that recommended that the MUI publish a fatwa on female leadership, “for temporary women are not allowed to be president” (Sinta 2000, 16). In response to the growing interest over female political leadership, Muhammadiyah and NU both felt the need to address the issue. Since the 1970s Muhammadiyah has been concerned with female leadership ( Suara Muhammadiyah 1978), which it continued to propagate throughout the 1990s, in the 44th Muhammadiyah Congress in Jakarta in 2000, and in the 45th Muhammadiyah Congress in Malang in July 2005 ( Jawa Pos, July 2, 2005). Muhammadiyah generally supported female leadership in any position in society as long as it was endorsed by Adabul Mar’ah Fil Islam (Pious Women in Islam), an influential book published by Muhammadiyah’s Majlis Tarjih in 1977 (Majilis Tarjih Pimpinan Pusat Muhammadiyah n.d., 56–57). In NU, attention to women’s leadership came quite late, compared to Muhammadiyah. The NU National Meeting in Lombok (1997) issued a decision on NU’s standpoint titled “The Scholars’ Opinion on a Female President ( Pendapat Alim Ulama tentang Presiden Wanita) No. 004/MN-NU/11/1997.” It stated NU’s support for female roles in social and cultural transformation in the era of globalization (PBNU 1997).

Muslim women in contemporary Java have been surrounded by this progressive Islamic discourse and efforts to support female leadership in politics since 1998. Under such sociopolitical change, it is not surprising to see the current trend whereby Javanese Muslim women take a stand in local politics. Here, it is apparent that the force com pelling Javanese Muslim women to play a greater role in identity politics grew out of the new political context of progressive Islam and the introduction of direct local head elections in 2005. Today, the percentage of female politicians winning (regent/vice regent/mayor/vice mayor/governor) local elections on the island of Java (West Java, Central Java, and East Java), all of whom are Muslim, is higher (11 women, or 9.91 per cent, in 111 elections) than the percentage of female politicians elected outside of Java (15 pairs or 4.22 per cent in 355 elections) between 2005 and 2008 (Indonesia, Ministry of Home Affairs 2009). Five of the 11 female Muslim leaders who hold key positions as regent are Javanese women from Central and East Java: Rustriningsih, Regent of Kebumen (2000–05, 2005–10) and currently vice governor of Central Java (2008–13); Rina Iriani, Regent of Karanganyar (2002–07, 2008–13); Haeny Relawati Rini Widyastuti, Regent of Tuban (2000–05, 2006–11); Ratna Ani Lestari, Regent of Banyuwangi (2005–10); and Siti Qomariyah, Regent of Pekalongan (2006–11). Although their social backgrounds vary across the classes of abangan (Rustriningsih and Ratna Ani Lestari), santri (Siti Qomariyah), and priyayi (Haeny Relawati Rini Widyastuti and Rina Iriani), all wear the veil, as shown above.35)

|

|

|

|

||

Photo 4 Rustriningsih, Ratna Ani Lestari, Siti Qomariyah, (above); Rina Iriani, Haeny Relawati Rini Widyastuti (below)

Source: Rustriningsih, Ratna Ani Lestari, Siti Qomariyah, photos courtesy Kurniawati Hastuti Dewi.

Rina Iriani, http://www.google.co.jp/imglanding? (December 23, 2008)

Haeny Relawati Rini Widyastuti, http://www.tokohindonesia.com/ensiklopedi/h/haeny-relawati-rw/idex.shtml

. (December 23, 2008)

While the women’s reasons for wearing the veil are sure to vary, we should not ignore the importance of an Islamic identity among Javanese Muslim women in local politics. To be sure, the identity of Javanese Muslim women as exemplified by the veil was not created overnight. Rather, it is a result of the intersection between Javanese women and Islam that began with the Islamization of Java, as I have illustrated throughout this paper. As the reason and meaning behind wearing the veil varies depending on the socio-historical context, perhaps now in contemporary Java wearing the veil is less a signifier of piety for female Javanese Muslim political leaders. Rather, it seems to be a political commodity and part of the code of conduct of these candidates to win the hearts of the predominantly Islamic-based voters of Nahdlatul Ulama, the dominant religious orientation in Java. This is not, however, to deny the fact that some Javanese Muslim women who wear the veil are indeed pious devotees of Islam.

