Contents>> Vol. 6, No. 3

The Is and the Ought of Knowing: Ontological Observations on Shadow Education Research in Cambodia

Will Brehm*

* Waseda Institute for Advanced Study, Waseda University, 1-6-1 Nishi Waseda, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 169-8050, Japan

e-mail: willbrehm[at]aoni.waseda.jp

DOI: 10.20495/seas.6.3_485

Keywords: shadow education, private tutoring, Cambodia, critical realism, methodology

Introduction

There is a long-standing Western philosophical problem in using descriptive statements (what is) to make prescriptive claims (what ought to be). But do claims of “what ought to be” limit “what is”? This can happen when erroneous assumptions proliferate. Since all research begins with assumptions, it is vital not to be mistaken.

Some of the most common assumptions in research relate to terminology and definitions. The terms and definitions used by researchers help to manage concepts that are difficult to comprehend. To manage a concept so that it can be studied, the terms and definitions employed in research studies necessarily exclude alternative meanings. As such, assigning terms and settling on one definition over another for a given concept is never a neutral process. This struggle over meaning is a central feature of academic debate.

Research on “shadow education” is a case in point.1) Shadow education can be broadly defined as a collection of educational services that are fee based but not public, mainstream schooling.2) The formation and organization of the phenomenon differ across the globe. Within Southeast Asia, the differences are pronounced. At one extreme are Cambodia, Brunei Darussalam, and Laos, where tutoring is commonly initiated by schoolteachers to top up (sometimes substantially) low salaries. In these cases, it is difficult to know when mainstream schooling ends and private tutoring begins. At the other extreme are Singapore, Thailand, and the Philippines, where tutoring has developed into a legitimate and recognized business sector. Students in these countries typically take extra lessons in centers that are organized as for-profit companies, outside the control of education ministries but connected to school curricula and examinations. In Singapore, for instance, 8 out of 10 primary school children attend tutoring (Straits Times-Nexus Link Tuition Survey 2015), and the amount households pay on tutoring increased from S$650 in 2004 to S$1.1 billion in 2014 (Tan 2014).

Across the globe people have their own, evolving terms to describe the activities researchers commonly refer to as shadow education. In Japan the dominant form is termed juku, in England it is called tuition, and in Cambodia it is labeled ɾiən kuə.3) Yet each of these terms misses the complexity of the phenomenon as it is currently understood. There are juku for examination preparation and juku for remedial study (Roesgaard 2006; Watanabe 2013). There are tuition classes in cyberspace and in everyday life (Ventura and Jang 2010). Both public and private school teachers can teach ɾiən kuə classes. As educational spaces evolve and morph into new realities, and as researchers’ understandings deepen, researchers try to refine and add complexity to their terms and definitions.

Yet decisions over the definition of a phenomenon like shadow education often have unintended consequences. One possible consequence of choosing one meaning over another is the assumption that it accurately captures the phenomenon’s existence, its ontology. Another consequence is that operationalized terms and definitions can be normalized and therefore legitimized by future research studies, thus missing possible changes to the phenomenon itself. In these situations, what was excluded from or simply not captured by the definition and term lead to significant gaps in understanding.

This article focuses on the limitations of terms and definitions regarding shadow education research in Cambodia. Although shadow education in Cambodia is typically defined as private tutoring taught by mainstream schoolteachers to their own students (captured by the term ɾiən kuə), my experience suggests that many types of ɾiən kuə comprising the activities of shadow education have been missed by most studies on the subject, including my own.

The missing terms and definitions in the research literature raise a methodological question: Do terms and definitions used in research studies capture, intentionally or not, only part of the multifaceted phenomenon? By tracing the terms used and the definitions of shadow education in various research studies, I argue that the assumptions made over terms and definitions (i.e., what ought to be the case) limited researchers’ understanding of shadow education in its ontological evolution and complexity (i.e., what is the case). This has profound consequences for how the phenomenon may be theorized. I advocate a critical realist approach to the study of shadow education not only in Cambodia but across Southeast Asia to acknowledge the existence of its reality, whether or not researchers can adequately see, name, or define it.

Changing Terms, Static Definitions

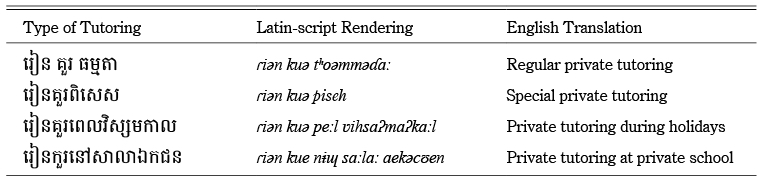

In Cambodia people use the term ɾiən kuə to describe what researchers would call shadow education. Like the term juku in Japan, however, ɾiən kuə can embrace multiple types, which are likely evolving and thus should not be taken as static (see Table 1).

