Contents>> Vol. 6, No. 1

Indonesian Theosophical Society (1900–40) and the Idea of Religious Pluralism

Media Zainul Bahri*

*Department of Religious Studies, Syarif Hidayatullah State Islamic University of Jakarta, Jl. Ir. H. Juanda No 95, Ciputat-Tangerang Selatan, Banten, Indonesia

e-mail: zainul.bahri[at]uinjkt.ac.id

DOI: doi.org/10.20495/seas.6.1_139

This article elucidates the idea of religious pluralism within the Indonesian Theosophical Society (ITS) during the pre-independence period (1900–40). ITS is perhaps the “hidden pearl” in the history of Indonesian spiritual movements in the early twentieth century. It seems that many Indonesians themselves do not know about the existence of ITS in the pre-independence era and its role in spreading a peaceful and inclusive religious understanding. The organization of ITS was legally approved by Theosophical Society headquarters in Adyar, India, at the end of the nineteenth century. For more than 30 years in the early part of the twentieth century ITS discussed the idea of religious pluralism, spreading the value of harmony among believers in the Indonesian Archipelago and managing “multireligious and cultural education” in order to appreciate the diversity and differences of the Nusantara people. This article also shows that the religious understanding of Theosophical Society members in the archipelago is different from the spiritual views of TS figures at headquarters in Adyar. ITS members’ religious views were influenced by factors such as European and American spiritualism, Indian religion and spirituality, Chinese religion, and the intermixture of Javanese mysticism (kejawen) and Javanese Islam (santri).

Keywords:Indonesian Theosophical Society, priyayi, kejawen, comparative religion, perennialism

Preface

This research focuses on how the Indonesian Theosophical Society (ITS) during the pre-independence period (1900–40) spread its ideas on religious pluralism in appreciation of Indonesia’s multireligious and multicultural society. This research is important for the following reasons. First, ITS is possibly the first “society” to have introduced a model of religious studies in Indonesia with an inclusive-pluralist character. This was achieved by emphasizing an esoteric approach and by recognizing and exploring the exoteric and esoteric aspects of religions. As “. . . no statement about a religion is valid unless it can be acknowledged by that religion’s believers” (Smith 1959), ITS tried to learn these aspects directly from scholars or religious leaders of the religions being researched. This model of study was followed by Professor Mukti Ali when establishing the department of Comparative Religion at PTAIN (Perguruan Tinggi Agama Islam, Islamic Higher Education), Yogyakarta, in 1961 (see Bahri 2014).

Second, if one looks at the role of Dirk van Hinloopen Labberton as a figure of the politics of Association and a key figure of ITS or the president of Nederlandsch Indische Theosofische Vereniging (NITV),1) who always called upon Theosophical Society members to “cooperate” with the Dutch colonial authorities, one may assume that ITS was used as a means of “ethical politics” of the Dutch colonial authorities to stifle the resistance of Indonesians (believers). However, one cannot ignore the significant role of ITS at that time in managing “multireligious and cultural education.” ITS members periodically gathered to discuss religious doctrines at lodges (loji). There were lodges in Buitenzorg (Bogor), Batavia, Cirebon, Bandung, Pasuruan, Semarang, Purwokerto, Pekalongan, Wonogiri, Surabaya, and probably in most of the small and big towns on Java. Periodically, they published Theosophical magazines that contained about 85 percent of living religions and beliefs in the archipelago. Apparently, instead of one of the objectives of Theosophy itself, namely, “to form the nucleus of a universal brotherhood of mankind,” Theosophy members also realize that diversity and differences among the Nusantara people lead to conflicts; that is why they lean toward the ideas of pluralism, harmony, and the “common word” of religions.

Third, in dealing with the awakening of nationalism in conventional Indonesian historiography, historians refer to movements such as Boedi Oetomo (BO), Indische Partij, Jong Islamische Bond, Jong Java, Jong Soematra, Jong Ambon, and similar organizations, but religious organizations are rarely ever mentioned as part of the awakening. However, it may be noted that while Islamic organizations such as Muhammadiyah (1912) and NU (Nahdlatul Ulama, 1926) were involved at the lower level, ITS was involved on an elite level in the propagation of nationalism in the era of revolution. Thus, BO and their fellows are to be seen as participants in this process at the middle level.

Research on the Indonesian Theosophical movement includes First, Mengikis Batas Timur & Barat: Gerakan Theosofi & Nasionalisme Indonesia by Iskandar Nugraha (2001). This work was reprinted in 2011 with the title Teosofi, Nasionalisme & Elite Modern Indonesia. It highlights two important aspects: the history, existence, and development of ITS from 1901 to 1933; and the influence of the Theosophical movement on modern Indonesian nationalism. Nugraha shows how many Indonesian students found their identity, experienced a shared destiny, and felt the urge to find their self-awareness as one nation through TS. The most significant contribution of this work is that the TS movement contributed greatly to the awakening of Indonesian nationalism (Nugraha 2011, 76, 88).

The Politics of Divine Wisdom: Theosophy and Labour, National, and Women’s Movements in Indonesia and South Asia 1857–1947 by Herman Arij Oscar de Tollenaere (1996) is another significant work. This is a dissertation by de Tollenaere at the Catholic University of Nijmegen, the Netherlands. In addition to discussing the history of the international Theosophical movement from the United States to Western Europe, Southeast Asia, and Australia; the movement’s members; some of the most important teachings of ITS, such as the doctrines of karma and reincarnation, the nonexistence of change, the existence of higher worlds and evolution, this works focuses on TS’s relationship to three tendencies in the labor movement (in Southeast Asia and Indonesia): social democracy, Communism, and anarchism. In theory, Theosophy was for everyone, but for de Tollenaere, attempts of the Theosophical Society to reach workers and peasants were infrequent and unsuccessful. De Tollenaere’s work broadly explains the political struggles of both the labor movement and women and their connections to the Theosophical movement.

A very short article by de Tollenaere on “Indian Thought in the Dutch Indies” (2000) explains TS influence in the Dutch Indies and how much Theosophy actually represented Indian thought. Another article by de Tollenaere, “The Limits of Liberalism and of Theosophy: Colonial Indonesia and the German Weimar Republic 1918–1933” (1999), explores liberalism and liberal politics as well as their relationships to the Indonesian Theosophical movement.

My research explores the religious views of ITS that are pluralists showed that religious understanding of TS members not merely an effort to strengthen the social harmony among people in the archipelago at the moment but also bring a new perspective that religious understanding is embedded within Theosophical members in the archipelago has significant distinctions—as will be discussed later—with the spirituality views of TS figures at its headquarters in Adyar, India. As far as I can tell, such research has not been done before.

This article refers to TS magazines (resembling journals) published from the first decade of the twentieth century to 1940, which are valuable sources on an important episode of the socio-religious life of Indonesians. These magazines are Pewarta Theosophie Boeat Tanah Hindia Nederland (PTHN, Malay language, 21 volumes, 188 numbers, 1911–38), Theosophie In Nederland Indie: Theosophie Di Tanah Hindia Nederland (Dutch and Malay language, 80 numbers, 1918–25), Theosophie in Nederlandsch Indie (TINI, Dutch language, 1912–30), Kumandang Theosofie (KT, Malay language, 6 volumes, 46 numbers, 1932–37), Persatoean Hidoep (PH, Malay language, 11 volumes, 109 numbers, 1930–40), and Pewarta Theosofie Boeat Indonesia (PTBI, Malay language, 1912–30).

The Emergence of Theosophy in Indonesia

The first signs of a Theosophical movement surfaced in 1875 in New York City. Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (1831–91), a Russian aristocrat who supposedly had mystical or supernatural powers, founded the first Theosophical Society (TS) with the assistance of the Americans Colonel Henry Steel Olcott and William Quan Judge. Immediately after the establishment of the organization, Olcott was elected as its president. In 1879, the TS headquarters were moved from New York to Adyar by Madame Blavatsky. In 1895, TS entered a new era with the appearance of Annie Besant. It was under her leadership that TS became an influential force not just in India but around the world (Cranston 1993, 143–148; Nugraha 2011, 5–7).

According to Nugraha, there is no adequate evidence about the exact beginnings of the TS movement in Indonesia apart from a few notes that provide only general information. One of these notes suggests that the Theosophy movement in “Hindie” (or Indies, i.e., Indonesia) might have been established initially at Pekalongan, Central Java, as a branch of TS Netherlands, eight years after Theosophy was founded in the United States. The lodge in this small town was led by the European aristocrat Baron van Tengnagel. The founding date, however, is not clear as different sources mention two different years: 1881 and 1883. Rather vaguely, Nugraha puts the initial existence of the TS movement at the end of the nineteenth century. At that time, at least, Theosophy had already attracted many Javanese, especially from Central Java.2) However, the who, what, and how of its establishment are still unclear. The only hard fact is that the Pekalongan Theosophical Society was led by an infantry captain of the Dutch East Indies who had been assigned to the topographic division before his engagement with TS. The organization was legally approved by TS headquarters in Adyar, and its license was signed by Colonel Olcott (Nugraha 2011, 8–9).

