Contents>> Vol. 7, No. 1

Independent Woman in Postcolonial Indonesia: Rereading the Works of Rukiah

Yerry Wirawan*

*Department of History, Sanata Dharma University, Mrican, Gejayan, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

e-mail: yerry.wirawan[at]gmail.com

DOI: 10.20495/seas.7.1_85

This paper discusses the strategic essentialism of gender and politics in modern Indonesia by rereading literary works of Siti Rukiah (1927–96): her first novel, Kedjatuhan dan Hati (1950), and her collection of poems and short stories Tandus (1952). It locates Rukiah’s position in modern Indonesian politics and the literary world to understand how she crafted her literary skills. It highlights the importance of her hometown, Purwakarta, as the locus of her literary development. It argues that as a representative female writer of the time Rukiah offered important contributions to the nation’s consciousness of gender equality and liberation from the oppressive social structure.

Keywords: Rukiah, Purwakarta, female author, postcolonial literature, Indonesia

Introduction

During the early years of Indonesian independence, the young generation (Pemoeda) played an important role in the nation’s literary world. Writing was a medium to express the restlessness and rebellion of the young generation (see Teeuw 1967; Soemargono 1979). Writers of the period were collectively known as the “1945 Generation,” and Chairil Anwar (1922–49) was the towering figure of this generation—his poems were praised for the prose he formulated to express a sense of courage and boldness. Siti Rukiah (1927–96) was a little younger than Anwar, yet she produced exceptional works. She, too, wrote a number of poems during this period, and in 1948 she was a correspondent for Poedjangga Baroe (New writer), a Batavia/Jakarta-based avant-garde literary magazine. She was one of the authors of this generation who productively published literary works in postcolonial Indonesia.1)

After the transfer of sovereignty in 1949, Rukiah continued her writing activity and involvement in politics throughout the 1950s and 1960s. She joined the leftist artist group Lembaga Kebudayaan Rakyat (LEKRA, League of People’s Culture) in the 1950s. Unfortunately, her bright talent and career were halted abruptly in 1965 amid the brutal purge of the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI, Partai Komunis Indonesia). She was detained and sent to prison without due process, and after her release in the late 1960s she lived the rest of her life in difficulty with six children. Although her name is mentioned in contemporary Indonesian literary textbooks, only a few young Indonesians are able to access her works.2)

Rukiah’s writings and life have attracted a number of scholars of Indonesian literature.3) Annabel Teh Gallop (1985) examines her literary works by focusing on their emotional and intellectual ideas. From her analysis, she concludes that Rukiah’s Kedjatuhan dan Hati (The fall and the heart) is, in fact, a representation of the author’s love affair and psychological conflict. Julia Shackford-Bradley (2000) offers a different reading on Rukiah. Based on textual and language analyses as well as interviews with Sidik Kertapati, she sees Rukiah as constructing herself on the ambivalent choices that she faced at the time of her writing. She concludes that the revolutionary figures in Rukiah’s works were Rukiah’s own inventions—in other words, fictional (Shackford-Bradley 2000, 254). Alicia Marie Lawrence (2012) compares Rukiah to Eden Robinson (an indigenous female writer from Canada) and finds that Rukiah’s writings were a product of the communication of her emotional experience, based on her submissiveness as an indigenous woman. She concludes that Kedjatuhan dan Hati represents the voice of a subaltern woman and that in current light, reading it may have some practical value for community organization and political decision making.

Although these studies have different methods, they focus on Rukiah’s literary works as her personal achievement and reflection of inner conflict rather than a direct expression of the revolution that she experienced. They also analyze Rukiah in comparison to other (female) literary figures: Shackford-Bradley compares Rukiah to Kartini, Hamidah, and Soewarsih Djojopoespito; Lawrence compares her to Robinson. This comparative reading is useful to understand Rukiah’s creative inspiration and distinctive qualities as compared to other female authors. Understandably, Shackford-Bradley’s and Lawrence’s readings emphasize the literary values of Rukiah’s works rather than the historical trajectory of the socio-political conditions that allowed Rukiah to write. As such, they fail to consider Purwakarta (in West Java), her hometown, as an important locus that forms Rukiah’s consciousness and in turn informs her writings.

This article intends to place Rukiah’s literary works as the historical documents of a young Indonesian woman during the revolution. It emphasizes Purwakarta and its surroundings as providing the context of Rukiah’s early writings: the novel Kedjatuhan dan Hati (1950) and her anthology of short stories Tandus (Desert) (1952). This article starts with a brief summary of Indonesian women writers and their movement during the colonial period. Following that, it discusses Purwakarta—where Rukiah once resided and produced a number of literary works—in the context of the Indonesian Revolution (1945–49). This is followed by a short biography of Rukiah and the historical context of her stories. In the last part, this article analyzes and (re-)interprets her texts on socio-political issues, especially on modernity. This article argues that although Rukiah’s literary works can be read as her individual achievement, they are also a result of the socio-political transformation that affected her hometown and her life.

Female Authors during the Colonial Era

During the colonial period native women had to suffer multiple forms of repression due to the colonial system and patriarchal tradition, while male figures dominated the media and political organizations. Nonetheless, they used writing as an important medium to channel their concerns and views on social issues that affected their lives. There were at least two prominent Indonesian women whose literary works were published and widely read during colonial times: Raden Adjeng Kartini and Soewarsih Djojopoespito. Interestingly, they came from different family backgrounds, and thus they can be considered to represent the diversity of Indonesian female intellectual figures in the pre-independence period.

