Contents>> Vol. 9, No. 1

De-commercialization of the Labor Migration Industry in Malaysia

Choo Chin Low*

* History Department, School of Distance Education, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang 11800, Malaysia

e-mail: lowc[at]usm.my

DOI: 10.20495/seas.9.1_27

This paper focuses on irregularities as a result of the privatization of migrant worker recruitment and the unregulated activities of outsourcing companies, created by the institutionalization of the outsourcing system. Using Malaysia as its case study, this paper examines the strategies utilized by the government to de-commercialize the migration industry by phasing out intermediaries and turning to a government-to-government (G2G) approach. Eliminating the business aspect of the industry signifies a fundamental change in the government’s conceptualization, that is, labor migration should be framed as a long-term economic development issue rather than a national security threat. Enforced since 1995 and updated in 2010, the official policy to phase out agents has not eliminated employers’ and workers’ dependence on intermediaries, a historically rooted practice. The findings show that attempts to de-commercialize recruitment in Malaysia have led to monopolization of the industry and an increase in employers’ hiring costs and migrant workers’ application processing fees.

Keywords: de-commercialization, G2G, irregularities, labor policy, Malaysia, migration industry

Introduction

This paper defines “de-commercialization” as a systematic attempt by governments to remove the business incentive of the labor migration industry. As shown in the Malaysian case, the government has attempted to discipline the market actors by freezing the outsourcing system, turning to the government-to-government (G2G) approach, digitalizing the recruitment process, replacing agents with government-appointed vendors, strengthening law enforcement on agents, and shifting the liability to employers. Although there is a lot of information on how commercialization has led to irregularities in Malaysia, there is considerably less knowledge about efforts to de-commercialize the industry. The Malaysian case study prompts a few questions: Why have the government’s de-commercialization initiatives been unsuccessful? What are these initiatives’ implications for the market actors? How does the shift to de-commercialization impact the state’s gatekeeping strategy? How has irregular migration been beneficial or harmful to the host country?

Malaysia’s long-standing battle against irregular migration calls for a thorough analysis of the myriad factors contributing to the persistence of this phenomenon. The Immigration Department has reiterated its pledge to free Malaysia from irregular migrants by intensifying its enforcement operation called Ops Mega 3.0, targeting both errant employers and irregular migrants, beginning July 1, 2018 (Star Online, July 21, 2018). The government’s continuous operations against employers and irregular migrant workers have prompted extensive criticism for overlooking the role of commercial brokers and intermediaries. In response to Ops Mega 3.0 nationwide raids, over a hundred civil society organizations and migrant groups issued a joint statement “calling for an immediate moratorium” on the operations. According to the joint statement, the affected migrants’ status of irregularity was due to the systemic existence of trafficking networks in Malaysia, deception by agents, exploitation by employers, and the complex commercial chains of private outsourcing companies. Becoming undocumented was primarily an outcome of the illegal activities of trafficking syndicates and employment agents (Civil Society Organisations 2018).

After the change in political leadership in May 2018, industry players and trade associations wanted the new Pakatan Harapan government to formulate a clearer foreign worker policy. They maintained that all stakeholders should be involved in devising an all-encompassing policy on foreign worker recruitment. While they agreed that law enforcement was necessary, they reminded the authorities not to neglect the various sectors’ needs for foreign workers (Kong 2018). There were at least two irregular workers for every legal worker employed by companies. It was estimated that four million undocumented migrants worked in various industries.

According to employer associations, the high number of irregular foreign workers may be traced to third-party agents who have brought in an excessive supply of such workers. Tracking down irregular migrant workers would cripple the country’s economy. Instead of targeting employers and irregular workers, the government is urged to address the root cause of irregularities—the involvement of third-party agents. One hundred members of the Federation of Malaysian Manufacturers signed a petition to the Ministry of Home Affairs (MOHA), urging the government to investigate the operations of government-appointed outsourcing companies, which have failed in their responsibility to ensure “the sound management of imported labour” (Teh and Shah 2018).

Shifting the attention to brokers and outsourcing companies as key players that produce and sustain irregular migration is significant in three ways. First, it addresses a long-standing problem in the privatization of recruitment and the institutionalization of the outsourcing system. The recruitment model in Malaysia is based on the business-to-business (B2B) approach by third-party agents (recruiters, outsourcers, and labor intermediaries). Due to its business nature, the B2B approach entails high costs as it involves several agents and subagents in countries of origin and destination, generating “gains that mostly favor third-party intermediaries” (World Bank 2015, 56). Various reports document that exorbitant costs charged by third parties incentivize existing documented workers to overstay after the expiration of their work permits in order to pay off their debts and potential workers to join underground employment (SOMO 2013, 6; Verité 2014; ILO 2016, 13). The main question is whether the government is committed to controlling, reducing, and eventually discontinuing the practice of outsourced contract labor that affects workers’ rights.

Second, the shift has serious policy implications for migration control strategy. To remove the business incentive, the state has moved toward de-commercialization of the industry by phasing out private agencies and turning to the G2G state-operated mechanism. Eliminating the role of outsourcing companies and intermediaries is outlined in the 11th Malaysia Plan (2016–20) for national economic development as part of the reform to improve the management of foreign workers (Malaysia, Economic Planning Unit 2015, ch. 5). Eliminating the intermediaries’ role complements centralizing the regulatory infrastructure and digitalizing recruitment through an online platform. Ideally, this move has allowed the government to regain control over the recruitment process and profits gained while cutting intermediaries and corruption among officers.

Third, with the diminishing role of intermediaries, the state reinforces internal gatekeeping by making employers fully responsible for the recruitment and welfare of their foreign workers under the newly introduced strict liability program. Internal gatekeeping in the labor market and in underground employment is important because irregular migration is driven by both pull and push dynamics involving various migration industry actors (Triandafyllidou and Ambrosini 2011, 272). Irregularities are explained by using different frameworks: the role of intermediaries in the migration industry, restrictive immigration policies, and structural causes related to uneven development between the Global North and the Global South (Castles 2004; Koser 2010).

This paper builds on the literature about the migration industry. John Salt and Jeremy Stein conceptualize “migration as a business.” They argue, “The migration business is conceived as a system of institutionalized networks with complex profit and loss accounts, including a set of institutions, agents and individuals each of which stands to make a commercial gain” (Salt and Stein 1997, 467). This conceptualization has significant policy implications because it shifts the attention of policy makers to “the institutions and vested interests involved rather than on the migrants themselves” (Salt and Stein 1997, 468). Governments’ migration management is part of the business, and their control policies are aimed “at making an investment in managing the business for a worthwhile return” (Salt and Stein 1997, 468). The literature on the migration industry focuses on irregularities created by the commercialization of the business and how various actors profit from the industry. With the increasing commercialization of migration, the industry actors’ role is gaining significant traction. Actors include transnational companies providing migration management services, recruitment agencies facilitating access to legal migration, networks set up by migrants themselves, human smuggling networks, non-governmental organizations, and migrant associations (Sørensen and Gammeltoft-Hansen 2013, 9–10). Conceptualization of the migration industry is important in understanding “how migration is fostered, constrained, shaped and assisted” (Cranston et al. 2018, 545).

Various forms of transnational migration, including labor migration, involve intermediaries (Fernandez 2013; Groutsis et al. 2015; Ambrosini 2017; Harvey et al. 2018). In the Asian migration industry, the intermediaries’ role has historical roots. Migrants almost never approach the appropriate government agency directly, preferring an informal labor recruiter (field agent) (Lindquist 2010, 125). Examining the Indonesian migration industry, Johan Lindquist (2010) argues that historically specific environments have created the space for informal brokers, who mediate between formal recruitment agencies, bureaucracies, and villages. An informal brokerage system (existing in parallel with formal channels) is necessary in the midst of capitalism, state power, and local economies of trust (Lindquist 2010, 132). In investigating migration regimes across Asia, it is important to include the role of migrant brokers. According to Johan Lindquist, Xiang Biao, and Brenda S. A. Yeoh (2012), examining the brokers’ role is an approach used to understand the “black box” of migration. These authors remind readers of the importance of focusing on the migration infrastructure, including institutions, profit-oriented networks, and people, that determines the mobility of migrants: “By focusing on those who move migrants rather than the migrants themselves it is possible to more effectively conceptualise the broader infrastructure that makes mobility possible” (Lindquist et al. 2012, 9). Brokers and the infrastructure occupy the “middle space of migration” that makes mobility possible (Lindquist et al. 2012, 11).