Table 1 Types of Tutoring

The most common type of ɾiən kuə is “regular private tutoring,” which is fee-based tutoring in classes taught by mainstream schoolteachers. It is considered “regular” (tʰoəmməɗaː) because it focuses on the mainstream curriculum and resembles mainstream classes (i.e., class sizes and layouts are like those in mainstream schooling). A less common form of ɾiən kuə is “special private tutoring,” which covers individual or small group classes taught by a tutor who may or may not be a student’s mainstream schoolteacher. These classes cost much more than regular private tutoring classes. Some students have the option of attending and paying for “private tutoring during holidays.” These are classes conducted in school or at a teacher’s home, and are held by a student’s current or future teacher when mainstream schooling is not in session. The last type of ɾiən kuə, which appears to be a growing phenomenon especially in city centers, is “private tutoring at private school.” This type of ɾiən kuə covers tutoring classes of various sorts, held by non-mainstream schoolteachers outside public school buildings, and for some cost. The word “school” in this type of tutoring takes on a broad meaning, from registered tutoring centers as businesses to makeshift classrooms inside university students’ homes or apartments. Each type of ɾiən kuə has different causal origins, and future evolutions will likely make this artificial categorization obsolete.4) Nevertheless, this brief orientation of contemporary ɾiən kuə will be useful to the reader going forward.

The transliterated terms I provide above have rarely been used in the English-language research literature. Instead, terms such as private tuition, private coaching, or private tutoring have been used. Quite apart from the loss of meaning when one of these terms is translated into Khmer, it is the evolution of English terminology that interests me here. In this section I trace both the terminology and the definition of the phenomenon referred to broadly as ɾiən kuə. I show that the English terminology has changed within and across research studies reported in the English language, while the definition has stayed roughly the same.

One of the first mentions in Cambodia of “private tuition” was in a 1994 Education Sector Review (Cambodia 1994). The Review’s executive summary stated, “recent surveys suggest that parents pay around R120,000 per annum per primary student for uniforms, private tuition and books” (ibid., Vol. 1, 14; emphasis added).5) This indicates that the researchers who conducted the cited surveys included “private tuition” as a category of possible household expenses.

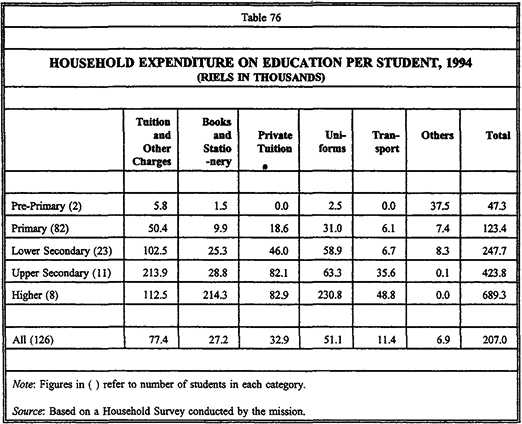

Closer inspection of the data within the Review reveals that different terms were used to describe the phenomenon in the two surveys to which the Review referred, namely, “private tuition,” “private coaching,” and “private tutoring.” However, both surveys defined the concept in similar ways. In one table, family costs of education per pupil were reported in the main urban centers in six provinces for primary schools and three provinces for secondary schools. The costs were categorized into textbooks and materials, uniforms, contributions to school, transport, and private coaching (ibid., Vol. 2B, Table 75; see Fig. 1). In another table, household expenditures per student were reported from a sample of 126 students and were broken down into different categories: tuition and other charges, books and stationery, private tuition, uniforms, transport, and others (ibid., Vol. 2B, Table 76; see Fig. 2).

Fig. 1 Table 75 of 1994 Education Sector Review, Vol. 2B

Fig. 2 Table 76 of 1994 Education Sector Review, Vol. 2B

Although data reported in the two tables came from different sources, which is likely why there was a slight difference in terminology,6) the terms refer to the same phenomenon. A definition of the interchangeable terms can be ascertained in the main body of the Review (ibid., Vol. 2A, 109). In this description, “private tutoring is not, as one might assume, an opportunity for individual students to get special help on material they might not have understood in class. Instead, it constitutes an extension of the regular curriculum offered by the same teacher in the same large group setting—this time with a user fee attached.” Moreover, the report labeled private tutoring as “part [of] the shadow private system” of education (ibid.). This description was recycled almost verbatim by subsequent Reviews (e.g., Cambodia 1996) as well as in later studies by Mark Bray (e.g., Bray 1996a; 1999), the scholar who has propelled research on shadow education worldwide and who was my PhD adviser. As I will show below, this description has remained the central definition of the phenomenon in the Cambodian context.7)

Reproducing a case study from the Review, Bray (1996a, 16) used the term “private tutoring” to discuss the phenomenon in Cambodia.8) He (1999) also used the terms “supplementary tutoring” (57), “private tutoring” (22), and “private supplementary tutoring” (90) to describe the “shadowy system considered beyond the control and responsibility of government” (90) in Cambodia. Bray (ibid.) pointed out that in the Cambodian context, “much of the tutoring is in the students’ own schools and is given by their own teachers” (21).9) Although Bray (ibid., 57) acknowledged some “pupils made private arrangements for additional tutoring outside the schools,” tutoring was categorized as an in-school expense. The English terms used by Bray and the authors of the Review in Cambodia include “private tuition,” “private tutoring,” “private coaching,” and “private supplementary tutoring.”