However, rumor has it that long before Blavatsky founded Theosophy in New York (1875), she had already visited the Netherlands Indies—more than once. According to the Theosophy magazine Lucifer, Blavatsky’s interest in Indonesia was quite high before she formally founded the Theosophy movement, particularly because of the possible contributions of Javanese values to the teachings of Theosophy. Perhaps with this idea in mind, Blavatsky visited the Mendut and Borobudur temples in 1852–60, visited Pekalongan, and spent a night at Pesanggrahan Limpung at the foot of Mount Dieng. In 1862 she returned and traveled around Java, supposedly visiting many places there. Nugraha assumes that the emergence of a Theosophical movement in Pekalongan might have been related to Blavatsky’s visit to Java; perhaps that its earlier activities in the Netherlands Indies were limited to its esoteric aspects only just like in its headquarters (ibid., 8–9, 38). According to Nugraha, details of the earliest TS activity in the late nineteenth century and the role of Baron van Tengnagel are still unclear. The only certainty is that he died in Bogor in 1893 (ibid., 9).

A new phase in the history of TS began in the early twentieth century. In 1901, TS student groups appeared in Semarang. Propaganda to attract people to become TS members was initiated by Asperen van de Velde, a Dutchman and director of a printing and publishing house. Through his job, he spread pamphlets, inviting people to join the Theosophy movement. Starting with seven members in Semarang, TS began to spread to other regions such as Surabaya (1903), Yogyakarta (1904), and Surakarta (1905). Because of his pioneering work, Asperen was later called the spiritual father of the lodge (ibid.).

To sum up, from the early twentieth century to 1940, the ITS movement progressed steadily. Year by year it gained in influence and increased its membership numbers. Because of its fundamental precepts on progress, mystical philosophy, sciences and brotherhood, ITS attracted many young adults and important figures of the day, whose visions later gave an ideological direction to the Indonesian Republic. Some of them were mere sympathizers, while some became members. Familiar names such as Haji Agus Salim, Radjiman Wedjodiningrat, Achmad Subardjo, Cipto Mangunkusumo, Sutomo, Muhammad Yamin, Raden Sukemi (father of Soekarno), and Datuk St. Maharadja show up in the context of TS. Other prominent figures such as Suwardi Suryaningrat or Ki Hadjar Dewantara, Muhammad Hatta, and Soekarno had close connections to the movement. Many local figures of the Javanese and Sundanese aristocracy were also active members and involved in the founding of ITS branches.

During its golden age, 1910–30, Theosophy established many organizations to realize the spirit of brotherhood and to spread the teachings of Theosophy, particularly aiming at the empowerment of indigenous people through education and by developing the quality of Eastern morality. Some of TS’s most important organizations were: (1) Bintang Timoer (1911), specializing in the teaching and practice of Sufism and esotericism or spirituality; (2) Moeslim Bond (1924), a forum for Muslim members to learn to accept the reality of world changes; (3) Mimpitoe or M 7 (1909), an organization for fighting the seven vices, namely, main (gambling), minoem (drinking alcohol), madon (womanizing), madat (drug addiction), maling (stealing), modo (hate speech), mangani (gluttony); (4) Perhimpunan Toeloeng-Menoeloeng (1909), a mutual help organization; (5) Widija-Poestaka (1909), an organization for collecting all kinds of ancient knowledge that could be found in the Netherlands Indies (Nusantara) to protect it from extinction; (5) NIATWUV (Nederlandsch-Indische Wereld Afdeling Theosofische Wereld Universiteit Vereniging), or World Department of Theosophical World University Association of the Netherlands Indies, which organized schools and supported the establishment of educational institutions in the Dutch East Indies. One of the most popular schools to be established was the Sekolah Arjuna (Ardjoena-scholen, Arjuna School, 1914). This TS school was named after Arjuna, the Mahabharata character who was very much liked by natives and well known through shadow puppet performances (wayang). Wayang also happened to be one of the most favored media for disseminating the teachings of theosophy; (6) the Ati Soetji (Pure Heart) Organization (1914), which aimed to improve the lives of women and pursue other social causes.

In terms of membership, Nugraha’s research shows that the Theosophical movement of the Dutch Indies had Dutch, Bumiputera (natives), Chinese, and Indo-European (Indo) members. However, until the first decade of the twentieth century most Indo, as part of European Dutch Indies society, had a poor and marginal socioeconomic position. This is because they were rejected by their own “father,” the Europeans, and their pleas were never heeded. On the other hand, they also had difficulty adjusting to the Bumiputera, or natives, because their official status was European. Under these circumstances the Indo, who were proponents of the Association Movement, dominated the Theosophy membership. In Theosophy, apparently they found the concept that brought them closer to the Bumiputera and enabled them to fight for equality. As Merle Ricklefs states: “Theosophy was one of the few movements which brought elite Javanese, Indo-Europeans and Dutchmen together in this period . . .” (Ricklefs 2008, 198).

Bumiputera constituted the second-largest group of Theosophy members. Amongst the Bumiputera, the Javanese were the most dominant group. The concept of Theosophy and the approach of Theosophy leaders were the two main reasons the Javanese aristocracy were attracted to this movement. Theosophical teachings, which are esoteric, spiritual, or kebatinan, appealed to Javanese aristocrats, who were very fond of mysticism. They regarded the teachings of Theosophy as similar to the secret teachings of ancestral wisdom in their sacred and ancient books. Although embracing Hinduism, Islam, or Christianity, these aristocrats were in fact pantheists who succeeded in consolidating (or harmonizing) their official religion with their ancestors’ mystical wisdom. Therefore, according to Nugraha, the TS movement’s strongest influence was in Central and East Java (Nugraha 2011, 30–31).

Nugraha assumes that the entry of a Bumiputera as a member of TS would undoubtedly be a matter of prestige. The earliest members of the aristocracy who helped to spread the teachings of Theosophy amongst students were figures with great charisma, either because of their position or education or because of their ideas. It was this that attracted most non-aristocratic Javanese students to join TS. In this period it was most unusual for a common native person to be able to mix as an equal with people from high nobility and Europeans, especially Dutchmen, who had much higher status socially and politically. TS also had adequate intellectual facilities such as libraries. Nugraha cites C. L. M. Penders, the writer of The Life and Times of Soekarno (1974): “Soekarno spent many hours in the Library of the Theosophical Society to which he had access because of his father’s membership. It was there that he debated in his mind with some of the great political figures in history” (ibid.). Apart from libraries containing comprehensive collections of scientific texts, TS also offered possibilities for public discussions, either in studie-klasse or in openbare lezing (public lectures) through its NITV organization (ibid., 44). Whereas colonialism divided society along distinct color lines, the TS’s fundamental principle did not consider differences of skin color, race, religion, and ethnicity. This fact increasingly persuaded Bumiputera students to join the organization.

The dominance of Javanese can be seen in the attendance of the first congress of TS in Yogyakarta. Of the 78 delegates meeting at M. R. T. Sosronegoro’s house, there were 19 priyayi (Javanese aristocrats) titled Raden (R), Raden Mas (RM), and Raden Ngabehi (R.Ng). The other 17 delegates consisted of female priyayi. Apart from these Javanese members, there were other ethnic representatives from Sunda, Minangkabau, Melayu, even Manado and Ambon. Based on the ledenlijst (membership list) of 1914 and 1915, apart from the Javanese priyayi, there were many noble persons from West Sumatera (Minangkabau). This is proven by the titles written after their names: Galar Sutan, Galar Datuk, Galar Marah, Galar Tan, Datuk Rangkayo, and many others (ibid., 34–35). Amongst them were Haji Agus Salim, prominent fighters and national heroes, and Dt. Sutan Maharadja, a well-known figure of the nationalist movement (ibid., 32). Many of the Sundanese members also held the title of Raden (ibid., 35).

