Contents>> Vol. 5, No. 3

The Case of Regional Disaster Management Cooperation in ASEAN: A Constructivist Approach to Understanding How International Norms Travel

Muhammad Rum*

* Department of International Relations, Faculty of Social and Political Science, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Jalan Socio-Yustisia No. 1, Bulaksumur, Sleman, Yogyakarta 55281, Indonesia; Graduate School of International Development, Nagoya University, 1 Furo-cho, Chikusa-ku, Nagoya, Aichi 464-0814, Japan

e-mail: rummuhammad[at]yahoo.com; muhammad.rum[at]a.mbox.nagoya-u.ac.jp

DOI: doi.org/10.20495/seas.5.3_491

This paper demonstrates how constructivism is applicable to the rationale for the growing trend in international relations. The case to be examined is disaster management cooperation in the Southeast Asian region, although there are now 13 regional organizations around the world implementing concerted regional efforts to respond to and reduce the risk of natural disasters. This paper suggests that national interest is not the sole motive for member states to support this agenda; there are also norms that dictate how states recognize the appropriateness of a behavior. Member states believe that establishing regional disaster management is an appropriate behavior. In an attempt to discuss how the norms for disaster management were adopted in the Southeast Asian region, this paper underlines the importance of international dynamics of norms in the formation of the ASEAN regional disaster management architecture. Ideas travel from one mind to another, and this happens also in international politics. Hence, this paper uses the norm life cycle framework to track the journey of international disaster management norms. The idea of disaster management norms emerged and was promoted by norm entrepreneurs on the international stage, and from there international organizations introduced the idea to the Southeast Asian region.

Keywords: international dynamics of norms, norm life cycle, regional disaster management cooperation, ASEAN

I Introduction

I-1 Background

The 10 member countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) started cooperating on disaster management under the framework of the ASEAN Agreement on Disaster Management and Emergency Response (AADMER), signed in 2005 and in force since 2009. Cooperation under AADMER is an institutionalized expression of the member states’ joint efforts. Previously, ASEAN worked in an ad hoc manner to deal with major natural disasters, especially the Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami of 2004 and Myanmar’s 2008 Cyclone Nargis.

ASEAN now has two operating arms for disaster management. To facilitate the institutionalization of regional cooperation, the ASEAN Secretariat established a division responsible for Disaster Management and Humanitarian Assistance (DMHA). This division works to help the 10 member states discuss the agreement, facilitate meetings to formulate standard operating procedure, and assist the parties in building a working plan for future development several years ahead. In addition, for executing mandated works such as dispatching emergency response and survey teams, coordinating aid from different member states, and delivering such aid to the field, the 10 member states established the ASEAN Coordinating Centre for Humanitarian Assistance on Disaster Management (the AHA Centre) in November 2011, headquartered in Jakarta. The AHA Centre has been involved in some major humanitarian operations, such as in Thailand’s floods of 2011–12, the Philippines’ Typhoon Bopha in December 2012, response preparation on the eve of Myanmar’s Cyclone Mahasen in May 2013, the Aceh’s Bener Meuria earthquake in July 2013, and Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines in November 2013.1) This development is considered relatively progressive for ASEAN, which was originally established in 1967 as a political effort to contain Communism.

I-2 Significance of the Study

The development of ASEAN is not a unique phenomenon in the contemporary world. Within the last decade there have been many other intergovernmental arrangements established by different actors. The international community has agreed to further support the Hyogo Framework of Action (HFA) of 2005 as the basis for strengthening global, regional, and local empowerment to tackle disasters. Hence, the growing trend of empowering intergovernmental cooperation in disaster management is interesting to examine from the perspective of international relations.

In accordance with the HFA 2005, regional organizations are also strongly urged to establish their own frameworks for disaster management cooperation. According to Elizabeth Ferris and Daniel Petz (2013), there are 13 regional organizations working on their own frameworks for disaster risk reduction and management. International disaster management involves a large number of nations, including ASEAN members.

One motive seems to be positive: in today’s international politics, regionalism plays an important role in effectively bridging the international and national systems (Ferris and Petz 2013). Regionalism has also moved from hard politics to more specific issues. The group of scholars who believe in Functionalism Theory argue that more sectorial cooperation is needed to achieve even deeper regional identities. For example, by cooperating in combating common problems, the member states of a region can learn that there are more advantages to cooperation than conflict. This leads to a decrease in military conflict. A reduction in military conflict means more space for peace, which could lead to regional stability, the fortunate condition that is a requirement to further nurture economic development. While interactions through trade and cultural exchange are intensified, at the end of the day the feeling of belonging (togetherness) with each other becomes stronger.

Nevertheless, conventional or rational motives per se (as suggested by realism and liberalism) may not explain the specific reasoning of different regions with regard to their socio-political development. The trend of international disaster management may be explained globally by using both realist and liberal approaches, but it would be a generalization of problems as both schools neglect the importance of the idea and normative reasoning beyond cooperation in disaster management. From the perspective of international relations, it is necessary to answer certain questions about states’ behavior: Why are different nations doing the same thing? Furthermore, what makes them do it in a similar span of time? Both realists and liberals might be unable to answer the questions because they require material proof. For example, does the number of disasters necessarily have to increase within the last two decades in every region in the world to meet the requirement of rational justification?

Meanwhile, the more developed form of neorealism as suggested by its main advocate, Kenneth Waltz, is not sufficient to predict the trend of regionalism in Southeast Asia. Nuanced by the Cold War international structure of bipolarism, the neorealist perspective believes that the international structure is anarchic and that therefore states tend to behave according to their own interest and rely on the unequal capacity of power (Waltz 1988). The neoliberal approach might touch the whole picture of international politics, relying on millions of lobbies and interests. The corresponding interests are interwoven into a complex interdependent structure of international politics (Keohane and Nye 1989). However, neoliberalism cannot detach the focus of analysis from state interest and does not deny the anarchic nature of international politics. Neoliberals believe in international institutionalism, but like neorealists they believe in a positivistic way of analyzing the state system.

Meanwhile, regionalism in Europe shows that it is more than a state’s interests that determine the behavior of states in international politics. There are many other variables, such as identity, discourse, and norms, that can be manifested in deeper regional integration. This success is echoed through other regional endeavors to deepen ties beyond state boundaries through normative means, including in Southeast Asia. Both neorealism and neoliberalism hence fail to explain the paramount importance of those variables. On the other hand, constructivism emanated as an alternative to further understand the ignored variables, such as the importance of norms in international politics.

Hence, this paper aims to understand the institutionalization of regional and international cooperation in disaster management by using a constructivist approach for a specific region. The main reason for using this alternative approach is that the other conventional approaches fail to explain why such a trend occurs globally during the same period of time. This paper can contribute to understanding the matter from a Southeast Asian perspective. Instead of picking the global stage, this paper attempts to understand regional disaster management cooperation by examining the case of ASEAN to find how the norms of regional disaster management have been introduced, socialized, demonstrated, and internalized as one of the normative drives for ASEAN member states.