And yet, the rise of Javanese Muslim female leaders in local politics has certainly been underpinned by strong Islamic legitimacy. According to my interviews with Rustriningsih, Siti Qomariyah, and Ratna Ani Lestari, they found minor religious opposition to female leadership as regents ( bupati), and when there was any, it was mainly underpinned by political interests.36) Further interviews with, and observation of, prominent NU kyai in Kebumen, Pekalongan, and Banyuwangi, where the three female leaders were victorious, generally found no strong Islamic foundation on which to oppose females occupying leadership positions as regents ( bupati) or governors ( gubernur ), because neither is the highest position in the state, as is the president.37) Therefore, in the fourth phase of the identity formation of Javanese Muslim women, Islam has provided a strong basis for them to be political leaders to meet the challenge of the direct local head elections since 2005.

Conclusion

In this paper I have examined identity formation and the critical phase that saw a change from the culture-based Javanese female identity (the Javanese woman) to a religiocultural-based identity (the Javanese Muslim woman) in line with the various sociocultural contexts over the centuries.

I shed light on the consequences of “syncretic” Islam, especially among Javanese noblewomen from the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries, during which Islam was perceived as a hampering rather than a liberating force. And yet, the intersection with Islam among Javanese noblewomen and ordinary women intensified in the early twen tieth century following the rise of the Islamic reformist movement and national consciousness. Since then, both Javanese noble and ordinary women gained a better understanding of Islamic knowledge through religious learning that was combined with various ideas about progress, and also largely through several publications, which helped them change their stance from relatively passive objects to active subjects in the learning, criticizing, and implementation of divine Islamic messages. Through the active engagement of Javanese women with Islamic texts, which was seen as a lens for viewing social conditions, we can observe the pivotal role of Islam as a new ideology in Java that lent considerable spirit and a means to these women to reach a point of awareness that has enabled them to act as agents of change in their particular cultural setting. Thus, since the early twentieth century, Islam has helped liberate Javanese women from the cultural constraints of Javanese adat, the perception of them as defeated women, the practice of pingitan, and child marriage, even though polygamy remains a contentious battleground.

This growing religio-cultural consciousness has produced competing discourses among various Islamic groups or elite nationalists, both men and women, that are helping forge the emerging identity of Javanese Muslim women. In addition to these contestations is the practice of wearing the kudung, which was gradually adopted across social and geographical landscapes from the 1920s to the 1960s, and which I believe signified the changing identity of Javanese Muslim women. During this stage, I believe Javanese Muslim women wore the kudung to reveal their desire to remain distinct—not only from the European progress of the early twentieth century, but also from non-pious Javanese Muslim women and other non-Islamic Javanese women.

The New Order regime gave a rather different meaning to Javanese women’s intersection with Islam. In my view, the adoption of the jilbab since the 1980s among youngergeneration Javanese Muslim women has a distinct meaning that goes well beyond piety per se. Instead, it could be interpreted as an expression of identity politics against Suharto’s severe policy toward political Islam and the Java-centric social construction of defeated womanhood. In this case Islam as a political ideology, and the resurgence of Islam since the 1970s, provided women with the spirit and means to reveal their political existence.

Of course, the individual reasons for female Javanese Muslim politicians adopting the kudung in the lead-up to direct local head elections from 2005 onward warrant deeper investigation. That these women adopt the kudung regardless of their social background as they go about their political endeavors indicates a possible “manipulation of Islamic piousness” to win voters’ hearts and minds in a popular democracy. Perhaps even more important, these findings point to the current relationship between Javanese Muslim women and Islam. This paper shows that Islam as a belief now provides a strong religious foundation for Javanese Muslim women to be local political leaders following the introduction of direct local head elections since 2005. In doing so, Javanese Muslim women are actually expanding their expectations and stretching the boundaries of their identity in contemporary Java in a way that was not possible before the collapse of the New Order.

