Contents>> Vol. 4, No. 3

Blossoming Dahlia: Chinese Women Novelists in Colonial Indonesia

Elizabeth Chandra*

*Department of Politics, Keio University, 2-15-45 Mita, Minato-ku, Tokyo 108-8345, Japan; Socio-Cultural Research Institute, Ryukoku University, 1-5 Yokotani, Seta Oe-cho, Otsu, Shiga 520-2194, Japan

e-mail: ec54[at]cornell.edu

DOI: doi.org/10.20495/seas.4.3_533

In the early decades of the twentieth century in colonial Indonesia, one witnessed the proliferation of novels in which women were thematized as the femme fatale. These novels were written largely by male novelists as cautionary tales for girls who had a European-style school education and therefore were perceived to be predisposed to violating customary gender norms in the pursuit of personal autonomy. While such masculinist responses to women and material progress have been well studied, women’s views of the social transformation conditioned by modernization and secular education are still insufficiently understood. This essay responds to this scantiness with a survey of texts written by Chinese women novelists who emerged during the third and fourth decades of the twentieth century, drawing attention in particular to the ways in which these texts differed from those written by their male predecessors. More important, this essay highlights the works by one particular woman novelist, Dahlia, who wrote with an exceptionally distinct female voice and woman-centered viewpoint.

Keywords: Sino-Malay literature, Chinese women, women novelists, Dahlia, Tan Lam Nio, Indonesia

In the history of modern literature in Indonesia, women regularly served as a thematic subject of representation. Scores of early twentieth century novels in the then Dutch East Indies tell the story of a young woman protagonist who, influenced by Western education, casts aside tradition and as a consequence meets a tragic end—she is disowned by her parents, forsaken by her lover, shunned by her community, and withers away with remorse. These novels, which place women at the center of their moral, were written largely by male novelists as cautionary tales for girls who had a European-style school education and therefore were perceived to be predisposed to violating customary gender norms in the pursuit of personal autonomy.

While such masculinist responses to women and material progress have been studied (Sidharta 1992; Coppel 2002a; Chandra 2011; Hellwig 2012, 127–150), women’s views of the social transformation conditioned by industrialization and secular education are still insufficiently understood, for the simple reason that very few writers in the early decades of the twentieth century were women. While the literary output by female writers is nowhere near that produced by male writers, Chinese women in the Indies actually published quite a number of texts, which taken together are more than what was produced by women of other ethnic groups in colonial Indonesia. A few scholars have accorded these works the attention they deserve (Salmon 1984; Chan 1995; Hellwig 2012, 151–179), while others have found it convenient to avoid them even in discussions about Indonesian women’s writings of the 1930s (Hatley and Blackburn 2000).

This essay examines female subjectivity in early twentieth century Indonesia by surveying the field of Chinese women writers, whose publishing outlets afforded them a comparatively sizeable production in Malay literature. To twist Sigmund Freud’s famous question, this essay asks “What did Chinese women write?” and proceeds to examine literary texts—especially novels—penned by women. It attempts to see whether there are indeed discernible patterns of themes, motifs, genres, or other creative elements specific to women authors. It discusses, among other things, the curious phenomenon of male authors writing in the feminine voice, and what might have motivated such a claim of feminine authorial subjectivity. Most important, this essay spotlights one female novelist by the pen name Dahlia, who was arguably the most promising female author of her generation as she wrote with exceptionally distinct female agency.

Identifying Women Authors

It has been established that although the most prolific and innovative literary productions in Malay in the first half of the twentieth century came out of the Chinese segment of the Indies population, very few of the writers were women. My own accounting, based on surviving literary publications, estimates no more than 50 Chinese women authors—that is, those attributed with book publications—compared with approximately 800 Chinese male writers from the turn of the twentieth century until the end of the colonial period.1) One can speculate that the Confucian patriarchal bias was holding back education for Chinese girls in the Indies, or that as a migrant group, the Chinese population had a demography that was naturally tilted toward the male population. Census data shows that even in 1930, Chinese males outnumbered their female counterparts 2 to 1.2) This factor, however, can be dismissed as most of the Chinese writers in the Indies were not first generation immigrants but were creolized settlers (peranakan) whose mother tongue was Malay rather than a Chinese dialect.3) Likewise, lack of education as a factor is only partly true, because from early on access to formal education was opened up to both Chinese boys and girls. Since its inception in 1901, the community-subsidized Tiong Hoa Hwee Koan (THHK) schools made rooms for Chinese girls to attend and study alongside boys.4) But while access to formal education was accorded to both sexes at the same time, it was the attitude toward education for girls that eventually factored into the gender imbalance in the field of literature.

The establishment of THHK schools was first and foremost intended for boys, as an investment for their social mobility, whereas for girls education was considered not imperative, even problematic. Even in the early years of the THHK school in Batavia, the first school of its kind, female students were admitted as a temporary solution before a special school exclusively for girls was created (Nio 1940, 17, 60). The girls were taught separately from the boys; and in addition to learning Mandarin, English, and other subjects, they learned practical domestic skills such as sewing, embroidering, and other crafts associated with women.5)

While access to education was open to Chinese girls in the Indies, the prevailing view in the early decades of the twentieth century was that education was not essential for their social mobility. While a boy needed formal education in order to acquire gainful employment, a girl was expected to secure her future by marrying well. Many of those who were fortunate enough to experience a school education in their youth would eventually give it up in their adolescent years, when they were withdrawn from school and began the period of customary seclusion (pingitan) until they were married. The practice and stringency of seclusion varied, from strict prison-like confinement to lax observance—freer association under parental supervision—depending on the parents’ cultural orientation and the family’s social standing. In this essay I refer to as “patriarchal” the complex economic arrangement in which the household, including daughters, is subsumed under the authority of the father as the ultimate proprietor (Engels 2004). In public, this arrangement translates into a social system in which the male figure holds authority over the female sex (Walby 1990; McClintock 1993). Under patriarchy, women serve as objects to be exchanged in order for men to build alliances or gain prestige, ultimately to consolidate the system (Levi-Strauss 1969; Rubin 1975; Irigaray 1985). As we shall see below, it was this patriarchal authority—and specifically its utilitarian approach toward marriage—that was challenged in the early twentieth century when Indies society transitioned to modernity.

Early on, until around the 1910s, parents who sent their daughters to school were counted as progressive, until the practice became commonplace and basic education such as reading and writing skills became a practical necessity even for those who did not expect to work in the formal sector. In the second and third decades of the twentieth century, a progressive (moderen, madjoe) parent would not subject his daughter to pingitan but would let her work in the formal sector outside the home and perhaps even allow her to choose her own marriage partner. This type of parent, however, was rare, and intergenerational clash between old-fashioned (kolot) parents and moderen daughters was a frequent theme in novels written by both male and female authors of these decades.

A parent’s social standing could make a difference in terms of education for girls. Before the advent of THHK schools, families of means could afford to hire private European or Chinese tutors for their children or send them to schools that were generally reserved for Europeans but were open to children of privileged Chinese and native Indies families. Chinese parents of such an elite circle could be expected to have developed a more accepting attitude toward school education for daughters. Liem Titie Nio, one of the earliest Chinese women journalists in the Indies, who edited the women’s column in the weekly Tiong Hoa Wi Sien Po (Chinese Reformist Newspaper)—founded in Bogor in 1906—appears to have come from such a privileged background (Salmon 1981). Another pioneering woman journalist, Lie On Moy, was also well connected: she was married to the prominent writer and publisher Lauw Giok Lan, with whom she collaborated in the publication of the weekly Penghiboer (Entertainer), which first appeared in 1913 (ibid.). Many of their publications do not survive for our examination, but Lauw’s Malay translations of Dutch novels and plays signal the couple’s extensive European education and early exposure to literary works in at least Dutch. One imagines the same case for Tan Tjeng Nio, the author (composer) of highly popular verses, compiled by Intje Ismail in Sair Tiga Sobat Nona Boedjang (Verses of Three Bachelorette Friends), which was published by Albrecht & Co. in 1897 and went to the seventh edition in 1924. The book-length poetry itself is so intriguing and provocative for its tone and subject matter—questioning the merit of marriage for women—that it warrants a separate discussion devoted solely to it.6)

At any rate, the proliferation of secular, Western-style education from the early twentieth century provided the material structure for the eventual emergence of Chinese women novelists in the Indies. Initially formal education created a gulf between generations, giving rise to the new social category of kaoem moeda (the young generation)—educated youth whose worldview was radically different from their parents’ (Shiraishi 1990). Education and exposure to emancipatory ideas accorded the young generation a new subjectivity—one that has been identified as uniquely modern—that is, a newly attained consciousness concerning their place in the formerly rigid social hierarchies. While superficially the qualities of being modern have been associated with a range of novel practices, from attending school to going to the cinema and wearing Western-style outfits, on a deeper, cognitive level, being modern signifies “the ability to achieve an identity as opposed to always being defined by identity given by birth” (Siegel 1997, 93). Exposed to new ideas, the young generation in the Indies challenged existing norms, including received notions of morality, marriage, and the family. While in earlier times marriage was largely an economic transaction between families, for the younger generation, compatibility and romantic love became essentials. School education also fostered divergent views and expectations regarding gender roles, a theme that is central in many novels penned by women authors.