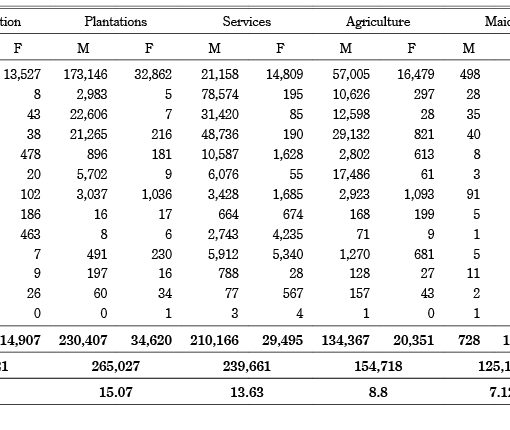

De Tollenaere (2000) notes that in 1930 membership had risen to its highest level ever: 2,090 people, 1,006 of whom were European. These Europeans were mainly Dutch, and they made up nearly 0.5 percent of all the Dutch in the Dutch East Indies, the highest proportion of Theosophists anywhere in the world! A total of 876 members were listed as “Native” (Indonesian), while 208 members were “Foreign Oriental,” as most Asians of non-Indonesian ancestry were categorized. Probably about 190 of them were Chinese and approximately 20 Indian. One should not try to credit the few Indian members of the TS living in the Dutch Indies with any significant influence in the local TS lodges, let alone in the politics of the Dutch Indies. It is clear that this was one of the only places where Europeans would fraternize with “natives” and allow themselves to be in a slight minority position, i.e., not fully in control but only a strong presence. Geographically, membership was concentrated on Java. Socially, most Indonesian members were Javanese aristocrats (priyayi) and only a few of the “natives” were West Sumatran and Balinese noblemen. This membership which is very diverse: European, Chinese, Indian, and Bumiputera themselves has given a clear signal that they have mutually influence one each other, especially in the matter of religion and spirituality as well as this article concerns.

Within this organization the priyayi, constituting the Indonesian elite, felt equal to the Dutch, and the Dutch themselves did not humiliate the priyayi. Due to this noble stratification, the Dutch also gave a lot of opportunities to them, for instance enabling them to study in reputable universities in the Netherlands. Consequently, most of the Indonesian nationalist leaders who came from the elite group and who led Indonesia to independence were educated in the Netherlands.

If we look further into Islamic articles in TS journals, another important group can be found, namely, Muslim santri (traditional Javanese Muslims). Within the system of Javanese stratification, the status of santri is higher than that of common people (wong cilik) but lower than that of priyayi. Regarding the Muslim membership, Haji Agus Salim, a Muslim leader and one of the prominent Indonesian founding fathers, describes why he became a member of ITS (in English):

I had joined the Theosophical Society that was because I saw that their call to religion addressed to a good many Muslims especially who got some what estranged from religion because of their western education, but had still a long standing tradition of religious altogether [sic]. (Nugraha 2011, 32)

ITS and the Idea of Religious Pluralism

First and foremost, the idea of religious pluralism within ITS is centered on the concept of God. When defining Theosophy, Blavatsky interpreted Theos as “god” (not “God” or “personal God,” as people understand it today). Therefore, for Blavatsky, Theosophy is not to be translated as “wisdom of God” but rather as that “divine wisdom” which is possessed by gods (Blavatsky 1981, 2). Instead, what is understood as God by ITS is a personal God, in conformity with religions in the Dutch East Indies (Leadbeater 1915a; Wongsodilogo 1921).

In a lot of articles published, because it focuses on the esoteric, the members of ITS believed that God is one, but believers call him by different names: the Dutch call him “God,” Muslims “Allah Taalah,” Hindus “Ishwara,” Tionghoa or Chinese “Kwan-shai-Yin Thian,” Jews “Jehovah,” Confucians “Tao,” Greeks “Theo,” etc. For ITS, although the names may differ, the Almighty is one and only.3) In other words, there are different languages to address God but the meaning is identical.4) This doctrine is a specialty of perennialism. Since the absolute one is impossible to grasp by man’s very limited logical capacity, He may be grasped through His appearances, symbols, or names, which in turn create plural Gods (Hidayat and Nafis 2003, 69–70).

Based upon the doctrine that the one God has many names, ITS members discussed concepts such as the essential unity of religions, the substantial relationship to God’s messengers, and the continuity and unity of the essence of the holy scriptures. For ITS, these concepts are related to one another. Because they come from the same God, the message of the prophets and the scriptures are one and the same, albeit in different languages. In other words, all prophets were sent by God to bring identical teachings, although their doctrines differed on the surface (S. M. 1926, 140; N. 1927a, 203; 1929, 147–148). Accordingly, all scriptures—the Torah, Bible, Vedas, Upanisads, Bhagavadgita, Quran, Tripitaka, and others—are regarded as holy scriptures containing noble teachings from the prophets; the contexts may be different, but they all originate from the same God (Baehler 1917, 52; Si pitjik 1926, 104). All holy scriptures are regarded as equal. Every believer, no matter what religion he professes, should learn about and do a comparative study of at least two or more of these holy scriptures (Si pitjik 1926, 104). In essence, all religions and creeds derive from the same God and have the same objective (Siswosoeparto 1912, 140). Diverse religions, in ITS terms, are actually “tools to worship God, any of them might be chosen” (Djojodiredjo 1912, 45).

There are also some writings about Islam’s view on the topics above, most referring to the teachings of Sufism. Those authors (perhaps Muslims) strongly believed that the teachings of the pearls of Sufism by Ibn ‘Arabi (1165–1240), Rumi (1207–73), al-Ghazali (1058–1111), and al-Junaid (d. 910) were apt to the doctrine and mission of TS, which wanted world peace through exploring the teaching of unity within religions and prophetic messages. According to those Muslims, the language of Sufis is the language of the heart that enables people to understand the different names and manifestations of God (J. M. 1920, 87; N. 1927a, 203).

One ITS member even argued that all religions were Islam: neither in identity nor in a historical sense, but in quality, by which he meant that all religions promote safety, security, peace, and love. If all believers were to really practice their religion, and then indeed those notions of Islam indicate that since the beginning their religion meant Islam. As he argued: “If those ancient religions were not Islam, obviously their prophets were liars, because Muhammad asked us to believe all the messengers” (W1 1927, 129).

Therefore, to Muslims, all of God’s messengers brought noble and true teachings that were identical with the teachings of Prophet Muhammad. Thus, if Prophet Muhammad asked Muslims not only to believe but also to love and respect the teachings of previous prophets, this implied that the followers of those prophets also should be loved and respected by Muslims. The teaching of Prophet Muhammad and other prophets is that if a Muslim loves and respects God, he or she should love all people and all of God’s creatures too (TVTKL 1927, 15).

These ITS doctrines about one God with many names, the essential unity of religions, prophetic messages, and holy scriptures are all part of TS works and efforts to realize universal brotherhood amongst mankind with no prejudices about race, nation, skin color, and religion. For Theosophists, religions take different forms due to their cultural contexts, because they do not exist in a historical vacuum. For example, the religious Shari’a was developed as a response to the situation and condition of the respective era. Hassan Hanafi, a well-known Egyptian Muslim scholar, argues that revelation is not something that exists outside the solid and unchangeable context, which continuously changes in terms of experiencing (Hanafi n.d., 71). Therefore, the diversity of race, nation, and ethnicity in a certain space and time determines its difference in Shari’a law. Consequently, its rules in detail are neither universal nor applicable eternally in every situation and under every condition. This logical argument is exercised also by pluralists such as John Hick, and followers of perennial philosophy such as Frithjof Schuon, Huston Smith, and Seyyed Hossein Nasr. According to Hick, pluralists believe that there is but one God, who is the maker and lord of all: Adonai and God, Allah and Ekoamkar, Rama and Krishna are actually different names for the same God; and people in the church, synagogue, mosque, gurdwara, and temple worship the same God. Historical situations are what made the believers of various religious traditions call their God by different names as well as develop different rites. For Hick, the great world religions arose within different streams of human life and have in the past flowed down the centuries within different cultural channels. However, believers experience a spiritual encounter with the same God (Hick 1982, 48–56).

Perennialists have a similar explanation. Schuon, for instance, believes that “religions are alike at heart or in essence while differing in form.” According to this view, distinctions between religions refer to distinctions between essence and form. “Form,” of course, is closely related to the physical or the phenomenal world, which is also linked to historical and cultural aspects. Philosophically, for Schuon, the distinction between essence and accident (form) can be modulated into the distinction between exoteric and esoteric (Capps 1995, 304). In other words, outwardly all religions are different, but inwardly they originate from and shall return to a single truth. Likewise, Hossein Nasr, through theo-anthropological discourse, believes that the plurality of prophets and religions is because of changing conditions of the people to whom revelation is addressed. Each prophet reveals an aspect of the truth and the divine law, so it is necessary to have many prophets—in many different regions—to reveal the different aspects of truth (Nasr 1972, 144).

On Demeaning Other Religions, Conversion, and Harmony

Theosophists do not believe in slandering and demeaning other religions through either word or deed. There are four central principles of Theosophy on the existence of differences in religion and attitudes toward the religions of others. First, there are thousands of religions that are suited to their respective nations due to considerations of cultural uniqueness and compatibility. Therefore, there is no religion that is higher or better than another. Each religion contains the same goodness, sublimity, and goal (Djojodiredjo 1912, 45; Karim 1923, 33). In short, according to Kyai Somo Tjitro, a Muslim Theosophist, all religions are equal (Tjitro 1915, 121–122).