Acknowledgements

I greatly appreciate the support, comments, and advice of my supervisors, Associate Professor Okamoto Masaaki, Professor Hayami Yoko, and Associate Professor Caroline S. Hau, as well as Professor Shimizu Hiromu in assessing and improving of this paper. My deepest thanks go also to the two anonymous referees for their critical and valuable comments that elevated this paper to its current state. In no way, however, are they responsible for the opinions and data contained within it.

References

Adams, Gerald R.; and Marshall, Sheila K. 1996. A Developmental Social Psychology of Identity: Understanding the Person-in-Context. Journal of Adolescence 19: 429–442.

Ahmad Adabi Darban. 2000. Sejarah Kauman: Menguak Identitas Kampung Muhammadiyah [History of Kauman: Revealing the identity of Muhammadiyah’s ward]. Yogyakarta: Tarawang.

Alfian. 1969. Islamic Modernism in Indonesian Politics: The Muhammadijah Movement during the Dutch Colonial Period (1912–1942). PhD thesis, University of Wisconsin.

Alwi Alatas; and Fifrida Desliyanti. 2002. Revolusi Jilbab: Kasus Pelarangan Jilbab di SMA Negeri se-Jabotabek 1982–1991 [The Jilbab revolution: The case of Jilbab’s restriction in public senior high school in Jabotabek 1982–1991]. Jakarta: Al-I’tishom Cahaya Umat.

Amien Rais. 1998. Tauhid Sosial: Formula Menggempur Kesenjangan [Social Tauhid: Formula to counter disparity] . Bandung: Mizan.

―. 1995. Moralitas Politik Muhammadiyah [The morality of Muhammadiyah’s politics]. Yogyakarta: Dinamika.

Andaya, Barbara Watson. 2000. Delineating Female Space: Seclusion and the State in Pre-Modern Island Southeast Asia. In Other Pasts: Women, Gender and History in Early Modern Southeast Asia, edited by Barbara Watson Andaya. Honolulu: Center for Southeast Asian Studies.

Asm Sdm. 1939. Madjoe Teroes [Ever onward]. Islam Raja 9 (July 20).

Beatty, Andrew. 1999. Varieties of Javanese Religion: An Anthropological Account. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bestuur Poetri Mardika [Board of Putri Mardika]. 1917. Verslag P. M. Dalam Boelan October t/m December 1916 [Report of P. M. in October/December 1916]. Poetri Mardika 2 (February).

Blackburn, Susan. 2008. Indonesian Women and Political Islam. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 39(1): 83–105.

―. 2004. Women and State in Modern Indonesia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

―. 2002. Indonesian Islamic Women Enter the Political Arena. Jurnal Kulturr II (2): 21–45.

Brenner, Suzanne. 1996. Reconstructing Self and Society: Javanese Muslim Women and “the Veil.” American Ethnologistt 23(4): 673–697.

Brenner, Suzanne A. 1995. Why Women Rule the Roost: Rethinking Javanese Ideologies of Gender and Self-Control. In Bewitching Women, Pious Men: Gender and Body Politics in Southeast Asia, edited by Aihwa Ong and Michael G. Peletz. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press.

Carey, Peter; and Houben, Vincent. 1987. Spirited Srikandhis and Sly Sumbadras: The Social, Political and Economic Role of Women at the Central Javanese Courts in the 18th and Early 19th Centuries. In Indonesian Women in Focus: Past and Present Notions, edited by Elsbeth Locher-Scholten and Anke Niehof. Dordrecht: Foris Publications.

Cote, James E. 1996. Sociological Perspectives on Identity Formation: The Culture-Identity Link and Identity Capital. Journal of Adolescence 19: 417–428.

Cote, James E.; and Levine, Charles. 1987. A Formulation of Erikson’s Theory of Ego Identity Formation. Developmental Review 7: 273–325.

Cote, Joost. 2005. Introduction. In On Feminism and Nationalism: Kartini’s Letters to Stella Zeehandelaar 1899–1903, Monash Paper on Southeast Asia no. 6. Clayton: Monash Asia Institute.