Kartini was born to a noble family on April 21, 1879 in Rembang, Central Java. Due to her aristocratic background, she was able to attend Dutch elementary school, at least until the age of 12 years. During her adolescence, following Javanese tradition for noble young girls, she had to discontinue her studies and avoid social activities in order to prepare for marriage (pingit). During this time of seclusion, Kartini spent most of her time reading books and corresponding with a number of Dutch pen friends. Her letters demonstrate her critical thinking on various issues (they were written in eloquent Dutch). Her primary concern was girls’ right to education and the local traditional practice of polygamy. At the age of 24 Kartini became the fourth wife of a nobleman, but unfortunately on September 17, 1904 she died at the age of 25 after giving birth to a son.

Although Harsja Bachtiar regards Kartini’s seclusion as a consequence of her nobility, her life represents the dilemma of standing as a modern woman versus living in line with tradition.4) In the beginning of the twentieth century in the Dutch Indies, education access for girls, underage marriage, and polygamy were certainly the main issues facing native women as reported in colonial surveys.5) Given such a situation, Kartini’s life (except her tragic death) represents the ideals of a native woman who was not only fluent in a European language and could express her thoughts and concerns but also an enlightened native. In order to push for social change in the colony, an edited collection of Kartini’s letters was published in 1911 (the Malay version was published in 1922) and became a best seller in colonial society. Royalties from her book were donated to establish Kartini’s school in 1912. These efforts to increase education for girls were eventually supported by the colonial government, which adopted the ethical policy of girls’ education and attempted to modernize the colony.

In the following period, the increasing number of educated women gave rise to the presence of women activists in the first decade of the twentieth century. The first native women’s organization was Putri Mardika (Free Daughter), founded in Batavia in 1912. This organization aimed to help women who wished to continue their education, to increase their self-confidence, and contribute to society. In 1913 Putri Mardika published its own newspaper, which discussed various issues including polygamy and child/underage marriage (see Vreede-de Stuers 1959).

In the 1920s, the women’s movement gained popularity among native activists. There were an increasing number of social organizations with a women’s section. Two months after the Second Indonesian Youth Congress, 30 women’s organizations arranged the First Indonesian Women’s Congress in Yogyakarta on December 22–26, 1928. This congress concluded with an agreement to form a women’s federation, Perikatan Perempuan Indonesia (PPI, Indonesian Women’s Union). However, the First Indonesian Women’s Congress did not mention clearly its political stance on the nationalist issue in its communiqué. Sukarno, the most prominent nationalist leader at the time, regretted the result of this congress (see Wieringa 2010).

A different picture of the relationship between female activists and male domination in the nationalist movement is described in an autobiographical novel published in 1940, Buiten het Gareel (Out of harness). This novel was written in Dutch by Soewarsih Djojopoespito, who was born on April 20, 1912 in Bogor. She was educated at Kartini’s school before moving to Middlebaar Uitgebreid Lager Onderwijs, or Dutch lower secondary school, in Bogor. In 1931 she became a teacher at Taman Siswa in Batavia, where she met her future husband, Soegondo Djojopoespito, a key person in the youth congress in 1928 (see Shackford-Bradley 2000, 199).

Her story took place in the 1930s, when there was a great deal of anticolonial sentiment among native intellectuals. Buiten het Gereel recounts the story of Sulastri, a teacher at a private school (or sekolah partikelir),6) and her husband, Sudarmo, a political activist. The novel describes the couple as “proletarian intellectuals,” meaning that Sulastri and her husband were educated figures although they were not part of the elite class. This depiction was in line with a phenomenon at the time of an increasing number of young people among the native population who chose to have an independent career in the private/nongovernmental sector rather than seeking a position in a government office. Nevertheless, working as a political activist required Sudarmo to repeatedly relocate to different cities. Sulastri dutifully followed her husband, as was expected of an ideal wife. Despite their unsettled life, Sulastri was able to manage their meager income.

The novel provides a contrast to the common image of Kartini as the ideal woman. Sulastri is described as being more articulate: she could express her opinions freely and decide her own life and path, both as a female activist and as a devoted wife. Although the novel describes Sulastri as a woman of her own thoughts, it actually uncovers an unequal relationship between male and female intellectual-activists. Sulastri’s life is still tied to Sudarmo’s as she (still) consents to live under her husband’s authority.

During the Japanese period, women’s organizations were dissolved. In turn, the Japanese military administration established Fujinkai, which was led by the wife of a top local officer. It was obligatory for all civil servants’ wives to register as its members.7) It also recruited a number of ordinary women to train in order to support the Japanese army at war by engaging in such activities as visiting wounded soldiers, knitting socks, and entertaining Japanese and Pembela Tanah Air (PETA, Defenders of the Fatherland) soldiers (Wieringa 2010, 144). Later, these practical skills came in useful in supporting the Indonesian Revolution.