Second, it is not appropriate for people to hate and humiliate others only because of differences in beliefs, more so if they have not studied their own religion thoroughly nor the religions they humiliate because they consider the study of other religions to be haram (unlawful). For A. Karim (1923), a Muslim Theosophist, such people are in fact bigoted (“Si picik”).5) Thus, if a believer is a Muslim, Christian, or Hindu, his religious knowledge is not very deep (Tjantoela 1912, 53).6) Theosophists believe that if someone gains a deep knowledge of the essence of their own religion, it will be impossible for them to degrade other religions or discriminate between religions (Rivai 1927, 23).

Third, God’s compassion and justice is for all and not just for one person or one nation. God’s mercy and grace envelop everything, while man’s knowledge will always be disputable (Tjantoela 1912, 55; Karim 1925, 31).

Fourth, as stated by Dirk van Hinloopen Labberton (1912), a key figure of ITS, a good attitude is to study other religions; the best attitude is to study one’s own religion and practice it in the right way; the worst attitude is to persuade, lure someone into, or even force others to follow one’s religion. The unforgivable attitude is to use one’s religion as a means to make someone else look stupid or like a blinded-zealot.

Theosophy does not advocate religious conversion. On many occasions it is firmly stated that religious believers—particularly ITS members—should not convert to another religion. People should be faithful to their religious teachings or Shari’a. According to Muslim Theosophists, a convert is someone who is neglectful:

It is actually not right for the Boemipoetera [natives] who are already Muslim to convert to Christianity or Buddhism, and vice versa. A person who has done so is called someone who is neglectful. Truly, this is just a hindrance in the journey to God, as each religion is just a way to worship God—(as God is one)—as the Quran says: Inna lillahi wa Inna ilaihi raji’un (“Verily, unto God do we belong, and verily, unto Him we shall return”). (Djojosoediro 1918, 41)7)

Theosophy does not claim to be either an old religion or a new one,8) and it does not want to make people “defect” from their own religion or convert to another one. The Theosophical Society wanted religious believers—as members—to truly believe in their own religion by studying the heart and deepest meaning of their prophet’s teachings, and to live together in harmony even though they had different beliefs and religions (Leadbeater 1915b, 20; Guldenaar 1916, 14). ITS claimed that, in fact, rather than preaching conversion, Theosophy’s teachings would actually strengthen one’s faith to one’s own religion. Its members would still be faithful to their own religion (Shari’a), but with a much deeper mystic-philosophical understanding beyond exoteric understanding. Theosophy would open the hearts of believers to learn more about each religion than they ever knew before, even—in some cases—helping people to become obedient worshippers of their own religions. There was a case involving a member who wanted to convert, but after a Theosophy master explained the truth and reality of his religion, he changed his mind (Labberton 1912, 126; Leadbeater 1915b, 20).

Theosophy believes that religious differences merely mean different ways to reach God. On this matter, ITS members referred to the Bhagavadgita: “Man has come to Me through many paths, and through whatever path a man came to me, I accept him on this path because all the paths are Mine” (Latief 1926a, 30); and to the Quran: “For the followers of every religion: We have set certain rules to follow as good as we can, do not let them argue with you, but invite them to the Lord because you really are on the straight path” (P. A. 1926, 12–13). Therefore, Theosophists believe that differences between paths are not a matter of principle but are, in fact, the ultimate goal. Both Broto (1926), a Muslim Theosophist from Bogor, and Baehler (1916) firmly argue that all paths surely lead to the same God. With this kind of understanding, differences are not supposed to be a seed of conflict and dispute.

According to A. Latief (1926a), a Muslim member of TS, a deep understanding of Islam is in fact in line with the doctrine of Theosophy. So, if someone is willing to do research on the theme of brotherhood in the holy scriptures, they will find verses on the essential unity of religions and the brotherhood of mankind. One will find these two themes only if one is able to penetrate into the deeper aspects of the teachings of the holy scriptures. Conversely, one can expose the differences and contradictions between religions, which will only trigger conflict. As the main goal of TS is universal brotherhood and harmony, its members and all religious believers are encouraged to discover both themes when studying religions.

In order to achieve understanding and respect between religions, Labberton argued, there were only two ways for the people of the Netherlands Indies to progress: first, to study science together with the Dutch until equality with Europeans was achieved; and second, waging war with other nations (presumably the Dutch). The first way would lead to a peaceful and secure life, whereas the second would lead to war and disarray. It was up to the people of the Netherlands Indies to choose between conflict and brotherhood, war and peace, living or dying. According to Labberton, the people of Europe, China (Tionghoa), and Java who chose the second way had become partners or troops of Sang Ijajil (the Dajjal, or Antichrist); whereas if they had chosen the first way, they would have become troops of Sri Tunjung Seto—Sang Guru Dewa (The Divine Master), or King of Harmony.9)

Raden Djojosoediro, an Indonesian Muslim Theosophist, reminded Muslims not to be “jealous” when a Muslim converted. Conversion to another religion often creates conflict in the Muslim community, internally or externally. As Djojosoediro wrote, conflict—whether caused by conversion or something else—usually comes from a group of “uneducated people.” Students of Theosophy, however, were urged to live together in peace and harmony (guyub and rukun), despite all their differences. Djojosoediro advised Muslims to follow the way of Prophet Muhammad, i.e., avoiding jealousy and conflict, and showing compassion (welas asih). Djojosoediro described India as a country with religious harmony where—during that time—people of a diversity of ethnicities and religions were able to live together in harmony, respecting and appreciating each other. Believers of different religions were also free to practice their beliefs. India had proven that differences in religions and beliefs did not necessarily produce conflict and quarrels (Djojosoediro 1918, 42).

Freedom of religion is a parallel concept to Theosophy’s idea about the equality of religions. In fact, Theosophical doctrines of unity and similarities among religions strongly support the rule and practice of religious freedom. The TS deeply agreed with the Dutch government rule on Article X concerning religion that stated:

It is prohibited to apply force on other people in their way of thinking or their religion. All man is free to worship his God. All of the religious holidays are recognized. Humiliating and diminishing the rights of any religion is prohibited . . . and do not make others miserable and their lives difficult. All religious teachers and Islamic scholars (Ulama) do not get salary from the government. (Redaksi 1921, 96)

TS published this law in 1921, claiming that the Dutch government was founded on brotherhood and harmony, which resonated with the core of TS doctrine.

Perennialism, Religious Humanism, and Javanese Mysticism

In appreciating pluralism, multiculturalism, and harmony, ITS has some important implications. First, it interprets religions with a perennialist approach. This approach is adherent to their research. Even TS itself is a form of perennialism. Perennialism is a well-known philosophical system. According to Charles Schmitt, it is believed that the concept of perennial philosophy originated with Leibniz, who used the term in a frequently quoted letter to Remond dated August 26, 1714. But careful research reveals that the term “philosophia perennis” was used much earlier than Leibniz; indeed, it was the title of a treatise published in 1540 by the Italian Augustinian Agostino Steuco (1497–1548). According to Schmitt, although Steuco was perhaps the first to employ this phrase—he was certainly the first to give it a fixed, systematic meaning—he drew upon an already well-developed philosophical tradition, viz., the ancient tradition since thousand years ago. Drawing upon this tradition he formulated his own synthesis of philosophy, religion, and history, which he labeled philosophia perennis (Schmitt 1966, 506).

According to Schmitt, at the very beginning of Steuco’s work he writes that there is “one principle of all things, of which there has always been one and the same knowledge among all peoples.” For Steuco, De perenni philosophia is an ancient tradition of wisdom that can endure eternally (perennis). The enduring quality of this philosophy rests in the supposition that there is a single sapientia knowable by all (ibid., 517). According to Schmitt, from Steuco’s statement a question comes immediately to mind: What was Steuco’s view of history? How did he interpret the process and development of man’s thought so that he could argue there was a constant irreducible core of people agreement of all time? Steuco acknowledges that history brings with it changes, but these are minor when compared to the elements that remain constant. For Schmitt, when Steuco speaks of “progress” it usually means merely “moving forward” or “advance of time.” History flows like time, says Steuco; it does not know “dark ages” and “revivals.” Steuco was convinced that “there is but a single truth that pervades all historical periods.” The truth is perhaps not equally well known in all periods, but it is accessible to those who search for it (ibid., 518).