Identifying women writers and resurrecting them from the depths of historical obscurity is not an easy task, but it has been made possible by Claudine Salmon’s influential work Literature in Malay by the Chinese of Indonesia: A Provisional Annotated Bibliography (1981), which to this day remains the most comprehensive reference on Sino-Malay literature. Salmon (1984) herself has done a remarkable review of Chinese women authors, whose works she divides into three broad periods based on their outlook toward women’s emancipation: from the beginning until 1924, from 1925 to 1928, and from 1929 to 1942. While my discussion on women writers does not subscribe to Salmon’s periodization, it relies on her works in identifying especially writers who were not novelists or translators, in other words, those who did not leave behind published books. Countless essays and short stories penned by women writers graced popular Sino-Malay magazines, especially because many novelists were also freelance journalists or launched their writing career in journalism. It will take an extensive collaborative effort to compile and study the materials scattered in various magazines, an endeavor Faye Yik-Wei Chan (1995) has initiated with an examination of two Sino-Malay magazines, the weekly Panorama (1926–31) and the women’s monthly Maandblad Istri (1935–42). Tineke Hellwig (2012, 151–179) retraces Salmon’s review of Chinese women authors, drawing attention to a selection of texts that reflect women’s self-definition. While my discussion covers much of the same territory as Salmon’s and Hellwig’s articles, what each of us finds to be noteworthy and the conclusions we draw vary considerably. In addition, this essay problematizes the question of voice, specifically gendered voice, and to a good extent concentrates on one author, Dahlia.

The most straightforward way to identify the women authors is by name. Names with the feminine qualifier “Nio” can be safely assumed to be women, such as the above-mentioned Tan Tjeng Nio and Liem Titie Nio.7) Others used female honorifics, such as Njonja (Mrs.) The Tiang Ek, Miss Kin, Miss Huang, and Miss I. N. Liem—seemingly the female counterparts of the many “Monsieurs” among pen names used by male writers, such as Monsieur d’Amour, Monsieur Novel, Monsieur Adonis, Monsieur Hsu, and Monsieur Kekasih.

Gender identification becomes trickier when it comes to pseudonyms. The “Njonja” and “Nona” in pen names such as “Njonja Pasar Baroe” and “Nona Glatik” no longer function as female honorifics but as synonyms of married and unmarried women—therefore, “Dame of Pasar Baroe” and “Songbird Girl.” The use of the non-honorific “Nona” in pen names was especially popular early on in the poetry genre. Nona Glatik, Si Nonah Boto (Cute Damsel), Si Nona Boedjang (Maiden Girl), and Si Nona Manis (Charming Damsel) were all authors of poetry books from the turn of the twentieth century and the 1920s. Though Salmon (1984, 152) refers to them as women poets, many of their compositions do not indicate that the texts were written by women. Si Nona Boedjang’s Boekoe Pantoen Karang-karangan (Book of Motley Verses, 1891), for instance, contains a collection of poems commemorating the eruption of Krakatoa and the incident of murder and robbery that took the life of the Resident of Tamboen. The collection also carries social pantoen, the traditional Malay verses, addressed to bachelorettes. In the same year, Si Nonah Boto published Rodja Melati (Jasmine Flower Strings), containing, among others, conventional pantoen of courtship, which likewise call out to an unnamed “girl” (nona). In both cases, the narrator (enunciator) takes the voice of a bachelor and the authors might not be women.

One encounters the same problem with other feminine pen names, such as Boenga Mawar (Rose), Melati-gambir (Jasmine), Venus, Mimi, and Madonna—all of whom appear to be male writers. Flowers and plants were especially popular for noms de plume, including, among women writers, Aster and Dahlia. While Mimi (a.k.a. Lim Kim Lip) and Madonna (a.k.a. Oen Hong Seng) were known to be male writers—their real identities were not concealed—one can only speculate about the others based on the tenor and temperament of their works. The voice in Boenga Mawar’s poems, compiled in Boekoe Pantoen Pengiboer Hati (Book of Verses to Please the Heart, 1902), is also masculine, referring to self interchangeably in the first person narrator “I” (saja) and the third person “baba” (term of address for creolized Chinese men). In another case, Venus wrote original novels as early as in the 1910s, when there did not seem to be Chinese women writing novels in the Indies. In the long introduction to Tjerita Gadis jang Genit, atawa Pengaroenja Oewang (Story of a Coquette, or the Influence of Money, 1921), Venus criticizes parents who use daughters as “bait” to lure wealthy suitors in order for the family to secure a comfortable life. Though seemingly critical of many parents’ materialistic tendency, Venus’s stories do not quite side with women either; in fact, they portray women in a negative light. Poesoet, the titular coquette in Tjerita Gadis jang Genit, endorses her parents’ scheme to get her to marry the son of a Chinese officer, while the family’s materialistic and dishonest dispositions are blamed on the mother. It is highly unlikely that Venus was a woman author.

This phenomenon of male writers assuming feminine pen names is indicative of the significance of gendered voice. Si Nonah Botoh, Si Nona Boedjang, Si Nona Manis, Nona Glatik, Boenga Mawar, Venus, Mimi, and Madonna were all (or likely) pseudonyms of male authors. The opposite case, where female writers took on masculine pseudonyms, has not been discovered among Indies Chinese women novelists, and appears to be uncommon. This pattern distinguished them somewhat from Victorian women novelists, who used pseudonyms to protect their reputation. In a society where the public sphere was still largely a male domain, exposing one’s inner thoughts to the reading public, though clothed as fiction, risked being seen as unseemly, unladylike. The Brontë sisters and Mary Ann Evans (a.k.a. George Eliot) used masculine names in part to avoid personal publicity, and so that their writings would be taken seriously by a reading public that still expected “serious” works to be written by men. The Brontë sisters did not want to reveal their gender because, as Charlotte Brontë explained, “without at that time suspecting that our mode of writing and thinking was not what is called ‘feminine’—we had a vague impression that authoresses are liable to be looked on with prejudice” (Bloom 2008, 8). These novelists foreshadowed J. K. Rowling, author of the best-selling Harry Potter series, who abbreviated her name to avoid being typecast by her gender and shunned by potential boy readers (Kennedy 2013).

What we see among authors in the Indies was rather different. While some women authors concealed their identity by using pseudonyms (e.g., Aster, Dahlia, Mrs. Leader) or abbreviations (Miss Kin, Miss Huang, Miss I. N. Liem), they generally did not conceal their gender. In her short memoir, Tjan Kwan Nio (1992) confesses to having used the pseudonym “Madame H” for what would be her first novel, Satoe Orang Sial (A Hapless Person, 1940), before being coaxed by the publisher into using her real name. While I agree with Salmon (1984) that women authors used pseudonyms to protect their reputation, in my view their gender had become an asset in the literary publishing industry at this time and was one of the reasons why a number of male authors published under feminine pseudonyms.

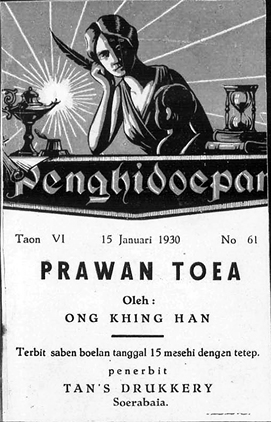

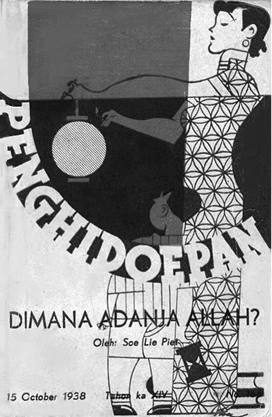

Leafing through popular literary journals like Penghidoepan (Life) and Tjerita Roman (Romance Stories), it does not escape one’s notice that many of the images and illustrations on the cover as well as inside the volumes feature women, often portrayed with “modern” accoutrements. On the covers of Penghidoepan especially, the woman does not gaze directly at the reader. She does not peer at the male reader to elicit masculine gaze, but projects herself in a way that draws non-erotic gaze.8) The woman on the cover usually looks pensive, as if absorbed in her own world. She is contemplative more than inviting; or she invites a different kind of response, one of identification more than erotic attraction. She appears to stand as a mirror, calling out to educated (thus, literate) women who recognize themselves in her image.