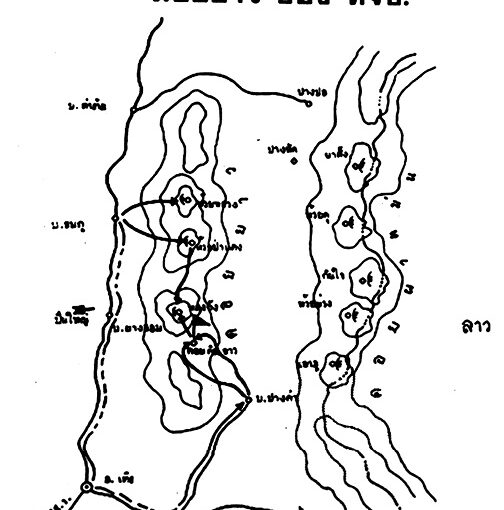

Purwakarta Area during the Revolution8)

Purwakarta is located in the Karawang area, which is approximately 80 kilometers from eastern Jakarta. When the republic moved its capital to Yogyakarta in the beginning of 1946, this area soon became the frontline of the battlefield. The local population of Purwakarta undoubtedly supported the republican cause and embraced the revolutionary idea due to the misery they had to suffer during the colonial period. Under Japanese occupation, Karawang and its surroundings were forced to supply rice crops and manpower labor (romusha). Those who failed to fulfill the military’s authority of this obligation were detained and persecuted. Consequently, there was great resentment among the common people, who joined gangsters to wreak revenge against the Japanese and Allied forces during the revolution.

After the defeat of Japan, people in the Karawang area immediately manifested their discontent and resentment against local Japanese. The PETA units in Rengasdengklok (60 km north of Karawang) seized power early in the morning of August 16, 1945. They disarmed a few Japanese and raised the Indonesian flag. The PETA’s revolt in Rengasdengklok spread rapidly to Purwakarta. The alliance between the conservative nationalists, the PETA, the police, and the civil service was formed while the PETA disarmed the security and took over the town from the Japanese. Although the Japanese immediately succeeded in crushing this insurrection, the revolutionary spirit had started in the Karawang region (Cribb 1991, 49–50).

Meanwhile, political tensions were rapidly rising in Jakarta. The young generation organized under Angkatan Pemuda Indonesia (Youth Generation of Indonesia) formed a joint command organization, the Lasykar Rakyat Jakarta Raya (LRJR, People’s Militia of Greater Jakarta), in Salemba (in central Jakarta) on November 22, 1945; they were headed by a former medical student (ibid., 71). Their main task was to defend the town, although they had limited military arms. And this dire situation made them powerless with the coming of the Allied forces to Jakarta. On December 27, 1945 the Allied forces were instructed to restore order with repressive measures, including searching resistance groups in the kampungs of Jakarta. Apparently, this repression was too heavy to fight against. In less than a week, it was reported that Allied forces detained 743 people and successfully controlled the town. Facing this critical situation, the LRJR had to leave Jakarta and moved their headquarters to Karawang (ibid., 72–73).

The LRJR reorganized their army group in Kawarang in a relatively simple way.9) Inspired by the heroic struggle in Surabaya, they planned to push away the Dutch and British by launching a massive attack on Jakarta. Thus, they needed to strengthen their forces by connecting the struggle with other armed groups in the region (ibid., 75). With the help of these groups, the LRJR succeeded in controlling a strategic position in the front line. Purwakarta was an important city for their struggle, and it was from this city that they broadcast political programs to gather mass support using transmitters of the Radio Republik Indonesia (Radio of Republic of Indonesia).

It should be remembered that the Indonesian Revolution involved various groups with competing ideological perspectives (see Anderson 2001). The armed groups were generally divided based on religion, nationalism, and socialism. The LRJR itself had numerous affiliated units, and the LRJR in Karawang was closely associated with Pesindo (Indonesian Socialist Youth) although never a part of it (Cribb 1991, 75). Interestingly, the LRJR extended their struggle into educational activities so that they could improve political consciousness among their members and common people in the region. This strategy certainly reflected their mass-based politics. There was a high level of illiteracy among the people in the region, and the educational work was a struggle of its own. On the other hand, the LRJR realized that providing a political education was important to build up a system of village defense (pertahanan desa), which in turn would help the organization.

Rukiah in Purwakarta10)

Rukiah was born on April 27, 1927 in Purwakarta. She went into education training during the Japanese occupation and worked as a teacher at a girls’ school in her hometown. According to Sidik Kertapati, her interest in writing led her into contact with leftist artists in Purwakarta and Bandung (Shackford-Bradley 2000, 254). In the coming years, her network of artist friends was instrumental in her accessing the literary world.11) Rukiah’s first poem was published in Godam Djelata,12) a magazine edited by Sidik Kertapati (1920–2007), a prominent revolutionary, member of the LRJR, and Rukiah’s future husband.