In their research on low-skilled labor migration from China and Indonesia, Xiang Biao and Johan Lindquist (2014) call for the clear conceptualization of migration beyond state policies, the labor market, or migrant social networks. As labor migration is intensively mediated, focusing on the concept of a commercial infrastructure (institutions, intermediaries, market actors, and technologies) would unpack the process of mediation (Xiang and Lindquist 2014, 122). Rather than migration being conceptualized as a journey between two places, it is viewed as a “multi-faceted space of mediation occupied by commercial recruitment intermediaries” (Xiang and Lindquist 2014, 142). Migration brokerage is a huge business. Brokers have played a significant role in the middle space of migration, facilitating recruitment, connecting people, establishing networks, and making migration safer. In contrast to the stereotype of unscrupulous brokers, Alice Kern and Ulrike Müller-Böker find that brokerage and recruitment agencies have contributed to securing new means of livelihood for people and fostering the development of countries (Kern and Müller-Böker 2015, 158).

Moving beyond contemporary debates in migration studies, this paper surveys the development of the government’s attempt to de-commercialize the migration industry, using Malaysia as the case study. First, it investigates how the institutionalization of the outsourcing system has led to irregularities, as well as highlights the role of the migration industry. Second, the paper examines the government’s initiatives to phase out intermediaries and to regain control of the process under a state-operated mechanism, considering the challenges encountered. Finally, it analyzes the implications of the state’s migration policies for the nation.

The de-commercialization approach of the labor migration industry is not unique to Malaysia. In the Asian context, the market-driven recruitment system has been gradually replaced by a government-regulated system. Other labor-receiving countries have attempted to eliminate private agents from the recruitment process, such as South Korea implementing the Employment Permit System (Vandenberg 2015, 2; Migrant Forum in Asia 2017, 2–3). Applying the working framework in the Malaysian case, this article seeks to contribute to a better understanding of Malaysia’s migration industry. Despite efforts to de-commercialize the industry, the initiatives have resulted in business monopolization by some authorized companies and an increase in employers’ hiring costs and migrant workers’ application processing fees. The analysis draws on Hansard documents (between 2005 and 2017), legislation, official reports by migrant groups, press releases, English-language newspaper articles, and secondary literature.

Literature Review

Much of the literature on Malaysia’s migration industry is highly critical of the development of the state-sponsored outsourcing system. Migration scholars suggest that irregularities in Malaysia are created by the privatization of recruitment. The business aspect is reinforced at the institutional level through the institutionalization of the outsourcing system. In examining the migration industry in the Indonesia-Malaysia corridor, Ernst Spaan and Ton van Naerssen find that industry actors—whether formal or informal—are thriving due to the changing context of government policies (Spaan and van Naerssen 2018, 680). The government has delegated some of its immigration functions to non-state actors, creating much space for licensed recruitment agencies in labor migration management. The migration industry system consists of formal, licensed recruitment companies and informal networks, both of which are intertwined. The thriving of informal migration industry networks is attributed to the weak regulatory framework (Spaan and van Naerssen 2018, 690–691). Migration industry actors are incorporated by the Malaysian state in its immigration management as it has outsourced some immigration functions to private actors. In their work on Burmese labor migration to Malaysia, Anja Franck, Emanuelle Brandström Arellano, and Joseph Trawicki Anderson show that private actors are also important to the migrants themselves as “means to increase their room to maneuver during the migration process” (Franck et al. 2018, 55).

Sidney Jones convincingly shows how various actors in the Indonesian-Malaysian migration industry have profited from the recruitment process, ranging from the lucrative people-smuggling businesses, the profitable black market document industry, and corruption in both countries to employers hiring undocumented workers (Jones 2000, 35, 89). Informal recruitment (taikong) with the help of local agents is largely responsible for clandestine entries and the smuggling of undocumented workers (Kassim 1997, 57). The persistence of underground employment is due to the business aspect of the industry: “Economically, illegal entry and recruitment of foreign labour generate a lot of business for traffickers, landlords, exploitative employers, and suppliers of false documents” (Kassim 1997, 67). Azizah Kassim attributes this phenomenon to the ineffective enforcement of laws against Malaysian citizens’ harboring and employment of undocumented migrants (Kassim 1997, 76). Market actors, including agents and outsourcing companies, are part of an integrated migration system. Alice Nah blames the irregularity on “the lack of attention to the institutions, processes and actions that stimulate irregular migration” (Nah 2012, 490).

The severe labor shortage in certain industries, the economic disparities between Malaysia and the countries of origin, the tradition of travel in the Malay Archipelago, and geographic proximity have all explained the emergence of formal and informal recruitment agencies. According to Blanca Garcés-Mascareñas, “their presence must be understood not only as a way of channeling migration flows, but also as a mechanism that promotes them” (Garcés-Mascareñas 2012, 49–50). The privatization of recruitment has a twofold effect: (1) increasing the cost of legal migration, thus making the legal channel an unattractive option; and (2) contributing to the incidence of irregularities. Upon entry into Malaysia, many legal migrants join the ranks of illegality due to various malpractices of recruitment agencies, such as recruiting without definite employment and bringing in workers under forged permits (Garcés-Mascareñas 2012, 72–73).

The existence of labor brokerage in Malaysia may be traced to the British colonial era. The relationship between the colonial state (as the regulatory agency), labor brokers, and employers in the migration infrastructure was well established in the historical context. The British colonial power created migration corridors across Malaya, India, and China, encouraging labor mobility in Southeast Asia (Kaur 2012, 225–226). Private labor brokers played an important role in recruiting Indian plantation workers under the colonial recruitment methods, comprising the indenture system and the Kangani system. Under the indenture method, employers used labor recruitment firms in India (Kaur 2012, 232). Meanwhile, the Kangani system utilized existing plantation workers as brokers to recruit laborers from their villages in India. Both methods were phased out in 1910 and 1938, respectively, as the state became the broker for Indian labor recruitment as well as a regulatory agency (Kaur 2012, 233–235). Similarly, private labor brokers played a major role in Chinese labor migration through a “kinship-based” migration network in China and the contract-based credit-ticket network in British Malaya. Reports of laborer abuse attributed to the credit-ticket system for Chinese labor recruitment led to its abolition in 1914 (Kaur 2012, 239–241).

Despite the British ban on the contract-based labor system, the intermediaries’ role continued to flourish after Malaysia was granted national independence, corresponding to the growth of the country’s migration industry. Malaysia’s Private Employment Agencies Act of 1981 formalized the private labor brokers’ function of recruiting foreign labor (Kaur 2012, 244–247). Under the guest worker program and offshore recruitment procedures, foreign labor recruitment was inadequately monitored, providing fertile ground for commercial broker networks to bring in an excessive labor supply. The practice of outsourced labor led to the commercialization of the industry, with legal migrants and locals entering the migration industry market and becoming recruitment agents themselves. Contemporary legal migrants’ involvement in the underground migration industry is somewhat reminiscent of the practice of the colonial Kangani system and the credit-ticket system, whereby migrants themselves recruited workers for plantations and mines through their personal networks. The situation illustrates the entrenchment of migrant networks in the recruitment system.

Legal foreign workers are joining the underground migration industry by setting up illegal businesses, thus abusing their work permits. Illegal businesses operated by immigrants are swelling in the major central business district areas in Kuala Lumpur. Malaysian citizens sublet their licenses by charging a monthly fee, ranging from MYR1,000 to MYR2,000, whereas a license usually costs MYR100 to MYR150. Some foreigners, especially Bangladeshis and Indians, have obtained business licenses by marrying local women. Illegal businesses have negative consequences on Malaysia’s economy because foreigners do not pay taxes, creating unfair competition for Malaysians, and Malaysia suffers from monetary outflow through increased foreign remittances annually (Bavani 2017).

Legally hired immigrants are not allowed to conduct business on behalf of companies, become business owners, or have their own business premises or business entities that are against Malaysian laws. The reality is that business owners are undocumented immigrants who have stayed and worked illegally in the country for a long period. These undocumented foreign workers (Pendatang Asing Tanpa Izin) have gradually become illegal employers (Majikan Asing Tanpa Izin).