Although different combinations of terminology were used from 1994 to 1999, the description of the phenomenon remained relatively constant. Bray (1999) reproduced the description of “supplementary tutoring” in Cambodia in a highlighted box titled “private enterprise in a public system” (22). In this box, which came from the 1996 Education Sector Review (Cambodia 1996, 107), “private tutoring” was described as “an extension of the regular curriculum offered by the same teacher in the same large group setting—this time with a user fee attached.” This is identical language to the 1994 Review cited by Bray (1996a, 16): private tutoring “constitutes an extension of the regular curriculum offered by the same teacher in the same large group setting.” Despite the variable terminology in all the reports mentioned thus far, the descriptions of the actual concept remained nearly identical. The terminology and description used in the Review (Cambodia 1994) were not only reproduced by Bray’s (1996a; 1999) two studies but also were repeated and reused by various authors over the next 15 years.

Before looking at some of these studies, it is important to situate the evolution of terms in their historical context. The historical beginnings of the various terms can be traced, in part, to a separate study by Bray (1996b) for UNESCO’s International Commission on Education for the Twenty-first Century in which he discussed “a general shift in the centre of gravity towards greater private ownership, financing and control of schools” (i).10) Although this report was not about Cambodia per se, it did show Bray’s own process of coming to understand the concept of shadow education and the various terms (and metaphors) that could be used to label it. It also suggests that the concept of shadow education was implicated in the school privatization processes that became popularized within various development organizations and international financial institutions during the 1990s.11)

Bray continued his Cambodian research with another study a few years later. Bray and Bunly (2005) built on Bray’s (1999) study to focus on household costs at the primary and lower secondary levels. The latter grades were unexplored in the earlier study. In the 2005 iteration, supplementary tutoring was described as in earlier studies, and the terminology was again multiple. Bray and Bunly (2005) used “supplementary tutoring” (11), “private tutoring” (75), and the “shadow system” which operates “alongside the mainstream” (40). The description of these various terms remained nearly identical to those in 1994, 1996, and 1999: “in Cambodia, much of the tutoring is in the students’ own schools and is given by their own teachers” (ibid., 11).

The relative stability in the description of “private tuition,” “private tutoring,” “private coaching,” and “private supplementary tutoring” from the 1994 Review to Bray and Bunly’s (2005) study, which may be an outcome of the relatively short time frame and similar authors across the studies, was normalized and legitimized by later studies. In its 2007 report on informal fees to education, the NGO Education Partnership (NEP) wrote of “private tutoring” with the occasional use of “extra tutoring” (NEP 2007, 17, 26). Similar but not identical to Bray and Bunly’s (2005) formulation, the NEP classified tutoring into two types: teachers who “conduct private classes” do so either (1) “on the school premises” and therefore for their own students; or (2) “in private classrooms set up in the community” and therefore open to all students (16). The report went on to state that private tutoring was “often a continuation of the public curriculum rather than supplementary” (ibid., 16), thus disputing—but not elaborating on—one of the key terms used in previous studies. There may have been small revisions and challenges to the terminology used to describe the phenomenon, but the description of “private tutoring” in the NEP report was similar—if not identical—to the 1994 Education Sector Review.

Walter Dawson (2009) was the first to problematize explicitly the terminology used in shadow education research in Cambodia. The data collected by Dawson in 2008 set out to “re-examine the findings” of earlier studies on shadow education in Cambodia (ibid., 55). He preferred to use the terms “private tutoring” and “shadow education,” and critiqued some of the other terms used in earlier studies. When citing data from a government report from 2005, Dawson noted (ibid., 57) its problematic use of “remedial tutoring” as a category of unofficial fees. He went on to explain how tutoring in Cambodia is neither supplementary (because much of it completes the national curriculum), echoing the NEP (2007) study, nor remedial (because high-achieving students attend just as often as low-achieving students).

Despite his critique of the different terms used to describe shadow education in Cambodia, Dawson nevertheless employed the same description as the 1994 Education Sector Review: “This form of shadow education wherein state teachers conduct private tutoring for their own students is well documented by Bray and not unusual to find in many developing countries . . .” (Dawson 2009, 51).

The description used by Dawson (2009) included the phrase “This form of” without exploring alternative forms. In a later article comparing shadow education in Japan, Korea, and Cambodia, Dawson (2010) again suggested that there were multiple forms of tutoring. In the section on Cambodia (ibid., 20), he qualified the term “private tutoring” with the phrase “this brand of,” like the phrase “much of” used by Bray (1999, 21) and Bray and Bunly (2005, 40). Since Dawson did not explain other “brands of” tutoring within the Cambodian context, I read this phrase as drawing a comparison to the tutoring practices in the other two countries. What he did not do, in other words, was suggest there were different “brands of private tutoring” within Cambodia. This is particularly surprising given that Dawson (2010) discussed the many types of juku in the section on Japan (16).