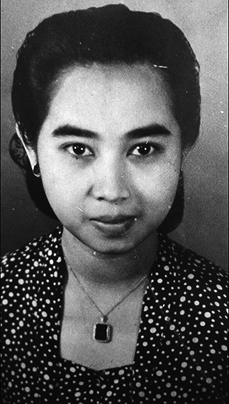

Fig. 1 Rukiah, c. 1952–53 (Photo: Family collection)

After finishing her training, Rukiah rapidly developed her literary career. When she was 21 years old (May 1948), she worked for Pudjangga Baru as its Purwakarta correspondent. In the same year, she worked for Mimbar Indonesia and Indonesia. It was during this time that Rukiah developed genuine concerns about the cultural life of her hometown. In 1949 she founded the cultural magazine Irama (based in Purwakarta) and became its editor. Despite her literary activities, Rukiah maintained her job as a schoolteacher. Purwakarta was not simply a hometown in a nostalgic sense but became the breeding ground for her to launch a writing career on her own. According to Sidik Kertapati, Rukiah stayed home during 1948–49 (ibid., 257) and produced a number of poems, short stories, and a novel and prepared them for publication in the following years.

In another testimony, Pramoedya Ananta Toer shared a memory that gives another nuance to Rukiah’s literary activities:

In 1949 Rukiah created [the journal] “Indonesia Irama” and held her position as editor while engaging in activities to help the guerilla forces. . . . She avoided being arrested for these activities on numerous occasions, through her associations with the local Wedana, but she witnessed the killing of one of the guerilla fighters who she had been harboring in her house. In 1949 she was given the task to visit prisoners of war being held in Bukit Duri. (ibid., 257–258)

Pramoedya’s testimony confirms Rukiah’s involvement in the revolutionary struggle that took place in her hometown. Her “engaging in activities” may have been due to her educational background and nationalist ideals, which inspired her to take risks by harboring independence fighters. In turn, Rukiah was inspired by her experiences among the independence fighters. As we shall discuss below, she expressed her thoughts and restlessness about this subject in her stories.

Rukiah’s Entry into the Literary World

Rukiah moved to Jakarta in 1950 and began working as an editorial secretary at Pudjangga Baru. In the same year, her novel Kedjatuhan dan Hati was published. It seems that it received a lukewarm response within literary circles in Jakarta. But that changed with the publication of her collection of poems and short stories, Tandus, in 1952. In 1953 she won a literary prize from the Badan Musjawarah Kebudajaan Nasional (National Cultural Board) for Tandus.13)

It should be noted that the early years of postcolonial Indonesia were marked by the attempt of several Indonesian artists to define the future of Indonesian culture. On February 18, 1950, a group of Indonesian artists declared the Surat Kepercayaan Gelanggang (Gelanggang Testimonial). This manifesto emphasized that Indonesian culture was part of the world’s culture rather than an isolated phenomenon. A few months after the declaration, a group of leftist artists founded the Lembaga Kebudajaan Rakjat (LEKRA, Institution of People’s Culture) on August 17, 1950. In contrast with the Surat Kepercayaan Gelanggang, in its manifesto LEKRA underlined that the people were the sole creator of culture and the new Indonesia must be based on the struggle against feudal and imperialist cultures. In short, LEKRA criticized Surat Kepercayaan Gelanggang supporters as adopting the culture of the capitalist class (Dharta 2010).

It is difficult to conclude when exactly Rukiah joined LEKRA. In the first congress of LEKRA on January 28, 1959, she put forward the ideal that progressive artists should visit peasants’ villages and labor camps.14) She was elected as a member of the National Council of LEKRA, along with some of her artist friends such as the painter Affandi (1907–90), Hendra Gunawan (1918–83), and the writer Rivai Apin (1927–95).15) Yet, her choice to join LEKRA was not surprising. In her works she already expressed, to a certain degree, her support for leftist ideas.

Women and the Revolution in Tandus

Although Tandus as a collection was published two years after Kedjatuhan dan Hati, some of the poems and short stories were written much earlier. The collection consists of 34 poems and six short stories, and Rukiah wrote them before she worked on the novel. In fact, some poems were already published elsewhere before 1950: for example, Buntu Kejaran was already published in Pujangga Baru in 1948.

As Gallop (1985) has discussed Rukiah’s poems extensively from a literary point of view,16) the focus here is on Rukiah’s short stories in Tandus.17) The background of these stories is mainly the revolution, and the main character is the common people. Although most of the narrators are female, male protagonists play a key role. This structure reminds us of Du Perron’s critical commentary on Soewarsih’s work that Sudarmo (the husband) is the hero, not Sulastri (the wife) (Du Perron 1975, xii). Indonesian women’s writings show that women had an inferior position to male activists and guerrillas in the Indonesian political context of the period.

Like her poems, Rukiah’s prose employs a simplicity of style (“kesederhanaan baru”), a new genre in Indonesian literature at the time that was invented by Idrus (1921–79), a well-known Indonesian writer (Gallop 1985, 44). In this context, Purwakarta and its people became an essential part of Rukiah’s works to represent the simple life in the region. In contrast, newness and revolutionary ideas always came from the foreigner. Rukiah has successfully highlighted the presence of common people in the region when they confronted or embraced revolutionary ideas.

The simplicity in style is clearly presented in Rukiah’s first short story, “Mak Esah” (Esah’s mother).18) It tells of an elderly woman who lives alone in a house 4 kilometers from a kampung named Tandjungrasa. This is the only story in which Rukiah details the location of the protagonist’s village, as if she wants to highlight that it is based on a true story.