This case highlights three implications. The first involves Malaysian citizens who have hired and harbored irregular migrants. The increased number of these underground businesses is attributed to Malaysian citizens who are the license holders of the business premises. Second, the monopolization of the businesses has affected local traders. Third, illegal businesses are often related to other illegal activities, such as license abuse, illegal utility connections, premises misused for vice-related activities, and tax avoidance (Shah 2018). The extent to which these business operations occur indicates the practice of contracting marriages for business purposes. The Immigration Department has identified four hundred Pakistani men who have married local women in the state of Kelantan in order to stay longer and operate businesses in Malaysia. Most of the Pakistan nationals operate small retail stores by securing business licenses through their local spouses who are double their age (Free Malaysia Today 2019).

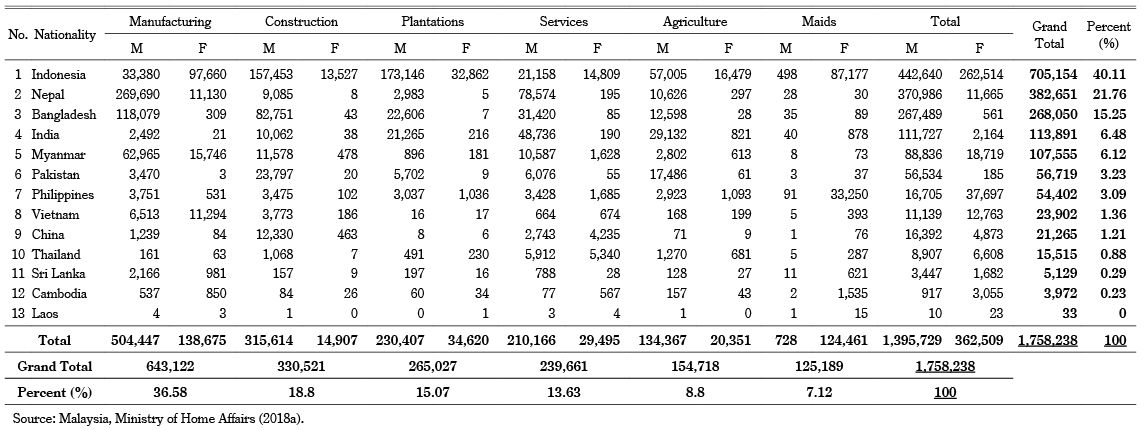

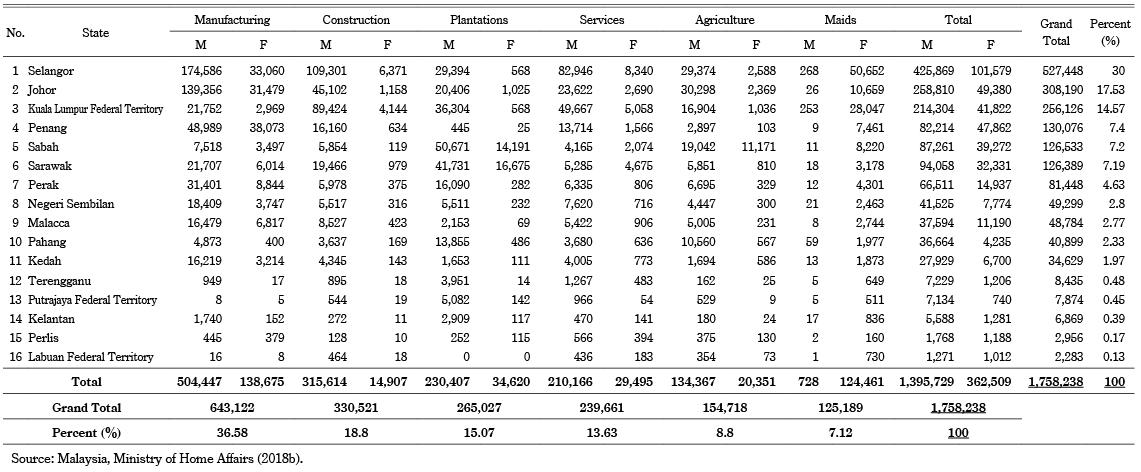

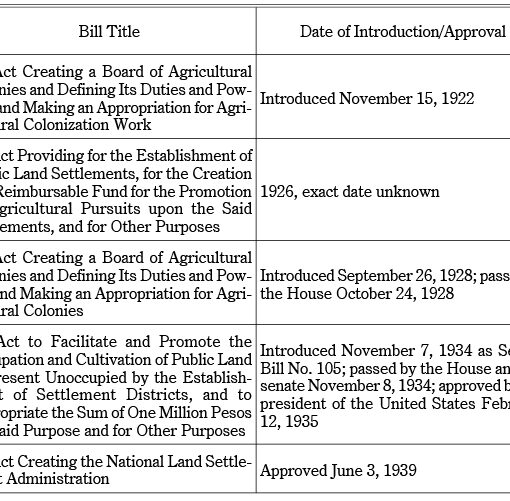

The influx of migrant workers is attributed to the high reliance on them to take low- and medium-skilled jobs, and the employers’ interest is a force to be reckoned with. There were 1,758,238 registered foreign workers in the country as of February 28, 2018, with the majority coming from Indonesia (705,154 or 40.11 percent), followed by Nepal (382,651 or 21.76 percent), Bangladesh (268,050 or 15.25 percent), India (113,891 or 6.48 percent), and Myanmar (107,555 or 6.12 percent) (Table 1). Six sectors, comprising one informal (employing foreign maids) and five formal sectors (construction, manufacturing, services, plantations, and agriculture), are allowed to employ foreign workers. The 15 source countries that are permitted to supply workers to Malaysia are Indonesia, Bangladesh, Nepal, Myanmar, India, Vietnam, the Philippines, Pakistan, Thailand, Cambodia, Sri Lanka, Laos, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan. The employment period is five years + five years for the five formal sectors. For the informal sector, foreign maids have no fixed employment period. The permitted age range of foreign workers is between 18 and 45 years (Malaysia, Ministry of Home Affairs 2019). As of February 28, 2018, foreign workers constituted a large share of the total employment in manufacturing (36.58 percent), followed by construction (18.8 percent), plantations (15.07 percent), services (13.63 percent), agriculture (8.8 percent), and domestic help (7.12 percent) (Table 2). Foreign workers were highly concentrated in Selangor (30 percent), followed by Johor (17.53 percent), Kuala Lumpur Federal Territory (14.57 percent), Penang (7.4 percent), Sabah (7.2 percent), and Sarawak (7.19 percent) (Table 2). In 2017, foreign workers represented around 15.5 percent of all employed persons in Malaysia (Khazanah Research Institute 2018, 120). The high dependence on foreign labor indicates the need for a fundamental reconceptualization of migrant labor in the policy debate by viewing labor migration as a long-term development issue rather than a security concern. Migrant labor management has sidelined the issues of third parties’ involvement and foreign workers’ exploitation, which have perpetuated the migration industry (Lee 2017, 558).

Table 1 Statistics of Foreign Workers by Nationality and Sector as of February 28, 2018

Table 2 Statistics of Foreign Workers by State and Sector as of February 28, 2018

Scholars suggest that illegality is the consequence of weak gatekeeping on the labor market front. In the Malaysian context, the gatekeeping function is rather weak in its preventive efforts, especially in labor market checks. Private agents have been able to bring in an excessive number of foreign workers, mainly due to the lack of a comprehensive assessment of labor market demand. There are no guidelines for determining the exact quotas of foreign workers needed for each industry. The quota figures are merely “guesstimates” (Abella and Martin 2016, 99). The inadequacy on the labor market front may be explained by the state’s conceptualization of migration as a “security problem that has needed a security response from the state apparatus” rather than an economic issue (Arifianto 2009, 623). According to Malaysian political discourse, migration is conceptualized as securitization. Migration is viewed as an issue of national security rather than as an industry, resulting in the consolidation of the state’s penalty regime against undocumented migrants (Liow 2003, 50). This contradiction is reflected in the regulatory mechanism itself: the MOHA rather than the Ministry of Human Resources (MOHR) is tasked with policy making on labor migration, although both institutions are involved in labor migration. Foreign workers are perceived as potential national security threats; thus, the management of foreign labor has been placed under the jurisdiction of the MOHA (ILO 2016, 11). This situation has raised questions over who the gatekeeper is and where the gatekeeping occurs.