A 2011 study by William Brehm, Iveta Silova, and Mono Tuot (2012; also, Brehm and Silova 2014) continued the trend of challenging terminology while describing the phenomenon as teachers who tutor their own students. Brehm and Silova (2014) described private tutoring thus: “Before or after attending the required four or five hours of public school each day, many students receive, and pay for, extra instruction [by their own teacher]” (95). Brehm et al. (2012) offered the term “hybrid education” in their discussion on “shadow education” and “supplementary tutoring” (14–16). This concept was defined simply as public, mainstream education plus “complementary tutoring,” which was defined as the type of tutoring where teachers tutor their own students. Although they preferred the term “complementary tutoring” to “supplementary tutoring” because, echoing Dawson’s work, the former includes “lessons that are essential [and not extra] to the national curriculum” (ibid., 15), they continued to use the common description of tutoring since 1994 that focused on teachers who “conduct private tutoring lessons with their own students after school hours either in school buildings or in their home” (ibid., 16). Moreover, the authors argued that the hybrid system “casts a shadow of its own” (ibid., 15), meaning other forms of tutoring (e.g., “remedial and/or enrichment education opportunities” [ibid.]) existed because of this hybrid system. They highlighted the different types of tutoring in a table (ibid., 16). The private tutoring commonly referred to in past studies was labeled “extra study” (with an incorrect Latin-script rendering of the Khmer script as rien kuo). They then offered other types of tutoring (and their English translations), such as “extra study during holidays,” “extra special study” (i.e., individualized tutoring), “private (tutoring) school,” and “English/French extra study.” Each was a different type of tutoring conceptualized into two broad categories: “hybrid education” and “shadow education.”

Despite the expansion in their description of hybrid education and its shadow, Brehm et al. (2012) limited their study to “the differences and similarities between private tutoring (Rien Kuo) and government school classes” (17). In other words, they continued to study ɾiən kuə exactly as it had been historically described in the Cambodian context, neglecting its other forms despite recognizing their existence. Although they questioned the terminology used in shadow education research in Cambodia just as the NEP (2007) and Dawson (2009) had, Brehm and colleagues focused on one type of the phenomenon when collecting data.

This historical look at past research studies of ɾiən kuə in Cambodia shows two things. First, the terminology used to describe the phenomenon has changed greatly over the years. The terms private coaching, private tutoring, private tuition, supplementary tutoring, shadow education, extra study, etc., have all been used. Second, the description of these various terms has stayed relatively similar over time. That description is of tutoring given by schoolteachers to their own mainstream school students. Although the different authors recognize other forms of tutoring, rarely are they elaborated. Because of the similar descriptions of the phenomenon, all the research studies have used a similar core definition when collecting data, limiting what is ɾiən kuə to what it ought to be.

The Epistemic Fallacy and Concept Reification

Despite the changing terms, the similar descriptions of ɾiən kuə employed in the various research studies reduced descriptive claims of what is to prescriptive claims of what ought to be. The alternative realities were, in other words, reduced to the definitions employed in data collection methods. Methodologically, the unintentional recycling of the same definition across time resulted in the epistemic fallacy and concept reification.

The epistemic fallacy (Bhaskar 1975) is the confusion over how researchers know things with whether those things exist. The quintessential epistemic fallacy is perhaps best captured by Descartes’ (1637/1960) famous saying, “I think; therefore, I am.” In this example, it is implied that the ability of a subject to think about itself constitutes the self in reality. In effect, Descartes’ existence depends on his ability to think, thus “reduc[ing] reality to [his] knowledge of it” (Dean et al. 2005, 8). This is a fallacy because Descartes’ physical self exists whether or not he can actually think about it. In terms of Western philosophy, which underpinned all the studies discussed in the previous section, research that commits the epistemic fallacy assumes that epistemology comes before ontology. This is analogous to believing that ɾiən kuə exists only in the form that has been empirically captured by researchers.

The second problem of concept reification is the process of taking an abstract concept and turning it into a concrete reality. Shadow education is an abstract concept because the manifestations of its material reality—juku in Japan, tuition in England, or ɾiən kuə in Cambodia—are different depending on space, place, and time. Moreover, the material realities of juku, tuition, or ɾiən kuə are ever changing and therefore require constant revision to terms, descriptions, and definitions. Yet, through the research process where concepts are clearly defined and then operationalized in data collection instruments, the concept of shadow education necessarily goes from being an abstract concept to being a real thing that can be measured and described. The main problems with concept reification are that reified concepts may incorrectly or only partially capture material reality, and the reuse of the same reified concept in later studies decontextualizes the phenomenon from its material reality in specific spaces, places, and times.

To show these two problems in the research, it is necessary to look closely at the methods employed in the various studies on shadow education in Cambodia. What becomes clear across the studies is that the preferred method of data collection has been the survey, often supplemented with interviews and focus groups. It is within the surveys that the constant definition of ɾiən kuə is used and reused. It is precisely here where concept reification and the epistemic fallacy emerge.

Survey research is the quintessential data collection method that reifies concepts. Surveys must operationalize terms—that is, the process of measuring a concept that is not directly measurable—for data to be collected. In survey research, questions are asked to obtain empirical, measurable data that are said to define (often by proxy) an abstract concept. For example, measuring the amount of money students pay teachers for tutoring classes can operationalize the concept of private tutoring. Another possibility for operationalizing private tutoring is to measure the attendance of students in tutoring classes. Still a third way is to simply ask students, parents, or teachers whether private tutoring exists. In these cases, operationalizing essentially takes a concept and reifies it; it assumes one definition and therefore not another, and subsequently operationalizes the assumed definition by asking one set of questions and not another.

Operationalizing terms, however, is a necessary part of survey research. Bray and Bunly (2005, 28) rightly point this out: “Surveys need to set clear definitions and then to communicate those definitions to all relevant people.” A necessary consequence of setting clear definitions is the exclusion of other possible definitions. For example, defining private tutoring as fee-based classes taught by mainstream schoolteachers and then asking students about that may provide descriptive information on this topic, but it certainly will not provide descriptive information on the classes for which students pay (or not) that are taught by teachers other than their own mainstream schoolteachers. As such, to assume ɾiən kuə is captured completely by a set of survey questions reduces the reality of its existence to the knowledge produced by the survey, thus committing the epistemic fallacy.