The January 1930 issue of Penghidoepan announced an essay contest to explicate the journal’s new cover illustration, which was to be used for one whole year.9) Judging from the journal’s name (“Life”) and contents thus far, the editor notes, readers must already have had some idea about its mission, which was to draw attention to matters essential in life and to present them in the form of stories. The new cover illustration was supposed to reflect this mission. It portrays a woman, a child, a wick lamp, an hourglass, two volumes of science books, an ink bottle, a quill, and a spooled scroll. Each of these items is supposed to relate to life, and readers are invited to submit their interpretations (see Fig. 1).

Until its abrupt termination in February 1942 Penghidoepan would use cover illustrations of the same theme (see Figs. 2 and 3), with small alterations such as an image of a grown man (representing the husband figure) being added to the original young mother and boy toddler. The author Kwee Teng Hin, commenting on the cover illustration in his novel Maen Komedie (Play-Acting, 1933), sees it as a metaphor for the family: the husband figure leads the way by holding up the lamp, while the wife, gripping the quill, chronicles their life story. It is obvious in these illustrations that the woman is the central figure, surrounded by books, a blank scroll, a pen, a child, and sometimes a man. In each of these scenes, it is the woman who does the writing.

It appears that there was a consistent effort to court women readers on the part of popular literary journals and publishers. This was done by featuring stories where the central characters were women (which had been the case even in the 1910s), by drawing attention to issues and challenges women identified as uniquely theirs, such as arranged marriage, formal education, and career—and naturally by featuring women authors whenever possible. In the introduction to Tjan Kwan Nio’s Satoe Orang Sial (1940), the editor of Tjerita Roman expresses delight that the journal has accepted her manuscript “after not publishing any composition by women authors in a while.” The previous work by a woman author it had published was Gadis Goenoeng’s Anak Haram (Bastard Child, 1938),10) while in 1937 it had published Yang Lioe’s Pelita Penghidoepan (Beacon of Life) and Roro Paloepie’s Janie, and in 1936 it had published Rosita’s translation of the Chinese opera See Siang Kie. The journal did not publish any works by women authors in 1934 and 1935, save for the novels by a male author writing under the pen name “Madonna.” Seen in this light, it is not surprising that there were men authors using feminine pseudonyms, but not the reverse. This begs the question: Do women and men write differently?

Extensive inquiries into the nature of the sexes have shown that very little of what constitutes “man” or “woman” is inherently biological and that it has more to do with social constructs (Wittig 1981; Alcoff 1988). We know now that biological sex and social gender are two dissimilar things, and what distinguishes a female from a male author is to a great extent predetermined by social conventions and therefore mere echoes of the structure in and by which they are (en)gendered. Gayle Rubin (1975) has referred to this structure as the “sex/gender system,” which is a set of arrangements by which a society transforms the biological sex into human activity and in this manner reproduces gender conventions. Judith Butler (1990; 1993) goes so far as to equate gender with performativity—one taking on and acting out a set of prescribed attributes and practices associated with a gender. One important and easily identifiable gender attribute is no doubt naming, usually distinguished along the lines of feminine and masculine. Given the literary conventions of the time, when some degree of autobiographical affinity between authors and their writings was often assumed, the use of feminine pen names was no doubt to invoke and accord feminine qualities to one’s writing. The artistic ruse of taking on the feminine façade is a first step in the authorial attempt to speak in the feminine voice and appeal to potential women readers.

In fact, the romance genre itself, being the most common genre featured in popular magazines, seemed to demand women authors, if not the feminine voice.11) It has been noted that women were the subject of literary writings in the Indies from the early part of the twentieth century (Hellwig 1994a; 1994b; Chandra 2011). But while early novels tend to be antagonistic toward women, written in the tradition of the Decadent literary movement (Pierrot 1981; Chandra 2011), from the late 1920s one detects a gradual shift in tone coming from a younger generation of writers who were more exposed to ideas of equality between the sexes. Romance novels continued to feature female protagonists, and women readers continued to find in the heroines reflections of their own thoughts and desires. However, among the younger and more progressive women and men authors, the focus of conflict gradually shifted to the Chinese parents and customs, which were seen as rigid, irrational, and unfair to women. The dearth of women contributors, combined with the growing number of women readers whom romance publishers liked to court, might have motivated male authors to publish under feminine pseudonyms.

What Women Wrote

Up until the 1920s, women novelists appear to be nonexistent. The women writers were primarily poets—such as Tan Tjeng Nio and Lioe Gwat Kiauw Nio—or translators of Chinese works—such as Lie Keng Nio, Lie Loan Lian Nio, and Lie Djien Nio, who translated Chinese detective stories in the 1920s, before writing original novels and short stories in the following decade.

Women novelists began to emerge in the middle of the 1920s. Chan Leang Nio’s novel of a family drama set in Soerabaja, Tamper Moekanja Sendiri (To Slap One’s Own Face, 1925), was featured in the first year of the literary monthly Penghidoepan, an extraordinary feat for a woman, considering that popular journals such as Penghidoepan and Tjerita Roman featured only approximately one woman writer per year.12) Despite Chan’s accomplishment, the voice of the woman protagonist was indistinguishable from the voices created by male novelists. It is worth noting, however, that the moral of Chan’s story at least sides with the character of the ill-treated wife, Tin Nio, whose domineering husband ultimately regrets his mistakes and begs for her forgiveness. In the novel, the city of Soerabaja and especially the Chinese community’s penchant for gossip is described as an oppressive force in the life of Chinese women: Tin Nio must relocate to Medan in order to start anew after a failed marriage. An original composition by Kwee Ay Nio of Semarang, Pertjintaan jang Sedjati (True Romance), was featured in Penghidoepan in 1927; but, like Chan’s, Kwee’s story is unremarkable in that neither the characters nor the narrator conveys a perceptible woman’s voice or a woman-centered outlook on life. The story’s rags-to-riches motif is presented in an uncomplicated way, with a clear line separating good and evil, like in traditional didactic tales.

Likewise, the novel by The Liep Nio, Siksa’an Allah (Affliction from God, 1931), was written in the mold created by her male predecessors. A native of Probolinggo, The also wrote short stories, poems, and essays for the magazines Liberty and Djawa Tengah Review (Salmon 1981). The opening scene of Siksa’an Allah, where we find the despondent protagonist cuddling and caressing her cat, is unusually tender and tactile in temperament, which at first sight appears to distinguish The from her male counterparts. This promising early signal—that a woman author might in fact write differently from men—proves to be unfounded when the woman protagonist Liang Nio slides into a downward spiral after opting to pursue romance over her filial duty by eloping. Her lover, a spoiled rich brat, proves to be an indolent man who turns abusive when pressed into difficult circumstances. Liang Nio eventually sees what her parents have seen in her lover—an unscrupulous man—but this realization comes belatedly. She dies in agony, and the story repeats when her husband coerces their adolescent daughter Liesje into becoming the mistress of a wealthy old man, setting up an Anna Karenina-like ending with Liesje in front of an oncoming train. Rather than conjuring up a world where women make defensible choices, The Liep Nio seems to confirm the prevalent view that women act on passion, not reason, and as a consequence bring disgrace to their family.