Illegality is also the outcome of unregulated gatekeeping by employers and the legal system. Many foreigners enter the country as documented workers but later become undocumented due to the lack of redress. There is no channel for complaints for these foreign workers when they face pressure from their employers who do not comply with all the conditions stipulated in their contracts and do not pay them salaries. Employers can dismiss workers, terminate their contracts, take “check-out memos” from the Immigration Office, and book tickets for them to return to their home countries. Without any opportunity to claim their rights, terminated foreign workers either resort to the black market (refusing to return without settling their debts) or return to their home countries with debt burdens (Malaysia 2015c, 26–27). Although laws are provided for the Labor Court and Industrial Court, foreign workers have no right to redress. Employers can issue check-out memos and get away with it. The MOHA has been urged to empower avenues for foreign workers to defend themselves and their right to redress in cases of disputes with their employers (Malaysia 2015c, 28). The Immigration Act, Section 55B, states that an employer hiring five unauthorized foreign workers may be imprisoned for a term between six months and five years and whipped a maximum of six strokes (Malaysia 2006). Employers have the perception that they can get away with hiring undocumented workers. According to the Malaysian Employers Federation, imposing heavy penalties will not deter small businesses from hiring foreigners. There is always a ready supply of undocumented workers, and employers are willing to take chances in hiring them to remain competitive (Shurentheran 2017).

The overflow of undocumented workers is caused by the privatization of recruitment. According to MP Michael Jeyakumar Devaraj, “It’s the business aspect of it that lets a lot of unscrupulous agents who make promises to bring people in and then let them loose in the sense that they can’t go back because of their debts” (Abu Bakar 2017). Employers are often depicted as being “forced” to hire from the readily available pool of undocumented immigrants in order to remain competitive. If employers hire local workers and pay them minimum wages in accordance with the law, they cannot compete with their peers who hire undocumented workers. Partly due to weakness in the law enforcement on employers and partly due to over-recruitment by employment agencies, the cycle continues (Abu Bakar 2017). Permits granted to outsourcing companies without adequate control lead to a “race to the bottom,” in which firms compete against one another by cutting costs as much as possible and paying the lowest wages to remain competitive. The government has thus been urged to revert to a state-operated mechanism (Malaysia 2014, 79–80).

The flow of irregular migrants have deeply impacted the wages and job opportunities of local workers. The labor market structure favors hiring undocumented workers in the very first place, discriminating against Malaysian workers. Employing local workers is more expensive because employers have to pay them the minimum wage of MYR1,000 per month (as of July 2016) and 13 percent of the Employees’ Provident Fund contribution. For foreign workers, the levy is deducted from their salaries, as stipulated in their contracts. Foreign workers are silent if they are not paid the 1.5 overtime rate. The ready supply of foreign workers and the labor market structure explain employers’ reluctance to hire local workers. To eliminate the wage inequality, the costs of employing foreign and local workers must be equal (Malaysia 2015d, 61–62). As pointed out by MP Devaraj, an analysis of the problem of irregularities should consider the issue of who benefits and who suffers from the arrival of foreign workers. Those who gain from the presence of foreign workers are employers, agents, labor contractors, and perhaps corrupt immigration officers who receive high commissions. The top 10 percent (T10) have profited from this situation, while foreign workers and the lower income group or the bottom 40 percent (B40) of Malaysian households have suffered the consequences. Approximately 75 percent of the B40 consists of the Malay community (Malaysia 2015c, 27–28).

Although much has been written regarding how commercialization of the migration industry has led to irregularities in Malaysia, there is considerably less information about efforts to de-commercialize the industry. Building on the above literature, this paper discusses shifts in government policy since the first decade of the twenty-first century to remove the industry’s business incentive. Next, this paper explains a few government initiatives for de-commercialization, including freezing the outsourcing system, turning to the G2G approach, digitalizing the recruitment process, changing the gatekeeper orientation, replacing agents with government-appointed vendors, strengthening law enforcement on agents, and renegotiating memorandums of understanding (MoUs) with labor-supplying countries in ASEAN.

De-commercialization of the Migration Industry in Malaysia

Freezing the Outsourcing System and the Setback

The government has attempted to abolish the use of outsourcing agents throughout the history of Malaysia’s migration regime. In 1995 the government made the radical move to ban agencies from bringing in foreign workers (except domestic workers) and to reduce the number of licensed Malaysian recruiting agencies (169 at the time). This policy paralleled the Indonesian Ministry of Manpower’s policy of reducing its licensed recruiting agencies (Jones 2000, 29). The state became the sole institution authorized to recruit. In 1995 a Special Task Force on Foreign Labour was set up in the MOHA as the sole agency responsible for foreign labor recruitment. This was tantamount to establishing the state’s direct management of foreign worker recruitment, taking over the regulatory functions from licensed employment agencies. During this period, the Immigration Department’s function was expanded to deal with policy making on foreign labor recruitment (Kaur 2012, 248–249). The G2G model was implemented when recruitment was centralized in the country. A G2G agreement was made with Indonesia. A subsidiary company (Peti Bijak) was created in Indonesia. However, all the G2G efforts eventually failed. The Malaysian government was forced to accept that the recruitment industry involving private employment agencies (PEAs) was a multimillion-ringgit business. It was difficult to control the industry (Malaysia 2005, 20).

As a result, the Private Employment Agencies Act of 1981 was amended in 2005, re-legalizing recruitment agencies and institutionalizing an outsourcing system. The previous policy of de-recognizing private agencies did not solve the problems with foreign workers as employers continued to use their services. It was even more difficult to control the activities of private agencies due to their lack of recognition. Under this system, outsourcing companies were the legal employers of migrant workers (Garcés-Mascareñas 2012, 71). However, both employers and outsourcing companies tended to avoid fulfilling their responsibilities to foreign workers. This situation compelled the state to revert to the G2G system, so that employers would be accountable. In 2010 the government decided to phase out outsourcing firms in line with its initiatives to replace intermediaries with G2G agreements. No new licenses were granted to outsourcing companies; the number of outsourcing agents was thus controlled (World Bank 2015, 68). The government decided that assessing the performance of the 276 outsourcing companies would be necessary. It could no longer allow profit-oriented outsourcing companies’ disregard for their social responsibility, causing a negative impact on national security and public order. Controlling outsourcing agency activities would be essential to ensure that these companies would not worsen the situation with an excessive supply of foreign workers (Malaysia 2010, 33).

Though the outsourcing system was terminated, the practice of outsourcing workers continued in another form. The government institutionalized its outsourcing system when it amended the Employment Act of 1955 in 2012. This landmark amendment blurred the legal employment relationship between employers and workers by introducing the concept of a “contractor for labor.” A drawback of the concept was the distancing of employers from any liability for migrant workers (Devadason and Chan 2014, 27; World Bank 2015, 56). Contractors for labor included outsourcing agents, brokers, PEAs, and other third parties that supplied outsourced workers to employers (principals of workplaces). Outsourced workers were legally not employees of the principal of a workplace. The amendment did not “advocate a permanent direct employment relationship between employers and workers” (Syed Mohamud 2012). Moreover, workers had no right to be members of a trade union and hence were unable to benefit from collective agreements. For the Malaysian Trade Union Congress, PEAs could still supply workers, but these workers had to be hired as employees of the workplace with similar benefits (Syed Mohamud 2012). Principal employers left the responsibility to determine contract workers’ terms and conditions of employment to the contractors as long as their demand for labor was met. Based on a survey conducted on employers, contractors, and contract workers in 1993–94, Lee Kiong Hock and Alagandram Sivananthiran concluded that less than 10 percent of the contractors provided welfare benefits to contract workers (Lee and Sivananthiran 1996, 80–82). There were no written contracts, and contract workers were denied most of the benefits stipulated under labor laws (Lee and Sivananthiran 1996, 89).