According to Steuco, the truth and wisdom within De perenni philosophia have always been maintained and preserved via prisca theologia and philosophia. For Schmitt, the word priscus, which often recurs in Steuco, probably best translates as “venerable.” So that the truth and wisdom were always preserved through “the venerable philosophers and theologians.” In the perennial philosophical system, truth flows from a single fountain, as it were, but is manifested in various forms. From this philosophical system comes the doctrine of the One and the many. Moreover, the revelation of truth dates back to the most ancient times (Latin: prisca saecula), and we can find the truth in the writings deriving from this period. The wisdom of earliest times is then transmitted to the later centuries (ibid., 520).

Perennial philosophy teaches that the ultimate reality, the divine (the ontological), is nameless and unattainable, where none of the expressions can be appointed (Thomas 1996, 73). However, this philosophy subscribes to the epistemology that God can also be reached by the mind of man. In other words, the ultimate reality is the godhead, the essence, Tao, Brahman, the energy, the consciousness, or something with a similar name. He has nature qualities as well as rid of them. Regarding to his nature qualities, he is the personal one, material and actually existed in space and time, but he may also called as an impersonal, non-material, and beyond the time and space. “He is within us, around us, and even within ourselves; but he is also at once completely outside of us, and essentially totally not us. Much can be said about him, but none of them can declare his words” (Laibelman 1996, 86). In the context of religious studies (or the comparative study of religions), perennialism considered to have an in-depth explanation of the two sides of religion, namely: (1) esoteric aspects that are eternal and immutable in all religions, and the discovery of the intersection and the unity of religions, (2) exoteric aspects that reveal all the different forms of religion. Perennialism then is used to explain the intersections and differences between religions.

If we look carefully, perennialism and Theosophy discuss a similar philosophical matter: ancient wisdom traditions. Blavatsky and other key figures after her frequently asserted that Theosophy was based on ancient knowledge or wisdom, taken from the early Greek philosophers, followed by subsequent philosophers, generation after generation in different countries, lush with eternal wisdom. The Theosophist glorifies the ultimate reality, the true and eternal, from which diverse manifestations emerge. From the one truth various forms emerged, including diverse religions. Therefore, from the outset, Blavatsky taught that the great religions, schools, and sects were small twigs or shoots growing on the larger branches, that those shoots and branches came from the same tree, the wisdom of religion. This is one of the principal teachings of Theosophy, which is drawn from eternal wisdom (sophia perennis). However, while perennialism discusses limited key themes such as the discourse on a personal and impersonal God and His relationship with creatures, Theosophy in the hands of Blavatsky—and her fellows—later developed into a complex and profound discourse with strong nuances of mysticism and occultism (see Blavatsky’s works such as The Key to Theosophy, The Voice of the Silence, Nighmare Tales, Studies in Occultism, Isis Unveiled, The Secret Doctrine, and others).

Another important thing that should be noted is the influence of Indian Hindu spirituality with regard to perennialism’s ideas on ITS members’ religious views. Indian spirituality was rich in religious pluralism, i.e., the appreciation and recognition of the sanctity and salvation of non-Hindu religions. The ITS was generally sympathetic to ideas of Hinduism. De Tollenaere concludes that

the Theosophical Society, which was quite influential in the Dutch Indies, especially among the Dutch colonial administrators as well as the Javanese nobility (priyayi), did disseminate Indian thought to the archipelago, albeit in a highly idiosyncretic [sic], corrupted and “Westernized” form. (de Tollenaere 2000, 3)

Appearing to be Indian, its roots were actually from the West, viz., European-American spiritualism, established by Blavatsky and the early Western Theosophy figures.

However, de Tollenaere forgets to mention the important fact that the archipelago had a long history and relationship with Hinduism, specifically Indian Hinduism. The influence of Hindu religion and spirituality was very strong within the Javanese community, and Javanese Islam still has many elements of Hindu culture. On the one hand, de Tollenaere was correct that Hinduism as discussed by Indian and Indonesian Theosophy members was of a sort that had already been Westernized. However, magazines published by the ITS show that the Hindu authors or sympathizers, when discussing Hinduism, were in fact often talking about Hinduism as understood and practiced in the archipelago. It was the model of pre-Islamic Hinduism that continued to exist long before Theosophy even appeared in the archipelago. Archipelagic Hinduism, particularly in Java, was a hybrid Hinduism, i.e., the acculturation between Indian Hinduism and the indigenous religion of the archipelago.

Likewise, I argue that the ITS in this respect greatly differed from what was espoused by Blavatsky and other Western figures such as Annie Besant. Blavatsky and Besant did not adhere to a religion (Christianity in this case); Theosophy became for them a way of life or “a new life guidelines” that was believed to bring them to the Truth. In fact, TS leaders referred to Theosophy as the Ultimate Truth, and there is no religion higher than the Truth (Sanskrit: Satyan Nasti Paro Dharmah). For Blavatsky, Theosophy is the essence or “the mother” of all religions and of absolute truth (Blavatsky 1981, 32). On the contrary, extensive data show that Indonesian Theosophy is firmly rooted in religions that had long been established in the archipelago. ITS does not adhere to a concept of an impersonal God a la Blavatsky, and it does not make Theosophy into a “new religion” or a “syncretic religion” that must be separated from the formal religions of its members. In other words, ITS members did not leave their formal religion or set up a new religious institution that was considered to be higher than formal religions. Theosophy was used as a tool to understand the deepest dimensions of the formal religions professed by members of Theosophy. They then tried to show the essential unity of religions, which could support the goals of Theosophy in realizing universal brotherhood amongst human beings.

Second, and closely related to the first, the religious views of ITS are colored by religious humanism. Does this humanism in ITS’s spirit and mindset affect its religious complexion or do the teachings of Theosophy and perennialism enrich their humanism spirit? It seems that the two are inextricably linked. The criticism that Theosophists base their humanism on secular humanism and do not strive to build a brotherhood of man based on religion is unfounded, but nevertheless Adian Husaini (2010), a writer and Indonesian Muslim activist, accuses Theosophy as follows (in translation):

The mission of TS that carries interfaith brotherhood is identical with the mission of the Free Masonry movement. Not surprisingly, in addition to leading the TS, Annie Besant had led Freemasonry. . . . By positioning itself outside of the existing religions, Freemasonry emphasizes interfaith humanitarian problems. Religion is not used as the basis for building brotherhood among mankind. Secular humanism became the ideological model. (Husaini 2010, xiii, xvi)

However, such allegations are futile; and as my study shows, ITS’s humanism is firmly rooted in religion, especially the major religions in the Dutch Indies (Nusantara), namely, Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam, Christianity, and Confucianism. As for Islam, I have already discussed above the theological ideas about relationships and intersections between religions—which will lead to an understanding of the brotherhood of mankind—often referring to the concept of Islamic Sufism, and therefore not based on secular Western humanism. ITS members firmly adhered to the major world religions in Indonesia, primarily emphasizing a Sufi (mystical) dimension, have been rooted deeply in the personalities of ITS members.

Within the context of Western secular and liberal humanism—in the sense of being cynical to religion, Theosophy, and especially ITS, is an exception. Despite embracing humanism, through dreaming about realizing universal human brotherhood and spreading love amongst mankind, ITS members remained rooted in their religion, particularly the formal religion that they professed. For Theosophy, humanism is the key to keeping both culture and religion civilized. Religion without a humanistic perspective or alignment to human values can easily become harsh, ruthless, and cruel, as many cases of terrorism and other forms of violence in the name of religion show. If TS considered adopting humanism, it was a religious humanism, rooted in humanist religious values.

Third, the religious views of ITS are closely linked to Javanese culture and religion (Javanism, kejawen). Kejawen is the Theological insight of Javanese as a result of the accumulation of various ancient traditions (Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam, and the traditions of the ancestors). The accumulation is very smooth and thick, thus forming a well-established worldview. The strength of this worldview is the capacity to maintain harmony and peace amongst different beliefs, concepts, and religions (Endraswara 2012, 42).

Theosophy in Indonesia developed mostly on Java. Most of the Theosophical lodges were also located on Java. The time from the emergence and development of Theosophy (early twentieth century) until the independence of Indonesia was a period that was very fertile for the views, attitudes, and practices of kejawen. From around the tenth century to the fifteenth, Hinduism and Buddhism were the religions followed by the majority of Javanese. Together with animism they formed the original religions of Java. Soewarno Imam, professor of Javanese mysticism at State Islamic University Jakarta, has argued that Hinduism and Buddhism in Java, especially after their spread to East Java, continued to show rapprochement and compromise between the two. If in their country of origin, i.e., India, Hinduism and Buddhism were often involved in hostility and conflict, this did not occur in Java. A strong compromise between the two religions occurred during the time of Kertanegara (King of Singosari). Harmonious life amongst various schools of “new religion,” especially the flow of Shiva, Vishnu, and Buddha, continued until the Majapahit era, culminating with the reign of King Hayam Wuruk (Imam 2005, 20).