A novel written under the pen name “Gadis Goenoeng” takes issue with the prevailing practice of arranged marriage. Anak Haram spotlights the enduring and tragic consequence of elopement through the figure of Lian Nio, who is born of eloping youths, given up for adoption, and lives with the social stigma of an illegitimate child. Lian Nio moves to the city of Soerabaja, in part to track down her origins, in part to escape her disgraced status. When later she finds love with the son of a prominent family, his father predictably disapproves, because her obscure background will stain his family’s high standing. Heartbroken, Lian Nio returns to Bangil and dies of heart failure, thus replicating her mother’s fate of dying young at the beginning of the novel. Like the character Liang Nio in The’s Siksa’an Allah, at first glance Lian Nio’s sad lot appears to be a persistent punishment for her parents’ disregard of their filial duty. Hellwig (2012, 175) reads the story along this line, that it sends a message to readers “not to be blinded by modern liberties.” My take on it is different, though: the author sympathizes with Lian Nio and, voiced through various characters in the story, questions the oppressiveness of a Chinese custom that takes its toll on an innocent life. As the male protagonist in the story observes, Chinese society (siahwee) holds men in higher regard and treats them better than it does women. Such sympathetic views of women notwithstanding, Gadis Goenoeng’s protagonist fails to challenge the status quo or to offer an alternative scenario that is more equitable for a woman in her situation.

Curiously, a few years before Anak Haram appeared, from roughly 1930, the Sino-Malay literary scene witnessed the appearance of novels with notable female agency written by Indies Chinese women. This group included novelists such as Khoe Trima Nio (Aster), Tan Lam Nio (Dahlia), Miss Kin, Yang Lioe, and the above-mentioned Lie Djien Nio (Mrs. Leader), some of whom counted themselves as women activists and journalists in addition to romance writers. Their novels feature increasingly autonomous female protagonists who are intelligent, outspoken, culturally sophisticated, and self-reliant. They are autonomous in that they exist with a clear sense of their own fulfillment, not for the sake of the family or the husband, and therefore not as an accessory to men’s happiness. These characters are far removed from the male-centered universe of conventional novels such as Kwee Tek Hoay’s Boenga Roos dari Tjikembang (The Rose of Tjikembang, 1927), where wives and concubines persist or perish for the sake of the male characters’ happiness.

Khoe Trima Nio, writing under the nom de plume “Aster,” was a contributor to the popular literary and cultural magazine Liberty and a member of the Indonesian Chinese Women Association, an organization launched in 1928 by another woman journalist, Hong Le Hoa (Salmon 1981; Sidharta 1992). Her novel Apa Moesti Bikin? (What to Do?), which featured in Penghidoepan (February 1930), revolves around the single-mother character Hiang Nio who has to raise her daughter alone after a failed marriage. Estranged from her gambling addict and uncaring husband, Hiang Nio makes the radical choice of widowhood, deserting Tjilatjap—where her husband lives—and starting anew with her infant daughter in Tegal under a new identity as Lim Kay Nio. A wealthy old widow sympathizes with her lot and helps her get back on her feet; she eventually becomes a respectable dressmaker in Tegal, financially stable enough to send her only daughter to Shanghai to pursue a bachelor’s degree. The women characters in Khoe’s story support each other, a motif frequently found in writings by women (Hellwig 2012); the omniscient narrator sees and speaks from their perspectives and stresses the importance of formal education for women as a condition to becoming self-reliant. The novel’s happy ending distinguishes it from Koo Han Siok’s novel on a similar theme, Kawin Soedara Sendiri (Married to One’s Own Sibling), published two years earlier.

The February 1930 issue of Penghidoepan also features a second, shorter story penned by “LSG of Tjilatjap,” whom Salmon identifies as Khoe’s other pen name, and the residency in Tjilatjap appears to confirm this. Unlike the main story, however, the second composition is told from the point of view of a young man first-person narrator whose romantic relationship with a girl falls victim to her “rigid, old-fashioned” parents. Though assuming a male voice, the narrator nonetheless faults “the common practice of Chinese people with adolescent-age daughters, whom they mercilessly place in prison alias pingit,” from which marriage is the only (and inevitable) escape (LSG 1930, 66). Speaking through Kim Lian, the young male narrator, Khoe writes against the patriarchal custom that deprived young women of basic freedoms and severely limited their life’s choices.

If Khoe’s character Hiang Nio refuses to remain in an oppressive marriage, the adolescent heroine in Miss Kin’s novel, Doenia Rasanja Antjoer! (Like the World Is Shattering!, 1931), rebels against arranged marriage. Tjio Hong Nio, the protagonist, is in a romantic relationship with a boy from a humble background, Lim Tjin Seng, but her parents refuse to acknowledge this and instead accept the proposal from Tan Giauw Siang, son of a former Chinese officer (kapitan), to make Hong Nio his second wife. Feeling pressured and powerless to go against her father’s wishes, and lacking the courage or resources to break ties with her parents, Hong Nio resorts to hanging herself; she would rather die than break her promise to Tjin Seng and become a second wife. Fortunately, she is rescued in time and her parents finally relent. The novel expresses surprisingly progressive views about gender equality, properly written by a woman. In objecting to her parents’ denial of her own will and desires, Hong Nio seems to speak for women of her generation. Her insistence that a woman must be able to choose her own life partner because she is the one who has to go through the marriage signals a shift in the conception of marital union—from an affair of the family to the two individuals forming a nuclear unit. Hong Nio’s objection to being made a second wife is even more striking as it stems from a firm conviction in the basic equality between the sexes. A second wife, Hong Nio concurs, is essentially a prostitute because, deprived of legal protections and stability, she is at the mercy of her master, whom she must constantly please. Such an arrangement renders a second wife no more than an instrument (pekakas) for the man’s pleasure, much more so if she is acquired in exchange for money. By deciding to take her own life rather than submit to her father’s demand, Hong Nio seems to convey that a woman holds the ultimate authority over her own life.

Yang Lioe, the author of Pasir Poetih (1936) and Pelita Penghidoepan (Beacon of Life, 1937), appears to be not an actual name, but the pen name (“Willow Tree”) of a woman writer. She also wrote for Liberty, a journal that was quite progressive in its time and was closely connected in terms of personnel with both Penghidoepan and Tjerita Roman. Her novel Pasir Poetih features two adolescent sisters who, orphaned and impoverished by the death of their father, go to live with their miserly maternal uncle in Pasir-Poetih, a tea estate in West Java. Long before that, we are told, their mother was disowned by her family for eloping with their father, a transgression for which she allegedly was disinherited. It is revealed later, however, that the girls’ maternal grandfather had actually passed on his assets to their mother, making them the legitimate beneficiaries of the estate. But their unscrupulous uncle has another plan: to arrange for the elder sister, Kiok Lan, to marry his son Giok Hoo, so he does not have to surrender the estate to the girls. Kiok Lan rejects this arrangement outright, despite her real feelings for the sympathetic Giok Hoo, just so she can disprove her imperious uncle about “woman being a compliant creature, can be pushed around” (Yang 1936, 75), especially in a matter so important as marriage. The characterization of the sisters—well educated and comfortable with modern ways of thinking—seems to be indicative of Yang, the author herself. Both Kiok Lan and her sister, Betty, believe that persons who have been exposed to Western education must necessarily “have a modern outlook and therefore good manners,” meaning that they treat women with respect. The novel is rather Austen-esque in temperament, specifically Pride and Prejudice; in this case, barriers to the protagonists’ romantic union finally fall after Kiok Lan overcomes her pride and Giok Hoo proves that he does not share his father’s prejudice. Yang’s other novel, Pelita Penghidoepan, is similar in nature, with an equally strong and proud female protagonist.

In terms of characterization, the protagonist in Lie Djien Nio’s novel Soeami? (Husband?, 1933) is perhaps the most “modern” among the heroines. A translator of Chinese detective stories early in her career, Lie also wrote articles for Liberty, Sin Bin, and Panorama. She was such an established name that her translations and original works appeared in reputable journals such as Tjerita Pilian, Penghidoepan, and Tjerita Roman—though admittedly, her translation works were poorly done, quite different from her original composition in the 1930s. In terms of storyline, Soeami?, which was published under the pseudonym “Mrs. Leader,” offers nothing new or remarkable. It relates the story of a wife who goes through the pain of neglect and eventual abandonment by a straying husband, left to raise her children alone. What sets the wife figure, Lie Tjoe, apart from other contemporary romance heroines is that she is a journalist. She has all the credentials of a “modern” woman: she is a graduate of the European Elementary School (Europeesche Lagere School), she has been brought up in the Dutch ways, she speaks Dutch with her friends and associates, and she is comfortable associating with men.13) Unlike many of her contemporaries, Lie Tjoe marries by choice, not through an arrangement. Her husband, Ho An, too, is a modern man who never inhibits her professional work; this was an important reason why she chose him. Her goals in life are to become a famous author, like the Dutch woman writer and journalist Anna de Savornin, and to be happily married. At times, however, she wonders whether these goals are compatible. As a journalist, Lie Tjoe writes about the fate of Indies Chinese women and wives; and being a married woman, her writings resonate with many women readers. She is a “genuine” (soenggoean) woman journalist, we are told, unlike the “pretenders” (tetiron), presumably men journalists writing under female pseudonyms. Like the character Lie Tjoe, who speaks through her writings, the author Lie Djien Nio appears to speak through Lie Tjoe; at times their voices seem to conflate. Both seem to ask, “What is the meaning of husband?” as the title suggests, and concur that a husband must be more than just a material provider. Having had a marriage of choice, Lie Tjoe longs for a fuller connection, which is better fulfilled by her old friend and fellow journalist Soey Mo. Curiously, despite her husband’s infidelity, Lie Tjoe does not see it as a license for her to pursue another love, insisting on her principle of boundaries as a married woman. Her faith in it pays off when in the end, betrayed by his mistress, penniless Ho An returns and pleads for her forgiveness. The story ends happily with their reunion and Lie Tjoe gradually withdrawing from journalism in order to focus on being a housewife. Her own question seems to be answered: that for women, professional career and happy marriage are mutually exclusive, and that the latter must always be prioritized—a surprisingly conservative moral from such an unconventional heroine. Lie Djien Nio perhaps signaled this in her choices of pseudonyms: both “Njonja The Tiang Ek” and “Mrs. Leader” mark her status as a married woman, in addition to subsuming her identity under her husband’s. One might say that even in her professional life, she was defined by her marriage.