During the second and third readings of the Employment (Amendment) Bill it was widely criticized, mainly due to its serious implications for workers’ rights, particularly workers employed by contractors for labor. There were 277 outsourcing companies, and outsourced workers were not limited to foreign workers but included local ones. First, there was no security of tenure, a key principle of the International Labour Organization (ILO). This amendment elicited insecurity because of the uncertainty in the contract workers’ future employment prospects. Security of tenure ensured the existence of protection. Second, there was a proprietary right to jobs; workers could not be dismissed for no valid reason. However, the amendment triggered uncertainty because factory owners were not the employers (Malaysia 2011b, 97). Most important, the introduction of contractors for labor brought back the Kangani system used during the British colonial era. The bill legalized the old system that had been banned by the British colonial power under the 1955 Employment Act. The original 1955 Employment Act issued by the British consisted of two important principles—security of tenure and proprietary right to the job. However, the amended act legalized the practice in which workers could be employed by a contractor for labor and be brought to a factory whose owner was not the employer. Their condition was uncertain. Their fate was uncertain (Malaysia 2011b, 98). In terms of protecting foreign workers’ rights, the legislation would be a black mark in Malaysia’s labor history. The parliament brought back the long-abolished system by issuing the amended act (Malaysia 2011b, 99).

There were perceptions that the responsible ministry had transferred its responsibility to outsourced companies, disregarding migrants’ protection and welfare. The principal company had no responsibilities to the workers, was not liable to them, and in fact was not their employer. A parliamentarian asked, “I would like to ask the Minister how the contract of service can be established as between the contractor of labor and workers when the contractor of labor is not the owner operator” (Malaysia 2011b, 112). The Employment (Amendment) Act of 2012 framed foreign worker recruitment as a business. Migration has become a lucrative industry; people can make profits from recruiting workers. The contractor system has undermined the protection of workers and is regarded as anti-labor legislation (Malaysia 2011b, 110). The issue of the outsourcing system having been created to generate profit for certain parties has been brought to the forefront of parliamentary debates:

It in fact showed we are allowing foreign workers to work, not with the intention to help the economy but as a business. Many of the outsourcing companies that were allowed to bring foreign workers are the cronies of politicians. It’s all licensing to profit. (Malaysia 2016b, 92)

The cases of Bangladesh and Nepal, as discussed in the next section, show the limitations of the privatization of recruitment. Under the private management of Bangladeshi workers in 2007–8, unscrupulous agents’ recruitment malpractices—including corruption, joblessness, low wages, non-payment, and poor living conditions—resulted in an excessive number of Bangladeshi workers being sent to Malaysia. Many ended up jobless or in unpaid short-term jobs and eventually returned home. In 2009 Malaysia canceled 55,000 visas and imposed a four-year ban on recruitment from Bangladesh. Concern over maltreatment by Malaysian employers prompted the Bangladeshi government to initiate the G2G mechanism (Palma 2015; Tusher 2016).

The Malaysian government failed to equip itself with the necessary capability to control foreign workers from Indonesia through G2G. Leaving the problem unsolved, the Malaysian government adopted the G2G approach with Bangladesh and Nepal.

Turning to G2G Bilateralism

The G2G recruitment arrangement with countries of origin eliminated the involvement of private agencies. The MoU signed by Malaysia and Bangladesh in 2012 was significant in two aspects—it removed the involvement of private agencies and included the Online Application for Employment of Foreign Workers (Malaysian acronym SPPA), thereby eliminating the workers’ incentive to overstay in order to settle their debts (ILO 2016, 15–16). The SPPA was introduced in February 2017. The MoU stipulated that the entry of Bangladeshi workers was allowed only through G2G mechanisms. The admission process was approved by the respective government agencies in both countries and did not involve third parties. Job seekers underwent health screening for 18 types of diseases, a security screening process, and induction training to ensure that only candidates who were qualified and met the set criteria were shortlisted to be sent to Malaysia. Similarly, the Malaysian government implemented strict screening of employers applying to hire workers. The government rejected some plantation companies for not complying with the minimum wage requirement and the provision of standard homes, as well as those with records of law violations (Malaysia 2013, 1–2).

However, the G2G effort was rendered ineffective by the lobbying of private sector agents in Malaysia because it deprived them of millions of taka and ringgit that they were earning through the B2B system. Only ten thousand Bangladeshi workers were hired, although Malaysia had a target of recruiting thirty thousand. The G2G model was unpopular among agents and employers, who preferred hiring through the private sector. This state of affairs pointed out “the inefficiency of the government in handling the business” (Palma 2015). The failure of the G2G approach led both governments to set up the G2G Plus deal to recruit 1.5 million workers over the next three years, replacing the G2G agreement signed for 2012–14. Private firms were allowed to send workers to Malaysia through the government arrangement under the G2G Plus deal signed in 2016. Employers were held responsible for workers’ security deposits, levies, visa fees, and health and compensation insurance, in addition to the MYR1,985 expatriation cost for each worker (Carvalho 2016).

The issue of bringing 1.5 million Bangladeshis into the country was debatable. The (mis)perception was that the government was not serious about eliminating irregular immigration because it was about the money trail. Besides the money chain, some parties benefited from the involvement of syndicates in the transnational border crossing. According to the government, these syndicates tried to outsmart law enforcement, and it was unfair to allege officers’ involvement. As a result of the widespread misconception, the government introduced the online application system to remove the roles of agents and syndicates (Malaysia 2015d, 56). A parliamentarian pointed out, “The entry of foreign workers is a profitable business. Bringing in foreign workers, 1.5 million from Bangladesh workers with MYR3,000 per head, how much profit is there? It is deemed as ‘human trafficking,’ but it is a legal trading” (Malaysia 2015d, 59). For the MOHA, the purpose behind hiring 1.5 million workers was to enable the deportation of the existing undocumented workers. The request for Bangladeshi workers came from the employers’ associations themselves. Bangladeshi workers were preferred because they were deemed more trustworthy than other foreign workers (Malaysia 2015d, 59).

Another related matter was the MOHA’s questionable adeptness in handling the issue of foreign worker recruitment. According to then Human Resources Minister Richard Riot, only 2,948 workers were hired through the G2G in 2015. In 2016 the number dropped to seven persons under the G2G Plus mechanism, reflecting the ineptitude of the system. The MOHR has been urging the government to centralize the recruitment and employment of foreign workers (currently under the jurisdiction of the MOHA) under the MOHR. The MOHR believes that, as the ministry responsible for the workforce, it should take the lead in employment affairs. The task should not be divided between these two ministries, in order to facilitate enforcement and fulfillment of access to labor market needs (Malaysia 2017a, 55–56).

Most important, private recruitment agencies perceived the G2G Plus deal as a form of business monopolization by a Malaysian private company. The agencies represented by the Bangladesh Association of International Recruiting Agencies (Baira) protested to Bangladesh’s prime minister because the deal effectively eliminated all Baira members from the recruitment business, while allowing the Malaysian syndicate to generate profits with its affiliated companies. The monopolization in the Malaysian case was unique as there was no foreign company monopolization in the other 139 countries in which Baira was involved (Star Online, February 18, 2016). The concerns over Malaysia’s possible business monopolization were justified. Under the G2G Plus deal, hiring was done online through the SPPA, which referred employers to 10 companies that had been designated as sole authorized agents, closing the door to about 1,500 recruitment agents in Bangladesh. Bestinet Sdn Bhd, a private company that operated the SPPA, functioned as the service provider for the distribution of workers to their employers via the 10 companies. A local news media company, Star Online, reported the involvement of a human trafficking syndicate that earned MYR2 billion through the recruitment of Bangladeshi workers. The industry involved a multitude of intermediaries. Of the MYR20,000 paid by each worker, MYR2,500 was pocketed by a subagent who was connected to another subagent from the worker’s village, who also took MYR2,500; one of the 10 companies then charged MYR10,000, and MYR3,000 was given to a local Malaysian agent. The whole employment process cost only MYR2,000 (Perumal 2018a).

In June 2018 the new Malaysian government suspended the G2G Plus deal along with the 10 authorized companies for recruiting Bangladeshi workers. The new human resources minister, M. Kulasegaran, announced the suspension pending a full investigation. The entire recruitment process under the G2G Plus deal was perceived as a “business aimed at benefiting certain individuals,” and the process was “a total mess” (Star Online, June 22, 2018). The SPPA was also suspended effective September 1, 2018. The decision broke the monopoly of the 10 authorized companies, offering relief for 1,500 recruitment agencies in Bangladesh, and Malaysian employers were no longer required to pay MYR305 as the SPPA registration fee (Perumal 2018d).