The 1994 Education Sector Review reported data on private tutoring and private coaching from two different surveys (Cambodia 1994). The Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports and the development mission in charge of writing the Review conducted the two surveys. In effect, the surveys captured what the people constructing the surveys knew at one moment in time. From the two tables where private tuition/coaching are reported, it can be inferred that the surveys operationalized household expenditures into various categories. Private tuition/coaching was one such category. When the survey was carried out, respondents could respond to questions about money spent on private tuition/coaching. As such, private tutoring was operationalized by the amount of money respondents reportedly spent on private tuition/coaching.

The 1994 Review’s definition of private tutoring/coaching was used and reused in later studies. Although it is possible that surveys used in other studies asked questions about different types of tutoring, all the studies reported data on one (or possibly two in the case of Bray and Bunly 2005) type(s) of tutoring. In effect, the phenomenon was reduced—or flattened—to one understanding. The 1994 description of private tutoring, which captured one moment in time, became trans-historical as it was applied in and reported by subsequent studies. Consequently, what existed was what was seen, thus committing the epistemic fallacy. Alternative definitions of private tutoring were excluded even if other types of tutoring were alluded to.

Some of the studies used mixed methodologies to collect data. These studies can mainly be categorized as sequential explanatory design mixed methods (Creswell et al. 2003). In these types of studies, quantitative data are typically collected before qualitative data:

The rationale for this approach is that the quantitative data and their subsequent analysis provide a general understanding of the research problem. The qualitative data and their analysis refine and explain those statistical results by exploring participants’ views in more depth. (Ivankova et al. 2006, 5)

Sequential explanatory design mixed method empirical studies collect data through a survey and then explore that data in greater depth vis-à-vis public opinion interviews or focus groups. The latter provide qualitative details to the former descriptive statistics, and not vice versa.

Sequential explanatory mixed method studies have been the favored approach in shadow education research in Cambodia. Data in Bray’s (1999) study, conducted in two iterative phases in 1997 and 1998, “were collected through questionnaires and follow-up discussion with personnel from nine schools in each location,” which were based on a previous study in Bhutan (37). Discussion workshops were also organized with parents after questionnaires were administered. The notes from the workshop discussions, which were translated into English, were used “to supplement the data contained in the questionnaires” (ibid., 37). In phase two of the study, the questionnaire was revised based on the first phase of data collection and administered in the same manner. In addition, four case studies were conducted in the second phase. Bray and Bunly (2005) used a similar method to Bray (1999): school surveys followed by focus group discussions, followed by “in depth interviews with pupils for information validation” (Bray and Bunly 2005, 32). Similarly, the NEP’s (2007) study used a structured questionnaire followed by focus group discussions. The latter “provided more qualitative information about informal payments and explored in more depth public opinion and perception” (ibid., 9). In Dawson’s (2009) study, a sample of “primary school teachers . . . completed a written questionnaire after which they participated in a 60–90 minute focus group interview” (57). In each case, quantitative data collection preceded qualitative data collection. The one exception is the study by Brehm and colleagues (Brehm et al. 2012; Brehm and Silova 2014) where qualitative data (focus groups and observations) were conducted concurrently with quantitative data collection (grade tracking), while no survey was carried out. Nevertheless, problems remain in Brehm and colleagues’ work where the definition of private tutoring was assumed without question. In effect, the authors were only looking for one type of tutoring without realizing that other types might have existed.

In all the studies, alternative definitions to ɾiən kuə were excluded through the very research methods employed. The sequential explanatory design mixed methods used by most of the studies limited the definition of shadow education to one or two types, which were operationalized by questions in the surveys. When data were reported, the research studies privileged one definition of private tutoring to the exclusion of possible alternatives, even if the researchers themselves knew other types of tutoring existed. The abstract concept of private tutoring was therefore reified in the research literature to one specific type, with only slight variations over time.

Qualitative research in combination with survey research has the potential to overcome some of the inherent problems of survey research, namely, the impossibility of managing context (Burawoy 1998). That the definition of shadow education employed in data collection methods stayed relatively consistent over two decades of research suggests, however, that the qualitative side to the various studies never truly informed the surveys, at least in terms of the definition of the central concept under investigation. It is this methodological shortcoming that has reduced the many meanings of private tutoring to one definition, thus blinkering researchers from employing alternative definitions to capture other facets of the phenomenon within the Cambodian context. In this way, all the research studies committed the epistemic fallacy because they assumed reality was what could be seen and measured through surveys.

This is not to suggest that surveys should not be used in research. Surveys have real value due to their ability to describe certain concepts at one moment in time. However, without historical understandings of the sociocultural structures informing the construction of surveys, researchers are prone to commit the epistemic fallacy and reify concepts that may be fleeting, elusive, and evolving. An alternative starting point assumes reality is more than researchers can empirically observe. It is to this alternative that I now turn in the conclusion.

Conclusion

Whatever terms and definitions are settled upon dictate how researchers see and know the world, knowingly or not. Words and their meanings are the building blocks for theory, or what Western philosophers call epistemology. Moreover—and perhaps harder to grasp—the assumptions made over terms and definitions presuppose a general account of the world, or what Western philosophers call ontology. Terms and definitions not only help social scientists see the world by giving meaning but also help construct the world.