When Islam entered the archipelago at the end of the thirteenth century, especially on the north coast of Java, it came in a mystical form, aligned with the ethical values of the Hindu-Buddhist religion. The ethical values of mystical Islam could slowly be accepted by Hindu-Buddhist Javanese (ibid., 45–47). However, the reception was not fully achieved, but still holding together most of the ethical-spiritual values of these two old religions. Thus, the term “Javanese Islam” denotes Islam as understood and practiced in conjunction with the pre-Islamic spiritual heritage. Mark Woodward, for example, an expert on Javanese Islam, has an interesting theory about it. According to Woodward, the effect of the interpretation of doctrine, practice, and the myth of Hindu-Javanese toward Javanese Islam still seems significant. One of the great debates amongst Javanese santri10) and abangan11) is about shirk (polytheism). The debate shows the diversity of views on the issue of shirk and difficulties in determining the exact difference between traditional santri and the interpretation of Javanism (Woodward 1989, 215–217).

Another thing that stands out in Javanese Islam is the glorification of the saints (Wali). Great respect for the Wali, whether the legendary Nine Saints (Wali Songo)12) in Java or their predecessors from Arabian lands, such as al-Hallaj, al-Ghazali, and Ibn ‘Arabi, is shown not only by the santri but also by traditional Javanese Muslims despite slightly different interpretations. The abangan, in particular, has great respect for Sheikh Siti Jenar13) and Ahmad Mutamakkin,14) who had an intellectual relationship with al-Hallaj.15) In fact, if explored in depth, figures such as Jenar, Mutamakkin, and Hallaj, besides being considered mystical characters, are also known as scholars who upheld the shari’a, especially in their early sainthood. Javanese Islam, either in the form of the “white” santri or “red” Muslim (abangan or Javanese Muslim), has a uniqueness and complexity that is hard to view in categories of merely black and white. Even the white traditional santri has the attitudes of syncretic Javanese culture and mysticism embedded in his views.

According to Woodward, Javanese Islam can indeed be called syncretic, but what stands out is that the elements of Islam, especially Sufism, dominate. However, Javanese Islamic syncretism was not typical Javanese. The Javanese were not alone in trying to unite the traditions of the past with Islamic monotheism. Islamic figures such as al-Ghazali, Ibn ‘Arabi, and Sultan Akbar also attempted to integrate philosophical views from outside into Islam (Woodward 1989, 234–235). Regarding syncretism among the Javanese people, the anthropologist Muhaimin (2001) argues that qualities such as tolerance, accommodation, and flexibility are indeed special to the Javanese. Rather than rejecting a new religion that came in, the Javanese accepted it as an important element in shaping a new synthesis. According to Bekki, as quoted by Muhaimin, the Javanese syncretism of religious life may result from the flexible Javanese attitude toward other religions. Although animistic beliefs were entrenched for a long time, the Javanese successively accepted Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam, and Christianity but then “Javanized” everything (Muhaimin 2001, 1).

According to Soewarno Imam, there are two major groups in the socio-economic structure of the Javanese community: common people (wong cilik), most of whom are farmers by profession; and the priyayi, who work mostly as civil servants or intellectuals. In terms of religious affiliation, the Javanese community is also divided into two groups: abangan and the santri. Previously, most of the wong cilik and the priyayi were abangan who practiced kejawen. The santri, who try to live according to Islamic law (Shari’a), mostly work as traders and entrepreneurs and are therefore considered to be quite wealthy. Thus, from the point of view of the Javanese community, the santri were perceived as higher than wong cilik but lower than the priyayi (Imam 2005, 54). Hence, in this socio-economic structure, we can add a third class: the santri, who are between the wong cilik and priyayi.

The Javanese traditional aristocracy (priyayi) consisted almost entirely of believers of kejawen, although officially many of them claimed to be Muslims. Most of them followed the community-association (including Theosophy) in their efforts to attain a perfect life through meditation and mystical ways. The priyayi constituted the Javanese elite, who were instrumental in carrying forward the influence of traditional pre-Islamic Javanese spiritual culture in the form of dance, gamelan, and shadow puppetry (wayang) (ibid., 55–56). Wayang is a hobby among priyayi and was widely used by Theosophy as a medium for disseminating teachings to its members and the Javanese community in general.

We may discern a close connection between the matters discussed above (kejawen, Javanese Islam, and the struggle between the santri, abangan, and priyayi) and the religious views of Theosophy or the views of Theosophy members, consisting of the santri and the priyayi. Why were the Indonesian Theosophists fond of idealizing issues about the intersection of religions or the essential unity of religions, often referring to mystical figures? That was because kejawen and Javanese Islam are both saturated with mysticism, in their Islamic Sufism as well as Hindu-Buddhist varieties. This mysticism contains many teachings about the intersection between esoteric religions, which is reinforced by Javanese syncretistic culture. Thus, Javanese Theosophy has been influenced by these two forms of cultural wealth from the beginning. Why are Theosophical teachings about universal brotherhood, harmony, and peace welcomed with open arms by Javanese Theosophists? The reason is to do with Javanese lofty ideals of a culture of peace (Endraswara 2012, 38), characterized by tolerance, accommodation, and flexibility.

Inspiring “Multicultural Education”

When dealing with religious views of ITS that are inclusive-pluralist, it is important to look at the features of Theosophy magazines published for half a century. Among PTHN, PTBI, KT, and PH, for instance, almost 85 percent contained religious teachings (including ethics), especially of Indonesian living religions; about 10 percent contained scientific explanations; and 5 percent was news on the socio-political life of the time. The most interesting feature of the magazines was their diversity of religious themes. Every single issue contained articles on three to five religions, with a variety of topics. There was never a magazine that discussed only one or two religious topics. So, from the outset, Theosophical magazines have presented an educational model that appreciates differences of religion and culture, which is currently known as “multicultural education.”

When opening a Theosophy magazine, one immediately reads a comparative study of religions. Usually the top middle of the page contains the title (subject) of the article, and then explained through the perspective of religions and their connections with Theosophy. The title of the article is sometimes only one or two words, such as “Buddhism,” “On Islam,” “Hindu,” “Baha’i,” “Christian,” or “Confucianism.” After an article on one religion, the next one (on the next page) is about other religions. Similarly, when there is an article on a theme, the next one is on another theme. When an article is “to be continued,” the next part is not on the next page but interrupted by two to four posts. Indeed, we as readers are not bored by reading about only one religion, belief, or theme. The diversity of features in printing is deeply felt by the readers.

This is different from religious magazines that were published in the New Order era until the 1980s. Some magazines are published lettering “only for personal entertainment,” or “only to a limited circle,” and it usually about an exclusive religious understanding that humiliates other people’s beliefs.

Conclusion

ITS has always advocated that deep religious understanding is closely connected to inclusive-pluralist religious views and attitudes, which is an inspiring reminder of the past harmony between religious communities in the Indonesian Archipelago. ITS’s deep religious understanding and broad horizon resulted from intense struggles and encounters with ideas from various nations—Europe, America, India, China—but also, and perhaps most important, the cultural richness of the Indonesian nation itself, especially Javanese culture, which is always inclined to harmony. Today, Indonesia is characterized by the rise of religious fundamentalism, which tends to be intolerant and exclusive, and it seems that Indonesia is increasingly losing the depth of its own religiousness and its true identity as a country that has been known for centuries for its culture of harmony, tolerance, and peace. It is in this context that ITS’s religious views are still relevant, offering much material for reflection.

The limitations of this research can be an agenda for further research. First, it would be alluring to examine the role of Muslim Theosophists within ITS since there are many writings on Islam in ITS magazines. In addition to the idea of a personal God, the magazines contain many Malay Islamic terms, such as “Allah,” “tawhid,” “syariat,” “hakikat,” “sufi,” etc. Among ITS publications, there are several papers discussing the teachings of Islam, including the following: PTHN (1911), PTHN (1912), PTHN (1915), PTHN (1916), PTHN (1917), PTHN (1918), PTHN (1919), PTHN (1920), PTHN (1921), PTHN (1922), PTHN (1923), PTHN (1925), PTHN (1926), PTHN (1927), PTBI (1928), PTHN (1929), and KT (1929, 1931, and 1932), and perhaps many others. Apparently, the discourse on Islam within ITS quite coloring the existence of Theosophical movement that does not happen anywhere, neither at its headquarters in Adyar nor in Southeast Asia. Second, it would be interesting to study the commonalities between the Theosophical organization and Freemasonry. Indonesians in particular and the people of Southeast Asia in general, do not have an accurate knowledge about the distinction between Theosophy and Freemasonry. What and how was their relationship in Southeast Asia? In Indonesia alone, there are two representative works on Freemasons: Tarekat Mason Bebas dan Masyarakat di Hindia Belanda dan Indonesia 1764–1962 by Th. Stevens (1994; printed in Indonesian in 2004) and Freemasonry Di Indonesia, Jaringan Zionis Tertua yang Mengendalikan Dunia by Paul van der Veur (1976; printed in Indonesian in 2012). The quandaries arise due to the facts that most members of Indonesian Theosophy and Freemasonry are priyayi. Similarly, both Theosophy and Freemasonry have the same goal: “to form the nucleus of a universal brotherhood of mankind without distinction of race, colour, or creed” (Blavatsky 1981, 22). Academic research on both will probably contribute to academic communities in Southeast Asia.