Similar to the Bangladeshi case, the recruitment of Nepalese workers was beleaguered by the problem of monopolization, in addition to red tape and bureaucracy. The recruitment mechanism was overly complex, involving various government-appointed private agencies charging high fees as part of the visa requirements. In May 2018, Nepal barred its workers from going to Malaysia due to the exorbitant visa fees. The temporary moratorium resulted in fifteen thousand to twenty thousand workers being left in limbo. The new Nepalese government demanded the revocation of private companies, streamlining the existing complex mechanism, and reducing visa costs (New Straits Times, August 2, 2018). Due to a private company’s (Bestinet Sdn Bhd) virtual monopolization of the processing of Nepalese applicants’ work visas, other companies were not allowed in the business. Malaysia has been highly dependent on Gurkhas (native soldiers) from Nepal to work in the security line. In 2018, of the approximately half a million Nepalese workers in Malaysia, 150,000 were hired as security guards (Perumal 2018b). As a result of the controversy surrounding Bestinet’s monopolization, the company was suspended by the Malaysian government in August 2018, pending a new MoU with Nepal. Malaysia would sign a new G2G agreement with Nepal, based on the model used with Bangladesh (New Straits Times, August 14, 2018). The new Pakatan Harapan government would scrap the G2G Plus deal, formulated by the previous Barisan Nasional government, and revert to direct recruitment based on the G2G agreement without any intermediaries (Star Online, July 29, 2018).

Centralization of recruitment under a sole private agency, as in the cases of Bangladesh and Nepal, showed that it was problematic to the source countries. It created “a monopolistic situation,” prevented open competition, and weakened labor relations with the source countries (Rahim 2018a). Outsourcing companies had not been allowed to manage foreign workers since 2010, and many such companies closed their businesses. The Malaysian Association of Suppliers and Employees Management of Foreign Workers, comprising 149 licensed outsourcing companies whose market opportunity had been closed by the previous government, hoped that the Pakatan Harapan government would allow open competition and engage the expertise, capability, and experience of outsourcing companies (Perumal 2018c).

In October 2018 the new Pakatan Harapan government announced the abolition of the outsourcing of foreign worker recruitment effective March 31, 2019. In the government efforts to curb human trafficking and workers’ exploitation, intermediaries and agents would no longer be allowed to hire workers. The joint committee from the Home Ministry and the MOHR decided that the task of foreign worker recruitment, previously handled by about a hundred outsourcing agencies, would be taken over by the MOHR (Zainal 2019).

Digitalizing the Recruitment and Permit Renewal Process

Another initiative taken to phase out agents was replacing the manual process conducted at the immigration counters with an online platform. The shift to digitalization was perceived as an anti-corruption, agent-free, and cost-effective policy. Digitalizing some immigration functions was an important milestone toward the de-commercialization of the industry by gradually diminishing the agents’ role. The bureaucracy involved in the manual application allowed agents to act as intermediaries, enabling them to earn huge profits. Throughout Malaysia, the process could be conducted only at the immigration headquarters, Putrajaya. Employers who abided by the law were forced to line up as early as 3 a.m. to apply for foreign workers’ permits at Putrajaya. After the daily quota was filled, those still in line had to return the next day. The government was thus urged to change the application process to an online system (Malaysia 2016d, 51). More employers were hiring workers without permits because of the rigidity of the manual system. When the employers did not renew expired permits, their workers became overstaying aliens. As penalties, the law stipulated a fine of up to MYR10,000, six months in jail, and whipping—but not all were applicable. It had become a state of affairs “that [indicated a] total collapse of the law” (Malaysia 2016c, 34–35).

The Foreign Workers Centralised Management System (FWCMS) was introduced on June 15, 2015 to process applications for foreign worker visas and health status clearances. The Malaysian Immigration Department’s move toward a fully electronic system aimed to improve efficiency in visa applications while eliminating intermediaries and hidden charges. The use of the eVDR (visa with a reference) became compulsory for foreign worker visa applications, including the purchase of insurance policies. Foreign workers were required to undergo health screenings in registered clinics equipped with the BioMedical system to eliminate incidents of fraud. After the implementation of the new system, the Immigration Department no longer accepted manual applications (Zolkepli 2015).

The online renewal of work permits represents another reform toward eliminating intermediaries. Since 2015 the renewal of the foreign worker permit, called the Temporary Employment Visit Pass (Malaysian acronym PLKS), has been done online through a government-appointed private company, MyEG Services Bhd (My Electronic Government). The reform aims to address the issues of misappropriation and negative perceptions about the Malaysian Immigration Department, thus improving the quality of service delivery and effectively reducing congestion in the immigration office by 50 percent. Under the manual process, there were many allegations about officials and private agents exploiting the system. Employers paid agents between MYR300 and MYR500 for each worker, and these costs would subsequently be passed on to the workers. Thus, the new system prevents agents (both authorized and unauthorized) from extorting illegal commissions from employers and has diminished the allegations about immigration officers’ collusion with these agents (Malaysia 2015a, 4–5).

Moving forward, the government also introduced three online application systems for foreign workers on April 1, 2017 to ensure that both employers and foreign workers would no longer be cheated by third-party agents. The three online recruitment systems are the Integrated Foreign Workers Management System (ePPAx), SPPA, and MYXpats for expatriates. Each company needs to digitalize its information in the system, replacing the paperwork. The advantages include reduced costs, more convenience, and greater confidentiality. The whole recruitment process is now digitalized, from application to permit renewal and repatriation (Moh 2017). The SPPA system is for Bangladeshi workers only, while ePPAx is used for foreign workers from all other source countries. The ruling is mandatory for foreign workers in formal sectors (manufacturing, construction, services, plantations, and agriculture) but not in the informal sector (employing foreign maids). Digitalization eliminates the involvement of third parties, to prevent agents from taking advantage of poor migrant workers and overcharging employers. It curtails corrupt practices among officers and curbs the risks of migrant trafficking and abuse (Shahar 2017).

Direct hiring without agents was soon expanded to the recruitment of foreign maids. The government introduced an optional online system beginning January 1, 2018, which allowed employers to directly apply for foreign maid permits from the nine source countries: Indonesia, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, Thailand, India, Laos, Nepal, Vietnam, and Cambodia. Direct recruitment of domestic workers tackled the issue of human trafficking and reduced costs more than 50 percent, from MYR12,000 to MYR3,600. Alternatively, employers could still utilize agents, because the ruling was not compulsory (Sun Daily, November 1, 2017). Effective January 1, 2018, the new Maid Online System (SMO) was launched. It received a positive response. Within one week of its launch, 3,141 employers registered and 36 employers received their maids (Surach 2018).

The move toward digitalization and centralization would eventually result in the termination of recruitment agencies’ services. This was a disturbing development for the hiring agencies and the employers of foreign workers, who reacted negatively to the implementation of the FWCMS and the MyEG system. There were concerns about added costs, national security, and the monopoly of the FWCMS, developed by the private firm Bestinet Sdn Bhd, which had been contracted by the government. The use of the FWCMS was mandatory as all health check-up centers in the source countries were compelled to use the Bestinet system. Employment agencies in the source countries criticized both the BioMedical system and the eVDR for the increase in fees, from MYR15 to MYR250. Foreign governments, such as those of Nepal and Indonesia, threatened to stop sending their workers to Malaysia. The monopolization of the eVDR and the biometric system by Bestinet would expose foreign workers to human trafficking risks if the cost could not be monitored. As a result, the FWCMS, which came into effect on January 15, 2015, was suspended by the Immigration Department after two weeks of its operation, before resuming in June 2015 (Zachariah 2015).

The mandatory use of both the FWCMS and the MyEG online system was criticized not only by lawmakers but also by local Chinese businesses. The Associated Chinese Chambers of Commerce and Industry of Malaysia (ACCCIM), representing over 28,000 Malaysian Chinese businesses, called on the government not to make it mandatory to use the FWCMS and the MyEG online system to renew the PLKS, claiming that both private firms were exploiting the services for profit. Additionally, both systems were still under the “proof of concept” and at the test-run stage. According to the ACCCIM, “The government can outsource the system to external specialised entities, but they should not outsource the power of approval to the respective third parties” (Borneo Post, January 29, 2015).