What the narrator in Soeami? has hinted, however, is relevant in this inquiry concerning female subjectivity: that there might be elementary differences in the way “genuine” women write, because while gender is performative, it is performed on a daily basis and is constantly reproduced by each performance. There is thus an expectable difference between men writers who assume the feminine voice only in imaginative writings and women writers who speak based on experience. A “genuine” woman writer lives her life performing the conventions of her gender, making her representation of women relatively more perceptive and persuasive. It resonates with women readers who are likewise identified. These assumptions, of course, overlook the diversity of women’s experiences in terms of class or ethnicity but might be indicative of the demographic segment that produced and consumed Malay romance novels in the Indies.

Nevertheless, as reflections of (as well as reactions to) the male-centered structure that shaped them, the literary works penned by women authors do not always feature an autonomous woman protagonist or a heroine with strong female agency. The heroines created by the male novelist Madonna are by and large more emancipated compared with those in novels by female authors such as The Liep Nio, Kwee Ay Nio, even Lie Djien Nio. As late as in the latter half of the 1930s, Phoa Gin Hian translated Chinese romance stories that cautioned against Western education for young women, the most conservative of which is Pembalesan Dendam Hati (Revenge of the Heart, 1935). The aforementioned Tjan Kwan Nio, who emerged in the early 1940s, likewise produced novels with rather conventional women characters, including an unexpected rehash of the femme fatale motif in Bidadari Elmaoet (Angel of Doom, 1941).

Despite the novel’s conservative moral, the narrator in Soeami? can perhaps furnish us with a workable parameter of what distinguishes female from male authors: the relative capacity to resonate among women readers, the ability to perceptively communicate the experiences, feelings, thoughts, and desires that women in general identify with. A female writer is presumably better equipped to represent these qualities than a male writer, or a man writing in the feminine voice for that matter. And it is generally true that women authors were more enthusiastic in taking up a certain set of issues, such as marriage, education, career, and equality between the sexes. These issues were defined by the boundaries of the real women’s world, making their writings less commercially oriented than those produced by men (Salmon 1984, 169). The stories and the heroines they paint tend to have a broad authorial brush, suggesting a close proximity to their own experiences as women. The most original and compelling author in exploring “women’s issues” is indeed a woman novelist by the pen name “Dahlia,” to whom we now turn.

Dahlia

Dahlia is the nom de plume of Tan Lam Nio, a writer who in her early 20s produced novels with the most distinct female agency. Tan was born in 1909 in Soekaradja, West Java, and in 1929 married a journalist and writer by the name of Oen Hong Seng, who in the same year served briefly as director of the monthly Boelan Poernama (Full Moon) (Salmon 1981, 273–274). At the age of 20, she was not quite a young bride; her contemporary, the novelist Tjan Kwan Nio (1992, 159), described the age of 18 as preferable for marriage but was herself wedded at the age of 16. Though it appears that Tan began her writing career only after marrying Oen, their book-length works show that Tan actually published ahead of her husband. They appear to have resided in West Java early on, and their works between 1930 and 1931 appeared in Goedang Tjerita (Warehouse of Stories) and Boelan Poernama, both Bandoeng-based periodicals. From 1932 on, their writings appeared in the Soerabaja-based Tjerita Roman, Penghidoepan, and Liberty—all of which were comparatively better known. While Oen, who wrote under the pen name “Madonna,” began as a translator of European and Chinese works, Tan appears to have started out as a full-fledged novelist. Later on Oen would follow in the footsteps of his accomplished wife in writing about Chinese marriage customs, women’s rights, and interracial romance.

Before her life was cut short at the age of 24 by a sudden illness,14) Tan wrote—among other novels—Kapan Sampe di Poentjaknja, atawa Tjinta dan Pengorbanan (Upon Reaching the Top, or Love and Sacrifice, 1930), Hidoep dalem Gelombang Air Mata (Living in the Tide of Tears, 1932), Kasopanan Timoer (Eastern Civility, 1932), Doerinja Pernikahan (Matrimonial Thorns, 1933), and Oh, Nasib! (Oh, Destiny!, 1933), in addition to short stories published in Liberty.15) The last two novels were published posthumously; her husband wrote an introduction to the latter to explain that the manuscript had been completed only days before Tan fell ill. In her last work published by Tjerita Roman—her second in as many years—a short obituary from the editor likens “Dahlia” to a blossoming flower, seemingly at the peak of her literary career. It refers to her as a diligent and loyal staff member (pembantoe) and comments on the popularity of her novels, especially among women readers. It appears that Tan had become a freelance contributor to the journal by the time of her passing, surely a notable achievement for a woman in the male-dominant world of literary publishing.

What is remarkable about Tan’s novels is the audaciousness of her heroines. Her stories explore a range of topics related to the position of women in Chinese society—from education, romance, and marriage to professional career—and with the exception of her last novel, they are anchored by a female character who is intelligent, confident, outspoken, well educated, and fiercely independent.16) While education for young girls was a contentious issue in the preceding decades since the establishment of THHK schools, in the 1930s the battlefield for women’s emancipation had shifted to issues concerning economic autonomy and women’s right to work outside the domestic sphere and in the formal sector. The customary practice of arranged marriage remained an issue but was increasingly contested from the point of view of the daughter and her supposed right to pursue personal happiness, and away from the Confucian moral of filial duty. Tan’s novels Kapan Sampe di Poentjaknja and Kasopanan Timoer in particular take up these issues and reformulate them in remarkably progressive frameworks and language.

Kapan Sampe di Poentjaknja might well have been Tan’s first novel. It features the enduring theme of father-daughter confrontation over her matrimonial choice (or lack thereof). This subject has been dealt with in countless ways, yet it continues to be the novel’s most featured theme, popular among Chinese and non-Chinese readers alike. Here, the affluent Nora Tio befriends and develops romantic feelings for her uncle’s office employee (pegawe) Tjeng Giok, who comes from a humble background. The attraction is mutual, but Nora unwittingly also attracts the attentions of Henri Tjoe, the son of a wealthy family who subsequently sends a marriage proposal to her parents. To Nora’s indignation, her father wants her to break off her relationship with Tjeng Giok and accept Henri’s proposal. When pressured, Nora absconds to Batavia to join Tjeng Giok, who earlier moved to the city for a more promising employment.