The story describes the woman as an honest person who lives in her own world with her simple thoughts, as she believes that she has done good deeds in her life and thus expects God will help her. Ironically, her kindness and simplicity do not protect her from being affected by political events. The story informs readers that people actually have forgotten her name and instead call her by the name of her oldest son, who died during the Communist insurrection in 1926. Since then, misery keeps coming into her life. Her husband dies at the beginning of the Pacific War, and her daughter, Rumsah, passes away from malaria during the Japanese occupation (1942–45). During the revolutionary period, the elderly woman does not believe in political change as she does not see the difference in the meaning of merdeka (freedom). For her, merdeka simply means another king: an Indonesian king with a pitji (traditional cap). Nonetheless, when a group of guerrillas seek shelter in her house, she willingly lodges them simply because they look nice and polite. The next morning when a group of Dutch soldiers raid her house to look for the guerrillas, they burn down her house and shoot her dead while she is still unable to understand what happened and her role in it. Her “simple” life illustrates the political gap between the guerrillas and common people whose lives are still miserable and who have to bear all the costs despite the political changes after merdeka.

In “Isteri Peradjurit” (The soldier’s wife), Rukiah tells of a couple who live in a village in West Java, somewhere near Garut. The story revolves around its protagonist, a beautiful young woman named Siti, who is the couple’s only child. The couple are known simply as Pak Siti (father of Siti) and Mak Siti (mother of Siti). Pak Siti works on the family’s vegetable farm and is supportive of his daughter’s education despite Mak Siti insisting that a woman’s place is in the house. At the age of eight, Siti goes to the school for girls in town. After Siti finishes her studies, Pak Siti gives her sewing equipment so she can work as a tailor. This background gives the reader a sense of the simplicity in the lives of the characters as something they can relate to their own situation.

As the story unfolds, however, the family’s simple life is complicated by the arrival of the Japanese occupation army. Pak Siti refuses the order of the Japanese, who have mobilized the people to plant castor beans (Ricinus communis) to serve the needs of war. His main concern is his farm and the survival of his family, as the family has no interest in political matters. His refusal to follow orders costs him his life: one morning he is picked up in a truck (mobil tidak bertutup) and never returns home. The story continues by introducing Hasjim, a young man from Garut, who is rumored to be a fugitive from the Kempeitai (Japanese secret police). He falls in love with Siti, and three months later they get married. Hasjim introduces Siti to politics, books, and his friends. When the revolution breaks out, Hasjim wants to join the army but Siti worries about it as she is pregnant. Eventually, she lets him join the revolution when their child is born.

Although the story illustrates the troubles of a simple family who live in a small town, it shows how politics affects the lives of its characters based on their gender. Readers see how the male characters can do whatever they please based on their political outlook (they are either politically naive like Pak Siti or politically engaged like Hasjim). As a result of the males’ political outlook, it is the female characters (Siti and Mak Siti) who have to cope with the burden of life on their own shoulders. While the male characters are free to act on their political outlook, the female characters are compelled to follow what their husbands want to do. It seems the message that Rukiah wants to convey is how revolution (even in a small town) was experienced differently by males and females, and it was the females alone who had to strike a balance in their life. Even when females wanted to express their political outlook, the conditions of the revolution did not allow them to do so. Thus, the story works as a criticism of unequal gender-based political expression of revolutionary ideals.

This notion of women’s political outlook is described also in “Antara Dua Gambaran” (Between two perspectives), the story of Ati, a young female teacher and writer who lives in a small town during the Japanese occupation. Ati has a lover, Irwan, a law student who is a political activist. Irwan introduces Ati to one of his classmates, Tutang. The story describes Tutang and Irwan as two young men of completely different characters. While Irwan is a passionate political activist, Tutang is a quiet, obedient, and tidy person from a middle-class family. Despite her mother’s preference for Tutang, Ati chooses Irwan as her lover as she sees Tutang as an orang kosong (empty person). Yet, Irwan reminds her to be more friendly and patient with Tutang and even suggests that she learn writing from him. Ati follows Irwan’s suggestion, and from there her perception of Tutang gradually changes.

The proclamation of independence in 1945 transforms the lives of these three characters. Irwan has been getting more involved in politics and has become the leader of a people’s militia in West Java (Lasjkar Rakjat se-Djawa Barat). Meanwhile, Tutang works as an editor of a magazine in Jakarta. Ati continues her work for a while as a teacher and spends more and more time reading and writing. The political situation with the revolution forces Irwan to continue his armed struggle in the mountains. Later, Ati hears of Irwan’s death and chooses to marry Tutang. The story portrays the limitations of women’s political outlook during the revolution. They had the freedom to read and write, but their political expressions were confined within males’ prerogatives. This story also shows that advice from a male protagonist (Irwan’s suggestion to Ati to approach Tutang despite her objections) is always correct.

In “Surat Pandjang dari Gunung” (Long letters from the mountains), Rukiah narrates the love story of Hambali, a guerrilla fighter, and Isti, a schoolteacher of Taman Siswa in a small town. The title of this short story refers to the love letters Hambali sends to Isti, in which he discusses political issues and difficulties during the war, as well as the educational activities carried out by guerrillas in the mountains. As communications between guerrilla fighters and the general population are difficult and closely monitored by the Dutch, Isti receives these letters discreetly from a courier boy, Haja, one of her students. Haja is an orphan: his mother has passed away, and his father was killed by the Dutch army. Having no family, Haja later chooses to follow Hambali to war and thus has to leave school. Isti fails to persuade Haja to remain in school. Isti represents the life of many women during the revolution who were unable to intervene in decisions made by males to go to war. She is allowed to know about the revolution only from the letters sent to her, and nothing else. Ironically, these letters could be confiscated by the Dutch and used to implicate her as a sympathizer. In the end, Isti chooses to burn all the letters.