Dewi Sekartadji. 1932a. Djawab Kami Dewi Sekartadji, Kapada Bintang Islam [My answer Dewi Sekartadji to Bintang Islam]. Isteri 5 (September).

―. 1932b. Alasan Kita Kaoem Iboe [Rationale of our mother]. Isteri (June).

Elmhirst, Rebecca. 2000. A Javanese Diaspora? Gender and Identity Politics in Indonesia’s Transmigration Resettlement Program. Women’s Studies International Forum 23(4): 487–500.

Emmerson, Donald K. 1978. The Bureaucracy in Political Context: Weakness in Strength. In Political Power and Communications in Indonesia, edited by Karl D. Jackson and Lucian W. Pye. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press.

Erikson, Erik H. 1950. Childhood and Society. New York and London: W. W. Norton & Company.

Feillard, Andree. 1999. The Veil and Polygamy: Current Debates on Women and Islam in Indonesia. Moussons 99: 5–27.

Florida, Nancy K. 1996. Sex Wars: Writing Gender Relations in Nineteenth-Century Java. In Fantasizing the Feminine in Indonesia, edited by Laurie J. Sears. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Geertz, Clifford. 1963. Peddlers and Princess: Social Change and Economic Modernization in Two Indonesian Towns. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

―. 1960. The Religion of Java. New York: Free Press.

Geertz, Hildred. 1985. Letters of a Javanese Princess: Raden Adjeng Kartini. Lanham, New York, and London: University Press of America and Asia Society.

―. 1961. The Javanese Family: A Study of Kinship and Socialization. New York: Free Press of Glencoe Inc.

G Mudjanto. 1986. The Concept of Power in Javanese Culture. Yogyakarta: Gadjah Mada University Press.

Hadji Agus Salim. 1978. The Veiling and Isolation of Women. In Regents, Reformers, and Revolutionaries: Indonesian Voices of Colonial Days: Selected Historical Readings 1899–1949, edited and translated by Greta O. Wilson. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Hatley, Barbara. 1990. Theatrical Imagery and Gender Ideology in Java. In Power and Difference: Gender in Island Southeast Asia, edited by Jane Monnig Atkinson and Shelly Errington. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Hefner, Robert. W. 2000. Civil Islam: Islam dan Demokratisasi di Indonesia [Civil Islam: Islam and democratization in Indonesia] , translated by Ahmad Baso. Yogyakarta: LKIS.

―. 1987. Islamizing Java? Religion and Politics in Rural East Java. Journal of Asian Studies 46(3): 533–554.

Hull, Valerie J. 1976. Women in Java’s Rural Middle Class: Progress or Regress? Working Paper Series no. 3. Yogyakarta: Lembaga Kependudukan, Universitas Gadjah Mada.

Indonesia, Biro Pusat Statistik [Central Bureau of Statistic]. 1995. Indikator Sosial Wanita Indonesia [Social indicator of Indonesian women] . Jakarta: Biro Pusat Statistik.

―. 1989. Indikator Sosial Wanita Indonesia [Social indicator of Indonesian women]. Jakarta: Biro Pusat Statistik.

Indonesia, Department of Information. 1968. The Indonesian Women’s Movement: A Chronological Survey of the Women’s Movement in Indonesia. Jakarta: Department of Information, Republic of Indonesia.

Indonesia, Ministry of Home Affairs. 2009. Daftar Kepala Daerah dan Wakil Kepala Daerah Yang Telah Diterbitkan Keputusannya Presiden Republik Indonesia Hasil Pemilihan Kepala Daerah Secara Langsung Tahun 2005, 2006, 2007, dan Tahun 2008 [List of heads and vice-heads of local government which had been approved by president of Republic of Indonesia as a result of direct local head election in 2005, 2006, 2007, and 2008]. February 13.

Indonesia, Ministry of Social Affairs. 1954. Towards Social Welfare in Indonesia. Jakarta: Ministry of Social Affairs, Republic of Indonesia.

Indonesia, Tim Penggerak PKK Pusat [Central Board of PKK]. n.d. Sejarah Singkat Gerakan PKK [Short history of PKK movement] . Jakarta: Tim Penggerak PKK Pusat.