Unlike most heroines in contemporary Malay novels, Nora is very assertive. She is confident, knows what she wants, and sets out to accomplish her goals. She is intrigued by Tjeng Giok, but he is especially reserved with her because of his position as a staff member in her uncle’s workshop. So she takes the initiative in approaching him and nudges him to confess that he, too, has feelings for her. In their relationship, she appears to be the one in charge, as when she drives and he sits in the passenger seat when they go to places. When their relationship meets obstacles, due to her father’s objections to Tjeng Giok’s lower social standing, she challenges the timid Tjeng Giok to prove himself worthy of her affection. He leaves Semarang for Batavia to work at a European firm that pays sufficiently well for him to start saving for their future. Nora talks back to her father, an act that is regarded as especially disrespectful according to the Confucian moral of filial piety. When her father declares that there is a “big possibility” that he would accept the marriage proposal from Henri Tjoe, Nora retorts, “On what basis do you say that? Do you know that there is just as big a possibility that I turn it down?” (Dahlia 1930, 61).17)

Nora turns the notions of duty and propriety on their heads. Not only does she reverse conventional gender roles in courtship, she rejects the idea of filial duty. She accuses her father—who covets the prestige his family would gain through a marriage connection with the wealthy Tjoe family—of being “blinded [silo] by riches,” of selling (djoeal) her, and of using her as capital (poko) to acquire material security and add prestige to his name. Reminded that in the Chinese tradition she is under her parents’ authority until she is married, Nora asks whether marriage is essentially a trade transaction (saroepa perdagangan). It used to be proper for parents to demand from a daughter her self-sacrifice for the benefit of the entire family, in this case for Nora to prioritize the overall welfare of her family over her personal desires. This is understood as her filial duty to her parents, as a form of “repayment” to them for bringing her into the world and nurturing her to adulthood. But by Nora, this well-established concept is made foreign and the duty is unacknowledged for the simple reason that she, like any other child, never asked to be born. What comes to the fore instead is a new notion of a woman’s inalienable right to self-determination, including her right to pursue personal happiness, disconnected from that of her family. In other words, she insists on the right to exist for her own gratification, not as an accessory to her family’s happiness. This new concept of rights cancels out any form of filial piety that is predicated on self-sacrifice. When pressured by her father to comply with his choice of suitor, Nora warns him “not to treat her like those girls who do not understand the meaning of liberty [kamerdika’an] and women’s rights [haknja saorang prampoean]” (ibid., 95). Her exposure to these ideas presumably shields her from being subjected to a condition of unfreedom, in this case her father overriding her own free will. In the novel, his stubborn insistence on parental authority is characterized as an existential violation, a “rape” (perkosahan) of her basic liberty, giving her the moral justification to flee to Batavia.

In the story, Nora’s school education is credited as being responsible for her values, the yardstick with which she measures what is proper and improper, as well as the ultimate resource to becoming self-reliant. Her Western name in some ways signals her cultural dispositions; her real name is Tio Kian Nio, but among friends at school she is known as “Nora.” Chinese students usually acquired their Western names at school, given by European teachers. Nora conducts herself in accordance with what she imagines a modern woman is supposed to do. Early on, she develops the courage to approach Tjeng Giok because “it would be embarrassing if as a modern girl she was nervous about being face to face with a man” (ibid., 12). Having gone through the Dutch secondary school (Hoogere Burger School, HBS), Nora is not clumsy in associating with peers of the opposite sex and, at the same time, is intellectually equipped to support herself. When she settles in Batavia, her sense of propriety does not allow her to be dependent on Tjeng Giok for a livelihood because they are not yet legally married. Disowned by her father for eloping, Nora easily secures a teaching job at a Dutch-Chinese School (Hollandsche Chineesche School) and becomes self-sufficient. Like her, Tjeng Giok is well educated; they correspond in Dutch.

In fact, school education and the notion of a self-made identity are important motifs in Tan’s novels. They mark “modern” individuals like Nora and Tjeng Giok. On the other side, there is an almost hostile attitude toward wealth—specifically, inherited wealth—and family connections. In Tan’s novels, sons of wealthy families almost always represent an obstacle that the heroine must overcome. They are the suitors preferred by old-fashioned parents who prioritize worldly status over the daughter’s happiness, or the spurned rivals who resort to violence to eliminate competition. Here, inherited wealth is associated with idleness, lack of independence, backwardness, illegitimacy, even criminality. Henri Tjoe hires a goon to eliminate his rival, Tjeng Giok, and when he fails, he flees to Singapore to elude the long arm of the law. Eventually he is penalized for this and other offenses, even after his father tries to use money and influence to get him out of trouble. Henri’s criminal case is widely covered by the Sino-Malay press, bringing shame to his family and, indirectly, serving as validation of Nora’s decision to choose the humble Tjeng Giok over the wealthy Henri. The novel seems to suggest that sons of affluent families are essentially spoiled brats and potential trouble, undeserving of intelligent women’s affection.

Nowhere is this preferential shift away from family fortune to personal ingenuity more apparent than in the changing quality of what counts as blessed matrimony. The Malay word beroentoeng (fortunate, blessed) was often invoked to refer to the state of material contentment, in which case a match to a suitor with a sizeable family fortune made perfect sense. In the prevailing Chinese custom, a marriage was essentially an alliance between two families, more than a union of two individuals. Hence, the “fortune” that a woman’s nuptial ties would bring was not hers individually, but collective—one from which her entire family could (and theoretically should be able to) benefit. Seen in this light, Nora’s attitude toward marriage is extremely self-centered, benefiting no one else but the couple involved. For this “modern” generation, marriage was less a calculation of collective benefits than the culmination of romantic heterosexual attraction. Thus, romantic love, not family fortune, was regarded as the only legitimate basis of marriage (Siegel 1997, 135). If in the custom of arranged marriage the bride and the groom hardly knew each other until the time they were wed, schooled youth generally had developed a habit of courtship before marriage, thanks in large part to the experience of coeducation. For youngsters who had gone through a period of courtship like Nora had, romantic attraction arose from compatibility in interests and outlook toward life. Thus, beroentoeng for them was largely immaterial, undifferentiated from romantic bliss, an abstract concept whose dissemination in fact owed much to the proliferation of romance novels. Unable to marry legally, Nora and Tjeng Giok wed in a small ceremony, attended by only a few close friends, and proceed to embrace a life that is said to brim with romantic bliss (penoeh madoe pertjintahan). Following her heart, Nora finds true fortune.

The novel’s happy ending sets it apart from many others with a similar theme. At an earlier time, or in works by other authors, heroines who follow their hearts are usually given tragic endings. But in Tan’s story, it is Nora’s father who undergoes a change of heart and regrets the way he treated his only daughter. Realizing that he has been wrong about Henri, Nora’s father finally sees that he has been led too far “astray” (tersesat), made insensible by the promise of the world’s riches (harta doenia). This new framing, forcefully articulated in Tan’s novels, would continue in the novels penned by her husband, Oen Hong Seng (a.k.a. Madonna) after she passed away.

Nevertheless, Nora’s admission of romantic attraction for Tjeng Giok must have been rather problematic. It implies sexual desire when a woman is expected to be chaste in both conduct and thought. Scholars have noted how romance novels, including Western novels in the Indies, were blamed for “putting ideas in women’s heads,” for awakening erotic desire (McCarthy 1979; Chandra 2011). In this story, Nora’s father represents the older generation with conservative values and expectations, who sees erotic desire and propriety as mutually exclusive. When Nora insists that she wants to choose her own marriage partner instead of having the choice made for her, her father likens her to a whore (soendel), an insult she finds especially intolerable. This episode is intriguing as it brings to the surface the underlying masculinist paradigm that sees women in binary terms, as either the virtuous Madonna or the debased prostitute. Sexual desire is associated only with the latter; thus the charge of Nora “acting like a whore” simply for wanting to choose her own marriage partner. While sexual virtue and modesty is arguably a masculinist fantasy projected onto women, this fantasy proved to be so well internalized that it remained relevant even for a progressive woman writer like Tan. The challenge for women writers who were sympathetic to young women faced with such a predicament was to carve out a prototype of a heroine who professed only to marriage based on romance, was self-supporting, made her living outside the domestic sphere, was not clumsy toward the opposite sex, and yet remained as virtuous as the Madonna. Tan’s heroines arguably are prototypes of the modern Madonna.

If Nora represents a properly modern woman’s view of marriage, Siem Kiok Nio in Kasopanan Timoer (1932) exemplifies the right attitude toward profession. The novel tells of Kiok Nio, who must resort to working outside the home after her father falls on hard times in his business and passes away, leaving Kiok Nio and her mother to fend for themselves. For a while they try the conventional alternative, making and selling cakes from home. But the income it generates is inadequate, so Kiok Nio decides to go against the current and makes use of her school diploma to secure a position at a Dutch firm (European firms generally paid better than Chinese firms). Working as a steno-typist, Kiok Nio does very well. She is serious and ambitious, earning the respect and admiration of her colleagues, particularly her supervisor, a young sympathetic Dutchman named Jansen, who soon falls for her. But Kiok Nio’s affection is reserved for Koen San, who, like her, is well educated and relies on personal ingenuity to find success. Kiok Nio’s biggest obstacle is not an old-fashioned, materialistic father but societal prejudice against women who work outside the domestic sphere. The challenge for her is to prove that professional women do not by definition lack virtue.