I-3 Literature Review and Methodology

This sub-section explains the constructivist approach used in this paper as the most suitable approach to understand the development of regionalism in Southeast Asia as part of the debate in international relations between constructivism versus the positivistic approaches of realism, liberalism, and their variants neorealism and neoliberalism.

According to Martha Finnemore and Katheryn Sikkink, constructivism posits that there are factors other than state interests that influence a state’s behavior (Finnemore and Sikkink 1998). For example, a democratic state tries to shape its foreign policy according to democratic principles. Foreign policy could be driven by several factors, such as identity, norms, or discourse. How do global norms influence ASEAN? The general definition of a norm is a standard appropriate behavior with a given identity. Norms promote justification over action and embody a quality of moral “oughtness” (ibid., 892).

Two norm life cycle works are examined in this sub-section to illustrate how the theoretical framework is used to explain the spread of new international norms. The first work, by Sakiko Fukuda-Parr and David Hulme (2011), focuses on the international level, while Birgit Locher (2003) focuses on a regional-level case study in the European Union.

Fukuda-Parr and Hulme assert that Finnemore and Sikkink’s norm life cycle is a valuable tool to understand the evolution of complex international norms (Fukuda-Parr and Hulme 2011, 29). They successfully map the journey of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) from formulation to introduction by the UN. They show the dynamics within the formulation. There was a norm marketing strategy and even ideological battle within the formulation of the MDGs, but there is also a limitation to using this method according to Fukuda-Parr and Hulme. It cannot be used to understand why the norm life cycle is relatively fast during the process of emergence but rather slow in implementation.

Locher’s work indicates that the norm life cycle is sufficient to understand the extension of international norms into regionalism. The case against trafficking of women in the EU is an attempt to demonstrate Finnemore and Sikkink’s framework for solving the puzzle of EU policy making. The extension of international norms to the regional level in the case of the EU is possible only if there are “political opportunity structures” resulting from the deepening of regional integration (Locher 2003). In the case of ASEAN, regional disaster management cooperation could also be linked with the success story of the deepening of ASEAN by the establishment of the ASEAN Charter.

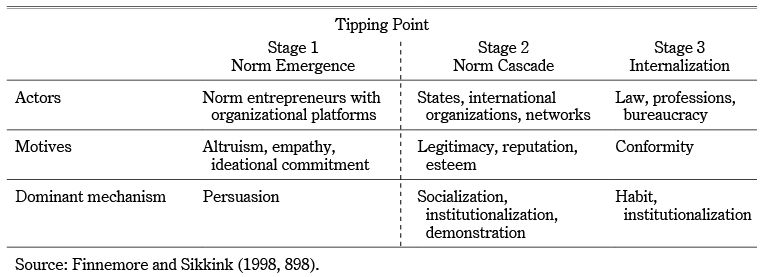

The norm life cycle can be described as a tool to understand a pattern of influence. It is divided into three stages. Between the first and second stages there is a critical point that is very important in determining when state actors start to adopt the norms (see Table 1).

Table 1 Stages of Norm Life Cycle

I-3-1 Norm Emergence

The first stage is characterized by the motive of persuasion. Norm entrepreneurs work to persuade or influence a critical mass of national leaders to adopt a new norm (Finnemore and Sikkink 1998, 895). One well-known example of a norm entrepreneur is Henry Dunant of the Red Cross. Organizational platforms could also have a certain characteristic that makes them suitable to play the same role. According to Finnemore and Sikkink, the UN has certain bodies that influence state leaders to promote specific ideas (ibid., 899).

The tipping point is where a norm reaches sufficient critical mass. This means the norm entrepreneurs have successfully persuaded state leaders to adopt the new norm. According to Finnemore and Sikkink, it should reach one-third of the total number of states (ibid., 901). The other way to measure this critical mass is by examining which important states adopt the new norm. The more powerful and influential an adopting country is, the more likely it is to influence critical mass compared to a small country (ibid.).

I-3-2 Norm Cascade

The second stage is characterized as dynamic imitation. This means that state leaders are already convinced and are now trying to influence other states to also follow the norm (ibid., 895). Cascading an idea means that the population is about ready to accept the new idea due to pressure for conformity, to gain international legitimacy, or because the political leaders are pursuing self-esteem and are therefore promoting this new idea to the people and their counterparts.

I-3-3 Internalization

If an idea is already well recognized, the newly formulated norm has started to be internalized. People and actors with different interests are less likely to challenge the importance of the idea. State leaders are willing to obey agreements regarding this norm. Regional or international actors are therefore bound by the necessity to comply. The other word to describe this behavior is “habit.”

II Analysis

For the analysis, this paper uses data collected from interviews conducted with ASEAN bureaucrats: at the ASEAN Secretariat with Neni Marlina of the DMHA Division and Rio Augusta and Asri Wijayanti of the AHA Centre in Jakarta in July 2013; and the deputy secretary general of ASEAN, Dr. A. K. P. Mochtan, in October 2014. This paper has been greatly influenced by the works of Finnemore and Sikkink on the international dynamics of norms, the experiences of ASEAN bureaucrats through William Sabandar’s “Cyclone Nargis and ASEAN: A Window for More Meaningful Development Cooperation in Myanmar” (2010), and Ferris and Petz’s In the Neighborhood: The Growing Role of Regional Organizations in Disaster Risk Management (2013).

II-1 Norm Emergence in International/Regional Disaster Management

The very foundation of norm development is the necessity to govern. Modern history is filled with progress as well as calamities. The necessity to govern responses during calamities is the origin of disaster management. As suggested by Damon P. Coppola, as the world witnessed the horrors of World War II states were beginning to organize civilian protection; the concern was not natural disasters at that time. This wartime civil defense is the origin of disaster management (Coppola 2011). As for how the idea of disaster management was developed further at the international level, the role of the United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNSIDR) in the 1980s was critical to creating the tipping point. Meanwhile, to introduce the advanced idea of regional disaster management into Southeast Asia in the 1990s, donors and dialogue partners engaged with ASEAN.

II-1-1 The Norm Entrepreneurs: States Involved in Wars

Coppola mentions no specific individual who had the most important role in building the new idea of international and regional disaster management. Instead, he suggests that states initially introduced the idea of civil defense. During this early period, the term “disaster management” was not well known. Coppola observes that the idea of global standards and organized efforts to manage disaster emerged only in the middle of the twentieth century (ibid., 4). It was correlated with the institutionalized mechanism of civil defense in the post-World War II period.