Jaggar, Alison M.; and Paula Rothenberg Struhl. 1978. Alternative Feminist Frameworks: The Roots of Oppression. In Feminist Frameworks: Alternative Theoretical Accounts of the Relations between Women and Men, edited by Alison M. Jaggar and Paula Rothenberg Struhl. New York: McGrawHill.

Jay, Robert R. 1969. Javanese Villagers: Social Relations in Rural Modjokuto. Cambridge and London: MIT Press.

―. 1963. Religion and Politics in Rural Central Java, Cultural Report Series. New Haven: Yale University, Southeast Asia Studies.

Julia I Suryakusuma. 1996. The State and Sexuality in New Order Indonesia. In Fantasizing the Feminine in Indonesia, edited by Laurie J. Sears. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Kahn, Joel S. 1978. Ideology and Social Structure in Indonesia. Comparative Studies in Society and History 20(1): 102–122.

Kartinah. 1955. Kartini Penundjuk Djalan Kahidupan Baru [Kartini guide to new life]. Harian Rakjat. April 21.

Keeler, Ward. 1990. Speaking Gender in Java. In Power and Difference: Gender in Island Southeast Asia, edited by Jane Monnig Atkinson and Shelly Errington. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

K. H Dewantoro. 1938. Kedoedoekan Perempoean [The position of women]. Keloearga 9 (September).

Kijahi Achmad Arsjad. 1917. Voorstel Akan Mengoerangkan Banjaknya Orang Jang Berbini Lebih dari Seorang, Sehingga Lambat Laoen Bisa Hilanglah Adanja Bigami atau Polygamie [Proposal to reduce people who have more than one wives, so that gradually bigamy and polygamy will disappear]. Poetri Mardika 4 (April).

Koentjaraningrat. 1985. Javanese Culture. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

―. 1980. Javanese Terms for God and Supernatural Beings and the Idea of Power. In Men, Meaning and History: Essays in Honour of H. G. Schulte Nordholt, edited by R. Schefold, J. W. Schoorl, and J. Tennekes. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

―. 1957. A Preliminary Description of the Javanese Kinship System, Cultural Report Series. New Haven: Yale University, Southeast Asia Studies.

Koentjaraningrat, review [untitled]. 1962. Reviewed work: The Javanese Family: A Study of Kinship and Socialization, by Hildred Geertz. American Anthropologist New Series 64(4): 872–874.

Kongres Wanita Indonesia [Indonesian Women Congress]. 1978. Sejarah Setengah Abad Pergerakan Wanita Indonesia [Half century history of Indonesian women movement] . Jakarta: Balai Pustaka.

Kumar, Ann. 2000. Imagining Women in Javanese Religion: Goddess, Ascetes, Queens, Consort, Wives. In Other Pasts: Women, Gender and History in Early Modern Southeast Asia, edited by Barbara Watson Andaya. Manoa: University of Hawai‘i, Center for Southeast Asian Studies.

Kurniawati Hastuti Dewi. 2008. Perspective versus Practices: Women’s Leadership in Muhammadiyah. SOJOURN: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 23 (October): 161–185.

―. 2007. Women’s Leadership in Muhammadiyah: ‘Aisyiyah’s Struggle for Equal Power Relations. Master’s thesis, Australian National University.

Leo Suryadinata; Evi Nurvidya Arifin; and Aris Ananta. 2003. Penduduk Indonesia: Etnis dan Agama dalam Era Perubahan Politik [Indonesian population: Ethnicity and religion in political transition era], translated by Lilis Heri Mis Cicih. Jakarta: Pustaka LP3ES.

Liddle, R. William; and Mujani, Saiful. 2007. Leadership, Party, and Religion: Explaining Voting Behavior in Indonesia. Comparative Political Studies 40(7): 832–857.

Lin Fathima. 1952. Haruskah Wanita itu Berkain dan Berkebaja [Shall women wear long skirt and kebaya]. Suara ‘Aisjijah 8 (June).