In the state of Sabah, the Association of Foreign Worker Hiring Agencies (PAPPAS) has supported the state government by managing the local recruitment industry for more than 20 years. Any termination of service would negatively affect the businesses of PAPPAS member agencies. PAPPAS urged the government to consider the difficulties that would be faced by its recruitment agencies (Gordon 2016). The implementation of the online system in Sabah would put 53 local agencies out of business, and their employers would also risk losing their livelihood. PAPPAS has 53 members that are legal recruitment agencies under the Private Employment Agencies Act 1981. For the past two decades, its member agencies have delivered effective services to all industry stakeholders: employers, employees, foreign companies that supply workers, the state government, and the source countries under the established system. The association objected to any monopolization of the business and urged the government to ensure that “they do not lose their bread and butter in favour of other companies that provide an online service” (Daily Express, September 15, 2016).

The government’s move to outsource the online permit renewal service to MyEG was perceived as an attempt to exercise some sort of monopoly, depriving other agents of their livelihood while allowing only one company to profit. Prior to 2015, some agencies helped employers manage all permits. The government’s sudden decision to outsource the online service resulted in a loss of business for all these agencies. The government was asked why it had delegated a revenue-generating service worth MYR73.6 million a year to a private company instead of having the Immigration Department deliver it: “Why do we outsource immigration service to one company and make it a monopoly? Why was this monopoly given to MyEG?” (Malaysia 2015b, 35–36). MyEG secured a five-year concession agreement (May 23, 2015–May 22, 2020) worth MYR553.85 million to provide online renewal of the PLKS for foreign workers (Ooi 2017). The government reiterated that outsourcing the MYR73.6-million-per-year service delivery to a company, rather than delegating it to immigration officials, would address the issues of misappropriation and negative perception about the Immigration Department (Malaysia 2015b, 36).

Changing the Gatekeeper Orientation

The gatekeeper orientation has been improved in two ways—involving the employers and the labor market. Employers are delegated more responsibilities under the newly introduced strict liability principle as a means to improve gatekeeping. Direct employment by employers through the online system can provide a better picture of the labor market demand in comparison to the manual process conducted by agents, which is inadequate for responding to labor market demand. It is noteworthy that employers are empowered under the state’s legalization program. Under the Rehiring Program, foreign workers must be present with their employers at the immigration office. Between February 15, 2016 and May 28, 2018, 83,919 employers participated in legalizing 744,942 undocumented immigrants through the three government-appointed vendors, 307,557 of 744,942 applicants qualified for legalization, 329,151 applications were in process pending biometric information, and 108,234 were rejected. The unqualified workers were processed for the repatriation program by employers and vendors (Star Online, June 2, 2018).

The strict liability principle is applied when foreign workers are brought in under the online recruitment process. Based on this principle, employers themselves apply for their required workers. Digitalization may contribute to foreign workers’ welfare; employers are fully responsible for each worker’s permit application and renewal online, making them accountable for irregularities in the recruitment process (Malaysia 2016a, 67). This system may be interpreted as a means to improve gatekeeping, where the liability is held by employers. Discussions are ongoing to implement the strict liability principle to ensure that employers will be more responsible for the welfare of their foreign workers, from the latter’s arrival until the end of their contracts. The employers’ responsibilities include providing accommodations, minimum wages, health insurance, and medical benefits and complying with international labor standards (Sun Daily, June 26, 2016).

The government decided to change the gatekeeper from the MOHA to the MOHR, signaling a reorientation of where the “gate” lies. In October 2018, Home Minister Muhyiddin Yassin announced that foreign worker recruitment would be transferred to the MOHR’s Private Employment Agency in 2019. The decision was made during the meeting of the newly established Foreign Worker Management Special Committee under the Pakatan Harapan government. According to the committee’s deliberation, the outsourcing system would be discontinued gradually, and the services of one hundred outsourcing companies would be terminated (Tee 2018). According to the 11th Malaysia Plan, policy making for foreign worker management would be placed under a single administration, the MOHR. To ensure that employers would be fully responsible for the recruitment and welfare of their employees, the strict liability concept was embedded in the 11th Malaysia Plan (Malaysia, Economic Planning Unit 2015, ch. 5).

Replacing Agents with Government-Appointed Authorized Vendors

The renewal of foreign worker permits was undertaken by MyEG, which could not hire third-party agents. Despite the efforts to eliminate intermediaries, some cases of fraudulent agents were still reported. Some individuals claiming to be appointed agents cheated employers and immigrants, asking for deposits to legalize undocumented foreign workers when the deadline for the amnesty program approached (Civil Society Organisations 2018). Some syndicates were involved in PLKS forgery, charging employers MYR1,500 and acting as intermediaries submitting applications to the Immigration Department. For example, a Bangladeshi-led syndicate forged some of the PLKS documents, sending a few applications to the Immigration Department for approval. Employers were thus advised to submit their online PLKS applications directly, with lower charges (Sun Daily, October 17, 2017).

Similarly, the involvement of agents was also excluded from the state’s legalization program, called the Rehiring Program, to discourage profiteering. Instead of agents, the government appointed three third-party vendors to manage the program from February 15, 2016 to June 30, 2018. Iman Resources Sdn Bhd dealt with the legalization of Indonesian nationals, Bukti Megah Sdn Bhd handled Myanmar nationals, and MyEG was in charge of other nationalities. After the program ended, the Immigration Department took over all services related to foreign workers’ employment, and the services of the three vendors were terminated (Ragananthini 2018). Despite the widely known fact that no agents were involved in the Rehiring Program, the news media reported numerous cases of fake agents and syndicates operating the program. The syndicates promised valid work permits and employment to undocumented migrants for a fee of MYR8,000, even after the program deadline. For example, a syndicate operated by locals earned MYR2.2 million by cheating more than 270 foreign workers (Star Online, August 15, 2018).

A more worrying trend was some undocumented immigrants’ involvement in operating these counterfeit syndicates, deceiving their compatriots with promises of securing employment and work permit extensions. The existence of both local- and foreign-operated syndicates managing the legalization program without permits threatened national security. A Bangladeshi-owned company was reported to have been operating the Rehiring Program illegally for more than a year, disguised as a mini-market that was converted into an office (Sun Daily, July 6, 2018). According to the law, only authorized vendors and several of the company’s subsidiaries were allowed to manage the Rehiring Program. Raids conducted by the Immigration Department’s Intelligence, Special Operations, and Analysis Division found that the Rehiring Program syndicates’ activities were expanding. Some authorized company subsidiaries infringed immigration laws and abused the approval granted. False document agreements were made with factories, foreign workers’ applications were processed with dubious documents, and migrant workers became partners in some of the companies. In a raid on a rehiring syndicate in Selangor, 98 Bangladeshi and Indonesian passports and MYR250,000 in cash were seized (Teoh 2018).

Fake rehiring agents were responsible for otherwise eligible migrant workers’ missed opportunity to extend their employment in Malaysia. There was a news report about 270 Bangladeshi workers being swindled in the amount of MYR1.8 million by a fake rehiring agent. The Bangladeshi victims submitted their passports and paid MYR8,000 each to the agent to secure valid work permits before the Rehiring Program deadline. However, the agent failed to get back to them before the deadline passed, believing that these undocumented migrants would not report the case. Since they failed to be legalized under the program, these migrants were forced to return to their country (Zolkepli 2018). Labor agents and brokers thrived in the underground labor market, while employers got away with unpaid salaries. According to MP Charles Santiago, “We are yet to demonstrate a commitment to go after labour agents and brokers, who profit at the expense of these poor migrant workers” (News Hub 2018). Employer associations blamed third-party agents and government-appointed outsourcing companies. The Malaysian Trade Union Congress argued that irregularities caused by bringing in an excessive supply of foreign workers could be traced to these agencies. “They serve[d] as one-off suppliers” without ensuring the validity of these workers’ permits. For the Federation of Malaysian Manufacturers, law enforcement left unscrupulous agents free to escape punishment (Teh and Shah 2018).