Accepted: July 19, 2016

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Professor Edwin Wieringa, who was my academic host during my Alexander von Humboldt Fellowship at the University of Cologne, Germany, from March 2012 to December 2013. I am grateful to him also for his valuable comments on this article.

References

Anonymous. 1926. Theosofie [The Theosophy]. Pewarta Theosophie Boeat Tanah Hindia Nederland (PTHN).

―. 1920. Goenanja roepa-roepa pengadjaran didalam kitab-kitab Tasaoef [The benefits of some teachings on Sufism]. PTHN: 108.

―. 1915. Woedjoed-woedjoed moelia [The sacred beings]. PTHN: 135–136.

Artawijaya. 2010. Gerakan Theosofi di Indonesia: Menelusuri jejak aliran kebatinan Yahudi sejak masa Hindia Belanda hingga era Reformasi [The Theosophical movement in Indonesia: On tracing the footsteps of Jewish mysticism, from the Dutch colonial era to the Reform era]. Jakarta: Pustaka Al-Kautsar.

Baehler, Louis A. 1917. Gadadhara atau Ramakrisjna [Gadadhara or Ramakrisna]. PTHN (4): 52.

―. 1916. Gadadhara atau Ramakrisjna [Gadadhara or Ramakrisna]. PTHN (7): 98.

Bahri, Media Zainul. 2014. Teaching Religions in Indonesian Islamic Higher Education: From Comparative Religion to Religious Studies. Indonesian Journal of Islam and Muslim Societies 4 (2): 159–160.

Bizawie, Zainul Milal. 2002. The Thoughts and Religious Understanding of Shaikh Ahmad al-Mutamakkin: The Struggle of Javanese Islam 1645–1740. Studia Islamika, Indonesian Journal for Islamic Studies 9(1): 41, 55.

Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna. 1981. The Key to Theosophy. Pasadena: Theosophical University Press.

Broto. 1926. Tentang agama Islam dalam Theosofie [On Islamic religion in Theosophy]. PTHN (9): 125.

Capps, Walter H. 1995. Religious Studies: The Making of a Discipline. Minneapolis: Fortress Press.

Cranston, Sylvia. 1993. H.P.B.: The Extraordinary Life and Influence of Helena Blavatsky, Founder of the Modern Theosophical Movement. Santa Barbara: Path Publishing House.

Derun. 1954. Meditasi untuk permulaan (II) [Meditation for beginners]. Pewarta Theosofi Tjabang Indonesia (PTTI) (27): 18–19.

De Tollenaere, Herman Arij Oscar. 2000. Indian Thought in the Dutch Indies: The Theosophical Society. IIAS Newsletter Online (23): 2–3.

―. 1996. The Politics of Divine Wisdom: Theosophy and Labour, National, and Women’s Movements in Indonesia and South Asia 1875–1947. Leiden: Uitgeverij Katholieke Universiteit Nijmegen.

Djojodiredjo, Rd. 1918. Tak ada judul [There is no title]. PTHN (1): 42.

―. 1912. Wadjibnja orang hidoep [An Obligation for living men]. PTHN: 45.

Djojosoediro, R. 1918. Tak ada judul [There is no title]. PTHN (1): 41, 42 .

Endraswara, Suwardi. 2012. Falsafah hidup Jawa: Menggali mutiara kebijakan dari intisari filsafat Kejawen [The Philosophy of Javanese: Exploring the wisdom in the philosophy of Javanese mysticism]. Yogyakarta: Cakrawala.

Guldenaar, W. N. 1916. Perhimpoenan Tasaoef [Association of Sufism]. PTHN (3): 14.

Hanafi, Hassan. n.d. Dirasat Islamiyyat [Islamic studies]. Egypt: Maktabah al-Anjalu al-Mishriyyah.

Hick, John. 1982. God Has Many Names. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press.

Hidayat, Komaruddin; and Nafis, Muhammad Wahyuni. 2003. Agama masa depan: Perspektif filsafat perennial [The future religion: A perennial perspective]. Jakarta: Gramedia.

Hien, Kwik King. 1928. Pembatjaan [The reading]. Pewarta Theosofie boeat Indonesia (PTBI): 124.

Husaini, Adian. 2010. Islam, Theosofi, dan Freemasonry [Islam, Theosophy, and Freemasonry]. In Gerakan Theosofi di Indonesia: Menelusuri jejak aliran kebatinan Yahudi sejak masa Hindia Belanda hingga era Reformasi [The Theosophical movement in Indonesia: On tracing the footsteps of Jewish mysticism, from the Dutch colonial era to the Reform era] by Artawijaya, p. xi–xxvii. Jakarta: Pustaka Al-Kautsar.

Imam, Soewarno. 2005. Konsep tuhan, manusia, mistik dalam berbagai kebatinan Jawa [The concepts of God, men, and mystic in various streams of Javanese mysticism]. Jakarta: Rajagrafindo Persada.

J. M. 1922. Satoe pokok [One pillar]. PTHN (1–2): 21.

―. 1920. Hal rasoelallah [On the prophet]. PTHN: 87.

Karim, A. 1925. Serba-serbi tentang Allah [Perspectives on Allah]. PTHN (2): 31.

―. 1923. Auwaloeddin Ma’rifatoellah [The first thing in religion is knowing God]. PTHN (3): 33.

Khan, Inayat. 1922. Soefie [The Sufis]. PTHN (5): 66.

Labberton, Van Hinloopen. 1917. Kenjataannja tetenger dan perlambang [On reality and symbols]. PTHN (11): 161.

―. 1912. Perdamian doenia [sic] [World peace]. PTHN: 126–127.

―. n.d. Perdamian sadoenia [World peace]. Theosophie in Nederlandsch Indie (TINI): 126.

Laibelman, Alan. 1996. Realitas dan makna ultim menurut filsafat perenial [The reality and the ultimate in perennial philosophy]. In Perenialisme, edited by Ahmad Norma Permata, p. 86. Yogyakarta: Tiara Wacana.

Latief, A. 1926a. Faedah Theosofie boeat manoesia [The benefit of Theosophy for men]. PTHN (1): 10–11, 30.

―. 1926b. Faedah Theosofie boeat manoesia [The benefit of Theosophy for men]. PTHN (2): 31.

―. 1925. Faedah Theosofie boeat manoesia [The benefit of Theosophy for men]. PTHN (12): 189–190.

―. 1922. Ada [Exist]. PTHN (5): 67–68.

Leadbeater, C. W. 1915a. Kitab Theosofie [The book of Theosophy]. PTHN: 15.

―. 1915b. Theosofie itoe apa? [What is Theosophy?]. PTHN (2): 20.

Mangoenpoerwoto. 1920. Sikap Theosophie kepada kemadjuan oemoem [Theosophy’s attitude toward public progress]. PTHN (1): 8–10.

Massignon, Louis. 1975. La passion de Husayn Ibn Mansur Hallaj: Martyr mystique de l’Islam execute a Bagdad le 26 Mars 922 [The passion of al-Hallaj: mystic and martyr of Islam], Vol. 3. Paris: Gallimard.

Muhaimin. 2001. Islam dalam bingkai budaya lokal: Potret dari Cirebon [Islam in local culture: A Portrait from Cirebon]. Ciputat: Logos.

Mulkhan, Abdul Munir. 2003. Syekh Siti Jenar: Pergumulan Islam-Jawa [Syekh Siti Jenar: A Struggle of Islam-Java]. Yogyakarta: Bentang Budaya.

N. 1930. Djalannja mentjarik ingsoen [The path of looking for myself]. PTBI (3): 34.

―. 1929. Sekarang datang swara baroe, Apa soedah tahoe? [New voice has come, Don’t you know?]. PTBI (10): 147–148.

―. 1927a. Djagad goeroe [The world of a master]. PTHN (8): 201–203.

―. 1927b. Seng-To! Kow-Li! PTHN: 124.

Nasr, Seyyed Hossein. 1972. Sufi Essays. London: George Allen & Unwin.

Nugraha, Iskandar. 2011. Teosofi, nasionalisme & elite modern Indonesia [Theosophy, nationalism, and the Indonesian modern elite]. Depok: Komunitas Bambu.