Prior to World War II the idea of disaster management was largely unknown. After the war, governments with experience in facing war played an important role in the formulation of civil defense. There were no comprehensive national disaster management authorities as we know them today, but the system was reinforced with legal frameworks to provide authority and budgeting during the 1950s and 1960s. According to Enrico Quarantelli (1995), these civil defense units later evolved and formed more comprehensive disaster management organizations (Coppola 2011, 5). This process of evolution can be seen in the following examples. In Britain, the Civil Defence Act of 1948 evolved into Great Britain’s multilayered disaster management system, which included the involvement of local authorities, the Strategic Coordination Centre, the Civil Contingencies Secretariat, and the Cabinet Office Briefing Room. In Canada, the Canadian Civil Defence Organization, which was established in 1948, is the foundation of Canada’s Office of Critical Infrastructure Preparedness and Emergency Preparedness. In the United States, the Federal Civil Defense Act of 1950 led to the creation of the Federal Emergency Management Agency. In France, the Ordinance of 1950 and the Decree Relating to Civil Defense of 1965 formed the basis for the Direction de la Protection et de la Sécurité de la Défense, which is administered by the Ministry of Interior. Algeria’s Direction Générale de la Protection Civile is rooted in the 1964 Decree on the Administrative Organization of Civil Defense.

Nevertheless, Coppola observes that there was another motive for the creation of disaster management agencies, particularly in countries that established their disaster management in the 1970s. This other motive was responding to the pressure of popular criticism of governments’ poor disaster management, for example in Peru in 1970, Nicaragua in 1972, and Guatemala in 1976 (ibid., 6). The first attempt in Southeast Asia also occurred during this decade. Yasuyuki Sawada and Fauziah Zen argue that disaster management in ASEAN was conceived in 1976 (Sawada and Zen 2014). Meanwhile, Lolita Bildan’s report also points out that among the earliest domestic disaster management bodies established in Southeast Asia are the Philippines’ National Disaster Coordinating Council in 1978 and the Indonesian BAKORNAS PBP in 1979 (Bildan 2003). We may say that these countries were in the second wave of disaster management emergence.

From Coppola’s examination we can conclude that although disaster management agencies are within the authority of the national polity, there were two patterns in the emergence of these agencies. The first pattern dated to the postwar era and was dominated by more developed nations such as the United States, France, and Great Britain, while the second wave was started in the 1970s mostly in developing countries such as Peru, Nicaragua, Indonesia, and the Philippines. This phenomenon illustrates the mirroring of an idea from one country to another, especially through assistance from developed countries to developing countries. This means that as more countries tried to establish disaster management bodies, they learned and adopted the best practices from other nations. From this interrelated learning process, global standards of disaster management were created.

Within ASEAN, the group of experts on disaster management was established in 1971. This group, called the Experts Group on Disaster Management (AEGDM), is viewed as the pioneering body in the region and was behind the acknowledgement of disaster issues in the ASEAN Concord of 1976. This group is no longer active, but it acted as the norm emergence agent within the region. Until the first decade of the twenty-first century, its status did not noticeably improve. With the support of foreign actors such as the Directorate-General for European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (ECHO), formerly known as the European Community Humanitarian Aid Office, it successfully sustained the effort to mainstream the idea of institutionalizing regional disaster management (ibid.). During AEGDM’s early period, its role was to establish a non-binding document that would later serve as the basis for regional cooperation.

There have been several attempts to elevate the status of disaster management cooperation in ASEAN. In the AEGDM’s 11th meeting in Chiang Rai, there was a proposal to elevate its status to the ASEAN Committee or the Senior Officials Meetings with the obligation to report to the ASEAN Standing Committee or to the ASEAN Ministerial Meeting (Sawada and Zen 2014). However, ASEAN cooperation on disaster management did not really gain momentum until the successful operations for the Indian Ocean earthquake in 2004 and Myanmar’s Cyclone Nargis in 2008, when ASEAN and the international community found a way to cooperate.

Since the 1990s, more developed countries have been involved in helping with Southeast Asian efforts to strengthen disaster management norms. Based on previous research, ASEAN donors and dialogue partners such as the European Union, United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Japan-ASEAN Integration Fund (JAIF), and NGOs such as Oxfam continuously encouraged Southeast Asian countries to introduce best practices for disaster management. As in the case of the MDG norms (Fukuda-Parr and Hulme 2011) and the anti-trafficking of women norms in the EU (Locher 2003), the motivations of actors in the first stage of norm emergence were varied. In the case of disaster management in ASEAN, there were two scopes of cooperation. The first aimed to develop better domestic disaster management institutions, and the second to establish country-to-country cooperation in disaster management. The development of domestic disaster management agencies is important, because without them it is less likely that Southeast Asian countries can engage in any international or regional cooperation. Listed by Bildan (2003), among the donors and dialogue partners who engaged with Southeast Asian countries were USAID, the Danish International Development Agency (DANIDA), and ECHO.

The main function of USAID is to achieve US foreign policy goals by providing economic, humanitarian, and development assistance for the people of developing countries. In the case of ASEAN disaster management, USAID founded the Asian Urban Disaster Mitigation Program in 1995. The program was responsible for the following: (1) engaging Cambodia by introducing community-based flood mitigation preparedness; (2) engaging Indonesia with an earthquake vulnerability reduction program; (3) engaging Lao PDR by establishing an urban fire and emergency management program; (4) engaging the Philippines by working on flood and typhoon mitigation; (5) cooperating with Thailand in risk assessment and mitigation planning; and (6) working with the Vietnamese by sharing disaster-resistant housing best practices. Through these programs, USAID engaged six Southeast Asian countries and socialized them to the idea of disaster management. Another important scheme carried out by USAID is the Extreme Climate Events Programme, as reported by Bildan (2003, 13). The program began in 1999 and was funded by USAID’s Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance. Through this program, the application of climate information toward disaster management in three countries—Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam—is illustrated through training for capacity building and demonstration. Lastly, USAID funded the Program for Enhancement of Emergency Response in 1999. The program focused on building capacity in Indonesia and the Philippines, especially for urban search and rescue, medical response, and hospital preparedness for emergency response (Bildan 2003).

DANIDA started a program for less-developed countries in Southeast Asia in 2001. Through the Disaster Reduction Programme for Cambodia, Lao PDR, and Vietnam, DANIDA focused on the development of short- and medium-term frameworks for community public awareness programs in Cambodia and Vietnam and the development of disaster awareness teaching materials for elementary schools in Lao PDR (ibid.).

The European Union works closely with Southeast Asia through ECHO, a global collaboration that the EU initiated in 1996 via the Partnerships for Disaster Reduction–South East Asia, which aims to train disaster management practitioners in Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, the Philippines, and Vietnam and facilitate capacity building for community-based disaster management. ECHO also assisted the oldest disaster management expert group in the region, AEGDM. Acknowledging that AEGDM was the norm entrepreneur inside ASEAN, we can conclude that ECHO aimed to support ASEAN in building its own regional disaster management architecture.