Law Enforcement and Regulating the Activities of Agents

The Immigration Department announced the launch of Ops Mega 3.0 to flush out irregular immigrants nationwide beginning on July 1, 2018, after the deadline of the Rehiring Program. The crackdown aimed to enforce the law on immigrants and their employers. Stubborn employers who protected, hired, and allowed irregular migrant workers to stay in their premises would be punished with a maximum fine of MYR50,000, imprisonment not exceeding a five-year term, and caning up to six strokes (Star Online, June 2, 2018). The Immigration Department’s director general justified the action against employers, reiterating that there would be no crackdown on foreign workers if employers hired them legally. There were legal channels for hiring workers, and employers must follow the requirements of the MOHA (Kumar 2018). Human Resources Minister M. Kulasegaran echoed the Immigration Department’s commitment to strictly enforce the law against errant employers, in line with the MOHR priorities of zero corruption and “meticulous enforcement.” In cooperation with the MOHA, the MOHR sought out stubborn employers (Sun Daily, June 4, 2018).

The failure to deal with the influx of illegal foreign workers discredited the performance of the previous government. The Barisan Nasional government promised to rid the country of illegal migrants through its declared “zero illegal immigrant” policy. However, the country was inundated by immigrants. Their overwhelming presence in the city of Kuala Lumpur has created the impression that local residents have become minorities in their own country. The Pakatan Harapan government is determined to “clean up” the country of illegal immigrants. In conjunction with Malaysia’s National Day on August 31, the Immigration Department pledged to “free” the country of undocumented immigrants. Enforcement operations were intensified after all the opportunities for registration and legalization of foreign workers ended on August 30, 2018 (Muhamading and Teh 2018).

The new nationwide enforcement operations (Ops Mega 3.0) were criticized by parliamentarians for targeting helpless victims and employers but not the perpetrators. The Pakatan Harapan coalition government was urged to target traffickers instead of cracking down on four million undocumented workers. The group of traffickers was identified as the root cause of the oversupply of foreign workers, who were victims of human trafficking syndicates and fraudulent agents. According to a Democratic Action Party lawmaker, three prioritized areas would bring greater benefits at lower costs: enforcing the law on human smugglers, protecting the victims, and preventing illegal entry (Malaysiakini 2018). Similarly, civil society organizations and migrant groups protested about Ops Mega 3.0, calling for comprehensive and holistic rights-based solutions. According to these groups, the operations were criminalizing foreign workers for offenses that were not their fault. Upon landing in Malaysia, many victims found their contracts, employment sites, and terms and conditions different from what they had been promised, resulting in violations of immigration laws, which were circumstances beyond their control. Among other measures, the migrant groups recommended the following: (1) suspending raids and operations, (2) making available Ops Mega 3.0’s standard operating procedure for conducting raids and detaining undocumented migrant workers, (3) decriminalizing the “undocumented” status of workers, (4) facilitating G2G hiring mechanisms, (5) stopping the blacklisting of migrant workers who used the 3+1 amnesty program, and (6) ensuring that all migrants would have access to justice and the right to redress (Civil Society Organisations 2018).

The penalty regime against errant employers was stepped up, following the end of the Rehiring Program on June 30, 2018. Employers who failed to settle their fines after this date were blacklisted, banned from leaving the country, and barred from any dealings with the Immigration Department until they had settled their fines, a ruling that outraged them. From the point of view of the Immigration Department, the fines should have been paid when these employers legalized the workers. Employers were given an additional time frame until August 30, 2018 to settle outstanding penalties. The move provoked negative responses from the Malaysian Employers Federation, which lamented that these employers had already registered their undocumented workers and that the Immigration Department should not focus on penalizing employers. The Asean Traders Association stated that it was “excessive to impose compounds on business,” which was already having difficulty surviving. Both organizations opposed the monetary fines imposed for hiring undocumented workers (Kumar and Chung 2018). The construction and service sectors were facing shortages of site workers, who went into hiding as the crackdown continued, affecting Malaysia’s economy. The continuous and consistent crackdown frustrated employers, especially those operating small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). According to the SME Association of Malaysia, SMEs paid the agents under the Rehiring Program but did not have their undocumented workers legalized. They blamed these agents, saying, “Agents just want to make the money” (Goh, Melissa 2017).

Criminalizing workers and later employers did not resolve irregularities created by the industry system itself. Migrant workers were turned into “profitable commodities” by recruitment agencies and failed by their exploitative employers. Enforcement did not solve the underlying problem; rather, it further alienated the migrants. An overhaul of the migrant labor management system would be much needed compared with the repeated cycles of legalization, amnesty, and crackdown (Sun Daily, June 6, 2018). Despite protests from migrant groups, it was doubtful that the Immigration Department would scale down its raids. In 2017 the department set a new target of 1,300 enforcement operations as its monthly key performance indicator (KPI) compared with its initial KPI of 850 operations (Goh, Pei Pei 2017).

Private Employment Agencies (Amendment) Act of 2017

In a move to ensure strict enforcement against illegal recruitment agencies, the Private Employment Agencies Act was revised again in 2017 after the 2005 amendment. It empowers the government to regulate recruitment activities conducted by PEAs and to protect local workers in Malaysia (Yong 2018). The Private Employment Agencies Act of 1981 governed the activities of PEAs and safeguarded the rights of job seekers. As of 2017, 1,003 PEAs were registered in peninsular Malaysia, 55 in Sarawak, and 117 in Sabah. The Private Employment Agencies (Amendment) Act of 2017 requires each PEA to have a valid license and prevents recruitment activities without a valid license. It involves amendments and replacements of 29 existing provisions, the creation of 24 new ones, and the abolition of 11 provisions. It aims to modernize PEA-related legislation to comply with current requirements, clarify the application of recruitment-related legislation covering foreign workers, and empower enforcement activities (Malaysia 2017b, 84–85).

Among the issues discussed during the second and third readings of the bill, a better protection mechanism against illegal recruitment agencies was brought up. Any party engaged in recruitment activities without a license was to be penalized with a fine not exceeding MYR200,000 or imprisonment not exceeding three years or both (Section 7). The imposition of this severe punishment prevents recruitment without a valid license, which can have a huge impact on victims, who are often associated with trafficking and forced labor (Malaysia 2017b, 87). A new 13D clause of this bill requires a licensed PEA company to provide an identification document to its employees responsible for recruitment activities; failure to do so will subject the party involved to a fine not exceeding MYR10,000. This provision was included because the enforcement revealed that some parties conducted recruitment activities illegally (Malaysia 2017b, 89).

Several new interpretations are stated in Section 3 of the bill. First, a “private employment agency means a body corporate incorporated under the Companies Act 2016 (Act 777) and is granted a licence under this Act to carry out recruiting activities” (Section 3a). This amendment of the interpretation requires any party applying for a PEA license to be a company registered under the Companies Act 2016. Second, an “employer means any person who engages a private employment agency to recruit an employee for himself” (Section 3g). This interpretation prevents outsourced labor in which the employer supplies the person recruited via the PEA to another employer. Third, “recruiting means activities which have been carried on by any person, including advertising activities, as intermediaries between an employer and a job seeker” (Section 3i). To facilitate monitoring and enforcement, the phrase “any person” includes private persons or organizations undertaking recruitment activities without PEA licenses (Malaysia 2017b, 86). To prevent PEAs from imposing high fees on job seekers and non-citizen employees, the bill stipulates that such agencies are only allowed to impose a registration fee and a placement fee as specified in the First Schedule (Sections 14a and 14b). Such agencies are required to deposit a money guarantee as specified, which will be utilized if the agency fails to fulfill its responsibilities to job seekers, non-citizen employees, and employers (Sections 14c and 14d).

Renegotiation with Labor-Supplying Countries in ASEAN

The de-commercialization approach has broader implications for anti-trafficking efforts and migrants’ protection. Ensuring a sound recruitment process is closely related to migrants’ protection and regional efforts to tackle human trafficking. The Malaysian migrant rights group Tenaganita criticized the use of private agencies because the latter were driven by profit. Profit-oriented outsourcing systems not only led to high recruitment fees but also posed the risk of corruption. The business-to-business recruitment model fostered human trafficking. According to Tenaganita’s Executive Director Glorene Das, “the logical solution would be an overhaul of the system to remove the focus on direct profiteering and increase regulation” (Soo 2018). The gradual termination of the outsourcing system and the shift to the G2G system are significant steps in combating human trafficking and foreign workers’ exploitation. Malaysia’s restructuring of its foreign labor recruitment addresses a critical problem in the migration industry by eliminating intermediaries, thus putting an end to debt bondage. Debt bondage is a form of modern-day slavery in which workers have to work excessive hours to pay back the high recruitment fees (Beh 2018).