Like Tan’s other heroines, Siem Kiok Nio is portrayed as unfailingly modern. She is a graduate of secondary school (Meer Uitgebreid Lager Onderwijs) and therefore “no less educated than Dutch girls” (Dahlia 1932b, 24). She also has a Western name: she is known by her friends and colleagues as Johana Siem. Her “modern” qualities go beyond education; Tan emphasizes her manners, taste, and appearance. Kiok Nio dresses in a skirt most of the time, “like most modern girls with Western upbringing” (ibid., 70), not in the traditional kebaja ensemble of a blouse and long wraparound cloth. We are told that she is tall and not too fair, that people often mistake her for a Eurasian. The house she rents, where she and her mother dwell, is a little villa and decorated in such a way that it can be mistaken for a European’s residence.

Early in the story we are told how Kiok Nio sees being a woman as a handicap. She has graduated from secondary school and taken a stenography course, and yet, because she is a woman she is bound to stay at home after graduation. This was a prevalent view in Chinese society at that time, that for girls to work in an office was “unseemly” (koerang netjis)—“comparable to a prostitute walking the streets” (ibid., 9). So for a while, Kiok Nio is forced to shelve her diplomas and certified skills and try other things such as baking and dressmaking. “If only I were a man,” she laments.

Kiok Nio’s eventual success in overcoming this gender handicap is attributed to her modern spirit. Pressured by economic hardship and a sense of responsibility for her mother’s well-being, she finds a job at a European firm. She meets Koen San, who will become her romantic interest, on the job; he is a client of her company. He, too, is highly educated—he is a graduate of HBS and has studied in the Netherlands—and is pleasantly surprised when meeting her. “You must be the first Chinese woman to work in a trading company!” he commends before they exchange business cards (ibid., 34). While he admires her aptitude, she is impressed by his open-mindedness. They converse in Dutch.

Her education also guards her against unwanted overtures by wealthy married men, “who seem to be unaware that an educated woman like Kiok Nio does not capitulate so easily to becoming a concubine” (ibid., 75). Her modern spirit (semangatnja jang moderen) does not permit Kiok Nio to simply accept preconceived ideas and practices. She criticizes the tendency in society to hold women back, calling it narrow-minded, fanatical, and isolated from the fast-changing world. She regrets the “mossy views” (anggapan jang boeloekan) among some women who limit their life-scope to kitchen, appearance, and leisure. As the story progresses, Kiok Nio’s earnestness and determination are validated when her supervisor remarks that even though she is a woman, she is “capable of supporting a household, no less than a man” (ibid., 27). She no longer wishes she were a man, because as a woman she is no less than a man.

In the absence of the father figure, the abstract entity of the public represents the conservative force. In many contemporary romance novels, the father figure regularly assumes the voice of the conservative patriarch whose resistance to change the modern (usually lovestruck) youth must overcome. This is true in Kapan Sampe di Poentjaknja, where Nora’s father constitutes the most significant obstacle to her exercising self-determination. In Kiok Nio’s case, social impediments manifest in the form of a gossip-mongering Chinese public. While Dutch and other Indies women have become accustomed to making a living on their education, we are told that Chinese women are only now starting to follow suit. To the latter, publiek opinie is a constant specter; it has deterred many capable women from utilizing their talents in the proper places, “because they fear being chastised by the public” (ibid., 40). Every time Kiok Nio’s supervisor, a Dutchman, pays her a visit, the busybodies in the neighborhood get busy. But she perseveres, determined to prove wrong the common assumption that working among men and foreigners makes a woman “loose” (binal). This view, she opines, is outdated (koeno) and absurd (nonsens).

There is a discernible attempt to redefine modernity, or to establish an alternative modernity, in Tan’s stories. The modernity that Tan imagines thus far has been unfailingly (and almost indistinguishable from the qualities of being) “Western.” It has been equated with a wide range of practices identified with European norms—from attending school and having a career to driving a car and wearing skirts. It is also associated with intangible concepts such as romance, equality between the sexes, women’s rights, and individual self-determination. This makes Nora and Kiok Nio seem like mere duplicates of Dutch women, as derivatives, at the same time they try to be original and autonomous. In the introduction to Kasopanan Timoer, editor Ong Ping Lok remarks that the quality of being “East” cannot be narrowly defined by the veil or the customary seclusion for women (pinjit or pingit), because like Western civility, Eastern civility also progresses with the changing of time. In other words, adjusting to the changing of time does not make a woman “Western” by default, and one can become modern and Eastern simultaneously. Indeed, the novel’s title, “Eastern Civility,” seems to suggest this alternative—the possibility of an Eastern modernity, exemplified by Kiok Nio’s sense of moral virtues. Like the aforementioned journalist heroine in Lie Djien Nio’s novel Soeami?, Kiok Nio, too, associates freely with men without transgressing a self-imposed line of propriety.18) This line is understood to be private, known only to the one observing it, and does not require societal approval. Kiok Nio remains virtuous not due to fear of societal reprimand, but because she has a firm grasp of boundaries and self-respect. So even though the public deems her “Western obsessed” (gila kebaratan), her conscience (liangsim) remains firmly anchored in Eastern civility.

Curiously, remaining Eastern for a Chinese woman also means disciplining her desire and limiting it to only Chinese man. Faced with two equally eligible suitors—Jansen and Koen San—Kiok Nio is drawn to the latter. She is more comfortable around her own kind. When Jansen proposes, she reminds him that they are of different races (bangsa) and that his family would not approve: “East goes with East, West with West” (Dahlia 1932b, 51). In fact, to be properly modern in this novel is for one to accord proper dignity to one’s national group, which is not unexpected given the rising tide of nationalist sentiment in the Indies at the time (Williams 1960). While intermarriage was the norm among early Chinese migrants to the archipelago (Sidharta 1992; Salmon 1996; Skinner 1996), from the second half of the nineteenth century various colonial legal codes had led to the constitution and stratification of “races” and the sharpening of racial boundaries in the Indies (Albrecht 1890; Willmott 1961; Coppel 2002b). Thus, while Dutch, Chinese, and Javanese students, for instance, might find themselves freely associating with each other as schoolmates at an HBS, or as co-workers once they graduated, social pressures discouraged such associations from developing into interracial matrimony. This is what we see with Kiok Nio, that a modern Chinese woman can be like Dutch women in all regards—education, career, appearance, lifestyle—except in the object of desire. Kiok Nio cannot be like Jansen, whose love does not see race.19)

The distinction between “Western” and “modern Chinese” women is further explored in Tan’s subsequent novel, Doerinja Pernikahan (1933), where the morality of women graduates of Dutch and Chinese schools is compared and contrasted. The modern heroine in this novel does not clash with her father but with her Dutch-educated husband and peers. The Chinese and Dutch names given respectively to the righteous heroine and her shifty antagonist—Sioe Lan and Tientje—are telling. Sioe Lan is modern but was brought up in the “Eastern” way, a graduate of the Chinese THHK school, not a Dutch school. She is supposedly modern and virtuous, not modern and loose like Tientje. Commenting on the novel, Hellwig (2012, 155–157) reads the focal conflict in rather binary terms—Eastern vs. Western, Chinese/Asian vs. Dutch/European, tradition vs. modernity—and concludes that the story conveys a conservative message. On the contrary, I see it as a further attempt by Tan to redefine Eastern civility as a form of alternative modernity, making her an early herald of what would be the postcolonial quest to establish modernity as a plural condition without a “Western governing center” (Gaonkar 2001).

Unfortunately, we do not have many more works by Tan to explain this rather ethno-centric (or early postmodern) turn in her writing, as she passed away not long after the manuscript of Doerinja Pernikahan was submitted to the publisher. Sentiments of ethno-nationalism in general were on the rise among the Chinese population in the Indies ever since Japan annexed Manchuria in 1931. In Tan’s novels, this sentiment might have manifested as her defense of a number of Chinese virtues to balance out her critiques of practices oppressive to women. On the other hand, the desire to refine and redefine progress was not hers alone. The contemporary Chinese women’s monthly Istri (Wife, 1937–42) has been described as a magazine that “tries to achieve progress in harmony with Eastern civilization” (Sidharta 1992, 71).