The history of shadow education studies in Cambodia highlights the dangers of assuming and operationalizing definitions. By limiting the definition of shadow education reported in various studies, researchers likely missed myriad experiences students had with tutoring. This was evident in Brehm et al.’s (2012) table of the different types of tutoring, most of which were different from the common definition of tutoring dating from the Review’s 1994 definition (Cambodia 1994). Although there were changes in terminology used to describe shadow education, such as the experiences in Japan and England, the surveys conducted across the studies in Cambodia did not allow for alternative realities to exist. As I attempted to show, it was not only survey research that limited the definitions but also more qualitative-oriented studies (e.g., Brehm and Silova 2014). By operationalizing one (or two) definition(s) of private tutoring into the various surveys, reality was flattened to only what was seen at one moment in time.

There is an alternative research paradigm that conceptualizes reality as stratified. Critical realism begins with the assumption that reality is more than what can be empirically seen. Reality is not limited to experiences but also includes sociocultural structures that do not have a material reality but nevertheless affect human agency through emergent properties. From this critical realist perspective, reality is stratified and not flat. As such, critical realism differentiates reality into three ontological levels.

The first level is the empirical. This is what researchers observe in daily life. It is precisely at this ontological level where the surveys employed in shadow education research in Cambodia exist. The various surveys could capture an empirical reality of a sample of individuals within a specific moment in time. For example, the surveys captured descriptive statistics such as the percentage of students attending one type of private tutoring, the typical cost of one hour of tutoring, the subjects commonly taught during private tutoring, and parental and teacher perspectives on why the classes were held. Critical realists argue this level of reality is true, but that there are likely other empirical realities from other people at the same moment (or different moments) in time that are also true but simply not captured by the research study. This is where the second ontological level exists.

The second level is the actual. This is the “sum total of events that can be said to have taken place” (Graeber 2001, 52). Although all experiences within the actual may not have been observed by a single actor, it is conceivable to accept the premise that experiences other than one’s own could in fact have occurred and could have been observed given different spatiotemporal configurations. For example, students may have attended private tutoring classes taught by teachers other than their own prior to 2005 when Bray and Bunly (2005) first reported data on this type of tutoring. Bray (1999) implied this in his use of the phrase “much of.” This implies that the ways in which researchers know are relative and socially produced: each person experiences different empirical realities, which then change how he or she knows something to be “true.” The level of the actual suggests that ontology exists whether researchers understand reality or not. As such, critical realists argue epistemology does not precede ontology but rather succeeds it.

The third ontological level is the real. This is the level of powers, mechanisms, and potentialities of what may or may not happen and which are irreducible to (patterns of) events. Whereas the levels of the empirical and actual are concerned with “events, states of affairs, experiences, impressions, and discourses,” the real is concerned with “underlying structures, power, and tendencies that exist, whether or not detected or known through experience and/or discourse” (Patomaki and Wight 2000, 223). It is in the level of the real where “a sense of reaching for deeper” explanations of the world appear through “the latent or invisible . . . forces that manifest themselves in everyday life” (Coole 2005, 124). It is at this level that a different conception of causation emerges. Causation is not a correlation between two or more empirical occurrences, but rather an understanding of the historical mechanisms and structures that make what exists possible. This requires more than empirical data that can describe the empirical and actual levels of reality. At the level of the real, social scientists “attempt to identify the relatively enduring structures, powers, and tendencies, and to understand their characteristic ways of acting” (Patomaki and Wight 2000, 223). These sociocultural structures are context specific and based on history.12)

To understand shadow education in Cambodia from a critical realist perspective therefore requires researchers to see it as a system with its own emergent properties and potentials that are irreducible to its constituent parts. Shadow education from this perspective is a social reality created through the interactions of people (students, teachers, parents, government officials, etc.) that embrace or transform (through reflexivity) certain vested interests, opportunity costs, and situational logics that are embedded in social structures and cultural systems (see Archer 2003).

A stratified ontology offers an alternative set of assumptions that can be usefully employed in shadow education research in Cambodia. First, a critical realist approach suggests survey research can inform understandings of empirical reality at certain moments in time, but its explanatory power of the phenomenon is limited. What causes shadow education, therefore, cannot be explained through survey research alone. In addition, placing surveys within the first ontological level of the empirical prevents trans-historicizing data and definitions. Researchers who take a critical realist approach should question definitions used and operationalized in previous empirical studies because the space, place, and time of definitions and terms must be recognized.

Second, qualitative research takes on a different purpose than studies that use sequential explanatory design mixed methods. Whereas the sequential explanatory design mixed methods approach places qualitative data collection after or in iteration with quantitative data to provide more depth to the statistical data, a critical realist approach would use qualitative data not only to inform the collection of empirical data through surveys but also to understand the ontological levels of the actual and the real. Regarding the latter, qualitative research keeps open the possibility of multiple empirical realities (i.e., the actual) without artificially limiting reality to one meaning as is necessary in survey research. Thus, during unstructured interviews, for example, an infinite number of definitions of shadow education could theoretically emerge from participants because they are not limited by a clearly communicated definition made prior to data collection by the researchers. This likely occurred in all of the research studies when the researchers first learned about the phenomenon, not through published articles but through interactions with their colleagues on the ground.