Those initial programs played an important role in bringing norms of disaster management into Southeast Asia. Experienced dialogue partners introduced regional disaster management to ASEAN in two waves: the first wave of cooperation was to build state national disaster management offices. The second wave of cooperation was to build state-to-state disaster management cooperation in the region.

II-1-2 Organizational Platforms: UNISDR, International and Regional Organizations

According to Coppola, there are some milestones at the international level in the evolution of disaster management. One of the most important events was the United Nations General Assembly declaration of the 1990s as the International Decade for Natural Disaster Reduction (IDNDR). The action was aimed at promoting internationally coordinated efforts to reduce losses caused by natural disasters. The United Nations declared this campaign in 1987 and supported it through UN Resolution 44/236, which promoted better disaster management practices globally and encouraged national governments to improve their performance in disaster management (Coppola 2011, 6–7).

The second milestone was the Yokohama Strategy–Global Recognition of the Need for Disaster Management (ibid., 7–9). The Yokohama Strategy was approved by the UN member states in 1994 at the World Conference on Natural Disaster Reduction. This conference was held to evaluate the progress of the IDNDR. There are some important points of the Yokohama Strategy that we can use to understand the formulation of international disaster management, such as in articles 4 and 7.g, where it states that the world is increasingly interdependent and that regional and international cooperation will significantly enhance the ability to respond to disaster (HFA 2005).

These two points of importance are a call to promote further regional and international disaster management, as we recognize that we are living in an interdependent world and better coordination is needed to tackle disasters, which do not respect borders. To further sustain the efforts, IDNDR and the Yokohama Strategy were followed by the setting up of the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR). The main role of UNISDR is to guide the international community in disaster management (ibid., 12).

Entering the twenty-first century, international organizations launched some programs in Southeast Asia in parallel with their efforts at the international level. Among the notable actors named by Bildan (2003) are the Asian Disaster Reduction Center (ADRC), the Asian Disaster Preparedness Center–Regional Consultative Committee on Disaster Management (ADPC-RCC), and the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UN ESCAP) Typhoon Committee. Established in 1998, ADRC supports Southeast Asian countries mostly through socialization and information sharing on disaster reduction mechanisms. The ADPC-RCC, established in 2000, focuses on capacity building for national disaster management offices (NDMOs), including those in Southeast Asia. Meanwhile, since July 2001 the UN ESCAP Typhoon Committee has been assessing the technology required for mitigation and preparedness, serving as an information and education provider, and developing communication networks in Southeast Asia.

Complementing the efforts of international organizations are Southeast Asian regional bodies. One example is the ASEAN Regional Forum Inter-Sessional Meeting on Disaster Relief, which was established in 1993. Although this forum was not very active in the past, at its fourth meeting in May 2000 the body agreed on the idea of socialization and capacity building for better regional disaster management. As noted by Bildan (2003), there was agreement on the following: (1) information sharing of disaster data and early warning; (2) mutual assistance for disaster preparedness and relief; and (3) training in disaster management and promotion of greater awareness in disaster preparedness and relief. The key word for this program is socialization. At the subregional level, associated with Southeast Asian Indochinese countries, there is also the Mekong River Commission, which is working on flood management and mitigation strategy.

It should be noted that not all cases of regional cooperation are success stories—for instance, ASEAN experienced a failed attempt to integrate haze pollution into disaster management. Although ASEAN regional cooperation in tackling transboundary haze pollution started in 1995, it ran into several political obstacles. Malaysia and Singapore protested against Indonesia for the haze pollution produced from forest fires in Borneo, particularly after the 1997 fires there. Until the first decade of the twenty-first century the tension rose, since there was no settlement agreed upon between the three countries.

In the beginning, Malaysia and Singapore benefited from the continuous bilateral pressure on Indonesia. Indonesia initially preferred to discuss the matter with Malaysia and Singapore at a subregional ministerial meeting in Riau instead of bringing the issue to be fully resolved under the ASEAN mechanism (Tan 2005). But due to political considerations, ASEAN established its own legal umbrella for transboundary haze pollution, which is the ASEAN Agreement on Transboundary Haze Pollution signed in 2002 (ibid.).

The issue of transboundary haze pollution deserves elaboration. It is true that the national interests of member states may clash with regional endeavors to regulate a particular conflict. However, this case shows the weakness of neorealism theory in predicting the trend of ASEAN regionalism. Neorealism believes that the international structure is anarchic (Waltz 1988, 618). Using the logic of neorealism, Singapore and Malaysia would prefer to use the variables of unequal state capacity (by which they would benefit) and defect from the regional architecture. However, as issues and negotiations develop, governments rely on the formation of regional normative tools to ensure the implementation of cooperation.

Formal regional attempts to tackle transboundary haze pollution began with the signing of the ASEAN Agreement on Transboundary Haze Pollution in 2002. This agreement requires ASEAN member states to actively monitor and prevent activities that may lead to forest fires. The agreement also endorses regional cooperation in the form of joint monitoring of such activities. Although the agreement was signed by ASEAN member governments in 2002, the ratification process was hindered by domestic politics, especially in Indonesia. Malaysia and Singapore were the first two nations to ratify the agreement, in December 2002 and January 2003 respectively, while the ratification process in the Indonesian parliament was impeded until 2007 (Haze Action Online 2015). This prolonged process of ratification worried Malaysia and Singapore because the haze produced from Indonesian forest fires frequently carried over into their territory.

The inability of the regional organization to mediate the negotiation and give satisfying closure would create distrust toward regionalism. It could have caused Malaysia and Singapore to voluntarily defect or withdraw. However, the conflicting parties were willing to give the regional mechanism a chance. Strategic sequential measures (or rather positive tit for tats) were launched by Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore. In the absence of the implementation of the ASEAN Agreement on Transboundary Haze Pollution, the new Indonesian administration preferred a subregional negotiation. ASEAN then facilitated a subregional ministerial steering committee in 2006 as a forum to assist Indonesia. Malaysia and Singapore responded by joining in together with Brunei Darussalam and Thailand. To respond to the goodwill, the Indonesian government invited Malaysia and Singapore to assist Indonesian provinces that were prone to forest fires. Both countries responded well: Singapore signed a collaboration agreement with Jambi Province, which lasted from 2007 to 2011; and Malaysia signed a collaboration agreement with Riau Province in 2008 (National Environment Agency, Singapore 2016). The sequential give and take of political negotiations during this period was important to build trust within the regional framework despite the absence of an agreement.