Locher-Scholten, Elsbeth. 2000. Colonial Ambivalencies: European Attitudes towards the Javanese Household (1900–1942). In Women and Households in Indonesia: Cultural Notions and Social Practices, edited by Juliette Koning, Marleen Nolten, Janet Rodenburg, and Ratna Saptari. Richmond: Curzon Press.

Lont, Hotze. 2000. More Money, More Autonomy? Women and Credit in a Javanese Urban Community. Indonesia 70 (October): 83–100.

Majilis Tarjih Pimpinan Pusat Muhammadiyah [Committee of Tarjih Central Board of Muhammadiyah]. n.d. Adabul Mar’ah Fil Islam [Pious women in Islam]. Yogyakarta: Majelis Tarjih Pimpinan Pusat Muhammadiyah.

Marcia, James E. 1980. Identity in Adolescence. In Handbook of Adolescent Psychology, edited by Joseph Adelson. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Maria Ulfah Santoso. 1940. Nasibnja Perempoean Indonesia (via Berita BPPIP) [Situation of Indonesian women]. Keoetamaan Isteri 11 (November).

Marzuki Wahid. 2008. Pembaruan Hukum Keluarga Islam di Indonesia Paska Orde Baru: Studi Politik Hukum atas Counter Legal Draftt Kompilasi Hukum Islam [Renewal of Islamic family law in post New Order Indonesia: Legal-political study on counter legal draft of the compilation of Islamic Law]. Paper presented at the 4th Annual Islamic Studies Postgraduate Conference, Melbourne, 17–18 November 2008.

M. A. S Hikam. 1999. Wacana Intelektualisme tentang Civil Society di Indonesia [Intellectual discourse on civil society in Indoenesia]. Jurnal Pemikiran Islam Paramadina 1(2): 40.

M. Bambang Pranowo. 2005. From Aliran to Liberal Islam: Remapping Indonesian Islam. In A Portrait of Contemporary Indonesian Islam, edited by Chaider S. Bamualim. Jakarta: Pusat Bahasa dan Budaya IAIN Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta and Konrad Adenaur Stiftung.

Moeliono, Moira M. M.; and Limberg, Godwin. 2004. Fission and Fusion: Decentralization, Land Tenure and Identity in Indonesia. http://www.cifor.cgiar.or/ (February 8, 2009)

M. Rusli Karim. 1992. Islam dan Konflik Politik Era Orde Baru [Islam and political conflict in the New Order era] . Yogyakarta: PT. Media Widya Mandala.

Multatuli (Eduard Douwes Dekker). 1978. The Sermon of the Reverend Blatherer and the Story of Saijah and Adinda. In Insulinde: Selected Translations from Dutch Writers of Three Centuries on the Indonesian Archipelago, edited by Cornelia Niekus Moore, pp. 24–54. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Nasaruddin Umar. 1999. Kodrat Perempuan dalam Islam [Women Kodrat in Islam]. Jakarta Pusat: Lembaga Kajian Agama & Jender, Solidaritas Perempuan, and Asia Foundation.

Nieuwenhuis, Madelon, D. 1987. Ibuism and Priyayization: Path to Power? In Indonesian Women in Focus: Past and Present Notions, edited by Elsbeth Locher-Scholten and Anke Niehof. Dordrecht: Foris Publications.

Nurcholish Madjid. 1992. Islam, Doktrin dan Peradaban: Sebuah Telaah Kritis Tentang Masalah Keimanan, Kemanusiaan, dan Kemodernan [Islam, doctrine and civilization: A critical analysis on faith, humanity, and modernism] . Jakarta: Yayasan Wakaf Paramadina.

Patrem. 1932. Pendidikan Perempoean Oentoek Berdjajar dengan Kaoem Lelaki Dalam Pergerakan Javanese Women and Islam [Education for women to be equal with men in the movement]. Isteri 3 (July).