―. 2001. Mengikis batas Timur & Barat: Gerakan Theosofi & nasionalisme Indonesia [Beyond the limits of East and West: Theosophical movement and nationalism of Indonesia]. Depok: Komunitas Bambu.

P. A. 1926. Takdir [Fate]. PTHN (1): 12–13.

Redaksi. 1921. Pemerintahan jang berdasar persoedaraan atau perdamaian [A government based on brotherhood and peace]. PTHN (6): 96.

Ricklefs, Merle Calvin. 2008. A History of Modern Indonesia since c. 1200. 4th ed. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

―. 2006. The Birth of the Abangan. Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land-en Volkenkunde, Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia and Ocenia 162(1): 35–36.

Rivai, A. 1927. Kedatangan goeroe (Mahdi) [The arrival of the master]. PTHN (2): 23.

Rumi, Jalal al-Din. 1990. The Matsnawi of Jalal al-Din Rumi, translated and edited by Reynold Nicholson. Book 3. Cambridge: E. J. W. Gibb Memorial Trust.

Schimmel, Annemarie. 1975. Mystical Dimensions of Islam. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Schmitt, Charles B. 1966. Perennial Philosophy: From Agostino Steuco to Leibniz. Journal of the History of Ideas 27(4): 506–520.

Si pitjik, S. 1926. Membandingkan agama [On comparing religions]. PTHN (7): 104.

Siswosoeparto. 1916. Jang bekerdja boeat loge dan Theosofische vereeniging [Someone who devoted himself to the lodge and Theosophical works]. PTHN (4): 120.

―. 1912. Kabar dari M 7 [News from M 7]. PTHN: 140.

S. M. 1926. Djalan kesempoernaan [A path of perfection]. PTHN (10): 140.

Smith, Wilfred Cantwell. 1959. Comparative Religion: Whither and Why? In The History of Religions: Essays in Methodology, edited by Mircea Eliade and Joseph Kitagawa, p. 42. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Soebardi. 1975. The Book of Cebolek. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

Thomas, Owen. 1996. Kristen dan filsafat perenial [The Christian and perennial philosophy]. In Perenialisme, edited by Ahmad Norma Permata, p. 73. Yogyakarta: Tiara Wacana.

Tjantoela. 1912. Peringetan bab empat warna orang manoesia [A warning in chapter four on the color of human beings]. PTHN: 53, 55.

Tjitro, Kijahi Somo. 1915. Djalan menoentoet elmoe kenjataan [A path that demands a knowledge of reality]. PTHN (10): 121–122.

TVTKL, Lid. 1927. Katerangan dari goeroe kita [An explanation from our master]. PTHN (1): 15.

Van Motman, H. E. 1912. Kepada toean redacteur soerat kabar Pewarta Theosophie [Dear Editor of Pewarta Theosophy Newspaper]. PTHN: 123–124.

Wieringa, Edwin. 1998. The Mystical Figure of Haji Ahmad Mutamakin from the Village of Cabolek (Java). Studia Islamika, Indonesian Journal for Islamic Studies 5(1): 30.

W1. 1927. Haroes terpoedji [Praiseworthy]. PTHN (6): 129.

Wongsodilogo, R. M. 1921. Djalan oetama [A leading path]. PTHN: 51–52.

Woodward, Mark R. 1989. Islam in Java: Normative Piety and Mysticism in the Sultanate of Yogyakarta. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

1) Theosophical Association of the Netherlands Indies.

2) Unfortunately, there is no evidence showing which strata of society they came from.

3) Van Motman (1912, 123–124). See also J. M. (1922, 21) and Khan (1922, 66).

4) Si pitjik (1926, 104). Confucianist Chinese also called him Goesti, Thian, Monade, Kristus (Christ), and Allah when referring to one and the same God who brings salvation. See N. (1927b, 124).

5) A similar view was mentioned by S. Si pitjik (1926, 104).

6) Another Muslim member wrote, “. . . adanja tjela menjtela dari sesoetoe fihak kepada lain fihak itoe tiada lain tjoema terbawa dari koerang fahamnja masing-masing, atau oleh karena marika itoe beloem menjelidiki maksoednja agama-agama tadi sehingga tertib” [condemnation among people comes from a lack of understanding or because they have not yet investigated the meaning of their religion] (Broto 1926, 125).

7) On the whole, the objective is God. See also Baehler (1917, 52) and Labberton (1917, 161) etc.

8) This statement is reiterated in all ITS publications; here religion is not in its common understanding or as set of system (Tjitro 1915, 121–122; Latief 1925, 189–190). There have been accusations that Theosophy is a new religion that misleads Muslims, Christians, Hindus, and others. However, according to Latief, those accusations are not based on facts. See Latief (1926b, 31).

9) Labberton (1912, 126–127). This statement of Labberton is a hint that ITS during that time, at least from Labberton’s point of view, was used as a means of “ethical politics” by the Dutch colonial regime to stifle the resistance of Indonesians (believers).

10) Santri is an old term that originally meant a student of religion, such as a student at a pesantren (Islamic boarding school, the place of santri). A santri is a devout or pious Muslim/student who practices shari’ah. Normally, santri also called as putihan or kaum putih, the white ones as opposed to abangan, the red/brown sort (Ricklefs 2006, 36).

11) Abangan are nominal or non-practicing Muslims. This term derives from the Low Javanese (ngoko) word abangan, meaning the color red or brown. According to Ricklefs, it was only in about the mid-nineteenth century that there emerged in Javanese society a category of people defined by their failure—in the eyes of the more pious—to behave as proper Muslims. At the time, the usual terms were bangsa abangan (red/brown sort) or wong abangan (red/brown people). Abangan originated as a term of derision employed by the santri or the pious putihan, the “white ones” (Ricklefs 2006, 35).

12) Wali Songo (Javanese, literally “Nine Saints”) are well-known in the spread of Islam in Java in the fifteenth–sixteenth centuries. They were the Islamic leaders at the time of Islam’s arrival in Java. The Nine Saints were revered as Islamic scholars because not only did they possess great knowledge on religious affairs, they also possessed spiritual powers. The Nine Saints were Maulana Malik Ibrahim (Sunan Maulana), Sunan Ampel (Raden Rahmat), Sunan Bonang (Raden Makhdum Ibrahim), Sunan Giri (Raden Paku or Raden Ainul Yaqin), Sunan Drajat (Raden Syarifuddin), Sunan Kalijaga (Raden Mas Syahid), Sunan Kudus (Sayid Ja’far Shadiq), Sunan Muria (Raden Umar Said), and Sunan Gunung Jati (Syarif Hidayatullah).

13) Sheikh Siti Jenar, also known as Sitibrit, Lemahbang, or Lemah Abang, is well known in Java as a mystic who professes the idea of the Arabic hulul or ittihad, or in Javanese Manunggaling Kawulo Gusti (the union of God and man). No one knows the exact time of his birth and death, but the Javanese believe that he lived in the sixteenth century along with Wali Songo. For the Javanese people, according to Munir Mulkhan (2003), the existence of Siti Jenar and his mystical teachings symbolizes the struggle between philosophy, mysticism, and shari’ah (Islamic law) in the transition of political power from Javanese Majapahit to Raden Fatah Islam in Demak, Central Java. Siti Jenar’s doctrines, especially the doctrine about Manunggaling Kawulo Gusti considered against the shari’ah teachings of the Wali Songo. That is why that the Wali Songo as a part of political power of Demak Islam decided to execute Siti Jenar. According to Massignon (1975), Hallaj’s teachings on hulul and his death as a martyr had a significant influence on the process of Islamization in Southeast Asia, especially Java, particularly in the case of Siti Jenar. Jenar is considered to have suffered a similar fate as Hallaj. According to Soebardi (1975), Shaikh Siti Jenar was in fact a Javanese al-Hallaj.

14) Sheikh Ahmad Mutamakkin was well-known in central Java in the eighteenth century as a controversial mystic, both regarding to his existence as historical figures or fictional, and his mystical teachings. The only source that popularized Mutamakkin is Serat Cabolek, a book written by Yasadipura I (1729–1803), the renowned court poet during the reigns of Pakubuwana III (1749–1803) and Pakubuwana IV (1788–1820). Wieringa (1998) points out that in the Serat Cabolek, Mutamakkin is described as a teacher of mysticism who disregarded the shari’ah (Islamic law). He lived in the village of Cabolek, on the northen coast of Java. As he deliberately violated Islamic law, his behavior caused a scandal among pious Muslim. However, according to Milal Bizawie (2002), Serat Cabolek is the only story that has been used to discredit Mutamakkin. In fact, Teks Kajen (Kajen text) and Arsh al-Muwahhidin, the work of Mutamakkin himself, show that Ahmad Mutamakkin was a Muslim mystic who had greatly respected the shari’ah. However, most Javanese Muslims believe that he really existed.