The ASEAN subregional arrangement was continuously implemented through frequent subregional ministerial meetings. There were 16 subregional meetings from 2006 to 2014. The Indonesian parliament finally ratified the ASEAN Agreement on Transboundary Haze Pollution on October 14, 2014 (Aritonang 2014; Haze Action Online 2015). It took 12 years to build trust among these three neighboring countries. At the moment, the process of combating transboundary pollution is managed multilaterally under ASEAN regionalism. This finding opposes the argument that anarchic bilateral pressure works best. Using the constructivism framework allows for predictability in analyzing how the traveling of norms affects regionalism. The framework helps us understand when and how international norms influence regionalism in accordance with universal values. This method can be applied to analyze various cases in different regions. There is potential for supranational governability of transboundary pollution since the 10 member states agreed on the ASEAN haze monitoring system in October 2013. Hence, the predictability of the constructivist approach (i.e., international norm dynamics) is beneficial for analyzing the trend of regionalism.

II-1-3 The Tipping Point

The idea of international disaster management did not reach the tipping point until most of the world’s countries recognized its importance. This paper argues that the most important event that could be defined as a tipping point was the HFA in 2005, which came about as a result of the World Conference on Disaster Reduction held in Kobe on January 18–22, 2005. The HFA is an international effort to encourage national governments to strengthen the institutional basis for implementation of disaster risk management and to integrate it into sustainable development policy. The HFA has directly influenced ASEAN to pursue its own regional disaster management cooperation. It should be noted that the HFA is referred to as an international strategy for disaster management and the ASEAN legal framework acknowledges the importance of this framework as the basis of Southeast Asian regional cooperation on disaster management.

Coppola highlighted the magnitude of this conference by showing that there were more than 4,000 participants, with 168 governments represented out of about 195 countries in the world in 2005. A total of 78 specialized UN agencies participated, along with 562 journalists from 154 media corporations, and the conference attracted more than 40,000 visitors (Coppola 2011, 13). According to Finnemore and Sikkink, to reach the tipping point, no less than one-third of the world’s state number (33.33 percent) needs to recognize the importance of newly established international norm (Finnemore and Sikkink 1998, 901). Based on the number of countries that participated in the conference, we can conclude that 86.15 percent of states recognized the necessity for international disaster management. This means the tipping point was reached globally. Regionally, the tipping point was reached with the signing of the AADMER on July 26, 2005 in Vientiane, Laos, only six months after the signing of the HFA. The AADMER was signed by all ASEAN member states, which consist of all Southeast Asian countries except for Timor Leste.

II-2 Norm Cascade

In the norm cascade, states try to persuade other states through socialization and demonstration. In this case, ASEAN states were influenced to adopt the norms and to build a feeling of belonging to the international community. In this stage, leaders who have already been convinced about the new disaster management norms try to influence other leaders. Three possible motives are: (1) to provide pressure for conformity by asking the member states to implement the agreement; (2) to gain international legitimacy; and (3) to pursue self-esteem.

This paper has pointed out several important actors that were influential in promoting ASEAN regional disaster management cooperation. Among the strong supporters of this regional mechanism was then-ASEAN Secretary General Dr. Surin Pitsuwan. He served as the secretary general from 2008 to 2012. During the early part of his term, Southeast Asia was hit by a major calamity in Myanmar. Assisted by William Sabandar, the then-special envoy of the ASEAN Secretary General for the post-Nargis recovery in Myanmar, and field officers led by Adelina Kamal, Pitsuwan succeeded not only in uniting ASEAN behind Myanmar to deal with Cyclone Nargis, but also through his dispatched assistance team he proved that the ASEAN-led mechanism worked in the field and technical operations.

As reported by Anik Yuniarti, Pitsuwan proudly claimed that AADMER was the fastest ASEAN agreement to be negotiated and accepted by all of the member states—it took only four months (Yuniarti 2011, 25). Pitsuwan’s optimistic tone is worth examining. The way the ASEAN secretary general proudly claimed the success of disaster management cooperation could be regarded as a way to gain esteem and reputation. We also understand that Pitsuwan proposed the idea of a more progressive ASEAN during his term as Thai foreign affairs minister. During his term, he proposed the ideas of flexible engagement in 1998 and forward engagement in 2003 to challenge the traditional conception of the ASEAN way (Katanyuu 2006). “Flexible engagement” was an idea proposed to make ASEAN more critical of unsavory practices in Myanmar under the military junta. This proposal was rejected by the other member states back in 1998. However, Pitsuwan in his capacity as Thai foreign affairs minister unilaterally launched the policy of forward engagement in 2003. This policy was designed to pressure Myanmar to proceed with the road map to democracy. This implies that Pitsuwan was among the progressive diplomats in the region.

Under his leadership, ASEAN also achieved consensus in signing the ASEAN Charter and establishing the ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights. From what we have learned about his background, Pitsuwan himself believed in a more progressive ASEAN. His perspective shaped his style of leadership to be more open toward the international community, endorsed open and frank discussion, and aimed to gain ASEAN more legitimacy. As for the involvement of ASEAN in Myanmar in 2008, he argued for responsibility to protect, as he stated in his speech at the Asia-Europe Summit in Beijing on October 24, 2008.

The other motive involves the state as an actor. For example, under its period of chairmanship in 2011, Indonesia built a facility for ASEAN disaster response on its own initiative, located in West Java. This was initiated by Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono during the session of the ASEAN-Japan Special Meeting in the ASEAN Secretariat on April 9, 2011 (Yuniarti 2011, 29). According to this author’s interview with the AHA Centre representative, the Indonesian government also fully supported the establishment of the AHA Centre, which is located in Jakarta. This regional disaster management operating body was established in November 2011. The Indonesian government provides the facility for the AHA Centre, integrated into the infrastructure of the Badan Pengkajian dan Penerapan Teknologi (Agency for the Assessment and Application of Technology). The development of the AHA Centre was supervised by the coordinating minister for people’s welfare, Agung Laksono, who routinely monitored the progress of the project.

These Indonesian attempts were informed by the country’s motive of gaining legitimacy and esteem as one of the most influential ASEAN member states. This was in accordance with Indonesia’s efforts to promote deeper ASEAN regionalism. Since its democratic transition in 1998, Indonesia—together with Thailand and the Philippines—has become more vocal in supporting a democratic ASEAN. In the Bali Concord II of 2003, Indonesia for the first time introduced the terminology of democratization in an ASEAN document. It also launched the Bali Democracy Forum to further spread the idea of a more democratic regional sphere.