“Tjeritanja Sesudah Kembali” (His story on returning) is the story of a 26-year-old man, Nursewan, narrated by his close friend, a young woman. The young woman is known only by her nickname, Rus. Rus informs the reader that Nursewan is a simple man who has uncertain feelings about his future. Having failed to date women of his choice, Nursewan decides to join a guerrilla army. Rus cannot believe that Nursewan is capable of doing such a thing. When Rus leaves her hometown for work in Yogyakarta, she loses contact with Nursewan. However, one of her friends later informs her that Nursewan did, in fact, join the guerrilla fighters. Toward the end of the story Rus finally meets Nursewan in a hospital in their hometown, where he explains in detail his reasons for joining the guerrilla fighters. The story illustrates how men had the option of joining the guerrilla fighters (and could make a claim to being heroic) even though their reasons may have had nothing to do with the revolution. As the story is narrated in the first person by a woman, it highlights how women saw the revolution, which was used by men as an excuse to escape from women’s rejection of their love and at the same time to claim their masculinity.

The Fallout of Revolution in Kedjatuhan dan Hati

As does Tandus, Kedjatuhan dan Hati reflects factual problems experienced by common people during the revolution. The story is about Susi, a young woman who lives in a small town (presumably Purwakarta) with her two sisters and parents. Susi’s mother is the most dominant person in the family, and she is obsessed with materialistic achievements. Meanwhile, Susi’s father is a quiet man. The eldest sister, Dini, is described as an independent young woman who has less self-confidence and feels a little unhappy in the family for being pressured by their parents to marry. The second sister, Lina, is described as the most beautiful and their mother’s favorite daughter. Susi is described as a sincere young woman.

The story informs the reader that Dini and Susi are expected by their mother to marry wealthy men. Under such pressure, they decide to leave their family home. Dini continues her studies abroad, while Susi joins the Red Cross.

It is at work that Susi meets Lukman, a Communist guerrilla, and falls in love with him. However, Susi and Lukman have different views of marriage. Susi would like to have a traditional wedding ceremony. Lukman, on the other hand, does not like ceremonies and is unable to guarantee a “normal” life as he is devoted to politics and revolution. After having a long debate, Lukman accepts Susi’s request:

Karena engkau jang minta, apa sadja perintah itu, aku patuh menurut, sekalipun perintah itu mengambil sepotong kejakinanku. (Siti Rukiah 1950, 54)

Because you asked for it, I will follow and obey whatever your request is although it may eat away some parts of my belief.

They end the night with some time in private. The following day, Susi demands an immediate marriage but Lukman responds that he has to leave for war. Susi is very disappointed and decides to return home.

Upon coming back home, Susi finds Lina, her youngest sister, has matured greatly. Their mother, however, is becoming more insecure. To reconcile with these changes, Susi finally agrees to marry Par, a wealthy man who helped her family through difficult times. It is then that Susi finds out she is pregnant (by Lukman). When finally Lukman comes to see her again and asks her to live with him, she refuses.

The story illustrates male superiority by showing Lukman leaving Susi behind even though initially he had agreed to stay with her. This story also shows the dilemma of a young Indonesian woman during the revolution. Susi has to choose between living with the new revolutionary values or old traditions, between romantic love or arranged marriage, while maintaining her own independent life. Facing this dilemma, Susi chooses to make a practical decision. As such, the story informs us that revolution failed to change the oppressive traditional social structure and create a more egalitarian postcolonial society, and women were caught in the middle. Women’s aspiration to be independent and have a family of their own choice was not fully realized. In postcolonial Indonesia, women still have to depend on their partner, financially and emotionally, and to disregard their own ideals. Thus, the story shows the limited impact of political changes on women’s status.

Conclusion

Like Kartini and Soewarsih Djojopoespito, who came before her, Rukiah expressed her concerns about the status of women. Kartini represents the enlightened female author of the early twentieth century under the colonial ethical policy. In her novel, Soewarsih Djojopoespito represents the rebellious female activist at the dawn of nationalism among the natives. This article shows how, in her own context, through literary works Rukiah was able to express herself as an independent woman to challenge the “normalized” ideals of her revolutionary male friends.

Aside from their literary value, Rukiah’s literary works provide an important documentation of the revolution for the historiography of Indonesia. Kedjatuhan dan Hati and Tandus are based on her experiences and observations during the revolution in Purwakarta that allowed her to write detailed accounts of the common people and beyond their seemingly simple life. Rukiah provides a detailed picture of how revolutionary ideas brought by outsiders drastically changed the lives of simple people in Purwakarta, regardless of how ignorant the latter might have been on political issues. This article also shows how her short stories uncover the complex issues of revolution, such as the political gap among the people, the old traditions that were still maintained in the lives of many young women, and the unequal gender-based political expression of revolutionary ideals. In that sense, Rukiah’s literary works provide a deeper picture of the revolution beyond the revolutionary heroism and political rhetoric of merdeka for all.