Third, a critical realist approach to shadow education research would incorporate theory differently than has previously been the case. Whereas theory has often been used to help make sense of empirical data collected, a critical realist approach uses theory to understand the ontological level of the real while acknowledging the social construction of theory itself. This is because understanding the real, which is where the causal mechanisms of shadow education are assumed to reside, requires an engagement with various types of theory. Since “widely different theories can interpret the same, unchanging world in radically differently ways,” it is necessary for critical realist researchers to recognize that “knowledge is not totally arbitrary and some claims about the nature of this reality may provide better accounts than others” (Patomaki and Wight 2000, 224). As such, research studies from a critical realist perspective begin with an engagement with the ontological level of the real and work “up” to the ontological level of the empirical. Understanding the real can help researchers operationalize definitions and terms in meaningful ways that can then capture empirical reality in specific places, spaces, and times.

Shadow education is a growing topic of scholarly research across Southeast Asia. Two decades of empirical research makes the case of Cambodia an important location where lessons can be found. The case of Cambodia shows that it is important to recognize the limits of meaning inherent in survey research studies that have dominated the literature on shadow education in Cambodia. Moreover, the research on Cambodia shows the importance of researchers broadening their approaches by conducting research with different sets of assumptions than previous research studies have made. One alternative advocated here is to see reality as stratified and not flat. With a stratified ontology, new meanings of reality open new possibilities for shadow education research not only in Cambodia but also across Southeast Asia and beyond. The reality of shadow education will subsequently overcome what it ought to be.

Accepted: September 12, 2017

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Mark Bray, Johannah Fahey, Roger Dale, and the three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and edits on earlier drafts of this article.

References

Archer, Margaret, S. 2003. Agency and the Internal Conversation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bhaskar, Roy. 1975. A Realist Theory of Science. New York: Routledge.

Bray, Mark. 1999. The Private Costs of Public Schooling: Household and Community Financing of Primary Education in Cambodia. Paris: UNESCO International Institute for Educational Planning in collaboration with UNICEF.

―. 1996a. Counting the Full Cost: Community and Parental Financing of Education in East Asia. Washington, DC: World Bank in collaboration with UNICEF.

―. 1996b. Privatisation of Secondary Education: Issues and Policy Implications. Paris: UNESCO.

―. 1995a. Community and Parental Contributions to Schooling in Cambodia. Bangkok: UNICEF East Asia and Pacific Regional Office.

―. 1995b. Community and Parental Contributions to Schooling in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic. Bangkok: UNICEF East Asia and Pacific Regional Office.

―. 1995c. The Costs and Financing of Primary Schooling in Bhutan. Thimphu: UNICEF and Government of Bhutan.

―. 1987. Is Free Education in the Third World Either Desirable or Possible? Journal of Education Policy 3(2): 119–129.

Bray, Mark; and Bunly, Seng. 2005. Balancing the Books: Household Financing of Basic Education in Cambodia. Hong Kong: Comparative Education Research Centre, University of Hong Kong; Washington, DC: World Bank.

Brehm, W. C. 2015. Enacting Educational Spaces: A Landscape Portrait of Privatization in Cambodia. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Hong Kong.

Brehm, William C.; and Silova, Iveta. 2014. Hidden Privatization of Public Education in Cambodia: Equity Implications of Private Tutoring. Journal of Educational Research Online 6(1): 94–116.

Brehm, William C.; Silova, Iveta; and Tuot, Mono. 2012. The Public-Private Education System in Cambodia: The Impact and Implications of Complementary Tutoring. London: Open Society Institute.

Burawoy, Michael. 1998. The Extended Case Method. Sociological Theory 16(1): 4–33.

Cambodia. 1996. Education Sector Review. Manila: Asian Development Bank; Brisbane: Queensland Education Consortium.

―. 1994. Education Sector Review, Vols. 1, 2A, 2B, and 3. Manila: Asian Development Bank; Brisbane: Queensland Education Consortium.

Connell, Raewyn. 2007. Southern Theory: The Global Dynamics of Knowledge in Social Science. Cambridge: Polity.

Coole, Diana. 2005. Dialectical Critical Realism and Existential Phenomenology: A Dialogue. New Formations 56(1): 121–132.

Creswell, John W.; Plano Clark, Vicki L.; Gutmann, Michelle L.; and Hanson, William E. 2003. Advanced Mixed Methods Research Designs. In Handbook on Mixed Methods in the Behavioral and Social Sciences, edited by Abbas Tashakkori and Charles Teddlie, pp. 209–240. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Dawson, Walter. 2010. Private Tutoring and Mass Schooling in East Asia: Reflections of Inequality in Japan, South Korea, and Cambodia. Asia Pacific Education Review 11(1): 14–24.

―. 2009. The Tricks of the Teacher: Shadow Education and Corruption in Cambodia. In Buying Your Way into Heaven: Education and Corruption in International Perspective, edited by Stephen P. Heyneman, pp. 51–74. Rotterdam: Sense.

Dean, Kathryn; Joseph, Jonathan; and Norrie, Alan. 2005. New Essays in Critical Realism. New Formations 56(1): 7–26.

Descartes, René. 1637/1960. Discourse on Method and Meditations. Translated by Laurence J. Lafleur. New York: Liberal Arts Press.