ASEAN’s success in cascading the norms of regional disaster management cannot be separated from the successful mechanism of linking issues. Borrowing the terminology proposed by Fukuda-Parr and Hulme, as a “supernorm,” disaster management cooperation is closely linked to global normative shifts such as the issues of human rights, political openness, and democratization. Deeper ASEAN regionalism has resulted in newly established bodies dealing with nontraditional issues, as exemplified by the establishment of the Disaster Management and Humanitarian Assistance Division, the AHA Centre, and the ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights. At the operational level, disaster management and humanitarian assistance cannot be separated from the issue of political openness. If ASEAN cannot make an agreement with all of the member states, any joint operation will not succeed. For example, if diplomatic trust among ASEAN member states is not high, it is less likely that the involvement of foreign military personnel will be welcomed. To help build trust regarding military involvement in regional disaster response, ASEAN has initiated the collaboration of civil-military actors in disaster management and humanitarian assistance operations since 2005. Through annual regional disaster response exercises, ASEAN member states gain a better understanding on how to coordinate joint civil-military operations in a regional operation. This could reduce suspicion among member states.

Involving the military in regional disaster management could also help ASEAN countries redefine the purpose of the armed forces. The challenge to proportionally reposition the function of the military is urgent in several countries, such as Thailand and Indonesia. In Thailand 19 military coups d’état have been launched to date, indicating that the military has constantly attempted to get involved in domestic politics. Reformed Indonesia also has had the same problem of military political involvement in the past. In the Reformation era, the repositioning of the military to make this institution more professional includes introducing international peace building and other nontraditional operations. With this new mechanism created by ASEAN, the governments have found a forum to exercise their interests. It can be said that cooperation on disaster management has led ASEAN to establish deeper mechanisms, such as the use of military assets in “joint operation[s] other than war” (ibid., 16). The use of military assets and personnel to deal with disaster management was discussed by the defense ministers of ASEAN member states in Vietnam on October 7, 2010, followed by another meeting in Jakarta in 2011. Workshops for the representatives of all member states’ military forces on the use of ASEAN military assets and capacities in humanitarian assistance and disaster relief were held by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Indonesia on October 7–8, 2010 (ibid., 27). These workshops produced the standard operating procedure for ASEAN’s disaster response, in which military personnel from ASEAN member states are allowed to contribute to disaster response—although there are some limitations, such as different administrative mechanisms to accept foreign military assets within other countries’ borders and creating an extra budget to establish this mechanism. The most important thing to be highlighted is the willingness of member states to nurture healthier civil-military relations. The presence of foreign military personnel in cases of disaster relief should not be overreacted to, because their presence is for the sake of humanitarian operations (ibid., 28). Responses from the Indonesian side collected by Yuniarti were also positive, and Lembaga Ilmu Pengetahuan Indonesia (Indonesian Institute of Science) claimed that the aid from foreign military forces for Aceh had gradually reduced ideological suspicions while Syiah Kuala University also noted that the mechanism to include the military was successful in Aceh (ibid., 29). With the aid from foreign military forces for Aceh gradually reducing suspicions, the international community is no longer divided by ideology (ibid.).

II-3 Internalization

The final stage of new norm installation is the internalization process, when states in Southeast Asia have no further obstacles to implementing cooperation on disaster management. There are legally binding documents, and ASEAN member states willingly comply with the agreement. The AADMER and the ASEAN Standard Operating Procedure for Regional Standby Arrangements and Coordination of Joint Disaster Relief and Emergency Response Operations (SASOP) outline the actors responsible for regional disaster management within, associated with, and collaborating with ASEAN, such as NGOs and donors, since the establishment of AADMER. This means the internalization of regional disaster management in ASEAN can be examined in its implementation.

ASEAN regional disaster management cooperation is now supported politically. According to ASEAN Deputy Secretary General A. K. P. Mochtan, disaster management cooperation in ASEAN is considered an important tool to further nurture solidarity. According to this high-ranking ASEAN bureaucrat, cooperation is growing fast due to three important factors. First, cooperation is a less sensitive matter than issues such as democratization, corruption, and human rights. Second, the ASEAN members view disaster management as the necessity to act quickly at critical moments. Third, ASEAN needs a tangible result to showcase the progress of the Southeast Asian regional framework. Hence, the deployment of ASEAN missions into disaster-affected areas is important.

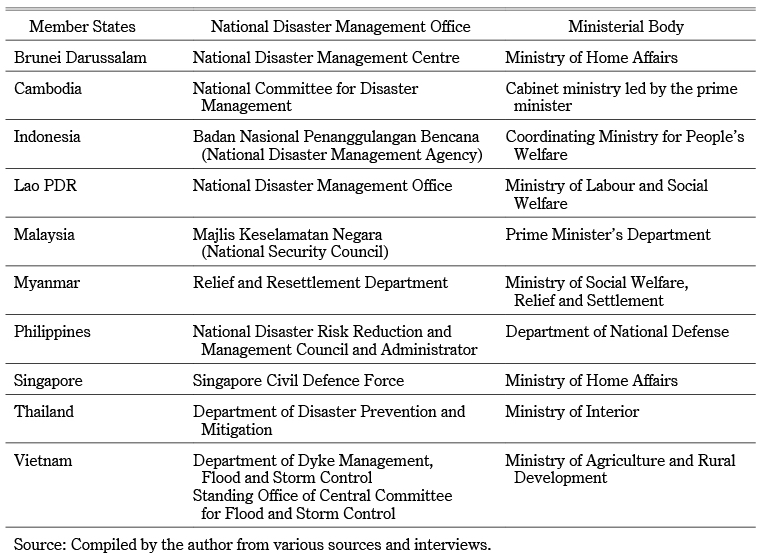

The internalization of ASEAN cooperation can be noted also in the exchange of projects in the NDMOs. NDMOs are the official bodies responsible for disaster management and risk reduction within member countries. They vary in terms of organizational structure, but under the AADMER they work together within the framework that has been set by ASEAN. Therefore, although they are primarily domestic actors, under the ASEAN mechanism they are also regional actors, since they send representatives to the ACDM and collaborate through the assistance of the AHA Centre in cases of field assistance deployment. Although they vary in form and legal framework (see Table 2), they have been working closely to build their networks since November 2011.

Table 2 List of NDMOs in ASEAN Countries

To help ASEAN member states implement effective cooperation, ASEAN established two operating arms: the DMHA Division (Disaster Management and Humanitarian Assistance Division) and the ASEAN Coordinating Centre for Humanitarian Assistance for disaster management (AHA Centre). The ASEAN Secretariat works to facilitate dialogue and serve as the bureaucracy for the implementation of AADMER. Before the AHA Centre was established, the DMHA Division also served as the operational body for field operations. Nowadays there are incremental transfers of roles, such as in mid-2013, when tasks related to disaster response, operations, and capacity building were transferred to the AHA Centre. The DMHA Division also has transferred the administration of the ASEAN Disaster Risk Reduction Portal (DRR Portal) to the AHA Centre. Nevertheless, the division still functions as the custodian of disaster response funds and monitored the balance scorecard for the implementation of the 2010–15 work plans. Therefore, the DMHA Division acts as the bureaucratic arm with the task of monitoring conformity. The AHA Centre is the operating arm of ASEAN cooperation in disaster management and risk reduction. Since its establishment in 2011, the AHA Centre has been involved in major natural disasters such as the Thailand floods of 2011–12, Typhoon Bopha in the Philippines in December 2012, response preparation on the eve of Myanmar’s Cyclone Mahasen in May 2013, the Aceh-Indonesia Bener Meuria earthquake in July 2013, and Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines in November 2013.