Rereading Rukiah’s literary works in the present time brings us to a deeper understanding of the development of the nation’s consciousness for gender equality and liberation from the oppressive social structure. Female authors have come a long way in expressing their thoughts and aspirations about the ideals of an independent woman who is not afraid to express her critical thinking and political outlook. Post-1998 Indonesia has legally ensured women’s rights, but it falls short on providing space for women’s political empowerment. Rukiah’s literary works provide fruitful insights on the status of Indonesian women today.

Accepted: December 11, 2017

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to Rukiah’s family for generously providing me with their mother’s photo and to Ita Nadia and Hersri Setiawan for LEKRA’s materials. I would like also to thank anonymous reviewers for their constructive suggestions. Any errors that remain are my sole responsibility.

Bibliography

Anderson, Benedict R. O’G. 2001. Violence and the State in Suharto’s Indonesia. Ithaca: Southeast Asia Program, Cornell University.

Arti Purbani. 1948. Widyawati. Jakarta: Balai Pustaka.

Bachtiar, Harsja. 1979. Kartini dan peranan wanita dalam masyarakat kita [Kartini and the role of women in our society]. In Satu abad Kartini, 1879–1979: Bunga rampai karangan mengenai Kartini [A century of Kartini, 1879–1979: Anthology of essays on Kartini], edited by Aristides Katoppo, pp. 71–83. Jakarta: Pustaka Sinar Harapan.

Cribb, Robert. 1991. Gangsters and Revolutionaries: The Djakarta People’s Militia and the Indonesian Revolution 1945–1949. Sydney: Asian Studies Association of Australia in association with Allen & Unwin.

Dharta, A. S. 2010. Kepada seniman universal [For the universal artists]. Bandung: Ultimus.

Du Perron, Edgar. 1975. Kata pengantar [Foreword]. In Manusia bebas [Buiten het Gareel or Out of harness], by Soewarsih Djojopoespito, pp. VIII–XV. Jakarta: Djambatan. Translated from Dutch: Du Perron. 1946. Inleiding [Foreword]. In Buiten het Gareel [Out of harness], by Soewarsih Djojopoespito, pp. 5–10. Utrecht, Amsterdam: W. de Haan, Vrij Nederland.

Ensiklopedi sastra Indonesia [Encyclopedia of Indonesian literature]. http://ensiklopedia.kemdikbud.go.id/sastra/artikel/S_Rukiah, accessed April 20, 2016.

Gallop, Annabel Teh. 1985. The Works of S. Rukiah. Unpublished master’s thesis, SOAS, University of London.

Gouda, Frances. 1995. Teaching Indonesian Girls in Java and Bali, 1900–1942: Dutch Progressives, the Infatuation with “Oriental” Refinement, and “Western” Ideas about Proper Womanhood. Women’s History Review 4(1): 25–62.

Jassin, H. B. 1962. Kesusasteraan Indonesia modern dalam kritik dan esei I [Essays and critiques of Indonesian literature]. Jakarta: Gunung Agung.

Lawrence, Alicia Marie. 2012. Shattered Hearts: Indigenous Women and Subaltern Resistance in Indonesian and Indigenous Canadian Literature. Unpublished master’s thesis, University of Victoria.

Njoto. 1959. Revolusi adalah api kembang [Revolution is the fireworks]. In LEKRA, Dokumen I, Kongres Nasional Pertama Lembaga Kebudayaan Rakjat, Solo 22–28 Djanuari 1959 [Document I, First National Congress of LEKRA, Solo, January 22–28, 1959], p. 60. [n.p.]: Bagian Penerbitan Lembaga Kebudajaan Rakjat.

Onderzoek naar de mindere welvaart der inlandsche bevolking op Java en Madoera, verheffing van de Inlandsche vrouw [Reserch on the lower prosperity of the native population in Java and Madoera, improvement of the position of native woman], IXb3. 1914. Batavia: Papyrus.

Rutherford, Danilyn. 1993. Unpacking a National Heroine: Two Kartinis and Their People. Indonesia 55 (April): 23–40.

S. Rukiah Kertapati. 1983. An Affair of the Heart. In Reflections on Rebellion: Stories from the Indonesian Upheavals of 1948 and 1965, edited and translated by William H. Frederick and John H. McGlynn, pp. 49–105. Athens: Ohio University Center for International Studies.

Sapardi Joko Damono. 1997. Sastra pada masa revolusi [Literature in the revolution]. In Denyut nadi Revolusi Indonesia [The heartbeat of the Indonesian Revolution], edited by Panitia Konferensi Internasional, pp. 276–295. Jakarta: Gramedia Pustaka Utama.

Shackford-Bradley, Julia. 2000. Autobiographical Fictions: Indonesian Women’s Writing from the Nationalist Period. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of California.

Siti Rukiah. 2011. The Fall and the Heart. Jakarta: Lontar.

―. 1952. Tandus [Desert]. Jakarta: Balai Pustaka.

―. 1950. Kedjatuhan dan hati [The fall and the heart]. Jakarta: Pustaka Rakjat.

Soemargono, Farida. 1979. Le groupe de Yogya, 1945–1960: Les voies javanaises d’une littérature indonésienne [The “Yogya Group,” 1945–1960: The Javanese ways of Indonesian literature]. Paris: Association Archipel.