Pengurus Besar Nahdlatul Ulama (PBNU) [Central Board of Nahdlatul Ulama]. 1997. Pendapat Alim Ulama Tentang Presiden Wanita: Keputusan Musyawarah Nasional Alim Ulama No: 004/MN-NU/ 11/1997 (Tanggal 16–20 Rajab 1418 H/17–21 Nopember 1997 di Pondok Pesantren Qomarul Huda Desa Bagu, Pringgarat Lombok Tengah Nusa Tenggara Barat) Tentang: “Kedudukan Wanita Dalam Islam” [Opinion of Ulama on female president: Decision of national meeting of Ulama No. 004/MN-NU/11/1997 (On 16–20 Rajab 1418 H/17–21 November 1997 in Pesantren Qomarul Huda, Bagu village, Pringgarat, Central Lombok, West Nusa Tenggara) on: “Position of women in Islam”]. Jakarta: Kantor Sekretariat PBNU.

Phinney, Jean S. 2000. Identity Formation across Cultures: The Interaction of Personal, Societal, and Historical Change. Human Development 43(1): 27–31.

Pimpinan Pusat ‘Aisyiyah [Central Board of ‘Aisyiyah]. n.d. Sejarah Pertumbuhan dan Perkembangan ‘Aisyiyah [History of growth and development of ‘Aisyiyah] . Yogyakarta: Pimpinan Pusat ‘Aisyiyah.

Pimpinan Pusat Muhammadiyah Majelis ‘Aisyiyah [Assembly of ‘Aisyiyah in Central Board of Muhammadiyah]. n.d. Tuntunan Menjadi Isteri Islam yang Berarti [Guidance for becoming a meaningful Islamic wife] . Yogyakarta: PP Muhammadiyah Majelis ‘Aisyiyah.

Pr. 1915. Adat Jang haroes Kita Linjapkan [Customs which we have to eradicate]. Poetri Mardika 4 (July).

Rachmah Ida. 2008. Muslim Women and Contemporary Veiling in Indonesia. In Indonesian Islam in a New Era: How Women Negotiate Their Muslim Identities, edited by Susan Blackburn, Bianca J. Smith, and Siti Syamsiyatun. Melbourne: Monash University Press.

Ratna Saptari. 2000a. Networks of Reproduction among Cigarette Factory Women in East Java. In Women and Households in Indonesia: Cultural Notions and Social Practices, edited by Juliette Koning, Marleen Nolten, Janet Rodenburg, and Ratna Saptari. Richmond: Curzon Press.

―. 2000b. Women, Family and Household: Tensions in Culture and Practice. In Women and Households in Indonesia: Cultural Notions and Social Practices, edited by Juliette Koning, Marleen Nolten, Janet Rodenburg, and Ratna Saptari. Richmond: Curzon Press.

Reid, Anthony. 2000. Charting the Shape of Early Modern Southeast Asia. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Ricklefs, M. C. 2007. Polarising Javanese Society: Islamic and Other Visions (c. 1830–1930). Singapore: NUS Press.

―. 2001. History of Modern Indonesia since c.1200, 3rd ed. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Rit Kamariah. 1931–32. Soerat-menjoerat [Correspondences]. Isteri 8-9-10 (December-January-February).

Robinson, Kathryn. 2009. Gender, Islam and Democracy in Indonesia. Abingdon: Routledge.

R Soepomo. 1931. Deradjat Perempoean Indonesia dalam Adatrecht [Status of Indonesian women in customary law]. Isteri 11 (March).

Sarwo. 1940. Tersingkap tabir. [Revealing tabir]. Islam Raja 11 (August 15).

Schachter, Elli P. 2005. Context and Identity Formation: A Theoretical Analysis and a Case Study. Journal of Adolescent Research 20(3): 375–395.

Schwartz, Seth J. 2001. The Evolution of Eriksonian and Neo-Eriksonian Identity Theory and Research: A Review and Integration. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research 1(1): 7–58.

Sd. 1915a. Perobahan Alam Perampoean (Sambungan P. M. no. 5) [Changes of women’s nature (continuation of P.M. no. 5)]. Poetri Mardika 6 (September).

―. 1915b. Perobahan Alam Perempoewan [Changes of women’s nature]. Poetri Mardika 5 (August).