The AHA Centre also operates a yearly regional exercise called the ASEAN Regional Disaster Emergency Simulation Exercise (ARDEX) as the platform for member states and different actors to collaborate in a simulation. ARDEX involves NDMOs, search and rescue teams, and the military personnel of member states. All of these mechanisms were developed by the AHA Centre to ensure the smoothness of regional cooperation by making it habitual and internalized.

An interesting finding is that help from donors and dialogue partners continues up to today. They support the fund under the larger framework of the ASEAN master plan for connectivity. I was informed by Mochtan that he was still helping ASEAN to maintain cooperation with JAIF. JAIF has been donating funds and material since its establishment, including the real-time early detection warning system for the AHA Centre. This information was previously confirmed by the communication officer of the AHA Centre, Asri Wijayanti.

In the wider area of regional cooperation, ASEAN also drives the ASEAN Regional Forum Exercises (ARF DiRex), which involve not only the 10 member states but also their dialogue partners2) to ensure peaceful coexistence in the Pacific region. In 2015 alone, there were four meetings and agendas related to disaster management in the joint ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting and Defence Ministers of Dialogue Partners (ADMM-Plus).3) Among them was the ARF DiRex in Kedah, Malaysia, in May 2015.

Another important aspect is the involvement of the population in ASEAN regionalism. To endorse a more people-centered approach, ASEAN established the AADMER Partnership Group (APG). The APG is a consortium of international NGOs collaborating with ASEAN for the people-centered implementation of AADMER. The NGOs involved in this endeavor are Child Fund International, Oxfam, Save the Children, Mercy Malaysia, and Plan. The funding comes from the European Union Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection. This could help ASEAN promote activities for wider audiences in the region. According to my interview with ASEAN DMHA representative Neni Marlina in July 2013, the ASEAN Secretariat welcomes such progressive ideas. The motives range from socialization and education to the internalization of the idea of regional disaster management.

III Conclusion

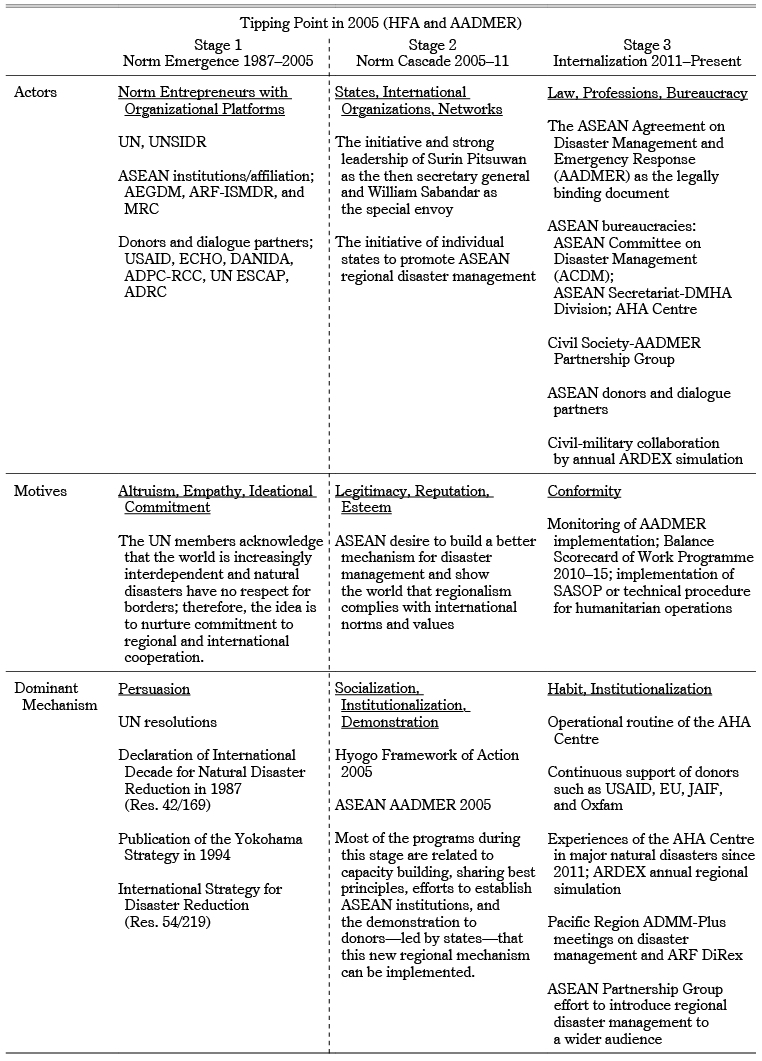

Through the analysis in this paper, I have answered the question of why there is a trend of regional organizations establishing disaster management cooperation mechanisms: the reason is strong global advocacy. The move to establish the supernorms of international/regional disaster management has successfully traveled from the norm entrepreneur to the international stage through introduction, socialization, and persuasion mainly by international organizations. The dominant mechanism to introduce and persuade state leaders in the norm emergence stage is the top-down approach, using the UN as an organizational platform for entrepreneurs. Hence, the genealogy of an internalized idea can be traced back to UN resolutions as the basis for global cooperation. The roles of UN resolutions and UNSIDR were important in bringing the idea to the tipping point in 2005, followed by the Southeast Asian tipping point which also reached the ASEAN region in 2005. This means that advocacy during the norm emergence stage was diffused in parallel at the international and regional levels, as we can see in Table 3. We can also conclude that in terms of the regional/international disaster management idea, the function of international organizations is pivotal.

Table 3 International/ASEAN Regional Disaster Management Supernorm Life Cycle

To sum up the findings, regional disaster management cooperation in ASEAN was successful only because there were certain facilitating factors: (1) continuous assistance from the international community; (2) the determined leadership of ASEAN; and (3) a proven regional mechanism as a result of the deepening of ASEAN regional cooperation.

First, most of the funding and initiative to introduce socialization and demonstration of disaster management in ASEAN was supported by foreign actors. Hence, there was strong international advocacy for spreading the global normative shift. Since the 1990s there has been continuous engagement by international organizations and dialogue partners in assisting Southeast Asian states to establish domestic national disaster management offices and improve regional disaster management cooperation. Donors have worked together with individual countries such as Cambodia, Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines, as well as giving assistance to the ASEAN Expert Group on Disaster Management. The collaboration created better opportunities for the future regional disaster management architecture. Some donors are still working with ASEAN in this sector.