Soewarsih Djojopoespito. 1946. Buiten het Gareel [Out of harness]. Utrecht, Amsterdam: W. de Haan, Vrij Nederland.

Stop Naskah2 Lekra di Balai Pustaka [Remove Lekra’s manuscripts from Balai Pustaka]. 1965. Duta Masjarakat. November 6.

Teeuw, A. 1967. Modern Indonesian Literature. Leiden: Leiden University Press.

Tham Seong Chee. 1981. The Social and Intellectual Ideas of Indonesian Writers, 1920–1942. In Essays on Literature and Society in Southeast Asia: Political and Sociological Perspective, edited by Tham Seong Chee, pp. 97–124. Singapore: Singapore University Press.

Vreede-de Stuers, Cora. 1959. L’émancipation de la femme indonésienne [The emancipation of Indonesian women]. Paris: Mouton & Co.

Wieringa, Saskia. 2010. Penghancuran gerakan perempuan: Politik seksual di Indonesia pasca kejatuhan PKI [The destruction of the women’s movement: The politicization of gender relations after the fall of the PKI]. Yogyakarta: Galang Press.

1) See Siti Rukiah, Kedjatuhan dan Hati (1950); and Siti Rukiah, Tandus (1952). The first female author to have published a novel in postcolonial Indonesia was Arti Purbani (Widyawati, 1948). Arti Purbani is the pen name of Raden Ayu Partini Djajadiningrat (1902–98), the wife of Hoesein Djajadiningrat (1886–1960).

2) On November 6, 1965, Duta Masjarakat, the newspaper of Nahdlatul Ulama, reported that although Tandus was republished by Balai Pustaka, its distribution was halted (See “Stop Naskah2 Lekra di Balai Pustaka,” Duta Masjarakat, November 6, 1965). Interestingly, her brief biography (including her involvement in LEKRA) appears in an online encyclopedia published by the Ministry of Education of Indonesia. See Ensiklopedi Sastra Indonesia, http://ensiklopedia.kemdikbud.go.id/sastra/artikel/S_Rukiah, accessed April 20, 2016.

3) Some of her works are translated by John McGlynn. See S. Rukiah Kertapati (1983); Siti Rukiah (2011). In 2017 Ultimus, an independent publishing house in Bandung, republished Rukiah’s works: see Kejatuhan dan Hati (2017) and Tandus (2017).

4) See Bachtiar (1979). For comparison, see Gouda (1995).

5) Nine elite women were interviewed in the 1914 colonial survey on the status of native women: Raden Ajoe Soerio Hadikoesoemo, Raden Ajoe Ario Sosrio Soegianto, Oemi Kalsoem, Raden Adjeng Karlina, Raden Adjeng Amirati, Raden Adjeng Martini, Mrs. Djarisah, Raden Dewi Sartica, and Raden Ajoe Siti Soendari. See Onderzoek Naar de Mindere Welvaart der Inlandsche Bevolking op Java en Madoera, Verheffing van de Inlandsche Vrouw, IXb3 (Batavia: Papyrus, 1914). For a summary, see Vreede-de Stuers (1959, 150–151).

6) These schools were founded across the country by native Indonesian nationalists to fulfill education needs for all Indonesians.

7) This kind of leadership was often taken as a model during the New Order period (1965–98). In fact, one organization, Dharma Wanita, continues this practice even today.

8) This part relies extensively on the study by Robert Cribb (1991), which provides details on the militias and their armed struggle around the Purwakarta area.

9) Cribb (1991, 749) notes, “Although Sutan Akbar was leader, with R.F. Ma’riful as his deputy, the organisation’s policy was directed by a political council (dewan politik) consisting of Khaerul Saleh, Armunanto, Johar Nur, Kusnandar and Akhmad Astrawinata, with later also Mohammad Darwis, Syamsuddin Can and Sidik Kertapati, all of them capable and experienced young politicians.”

10) This part relies mainly on Gallop (1985).

11) Sapardi Joko Damono (1997, 276–279) concludes that most writers in the revolution, in fact, started their writing career before the war. Therefore, Rukiah was an exceptional writer at that time.

12) Brief information on Godam Djelata can be found in Cribb (1991, 74).

13) Badan Musjawarah Kebudajaan Nasional was an important cultural institution founded by the Indonesian government to support national cultural development in the 1950s. Rukiah married Sidik Kertapati in 1952 and gave birth to their son in 1953. It is interesting to note that H.B. Jassin (1962) wrote a bitter critique on Tandus 10 years after it was published. That is partly because in 1962, LEKRA and its opponents were very tense, and this might have influenced Jassin’s view on Rukiah’s earlier work.

14) Njoto (1959).

15) Rukiah wrote a poem titled “Sahabatku” (My friend) as a dedication to one of her painter friends.

16) Gallop (1985) classifies her poems in seven categories: life, truth, desire, revolution, inner struggles, love, and writing.

17) I do not discuss “Sebuah Tjerita Malam Ini” because it was written in 1951, after the revolution was over. The other five short stories were written between 1948 and 1949.

18) Gallop (1985, 43) notes that the story was first published in the Pujangga Baru in 1948 and titled “Gambaran Masyarakat” (A picture of society).