Shamsul A. B. 1996. Debating about Identity in Malaysia: A Discourse Analysis. Southeast Asian Studies 34(3): 476–498.

Sinta Nuriyah Abdurrahman Wahid. 2000. Merumuskan Kembali Agenda Perjuangan Perempuan Dalam Konteks Perubahan Sosial Budaya Islam di Indonesia [Reformulation agenda of women’s struggle in the context of Islamic socio-cultural changes in Indonesia]. In Jurnal Pemikiran Islam Tentang Pemberdayaan Perempuan [Islamic journal on empowerment of women] , edited by Mursyidah Thahir. Jakarta: PP Muslimat NU and Logos.

Siti Musdah Mulia. 2007. Islam dan Inspirasi Kesetaraan Genderr [Islam and inspiration of gender equality] . Yogyakarta: Kibar Press.

S Koesoemo. 1917a. Perampoean Boemipoetra [Women of Bumiputra]. Poetri Mardika 4 (April).

―. 1917b. Perampoean Boemipoetra Dibijtarakan [Women of Bumiputra being discussed]. Poetri Mardika 3 (March).

Smith-Hefner, Nancy J. 2007. Javanese Women and the Veil in Post-Soeharto Indonesia. Journal of Asian Studies 66(2): 389–420.

Soeminar Hastoeti. 1940. Mahromah. Islam Raja 20 (November 25).

Sriwijat. 1926. Kemadjoean Perempoean Islam [Progress of Islamic women]. Taman Moeslimah Isteri Soesila 4 (April 20).

Stoler, Ann. 1977. Changing Modes of Production: Class Structure and Female Autonomy in Rural Java. Signs 3 (1): 76–89.

Sukanti Suryochondro. 1984. Potret Pergerakan Wanita di Indonesia [Portrait of women movement in Indonesia] . Jakarta: CV. Rajawali.

Sullivan, Norma. 1994. Masters and Managers: A Study of Gender Relations in Urban Java. St Leonards: Allen & Unwin.

Suratmin. 1990. Nyai Ahmad Dahlan Pahlawan Nasional: Amal Usaha dan Perjuangannya [Nyai Ahmad Dahlan national hero: Her good deeds and struggle] . Yogyakarta: PT. Bayu Indra Grafika.

Thomson Zainu’ddin, Alisa G. 1980. Kartini, Her Life, Work and Influence. In Kartini Centenary Indonesian Women Then and Now, edited by Alisa Thomson Zainu’ddin et al. Cheltenham: Standard Commercial Printers.

Tiwon, Sylvia. 2000. Reconstructing Boundaries and Beyond. In Women and Households in Indonesia: Cultural Notions and Social Practices, edited by Juliette Koning, Marleen Nolten, Janet Rodenburg, and Ratna Saptari. Richmond: Curzon Press.

Tj. T vis Si De. 1940. Isteri Sedar Tjoekoep Oemoernja 10 Tahoen [Ten years of Isteri Sedar]. Keoetamaan Isteri 6 (June).

Vreede-De Stuers, Cora. 1960. The Indonesian Woman: Struggles and Achievements. ‘s-Gravenhage: Mouton & Co.

Weix, G. G. 2000. Hidden Managers at Home: Elite Javanese Women Running New Order Family Firms. In Women and Households in Indonesia: Cultural Notions and Social Practices, edited by Juliette Koning, Marleen Nolten, Janet Rodenburg, and Ratna Saptari. Richmond: Curzon Press.

White, Sally. 2004. Reformist Islam, Gender and Marriage in Late Colonial Dutch East Indies, 1900–1942. PhD thesis, Australian National University.

White, Sally; and Maria Ulfah Anshor. 2008. Islam and Gender in Contemporary Indonesia: Public Discourses on Duties, Rights and Morality. In Expressing Islam: Religious Life and Politics in Indonesia, edited by Greg Fealy and Sally White. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Woodward, Mark R. 1989. Islam in Java: Normative Piety and Mysticism in the Sultanate of Yogyakarta. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

―. 1988. The “Slametan”: Textual Knowledge and Ritual Performance in Central Javanese Islam. History of Religions 28(1): 54–89.