Second, there was strong leadership from both ASEAN bureaucrats and state leaders. As demonstrated in this paper, the role of then-Secretary General Surin Pitsuwan and the current director of the DMHA Division, Adelina Kamal, was pivotal in determining the success of ASEAN operations during Myanmar’s Cyclone Nargis in 2008. State leaders such as Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono and Agung Laksono were also important in showcasing the political will to support the cause and indirectly convincing other ASEAN member states to join Indonesia in supporting regional disaster management cooperation.

Third, ASEAN has a proven regional cooperation mechanism. The importance of the momentum resulting from the Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami of 2004 and Cyclone Nargis in 2008 cannot be ignored. The former had a great impact on both HFA and AADMER reaching the tipping point in 2005. ASEAN involvement in Aceh to assist in the reconstruction and reconciliation process was a successful demonstration that the regional organization was capable of conducting field operations. Moreover, the Indonesian government was open to accepting the assistance of the international community. This showed the other ASEAN member states that there was no reason for them to be suspicious of ASEAN’s capability. Meanwhile, Cyclone Nargis in 2008 provided the motive for the AADMER to be put in force in 2009. ASEAN successfully deployed the humanitarian operation and facilitated the cooperation of the Myanmar government and international community. This success raised the confidence of ASEAN member states to further develop disaster management cooperation. Nevertheless, without the international dynamics of norms that illustrate the transfer of disaster management norms from entrepreneurs to the world and then to ASEAN, such a phenomenon cannot be clearly explained.

Accepted: March 7, 2016

Acknowledgments

My gratitude to Prof. Yuzuru Shimada for his invaluable advice in writing this article. I would like to appreciate the ASEAN Secretariat and AHA Centre for allowing me conducting research in their institutions.

Bibliography

Aritonang, Margareth S. 2014. RI Ratifies Haze Treaty. Jakarta Post Online. September 17.

http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2014/09/17/ri-ratifies-haze-treaty.html ASEAN, accessed on February 10, 2016.

ASEAN Agreement on Disaster Management and Emergency Response. 2012. Jakarta: ASEAN Secretariat.

Bildan, Lolita. 2003. Disaster Management in Southeast Asia: An Overview. Asian Disaster Preparedness Center.

Coppola, Damon P. 2011. Introduction to International Disaster Management. 2nd ed. Burlington: Elsevier.

Ferris, Elizabeth; and Petz, Daniel. 2013. In the Neighborhood: The Growing Role of Regional Organizations in Disaster Risk Management. Washington: The Brookings Institution, London School of Economics Project on Internal Displacement.

Finnemore, Martha; and Sikkink, Kathryn. 2001. Taking Stock: The Constructivist Research Program in International Relations and Comparative Politics. Annual Review of Political Science 4: 391–416.

―. 1998. International Norm Dynamics and Political Change. International Organization 52(4): 887–917.

Fukuda-Parr, Sakiko; and Hulme, David. 2011. International Norm Dynamics and the “End of Poverty”: Understanding the Millennium Development Goals. Global Governance 17(1): 17–36.

Haze Action Online. 2015. Status of Ratification. January 20. http://haze.asean.org/status-of-ratification, accessed on February 10, 2016.

Hyogo Framework for Action 2005–2015: Building the Resilience of Nations and Communities to Disasters (HFA). 2005. Geneva: United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction.

http://www.unisdr.org/2005/wcdr/intergover/official-doc/L-docs/Hyogo-framework-for-action-english.pdf, accessed on February 10, 2016.

Katanyuu, Ruukun. 2006. Beyond Non-interference in ASEAN: The Association’s Role in Myanmar’s Reconciliation and Democratization. Asian Survey 46(6): 825–845.

Katsumata, Hiro. 2004. Why Is ASEAN Diplomacy Changing? From “Non-Interference” to “Open and Frank Discussions.” Asian Survey 44(2): 237–254.

Keohane, Robert; and Nye, Joseph. 1989. Power and Interdependence: World Politics in Transition. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

Locher, Birgit. 2003. International Norms and European Policy Making: Trafficking in Women in the EU. Paper presented at Annual Meeting of the International Studies Association, February 26–March 1, 2003 at Centre for European Studies, Institute for Political Science, University of Bremen, Portland.

National Environment Agency, Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources, Singapore. 2016. Factsheet on Measures against Haze. April 4. http://www.nea.gov.sg/docs/default-source/corporate/COS-2016/ep1–updated—cos-2016-media-factsheet—thpa-and-green-procurement.pdf, accessed on February 10, 2016.

Quarantelli, Enrico L. 1995. Disaster Planning, Emergency Management, and Civil Protection: The Historical Development and Current Characteristics of Organized Efforts to Prevent and Respond to Disaster. Newark: University of Delaware Disaster Research Center.

Rum, Muhammad. 2009. ASEAN and the Environment Issues: Enhancing Regional Environmental Regime. Master Thesis at the Asia-Europe Institute, University of Malaya.

Sabandar, William. 2010. Cyclone Nargis and ASEAN: A Window for More Meaningful Development Cooperation in Myanmar. In Ruling Myanmar: From Cyclone Nargis to National Election, edited by Nick Cheesman, Monique Skidmore, and Trevor Wilson, pp. 107–207. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Sawada, Yasuyuki; and Zen, Fauziah. 2014. Disaster Management in ASEAN. ERIA Discussion Paper Series. Jakarta: Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia.

Sikkink, Kathryn. 1998. Transnational Politics, International Relations Theory, and Human Rights. Political Science and Politics 31(3): 516–523.

Tan, Alan Khee-Jin. 2005. The ASEAN Agreement on Transboundary Haze Pollution: Prospect for Compliance and Effectiveness in Post-Suharto Indonesia. New York University Environmental Law Journal 13 (3): 647–722

Waltz, Kenneth. 1988. The Origin of War in Neorealist Theory. Journal of Interdisciplinary History 18(4): 615–628.

Yuniarti, Anik. 2011. Penanganan bencana alam dalam wacana pembangunan komunitas ASEAN 2015 [Natural disaster response in the discourse of establishing ASEAN community 2015]. Bencana dalam perspektif hubungan internasional [International relations perspective on disasters], pp. 13–32. Yogyakarta: Jurusan Ilmu Hubungan Internasional, Universitas Pembangunan Nasional “Veteran” Yogyakarta.

1) Collected from direct interviews with ASEAN officers and official news disseminated by the AHA Centre.

2) Their dialogue partners are Australia, Bangladesh, Canada, China, the European Union, India, Japan, North Korea, South Korea, Mongolia, New Zealand, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, Russia, Sri Lanka, Timor Leste, and the United States.

3) The members were Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam, and the eight Plus countries: Australia, China, India, Japan, New Zealand, South Korea, the Russian Federation, and the United States.