George, C. 1992. Time to Come out of the Shadows. Straits Times [Singapore]. April 4.

Graeber, David. 2001. Toward an Anthropological Theory of Value: The False Coin of Our Own Dreams. New York: Palgrave.

Ivankova, Nataliya V.; Creswell, John W.; and Stick, Sheldon L. 2006. Using Mixed-Methods Sequential Explanatory Design: From Theory to Practice. Field Methods 18(3): 3–20.

Marimuthu, T.; Singh, J. S.; Ahmad, K.; Li, H. K.; Mukherjee, H.; Oman, S.; Chelliah, T.; Sharma, J. R.; Salleh, N. M.; Yong, L.; Leong, L. T.; Sukarman, S.; Thong, L. K.; and Jamaluddin, W. 1991. Extra Instruction, Social Equity and Educational Quality. Report prepared for the International Development Research Centre, Singapore.

NGO Education Partnership (NEP). 2007. The Impact of Informal School Fees on Family Expenditure. Phnom Penh: NGO Education Partnership.

Patomaki, Heikki; and Wight, Colin. 2000. After Postpositivism? The Promises of Critical Realism. International Studies Quarterly 44(2): 213–237.

Roesgaard, Marie H. 2006. Japanese Education and the Cram School Business: Functions, Challenges and Perspectives of the Juku. Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies Press.

Stevenson, David Lee; and Baker, David P. 1992. Shadow Education and Allocation in Formal Schooling: Transition to University in Japan. American Journal of Sociology 97(6): 1639–1657.

Straits Times-Nexus Link Tuition Survey. 2015. http://www.straitstimes.com/sites/default/files/attachments/2015/07/04/st_20150704_amtuition04_1480169.pdf, accessed September 17, 2017.

Tan, T. 2014. $1 Billion Spent on Tuition in One Year. Straits Times. November 9, p. 90. http://www.asiaone.com/singapore/1-billion-spent-tuition-one-year, accessed September 17, 2017.

Ventura, Alexandre; and Jang, Sunhwa. 2010. Private Tutoring through the Internet: Globalization and Offshoring. Asia Pacific Education Review 11(1): 59–68.

Watanabe, Manabu. 2013. Juku: The Stealth Force of Education and the Deterioration of Schools in Japan. Charleston: CreateSpace.

1) I recognize that the term “shadow education” is itself problematic and debated. Nevertheless, I will use it throughout this chapter to describe the body of research that looks at the phenomenon named as such. Although I put the term in quotes at the outset, I will refrain from making similar notations in later uses.

2) The term “private” is also debated between conceptualizations that see it as either a primarily fee-based service or any educational service outside public schooling. I will not address these debates here.

3) The Latin-script rendering of the Khmer script is based on the International Phonetic Alphabet. English translations are my own.

4) Indeed, in my fieldwork (Brehm 2015), which occurred after developing the labels for the different types of tutoring presented here, I came across the term sahlah kuə. This term means, roughly, the “institution of extra class.” This phrase implies a level of institutionalization that the term ɾiən kuə does not.

5) The Cambodian currency is the riel. At that time, US$1 was worth approximately 2,600 riels.

6) It is also possible that the vocabulary employed in the Review (Cambodia 1994) derived from vocabularies in the authors’ home countries.

7) The progression of the static description but changing terminology begins with the 1994 Review (Cambodia 1994). It then moves to Bray’s 1996 comparative study of parental and community financing for education in nine East Asian countries, which included Cambodia. In this report, one of Bray’s (1996a) conclusions was that Cambodian households pay a disproportionate amount of money toward education compared to the government in relation to the other countries. This finding prompted Bray (1999) to explore the Cambodian case of private and community financing of education in more detail.

8) Bray (1996a, 32) did, however, use the terms “private supplementary tutoring” and “supplementary out-of-school tutoring” to describe tutoring in countries other than Cambodia.

9) This contrasts with the typical way Bray (1999) categorized tutoring as an out-of-school expense for families in other countries.

10) The evolution of these ideas in Bray’s work can be traced to various locations, including his reports on Cambodia (1995a), Lao PDR (1995b), and Bhutan (1995c), and an earlier paper on the challenges to fee-free education in poor countries (Bray 1987). These ideas were also undoubtedly influenced by the nascent literature on shadow education in other contexts being published at the time (e.g., Marimuthu et al. 1991; George 1992; and Stevenson and Baker 1992).

11) Bray’s (1996b, 4) study included a matrix that separated the nature of curriculum into either mainstream or alternative, and the nature of schools into elite, standard, second-chance, or supplementary. In the discussion of supplementary private schools Bray included “tuition” or “private tutoring.” Bray wrote that some supplementary private schools “shadow the public system and provide tuition in the same subjects as mainstream schools” (ibid., 20). Moreover, “the scale of private tutoring causes official embarrassment in so far as it reflects shortcomings in the public system and can be a heavy burden on household incomes” (ibid.). In this report therefore, the terms “supplementary” and “shadow” already appeared alongside “private tutoring.”

12) A critical realist approach has its limitations, too—namely, as one of the reviewers correctly pointed out, the level of the real assumes a transcendent pattern that underpins reality, an assumption challenged by philosophers such as Heidegger and Nishitani. This, moreover, says nothing of philosophical systems developed entirely outside of the West (Connell 2007).