Regardless, the modernity that Tan expounds for the most part manifests as a challenge to traditional gender roles, specifically the roles prescribed for women. It does not lack substance, as Siegel (1997, 146–147) observes in other contemporary Malay novels’ treatment of modernity, but corroborates his findings that it fails to address relevant issues such as inequality or separation between races. Tan’s modernity reiterates racial preconceptions, because she molds her new woman within the broader framework of the “Eastern/Chinese” woman.

Conclusion

This essay sets out to review the literary works written by Chinese women authors and to provide a sketch of what women in the first few decades of the twentieth century Indies wrote when they finally became published authors. It outlines some patterns of themes, motifs, and narrative angles found in their writings that might distinguish their works from those written by male authors. The question of voice immediately springs forward: Who counts as a woman author or has the authority to speak on behalf of Indies Chinese women? A good number of male writers, as it turns out, wrote in the feminine voice by assuming feminine pen names and speaking through a female protagonist or narrator. Some of them created heroines with compelling female agency, such as the heroines in Madonna’s novels Berdosa (Transgressing, n.d.) and Impiken Kaberoentoengan (Hoping for a Contented Life, 1935). In contrast, a good number of women novelists produced weak and forgettable female protagonists. Thus, female authorship did not guarantee an autonomous female protagonist, or a woman-centered narrative for that matter. But while men authors wrote about a broader range of topics, women authors dealt largely with issues that immediately concerned them. In general, the latter group could be expected to be more candid with respect to gender inequality and the position of women in Chinese society, even when these problems were presented in a pessimistic light.

Other broad conclusions can be drawn. In the Indies, women began to write novels only in the 1920s, and in prose writing early on their voices were largely indistinguishable from those of their male counterparts. Their central characters are generally women, who seem to have come from the same mold created by their male predecessors. The narratives presented are timeless—intergenerational clash between old-fashioned parents and modern daughters—and have been explored in countless ways by writers before them. The possibilities accorded to the fictional daughters are limited: they wilt under social pressure or are overpowered by the modernity they desire to embrace. Only from the 1930s do we witness the emergence of new prototypes, that is, heroines who successfully utilize modern attributes such as education to challenge the entrenched patriarchal order. In such stories, it is the parents (often the father) who undergo a change of heart and find their way back to the moral path.

The most remarkable among the Chinese women novelists was Tan Lam Nio, who wrote under the pen name Dahlia. Her works wrestle with problems related to gender inequality in Chinese society in the Indies, specifically in relation to education, marriage choice, and career. While in the 1930s attending school for women had become less of a contentious issue, gender inequality manifested most visibly in the problems of arranged marriage and women acquiring a formal profession. Tan explores these topics from a woman’s perspective and deals with them in a way that accords agency to the women characters. Her heroines are ardently modern, but modern in the way that makes them almost indistinguishable from Dutch women, at least initially. Becoming like Dutch women appears to be the prototypical modern woman in Tan’s imagination, and this might be jarring to her overwhelmingly Chinese readers. Tan’s interlocutors are indisputably “Chinese,” and this might have compelled her to redefine her heroines into an Eastern version of modern women after her first novel. Reading them, we are to infer that modern is neither identical with Western nor mutually exclusive with Eastern. It is unfortunate that Tan did not have the opportunity to further explore her ideas of modernity, womanhood, being Chinese, and—who knows?—being Indonesian. Passing away at the youthful age of 24, Dahlia withered at the peak of her bloom.

Accepted: May 14, 2015

Acknowledgments

This article came out of a collaborative research project on women writers in Asia; I wish to thank my fellow researchers—Aoki Eriko, Kuwabara Momone, and Tominaga Yasuyo—for a stimulating, fun, and fruitful collaboration. I am also grateful to Evi Sutrisno, Claudine Salmon, Endy Saputro, Sutrisno Murtiyoso, and Harianto Sanusi for various materials used in this article, and to SEAS anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments. All errors are my own.

Bibliography

Albrecht, J. E. 1890. Soerat Ketrangan dari pada Hal Kaadaan Bangsa Tjina di Negri Hindia Olanda [Handbook on the status of Chinese nationals in the Netherlands Indies]. Batavia: Albrecht & Rusche.

Alcoff, Linda. 1988. Cultural Feminism versus Post-structuralism: The Identity Crisis in Feminist Theory. Signs 13(3): 405–436.

Aster. 1930. Apa Moesti Bikin? [What to do?]. Penghidoepan 62 (February).

Bloom, Harold, ed. 2008. The Brontes. New York: Infobase Publishing.

Boenga Mawar. 1902. Boekoe Pantoen Pengiboer Hati [Book of verses to please the heart]. Batavia: Albrecht & Co.

Butler, Judith. 1993. Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex.” New York: Routledge.

―. 1990. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge.

Chan, Faye Yik-Wei. 1995. Chinese Women’s Emancipation as Reflected in Two Peranakan Journals (c. 1927–1942). Archipel 49: 45–62.

Chan Leang Nio. 1925. Tamper Moekanja Sendiri [To slap one’s own face]. Penghidoepan 6 (June).

Chandra, Elizabeth. 2011. Women and Modernity: Reading the Femme Fatale in Early Twentieth Century Indies Novels. Indonesia 92 (October): 157–182.

Coppel, Charles A. 2002a. Emancipation of the Indonesian Chinese Woman. In Studying Ethnic Chinese in Indonesia, pp. 169–190. Singapore: Singapore Society of Asian Studies.

―. 2002b. The Indonesian Chinese: “Foreign Orientals,” Netherlands Subjects, and Indonesian Citizens. In Law and the Chinese in Southeast Asia, edited by M. B. Hooker, pp. 131–149. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Dahlia. 1933a. Doerinja Pernikahan [Matrimonial thorns]. Tjerita Roman 51 (March).

―. 1933b. Oh, Nasib! [Oh, destiny!]. Penghidoepan 105 (September).

―. 1932a. Hidoep dalem Gelombang Air Mata: Satoe Drama Penghidoepan terdjadi di Medan [Living in the tide of tears: A life drama which occurred in Medan]. Medan: Dj. M. Arifin.

―. 1932b. Kasopanan Timoer [Eastern civility]. Tjerita Roman 42 (June).

―. 1930. Kapan Sampe di Poentjaknja, atawa Tjinta dan Pengorbanan [Upon reaching the top, or love and sacrifice]. Goedang Tjerita 5 (September.)

Departement van Economische Zaken [Department of Economic Affairs]. 1935. Volkstelling 1930, deel VII, Chineezen en andere Vreemde Oosterlingen in N.I. [1930 cesus, section VII, Chinese and other Foreign Orientals in Netherlands Indies]. Batavia: Departement van Economische Zaken.

Engels, Frederick. 2004. The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State. Chippendale: Resistance Books.

Fanon, Franz. 1967. Black Skin, White Masks. New York: Grove Wiedenfeld.

Gadis Goenoeng. 1938. Anak Haram [Bastard child]. Tjerita Roman 115 (July).

Gaonkar, Dilip Parameshwar, ed. 2001. Alternative Modernities. Durham: Duke University Press.

Govaars-Tjia, Ming Tien Nio. 2005. Dutch Colonial Education: The Chinese Experience in Indonesia, 1900–1942. Singapore: Chinese Heritage Centre.

Hall, Stuart. 1997. The Local and the Global: Globalization and Ethnicity. In Culture, Globalization, and the World-System: Contemporary Conditions for the Representation of Identity, edited by Anthony D. King, pp. 19–39. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Hatley, Barbara; and Blackburn, Susan. 2000. Representations of Women’s Roles in Household and Society in Indonesian Women’s Writing of the 1930s. In Women and Households in Indonesia: Cultural Notions and Social Practices, edited by Juliette Koning, Marleen Nolten, Janet Rodenburg, and Ratna Saptari, pp. 45–67. Richmond: Curzon Press.

Hellwig, Tineke. 2012. Women and Malay Voices: Undercurrent Murmurings in Indonesia’s Colonial Past. New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

―. 1994a. Adjustment and Discontent: Representations of Women in the Dutch East Indies. Windsor: Netherlandic Press.

―. 1994b. In the Shadow of Change: Images of Women in Indonesian Literature. Monograph No. 35. Berkeley: Center for Southeast Asian Studies, University of California.

Irigaray, Luce. 1985. This Sex Which Is Not One. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Kennedy, Maev. 2013. From the Brontë Sisters to JK Rowling, a Potted History of Pen Names. The Guardian, July 14.

Koo Han Siok. 1928. Kawin Soedara Sendiri [Married to one’s own sibling]. Penghidoepan 38.